Abstract

Introduction:

There is reason to believe that introversion may relate to different patterns of negative and positive experiences in everyday life (“hassles” and “uplifts”), but there is little evidence for this based on reports made in daily life as events occur. We thus extend the literature by using data from ecological momentary assessments to examine whether introversion is associated with either the frequency or intensity of hassles and uplifts.

Method:

Participants (N=242) were community-dwelling adults (63% Black, 24% Hispanic; ages 25–65; 65% women) who completed baseline measures of personality and mental health, followed by reports of hassles and uplifts 5x/day for 14 days. We present associations between introversion and hassles/uplifts both with and without controlling for mood-related factors (neuroticism, recent symptoms of depression and anxiety).

Results:

Introversion was associated with reporting less frequent and less enjoyable uplifts, but not with overall hassle frequency or unpleasantness; exploratory analyses suggest associations with specific types of hassles.

Conclusion:

Our results expand understanding of the role of introversion in everyday experiences, suggesting an overall association between introversion and uplifts (but not hassles, broadly) in daily life. Better understanding such connections may inform future research to determine mechanisms by which introversion relates to health.

Keywords: UPLIFTS, HASSLES, INTROVERSION, EMA, STRESS, MENTAL HEALTH

Introversion-extraversion1, a personality trait included in most major models of personality across history, broadly encompasses characteristics related to social tendencies and positive emotions (Wilt & Revelle, 2016). Introversion is reduced expression of (or lack of) consistent extraverted characteristics, such as tending to be assertive, impulsive, gregarious, and socially warm, to experience positive emotions, to seek and enjoy excitement, and to be active and busy (Ashton & Lee, 2001; Eysenck, 1947/1998; Goldberg, 1990; McCrae & Costa, 2008). Early laboratory research, motivated by proposed underlying differences in autonomic nervous system functioning (Eysenck, 1963) — a system which is innately linked to the physiological stress response — suggests that introversion is associated with maladaptive responses to stressful, negative stimuli (e.g., Pascalis et al., 2016; Schneider et al., 2011; Xin et al., 2017). More recent research has also focused on connections between extraversion and “positive” phenomena, particularly positive emotions, in keeping with contemporary models of introversion-extraversion and theories linking extraversion to reward-sensitivity (Wilt & Revelle, 2008). Together, this research and theory suggests that introversion-extraversion, broadly defined, could be associated with both stressful and positive experiences. However, beyond laboratory research, most of the extant literature examining connections between introversion and daily stressors (“hassles”) and positive experiences (“uplifts”) is based on retrospective reports and has been unable to differentiate important characteristics of the experiences (such as their frequency and intensity); combined with conflicting findings, it is currently unclear whether and how introversion-extraversion is associated with these everyday experiences.

Importantly, uplifts and hassles not only make up the topography of daily life (i.e., everyday highs and lows), but these experiences (and individual differences in them) also have implications for health and well-being. For example, higher frequency and intensity of hassles has been associated with greater disease prevalence, more illness and mental-health-related symptoms, worse subjective health, and increased risk of mortality (e.g., Bolger & Zuckerman, 1995; Charles et al., 2013; Chiang et al., 2017; Delongis et al., 1982; Kanner et al., 1981; Stephens & Pugmire, 2008; for review see Almeida et al., 2011), which potentially results from the cumulative wear-and-tear on physiological and psychological systems associated with chronic stress (Charles et al., 2013; Smyth, Zawadzki, & Gerin, 2013; Wen, 1998). Experiencing more uplifts has been linked with better self-rated and objective measures of physical health, fewer mental health symptoms, and greater life satisfaction and hedonic well-being (Kanner et al., 1987; Lyons & Chamberlain, 1994; Mayberry & Graham, 2001; Pressman et al., 2009; Sin et al., 2015; Sin & Almeida, 2018; Stephens & Pugmire, 2008), perhaps in part because uplifts (and associated positive emotions) may buffer the effects of hassles and other stressors (Ong et al., 2004, 2006; Ong & Allaire, 2005; Pressman et al., 2009; Sin & Almeida, 2018). Thus, it would be valuable to have a better understanding of how hassles and uplifts vary by introversion-extraversion level, because the daily wear-and-tear related to having fewer (or less uplifting) positive experiences and more (or more unpleasant) negative experiences may be a mechanism whereby introversion is related to poorer health. In the sections that follow, we will discuss current evidence in these domains (i.e., introversion and daily experiences), key methodological considerations, and how the current analyses extend and refine previous foundational research.

Negative and Stressful Experiences in Daily Life

Early research examining the relationship between introversion and negative and stressful experiences has often done so in decontextualized settings with select stimuli. In lab settings, for example, introverts have generally demonstrated more physiological and/or affective reactivity to stressors compared to extraverts (Evans et al., 2016; Pascalis et al., 2016; Schneider et al., 2011; Tyrka et al., 2007; Wilson et al., 2015; Xin et al., 2017; Yamaoka, 2014). Vignette studies, on the other hand, have suggested that introversion may be related to other components of the stress experience besides reactivity (see “Transactional Model of Stress and Coping” [Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, p. 19–20]), such as by introverts having less optimism regarding their coping abilities (Hemenover & Dienstbier, 1996) and appraising situations as more stressful (Gallagher, 1990; Knapp, 2018). Such studies help demonstrate that introverts respond differently than extraverts to the same stressor; however, they do not establish how individuals respond in daily life. For example, it is possible that introverts experience more stressors in addition to being likely to react more strongly and/or cope more poorly with them. Additionally, these studies often focus on limited domains of stress, such as social performance-related stress (e.g., the Trier Social Stress Test [see Frisch et al., 2015]), which may represent a particularly vulnerable area for introverts.

Another approach to looking at stressful or negative experiences in the context of introversion has been to ask participants to retrospectively report on naturally occurring experiences outside of the lab; often referred to as stressors, we specifically refer to these reported experiences as “hassles” in this manuscript to distinguish them from lab-based and hypothetical stressors. While somewhat more ecologically valid, results from studies using retrospective reports of hassles have been mixed: five studies reported null findings (Davis et al., 2006; Leger et al., 2016; Longua et al., 2009; Zautra et al., 1991, 2005), two reported small, negative associations with introversion (Luo, 1994; Swickert et al., 2002), and six reported small, positive associations (Belsky et al., 1995; Flett et al., 2012; Hart et al., 1994; Hutchinson & Williams, 2007; Vollrath, 2000; Wearing & Hart, 1996). These inconsistencies could be due to real but small effect sizes as well as variation in study design. For example, previous studies have often interchangeably operationalized hassles using different aspects of the experiences (i.e., frequency versus intensity2) without comment on this distinction. We have attempted to classify previous studies on the basis of whether they examined hassle frequency versus intensity (shown in Supplemental Table 1), and this distinction does appear to matter. Of those studies most clearly examining frequency, there was no evidence of an association with introversion (Davis et al., 2006; Leger et al., 2016; Zautra et al., 1991, 2005). In contrast, studies using intensity constructs have reported a mix of null and significant findings (with associations in both directions [Flett et al., 2012; Hart et al., 1994; Hutchinson & Williams, 2007; Longua et al., 2009; Luo, 1994; Swickert et al., 2002; Vollrath, 2000; Wearing & Hart, 1996]).

An additional source of variation in previous studies’ designs may be found in the variety of scales used to measure hassles. In thirteen studies, nine different scales were used, which vary in terms of whether specific domains (such as parenting, police work, or interpersonal content) are assessed versus hassles broadly across multiple contexts. Even when multiple domains were included in the scale, analytic strategies varied by whether specific associations between introversion and domains of hassles were presented in addition to overall associations with hassles. As there is some evidence that associations between hassles and introversion vary based on the specific hassle domain (Hart et al., 1994; Vollrath, 2000; Wearing & Hart, 1996), variation in this aspect of methodology may help explain inconsistency between studies. A breakdown of the hassle studies’ methods and results are included in Supplemental Table 1.

One common methodological factor in all of the retrospective studies reviewed above is that they solicit recall of experiences that span a substantial amount of time, usually over the past month (although some ask as often as once per day and others ask to recall over the past six months). Recall of minor (or even more significant) experiences becomes difficult as time passes, and even experiences over the day are unlikely to be recalled in any detail at the end of the day (Stone & Shiffman, 2010). Retrospective self-reports can also be biased by general beliefs about the self as well as current states, such as emotions; moreover, some evidence suggests introversion-extraversion may be related to specific attentional and memory biases that could further influence retrospective reports (Amin et al., 2004; Barrett, 1997; Fishman et al., 2010; Hoerger et al., 2016; Mill et al., 2016; Raffard et al., 2017; Zelenski et al., 2013).

Positive and Uplifting Experiences in Daily Life

In addition to research linking introversion with hassles, some research has examined a link between introversion with uplifts, although there are fewer studies that include or focus on uplifts compared to hassles. However, among these studies, introversion has been consistently linked to uplifts. All of ten studies reported that introversion was associated with fewer and/or less “uplifting” uplifts (Davis et al., 2006; Hart et al., 1994, 1995; Klaiber et al., 2021; Longua et al., 2009; Mayberry et al., 2006; Wearing & Hart, 1996; Zautra et al., 1991, 2005). A similar pattern was seen in a study where introverted participants reported lower combined enjoyment and self-efficacy for daily activities (Komulainen et al., 2014), which provides additional evidence that introverts tend to report less enjoyable experiences and/or perceive them that way. Importantly, however, studies linking introversion with uplifts tend to have similar limitations as retrospective studies linking introversion and hassles, including issues with the operationalization of uplifts (i.e., frequency versus intensity constructs) and recall-related biases.

The Current Research

In the current research, we examine whether trait introversion is associated with hassles and uplifts from intensive self-report data collected in daily life. This research builds on previous studies of introversion and daily experiences in that it uses data from ecological momentary assessment (EMA) that captured near-real-time reports of the frequency and intensity of daily experiences, enabling the differentiation of these features while also minimizing recall and increasing ecological validity. Additionally, in the present research uplifts and hassles were reported in an open-ended format where any experience could be reported, as compared to most previous approaches that have used specific stressor stimuli (lab/vignette studies) or a finite checklist for reporting (retrospective studies). Thus, responses are not limited to specific domains of life in the present study, which may increase the ability to detect introversion-relevant differences in how individuals perceive or navigate daily experiences. Given that other mood-related constructs may overlap with introversion as well as experiences of daily hassles and uplifts, we present analyses that control for neuroticism, which has been robustly linked with stress reactivity and negative experiences broadly, and symptoms of depression and anxiety (Bolger & Zuckerman, 1995; D’Angelo & Wiekzbicki, 2003; Jylhä & Isometsä, 2006; Kim et al., 2016; Peeters et al., 2003; Ruscio et al., 2015; Suls & Martin, 2005).

We hypothesized that introversion would be associated with both fewer and less enjoyable uplifts, given the findings of the previous retrospective work, and because this association would be in line with definitional characteristics of introversion-extraversion. For example, extraverts may tend to have more uplifts than introverts because extraverts’ social and adventurous nature may lead them to situations with more positive, uplifting, and exhilarating experiences in addition to their baseline tendency to be cheerful and optimistic (thus leading to further enjoyment of these experiences). In contrast, we hypothesized that introversion would not be related to the overall frequency of hassles but may be related to the overall perceived intensity of hassles, given previous findings from lab and vignette studies suggesting that introverts may be more reactive to stress and may perceive hassles as more threatening.

Methods

Participants

Data for the current study come from the first wave of the Effects of Stress on Cognitive Aging, Physiology, and Emotion (ESCAPE) project (described in Scott et al., 2015)3, the broader goals of which are to characterize psychological and physiological stress-related processes related to downstream cognitive aging. Adults (N=249) aged 25 to 65 were systematically recruited from a housing development in the Bronx, New York, primarily via New York City Registered Voter lists. The broader ESCAPE protocol was approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University ethical review board. All participants provided consent and were compensated up to $160 USD for full participation at baseline (Scott et al., 2015).To be included in the ESCAPE study, all participants were required to speak English, and be ambulatory and without visual impairment that would interfere with study participation.

With regard to the current, secondary analyses, five participants did not complete EMA assessments, and three others were non-compliant with the EMA protocol (described in more detail below) and were subsequently excluded. Thus, the final sample consisted of 242 participants (157 women, 85 men; additional gender identity options provided but not reported) who were racially and ethnically diverse, with the majority of participants identifying as non-Hispanic Black (63.64%) or Hispanic (23.56%). The average age of participants was 46.31 (SD=11.04) years. Additional demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 46.31 (11.04) |

| Female | 157 (64.88%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | |

| Black | 154 (63.64%) |

| White | 21 (8.68%) |

| Othera | 10 (4.13%) |

| Hispanic | |

| Black | 12 (4.96%) |

| White | 45 (18.60%) |

| Employment | |

| Employed | 122 (50.83%) |

| Unemployed (seeking employment) | 66 (27.50%) |

| Retired | 32 (13.33%) |

| Unemployed (not seeking employment) | 20 (8.33%) |

| Some college or more | 183 (75.62%) |

| Married/Cohabitating | 98 (40.66) |

| Household income (≥40K) | 114 (47.50) |

Note. N = 242. One participant was missing age and two additional participants were missing information on employment, income, and/or marital status. Twenty-two participants opted not to provide household income, but these participants did not differ from the rest of the sample on any other key study or demographic variable.

The “other” category included Asian, American Indian, and Alaska Native participants.

Procedures

As part of the larger ESCAPE study, participants took part in assessments of cognitive function in a clinic, and, approximately two weeks later, further in-clinic assessments that included a blood draw. Prior to in-clinic visits, participants were mailed survey packets to assess demographic and psychosocial and behavioral factors. This baseline survey included factors used in the present research: self-reported mental and physical health and Big Five personality traits. Survey packets were returned during the first in-clinic visit, which was also used to collect informed consent and train participants on how to complete assessments on study smartphones. A “run-in” phase of at least three days was utilized to allow for practice with the smartphones outside of the clinic and to assess compliance with the EMA protocol (completing ≥ 80% of assessments was necessary for participation in the full EMA portion of the study).

EMA smartphone protocol.

As part of a larger protocol that involved self-initiated morning and evening assessments, participants were instructed to complete assessments in response to audible notifications (“beeps”) sent to study-provided smartphones five times per day for 14 days (i.e., up to 70 scheduled assessments). These assessments included queries about hassles and uplifts that were used in the present research. Beeped assessments were sent at quasi-random intervals (to prevent anticipation of assessments) tailored to participants’ typical sleep/wake schedule to ensure coverage of the waking day (completed every 3.2 hours on average). Participants could access and complete the surveys at all times, regardless of whether they were prompted. However, assessments completed at other times were not used in the current research because the EMA protocol was designed to assess a semi-random selection of moments. Participant self-selection of moments outside of this schedule may be linked to confounding individual differences or external factors that could bias reporting.

Three participants completed less than 20% of assessments and were excluded from analyses (McCabe et al., 2011). The final set of participants completed 80.90% (SD=18.96) of assessments across 13.26 days (SD=1.54) on average. Non-compliant participants did not differ from compliant participants on any key study or demographic variables.

Measures

Introversion.

The current research used a ten-item measure of introversion-extraversion from the International Personality Item Pool (a publicly available bank of personality inventory items), many of which were characterized by Goldberg and colleagues (1999). Items from the IPIP are short phrases reflecting typical characteristics and behaviors that were endorsed by participants on a scale from one to five (i.e., very inaccurate to very accurate). Item scores were averaged to create a final score with higher scores representing higher levels of introversion (and, conversely, lower levels of extraversion). The introversion scale exhibited good internal consistency in this sample (α = .79). The full items may be found online: https://osf.io/t8pcm/ (DeMeo, 2021).

Hassles.

Items from the Daily Inventory of Stressful Events (Almeida et al., 2002) were adapted from a phone interview format (Ryff et al., 2017) to assess hassles via smartphone EMA assessments. Participants reported whether anything stressful had occurred since the last assessment, including “…any event, even a minor one, which negatively affected [the participant],” which prompted a yes or no response. To examine intensity, a follow up question asked participants to rate the hassle unpleasantness, using a sliding scale with anchors from not at all to very much (corresponding to undisplayed values of 0 to 100). Additionally, each hassle was categorized by participants as falling into one of eight domains: argument/ conflict/ disagreement (called “conflict” throughout this manuscript), financial, home-related, work-related, health/ accident (“health”), event that happened to others (“network event”), traffic/ transportation (“traffic”), or other (“miscellaneous”).

Uplifts.

Items measuring uplifts were also derived from the phone interview format used in the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) study (Ryff et al., 2017). During each EMA assessment, participants reported whether anything uplifting had occurred since the last assessment, including “any event, even a minor one, which affected [the participant] in a positive way.” If an uplift was reported, participants were then asked to indicate how enjoyable it was using a sliding scale with anchors from not at all to very much (corresponding to undisplayed values of 0 to 100). This rating was used as a positive measure of intensity. Unlike hassles, information on uplift categories was not collected.

Covariates.

We first used simple regression models to characterize the overall association between introversion and the frequency/intensity of daily experiences (variable construction described in the next section). However, in order to tease apart the unique links with introversion beyond other factors, we also ran models controlling for theoretically relevant variables that were significantly (p < .05) or moderately correlated (r ≥ |.30|) with both introversion and at least one of the daily experience variables. Variables that were considered as covariates, but which did not meet these criteria were: age, gender, and EMA-derived variables representing the percentage of assessments where participants reported being around other people, actively socializing, and engaging in physical activity. Final control variables were trait neuroticism4 (measured using a 24-item IPIP scale [Johnson, 2014; α = .88]) and recent depression and anxiety symptoms (PROMIS-D 8a and PROMIS-A 7a short-form inventories [Pilkonis et al., 2011, 2014]; α = .93 and .92, respectively).

Statistical Plan and Analyses

Analyses were run using R version 4.0.3 (R Core Team, 2020) and R Studio version 1.2.5033, and code is provided on OSF, https://osf.io/t8pcm/ (DeMeo, 2021).

EMA-derived variables.

Because the number of reports per participant varied between participants and because that variation was related to introversion (with introverts completing more EMA reports in general, r = .17), the proportion of total hassles and uplifts across occasions was used in primary analyses to help account for individual variability in the number of reports per participant. This proportion was created by dividing the number of total hassles and uplifts by the total number of completed EMA reports (which ranged from 15 to 70 assessments). For intensity ratings, average ratings of hassle unpleasantness and uplift enjoyment were taken per person, and both within- and between-person variability measures are reported. For exploratory analyses, we constructed a frequency variable for each hassle domain. Most frequency variables of specific hassle domains were highly skewed (skew > 2) thus log10 (x+1) transformations were used to correct for skewness and the transformed variables were used in all analyses using these variables. For the exploratory analyses, we also provide adjusted p-values (‘q-values’) via the p.adjust function in the ‘stats’ package (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995; Jafari & Ansari-Pour, 2019), which controls the false discovery rate (i.e., the expected proportion of false positives among all positives). We used a false discovery rate of 5%, which can be interpreted as the percentage of significant results that are truly null.

We also conducted two sets of sensitivity analyses. First, we completed analyses using raw counts instead of the proportion variables to examine whether results were related to the frequency of reporting. Next, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine if results were changed by excluding non-beeped assessment responses, which, although excluded from our primary analyses, provided additional data, and may reflect responses to more recent experiences (and thus further reduce recall biases). Information on construction of these alternate variables is provided on the OSF site (DeMeo, 2021). Results from both sets of sensitivity analyses were similar in terms of the overall pattern of results to primary analyses (details provided in Supplemental Tables 5 through 8).

Analyses.

Regression models used grand mean-centered variables and were run using the ‘lm’ function to generate parameter estimates. Robust standard errors, confidence intervals, and significance tests were estimated using the ‘sandwich’ package with the vcov option ‘vcovHC’ and default type (i.e., HC3; Zeileis et al., 2020; Zeileis, 2004).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics and correlations between introversion and other variables are presented in Table 2. Introversion was normally distributed, although participants’ levels did not span the entire possible range (range: 1.00 [least introverted] to 4.60 [most introverted]).

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations and Other Descriptors Presented for Continuous Variables and t-values for Tests of Gender Differences

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Introversion | — | ||||||||

| 2. Hassle Frequency | .12# | — | |||||||

| 3. Unpleasantnessb | .05 | .04 | — | ||||||

| 4. Uplift Frequency | −.17 ** | .27 **** | −.11# | — | |||||

| 5. Enjoymenta | −.18 ** | −.11 | .26 **** | .11 | — | ||||

| 6. Neuroticism | .52 **** | .24 *** | .21 ** | −.11# | −.23 *** | — | |||

| 7. Depression symptoms | .39 **** | .26 **** | .21 ** | −.05 | −.11 | .54 **** | — | ||

| 8. Anxiety symptomsc | .36 **** | .37 **** | .23 *** | −.06 | −.12# | .54 **** | .72 **** | — | |

| 9. Aged | .09 | .17 ** | −.16 * | .14 * | −.04 | −.02 | −.05 | −.10 | — |

| Gender (female) | −0.22 | 0.70 | 1.85# | 0.28 | 1.25 | 1.61 | 0.38 | 1.03 | −0.19 |

| Mean | 2.49 | 16.94 | 67.69 | 26.60 | 79.22 | 2.50 | 15.68 | 17.23 | 46.31 |

| SDBP | 0.70 | 16.08 | 18.06 | 28.11 | 15.86 | 0.63 | 7.10 | 6.03 | 11.04 |

| Minimum | 1.00 | 0.00 | 7.20 | 0.00 | 8.00 | 1.13 | 8.00 | 7.00 | 25.00 |

| Maximum | 4.60 | 90.57 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 4.33 | 40.00 | 32.00 | 65.00 |

| Skew | 0.32 | 1.64 | −0.65 | 1.28 | −1.22 | 0.33 | 0.93 | 0.07 | −0.19 |

Note. N = 242 unless otherwise noted. Statistically significant associations are bolded. BP = between-person.

n = 227.

n = 224.

n = 239.

n = 241.

p < .0001,

p <.001,

p <.01,

p <.05,

p <.10

Participants reported hassles in 16.94% of assessments on average, approximately equal to 11.86 hassles over 14 days, although it should be noted that hassles may not be evenly spread across the 14-day period. For instance, participants reported hassles on only 41.02% of study days (SD=27.63) on average. Additionally, a small proportion of participants (7.44%) reported no hassles at all. The average unpleasantness rating of hassles was a 67.69 (out of 100; SDwithin =9.42, SDbetween =18.06). Participants reported uplifts in a greater proportion of assessments (M=26.60%, SD=28.11, equivalent to 18.62 uplifts over 14 days) and on more days (49.17% of study days, SD=33.10), on average, than they did hassles. A small portion of participants (6.20%) reported zero uplifts across the study period; four of these participants also reported zero hassles. Uplifts were rated at an average score of 79.22 (out of 100) on enjoyment (SDwithin =11.73, SDbetween =15.86).

Introversion and Hassles

As expected, introversion was not significantly associated with the overall frequency of hassles (simple model: β=0.12, t(240)=1.78, p=.08), but, contrary to expectations, introversion was also unassociated with average unpleasantness ratings (simple model: β=0.05, t(222)=0.67, p=.51). As both simple models (i.e., with hassle frequency and unpleasantness) returned null results, controlled analyses are not described here (but see Table 3).

Table 3.

Standardized Parameter Estimates for Predictors of Reported Hassle Frequency (%) and Average Unpleasantness Rating of the Hassles

| Frequencya | Unpleasantnessb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI |

| Simple | .12# | [−.01, .26] | .05 | [−.09, .18] |

| Controlled | ||||

| Introversion | −.03 | [−.19, .12] | −.14 * | [−.27,− .004] |

| Neuroticism | .09 | [−.08, .25] | .17 * | [.01, .34] |

| Depression Symptoms | −.04 | [−.23, .14] | .07 | [−.12, .27] |

| Anxiety Symptoms | .37 *** | [.19, .56] | .14 | [−.05, .34] |

Note. Significant parameter estimates and associated confidence intervals are bolded. CI = confidence interval.

N = 242.

n = 224.

p < .001,

p < .01,

p <.05,

p <.10

On an exploratory basis, we also examined correlations with each domain of hassles (see Table 4). There was a small correlation between introversion and the logged frequency of health hassles (r=.14, p=.03). There was also a positive association between introversion and the unpleasantness for “miscellaneous” hassles, r=.25, p=.002. Due to the exploratory nature of these analyses, effect sizes may be especially valuable for interpreting associations, and we also note that only the unpleasantness rating for “miscellaneous” hassles was significantly related to introversion once adjusting for a false discovery rate of 5%. For transparency, and consistency with other regression models, we also present regression estimates for both simple and controlled models in Supplemental Table 9.

Table 4.

Bivariate Correlations Between Introversion and the Frequency/Unpleasantness of Each Hassle Type

| Frequency (%) | Unpleasantness | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| r | r | n | |

| Conflict | .04 | .02 | 132 |

| Financial | .06 | .12 | 84 |

| Home-related | .11# | .16 | 108 |

| Work-related | −.003 | −.002 | 99 |

| Health | .14 * | .01 | 65 |

| Network Event | .06 | −.09 | 83 |

| Traffic | .04 | −.04 | 70 |

| Miscellaneous | .06 | .25 ** | 146 |

Note. N = 242 unless otherwise noted. Only miscellaneous hassle unpleasantness was significantly correlated with introversion (q = .03) following adjustment of correlation p-values for a false discovery rate of 5%.

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10

Introversion and Uplifts

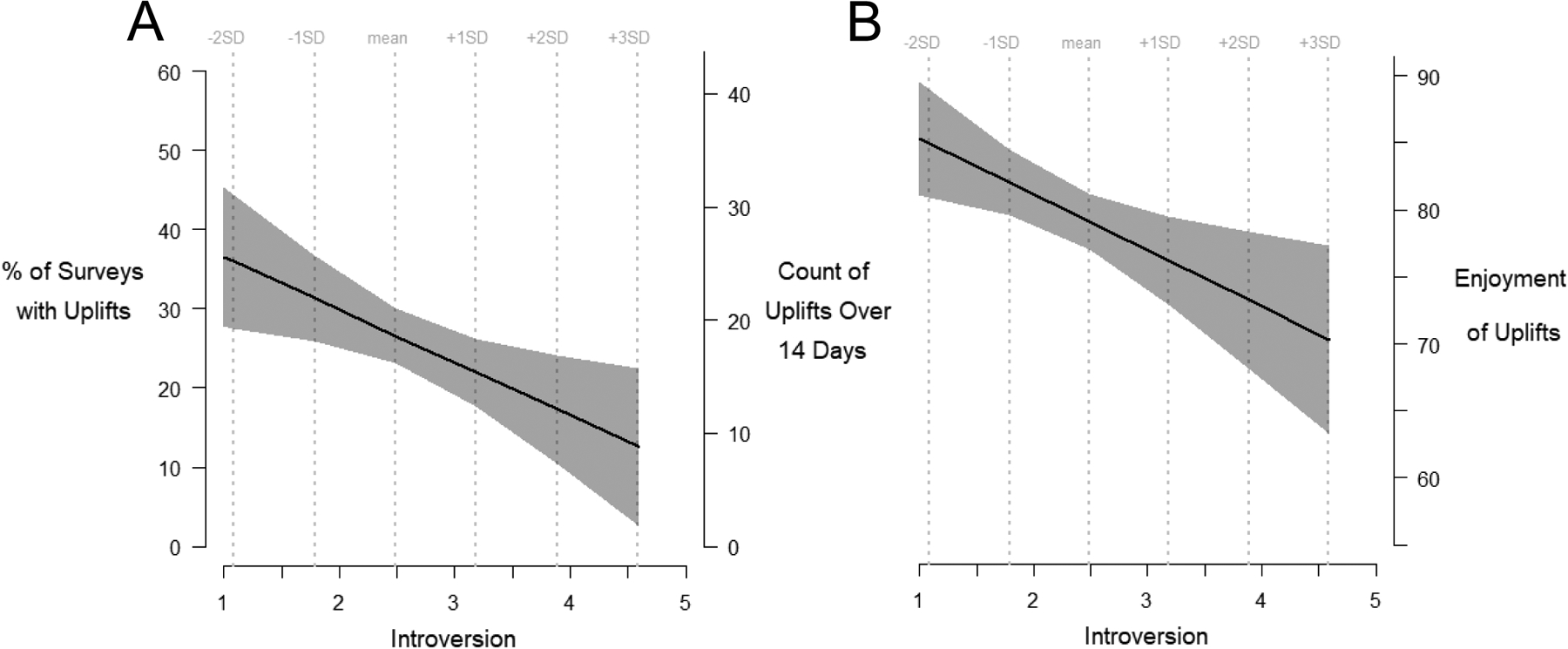

Introversion was a significant predictor of both uplift frequency and enjoyment in simple regression models, frequency: β=−0.17, t(240)=−2.71, p=.007; enjoyment β=−0.19, t(225)=−2.81, p=.005. Participants with introversion scores greater than 1 SD above the mean (scoring at least 3.19 out of 5) reported fewer uplifts during the study period compared to those participants at the mean (scoring 2.49), 21.93% of the time compared to 26.60%. This equates to approximately 15.4 uplifts over 14 days compared to 18.61 (see Figure 1A). Additionally, when uplifts were experienced, introverted participants (+1 SD) rated the uplifts as less enjoyable (76.18 out of 100) than participants with mean introversion levels (79.10, SE=1.05; see Table 5 and Figure 1B). However, only the association with frequency remained significant after controlling for neuroticism, and recent symptoms of depression and anxiety (frequency: β=−0.15, t(234)=−1.99, p=.048; enjoyment: β=−0.08, t(219)=−1.09, p=.28).

Figure 1.

The Percentage and Count of Uplifts (A) and Average Enjoyment Ratings (B) Over 14 Days Are Negatively Related to Introversion. Association Are From Simple, Uncontrolled Models.

Note. Grey bands represent the 95% confidence interval for the regression lines.

Table 5.

Standardized Parameter Estimates for Predictors of Reported Uplift Frequency (%) and Average Enjoyment Rating of the Uplifts

| Frequencya | Enjoymentb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI |

| Simple | −.17 ** | [−.29, −.05] | −.19 ** | [−.31, −.06] |

| Controlled | ||||

| Introversion | −.15 * | [−.29, −.001] | −.08 | [−.24, .07] |

| Neuroticism | −.05 | [−.20, .10] | −.18* | [−.35, −.02] |

| Depression Symptoms | .04 | [−.14, .22] | .002 | [−.20, .20] |

| Anxiety Symptoms | −.02 | [−.21, .18] | .01 | [−.17, .19] |

Note. Significant parameter estimates and associated confidence intervals are bolded. CI = confidence interval.

N = 242.

n = 227.

p < .01,

p < .05

Discussion

In the current research, we sought to examine whether introversion-extraversion was associated with two often conflated aspects of everyday uplifts and hassles: frequency and intensity. Data were collected from a socioeconomically and racially/ethnically diverse sample using EMA, which is more ecologically valid than previous approaches and which minimizes the distorting effects of recall (Stone & Shiffman, 2010). Drawing on theory and extant literature, we hypothesized that introversion would be related to fewer and less enjoyable uplifts, and with more unpleasant (but not more frequent) hassles. In line with our expectations, we found that introversion was associated with both fewer and less enjoyable uplifts. However, we did not find evidence for an association of introversion with overall hassle frequency or unpleasantness.

Introversion and Hassles

We found no association between introversion and hassles broadly, neither with their frequency nor intensity, which aligns with some, but not all, of the previous literature. Of previous studies that most clearly examined hassle frequency, all reported no significant association with introversion (Davis et al., 2006; Leger et al., 2016; Zautra et al., 1991, 2005). In contrast, one study that used a combined metric of frequency and intensity reported a positive association between introversion and hassles (Belsky et al., 1995). Null findings observed between introversion and hassles in the present study may also seem in contrast to laboratory and vignette-based studies, which have generally suggested introverts have a heightened reactivity and inability to cope with stress. However, the present research is the first to our knowledge to examine associations between introversion with both hassle frequency and intensity in everyday life, which may reveal different patterns than what is observed in artificial settings for a myriad of reasons including but not limited to the diversity of factors and settings encountered outside of the lab and that participants play an active role in choosing those environments. In terms of retrospective studies of introversion and hassles that have focused on intensity, findings have been very mixed (again, perhaps due to methodological differences).

Our finding that introversion was not associated with hassle unpleasantness may also potentially be explained by our use of a broad assessment of hassles in primary analyses, as opposed to focusing on specific types of hassles. In fact, in our exploratory analyses, we found some preliminary evidence of person-environment interactions — where the occurrence or experience of an event depends on characteristics of both the situation and the person (Buss, 1987; Funder, 2008; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, p. 55). For example, in the current research, introverts perceived their “miscellaneous” hassles, in particular, as more unpleasant than did extraverts. We are limited in our ability to interpret this finding given that we do not know what experiences were categorized by participants as “miscellaneous”; however, these analyses provide some evidence that introversion may only be related to certain types of hassles.

Similarly, while we found no overall association between introversion and hassle frequency, our exploratory analyses showed that introverts tended to report more “health and accident” related hassles in the present research, although this correlation was not significant following correction for a 5% false discovery rate. One previous study specifically separated out “health” related hassles in their analyses, but did not find an association with introversion (Zautra et al., 1991). Notably, the health hassles in that study only included certain “objective” experiences (e.g., coming down with cold or flu) and specifically minimized reporting of internal states and experiences, such as might be confounded with mental health or personality traits (discussion in Dohrenwend & Shrout, 1985; Kohn et al., 1990; Lazarus et al., 1985). A link between introversion and various negative health consequences has sometimes been reported (e.g., Goodwin & Friedman, 2006; Klein et al., 2011; Kotov et al., 2010; Robertson et al., 1989; Sutin et al., 2013); it is thus possible that introverts may report more health hassles due to health-related issues, such as symptoms, doctors’ appointments, health insurance struggles, or other experiences. Future research is needed to confirm whether an association with introversion and health-hassles truly exists and, it would be valuable for such work to examine the specific experiences that are reported as health hassles.

Introversion and Uplifts

In contrast to the lack of evidence for an association of introversion and hassles, in line with our hypotheses, introverts in this sample tended to report less frequent and less enjoyable uplifts. These findings are consistent with previous studies using retrospective reporting, as well as theories of introversion-extraversion-associated characteristics, such as tending to experience positive emotions and seeking rewarding stimuli. Broadly, our findings indicate that introversion is likely related to multiple characteristics of uplifts. Interestingly, the association between introversion and uplift frequency, but not enjoyment, held even after controlling for mood-relevant factors (depression and anxiety symptoms, neuroticism); this may suggest that mood is more related to the association between introversion and perception of uplifts, and less so with frequency. Notably, two previous studies of introversion and uplifts reported that introversion was associated with uplifts primarily in specific domains, such as with friends, co-workers, and social events (Davis et al., 2006; Mayberry et al., 2006). In the current research, both being with others and actively socializing were unrelated to introversion or uplifts, which may suggest either a role for non-social uplifts or that our EMA variables did not capture interactions in relevant domains (e.g., socializing with friends versus family).

Limitations, Future Directions

There are some limitations of the present study, but also some exciting future directions. First, any experience could be reported as an uplift or hassle in the present research; this potentially accounts for individual differences in how people perceive and appraise experiences, but also limits our ability to directly compare reactions to or perceptions of the exact same experience. For example, what is considered an uplift by an extravert (e.g., a social interaction with a stranger) may be considered a hassle by an introvert. Similarly, while we made some comparisons using self-reported domains of hassles in our exploratory analyses, there may be more variability in the characteristics of experiences within these domains than we were able to capture. For example, in the stress literature, variability in stressor experience includes who is involved, whether harm has already taken place or whether it is anticipated, and the real or perceived consequences of the experience (e.g., loss, risk to health or safety, etc.; see Almeida et al., 2002a; Lazarus, 2006, p. 70–76). In contrast to hassles, self-reported domains of uplifts were not solicited, due to balancing EMA survey length (and resultant participant burden) with the primary goals of the larger ESCAPE study. Thus, there is even more to be explored with regard to uplifts. Future research may benefit from combining our approach of allowing all experiences to be reported as either uplifts or hassles with items to gather additional details about the experiences, such as described above, which may further clarify introversion’s association with daily experiences.

In a similar vein, more research will be needed to untangle why and how introversion is associated with uplifts and some hassles. For example, introverts may be less active and busy (leading to fewer opportunities for experiences), and they may experience less enjoyment of certain uplifts, such as socializing. On the other hand, extraverts tend to be gregarious, socially warm, and excitement-seeking, suggesting that they both seek and attract social interactions and other positive experiences. Beyond leading to increased quality and/or quantity of reported uplifts, the uplifts may indirectly affect (i.e., buffer) the experience of hassles in terms of frequency and/or intensity. These examples are illustrative and far from exhaustive but serve to demonstrate the many ways introversion may manifest in daily life in transaction with the environment, ultimately leading to meaningful individual differences that can relate to health and well-being. Characterizing these daily processes further will help inform future research towards both clinical and non-clinical interventions. For example, interventions to increase experiences or perceptions of uplifts could be healthy for introverts, but more research is needed to inform whether or not this is an appropriate and feasible strategy. Simply telling introverts to act extraverted may not be enough; they may find different situations positive and uplifting as compared to more extraverted individuals, or there may be ways to harness social interactions so that they are palatable to introverts but with similar “uplifting” effects.

An additional limitation of the current research may be that the introversion scale used in the present research differs somewhat from previous studies of introversion and daily experiences. The items in our scale primarily focus on the social aspects of introversion, while other dimensions of this broad trait were not assessed, such as sensation seeking, activity, positive emotionality, and social dominance (Costa & McCrae, 1992). It is possible that future research with other measures of introversion will observe varying associations between introversion and daily experiences due to differences in assessment (Pace & Brannick, 2010).

Lastly, the present research focused on cross-sectional associations between introversion and daily experiences. We thus could not examine whether differences in these daily processes mediate an association between introversion and health -- an important direction for future research.

Conclusions

Results of the current research suggest that there is not an overall, “blanket” connection between introversion and hassles, whereas an overall association between introversion and uplifting experiences was observed. These findings are unique from past research linking introversion with positive and negative events in that the data were collected using ecologically valid methods in daily life, with minimal recall. We were able to untangle two distinct aspects of daily experiences, frequency and intensity, which may have different underlying causes and present distinct (potential) targets for intervention. Although future research will be needed to examine the underlying cause of these patterns as well as their potential to mediate associations with health, we view the current research as a necessary step towards understanding how introversion manifests in everyday experiences. Better understanding such connections may help researchers move beyond viewing introversion as an abstract trait and toward determining specific causal mechanisms by which it relates to health and integration of introversion into interventions for well-being.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Aging grants R01AG039409 (PI: Sliwinski) and R01AG042595 (MPIs: Graham-Engeland & Engeland).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/competing interests: The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Consent to participate: The institutional review board at the study institution approved the protocol, and informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Pre-registration: This research was not pre-registered.

Introversion-extraversion is a multi-dimensional trait, though it is commonly operationalized as a single continuous score with lower levels of extraversion being synonymous with higher levels of introversion. In this manuscript, we will use introversion and extraversion to relate to two poles of the same trait and “introvert”/”extravert” as shorthand to approximate where persons fall on the continuum.

We use intensity to describe an array of perceptions, including how severe and undesirable the experience was as well as how bothered participants were by it. Precise framing and response options are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

ESCAPE study information, codebooks, and a form to request data access are available from the study Open Science Framework (OSF) site, https://osf.io/4ctdv/ (Pasquini et al., 2019).

In case of interest, we also provide supplemental analyses controlling for all other domains of the Big Five because they were measured and correlated with introversion and our outcome variables (see Supplemental Table 2). All results related to introversion and daily experiences were effectively the same with the inclusion of these constructs (details are available on OSF and in Supplemental Tables 3 and 4).

Availability of data:

Data used are from the Effects of Stress on Cognitive Aging, Physiology, and Emotion (ESCAPE) study; study information, codebooks, and a form to request data access are available from the study Open Science Framework (OSF) site, https://osf.io/4ctdv/.

References

- Almeida DM, Piazza JR, Stawski RS, & Klein LC (2011). The Speedometer of Life: Stress, Health and Aging. In Handbook of the Psychology of Aging (7th Ed). Elsevier Inc. 10.1016/B978-0-12-380882-0.00012-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, & Kessler RC (2002). The Daily Inventory of Stressful Events: An interview-based approach for measuring daily stressors. Assessment, 9(1). 10.1177/1073191102091006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin Z, Constable RT, & Canli T (2004). Attentional bias for valenced stimuli as a function of personality in the dot-probe task. J Res Pers, 38(1), 15–23. 10.1016/j.jrp.2003.09.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton MC, & Lee K (2001). A theoretical basis for the major dimensions of personality. Eur J Pers, 15(5), 327–353. 10.1002/per.417 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF (1997). The relationships among momentary emotion experiences, personality descriptions, and retrospective ratings of emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(10), 1100–1110. 10.1177/01461672972310010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Crnic K, & Woodworth S (1995). Personality and Parenting: Exploring the Mediating Role of Transient Mood and Daily Hassles. J Pers, 63(4), 905–929. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00320.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, & Hochberg Y (1995). Controlling the False Discovery Rate : A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Stat Soc, 57(1), 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, & Zuckerman A (1995). A framework for studying personality in the stress process. J Pers Soc Psychol, 69(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM (1987). Selection, Evocation, and Manipulation. J Pers Soc Psychol, 53(6), 1214–1221. 10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles S, Piazza J, Mogle J, Sliwinski M, & Almeida D (2013). The Wear and Tear of Daily Stressors on Mental Health. Psychol Sci, 24. 10.1177/0956797612462222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang JJ, Turiano NA, Mroczek DK, & Miller GE (2017). Affective Reactivity to Daily Stress and 20-Year Mortality Risk in Adults With Chronic Illness: Findings From the National Study of Daily Experiences. 10.1037/hea0000567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, & McCrae RR (1992). The NEO Inventories.

- D’Angelo B, & Wiekzbicki M (2003). Relations of daily hassles with both anxious and depressed mood in students. Psychol Rep, 92. 10.2466/pr0.2003.92.2.416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MC, Affleck G, Zautra AJ, & Tennen H (2006). Daily interpersonal events in pain patients: Applying action theory to chronic illness. J Clinl Psychol, 62(9), 1097–1113. 10.1002/jclp.20297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delongis A, Coyne J Dakof G, Folkman S, & Lazarus R. (1982). Relationship of Daily Hassles, Uplifts, and Major Life Events to Health Status. In Health Psychol (Vol. 1, Iss. 2). [Google Scholar]

- DeMeo NN (2021). Introversion and Daily Experiences (Hassles & Uplifts) from ESCAPE Study. OSF. 10.17605/OSF.IO/T8PCM [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend B, & Shrout P (1985). “Hassles” in the Conceptualization and Measurement of Life Stress Variables. Am Psychol, 40(7). 10.1037/0003-066X.40.7.780 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans B, Stam J, Huizink A, Willemen A, Westenberg P, Branje S, Meeus W, Koot H, & van Lier P (2016). Neuroticism and extraversion in relation to physiological stress reactivity during adolescence. Biol Psychol, 117. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2016.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ (1963). Biological Basis of Personality. Nature. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ (1998). Dimensions of Personality [Reprint]. Transaction Publishers. 10.1136/bmj.2.4535.932 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman I, Ng R, & Bellugi U (2010). Do extraverts process social stimuli differently from introverts? 10.1080/17588928.2010.527434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flett GL, Molnar DS, Nepon T, & Hewitt PL (2012). A mediational model of perfectionistic automatic thoughts and psychosomatic symptoms: The roles of negative affect and daily hassles. Pers Individ Differ, 52(5), 565–570. 10.1016/J.PAID.2011.09.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch JU, Häusser JA, & Mojzisch A (2015). The Trier Social Stress Test as a paradigm to study how people respond to threat in social interactions. Front Psychol, 6, 14. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funder DC (2008). Persons, situations, and person-situation interactions. In John OP (Ed.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 568–580). Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher DJ (1990). Extraversion, neuroticism and appraisal of stressful academic events. Pers Individ Differ, 11. 10.1016/0191-8869(90)90133-C [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR (1990). An alternative “description of personality.” J Pers Soc Psychol, 59(6), 1216–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR (1999). A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. Pers Psychol Europe, 7(1), 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin R, & Friedman H (2006). Health status and the five-factor personality traits in a nationally representative sample. J Health Psychol, 11. 10.1177/1359105306066610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart PM, Wearing AJ, & Headey B (1994). Perceived quality of life, personality, and work experiences:: Construct validation of the police daily hassles and uplifts scales. Crim Justice Behav, 21(3), 283–311. 10.1177/0093854894021003001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hart PM, Wearing AJ, & Headey B (1995). Police stress and well‐being: Integrating personality, coping and daily work experiences. J Occup Organ Psychol, 68(2). 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1995.tb00578.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hemenover SH, & Dienstbier RA (1996). Prediction of stress appraisals from mastery, extraversion, neuroticism, and general appraisal tendencies. In Motivation and Emotion (Vol. 20, Issue 4). 10.1007/BF02856520 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerger M, Chapman B, & Duberstein P (2016). Realistic affective forecasting: The role of personality. Cogn Emot, 30(7). 10.1080/02699931.2015.1061481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson JG, & Williams PG (2007). Neuroticism, daily hassles, and depressive symptoms: An examination of moderating and mediating effects. Pers Individ Differ, 42(7), 1367–1378. 10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari M, & Ansari-Pour N (2019). Why, when and how to adjust your P values? Cell, 20(4), 604–607. 10.22074/cellj.2019.5992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong YJ, Aldwin CM, Igarashi H, & Spiro A (2016). Do hassles and uplifts trajectories predict mortality? Longitudinal findings from the VA Normative Aging Study. J Behav Med, 39(3), 408–419. 10.1007/s10865-015-9703-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JA (2014). Measuring thirty facets of the Five Factor Model with a 120-item public domain inventory: Development of the IPIP-NEO-120. J Res Pers, 51, 78–89. 10.1016/j.jrp.2014.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jylhä P, & Isometsä E (2006). The relationship of neuroticism and extraversion to symptoms of anxiety and depression in the general population. Depress Anxiety, 23(5), 281–289. 10.1002/da.20167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner AD, Coyne JC, Schaefer C, & Lazarus RS (1981). Comparison of two modes of stress measurement: Daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events. J Behav Med, 4(1), 1–39. 10.1007/BF00844845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner AD, Feldman SS, Weinberger DA, & Ford ME (1987). Uplifts, Hassles, and Adaptational Outcomes in Early Adolescents. J Early Adolesc, 7(4), 371–394. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Kim H-N, Cho J, Kwon M-J, Chang Y, Ryu S, Shin H, & Kim H-L (2016). Direct and Indirect Effects of Five Factor Personality and Gender on Depressive Symptoms Mediated by Perceived Stress. PLOS ONE, 11. 10.1371/journal.pone.0154140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaiber P, Wen JH, Ong AD, Almeida DM, & Sin NL (2021). Personality differences in the occurrence and affective correlates of daily positive events. J Pers, January, 1–16. 10.1111/jopy.12676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Kotov R, & Bufferd SJ (2011). Personality and Depression: Explanatory Models and Review of the Evidence. Annu Rev Clin Psychol, 7(1), 269–295. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp S (2018). Personality and Stress: Understanding the Roles of Extraversion and Neuroticism in Social Stress Scenarios [UNF]. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/honors/20

- Kohn PM, Lafreniere K, & Gurevich M (1990). The Inventory of College Students’ Recent Life Experiences: A decontaminated hassles scale for a special population. J Behav Med, 13(6), 619–630. 10.1007/BF00844738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komulainen E, Meskanen K, Lipsanen J, Lahti JM, Jylhä P, Melartin T, Wichers M, Isometsä E, & Ekelund J (2014). The Effect of Personality on Daily Life Emotional Processes. PloS One, 9(10), e110907. 10.1371/journal.pone.0110907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Gamez W, Schmidt F, & Watson D (2010). Linking “Big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull, 136(5), 768–821. 10.1037/a0020327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS (2006). Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. Springer publishing company. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, DeLongis A, Folkman S, & Gruen R (1985). Stress and Adaptational Outcomes. The Problem of Confounded Measures. Am Psychol, 40(7), 770–779. 10.1037/0003-066X.40.7.770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and Coping (Vol. 148). [Google Scholar]

- Leger KA, Charles ST, Turiano NA, & Almeida DM (2016). Personality and stressor-related affect. J Pers Soc Psychol, 111(6), 917–928. 10.1037/pspp0000083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longua J, DeHart T, Tennen H, & Armeli S (2009). Personality moderates the interaction between positive and negative daily events predicting negative affect and stress. J Res Pers, 43(4), 547–555. 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L (1994). University Transition: Major and Minor Life Stressors, Personality Characteristics and Mental Health. Psychol Med, 24(1). 10.1017/S0033291700026854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons A, & Chamberlain K (1994). The effects of minor events, optimism and self‐esteem on health. Br J Clin Psychol, 33(4). 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1994.tb01152.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry DJ, & Graham D (2001). Hassles and uplifts: Including interpersonal events. Stress Health, 17(2), 91–104. 10.1002/smi.891 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry DJ, Jones-Ellis J, Neale J, & Arentz A (2006). The positive event scale: Measuring uplift frequency and intensity in an adult sample. Soc Indic Res, 78(1), 61–83. 10.1007/s11205-005-4096-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe KO, Mack L, & Fleeson W (2011). A Guide for Data Cleaning in Experience Sampling Studies. In Mehl MR & Conner TS (Eds.), Handbook of Research Methods for Studying Daily Life (pp. 321–338). Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, & Costa PT (2008). The Five Factor Theory of personality. Handbook of Personality, 2008, 159–181. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0191886997810008 [Google Scholar]

- Mill A, Realo A, & Allik J (2016). Retrospective ratings of emotions: The Effects of Age, Daily Tiredness, and Personality. Front Psychol, 6. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, & Allaire JC (2005). Cardiovascular intraindividual variability in later life: The influence of social connectedness and positive emotions. Psychol Aging, 20(3), 476–485. 10.1037/0882-7974.20.3.476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Bergeman CS, & Bisconti TL (2004). The role of daily positive emotions during conjugal bereavement. J Gerontol, 59(4). 10.1093/geronb/59.4.P168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL, & Wallace KA (2006). Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. J Pers Soc Psychol, 91(4), 730–749. 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace VL, & Brannick MT (2010). How similar are personality scales of the “ same” construct? A meta-analytic investigation. Pers Individ Differ, 49(7), 669–676. 10.1016/j.paid.2010.06.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pascalis V. De, Paper C, Pascalis V. De, Knyazev GG, Medicine B, Deyoung CG, & Ciorciari J. (2016). Psychophysiological Bases of Personality Traits. In Int J Psychophysiol (Vol. 108, pp. 42–43). 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.07.140 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquini Giancarlo, Zhaoyang R, Sliwinski M, Scott S, DeMeo NN, & Van Bogart K. (2019). Effects of Stress on Cognitive Aging, Physiology and Emotion (ESCAPE). OSF. https://osf.io/4ctdv/ [Google Scholar]

- Peeters F, Nicolson NA, Berkhof J, Delespaul P, & De Vries M (2003). Effects of daily events on mood states in major depressive disorder. J Ab Psychol, 112(2), 203–211. 10.1037/0021-843X.112.2.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, & Cella D (2011). Item Banks for Measuring Emotional Distress From the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): Depression, Anxiety, and Anger. Assessment, 18(3), 263–283. 10.1177/1073191111411667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkonis PA, Yu L, Dodds NE, Johnston KL, Maihoefer CC, & Lawrence SM (2014). Validation of the depression item bank from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) in a three-month observational study. J Psychiatr Res, 56(1). 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressman SD, Matthews KA, Cohen S, Martire LM, Scheier M, Baum A, & Schulz R (2009). Association of Enjoyable Leisure Activities With Psychological and Physical Well-Being. Psychosom Med, 71(7). 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181ad7978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.

- Raffard S, Bortolon C, Stephan Y, Capdevielle D, & Van der Linden M (2017). Personality traits are associated with the valence of future imagined events in individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Res, 253. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson DAF, Ray J, Diamond I, & Edwards JG (1989). Personality profile and affective state of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut, 30(5), 623–626. 10.1136/gut.30.5.623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM, Gentes EL, Jones JD, Hallion LS, Coleman ES, & Swendsen J (2015). Rumination predicts heightened responding to stressful life events in major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. J Ab Psychol, 124(1), 17–26. 10.1037/abn0000025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C, Almeida DM, Ayanian J, Carr DS, Cleary PD, Coe C, Davidson R, Krueger RF, Lachman ME, Marks NF, Mroczek DK, Seeman T, Seltzer MM, Singer BH, Sloan RP, Tun PA, Weinstein M, & Williams D (2017). Midlife in the United States (MIDUS 2), 2004-2006. 10.3886/ICPSR04652.v7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider TR, Rench TA, Lyons JB, & Riffle RR (2011). The Influence of Neuroticism, Extraversion and Openness on Stress Responses. 10.1002/smi.1409 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Scott SB, Graham-Engeland JE, Engeland CG, Smyth JM, Almeida DM, Katz MJ, Lipton RB, Mogle JA, Munoz E, Ram N, & Sliwinski MJ (2015). The Effects of Stress on Cognitive Aging, Physiology and Emotion (ESCAPE) Project. BMC Psychiatry, 15(1), 146. 10.1186/s12888-015-0497-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin NL, & Almeida DM (2018). Daily Positive Experiences and Health: Biobehavioral Pathways and Resilience to Daily Stress. In The Oxford Handbook of Integrative Health Science. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190676384.013.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sin NL, Graham-Engeland JE, Ong AD, & Almeida DM (2015). Affective reactivity to daily stressors is associated with elevated inflammation. Health Psychol, 34(12), 1154–1165. 10.1037/hea0000240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens C, & Pugmire LA (2008). Daily Organisational Hassles and Uplifts as Determinants of Psychological and Physical Health in a Sample of New Zealand Police. Int J Police Sci & Manag, 10(2). 10.1350/ijps.2008.10.2.73 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, & Shiffman SS (2010). Ecological Validity for Patient Reported Outcomes. In Steptoe A (Ed.), Handbook of Behavioral Medicine: Methods and Applications (pp. 99–112). Springer; New York. 10.1007/978-0-387-09488-5_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Zonderman AB, Ferrucci L, & Terracciano A (2013). Personality Traits and Chronic Disease: Implications for Adult Personality Development. J Gerontol Series B, 68(6), 912–920. 10.1093/geronb/gbt036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swickert R, Rosentreter C, Hittner J, & Mushrush J (2002). Extraversion, social support processes, and stress. Pers Individ Differ, 32. 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00093-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Wier LM, Anderson GM, Wilkinson CW, Price LH, Carpenter LL, & Tyrka AR (2007). Temperament and response to the Trier Social Stress Test. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 115(5). 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00941.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollrath M (2000). Personality and hassles among university students: A three-year longitudinal study. Eur J Pers, 14(3), 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wearing AJ, & Hart PM (1996). Work and non-work coping strategies: Their relation to personality, appraisal and life domain. Stress Med, 12(2), 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M, Zilioli S, Ponzi D, Henry A, Kubicki K, Nickels N, & Maestripieri D (2015). Cortisol reactivity to psychosocial stress mediates the relationship between extraversion and unrestricted sociosexuality. Pers Individ Differ, 86. 10.1016/j.paid.2015.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilt J, & Revelle W (2008). Extraversion. In Leary MR & Hoyle RH (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 27–45). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilt J, & Revelle W (2016). Extraversion (Widiger TA). Oxford University Press. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199352487.013.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xin Y, Wu J, Yao Z, Guan Q, Aleman A, & Luo Y (2017). The relationship between personality and the response to acute psychological stress. Sci Rep, 7(1). 10.1038/s41598-017-17053-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka LK (2014). The Effects of Adherence to Asian Values and Extraversion on Cardiovascular Reactivity: A Comparison Between Asian and European Americans [Claremont Colleges; ]. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/56 [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Affleck GG, Tennen H, Reich JW, & Davis MC (2005). Dynamic approaches to emotions and stress in everyday life: Bolger and zuckerman reloaded with positive as well as negative affects. J Pers, 73(6). 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00357.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Finch JF, Reich JW, & Guamaccia CA (1991). Predicting the Everyday Life Events of Older Adults. J Pers, 59(3). 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00258.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeileis A, Köll S, & Graham N (2020). Various Versatile Variances: An Object-Oriented Implementation of Clustered Covariances in R. J Stat Softw, 95(1), 1–36. 10.18637/jss.v095.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeileis Achim. (2004). Econometric computing with HC and HAC covariance matrix estimators. J Stat Softw, 11, 1–17. 10.18637/jss.v011.i10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zelenski JM, Whelan DC, Nealis LJ, Besner CM, Santoro MS, & Wynn JE (2013). Personality and Affective Forecasting: Trait Introverts Underpredict the Hedonic Benefits of Acting Extraverted. J Pers Soc Psychol, 104. 10.1037/a0032281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data used are from the Effects of Stress on Cognitive Aging, Physiology, and Emotion (ESCAPE) study; study information, codebooks, and a form to request data access are available from the study Open Science Framework (OSF) site, https://osf.io/4ctdv/.