Significance

Thyroid hormone (TH) signaling is important for gene regulation and plays an essential role in brain development. However, it remains unknown how TH signaling affects neuronal functions in adulthood. Using a transgenic mouse (Mf-1) lacking TH signaling only in cerebellar Purkinje cells, we found motor defects and altered long-term synaptic plasticity at parallel fiber–Purkinje cell (PC) synapses in adult Mf-1 mice. Long-term depression was switched to long-term potentiation. This is caused by reduced calcium signals in adult Mf-1 PCs, because genes related to internal calcium release machinery are down-regulated. These phenotypes are not ascribed to adult-onset deficiency of TH signaling in PCs. Our results suggest that TH signaling in neurons during development has decisive effects on neuronal functions in adulthood.

Keywords: thyroid hormone, cerebellar Purkinje cell, long-term depression, motor coordination, intracellular calcium dynamics

Abstract

Thyroid hormones (THs) regulate gene expression by binding to nuclear TH receptors (TRs) in the cell. THs are indispensable for brain development. However, we have little knowledge about how congenital hypothyroidism in neurons affects functions of the central nervous system in adulthood. Here, we report specific TH effects on functional development of the cerebellum by using transgenic mice overexpressing a dominant-negative TR (Mf-1) specifically in cerebellar Purkinje cells (PCs). Adult Mf-1 mice displayed impairments in motor coordination and motor learning. Surprisingly, long-term depression (LTD)–inductive stimulation caused long-term potentiation (LTP) at parallel fiber (PF)–PC synapses in adult Mf-1 mice, although there was no abnormality in morphology or basal properties of PF–PC synapses. The LTP phenotype was turned to LTD in Mf-1 mice when the inductive stimulation was applied in an extracellular high-Ca2+ condition. Confocal calcium imaging revealed that dendritic Ca2+ elevation evoked by LTD-inductive stimulation is significantly reduced in Mf-1 PCs but not by PC depolarization only. Single PC messenger RNA quantitative analysis showed reduced expression of SERCA2 and IP3 receptor type 1 in Mf-1 PCs, which are essential for mGluR1-mediated internal calcium release from endoplasmic reticulum in cerebellar PCs. These abnormal changes were not observed in adult-onset PC-specific TH deficiency mice created by adeno-associated virus vectors. Thus, we propose the importance of TH action during neural development in establishing proper cerebellar function in adulthood, independent of its morphology. The present study gives insight into the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying congenital hypothyroidism–induced dysfunctions of central nervous system and cerebellum.

Thyroid hormones (THs including triiodothyronine and thyroxine) regulate gene expression by binding to nuclear TH receptors (TRs) in most cells (1). TRs form a heterodimer with a retinoid X receptor and bind to a specific DNA enhancer sequence known as a TH response element (TRE). Activated TRs function as a transcription factor and affect expression of their target genes.

THs are indispensable for the proper development of many organs, especially the brain (2). Perinatal TH deficiency causes congenital hypothyroidism. If infants with congenital hypothyroidism are not properly treated early, severe cognitive and motor impairments will persist into adulthood (3). In animal models, rats with congenital hypothyroidism have severe impairments of motor coordination and cerebellar morphogenesis, characterized by small somata, poor dendritic arborization of Purkinje cells (PCs), and retarded migration of granule cells (GCs) during the first 2 postnatal weeks (4). Although the expressions of several important genes for cerebellar function are altered in mice with congenital hypothyroidism at postnatal day (PD) 15, expressions of most genes are restored later in adulthood (5, 6). Nevertheless, motor deficits persist in adult mice with congenital hypothyroidism (7). These studies strongly suggest that congenital hypothyroidism–induced impaired cerebellar development may lead to impaired cerebellar function in adulthood. However, most of the previous studies were limited to developmental stages, and the mechanism underlying the persistent functional impairment in the adult stage is yet to be clarified.

For conventional studies of congenital hypothyroidism, inhibitors of TH synthesis, such as propylthiouracil, are used to generate dams with hypothyroidism (8). In this model, all cells expressing TRs are affected by the global hypothyroidism. Thus, it is impossible to distinguish cell type–specific effects of TH on cerebellar function. To solve this problem, we previously generated transgenic mice (Mf-1 mice) overexpressing a mutant TR specifically in PCs, the sole output neurons in the cerebellar cortex (9). Mf-1 mice undergo dominant-negative inhibition of TH signaling selectively in cerebellar PCs innately, and we can examine PC-specific effects of TH signaling with these mice (10). Mf-1 mice displayed delayed GC migration and retarded PC morphological maturation during development (10). At PDs 7 and 15, messenger RNA (mRNA) of inositol 1, 4, 5-triphosphate receptor type 1 (IP3R1), which plays a pivotal role in cerebellar synaptic plasticity and motor coordination (11), was significantly decreased in the developing cerebellum of Mf-1 mice (10). At PD 30 (young adult age), gross morphology of the cerebellum was restored from the developmental retardation, but motor defects were still observed in Mf-1 mice at this age (10). Thus, it is intriguing to clarify the mechanism of the persistent functional impairment in adult Mf-1 mice at the cellular, molecular, and synaptic levels.

In the present study, using adult Mf-1 mice, which lack TH signaling specifically in cerebellar PCs from birth, we examined motor performance, synaptic properties, and molecular changes in adult Mf-1 PCs. Our results show motor deficits and alteration of long-term synaptic plasticity in adult Mf-1 mice, which is caused by reduced dendritic Ca2+ signals in Mf-1 PCs. Our viral vector–mediated adult-onset TH deficiency experiments suggest that these functional changes are developmentally determined, not caused by TH signaling effects in adulthood.

Results

Motor Impairment without Alteration of Muscle Strength in Adult Mf-1 Mice.

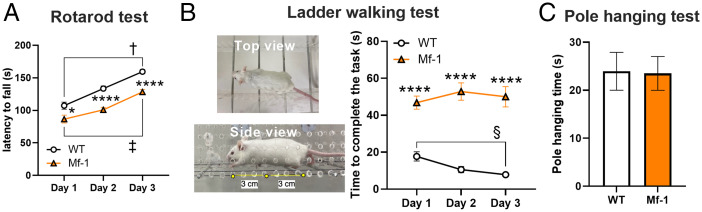

To demonstrate the effect of TH action on motor behavior in adult mice (PD >70), the rotarod test and the ladder walking test were performed. In the rotarod test (Fig. 1A), which is supposed to measure motor performance in the forced movement task, latency to fall (i.e., time spent on the rotating rod) was significantly shorter in adult Mf-1 mice than age-matched wild type (WT) mice for all three days (WT n = 17; Mf-1 n = 16; two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, genotype effect P < 0.0001, day × genotype P = 0.246; multiple comparison tests [WT vs. Mf-1], day 1 P < 0.05, day 2 P < 0.0001, day 3 P < 0.0001). However, the motor performance improved over time in both groups (day 1 vs. day 3, Wilcoxon’s matched-pairs signed rank test, WT, P < 0.0001; Mf-1, P < 0.0005), suggesting that motor learning is still preserved for this forced movement task in Mf-1 mice. In the ladder walking test (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1) which is the task for examining voluntary and more complex movement, adult Mf-1 mice took significantly longer time to complete the task on all days tested (WT n = 10; Mf-1 n = 10; two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, genotype effect P < 0.0001, day × genotype P < 0.05; multiple comparison tests [WT vs. Mf-1], day 1 P < 0.0001, day 2 P < 0.0001, day 3, P < 0.0001). The Mf-1 mice did not improve their performance from day 1 to day 3 (day 1 vs. day 3, Wilcoxon’s matched-pairs signed rank test, WT, P < 0.005; Mf-1, P = 0.695), indicating the impairment of motor learning in this task. An ataxic gait pattern was also observed in adult Mf-1 mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). However, there was no difference in grip muscle strength evaluated by pole hanging test between adult WT and Mf-1 mice (Fig. 1C) (WT n = 12, Mf-1 n = 12, P = 0.90). These results suggest that adult Mf-1 mice show impairments in motor coordination or body balance and motor learning deficits depending on task difficulty.

Fig. 1.

Mf-1 mice show impaired motor performance with no change in muscle strength. (A) The results of the rotarod test for three consecutive days are shown for each group (WT, open circles; Mf-1 mice, filled triangles). Mf-1 mice stayed on the rotating rod for less time than WT mice (day 1 WT vs. Mf-1, *P < 0.05, days 2 and 3 WT vs. Mf-1, ****P < 0.0001), although both mice improved their performance on day 3 compared to day 1 (Wilcoxon’s matched-pairs signed rank test, WT, † P < 0.0001; Mf-1, ‡ P < 0.001). (B) Horizontal ladder walking test. Left, top-view and side-view images of the ladder apparatus (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Right, pooled data of the ladder test in WT (open circles) and Mf-1 mice (filled triangles). Mf-1 mice showed much longer time to complete the task than WT mice (days 1–3, WT vs. Mf-1, ****P < 0.0001) and no improvement of the performance at day 3 compared to day 1, in contrast to WT mice (Wilcoxon’s matched-pairs signed rank test for improvement, WT, §P < 0.01). (C) Pole hanging test to examine the difference of muscle strength between WT and Mf-1 mice. No statistical difference was observed (Mann–Whitney test, P = 0.90).

mGluR1-Dependent Long-Term Depression Is Switched to Long-Term Potentiation with No Change in Basal Synaptic Properties in Adult Mf-1 Mice.

The plastic change in cerebellar synaptic transmission from parallel fibers (PFs, axonal fibers extended from GCs) to PCs plays important roles in regulating motor behaviors (12). In particular, long-term depression (LTD) at PF–PC synapses is involved in motor learning and motor coordination (9, 13, 14). Thus, we characterized the properties of PF–PC synapses in adult Mf-1 mice.

First, we examined the basic morphological and functional properties of PF–PC synapses. In line with the previous reports (10, 15), formation of cerebellar granule cells was intact in adult Mf-1 mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Moreover, there was no major morphological difference in PC arborization (immunostained against calbindin, a PC-specific marker) and PF presynaptic terminals (immunostained against vesicular glutamate transporter type 1, a PF presynaptic terminal marker) in adult Mf-1 mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), suggesting that formation of PF–PC synapses is intact in Mf-1 mice. We also examined the basal synaptic responses at PF–PC synapses in adult Mf-1 mice. There was no significant difference in the amplitudes of fast α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in response to various electrical stimulus strengths applied to PFs between WT and Mf-1 mice at adult age (WT n = 18 from 11 mice, Mf-1 n = 14 from 7 mice; two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, genotype effect, P = 0.36) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B).Short-term synaptic plasticity of PF–PC EPSCs examined by a paired-pulse protocol with varied interstimulus intervals was also similar between WT and Mf-1 mice (WT n = 16 from four mice, Mf-1 n = 15 from six mice; two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, genotype effect, P = 0.61) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). These results suggest that the basal properties of PF–PC synapses are intact in adult Mf-1 mice.

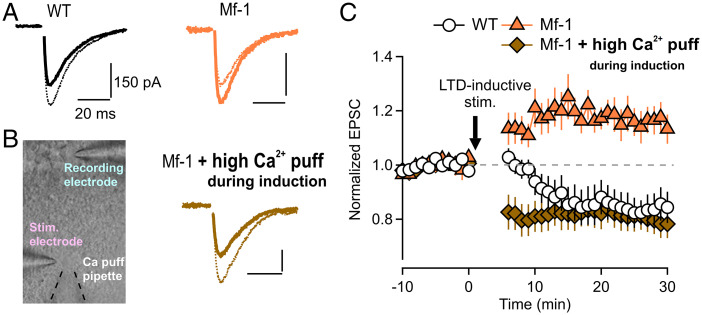

Next, we examined one type of long-term synaptic plasticity, LTD at PF–PC synapses by using a typical LTD induction protocol (30 repetitions of PF burst stimulation paired simultaneously with PC depolarization [conjunctive stimulus] at 1 Hz; SI Methods). LTD was induced in adult WT mice, but long-term potentiation (LTP) was observed in adult Mf-1 mice even though the same LTD-inductive stimulation was applied (WT 0.82 ± 0.05 normalized to baseline EPSC, n = 9 from five mice; Mf-1 1.16 ± 0.05 normalized to baseline EPSC, n = 8 from six mice; WT vs. Mf-1 P < 0.001) (Fig. 2 A and C). We confirmed that these opposing plastic changes in WT and Mf-1 are both postsynaptic in origin, because paired pulse ratio (PPR), whose change can be a good indicator of presynaptic change (16), remained constant after plasticity induction both in WT and Mf-1 mice (WT 1.00 ± 0.03 [normalized values to baseline PPR], n = 7 from five mice, Mf-1 0.99 ± 0.02 [normalized values to baseline PPR], n = 10 from six mice). Moreover, a metabotropic glutamate receptor type 1 (mGluR1)-selective blocker, CPCCOEt (100 µM), occluded the induction of both LTD in WT PCs (n = 8 from five mice) and LTP in Mf-1 PCs (n = 9 from five mice) (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). These results indicate that the same LTD-inductive stimulation causes LTD in adult WT PCs but LTP in Mf-1, although these opposing phenotypes are both mediated by the same postsynaptic mGluR1 pathway.

Fig. 2.

LTD-inductive stimulation causes LTP at cerebellar PF–PC synapses in adult Mf-1 mice but normal LTD with extracellular local high-Ca2+ application during the induction. (A) The representative traces of PF-evoked EPSCs in WT (Left) and Mf-1 (Right) mice before (dotted line) and 25–30 min after LTD-inductive stimulation (solid line). Stimulus artifacts were blanked in this and subsequent figures. The inductive stimulation was composed of 30 repetitions (at an interval of 1 s) of PF burst (10 PF stimuli at 50 Hz) paired with PC depolarization from −60 to +20 mV for 500 ms. (B) Left, experimental configuration (high-Ca2+ puff) in an acute cerebellar slice where high-Ca2+ (8 mM) extracellular artificial cerebrospinal fluid solution was applied locally to a PF-stimulating site via a puff pipette (delineated with broken lines) only during the induction (the duration of the puff application was ∼35 s). After the induction, the puff pipette was soon retracted away from the cerebellar slice. Right, representative traces of PF EPSC as in (A) except that the data were recorded from an adult Mf-1 PC under the high-Ca2+ puff configuration. (C) Pooled data of PF EPSC amplitudes normalized to the basal EPSC value (i.e., the average of the 10 min synaptic responses just before the LTD-inductive stimulation indicated by an arrow). In contrast to WT (open circles), the inductive stimulation caused long-lasting synaptic potentiation (i.e., LTP) in Mf-1 mice (filled triangles). However, LTD was induced even in Mf-1 mice when high-Ca2+ extracellular solution was applied locally to the stimulation site during the induction (filled diamonds).

PF–PC synapses have mGluR1-mediated, calcium-dependent, bidirectional, postsynaptic long-term plasticity (17, 18), and the intracellular calcium signals including mGluR1 pathway in PCs during plasticity induction determine the direction of plasticity at PF–PC synapses (19, 20). Namely, LTD is induced by higher concentrations of intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) in postsynaptic PCs, whereas LTP requires lower [Ca2+]i (the inverse Bienenstock–Cooper–Munro (BCM) rule) (18, 21). Based on this scheme, we hypothesize that the LTP phenotype could be turned to normal LTD as long as Ca2+ signals during the induction are enhanced in Mf-1 PCs. To test this hypothesis, we performed local application of external high-Ca2+ artificial cerebrospinal fluid solution via a puff pipette to the stimulating site only during LTD-inductive stimulation (Fig. 2B, Left; SI Appendix, Methods) in order to increase Ca2+ influx to Mf-1 PCs during induction. As expected, LTD was rescued in adult Mf-1 PCs in this condition (Fig. 2 B and C, Mf-1 + high-Ca2+ puff during induction) (0.79 ± 0.05 normalized to baseline EPSC, n = 10 from six mice), and PPR remained similar after the induction (0.95 ± 0.04 [normalized values to baseline PPR], n = 10 from six mice), suggesting that the rescued phenotype is also caused postsynaptically. Collectively, the results above suggest that the LTP phenotype at PF–PC synapses in adult Mf-1 mice may be caused by reduced Ca2+ signals in PCs during induction and that LTD expression machinery itself is intact in adult Mf-1 mice.

PF-Evoked Dendritic Ca2+ Signals Are Reduced in PCs of Adult Mf-1 Mice during LTD-Inductive Stimulation.

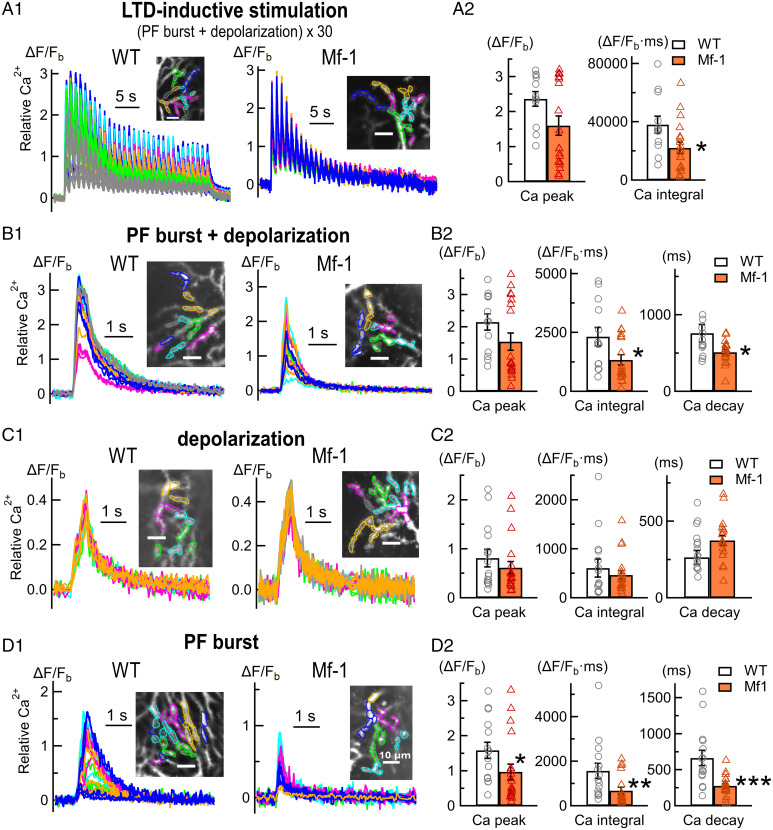

Next, we examined intracellular Ca2+ dynamics in adult PCs during LTD-inductive stimulation with confocal live Ca2+ imaging in order to test reduced Ca2+ signals in Mf-1 PCs directly. In LTD-inductive stimulation (30 repeats of the conjunctive stimulus at 1 Hz), which spanned ∼30 s, dendritic Ca2+ responses in Mf-1 PCs tended to be smaller than WT PCs (Fig. 3A). Especially, the late Ca2+ responses were reduced in adult Mf-1 PCs (Fig. 3A1), and the integral of the Ca2+ signals during the stimulation was significantly smaller in Mf-1 (Fig. 3A2) (Ca2+ integral [ΔF/Fb·ms]: WT 38,150 ± 5,842, n = 12 cells from six mice; Mf-1 22,075 ± 4,000, n = 19 cells from six mice, P < 0.05). The peak of the Ca2+ signals in Mf-1 seemed smaller than WT, although the difference was not statistically significant (ΔF/Fb peak: WT 2.37 ± 0.21, n = 12 cells from six mice; Mf-1 1.60 ± 0.28, n = 19 cells from six mice, P = 0.12). These results clearly indicate that LTD-inductive stimulation causes reduced dendritic Ca2+ signals in adult Mf-1 PCs compared to WT PCs.

Fig. 3.

Reduction of PF-mediated local dendritic Ca2+ signals in Mf-1 PCs. (A1, B1, C1, and D1) Representative local dendritic calcium signals in PCs of WT (Left) and Mf-1 mice (Right) in response to various stimulation protocols. “PF burst” corresponds to 10 stimuli to PFs at 50 Hz. “Depolarization” corresponds to a single voltage pulse from –60 to +20 mV for 500 ms. “PF burst + depolarization” corresponds to 10 stimuli to PFs at 50 Hz in conjunction with a voltage pulse from –60 to +20 mV for 500 ms. “LTD-inductive stimulation” corresponds to 30 repetitions of the PF burst + depolarization protocol at 1 Hz. Inset images with scale bars (10 µm) show regions of interest (ROIs) on the dendrites of each recorded cell, and the individual relative calcium signals (ΔF/Fb traces; SI Methods) originate from the ROIs with the same color code in each panel. (A2, B2, C2, and D2) Pooled data of quantified calcium signals (SI Methods) in each protocol of (A1, B1, C1, and D1), respectively (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005, Mann–Whitney test). In LTD-inductive stimulation, Ca2+ signal decay was not quantified because the Ca2 signal had multiple peaks (A1), making it difficult to reliably estimate the overall time course of the signal.

LTD-inductive stimulation consisted of 30 repetitions of the conjunctive stimuli. The single conjunctive stimulus consists of PF burst stimulation (10 electrical pulses to PFs at 50 Hz, referred to as PF burst) combined simultaneously with PC depolarization (a single voltage pulse from –60 to +20 mV for 500 ms, referred to as depolarization). To determine which stimulus parameter of the LTD-inductive stimulation was related to the reduction in Ca2+ signals in adult Mf-1 PCs, we examined dendritic Ca2+ signals evoked by three separated stimulus patterns, namely the single conjunctive stimulus (PF burst + depolarization), depolarization, and PF burst. In the single conjunctive stimulus, dendritic Ca2+ signals in Mf-1 PCs were reduced and decayed faster compared to WT (Fig. 3B). The integral and half-decay time of Ca2+ signals were significantly smaller in adult Mf-1 PCs (Fig. 3B2) (Ca2+ integral: WT 2,320 ± 394, n = 13 cells from seven mice; Mf-1 1,340 ± 221, n = 19 cells from six mice, P < 0.05; Ca2+ decay time [ms]: WT 759 ± 115, n = 13 cells from seven mice; Mf-1 513 ± 34, n = 19 cells from six mice, P < 0.05), although the peak of the signals was not significantly different (WT 2.15 ± 0.25, n = 13 cells from seven mice; Mf-1 1.54 ± 0.27, n = 19 cells from six mice, P = 0.08), which resembles the case of LTD-inductive stimulation. In the stimulus protocol of depolarization only, which activates voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) in PCs, there was no difference in dendritic Ca2+ signals between WT (n = 15 from seven mice) and Mf-1 PCs (n = 19 from six mice) (Fig. 3C) (Ca2+ peak, WT 0.82 ± 0.17, Mf-1 0.61 ± 0.13, P = 0.34; Ca2+ integral, WT 644 ± 166, Mf-1 468 ± 89, P = 0.61; Ca2+ decay time, WT 318 ± 35, Mf-1 375 ± 32, P = 0.17). This suggests that VGCC-mediated dendritic Ca2+ signaling is not functionally affected in adult Mf-1 PCs. In the last stimulus pattern, PF burst stimulation, adult Mf-1 PCs showed significantly smaller dendritic Ca2+ signals than WT (Fig. 3D), although there was no significant difference in total PF EPSC amplitude between WT and MF-1 PCs (SI Methods). The peak, integral, and decay time of the Ca2+ signals in Mf-1 PCs (n = 19 from six mice) were all significantly lower than in WT (n = 15 from seven mice) (Fig. 3D2) (Ca2+ peak, WT 1.59 ± 0.23, Mf-1 0.97 ± 0.22, P < 0.05; Ca2+ integral, WT 1,569 ± 344, Mf-1 678 ± 153, P < 0.005; Ca2+ decay time, WT 664 ± 106, Mf-1 277 ± 32, P = 0.0005). PF burst stimulation evokes dendritic Ca2+ signals composed of VGCC-mediated Ca influx (because of AMPA receptor-mediated unclamped voltage change in PCs even under voltage clamp conditions) and mGluR1-mediated internal Ca2+ release from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in cerebellar PCs (22, 23). Considering the results of PC depolarization (Fig. 3C) showing no change in VGCC-mediated Ca2+ signals, these results imply that the reduction in PF burst-evoked Ca2+ signals in Mf-1 PCs may be caused by impairment in mGluR1-mediated Ca2+ release from ER. To examine this directly, PF burst-evoked mGluR1-mediated Ca2+ signals were recorded in the presence of 20 µM NBQX (an AMPA receptor blocker) (22, 24–26). Indeed, the mGluR1-mediated Ca2+ signals were significantly reduced in Mf-1 PCs (n = 7 from three mice) compared to WT (n = 6 from two mice) (SI Appendix, Fig. S6) (Ca2+ peak, WT 1.77 ± 0.27, Mf-1 0.46 ± 0.13, P < 0.005; Ca2+ integral, WT 1,491 ± 345, Mf-1 329 ± 138, P < 0.005). This result strongly suggests the impairment of mGluR1-mediated internal Ca2+ release in Mf-1 PCs. This conclusion is also supported by our data on mGluR-mediated synaptically evoked suppression of excitation (one form of short-term plasticity evoked by PF burst stimulation), which is dependent on mGluR1-mediated postsynaptic Ca2+ elevation at PF–PC synapses (27, 28). Synaptically evoked suppression of excitation was partially impaired, but not completely, in adult Mf-1 PCs (SI Appendix, Fig. S7).

It should be noted that the localization of mGluR1 was not altered in the cerebellum of adult Mf-1 mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S8A). There was no difference in the mRNA level of mGluR1 (gene name, Grm1) analyzed from the cerebellar tissue samples between WT and Mf-1 mice (relative mRNA values: WT 1.00 ± 0.16, n = 5; Mf-1 0.88 ± 0.16, n = 5; P = 0.62). Moreover, there was no difference between adult WT (n = 10 from eight mice) and Mf-1 PCs (n = 13 from nine mice) in the amplitude or the decay time of mGluR1-mediated slow EPSCs (amplitude, WT 365.3 ± 54.6 pA, Mf-1 307.4 ± 55.09, P = 0.38; half-decay time, WT 2,302 ± 454.6 ms, Mf-1 1760 ± 375.3 ms, P = 0.21), which we recorded by applying burst PF stimulation (25 pulses at 100 Hz, similar to SI Appendix, Fig. S7) in the presence of NBQX (20 µM) to block AMPA receptor-mediated fast EPSCs (SI Appendix, Fig. S8B). These results indicate that the mGluR signaling pathway independent of internal Ca2+ release is intact in adult Mf-1 PCs, because the previous study proved that mGluR-mediated slow EPSCs are functionally independent of mGluR-mediated Ca2+ signals in cerebellar PCs in terms of downstream effectors after mGluR1 activation (25).

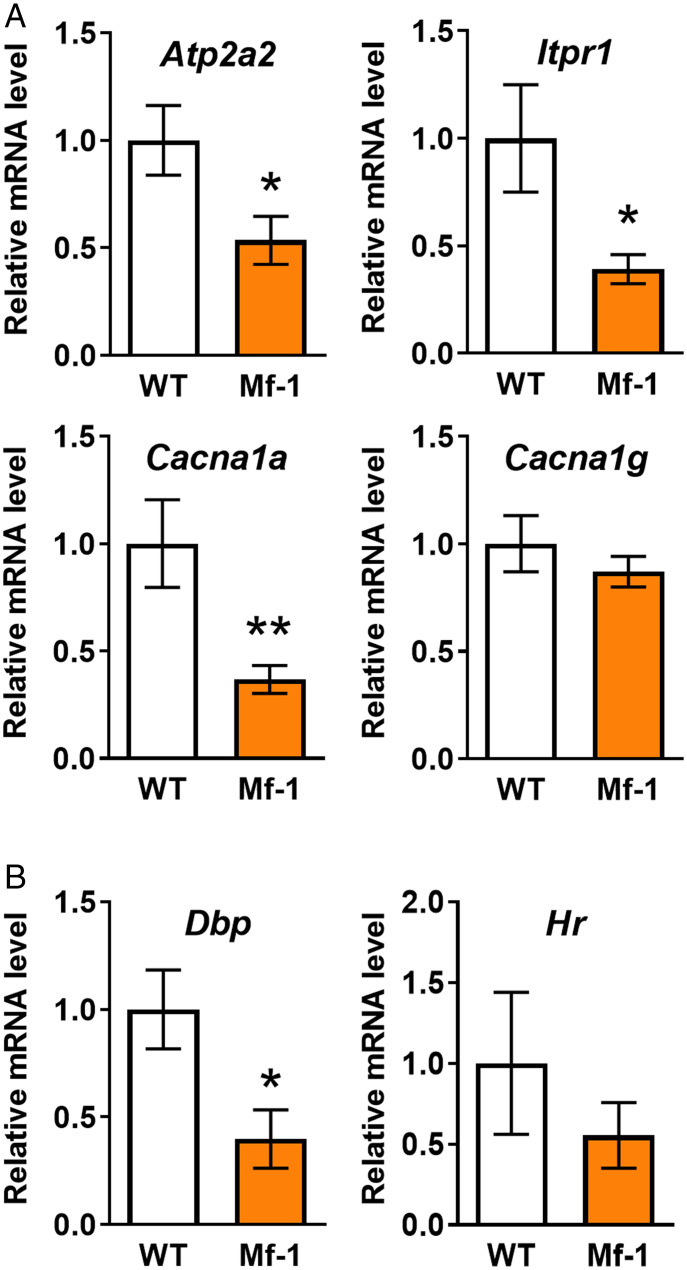

Single PC mRNA Analysis Revealed Down-Regulation of Proteins Related to Internal Ca2+ Release in Adult Mf-1 PCs.

The downstream of mGluR1-mediated signaling involves internal calcium release from the ER, and this response requires sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2 (SERCA2, gene name Atp2a2), which functions as a Ca2+ pump to load Ca2+ into the ER (29), and IP3R1 (gene name Itpr1), which acts as a Ca2+ release channel from the ER (30). On the other hand, in terms of Ca2+ dynamics, Ca2+ can enter PC dendrites from the extracellular space via VGCCs. The predominant VGCCs in PCs are P/Q-type (Cav2.1, gene name Cacna1a) and T-type (Cav3.1, gene name Cacna1g) (31–35). Thus, to determine why PF burst-evoked Ca2+ signals are reduced in adult Mf-1 PCs, we examined mRNA levels of these proteins quantitatively via RT-qPCR analysis at the single PC level by harvesting cytoplasm from a single PC by a patch pipette. The mRNA levels of Atp2a2, Itpr1, and Cacna1a were significantly decreased in adult Mf-1 PCs (Fig. 4A) (relative mRNA level: Atp2a2, WT 1.00 ± 0.16, n = 17 from six mice; Mf-1 0.54 ± 0.11, n = 12 from seven mice, P < 0.05; Itpr1, WT 1.00 ± 0.25, n = 13 from six mice, Mf-1 0.39 ± 0.07, n = 12 from seven mice, P < 0.05; Cacna1a, WT 1.00 ± 0.2, n = 13 from six mice, Mf-1 0.37 ± 0.06, n = 12 from seven mice, P < 0.05), and no change was observed in the mRNA levels of Cacna1g between WT and Mf-1 PCs (Fig. 4A) (WT 1.00 ± 0.13, n = 10 from six mice, Mf-1 0.87 ± 0.07, n = 11 from seven mice, P = 0.40). As control experiments, we also examined the mRNA levels of known TH-responsive genes, Dbp (encoding D site albumin promoter binding protein) and Hr (encoding Hairless) (36, 37). As expected, the expression of Dbp was significantly inhibited in adult Mf-1 PCs (Fig. 4B, Left) (WT 1.00 ± 0.18, n = 4 from four mice, Mf-1 0.40 ± 0.14, n = 4 from four mice, P = 0.04). The mRNA level of Hr tended to be lower in Mf-1 PCs, although there was no significant difference (Fig. 4B, Right) (WT 1.00 ± 0.44, n = 4 from four mice, Mf-1 0.55 ± 0.20, n = 4 from four mice, P = 0.41). Collectively, these results suggest that adult Mf-1 PCs have reduced expression of SERCA2 and IP3R1, which are both essential for mGluR1-mediated dendritic Ca2+ signals, leading to a reduction in PF burst-evoked Ca2+ signals in Mf-1 PCs.

Fig. 4.

The mRNA levels of Ca2+-related genes (Atp2a2, Itpr1, and Cacna1a) are down-regulated at the single PC level in adult Mf-1 mice. Single-cell RT-qPCR was conducted with cytoplasm collected from a single PC by a whole-cell patch clamp technique. All mRNA levels were first normalized to the one of Gapdh in each PC. For each gene, the relative mRNA level in Mf-1 mice was normalized to that in WT mice. (A) mRNA levels of Atp2a2 (encoding SERCA2), Itpr1 (encoding IP3R1), and Cacna1a (encoding Cav2.1) were significantly down-regulated in adult Mf-1 PCs. The mRNA level of Cacna1g (encoding Cav3.1) was comparable between WT mice and Mf-1 mice. (B) Pooled data of the mRNA levels of known TH target genes, Dbp and Hr. The mRNA level of Dbp was significantly reduced in adult Mf-1 PCs. There was no significant difference in that of Hr, although there was a tendency for a lower mRNA level of Hr in adult Mf-1 PCs. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Adult-Onset Inhibition of TH Signaling in PCs Does Not Affect LTD Induction nor mRNA Levels of Ca2+ Signal-Related Genes.

With our transgenic Mf-1 mouse model, it is still unclear whether the impairments in cerebellar function at adult stage are derived from the developmental period (i.e., functional developmental arrest) or caused by inhibition of TH signaling during the adulthood. To examine this issue, we generated another mouse model in which TH signaling is inhibited only at adult age in a PC-selective manner. Specifically, dominant-negative mutant TRs (GFP + Mf-1) were expressed at adult stage in WT mice via the adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector-mediated gene expression method under the control of the PC-specific L7 promoter in the experimental timeline shown in Fig. 5A. In addition, we had two more control conditions where only GFP (as a control for GFP overexpression) or normal TRs (GFP + hTRβ as a control for TR overexpression) were expressed specifically in PCs. Although gene expression levels in these conditions were reasonable and specific to PCs (SI Appendix, Fig. S9A), there was no major behavioral abnormality in all the experimental conditions 3 wk after the AAV vector injection (SI Appendix, Fig. S9B, horizontal ladder walking test, WT n = 10, GFP n = 8, GFP + hTRβ n = 7, GFP + Mf-1 n = 6; two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, gene expression effect, P = 0.089). The synaptic plasticity phenotypes evoked by LTD-inductive stimulation were intact in all these conditions (i.e., similar LTD phenotypes) (Fig. 5B, GFP 0.60 ± 0.01 normalized to baseline EPSC, n = 10 from five mice; GFP + hTRβ 0.61 ± 0.01 normalized to baseline EPSC, n = 10 from five mice; GFP + Mf-1 0.59 ± 0.03 normalized to baseline EPSC, n = 10 from five mice; Kruskal–Wallis test, P = 0.153). The mRNA levels of Ca2+ signal-related genes were not significantly different between these conditions in adult-onset AAV vector-mediated mouse models (Fig. 5C), in contrast to the data from congenital adult Mf-1 mice (Fig. 4). However, the single PC mRNA level of TH-responsive gene Dbp, but not Hr, was significantly decreased by adult-onset TH signaling inhibition (i.e., GFP + Mf-1 expression condition) (Fig. 5D, GFP n = 4, GFP + hTRβ n = 4, GFP + Mf-1 n = 4; multiple comparison test; GFP vs. GFP + Mf-1 P < 0.05, GFP + hTRβ vs. GFP + Mf-1 P < 0.01), which is consistent with the results of congenital Mf-1 mice model. These results suggest that although adult-onset AAV-mediated dominant-negative inhibition of TH signaling works effectively in cerebellar PCs, the inhibition does not affect long-term synaptic plasticity at PF–PC synapses or expression of Ca2+ signal-related molecules in PCs. Thus, we conclude that the abnormal phenotypes of congenital Mf-1 mice at adult stage (motor defects, LTP instead of LTD, reduced expression of IP3R1 and SERCA2) are developmentally arrested phenotypes and not determined at the adult stage.

Fig. 5.

Adult-onset inhibition of TH signaling in PCs has no effect on LTD or expression of Ca2+ signal-related genes. (A) Timeline of AAV-mediated gene expression experiments. Three different genes (GFP as a control of GFP expression, GFP + hTRβ as a control of TR expression, and GFP + Mf-1 for adult-onset inhibition of TH signaling in PCs) were expressed for the experiments. (B) Representative traces of PF EPSC before (dotted lines) and after (thick lines) LTD-inductive stimulation (Top), and pooled data of normalized PF EPSC amplitude (Bottom), shown similarly to Fig. 2. (C) The relative mRNA quantification of Ca2+ signal-related genes at the single PC level, performed similarly to Fig. 4. No significant difference in all tested genes between conditions. (D) Relative mRNA quantification of TH-responsive genes at the single PC level, performed similarly to Fig. 4. Dbp was down-regulated significantly, confirming that TH signaling is surely inhibited in adult cerebellar PCs by AAV-mediated expression of GFP + Mf-1 in adulthood. *GFP vs. GFP + Mf-1 P < 0.05, †GFP + hTRβ vs. GFP + Mf-1 P < 0.01.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that innate inhibition of TH signaling in cerebellar PCs causes motor defects and switches long-term synaptic plasticity from LTD to LTP at adult PF–PC synapses, although there is no major abnormality in morphology and basal electrophysiological properties of those synapses. When extracellular Ca2+ concentration was raised during the induction protocol, the LTD phenotype was rescued (i.e., LTP turned to LTD) in adult Mf-1 PCs, suggesting that the LTP phenotype in Mf-1 PCs is caused by reduced Ca2+ signals during the LTD-inductive stimulation. Our confocal Ca2+ imaging experiments revealed reduction in mGluR-mediated intracellular Ca2+ elevation evoked by PF burst stimulation in adult Mf-1 PCs. Quantitative mRNA expression analysis at single PC level shows that Ca2+ signal-related genes Atp2a2, Itpr1, and Cacna1a were down-regulated in adult Mf-1 PCs, suggesting that mGluR1-mediated IP3-induced Ca2+ release from ER is attenuated in adult Mf-1 PCs. These phenotypic changes were not observed under the adult-onset inhibition of TH signaling by AAV vector-mediated expression of dominant-negative TRs in adult WT PCs. Therefore, we conclude that the abnormal phenotypes at the adult stage in Mf-1 PCs is not caused by TH signaling deficiency during adulthood but may be determined at developmental stages.

Using our congenital PC-specific TH signaling-deficient Mf-1 mice line, we found adult behavioral defects such as impaired motor performance and motor learning deficit in Mf-1 mice. The impaired motor performance in this study may reflect not only motor coordination defects but also impaired body balance, depending on the type of motor tasks. However, the factors of motor coordination and body balance are practically quite hard to separate in mouse behavioral analysis. Regarding the mechanisms underlying the behavioral abnormalities, we focused on synaptic plasticity at PF–PC synapses in this study. However, in a dominant-negative mouse model of PC-selective hypothyroidism similar to our congenital Mf-1 mice, Fauquier et al. (15) reported reduced GAD65 (a GABA-synthetizing enzyme) immunoreactivity in the cerebellar molecular layer at young adult age, although they reported no functional data such as GABAergic synaptic responses or behavioral tests. In the present study, we did not examine inhibitory GABAergic synaptic transmission in the cerebellum of adult Mf-1 mice, and it remains to be elucidated whether unidentified abnormality in cerebellar inhibitory synaptic transmission might also contribute to the behavioral phenotypes of Mf-1 mice. However, we think that such a possibility may be unlikely, because mice with reduced or no GABAergic synapses in the molecular layer of the cerebellum have no abnormality in overall motor coordination, which is different from the phenotype of our congenital Mf-1 mice, although those GABAergic synapse-deficient mice exhibit impairment in motor learning (38, 39).

Switching from LTD to LTP in adult Mf-1 PCs and the rescue of LTD in the high-Ca2+ condition observed in this study are consistent with the inverse BCM rule for cerebellar LTD (20) and the leaky Ca2+ integral model for LTD (40). As indicated by the Ca2+ integral model, not only peak amplitude but also duration of the [Ca2+]i elevation in PC dendrites is a critical factor for LTD (40, 41). In congenital Mf-1 PCs, the reduction in Ca2+ signals was more prominent in terms of the duration of the signals (i.e., Ca2+ signal decay was faster, and consequently Ca2+ integral was smaller) than the peak amplitude (Fig. 3). These results emphasize the importance of duration of Ca2+ signals for determining the direction of synaptic plasticity (41). On the other hand, we may encounter a problem of Ca2+ indicator saturation, because we used a high-affinity Ca2+ indicator in our experiments to obtain robust and reliable signals. The mean Ca2+ peak values were lower in Mf-1 PCs, but there was no significant difference in Ca2+ peak between WT and Mf-1 PCs, especially in stronger stimulation protocols such as LTD-inductive stimulation and PF burst + depolarization (Fig. 3). This may be ascribed to underestimation of the true Ca2+ signal peak because of partial saturation of the indicator. The rescue of LTD in Mf-1 PCs in high-Ca2+ extracellular solution during LTD induction suggests that adult Mf-1 PCs have intact cellular machinery for establishing LTD downstream of Ca2+ signals to induce LTD. Recent studies have suggested that CaMKII plays a pivotal role in switching the direction of long-term plasticity (LTD or LTP) in PCs (17, 18). A shift of Ca2+ threshold for LTD is suggested to depend on phosphorylation of CaMKII (18). Another study has implicated that an extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)–based positive feedback loop in PCs triggers LTD after CaMKII activation and that this feedback loop is also dependent on the transsynaptic nitric oxide signaling pathway (17). These studies raise the possibility that not only Ca2+ dynamics but also the CaMKII-mediated feedback loop or ERK– and NO-mediated signaling cascades might also contribute to the switched phenotype from LTD to LTP in Mf-1 PCs. In fact, previous reports have shown that deletion of CaMKII converts LTD to LTP in PCs (42, 43), which resembles our results. It remains to be determined whether CaMKII-related signaling is affected in Mf-1 PCs.

Down-regulation of Cacna1a mRNA was observed in Mf-1 PCs, although we did not observe any alteration in depolarization-evoked dendritic Ca2+ signals. This indicates that VGCC-mediated Ca2+ signals are intact at the functional level in Mf-1 PCs because of abundant and redundant expression of P/Q-type VGCCs in PCs (33). On the other hand, the mRNA level of Cacna1g, another type of VGCC (Cav3.1, T type VGCC), was not changed in Mf-1 PCs. This reasonably explains that LTP induction in Mf-1 PCs is intact since Cav3.1 is essential for inducing PF–PC LTP independent of LTD (44).

Ca2+ signal caused by mGluR1- and IP3R1-mediated Ca2+ release from ER composes slow and delayed Ca2+ response at PF–PC synapses (22, 24), enabling sustained Ca2+ signals in response to repetitive PF activity. This type of Ca2+ signal also contributes to coincidence detection of cerebellar synaptic inputs and supralinear Ca2+ signaling in PCs (45). The present study shows reduced expression of Atp2a2 as well as Itpr1 in adult Mf-1 PCs. This alteration can cause reduction or depletion of Ca2+ stores in ER, and less Ca2+ release from ER via IP3R1, leading to failure to maintain repetitive Ca2+ elevation in response to PF burst activity. The Atp2a2 gene contains TREs in the promoter region, and thus its transcription is directly regulated by TH (46). Although TREs have not been identified in the promoter region of Itpr1 gene, the amount of its mRNA is thought to be regulated in a TH-dependent manner (47). In our previous studies using cerebellar tissues as mRNA samples, Itpr1 mRNA level in Mf-1 mice was decreased at developing stages (PD 7 and PD 15) in Mf-1 mice but was comparable to the one in WT mice later at the young adult stage (PD 30) (10), which is contradictory to the present study, where mRNA samples were obtained from single PCs. These could underscore the importance of cell type–specific analysis of TH effects on gene expression profiling, especially in the nervous system containing highly heterogeneous cell population.

Our congenital PC-specific TH signaling-deficient Mf-1 mice show distinct functional abnormalities such as motor impairment, disrupted mGluR-mediated Ca2+ signals, and LTD impairment in adulthood, although the mice have no overall morphological abnormality in the cerebellum or impairment in basal synaptic responses at PF–PC synapses. In this study, taking advantage of AAV vector-mediated PC-specific expression of dominant-negative TRs at adult stages, we could nail down the time window of TH action (developmental stage or adult stage) for the phenotypes in adulthood. Our study emphasizes the developmental effects of Mf-1 on adult cerebellar function. This is in line with the presence of a critical period of TH action during cerebellar development (48). In humans, without sufficient exposure of TH or its substitute during this period, children may display developmental abnormalities including motor deficits (3). Although we could not specify the critical time window of the PC-specific TH action during cerebellar development in this study, this issue should be examined in the future studies. It should be noted that our findings are related to functional maturation, not just morphological maturation in the adult cerebellum. In other words, this study shows that TH action during development can affect functional phenotypes much later at adult stage without obvious morphological abnormality. In that sense, our findings would add complex and elaborate aspects of TH actions on cerebellar functional development, and our study highlights the importance of functional analysis such as behavioral tests, electrophysiological recordings, and live imaging in studying TH effects on the nervous system.

The present study demonstrates a PC-specific developmental role of TH in determining the direction of synaptic plasticity in adulthood. Our findings indicate that motor deficits observed clinically in congenital hypothyroidism (3) might be a consequence of impaired LTD at PF–PC synapses. Our discoveries could give insight into the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying congenital hypothyroidism–induced dysfunctions of the nervous system, including the cerebellum.

Materials and Methods

The animal experimentation protocol in the present study was approved by the Animal Care and Experimentation Committee of Gunma University. All procedures for the care and treatment of animals were performed according to the Japanese Act on the Welfare and Management of Animals and the Guidelines for the Proper Conduct of Animal Experiments issued by the Science Council of Japan. The mice used in the present study were bred in the Animal Facility of Gunma University Graduate School of Medicine. The mice were kept at 24 ± 5 °C, 55 ± 5% relative humidity under a 12-h light–dark cycle (lights on, 7:00–19:00), with water and food ad libitum. As a control group, male WT clNJ/FVB mice were purchased from CLEA Japan, Inc. Mf-1 mice were generated as described before (10), with PC-specific expression of a mutant loss-of-function TRβ1, which binds to TREs but cannot bind to triiodothyronine. In Mf-1 mice, mutant loss-of-function TRs are coexpressed with endogenous WT TRs and thus function as dominant-negative TRs. By using Mf-1 mice, we can limit the manipulation of TH–TR binding deficiency to PCs. Since our previous findings indicate that only homozygous mutant mice (Tg/Tg) display motor defects, only Tg/Tg mice were used in the present study. Mating Tg/Tg genotypes enabled consistent generation of Tg/Tg mice. This was largely due to fertility of Tg/Tg dams being comparable to the fertility of WT dams and low lethality of the mutation. In each WT and Mf-1 group, adult male mice were used at PD ∼70 unless otherwise noted. Details of experimental procedures are described in SI Appendix, Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (grant nos. 18H03379 to N.K. and 20K06906 to N.H.) and by the program for Brain Mapping by Integrated Neurotechnologies for Disease Studies from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (grant JP20dm0207057/JP21dm0207111) to H.H. We thank Dr. W. Miyazaki and Dr. A. Haijima for technical support and the Gunma University Initiative for Advanced Research Viral Vector Core for producing AAV9 viral particles.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. C.I.D. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2210645119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information. All materials are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

- 1.Yen P. M., Physiological and molecular basis of thyroid hormone action. Physiol. Rev. 81, 1097–1142 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koibuchi N., Chin W. W., Thyroid hormone action and brain development. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 11, 123–128 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rastogi M. V., LaFranchi S. H., Congenital hypothyroidism. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 5, 17 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimokawa N., et al. , Altered cerebellum development and dopamine distribution in a rat genetic model with congenital hypothyroidism. J. Neuroendocrinol. 26, 164–175 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strait K. A., Zou L., Oppenheimer J. H., β 1 isoform-specific regulation of a triiodothyronine-induced gene during cerebellar development. Mol. Endocrinol. 6, 1874–1880 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koibuchi N., Yamaoka S., Chin W. W., Effect of altered thyroid status on neurotrophin gene expression during postnatal development of the mouse cerebellum. Thyroid 11, 205–210 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong H., et al. , Molecular insight into the effects of hypothyroidism on the developing cerebellum. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 330, 1182–1193 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato A., Koizumi Y., Kanno Y., Yamada T., Inhibitory effect of large doses of propylthiouracil and methimazole on an increase of thyroid radioiodine release in response to thyrotropin. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 152, 90–94 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito M., Cerebellar long-term depression: Characterization, signal transduction, and functional roles. Physiol. Rev. 81, 1143–1195 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu L., et al. , Aberrant cerebellar development of transgenic mice expressing dominant-negative thyroid hormone receptor in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Endocrinology 156, 1565–1576 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tada M., Nishizawa M., Onodera O., Roles of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in spinocerebellar ataxias. Neurochem. Int. 94, 1–8 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao Z., van Beugen B. J., De Zeeuw C. I., Distributed synergistic plasticity and cerebellar learning. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 619–635 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamont M. G., Weber J. T., The role of calcium in synaptic plasticity and motor learning in the cerebellar cortex. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36, 1153–1162 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuzaki M., Cerebellar LTD vs. motor learning-lessons learned from studying GluD2. Neural Netw. 47, 36–41 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fauquier T., et al. , Purkinje cells and Bergmann glia are primary targets of the TRα1 thyroid hormone receptor during mouse cerebellum postnatal development. Development 141, 166–175 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lev-Ram V., Wong S. T., Storm D. R., Tsien R. Y., A new form of cerebellar long-term potentiation is postsynaptic and depends on nitric oxide but not cAMP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 8389–8393 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallimore A. R., Kim T., Tanaka-Yamamoto K., De Schutter E., Switching on depression and potentiation in the cerebellum. Cell Rep. 22, 722–733 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piochon C., et al. , Calcium threshold shift enables frequency-independent control of plasticity by an instructive signal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 13221–13226 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitamura K., Kano M., Dendritic calcium signaling in cerebellar Purkinje cell. Neural Netw. 47, 11–17 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jörntell H., Hansel C., Synaptic memories upside down: Bidirectional plasticity at cerebellar parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapses. Neuron 52, 227–238 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coesmans M., Weber J. T., De Zeeuw C. I., Hansel C., Bidirectional parallel fiber plasticity in the cerebellum under climbing fiber control. Neuron 44, 691–700 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finch E. A., Augustine G. J., Local calcium signalling by inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate in Purkinje cell dendrites. Nature 396, 753–756 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eilers J., Augustine G. J., Konnerth A., Subthreshold synaptic Ca2+ signalling in fine dendrites and spines of cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Nature 373, 155–158 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takechi H., Eilers J., Konnerth A., A new class of synaptic response involving calcium release in dendritic spines. Nature 396, 757–760 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartmann J., et al. , TRPC3 channels are required for synaptic transmission and motor coordination. Neuron 59, 392–398 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shuvaev A. N., Hosoi N., Sato Y., Yanagihara D., Hirai H., Progressive impairment of cerebellar mGluR signalling and its therapeutic potential for cerebellar ataxia in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 model mice. J. Physiol. 595, 141–164 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Safo P. K., Cravatt B. F., Regehr W. G., Retrograde endocannabinoid signaling in the cerebellar cortex. Cerebellum 5, 134–145 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kano M., Hashimoto K., Tabata T., Type-1 metabotropic glutamate receptor in cerebellar Purkinje cells: A key molecule responsible for long-term depression, endocannabinoid signalling and synapse elimination. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 363, 2173–2186 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mata A. M., Sepúlveda M. R., Calcium pumps in the central nervous system. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 49, 398–405 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okubo Y., et al. , Visualization of Ca2+ filling mechanisms upon synaptic inputs in the endoplasmic reticulum of cerebellar Purkinje cells. J. Neurosci. 35, 15837–15846 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Llinás R., Sugimori M., Electrophysiological properties of in vitro Purkinje cell dendrites in mammalian cerebellar slices. J. Physiol. 305, 197–213 (1980). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westenbroek R. E., et al. , Immunochemical identification and subcellular distribution of the α 1A subunits of brain calcium channels. J. Neurosci. 15, 6403–6418 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Indriati D. W., et al. , Quantitative localization of Cav2.1 (P/Q-type) voltage-dependent calcium channels in Purkinje cells: Somatodendritic gradient and distinct somatic coclustering with calcium-activated potassium channels. J. Neurosci. 33, 3668–3678 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Talley E. M., et al. , Differential distribution of three members of a gene family encoding low voltage-activated (T-type) calcium channels. J. Neurosci. 19, 1895–1911 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isope P., Murphy T. H., Low threshold calcium currents in rat cerebellar Purkinje cell dendritic spines are mediated by T-type calcium channels. J. Physiol. 562, 257–269 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chatonnet F., Guyot R., Benoît G., Flamant F., Genome-wide analysis of thyroid hormone receptors shared and specific functions in neural cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E766–E775 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morte B., Gil-Ibañez P., Heuer H., Bernal J., Brain gene expression in systemic hypothyroidism and mouse models of MCT8 deficiency: The Mct8-Oatp1c1-Dio2 triad. Thyroid 31, 985–993 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wulff P., et al. , Synaptic inhibition of Purkinje cells mediates consolidation of vestibulo-cerebellar motor learning. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 1042–1049 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sergaki M. C., et al. , Compromised survival of cerebellar molecular layer interneurons lacking GDNF receptors GFRα1 or RET impairs normal cerebellar motor learning. Cell Rep. 19, 1977–1986 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka K., et al. , Ca2+ requirements for cerebellar long-term synaptic depression: Role for a postsynaptic leaky integrator. Neuron 54, 787–800 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Titley H. K., Kislin M., Simmons D. H., Wang S. S. H., Hansel C., Complex spike clusters and false-positive rejection in a cerebellar supervised learning rule. J. Physiol. 597, 4387–4406 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hansel C., et al. , alphaCaMKII is essential for cerebellar LTD and motor learning. Neuron 51, 835–843 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Woerden G. M., et al. , betaCaMKII controls the direction of plasticity at parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapses. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 823–825 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ly R., et al. , T-type channel blockade impairs long-term potentiation at the parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapse and cerebellar learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 20302–20307 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang S. S. H., Denk W., Häusser M., Coincidence detection in single dendritic spines mediated by calcium release. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 1266–1273 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zarain-Herzberg A., Alvarez-Fernández G., “The SERCA2 gene: Genomic organization and promoter characterization” in The Scientific World Journal (Springer, Boston, MA, 2003), pp. 479–496. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oppenheimer J. H., Schwartz H. L., Molecular basis of thyroid hormone-dependent brain development. Endocr. Rev. 18, 462–475 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ishii S., Amano I., Koibuchi N., The role of thyroid hormone in the regulation of cerebellar development. Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul) 36, 703–716 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information. All materials are available from the corresponding authors upon request.