Abstract

The aim of this study was to rapidly review the literature on the prevalence of menstrual disorders in female athletes from different sports modalities. Articles were searched in the Web of Science and PubMed database in May 2022. A total of 1309 records were identified, and 48 studies were included in the final stage. The menstrual disorders described in the included studies were primary (in 33% of included studies) and secondary amenorrhea (in 73% of included studies) and oligomenorrhea (in 69% of included studies). The prevalence of menstrual disorders among the studies ranged from 0 to 61%. When data were pooled according to discipline (mean calculation), the highest prevalence of primary amenorrhea was found in rhythmic gymnastics (25%), soccer (20%) and swimming (19%); for secondary amenorrhea in cycling (56%), triathlon (40%) and rhythmic gymnastics (31%); and oligomenorrhea in boxing (55%), rhythmic gymnastics (44%) and artistic gymnastics (32%). Based on the results of this review, the study supports the literature of the higher prevalence of menstrual disorders in gymnastics and endurance disciplines. However, team sports modalities such as volleyball and soccer also presented a considerable percentage of menstrual disorders compared to the general population. It reinforces the importance of coaches and physicians paying attention to athletes’ menstrual cycle as the occurrence of menstrual disorders can be associated with impairment on some health components.

Keywords: menstrual disorders, oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea, sports training, female athlete, Olympic sports

1. Introduction

For women involved in sports, the incidence of menstrual irregularities has been reported to be higher compared to the general population, especially at the professional level [1]. High physical demands and insufficient recovery, together with long-term inadequate nutritional intake and psychological stress are potential factors that cause an imbalance in the neuroendocrine process related to the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis, the system controlling female reproduction [2]. The malfunction of the HPO axis can trigger changes in luteinizing hormone pulsatility [3] and estrogen deficiency, leading to a variety of menstrual disturbances such as amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea [4,5].

The definitions of primary and secondary amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea can vary in the scientific literature. Primary amenorrhea is usually defined as a failure to reach the first menstrual period—menarche [6], and secondary amenorrhea is defined as the absence of menstruation for 3 or more months in women with previously regular menses or for 6 months in women with previously irregular menses [7,8]. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA) is one of the main causes of secondary amenorrhea and it is characterized by the suppression of the HPO axis [9]. Three types of FHA have been recognized: weight loss-related, stress-related, and exercise-related amenorrhea [9,10], and their long-term consequences include infertility, delayed puberty, deficiency in bone mineral density, or cardiovascular consequences [11,12,13]. Oligomenorrhea is defined as irregular and prolonged menstrual blood flow, greater than 35 days apart or a total of 5 to 7 cycles a year [14,15]. The main causes of oligomenorrhea are dysfunctions of the HPO axis that in long-term can lead to several complications, such as infertility, hirsutism, low bone density, and endometrial or breast cancer [15,16].

These menstrual disorders aforementioned have been considered one of the negative components of the Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-s), introduced recently by the International Olympic Committee, beyond what is known as the female athlete triad [17]. The occurrence of RED-s and menstrual disorders are more likely to emerge in sports that require low weight such as ballet dancing, gymnastics, figure skating and runners [18,19]. Indeed, higher incidences of menstrual disorders in leanness or in aesthetic sports are widely reported; however, the prevalence in other sports disciplines is still not well documented [2]. The main aim of the study was to rapidly review the literature about the prevalence of menstrual disorders in athletes from different sports disciplines. Second, we aimed to describe the most common disorders according to the sports disciplines. Increasing awareness about the percentage of menstrual cycle disorders among the disciplines may facilitate decision-making based on evidence from those who are involved in female athletes’ training (e.g., coaches, physicians).

2. Materials and Methods

The rapid review was proposed as a methodological approach to accelerate the process of the traditional systematic review guidelines. This method helps to produce evidence for stakeholders in a pragmatic shortcut, facilitating the knowledge translation between scientific evidence and practical context, helping the decision-making in health practice [20,21]. In the case of this review, the rapid review approach can help to hasten the knowledge-translation process in order to identify which sports disciplines are more likely to be at risk of menstrual irregularities, providing early diagnosis and intervention to avoid impairment of female reproductive health. The review was performed under the guidelines of the Cochrane Rapid Reviews Guidance [20] together with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses—PRISMA 2020 [22].

2.1. Search and Eligibility Criteria

A search was performed using two databases: PubMed and Web of Science in March 2022 by one researcher (AP). The eligibility criteria included: (1) professional female athletes across different sports disciplines included into the Olympic Games [23] and age categories; (2) retrospective and cross-sectional studies; and (3) a description of the prevalence of menstrual irregularities in athletes. The following search terms with Boolean operators were used: (“menstrual cycle disorders” OR “menstrual cycle abnormalities” OR “menstrual cycle disturbances” OR “menstrual cycle disruption” OR “menstrual cycle irregularity” OR “menstrual cycle absence” OR “amenorrhea” OR “oligomenorrhea” OR “abnormal menstrual cycle bleeding” OR “abnormal uterine bleeding” OR “anovulation” OR “dysmenorrhea” OR “premenstrual syndrome” OR “menstrual delay” OR “delayed menstruation” OR “heavy menstrual bleeding” OR “female athlete triad” OR “menorrhagia” OR “excessive uterine bleeding”) AND (“alpine skiing” OR “aquatics” OR “archery” OR “artistic gymnastics” OR “artistic swimming” OR “athletics” OR “badminton” OR “baseball” OR “basketball” OR “beach volleyball” OR “boxing” OR “biathlon” OR “bobsleighing” OR “canoe” OR “cross-country skiing” OR “curling” OR “cycling” OR “diving” OR “equestrian” OR “fencing” OR “figure skating” OR “football” OR “freestyle skiing” OR “golf” OR “gymnastics” OR “handball” OR “hockey” OR “horse riding” OR “ice hockey” OR “judo” OR “karate” OR “kayak” OR “luge” OR “Nordic combined” OR “marathon swimming” OR “mountain bike” OR “pentathlon” OR “rhythmic gymnastics” OR “rugby” OR “running” OR “rowing” OR “sailing” OR “shooting” OR “short track” OR “skateboarding” OR “skeleton” OR “ski jumping” OR “snowboarding” OR “sport climbing” OR “soccer” OR “speed skating” OR “surfing” OR “swimming” OR “table tennis” OR “taekwondo” OR “tennis” OR “track and field” OR “trampoline” OR “triathlon” OR “volleyball” OR “water polo” OR “wrestling” OR “weightlifting” OR “3 × 3 basketball” OR “softball” OR “BMX racing” OR “BMX freestyle” OR “road cycling” OR “track cycling”). It was established that articles published from the year of 2000 until May of 2022 were included in this study. Exclusion criteria included articles with recreational athletes, non-English language, systematic reviews, magazine articles and articles with no full-text available.

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

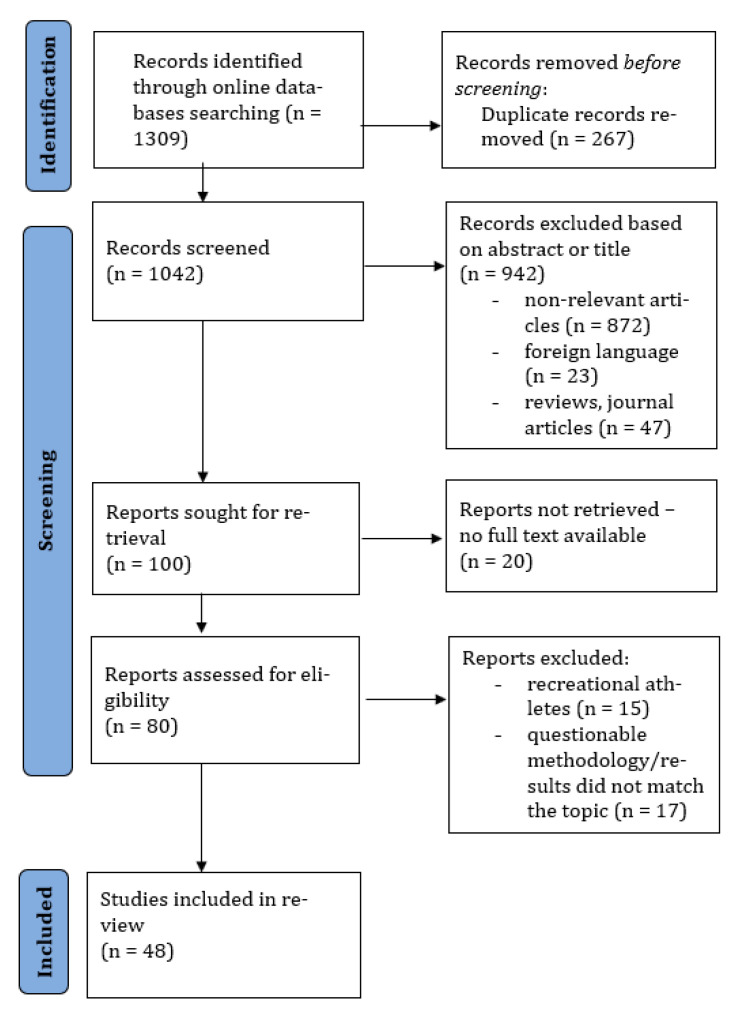

After the search, articles were imported into the Rayyan systematic review software [24] by one researcher (AP), and duplicate, reviews and non-English language articles were excluded. Title and abstract were scanned by one researcher (AP) and the excluded articles were verified by a second researcher (ACP). Any disagreement between reviewers was consulted by a third reviewer (MG). Full text and data extraction were performed by two independent reviewers (AP, MG). To extract the data, a form was developed by the researchers with information about the sample characteristics, sports discipline, age of menarche, methods, monitored period, menstrual disorders’ prevalence (primary amenorrhea, secondary amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, other) and the definition of the menstrual disorder. The process is summarized in the study selection flow chart (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart diagram of the study process.

2.3. Studies Methodological Quality

The Adjusted Downs and Black Quality Assessment Checklist [25] was used to assess the quality of the studies. The original protocol consists of 27 “yes” or “no” questions divided into five sections: quality of reporting, external validity, internal validity bias, confounding and selection bias, and power of the study [25], with a binary score for each question: 0 = no/unable to determine and 1 = yes. For the present review, it was considered 13 items relevant (Supplementary Materials Table S1). The rating system was adjusted, and the final score was converted to percentages and classified as follows: <45.4% “poor” methodological quality; 45.5–61.0% “fair” methodological quality”; and >61.0% “good” methodological quality [26]. The quality assessment was not used to exclude any study. The same approach was applied in previous review studies, e.g., [26,27,28].

2.4. Mean Prevalence Separated by Sports Discipline

To describe the prevalence of menstrual irregularities (primary amenorrhea, secondary amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea) considering each sport discipline, an arithmetic mean, minimum and maximum prevalence (if more than one study was available) were calculated, pooling together the values of all studies that evaluated the same discipline.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

After entering the keywords into the search databases PubMed and Web of Science, 1309 studies were found. Duplicate articles were removed (n = 267), and 70 were excluded for presenting a review method or were in a foreign language. The title and abstract were screened in 972 articles, and 872 were excluded. In the last stage, 20 articles were excluded due to no full text being available, 15 articles were excluded to assess recreational athletes and 17 were excluded because the outcomes did not match with the topic. A total of 48 articles were included in the last stage of the review (Figure 1).

3.2. Description of Included Studies

The methodological quality of the studies included is summarized in Supplementary Materials (Tables S1 and S2). Most of the studies (n = 42) presented a score higher than 61.0%, which classifies them as good quality studies (ranging from 69 to 92%). Six studies were classified as fair quality. The most common methodological deficits in the articles were the lack of representativeness of the source population, reliability of outcome measures, and recruitment of participants over the same period. The disciplines were grouped by categories according to their characteristics [29]: team sports (basketball, field hockey, ice hockey, soccer, softball, synchronized swimming, volleyball, water polo), cyclic sports (running, rowing, swimming, cycling, triathlon, track-and-field), individual sports (boxing, fencing, figure skating, gymnastics, tennis) and winter sports (skiing, biathlon, bobsleigh, luge, skeleton, snowboarding, speed skating). In the case of a study that assessed more than one discipline (e.g., runners and soccer players), each discipline was counted individually.

The majority of the studies focused on runners (n = 21), gymnasts (n = 14) and track-and-field (n = 6) athletes. Included participants varied from elite athletes (e.g., [30,31,32]) to collegiate athletes (e.g., [33,34]). Menstrual disorders investigated in the studies were primary (in 33% of included studies) and secondary amenorrhea (in 73% of included studies), oligomenorrhea (in 69% of included studies) and other menstrual irregularities (in 23% of included studies). The prevalence of menstrual disorders ranges from non-disorder (0%) as observed in water polo players [33] to a maximum percentage of 53.8% of primary, 30.8% of secondary amenorrhea and 61% of oligomenorrhea observed in rhythmic gymnastics athletes [31,35,36]. The menstrual disorder reported in the studies examined a retrospective period varying from the last 3, 6 or 12 months, 5 years or one year after menarche (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sports disciplines and the number of studies assessing the prevalence of menstrual cycle disorders.

| Team Sports | n | Cyclic Sports | n | Other Individual Sports | n | Winter and Outdoor Sports | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basketball | 2 | Cross-country running | 6 | Boxing | 1 | Alpine skiing | 1 |

| Field hockey | 2 | Middle/long-distance running | 10 | Fencing | 1 | Biathlon | 1 |

| Ice hockey | 1 | Rowing | 4 | Figure skating | 1 | Bobsleigh | 1 |

| Soccer | 3 | Short distance running | 2 | Gymnastics * | 2 | Luge | 1 |

| Softball | 2 | Swimming | 4 | Artistic gymnastics | 2 | Skeleton | 1 |

| Synchronized swimming | 2 | Track-and-field | 6 | Rhythmic gymnastics | 10 | Snowboarding | 1 |

| Volleyball | 2 | Triathlon | 3 | Tennis | 2 | Aerial skiing | 1 |

| Water polo | 1 | Cycling | 2 | Speed skating | 1 |

3.2.1. Team Sports

Fifteen studies reported the prevalence of menstrual disorders in team sports disciplines (Table 2). Menstrual disorders were reported based on the last 12 months [33,34,37], 6 months [38], or in the post-menarche period [39,40]. The highest prevalence of primary amenorrhea (20%) was observed in soccer players [33], secondary amenorrhea (30%) in volleyball players [39], and oligomenorrhea (20%) in soccer players [33]. Up to 71.5% of ice hockey players experienced minor menstrual dysfunction [37].

Table 2.

Sample characteristics, menstrual disorders measurement and prevalence in team sports.

| Study (Year) | Sport | Sample (n) | Mean Age ± SD (Years) | Methods | Monitored Period |

Age of Menarche (Years) | Primary Amenorrhea (n, %) |

Secondary Amenorrhea (n, %) |

Oligomenorrhea (n, %) |

Other (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dusek (2001) [39] | basketball | 18 | 18.8 ± 1.1 | questionnaire | post-menarche | 12.7 ± 1.1 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.6%) | NA | painful menstruation 18 out of 67 athletes (26.9%) |

| Tenforde et al. (2017) [33] | basketball | 9 | 20 ± 1.3 | PPEs | 12 months | NA | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | NA |

| Tenforde et al. (2017) [33] | field hockey | 21 | 20 ± 1.3 | PPEs | 12 months | NA | 2 (9.55%) | 3 (14.3%) | 4 (19.1%) | NA |

| Mudd, Fornetti and Pivarnik (2007) [34] | field hockey | 10 | 19.8 ± 1.2 | questionnaire | 12 months | 12.9 ± 1.6 | NA | 1 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | NA |

| Egan et al. (2003) [37] | ice hockey | 28 | 23.5 ± 4.8 | questionnaire | 12 months | 13.3 ± 1.3 | 4 (15.0%) | NA | 2 (7.1%) | 71.5% experienced minor menstrual dysfunction |

| Prather et al. (2016) [40] | soccer | 145 | 16.4 ± 4 | questionnaire | 1 year post-menarche |

13.0 ± 1.0 | 28 (19.3%) * | NA | NA | |

| Tenforde et al. (2017) [33] | soccer | 5 | 20 ± 1.3 | PPEs | 12 months | NA | 1 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | NA |

| Mudd, Fornetti and Pivarnik (2007) [34] | soccer | 10 | 19.8 ± 0.9 | questionnaire | 12 months | 12.9 ± 1.4 | NA | 1 (10.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | NA |

| Tenforde et al. (2017) [33] | softball | 19 | 20 ± 1.3 | PPEs | 12 months | NA | 3 (15.75%) | 2 (10.5%) | 2 (10.5%) | NA |

| Mudd, Fornetti and Pivarnik (2007) [34] | softball | 14 | 20.1 ± 1.1 | questionnaire | 12 months | 13.5 ± 2.5 | NA | 1 (7.1%) | 1 (7.1%) | NA |

| Ramsay and Wolman (2001) [38] |

synchronized swimming | 23 | 17.1 ± 1.9 | questionnaire | 6 months | NA | NA | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (13.0%) | NA |

| Tenforde et al. (2017) [33] | synchronized swimming | 11 | 20 ± 1.3 | PPEs | 12 months | NA | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (9.1%) | 2 (18.2%) | NA |

| Dusek (2001) [39] | volleyball | 10 | 17.4 ± 1.4 | questionnaire | post-menarche | 13.3 ± 1.5 | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (30.0%) | NA | NA |

| Tenforde et al. (2017) [33] | volleyball | 9 | 20 ± 1.3 | PPEs | 12 months | NA | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | NA |

| Tenforde et al. (2017) [33] | water polo | 16 | 20 ± 1.3 | PPEs | 12 months | NA | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | NA |

PPEs: Preparticipation Physical Examinations; * reported prevalence of primary and/or secondary amenorrhea.

3.2.2. Cyclic Sports

Third-sixty investigations described the prevalence of menstrual disorders in cyclic sports (Table 3). Menstrual disorders were reported based on the last 5 years [41], 12 months (e.g., [33,34,42]), 6 months [43] or in post-menarche [39,44,45]. In cyclic sports, the highest prevalence of primary amenorrhea (20%) was observed in middle/long distance runners [39], secondary amenorrhea (55% and 55.6%) in middle/long distance runners and cyclists, respectively [39,46]. The highest prevalence of oligomenorrhea (47.5%) was observed in endurance athletes [47]. Menstrual cycle (MC) irregularity was observed in 83.3% of lightweight rowers [45].

Table 3.

Sample characteristics, menstrual disorders measurement and prevalence in cyclic sports.

| Study (Year) | Sport | Sample (n) | Mean Age ± SD (Years) | Methods | Monitored Period | Age of Menarche (Years) |

Primary Amenorrhea (n, %) | Secondary Amenorrhea (n, %) | Oligomenorrhea (n, %) | Other (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thompson (2007) [48] | cross-country running | 300 | 19.64 ± 1.56 | questionnaire | post menarche period |

13.46 ± 1.65 | NA | 16 (5.3%) | 53 (17.7%) | NA |

| Jesus et al. (2021) [42] | cross-country running | 83 | 21.8 ± 4.0 | LEAF-Q | 12 months | NA | NA | 18 (22.0%) | 23 (28.0%) | NA |

| Barrack, Rauch, and Nichols (2008) [49] | cross-country running | 93 | 16.1 ± 0.1 | questionnaire. preparticipation medical history form | 12 months | 12.8 ± 0.1 | 3 (3.2%) | 16 (17.2%) | 5 (5.4%) | NA |

| Barrack et al. (2010) [50] | cross-country running | 39 | 15.7 ± 0.2 | questionnaire | 12 months | 13.9 | 3 (7.7%) | 9 (23.1%) | 9 (23.1%) | NA |

| Mudd, Fornetti and Pivarnik (2007) [34] |

cross-country and track runners (800 m or longer) | 25 | 20.4 ± 1.3 | questionnaire | 12 months | 13.8 ± 2.1 | NA | 4 (16.0%) | 7 (28.0%) | MC irregularity: 25 (25.2%) |

| Tenforde et al. (2017) [33] | cross-country running | 47 | 20 ± 1.3 | PPEs | 12 months | NA | 9 (19.17%) | 10 (21.3%) | 8 (17.0%) | NA |

| Hutson et al. (2021) [51] | middle/long-distance running |

183 | 18–40 | questionnaire | 12 months | NA | NA | 1 (0.5%) | 37 (20.2%) | NA |

| Muia et al. (2015) [52] | middle/long-distance running |

56 | 16 | questionnaire | 12 months | 14 | 24 (13.1%) | 36 (19.7%) | NA | NA |

| Beckvid Henriksson, Schnell, and Lindén Hirschberg (2000) [53] | middle/long-distance running |

93 | 25.8 ± 1.3 | questionnaire | 12 months | 14.2 ± 0.5 | 1 (1.1%) | 7 (8.0%) | 16 (17.0%) | NA |

| Pollock et al. (2010) [32] | middle/long-distance running |

36 | 22.9 ± 6.0 | questionnaire | 12 months | 13.9 ± 1.5 | NA | 9 (25.0%) | 14 (38.0%) | NA |

| Burrows et al. (2003) [54] | middle/long-distance running |

52 | 31.0 ± 5.0 | questionnaire | 12 months | 14 ± 2 | NA | 1 (2.0%) | 11 (21.2%) | NA |

| Cobb et al. (2003) [55] | middle/long-distance running |

91 | 21.8 ± 0.5 | questionnaire | 12 months | 13.8 ± 0.2 | NA | 9 (10.0%) | 24 (26.0%) | NA |

| Dusek (2001) [39] | middle/long-distance running |

20 | 17.9 ± 2.1 | questionnaire | post-menarche | 13.5 ± 1.7 | 4 (20.0%) | 11 (55.0%) | NA | NA |

| Tenforde et al. (2015) [56] | middle/long-distance running |

91 | 16.9 ± 1.3 | PPEs | 12 months | 12.9 ± 1.5 | 39 (43.0%) * | NA | NA | |

| Rauh, Barrack and Nichols (2014) [57] | middle/long-distance running |

89 | 15.5 ± 1.3 | questionnaire | 12 months | 12.3 ± 1.1 | NA | NA | NA | MC irregularity: 19 (21.3%) |

| Gibson et al. (2000) [44] | middle/long-distance running |

51 | 16–35 | questionnaire | Post-menarche period | NA | NA | NA | NA | MC irregularity: 33 (64.7%) |

| Walsh, Crowell and Merenstein (2020) [58] |

lightweight rowers | 78 | 20 ± 2.8 | questionnaire | post-menarche period | NA | NA | NA | NA | MC irregularity: 14 (35%) |

| openweight rowers | 80 | 21.5 ± 7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | MC irregularity: 8 (22.9%). |

|||

| Dimitriou et al. (2014) [45] | lightweight rowers | 12 | 26.6 ± 2.0 | questionnaire | post-menarche period | 13.4 ± 1.1 | NA | NA | NA | MC irregularity: 10 (83.3%) |

| Tenforde et al. (2017) [33] | rowing/crew | 30 | 20 ± 1.3 | PPEs | 12 months | NA | 2 (6.6%) | 1 (3.3%) | 5 (16.7%) | NA |

| Mudd, Fornetti and Pivarnik (2007) [34] |

rowing/crew | 15 | 20.5 ± 2.1 | questionnaire | 12 months | 13.2 ± 2.4 | NA | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | NA |

| Mudd, Fornetti and Pivarnik (2007) [34] |

short-distance running | 8 | 20.1 ± 1.3 | questionnaire | 12 months | 13.4 ± 1.9 | NA | 2 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | NA |

| Dusek (2001) [39] | short-distance running | 14 | 17.9 ± 2.1 | questionnaire | post-menarche | 13.1 ± 0.8 | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (21.4%) | NA | NA |

| Coste et al. (2011) [59] | swimming | 18 | 15.2 ± 1.1 | questionnaire | post-menarche | 12.5 ± 1.0 | NA | 2 (11.1%) | 7 (38.9%) | NA |

| Schtscherby et al. (2009) [43] | swimming | 78 | 16.7 ± 1.22 | questionnaire | 6 months | 12.38 ± 0.2 | NA | 0 (0.0%) | 15 (19.2%) | NA |

| Mudd, Fornetti and Pivarnik (2007) [34] |

swimming/diving | 9 | 20.4 ± 1.1 | questionnaire | 12 months | 13.5 ± 1.5 | NA | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (22.2%) | NA |

| Tenforde et al. (2017) [33] | swimming/diving | 21 | 20 ± 1.3 | PPEs | 12 months | NA | 4 (19.0%) | 5 (23.8%) | 2 (9.5%) | NA |

| Tsukahara et al. (2021) [60] | track-and-field | 91 | 18.10 ± 0.37 | interview | 12 months | 13.4 ± 1.3 | NA | 6 (6.6%) | 33 (36.3%) | NA |

| Sygo et al. (2018) [61] | track-and-field | 13 | 21 ± 3 | LEAFNAQ | 12 months | NA | NA | NA | NA | MC irregularity: 3 (23%) |

| Robbeson, Havemann-Nel and Wright (2013) [62] | track-and-field | 16 | 19.0 | questionnaire | 12 months | 14 | NA | 3 (18.75%) | 1 (6.25%) | NA |

| Nattiv et al. (2013) [41] | track-and-field | 22 | 20.2 ± 0.3 | questionnaire | 5-year period |

NA | NA | NA | NA | MC irregularity: 5 (23%) |

| Tenforde et al. (2017) [33] | track-and-field | 4 | 20 ± 1.3 | PPEs | 12 months | NA | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | NA |

| Feldmann et al. (2011) [63] | track-and-field | 103 | 16 ± 0.97 | questionnaire | 12 months | NA | NA | 16 (16.7%) | 16 (16.7%) | NA |

| Hoch, Stavrakos and Schimke (2007) [64] |

triathletes | 15 | 35 ± 6 | questionnaire | post-menarche | NA | NA | 6 (40.0%) | NA | NA |

| Duckham et al. (2015) [47] | endurance athletes (running, triathlon) |

61 | 25.3 ± 7.3 | questionnaire | 12 months | 14.0 ± 0.2 | NA | NA | 29 (47.5%) | NA |

| Duckham et al. (2013) [65] | endurance athletes (runners, triathletes) |

68 | 25.4 | questionnaire | 12 months | 14.2 | NA | NA | 24 (35.0%) | NA |

| Raymond-Barker, Petroczi and Quested (2007) [66] |

endurance athletes (runners, cyclists), gymnasts |

48 | 37 ± 7.95 | questionnaire | post-menarche period | NA | NA | 14 (23.7%) | NA | NA |

| Haakonssen et al. (2014) [46] | cyclists | 37 | 18–36 | Female Cyclist Weight Management Questionnaire (FCWM) |

12 months | NA | NA | 10/18 (55.6%) | 1 (5.6%) | NA |

PPEs: Preparticipation Physical Examinations; * reported prevalence of primary and/or secondary amenorrhea.

3.2.3. Other Individual Sports

Nineteen investigations described menstrual disorders in individual sports (Table 4). Most of the studies focused on rhythmic gymnastics [30,31,35,36,67,68,69,70,71,72], artistic gymnastics [72,73] and gymnastics [33,34]. Menstrual disorders were reported based on the last 12 months [33,34,35,36,37,67,68,71,74], the last 3 months [30], one year after menarche [75], or in the post-menarche period [70]. The highest prevalence of primary amenorrhea (53.8%), secondary amenorrhea (50%) and oligomenorrhea (61%) was observed in rhythmic gymnastics [31,35,36]. The highest prevalence of MC irregularities (55%) and hypermenorrhea (62.22%) was also observed in rhythmic gymnastics [67,71].

Table 4.

Sample characteristics, menstrual disorders measurement and prevalence in other individual sports.

| Study (Year) | Sport | Sample (n) | Mean Age ± SD (Years) | Methods | Monitored Period |

Age of Menarche (Years) |

Primary Amenorrhea (n, %) | Secondary Amenorrhea (n, %) | Oligomenorrhea (n, %) | Other (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trutschnigg et al. (2008) [74] | boxing | 11 | 26.7 ± 6.8 | modified ACSM medical health questionnaire |

12 months | 12.8 ± 1.9 | NA | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (54.6%) | NA |

| Tenforde et al. (2017) [33] | fencing | 5 | 20 ± 1.3 | PPEs | 12 months | NA | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | NA |

| Egan et al. (2003) [37] | figure skating |

37 | 17.5 ± 3.4 | questionnaire | 12 months | NA | NA | 3 (10.56%) | 8 (28.15%) | NA |

| Tenforde et al. (2017) [33] | gymnastics | 16 | 20 ± 1.3 | PPEs | 12 months | NA | 6 (37.6) | 3 (18.8%) | 3 (18.8%) | NA |

| Mudd, Fornetti and Pivarnik (2007) [34] |

gymnastics | 8 | 19.7 ± 0.9 | questionnaire | 12 months | 14.3 ± 1.3 | NA | 1 (12.5%) | 2 (25.0%) | NA |

| Corujeira et al. (2012) [73] | artistic gymnasts | 27 | 14.08 | questionnaire | NA | 13 | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (14.0%) | 8 (29.0%) | NA |

| Helge and Kanstrup (2002) [72] | artistic gymnasts | 6 | 17.9 ± 1.5 | questionnaire | NA | 15.3 ± 1.8 | 1 (16.65%) | 2 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | NA |

| Meng et al. (2020) [35] | rhythmic gymnastics | 52 | 20 ± 3.0 | LEAF-Q | 12 months | NA | 28 (53.8%) | 16 (30.8%) | 7 (13.5%) | NA |

| Roupas et al. (2014) [68] | rhythmic gymnastics | 77 | 18.3 ± 2.6 | questionnaire | 12 months | NA | 18 (23.4%) | NA | 35 (45.5%) | NA |

| Maїmoun et al. (2013) [67] | rhythmic gymnastics | 82 | 18.3 ± 2.5 | questionnaire | 12 months | 15.6 ± 1.6 | 17 (20.7%) | NA | NA | MC irregularity: 36 (55%) |

| Salbach et al. (2007) [69] | rhythmic gymnastics | 50 | 14.8 ± 2.1 | questionnaire | NA | NA | 7 (14.0%) * | NA | NA | |

| Muñoz et al. (2004) [70] | rhythmic gymnastics | 9 | 16.2 ± 2.0 | individual medical examination |

post-menarche period | 15 ± 1 | NA | NA | 4 (45.0%) | NA |

| Czajkowska et al. (2019) [71] | rhythmic gymnastics | 45 | 16.28 ± 0.84 | questionnaire | 12 months | 13.02 ± 1.03 | NA | 8 (47.06%) | 9 (52.94%) | hypermenorrhoea 28 (62.22%) |

| Klinkowski et al. (2008) [30] | rhythmic gymnastics | 51 | 15.2 ± 1.8 | questionnaire | 3 months | NA | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (7.8%) | NA | NA |

| Klentrou and Plyley (2003) [31] | rhythmic gymnastics | 23 | 14.7 ± 0.4 | survey | post-menarche period | 13.6 ± 1.2 | NA | 4 (17.4%) | 14 (61.0%) | NA |

| Di Cagno et al. (2012) [36] | rhythmic gymnastics | 46 | 17.4 ± 3.0 | menstrual history questionnaire (MHQ) |

12 months | 15.0 ± 1.5 | NA | 23 (50.0%) | NA | NA |

| Helge and Kanstrup (2002) [72] | rhythmic gymnastics | 5 | 18.3 ± 1.9 | questionnaire | NA | 13.3 ± 1.8 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | NA |

| Tenforde et al. (2017) [33] | tennis | 7 | 20 ± 1.3 | PPEs | 12 months | NA | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 3 (42.9%) | NA |

| Coelho et al. (2013) [75] | tennis | 24 | 14.77 ± 2.16 | questionnaire | 1 year after menarche | 12.05 ± 1.25 | NA | 2 (9.1%) | 1 (4.5%) | MC irregularity: 8 (33.3%) |

PPEs: Preparticipation Physical Examinations; * reported prevalence of primary and/or secondary amenorrhea.

3.2.4. Winter and Outdoor Sports

Only one study focused on the prevalence of menstrual disorders in winter sports during the previous 12 months. This study did report the prevalence of amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea in different sports modalities. Secondary amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea were prevalent in 22.5% and 30% of winter sports athletes [76], respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

Sample characteristics, menstrual disorders measurement and prevalence in winter and outdoor sports.

| Study (Year) | Sport | Sample (n) | Mean Age ± SD (Years) | Methods | Monitored Period | Age of Menarche | Primary Amenorrhea | Secondary Amenorrhea | Oligomenorrhea (n, %) | Other (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meyer et al. (2004) [76] | long track speed skating, freestyle skiing, aerials, snowboarding, alpine skiing, biathlon, bobsleigh, skeleton, luge |

n = 40 | 26.1 ± 5.7 | questionnaire | 12 months | 13.4 ± 1.5 | NA | n = 9 (22.5%) | n = 12 (30.0%) | NA |

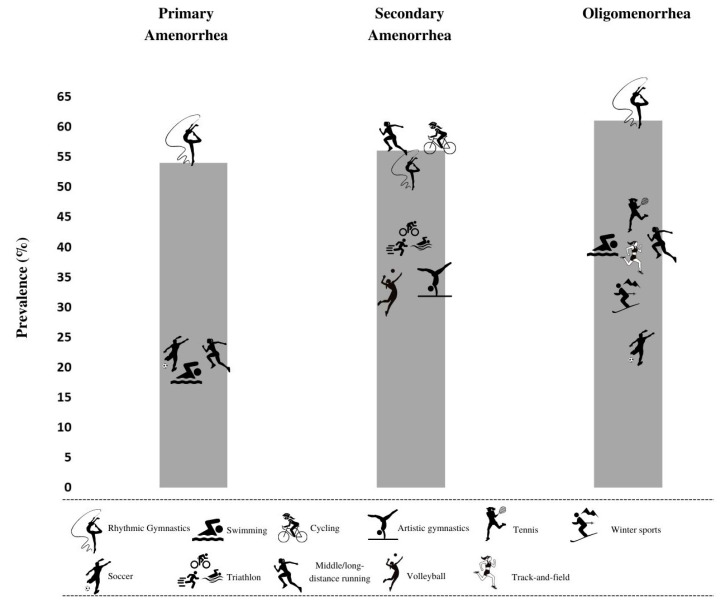

In Table 6 the mean prevalence of menstrual cycle disorders and the minimum and maximum prevalence when more than one study was available in analyzed sports disciplines is summarized. These pooled data show that the highest mean prevalence of primary amenorrhea can be found in rhythmic gymnastics (25%), soccer (20%) and swimming (19%). The highest mean prevalence of secondary amenorrhea was observed in cycling (56%), triathlon (40%) and rhythmic gymnastics (31%). The highest mean prevalence of oligomenorrhea was observed in boxing (55%), rhythmic gymnastics (44%) and artistic gymnastics (32%). No menstrual disorders were found among athletes competing in water polo. Figure 2 shows the highest prevalence of primary, secondary amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea considering the individual results from the articles included in the study.

Table 6.

Sports disciplines and the mean (min, max) prevalence (%) of menstrual cycle disorders.

| Primary Amenorrhea |

Secondary Amenorrhea |

Oligomenorrhea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Team Sports | |||

| Basketball | 0.00% | 2.80% (0.00, 5.60) | 0.00% |

| Field hockey | 9.55% | 12.15% (10.00, 14.30) | 9.55% (0.00, 19.10) |

| Ice hockey | 15.00% | NA | 7.10% |

| Soccer | 20.00% | 5.00% (0.00, 10.00) | 15.00% (10.00, 20.00) |

| Softball | 15.75% | 8.80% (7.10, 10.50) | 8.80% (7.10, 10.50) |

| Synchronized swimming | 9.10% | 4.55% (0.00, 9.1) | 15.60% (13.00, 18.20) |

| Volleyball | 0.00% | 20.55% (11.10, 30.00) | 11.10% |

| Water polo | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Cyclic sports | |||

| Cross-country running | 10.02% (3.20, 19.17) | 17.48% (5.30, 23.10) | 19.87% (5.40, 28.00) |

| Middle/long-distance running | 11.40% (1.10, 20.00) | 17.17% (0.50, 55.00) | 24.48% (17.00, 38.00) |

| Rowing | 6.60% | 1.65% (0.00, 3.30) | 15.00% (13.30, 16.70) |

| Short distance running | 0.00% | 23.20% (21.4, 25.00) | 0.00% |

| Swimming | 19.00% | 8.73% (0.00, 23.80) | 22.45% (9.50, 38.90) |

| Track-and-field | 0.00% | 10.51% (0.00, 18.75) | 21.04% (6.25, 36.30) |

| Triathlon | NA | 40.00% | NA |

| Cycling | NA | 55.60% | 5.60% |

| Other Individual Sports | |||

| Boxing | NA | 0.00% | 54.60% |

| Fencing | 0.00% | 0.00% | 20.00% |

| Figure skating | NA | 10.56% | 28.15% |

| Artistic gymnastics | 8.33% (0.00, 16.65) | 23.67% (14.00, 33.33) | 31.17% (29.00, 33.33) |

| Rhythmic gymnastics | 24.48% (0.00, 53.80) | 30.61% (7.80, 50.00) | 43.59% (13.50, 61.10) |

| Tennis | 0.00% | 11.70% (9.10, 14.30) | 23.70% (4.50, 42.90) |

| Winter sports | NA | 22.50% | 30.00% |

Figure 2.

Sports disciplines with the highest prevalence of primary, secondary amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea.

4. Discussion

The major findings of the present rapid review were that rhythmic gymnastics is a discipline in which the athletes suffer a major risk to present menstrual disorders, including a percentage of 53.8% for primary amenorrhea [35], 30.8% for secondary amenorrhea [36] and 61% for oligomenorrhea [31]. Moreover, cyclic and individual sports disciplines also presented high frequencies of menstrual disorders, especially middle/long distance running (55% for secondary amenorrhea [39]), cycling (55.6% for secondary amenorrhea [46]), triathlon (40% for secondary amenorrhea [64]), boxing (54.6% for oligomenorrhea [74]) and tennis (42.9% for oligomenorrhea [33]). In team sports, a higher percentage of menstrual disorders was found in volleyball athletes, showing a prevalence of secondary amenorrhea of 30% amongst the athletes [39]). Lastly, secondary amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea were menstrual disorders with major prevalence in the sports disciplines.

4.1. Primary Amenorrhea

As described previously, primary amenorrhea can be known as a failure to reach the first menstrual period. In the general population, the occurrence of this event is less than 1% [6]; nonetheless, in the athletes’ population, it was possible to notice that this prevalence is considerably higher, reaching 53.8% as demonstrated in rhythmic gymnastics athletes [35]. Besides the higher prevalence in rhythmic gymnastics, primary amenorrhea was also frequent in soccer players (20%) [33] and in swimmers (19%) [33].

A delay in menarche in athletes compared to controls has been demonstrated in the scientific literature [39,77,78]. Not just elite but novice athletes also showed a significant delay of around half a year [78]. A possible explanation could be related to the training intensity combined with inadequate recovery. It can result in an energy deficit leading to suppression of the endocrine function and hypoestrogenemia, causing the delay of age of menarche [79,80,81].

Previous studies show that in elite rhythmic gymnasts, intensive training and negative energy balance delays the pubertal onset by affecting the HPO axis and decreasing the estrogen production; thus, the pre-pubertal stage is prolonged and the pubertal development occurs in later age [80,81]. On the other hand, it has been described that swimmers present a greater percentage of subcutaneous fat compared to other athletes as it reflects the adjustment to the sport-specific requirements. As so, the delayed puberty in swimmers has been associated with mild hyperandrogenism, an androgen disorder characterized by hirsutism, acne or alopecia, and mild insulin resistance presenting a metabolic and cardiovascular risk [82], as reported somewhere [80].

4.2. Secondary Amenorrhea

Secondary amenorrhea was one of the menstrual disorders that presented the highest prevalence in sports disciplines such as cycling (56% [46]), triathlon (40% [64]) and rhythmic gymnastics (mean prevalence of 31%). The prevalence reported in the studies can be considered elevated compared to the general population in which the estimated prevalence is around 5–12.2% [83,84].

Conceptualized as the absence of menstruation for three or more months in women with previous regular menses, or for 6 months in women with previously irregular menses [7,8], secondary amenorrhea in athletes is likely related to the deficit of energy as suggested in the studies that evaluated the cyclists, triathletes and rhythmic gymnasts [36,46,64]. Sixty percent of the triathletes were found to be in a caloric deficit [64]. Similarly, in the study with elite cyclists, an increased risk of energy deficiency was reported, as their current body weight was not considered ideal for performance in races stressing out the lean body image [46]. Similarly, in rhythmic gymnastics, the lean-sport discipline, intensive training and the pressure for a lean body can result in low body weight and diet restrictions and consequently an inadequate energy availability [36].

Athletes with secondary amenorrhea also can acquire a poor or reduced bone mineral density and a high incidence of bone fractures [85] as the consequence of hypoestrogenemia and chronically low energy availability [2]. In the long-term, hypoestrogenemia is associated with cardiovascular risk, increasing the risk of atherosclerosis and bone loss [80].

4.3. Oligomenorrhea

Oligomenorrhea corresponds to prolonged menstrual periods (e.g., 35 days or more) or irregular cycles (e.g., 5 to 7 cycles per year) [14,15]. According to previous studies, the prevalence of oligomenorrhea in the general population ranges from 6–15.3% [15,16,86,87]. In our review, the highest mean prevalence of oligomenorrhea was observed in boxing (55%), rhythmic gymnastics (44%) and artistic gymnastics (32%). Energy imbalance is again highlighted as the main reason for the presence of oligomenorrhea i The authors speculate that the lower body fat mass and a great energy expenditure in training could generate a lower energy availability triggering the occurrence of oligomenorrhea amongst the athletes from boxing and gymnastics disciplines [36,73,74]. Non-pharmacological treatment focusing on the resumption of menses should be prioritized in athletes, as the menses and normal estrogen status are of great importance for bone health [88].

Taken together, the menstrual disorders mentioned above presented a great influence on low energy availability, as reported in the studies included. Therefore, beyond the prevalence of menstrual disorders in sports disciplines, coaches, trainers and physicians should also be aware of the concept of low energy availability. Dietary and training interventions in female athletes engaged not only in aesthetic disciplines such as rhythmic gymnastics, but also in cycling, winter sports or team sports disciplines (e.g., [33,39,40,76]) are vital.

4.4. Methodological Aspects

Additional to the outcomes from the prevalence of menstrual disorders, this review also shows that the definition of menstrual disorders and the methods of evaluation varied among the studies. There is a need for clear guidelines on how to design studies about the prevalence and how to report the outcomes as mentioned in a previous prevalence review [89].

The menstrual disorders evaluated were conditioned to the methodology chosen by each study. A retrospective report ranged from the last 5 years [41], 12 months (e.g., [33,34,42]), 6 months (e.g., [43]), 3 months [30], one year after menarche [75], or in post-menarche (e.g., [39,44,45]). Similarly, different definitions of menstrual disorders were used amongst the studies. In some, the definition of primary amenorrhea was the non-appearance of menarche up to 15 years of age (e.g., [37,40,50]) and for others the non-appearance up to 16 years of age (e.g., [33,39,43]). The definition of secondary amenorrhea differed from not having a menstrual period for 6 months [48], the absence of three consecutive menstrual cycles [39,50], or having 0 to 3 periods per year [34,44]. The definition of oligomenorrhea included having 4 to 9 periods per year [34], having 6 to 9 periods per year [33], or an interval between periods of more than 35 days and less than 90 days [35,49] (see Supplementary Materials Table S3).

The comparison between different sports disciplines using the same menstrual disorder concept and study methodology was reported by three studies [33,34,39]. In the study of Dusek [39], a highest prevalence of primary amenorrhea and secondary amenorrhea were observed in long-distance runners (20% and 55%, respectively) compared to short distance runners, basketball and volleyball players. Mudd et al. [34] observed the highest prevalence of secondary amenorrhea in short distance runners (25%) and oligomenorrhea in long-distance runners (28%) compared to gymnasts, field hockey players, soccer players, rowers and swimmers. Tenforde et al. [33] reported the highest prevalence of primary amenorrhea in gymnasts (37.6%), secondary amenorrhea in swimmers (23.8%) and oligomenorrhea in tennis players (42%) compared to basketball players, cross-country runners, rowers, soccer players, field-hockey players, fencers, volleyball and water polo players. Further research should monitor the occurrence of menstrual cycle disorders of athletes from different sports disciplines in association with their energy availability to provide a more detailed insight into this topic.

4.5. Limitations of the Study

The main limitation related to the rapid review is the use of two databases to perform the search, so some studies could be missing. Outcomes from only one sport discipline was used, for example in the winter sports, boxing, fencing, figure skating, water polo, or ice hockey, which should be taken into consideration on generalization on the results from these sport disciplines. Differences in sample sizes, measurement methodology, menstrual disorders definition and monitored period, as well as including studies with fair quality requires caution when interpretating the results of this review.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the prevalence of menstrual disorders amongst the athletes ranged from non-disorder (0%) to a maximum percentage of 61%. The systematically summarized studies support the notion of a higher prevalence of menstrual disorders in sports as gymnastics and endurance disciplines. However, team-sports modalities such as volleyball and soccer also presented a considerable percentage of menstrual disorders compared to the general population. As a practical implication, the review reinforces the importance of coaches and physicians, especially from the sports disciplines with a high risk of menstrual disorders, to monitor the menstrual cycle regularity of the athletes as the occurrence of these disorders can be associated with impairment on some health components.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph192114243/s1, Table S1: Checklist for quality assessment of the studies; Table S2: Adjusted Downs and Black Assessment Checklist evaluation; Table S3: Supplementary data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G. and A.P.; methodology, A.C.P.; formal analysis, A.C.P.; investigation, A.P.; data curation, A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G. and A.C.P.; writing—review and editing, A.P. and M.B.; visualization, A.C.P.; supervision, M.B.; project administration, M.B.; funding acquisition, M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it was a rapid literature review, and no new data were collected.

Informed Consent Statement

Inform consent was not necessary because the study synthesized the data from previous articles.

Data Availability Statement

No data was created in this study. Data sharing is no applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Funding Statement

This project was supported by the Specific University Research Grant provided by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic (number MUNI/A/1389/2021). The ACP is support by the Evaluation of Graduate Education, and from Operational Programme Research, Development and Education Project “Postdoc2MUNI” (No. CZ.02.2.69/0.0/0.0/18_053/0016952).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.de Souza M.J., Toombs R.J., Scheid J.L., O’Donnell E., West S.L., Williams N.I. High Prevalence of Subtle and Severe Menstrual Disturbances in Exercising Women: Confirmation Using Daily Hormone Measures. Hum. Reprod. 2010;25:491–503. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redman L.M., Loucks A.B. Menstrual Disorders in Athletes. Sport. Med. 2005;35:747–755. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200535090-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loucks A.B., Thuma J.R. Luteinizing Hormone Pulsatility Is Disrupted at a Threshold of Energy Availability in Regularly Menstruating Women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88:297–311. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ackerman K.E., Misra M. Amenorrhoea in Adolescent Female Athletes. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health. 2018;2:677–688. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rickenlund A., Eriksson M.J., Schenck-Gustafsson K., Hirschberg A.L. Amenorrhea in Female Athletes Is Associated with Endothelial Dysfunction and Unfavorable Lipid Profile. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;90:1354–1359. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gasner A., Rehman A. Primary Amenorrhea. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island, FL, USA: 2022. StatPearls [Internet] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rebar R. Evaluation of Amenorrhea, Anovulation, and Abnormal Bleeding. MDText.com, Inc.; South Dartmouth, MA, USA: 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein D.A., Poth M.A. Amenorrhea: An Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Am. Fam. Physician. 2013;87:781–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon C.M. Clinical Practice Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:365–371. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0912024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stárka L., Dušková M. Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea. Vnitřní Lékařství. 2015;61:882–885. doi: 10.36290/vnl.2015.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shufelt C., Torbati T., Dutra E. Hypothalamic Amenorrhea and the Long-Term Health Consequences. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2017;35:256–262. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1603581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon C.M., Ackerman K.E., Berga S.L., Kaplan J.R., Mastorakos G., Misra M., Murad M.H., Santoro N.F., Warren M.P. Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017;102:1413–1439. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-00131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts R.E., Farahani L., Webber L., Jayasena C. Current Understanding of Hypothalamic Amenorrhoea. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020;11:204201882094585. doi: 10.1177/2042018820945854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Begum M., Das S., Sharma H.K. Menstrual Disorders: Causes and Natural Remedies. J. Pharm. Chem. Biol. Sci. 2016;4:307–320. [Google Scholar]

- 15.He Y., Zheng D., Shang W., Wang X., Zhao S., Wei Z., Song X., Shi X., Zhu Y., Wang S., et al. Prevalence of Oligomenorrhea among Women of Childbearing Age in China: A Large Community-Based Study. Women’s Health. 2020;16:174550652092861. doi: 10.1177/1745506520928617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yavari M., Khodabandeh F., Tansaz M., Rouholamin S., Rouholamin Beheshti S. A Neuropsychiatric Complication of Oligomenorrhea According to Iranian Traditional Medicine. Iran. J. Reprod. Med. 2014;12:453–458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reardon C.L., Hainline B., Aron C.M., Baron D., Baum A.L., Bindra A., Budgett R., Campriani N., Castaldelli-Maia J.M., Currie A., et al. Mental Health in Elite Athletes: International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement (2019) Br. J. Sport. Med. 2019;53:667–699. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Logue D., Madigan S.M., Delahunt E., Heinen M., Mc Donnell S.J., Corish C.A. Low Energy Availability in Athletes: A Review of Prevalence, Dietary Patterns, Physiological Health, and Sports Performance. Sport. Med. 2018;48:73–96. doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0790-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrne S., McLean N. Elite Athletes: Effects of the Pressure to Be Thin. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2002;5:80–94. doi: 10.1016/S1440-2440(02)80029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garritty C., Gartlehner G., Nussbaumer-Streit B., King V.J., Hamel C., Kamel C., Affengruber L., Stevens A. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group Offers Evidence-Informed Guidance to Conduct Rapid Reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021;130:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haby M.M., Chapman E., Clark R., Barreto J., Reveiz L., Lavis J.N. What Are the Best Methodologies for Rapid Reviews of the Research Evidence for Evidence-Informed Decision Making in Health Policy and Practice: A Rapid Review. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2016;14:83. doi: 10.1186/s12961-016-0155-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., Shamseer L., Tetzlaff J.M., Akl E.A., Brennan S.E., et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olympic Games List of Sports. 2022. [(accessed on 21 September 2022)]. Available online: https://olympics.com/en/sports/

- 24.Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Downs S.H., Black N. The Feasibility of Creating a Checklist for the Assessment of the Methodological Quality Both of Randomised and Non-Randomised Studies of Health Care Interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 1998;52:377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meignié A., Duclos M., Carling C., Orhant E., Provost P., Toussaint J.F., Antero J. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Elite Athlete Performance: A Critical and Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 2021;12:654585. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.654585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McNulty K.L., Elliott-Sale K.J., Dolan E., Swinton P.A., Ansdell P., Goodall S., Thomas K., Hicks K.M. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sport. Med. 2020;50:1813–1827. doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01319-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elliott-Sale K.J., McNulty K.L., Ansdell P., Goosdall S., Hicks K.M., Thomas K., Swinton P.A., Dolan E. The Effects of Oral Contraceptives on Exercise Performance in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sport. Med. 2020;50:1785–1812. doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01317-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camomilla V., Bergamini E., Fantozzi S., Vannozzi G. Trends Supporting the In-Field Use of wearable Inertial Sensors for Sport Performance Evaluation: A Systematic Review. Sensors. 2018;18:873. doi: 10.3390/s18030873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klinkowski N., Korte A., Pfeiffer E., Lehmkuhl U., Salbach-Andrae H. Psychopathology in Elite Rhythmic Gymnasts and Anorexia Nervosa Patients. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2008;17:108–113. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0643-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klentrou P., Plyley M. Onset of Puberty, Menstrual Frequency, and Body Fat in Elite Rhythmic Gymnasts Compared with Normal Controls. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2003;37:490–494. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.6.490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollock N., Grogan C., Perry M., Pedlar C., Cooke K., Morrissey D., Dimitriou L. Bone-Mineral Density and Other Features of the Female Athlete Triad in Elite Endurance Runners: A Longitudinal and Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2010;20:418–426. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.20.5.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tenforde A.S., Carlson J.L., Chang A., Sainani K.L., Shultz R., Kim J.H., Cutti P., Golden N.H., Fredericson M. Association of the Female Athlete Triad Risk Assessment Stratification to the Development of Bone Stress Injuries in Collegiate Athletes. Am. J. Sport. Med. 2017;45:302–310. doi: 10.1177/0363546516676262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mudd L.M., Fornetti W., Pivarnik J.M. Bone Mineral Density in Collegiate Female Athletes: Comparisons Among Sports. J. Athl. Train. 2007;42:403–408. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meng K., Qiu J., Benardot D., Carr A., Yi L., Wang J., Liang Y. The Risk of Low Energy Availability in Chinese Elite and Recreational Female Aesthetic Sports Athletes. J. Int. Soc. Sport. Nutr. 2020;17:13. doi: 10.1186/s12970-020-00344-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.di Cagno A., Marchetti M., Battaglia C., Giombini A., Calcagno G., Fiorilli G., Piazza M., Pigozzi F., Borrione P. Is Menstrual Delay a Serious Problem for Elite Rhythmic Gymnasts? J. Sport. Med. Phys. Fit. 2012;52:647–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egan E., Reilly T., Whyte G., Giacomoni M., Cable N.T. Disorders of the Menstrual Cycle in Elite Female Ice Hockey Players and Figure Skaters. Biol. Rhythm Res. 2003;34:251–264. doi: 10.1076/brhm.34.3.251.18806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramsay R. Are Synchronised Swimmers at Risk of Amenorrhoea? Br. J. Sport. Med. 2001;35:242–244. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.35.4.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dusek T. Influence of High Intensity Training on Menstrual Cycle Disorders in Athletes. Croat. Med. J. 2001;42:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prather H., Hunt D., McKeon K., Simpson S., Meyer E.B., Yemm T., Brophy R. Are Elite Female Soccer Athletes at Risk for Disordered Eating Attitudes, Menstrual Dysfunction, and Stress Fractures? PMR. 2016;8:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nattiv A., Kennedy G., Barrack M.T., Abdelkerim A., Goolsby M.A., Arends J.C., Seeger L.L. Correlation of MRI Grading of Bone Stress Injuries with Clinical Risk Factors and Return to Play: A 5-Year Prospective Study in Collegiate Track and Field Athletes. Am. J. Sport. Med. 2013;41:1930–1941. doi: 10.1177/0363546513490645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jesus F., Castela I., Silva A.M., Branco P.A., Sousa M. Risk of Low Energy Availability among Female and Male Elite Runners Competing at the 26th European Cross-Country Championships. Nutrients. 2021;13:873. doi: 10.3390/nu13030873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schtscherbyna A., Soares E.A., de Oliveira F.P., Ribeiro B.G. Female Athlete Triad in Elite Swimmers of the City of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Nutrition. 2009;25:634–639. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibson J.H., Harries M., Mitchell A., Godfrey R., Lunt M., Reeve J. Determinants of Bone Density and Prevalence of Osteopenia among Female Runners in Their Second to Seventh Decades of Age. Bone. 2000;26:591–598. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(00)00274-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dimitriou L., Weiler R., Lloyd-Smith R., Turner A., Heath L., James N., Reid A. Bone Mineral Density, Rib Pain and Other Features of the Female Athlete Triad in Elite Lightweight Rowers. BMJ Open. 2014;4:4369. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haakonssen E.C., Martin D.T., Jenkins D.G., Burke L.M. Race Weight: Perceptions of Elite Female Road Cyclists. Int. J. Sport. Physiol. Perform. 2015;10:311–317. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2014-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duckham R.L., Brooke-Wavell K., Summers G.D., Cameron N., Peirce N. Stress Fracture Injury in Female Endurance Athletes in the United Kingdom: A 12-Month Prospective Study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2015;25:854–859. doi: 10.1111/sms.12453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson S.H. Characteristics of the Female Athlete Triad in Collegiate Cross-Country Runners. J. Am. Coll. Health. 2007;56:129–136. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.2.129-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barrack M.T., Rauh M.J., Nichols J.F. Prevalence of and Traits Associated with Low BMD among Female Adolescent Runners. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2008;40:2015–2021. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181822ea0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barrack M.T., van Loan M.D., Rauh M.J., Nichols J.F. Physiologic and Behavioral Indicators of Energy Deficiency in Female Adolescent Runners with Elevated Bone Turnover. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010;92:652–659. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hutson M.J., O’Donnell E., Petherick E., Brooke-Wavell K., Blagrove R.C. Incidence of Bone Stress Injury Is Greater in Competitive Female Distance Runners with Menstrual Disturbances Independent of Participation in Plyometric Training. J. Sport. Sci. 2021;39:2558–2566. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2021.1945184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muia E.N., Wright H.H., Onywera V.O., Kuria E.N. Adolescent Elite Kenyan Runners Are at Risk for Energy Deficiency, Menstrual Dysfunction and Disordered Eating. J. Sport. Sci. 2016;34:598–606. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2015.1065340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beckvid Henriksson G., Schnell C., Lindén Hirschberg A. Women Endurance Runners with Menstrual Dysfunction Have Prolonged Interruption of Training Due to Injury. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2000;49:41–46. doi: 10.1159/000010211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burrows M., Nevill A.M., Bird S. Physiological Factors Associated with Low Bone Mineral Density in Female Endurance Runners. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2003;37:67–71. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cobb K.L., Bachrach L.K., Greendale G., Marcus R., Neer R.M., Nieves J., Sowers M.F., Brown B.W., Gopalakrishnan G., Luetters C., et al. Disordered Eating, Menstrual Irregularity, and Bone Mineral Density in Female Runners. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2003;35:711–719. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000064935.68277.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tenforde A.S., Fredericson M., Sayres L.C., Cutti P., Sainani K.L. Identifying Sex-Specific Risk Factors for Low Bone Mineral Density in Adolescent Runners. Am. J. Sport. Med. 2015;43:1494–1504. doi: 10.1177/0363546515572142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rauh M.J., Barrack M., Nichols J.F. Associations between the Female Athlete Triad and Injury among High School Runners. Int. J. Sport. Phys. Ther. 2014;9:948–958. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walsh M., Crowell N., Merenstein D. Exploring Health Demographics of Female Collegiate Rowers. J. Athl. Train. 2020;55:636–643. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-132-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coste O., Paris F., Galtier F., Letois F., Maïmoun L., Sultan C. Polycystic Ovary–like Syndrome in Adolescent Competitive Swimmers. Fertil. Steril. 2011;96:1037–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsukahara Y., Torii S., Yamasawa F., Iwamoto J., Otsuka T., Goto H., Kusakabe T., Matsumoto H., Akama T. Bone Parameters of Elite Athletes with Oligomenorrhea and Prevalence Seeking Medical Attention: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2021;39:1009–1018. doi: 10.1007/s00774-021-01234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sygo J., Coates A.M., Sesbreno E., Mountjoy M.L., Burr J.F. Prevalence of Indicators of Low Energy Availability in Elite Female Sprinters. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2018;28:490–496. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2017-0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robbeson J.G., Havemann-Nel L., Wright H.H. The Female Athlete Triad in Student Track and Field Athletes. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013;26:19–24. doi: 10.1080/16070658.2013.11734446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feldmann J.M., Belsha J.P., Eissa M.A., Middleman A.B. Female Adolescent Athletes’ Awareness of the Connection between Menstrual Status and Bone Health. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2011;24:311–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoch A.Z., Stavrakos J.E., Schimke J.E. Prevalence of Female Athlete Triad Characteristics in a Club Triathlon Team. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007;88:681–682. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Duckham R.L., Peirce N., Bailey C.A., Summers G., Cameron N., Brooke-Wavell K. Bone Geometry According to Menstrual Function in Female Endurance Athletes. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2013;92:444–450. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9700-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Raymond-Barker P., Petroczi A., Quested E. Assessment of Nutritional Knowledge in Female Athletes Susceptible to the Female Athlete Triad Syndrome. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2007;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1745-6673-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maïmoun L., Coste O., Georgopoulos N.A., Roupas N.D., Mahadea K.K., Tsouka A., Mura T., Philibert P., Gaspari L., Mariano-Goulart D., et al. Despite a High Prevalence of Menstrual Disorders, Bone Health Is Improved at a Weight-Bearing Bone Site in World-Class Female Rhythmic Gymnasts. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98:4961–4969. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roupas N.D., Maïmoun L., Mamali I., Coste O., Tsouka A., Mahadea K.K., Mura T., Philibert P., Gaspari L., Mariano-Goulart D., et al. Salivary Adiponectin Levels Are Associated with Training Intensity but Not with Bone Mass or Reproductive Function in Elite Rhythmic Gymnasts. Peptides. 2014;51:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Salbach H., Klinkowski N., Pfeiffer E., Lehmkuhl U., Korte A. Body Image and Attitudinal Aspects of Eating Disorders in Rhythmic Gymnasts. Psychopathology. 2007;40:388–393. doi: 10.1159/000106469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Muñoz Calvo M.T., de la Piedra C., Barrios V., Garrido G., Argente J. Changes in Bone Density and Bone Markers in Rhythmic Gymnasts and Ballet Dancers: Implications for Puberty and Leptin Levels. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2004;151:491–496. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1510491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Czajkowska M., Plinta R., Rutkowska M., Brzęk A., Skrzypulec-Plinta V., Drosdzol-Cop A. Menstrual Cycle Disorders in Professional Female Rhythmic Gymnasts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:1470. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16081470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Helge W.E., Kanstrup I. Bone Density in Female Elite Gymnasts: Impact of Muscle Strength and Sex Hormones. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2002;34:174–180. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200201000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Corujeira S., Vieira T., Dias C. Gymnastics and the Female Athlete Triad: Reality or Myth? Sci. Gymnast. J. 2012;4:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Trutschnigg B., Chong C., Habermayerova L., Karelis A.D., Komorowski J. Female Boxers Have High Bone Mineral Density despite Low Body Fat Mass, High Energy Expenditure, and a High Incidence of Oligomenorrhea. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2008;33:863–869. doi: 10.1139/H08-071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Oliveira Coelho G.M., de Farias M.L.F., de Mendonça L.M.C., de Mello D.B., Lanzillotti H.S., Ribeiro B.G., de Abreu Soares E. The Prevalence of Disordered Eating and Possible Health Consequences in Adolescent Female Tennis Players from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Appetite. 2013;64:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Meyer N.L., Shaw J.M., Manore M.M., Dolan S.H., Subudhi A.W., Shultz B.B., Walker J.A. Bone Mineral Density of Olympic-Level Female Winter Sport Athletes. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2004;36:1594–1601. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000139799.20380.DA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Czajkowska M., Drosdzol-Cop A., Gałazka I., Naworska B., Skrzypulec-Plinta V. Menstrual Cycle and the Prevalence of Premenstrual Syndrome/Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder in Adolescent Athletes. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2015;28:492–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.02.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Calthorpe L., Brage S., Ong K.K. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between childhood physical activity and age at menarche. Acta Paediatr. 2018;108:1008–1015. doi: 10.1111/apa.14711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wodarska M., Witkoś J., Drosdzol-Cop A., Dąbrowska J., Dąbrowska-Galas M., Hartman M., Plinta R., Skrzypulec-Plinta V. Menstrual Cycle Disorders in Female Volleyball Players. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013;33:484–488. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2013.790885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Roupas N.D., Georgopoulos N.A. Menstrual Function in Sports. Hormones. 2011;10:104–116. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Theodoropoulou A., Markou K.B., Vagenakis G.A., Benardot D., Leglise M., Kourounis G., Vagenakis A.G., Georgopoulos N.A. Delayed but Normally Progressed Puberty Is More Pronounced in Artistic Compared with Rhythmic Elite Gymnasts Due to the Intensity of Training. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;90:6022–6027. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Carmina E. Mild androgen phenotypes. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;20:207–220. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zafar M., Sadeeqa S., Latif S., Afzal H. Pattern and Prevalance of Menstrual Disoreders in Adolescents. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2018;9:2088–2099. doi: 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.9(5).2088-99. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Warren M.P., Ramos R.H., Bronson E.M. Exercise-Associated Amenorrhea. Physician Sport. Med. 2002;30:41–46. doi: 10.3810/psm.2002.10.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Otis C.L., Drinkwater B., Johnson M., Loucks A., Wilmore J. ACSM Position Stand: The Female Athlete Triad. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 1997;29:i–ix. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199705000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nooh A.M., Abdul-Hady A., El-Attar N. Nature and Prevalence of Menstrual Disorders among Teenage Female Students at Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2016;29:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Omani Samani R., Almasi Hashiani A., Razavi M., Vesali S., Rezaeinejad M., Maroufizadeh S., Sepidarkish M. The Prevalence of Menstrual Disorders in Iran: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2018;16:665–678. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.de Souza M.J., Nattiv A., Joy E., Misra M., Williams N.I., Mallinson R.J., Gibbs J.C., Olmsted M., Goolsby M., Matheson G. 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition Consensus Statement on Treatment and Return to Play of the Female Athlete Triad: 1st International Conference Held in San Francisco, California, May 2012 and 2nd International Conference Held in Indianapolis, Indiana, May 2013. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2014;48:289. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Trompeter K., Fett D., Platen P. Prevalence of Back Pain in Sports: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sport. Med. 2017;47:1183–1207. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0645-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data was created in this study. Data sharing is no applicable to this article.