Significance

Drug-resistant, community-associated lineages of Staphylococcus aureus have emerged in parallel around the world during the past 30 y. Phylodynamic modeling of outbreaks in human host populations and examination of well-recognized epidemic S. aureus lineages revealed periods of abrupt surges in transmission, which typically followed the acquisition of antimicrobial resistance and introduction into a new, often disadvantaged, local host population. Our data suggest that bacterial antimicrobial resistance, combined with changes in host epidemiology, may have facilitated the emergence of multiple community-associated S. aureus lineages in the late 20th century.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, community-associated MRSA, phylodynamics, effective reproduction number, emergence

Abstract

Community-associated, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) lineages have emerged in many geographically distinct regions around the world during the past 30 y. Here, we apply consistent phylodynamic methods across multiple community-associated MRSA lineages to describe and contrast their patterns of emergence and dissemination. We generated whole-genome sequencing data for the Australian sequence type (ST) ST93-MRSA-IV from remote communities in Far North Queensland and Papua New Guinea, and the Bengal Bay ST772-MRSA-V clone from metropolitan communities in Pakistan. Increases in the effective reproduction number (Re) and sustained transmission (Re > 1) coincided with spread of progenitor methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) in remote northern Australian populations, dissemination of the ST93-MRSA-IV genotype into population centers on the Australian East Coast, and subsequent importation into the highlands of Papua New Guinea and Far North Queensland. Applying the same phylodynamic methods to existing lineage datasets, we identified common signatures of epidemic growth in the emergence and epidemiological trajectory of community-associated S. aureus lineages from America, Asia, Australasia, and Europe. Surges in Re were observed at the divergence of antibiotic-resistant strains, coinciding with their establishment in regional population centers. Epidemic growth was also observed among drug-resistant MSSA clades in Africa and northern Australia. Our data suggest that the emergence of community-associated MRSA in the late 20th century was driven by a combination of antibiotic-resistant genotypes and host epidemiology, leading to abrupt changes in lineage-wide transmission dynamics and sustained transmission in regional population centers.

Staphylococcus aureus is an opportunistic pathogen that causes a variety of clinical manifestations, from superficial skin and soft-tissue infections to life-threatening systemic diseases, including bloodstream infections and necrotizing pneumonia (1). Treatment has been complicated by the rapid emergence of antibiotic resistance worldwide. In the past few decades, distinct S. aureus lineages, defined by multilocus sequence types (STs), have emerged in health care, community, and agricultural settings around the world (2–4). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) within some of these lineages has traditionally disseminated in hospitals, where acquisition of mutations and mobile genetic elements, such as the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec), promote persistence under high antibiotic selection pressure (5, 6). Since the 1990s, however, antibiotic-resistant, community-associated clones without epidemiological links to hospitals have emerged around the world, subsequently replacing other regionally prevailing lineages (4). Community-associated MRSA strains tend to be virulent, infect otherwise healthy people, and are frequently exported from the regions in which they emerged (6). While considered less resistant to antibiotics than health care–associated strains, evidence from multiple global and regional whole-genome datasets suggests that their emergence is associated with the acquisition of specific resistance mutations and mobile elements (7–15).

Epidemiological and genomic evidence for historical and ongoing circulation of methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) progenitor populations exists for nearly all community-associated lineages of interest (7–15). Strong contemporary evidence comes from the Australian lineage (ST93-MRSA-IV), whose ancestral MSSA strains continue to circulate among remote communities in the Northern Territory (NT) (12, 16). In addition, a symplesiomorphic clade of ST8-MSSA (meaning that strains retained their ancestral methicillin susceptibility, a symplesiomorphic trait) has been found circulating in Africa (10), having diverged prior to the emergence of the ancestral ST8-MSSA in Europe in the 19th century, from where it spread to the Americas and diverged into the ST8-USA300 (MRSA) sublineages in the 20th century (8, 11). Local circulation of progenitor MSSA strains in Romania is documented for the European ST1-MRSA sublineage (15, 17, 18). Emergence of ST80-MRSA in Europe has epidemiological connections to northern West Africa through importation of MSSA cases in French legionnaires (7, 19). While few ancestral strains have been sampled, ST772-MRSA-V is thought to have emerged from local MSSA populations in the Bengal Bay area, with the first isolates collected in Bangladesh and India, coinciding with the rise of a multidrug-resistant MRSA clade on the Indian subcontinent (13, 20). Even less is known about the origins of the ST59 clone, which produced a MRSA epidemic in Taiwan but had previously diverged into a (largely) MSSA sister clade in the United States (9).

Subsequent global dissemination of emergent MRSA clades has frequently been linked to travel and family history in their source region (7–15). For example, nearly 60% of isolates included from a global study on the dissemination of the ST772-MRSA-V clone had family contacts or travel history on the Indian subcontinent (13). However, to date, community strains tend to cause small outbreaks, consisting of local transmission chains and household clusters, but fail to become endemic in the community (10, 12, 13, 21–23). Some notable exceptions include several USA300 clades (ST8-MRSA-IV genotype) in Colombia, Gabon, and France, as well as the Australian lineage (ST93-MRSA-IV genotype), which established transmission in the Māori and Pacific Islander community in Auckland, New Zealand (NZ) (8, 10, 12). Additional evidence for successful recruitment (i.e., local circulation following transmission into a new host population) arises from molecular surveillance of ST80 and ST1, as well as from genomic surveillance of ST152-MSSA in the Middle East (7, 14, 15, 24).

The distinct regional distribution of community-associated lineages is observed in stark contrast to health care–associated strains that tend to spread rapidly in local health care systems, often following international dissemination (5, 25, 26). The evolutionary and epidemiological trajectory of community-associated lineages is currently not known, although indications are that the prevalence of some lineages and sublineages have declined over the decade, including the North American USA300 clade (27). However, in disadvantaged and remote communities, such as in northern Australia (28), community-associated MRSA rates are some of the highest in the country and have been increasing by approximately 4% per year, contrary to all other health care jurisdictions in Australia over the same period of time (29, 30). In addition, extremely remote populations in the Pacific Islands, such as in Papua New Guinea (PNG), which borders Australia in the Torres Strait, have reported outbreaks of community-associated osteomyelitis infections caused by S. aureus, but little is known about the extent of these outbreaks (31, 32).

While these data have contributed to a deeper understanding of community-associated lineage emergence, questions remain about the drivers behind these seemingly convergent events in the late 20th century. Increases in the effective population size (Ne) have been observed in some lineages, coinciding with the acquisition of antibiotic resistance, but these analyses have not been conducted for all relevant sequence types (7, 9, 14, 15). While historical and contemporary data on MSSA progenitor populations are limited in most lineages, we note that these populations tend to be geographically distinct, and that emergence of resistant genotypes occurs rapidly within industrialized host populations, such as on the Indian subcontinent (ST772), the Australian East Coast (AEC; ST93), in central Europe (ST1, ST80), and North America (ST8). In addition, it is not clear whether sustained transmission, characterized by an effective reproduction number (Re) exceeding a threshold value of 1 and remaining above that threshold for a period of time, has occurred following the emergence and transmission of community-associated strains, and whether drug-resistant strains are capable of becoming endemic following their exportation.

Bayesian phylodynamic methods have been extensively used in viral epidemics to infer key epidemiological parameters and changes in transmission dynamics from phylogenetic trees (33–35), allowing for simultaneous assessment of genomic and epidemiological changes in emerging pathogens. However, phylodynamic applications have been limited for bacterial datasets due to their relatively more complex genome evolution and lack of metadata and sufficient longitudinal isolate collections (36, 37). While there have been studies using birth–death skyline models to infer changes in Re for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (38, 39), no studies have so far, to our knowledge, have investigated how transmission changes in the emergence of S. aureus lineages.

Here, we investigate the genome evolution and transmission dynamics of emergent community-associated MRSA lineages using comparative phylodynamic methods to describe and contrast patterns of emergence and spread. We hypothesized that interactions between genomic and epidemiological factors create the conditions necessary for sustained transmission in the local environment and have contributed to the emergence of community-associated MRSA. We first examine the genomic epidemiology and transmission dynamics of community-associated S. aureus from the remote highlands of PNG and communities in northern Australia (Far North Queensland [FNQ]). Using additional samples of the Bengal Bay clone (ST772) from Pakistan (40) and global lineage-resolved sequence data (7, 9, 10, 12–15), we discover signatures in the effective reproduction number that suggest a combination of resistance acquisition and epidemic growth in populations centers as key drivers in the emergence of community-associated MRSA.

Results

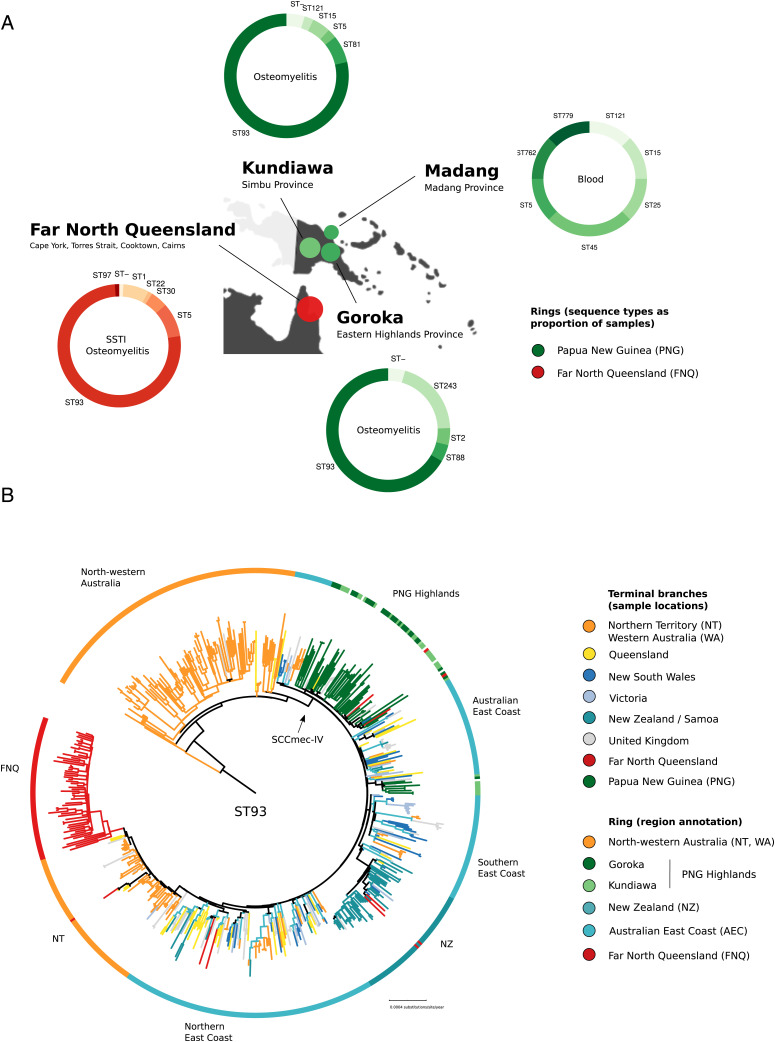

We sequenced 187 putative S. aureus isolates from remote PNG (2012 to 2018) and FNQ (including Torres and Cape and Cairns and Hinterland jurisdictions, 2019) using Illumina short reads (Fig. 1 and Dataset S1). Genotyping identified the Australian lineage (ST93-MRSA-IV) as the main outbreak sequence type in the highland towns of Kundiawa and Goroka (nKundiawa = 33 of 42; nGoroka = 30 of 35). The remaining isolates belonged to an assortment of sequence types (ST5, ST25, ST88); single-locus variants of ST1247 (n = 1) and ST93 (n = 2); coagulase-negative staphylococci, including S. lugdunensis (n = 1), S. delphini (n = 1), and Mammaliicoccus sciuri (n = 1); as well as a hospital cluster of invasive ST243 (clonal complex 30, n = 9) (Fig. 1A). FNQ isolates sampled in 2019 were largely identified as ST93-MRSA-IV (nFNQ = 68 of 91) on a background of various other lineages, including one infection with S. argenteus (Fig. 1A and Dataset S1).

Fig. 1.

Genomic epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus outbreak isolates from PNG (n = 95) and FNQ (n = 89). (A) Map of sampling locations, multilocus sequence types, and predominant symptoms of patients (ring annotation) (B) Global evolutionary history of the Australian lineage (ST93) showing the rooted ML phylogeny constructed from a nonrecombinant core-genome SNP alignment (n = 575) and major regional geographical structures in the evolutionary history of the clone. ST93 emerged in remote communities of north Western Australia and acquired SCCmec-IV, spreading to the AEC (blues, yellow), remote northern Australian communities (orange, red), the remote highlands of PNG (green), and into Auckland communities in NZ (sea green).

ST93-MRSA-IV strains from PNG and FNQ were contextualized within the global sequence diversity of the lineage (ST93, n = 444) to determine strain provenance using a maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogeny constructed from nonrecombinant, core-genome, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (n = 575; Fig. 1B). The resulting tree topology recapitulated our previous analysis of the lineage, confirming its origin from extant MSSA strains circulating in remote Indigenous communities of northwestern Australia (12). The main divergence event of ST93-MRSA on the AEC coincided with acquisition of SCCmec-IV (Fig. 1B). Isolates from PNG formed a major (n = 55) and minor (n = 8) clade in the ML tree, consisting of mixed strains from Goroka and Kundiawa (Fig. 1 A and B, green). The major clade contained sporadic isolates sampled in Queensland (QLD), FNQ, and New South Wales (NSW; n = 3) indicating regional transmission from PNG (Fig. 1B). The FNQ cluster derived from a NT clade that itself appears to have been a reintroduction of ST93-MRSA-IV from Australia's East Coast into the NT (Fig. 1B). Sporadic isolates sampled in FNQ were imported from other locations, including the North-Eastern ST93-MRSA-IV circulation, the NT, as well as NZ and PNG (red branches outside of FNQ cluster in Fig. 1B).

Regional Transmission Dynamics of ST93-MRSA-IV in Australia and PNG.

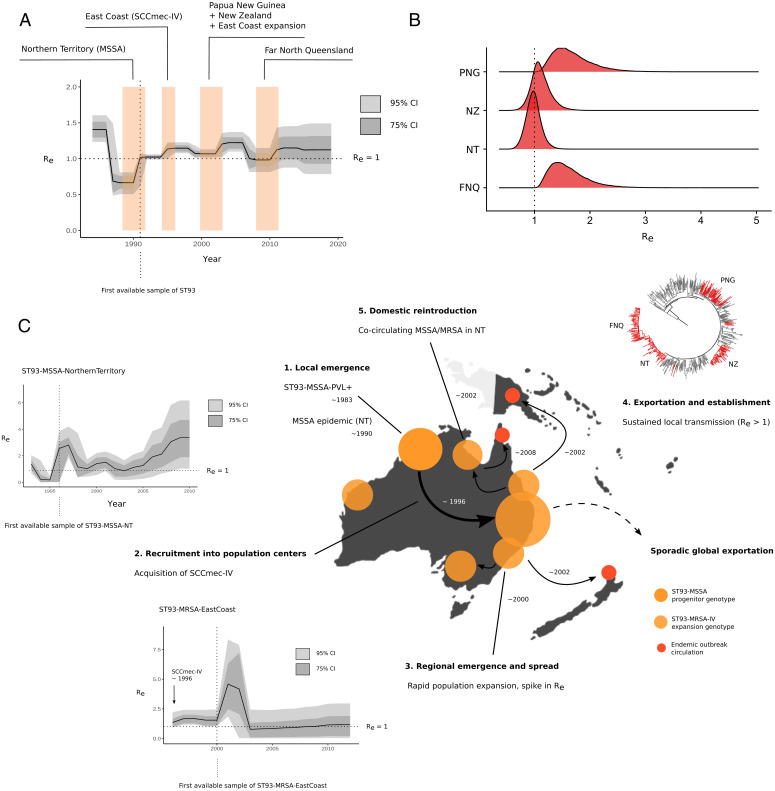

We next used fast ML methods (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S2) as well as Bayesian coalescent and birth–death skyline models for serially (i.e., PNG) and contemporaneously sampled isolates (i.e., FNQ) to infer time-scaled phylogenies and estimate epidemiological parameters for the ST93-MRSA-IV clone, including changes in Re and Ne over time (Fig. 2A and Table 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Lineage-wide transmission dynamics of the Australian clone ST93 indicate successive surges in Re at the divergence of extant MSSA strains in the NT, at acquisition of SCCmec-IVa and spread on the AEC, and upon recruitment into PNG, NZ, and FNQ communities (Fig. 2A). The clone became epidemic (Re > 1) soon after the emergence of an extant MSSA clade in the NT (most recent common ancestor [MRCA] = 1990; 95% credible interval, 1988 to 1992), coinciding with the first sample (1991) from the NT in our retrospective collection (Fig. 2A). When the clone was first described in southern QLD in 2000 (20), a resistant clade ST93-MRSA-IV had already established transmission in East Coast population centers (QLD, NSW, Victoria [VIC]) following the acquisition of SCCmec-IV around 1994 (95% credible interval, 1993 to 1995) (Figs. 1B and 2C). We estimate that the introduction of ST93-MRSA-IV into PNG occurred in the early 2000s (MRCA = 2000; 95% credible interval, 1998 to 2003, Fig. 2A), soon after establishment on the East Coast of Australia. In contrast, introduction of ST93-MRSA-IV into FNQ occurred more recently (MRCA = 2007; 95% credible interval, 2005 to 2009).

Fig. 2.

Phylodynamic signatures and parameter estimates for the Australian lineage (ST93) (A) Changes in Re over time, showing the 95% and 75% credible intervals (CIs) of the MRCA of clade-divergence events of ST93-MSSA and ST93-MRSA (colored blocks) using the birth–death skyline model. (B) Re posterior density distributions for introductions in PNG, FNQ, NZ, and reintroduction of the MRSA genotype to the NT. (C) Events in the emergence and regional dissemination of the QLD clone, with ML phylogenies and branch colors indicating major subclades and divergence events in the emergence of ST93. Vertical lines in skyline plots indicate the year of the first sample from the lineage or clade, horizontal lines indicate the epidemic threshold of Re = 1 (step 1). Local emergence of ST93-MSS in remote Indigenous communities of north Western Australia. Some sporadic transmission to QLD occurred in this clade. ST93-MSSA continues to circulate in the NT (NT). Step 2: Re > 1 estimates indicate that strains continue to spread (Inset Plot). Step 3: When the lineage acquired SCCmec-IV, it spread to East Australian coastal states (QLD, VIC, NSW) coinciding with population growth and increase in transmission with a spike at initial recruitment (Inset Plot). Step 4: ST93-MRSA-IV continues to spread in the eastern coastal states (QLD, NSW, VIC). Step 5: From the globally connected East Coast population centers, ST93-MRA-IV spread overseas (particularly to the United Kingdom) but also established sustained transmission in remote FNQ and regionally in the highlands of PNG. The FNQ outbreak is derived from an ST93-MRA-IV clade in the NT cocirculating with the ongoing ST772-MSSA epidemic.

Table 1.

Birth–death skyline median posterior estimates for global community-associated Staphylococcus aureus lineages and sublineages

| Sequence type | No. | MSSA | MRCA | 95% Credible interval | Re | 95% Credible interval | Clock rate* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST93 | 575 | 109 | 1983 | 1982 to 1983 | Δ | Figs. 2 and 4 | 7.50 × 10−7 |

| ST772 | 359 | 36 | 1970 | 1965 to 1975 | Δ | Figs. 3 and 4 | 1.04 × 10−6 |

| ST80 | 215 | 23 | 1977 | 1974 to 1979 | Δ | Fig. 4 | 7.91 × 10−7 |

| ST8 | 207 | 64 | 1860 | 1849 to 1871 | Δ | Fig. 4 | 6.31 × 10−7 |

| ST1 | 190 | 10 | 1987 | 1985 to 1989 | Δ | Fig. 4 | 1.19 × 10−6 |

| ST59 | 154 | 32 | 1958 | 1952 to 1964 | Δ | Fig. 4 | 9.43 × 10−7 |

| ST152 | 117 | 61 | 1958 | 1947 to 1962 | Δ | Fig. 4 | 5.93 × 10−7 |

| MRSA sublineages | |||||||

| ST93-MRSA-EastCoast | 278 | 2 | 1994 | 1993 to 1995 | 1.57 | 1.11 to 2.29 | fixed |

| ST93-MRSA-FNQ | 61 | 0 | 2007 | 2005 to 2009 | 1.55 | 1.08 to 2.27 | fixed |

| ST93-MRSA-PNG | 65 | 3 | 2000 | 1998 to 2003 | 1.61 | 1.13 to 2.40 | fixed |

| ST93-MRSA-NT | 62 | 1 | 1999 | 1998 to 2001 | 0.97 | 0.72 to 1.25 | fixed |

| ST93-MRSA-NZ | 51 | 1 | 2002 | 2000 to 2003 | 1.09 | 0.79 to 1.48 | fixed |

| ST772-MRSA-Pakistan | 25 | 0 | 1989 | 2000 to 2003 | 1.36 | 1.08 to 1.79 | fixed |

| ST152-MRSA-Europe | 53 | 0 | 1989 | 1986 to 1991 | 1.47 | 1.07 to 2.12 | fixed |

| ST8-USA300-NAE | 73 | 3 | 1983 | 1979 to 1986 | 1.60 | 1.13 to 2.36 | fixed |

| ST8-USA300-SAE | 32 | 0 | 1978 | 1973 to 1982 | 1.56 | 1.10 to 2.31 | fixed |

| ST8-USA300-Gabon | 17 | 0 | 1993 | 1991 to 1995 | 1.58 | 1.11 to 2.34 | fixed |

| ST59-MRSA-Taiwan | 87 | 2 | 1979 | 1976 to 1981 | 1.46 | 1.07 to 2.11 | fixed |

| MSSA sublineages | |||||||

| ST93-MSSA-NT | 96 | 84 | 1990 | 1988 to 1992 | 1.54 | 1.09 to 2.25 | fixed |

| ST8-MSSA-WestAfrica | 23 | 21 | 1979 | 1975 to 1982 | 1.54 | 1.09 to 2.26 | fixed |

| ST152-MSSA-WestAfrica | 42 | 40 | 1975 | 1972 to 1978 | 1.55 | 1.10 to 2.25 | fixed |

*Sublineage clock rates fixed at lineage-wide estimated median. Δ, estimated changes in lineage-wide Re; NAE, North American Epidemic; SAE, South American Epidemic.

Birth–death skyline models with fixed lineage-wide substitution rates were additionally applied to regional sublineages and clades of ST93, including the introductions into PNG, FNQ, NZ, and the reintroduction into the NT (Fig. 2B and Table 1). We observed sustained transmission in PNG (Re = 1.61; 95% credible interval, 1.13 to 2.40) and FNQ (Re = 1.55; 95% credible interval, 1.08 to 2.44). Sustained transmission may have occurred in the NT reintroduction of the MRSA-IV genotype (Re = 0.97; 95% credible interval, 0.72 to 1.25) and the Auckland community cluster (Re = 1.09; 95% credible interval, 0.79 to 1.48). Infectious periods (the time from acquisition to death or sampling of the strain) were estimated on the order of several years for strains from NZ (3.72 y; 95% credible interval, 1.12 to 6.10), NT (2.29 y; 95% credible interval, 0.97 to 3.41), PNG (2.21 y; 95% credible interval, 0.49 to 5.08, and FNQ (1.06 y; 95% credible interval, 0.19 to 2.58) (SI Appendix, Table S1 and Fig. S1). As we had sufficient sample sizes for these subclades (nNT= 96; nAEC = 278), we applied the birth–death skyline to each clade individually, allowing us to model clade-specific changes in Re over time (Fig. 2 C, Insets) as well as using the clade-specific method with fixed lineage-wide clock rates (Table 1). This produced estimates for the duration of the infectious period consistent with the credible intervals of the outbreak subclades (NT MSSA, 1.79 y, 95% credible interval, 0.77 to 3.76; AEC, 1.38 y, 95% credible interval, 0.47 to 4.86) (SI Appendix, Table S1). Stable circulation (Re ∼ 1) on the AEC was observed following a notable spike in Re shortly after acquisition of SCCmec-IV in the MRCA of the clade (Fig. 2C). In contrast, Re of ST93-MSSA in the NT has been increasing since approximately 2003, with credible intervals of Re > 1 suggesting sustained transmission until at least 2011. More recent genomic data on the spread of ST93-MSSA were not available.

Epidemic Community Transmission of ST772-MRSA-V in Pakistan.

We next investigated whether clade-specific signatures of epidemic growth (Re > 1) could be found in other community-associated MRSA lineages. We had previously reconstructed the detailed (n = 355) evolutionary history of the ST772-MRSA-V clone (13), which acquired multiple resistance elements and emerged in the last two decades on the Indian subcontinent, where it has a become a dominant community-associated lineage. No other genomic samples were available from these countries with the exception of unreleased ST772-A samples from India (41) and a macaque-associated environmental MRSA isolate from Nepal (42). We sequenced an additional 59 strains of ST772 from community and hospital sources in the population centers of Rawalpindi and Haripur in Pakistan (40), as well as some strains imported into a university hospital in Norway (23) (Fig. 3). We found that ST772 was exported into Pakistan on multiple occasions from the background population on the Indian subcontinent (Fig. 3); our sample contained several smaller transmission clusters (n < 8), in line with observations of community spread following international transmission (Fig. 3A). In addition, a larger transmission cluster (n = 25) was established shortly after fixation of SCCmec-V (5C2) (2002; 95% credible interval, 2000 to 2003) in the emergent clade ST772-A2 (Fig. 3A). Application of the birth–death skyline model on the lineage revealed changes in effective reproduction numbers similar to those observed in ST93-MRSA-IV (Fig. 3B). Instead of several pronounced spikes of the reproduction number, its epidemic phase was characterized by a monotonic rise in Re coinciding with the acquisition of a multidrug resistance–encoding integrated plasmid (blaZ-aphA3-msrA-mphC-bcrAB) around 1995 (95% credible interval, 1992 to 1996). Following a switch in fluoroquinolone-resistance mutations in grlA and fixation of the SCCmec-V (5C2) variant shortly after its emergence on the Indian subcontinent (1998, 95% credible interval, 1996 to 1999), a smaller increase in the reproduction number occurred with a delay of several years (Fig. 3B). Estimates for Re in the Pakistan cluster suggest that importation resulted in epidemic transmission (Re = 1.36; 95% credible interval, 1.08 to 1.79). Mirroring the emergence of drug-resistant ST93-MRSA on the AEC, ST772-MRSA emerged in population centers on the Indian subcontinent from a currently unknown MSSA progenitor population and was able to establish epidemic transmission after importation into Pakistan (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Genomic epidemiology of ST772 on the Indian subcontinent. (A) Rooted ML phylogeny of ST772 showing new strains (n = 59) from community transmission in Haripur and Rawalpindi (Islamabad metropolitan area). Sporadic importation into Pakistan is evident from singular and small transmission clusters, including a larger community-transmission cluster in Rawalpindi (n = 25; PAK), where table eggs were associated with the community outbreak and indicated additional spread overseas. (B) Re over time showing the 95% and 75% credible intervals (CIs). Acquisition of an integrated, multidrug-resistance (MDR) plasmid (MRCA 95% CI; purple) is associated with lineage-wide epidemic spread (Re > 1). Subsequent rapid fixation of the SCCmec-V (5C2) within a couple of years indicates a delayed effect on Re increasing slightly after the variant cassette fixation. (C, step 1) Events in the emergence of drug-resistant ST772-MRSA on the Indian subcontinent; branch colors in ML phylogenies show major subclades and ongoing transmission in Pakistan. Step 2: Local emergence of ST772-MSSA-PVL+ in the Bengal Bay area (first samples Bangladesh and India, 2004). Step 3: Acquisition and chromosomal integration of an MDR plasmid encoding blaZ-aphA3-msrA-mphC-bcrAB producing a ST772-MSSA-MDR clade, which experiences multiple introgressions of SCCmec-V variants (5C2 and 5C2&2). This genotype successfully spreads in the wider population of the Indian subcontinent. Eventually the shorter variant SCCmec-V-5C2 becomes fixed in the population. Step 4: Meanwhile the pathogen population grows on the Indian subcontinent, transmission is increasing and becomes sustained (Re > 1); sporadic exportation from the subcontinent is occurring including into Pakistan, where a community outbreak establishes sustained transmission. NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; UK, United Kingdom.

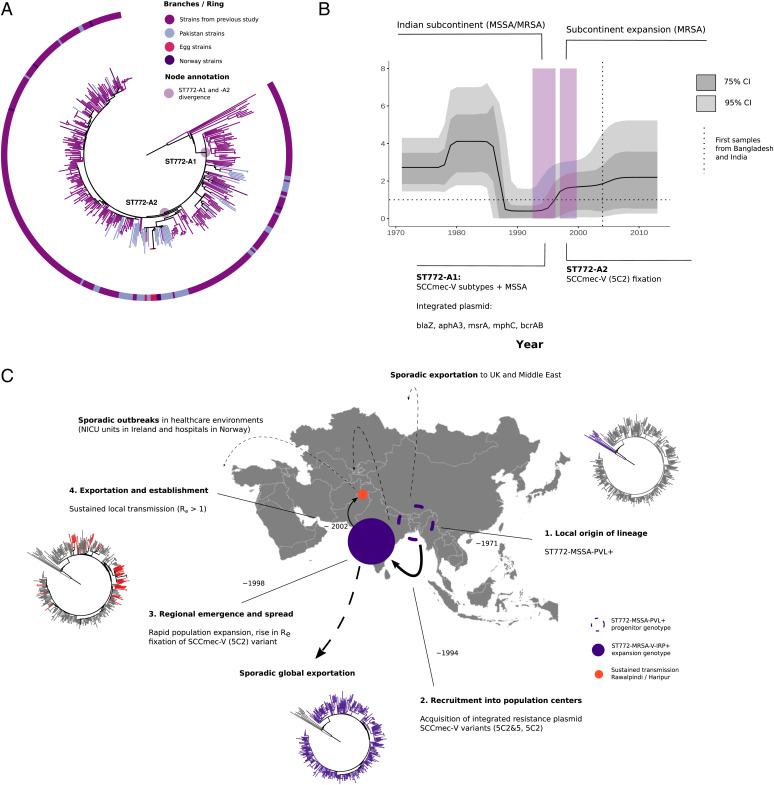

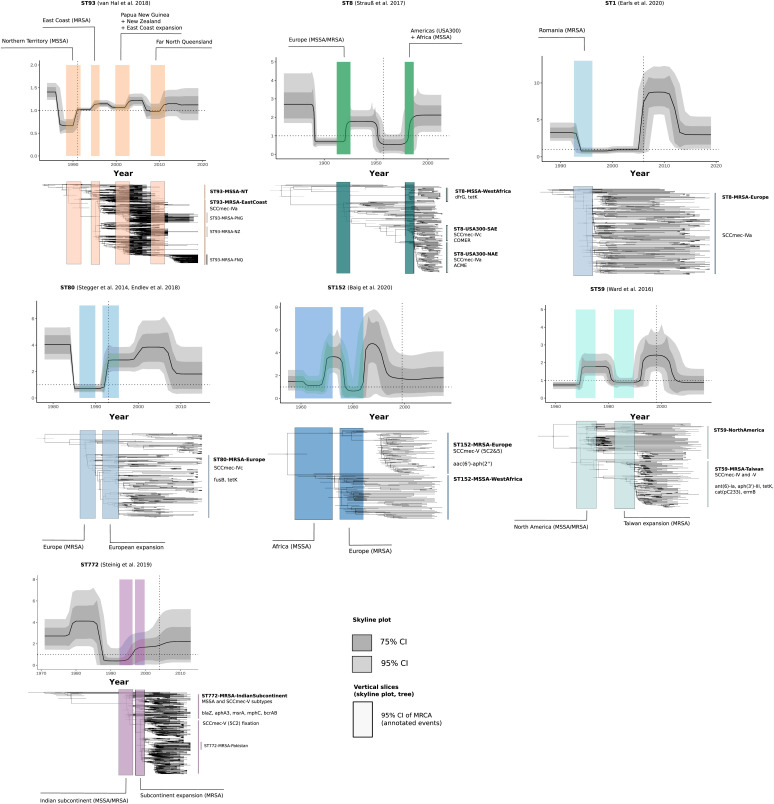

Global Emergence and Trajectory of Community-Associated S. aureus.

We next applied the birth–death skyline model to other community-associated MRSA clones, accounting for major lineages that have become dominant community lineages regionally and for which lineage-resolved genomic data were available (n > 100; Fig. 4 and Datasets S2 and S3) (7, 9, 10, 12–15). Short-read sequence data with dates and locations from previous genomic lineage analyses were collected from studies published on the emergence of ST1 (n = 190), ST152 (n = 139), and ST80 (n = 217) in Europe, the US–Taiwan clone ST59 (n = 154), and the European–American ST8 (n = 210, excluding isolates available as assemblies only. Multiple sequence types (ST152, ST8, ST80) included extant MSSA populations circulating in Africa (Table 1 and Dataset S3). Our analysis confirmed signatures of epidemic growth across these lineages, including notable increases in Re following genomic changes and recruitment into regional host populations (Central Europe, North America, AEC, India, Taiwan), as well as increases in Ne noted in previous investigations, coinciding with increases of Re (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). MRCAs of antibiotic-resistant clades (Datasets S4 and S5) in all MSSA and MRSA sublineages were estimated with 95% credible interval lower bounds between 1972 and 2005, and upper bounds between 1978 and 2009, confirming the seemingly convergent global emergence of resistant community strains in the late 20th century (Table 1). Low estimated sampling proportions suggest that ST8 and ST93 are widespread, consistent with global and regional epidemiological data of these clones; there was less certainty in the predictions for the recently emerged ST1, ST772, and ST152 (SI Appendix, Table S1). High posterior estimates of sampling proportion (ρ) in ST80 further suggest that the lineage is in decline in European host populations, although reports indicate potential ongoing circulation in the Middle East (43). Overall, median infectious periods varied between lineages, with the shortest estimates of several months for ST93 and the longest estimates exceeding 10 y in several lineages (SI Appendix, Table S1).

Fig. 4.

Bayesian phylogenetic trees and changes in the Re of global community-associated Staphylococcus aureus lineages with sufficient (n > 100) genotype-resolved data included in this study. Changes in Re estimated over equally sliced intervals in the birth–death skyline model are shown in the skyline plots. Trajectories of Re show the median posterior estimates over time (dark line) and their 95% credible intervals (dark gray) and 75% credible intervals (light gray). Colored rectangles show the 95% credible interval of the MRCA of clade divergences or demographic events (annotation) and are linked to time-scaled Bayesian maximum credibility trees beneath the plots. Location of the rectangles in the trees is aligned with the 95% credible intervals of node dates. Trees and rectangles were scaled and aligned manually to show their association with the skyline plots. Important sublineages and clades, as well as AMR elements or genes and mobile elements (COMER, ACME) associated with clade emergence are highlighted to the Right of the trees.

Considerable changes in Re occurred in the ancestral ST8-MSSA genotype at the emergence in European populations in the 19th century, which has been associated with the capsule mutation cap5D (1860; 95% credible interval, 1849 to 1871) (Fig. 4) (10). The proto community-associated clone then spread to the Americas and acquired SCCmec-IV variants as well as the canonical copper and mercury resistance element (COMER) and arginine catabolic mobile element (ACME) at the divergence of two regionally distinct epidemics across North America and parts of South America (8, 11, 44), which are notable as a combined increase in Re in the second half of the 20th century (Fig. 4). While data were sparse for ST59-MSSA strains (9), elevated reproduction numbers indicate that it became epidemic in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s, followed by the emergence of a resistance-enriched MRSA clade in Taiwan in the late 1970s and its expansion in the 1990s, with a delay between the MRCA of resistant strains and the epidemic in Taiwan several years later (Fig. 4 and Table 1). Similar delays occurred in European clones ST80-MRSA and ST1-MRSA, which also shared high estimates for their infectious periods (>10 y). We suspect that ancestral strains circulated for several years in local subpopulations before their emergence across Europe in the 1990s (ST80) and 2000s (ST1). but a weak temporal signal may contribute to a high degree of uncertainty in ST1 (see the 95% credible intervals in SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Similar to the minor increase in Re of ST772 after acquisition of the SCCmec-V (5C2) variant, a second increase in Re without notable genomic changes was observed in ST80, suggesting a second shift in transmission dynamics as the MRSA genotype spread across Europe in the early 2000s (Fig. 4). We observed the steepest spikes of reproduction numbers in clones recruiting into European countries (i.e., ST1, ST152) where spikes of Re > 5 to 8 were observed after initial recruitment into the host population, albeit with large confidence intervals (Fig. 4). Re estimates of West African subclades indicated epidemic spread in symplesiomorphic MSSA (ST8-MSSA Re = 1.54, 95% credible interval, 1.09 to 2.26; ST152-MSSA Re = 1.55, 95% credible interval, 1.10 to 2.25) and an introduction of USA300 (MRSA) in Gabon (ST8-MRSA-Gabon, Re = 1.58; 95% credible interval, 1.11 to 2.34). MSSA clades had acquired mild beta-lactam and other antibiotic-resistance determinants before their regional spread, including notable enrichment of blaZ and fosD (23/23) in ST8-MSSA-WestAfrica, blaZ (40/42) in ST152-MSSA-WestAfrica, and blaZ (94/96) in ST93-MSSA-Australia (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). However, ST8-MSSA-WestAfrica was the only MSSA clade that showed a strong association between divergence and acquisition of trimethoprim (dfrG) and tetracycline resistance (tetK) (SI Appendix, Fig. S9).

Discussion

In this study, we found a pattern in the emergence of community clones (n = 1,843) associated with the acquisition of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) determinants, which coincide with changes in host–pathogen transmission dynamics (increases in Re) and population-size expansions (Ne) upon introduction into regional population centers in the 1990s. Increases in Re exceeding the epidemic threshold (Re > 1) were closely associated with the acquisition of resistance in community-associated strains circulating in specific host subpopulations. AMR acquisition was followed by emergence and sustained transmission of antibiotic-resistant clades in regional population centers, such as the AEC (ST93), Taiwan (ST59), the Indian subcontinent (ST772), and central Europe (ST1, ST80, ST152). Our data suggest that the acquisition of multiple locality-specific resistance mutations and mobile genetic elements has driven rapid genotype expansions with notable increases in Re observed across lineage-wide and clade-specific analyses (Figs. 2–4). SCCmec-elements of type IV and V eventually integrated into emerging clades, but cassette genotypes were variable and usually preceded or supplemented by other resistance determinants. For example, the stepwise acquisition of resistance in ST772-MSSA occurred first through the chromosomal integration of a multidrug-resistance plasmid, followed by a shift in the grlA mutation conferring fluoroquinolone resistance (S80F to S80Y) and eventual fixation of the short 5C2 variant of SCCmec-V (13), whereas ST93-MRSA-IV emerged after a singular acquisition event of SCCmec-IV (12).

We hypothesize that AMR acquisition enables niche transitions into host populations with distinct socioeconomic structure and population densities, particularly those in urban or industrialized settings. These “AMR spillover” events show patterns in Re reminiscent of pathogens recruiting into susceptible host populations, where spikes in the effective reproduction number are followed by establishment of sustained transmission (Re ∼ 1) or elimination (Re < 1). Fixation of resistance determinants and sustained transmission suggests that host epidemiological factors such as widespread antibiotic use in the community, improved access to health care services and treatment, public health responses, or antimicrobial contamination may constitute a new adaptive landscape for the emerging drug-resistant clade. Persistence of the epidemics (Re ∼ 1) over decades was observed following the initial spikes in Re, which often coincided with the first available samples of these lineages (Fig. 4, vertical lines in subplots). In support of this AMR spillover hypothesis, Gustave et al. (45) demonstrated in competition experiments with ST8 (USA300) and ST80 genotypes that antibiotic-resistant strains expressed a fitness advantage over wild-type strains on subinhibitory antibiotic media. Presence of low-level antibiotic pressure may therefore be a crucial epidemiological driver in the emergence of resistant clades in host populations that have widespread access to treatment or may not practice effective antibiotic stewardship.

Our analysis suggests that host epidemiology has played an underappreciated role in the emergence and dissemination of community-associated MRSA. In some lineages, surges in transmission occurred several years after acquisition of AMR (ST80-MRSA-IV expansion in Europe; ST59-MRSA-V expansion in Taiwan; ST1-MRSA-IV expansion in Europe) (Fig. 4). In one example, a sharp increase in Re occurred nearly a decade after SCCmec-IV was acquired by ST1 strains circulating in Romania (15, 17, 18) and coincided precisely with integration of Romania into the European Union in 2007 (Fig. 4). We also noted increases in the effective reproduction number that occurred without further genomic changes in ST93-MRSA sublineages, concurrent with the introduction of these strains into new host populations (ST93-MRSA-IV in PNG, FNQ, and NZ) (Figs. 2 and 4). These observations may be indicative of local competitive interactions with prevailing lineages or changes in host epidemiology, including health care or social policies, population contact density, changes in age-specific mixing patterns, or the opening of markets and borders. Overall, these patterns in transmission dynamics of MRSA clades support the hypothesis that antibiotic-resistance acquisition may have facilitated transition into new host populations with a distinct epidemiological landscape. AMR acquisition and subsequent changes in host epidemiology may therefore be key drivers in the emergence and dissemination of community-associated MRSA.

We also observed epidemic transmission in symplesiomorphic MSSA populations of ST8 and ST152 in West Africa (10, 14), as well as ST93 circulating among Indigenous communities in Northern Australia (12, 28, 46) (Re > 1; Table 1). While the emergence of ST8-MSSA-WestAfrica was strongly associated with the acquisition of trimethoprim= and tetracycline=resistance determinants (dfrG, tetK), the association of AMR genes was less clear in the divergence of ST152-MSSA-WestAfrica, and no singular acquisition of AMR determinants was evident at the divergence of ST93-MSSA-Australia (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). However, it is notable that these clades emerged on an enriched background of penicillin (blaZ) (ST8-MSSA-WestAfrica, ST93-MSSA-Australia, ST152-MSSA-WestAfrica) and fosfomycin (fosD) resistance (ST8-MSSA-WestAfrica). Surges in transmission at the divergence of epidemic community-associated MSSA clades, as observed for ST93-MSSA-Australia, may therefore primarily be driven by host epidemiology. MSSA clade emergence in all three cases preceded the emergence of MRSA clades (Table 1). Symplesiomorphic MSSA clades in West Africa may be circulating in socioeconomic settings that facilitate the spread of community-associated strains, similar to those experienced by many remote Indigenous communities in Australia, including high burdens of skin disease, domestic overcrowding, and poor access to health care or other public services (12, 46–49).

While birth–death models have been extensively applied to viral pathogens, their application to bacterial pathogens has important implications and limitations. First, we note uncertainty deriving from sparse sampling of bacterial populations, which we attempted to mitigate by using published collections of metadata-complete and lineage-representative S. aureus genomes. However, there was a lack of data on ancestral MSSA strains, a problem pointed out explicitly for ST80 (7) and ST59 (9), but also relevant to ST772 (13). These effects appeared less severe for ST8, for which there was a wide sampling range going back to 1953 (10), and for ST93 (12, 16), which had well-represented MSSA collections from the NT, and for which the MRCA and origin of the lineage were estimated to have occurred within a year (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). We addressed sampling bias toward the present by allowing piecewise changes in the sampling proportion consistent with sampling effort for each lineage. Second, the application of birth–death models assumes host to host transmission, but many bacterial pathogens spread at least partially by environmental routes. Compartmentalized models, in which samples can be assigned to explicit human and environmental transmission pathways, may be a promising way to investigate the epidemiological dynamics of some bacterial species (37). Third, asymptomatic carriage over long periods of time can be common for bacterial pathogens, including for S. aureus. Birth–death models in this study predicted lineage- and clade-specific infectious periods that suggest prolonged infectious periods over several years in concordance with long-term cohort studies with lineage-resolved data on S. aureus (50, 51). Variation in our model estimates could reflect differential local modes of persistence in the host or community and are susceptible to factors that we were not able to explicitly model, including access to health care services and treatment, among others. It should be noted that the lineage-wide averages of infectious periods computed in this study may not reflect the considerable heterogeneity in carriage duration that likely arises from the distribution of permanent and transient carriers across the population (52, 53). Finally, the impact of recombination, common among many bacterial species, is currently not well understood in the context of birth–death models. While recombination was negligible in our highly clonal lineage- and outbreak-level data of S. aureus, we advise caution when applying these models to more diverse genome collections or highly recombinant bacterial species. In coalescent models and simulations with parameters derived from Escherichia coli, systematic bias in the Ne toward the present was found when retaining or removing recombination (54). Evaluations of the effect of recombination on the inference of the Re should be done before expanding this work to more recombinant bacterial species.

Despite the limitations of this study, the phylodynamic estimates observed across sequence types are remarkably consistent with decades of molecular and epidemiological work that has characterized the global emergence and spread of community-associated S. aureus lineages, including their notable emergence in the 1990s and subsequent establishment across their respective geographical distributions. We provide genomic evidence for epidemic transmission of MRSA strains in Pakistan and PNG, as well as for MSSA strains in African countries and northern Australia, where sociodemographic factors may play an underappreciated role in the transmission dynamics and epidemic potential of these lineages. Ongoing epidemic transmission of ST93-MSSA and ST93-MRSA is of concern for Indigenous communities in the NT and FNQ and we provide evidence for the establishment of ST93-MRSA in PNG. Our work underlines the importance of considering remote and disadvantaged populations on domestic and international levels. Social and public health inequalities (28, 55) appear to facilitate the emergence and circulation of community-associated S. aureus.

Materials and Methods

Outbreak Sampling and Sequencing.

We collected isolates from outbreaks in two remote populations in northern Australia and PNG (Fig. 1). Isolates associated with pediatric osteomyelitis cases (mean age of patients, 8 y) were collected from 2012 to 2017 (n = 42) from Kundiawa, Simbu Province (27), and from 2012 to 2018 (n = 35) from patients in the neighboring Eastern Highlands province town of Goroka. We supplemented the data with MSSA isolates associated with severe hospital-associated infections and blood cultures in Madang (Madang Province; n = 8) and Goroka (n = 12). Isolates from communities in FNQ, including metropolitan Cairns, the Cape York Peninsula, and the Torres Strait Islands (n = 91), were a contemporary sample from patients with skin and soft-tissue infections or osteomyelitis presentations in 2019. Isolates were recovered on Luria broth (LB) agar from clinical specimens, using routine microbiological techniques at Queensland Health and the Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research. Isolates were transported on swabs from monocultures to the Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine, where they were cultured in 10 mL of LB broth at 37 °C overnight and stored at −80 °C in glycosol and LB. Samples were regrown prior to sequencing, and a single colony was placed into in-house lysis buffer (20 mM Tris⋅HCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 1.2% Triton-100) and sequenced at the Doherty Applied Microbial Genomics laboratory using 100-bp paired-end libraries on Illumina HiSeq. Illumina short-read reads from the global lineages included in this study were collected from the European Nucleotide Archive (Datasets S2–S4).

Genome Assembly and Variant Calling.

Illumina data were adapter- and quality-trimmed with Fastp v0.20 (56) before de novo assembly with Shovill v1.0.0 (https://github.com/tseemann/shovill) using downsampling to 100× genome coverage and the Skesa assembler (57). Assemblies were genotyped with SCCion v0.2.0 (https://github.com/esteinig/sccion), a wrapper for common tools used in S. aureus genotyping from reads or assemblies. These include multilocus sequence, resistance and virulence factor typing with mlst and Abricate (https://github.com/tseemann) using the ResFinder and virulence factor databases (58, 59). SCCmec types were called using the best Mash (60) match of the assembled genome against a sketch of the SCCmecFinder database (61) and confirmed with mecA gene typing from the ResFinder database. Antibiotic resistance to 12 common antibiotics were typed with Mykrobe v0.7.0 (62); this strategy was used for all lineage genomes to confirm or supplement (10, 12) antibiotic-resistance determinants as presented in original publications. Strains belonging to ST93 (FNQ, PNG) and ST772 (Pakistan) were extracted and combined with available sequence data from previous studies on the ST772 (n = 359) and the ST93 (n = 575) lineages. Snippy v4.6.0 (https://github.com/tseemann/snippy) was used to call core-genome SNPs against the ST93 (6,648 SNPs) or ST772 (n = 7,246 SNPs) reference genomes JKD6159 (63) and DAR4145 (13). Alignments were purged of recombination with Gubbins (64) using a maximum of five iterations and the GTR+G model in RAXML-NG v0.9.0. Quality control, assembly, genotyping, variant calling and ML tree construction, statistical phylodynamic reconstruction, and exploratory Bayesian analyses were implemented in Nextflow (65) for reproducibility of the workflows (https://github.com/np-core/phybeast). Phylogenetic trees and metadata were visualized with Interactive Tree of Life (ITOL) (66). All program versions are fixed in the container images used for analysis in this article (Data, Materials, and Software Availability).

ML Phylogenetics and Dynamics.

We used an ML approach with TreeTime v0.7.1 (67) to obtain a time-scaled phylogenetic tree by fitting a strict molecular clock to the data (using sampling dates in years throughout). Accuracy for an equivalent statistical approach using least-squares dating (68) is similar to that obtained using more sophisticated Bayesian approaches with the advantage of being computationally less demanding (69). As input, we used the phylogenetic tree inferred using ML in RAxML-NG after removing recombination with Gubbins. The molecular clock was calibrated using the year of sample collection (i.e., heterochronous data) with least-squares optimization to find the root, while accounting for shared ancestry (covariation) and obtaining uncertainty around node ages and evolutionary rates. We also estimated the ML piecewise (skyline) coalescent on the tree using default settings, which provides a baseline estimate of the change in Ne over time. Temporal structure of the data was assessed by conducting a regression of the root to tip distances of the ML tree as a function of sampling time and a date-randomization test on the TreeTime estimates with 100 replicates (69, 70) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). All trees were visualized in ITOL and node-specific divergence dates extracted in Icytree (71).

Bayesian Phylodynamics and Prior Configurations.

We used the Bayesian coalescent skyline model to estimate changes in Ne, and we implemented the birth–death skyline from the bdsky package (https://github.com/laduplessis/bdskytools) for BEAST v2.6 (34) to estimate changes in the effective reproduction number (Re) (33, 72). Birth–death models consider dynamics of a population forward in time using the birth (transmission) rate (λ), the death (become uninfectious) rate (δ), the sampling probability (ρ), and the time of the start of the population or outbreak (origin time [T]). The Re can be directly computed from these parameters by dividing the birth rate by the death rate () (33).

For lineage-wide analysis, we used all available samples from each sequence type, including MSSA and MRSA clades, but we compared model estimates from the entire lineage to distinct clade subsets to mitigate the effect of population structure from well-sampled clones like ST93 (Table 1 and Fig. 2B, Re estimates for ST93-MSSA and -MRSA). Median parameter estimates with 95% credible intervals and Markov chain traces were inspected in Tracer v1.7.1 to assess convergence (73). We implemented Python utility functions to generate XML files and configure priors more conveniently in a standardized form implemented in the NanoPath package (https://github.com/np-core/nanopath). Plots were constructed with scripts (https://github.com/esteinig/ca-mrsa) that use the bdkytools package, including computation of the 95% highest posterior density median intervals (here referred to as credible intervals) using the Chen and Shao algorithm implemented in the boa package for R (74). We chose to present median posterior intervals, since some posterior distributions (lognormal) had long tails (e.g., origin or become-uninfectious rates; SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Icytree was used to inspect Bayesian maximum clade credibility trees derived from the posterior sample of trees. In the coalescent skyline model for each lineage, we ran exploratory chains of 200 million iterations, varying the number of equidistant intervals over the tree height (dimension [d]) specified for the priors describing the population and estimated interval (dimension) size (d ∈ {2, 4, 8, 16}; SI Appendix, Fig. S2). As posterior distributions were largely congruent (Top Rows in SI Appendix, Fig. S2), we selected a sufficient number of intervals to model changes in Ne of each lineage over time (d = 4; d = 8).

In the birth–death skyline models, priors across lineages were configured as follows: we used a Gamma(2.0, 40.0) prior for the T parameter, covering the past 100 y or longer. We chose a Gamma(2.0, 2.0) prior for the reproduction number, covering a range of possible values observed for S. aureus sequence types in different settings (50, 75–77), which may have occurred over the course of lineage evolution. We configured the reproduction number prior (Re) to a number of equally sized intervals over the tree; a suitable interval number was selected by running exploratory models for each lineage with 100 million iterations (d = 5 to 10) followed by a comparison of parameter estimates under these configurations (occurrence of stable posterior distributions, absence of bi- or multimodal posteriors). Because sequence type–specific becoming-noninfectious rates in community-associated S. aureus are not well known, either from long-term carriage studies or phylogenetic reconstructions (22, 52, 53, 78), we explored a range of prior configurations for the becoming-uninfectious rate parameter (δ), including a flat uniform prior uniform(1.0, 1.0) and a lognormal(μ, 1.0) prior with μ = 0.1 (10-y infectious period), μ = 0.2 (5 y infectious period), and μ = 1.0 (1 y infectious period). We chose a lognormal(1.0, 1.0) prior, as the resulting parameters estimates were coherent (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Lineage-wide sensitivity analysis showed that estimates across lineages were not driven by the prior (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Sampling proportion (ρ) was fixed to zero in the interval ranging from the origin to the first sample (presample period); the remaining time until present (sampling period) was estimated under a flat beta(1.0, 1.0) prior, accounting for sampling bias toward the present as well as largely unknown estimates of global sampling proportions across lineages. Final lineage models were run with 500 million iterations on graphical processing units with the BEAGLE v3.0 library under a GTR+G substitution model with four rate categories. We used a strict molecular clock with a lognormal(0.0003, 0.3) rate prior in real space, as all lineages evolved measurably (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Models were run until chains were mixed and effective sample size (ESS) values were greater than 200, as confirmed in Tracer.

Last, we ran birth–death skyline models on specific clades within the lineage phylogenies, including the ancestral and symplesiomorphic MSSA populations, the USA300 sublineages, and importations of ST93, ST772, and ST8 (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S8). For each subset of strains, we extracted the core-genome variant alignment subset, configured the reproduction number prior to a single estimate over the clade (since in outbreak data sets the number of sequences per clade was smaller than 100 and the sampling interval smaller than 10 y) (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Because temporal signal is lost in the clade subsets, we fixed the substitution rate to the lineage-wide estimate in all runs for 100 million iterations for the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), with trees sampled every 1,000 steps. Runs were quality controlled by assuring that chains mixed and ESS values for all posteriors were greater than 200. Since sufficient samples and a wide sampling interval were available to track Re changes in ST93-MSSA (n = 116 in the NT) and ST93-MRSA clades (n = 278, AEC) over time (Fig. 2, Inset Plots), we explored a stable configuration of the reproduction number prior across equally spaced intervals (d = 5 to 10) with 200 million iterations of the MCMC. We explored Gamma(2.0, θ) distributions where θ ∈ {0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0} in the Re prior of sublineages and outbreaks. This was to guard against bias toward inferring sustained transmission (Re ∼ 1) in outbreak models with limited data and temporal signal from subset alignments (see representative examples in SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Results from the model runs under the conservative Gamma(2.0, 0.5) prior assert only minor differences compared with higher configurations (consistently Re > 1), and the conservative estimates are presented in Table 1. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis for all sublineage models whereby we ran the models under the prior only (SI Appendix, Fig. S8, note that under-the-prior posteriors are still influenced by dates, albeit not the genetic data). With the exception of ST93-NT and ST93-NZ we asserted that estimates of Re were not driven by the prior and dates alone in all sublineages and outbreaks. Full exploratory data can be found in the data repository for this study.

Ethics Statement.

Consent was not required, since data were collected from bacterial isolates, which were collected as part of routine clinical care; information on the source of isolates was removed, and no human data were included.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

E.S. was supported by a Policy relevant infectious disease simulation and mathematical modelling (PRISM2) & Improving Health Outcomes in the Tropical North (HOT North) pilot grant (Australian National Health and Medical Research Council [NHMRC] ID 1131932). C.F. is supported by a HOT North fellowship (NHMRC ID 1131932). S.Y.C.T. is supported by an Australian NHMRC fellowship (ID 1145033). GPU models were run on the Linkage Infrastructure, Equipment and Facilities (LIEF) HPC-GPGPU Facility hosted at the University of Melbourne (LIEF grant LE170100200).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. V.F.J. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

See online for related content such as Commentaries.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2204993119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

Sequencing data can be found at National Center for Biotechnology Information BioProject PRJNA657380 (79). XML model files for replicating the analyses and scripts to replicate the plots in this article can be found at https://github.com/esteinig/ca-mrsa (80) and https://github.com/np-core/nanopath (81).

References

- 1.Tong S. Y. C., Davis J. S., Eichenberger E., Holland T. L., Fowler V. G. Jr., Staphylococcus aureus infections: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 603–661 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.David M. Z., Daum R. S., Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23, 616–687 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzgerald J. R., Holden M. T. G., Genomics of natural populations of Staphylococcus aureus. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 70, 459–478 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner N. A., et al. , Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: An overview of basic and clinical research. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 203–218 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris S. R., et al. , Evolution of MRSA during hospital transmission and intercontinental spread. Science 327, 469–474 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giulieri S. G., Tong S. Y. C., Williamson D. A., Using genomics to understand meticillin- and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Microb. Genom. 6, e000324 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stegger M., et al. , Origin and evolution of European community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. mBio 5, e01044-14 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Planet P. J., et al. , Parallel epidemics of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 infection in North and South America. J. Infect. Dis. 212, 1874–1882 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward M. J., et al. , Identification of source and sink populations for the emergence and global spread of the East-Asia clone of community-associated MRSA. Genome Biol. 17, 160 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strauß L., et al. , Origin, evolution, and global transmission of community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus ST8. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E10596–E10604 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Challagundla L., et al. , Range expansion and the origin of USA300 North American epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. mBio 9, e02016-17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Hal S. J., et al. , Global scale dissemination of ST93: A divergent Staphylococcus aureus epidemic lineage that has recently emerged from remote Northern Australia. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1453 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinig E. J., et al. , Evolution and global transmission of a multidrug-resistant, community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineage from the Indian subcontinent. mBio 10, e01105-19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baig S., et al. , Evolution and population dynamics of clonal complex 152 community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. mSphere 5, e00226-20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Earls M. R., et al. , Exploring the evolution and epidemiology of European CC1-MRSA-IV: Tracking a multidrug-resistant community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone. Microb. Genom. 7, 000601 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coombs G. W., et al. , The molecular epidemiology of the highly virulent ST93 Australian community Staphylococcus aureus strain. PLoS One 7, e43037 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Earls M. R., et al. , The recent emergence in hospitals of multidrug-resistant community-associated sequence type 1 and spa type t127 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus investigated by whole-genome sequencing: Implications for screening. PLoS One 12, e0175542 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Earls M. R., et al. , A novel multidrug-resistant PVL-negative CC1-MRSA-IV clone emerging in Ireland and Germany likely originated in South-Eastern Europe. Infect. Genet. Evol. 69, 117–126 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edslev S. M., et al. , Identification of a PVL-negative SCCmec-IVa sublineage of the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus CC80 lineage: Understanding the clonal origin of CA-MRSA. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 24, 273–278 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinig E. J., et al. , Single-molecule sequencing reveals the molecular basis of multidrug-resistance in ST772 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Genomics 16, 388 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uhlemann A.-C., et al. , Molecular tracing of the emergence, diversification, and transmission of S. aureus sequence type 8 in a New York community. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 6738–6743 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alam M. T., et al. , Transmission and microevolution of USA300 MRSA in U.S. households: Evidence from whole-genome sequencing. mBio 6, e00054 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blomfeldt A., et al. , Emerging multidrug-resistant Bengal Bay clone ST772-MRSA-V in Norway: Molecular epidemiology 2004-2014. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36, 1911–1921 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harastani H. H., Tokajian S. T., Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clonal complex 80 type IV (CC80-MRSA-IV) isolated from the Middle East: A heterogeneous expanding clonal lineage. PLoS One 9, e103715 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holden M. T. G., et al. , A genomic portrait of the emergence, evolution, and global spread of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pandemic. Genome Res. 23, 653–664 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tong S. Y. C., et al. , Genome sequencing defines phylogeny and spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a high transmission setting. Genome Res. 25, 111–118 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Planet P. J., Life after USA300: The rise and fall of a superbug. J. Infect. Dis. 215 (suppl. 1), S71–S77 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowen A. C., Daveson K., Anderson L., Tong S. Y., An urgent need for antimicrobial stewardship in Indigenous rural and remote primary health care. Med. J. Aust. 211, 9–11.e1 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guthridge I., Smith S., Horne P., Hanson J., Increasing prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in remote Australian communities: Implications for patients and clinicians. Pathology 51, 428–431 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wozniak T. M., et al. , Geospatial epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus in a tropical setting: An enabling digital surveillance platform. Sci. Rep. 10, 13169 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laman M., et al. , Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Papua New Guinea: A community nasal colonization prevalence study. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 111, 360–362 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aglua I., et al. , Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Melanesian children with haematogenous osteomyelitis from the Central Highlands of Papua New Guinea. Int. J. Pediatr. 6, 8361–8370 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stadler T., Kühnert D., Bonhoeffer S., Drummond A. J., Birth-death skyline plot reveals temporal changes of epidemic spread in HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 228–233 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouckaert R., et al. , BEAST 2.5: An advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLOS Comput. Biol. 15, e1006650 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Volz E., et al. ; COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) consortium, Assessing transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Nature 593, 266–269 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duchêne S., et al. , Genome-scale rates of evolutionary change in bacteria. Microb. Genom. 2, e000094 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ingle D. J., Howden B. P., Duchene S., Development of phylodynamic methods for bacterial pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 29, 788–797 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kühnert D., et al. , Tuberculosis outbreak investigation using phylodynamic analysis. Epidemics 25, 47–53 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sabin S., et al. , A seventeenth-century Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome supports a Neolithic emergence of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Genome Biol. 21, 201 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Syed M. A., et al. , Detection and molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from table eggs in Haripur, Pakistan. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 15, 86–93 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bakthavatchalam Y. D., et al. , Genomic portrait of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST772-SCCmec V lineage from India. Gene Rep. 24, 101235 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberts M. C., et al. , MRSA strains in Nepalese Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) and their environment. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2505 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Montelongo C., Mores C. R., Putonti C., Wolfe A. J., Abouelfetouh A., Whole-genome sequencing of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus haemolyticus clinical isolates from Egypt. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e0241321 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.P. J. Planet et al., Emergence of the epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300 coincides with horizontal transfer of the arginine catabolic mobile element and speG-mediated adaptations for survival on skin. mBio 4, e00889-13 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Gustave C.-A., et al. , Demographic fluctuation of community-acquired antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineages: Potential role of flimsy antibiotic exposure. ISME J. 12, 1879–1894 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harch S. A. J., et al. , High burden of complicated skin and soft tissue infections in the Indigenous population of Central Australia due to dominant Panton Valentine leucocidin clones ST93-MRSA and CC121-MSSA. BMC Infect. Dis. 17, 405 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williamson D. A., Coombs G. W., Nimmo G. R., Staphylococcus aureus ‘Down Under’: Contemporary epidemiology of S. aureus in Australia, New Zealand, and the South West Pacific. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20, 597–604 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bowen A. C., et al. , The global epidemiology of impetigo: A systematic review of the population prevalence of impetigo and pyoderma. PLoS One 10, e0136789 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas L., et al. , Burden of skin disease in two remote primary healthcare centres in northern and central Australia. Intern. Med. J. 49, 396–399 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Di Ruscio F., et al. , Quantifying the transmission dynamics of MRSA in the community and healthcare settings in a low-prevalence country. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 14599–14605 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mork R. L., et al. , Longitudinal, strain-specific Staphylococcus aureus introduction and transmission events in households of children with community-associated meticillin-resistant S aureus skin and soft tissue infection: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 188–198 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scanvic A., et al. , Duration of colonization by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus after hospital discharge and risk factors for prolonged carriage. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32, 1393–1398 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muthukrishnan G., et al. , Longitudinal genetic analyses of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage dynamics in a diverse population. BMC Infect. Dis. 13, 221 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lapierre M., Blin C., Lambert A., Achaz G., Rocha E. P. C., The impact of selection, gene conversion, and biased sampling on the assessment of microbial demography. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1711–1725 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bond C. J., Singh D., More than a refresh required for closing the gap of Indigenous health inequality. Med. J. Aust. 212, 198–199.e1 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen S., Zhou Y., Chen Y., Gu J., fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Souvorov A., Agarwala R., Lipman D. J., SKESA: Strategic k-mer extension for scrupulous assemblies. Genome Biol. 19, 153 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zankari E., et al. , Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67, 2640–2644 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen L., Zheng D., Liu B., Yang J., Jin Q., VFDB 2016: Hierarchical and refined dataset for big data analysis--10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D694–D697 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ondov B. D., et al. , Mash: Fast genome and metagenome distance estimation using MinHash. Genome Biol. 17, 132 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaya H., et al. , SCCmecFinder, a web-based tool for typing of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec in Staphylococcus aureus using whole-genome sequence data. mSphere 3, e00612-17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hunt M., et al. , Antibiotic resistance prediction for Mycobacterium tuberculosis from genome sequence data with Mykrobe [version 1; peer review: 2 approved, 1 approved with reservations]. Wellcome Open Res. 4, 191 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chua K., et al. , Complete genome sequence of Staphylococcus aureus strain JKD6159, a unique Australian clone of ST93-IV community methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 192, 5556–5557 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Croucher N. J., et al. , Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e15 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Di Tommaso P., et al. , Nextflow enables reproducible computational workflows. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 316–319 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Letunic I., Bork P., Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: Recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W256–W259 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sagulenko P., Puller V., Neher R. A., TreeTime: Maximum-likelihood phylodynamic analysis. Virus Evol. 4, vex042 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.To T.-H., Jung M., Lycett S., Gascuel O., Fast dating using least-squares criteria and algorithms. Syst. Biol. 65, 82–97 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duchêne S., Geoghegan J. L., Holmes E. C., Ho S. Y. W., Estimating evolutionary rates using time-structured data: A general comparison of phylogenetic methods. Bioinformatics 32, 3375–3379 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Duchêne S., Duchêne D., Holmes E. C., Ho S. Y. W., The performance of the date-randomization test in phylogenetic analyses of time-structured virus data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 1895–1906 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vaughan T. G., IcyTree: Rapid browser-based visualization for phylogenetic trees and networks. Bioinformatics 33, 2392–2394 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Drummond A. J., Rambaut A., Shapiro B., Pybus O. G., Bayesian coalescent inference of past population dynamics from molecular sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 1185–1192 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rambaut A., Drummond A. J., Xie D., Baele G., Suchard M. A., Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 67, 901–904 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smith B. J., boa: An R package for MCMC output convergence assessment and posterior inference. J. Stat. Softw. 21, 1–37 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 75.D’Agata E. M. C., Webb G. F., Horn M. A., Moellering R. C. Jr., Ruan S., Modeling the invasion of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus into hospitals. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48, 274–284 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cooper B. S., et al. , Quantifying type-specific reproduction numbers for nosocomial pathogens: Evidence for heightened transmission of an Asian sequence type 239 MRSA clone. PLOS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002454 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Prosperi M., et al. , Molecular epidemiology of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the genomic era: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 3, 1902 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gordon N. C., et al. , Whole-genome sequencing reveals the contribution of long-term carriers in Staphylococcus aureus outbreak investigation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 55, 2188–2197 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Steinig E., et al. , Community-associated Staphylococcus aureus from Papua New Guinea, Far North Queensland and Pakistan. BioProject. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject?term=PRJNA657380. Deposited 27 June 2022.

- 80.Steinig E., et al. , Phylodynamic modelling of community-associated MRSA. GitHub. https://github.com/esteinig/ca-mrsa. Deposited 1 September 2021.

- 81.Steinig E., et al. , Python package to manage pipelines and orchestrate data processing fro the NanoPath ecosystem. GitHub. https://github.com/np-core/nanopath. Deposited 1 September 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequencing data can be found at National Center for Biotechnology Information BioProject PRJNA657380 (79). XML model files for replicating the analyses and scripts to replicate the plots in this article can be found at https://github.com/esteinig/ca-mrsa (80) and https://github.com/np-core/nanopath (81).