Abstract

Reciprocal parent–child interactions are theorized to play a crucial role in child anxiety development and maintenance. The current study tested whether toddler-solicited maternal comforting behavior in low-threat (mildly challenging and novel) situations may be a unique, early indicator of anxiety-relevant interactions. Controlling for other types of maternal comforting behavior, a path model tested solicited comforting behavior in a low-threat context in relation to both family accommodation (FA) and child anxiety symptoms, which may subsequently continue to predict each other over time. Identifying the emergence of this cycle in early childhood could bolster anxiety development theory and preventative interventions. Mother–child dyads (n = 166) of predominantly non-Hispanic/Latinx European American and socioeconomically diverse backgrounds were assessed at child ages 2, 4, and school-age via laboratory observation and maternal report. A longitudinal path model showed that solicited comforting observed in a low-threat situation at age 2 predicted mother-reported FA and child anxiety symptoms at age 4, above and beyond unsolicited comforting behavior and comforting behavior in a high-threat context. Furthermore, FA and child anxiety were bidirectionally related between age 4 and school-age assessments. Results suggest that toddler-solicited comforting in low-threat situations may be a unique indicator of child-directed anxiogenic family processes. The current study also expands the FA literature by providing empirical evidence for a bi-directional relation between anxiety and accommodation in young children.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10802-022-00990-6.

Keywords: Toddlers, Parenting, Anxiety, Temperament

Introduction

Child anxiety development occurs in a dynamic system in which children and their environments reciprocally influence each other over time (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2021a). The parenting environment, in particular, provides a crucial regulatory context that fosters developmental continuity (Sameroff, 2014). For example, in the anxious-coercive cycle outlined by Dadds and Roth (2001), parents’ reinforcement of their anxious children’s avoidance is theorized to result primarily from their children’s increasing demands for reassurance and avoidance. In this way, even when parents initially intend to encourage their children to engage with a situation about which children are anxious, their children’s distress and anxiety results in parents’ allowance of avoidance. Both parents and children are negatively reinforced for their behavior: parents experience the immediate alleviation of their children’s distress, and children experience the removal of parental demands. Identifying interaction patterns early in childhood that reflect the emergence of an anxious-coercive cycle could augment theory related to the developmental psychopathology of anxiety and inform anxiety prevention programs that target early developmental periods (e.g., Rapee et al., 2010). The focus of the current study is toddler-solicited maternal comforting behavior in low-threat situations as one such interaction.

Toddler-Solicited Comforting Behavior

Solicited comforting behavior is defined as parents’ engagement in physical affection in direct response to their children’s bids for comfort and reassurance (Kiel et al., 2021). By nature, therefore, it is a child-elicited parenting behavior. Solicited comforting relates to children’s predisposition to anxiety in the form of inhibited temperament (Kiel et al., 2021), which characterizes the biologically-based tendency to respond to novelty and uncertainty with hesitance, avoidance, and withdrawal (Fox et al., 2001; Kagan et al., 1984). Solicited comforting predicts social withdrawal and anxious behavior above and beyond inhibited temperament, both independently and in composites of overprotection (Kiel & Buss, 2012; Kiel et al., 2021).

The context of toddler-solicited comforting likely determines its relevance to child anxiety development. The responsive and warm nature of maternal comforting behavior is not, in general, considered problematic; responsiveness and warmth typically relate to positive parent–child relationships and children’s development of adaptive emotion regulation skills (Cassidy, 1994; Morris et al., 2017). Rather, the context of the interaction in which toddlers bid for and receive comforting determines its relation to anxiety-relevant processes. Mildly challenging (“low-threat”) novel and uncertain contexts allow toddlers to practice independent coping (Buss, 2011). If toddlers avoid independent coping and instead learn to rely on their parents for external regulation of their emotional responses to uncertainty, they may not get the experience necessary to gain a sense of mastery over these situations (Kopp, 1989). Further, external reassurance may reinforce toddlers’ reliance on their caregivers for coping in future situations involving mild challenge (Dadds & Roth, 2001). Toddler-solicited comforting behavior may also reinforce mothers’ own avoidance of their toddlers’ emotional distress, evidenced by its relation to increased maternal anxiety across the toddler years (Kiel et al., 2021). Thus, solicited comforting responses in low-threat situations are expected to relate to anxiety risk in a manner theoretically similar to the anxious-coercive cycle (Dadds & Roth, 2001).

Alternatively, “high-threat” situations that are so challenging that they exceed toddlers’ abilities to engage in independent regulation may not offer opportunities to practice new skills (Kopp, 1989). Parents’ affectionate responses to toddlers’ bids for support in high-threat situations may be not only unrelated to anxiety processes, but also necessary for toddlers’ adaptive regulation. Existing work on solicited comforting (e.g., Kiel & Buss, 2012; Kiel et al., 2021) has focused on low-threat situations according to this logic. However, construct validity for toddler-solicited comforting behavior in low-threat situations as an anxiety-relevant parenting behavior would be augmented by testing it against both unsolicited (i.e., spontaneous) comforting behavior and comforting behavior in a high-threat context, in relation to outcomes relevant to the anxious-coercive cycle.

Family Accommodation

One indicator of the anxious-coercive cycle is family accommodation (FA), which characterizes parents’ patterns of changing their behavior and plans in order to alleviate child anxiety. These behaviors include changing of family routines, facilitating child avoidance, frequent attempts at soothing the child, and performing the child’s responsibilities on their behalf (Johnco et al., 2022; Lebowitz et al., 2014). Parental engagement in FA is multiply determined, and can be predicted by both child and parental factors across biological and environmental domains (Feinberg et al., 2018; Lebowitz et al., 2015; Norman et al., 2015). As would be predicted by the anxious-coercive cycle, FA has been found to relate to and predict child anxiety. Although FA was originally a focus for families of children with obsessive–compulsive disorder (Calvocoressi et al., 1995), it has been found to relate to various forms of child anxiety (Lebowitz et al., 2013; Thompson-Hollands et al., 2014). Over 95% of families of anxious children engage in some form of accommodation behavior (Johnco et al., 2022; Jones et al., 2015), which tends to be tailored to the child’s individual triggers (Lebowitz et al., 2016). Also relevant to the anxious-coercive cycle, this behavior is theorized to be a method by which family dysfunction and stress decreases in the short-term (Calvocoressi et al., 1995).

Broadly, there is a positive association between FA and child anxiety severity. In clinical samples of children in early childhood through adolescence, mothers of highly anxious children were more likely to display intrusive helping behavior in stressful (i.e. high-threat) situations than mothers of non-anxious children (Hudson & Rapee, 2001). Although this association between FA and child anxiety has also been studied in community samples, the evidence is not yet conclusive. Families of anxious children in the community are more likely to engage in FA than families of non-anxious children, and there is some evidence that parents in community and clinical samples engage in the same amount of FA (Jones et al., 2015; Kerns et al., 2017). However, in a study of children aged 7 through 17, the positive association between anxiety severity and FA frequency was only present in a clinical sample (Lebowitz et al., 2014). More community-based research is needed to better understand the link between FA and child anxiety.

The cyclical relation between FA and child anxiety may be explained by the soothing effects of accommodation on both parents and children. Mothers who are highly anxious are likely to be distressed by their child’s anxiety, and, thus, likely to engage in accommodation (Settpani & Kendall, 2017). FA may reduce parental distress not only by decreasing the child’s current anxiety, but also by preventing further outbursts, as children often become angry or more distressed when they are not accommodated (Lebowitz et al., 2014). FA soothes children’s anxiety (Bögels & Brechman-Toussaint, 2006), and it also has comforting effects for the parents, creating a cycle that is ultimately reinforcing for both parents and children.

With few exceptions (e.g. Feinberg et al., 2018; Thompson-Hollands et al., 2014), most research in this area focuses on middle childhood and adolescence, when anxiety disorders are most likely to be diagnosed. However, there is value in identifying indicators of the anxious-coercive cycle in early childhood, when risk for anxiety and anxiety-relevant parenting behavior are identifiable but more malleable (Rapee et al., 2010). Furthermore, the positive association between parental accommodation and child anxiety severity is stronger in childhood, with rates of accommodation being higher at earlier child ages (Johnco et al., 2022). As such, it is important determine whether the relation between FA and anxiety appears in early childhood.

The Current Study

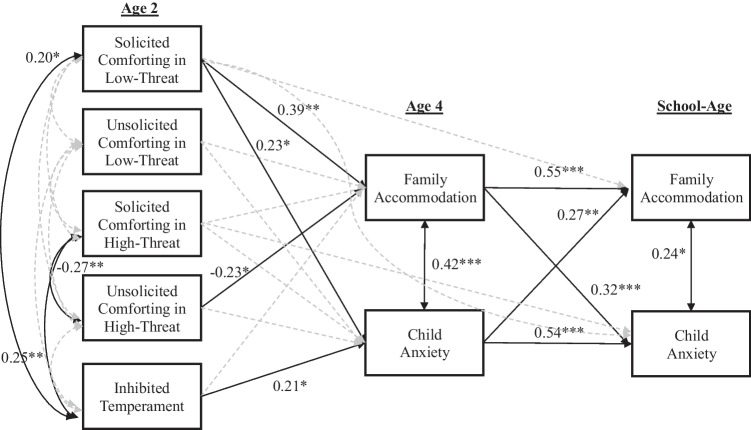

Rooted in theory surrounding the anxious-coercive cycle that occurs in families of anxious children (Dadds & Roth, 2001), toddler-solicited comforting behavior may be conceptualized as an entry into later reciprocal relations between child anxiety and FA (Fig. 1). Toddler-solicited comforting behavior in a low-threat context should therefore uniquely (independently of comforting behavior displayed spontaneously and in high-threat situations) predict FA (hypothesis 1) and child anxiety symptoms (hypothesis 2). To acknowledge that the relation between toddler-solicited comforting and these outcomes may occur directly or indirectly through each other (i.e., solicited comforting to FA to child anxiety, or solicited comforting to child anxiety to FA), the model included two time points of outcome data, child age 4 and at school-age (roughly, kindergarten entry), which allowed for more robust testing of longitudinal indirect effects. Because it relates to both solicited comforting and predicts anxiety outcomes (Kiel et al., 2021), toddler inhibited temperament acted as a covariate to further isolate effects unique to low-threat solicited comforting. The model included an assessment of inhibited temperament unique from data previously published from this sample (Kiel et al., 2021). With these considerations, the current study contributes to the developmental psychopathology literature by establishing new evidence for the construct validity of toddler-solicited comforting in low-threat contexts as relevant to the etiology of child anxiety. A second contribution arises from the test of the relevance of FA to child anxiety in a community sample that, unlike clinical samples, was not selected for particular characteristics and is therefore generalizable to a wider population of children. According to the developmental psychopathology framework, representation of a broad range of anxiety symptomatology, including absence of anxiety, is necessary to understand continuity in both adaptation and risk, as well as the emergence of risk from more typical developmental processes (Sameroff, 2014). A third contribution comes from tests of the bidirectional associations between FA and child anxiety symptoms. Transactional theories suggest that bidirectional effects should exist above and beyond stability in FA and child anxiety symptoms from age 4 to the school-age assessment (hypothesis 3).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual Model of the Role of Toddler-Solicited Comforting Behavior in Anxiogenic Family Processes. Note: This theoretical model acknowledges that toddler-solicited maternal comforting behavior is likely influenced by children’s inhibited temperament. Toddler-solicited comforting is by nature dyadic and so, above and beyond what would be predicted from inhibited temperament, should predict transactional family processes in later childhood. Indicators of these processes include family accommodation and child anxiety symptoms

Method

Participants

The sample included 166 families with young children (44% female) participating in a larger longitudinal study. Families were recruited through mailings to parents who posted birth announcements in local newspapers, flyers at childcare centers and pediatricians’ offices, and in-person sign-ups at local events and a Women, Infants, and Children’s office. Inclusion criteria included children being in the correct age range for the wave at which they joined and mothers being able to complete study procedures in English. Exclusion criteria included diagnosis of a developmental or neurological disorder, or the child being the sibling of another participant. The study used a rolling recruitment design, with families able to join the study at multiple entry points in order to offset attrition. Families joined the study for the age 2 assessment (n = 143), or the age 4 assessment (n = 23). Cohort differences are discussed in the Missing Values section.

Children were, on average, 26.85 (SD = 2.02, range = 22.70 to 33.05) months at the age 2 assessment, 51.85 (SD = 3.48, range = 38.64 to 58.97) months at the age 4 assessment, and 66.59 (SD = 6.79, range = 54.11 to 90.02) months at the school-age assessment. At the time of the target child’s birth, mothers (all > 18 years during study participation) ranged in age from 17.27 to 43.91 years (mean = 30.28, SD = 5.48). Mothers described their own/their children’s race, respectively, as Asian/Asian American or Pacific Islander (3.0%/1.2%), Black/African American (1.8%, 1.2%), White/European American (92.2%/82.5%), or multiracial/category not listed on the form (2.4%/22.4%). Mothers described their own/their children’s ethnicity, respectively, as Hispanic/Latinx (3.0%/4.2%) or non-Hispanic/Latinx (96.4%/95.2%). One mother (0.6%) declined providing race/ethnicity information. Mothers ranged in education from 9th grade to a doctoral degree (mean = 15.69, SD = 2.61 years of education). On average, families reported gross annual income in the range of $51-60K, with 29% of the sample reporting < $40K/year.

Procedure

All procedures were approved by Miami University’s Institutional Review Board (protocols 00248r, 01026r, and 01245r). The study was not preregistered. Data and code are available at https://osf.io/7rf4t/?view_only=2e79b56782214850a11394284760f252.

Children came to the laboratory with their mothers at age 2, age 4, and around their kindergarten year as part of a larger longitudinal study. Laboratory procedures were used only for age 2 variables; the latter assessments only utilized questionnaires. Prior to each visit, mothers were sent a packet including consent forms and questionnaires to complete. At the age 2 laboratory assessment, the primary experimenter (“E1”) explained Risk Room, Clown, and Spider episodes, as well as other episodes not included in the current study, to the mother prior to their enactment. Episodes occurred in the same order across participants, with Risk Room at the beginning, Clown in the middle, and Spider towards the end, with other tasks in between.

The Risk Room episode (Buss & Goldsmith, 2000) provided the assessment of children’s inhibited temperament. E1 led the child and the mother to a large room full of stimuli that were novel and required some level of risk for engagement (i.e. an inflatable tunnel, a balance beam, a trampoline, a black box with a scary face on it, and an animal mask on a pedestal). E1 told the child to play with the toys however they liked, as well as instructed their mother that the child needed to play by themselves (although mothers were instructed that they could respond to children’s questions or bids for attention). Children played freely for 3 min. Then, E1 re-entered the room and gave the child a series of prompts. E1 prompted the child to crawl through the tunnel, walk across the balance beam, jump on the trampoline, put their hand inside the scary box, and touch the animal mask, in that order. If the child hesitated to comply, E1 prompted the child up to two more times for each stimulus. If the child failed to comply after three prompts, E1 moved on to the next stimulus or, in the case of the animal mask, ended the episode.

The Clown episode (Nachmias et al., 1996) provided observation of maternal comforting behavior in a “low-threat” context (as validated in Buss, 2011). E1 brought the mother and child into a large empty room, instructed the mother to behave “however seems natural or what you would typically do,” and then left the room. After 15 s, a secondary experimenter (“E2”), dressed in a clown costume, rainbow wig, and red nose (no makeup) and carrying a large cloth bag, came into the room and greeted the child in a friendly tone. She then invited the child to play three games with her, each lasting 1 min: blowing bubbles, catch with beach balls, and musical instruments. The clown played with the child (if they approached) or provided friendly prompts and encouragement while playing with the toys by herself if they did not. After the games, the clown put the toys back in her bag (inviting the child to help during clean-up), said goodbye, and left the room. E1 then returned and ended the episode.

The Spider episode (Buss & Goldsmith, 2000) provided observation of maternal comforting in a “high-threat” context (as validated in Buss, 2011). E1 brought the mother and child to the large room and asked the mother to sit in a chair with her child on her lap. On the other side of the room sat a large plush spider affixed to a remote-controlled toy truck. E1 instructed the mother to keep her child on her lap until the spider began moving, after which the child could freely explore. E1 also instructed the mother that she could behave “naturally and as she typically would” in this task. Once E1 left the room, E2 controlled the spider (from a location blocked from the child’s view) to approach half-way towards the mother’s chair, pause for 10 s, retreat to its starting place, pause for another 10 s, approach the entire way to the chair (or the child’s location), pause for 10 s, and retreat to its starting place. After it had paused for another 10 s, E1 entered the room and asked the child to approach and touch the spider with up to three prompts. Whether or not the child touched the spider, the primary experimenter touched the spider and told the child it was a pretend/toy spider for debriefing purposes.

Separate teams coded the Risk Room for inhibited temperament and Clown and Spider for maternal comforting behaviors. Within each team, coders received training from a master coder. Training (typically 10–20 h) involved learning behavior definitions, watching examples, and practicing independent coding. Coders were required to achieve a minimum standard of inter-rater reliability (% agreement of 0.90, or kappa or intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] of 0.80, depending on code) prior to coding independently. Master coders double-scored 15–20% of cases throughout coding to prevent coder drift. Final average reliabilities are indicated in the description of each measure.

Families received an invitation to participate in a follow-up at both child age 4 and children’s entry into school, targeting kindergarten entry. Some children were assessed at entry into first grade due to families being unavailable during the kindergarten year, family decisions unknown to the lab to change the year their child started kindergarten, and/or COVID-related disruptions to study procedures (see Preliminary Analyses for tests related to this variation).

Measures

Maternal Comforting Behaviors

Maternal comforting behaviors were scored in the same manner across the Clown (low-threat) and Spider (high-threat) episodes according to previously established guidelines (Kiel & Buss, 2012). Comforting was scored by trained coders in each 10-s epoch of the episode for the maximum intensity observed on a 4-point scale (0 = none, 1 = touching child passively, 2 = active soothing, such as rubbing back or arm, 3 = full embrace/hug or kiss). For each non-zero score, it was also marked as solicited (in direct response to the child’s bid for reassurance, support, and/or comfort) or unsolicited (i.e., spontaneous by the mother). Coders maintained inter-rater reliability on both the comforting intensity score (ICC = 0.89) and the solicited versus unsolicited designation (kappa = 0.94). Scores were averaged across epochs separately for solicited and unsolicited scores within each of the two episodes, yielding four variables for analyses (solicited comforting – low-threat; unsolicited comforting – low-threat; solicited comforting – high-threat; unsolicited comforting – high-threat). Although it was technically possible for final scores (averages) to range from 0 to 3, this was not expected, as it was not realistic that many mothers were fully embracing or kissing their children throughout the entire task. Thus, final scores could be considered weighted proportions of epochs in which mothers demonstrated the relevant comforting behavior.

Toddler Inhibited Temperament

From the Risk Room episode, three coders used INTERACT (Mangold) software to score four behaviors according to established guidelines for scoring inhibited temperament (Buss & Goldsmith, 2000; Fox et al., 2001). Behaviors included the child’s latency to touch the first toy (number of seconds in between the start of the episode and the child’s first intentional physical contact with one of the five stimuli; ICC = 0.99), number of items touched (count from 0 to 5; kappa = 0.87), time (in seconds) spent playing with the stimuli (reverse-scored; ICC = 0.95), and time spent in proximity to their mother (in seconds; ICC = 0.96). Each of the four aforementioned behaviors were standardized by assigning z-scores, and the standardized scores were averaged (α = 0.83) for the final composite of inhibited temperament. As evidence of construct validity, similar Risk Room composites related to parent-reported temperamental fear, inhibition, and shyness, as well as psychobiological markers of inhibited temperament (e.g., cortisol reactivity) (Dyson et al., 2011; Kertes et al., 2009; Kiel & Buss, 2012; Volbrecht & Goldsmith, 2010). Further, the Risk Room is considered age appropriate for use in children in the first four years of life (Fox et al., 2001).

Family Accommodation

At the age 4 and school-age assessments, mothers completed the Family Accommodation Scale—Anxiety (FASA; Lebowitz et al., 2013), a 13-item questionnaire in which mothers endorse the frequency with which they have engaged in different accommodating behaviors over the past month (e.g., “Have you modified your work schedule because of your child’s anxiety?”). The questions are Likert-style, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (daily). Additionally, the FASA also assessed to what extent mothers felt their accommodating behaviors impacted their child’s mood (e.g. “Has your child’s anxiety been worse when you have not provided assistance? How much worse?”), with answers ranging from 0 (no) to 4 (extreme). The average of their responses (ɑs = 0.89, 0.90) became their overall FA score at each assessment.

The FASA has been shown to display both good convergent and divergent validity in child anxiety research. Scores on the FASA are significantly and positively related to child anxiety levels, which is congruent with theory suggesting that FA and child anxiety are positively associated (Lebowitz et al., 2013). Furthermore, the FASA does not significantly correlate to measures of childhood depression, demonstrating good divergent validity (Lebowitz et al., 2013). Factor analyses have demonstrated construct validity of the FASA in assessing FA for child anxiety (Norman et al., 2015). The FASA has been used to assess FA in families of children as young as 4 years old (e.g. Johnco et al., 2022; Thompson-Hollands et al., 2014).

Child Anxiety

At the age 4 and school-age assessments, mothers completed the Preschool Anxiety Scale (PAS: Spence et al., 2001) to report the frequency with which their child engaged in certain anxiety behaviors (e.g. “Worries that something bad will happen to his/her parents”). The first 28 items of the measure are scored from 0 (not at all true) to 4 (very often true) and were averaged (age 4 ɑ = 0.85, school-age ɑ = 0.89) to create a total score. The PAS has been shown to demonstrate good construct validity as it correlated positively with other measures of early childhood anxiety, such as the internalizing scale of the Child Behavior Checklist (Broeren & Muris, 2008; Spence et al., 2001). Additionally, the PAS has been used in children as young as 4 and has demonstrated good discriminant validity as scores differ significantly between parents of clinically anxious children and parents of sub-clinically anxious children (Broeren & Muris, 2008).

Results

Missing Values

Missing values occurred at age 2 according to the planned-missing recruitment design. Families joining the study at child age 4 did not differ from those who started at age 2 on maternal age, child sex, socioeconomic status (SES; the mean of z-scored maternal education, paternal education, and household income), or FA or child anxiety at either the age 4 or school-age assessments (all ps > 0.05). Families joining at age 4 did have younger children at that assessment (M = 50.36 months, SD = 3.77) than families who joined at child age 2 (M = 52.22 months, SD = 3.32; t[113] = -2.34, p = 0.021; Cohen’s d = -0.52).

Other missing values occurred because of attrition. Families lost to attrition between the age 2 and age 4 assessments (n = 47) did not differ on maternal age, child age, child sex, inhibited temperament, or any of the maternal comforting behaviors (all ps > 0.05), but they had lower SES (M = -0.29, SD = 0.84) than retained families (M = 0.11, SD = 0.81; t[134] = 2.54, p = 0.012; Cohen’s d = -0.48). Families lost to attrition between the age 4 and school-age assessments (n = 21) did not differ from retained families on any demographic or available primary variables. Families who participated in the age 2 but not the school-age assessment had higher high-threat solicited comforting behavior (M = 0.51, SD = 0.52) than families who completed both visits (M = 0.30, SD = 0.39; t[92.25] = 2.54, p = 0.013; Cohen’s d = 0.46).

Outside of planned missingness and attrition, three families did not complete the age 2 assessment despite having joined the study at an earlier assessment (all three completed the school-age assessment), and seven families completed other aspects of the age 2 assessment but not the laboratory observations of inhibited temperament and parenting. These 10 families did not differ from families who did complete toddler measures on demographic, age 4, or school-age measures (all ps > 0.05). In the cohort of families beginning at child age 2, who did not have any planned missingness, the pattern of missing values (considering primary variables and demographic characteristics) did not significantly deviate from a missing completely at random (MCAR) pattern (Little’s MCAR test: χ2[255] = 270.25, p = 0.245). Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation handled missing values in the primary model; thus, the sample size was 166 for tests of all hypotheses. This sample size, along with Type I error rate of 0.05, was adequately powered (0.80) to detect effects as small as f2 = 0.05 (small-medium) for a single regression coefficient after controlling for five additional variables in the model.

Preliminary Analyses

Preliminary analyses were completed in SPSS 25. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among primary variables are provided in Table 1. No variables showed severe deviation from a normal distribution (all |skew|< 3.00, all |kurtosis|< 10.00; Kline, 2016).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Pearson Correlations for Primary Variables

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Range | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Unsolicited comforting (HT) | 0.34 (0.34) | 0.00 – 1.45 | -0.27** | -0.03 | -0.07 | -0.08 | -0.03 | -0.24* | -0.21**** | -0.15 |

| 2. Solicited comforting (HT) | 0.38 (0.45) | 0.00 – 2.11 | – | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.25* | 0.05 | -0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| 3. Unsolicited comforting (LT) | 0.05 (0.09) | 0.00 – 0.50 | – | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.06 | |

| 4. Solicited comforting (LT) | 0.13 (0.23) | 0.00 – 1.31 | – | 0.21* | 0.45*** | 0.35** | 0.35** | 0.22**** | ||

| 5. Inhibited temperament | -0.01 (0.84) | -1.23 – 2.59 | – | 0.07 | 0.28* | 0.22**** | 0.18 | |||

| 6. Age 4 FA | 0.83 (0.61) | 0.00 – 3.89 | – | 0.47*** | 0.77*** | 0.58*** | ||||

| 7. Age 4 child anxiety | 0.64 (0.45) | 0.00 – 2.71 | – | 0.58*** | 0.71*** | |||||

| 8. School-age FA | 0.88 (0.68) | 0.00 – 3.78 | – | 0.60*** | ||||||

| 9. School-age child anxiety | 0.78 (0.49) | 0.00 – 2.97 | – |

The inhibited temperament variable represents a mean of z-scored behaviors. Statistics were computed prior to handling missing values

HT high-threat (spider task), LT low-threat (clown task), FA family accommodation

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; ****p < .10

We examined several demographic variables as potential covariates. Families who completed the school-age assessment after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (“COVID cohort;” n = 30) did not differ on child anxiety (t[101] = 0.50, p = 0.619, Cohen’s d = 0.11) but did report lower FA (M = 0.63, SD = 0.42) than families whose children entered kindergarten prior to 2020 (n = 74; M = 0.98, SD = 0.73; t[102] = 2.46, p = 0.015; Cohen’s d = 0.59). Child age at the school-age assessment did not relate to either FA (r = -0.13, p = 0.198) or child anxiety (r = -0.03, p = 0.756). SES related to FA at age 4 (r = -0.24, p = 0.019) and the school-age assessment (r = -0.21, p = 0.030), and child anxiety at age 4 (r = -0.23, p = 0.023). Maternal age (considered for inclusion as a covariate in previous studies of anxiety-relevant family processes, e.g., Johnco et al., 2022; Jones et al., 2015; Rapee et al., 2010) at birth of the target child was negatively related to FA at age 4 (r = -0.21, p = 0.049) and at the school-age assessment (r = -0.20, p = 0.041).

To identify uniquely important covariates, three preliminary multiple regression models tested dependent variables with more than one identified covariate (age 4 and school-age FA, age 4 child anxiety). Variables related to missingness and the demographic variables identified above as related to the relevant outcome were entered as simultaneous predictors. These models suggested that only SES should be included for age 4 outcomes, and that child age at the age 4 assessment and COVID cohort status (1 = entered kindergarten after COVID pandemic onset, 0 = entered kindergarten prior to COVID pandemic onset) should be included as covariates for school-age FA (see Online Supplement). High-threat solicited comforting was the only variable relevant to school-age child anxiety, so it was the only covariate on that path.

Primary Model

A single path model in Mplus version 7.3 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2014) using FIML estimation provided simultaneous tests of all hypotheses. The model included predictive paths from each of the comforting variables, inhibited temperament, and SES to age 4 FA and age 4 child anxiety. The model also included stability paths and cross-lagged paths between age 4 and school-age FA and child anxiety. Child age (in months) at the age 4 assessment and COVID cohort status at the school-age assessment were included as paths in relation to school-age FA. High-threat solicited comforting was included as a predictor of school-age child anxiety. The model included direct paths from low-threat solicited comforting to school-age outcomes. Model fit was acceptable based on a non-significant chi-square test (χ2[15] = 23.54, p = 0.073), root mean square error of approximation and standardized root mean square residual values < 0.08 (actual values = 0.06 and 0.04, respectively), and Tucker-Lewis index and comparative fit index values > 0.90 (actual values = 0.96 and 0.90, respectively) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Point estimates of paths were tested for significance, and symmetric confidence intervals are reported (Table 2). Effect sizes were estimated using standardized regression coefficients (β) and are reported in text, in addition to Table 2, for significant paths. Indirect effects were tested under the normal distribution (i.e., Sobel’s test) and more robustly using bootstrapped confidence intervals.

Table 2.

Path Model Coefficients

| Variable | b (SE) | β | t | p | 95% CI (b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV = Age 4 FA (R2 = .21) | |||||

| Intercept | 0.72 (0.12) | – | 6.01 | < 0.001 | 0.48, 0.95 |

| SES | -0.14 (0.07) | -0.20 | -1.96 | 0.050 | -0.28, 0.00 |

| Inhibited temperament | 0.00 (0.08) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.997 | -0.16, 0.16 |

| Unsolicited comforting – high-threat | -0.02 (0.19) | -0.01 | -0.09 | 0.929 | -0.39, 0.35 |

| Solicited comforting – high-threat | -0.04 (0.16) | -0.03 | -0.23 | 0.822 | -0.34, 0.27 |

| Unsolicited comforting – low-threat | 0.57 (0.67) | 0.08 | 0.85 | 0.394 | -0.75, 1.89 |

| Solicited comforting – low-threat | 1.03 (0.37) | 0.39 | 2.81 | 0.005 | 0.31, 1.75 |

| DV = Age 4 Child Anxiety (R2 = .21) | |||||

| Intercept | 0.72 (0.08) | – | 8.91 | < 0.001 | 0.56, 0.87 |

| SES | -0.10 (0.05) | -0.19 | -1.88 | 0.061 | -0.19, 0.00 |

| Inhibited temperament | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.21 | 2.06 | 0.039 | 0.01, 0.22 |

| Unsolicited comforting – high-threat | -0.30 (0.13) | -0.23 | -2.31 | 0.021 | -0.54, -0.05 |

| Solicited comforting – high-threat | -0.11 (0.10) | -0.11 | -1.07 | 0.284 | -0.31, 0.09 |

| Unsolicited comforting – low-threat | 0.21 (0.45) | 0.04 | 0.47 | 0.640 | -0.67, 1.10 |

| Solicited comforting – low-threat | 0.44 (0.22) | 0.23 | 2.03 | 0.042 | 0.02, 0.86 |

| DV = School-Age FA (R2 = .62) | |||||

| Intercept | 2.14 (0.76) | – | 2.81 | 0.005 | 0.65, 3.63 |

| COVID cohort | -0.36 (0.10) | -0.25 | -3.50 | < 0.001 | -0.56, -0.16 |

| Child age at age 4 assessment | -0.04 (0.01) | -0.21 | -2.62 | 0.009 | -0.07, -0.01 |

| Solicited comforting – low-threat | -0.10 (0.26) | 0.04 | -0.38 | 0.706 | -0.42, 0.62 |

| Age 4 FA |

0.58 (0.09) 0.09 |

0.55 | 6.55 | < 0.001 | 0.40, 0.75 |

| Age 4 child anxiety | 0.40 (0.12) | 0.27 | 3.42 | 0.001 | 0.17, 0.63 |

| DV = School-Age Child Anxiety (R2 = .52) | |||||

| Intercept | 0.17 (0.08) | – | 2.27 | 0.023 | 0.02, 0.32 |

| Solicited comforting – high-threat | 0.09 (0.11) | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.362 | -0.10, 0.28 |

| Solicited comforting – low-threat | -0.27 (0.22) | -0.13 | -1.23 | 0.219 | -0.69, 0.16 |

| Age 4 FA | 0.26 (0.07) | 0.32 | 3.59 | < 0.001 | 0.12, 0.40 |

| Age 4 child anxiety | 0.60 (0.09) | 0.54 | 6.36 | < 0.001 | 0.41, 0.78 |

The model showed good fit according to chi-square test (χ2[15] = 23.54, p = .073), RMSEA (0.06, 90% CI [0.00, 0.10], CFI (0.96), TLI (0.90), and SRMR (0.04). Also modeled were residual correlations between age 4 FA and age 4 child anxiety (r = .42, p < .001), and between school-age FA and school-age child anxiety (r = .24, p = .014)

FA family accommodation

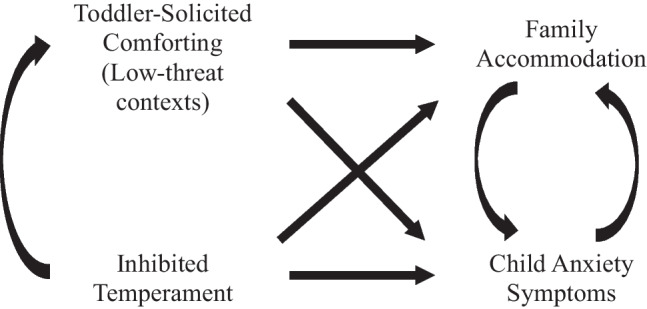

Path model results are reported in Table 2 and depicted in Fig. 2. Solicited comforting in the low-threat context uniquely predicted FA at age 4 (β = 0.39). Low-threat solicited comforting did not directly or indirectly predict school-age FA. Solicited comforting in the low-threat context predicted child anxiety at age 4 (β = 0.23). There was also a significant negative relation between unsolicited comforting in the high-threat context and child anxiety at age 4 (β = -0.23). Low-threat solicited comforting did not directly relate to school-age child anxiety; the indirect effect from low-threat solicited comforting to school-age child anxiety through age 4 FA was significant under the normal distribution (ab = 0.26, SE = 0.13, Z = 2.11, p = 0.035; 95% CI [0.02, 0.51]) and reached marginal significance when estimated with bootstrapping (ab = 0.26, SE = 0.22, 95% CI [-0.03, 0.86], 90% CI [0.01, 0.76]) due to producing a higher standard error.

Fig. 2.

Path Model Results. Note: Only statistics for significant paths are included. Coefficients represent standardized regression coefficients for single-headed arrows and correlations for double-headed arrows. Non-significant but tested paths are gray and dashed. Covariates of socioeconomic status, COVID cohort, and child age were analyzed but not depicted. For full model results, including model fit, see Table 2

Bi-directional associations existed between FA and child anxiety. Stability estimates (FA β = 0.55; child anxiety β = 0.54) were in the range of medium effects (Adachi & Willoughby, 2015). Above and beyond this stability, age 4 FA predicted school-age child anxiety (β = 0.32), and age 4 child anxiety predicted school-age FA (β = 0.27).

Sensitivity Analyses

Two sets of sensitivity analyses provided additional tests of the robustness of these relations. Full explanation of measures and results are reported in the Online Supplement. First, an analysis tested whether maternal anxiety may be a third variable explaining primary relations. Maternal anxiety did not relate to low-threat solicited comforting, nor did it relate to age 4 FA or child anxiety. Thus, the data did not provide evidence that the primary results were an artifact of broader consequences of maternal anxiety. Second, tests of bivariate associations of low-threat solicited comforting and FA with paternal report of child anxiety, which was available for a small subset of the sample at age 4 (n = 56) and the school-age assessment (n = 40) provided information about the contribution of shared method variance associated with maternal report of constructs. Most relations were replicated, suggesting they did not depend on shared method variance. However, age 4 FA did not relate to paternal, compared to maternal, report of school-age child anxiety as strongly (small effect size).

Discussion

To identify precursors of anxiogenic parent–child dynamics, the knowledge base requires constructs that are developmentally appropriate to early childhood and have construct validity for their involvement in children’s anxiety development. To this end, the current study examined toddler-solicited comforting behavior observed in a low-threat (i.e., mildly challenging and novel) context for a unique relation to both FA and child anxiety symptoms in the preschool and school-age years. Toddler-solicited comforting behavior in a low-threat context at age 2 predicted both FA (hypothesis 1) and anxiety symptoms at age 4 (hypothesis 2). Maternal perceptions of FA and anxiety symptoms then demonstrated further evidence of bidirectional associations, as each one predicted the other between age 4 and early school-age, above and beyond their own stability (hypothesis 3). Thus, toddler-solicited comforting behavior in situations that present only mild challenge may be an early indicator of child-directed anxiogenic family processes.

Toddler-solicited comforting behavior in low-threat contexts has previously been linked to other predictors of child anxiety, including inhibited temperament, social withdrawal, and maternal anxiety (Kiel & Buss, 2012; Kiel et al., 2021). However, robust evidence of solicited comforting as a specific predictor of risk required that similarities between it and unsolicited (i.e., spontaneous) comforting behavior, as well as between it and solicited comforting in other contexts, be controlled. This is the first study to offer such evidence. Thus, affectionate parenting does not unilaterally relate to anxiety risk; rather, in some circumstances, overly warm and reassuring parenting may reflect anxiogenic family processes. Two distinguishing features of solicited comforting in low-threat contexts are highlighted below.

The first important distinction is that it is comforting behavior directly elicited by the child, rather than spontaneously exhibited by caregivers, that may maintain children’s existing anxiety risk over time. Given that children’s own dispositional characteristics, particularly inhibited temperament, appear to drive the solicited comforting response (Kiel et al., 2021), solicited comforting behavior may be involved in maintaining, rather than creating, child risk for anxiety. The current results contribute to the increasing quantity and quality of evidence for child-driven effects on anxiety risk (e.g., Gouze et al., 2017; Hastings et al., 2019; Pérez-Edgar et al., 2021a, b) and suggest that theory and empirical research avoid explicit or implicit messages that caregivers are driving their children’s anxiety. Caregivers, particularly during the challenging period of toddlerhood, are likely doing their best to be responsive to the child in the situation at hand. When toddlers place demands on their caregivers for comfort and reassurance it stands to reason that caregivers’ natural response is to provide such comfort and reassurance. Unfortunately, these types of interactions, when occurring in situations in which toddlers might practice independent coping, may maintain toddlers’ avoidance of novelty and uncertainty (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998) and contribute to the development of an anxious-coercive cycle (Dadds & Roth, 2001).

Of course, there may be caveats to the notion that the maintenance of anxiety risk in early childhood is child-driven. The comforting behaviors studied presently, both solicited and unsolicited, were often subtle. There may be instances of spontaneous comforting parenting behaviors that reach an extremity not observed in the sample that could affect the onset of anxiety risk. Also, not all parents respond to toddlers’ (even anxious toddlers’) bids for support and reassurance with high levels of affection, so parent characteristics may increase or decrease the likelihood of this dynamic. Although parental anxiety is often linked to similar parenting behaviors (e.g., overprotection; Cooklin et al., 2013; Fliek et al., 2015), the supplemental analyses did not support its role in the current results. In fact, maternal anxiety may be a correlate and outcome, rather than antecedent, of toddler-solicited comforting behavior (Kiel et al., 2021). The extent to which caregivers anticipate their toddlers’ distressed responses to novelty and uncertainty, as well as caregivers’ goals for their children in those situations, may increase the likelihood of comforting responses to their toddlers’ bids for support (Kiel & Buss, 2012). Parents’ own caregiving experiences may also shape their responses to their children (Murray et al., 2019). Continued research into parents’ cognitions and emotion processes related to solicited comforting could bring additional specificity to the unfolding of parent–child interactions in uncertain situations. Importantly, toddler-solicited comforting in a low-threat context predicted child anxiety independently from toddler inhibited temperament, which itself was a significant predictor. Thus, even as a child-directed behavioral interaction, solicited comforting is contributing to risk above and beyond children’s temperamental disposition. Parent–child interactions, even as a manifestation of children’s characteristics, are specifically important to address in both research and applied work.

The second important distinction is that the low-threat nature of the context differentiated anxiety-relevant comforting behavior from comforting behavior (in a high-threat context) that was unrelated (or negatively related) to continued anxiety risk. Theory surrounding the development of emotion regulation suggests that over the course of toddlerhood, children navigate a crucial shift between relying solely on their caregivers for external regulation of their emotional experiences to increasingly engaging in independent, internal regulation (Kopp, 1989). It would be expected, therefore, that toddlers would be able to practice independent coping in situations that are challenging enough to require regulation, but are not so challenging as to exceed their resources. Only in the low-threat context, then, would parenting behavior that could take the place of independent coping be related to anxiety-relevant outcomes. Accordingly, the current study focused on parenting behavior that serves to externally regulate toddlers in situations that varied according to their demands. The “low-threat” task was novel and requested toddlers’ interaction, but it also involved features that were likely familiar to toddlers (i.e., a friendly tone, games and toys). Previous work has validated this task as a context that most children find engaging and non-distressing and therefore highlights children showing distressed and withdrawn responses as at-risk for anxiety (Buss, 2011). On the other hand, the “high-threat” task involved more uncertainty (e.g., sudden movement of a previously stationary toy), resembled the source of a common phobia for young children (a spider), and was more intrusive (the spider approached to within close proximity of child). Previous work has shown that fear responses in this episode are normative and not related to anxiety risk (Buss, 2011). This suggests that parental intervention is required for children’s regulation and does not prevent the opportunity for children to practice independent regulation. Comforting behavior in this high-threat context did not predict children’s maintained risk for anxiety later in childhood. Indeed, mothers’ spontaneous displays of comfort predicted lower levels of child anxiety two years later. By characterizing comforting behavior both in terms of being solicited/unsolicited and low-threat/high-threat, these results provide some specificity to theory surrounding how parents might tailor their responsiveness to toddlers’ fear and withdrawal to the context of the situation.

Toddler-solicited comforting behavior directly predicted FA, suggesting these may be developmentally-specific but related manifestations of child-elicited parenting responses. As anxiety-prone children develop more sophisticated language and motor skills and become more physically autonomous, the consequences of their anxiety may shift from seeking physical comfort in situations to which their parents bring them, to more extreme refusals to travel to or participate in various activities. These increasingly severe responses may then prompt parents to avoid or cancel plans and activities that evoke an anxious response (Lebowitz et al., 2013). The current results suggest that this developmental pattern from toddler-solicited comforting behavior to FA can be identified in a non-clinical, community sample. Future research might focus on the developmental mechanisms that link toddler-solicited comforting behavior to FA, or the boundaries of this relation.

The current study also contributed to the literature by demonstrating a bidirectional relation between FA and child anxiety as children move from the preschool to school-age periods. The important foundational research on the relation between FA and child anxiety has largely come from clinical samples and concurrent designs (Calvocoressi et al., 1995; Johnco et al., 2022; Lebowitz et al., 2013; Thompson-Hollands et al., 2014). Although the reciprocal, mutually reinforcing nature of FA and child anxiety is a crucial aspect of the theory behind FA, little empirical evidence is available to support more long-standing bidirectional patterns. FA and child anxiety predicted each other over one year, even after accounting for the moderate stability existing for each construct. This by itself contributes to theory surrounding FA and also demonstrates that the consequences of toddler-solicited comforting behavior are likely to be maintained over time.

The results of this study should be considered in light of several methodological limitations. Although the sample was characterized by socioeconomic diversity, it, like the larger literature, was predominantly White and, on average, in the middle range of social class. Thus, the results of this study are most appropriately generalized to White, fairly well-resourced families. Although heterogeneity of parenting behavior and child outcomes would be expected within any given cultural group, culture imbues the values and beliefs that parents communicate to their children through caregiving responses (Raval & Walker, 2019). As such, the parenting behavior studied herein, as well as its consequences for child outcomes, is likely heavily influenced by White culture in the United States, which is characterized as valuing individualism, independence, and autonomy (Raval & Walker, 2019). The data cannot speak to how these patterns would or would not replicate in samples characterized by other identities, particularly identities that are minoritized and oppressed in the US. Next, the sample comprised only caregivers identifying as children’s mothers. This choice was made because mothers continue to perform most caregiving responsibilities for toddlers (Möller et al., 2016). However, it must be acknowledged that fathers make important contributions to their children’s development and also are involved in anxiety risk and resilience processes (Möller et al., 2016). Moreover, other caregivers who do not identify as parents remain understudied, both in general and in anxiety development, specifically. Although a contemporary approach handled missing values in order to maximize participants’ contributions and minimize bias in analyses, the existence and extent of missing data is a limitation. Finally, longitudinal analyses between FA and child anxiety were affected by shared method variance, as both variables were derived from maternal report. Controlling for stability in each construct allowed each participant to act as their own control over time, statistically controlling for biases or other factors outside of true scores that would artificially inflate relations. Supplemental analyses replicated most correlations when paternal report substituted for maternal report of child anxiety. However, relations involving school-age child anxiety were lower with paternal compared to maternal report. The subsample of fathers was small compared to the larger sample. Thus, these results should be interpreted with some caution. That being said, shared method variance should be considered both in the current results and in future studies of FA and child anxiety symptoms.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the findings of the current study have several clinical implications for anxiety prevention and early intervention efforts. There exist a number of successful interventions for anxiety-prone preschool-aged and young children and their families (e.g., Rapee et al., 2010). As these programs continue to be refined, the current results suggest an emphasis on child-directed effects on parents in the provision of physical comfort and/or FA. Parents may require support beyond psychoeducation to change behaviors that appear (and feel) sensitive and responsive to their children’s distress but may ultimately reinforce avoidance. Parents may also benefit from training in differentiating situations that require their support from those than offer opportunities for children to practice independent coping.

Conclusion

Toddler-solicited maternal comforting behavior, when exhibited in low-threat or mildly challenging situations, may uniquely reflect early child-driven, anxiogenic family processes characterized by child anxiety and FA later in development. These results add to the construct validity of toddler-solicited maternal comforting behavior as an indicator of child anxiety risk in White, middle-class families. Further, FA and child anxiety symptoms showed bidirectional relations from preschool to school-age periods in this community sample. Collectively, results augment theory surrounding the developmental psychopathology of anxiety, particularly in parsing risk from adaptive parent–child interactions and in acknowledging children’s contribution to their own development.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the larger longitudinal study from which these data were derived came from the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (2R15 HD076158 to Elizabeth J. Kiel). Both authors were supported by funding from the National Institute for Mental Health (R01 MH113669 to Rebecca Brooker and Elizabeth J. Kiel) during the writing of the manuscript. We thank the supporting staff of the Behavior, Emotions, and Relationships Lab at Miami University, as well as the families participating in the study.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, visualization, supervision, project administration, and funding were performed by Elizabeth J. Kiel. Investigation and writing of the original draft of the manuscript were performed by Elizabeth J. Kiel and Nicole M. Baumgartner.

Data Availability

The study was not preregistered. Data and code for the study are available at https://osf.io/7rf4t/?view_only=2e79b56782214850a11394284760f252

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adachi, P., & Willoughby, T. (2015). Interpreting effect sizes when controlling for stability effects in longitudinal autoregressive models: Implications for psychological science. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 12, 116–128. https://doi.org/ggh7xj

- Bögels, S. M., & Brechman-Toussaint, M. L. (2006). Family issues in child anxiety: Attachment, family functioning, parental rearing and beliefs. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 834–856. https://doi.org/bg78cz [DOI] [PubMed]

- Broeren, S., & Muris, P. (2008). Psychometric evaluation of two new parent-rating scales for measuring anxiety symptoms in young Dutch children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 949–958. https://doi.org/bpq5r6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Buss, K. A. (2011). Which fearful toddlers should we worry about? Context, fear regulation, and anxiety risk. Developmental Psychology, 47(3), 804–819. https://doi.org/btq7n2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Buss KA, Goldsmith HH. Manual and normative data for the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery Toddler Version. University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Calvocoressi, L., Lewis, B., Harris, M., Trufan, S. J., Goodman, W. K., McDougle, C. J., & Price, L. H. (1995). Family accommodation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152(3), 441–443. https://doi.org/ggqhv6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, J. (1994). Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2–3), 228–249. https://doi.org/dfmtq7 [PubMed]

- Chorpita, B. F., & Barlow, D. H. (1998). The development of anxiety: The role of control in the early environment. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 3–21. https://doi.org/bvx6hx [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cooklin, A. R., Giallo, R., D’Esposito, F., Crawford, S., & Nicholson, J. M. (2013). Postpartum maternal separation anxiety, overprotective parenting, and children’s social-emotional well-being: Longitudinal evidence from an Australian cohort. Journal of Family Psychology, 27, 618–628. https://doi.org/jcpm [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dadds MR, Roth JH. Family processes in the development of anxiety problems. In: Vasey MW, Dadds MR, editors. The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 278–303. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, M. W., Klein, D. N., Olino, T. M., Dougherty, L. R., & Durbin, C. E. (2011). Social and non-social inhibition in preschool-age children: Differential associations with parent-reports of temperament and anxiety. Child Psychiatry and Human Behavior, 42, 390–405. https://doi.org/fwr9pd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Feinberg, L., Kerns, C., Pincus, D. B., & Comer, J. S. (2018). A preliminary examination of the link between maternal experiential avoidance and parental accommodation in anxious and non-anxious children. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 49, 652–658. 10.1007/s10578-018-0781-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fliek, L., Daemen, E., Roelofs, J., & Muris, P. (2015). Rough-and-tumble play and other parental factors as correlates of anxiety symptoms in preschool children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 2795–2804. https://doi.org/f7ntng

- Fox, N. A., Henderson, H. A., Rubin, K. H., Calkins, S. D., & Schmidt, L. A. (2001). Continuity and discontinuity of behavioral inhibition and exuberance: Psychophysiological and behavioral influences across the first four years of life. Child Development, 72, 1–21. https://doi.org/c2dzd2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gouze, K. R., Hopkins, J., Bryant, F. B., & Lavigne, J. V. (2017). Parenting and anxiety: Bi-directional relations in young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45, 1169–1180. https://doi.org/gbqhx5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hastings, P. D., Grady, J. S., & Barrieau, L. E. (2019). Children’s anxious characteristics predict how their parents socialize emotions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47, 1255–1238. https://doi.org/jcpn [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hudson, J. L., & Rapee, R. M. (2001). Parent-child interactions and anxiety disorders: An observational study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39, 1411–1427. https://doi.org/b33jdb [DOI] [PubMed]

- Johnco, C., Storch, E. A., Oar, E., McBride, N. M., Schneider, S., Silverman, W. K. & Lebowitz, E. R. (2022). The role of parental beliefs about anxiety and attachment on parental accommodation of child anxiety. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 50, 51–62. https://doi.org/jcpp [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jones, J. D., Lebowitz, E. R., Marin, C. E., & Stark, K. D. (2015). Family accommodation mediates the association between anxiety symptoms in mothers and children. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 27(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/jcpq [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kagan, J., Reznick, J. S., Clarke, C., Snidman, N. & Garcia-Coll, C. (1984). Behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. Child Development, 55, 2212–2225. https://doi.org/brtnqk

- Kerns, C. E., Pincus, D. B., McLaughlin, K. A., & Comer, J. S. (2017). Maternal emotion regulation during child distress, child anxiety accommodation, and links between maternal and child anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 50, 52–59. https://doi.org/gbvg29 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kertes, D. A., Donzella, B., Talge, N. M., Van Ryzin, M. J., & Gunnar, M. R. (2009). Inhibited temperament and parent emotional availability differentially predict young children’s cortisol responses to novel social and nonsocial events. Developmental Psychobiology, 51, 521–532. https://doi.org/dbxtmc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kiel, E. J., Aaron, E. M., Risley, S. M., & Luebbe, A. M. (2021). Transactional relations between maternal anxiety and toddler anxiety risk through toddler-solicited comforting behavior. Depression and Anxiety, 38(12), 1267–1278. https://doi.org/jcps [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kiel, E. J., & Buss, K. A. (2012). Associations among context-specific maternal protective behavior, toddlers’ fearful temperament, and maternal accuracy and goals. Social Development, 21(4), 742–760. https://doi.org/f4b6hb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 4. Guilford Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp, C. B. (1989). Regulation of distress and negative emotions: A developmental view. Developmental Psychology, 25(3), 343–354. https://doi.org/dq2ftf

- Lebowitz, E. R., Panza, K. E., & Bloch, M. H. (2016). Family accommodation in obsessive-compulsive and anxiety disorders: A five-year update. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 16(1), 45–53. https://doi.org/gh57rc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lebowitz, E. R., Scharfstein, L. A., & Jones, J. (2014). Comparing family accommodating in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety disorders, and nonanxious children. Depression and Anxiety, 31, 1018–1025. https://doi.org/f6tstt [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lebowtiz, E. R., Woolston, J., Bar-Haim, Y., Calvocoressi, L., Dauser, C., Warnick, E. Scahill, L., Chakir, A. R., Scechner, T., Hermes, H., Vitulano, L. A., King, R. A., & Leekman, J. F. (2013). Family accommodation in pediatric anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 30, 47–54. https://doi.org/gh57vt [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Möller, E. L., Nikolić, M., Majdandžić, M., & Bögels, S. M. (2016). Associations between maternal and paternal parenting behaviors, anxiety, and its precursors in early childhood: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 17–33. https://doi.org/ggxbsp [DOI] [PubMed]

- Morris, A. S., Criss, M. M., Silk, J. S., & Houltberg, B. J. (2017). The impact of parenting on emotion regulation during childhood and adolescence. Child Development Perspectives, 11, 233–238. 10.1111/cdep.12238

- Murray L, Richards MPM, Nihouarn-Sigurdardottir J. Mothering. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting. Routledge; 2019. pp. 36–63. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2014). Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- Nachmias M, Gunnar M, Mangelsdorf S, Parritz RH, Buss K. Behavioral inhibition and stress reactivity: The moderating role of attachment security. Child Development. 1996;67:508–522. doi: 10.1111/dhx6tm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman, K. R., Silverman, W. K., & Lebowitz, E. R. (2015). Family accommodation of child and adolescent anxiety: Mechanisms, assessment, and treatment. Journal and Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 28, 131–140. https://doi.org/f7275r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Edgar, K., LoBue, V., & Buss, K. A. (2021a). From parents to children and back again: Bidirectional processes in the transmission and development of depression and anxiety. Depression and Anxiety, 38, 1198–1200. https://doi.org/jcpt [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Edgar K, LoBue V, Buss KA, Field AP. Study protocol: Longitudinal attention and temperament study. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021;12:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.656958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee, R. M., Kennedy, S. J., Ingram, M., Edwards, S. L., & Sweeney, L. (2010). Altering the trajectory of anxiety it at-risk young children. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 1518–1525. https://doi.org/fmfsds [DOI] [PubMed]

- Raval, V. V., & Walker, B. L. (2019). Unpacking ‘culture’: Caregiver socialization of emotion and child functioning in diverse families. Developmental Review, 51, 146–174. https://doi.org/gmzghp

- Sameroff A. A dialectic integration of development for the study of psychopathology. In: Lewis M, Rudolph KD, editors. Handbook of developmental psychopathology. 3. Springer; 2014. pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Settipani, C. A., & Kendall, P. C. (2017). The effect of child distress on accommodation of anxiety: Relations with maternal beliefs, empathy, and anxiety. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(6), 810–823. 10.1080/15374416.2015.1094741 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Spence, S. H., Rapee, R., McDonald, C., & Ingram, M. (2001). The structure of anxiety symptoms among preschoolers. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39(11), 1293–1316. https://doi.org/fth75d [DOI] [PubMed]

- Thompson-Hollands, J., Kerns, C. E., Pincus, D. B., & Comer, J. S. (2014). Parental accommodation of child anxiety and related symptoms: Range, impact, and correlates. Journal of Anxiety Disorder, 28, 765–773. https://doi.org/gh57vv [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Volbrecht, M. M., & Goldsmith, H. H. (2010). Early temperamental and family predictors of shyness and anxiety. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1192–1205. https://doi.org/c93gsn [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The study was not preregistered. Data and code for the study are available at https://osf.io/7rf4t/?view_only=2e79b56782214850a11394284760f252