Abstract

Prior studies analyzing patient experience with noninvasive ventilation (NIV) found the most impactful interaction that patients remembered was with nurses, however a survey of nurses regarding the management of patients treated with NIV has shown that most nurses felt unprepared to care for these sick patients. Our qualitative descriptive study explored current nursing experience using NIV as treatment for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD). Nine (n=9) subject matter expert nurses practicing in a variety of clinical settings participated in semi-structured interviews. The COREQ checklist was followed for interview development. Interview transcripts were subsequently analyzed using deductive thematic analysis. Themes identified from the interviews pertained to patient assessment, novice nurses need for clinical support, team communication and nursing education. Improving interprofessional team communication and collaboration skills, and implementing guidelines for NIV utilization were specified as essential components of NIV education for nurses. Even though the nursing role in the care of AECOPD NIV patient could be institution dependent, the themes presented in our study are useful in identifying opportunities for NIV nursing education and areas for further research.

Patient or Public Contribution. Nurses served as interviewees for this study.

Keywords: acute exacerbation of COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), noninvasive ventilation (NIV), nurse, rapid response team

INTRODUCTION

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) with bi-level positive airway pressure is commonly used to treat patients admitted to the hospital with acute hypercapnic respiratory failure secondary to an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) in accordance with clinical practice guidelines (Rochwerg et al., 2017). Data from several randomized controlled trials and metanalyses show that NIV is beneficial as a first-line intervention in conjunction with usual care for reducing the likelihood of mortality and endotracheal intubation in patients admitted with acute hypercapnic respiratory failure secondary to AECOPD (Osadnik et al., 2017). Prior studies suggest that efforts to increase NIV use in AECOPD need to account for the complex and interdisciplinary nature of NIV delivery and the need for team coordination (Stefan et al., 2021). Successful application of NIV and improved patient outcomes is facilitated by involvement of the entire multidisciplinary team including but not limited to physician, nurse and respiratory therapist. Nurses practicing in, but not limited to, emergency rooms, intensive care units, and intercare/stepdown units may be frequently involved in the care of the patient on NIV.

BACKGROUND

Nursing care of AECOPD NIV patients draws on knowledge of equipment, patient education, monitoring, trouble shooting, providing psychological support, and perhaps planning end of life (Preston, 2013). A recent human-centered design analysis exploring NIV patient experience (McCormick et al., 2022) found the most impactful interaction that patients remembered was with nurses. However, a survey of nurses regarding the management of patients treated with NIV has shown that most nurses felt unprepared to care for these sick patients (Roberts, 2021). Surveys completed by nurses working outside of an intensive care unit setting found that 67% of nurses felt ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ involved in the decision-making process of initiating NIV, half felt inadequately informed, and only 13% stated their NIV training was adequate (Cabrini et al., 2009). Concern for patient safety with regard to the application of NIV equipment by inexperienced nurses has also been expressed (Balfour, Coetzee, & Heynes, 2012). This sentiment is supported in a recent review paper which describes nursing NIV experiences including themes of limited nursing education, limited team communication, and lack of NIV guideline utilization across the nursing spectrum in regards to NIV use (Green & Bernoth, 2020).

Given this background, we aimed to explore current nursing experience using NIV for patients presenting with AECOPD by interviewing subject matter expert (SME) nurses in an academic tertiary medical center as part of a qualitative descriptive (Sandelowski, 2000) sub study of a National Institutes of Health (NIH) RO1 award to improve the uptake of NIV through interprofessional education. In this manuscript we present the main themes identified from these interviews. In addition, we demonstrate how these themes could be integrated into educational programs to improve nursing knowledge regarding appropriate use and management of NIV.

METHODS

Study setting

This study took place in a tertiary, academic hospital located in the Northeastern region of the United States which takes care of approximately 450 COPD patients per year. It was part of a larger study that recruited subject matter expert nurses, respiratory therapists, and physicians for the purpose of increasing the effective use of NIV to treat AECOPD. The University of Massachusetts Baystate Health Institutional Review Board deemed the study appropriate for a waiver of consent.

Recruitment

Subject matter expert nurses were recruited from the emergency department (ED), intercare/step down units and the rapid response team in order to gather information about their experience related to caring for patients experiencing AECOPD for which NIV was part of the treatment plan. Nurse managers of these respective units were asked to provide names of nurses considered to be experts or peer role models in caring for patients with AECOPD on NIV. Identified nurses were invited by email from members of the research team to participate in a 60-minute interview. We decided a priori to interview a total of nine registered nurses, including three ED nurses (EDRN), three intercare/step down floor nurses (FRN), and three rapid response team nurses (RRTRN). Crispen and Hoffman (2006), using findings from expert systems and cognitive task analysis, concluded that knowledge elicitation or task decomposition can be conducted with three individuals who qualify as genuine experts. Recruitment emails and a copy of the study information sheet were sent to potential participants by the members of the research team.

Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by two trained members of the research team (the principal investigator/hospitalist and the clinical research coordinator) to identify the nursing thought process applied in the care of patients experiencing AECOPD, specifically with attention to use of NIV as opposed to invasive mechanical ventilation. Interviews were 60 minutes in duration and occurred via video conference or telephone.

The COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) checklist (Supplementary materials S1) were followed in this study (Tong, Sainsbury & Craig, 2007). The interview guide went through several iterations prior to its use. Initially, questions were developed by members of the study team with expertise in internal medicine and pulmonary medicine. Subsequently, a member of the study team with expertise in human factors and qualitative approaches reviewed a draft of these questions. Finally, the interview guide was piloted with nurses to check for understanding. Questions were modified for better understanding, and content from several questions was consolidated and re-distributed to form better worded questions. Redundant wording was removed to improve flow of the questions during the interview. A patient scenario was added to simulate an actual patient situation. The final interview questionnaire consisted of 12 questions.

The interview guide included questions addressing basic demographic information and other characteristics of the interviewee such as nursing role, training, and years of experience. The scenario discussed in the interview involved a patient experiencing a severe AECOPD as defined by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines (GOLD report, 2021), namely an acute event characterized by a worsening of respiratory symptoms beyond normal day-to-day variations and leading to a change in medication. The following initial scenario was provided: The patient has severe COPD, is already receiving oxygen, bronchodilators, steroids, and antibiotics if needed, and is in respiratory distress. How do you decide if the patient should be placed on NIV and who do you contact? The nurses were asked to: (1) describe their step-by-step approach to assessing and deciding further action for the patient in severe respiratory distress such as advocating for a trial of NIV versus invasive mechanical ventilation and how they manage a patient on NIV, (2) identify cues or patterns overlooked by a novice nurse that could signal worsening respiratory distress and might require escalation of care, and (3) describe the level of support and collaboration experienced with professional colleagues including respiratory therapists and physicians. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, returned to interviewees for comment/correction, and de-identified for subsequent analysis.

Data analysis

Interview transcripts were reviewed alongside the recording for de-identification and accuracy. Two independent trained reviewers subsequently analyzed transcripts using deductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) which provides a flexible and pragmatic approach to collecting and analyzing narrative accounts in a rich and detailed way. Deductive thematic analysis adopts a framework approach which is applied when pre-interview, the researcher identifies issues to be investigated while maintaining flexibility to allow new themes to be uncovered. We followed the six-phase guide by Braun and Clarke (2006): (1) familiarization with data, (2) generation of initial code, (3) search for themes, (4) review of themes, (5) definition and names of themes, and (6) production of the report. Final analysis consisted of using selected extracts from the interviews and relating them back to research questions. The goal of this analysis was to identify themes that inform nursing decisions related to use of NIV as part of a treatment plan for patients hospitalized with AECOPD.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the nine interviewees including demographics and clinical experience are summarized in Table 1. Themes and subthemes identified from the nine SME interviews are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Interviewees

| All (n = 9) | ED (n = 3) | F (n = 3) | RRT (n = 3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Sex, Female n | 7 | 78 | 1 | 33 | 3 | 100 | 3 | 100 |

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Years in current position | 9.8 | 7.4 | 13 | 4.9 | 11.3 | 9.9 | 5 | 2.8 |

| Years of professional service | 19.6 | 9.6 | 14.3 | 3.7 | 18.7 | 12.5 | 25.7 | 6.6 |

Abbreviations:

ED emergency department registered nurse

F acute care floor registered nurse

M mean

RRT rapid response team registered nurse

SD standard deviation

TABLE 2.

Themes and Subthemes Identified from Subject Matter Nursing Expert Interviews

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Patient assessment | Respiratory status |

| Skin color, diaphoresis | |

| Ability to swallow, ability to protect airway with presence of gag reflex | |

| Mental status | |

| Position in bed | |

| Arterial blood gas, end tidal carbon dioxide | |

| Determine candidacy for NIV | |

| Novice nurses benefit from clinical support | Recognize early signs of deteriorating condition |

| Appreciate clinical significance of different types of breath sounds or breathing patterns | |

| Identifying patient anxiety in tolerating mask and NIV | |

| Knowing when to “push back” | |

| Knowing when to utilize real-time clinical support and rapid response team nurse colleagues | |

| Team communication | Involve nurses, respiratory therapists and physicians in decision-making |

| Involve patient in decision-making | |

| Involve palliative care and/or geriatric consultants in decision-making | |

| Nursing education | Opportunities for real-time bedside training and simulation |

| Availability of protocols for NIV delivery |

Four main themes were identified from the interviews:

Patient assessment to determine candidacy for NIV treatment involves a multi-system approach.

Novice nurses frequently benefit from real-time clinical support to assist with patient management decisions and to prevent compromise to patient safety.

Team communication among the patient, nurses, respiratory therapists, and physicians is critical to promoting an environment for a successful trial of NIV.

Multiple opportunities for nursing education and training about NIV and its application exist.

We subsequently provide excerpts from the interviews to support each theme.

(a). Patient assessment to determine candidacy for NIV treatment involves a multi-system approach.

Subject matter expert nurses unequivocally reported that determining candidacy for NIV involved a multi-system patient assessment with simultaneous input of subjective and objective information. Common subthemes or components of patient assessment included respiratory status, specifically, work of breathing, presence of intercostal retractions, rate and depth of breathing, paradoxical respirations, pursed lip breathing, breath sounds, capillary refill, oxygen saturation, and increasing supplemental oxygen requirement. Skin color, diaphoresis, ability to swallow, mental status, ability to protect the airway with presence of gag reflex, and position in the bed were other important cues. “I do a full assessment” (FRN1). Patients with trouble breathing could have that “look in their eye that they are scared and cannot breathe and might not be able to speak” (EDRN3). Several nurses mentioned patient position as an indicator of respiratory distress, specifically “tripoding”, “trying to sit up as high as they can”, “trying to climb out of bed” and “the bed may actually be a mess”.

Reviewing the medical record and having a good history was identified as an important part of a thorough nursing assessment. “A good history is a very good thing to have” (FRN1). Arterial blood gas results might be available to contribute information about the patient’s oxygenation and ventilatory status. End-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring was used as an indicator of ventilatory status in some hospital locations.

Determining candidacy for NIV is an important component of nursing patient assessment. A patient is “not a candidate for NIV if nausea or vomiting present, confused, ripping mask off unnecessarily because patient cannot be restrained” (FRN3). Mental status was identified as an important factor in determining candidacy for NIV. “The appropriate NIV patient has to be awake enough to take the mask off if necessary” (FRN2).

Unique elements of patient assessment were verbalized by emergency room, acute care floor, and rapid response team subject matter expert nurses. These components of patient assessment summarized in Table 3 could be used to modify NIV nursing education programs depending on the location and scope of nursing practice.

Table 3.

Unique Elements of Patient Assessment by Scope of Nursing Practice

| Acute care floor | Emergency department | Rapid response team |

|---|---|---|

| Focus on information gathering | Use of end tidal CO2 | Team communication particularly important |

| Report information off to others including respiratory therapy | Critical thinking regarding selection of NIV modality | Getting entire patient care team on the “same page” |

| Understand need for BiPAP to lower carbon dioxide level | Traffic director role = called to scene, briefed, survey, and direct flow of care |

Abbreviations:

BiPAP Bilevel positive airway pressure

CO2 Carbon dioxide

NIV Non-invasive ventilation

(b). Novice nurses frequently benefit from real-time clinical support to assist with patient management decisions and to prevent compromise to patient safety.

Subject matter expert nurses shared concern about novice nurses and their ability to recognize early signs of deteriorating condition. This may be because “new nurses are task oriented and trying to check things off a list” (EDRN1). Furthermore, a novice nurse might miss subtle clues that the patient was sicker than realized and had potential for rapid deterioration in respiratory status. “If the patient was very sleepy and is now waking up, that’s a good sign…if it goes the other way and the patient gets very sleepy and oxygen saturation goes down then that would be a concern” (FRN1). Limited prior patient care experience may result in “a new nurse or new resident missing the panic look in the eyes of the patient, the big picture of how the patient looks in bed and underestimating the work of breathing” (FRN3). Similarly, “a new nurse might not understand the fine line between a patient starting to relax when improving or tiring out on NIV” (EDRN3).

In our institution’s emergency department, after a novice nurse completes orientation, they are paired with a stronger more experienced nurse to ease transition to the new clinical role. There also is an identified pod leader who can oversee and step in as needed

“…by the time you get to be a pod lead …you should have an overview sense and be able to pick up on situations where someone might need you to step in, or someone might need you to support them”

(EDRN1).

Novice nurses might not know who to call when patient is deteriorating - hospitalist, pulmonologist, rapid response team nurse, respiratory therapist -, so pairing the novice nurse with a more experienced nurse will help activate the system.

Novice nurses might not have a good grasp of the clinical significance of different types of breath sounds or breathing patterns “…faint wheezes because they are super tight versus if they are wheezing a whole bunch, you know, they are starting to move some air” (EDRN3). Altered breathing patterns are “definitely unrecognized…like Cheyne-Stokes, agonal breathing and the occluded airway where the patient is belly breathing but not moving much air” (RRTRN1).

A novice nurse might look to a more experienced nursing colleague to determine how much of a role anxiety is playing in mask tolerance versus worsening of breathing pattern and respiratory status. Subject matter expert nurses identified this clinical scenario as an opportunity for assisting novice nurses in developing appropriate clinical judgment since administering Ativan for anxiety related to worsening respiratory status instead of mask intolerance could lead to further respiratory depression necessitating intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation in AECOPD. “As a new nurse it’s hard to know is it anxiety because of the mask or is it their actual breathing pattern” (FRN1).

Novice nurses might not “push back” when asked by a novice physician/resident to restrain a patient who is fighting NIV or pulling off the mask particularly if protocols are not in place that prohibit restraints in this scenario. “No restraints allowed! – doctors and new respiratory therapists may allow it” (FRN3).

Since NIV use was seen as a complex intervention, subject matter expert nurses reported utilization of rapid response team nurses to ensure safe patient care when novice nurses and travel nurses were assigned a patient on NIV for AECOPD. Reduced confidence in the care teams’ ability to keep the AECOPD patient on NIV safe outside of the medical intensive care unit may drive a decision to suggest invasive mechanical ventilation too early or unnecessarily. Thus, the subtheme of real-time clinical support for novice nurses to prevent compromise to patient safety and promote a successful trial of NIV was expressed. “I’ll page the doctor…I will page respiratory therapy to come to the bedside…I will let rapid response know when things don’t seem to be working” (FRN2).

(c). Team communication among the patient, nurses, respiratory therapists and physicians is critical to promoting an environment for a successful NIV trial.

Team communication among nurses, respiratory therapists and physicians is critical to promoting a successful trial of NIV, and the patient is an important member of the team.

Team communication in the emergency room was identified as a strength. The presence of the physician and respiratory therapist in the room with the AECOPD patient was felt to be a support, and communication was positive with regards to developing a plan of care.

“You are right in the room with the physician, respiratory therapy, all sort of talking it out at the same time and I feel like quite often, more often than not, it goes well, the communication is good, ideas are discussed and implemented”

(EDRN1).

“The end decision is usually made by the doctor…Our group of doctors are really, really good at listening” (EDRN2). To the contrary, team communication might be strained when an admitted patient has to wait in the ED for a floor bed but care has been transferred to the hospital medicine team.

“In the emergency department, the nurse is the point person for the care of the patient so it is important that the nurse is aware of what’s going on with the patient and whether or not to continue NIV, wean off or proceed to intubation. When awaiting floor transfer, the floor doctors tend to be not as insightful, i.e., available, as the emergency room doctors”

(EDRN3).

Getting rapid response team involved, consulting the medical intensive care unit, and involving the physician early were all strategies mentioned to optimize team communication throughout the NIV trial especially on the floors. “The RRT nurse is very good at organizing and facilitating escalation of care” (RRTRN2). Team communication on the floor was a strength between floor nurses and rapid response team nurses and was also facilitated by involving the physician and respiratory therapist. Dealing with a new resident physician at the bedside by calling rapid response team nurses for support, or reaching out to the attending physician to discuss a higher level of care were examples of methods to facilitate team communication between the nurse and physician caring for the NIV patient.

“The team approach is best because you get the information right then and there…the pulmonologist is always the better resource for those patients…respiratory therapy and rapid response team nurses are a great resource as well along with residents and their attending…try and get them all to come as soon as you see a problem”

(FRN1).

In addition, end-of-life and overall goals of care could best be determined by involving palliative care and/or geriatric consultants in conversations with patients, families and significant others. These conversations can be facilitated by nursing staff caring for the AECOPD patient on NIV.

“Saying how long someone can stay on noninvasive ventilation without a change in settings…what is the plan for this patient?… What’s the goal for this patient?… Having those conversations earlier on I think would be very beneficial especially with COPD patients who have a chronic diagnosis and it is just going to get worse and not going to get better”

(FRN2).

(d). Multiple opportunities for nursing education and training about NIV and its application exist.

Education was recognized as a mechanism that could facilitate team communication and functionality. To promote team communication and optimize patient care, “a physician might say to new nurse or an experienced nurse…this is what I am thinking…this is what you may see in the next couple of minutes” (EDRN1). Similarly, the rapid response team nurse frequently plays a role in fine tuning aspects of patient assessment and educating novice and floor nurses in real-time at the bedside. “We are looking for restless agitation as a potential sign of hypoxia” (RRTRN1). Alternatively, multiple opportunities for nursing education including continuing education about all aspects of NIV, particularly patient assessment, and NIV initiation and management were identified. “I don’t usually hear a provider say to a nurse, this is what I want you to look for” when monitoring a patient who presents in respiratory distress (EDRN1). It was reported that a novice nurse may not know how to check the mode of NIV, for example continuous positive airway pressure versus bi-level positive airway pressure. Sudden deterioration of the AECOPD patient prone to retain carbon dioxide may occur if a less than optimal modality of NIV is selected. “The nurse is responsible for the care of the patient so there should be no finger pointing, say to respiratory therapy, when a mistake is made” (EDRN3).

Subject matter expert nurses frequently mentioned that NIV protocols would be helpful. “Really specific guidelines about who to put on NIV, knowing when to give oral medications or sips of water, at what point does a sitter watch the patient” (FRN2). Making nurses aware that protocols are readily available for use is an important component of the education process. “We have several policies in place but not everyone knows where to find them so I let them know how to find the policy” (RRTRN3). Use of NIV in a simulation setting may be beneficial in helping the nurse understand set up of NIV in clinical practice since “more of a hands-on experience on what we should do with the machine” is needed (FRN2).

DISCUSSION

Noninvasive ventilation is a common treatment used not only in the management of patients presenting with AECOPD, but also in patients presenting with congestive heart failure exacerbation, obstructive sleep apnea, chest wall deformity, neuromuscular disorders, and more recently, COVID19. The role of nurses in supporting patients receiving NIV and their families/caretakers as part of an interprofessional team and in coordinating care has been identified in the literature. The themes identified in our qualitative descriptive study support previous findings that nursing care of patients receiving NIV is complex and includes knowledge of equipment, education of patients and families/caretakers, monitoring for significant changes in respiratory status, providing psychological support, and at times end-of-life planning (Preston, 2013; Barnes, 2007; Jarvis, 2006).

More recent work has investigated the reasoning and actions of experienced nurses caring for patients with NIV due to acute respiratory failure from COPD. Sorensen et al. (2013) conducted a qualitative descriptive study of the care and management of AECOPD patients on NIV by experienced intensive care nurses. Although the clinical venue is different than our study, Sorensen et al. (2013) described a “practical wisdom” exhibited by experienced nurses and attempted to understand how experienced nurses think and act when providing NIV care. The authors conclude that this “practical wisdom” may help optimize continuing professional development and educate junior nurses. These conclusions are similar to the opinions expressed by the subject matter experts in our study specifically regarding the need for continuing NIV education and real-time support for novice nurses. Green and Bernoth (2020) conducted an extensive review of research focused on nurses’ experiences of using NIV across a variety of healthcare settings. The authors report that while nurses play an integral role in the initiation and management of NIV, there is a paucity of evidence on the experiences of nurses in this role. Similar to the opinions expressed by the subject matter expert nurses interviewed in our study, difficulties with NIV use including limited education, communication, and variable guideline use were reported by Green and Bernoth (2020). Despite these obstacles, nurses were generally able to use NIV to provide positive patient outcomes, similar to what we found in our analysis.

Sorensen et al. (2013) reported that experienced nurses had a tendency to separate problematic situations into three interrelated components: (1) achieving a noninvasive adaptation, (2) ensuring effective ventilation, and (3) responding attentively to patients’ perceptions of NIV. Similarly in our study, all interviewed subject matter expert nurses describe a process of vigilance and thoughtful surveillance as a crucial component of assessment of the AECOPD patient. The patient assessment process described by subject matter expert nurses is complex and prioritizes work of breathing, mentation, and oxygenation/ventilation during the initial assessment when determining the appropriateness for NIV and during subsequent assessments of response to NIV. The assessment process requires the nurse to process multiple signs and symptoms at once and to intervene quickly to meet patient needs or when escalation of care is necessary.

Teamwork in healthcare is defined as a cohesive group with shared identity, clarity, interdependence, integration, and shared responsibility (Reeves et al., 2010). Ineffective teamwork and team communication in healthcare settings are associated with increased patient harm and sentinel events (Brennan et al., 1991; Kohn et al., 2000; Institute of Medicine, 2004; The Joint Commission, 2008). In our study, the theme of interprofessional team communication particularly between nurses and respiratory therapists was an important component of safely caring for the patient on NIV identified in the subject matter expert nurse interviews. Developing a plan of care at the bedside in real time as part of a collaborative discussion between nurses, respiratory therapists and physicians was thought to be the most effective way to manage a patient on NIV.

The identified subject matter expert themes of patient assessment, novice nurses benefit from clinical support, and team communication paved the way for recognition of the final theme of nursing education regarding NIV. No matter the scope of practice, that is ED, acute care floor or rapid response team, the nurse is the healthcare provider having the most impactful interactions at the bedside of the NIV patient for prolonged periods of time (McCormick et al., 2022). The case for providing education about NIV to nurses during the pre-professional and professional phases of their careers is supported by the finding that only 13% of nurses reported their NIV training was adequate (Cabrini et al., 2009). Furthermore, to ensure delivery of effective NIV to AECOPD patients, nurses need an established support structure, local protocols, and regular quality improvement audits that identify opportunities for continuing education (Annandale, 2010). To this end, we present several resources that we developed to support the educational component of a project supported by the National Institutes of Health to improve the utilization of NIV in patients with AECOPD.

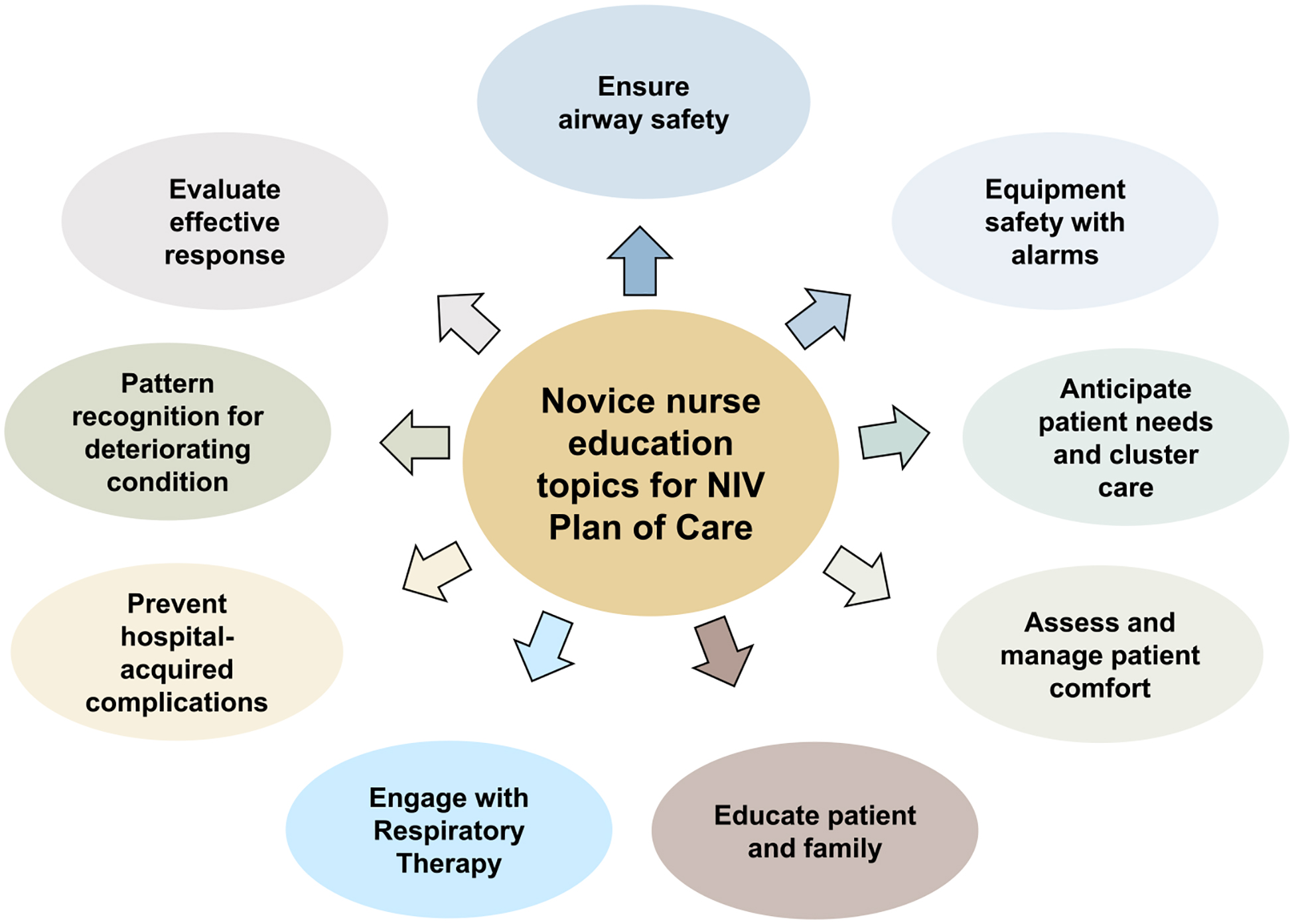

Education and practice resource development

An online module for nurses caring for patients on NIV (link available upon request) was created. This online module includes patient evaluation and safety, interprofessional team collaboration, and awareness of equipment safety, all essential components of nursing care for the NIV patient (Figure 1). Patient assessment is the foundation of AECOPD patient care. Using this theme from the subject matter expert nurse interviews, we created an algorithm that summarizes key signs, symptoms, and clinical decisions that serves as a useful resource for nurses caring for NIV patients (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Nursing education topics for noninvasive ventilation plan of care

Figure 2.

Assessing patient response to noninvasive ventilation treatment

Subject matter expert nurses expressed concern about novice nurses overlooking objective clues indicating clinical deterioration of the NIV patient. When asked what clues or patterns exhibited by patients with AECOPD on NIV might be missed by novice nurses, subject matter expert nurses verbalized concern that novice nurses caring for the AECOPD patient on NIV might not have the clinical acumen to consistently appreciate the significance of vital signs trends in the context of other fluctuating signs and symptoms. Novice nurses might find it challenging to synthesize simultaneous clinical cues depicting the “big picture” of the patient, as their critical thinking skills were in the early stages of development. In addition, subject matter expert nurses expressed concern about novice nurses’ ability to appreciate the subtleties of selecting the appropriate medication to improve NIV compliance, minimize anxiety, and understand the potential impact of medication choice on a patient’s ability to maintain a patent airway. The theme of novice nurses and potential clinical “misses” generated the idea of using pattern recognition of a cluster of clinical alerts to signify worsening respiratory distress (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pattern recognition for clinical deterioration of the patient on noninvasive ventilation

The availability of experienced nurses to assist less seasoned colleagues in caring for AECOPD patients on NIV was expressed throughout the interviews. Subject matter expert nurses considered novice nurses less likely to be prepared or experienced enough to perform high-level assessment skills at the bedside without assistance from a more experienced colleague, identifying the need for supportive nursing team communication and education. In our institution, rapid response team nurses are available to fill this gap outside of the intensive care unit. In addition, the majority of SME acute care and ED nurses identified the rapid response team nurse as a resource to support the escalation of care for patients experiencing AECOPD and potentially requiring NIV. Facilitating a higher level of care by the rapid response team nurse typically involves communicating with hospitalists, intensivists, critical care nursing colleagues, and respiratory therapists. We emphasize that there needs to be clarity of the role of rapid response team nurse in the rescue response that meshes with the culture of the organization. Our rapid response team nurses prefer the proactive versus reactive approach by rounding on floors with higher acuity patients and serving in a consultative role with an emphasis on mentorship and education through assisting floor nurses in the care of patients exhibiting signs and symptoms of potential clinical deterioration. All rapid response team nurses at our institution are baccalaureate prepared with at least three years of critical care experience, and are certified in critical care or emergency care with Advanced Cardiac Life Support training. We believe that rapid response team nurses supporting the bedside team is an essential component of successful outcomes in the treatment of AECOPD patients with NIV at our institution, although this needs to be substantiated by further research.

Identifying the roles and responsibilities of the nurse and respiratory therapist and setting the stage for collaborative practice is an important component in any educational program. Recognizing that these roles and responsibilities are institution specific, our educational program emphasizes the importance of interprofessional team communication by identifying unique characteristics of the role of the nurse and respiratory therapist in regards to set up of NIV, mask fitting, NIV settings, mental status assessment, medication selection and administration, and monitoring for improvement or deterioration in respiratory status.

Limitations

We recognize our findings are based on interview data and reflect the subjective views of the interviewees. Although we interviewed only nine nurses which could be considered a small sample, we made this decision a priori, based on recommendations for this type of analysis. The study was done in a tertiary care center with strong rapid response team support. The results may not be applicable to smaller non-teaching hospitals. Furthermore, our conclusions about the needs of novice nurses reflect only the opinions of the subject matter expert nurses. We did not interview less experienced nurses and therefore we could not speak to or summarize their perspective. However, several of the subject matter experts were educators in leadership positions where they had opportunities to understand the support a novice nurse needs in taking care of these sick patients. Further study is needed to understand nursing roles and educational needs pertaining to NIV use across a variety of institutional models. Furthermore, further study could investigate how more experienced nurses can best support novice nurses in the care of AECOPD and other critically ill patients.

CONCLUSION

By applying principles of deductive thematic analysis to interviews of subject matter expert nurses pertaining to care of the AECOPD patient on NIV, we identified the themes of patient assessment, novice nurses benefit from clinical support, team communication, and need for nursing education. We recognize that the nursing role in the care of AECOPD patient requiring NIV is dependent on institutional philosophy and scope of nursing practice. However, these themes are useful in identifying opportunities for NIV nursing education. Ultimately, this education should contribute to safer care of the AECOPD patient requiring NIV.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

National Institutes of Health; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 1RO1HL146615 (PI Mihaela Stefan)

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- Annandale J (2010). Using non-invasive ventilation on acute wards: how to provide an effective service. Nursing Times, 106 (26), 18–19. https://cdn.ps.emap.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2010/07/100706 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balfour L, Coetzee IM, & Heynes T (2012). Developing a clinical pathway for non-invasive ventilation. International Journal of Care Pathways, 16(4), 107–114. 10.1258/jicp.2012.012011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes D (2007). Non-invasive ventilation in COPD.2:Starting and monitoring NIV. Nursing Times, 103(40), 26–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp0630a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, Hebert L, Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Newhouse JP, Weiler PC, & Hiatt HH (1991). Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. The New England Journal of Medicine, 324(6), 370–376. 10.1056/NEJM199102073240604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrini L, Monti G, Villa M, Pischedda A, Masini L, Dedola E, Whelan L, Marazzi M, & Colombo S (2009). Non-invasive ventilation outside the Intensive Care Unit for acute respiratory failure: the perspective of the general ward nurses. Minerva anestesiologica, 75(7–8), 427–433. Epub 2008 Jan 24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispen P, & Hoffman R (2016). How many experts? International Electronics Engineers Intelligent Systems, 31(6), 56–62. 10.1109/MIS.2016.95 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green E, & Bernoth M (2020). The experiences of nurses using noninvasive ventilation: An integrative review of the literature. Australian Critical Care: Official Journal of the Confederation of Australian Critical Care Nurses, 33(6), 560–566. 10.1016/j.aucc.2020.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. (2021). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. https://goldcopd.org/2021-gold-reports

- Institute of Medicine. (2004). Keeping patients safe: Transforming the work environment of nurses. National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis H (2006). Exploring the evidence base of the use of non-invasive ventilation. British Journal of Nursing, 15(14), 756–759. 10.12968/bjon.2006.15.14.21576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system. National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick JL, Clark TA, Shea CM, Hess DR, Lindenauer PK, Hill NS, Allen CE, Farmer MS, Hughes AM, Steingrub JS, & Stefan MS (2022). Exploring the patient experience with noninvasive ventilation: A human-centered design analysis to inform planning for better tolerance. Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (Miami, Fla.), 9(1), 80–94. 10.15326/jcopdf.2021.0274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osadnik CR, Tee VS, Carson-Chahhoud KV, Picot J, Wedzicha JA, & Smith BJ (2017). Non-invasive ventilation for the management of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure due to exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 7(7), CD004104. 10.1002/14651858.CD004104.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston W (2013). The increasing use of non-invasive ventilation. Practice Nursing, 24 (3). 10.12968/pnur.2013.24.3.114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves S, Lewin S, Espin S, Zwarenstein M (2010). Interprofessional teamwork for health and social care. Oxford:Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A (2021). Understanding the principles of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation. Nursing Standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain): 1987), 10.7748/ns.2021.e11750. Advance online publication. 10.7748/ns.2021.e11750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochwerg B, Brochard L, Elliott MW, Hess D, Hill NS, Nava S, Navalesi P, Members Of The Steering Committee, Antonelli M, Brozek J, Conti G, Ferrer M, Guntupalli K, Jaber S, Keenan S, Mancebo J, Mehta S, & Raoof S, Members Of The Task Force (2017). Official ERS/ATS clinical practice guidelines: noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. The European Respiratory Journal, 50(2), 1602426. 10.1183/13993003.02426-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen D, Frederiksen K, Grofte T, & Lomborg K (2013). Practical wisdom: a qualitative study of the care and management of non-invasive ventilation patients by experienced intensive care nurses. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 29(3), 174–181. 10.1016/j.iccn.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan MS, Pekow PS, Shea CM, Hughes AM, Hill NS, Steingrub JS, Farmer MJ, Hess DR, Riska KL, Clark TA, & Lindenauer PK (2021). Update to the study protocol for an implementation-effectiveness trial comparing two education strategies for improving the uptake of noninvasive ventilation in patients with severe COPD exacerbation. Trials, 22(1), 926. 10.1186/s13063-021-05855-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission. (2008). Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. Sentinel Event Alert 40. Sentinel Event Alert 40: Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety | The Joint Commission [PubMed]

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, & Craig J (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.