Abstract

Early autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (AHCT) with post-transplant maintenance therapy is standard of care in multiple myeloma (MM). While short-term quality of life (QOL) deterioration after AHCT is known, the long-term trajectories and symptom burden after transplantation are largely unknown. Toward this goal, a secondary analysis of QOL data of the BMT CTN 0702, a randomized controlled trial comparing outcomes of three treatment interventions after a single AHCT (N = 758), was conducted. FACT-BMT scores up to 4 years post-AHCT were analyzed. Symptom burden was studied using responses to 17 individual symptoms dichotomized as ‘none/mild’ for scores 0–2 and ‘moderate/severe’ for scores of 3 or 4. Patients with no moderate/severe symptom ratings were considered to have low symptom burden at 1-year. Mean age at enrollment was 55.5 years with 17% African Americans. Median follow-up was 6 years (range, 0.4–8.5 years). FACT-BMT scores improved between enrollment and 1-year and remained stable thereafter. Low symptom burden was reported by 27% of patients at baseline, 38% at 1-year, and 32% at 4 years post-AHCT. Predictors of low symptom burden at 1-year included low symptom burden at baseline: OR 2.7 (1.8–4.1), p < 0.0001; older age: OR 2.1 (1.3–3.2), p = 0.0007; and was related to being employed: OR 2.1 (1.4–3.2), p = 0.0004). We conclude that MM survivors who achieve disease control after AHCT have excellent recovery of FACT-BMT and subscale scores to population norms by 1-year post-transplant, though many patients continue to report moderate to severe severity in some symptoms at 1-year and beyond.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM), a plasma cell cancer seen among older adults, is a chronic, incurable malignancy associated with substantial morbidity. This cancer is characterized by an abnormal proliferation of malignant plasma cells and the production of monoclonal immunoglobulins. The clinical picture can vary, and patients are often watched until symptoms or signs of actual or impending end-organ damage occur, including anemia, renal impairment, bony lytic lesions, hypercalcemia, and more recently, biomarkers such as high free light chain ratio, bone marrow plasma cell burden, or focal lesions seen on imaging scans.1 Symptomatic MM significantly impacts health-related quality of life (QOL) compared to healthy controls.2 QOL assessments can complement response, toxicity of treatments, progression of disease, and survival assessments in evaluating the impact of therapy, but interpretation of data has been complicated by variability in study design and a lack of head-to-head treatment comparisons.3

Autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (AHCT) is an important therapeutic modality in eligible patients, with MM being the most common indication for AHCT in the United States.4 Continuous post-transplant chemotherapy with lenalidomide is the standard of care after AHCT.5 Symptomatic MM is associated with significantly diminished QOL, which can be restored with effective treatment; a systematic review of health-related QOL literature in MM patients undergoing AHCT revealed that transplantation led to an immediate deterioration in QOL and increase in symptom burden, both of which were reversed in the months thereafter.6 However, this review highlighted the paucity of prospective data on the impact of AHCT on QOL in a contemporaneous era where continuous treatment (i.e., maintenance therapy) is used as well as lack of long-term post-transplant data on QOL.

An understanding of the long-term symptom burden and recovery after AHCT can be helpful for patients, physicians, and other stakeholders to facilitate shared decision-making. The recognition of factors associated with poor symptom recovery after transplantation can guide early interventions to patients at greatest need. We thus sought to study the long-term trajectories in QOL and patient-reported symptom burden seen in MM following upfront AHCT after bortezomib-based induction and with post-transplant lenalidomide maintenance. We examined factors associated with QOL recovery and identified pre-transplant patient-, disease-, and treatment-related factors associated with post-transplant QOL. This was an ancillary study of QOL data collected on a prospective clinical trial conducted through the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN).

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Study design

The BMT CTN 0702 study (STaMINA) was a phase III trial conducted in the United Stated comparing progression-free survival and overall survival among 758 MM patients randomized to one of three treatments after AHCT: (1) second AHCT then lenalidomide maintenance (n = 247); (2) consolidation with lenalidomide/bortezomib/dexamethasone followed by lenalidomide maintenance (n = 254); or (3) lenalidomide maintenance (n = 257). The study enrolled from June 2010 through November 2013; the primary analysis revealed that all three arms had similar clinical outcomes, including in QOL scores which were reported previously.7 The objective of this ancillary study was to describe symptom burden and trajectories of recovery in MM patients after AHCT.

2.2 |. Patient-reported outcomes

Patients completed the SF-36 and FACT-BMT. All instruments were self-administered. Questionnaires were administered after randomization to treatment arm and annually until 4 years post-randomization. For nonbaseline timepoints, questionnaires completed +/− 90 days from the target date were included. This analysis focuses on the FACT-BMT measure because it includes transplant-specific symptoms that are not included in the SF-36. The 5 FACT-BMT subscale domains include Physical Well-Being (PWB), Social/Family Well-Being (SWB), Emotional Well-Being (EWB), Functional Well-Being (FWB), and BMT Subscale (BMTS). The FACT-G total was scored by summing the first four subscales (PWB, SWB, EWB, FWB) yielding a composite QOL score. The Treatment Outcome Index (TOI) was calculated by summing the PWB, FWB, and BMTS. The FACT-BMT total score was calculated by summing PWB, SWB, EWB, FWB, and BMTS scores. For all scales, the higher the score, the better the QOL. A change in 2–3 points is considered a minimal clinically important difference on the FACT-BMT.8

2.3 |. Statistical analysis

Sample size and trial details were described previously.7 Of 758 consenting patients who enrolled on study, 710 completed at least one FACT questionnaire.

Mean FACT-BMT subscale and total scores along with SD were described at each timepoint. FACT-G total score and PWB, SWB, EWB, and FWB subscale scores were compared against published norms for the general population.9 Linear mixed modeling was used to model scores over time and to make comparisons between baseline and subsequent time points. FACT-BMT Total and TOI scores were divided into quartiles at baseline and quartiles at 1 year (Q1- lowest QOL, Q4- highest QOL) to show the movement of patients between quartiles at the two timepoints using Sankey figures,10 a graphic visualization technique to show movement between states (in our case, quartiles) represented by streams, the width of which are proportional to the size of the flow. The FACT-BMT total score over time was compared between groups defined by baseline variables including age, sex, race, marital status, insurance, body mass index (BMI), education, work status prior to AHCT, urban vs rural residence, Karnofsky performance status (KPS), high risk status [defined in the protocol7 as the presence of high beta-2 microglobulin (>5.5 mg/L) or the presence of cytogenetic abnormalities including t(4;14), t(14;20), t(14;16), deletion (17p) detected by FISH or standard cytogenetics, deletion 13 detected by standard cytogenetics only or aneuploidy], comorbidity index (HCT-CI), lines of therapy, disease status at baseline. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for continuous variables, and the chi-square test was used for categorical variables.

The following symptoms obtained from the FACT-BMT were considered individually: general QOL, fatigue, malaise, pain, sleep, nausea, sadness, nervousness, poor appetite, memory, frequent infections, blurry vision, taste changes, tremors, shortness of breath, skin problems, and bowel problems. We considered patients reporting scores 0–2 to have no or mild symptoms and scores of 3–4 as moderate or severe symptoms, at baseline, 1 year and 4 years. The McNemar’s test was used to compare the number of patients with moderate or severe symptoms at baseline and 1 year. Patients with no 3–4 responses among all 17 individual symptoms were considered to have low symptom burden and those with any 3–4 responses as high symptom burden. A logistic regression model was fitted to determine the variables at randomization associated with low symptom burden at 1 year.

All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All statistical tests were two-sided; only results with p-value <.01 were considered significant due to multiple testing.

3 |. RESULTS

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics; 454 (60%) were male, with a mean age of 55.5 (±8.4) years, with 75% white, 17% African American, and 7.5% other race. Most patients had good functional status with Karnofsky score 90% or higher in 69% of patients; 36% had an HCT-CI of 0. Many patients were overweight (BMI 25–29.9 in 34.9%) or obese (BMI ≥30 in 45.1%). High-risk MM was seen in 36% of patients. The median follow-up of survivors was 6 years (range, 0.4–8.5 years). A total of 188 did not complete the FACT-BMT at 1 year, including 11 who died prior to 1 year and 61 who did not complete due to relapsed disease and discontinuing from the study. Among the remaining 116 nonresponders who remained on study, baseline characteristics were compared and not found to be different with those who completed assessments at 1 year (N = 524), Table S1.

TABLE 1.

Cohort characteristics

| Baseline characteristics | Number (N = 758) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Mean age at enrollment (±SD) | 55.5 ± 8.4 |

| Gender, Female | 304 (40.1) |

| Race | |

| White | 589 (79.1) |

| African American | 133 (17.9) |

| Othera | 23 (3.1) |

| Missing | 13 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 45 (6.2) |

| Not hispanic | 683 (93.8) |

| Karnofsky score | |

| ≥ 90 | 523 (69) |

| <90 | 235 (31) |

| HCT-CI | |

| 0 | 265 (35.5) |

| 1 | 116 (15.5) |

| 2 | 127 (17) |

| 3/+ | 238 (31.9) |

| Missing | 12 |

| BMI | |

| <18.5 | 4 (0.5) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 146 (19.4) |

| 25–29.9 | 263 (34.9) |

| 30–34.9 | 193 (25.6) |

| ≥35 | 147 (19.5) |

| Missing | 5 |

| Socioeconomic status variables | |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 169 (23.4) |

| Married | 552 (76.6) |

| Missing | 37 |

| Insurance | |

| Private | 600 (84.4) |

| Public | 111 (15.6) |

| Missing | 47 |

| Education | |

| High school or lower | 208 (40.8) |

| College | 104 (20.4) |

| Graduate school | 198 (38.8) |

| Missing | 248 |

| Employment | |

| Employed (Full-time or Part-time) | 299 (47.2) |

| Not employed (unemployed, medical disability, retired) | 334 (52.8) |

| Missing | 125 |

| Household income | |

| <$55 K | 359 (48.5) |

| ≥ $55 K | 381 (51.5) |

| Missing | 18 |

| Urban/rural | |

| Urban | 710 (95) |

| Rural | 37 (5) |

| Missing | 11 |

| Disease-related variables | |

| Disease risk | |

| High risk | 271 (35.9) |

| Standard risk | 484 (64.1) |

| Missing | 3 |

| Serum creatinine prior to transplant, mean ± SD | 0.9 ± 0.3 |

| Missing | 8 |

| Number of lines of treatment | |

| 1 | 641 (85.1) |

| ≥2 | 112 (14.9) |

| Missing | 5 |

| Initial therapy | |

| VRD | 420 (55.8) |

| VCD | 108 (14.3) |

| RD/VD | 167 (20.1) |

| Other | 58 (7.7) |

| Missing | 5 |

| Disease status prior to transplant | |

| sCR/CR/VGPR | 356 (46.9) |

| PR | 337 (44.5) |

| SD/Progression | 58 (7.7) |

| Not evaluable | 7 (0.9) |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant, mean ± SD | 7.9 ± 7.5 |

| Missing | 12 |

| Median follow up of survivors, years | 6 (0.4–8.5) |

Other race category: Asian (n = 20), American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 2), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (n = 1).

3.1 |. Trajectories of QOL over time

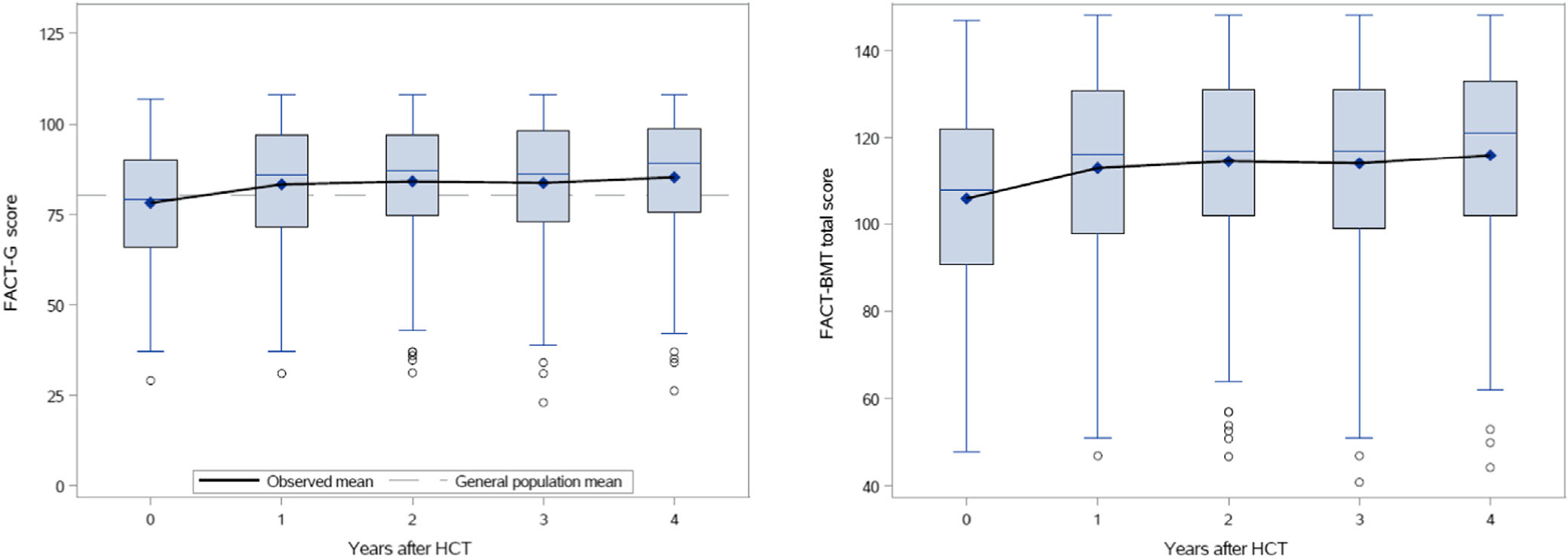

The FACT-BMT subscale and total scores are shown in Table 2. Compared to normative data for the general U.S. adult population, scores for the subscales of PWB, EWB, FWB were lower among patients with MM at baseline as was the FACT-G total score. By 1-year post-transplant, the PWB subscale score improved to close to the US norm and remained stable through year four. The EWB subscale showed a similar pattern of improvement. The FWB subscale scores improved above the US norm (though not with a clinically meaningful difference) and remained higher throughout the study period. In contrast, the SWB subscale score was higher at baseline for patients (23.7 ± 6.8) compared to the U.S. adult population (19.1 ± 4.3) and remained so over the four-year study period. The FACT-G total score (a composite of the PWB, SWB, EWB, and FWB) also showed a similar pattern with a mean score of 83.2 ± 16.4 at 1-year and 85.2 ± 16.5 at 4-year post-transplant compared to the US adult population score of 80.1 ± 18.1, a clinically meaningful difference. Table S2 shows a comparison of score change over time. This demonstrated clinically significant improvement in the PWB and FWB subscales and in the FACT-G, BMTS, FACT-BMT, and FACT-BMT TOI total scores between baseline and 1-year post-AHCT. While the subscales of SWB and EWB showed a statistically significant decrement between baseline and 1-year, the difference in score change was <1 point, which was not clinically meaningful. Scores remained stable between the 1- and 4-year timepoints. While there was a statistically significant increase in BMTS score from 1-year to 4-year, the change in score was <1 point. Figure 1 shows the trajectories of change in the FACT-G and FACT-BMT score over time.

TABLE 2.

Change in QOL scores over time

| Norma | Baseline (N = 709) | 1 year (N = 546) | 2 year (N = 459) | 3 year (N = 367) | 4 year (N = 263) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| Physical well-being | 22.7 ± 5.4 | 19.3 ± 5.9 | 21.6 ± 5.3 | 22.0 ± 4.9 | 21.6 ± 5.3 | 22.0 ± 4.8 |

| Social/family well-being | 19.1 ± 6.8 | 23.7 ± 4.3 | 22.8 ± 4.8 | 22.5 ± 5.3 | 22.6 ± 5.1 | 22.9 ± 5.5 |

| Emotional well-being | 19.9 ± 4.8 | 18.6 ± 3.9 | 19.4 ± 3.9 | 19.6 ± 3.7 | 19.4 ± 3.9 | 19.8 ± 3.8 |

| Functional well-being | 18.5 ± 6.8 | 16.4 ± 6.3 | 19.4 ± 6.2 | 19.9 ± 6.0 | 19.9 ± 6.1 | 20.4 ± 6.0 |

| FACT-G total | 80.1 ± 18.1 | 78.1 ± 15.5 | 83.2 ± 16.4 | 84.0 ± 16.0 | 83.6 ± 16.6 | 85.2 ± 16.5 |

| BMTS | N/A | 27.8 ± 5.6 | 29.7 ± 5.6 | 30.5 ± 5.3 | 30.3 ± 5.3 | 30.7 ± 5.6 |

| FACT-BMT total | N/A | 106.0 ± 20.0 | 112.9 ± 21.2 | 114.5 ± 20.3 | 114.0 ± 21.0 | 115.9 ± 21.2 |

| FACT-BMT TOI | N/A | 63.5 ± 15.5 | 70.7 ± 15.4 | 72.4 ± 14.4 | 71.9 ± 14.9 | 73.2 ± 14.9 |

Mean Scores representing Normative Data of General U.S. Adult Population.9

FIGURE 1.

(A) FACT-G total score change over time. (B) FACT-BMT total score change over time

3.2 |. Change in scores between baseline and 1-year

Overall, composite scores increased at 1-year post-transplant compared to baseline. Figure 2 shows the details of patients moving between quartiles based on FACT-BMT scores: while 62% of patients who started in quartile 4 remained in quartile 4 at 1-year and 64% of patients who started in quartile 1 remained in quartile 1 at 1-year, the whole range shifted upwards, representing overall score improvement. Only 23 patients had worsened scores between baseline and 1 year, including 11 patients in baseline Q4 that moved to Q2/Q1 at 1-year and 13 patients from Q3 at baseline who moved to Q1 at 1-year. Only 64 patients moved >1 quartile in total. While most patients in quartiles 2 and 3 also stayed within their quartile at 1-year, there was more movement from these quartiles toward other groups at 1-year.

FIGURE 2.

Change in FACT-BMT score between baseline and 1-year post-transplant. Q4 represents the highest QOL score quartile and Q1 represents the lowest QOL score quartile

Table S3 shows baseline characteristics by baseline score quartiles; 28% of patients with KPS ≥90 were in the highest quartile (Q4) while only 20% were in the lowest (Q1) and 16% of patients with KPS <90 were in Q4 awhile 40% were in Q1 (p < .001). Employment status was also strongly associated with baseline scores: 28% of working patients were in the highest quartile and only 18% in the lowest; only 20% of patients who were not working were in the highest quartile while 34% were in the lowest (p < .001). While HCT-CI also appeared to correlate with baseline score quartiles (p < .032), this did not meet our threshold for significance. There were no differences by sex, age, race, or other baseline patient- and disease-related characteristics. Table S4 shows comparison in baseline characteristics among patients who had worsening in FACT Total score by 3 points or more with those that did not. No differences were seen at the 0.01 level of significance.

3.3 |. Patient-reported symptom burden

At baseline, 191 (27%) of patients reported scores in the low symptom burden range (0–2) with 503 (73%) having at least one high symptom burden score (3, 4). At 1-year, 204 (38%) of patients had low symptom burden and 337 (62%) had high symptom burden. At 4-year post-transplant, there was little change from 1-year, with 94 (36%) having low symptom burden scores and 169 (64%) having at least one high symptom burden score. General QOL showed improvement at both timepoints compared to baseline. Other symptoms that showed significant improvement from baseline to 1-year included fatigue, malaise, pain, sleep, nervousness, poor appetite, taste changes, and nausea. Symptoms that remained stable included memory changes, sadness, blurry vision, tremors, and shortness of breath. Last, symptoms of bowel problems and frequent infections worsened over time, while skin problems worsened between baseline and 1-year but improved between 1-year and 4-year post-transplant. Further details are shown in Table S5.

On logistic regression, 3 baseline patient-related factors were significantly associated with low symptom burden at 1-year (defined as no patient-reported symptom with a score of 3 or 4). Low symptom burden at baseline was associated with OR 2.71 (1.80–4.09); p-value <.0001, age of 62 years or older was associated with OR 2.08 (1.34–3.22); p-value <.0001, and working full-time or part-time prior to HCT was associated with OR 2.13 (1.40–3.23); p-value .004 of low symptom burden at 1 year. Higher income at baseline was also associated with lower symptom burden but did not meet the study criteria for statistical significance (p-value .023). Table S6 shows the detailed results of the logistic regression analysis.

4 |. DISCUSSION

We describe the trajectories of QOL recovery, symptom burden, and risk factors for poor symptom recovery following AHCT in MM patients treated on a prospective clinical trial studying upfront AHCT. Our analysis, which provides a snapshot of QOL and symptom burden up to 4 years post-transplant, is one of the first studies to provide long-term data on symptom recovery among MM patients who are on maintenance therapy. It has been well studied that QOL recovers early after AHCT within 3–6 months. Ebraheem et al. recently reported on symptom burden and trajectories in the first year among MM patients who underwent AHCT using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System using an administrative healthcare data set based in Ontario, Canada.11 These results showed short-term deterioration at 1 month, followed by improvement as early as 3 months post-transplant to scores that were better than pre-transplant baseline and stability through the end of the year.11 Using data from the Connect MM Registry, Abonour et al. showed no significant difference in change from maintenance therapy with the EQ-5D overall index, BPI, and FACT-MM scales.12 Our results show that while the trajectories of QOL recovery mirror those shown by these contemporaneous studies, despite overall score recovery at one-year, with general stability up to 4 years post-transplant, patients continue to experience symptom burden. Thus, our results indicate that there is need for symptom management in long-term survivors even when QOL score improvement and stability is noted.

In prior work on the time trajectory to recovery after AHCT in MM, a short-term deterioration in QOL has been well documented which recovers by 3–6months.6,13 Whether patients obtain superior QOL in the long-term has not been clear but suggested in some studies.14,15 Roussel, et al. studied QOL recovery in patients with newly diagnosed MM treated with induction chemotherapy with lenalidomide/bortezomib/dexamethasone followed by AHCT or induction alone, with both groups receiving lenalidomide maintenance for 1 year.16 This study had a similar mean age at baseline (56.7 years) compared to the STaMINA trial. QOL which was assessed using EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-MY20 showed transient worsening in QOL immediately following transplantation with recovery thereafter. The analysis showed that both arms had meaningful and significant recovery in QOL outweighing the adverse effects of treatment. Similar to our analysis, the IFM 2009 QOL analysis reflected improved QOL trajectories among patients who stayed in response and on study. Different from the STaMINA trial is the shorter time of maintenance lenalidomide. Our analysis showed that overall QOL trajectories are similar to those described by Roussel, et al. and remain stable with longer time on maintenance. Further, we provide a deeper analysis of individual symptom burden recovery and predictors of worse symptom burden recovery. We can document that subscale and total scores are very close to the general population norms by 1 year. The SWB subscale score was higher than the general population norm prior to AHCT and decreases by 1-year post-AHCT though it remained higher compared to the norm. High SWB scores are well documented in the HCT setting8 and likely reflect the need for patients to have a high social support structure to undergo transplant and, additionally, in the current study, a clinical trial. Finally, the FWB subscale score also improved to higher than the population norm by 1 year and remained higher than the population norm at 4 years after AHCT. This shows that patients with disease control have excellent functional status recovery.

We sought to study whether patient-reported outcomes change over time for MM patients. We focused this analysis on the changes occurring between baseline and 1 year as there was no significant change in scores thereafter. We found that overall scores improved between baseline and 1-year. When grouped into quartiles, 52% of patients remained in the same quartile between baseline to 1-year post-AHCT. One quartile change was seen in 36%, though the actual score at 1 year for this group remained similar to the baseline score. Only 64 (12.5%) patients changed 2 or 3 quartiles and were those where the score changed significantly compared to baseline. When assessing covariates associated with low QOL at baseline, no disease-related factors was identified. Two patient-related factors, KPS and HCT-CI were associated with baseline QOL, though HCT-CI was not statistically significant at the 0.01 threshold. Of various SES factors studied, employment status had a strong association with baseline QOL. No other SES factors (e.g., education, income, insurance, rural/urban residence) were associated with baseline QOL.

When assessing patient-reported symptom burden at baseline, 1-year, and 4-year post-transplant, we were surprised to see that despite excellent subscale and total scores on the FACT-BMT, a significant proportion of patients continued to have symptoms and concerns that were affecting them ‘very much’ or ‘quite a bit’. Although most symptoms improved from baseline to 1 year, 3 symptoms in particular showed worsening between baseline to 1 year: frequent infections (which worsened from 2% to 9% in the 3–4 range), bowel problems (9%–13%), and skin problems (4%–9%). Anecdotally, these may represent the effect of ongoing maintenance with lenalidomide. The distribution of symptoms highlight that a significant proportion of patients continue to have a high symptom burden. Baseline symptom burden was a predictor of 1-year symptom burden and is consistent with other studies in the allogeneic HCT setting have also reported that baseline FACT-BMT is associated with subsequent concerns, including the risk of post-transplant regret.17 Interestingly, older age was associated with higher odds of having low symptom burden at 1 year in our study. In the allogeneic HCT setting, similar findings have been reported with adults ≥60 years with higher FACT-BMT scores compared to younger patients.18 This likely underscores the highly selected patient population on a transplant clinical trial, particularly among older adults. Employment status was also significantly associated with 1 year symptom burden after transplant and known predictors of QOL in other oncologic settings.19

We acknowledge important limitations of our study including representativeness. MM is a disease of older adults with a median age at diagnosis of 69 years in the United States. Though transplant has been shown to be safe in older adults above the age of 70 years,20 older adults are not well represented in transplant clinical trials. In the current study, the mean age was 55.5 years, representing a much younger group of MM patients enrolled on the study, which had an upper limit of 65 years for study enrollment. On the other hand, African Americans, who are at higher risk of MM, are well represented. In prior analyses, the enrollment fraction of African American MM patients in clinical trials was 6%.21 QOL trajectories may differ among MM survivors not treated on a clinical trial. Thus, these findings need to be further corroborated and collected as part of meaningful outcomes in real-world population series. Last, our data show more missing QOL data with every subsequent year. While some of the missing QOL completion was due to patients coming off trial with relapse/progression, a missed opportunity for not capturing all assessments in patients who remained on the study was evident. We did not identify any differences in baseline characteristics of responders versus nonresponders. Consequently, our results represent patients who remained in response and completed QOL data. Our next steps include further study of symptom burden- studying patient- and symptom- clusters along with correlative cytokine changes which may correlate with persistent high symptom burden.

In conclusion, the results of this ancillary study to the BMT CTN 0702 clinical trial provide an understanding of the long-term trajectories of QOL and symptom burden in survivors with MM up to 4 years after upfront AHCT. Among patients who achieve disease control, overall QOL scores recover to population norms by 1-year post-AHCT and remain stable thereafter, though many patients continue to report moderate to severe severity in some symptoms at 1-year post-AHCT and beyond. As the role of AHCT in the treatment of MM continues to evolve with therapies such as CAR-T being compared to AHCT, these studies should evaluate treatments not just based on efficacy and toxicity, but QOL and PROs (symptom burden, including financial toxicity) as well. For clinical utility, tracking specific symptoms can complement the overall FACT-BMT scores. These data provide preliminary work to develop a PRO-based intervention focusing on symptom burden in survivors with MM after AHCT.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This ancillary study was funded by a Froedtert & MCW Cancer Center grant (project 3379013). Dr. D’Souza is supported by K23 HL141445. The BMT CTN 0702 was supported by Grant No. U10HL069294 to the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Cancer Institute; by Celgene Corporation and Millennium (Takeda) Pharmaceuticals; and by The Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group–American College of Radiology Imaging Network Cancer Research Group, and SWOG.

Funding information

Froedtert & MCW Cancer Center, Grant/Award Number: 3379013; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Grant/Award Number: K23 HL141445; National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Number: U10HL069294

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the funding parties.

These results were presented in part as an oral presentation at the Virtual ISOQOL 2021 Annual Conference.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of the article at the publisher’s website.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are publicly available at BioLINCC: Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) A Trial of Single Autologous Transplant With or Without Consolidation Therapy Versus Tandem Autologous Transplant With Lenalidomide Maintenance for Patients With Multiple Myeloma (0702) (nih.gov).

REFERENCES

- 1.Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e538–e548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gulbrandsen N, Hjermstad MJ, Wisloff F, et al. Interpretation of quality of life scores in multiple myeloma by comparison with a reference population and assessment of the clinical importance of score differences. Eur J Haematol. 2004;72:172–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonneveld P, Verelst SG, Lewis P, et al. Review of health-related quality of life data in multiple myeloma patients treated with novel agents. Leukemia. 2013;27:1959–1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Souza A, Fretham C, Lee SJ, et al. Current use of and trends in hematopoietic cell transplantation in the United States. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26:e177–e182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCarthy PL, Holstein SA, Petrucci MT, et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3279–3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakraborty R, Hamilton BK, Hashmi SK, Kumar SK, Majhail NS. Health-related quality of life after autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24: 1546–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stadtmauer EA, Pasquini MC, Blackwell B, et al. Autologous transplantation, consolidation, and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma: results of the BMT CTN 0702 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37: 589–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McQuellon RP, Russell GB, Cella DF, et al. Quality of life measurement in bone marrow transplantation: development of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT) scale. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:357–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brucker PS, Yost K, Cashy J, Webster K, Cella D. General population and cancer patient norms for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G). Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:192–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. https://sankeyMATIC.com/.

- 11.Ebraheem MS, Seow H, Balitsky AK, et al. Trajectory of symptoms in patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplant for multiple myeloma: a population-based cohort study of patient-reported outcomes. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21:e714–e721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abonour R, Wagner L, Durie BGM, et al. Impact of post-transplantation maintenance therapy on health-related quality of life in patients with multiple myeloma: data from the Connect(R) MM Registry. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:2425–2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campagnaro E, Saliba R, Giralt S, et al. Symptom burden after autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Cancer. 2008; 112:1617–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khalafallah A, McDonnell K, Dawar HU, et al. Quality of life assessment in multiple myeloma patients undergoing dose-reduced tandem autologous stem cell transplantation. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2011;3:e2011057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hensel M, Egerer G, Schneeweiss A, Goldschmidt H, Ho AD. Quality of life and rehabilitation in social and professional life after autologous stem cell transplantation. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roussel M, Hebraud B, Hulin C, et al. Health-related quality of life results from the IFM 2009 trial: treatment with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone in transplant-eligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61: 1323–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cusatis RN, Tecca HR, D’Souza A, et al. Prevalence of decisional regret among patients who underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and associations with quality of life and clinical outcomes. Cancer. 2020;126:2679–2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton BK, Rybicki L, Dabney J, et al. Quality of life and outcomes in patients60 years of age after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:1426–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roick J, Danker H, Kersting A, et al. The association of socioeconomic status with quality of life in cancer patients over a 6-month period using individual growth models. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27: 3347–3355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munshi PN, Vesole D, Jurczyszyn A, et al. Age no bar: a CIBMTR analysis of elderly patients undergoing autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Cancer. 2020;126:5077–5087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duma N, Azam T, Riaz IB, Gonzalez-Velez M, Ailawadhi S, Go R. Representation of minorities and elderly patients in multiple myeloma clinical trials. Oncologist. 2018;23:1076–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are publicly available at BioLINCC: Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) A Trial of Single Autologous Transplant With or Without Consolidation Therapy Versus Tandem Autologous Transplant With Lenalidomide Maintenance for Patients With Multiple Myeloma (0702) (nih.gov).