Abstract

Although often considered a strict human pathogen, Streptococcus pneumoniae has been reported to infect and cause pneumonia in horses, although the pathology appears restricted compared to that of human infections. Here we report on the molecular characterization of a group of S. pneumoniae isolates obtained from horses in England and Ireland. Despite being obtained from geographically distinct locations, the isolates were found to represent a tight clonal group, virtually identical to each other but genetically distinguishable from more than 120 divergent isolates of human S. pneumoniae. A comprehensive analysis of known pneumococcal virulence determinants was undertaken in an attempt to understand the pathogenicity of equine pneumococci. Surprisingly, equine isolates appear to lack activities associated with both the hemolytic cytotoxin pneumolysin, often considered a major virulence factor of pneumococci, and the major autolysin gene lytA, also considered an important virulence factor. In support of phenotypic data, molecular studies demonstrated a deletion of parts of the coding sequences of both lytA and ply genes in equine pneumococci. The implications of these findings for the evolution and pathogenicity of equine S. pneumoniae are discussed.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a common and important human pathogen causing a wide variety of diseases, including pneumonia, otitis media, meningitis, and bacteremia. S. pneumoniae was reported to be pathogenic in horses as long ago as 1928 (22). Since that time there have been sporadic reports of isolations of S. pneumoniae from the equine respiratory tract (1, 2, 11), although until recently, there was little direct evidence associating these isolates with disease. However, S. pneumoniae has been isolated from pneumonic foals (17, 29) and has been associated with lower airway disease in training thoroughbreds (4, 16). Blunden et al. (3) provided the first direct evidence that S. pneumoniae can act as a primary pathogen in horses. Experimental infection of ponies was shown to result in the development of clinical respiratory disease with fever, cough, and ocular and nasal discharge, and evidence of a lobar pneumonia, from which S. pneumoniae could be isolated in pure culture or demonstrated by immunostaining, was seen post mortem. The disease experimentally reproduced in ponies by S. pneumoniae challenge (3) was less severe than the typical lobar pneumonia seen in humans, although the histopathological features of the lesions were very similar. However, natural disease can vary in severity. A more severe pneumonia with bacteremia is infrequently seen in foals (17), whereas upper and lower respiratory tract inflammation is more commonly observed in thoroughbreds, mainly affecting 2 year olds, where it compromises training (29). There is no evidence of otitis media caused by S. pneumoniae in the horse.

Little is known regarding the relationship of equine S. pneumoniae isolates to their human counterparts. Interestingly, all equine isolates reported to date are of capsular serotype 3 (5), but there is no data regarding the relationship of these strains to human serotype 3 pneumococci. It is still unclear whether equine isolates can infect humans, whether human isolates can infect horses, or whether equine isolates form an entirely distinct population. However, only S. pneumoniae serotype 9 was isolated from the staff of a training yard that contained S. pneumoniae-infected horses (4). To address these issues, we have performed a preliminary molecular characterization of equine pneumococcus isolates in order to examine the genetic and evolutionary relationships of various equine S. pneumoniae isolates among themselves and to human S. pneumoniae isolates and to examine the molecular basis of the pathogenicity of this bacterium in horses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture conditions.

Isolates were cultured on brain heart infusion agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood at 37°C and 5% CO2. The species designations of isolates were confirmed by serotyping and optochin susceptibility and by a species-specific 16S RNA gene probe (GenProbe Inc., San Diego, Calif.).

Strains.

The equine S. pneumoniae strains used in this study, isolated from either the nasopharynx of horses with upper respiratory tract infection or the tracheal washes of horses showing poor training performance, are listed in Table 1. The details of human serotype 3 isolates, used in restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of housekeeping genes, are given in Table 2. Ten human isolates of S. pneumoniae, selected on the basis of a population genetic study (21) to represent divergent members of the species, were used in phylogenetic analyses. The strains, geographic origins, sites and years of isolation, and serotypes of these isolates were as follows: 1012, Manchester (United Kingdom), throat, 1993, 35; Sp8, Spain, blood, 1988, 13; E226, Uruguay, blood, 1995, 1; Sp9, Spain, blood, 1988, 8; KD12, Kenya, sputum, 1991, 7; 951, Oxford (United Kingdom), throat, 1994, 6A; 912, Oxford (United Kingdom), throat, 1996, 15B; 873, Kenya, throat, 1990, 8; 1011, Manchester (United Kingdom), throat, 1993, 23; and R6, United States, cerebrospinal fluid, 1930s, nonserotypeable. The type strains of Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus oralis, NCTC12261 and NCTC11427, respectively, were also included in this analysis. The well-characterized S. pneumoniae strain D39 (NCTC7466), used as a control in hemolytic titer assays, is a reference serotype 2 strain.

TABLE 1.

Equine isolates used in this studya

| Warwick strain no. | Supplier’s strain no. | Yr isolated | Site of isolation | Country/county of isolatione | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 495/Pn138 | 409 | 1993 | Nasopharynx | United Kingdom/West Suffolk | N. Chanterb |

| 496/Pn139 | 7731 | 1992 | Nasopharynx | United Kingdom/West Suffolk | N. Chanter |

| 497/Pn140 | 600142 | 1996 | Nasopharynx | United Kingdom/West Suffolk | N. Chanter |

| 498/Pn141 | 3307 | 1992 | Nasopharynx | United Kingdom/West Sussex | N. Chanter |

| 499/Pn142 | 4826 | 1992 | Nasopharynx | United Kingdom/West Suffolk | N. Chanter |

| 500/Pn143d | 4778 | 1992 | Tracheal wash | United Kingdom/East Suffolk | N. Chanter |

| 501/Pn144 | 5330 | 1992 | Nasopharynx | United Kingdom/West Suffolk | N. Chanter |

| 502/Pn145 | 21 | 1987 | Tracheal wash | Ireland | J. F. Timoneyc |

| 503/Pn146 | 5 | 1987 | Tracheal wash | Ireland | J. F. Timoney |

| 504/Pn147 | 15 | 1987 | Tracheal wash | Ireland | J. F. Timoney |

| 505/Pn148 | 17 | 1987 | Tracheal wash | Ireland | J. F. Timoney |

All strains tested were optochin sensitive and bound a 16S RNA, species-specific gene probe.

Animal Health Trust, Newmarket, United Kingdom.

Gluck Equine Research Center, University of Kentucky.

Isolate 500 was not examined in RFLP studies of housekeeping genes and virulence factors.

All West Suffolk isolates originated from distinct stables.

TABLE 2.

RFLP analysis of housekeeping genes from equine and human clinical isolates of serotype 3 pneumococci isolated from the United Kingdom

| Strain | Place of isolation | Allele designation of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hexA | recP | polI | hexB | ddl | trpB-trpA | ||

| 480 | Portsmoutha | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 476 (GBO5) | Leicesterb | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 471 (SPO1) | Leicesterb | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 470 (WU2) | Leicesterb | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 494 | Liverpoola | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 483 | Sheffielda | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| 481 | Tootinga | 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Equine isolatesc | 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 6 | |

Generously provided by A. Efstratiou, Central Public Health Laboratory, Colindale, United Kingdom.

Generously provided by T. Mitchell, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom.

All equine isolates gave identical RFLP profiles.

Preparation of chromosomal DNA.

Chromosomal DNA was prepared from all isolates used, including 10 diverse human isolates of S. pneumoniae and the type strains of S. oralis and S. mitis, as described previously (28).

Clonal analysis.

RFLP analyses of both virulence factor- and housekeeping-protein-encoding genes were performed following the amplifications of the appropriate products by PCR. For housekeeping gene analysis, products representing hexA (DNA mismatch repair protein), recP (transketolase), polI (DNA polymerase I), hexB (DNA mismatch repair protein), ddl (d-alanine-d-alanine ligase), and trpB-trpA (tryptophan biosynthetic cluster) were used. PCR products were obtained by using the following primer sets: hexAup (5′CCGACAATCCGATCCCTATGG3′) and hexAdn (5′TATCAGCTGGTCCCGGTTCAATC3′), recPup (5′ACCGCGACCGCTTTATTCTTTC3′) and recPdn (5′ATGCTGACTACGCGGGATTTTTC3′), polIup (5′TCGGGCCAAGACTCCTGATGA3′) and polIdn (5′CGCCTCCCGCACCACTTC3′), hexBup (5′CCATTGACGCGGGCTCTA3′) and hexBdn (5′CCTGAATACGTCGGAACATCTTT3′), ddlup (5′CTCCGGGGGCAAGAAGAC3′) and ddldn 5′CAATGGCACGGAAGGCTGT3′, and trpBup (5′CTAGTAGCCTGTGTTGGT3′) and trpAdn (5′TCGAACCGACGATAACAC3′). Sequences of hexA, recP, polI, and hexB were available in GenBank, while sequences of ddl and trpB-trpA were kindly provided by Martin Burnham of SmithKline Beecham. PCR products corresponding to virulence factor genes encoding two neuraminidases (nanA and nanB), the pneumococcal surface protein (pspA), and hyaluronidase (hyl) were obtained by using the primer sets nanAup (5′TCAACTTTCGGGGGAGAGC3′) and nanAdn (5′TGGAGCGAATTATAGGCAAACT3′), nanBup (5′TTCTTGTGTAGGCATTAGTCTTTT3′) and nanBdn (5′ATCGCAGAATAGGCATAACCAT3′), pspAup (5′AAAGAGATTGATGAGTCTGA3′) and pspAdn (5′TTAAACCCATTCACCATTGG3′), and hylup (5′TGCAACGACGTCAGGAACAAAG3′) and hyldn (5′ACGGAATAAATAAAACGCCCCAAGTA3′), respectively. PCR was performed under standard conditions with 32 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, X°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, where X°C represents an annealing temperature appropriate for the particular primer set used. PCR products were digested with a number of frequently cutting restriction enzymes as described below, and the resulting profiles were resolved on 4 and 8% polyacrylamide gels.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Fragments carrying the housekeeping genes hexB, recP, and xpt (encoding xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase) were amplified by PCR by using the hexB and recP primer sets described above and the xpt primer set xptup (5′GAAATTATTAGAAGARCGCATC3′) and xptdn (5′TTAGAGATCTGCCTCCWTRAA3′), respectively (where R and W are A or G and A or T, respectively), with standard PCR conditions. Fragments were purified through Qiagen PCR purification columns and sequenced directly by using the same primers and an ABI373 automated sequencing system. Sequences of 395 bp (xptup), 288 bp (hexBup), 351 bp (hexBdn), 327 bp (recPup), and 339 bp (recPdn) were obtained from each isolate and combined for phylogenetic analyses performed with the MEGA software (15). Phylogenetic trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method with the Jukes-Cantor correction, and the bootstrap confidence level of internal branches was calculated with 500 resamplings of the data.

Genetic and phenotypic analyses of the ply locus.

Three primer sets, plyup (5′TTGTTGTTATCGAAAGAAAGAAGCGGA3′) and plydn (5′AAACCGTACGCCACCATTCCCA3′) (located within the pneumolysin-coding sequence [ply]), plyconup (5′CGAAAGAAAGAAGC3′) and plycondn (5′CGTACGCCACCATT3′) (located outside ply), and plydegup (5′TGGMATSAIRAITAT3′) and plydegdn (5′CCACCATTCCCAIGC3′) (designed on the basis of conserved sequences identified within members of the thiol-activated toxin family) (where M, S, R, and I are A or C, C or G, A or G, and deoxyinosine, respectively), were used to attempt to amplify ply from equine pneumococci.

The presence of the lytA-ply fusion in equine isolates was confirmed by using primer C (5′TTGGGGGCGGTTGGAATGC3′), corresponding to bases 231 to 249 of the lytA coding sequence, in conjunction with primer INT (5′TGGTAGAGGACTTGATTCA3′), corresponding to bases 926 to 944 of ply.

Southern blot analyses were performed with the Boehringer digoxigenin (DIG) system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Pneumolysin probes, representing internal fragments of the ply gene (obtained by using primer set plyup and plydn or plyup and horply [5′ATTATCCTCTACCGTTACAGT3′]), were obtained by using DIG-High Prime to label a ply fragment amplified from S. pneumoniae R6. These probes were used to probe EcoRV- and PvuII-digested chromosomal DNA from equine pneumococci.

Hemolytic titer assays were performed by using cultures grown in brain heart infusion broth to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of approximately 0.3. Cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended to an OD600 of 0.6. The cell suspension was then sonicated and lysis of pneumococci was confirmed both by clearance of the cell suspension and by the absence of viable cells as determined by plating sonicant onto blood agar. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and serial doubling dilutions of lysate in PBS were prepared. A standard erythrocyte suspension was prepared by diluting washed cells in PBS to an OD600 of 0.8. For each assay, 40 μl of erythrocytes was added to 160 μl of lysate and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Cell debris and unlysed erythrocytes were removed by centrifugation, and the degree of hemolysis was determined by measuring released heme spectrophotometrically at 410 nm. The reciprocal of the lowest dilution showing hemolytic activity was taken as the titer.

Analysis of lytA activity.

Bile solubility tests and assays monitoring degradation of choline-labelled cell walls were performed as described previously (8, 12). Southern blot analyses were performed with the Boehringer DIG system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A probe was constructed by amplifying a lytA fragment from S. pneumoniae R6 by using primers lytAup (5′ GGAGTAGAATATGGAAATTGATGTGAGTAA3′) and lytAdn (5′TTTATTTTACTGTAATCAAGCCATCTGGCTC3′), and it was used to probe for the presence of lytA in EcoRV-digested chromosomal DNA.

Analysis of competence genes.

PCR and the sequencing of genes in the com locus were performed as described previously (28).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All sequences used in the phylogenetic analyses performed with MEGA software have been deposited in EMBL and assigned accession no. AJ240606 to AJ240674. The sequence of the lytA to ply region of the equine pneumococcus has been assigned accession no. AJ240675.

RESULTS

Confirmation of species designation.

All 11 isolates were examined on receipt, as summarized in Table 1, to confirm their presumptive identification as S. pneumoniae. When cultured on blood agar, all isolates were found to yield optochin-sensitive colonies with a highly mucoid appearance characteristic of serotype 3 pneumococcal isolates. All isolates were confirmed as S. pneumoniae by using the Accuprobe S. pneumoniae culture identification test, a highly sensitive test based on a probe to an rRNA gene (6). However, atypically for S. pneumoniae, all isolates were found to be bile insoluble.

Equine pneumococci represent a tight clonal group.

In order to examine the relationships of the equine pneumococci to each other, PCR products representing six distinct housekeeping genes (recP, polI, ddl, trpB-trpA, hexA, and hexB) were obtained. Each PCR product was digested with at least four distinct frequently cutting restriction enzymes (recP was digested with Tsp509I, MnlI, HinfI, Hsp92II, and MaeIII; polI was digested with AluI, MseI, MboII, HhaI, HinfI, and DdeI; ddl was digested with Hsp92II, HaeIII/DdeI, BsrI, and MwoI; trpB-trpA was digested with HinfI, Tsp509I, MseI, and Hsp92II; hexA was digested with AluI, HhaI, HinfI, Tsp509I, and Hsp92II; and hexB was digested with AluI, StyI, FokI, MnlI, BfaI, and AciI) and subjected to RFLP analysis. In all cases the equine isolates showed identical RFLP patterns, suggesting that equine pneumococci represent a tight clonal group. A group of seven human serotype 3 S. pneumoniae clinical isolates were subjected to the same RFLP treatment. These isolates were selected to represent genetically diverse strains on the basis of preliminary studies of genetic variation of neuraminidase-encoding genes and surrounding regions in over 20 serotype 3 isolates (14). The results of this analysis are shown in Table 2 with each variant allele, determined by RFLP studies using multiple restriction enzymes, given a distinct arbitrary number. All seven human serotype 3 isolates gave distinct overall allelic profiles when compared by allelic variation at six loci. Although the equine isolates contain hexA, recP, polI, and hexB alleles which are also seen in some of the human type 3 isolates, the ddl and trpB-trpA alleles are unique, resulting in an equine allelic profile distinct from that of any of the human serotype 3 isolates examined in this study.

Equine pneumococci are closely related to human isolates.

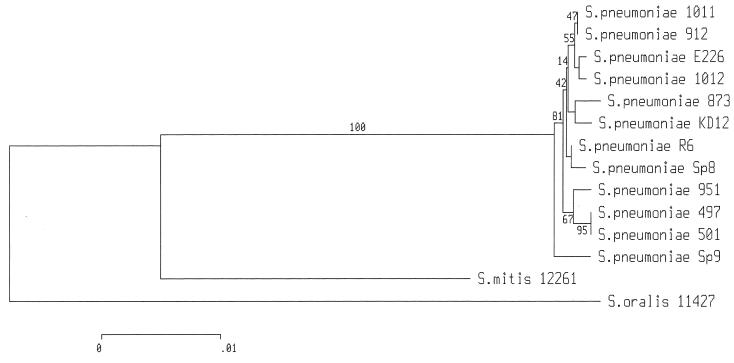

In order to further examine the relationship of equine to human S. pneumoniae, phylogenetic analysis was performed with data obtained by sequencing fragments of three distinct housekeeping genes (recP, hexB, and xpt) amplified from equine isolates 497 and 501 and from a diverse range of human pneumococci. The type strains of S. oralis and S. mitis were also included in this analysis. All the S. pneumoniae isolates examined appeared to be closely related to each other, with the maximum nucleotide divergence between any two isolates being only 0.77%. In agreement with the RFLP data described above, the two equine S. pneumoniae isolates were found to be identical to each other. The equine nucleotide sequence is distinct from those of all the human isolates examined here, although it is still closely related, being between 0.29 and 0.65% divergent from any of the human isolates. In all, only two polymorphic sites (one in xpt and one in recP) were unique to the two equine pneumococcal isolates. Phylogenetic analysis performed with combined sequence data from the three housekeeping genes (Fig. 1) clearly places the equine isolates in a group including the human isolates of S. pneumoniae.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the relationships between equine S. pneumoniae isolates 497 and 501, 10 diverse human S. pneumoniae isolates, and the type strains of S. oralis and S. mitis.

Analysis of virulence factors. (i) Pneumolysin.

Pneumolysin, a thiol-activated cytotoxin, is generally considered to be an important virulence factor of S. pneumoniae (23). No PCR product could be amplified from any of the equine isolates by using the primer set plyup and plydn, previously found to amplify ply from all examined human S. pneumoniae isolates. In order to allow for possible polymorphism in equine ply, alternative primer sets located outside the pneumolysin-coding sequence and degenerate primers were designed based on the consensus sequence of the thiol-activated toxin group. However, the use of these additional primer sets and all possible combinations of the three primer sets under nonstringent annealing conditions resulted in the amplification of only nonspecific PCR products.

In light of the failure to detect ply by PCR, hemolytic activity assays were performed to determine whether the isolates also lack the normal pneumolysin phenotype. Sonicated extracts of four equine isolates (497, 500, 501, and 504) and two human isolate controls (D39 and human serotype 3 clinical isolate 480) were tested for hemolytic activities against horse and human blood (Table 3). There was no evidence of hemolytic activity associated with the equine isolates when extracts were tested against either horse or human blood, while, in contrast, the two human isolates showed high levels of hemolytic activity against both human and horse blood.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of hemolytic titers of human and equine pneumococci

| Strain | Source | Hemolytic titer in blood from:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Horse | ||

| 480 | Human | >4,096 | 256 |

| D39 | Human | >4,096 | 512 |

| 504 | Horse | 0 | 0 |

| 497 | Horse | 0 | 0 |

| 501 | Horse | 0 | 0 |

| 500 | Horse | 0 | 0 |

In order to confirm the absence of ply in equine pneumococci, Southern blot analyses were performed by using probes representing both a 500-bp 5′ fragment and a central 1,191-bp fragment of S. pneumoniae R6 ply. In contrast to PCR results, both of these probes hybridized with equine pneumococcal DNA, producing a single band of a size distinct from that seen in human pneumococcal controls (data not shown). Thus, it appeared that, despite both the apparent lack of hemolytic activity and the inability to amplify the ply gene by PCR with primers located at either end of ply, at least a fragment of ply is present in the chromosome of equine pneumococci.

(ii) Autolysin.

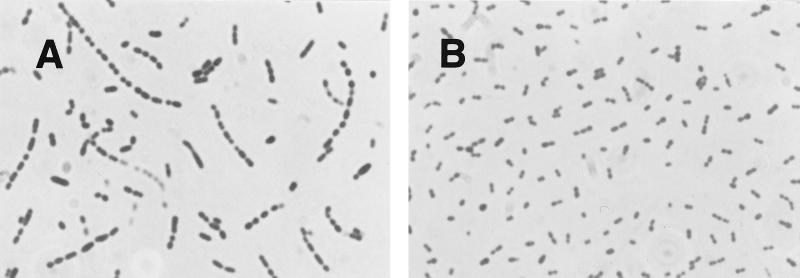

As previously mentioned, the equine pneumococci are unusual in that they are all bile insoluble. Bile solubility is considered a characteristic feature of pneumococci, and the basis of this phenotype is the activation of autolysin by bile. In order to confirm these observations more stringently, extracts prepared from two of the equine isolates, 497 and 501, were assayed for autolytic activity on choline-labelled cell walls. No evidence of autolytic activity was detected. Furthermore, microscopic examination of exponentially growing equine pneumococci revealed a chain-like morphology (Fig. 2) and not the diplococcal structure characteristic of S. pneumoniae. The use of a lytA probe in a Southern blot analysis demonstrated the presence of multiple bands (data not shown) with homology to the probe. Southern blot analyses performed with lytA probes are potentially difficult to interpret because of the frequent presence of homologous, bacteriophage lytic genes and proteins with homologous choline-binding domains. However, the blots provided no evidence that the lytA gene is absent from equine pneumococci.

FIG. 2.

Gram-stained exponential-phase culture of equine isolate 501 of S. pneumoniae (A) and human clinical serotype 3 S. pneumoniae isolate 1128 (B) cultured under identical conditions (magnification, ×100).

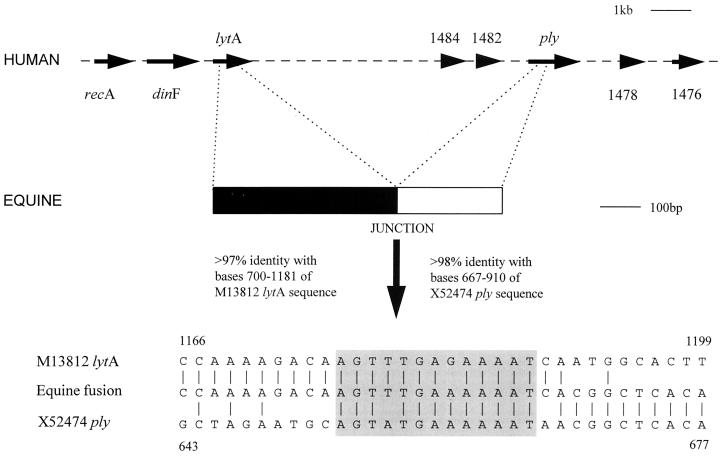

(iii) Detection of a lytA-ply fusion in equine pneumococci.

The genes encoding pneumolysin and autolysin are known to be closely linked in the genome, with ply situated some 7 kb downstream of lytA (12a). It was therefore considered possible that the apparent lack of the pneumolysin and autolysin phenotypes could be linked. While investigating this possibility, we amplified and fully sequenced a 730-bp PCR product. The PCR product was found to represent a fusion of the 5′ region of lytA with a sequence corresponding to ply, located some 450 bp downstream of the start codon (Fig. 3). The first 482 bp of the PCR product were over 97% identical with bases 700 to 1181 of the previously published lytA-containing sequence (GenBank accession no. M13812), while the remaining 3′ sequence showed over 98% identity with bases 667 to 910 of the previously published ply-containing sequence (GenBank accession no. X52474). The presence of this apparent deletion of 7 kb of DNA, including the 3′ region of lytA, the 5′ region of ply, and the entire intervening sequence, was confirmed by using primers to lytA and ply (C and INT) to amplify the junction region from all of the equine pneumococci. An identical product could not be amplified from human pneumococci.

FIG. 3.

Diagrammatic representation of the lytA-ply fusion generated by the deletion of the intervening sequence. The arrangement of the region in human pneumococci as determined by genome sequencing (26a) is shown at the top. Below, the sequence detected in equine pneumococci with a fusion of the lytA and ply sequences generated by a deletion event is illustrated. At the bottom, the sequence of the junction region is compared with the corresponding regions of the lytA and ply sequences. Bases identical to those seen in the equine sequence are marked (|) and illustrate the switch from lytA sequence at the 5′ end of the sequence shown to ply sequence at the 3′ end. The boxed region represents a sequence block conserved between lytA and ply coding sequences (11 of 13 bases) which corresponds to the lytA-ply junction.

(iv) Other virulence factors.

nanA and nanB, hyl, and pspA were all detected by PCR without difficulty. PCR products corresponding to these genes were amplified from 10 equine isolates and subjected to RFLP analyses with multiple, frequently cutting restriction enzymes. Restriction enzymes used were as follows: nanA was digested with DdeI, MnlI, TaqI, and Tsp509I; nanB was digested with DraI, NlaIII, TfiI, Tsp509I, and HaeIII/DdeI; pspA was digested with MseI and Tsp509I; and hyl was digested with DdeI, HaeIII, HinfI, MseI, and RsaI. RFLP analyses of these loci revealed no allelic variation (Table 4), with the single exception of one allelic variant of pspA from strain 501 which was slightly smaller than that of the remaining strains and resulted in one smaller band in the RFLP profile. It is possible that this size variation may reflect the loss of a repeat unit, as the pspA gene is known to be highly repetitive (31) and such bacterial surface proteins are prone to variation by the gain or loss of repeats (13). However, the alleles found at all these virulence factor loci in equine isolates were distinct from those seen in any of up to 122 human isolates (with diverse serotypes and isolated from different places on different dates) examined in the same manner (Table 4). These findings therefore confirm that equine isolates of pneumococci appear to consist of a clone distinct from any isolate seen to date in our extensive studies of the human pneumococcal population.

TABLE 4.

Analysis of the nature of putative virulence factors of equine pneumococci

| Gene | Virulence factor | Virulence factor present | Identical allele possessed by all equine isolates | Identical allele seen in human isolates (no. of human strains compared) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lytA | Autolysin | —a | ||

| ply | Pneumolysin | —a | ||

| nanA | Neuraminidase | Yes | Yes | No (20) |

| nanB | Neuraminidase | Yes | Yes | No (94) |

| pspA | Surface protein A | Yes | Yesb | NDc |

| hyl | Hyaluronidase | Yes | Yes | No (122) |

—, truncated inactive copy.

Except 501.

ND, not done.

Competence genes of equine pneumococci.

The comC gene of naturally transformable streptococci encodes a competence-stimulating peptide (CSP) which induces competence in the bacterial population at a critical extracellular concentration. The associated comD and comE genes encode a transmembrane histidine kinase and response regulator protein, respectively, of a two-component regulator, with the comD-encoded protein being a receptor for the CSP (20). The comC and 5′ comD genes were sequenced from two equine S. pneumoniae isolates, 496 and 505. Both were found to contain the CSP-1 allele which is characteristic of approximately 50% of the human pneumococci examined to date. The corresponding comD sequences were found to be identical to each other, characteristic of CSP-1-producing strains, and to contain only a single polymorphic site which distinguished them from all other known human pneumococci (28).

DISCUSSION

The results presented in this paper represent the first molecular characterization of S. pneumoniae isolates infecting nonhuman hosts. Serotype 3 pneumococci have been reported to cause respiratory tract infections in various breeds of horse, including hunters, Arabs, standardbreds, and thoroughbreds, for at least the past 25 years (1, 11). Eleven isolates of pneumococci were obtained from thoroughbred racehorses with respiratory tract infections from different stables in both England and Ireland over a period of almost 10 years. Extensive RFLP and sequencing analyses of both housekeeping-protein- and virulence factor-encoding genes in these organisms suggest that equine pneumococci represent a very tight clonal group closely related to human pneumococci. Phylogenetic analysis clearly shows that equine pneumococci cluster within the normal human-infecting population and do not form a separate, deeply branching group. The apparent uniformity among isolates could suggest that the movement of pneumococci from humans to horses was a relatively recent event and that the isolates examined are part of a recent epidemic clone that has spread throughout thoroughbreds.

ply of equine pneumococci.

It seems clear that, in spite of the apparently close genetic relationship between equine and human pneumococci, two loci, ply and lytA, often considered crucial to virulence in humans, are clearly different in equine pneumococci. Although pneumolysin is regarded as a diagnostic feature for pneumococci (25–27) and specific and degenerate PCR primers targeted to regions of the gene known to encode conserved domains within pneumolysin always resulted in amplification of ply from a diverse collection of human isolates, we were unable to amplify ply from any of the equine S. pneumoniae isolates. Neither was there any evidence for hemolytic activities among the isolates examined, even when they were assayed with horse blood. However, Southern blotting clearly demonstrated that ply-specific probes do hybridize to the genomic DNA of equine pneumococci. The reason for this discrepancy became clear with the identification of the lytA-ply fusion. Only a nonfunctional fragment of ply is present, explaining both the inability to amplify the gene by PCR and the lack of hemolytic activity.

lytA of equine pneumococci.

The major autolysin of pneumococci, LytA, responsible for the cleavage of peptidoglycan, is also considered a virulence factor. LytA may be important, both directly and indirectly, in the pathogenic process by mediating inflammation and by allowing the release of other nonexported virulence factors, such as pneumolysin, from the cell (19). Although no evidence for the absence of the lytA gene was obtained by Southern blotting, phenotypic evidence indicated no autolysin-associated activity. Microscopic examination of exponentially growing cultures showed that the equine pneumococci grew as chains rather than as characteristic diplococci. Interestingly, this equine chain phenotype is characteristic of lytA mutants previously constructed in human isolates (24). Furthermore, sonicated extracts prepared from two equine isolates and assayed for degradation of choline-labelled cell walls did not show any LytA activity.

A deletion event has disrupted both lytA and ply.

The discrepancy between the apparent presence of lytA and ply detected by Southern blotting and the lack of the associated phenotypes was resolved with the identification of an apparent deletion in equine pneumococci resulting in the loss of substantial fragments of both of these genes and the intervening sequence. The basis of this deletion becomes clear when the sequences of lytA and ply are compared with the sequence of the fusion junction, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The junction corresponds to a highly similar sequence (11 of 13 bases identical) seen in the previously published sequences of both lytA and ply. Therefore, it appears that the presence of this repeat sequence has mediated a recombination event resulting in the deletion of the sequence between the repeats. This event, resulting in the loss of substantial fragments of both lytA and ply as well as the intervening sequence, would clearly result in the inactivation of these genes. Indeed, it is of interest that the lytA sequence upstream of the junction has a G-to-T transversion at the equivalent of base 142 in lytA, generating a stop codon. This event may have occurred subsequent to the deletion event, preventing the production of a potentially toxic or metabolically wasteful fusion protein, since despite the deletion event, the fused truncated pneumolysin gene remains in frame with the autolysin gene.

A number of PCR primers were designed to confirm the absence of the region between lytA and ply. This region contains a number of predicted open reading frames (ORFs) (26a), although none, other than one (RPN1484) predicted to encode transposase, have been assigned any function based on sequence similarity. Thus, there appear to be no metabolically crucial genes in the region apparently deleted from equine pneumococci. Primers designed on the basis of regions corresponding to potential ORF RPN1482 and a region intergenic to potential ORFs RPN1484 and lytA did not result in amplification of PCR products from equine pneumococci. A product was obtained when a primer set corresponding to the predicted transposase ORF RPN1484 was used, but there are likely to be multiple copies of such an ORF within the chromosome. In contrast to the apparent absence of DNA corresponding to the regions between lytA and ply, primer sets corresponding to dinF and recA (upstream of lytA) and two potential ORFs, RPN1478 and RPN1476 (downstream of ply), produced PCR products with equine pneumococcal DNA. All of these findings are consistent with the deletion of the ca. 7-kb region between lytA and ply in equine pneumococci.

Phylogeny of equine isolates.

It is unclear whether the equine isolates retain the capacity to infect humans, although previous studies have indicated that farmworkers are usually colonized with pneumococci serotypically distinct from those infecting horses (4). Although the equine isolates retain a normal human CSP and receptor protein, illustrating that they could be induced to competence in the presence of human pneumococci, and human pneumococci possess an epidemic population structure (10, 21), suggesting that recombination is relatively frequent, the data presented here suggests that frequent transfer of DNA between equine and human pneumococci may not occur. Polymorphisms seen in the housekeeping genes xpt and recP were found to be unique to equine isolates when compared with pneumococcal isolates selected to represent the breadth of genetically divergent isolates and in comD when compared with the sequences of some 60 pneumococcal isolates (28). Interestingly, a recent study of the genetic variation of almost 300 isolates of invasive human pneumococci reported the presence of 35 distinct xpt alleles (7). None of the 35 alleles contained the unique polymorphism associated with the equine isolates found in this study. Additionally, equine isolates appear to possess distinct alleles of virulence factor genes for neuramindases A and B and hyaluronidase. Although the sampling in this study is clearly not exhaustive and the possibility of the equine alleles being found in some human pneumococci cannot be ruled out, the results suggest that equine pneumococci may represent a subpopulation ecologically isolated from other pneumococci.

Pathogenicity of equine pneumococci.

The implications of the alterations in genes believed to encode two of the major virulence factors of S. pneumoniae for that organism’s pathogenicity in horses remain unclear. Although functional pneumolysin and autolysin are important in several murine models of infection and a functional pneumolysin is responsible for damage to the ciliated cells in the respiratory tract, there is evidence that the inactivation of pneumolysin in some human S. pneumoniae isolates has little impact upon their virulence in some models of infection (18). Although the extent of lung pathology seen in horses is generally less than that seen in lobar pneumonia in humans, the overall severity of pneumococcal disease seen in the two hosts may be similar. Subclinical infections and, more frequently, asymptomatic carriage are common in humans, and the very high incidence of infection in 2-year-old thoroughbreds (ca. 95%), although very strongly associated with lower airway inflammation, is frequently subclinical (30). Whether or not there are real differences in the pathologic severity of human and equine pneumococcus infections, it is interesting that Streptococcus equi, the cause of strangles (a severe upper respiratory tract infection in the horse) also lacks a thiol-activated toxin equivalent to streptolysin O (9). Equine S. pneumoniae and S. equi are two pathogenic streptococci that, by comparison to other pathogenic members of the genus, would be expected to produce a thiol-activated toxin but do not. This deficiency poses the question of whether the thiol-activated toxins provide a selective disadvantage in the horse and so have been lost with time.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Rubens López for performing the analysis of autolytic activity and to Paul Pickerill for valuable technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust, the BBSRC and the UK MRC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benson C E, Sweeney C R. Isolation of Streptococcus pneumoniae type 3 from equine species. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;20:1028–1030. doi: 10.1128/jcm.20.6.1028-1030.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blunden A S, Mackintosh M E. The microflora of the lower respiratory tract of the horse: an autopsy study. Br Vet J. 1991;147:238–250. doi: 10.1016/0007-1935(91)90048-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blunden A S, Hannant D, Livesay G, Mumford J A. Susceptibility of ponies to infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae (capsular type 3) Equine Vet J. 1994;26:22–28. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1994.tb04325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burrell M H, Mackintosh M E, Taylor C E D. Isolation of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the respiratory tract of horses. Equine Vet J. 1986;18:183–186. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1986.tb03591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chanter N. Streptococcus pneumoniae and equine disease. Equine Vet J. 1994;26:5–6. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1994.tb04319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denys G A, Carey R B. Identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae with a DNA probe. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2725–2727. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.10.2725-2727.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enright M C, Spratt B G. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology (Reading) 1998;144:3049–3060. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fenoll A, Martinez-Suarez J V, Muñoz R, Casal J, Garcia J L. Identification of atypical strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae by a specific DNA probe. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;9:396–401. doi: 10.1007/BF01979468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flanagan J, Colin N, Timoney J, Mitchell T, Mumford J A, Chanter N. Characterisation of the haemolytic activity of Streptococcus equi. Microb Pathog. 1998;24:211–221. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall L M C, Whiley R A, Duke B, George R C, Efstratiou A. Genetic relatedness within and between serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the United Kingdom: analysis of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and antimicrobial resistance patterns. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:853–859. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.853-859.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofer B F, Steck H, Gerber J, Lohrer J, Nicolet J, Paccaud M F. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Equine Infectious Diseases. 1972. An investigation of the aetiology of viral respiratory disease in a remount depot; pp. 527–545. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Höltje J V, Tomasz A. Purification of the pneumococcal N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase to biochemical homogeneity. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:4199–4207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12a.The Institute for Genomic Research. 1999, copyright date. Sequences. [Online.] http://tgr.org. [8 April 1999, last date accessed.]

- 13.Kehoe M A. Cell wall associated proteins in Gram-positive bacteria. New Compr Biochem. 1994;27:217–261. [Google Scholar]

- 14.King, S. J., and C. G. Dowson. Unpublished data.

- 15.Kumar S K, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA: molecular evolutionary genetic analysis software for microcomputers. CABIOS. 1993;10:189–191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackintosh M E, Grant S T, Burrell M H. Evidence for Streptococcus pneumoniae as a cause of respiratory disease in young thoroughbred horses in training. In: Powell D G, editor. Equine infectious diseases, no. 5: Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky; 1989. pp. 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer J C, Koterba A, Lester G, Purich B L. Bacteremia and pneumonia in a neonatal foal caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae type 3. Equine Vet J. 1992;24:407–410. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1992.tb02866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell T J, Andrew P W. Biological properties of pneumolysin. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:19–26. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell T J, Alexander J E, Morgan P J, Andrew P W. Molecular analysis of virulence factors of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Appl Microbiol. 1997;83:62S–71S. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.83.s1.7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison D A. Streptococcal competence for genetic transformation: regulation by peptide pheromones. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:27–37. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Müller-Graf, C. D. M., A. M. Whatmore, S. J. King, A. P. Pickerill, N. C. Doherty, and C. G. Dowson. Unpublished data.

- 22.Neufeld F, Schnitzler R. Pneumokokken Handbuch der Pathogenen Mikro-organismen. 3rd ed. Berlin, Germany: Gustav Fischer; 1928. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paton J C. The contribution of pneumolysin to the pathogenicity of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:103–106. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)81526-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ronda C, García J L, García E, Sánchez-Puelles J M, López R. Biological role of the pneumococcal amidase. Cloning of the lytA gene in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Eur J Biochem. 1987;164:621–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb11172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rudolph K M, Parkinson A J, Black C M, Mayer L W. Evaluation of polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2661–2666. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2661-2666.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salo P, Ortqvist A, Leinonen M. Diagnosis of bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia by amplification of a pneumolysin gene fragment in serum. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:479–482. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.2.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26a.Selkov, E. Metabolic reconstructions. [Online.] WIT Program, version 2. http://wit.mcs.anl.gov/wit2. [8 April 1999, last date accessed.]

- 27.Virolainen A, Salo P, Jero J, Karma P, Eskola J, Leinonen M. Comparison of PCR assay with bacterial culture for detecting Streptococcus pneumoniae in middle ear fluid of children with acute otitis media. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2667–2670. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2667-2670.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whatmore A M, Barcus V A, Dowson C G. Genetic diversity of the streptococcal competence (com) gene locus. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3144–3154. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.10.3144-3154.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood J L N, Burrell M H, Roberts C A, Chanter N, Shaw Y. Streptococci and Pasteurella spp. associated with disease of the equine lower respiratory tract. Equine Vet J. 1993;25:314–318. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1993.tb02970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wood, J. L. N., J. R. Newton, N. Chanter, J. A. Mumford, H. G. G. Townsend, K. H. Lakhani, S. M. Gower, M. H. Burrell, R. C. Pilsworth, M. Shepherd, R. Hopes, D. Dugdale, B. M. B. Herinckx, J. P. M. Main, H. M. Windsor, and G. D. Windsor. Longitudinal epidemiological study of respiratory disease in race horses: disease definitions, prevalence, and incidence. In U. Wernery, J. F. Wade, J. A. Mumford, and O.-R. Kaarden (ed.), Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Equine Infectious Diseases, in press. R & W Publications, Newmarket, United Kingdom.

- 31.Yother J, Briles D E. Structural properties and evolutionary relationships of PspA, a surface protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae, as revealed by sequence analysis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:601–609. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.601-609.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]