Abstract

Introduction

The prevalence of COVID-19 and its impact varied between countries and regions. Pregnant women are at high risk of COVID-19 complications compared with non-pregnant women. The magnitude of variations, if any, in SARS-CoV-2 infection rates and its health outcomes among pregnant women by geographical regions and country’s income level is not known.

Methods

We performed a random-effects meta-analysis as part of the ongoing PregCOV-19 living systematic review (December 2019 to April 2021). We included cohort studies on pregnant women with COVID-19 reporting maternal (mortality, intensive care admission and preterm birth) and offspring (mortality, stillbirth, neonatal intensive care admission) outcomes and grouped them by World Bank geographical region and income level. We reported results as proportions with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

We included 311 studies (2 003 724 pregnant women, 57 countries). The rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women varied significantly by region (p<0.001) and income level (p<0.001), with the highest rates observed in Latin America and the Caribbean (19%, 95% CI 12% to 27%; 13 studies, 38 748 women) and lower-middle-income countries (13%, 95% CI 6% to 23%; 25 studies, 100 080 women). We found significant differences in maternal and offspring outcomes by region and income level. Lower-middle-income countries reported significantly higher rates of maternal mortality (0.68%, 95% CI 0.24% to 1.27%; 3 studies, 31 136 women), intensive care admission (4.53%, 95% CI 2.57% to 6.91%; 54 studies, 23 420 women) and stillbirths (1.09%, 95% CI 0.48% to 1.88%; 41 studies, 4724 women) than high-income countries. COVID-19 complications disproportionately affected South Asia, which had the highest maternal mortality rate (0.88%, 95% CI 0.16% to 1.95%; 17 studies, 2023 women); Latin America and the Caribbean had the highest stillbirth rates (1.97%, 95% CI 0.9% to 3.33%; 10 studies, 1750 women).

Conclusion

The rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women vary globally, and its health outcomes mirror the COVID-19 burden and global maternal and offspring inequalities.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42020178076.

Keywords: COVID-19, Maternal health

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

To date, only one narrative systematic review reported global variations in SARS-CoV-2 outcomes in pregnant women and their offspring. The review assessed a variation of outcomes, including preterm birth, therapeutics for managing COVID-19 in pregnant women, intensive care admission and hospital length of stay. The results demonstrated varying preterm birth rates in pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection globally.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to assess the global variations in the rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women and its associated outcomes by geographical region and country income level. By including data from 57 countries involving over two million pregnant women, we identified significant global differences in SARS-CoV-2 infection and its health outcomes in mother and baby in countries by geographical regions and income levels. Through this work, we highlight the magnitude of differences in the burden of the disease across regions and countries in line with underlying disparities in overall health outcomes.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

The evidence from our research highlights the need for further research into the underlying causes of the trends in the data to provide solutions to improve healthcare outcomes for pregnant women and their babies in areas with a higher disease burden and poorer outcomes. Furthermore, necessary interventions are required to tackle healthcare inequalities in the context of COVID-19. As the pandemic evolves, future research should assess the impact of disease variants and vaccination programmes on the global variation of the rates of SARS-CoV-2 in pregnant women and its associated health outcomes.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by SARS-CoV-2, continues to affect populations globally. Pregnant women are considered to be a high-risk group as they are at increased risk of poorer outcomes than non-pregnant women of reproductive age.1 Vast inequalities exist in global maternal healthcare even before the pandemic, with disproportionately high maternal mortality and morbidity in lower-income countries compared with their high-income counterparts.2 Furthermore, geographical regions have historically seen an unequal burden of infectious diseases, with the Zika virus epidemic predominantly affecting Latin America and the Ebola outbreaks affecting Western Africa.3 4

Studies have reported geographical variations in the rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its associated health outcomes globally among the general population,5 6 attributing to population density, median age and urbanisation.7–9 But there is a lack of robust evidence on global variations and magnitude of differences, if any, in the rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women and its maternal and offspring outcomes. Existing evidence is based on small sample sizes and low-quality data, including case studies and case reports.10 11 Understanding any global variations in disease rates and associated health outcomes in pregnant women is essential for identifying opportunities to reduce maternal and offspring morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, it is essential to guide public health measures and effective preparation for future pandemics.

We conducted a meta-analysis to ascertain the magnitude of variations, if any, on the rates of SARS-CoV-2 and maternal and offspring outcomes in pregnant women by geographical region and country income level.

Methods

This meta-analysis is part of our ongoing PregCOV-19 living systematic review (LSR) based on a prospectively registered protocol (PROSPERO CRD42020178076; updated November 2021) and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (online supplemental 1).1 10

bmjgh-2022-010060supp001.pdf (178.3KB, pdf)

Literature search

We searched major electronic databases: Medline, Embase, Cochrane database, WHO COVID-19 database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang databases from 1 December 2019 to 27 April 2021 for relevant cohort studies reporting rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women and associated maternal and offspring outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19. No language restrictions were applied. We contacted organisations including the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), European CDC, Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre and other ministries of health for additional data.12–16 Full details of the search and identification of studies are provided elsewhere.10

Study selection

We included cohort studies with a minimum of 10 participants if they reported on SARS-CoV-2 infection status and/or maternal and offspring outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19. Specifically, studies were included if they reported maternal or early neonatal mortality, maternal intensive care unit (ICU) admission, preterm birth, stillbirth and admission to the neonatal ICU (NICU). These outcomes were decided prior to conducting the meta-analysis due to their clinical importance. Early neonatal mortality was defined as the death of a neonate up to 7 days. We defined pregnant women with COVID-19 as having laboratory confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection, irrespective of clinical presentation, and those with clinical and/or radiological findings. Pregnant women of any gestation and postpartum women up to 6 weeks were included. We undertook study selection using a two-stage process where studies were screened by title and abstract for eligibility, and then the full text of the selected studies were assessed in detail. The study selection was undertaken by PregCoV-19 consortium team members (HL/JS/MY/RB). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (ST/JA).

Study quality assessment and data extraction

At least two researchers independently extracted the data, and we assessed study quality using a prepiloted form. We assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the risk of bias tool for prevalence studies developed by Hoy et al, a validated tool for assessing internal and external validity.17 The tool consists of ten questions assessing bias with four domains focusing on external validity (population, sampling frame, selection and non-response) and six domains focusing on internal validity (data collection, case definition, measurement, differential verification, adequate follow-up and appropriate numerator and denominator). Each question is rated as low risk of bias if the study has considered the bias or high risk if the study may be biased, where a score of 1 is given. The overall score summarises the study as low (0–3), moderate (4–6) or high (7–10) risk of bias.

Data analysis

We carried out a random-effects meta-analysis of proportion for each binary outcome using the Dersimonian and Laird (D-L) method with the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation to obtain the estimate. We summarised the results of the D-L method using a pooled proportion with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The I2 statistic was used to assess the heterogeneity across effect sizes. All the statistical computations were carried out by STATA V.15.1.

We analysed the data by geographical regions (East Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, North America, South Asia) and country income levels (low income, lower middle income, upper middle income and high income) as classified by the World Bank in 2020.18 Studies that reported results from multiple geographical regions or countries with different income levels were analysed as a separate category.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis by restricting to registry-level and high-quality data. We defined a study as registry level if the study self-reported as a registry or a large database, or if the study was a population-based cohort study providing information on pregnant women with and without SARS-CoV-2 infection. Due to the limited variety of studies reporting rates and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection, it was not possible to conduct a sensitivity analysis by geographical variation. Therefore, the sensitivity analysis performed describes an overall global result.

Patient and public involvement

The PregCOV-19 LSR was supported by Katie’s Team, a dedicated patient and public involvement group in Women’s Health. The team was involved in the conduct and interpretation of the project and reporting of the main LSR through participation in virtual meetings.

Results

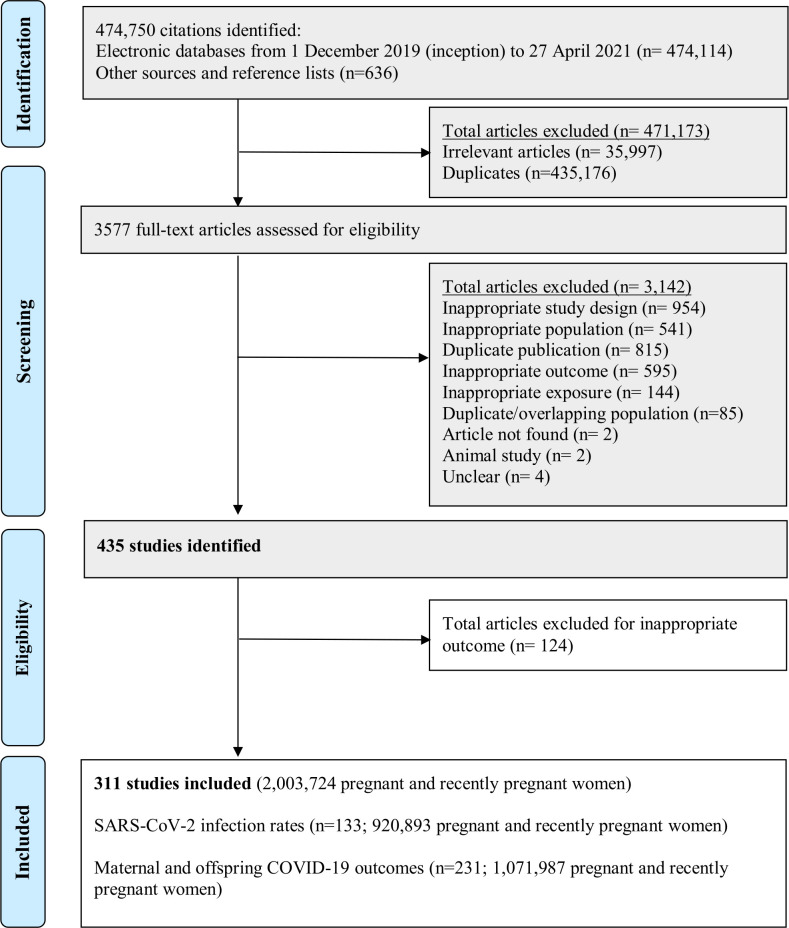

Of the 435 potentially eligible studies, we included 311 studies (133 reporting SARS-CoV-2 infection rates, 231 reporting outcomes) involving 2 003 724 pregnant women (figure 1). Fifty-three studies contained data on both the rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection and maternal and offspring outcomes.

Figure 1.

Study selection. Shaded boxes reproduced from published work: Allotey et al (In Press) Clinical Manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of COVID-19 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis.

Characteristics of included studies

One hundred thirty-three cohort studies reported rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection (920 893 pregnant women), where 37 634 women had a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Of the 133 studies reporting the rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women, 79.7% (106/133) were from high-income, 1.5% (2/133) from upper-middle-income and 18.0% (24/133) from lower-middle-income countries. There were no eligible studies from low-income countries. Of 133 studies, 79 (59.4%) were retrospective, with the remaining prospective studies (40.6%, 54/133). The majority of studies were from North America (53/133) and Europe and Central Asia (48/133). The remaining studies were from Latin America and the Caribbean (13/133), South Asia (8/133), East Asia and the Pacific (5/133), Middle East and North Africa (4/133) and sub-Saharan Africa (3/133). Overall, 38.3% (51/133) of studies were from the USA; 9.0% (12/133) from Italy; 8.3% (11/133) from Spain; 5.3% (7/133) from the UK and 4.5% (6/133) from Chile and less than 6 studies from 34 other countries (online supplemental 2).

Two hundred thirty-one studies reported on outcomes included in our review (maternal mortality, maternal admission to ICU, preterm birth, stillbirth, early neonatal mortality and admission to NICU), including data from 1 071 987 pregnant women. Of these cohort studies, 61.9% (143/231) were retrospective cohort studies, with the remaining 38.1% (88/231) having a prospective cohort design. Twenty-six studies were classified as registries reporting data for 90.7% of the total dataset, from 972 503 pregnant women. 55.8% (129/231) were from high-income, 2.6% (6/231) from upper-middle-income and 39.8% (92/231) from lower-middle-income countries. There were no eligible studies from low-income countries. The majority of studies were from North America (71/231) and Europe and Central Asia (54/231). The remaining studies were from the Middle East and North Africa (27/231), East Asia and the Pacific (26/231), South Asia (24/231), Latin America and the Caribbean (22/231) and sub-Saharan Africa (2/231). Five studies report data from multiple geographical regions and country income groups (online supplemental 3).19–23 Overall, 31.2% (72/231) of studies were from the USA, 10.0% (23/231) from China and 7.8% (18/231) from India. There were 14 studies, each from Spain and Turkey; 11 from Iran; 10 from France and Italy; 7 from Brazil; 6 from Chile, Mexico, Pakistan and Portugal; and less than 6 from 44 other countries (online supplemental 2).

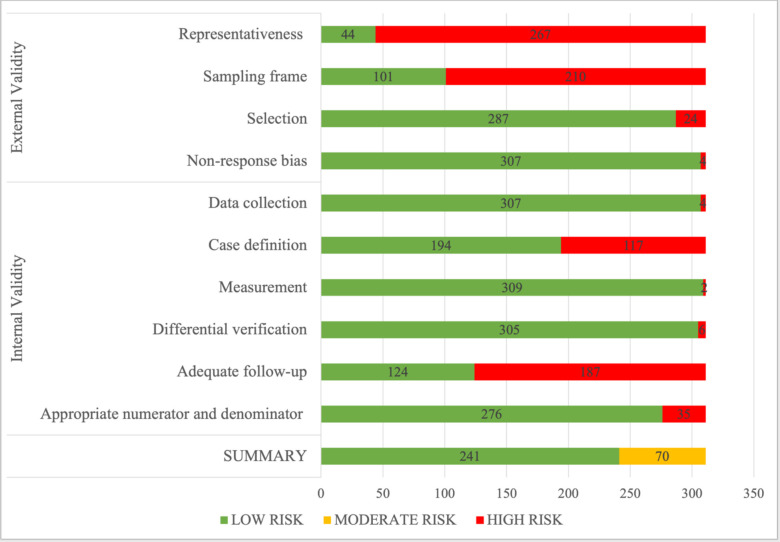

Quality of included studies

Overall, 77.5% of studies (241/311) had a low risk of bias(figure 2).17 The remaining 70 studies had a moderate risk of bias. Quality assessment for external validity showed that 14.1% (44/311) of included studies had a low risk of bias for representativeness, 32.5% (101/311) for sampling frame, 92.3% (287/311) for selection and 98.7% (307/311) for non-response bias. For internal validity, there was a low risk of bias for data collection in 98.7% (307/311) of the studies, case definition in 62.4% (194/311), measurement in 99.4% (309/311), differential verification in 98.1% (305/311), adequate follow-up in 39.9% (124/311) and appropriate numerator and denominator in 88.7% (276/311). For studies contributing to outcome data, 83.1% (192/231) had an overall low risk of bias, and 16.9% (39/231) had a moderate risk of bias. The quality assessment of prevalence studies showed 75.9% (101/133) of studies had a low risk of bias, and the remaining 24.1% (32/133) of studies had a moderate risk of bias.

Figure 2.

Quality assessment of studies included in the systematic review of global variations of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its complications in pregnant women.

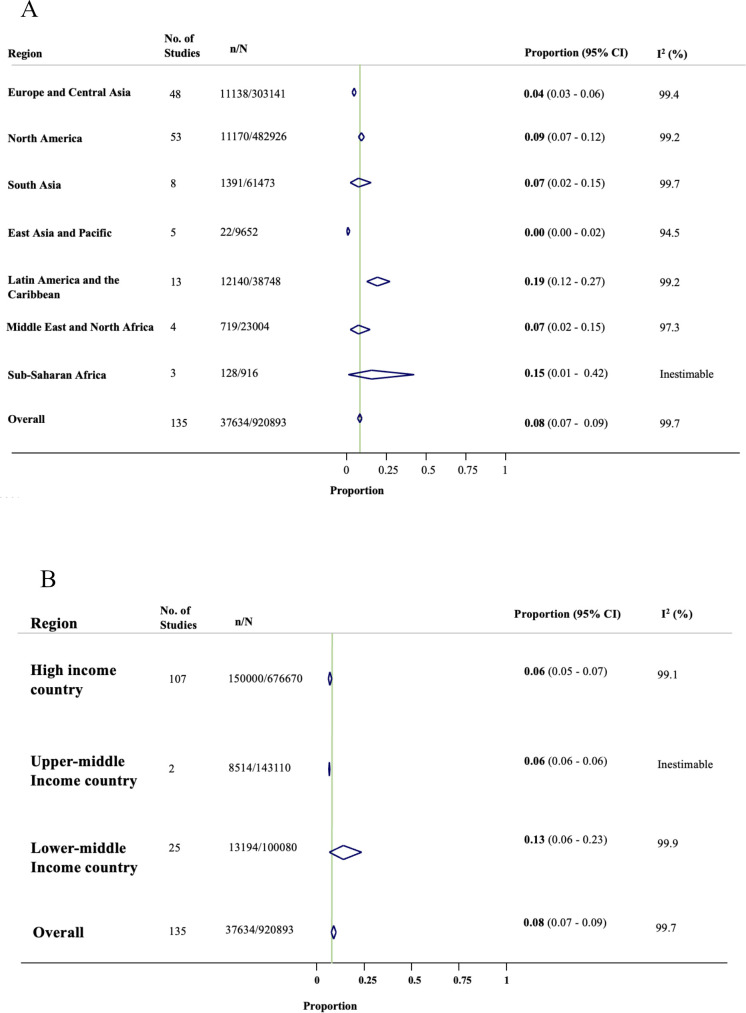

Rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women

The overall rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women admitted to or attending hospital for any reason was 8% (95% CI 7% to 9%; 135 studies, 920 893 women; figure 3). The rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women varied significantly across geographical regions (figure 3A) and country income levels (figure 3B) (p<0.001), with the highest rates reported in Latin America and the Caribbean region (19%, 95% CI 12% to 27%; 13 studies, 38 748 women) and in studies from lower-middle-income countries (13.0%, 95% CI 6% to 23.0%; 25 studies, 100 080 women). While the lowest rates were reported in East Asia and the Pacific region (0.4%, 95% CI 0% to 2%; 5 studies, 9652 women) and from upper-middle-income countries (5.7%, 95% CI 5.6% to 5.9%; 2 studies, 143 110 women). Online supplemental 4 presents SARS-CoV-2 infection rates in pregnant women limited to registry-level data and high-quality studies.

Figure 3.

Forest plots showing SARS-CoV-2 infection rates in pregnant women by (A) geographical region and (B) country income level.

There were significant differences in maternal mortality (p<0.001), admission to ICU (p<0.001), invasive ventilation (p<0.001) and preterm birth (p=0.045) by geographical region (table 1A). Studies on pregnant women with COVID-19 in South Asia reported the highest rate of maternal mortality (0.88%, 95% CI 0.16% to 1.95%; 17 studies, 2023 women). The Middle East and North Africa reported higher rates of ICU admissions (5.56%, 95% CI 3.07% to 8.62%; 19 studies, 1510 women) and preterm birth (21.9%, 95% CI 16.2% to 28.2%; 20 studies, 1514 women) than other regions (table 1A). We did not include sub-Saharan Africa in the comparisons due to the paucity of data, where of the two studies, 4/43 women died and 14/43 women were admitted to ICU.

Table 1.

Global variations of maternal outcomes among pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection by (A) geographical region and (B) country income status

| Maternal mortality | Admission to intensive care | Invasive ventilation | Preterm birth | |||||||||

| No of studies (No of women) | Proportion (95% CI) | I2 (%) | No of studies (No of women) |

Proportion (95% CI) | I2 (%) | No of studies (No of women) | Proportion (95% CI) | I2 (%) | No of studies (No of women) | Proportion (95% CI) | I2 (%) | |

| A. Geographical region | ||||||||||||

| East Asia and Pacific | 19 (797) | 0.00% (0.00 to 0.40) | 0 | 10 (403) | 2.04% (0.49 to 4.26) | 14 | 6 (286) | 0.07% (0.00 to 2.51) | 0 | 21 (761) | 11.63% (8.33 to 15.35) | 48 |

| Europe and Central Asia | 33 (24906) | 0.00% (0.00 to 0.00) | 61 | 38 (25606) | 3.26% (2.27 to 4.39) | 89 | 23 (23176) | 1.43% (0.72 to 2.30) | 90 | 37 (25870) | 10.79% (8.27 to 13.56) | 96 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 16 (27961) | 0.64% (0.04 to 1.67) | 97 | 18 (20565) | 4.92% (1.67 to 9.50) | 99 | 12 (18699) | 5.20% (2.03 to 9.49) | 98 | 16 (8258) | 13.66% (9.85 to 17.93) | 92 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 20 (1465) | 0.61% (0.04 to 1.61) | 38 | 19 (1510) | 5.56 (3.07 to 8.62) | 75 | 10 (858) | 2.52% (0.69 to 5.12) | 61 | 20 (1514) | 21.91% (16.22 to 28.15) | 86 |

| North America | 12 (119879) | 0.00% (0.00 to 0.00) | 0 | 16 (123585) | 1.76 (0.75 to 3.09) | 96 | 10 (122467) | 0.43% (0.00 to 1.33) | 96 | 57 (20381) | 12.24% (10.49 to 14.09) | 89 |

| South Asia | 17 (2023) | 0.88% (0.16 to 1.95) | 51 | 12 (2067) | 3.23% (1.41 to 5.61) | 96 | 9 (1617) | 0.53% (0.00 to 2.15) | 72 | 18 (2435) | 14.80% (10.57 to 19.56) | 86 |

| Multi-regional* | 5 (3833) | 0.72% (0.39 to 1.14) | 43 | 5 (3833) | 6.10% (4.01 to 8.59) | 89 | 2 (1275) | 4.39% (3.33 to 5.60) | NA | 5 (3833) | 14.64% (10.64 to 19.15) | 93 |

| Subgroup effect | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p=0.045 | ||||||||

| B. Country income status† | ||||||||||||

| High | 49 (137273) | 0.00% (0.00 to 0.00) | 35 | 58 (141694) | 3.20% (2.26 to 4.28) | 96 | 36 (137490) | 1.47% (0.82 to 2.25) | 95 | 103 (38958) | 12.05% (10.54 to 13.63) | 93 |

| Upper middle | 67 (8665) | 0.87% (0.00 to 5.40) | NA | 3 (8665) | 4.19% (1.42 to 8.19) | NA | 2 (8500) | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) | NA | 5 (8930) | 18.81% (6.33 to 35.77) | 98 |

| Lower middle | 3 (31136) | 0.68% (0.24 to 1.27) | 88 | 54 (23420) | 4.53% (2.57 to 6.91) | 97 | 32 (21113) | 2.20 (0.84 to 4.00) | 96 | 63 (11374) | 15.06% (12.59 to 17.70) | 88 |

| Multiple | 5 (3833) | 0.72% (0.39 to 1.14) | 43 | 5 (3833) | 6.10% (4.01 to 8.59) | 89 | 2 (1275) | 4.39 (3.33 to 5.60) | NA | 5 (3833) | 14.64% (10.64 to 19.15) | 93 |

| Subgroup effect | p<0.001 | p=0.297 | p<0.001 | p=0.176 | ||||||||

Bold text denotes p-value <0.05.

*Multiregional includes studies from all seven geographical regions. Details outlined in online supplemental 3.

†No eligible studies reported on lower-income countries.

There were significant differences in the rates of maternal mortality and invasive ventilation in pregnant women with COVID-19 according to country income level (p<0.001) (table 1B). The highest rates of maternal mortality and invasive ventilation were reported in upper-middle-income countries (0.87%, 95% CI 0.00% to 5.40%; 67 studies, 8665 women) and in lower-middle-income countries (2.20%, 95% CI 0.84% to 4.00%; 32 studies, 21 113 women), respectively. No differences between the income countries were found for preterm birth and ICU admission rates. Online supplemental 4 provides the findings limited to registry-level data for various maternal disease outcomes.

Offspring outcomes

Early neonatal mortality (p<0.001), stillbirth (p<0.001) and NICU admission (p=0.002) rates in babies born to mothers with SARS-CoV-2 infection significantly differed across geographical regions (table 2A). The rates of stillbirths were highest in Latin America and the Caribbean (1.97%, 95% CI 0.90% to 3.33%; 10 studies, 45/1750 women). Studies from South Asia reported the highest level of early neonatal mortality (1.39%, 95% CI 0.26% to 3.10%; 14 studies, 1940 women) compared with other regions (table 2A). East Asia and the Pacific reported the highest NICU admission (40.8%, 95% CI 9.86% to 76.2%; nine studies, 363 women). Results from sub-Saharan Africa were not included in the comparison due to a paucity of data for stillbirths (one study, 2/25 women)24 and early neonatal mortality (one study, 4/18 women).24 25

Table 2.

Results of systematic review of global variations of offspring outcomes born to women with SARS-CoV-2 infection by (A) geographical region and (B) country income status.

| Stillbirths | Early neonatal mortality | Admission to neonatal intensive care | |||||||

| No of studies (No of women) |

Proportion (95% CI) |

I2 (%) | No of studies (No. of women) | Proportion (95% CI) |

I2 (%) | No. of studies (No of women) |

Proportion (95% CI) |

I2 (%) | |

| A. Geographical region | |||||||||

| East Asia and the Pacific | 14 (492) | 0.00% (0.00 to 0.53) | 0 | 15 (547) | 0.00% (0.00 to 0.04) | 0 | 9 (363) | 40.78% (9.86 to 76.18) | 97.8 |

| Europe and Central Asia | 23 (23901) | 0.00% (0.00 to 0.09) | 69 | 25 (23420) | 0.00% (0.00 to 0.00) | 62 | 23 (15374) | 12.52% (7.43 to 18.57) | 98.6 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 10 (1750) | 1.97% (0.90 to 3.33) | 46 | 8 (861) | 0.53% (0.00 to 2.41) | 58 | 7 (865) | 10.69% (4.72 to 18.41) | 85.1 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 7 (719) | 0.65% (0.07 to 1.59) | 0 | 15 (1128) | 0.33% (0.00 to 1.41) | 47 | 11 (817) | 13.92% (7.72 to 21.41) | 84.1 |

| North America | 28 (17408) | 0.18% (0.04 to 0.39) | 36 | 19 (7018) | 0.00% (0.00 to 0.05) | 8 | 31 (6898) | 22.85% (16.18 to 30.25) | 97.5 |

| South Asia | 16 (2381) | 1.69% (0.61 to 3.13) | 66 | 14 (1940) | 1.39% (0.26 to 3.10) | 73 | 12 (1661) | 24.37% (7.72 to 46.17) | 98.5 |

| Multi-regional* | 3 (2201) | 1.19% (0.48 to 2.18) | NA | 4 (3127) | 0.44% (0.05 to 1.11) | 77 | 12 (9381) | 11.88% (8.81 to 15.33) | 87.4 |

| Subgroup effect | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p=0.002 | ||||||

| B. Country income status† | |||||||||

| High | 56 (33397) | 0.12% (0.02 to 0.28) | 55 | 51 (23041) | 0.00% (0.00 to 0.01) | 44 | 58 (22648) | 18.12% (14.00 to 22.61) | 98.2 |

| Upper middle | 2 (8555) | 0.11% (0.03 to 0.23) | NA | 3 (8665) | 0.88% (0.00 to 4.57) | NA | 2 (180) | 10.90% (6.66 to 15.97) | NA |

| Lower middle | 41 (4724) | 1.09% (0.48 to 1.88) | 57 | 43 (3226) | 0.62% (0.13 to 1.34) | 48 | 34 (3112) | 24.80% (14.70 to 36.41) | 97.7 |

| Multiple | 3 (2201) | 1.19% (0.48 to 2.18) | NA | 4 (3127) | 0.44% (0.05 to 1.11) | 77 | 4 (3127) | 11.88% (8.81 to 15.33) | 87.4 |

| Subgroup effect | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p=0.004 | ||||||

Bold text denotes p-value <0.05

*Multiregional includes studies from all seven geographical regions. Details outlined in online supplemental 3.

†No eligible studies reported on lower income countries.

Pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection reported significant rates of early neonatal mortality (p<0.001), stillbirth (p<0.001) and admission to NICU (p=0.004) based on country income groups (table 2B). Lower-middle-income countries reported the highest rates of stillbirth (1.09%, 95% CI 0.48% to 1.88%; 41 studies, 4724 women) and higher admission to NICU (24.8%, 95% CI 14.7% to 36.4%; 34 studies, 3112 women) (table 2B). Upper-middle-income countries reported the highest rates of early neonatal mortality (0.88%, 95% CI 0.00% to 4.57%; 3 studies, 8665 women). The rates of early neonatal mortality, stillbirths and NICU admission when restricting the analysis to registry-level data are provided in online supplemental 4.

Discussion

The burden of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women and its maternal and offspring outcomes vary significantly by geographical region and country income level. Latin America and the Caribbean saw the highest SARS-CoV-2 infection rate among pregnant women and, along with Europe and Central Asia, reported the highest rates of pregnant women requiring invasive treatment, reflecting the regions adversely affected with the highest COVID-19 burden.26 27 High-income countries have a lower overall rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women and a lower rate of complications than lower-middle-income countries.

There are possible explanations for higher infection rates in low-and-middle-income countries than in high-income countries. Due to the significant social and economic burden, infection control measures in the community, including lockdowns and social distancing, were more challenging in these settings.28 In addition, COVID-19 testing programmes in low-income and-middle-income countries were less robust than in high-income countries,29 contributing to a greater spread of disease by preventing the identification and rapid isolation of infected individuals. Similarly, the observed high mortality rates in lower-middle and upper-middle-income countries than in high-income countries may be attributed to weaker healthcare infrastructure and maternity systems,30 and high rates of SARS-CoV-2 as demonstrated by our results.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate global differences in the rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated outcomes among pregnant women and their offspring through a comparison of geographical region and country income levels. Our systematic review used published and unpublished data from an ongoing LSR, for which the literature search is updated weekly and is underpinned by robust methodology when evidence is rapidly published in varying formats. In addition, no language restrictions were applied to our search, and we included all clinically relevant maternal and offspring outcomes. As a result, this study contains data from an extensive sample, allowing for accurate estimates of disease prevalence and associated outcomes. Furthermore, we assessed the quality of all included studies using a validated tool, increasing the reliability of our results.17 To assess the robustness of our overall estimates, sensitivity analyses were conducted, restricting the analysis to include registry data and high-quality studies, which reported the consistently high rates of adverse maternal and offspring outcomes for pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Our findings were limited by the lack of studies from low-income settings and certain geographical regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa, preventing estimation of the disease effect in these areas and assessing pregnant women’s risk of requiring intensive treatment and resource allocation measures. Furthermore, the number of included studies was disproportionate between geographical regions and country income levels, with the majority of studies from high-income countries. This potentially limits the accuracy of our comparisons and highlights the continued need for more research in lower-income settings and certain regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa.31 As a result of our broad search strategy and the nature of comparing estimates between studies with differences in participant selection and sampling frameworks, there is considerable heterogeneity in the result. This was a necessary consequence of ensuring all relevant evidence is captured with no compromise on understanding the full extent of the effect of the disease on maternal and offspring outcomes, although it limits the reliability of the results.

Comparison with existing evidence

A systematic review and meta-analysis explored geographical differences in clinical care and outcomes in pregnant women; however, their limited studies (66 studies; 1239 women) prevent comprehensive evaluation.11 In addition, their inclusion of case series and case reports decreases the reliability of the results due to the risk of selection bias. The study found differences in the preterm birth rate between regions, which contrasts with our findings of no significant difference in preterm birth rates among pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection from different regions. There are emerging data on pregnancy outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection globally.32 A recent systematic review used global data to demonstrate an overall increase in adverse neonatal outcomes in babies born to women with COVID-19, including higher rates of preterm delivery and low birth weight compared with women without SARS-CoV-2 infection. These results are consistent with our findings of high rates of adverse offspring outcomes, however, does not link outcomes to country income level or geographical region. Adverse maternal and fetal outcomes had been reported during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, with the disparity between high-resource and low-resource settings supporting our findings of higher rates of maternal and early neonatal mortality in lower-middle-income countries than in other regions.33

Previous literature has been country-specific, preventing global assessment of healthcare inequalities revealed in maternal health outcomes associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.34 Similarly, literature related to the general population showcases vulnerability to adverse COVID-19 outcomes associated with socioeconomic status nationally, with most studies providing no exploration into geographical variation or variation by country income level.6 35–38 A recent study explored the variation in the COVID-19 infection-fatality ratio by a number of variables, including age, time and geography.39 The analysis results showed the highest infection-fatality ratio in North America and Europe without age standardisation, contrasting the results of maternal mortality in our review. Global differences in pregnancy and offspring COVID-19 outcomes observed in our study may support similar geographical trends observed in pregnant women, irrespective of the pandemic. For example, South Asia reported the highest maternal mortality rate, proposing a relationship between maternal mortality in pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection and global maternal mortality. Currently, South Asia contributes to the second-highest global maternal death, and sub-Saharan Africa contributes the highest global maternal mortality rate, although few studies were reported in this region, preventing any solid interpretation.40 41 This implies that global maternal health inequalities may be reflected in the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, higher mortality rates are in low-income and middle-income countries than in high-income countries, which mirrors inequalities.

Relevance for clinical practice and research

Our results showcase variation in global trends of SARS-CoV-2 infection rates and maternal and offspring outcomes. There are a number of potential explanations for the variation in SARS-CoV-2 infection rates between these regions, including the employment of different public health measures such as lockdowns and social distancing measures and different screening strategies among hospitals, leading to detection bias in some areas. Other studies have indicated that the global variation in SARS-CoV-2 infection rates among the general population may be attributed to prepandemic preparedness, which may be relevant in explaining our findings.42 In addition, meteorological and seasonal patterns have been proposed as an underlying cause of the variation of disease transmission in different regions, although further research is required to investigate this.43 44 Due to an array of hypotheses for the observed differences, there is a clear need for research into any causative differences to improve health outcomes and lower SARS-CoV-2 infection rates in regions with a higher disease burden. In addition, these results should help inform public health measures and guide effective preparedness for future pandemics.

The lack of studies from low-income countries and few studies in lower-middle-income countries reporting outcomes highlights the challenges of assessing pregnant women’s risk of COVID-19 outcomes, potentially due to weaker healthcare infrastructure and resources to conduct robust research. The trends in our results reflect well-understood healthcare inequalities between high-income countries and low-and-middle-income settings, such as quality of healthcare infrastructure, access to care and number of skilled health workers.31 45 The disproportionate burden in low-resource settings highlights an urgent need to address inequalities and continue improving high-quality healthcare access, which will reduce the adverse COVID-19 outcomes. Further studies in low-income and middle-income countries are needed for evidence syntheses to highlight disproportionate trends and develop measures to mitigate higher severe COVID-19 outcomes associated with lower income levels. Further investigation into the direct and indirect consequences of COVID-19 in global maternal health inequality is required to prioritise solutions to improve outcomes for pregnant women worldwide.46

The data in our study reflect the original SARS-CoV-2 strain, as studies included consisted of data collection periods predating the emergence of variants and vaccinations.47 Therefore, research is required to investigate the effect of new disease variants on infection rates and maternal and offspring outcomes. In addition, widescale vaccination programmes’ direct and indirect effects on SARS-CoV-2 infection rates and clinical outcomes must be assessed.

Conclusion

Geographical and country income level variations exist in SARS-CoV-2 infection rates among pregnant women and its associated health outcomes, reflecting existing global health outcome inequalities. As the pandemic develops, the importance of geographical trends increases; therefore, continued evaluation is needed to guide global maternal health strategies against COVID-19. To allow accurate comparisons and target the areas with limited resources, we need to support more research from low-income and middle-income countries. Future analyses should evaluate the effects of changing public health measures, vaccination programmes and variants on the rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its outcomes in pregnant women.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Mercedes Bonet and Vanessa Brizuela from the WHO for their support and input into the manuscript. We would like to thank other members of the PregCOV-19 Living Systematic Review Consortium: Silvia Fernández-García, Megan Littmoden, Millie Manning, Adeolu Banjoko, Dengyi Zhou, Shruti Attarde, Ankita Gupta, Kehkashan Ansari, Yasmin King, Damilola Akande, Dharshini Sambamoorthi, Anoushka Ramkumar, Helen Fraser, Meghnaa Hebbar, Sophie Maddock, Tanisha Rajah, Alya Khashaba, Kathryn Barry, Massa Mamey, Wentin Chen, Halimah Khalil, Elena Kostova, Shaunak Chatterjee, Luke Debenham, Anna Clavé Llavall, Anushka Dixit, Siang Ing Lee, Xiu Qiu, Mingyang Yuan, Madelon van Wely, Elizabeth van Leeuwen, Heinke Kunst, Asma Khalil, Simon Tiberi, Vanessa Brizuela, Nathalie Broutet, Edna Kara, Caron Rahn Kim, Anna Thorson, Ramón Escuriet, Olufemi T Oladapo, Lynne Mofenson, Van T Tong, Sascha Ellington, Gianfranco Spiteri, Julien Beaute, Uma Ram, Ajith S Nair, Pura Rayco-Solon and Hector Pardo-Hernandez. Additionally, The Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group thanks Maxime Verschuuren, Marijke Strikwerda, and Bethany Clark for help with searches and data extraction. The PregCOV-19 Living Systematic Review Group would also like to thank Katie’s Team for its contribution to James Thomas from the EPPI-Centre's work for the ongoing help with search updates. Finally, to Professor Katie Morris and Dr Victoria Hodgetts-Morton for their advice and support.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @medstudentjam, @joallotey, @javierza67, @thangaratinam

Collaborators: PregCOV-19 Living Systematic Review Consortium: Silvia Fernández-García, Megan Littmoden, Millie Manning, Adeolu Banjoko, Dengyi Zhou, Shruti Attarde, Ankita Gupta, Kehkashan Ansari, Yasmin King, Gurimaan Sandhu, Damilola Akande, Dharshini Sambamoorthi, Anoushka Ramkumar, Helen Fraser, Meghnaa Hebbar, Sophie Maddock, Tanisha Rajah, Alya Khashaba, Kathryn Barry, Massa Mamey, Wentin Chen, Halimah Khalil, Elena Kostova, Elena Stallings, Shaunak Chatterjee, Luke Debenham, Anna Clavé Llavall, Anushka Dixit, Siang Ing Lee, Xiu Qiu, Mingyang Yuan, Dyuti Coomar, Madelon van Wely, Elizabeth van Leeuwen, Heinke Kunst, Asma Khalil, Simon Tiberi, Vanessa Brizuela, Nathalie Broutet, Edna Kara, Caron Rahn Kim, Anna Thorson, Ramón Escuriet, Olufemi T Oladapo, Lynne Mofenson, Van T Tong, Sascha Ellington, Gianfranco Spiteri, Julien Beaute, Uma Ram, Ajith S Nair, Pura Rayco-Solon, and Hector Pardo-Hernandez.

Contributors: ST and JA conceptualised the study. JS, HL, RB, MY and TK selected the studies. JA, JS, HL, MY and RB extracted the data. JS, HL and JZ conducted the analyses. JS and HL are joint first authors. All coauthors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version. ST, JA and JZ are the guarantors. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: The main analysis of the PregCOV-19 Living Systematic Review Consortium was partially funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health (BMG) COVID-19 Research and Development support to the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNDP-UNFPA-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), a cosponsored programme executed by the World Health Organization, supplementing the work undertaken for this project.

Disclaimer: The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article, and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Map disclaimer: The inclusion of any map (including the depiction of any boundaries therein), or of any geographic or locational reference, does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. Any such expression remains solely that of the relevant source and is not endorsed by BMJ. Maps are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

the PregCOV-19 Living Systematic Review Consortium:

Silvia Fernández-García, Megan Littmoden, Millie Manning, Adeolu Banjoko, Dengyi Zhou, Shruti Attarde, Ankita Gupta, Kehkashan Ansari, Yasmin King, Gurimaan Sandhu, Damilola Akande, Dharshini Sambamoorthi, Anoushka Ramkumar, Helen Fraser, Meghnaa Hebbar, Sophie Maddock, Tanisha Rajah, Alya Khashaba, Kathryn Barry, Massa Mamey, Wentin Chen, Halimah Khalil, Elena Kostova, Shaunak Chatterjee, Luke Debenham, Anna Clavé Llavall, Anushka Dixit, Siang Ing Lee, Xiu Qiu, Mingyang Yuan, Madelon van Wely, Elizabeth van Leeuwen, Heinke Kunst, Asma Khalil, Simon Tiberi, Vanessa Brizuela, Nathalie Broutet, Edna Kara, Caron Rahn Kim, Anna Thorson, Ramón Escuriet, Olufemi T Oladapo, Lynne Mofenson, Van T Tong, Sascha Ellington, Gianfranco Spiteri, Julien Beaute, Uma Ram, Ajith S Nair, Pura Rayco-Solon, and Hector Pardo-Hernandez

Data availability statement

No data are available. No additional data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ [Internet] 2021:m3320 https://www.bmj.com/lookup/doi/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Graaf JP, Steegers EAP, Bonsel GJ. Inequalities in perinatal and maternal health. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2013;25:98–108. 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32835ec9b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sakkas H, Economou V, Papadopoulou C. Zika virus infection: past and present of another emerging vector-borne disease. J Vector Borne Dis 2016;53:305–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, Viral Special Pathogens Branch . 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak distribution in West Africa 2021.

- 5. Rostami A, Sepidarkish M, Fazlzadeh A, et al. Update on SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence: regional and worldwide. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021;27:1762–71. 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zohner YE, Morris JS. COVID-TRACK: world and USA SARS-COV-2 testing and COVID-19 tracking. BioData Min 2021;14:4. 10.1186/s13040-021-00233-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miller LE, Bhattacharyya R, Miller AL. Data regarding country-specific variability in Covid-19 prevalence, incidence, and case fatality rate. Data Brief 2020;32:106276. 10.1016/j.dib.2020.106276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khafaie MA, Rahim F. Cross-Country comparison of case fatality rates of COVID-19/SARS-COV-2. Osong Public Health Res Perspect 2020;11:74–80. 10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.2.03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karadag E. Increase in COVID-19 cases and case-fatality and case-recovery rates in Europe: a cross-temporal meta-analysis. J Med Virol 2020;92:1511-1517–7. 10.1002/jmv.26035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020;370:m3320. 10.1136/bmj.m3320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dubey P, Thakur B, Reddy S, et al. Current trends and geographical differences in therapeutic profile and outcomes of COVID-19 among pregnant women - a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21:247. 10.1186/s12884-021-03685-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. EPPI-Centre . COVID-19: a living systematic map of the evidence. Evid Policy Pract Inf Co-ord Cent [Internet] 2020. http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Projects/DepartmentofHealthandSocialCare/Publishedreviews/COVID-19Livingsystematicmapoftheevidence/tabid/3765/Default.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . US COVID-19 Cases Caused by Variants | CDC [Internet], 2021. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/transmission/variant-cases.html [Accessed 14 Apr 2021].

- 14. Health Surveillance Secretariat . Brazilian Ministry of health Covid-19 Bulletin 2020;17. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xia J, Wright J, Adams CE. Five large Chinese biomedical bibliographic databases: accessibility and coverage. Health Info Libr J 2008;25:55–61. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2007.00734.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. 여민경 이영섭. 미병 량 지표에 관한 중국의 임상연구 동향 분석 - China National Knowledge Infrastructure를 중심으로 - [Internet]. Vol. 22, Society of Preventive Korean Medicine, 2018. Available: https://oversea.cnki.net/index/

- 17. Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:934–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. The World Bank Group . Data: World Bank Country and Lending Groups [Internet]. World Bank Country and Lending Groups, 2020: 1–8. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups%0Ahttps://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups%0Ahttps://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgeb [Google Scholar]

- 19. D'Antonio F, Sen C, Mascio DD, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes in high compared to low risk pregnancies complicated by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection (phase 2): the world association of perinatal medicine Working group on coronavirus disease 2019. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;3:100329. 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Saccone G, Sen C, Di Mascio D. Maternal and perinatal outcomes of pregnant women with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol [Internet] 2021;57:41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Villar J, Ariff S, Gunier RB, et al. Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality among pregnant women with and without COVID-19 infection. JAMA Pediatr 2021;175:817. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vouga M, Favre G, Martinez Perez O, et al. Maternal and obstetrical outcomes in a cohort of pregnant women tested for SARS-CoV-2: interim results of the COVI-Preg international registry. SSRN Electronic Journal 2020. 10.2139/ssrn.3684424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vouga M, Favre G, Martinez-Perez O, et al. Maternal outcomes and risk factors for COVID-19 severity among pregnant women. Sci Rep 2021;11:13898. 10.1038/s41598-021-92357-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dingom MAN, Sobngwi E, Essiben F, et al. Maternal and fetal outcomes of COVID-19 pregnant women followed up at a tertiary care unit: a descriptive study. Open J Obstet Gynecol 2020;10:1482–91. 10.4236/ojog.2020.10100135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ngalame AN, Neng HT, Inna R, et al. Materno-Fetal outcomes of COVID-19 infected pregnant women managed at the Douala Gyneco-Obstetric and pediatric Hospital—Cameroon. Open J Obstet Gynecol 2020;10:1279–94. 10.4236/ojog.2020.1090118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Coxon K, Turienzo CF, Kweekel L, et al. The impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on maternity care in Europe. Midwifery 2020;88:102779. 10.1016/j.midw.2020.102779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development . COVID-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean: An overview of government responses to the crisis [Internet], 2020. Available: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=129_129907-eae84sciov&title=COVID-19-in-Latin-Amercia-and-the-Caribbean_An-overview-of-government-responses-to-the-crisis

- 28. Eyawo O, Viens AM, Ugoji UC. Lockdowns and low- and middle-income countries: building a feasible, effective, and ethical COVID-19 response strategy. Global Health 2021;17:13. 10.1186/s12992-021-00662-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pasquale S, Gregorio GL, Caterina A, et al. COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs): a narrative review from prevention to vaccination strategy. Vaccines 2021;9. 10.3390/vaccines9121477. [Epub ahead of print: 14 12 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bong C-L, Brasher C, Chikumba E, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic: effects on low- and middle-income countries. Anesth Analg [Internet] 2020;131:86–92. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Olufadewa I, Adesina M, Ayorinde T. Global health in low-income and middle-income countries: a framework for action. Lancet Glob Health 2021;9:e899–900. 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00143-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marchand G, Patil AS, Masoud AT, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of COVID-19 maternal and neonatal clinical features and pregnancy outcomes up to June 3, 2021. AJOG Glob Rep 2022;2:100049. 10.1016/j.xagr.2021.100049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Townsend R. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Heal [Internet] 2021. 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00079-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Siqueira TS, Silva JRS, Souza MdoR, et al. Spatial clusters, social determinants of health and risk of maternal mortality by COVID-19 in Brazil: a national population-based ecological study. Lancet Reg Health Am 2021;3:100076. 10.1016/j.lana.2021.100076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Neelon B, Mutiso F, Mueller NT, et al. Spatial and temporal trends in social vulnerability and COVID-19 incidence and death rates in the United States. PLoS One 2021;16:e0248702. 10.1371/journal.pone.0248702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jackson SL, Derakhshan S, Blackwood L, et al. Spatial disparities of COVID-19 cases and fatalities in United States counties. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18. 10.3390/ijerph18168259. [Epub ahead of print: 04 08 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Deguen S, Kihal-Talantikite W. Geographical pattern of COVID-19-Related outcomes over the pandemic period in France: a nationwide Socio-Environmental study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18. 10.3390/ijerph18041824. [Epub ahead of print: 13 02 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hauser A, Counotte MJ, Margossian CC, et al. Estimation of SARS-CoV-2 mortality during the early stages of an epidemic: a modeling study in Hubei, China, and six regions in Europe. PLoS Med 2020;17. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003189. [Epub ahead of print: Available from] https://dx.plos.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. COVID-19 Forecasting Team . Variation in the COVID-19 infection–fatality ratio by age, time, and geography during the pre-vaccine era: a systematic analysis. The Lancet 2022;399:1488. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02867-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Geller SE, Koch AR, Garland CE, et al. A global view of severe maternal morbidity: moving beyond maternal mortality. Reprod Health 2018;15:98. 10.1186/s12978-018-0527-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. World Health Organization, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank Group, United Nations Population Division . Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bollyky TJ, Hulland EN, Barber RM, et al. Pandemic preparedness and COVID-19: an exploratory analysis of infection and fatality rates, and contextual factors associated with preparedness in 177 countries, from Jan 1, 2020, to Sept 30, 2021. Lancet 2022;399:1489–512. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00172-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pan J, Yao Y, Liu Z, et al. Warmer weather unlikely to reduce the COVID-19 transmission: an ecological study in 202 locations in 8 countries. Sci Total Environ 2021;753:142272. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McClymont H, Hu W. Weather variability and COVID-19 transmission: a review of recent research. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18. 10.3390/ijerph18020396. [Epub ahead of print: 06 01 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mills A. Health care systems in low- and middle-income countries. N Engl J Med 2014;370:552–7. 10.1056/NEJMra1110897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kotlar B, Gerson E, Petrillo S, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal health: a scoping review. Reprod Health 2021;18:10. 10.1186/s12978-021-01070-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. World Health Organization . Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants [Internet], 2022. World Health Organization. Available: https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2022-010060supp001.pdf (178.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. No additional data are available.