Abstract

Background:

To determine the seroprevalence of human cystic echinococcosis/hydatidosis which is one of the most important zoonotic diseases by ELISA using native antigen B in Semnan and Sorkheh, Semnan province, Iran, where no significant information about human infection exists.

Methods:

Overall, 957 human serum samples were randomly prepared from Semnan, Sorkheh, and its 13 surrounding villages in different seasons from 2017 to 2018. Antigen B was prepared from native hydatid cyst fluid of domestic sheep. All serum samples were evaluated by ELISA while the suspected cases were rechecked. The cut-off was calculated as the X ¯ ±2SD.

Results:

Overall, 48(5%) out of 957 (422 males and 535 females) were positive for hydatidosis. The seropositivity based on sex showed 20(2.1%) out of 422 in males and 28(2.9%) out of 535 in females. The distribution of seropositive samples based on residence area showed 41 (4.3) out of 882 in urban and 7 (0.7) out of 75 in rural areas. The highest seroprevalence cases was among housewives (2.1%) followed by employers (1.5%). Based on education, source of drinking water, and age groups the highest seropositivity was observed in high school and less, in the plumping water consumers, and 50 to 59 yr old age group, respectively. There was a significant difference between seropositivity with occupation, literacy, and age group (P<0.05). Semnan with 4% seropositivity had the highest prevalence followed by Sorkheh, county.

Conclusion:

High prevalence of the disease in this area emphasizes the importance of increasing people’s awareness about hydatidosis.

Keywords: Hydatidosis, Cystic echinococcosis, Serology, Iran

Introduction

Cystic echinococcosis/hydatidosis is one of the most important parasitic zoonosis in the world including the Middle East (1). It is one of the 17 neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) recognized by WHO (2). The life cycle of the parasite involves two hosts: dogs and other canids as the definitive host, and sheep, camel, cattle, buffalo, horses, pigs, and cervids as intermediate hosts (3, 4). The adult stage is observed in the small intestine of carnivores. The disease is a significant economic and public health problem worldwide (4, 5). Humans are intermediate incidental hosts (4). Eating the contaminated foods with dog’s feces containing eggs is the most important route for human infection (4). They are infected by ingesting the parasite eggs leading to cyst formation mainly in the liver followed by the lungs and other organs (4, 6). Human CE incidence is noticeable in endemic areas including Iran (7–9). Iran is regarded as an endemic-hyper endemic country, where the seroprevalence rate has been reported between 0.22% and 15.4% in different provinces in Iran (8).

Diagnosis and follow-up of the disease is essentially confirmed via a combination of the relevant history, serological and proteomics examinations, along with imaging techniques (4, 7, 10–13). A variety of serological methods including indirect hemagglutination (IHA), immunoblotting, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), indirect fluorescent-antibody (IFA), latex agglutination, and immune-chromatography tests have been expanded and utilized for laboratory diagnosis of human hydatidosis in recent years. For the development of these assays different antigens from adult worms, cyst protoscolices, and eggs of the worms or hydatid cyst fluid have been provided, purified, and evaluated in the mentioned serological tests. Ag B is an essential antigen obtained from hydatid cyst fluid (HCF) with high specificity and sensitivity in serodiagnosis of the disease (14). Due to the importance of hydatidosis and the lack of the disease information in Semnan Province, we aimed to evaluate the seroprevalence of the disease in Semnan and Sorkheh, Semnan Province, utilizing Ag B by ELISA method.

Materials and Methods

The present study was carried out in Semnan and Sorkheh, two cities in Semnan Province, central Iran. Semnan city, capital of the province, is located at 35.2256°N, 54.4342°E. Sorkheh city is located at 35.4677°N, 53.2127°E, and west of Semnan (Fig. 1). According to the census of 2010, the population of these cities was about 175181 (https://www.amar.org.ir).

Fig. 1:

The map of study area showing Semnan, Sorkheh and suburbs, where the samples were collected

Serum Sample collection

Using systematic random sampling 957 serum samples were collected from 4 urban and 13 rural medical health centers of Semnan and Sorkheh cities in 2017–2018. For calculating the needed sample, the expected prevalence of 0.05% at a confidence level of 95% was used. Overall, 882 and 75 samples were randomly collected from urban and rural areas respectively.

Informed consent was filled out for all participants. Moreover, a questionnaire with some information including age, gender, place of residence, occupation, level of education, vegetable consumption, contact with dog and sheep, etc. was completed for each case. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (IR.SUMS.REC.1396.S215)

Preparation of Hydatid Cyst Fluids

Hydatid cyst fluid (HCF) was aseptically prepared from the livers of infected sheep at Semnan industrial slaughterhouse. The protoscoleces and other particles were separated from HCF by centrifugation at 3000× g in 15 min. Finally collected HCF was stored at −20 °C before use.

Preparation of Antigen B

Antigen B was prepared from HCF, as originally described (15–16). Briefly, 100 ml of HCF was dialyzed overnight against 5 mM of acetate buffer (pH 5) at 4 °C and centrifuged at 50 000×gr for 30 min. The supernatant was removed and the sediment was dissolved in 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 8). Saturated ammonium sulfate was used to remove the globulins from the sample. Finally, the sample was boiled in a water bath for 15 min and centrifuged at 50 000× g for 60 min to separate heat-stable antigen B from other components. Bradford protein assay was utilized for the determination of Ag B concentration (17)

ELISA

ELISA was carried out in flat-bottom 96-well microplates (Nunc, Maxisorp, Roskilde: Denmark) as previously described (5, 9, 16).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS software ver. 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Chi-square and logistic regression tests were used. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. The cut-off point was set as the mean OD 492 plus 2SD for control samples (30 sera from healthy people). The level of variable which other levels compared with it was determined as reference (Table 1).

Table 1:

Logistic regression analysis of seropositive cases of hydatidosis according to gender, occupation, residency, education, contact with dog, raw vegetable consumption, drinking water status and carrot juice drinking in Semnan and Sorkheh, Semnan Province, Iran

| Variables | Statistical analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| No. Examined (%) | No. Seropositive (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI a ) | P-value | ||

| Gender | Male | 422 (44.1) | 20 (2.1) | Reference b | |

| Female | 535(55.9) | 28 (2.9) | 0.902 (0.500, 1.623) | 0.728 | |

| Occupation | Housewife | 415 (43.4) | 20 (2.1) | Reference | |

| Employer | 209 (21.8) | 14 (1.5) | 0.705 (0.349, 1.426) | 0.331 | |

| Manual worker | 73 (7.6) | 2 (0.2) | 1.797 (0.411, 7.859) | 0.436 | |

| Self-employment | 138 (14.4) | 3 (0.3) | 2.278 (0.667, 7.788) | 0.189 | |

| Rancher | 16 (1.7) | 4 (0.4) | 0.152 (0.045, 0.513) | 0.002 | |

| Farmer | 19 (2.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0.911 (0.116, 7.137) | 0.930 | |

| Unemployed | 87 (9.1) | 4 (0.4) | 1.051 (0.350, 3.154) | 0.930 | |

| Residency | Urban | 882 (92.2) | 41 (4.3) | Reference | |

| Rural | 75 (7.8) | 7 (0.7) | 0.474 (0.205, 1.096) | 0.081 | |

| Education | Illiterate | 91 (9.5) | 11 (1.1) | Reference | |

| Diploma and less than Academic | 640 (66.9) | 28 (2.9) | 3.005 (1.441, 6.270) | 0.003 | |

| 226 (23.6) | 9 (0.9) | 3.315 (1.325, 8.298) | 0.010 | ||

| Contact with dog | No contact | 858 (89.7) | 43 (4.9) | Reference | |

| At home | 28 (2.9) | 1 (0.1) | 1.425 (0.189, 10.732) | 0.731 | |

| On the farm or at work | 35 (3.7) | 0 | - c | 0.998 | |

| 36 (3.8) | 4 (0.4) | 0.422 (0.143, 1.248) | 0.119 | ||

| Sheep-dog | |||||

| Consumption raw vegetables | Daily | 189 (19.7) | 12 (1.3) | Reference | |

| Once a week | 330 (34.5) | 18 (1.9) | 1.175 (0.553, 2.496) | 0.675 | |

| 2–3 times a week | 405 (42.3) | 16 (1.7) | 1.648 (0.764, 3.557) | 0.203 | |

| Not use | 33 (3.4) | 2 (0.2) | 1.051 (0.224, 4.925) | 0.950 | |

| Drinking water | Plumbing | 936 (97.8) | 46 (4.8) | Reference | |

| Fountain | 21 (2.2) | 2 (0.2) | 0.491 (0.111, 2.172) | 0.348 | |

| Consumption carrot Juice | Homemade | 412 (43.1) | 18 (1.9) | Reference | |

| Outdoors | 107 (11.2) | 6 (0.6) | 0.769 (0.298, 1.987) | 0.588 | |

| Not use | 438 (45.8) | 24 (2.5) | 0.788 (0.421, 1.475) | 0.456 | |

CI: confidence interval.

Reference: The level of variable which other levels compared with it.

Due to zero in this cell, Odds Ratio cannot be computed in this case

Results

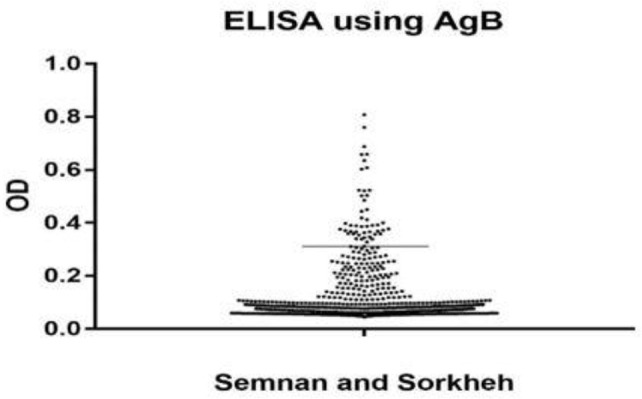

Overall, 48(5%) out of 957 (422 males and 535 females) according to the cut-off point of mean OD 492 plus 2SD for control samples were positive for hydatidosis (Fig.2). The distribution of samples based on residence area was included, 75 rural and 882 urban respectively. Forty-eight (5.0%) samples including 28 (2.9%) females and 20 (2.1%) males were seropositive. In terms of living region, 7(0.7%) and 41(4.3%) of the samples were from rural and urban areas, respectively. According to the occupation, literacy, source of drinking water, and age group, the highest percentage of the cases were recorded among those who had high school diploma and less than that and housewives, used the plumping water and they were 50–59 yr old. There was a significant difference between seropositivity of hydatid cyst and variables such as occupation, literacy, and age group (P<0.05) (Tables 1 and 2). Logistic regression analysis showed that high school and fewer holder certificates showed, 3.0 times more likely to be negative than illiterate (OR=3.005 CI= 1.441, 6.270) and academic variable 3.3 times more likely to be negative than illiterate (OR= 3.315 CI=1.325, 8.298) (Table 1). The distribution of seropositive cases of hydatid cyst in residential areas in different parts of Semnan and Sorkheh, Semnan Province, Iran showed the highest positive rates in Semnan (Table 3).

Fig. 2:

Seroprevalence of human hydatidosis in Semnan, Sorkheh and suburbs, Semnan Province, Iran according to OD of the ELISA test. Under the cut off line are negative tests and upper line the positive cases

Table 2:

Chi- square analysis of seropositive cases of hydatid cyst according to age group (yr) and sex in Semnan and Sorkheh, Semnan Province, Iran

| Variable | No. Sample (%) | Seropositive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age group (yr) | Male | Female | Total (%) | |

| 0 – 9 | 5 (0.5) | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| 10 – 19 | 50 (5.2) | 2 | 0 | 2 (0.2) |

| 20 – 29 | 203 (21.2) | 3 | 3 | 6 (0.6) |

| 30 – 39 | 249 (26.0) | 0 | 7 | 7 (0.7) |

| 40 – 49 | 141 (14.7) | 2 | 4 | 6 (0.6) |

| 50 – 59 | 154 (16.1) | 5 | 6 | 11 (1.1) |

| 60 – 69 | 101 (10.6) | 3 | 6 | 9 (0.9) |

| ≥ 70 | 54 (5.6) | 4 | 2 | 6 (0.6) |

| Total | 957 (100) | 20 | 28 | 48 (5.0) |

Fisher’s Exact Test P=0.020

Table 3:

Distribution of seropositive cases of hydatid cyst in residential areas in different parts of Semnan and Sorkheh, Semnan Province, Iran

| Location or area | Seropositive | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| No. Sample | Positive cases no. (%) | |

| Semnan city | 882 | 38 (4.0) |

| Ala | 5 | 0 |

| Dozehir | 1 | 0 |

| Kheyrabad | 19 | 2 (0.2) |

| Roknabad | 5 | 0 |

| Sorkheh city | 60 | 3 (0.3) |

| Aftar | 7 | 2 (0.2) |

| Arvaneh | 3 | 0 |

| Asadabad | 1 | 0 |

| Biyabanak | 3 | 0 |

| Emamzade abdollah | 7 | 0 |

| and Javin | ||

| Ij | 3 | 0 |

| Lasjerd | 7 | 0 |

| Momenabad | 12 | 3 (0.3) |

| Other | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 957 | 48 (5.0) |

Fisher’s Exact Test=19.190 P=0.147

Discussion

The present study, reports the seroprevalence of human hydatidosis in Semnan and Sorkheh, Semnan Province, Iran, using ELISA as 5.0%. The present study is the first seroepidemiological study of hydatidosis in Semnan and Sorkheh, Semnan Province, where 957 adult people referring to health centers in urban and rural areas have been investigated.

Overall, 48(5.0%) out of 957 people were showed positive result by ELISA which is less than those observed in Khorramabad which was 15.4% (16). Furthermore, it is greater than those found in Alborz (3.4%), Esfahan (1.1%), and Meshkinshahr, Ardabil Province (1.79%) (18–20). However, seropositivity in our samples is similar or approximately similar to the results were obtained from the Western part of Iran (5.55%) (21).

The females positive cases (28:2.9%) were greater than males (20:2.1%) with no statistical significance (P=0.728). It is similar to other research works in other provinces of Iran (18, 22–24) and other parts of the world i.e. Libya, Tibetan population southeast Qinghai, China and southern Sudan (25–27). However, the greater percentage of positive individuals in females is in contrast with the number of reporters who reported male individuals with greater positivity (16, 19, 20, 28, 29). According to the occupation, the highest prevalence was observed in housewife group, with statistically significant difference to other groups (P=0.030). This finding is in an agreement with the results of other studies in Iran. This could be due to more contact of housewives with parasite eggs during washing contaminated vegetables, cleaning soil yards in villages, etc. (8, 16, 30).

Regarding the residency, the results of the present study showed that the highest seropositive cases for hydatidosis were observed in urban (4.3%) than rural (0.7%) residents (P=0.092). Our finding is similar to the result of some other researches in Isfahan and Golestan Province respectively (19, 30). However, this result is in contrast to other investigations in Khorramabad in Iran, Kashmir, North India where the highest prevalence has been reported in rural regions (16, 28). As for educational levels, our results showed that the highest rate of infection was observed in certificate holders of high school and less group (2.9%) which is statistically different with other educational levels (P=0.003). This result is similar to the study in Esfahan but is in contrast to the study in Meshkinshahr, where the highest rate of infection was observed in illiterate people and in contrast to Alborz Province where academically educated people had the highest rate of infection (18–20). Regarding the age groups, our study showed that the highest rate of infection (1.1%) was observed in the 50–59 yr age group with a statistical difference to the other age groups (P=0/020). Previous studies have reported the 20–29 yr old age groups as the highest infected age group in Khorramabad while in Esfahan, the 60–69 yr old age group had the highest seropositivity (16, 19).

Among the people with no contact with dog/s, the highest seropositivity was observed in the group who consumed raw vegetables once a week, not using carrot juice, and contaminated drinking water. Consumption of raw vegetables could be a serious risk of achieving seropositivity as the raw vegetable could be infected to different helminths including the eggs of E. granulosus (31). The present study reports 2.1%/19 serum positive in folks who consumed raw vegetable washing with tap water while no parasiticidal agent has been used. Many people consume a green diet from the market in Semnan and Sorkheh. Since environmental contamination is an important risk factor of infection in such a situation.

The relationship between dogs and sheep throughout lifestyles is one of the biggest risk factors for infection. It could be due to the high prevalence of infection of dogs with the parasite in our country (3).

Hydatidosis has extensive spectrum dissemination globally with a high prevalence in components of the Russian Federation and adjacent independent states, China, North, and Africa, Australia, Southern parts of US, Kenya, and parts of Spain, southern Italy, Sardinia, the Middle East, and North Africa (28, 32–35). The range of human CE has been recorded as 5%–10% inside the endemic areas of Peru, Argentina, East Africa, principal Asia, and China. The highest seropositivity of the disease has been reported from Lorestan Province in Iran with 15.4% (16).

Conclusion

The rate of seropositivity in Semnan Province is nearly high and seems to be due to multifactor effects of the environment, stray dogs, consumption of raw vegetables, and illiteracy. More health measurements including dog/s controls should be considered.

Journalism Ethics considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the office of Vice Chancellor for Research at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Grant no. 95-01-01-12655. Technical assistance of Mrs. Kazemian from SUMS, Mrs. Arab Salmani and Dr. Fasihi from BUMS and the health personnel from Semnan and Sorkheh is acknowledged.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Alvarez Rojas CA, Romig T, Lightowlers MW. (2014). Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato genotypes infecting humans-review of current knowledge. Int J Parasitol, 44 (1): 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agudelo Higuita NI, Brunetti E, McCloskey C. (2016). Cystic Echinococcosis. J Clin Microbiol, 54 (3): 518–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fallah M, Taherkhani H, Sadjjadi SM. (1995). Echinococcosis in the stray dogs in Hamadan, west of Iran. Iran J Med Sci, 20 (3–4): 170–72. [Google Scholar]

- 4.da Silva AM. (2010). Human echinococcosis: a neglected disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract, 2010: 583297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebrahimipour M, Sadjjadi SM, Yousofi Darani H, Najjari M. (2017). Molecular Studies on Cystic Echinococcosis of Camel (Camelus dromedarius) and Report of Echinococcus ortleppi in Iran. Iran J Parasitol, 12 (3): 323–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadjjadi SM, Mikaeili F, Karamian M, Maraghi S, Sadjjadi FS, Shariat-Torbaghan S, Kia EB. (2013). Evidence that the Echinococcus granulosus G6 genotype has an affinity for the brain in humans. Int J Parasitol, 43 (11): 875–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadjjadi SM, Ardehali S, Noman-Pour B, Kumar V, Izadpanah A. (2001). Diagnosis of cystic echinococcosis: ultrasound imaging or countercurrent immunoelectrophoresis? East Mediterr Health J, 7 (6): 907–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rokni MB. (2009). Echinococcosis/hydatidosis in Iran. Iran J Parasitol, 4 (2): 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rafiei A, Hemadi A, Maraghi S, Kaikhaei B, Craig PS. (2007). Human cystic echinococcosis in nomads of south-west Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J, 13 (1): 41–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadjjadi FS, Ahmadi N, Rezaie-Tavirani M, Zali H. (2021). Following up of surgical treated human liver cystic echinococcosis: A Proteomics approach. Iran J Parasitol, 16 (1): 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA. (2010). Writing Panel for the WHO-IWGE. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop, 114 (1): 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khalilpour A, Sadjjadi SM, Moghadam ZK, Yunus MH, Zakaria ND, Osman S, Noordin R. (2014). Lateral flow test using Echinococcus granulosus native antigen B and comparison of IgG and IgG4 dipsticks for detection of human cystic echinococcosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 91 (5): 994–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sadjjadi FS, Rezaie-Tavirani M, Ahmadi NA, Sadjjadi SM, Zali H. (2018). Proteome evaluation of human cystic echinococcosis sera using two dimensional gel electrophoresis. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench, 11 (1): 75–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siles-Lucas M, Sánchez-Ovejero C, González-Sánchez M, et al. (2017). Isolation and characterization of exosomes derived from fertile sheep hydatid cysts. Vet Parasitol, 236: 22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oriol R, Williams JF, Pérez Esandi MV, Oriol C. (1971). Purification of lipoprotein antigens of Echinococcus granulosus from sheep hydatid fluid. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 20 (4): 569–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zibaei M, Azargoon A, Ataie-Khorasgani M, Ghanadi K, Sadjjadi SM. (2013). The serological study of cystic echinococcosis and assessment of surgical cases during 5 yr (2007–2011) in Khorram Abad, Iran. Niger J Clin Pract, 16 (2): 221–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradford MM. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem, 72: 248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dabaghzadeh H, Bairami A, Kia EB, Aryaeipour M, Rokni MB. (2018). Seroprevalence of Human Cystic Echinococcosis in Alborz Province, Central Iran in 2015. Iran J Public Health, 47 (4): 561–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ilbeigi P, Mohebali M, Kia EB, et al. (2015). Seroepidemiology of Human Hydatidosis Using AgB-ELISA Test in Isfahan City and Suburb Areas, Isfahan Province, Central Iran. Iran J Public Health, 44 (9): 1219–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heidari Z, Mohebali M, Zarei Z, et al. (2011). Seroepidemiological study of human hydatidosis in Meshkinshahr district, ardabil province, Iran. Iran J Parasitol, 6 (3): 19–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zariffard M, Abshar N, Akhavizadegan M, Motamedi G. (1999). Seroepidemiological survey of human hydatidosis in western parts of Iran. Arch Razi Inst, 50: 71–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asghari M, Mohebali M, Kia EB, Farahnak A, Aryaeipour M, Asadian S, Rokni MB. (2013). Seroepidemiology of Human Hydatidosis Using AgB-ELISA Test in Arak, Central Iran. Iran J Public Health, 42 (4): 391–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garedaghi Y, Bahavarnia SR. (2011). Seroepidemiological study of Hydatid Cyst by ELISA method in East-Azarbaijan Province (2009). J Kerman Univ Med Sci, 18 (2): 172–81. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hadadian M, Ghaffarifar F, Dalimi Asl A, Roudbar Mohammadi S. (2008). Seroepidemiological survey of hydatid cyst by ELISA in Kordestan province. Pathobiology Research, 10(3,4): 13–8. (In Persion). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernawi AAA, Ayed NB, Ali A, Khalil EAG. (2016). Sero-prevalence and Exposure Rates of Humans to Echinococcus granulosus Infection in Southern Libya. Int J Current Res, 7 (09): 20392–96. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu SH, Wang H, Wu XH, et al. (2008). Cystic and alveolar echinococcosis: an epidemiological survey in a Tibetan population in southeast Qinghai, China. Jpn J Infect Dis, 61 (3): 242–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magambo JK, Hall C, Zeyle E, Wachira TM. (1996). Prevalence of human hydatid disease in Southern Sudan. Afr J Health Sci, 3 (4): 154–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fomda BA, Khan A, Thokar MA, Malik AA, Fazili A, Dar RA, Sharma M, Malla N. (2015). Sero-epidemiological survey of human cystic echinococcosis in Kashmir, North India. PLoS One, 10 (4): e0124813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moro PL, Garcia HH, Gonzales AE, Bonilla JJ, Verastegui M, Gilman RH. (2005). Screening for cystic echinococcosis in an endemic region of Peru using portable ultrasonography and the enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot (EITB) assay. Parasitol Res, 96 (4): 242–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baharsefat M, Massoud J, Mobedi I, Farahnak A, Rokni M. (2007). Seroepidemiology of human hydatidosis in Golestan province, Iran. Iran J Parasitol, 2 (2): 20–4. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seyyed-Tabaei SJ, Sadjjadi SM. (1999). Parasitic infection of consumed vegetables in Hamadan. Pejouhandeh, 4: 267–71.(In Persion). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yacoub AA, Bakr S, Hameed AM, Al-Thamery AA, Fartoci MJ. (2006). Seroepidemiology of selected zoonotic infections in Basra region of Iraq. East Mediterr Health J, 12 (1–2): 112–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kebede N, Mitiku A, Tilahun G. (2010). Retrospective survey of human hydatidosis in Bahir Dar, north-western Ethiopia. East Mediterr Health J, 16 (9): 937–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kandeel A, Ahmed ES, Helmy H, El Setouhy M, Craig PS, Ramzy RM. (2004). A retrospective hospital study of human cystic echinococcosis in Egypt. East Mediterr Health J, 10 (3): 349–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romig T, Dinkel A, Mackenstedt U. (2006). The present situation of echinococcosis in Europe. Parasitol Int, 55 Suppl: S187–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]