Abstract

Introduction

The benefits of early thromboprophylaxis in symptomatic COVID-19 outpatients remain unclear. We present the 90-day results from the randomised, open-label, parallel-group, investigator-initiated, multinational OVID phase III trial.

Methods

Outpatients aged 50 years or older with acute symptomatic COVID-19 were randomised to receive enoxaparin 40 mg for 14 days once daily vs. standard of care (no thromboprophylaxis). The primary outcome was the composite of untoward hospitalisation and all-cause death within 30 days from randomisation. Secondary outcomes included arterial and venous major cardiovascular events, as well as the primary outcome within 90 days from randomisation. The study was prematurely terminated based on statistical criteria after the predefined interim analysis of 30-day data, which has been previously published. In the present analysis, we present the final, 90-day data from OVID and we additionally investigate the impact of thromboprophylaxis on the resolution of symptoms.

Results

Of the 472 patients included in the intention-to-treat population, 234 were randomised to receive enoxaparin and 238 no thromboprophylaxis. The median age was 57 (Q1-Q3: 53–62) years and 217 (46 %) were women. The 90-day primary outcome occurred in 11 (4.7 %) patients of the enoxaparin arm and in 11 (4.6 %) controls (adjusted relative risk 1.00; 95 % CI: 0.44–2.25): 3 events per group occurred after day 30. The 90-day incidence of cardiovascular events was 0.9 % in the enoxaparin arm vs. 1.7 % in controls (relative risk 0.51; 95 % CI: 0.09–2.75). Individual symptoms improved progressively within 90 days with no difference between groups. At 90 days, 42 (17.9 %) patients in the enoxaparin arm and 40 (16.8 %) controls had persistent respiratory symptoms.

Conclusions

In adult community patients with COVID-19, early thromboprophylaxis with enoxaparin did not improve the course of COVID-19 neither in terms of hospitalisation and death nor considering COVID-19-related symptoms.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV2, Thrombosis, Venous thromboembolism, Anticoagulation, Heparin

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused >6 million deaths to date and led to a global health crisis. Local inflammatory changes in the lungs, together with a hypercoagulable state, immune dysfunction, endothelial injury, and organ failure contribute to the onset of thrombotic complications [1], [2], [3] and the severe clinical course of COVID-19 [4], [5], [6], [7].

The efficacy of anticoagulant prophylaxis in the community setting has been investigated only recently. The ACTIV-4B Outpatient Thrombosis Prevention Trial studied the efficacy of the direct oral anticoagulant apixaban (vs. aspirin and vs. placebo) on early clinical outcomes among outpatients, but could not demonstrate the superiority of antithrombotic treatments [8]. The randomised, open-label, multinational OVID and ETHIC phase III trials failed to show the superiority of enoxaparin (vs. no thromboprophylaxis) on early hospitalisations and deaths. Both trials were terminated prematurely based on the interim analysis results after the enrolment of 475 and 219 subjects, respectively [9], [10]. A fourth randomised controlled trial showed that rivaroxaban had no impact on early disease progression, including symptom resolution, in high-risk outpatients with mild COVID-19 symptoms [11].

After the acute phase of COVID-19, up to 10–35 % of outpatients and 85 % of inpatients may develop a post-COVID-19 syndrome (“long COVID”) [12], [13], characterised by fatigue, headache, and dyspnea, among other symptoms. It is unclear whether early thromboprophylaxis may improve the course of COVID-19-associated symptoms in the post-acute phase. We present the results of the predefined 90-day analysis of the OVID phase III trial investigating whether primary thromboprophylaxis with enoxaparin (vs. no thromboprophylaxis) could reduce hospitalisations and deaths among ambulatory patients, and accelerate the resolution of COVID-19-associated symptoms.

2. Patients and methods

The study procedures and design were described previously [9], [14]. In brief, OVID was a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, investigator-initiated phase III superiority trial conducted in Swiss and German centres between August 2020 and January 2022 (Study Identifier NCT04492254). This manuscript presents the final results of the predefined 90-day analysis after completion of follow-up.

This academic trial was funded by public agencies, institutions, and independent foundations. The study protocol was approved by national, cantonal, and institutional ethical commissions, as previously detailed [9], [14].

2.1. Study patients

Outpatients with a positive test for SARS-CoV2 in the past five days, aged 50 years or older, with acute respiratory symptoms or body temperature >37.5 °C, and eligible for ambulatory treatment were considered for inclusion. Main exclusion criteria consisted of contraindications to anticoagulant treatment, concomitant dual antiplatelet treatment, or prior major bleeding. The full list of eligibility criteria was described previously [9], [14] and is reported in the Supplementary material (Appendix A, Supplementary data).

2.2. Randomisation, masking and procedures

The study intervention was enoxaparin 40 mg/0.4 mL administered once daily in the ambulatory setting as subcutaneous injection for 14 days. The comparator was the standard of care (no thromboprophylaxis). The rationale for study design and procedures were described previously [9], [14]. In brief, eligible participants were randomised in a 1:1 ratio: randomisation was stratified by age group (50–70 vs. >70 years), and study centre and the sequence was computer-generated and integrated into the electronic data capture software RedCAP (Vanderbild University, v9.1.24). This task was accomplished by personnel of the Clinical Trial Unit of the University Hospital Zurich. Prior to randomisation, eligibility criteria, routine vital- and recent laboratory parameters were evaluated by trained physicians in a single, in-hospital visit. Patients randomised in the enoxaparin arm underwent the first injection during the in-hospital inclusion visit; the remaining enoxaparin doses were administered or self-administered at home. The suspected serious adverse events, study outcomes, vital status, and presence of symptoms of participants were routinely assessed following a structured questionnaire during the pre-defined follow-up visits at 3, 7, 14, 30, and 90 days after randomisation. In-hospital visits were organised if patients presented with signs or symptoms indicating the onset of a serious adverse event or for any other medical circumstance requiring immediate attention.

2.3. Study outcomes

The primary outcome was a composite of any untoward hospitalisation and all-cause death occurring within 90 days after randomisation. Secondary outcomes included (i) each component of the primary outcome, (ii) disseminated intravascular coagulation, (iii) hospitalisation for cardiovascular, pulmonary, or COVID-19-related events, and (iv) arterial and venous major cardiovascular events occurring within 90 days after enrolment [8]. The latter encompassed myocardial infarction/myocarditis, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, acute splanchnic vein thrombosis, peripheral arterial ischaemic events, and ischaemic stroke. The safety outcomes were major bleeding and non-major clinically relevant bleeding, as defined by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria. The full list of study outcomes, their definitions, and their rationale have been previously presented and discussed [9], [14].

For this 90-day follow-up study, we analysed the changes in the prevalence of COVID-19-related symptoms in the two study arms over time. Data on symptoms was prospectively collected by trained study personnel at the time of randomisation (baseline visit) and on a routine basis during the follow-up telephone calls 3, 7, 14, 30, and 90 days after randomisation. The questionnaire was composed at the time of study design and included a wide spectrum of signs and symptoms, including but not limited to respiratory ones. No validation of the questionnaire was possible as it was drafted in the early summer of 2020 for the scopes of the study and it did not include a severity scale.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Public data on hospitalisation rate and mortality related to COVID-19 in Switzerland between March and May 2020 served to estimate the rate of the primary outcome among adults aged 50 years or older of 15 % under standard of care conditions (no thromboprophylaxis). Based on previous efficacy data from randomised controlled trials on low-molecular-weight heparin for primary thromboprophylaxis, we expected a reduction to the rate of 9 % for the primary outcome under treatment with enoxaparin, as we postulated venous thromboembolic events being at the basis of most COVID-19-related complications [15], [16], [17]. Details on sample size calculation are available in [9], [14]. We calculated, that 920 patients (allocated in a 1:1 ratio) would be required for 80 % power to demonstrate the superiority of enoxaparin vs standard of care (no thromboprophylaxis), with a 2-sided significance level of 5 %. Based on predefined statistical criteria fulfilled at the time of interim analysis after 50 % of the study population, the study could be prematurely stopped for futility as the probability of observing superiority of thromboprophylaxis with enoxaparin (vs. no thromboprophylaxis) was deemed to be too low under the initial assumptions [9], [14].

The analysis of the primary outcome was based on a log-binomial model, including the treatment group and the stratification variable age group (50–70 vs. >70 years) as independent variables. The estimate was the adjusted relative risk (RR) of the composite primary outcome in the enoxaparin group as compared to the standard of care group. Secondary outcomes were analysed by the log-binomial model, but without adjustment for the age group, resulting in unadjusted relative risk estimates. All estimates were reported with corresponding 95 % Wald confidence intervals (CI). The cumulative incidence of the primary outcome was displayed graphically, taking the event times into account. The estimated prevalence of signs and symptoms over time was visualised, including pointwise 95 % Wilson CIs. The detailed statistical analysis has been described previously [9], [14]. Statistical programming was performed with R (version 4.1.1), in combination with dynamic reporting via Sweave.

3. Results

We pre-screened or screened a total of 3319 subjects and randomised 475 ambulatory patients at nine sites in Switzerland and Germany from August 2020 through January 2022; Fig. S1 (Appendix A, Supplementary data). This period elapsed between the second European wave and the surge of the omicron variant. The final intention to treat (ITT) population consisted of a total of 472 individuals after the exclusion of two patients because of consent withdrawal and one who dropped out. A total of 234 and 238 outpatients were randomised in the enoxaparin and in the standard-of-care group (no thromboprophylaxis), respectively. The safety population amounted to 469 patients. The median time between laboratory confirmation of COVID-19 and randomisation was three (Q1-Q3: 1–5) days.

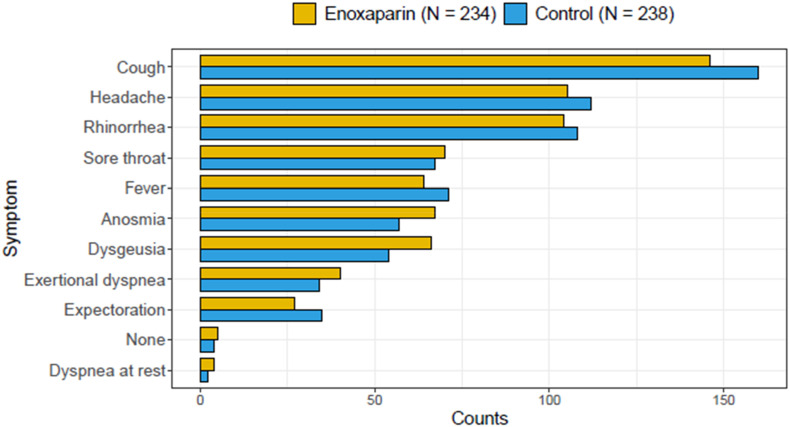

The baseline characteristics and demographic data of patients included in the ITT population are summarised in Table 1 . Median age was 57 (Q1-Q3: 53–62) years, 217 (46 %) patients were women, and 9.5 % of participants received at least one dose of SARS-CoV2 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna). Fig. 1 depicts the baseline distribution of COVID-19-related symptoms in the two groups. Cough and headache were the most common ones with 306 (64.8 %) and 217 (46.0 %) patients being affected, respectively. Rhinorrhea was recorded in 212 (44.9 %) patients. Exertional dyspnea was present in 74 (15.7 %) patients, whereas dyspnea at rest was present in six (1.3 %) patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristic.

| Overall (n = 472) | Enoxaparin group (n = 234) | Standard of care group (n = 238) | Missing values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 57 (53–62) | 56 (53–62) | 57 (53–62) | 0 |

| Women | 217 (46.0) | 114 (48.7) | 103 (43.3) | 0 |

| Body-mass index, kg/m2 | 25.2 (22.9–28.4) | 25.1 (22.8–28.1) | 25.2 (23.0–28.7) | 1 |

| Caucasian | 446 (95.5) | 223 (96.1) | 223 (94.9) | |

| Black | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.3) | |

| Asian | 11 (2.4) | 6 (2.6) | 5 (2.1) | |

| Other | 7 (1.5) | 3 (1.3) | 4 (1.7) | |

| Atherosclerotic diseasea | 22 (4.7) | 8 (3.4) | 14 (5.9) | 0 |

| Arterial hypertension | 115 (24.4) | 53 (22.6) | 62 (26.1) | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 38 (8.1) | 18 (7.7) | 20 (8.4) | 0 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 9 (1.9) | 4 (1.7) | 5 (2.1) | 0 |

| Chronic heart failure | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| History of smoking | 81 (17.2) | 41 (17.5) | 40 (16.8) | 0 |

| Previous malignancy | 22 (4.7) | 8 (3.4) | 14 (5.9) | 0 |

| Hormonal treatment | 19 (4.0) | 13 (5.6) | 6 (2.5) | 0 |

| Platelet count, n ∗ 100/μL | 206 (173–245) | 206 (171–244) | 205 (174–247) | 1 |

| Lymphocyte count, n ∗ 100/μL | 1.7 (1.3–18.5) | 1.7 (1.2–23.0) | 1.8 (1.3–16.0) | 54 |

| Oxygen saturation, % | 97.1 (1.5) | 97.2 (1.4) | 97.0 (1.5) | 0 |

| Heart rate, n/min | 77 (12) | 76 (12) | 77 (13) | 0 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 133 (18) | 133 (19) | 134 (18) | 1 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 84 (13) | 84 (13) | 85 (12) | 1 |

| Temperature | 36.8 (0.6) | 36.8 (0.6) | 36.8 (0.6) | 3 |

| Respiratory rate, n/min | 16 (3) | 16 (3) | 16 (3) | 1 |

| ACE-inhibitors | 24 (5.1) | 10 (4.3) | 14 (5.9) | 0 |

| Corticosteroids | 8 (1.7) | 5 (2.1) | 3 (1.3) | 0 |

| Immunosuppressive drugs | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Antiplatelet agents | 26 (5.5) | 13 (5.6) | 13 (5.5) | 0 |

| Statins | 52 (11.0) | 27 (11.5) | 25 (10.5) | 0 |

Data are n (% of available data), mean (SD), or median (Q1-Q3), unless otherwise specified.

Atherosclerotic diseases include: acute coronary syndrome, angina, prior myocardial infarction, prior stroke, peripheral arterial disease.

Fig. 1.

Counts of patients with COVID-19-related symptoms at baseline.

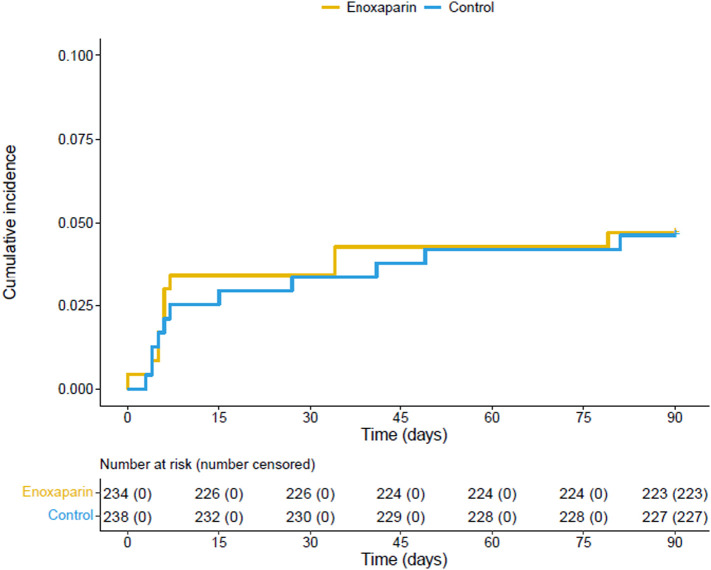

The number of patients with the primary and any of the secondary or safety outcomes is provided in Table 2 . The primary efficacy outcome, a composite of any untoward hospitalisation and death, occurred in 11 (4.7 %) patients of the enoxaparin group and in 11 (4.6 %) of the standard-of-care group (no thromboprophylaxis) within 90 days after randomisation; Fig. 2 . No difference in the incidence of the primary outcome was observed between the two arms (adjusted relative risk: 1.00 95 % CI: 0.44–2.25; p-value 0.99). All events were represented by untoward hospitalisations. A total of 19 of 22 hospitalisations were classified as being COVID-19-related. No deaths were recorded.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes.

| Intention-to-treat population | Enoxaparin group (n = 234) | Standard of care group (n = 238) | Adjusted RRa (95 % CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome (90-day follow-up) | ||||

| Any untoward hospitalisation and all-cause death | 11 (4.7) | 11 (4.6) | 1.00 (0.44–2.3) | 0.99 |

| Any untoward hospitalisation | 11 (4.7) | 11 (4.6) | 1.00 (0.44–2.3) | 0.99 |

| All-cause death | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| Intention-to-treat population | Enoxaparin group (n = 233) | Standard of care group (n = 237) | Unadjusted RR (95 % CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary efficacy outcomes (90-day follow-up) | ||||

| Cardiovascular events | 2 (0.9) | 4 (1.7) | 0.51 (0.09–2.75) | 0.43 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (0.4) | 4 (1.7) | 0.26 (0.03–2.27) | 0.22 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 1 (0.4) | 0 | – | – |

| Other cardiovascular eventsb | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| COVID-19-related hospitalisation | 9 (3.9) | 10 (4.2) | 0.92 (0.38–2.21) | 0.84 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| Safety population | Enoxaparin group (n = 230) | Standard of care group (n = 238) | Unadjusted RR (95 % CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety outcomes (90-day follow-up) | ||||

| Major bleeding | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| Non-major clinically relevant bleeding | 0 | 0 | – | – |

All arterial and venous cardiovascular events were symptomatic and occurred during the first 30 days of follow-up.

Relative Risk (RR) was adjusted for age (stratification variable), as pre-specified in the study protocol.

Other cardiovascular events include deep vein thrombosis, myocardial infarction, arterial ischaemia, myocarditis, and acute splanchnic vein thrombosis.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence of the primary outcome within 90 days after randomisation.

The primary outcome consisted of a composite of untoward hospitalisation and all-cause death.

A major cardiovascular event occurred in two (0.9 %) patients of the enoxaparin arm vs. four (1.7 %) of the standard-of-care arm, resulting in a risk ratio of 0.51 (95 % CI: 0.09–2.75; p-value 0.43). All cardiovascular events were symptomatic and occurred within 30 days after randomisation. One (0.4 %) ischaemic stroke and one (0.4 %) pulmonary embolism episode was reported in patients treated with enoxaparin, whereas four (1.7 %) pulmonary embolism episodes occurred in controls (risk ratio for pulmonary embolism 0.26; 95 % CI: 0.03–2.27; p-value 0.22). No ischaemic stroke events were observed in controls. No major or clinically-relevant-non-major bleeding episodes (primary safety outcome) were recorded. No patient in the enoxaparin group had to discontinue the treatment due to toxicity or adverse events.

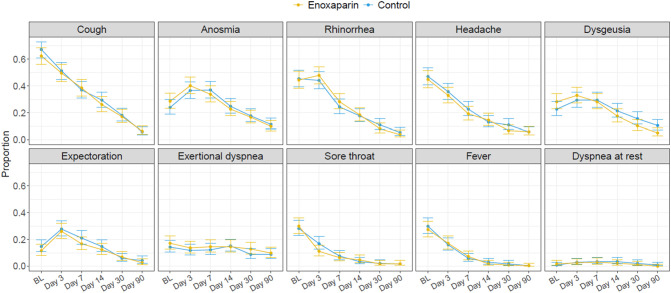

The prevalence of all COVID-19-related symptoms showed a steady declining trend over 90 days; Fig. 3 . The time-depending prevalence of COVID-19-related signs and symptoms were similar in the two treatment arms during follow-up with almost completely overlapping confidence intervals for each symptom. At Day 90, the prevalence of individuals with COVID-19-related symptoms was <12 % in both groups and <10 % for individual respiratory symptoms. A total of 42 (17.9 %) patients in the enoxaparin group and 40 (16.8 %) patients in the control group reported the persistence of at least one respiratory symptom (cough, rhinorrhea, expectoration, sore throat, or dyspnea) at the time of the 90-day follow-up visit.

Fig. 3.

Proportion of patients with COVID-19-related symptoms over 90-day follow-up.

Predefined study visits took place in hospital (baseline, BL) and telephonically (Day 3, 7, 14, 30, and 90). Information of COVID-19-related symptoms was collected prospectively by trained personnel following a structured questionnaire.

4. Discussion

In this academic, multinational, phase III, randomised controlled trial of outpatients with symptomatic COVID-19, we showed that thromboprophylaxis with enoxaparin (vs. no thromboprophylaxis) led neither to a reduction of the primary outcome (untoward hospitalisation and death) nor to an improvement of COVID-19-related symptoms within 90 days follow-up. Symptoms of COVID-19 persisted in approximately one in eight patients, indicating that the burden of disease extends after the acute phase in a substantial proportion of subjects. Residual symptoms falling under the definition of post-COVID-19 syndrome should be object of further investigation and targeted interventions.

With respect to the primary outcome, the results of the 90-day data analysis are consistent with those of the primary analysis focusing on the first 30 days of follow-up [9]. Most events occurred in the first 10 days after enrolment when patients were still under active anticoagulant treatment. Therefore, an extension of thromboprophylaxis with enoxaparin is unlikely to provide additional benefit. This finding is consistent with other studies investigating the impact of apixaban and aspirin [8], rivaroxaban [11] and enoxaparin [10] vs. no antithrombotic treatment in a similar population of COVID-19 outpatients. All studies reported a rate of hospitalisation or early serious complications of approximately 3–4 % with the exception of one study [10] that recorded 21-day incidence of >10 %. The relatively low incidence of the primary outcome may be explained by the under-representation of high-risk groups, including older patients and subjects with cancer, prior venous thromboembolism, or severe comorbidities. Cohort data showed that the risk of hospitalisation and death peaked in these groups [18], [19], [20], [21]. Furthermore, novel virus variants that emerged during the execution phase of the abovementioned studies and the experience accumulated in the treatment course of COVID-19 likely played a role in determining the course and prognosis of the disease.

Early observational studies demonstrated a high rate of arterial and venous thromboembolic events in inpatients with COVID-19 [1], [2], [3]. OVID and other aforementioned trials were not powered for this outcome and did not implement ad hoc strategies to routinely screen outpatients for venous thromboembolic events. The reduction in the 30-day risk of acute pulmonary embolism observed in OVID (0.4 % vs. 1.7 %) did not reach statistical significance and should be considered hypothesis generating. Ongoing studies and a comprehensive, collaborative meta-analysis of published trials will help to address this question.

The post-COVID-19 syndrome emerged as an alarming complication impairing the well-being and functional status of COVID-19 survivors [13]. We investigated whether early enoxaparin may accelerate the resolution of symptoms, provided that all subjects enrolled in OVID were initially symptomatic (or had a body temperature >37.5 °C) and have been prospectively followed also for the characteristics and course of symptoms. We showed that an improvement of COVID-19-related symptoms was observed in most patients during follow-up. However, approximately one in eight patients presented with residual respiratory symptoms at the time of the 90-day follow-up visit. It has been shown that the post-COVID-19 syndrome can affect the whole spectrum of COVID-19 patients [22], [23]. Approximately 10–35 % of outpatients up to 85 % of admitted patients could present with functional or organ impairment months after the acute phase [12], [24]. The five most common symptoms were fatigue (58 %), headache (44 %), attention disorder (27 %), hair loss (25 %), and dyspnea (24 %). [25], [26], [27] We showed that early thromboprophylaxis with enoxaparin did not accelerate the resolution of ten different individual symptoms and did not appear to reduce the proportion of patients with residual respiratory symptoms of COVID-19. Whether it could play a role during long-term follow-up remains to be investigated.

This study has limitations. First, due to logistical reasons we were unable to enroll high-risk outpatients aged 70 years or older. Consequently, this led to a lower-than-expected event rate and early termination of the trial. Second, the trial has an open-label design that could have influenced the decision to perform diagnostic imaging for acute pulmonary embolism or to admit patients to hospital. Third, no external validation of the primary outcome events has been performed: this may have played a role as criteria (and limits) for hospital admission varied over time. Finally, we could not pre-define the criteria for post-COVID-19 syndrome as this complication was not foreseeable when the pandemic started. Post-COVID conditions and syndromes can include a very wide spectrum of health problems including but not limited to general symptoms, respiratory and cardiopulmonary manifestations, neurological dysfunctions, digestive symptoms and other disturbances. In our analysis, we collected information on clinical characteristics of COVID-19 based on a structured questionnaire including the most prevalent disease manifestations described in the medical literature during the first months of the pandemic.

In conclusion, early thromboprophylaxis with enoxaparin did not appear to improve the course of acute COVID-19 in terms of hospitalisation, deaths, and COVID-19-related symptoms in adult outpatients during 90-day follow-up. It should be further investigated if early thromboprophylaxis would lead to an improvement of functional outcomes and quality of life over the long-term perspective.

Funding

SNSF (National Research Programme COVID-19 NRP78: 198352), University Hospital Zurich, University of Zurich, Dr.-Ing. Georg Pollert (Berlin), Johanna Dürmüller-Bol Foundation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Bernhard Gerber reports non-financial support and funding for an accredited continuing medical education programme from Axonlab, and Thermo Fisher Scientific; personal fees and funding for an accredited continuing medical education programme from Alnylam, Pfizer, and Sanofi; funding for an accredited continuing medical education programme from Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Takeda, Octapharma, SOBI, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, Mitsubishi Pfizer, Tanabe Pharma, outside the submitted work. Stavros V. Konstantinides reports grants or contracts from Bayer AG; consulting fees from Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, and Boston Scientific; and payment or honoraria from Bayer, INARI Medical, MSD, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Stefan Stortecky reports research grants from Edwards Lifesciences to the institution, research grants from Medtronic to the institution, research grants from Boston Scientific to the institution, research grants from Abbott to the institution, personal fees from Boston Scientific, from Teleflex, from BTG –Boston Scientific outside the submitted work. Helia Robert-Ebadi reports speaker honoraria from Daichi-Sankyo, and Bayer. David Spirk reports employment by Sanofi-Aventis Switzerland. Daniel Duerschmied reports research support from German Research Foundation, CytoSorbents, Haemonetic; consulting and speaker's fees from Bayer Healthcare, Daiichi Sankyo, LEO Pharma, AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, and BMS–Pfizer. Nils Kucher reports institutional research grants from Concept Medical, Bard, Bentley, Boston Scientific, INARI, Sanofi, and Bayer; and personal fees from Concept Medical, Bayer, Boston Scientific, and INARI. Stefano Barco reports institutional research grants from Concept Medical, Bard, Bentley, Boston Scientific, INARI, Sanofi, and Bayer; and personal fees from Concept Medical, Bayer, Boston Scientific, and INARI. All other authors do not report any conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The OVID study was an independent, investigator-initiated, phase III trial with an academic sponsor (University of Zurich) and was primarily funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF) in the frame of the National Research Programme COVID-19 (NRP 78; #198352). Additionally, the sponsor received unrestricted financial support for the conduct of the study from the following public institutions or foundations: University Hospital Zurich (Innovation Pool), University of Zurich (UZH Forschungsförderung), Georg Pollert (Berlin), and Johanna Dürmüller-Bol Foundation. DD is a member of SFB1425, funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—Project #422681845. We thank all patients for having agreed to participate in the OVID study and their families for having provided support. Particular gratitude goes to all study managers, nurses, physicians, and students involved in the preparation and conduct of the study. We thank all general practitioners for additional logistical support particularly with the dissemination of the study. We also thank the members of the independent data and safety monitoring board for their invaluable advice. No medical writer was involved in the creation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2022.10.021.

Appendix. Supplementary data

Appendix A, Supplementary data

References

- 1.Bikdeli B., Madhavan M.V., Jimenez D., Chuich T., Dreyfus I., Driggin E., Nigoghossian C., Ageno W., Madjid M., Guo Y., Tang L.V., Hu Y., Giri J., Cushman M., Quéré I., Dimakakos E.P., Gibson C.M., Lippi G., Favaloro E.J., Fareed J., Caprini J.A., Tafur A.J., Burton J.R., Francese D.P., Wang E.Y., Falanga A., McLintock C., Hunt B.J., Spyropoulos A.C., Barnes G.D., Eikelboom J.W., Weinberg I., Schulman S., Carrier M., Piazza G., Beckman J.A., Steg P.G., Stone G.W., Rosenkranz S., Goldhaber S.Z., Parikh S.A., Monreal M., Krumholz H.M., Konstantinides S.V., Weitz J.I., Lip G.Y.H. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020;75:2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klok F.A., Kruip M., van der Meer N.J.M., Arbous M.S., Gommers D., Kant K.M., Kaptein F.H.J., van Paassen J., Stals M.A.M., Huisman M.V., Endeman H. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19: an updated analysis. Thromb. Res. 2020;191:148–150. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avila J., Long B., Holladay D., Gottlieb M. Thrombotic complications of COVID-19. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021;39:213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta A., Madhavan M.V., Sehgal K., Nair N., Mahajan S., Sehrawat T.S., Bikdeli B., Ahluwalia N., Ausiello J.C., Wan E.Y., Freedberg D.E., Kirtane A.J., Parikh S.A., Maurer M.S., Nordvig A.S., Accili D., Bathon J.M., Mohan S., Bauer K.A., Leon M.B., Krumholz H.M., Uriel N., Mehra M.R., Elkind M.S.V., Stone G.W., Schwartz A., Ho D.D., Bilezikian J.P., Landry D.W. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1017–1032. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behzad S., Aghaghazvini L., Radmard A.R., Gholamrezanezhad A. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19: radiologic and clinical overview. Clin. Imaging. 2020;66:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libby P., Lüscher T. COVID-19 is, in the end, an endothelial disease. Eur. Heart J. 2020;41:3038–3044. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abou-Ismail M.Y., Diamond A., Kapoor S., Arafah Y., Nayak L. The hypercoagulable state in COVID-19: incidence, pathophysiology, and management. Thromb. Res. 2020;194:101–115. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connors J.M., Brooks M.M., Sciurba F.C., Krishnan J.A., Bledsoe J.R., Kindzelski A., Baucom A.L., Kirwan B.A., Eng H., Martin D., Zaharris E., Everett B., Castro L., Shapiro N.L., Lin J.Y., Hou P.C., Pepine C.J., Handberg E., Haight D.O., Wilson J.W., Majercik S., Fu Z., Zhong Y., Venugopal V., Beach S., Wisniewski S., Ridker P.M. Effect of antithrombotic therapy on clinical outcomes in outpatients with clinically stable symptomatic COVID-19: the ACTIV-4B randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326:1703–1712. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.17272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barco S., Voci D., Held U., Sebastian T., Bingisser R., Colucci G., Duerschmied D., Frenk A., Gerber B., Götschi A., Konstantinides S.V., Mach F., Robert-Ebadi H., Rosemann T., Simon N.R., Spechbach H., Spirk D., Stortecky S., Vaisnora L., Righini M., Kucher N. Enoxaparin for primary thromboprophylaxis in symptomatic outpatients with COVID-19 (OVID): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022 doi: 10.1016/s2352-3026(22)00175-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cools F., Virdone S., Sawhney J., Lopes R.D., Jacobson B., Arcelus J.I., Hobbs F.D.R., Gibbs H., Himmelreich J.C.L., MacCallum P., Schellong S., Haas S., Turpie A.G.G., Ageno W., Rocha A.T., Kayani G., Pieper K., Kakkar A.K. Thromboprophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin versus standard of care in unvaccinated, at-risk outpatients with COVID-19 (ETHIC): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022 doi: 10.1016/s2352-3026(22)00173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ananworanich J., Mogg R., Dunne M.W., Bassyouni M., David C.V., Gonzalez E., Rogalski-Salter T., Shih H., Silverman J., Medema J., Heaton P. Randomized study of rivaroxaban vs. placebo on disease progression and symptoms resolution in high-risk adults with mild COVID-19. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenhalgh T., Knight M., A'Court C., Buxton M., Husain L. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ. 2020;370 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tenforde M.W., Kim S.S., Lindsell C.J., Billig Rose E., Shapiro N.I., Files D.C., Gibbs K.W., Erickson H.L., Steingrub J.S., Smithline H.A., Gong M.N., Aboodi M.S., Exline M.C., Henning D.J., Wilson J.G., Khan A., Qadir N., Brown S.M., Peltan I.D., Rice T.W., Hager D.N., Ginde A.A., Stubblefield W.B., Patel M.M., Self W.H., Feldstein L.R. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network - United States, March-June 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:993–998. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barco S., Bingisser R., Colucci G., Frenk A., Gerber B., Held U., Mach F., Mazzolai L., Righini M., Rosemann T., Sebastian T., Spescha R., Stortecky S., Windecker S., Kucher N. Enoxaparin for primary thromboprophylaxis in ambulatory patients with coronavirus disease-2019 (the OVID study): a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21:770. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04678-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samama M.M., Cohen A.T., Darmon J.Y., Desjardins L., Eldor A., Janbon C., Leizorovicz A., Nguyen H., Olsson C.G., Turpie A.G., Weisslinger N. A comparison of enoxaparin with placebo for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients. Prophylaxis in medical patients with enoxaparin study group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;341:793–800. doi: 10.1056/nejm199909093411103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakkar A.K., Cimminiello C., Goldhaber S.Z., Parakh R., Wang C., Bergmann J.F. Low-molecular-weight heparin and mortality in acutely ill medical patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:2463–2472. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1111288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bajaj N.S., Vaduganathan M., Qamar A., Gupta K., Gupta A., Golwala H., Butler J., Goldhaber S.Z., Mehra M.R. Extended prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism after hospitalization for medical illness: a trial sequential and cumulative meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2019;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang L., Hou J., Ma F.Z., Li J., Xue S., Xu Z.G. The common risk factors for progression and mortality in COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. Arch. Virol. 2021;166:2071–2087. doi: 10.1007/s00705-021-05012-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lodigiani C., Iapichino G., Carenzo L., Cecconi M., Ferrazzi P., Sebastian T., Kucher N., Studt J.D., Sacco C., Bertuzzi A., Sandri M.T., Barco S. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan,Italy. Thromb. Res. 2020;191:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mo J., Liu J., Wu S., Lü A., Xiao L., Chen D., Zhou Y., Liang L., Liu X., Zhao J. Predictive role of clinical features in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 for severe disease. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2020;45:536–541. doi: 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2020.200384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie J., Wang Q., Xu Y., Zhang T., Chen L., Zuo X., Liu J., Huang L., Zhan P., Lv T., Song Y. Clinical characteristics, laboratory abnormalities and CT findings of COVID-19 patients and risk factors of severe disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann.Palliat. Med. 2021;10:1928–1949. doi: 10.21037/apm-20-1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crook H., Raza S., Nowell J., Young M., Edison P. Long covid-mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmad M.S., Shaik R.A., Ahmad R.K., Yusuf M., Khan M., Almutairi A.B., Alghuyaythat W.K.Z., Almutairi S.B. "LONG COVID": an insight. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021;25:5561–5577. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202109_26669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dennis A., Wamil M., Alberts J., Oben J., Cuthbertson D.J., Wootton D., Crooks M., Gabbay M., Brady M., Hishmeh L., Attree E., Heightman M., Banerjee R., Banerjee A. Multiorgan impairment in low-risk individuals with post-COVID-19 syndrome: a prospective, community-based study. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Leon S., Wegman-Ostrosky T., Perelman C., Sepulveda R., Rebolledo P.A., Cuapio A., Villapol S. medRxiv; 2021. More Than 50 Long-term Effects of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen M.S., Kristiansen M.F., Hanusson K.D., Danielsen M.E., B ÁS, Gaini S., Strøm M., Weihe P. Long COVID in the Faroe islands: a longitudinal study among nonhospitalized patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;73:e4058–e4063. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Subramanian A., Nirantharakumar K., Hughes S., Myles P., Williams T., Gokhale K.M., Taverner T., Chandan J.S., Brown K., Simms-Williams N., Shah A.D., Singh M., Kidy F., Okoth K., Hotham R., Bashir N., Cockburn N., Lee S.I., Turner G.M., Gkoutos G.V., Aiyegbusi O.L., McMullan C., Denniston A.K., Sapey E., Lord J.M., Wraith D.C., Leggett E., Iles C., Marshall T., Price M.J., Marwaha S., Davies E.H., Jackson L.J., Matthews K.L., Camaradou J., Calvert M., Haroon S. Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat. Med. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01909-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A, Supplementary data