Abstract

The prevalence of infectious diseases in the aquaculture industry and a limited number of safe and effective oral vaccines has imposed a challenge not only for fish immunity but also a threat to human health. The availability of fish oral vaccines has expanded recently, but little is known about how well they work and how they affect the immune system. The unsatisfactory efficacy of existing oral vaccinations is partly attributable to the antigen degradation in the adverse gastrointestinal environment of fishes, the highly tolerogenic gut environment, and inferior vaccine formulation. To overcome such challenges in designing: an easier, cost-efficient, and effective vaccination method, several encapsulation methods are being adopted to safeguard antigens from the intestinal atmosphere for their immunogenic functions. Oral vaccination is easily degraded by gastric acids and enzymes before reaching the immunological site; however, this issue can be solved by encapsulating antigens in poly-biodegradable nanoparticles, transgenic designed bacteria, plant systems, and live feeds. To enhance the immunological impact, each antigen delivery method operates at a different level. Utilizing nanotechnology, it has been possible to regulate vaccination parameters, target particular cells, and lower the antigen dosage with potent nanomaterials such as chitosan, poly D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) as vaccine carriers. Live feeds such as Artemia salina can be utilized as bio-carrier, owing to their appropriate size and non-filter feed system, through a process called bio-encapsulation. It ensures the protection of antigens over the fish intestine and ensures complete uptake by immune cells in the hindgut for increased immune response. This review comprises recent advances in oral vaccination in aquaculture in terms of an encapsulation approach that can aid in future research.

Keywords: Aquaculture, Oral vaccination, Mucosal immunity, Chitosan, Artemia salina, Bio-encapsulation

Introduction

Aquaculture and fisheries are one among the fastest growing food production sectors over the years and the most important key factor in terms of nutritional assurance to the food sector, contribution to agricultural exports, and source of employment to around fourteen million people in various commercial activities (Lakra and Gopalakrishnan 2021). With diverse and abundant aquatic resources, continuous and sustained increase in the economy could be contributed by the sector if aquaculture growth conditions are appropriate (Zacharia et al. 2016). Several environmental changes and anthropogenic activities such as pollution have put fish populations under immense stress and more susceptible to diseases. As a result, a wide range of diseases has emerged and declined the progress of aquaculture sector (Little et al. 2016). Although antibiotics or chemotherapeutics may be used to treat aquatic diseases, there are some obvious disadvantages, such as drug resistance and safety concerns. There comes the vaccination process which is the method of inducing protective immune responses in fishes against infectious pathogens by exposing them to non-pathogenic forms or components of microorganisms (Topp et al. 2018). Vaccination contributes to the environmental, social, and economic sustainability of global aquaculture as an effective technique of combating a wide range of bacterial and viral diseases. A conventional fish vaccine comprises or creates a molecule that functions as an antigen. This component subsequently activates the innate and/or adaptive immune response of fish against a specific disease (Harikrishnan et al. 2011). The predominant antibody type seen in several fishes is an immunoglobulin IgM-like isotype that normally occurs as a pentamer in its secretory form (Yu et al. 2020). In fishes, no isotypes comparable to mammalian IgG, IgA, or IgE have been discovered. Fishes possess a weaker secondary humoral immune response than mammals, assuming it does not exist at all. The inability to examine pathogen and vaccine-induced immunity in diverse fish species due to a lack of extensive information on their immune systems still exists (Sommerset et al. 2005). In consideration of the idea of vaccination, the route of administration of vaccines also plays a major role in effectiveness, since certain fishes are too susceptible to handle the stress during vaccination and simultaneous post-vaccination effects. However, in some species, serious illness concerns may occur during the larval or fry stages, before the animal is large enough to be vaccinated and the onset of the development of a functional immune system (Muktar and Tesfaye 2016).

Limited or insufficient maternal immunity also seems to be a factor in the reduced protection of fish offspring by parental vaccination. Duff pioneered fish vaccination in 1942, when he successfully immunized trout against the bacteria Aeromonas salmonicida (Shaalan et al. 2018). In general, there are three types of fish vaccines, inactivated whole-cell vaccines, live-attenuated vaccines, and recombinant DNA-based vaccinations (Fig. 1). Adjuvants, immune-stimulants, and vaccine carriers have increased the efficacy of these vaccinations (Embregts and Forlenza 2016). Mineral oils and other traditional adjuvants, such as Freund’s Complete Adjuvant (FCA), Freund’s Incomplete Adjuvant (FIA), and, more recently, Montanide, have been frequently used for vaccination in aquaculture. Although adjuvants are particularly successful at amplifying the immune response against pathogens, they have a variety of adverse effects. The routes of vaccination delivery, however, continue to have a major effect. Commercial vaccinations are given orally (by combining with the feed or enrichment), by immersion (dip or bath), or by injection through the intraperitoneal (i.p.) or intramuscular (i.m.) routes, depending on the age and size of the fish (Embregts and Forlenza 2016).

Fig. 1.

Characteristic types and various routes of administration of existing aquatic vaccines

Intraperitoneal injection is the most common method for delivering emulsion-based injectable vaccines, whereas intramuscular injection is the most common method for delivering DNA plasmids (Tafalla et al. 2014). While injectable vaccination provides better immunity, it is often accompanied with intense handling and stress for the fish (Table 1). In that aspect, without doubt the mucosal route of vaccination, particularly the oral route, would be the optimal mode of vaccine administration in terms of animal wellbeing and handling processes which is the centralized idea to be delivered through this review along with recent evolved approaches (Meeusen et al. 2007).

Table 1.

Vaccination delivery methods in aquaculture

| Vaccine method | Route of administration | Advantages | Disadvantages | Commercial vaccine | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immersion | Dip immersion Bath immersion Spraying | Mass application Cost-effective Better immune response (up to 5 months) | Difficulty in applicability over existing large units Large quantity requirement Expensive | Inactivated vaccine against vibriosis in salmonids, sea bass through immersion | Sughra et al. (2021) Colquhoun and Lillehaug (2014) |

| Injection | Intramuscular Intraperitoneal | Better immune protection up to 1 year Suitable for large fish Easy formulation Effective for weak antigen Boosters not needed | Stressful Difficulty in large-scale application | Glycoprotein subunit vaccine against Spring viremia of carp virus through injection | Evensen (2009) Ahne et al. (2002) |

| Oral vaccination | Feed formulation Bio-encapsulation Micro-encapsulation | Not stressful Easy application Cost-effective Large-scale application | Subjective to digestive enzyme degradation Appropriate carrier systems are needed | Commercial Vibrio anguillarum oral vaccine in two types of alginate microspheres in Carp and rainbow trout | Romalde et al. (2004) |

Oral vaccination—protection status in aquaculture

The most significant form of aquaculture vaccination is oral vaccination. Oral vaccines can be administered either through the enrichment of formulated feed, through encapsulating in a diverse range of polymers, or by the process of bio-encapsulation in live feeds such as rotifers, daphnia, and artemia. In formulated feeds, oral vaccines are designed either through coating the antigen over the feed by spray method or mixing the antigen into the feed during their manufacturing process for co-processing. Antigen delivery through oral means has the advantages of being stress-free and simple to administer to a large number of fishes simultaneously (Mutoloki et al. 2015). Administration of oral vaccines through formulated feeds is associated with a chance that the antigen will be digested by the fish digestive enzymes. In that aspect, an approach involved the administration of a vaccine to a live feed and then feeding it to the fry of fish species (Embregts and Forlenza 2016). The vaccine is considered to become bio-encapsulated into the lipid composition of live feed organisms which prevents it from the degradation of fish digestive enzymes (Samat et al. 2020). Mass vaccination of fish entirely through live feeds will be a significant practice due to the high costs of vaccine production essential for injection and immersion immunization or the low efficiency of existing oral formulations (Sudheesh and Cain 2017). Such vaccination strategies have been applicable for current vaccine applications in large-scale fish farming operations, including inactivated, live-attenuated, recombinant, and DNA vaccines in a diverse species of fish utilizing different live feeds (rotifers, daphnia, artemia, etc.) as effective carriers.

The oral route is the most appealing method of immunization in aquaculture for a variety of reasons, including the ease with which antigens are administered, the fact that it is less stressful than parenteral delivery, applicability to all sizes of fish, and it provides a procedure for oral boosting of fish larvae during growth periods in culture ponds (Snieszko 1954). Despite these benefits, there are currently very few licensed oral vaccinations for applicability in the aquaculture sector. This low number was attributable to the lack of immune response to oral vaccinations in general when compared to injectable vaccines. This is due to the antigen degradation during transit through the hostile stomach environment prior to reaching the hindgut of the intestine where the absorption process occurs (Mutoloki et al. 2015). In an earlier analysis, orally administered vaccinations, particularly those containing inactivated whole antigens resulted in insufficient immune protection against a variety of infections. Later research was focused on better formulations and specific route administrations of oral vaccinations that can improve or offer prolonged protection in the larval stage fish. Such oral formulations must consider various factors with great significance such as dosage of vaccine, nature of antigens, formulations, and compartmentalization of the target host immune system for a clear vision of the process of immune reactions.

In higher vertebrates, antigens delivered through the gut are uptaken by the cells lining the organ, such as enterocytes and M cells, aiding in both systemic and localized immune reactions without degrading the antigen (Lavelle et al. 1997). Fish gut being different from that of mammalian gut possesses a functional Gut Associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT) that has the ability to mount local immune responses. Indeed, antigen delivery causes the upregulation of genes involved in immune cell recruitment and local antibody driving reactions to the site. Local and systemic immune responses will be induced when antigens are given via the gut, as evidenced by high levels of circulating IgM in comparison with the parenteral administration which elicit systemic immune response alone (Parra et al. 2016). Oral vaccinations have several drawbacks, including the necessity for a large number of antigens, the need to preserve antigens as they transit through the stomach, and the composition of vaccines to increase the stimulation of protective immunity (Hwang et al. 2020). Certain advancements carried out by the scientific community to enhance the frontier of oral vaccinology in fishes are better scale-up antigen production for bacteria and virus-based pathogens, diverse inactivation technologies for native whole-cell antigens, and production of subunit vaccines in heterologous protein expression systems in bacteria and yeast. Escherichia coli and yeast are the most often employed protein expression systems for the manufacture of subunit antigens in fish vaccines (Hwang et al. 2020).

Based on these procedures, commercial oral vaccinations have been employed in the past or are now being produced (Table 2). Utilization of plant-based systems for the production of oral subunit antigens is also in the process over these years. For example, Tobacco cultivars Bright Yellow (Vinaya et al. 2019) (BY-2) and Nicotiana tabacum 1 (NT-1) are the most popular plant expression systems being used. At the experimental level, inducing protection against infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV) as an oral vaccination has been found to be advantageous. Oral bacterial vaccines have the same difficulties in comparison with viral formulations, such as antigen breakdown as they transit through the stomach, and there is a need for high-quantity production for effective vaccination (Piganelli et al. 1994). Villumsen et al. (2014) in their study against enteric redmouth disease (ERM) in rainbow trout found that anally delivered vaccines provided better protection for fish than orally administered vaccines, with the claim that that orally supplied antigens along with their supplement feeds were digested in the stomach. In another work, immunization of common carp with LTB-influenza-parvo fusion protein through the anal route led to the increased production of antigen-specific IgM titers in serum (Companjen et al. 2006). As a result, various research has been undertaken to determine the optimum strategy for protecting bacterial antigens in the stomach of fish (Mutoloki et al. 2015).

Table 2.

Significant oral vaccines against aquatic diseases, their causative pathogens, and hosts

| Disease | Vaccine | Pathogen/target antigen | Host fish species | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vibriosis | Oral inactivated | Vibrio anguillarum Vibrio ordalii Vibrio salmonicida Vibrio alginolyticus | Salmonids, sea bass, sea bream, cod | Li et al. (2015) |

| Motile Aeromonas septicemia (MAS) | Whole-cell polyvalent feed-based vaccine | Aeromonas spp. | Asian seabass, Lates calcarifer | Mohamad et al. (2021) |

| Streptococcus infections | Bacillus subtilis GC5 surface displayed oral vaccine | Streptococcus agalactiae | Tilapia | Yao et al. (2019) |

| Koi herpes virus disease | Chitosan-alginate encapsulated oral vaccine | Koi Herpesvirus (KHV) ORF81 | Carp | Huang et al. (2021) |

| Spring viremia of carp (SVC) | Chitosan-alginate encapsulated oral probiotic vaccine | Spring viremia of carp virus | Cyprinus carpio | Bøgwald and Dalmo (2021) |

Types of oral aquatic vaccines

Oral aquatic vaccines have traditionally been made up of conventional methods that consist of inactivated entire organisms, although certain live-attenuated or subunit protein vaccines (formulated with adjuvants) have been produced (Ulmer et al. 2012). Fish vaccines in the past were made up of formalin-killed microorganisms, delivered with or without the presence of an adjuvant. These were administered to fishes through immersion or injection methods that resulted in the induction of humoral immunity (Ma et al. 2019). During that period, some forms of live-attenuated vaccines were also commercialized and were in use. Those vaccinations have proven to be effective, resulting in enhanced commercial aquaculture productivity and a decrease in the usage of chemical therapies and antibiotics administered through feeds (Mutoloki et al. 2015).

Live-attenuated oral vaccines

One or more viruses or bacteria modified to express decreased virulence or inherent low pathogenicity towards the target fish species are used to generate attenuated live vaccines. Physical or chemical methods, the serial passage in cell culture, cultivation under aberrant circumstances, and molecular genetic modification are the common methods used for attenuating live pathogens for vaccine production (Locke et al. 2008). Such vaccines mimic live pathogenic infection and route that aids in stimulating a strong immune response that upregulates immune factors both associated with innate and adaptive immunity of aquaculture. Such vaccines similar to live pathogens frequently replicate inside the host, allowing the animal to build sufficient cellular memory and so generate long-lasting immunity, which is clearly advantageous in all levels of aquatic organisms (Shoemaker et al. 2011). Live-attenuated vaccines often limit the use of adjuvants due to their effective immune response even at the first dose. Live vaccines are made effective, with better design of their administration route. Live vaccines have a better potential to be delivered via the oral route in commercial aquaculture applications. As a result, unlike inactivated vaccines that require adjuvants, the manner of delivery is more dynamic (Pridgeon and Klesius 2011). Due to the presence of Pathogen Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs) that can generate stimulatory signals, live-attenuated enteric pathogens can penetrate and reproduce at the mucosal surface and induce appropriate mucosal responses even in the absence of adjuvants (Embregts and Forlenza 2016). Live-attenuated vaccines are effective in most cases but still possess a risk if they revert to their virulent form causing infectious diseases and are pathogenic in immunocompromised vaccinates or tend to possess residual virulence in aquaculture. Examples of some live-attenuated oral vaccines in aquaculture include an Arthrobacter vaccination for salmonids against bacterial kidney disease (BKD) (Elliott et al. 2014), a Flavobacterium columnare vaccine for catfish columnaris (Shoemaker et al. 2011), live viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) vaccine (Nishizawa et al. 2011), a live viral vaccine against Koi herpesvirus (KHV) for carp, attenuated vaccine of V. anguillarum in rainbow trout (Hu et al. 2020), an attenuated vaccine for Flavobacterium psychrophilum in salmonids, and live-attenuated Edwardsiella ictaluri oral vaccine in the channel and hybrid catfish (Starliper 2011). A similar approach was found in designing an oral vaccine for Japanese flounder against Edwardsiella tarda (E. tarda). Although the time of vaccination administration and duration of protection need to be optimized (Ishibe et al. 2008), further in the case of live-attenuated vaccination, the notion of employing enteric pathogens as oral vehicles appears to be highly promising in fish as well.

Inactivated or killed whole-cell oral vaccines

Inactivated vaccines or killed whole-cell vaccines is a suspension of thermally or chemically destroyed pathogens that can produce a particular protective immune response against such pathogens when administered into aquatic hosts susceptible to infectious diseases. Inactivated vaccines are used to suppress bacterial infections in fish, including those causing vibriosis and Aeromonas septicemia diseases such as V. anguillarum, V. ordalli, Y. ruckeri, V. salmonicida, and A. salmonicida (Plant and Lapatra 2011). These dead oral vaccinations are commercially available formalin-inactivated whole-cell vaccines that may be given with or without adjuvants. Although these bacterial vaccines are extremely immune-protective and inexpensive to make, the exact interaction of antigen and its component in a vaccine that stimulates the immune response along with associated factors should be analyzed well for effectiveness (Monir et al. 2021).

For example, certain analyses have proven the possible role of lipopolysaccharides in protection aiding in the vaccine’s efficacy. Some pathogenic fish viruses, such as infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV), infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV), viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV), and spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV), have inactivated vaccinations (Liu et al. 2021). Inactivation can be done with various physical and chemical agents; for example, when inoculated at high concentrations with formalin-inactivated IHNV, rainbow trout were shown to be protected against deadly IHNV (Salgado-Miranda et al. 2013). Inactivated vaccines, in contrast, to live vaccines, are more stable in the protection of aquaculture and may be less expensive to produce. Since inactivated vaccines do not survive in the environment or in vaccinated fish, they are generally considered safe; nevertheless, they exhibit shorter-lived immunity when compared to other vaccination types in the absence of boosters. Inactivated vaccines show a low immunogenicity due to the insufficient activation of cellular immunity within the fish species, demanding the use of adjuvants or several booster injections to generate protective immunity (Munang’andu and Evensen 2019). When phagocytic antigen-presenting cells (APCs) are supplied with antigens, they begin the process of eliminating it with activated immune cells and evoke a humoral immune response with effective memory to overcome if the disease recurs. Most common inactivated vaccine in use is the lethal vaccination of spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV) that consists of two inactivated SVCV strains emulsified in oil (Kibenge et al. 2012). Most early vaccination experiments in aquaculture relied on killed inactivated vaccines. Duff studied oral vaccination of cutthroat trout Oncorhynchus clarkii with a dead Aeromonas salmonicida vaccine, which was the first known use of a fish vaccine. Following that various killed vaccines were experimented within different aquatic species such as for vibriosis in trout, Atlantic salmon, Koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), Streptococcus spp., and Lactococcus spp. infections (Ma et al. 2019).

Inactivated oral vaccines, which are frequently killed bacterial strains, may provide manufacturers with a cost-effective alternative to commercial vaccinations, and these vaccines may be tailored to specific diseases that are harmful to a particular operation. These vaccines may provide a responsive treatment to emerging diseases when commercial vaccinations may be ineffective. The importance of the route of delivery of an inactivated vaccination may be observed in an investigation in which a formalin-inactivated Edwardsiella ictaluri vaccine previously utilized in aquaculture was found to have a restricted capacity to penetrate the fish. Such difficulties could be overcome by designing effective oral delivery methods in economically important fishes to obtain the complete significance of the vaccination (Zeng et al. 2021).

Modern oral vaccines

Modern oral vaccination technologies in aquaculture utilize recombinant DNA technology (rDNA) technology-based recombinant DNA vaccines, recombinant protein vaccines, and peptide vaccines. The discovery of the immunogenic component or protein from the pathogen of interest, as well as the validation of its pathogenicity in vivo and in vitro, is the step in the production of a recombinant protein vaccine (Kurath 2008). Purified glycoproteins from IHNV and VHSV, for example, have been utilized as subunit vaccines in fish and proved to be immune-protective, and so recombinant vaccines are frequently employed in aquaculture (Zhao et al. 2019; Malick et al. 2020). Once the microbial immunogenic proteins or subunits have been determined, the gene(s) responsible for their production can be inserted into a vector and overexpressed in expression systems and utilized as recombinant protein vaccinations. Peptide vaccines are made up of synthetic peptides that, when administered to the host, can trigger a protective immune response. By developing methodologies that are easily adaptable to a variety of farmed species, the synthetic peptides promise to aid future oral vaccine formulation.

Furthermore, peptide-based vaccinations are safer than traditional techniques, and the fish have less adverse effects. Because the modified (synthetic, recombinant, and/or highly purified) antigenic components of the vaccine lack immunogenicity by themselves, and may require multiple booster immunizations to ensure long-term protective immunity, many subunit vaccines rely on effective adjuvants to elicit the appropriate immunity (Bergmann-Leitner and Leitner 2014). To create a novel multi-epitope subunit oral vaccination against infections, reverse vaccinology was also used. The European Medical Agency and other authorities approved a four-component, protein-based subunit vaccine against Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B based on this method (Ma et al. 2019). Vaccines for infectious pancreatic necrosis (IPN), infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV) proteins, and virus-like particles (VLPs) formulated with E. coli expression system are among the other recombinant vaccines utilized in aquaculture (Zhao et al. 2017). Despite the discovery of subunit recombinant vaccines, they have not been much updated and analyzed in terms of commercial aquaculture usage, due to their increased production charge and the need for adjuvants for better immune response due to the limited immunogenic specificity of the epitopes.

DNA vaccines are another important class of aquatic vaccinations, comprising the genetic components that code for the immunogenic protein that expresses under controlled promoter function. The first DNA vaccination for aquaculture was developed against infectious hematopoietic necrosis (IHN) and tested in rainbow trout (Jiao et al. 2009). Experimental DNA vaccines have been produced in the last decade against several aquatic infections and for a wide range of fish species. One is an oral DNA vaccine against IHNV (Apex-IHN), which was approved for use in aquaculture, and the other is a DNA vaccine against pancreatic disease virus (salmonid alphavirus DNA vaccine/cyclonav) (Castro et al. 2014). In salmonid fish, oral DNA-based immunotherapy against infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV) has received major attention. It aimed in preventing the harsh gastrointestinal symptoms against the antigen associated with oral treatment by designing, a vector containing the capsid VP2 gene that was encased in alginate microspheres. Since DNA vaccines only express antigenic protein fragments rather than the whole organism, they are regarded as safer than attenuated live vaccines, being analyzed with their interactions with the host immune system (Munang’andu et al. 2013).

Encapsulated oral vaccines—a protective approach

When compared to alternative vaccination techniques, oral vaccine distribution offers benefits in terms of time, labor, simplicity, and reduced prices, since it eliminates any operational pressure and is not restricted by the size of the fish. However, soluble or crude antigenic formulations will elicit inadequate immune responses because they are easily destroyed in the digestive system by stomach acid and different proteolytic enzymes. As a result, different effective delivery techniques have been investigated in order to preserve the integrity of the antigen before it reaches the target immunological site. Such delivery systems follow the encapsulation technique wherein the antigenic compound is encapsulated in a carrier that can protect it from adverse gastric conditions of the fish (Mutoloki et al. 2015). The significance of encapsulation techniques where the antigen formulation is encapsulated with feeds is easier in administration and accompanies the oral route of feed uptake. There are essentially three techniques for developing vaccines through encapsulation methods such as employing adhesives such as edible oil or gelatin to top-dress formulated feed with vaccine powder, spraying formulated feed with liquid suspension vaccine, and co-processing the antigen with the feed during the manufacturing process (Assefa and Abunna 2018). But these processes possess the disadvantage of uneven distribution in the feed and the risk of antigen degradation due to direct exposure to an adverse digestive environment during feeding (Ellis 1999). Encapsulation techniques were modified with better strategies for better immune protection and response such as encapsulation in alginate beads, chitosan, Poly D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) (Lavelle et al. 1997), liposomes mediated and bio-encapsulated vaccines that have shown promising immunological responses. Furthermore, the medium for antigenic administration can increase medication release time and therapeutic effectiveness (Kole et al. 2019).

Nanomaterial encapsulated oral vaccines

The process of generating drug-loaded particles with sizes ranging from 1 to 100 nm is known as nano-encapsulation. Because of their small size, nano-scale devices may easily interact with biomolecules such as enzymes and receptors both on the surface and within cells. The antigen is encapsulated in the biodegradable coating which is basically a polymer nanomaterial so that it sustains the right epitope until it reaches the immunological site, where the antigenic material is released considerably improving the immune response. Chitosan and PLGA are two commonly used polymers for vaccine delivery in aquaculture (Kole et al. 2019).

Chitosan

Chitin is a biopolymer generated from the shells of crustaceans, insects, and some microorganisms that are biodegradable, biocompatible, and non-toxic. Through enzymatic and chemical treatments, it can be transformed to a linear polysaccharide molecule comprising β-(1–4)-linked d-glucosamine and N-acetyl-d-glucosamine produced from the N-deacetylated derivative of chitin that is known as chitosan (Sinha et al. 2004). Chitosan has been widely employed in targeted drug and DNA vaccine delivery systems in recent years due to its non-toxicity, biodegradability, muco-adhesive characteristic, biocompatibility, and penetration-promoting ability (Polk et al. 1994). A recent study on the use of a chitosan-PLGA complex as an encapsulation material for fish mucosal vaccination against viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) in Olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) has garnered attention because it helped to exploit the muco-adhesive property of the nanoparticle complex, allowing for effective vaccine administration via skin and gills hindering antigen leakage (Kim et al. 2009). Zaharoff demonstrated that chitosan nanoparticles may effectively transport encapsulated antigens to activate immunological defense system comprising macrophages and dendritic cells. Such particles were also capable to activate and enhance cellular and humoral mediated defense without the aid of adjuvants (Sahdev et al. 2014). An antigen against Vibrio anguillarum encapsulated in carbon chitosan for release in the gastrointestinal tract of turbot was described, with excellent pH responsiveness and stability, therefore shielding the antigen from destruction by stomach acid before releasing the antigen in the intestine (Table 3) (Yaacob 2017). Similarly, the DNA encoding the 38 kDa protein of Vibrio anguillarum exterior cell membrane (OMP38) was encapsulated in chitosan and fed to Asian sea bass (Lates calcarifer). It elicited a substantial antibody immunological response and provided modest levels of protection against experimental challenge (Rajesh Kumar et al. 2008).

Table 3.

Encapsulated oral vaccine development trials in aquaculture

| Pathogen | Fish species | Antigen | Protection | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vibrio anguillarum | Ayu | Inactivated bacterin bio-encapsulated in Artemia nauplii | 92.4% | Joosten and Sorgeloos (1995) |

| Vibrio harveyi | Rainbow trout | Alginate-coated outer membrane protein | 90% | Arijo et al. (2008) |

| Edwardsiella tarda, Vibrio harveyi | Turbot | Alginate coated Live-attenuated bacterin | 91% | Arijo et al. (2008) |

| Flavobacterium columnare | Nile tilapia | Alginate coated Inactivated bacterin | No protection | Leal et al. (2010) |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | Indian major carp | Chitosan coated Heat-inactivated bacterin | 20% | Leal et al. (2010) |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus | Black sea bream | Chitosan-coated bacterin | 80% | Vijayakumar et al. (2016) |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | Common carp | Liposome coated bacterin | 80% | Yadav et al. (2021) |

| Piscirickettsia salmonis | Atlantic salmon | MicroMatrix-coated bacterin | 80% | Tobar et al. (2011) |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Channel catfish | PLGA coated | 75% | Wang et al. (2011) |

| Lactococcus garvieae | Rainbow trout | PLGA and alginate coated | 76% 72% | D Bi (2010) |

PLGA

Poly D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) is a biodegradable polymer that has been widely studied as a drug delivery carrier in mammalian biology. PLGA is a copolymer produced by the bonding of two monomers, lactic acid and glycolic acid. The monomer ratio utilized during the polymerization process determines the PLGA forms. Owing to its properties such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, and high stability in biological fluids and as an adjuvant for oral vaccines, PLGA has demonstrated remarkable immune response augmentation in several circumstances and has received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval (Adomako et al. 2012). The double emulsion approach, which is based on the dissolving of a sufficient quantity of polymer (PLGA) in an organic solvent (oil phase) such as dichloromethane, chloroform, or ethyl acetate, is the most often used PLGA-NPs carrier design in fish. The encapsulation efficiency in PLGA-NPs was studied in L. rohita where it was higher owing to its increased hydrophilic nature than the immunological effect of antigen alone (Zhang et al. 2016). PLGA nanoparticles were used to deliver DNA vaccination against infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV) (Ballesteros et al. 2015), which were then combined with rainbow trout feed pellets. The vaccine reached the gut after 6 weeks of feeding to generate low levels of gene expression and specific antibody production, but this was insufficient to protect the fish against deadly assaults. To overcome this challenge and design long-term immunizing carriers, various investigations on novel polymeric formulations are carried out.

Alginate encapsulated oral vaccines

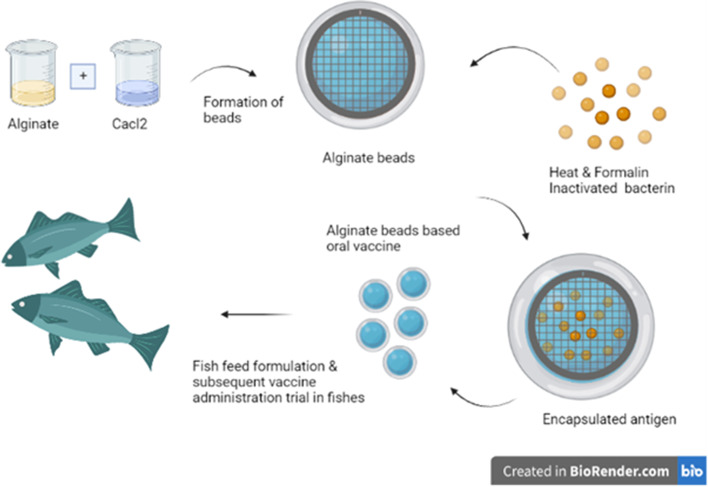

An attractive polymer for encapsulating oral vaccine formulations in aquaculture is alginate due to its strong muco-adhesive property allowing adhesion to epithelial tissues, low cost production, and bioavailability. Brown algae such as Laminaria hyperborea, Macrocystis pyrifera, Laminaria digitata, and Lessonia nigrescens are the natural source of alginate. Several bacteria, including Azotobacter vinelandii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, also possess alginate in the form of polysaccharides (Ji et al. 2015). Alginate is a complex compound composed of unbranched polyanionic polysaccharides α-l-guluronic acid (G) and β-d-mannuronic acid (M). At neutral and basic pH, alginate-microparticles disintegrate, allowing the cargo antigen to be released via diffusion; however, at low pH levels, they are exceedingly stable. Because alginate MPs are stable at low pH, they are excellent for oral delivery, owing to the characteristics of modest release of antigen in the fish stomach (pH 2–4) and increased release in the foregut or hindgut at neutral-basic pH (pH 7–8.3) (Tønnesen and Karlsen 2002). A combination of formalin-inactivated vaccines encapsulated in alginate microparticles offers a long-lasting protection in aquaculture. One such report in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), where oral administration of alginate-formalin killed antigen from Lactococcus garvieae offered excellent levels of protection against L. garvieae infection, together with a booster dosage in the interval of immunization (D Bi 2010). In another study, oral treatment of alginate MPs carrying a DNA vaccine in the form of a plasmid coding for the main capsid protein (MCP) of lymphocystis disease virus (LCDV) boosted the titer of specific antibodies against LCDV in olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) serum (Tian et al. 2008). Such novel alginate encapsulations are comparable to commercial oral aquatic vaccines in terms of their immunization efficiency (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Alginate encapsulated inactivated oral vaccine in fishes

Liposomes encapsulated oral vaccines

Liposomes are spherical, closed entities made up of phospholipid bilayers that enclose a portion of the surrounding solvent and thereby hold a self-sealing property that can inoculate both hydrophilic and lipophilic compounds. Liposomal vaccine delivery is largely attributable to various factors such as charge, nature of antigen, size, and lipid composition. Liposome-mediated vaccine formulations can be designed in terms of both nano-liposomes and micro-liposomes based on the size of the antigen and target (Ji et al. 2015). A study in the economically significant freshwater fish common carp (Cyprinus carpio) looked at the oral delivery of liposomes carrying Aeromonas salmonicida antigen. Carp inoculated with A. salmonicida antigen-containing liposomes showed a relative percentage survival of 83 percent, whereas non-immunized carp showed 66 percent survival (Irie et al. 2005). Another similar work utilized Aeromonas hydrophila antigen encapsulated liposome-mediated oral vaccination, where the serum titer raised by 2 and 3 weeks after vaccination and the vaccine exhibited protection following a live A. hydrophila challenge 22 days post immunization. Humoral immunological responses in carp were also studied after oral administration of liposome-entrapped bovine serum albumin (BSA). The nature of BSA-encapsulated liposomes was stable in bile and generated strong anti-BSA antibody responses in the serum, intestinal mucus, and bile on analysis. BSA-specific antibody secreting lymphocytes were also found in the vaccinated group. In contrast, when fishes were orally vaccinated with BSA-containing unstable liposomes or BSA alone, no serum antibody responses were found. This confers the significance of liposome encapsulated oral vaccines that should be commercialized in the aquaculture sector (Irie et al. 2003).

Bio-encapsulated oral vaccines in aquaculture

Over different encapsulation techniques in aquaculture vaccination, another strategy is the vaccine administration through bio-encapsulation of live feeds such as artemia, daphnia, and rotifers. Artemia was first reported in the mid-1700s by Schlosser, and it acquired popularity as a fish feed especially for fish larvae. The nauplii of the brine shrimp Artemia are the most extensively utilized live feed in the larviculture of fish. Indeed, the crustacean, Artemia salina, possesses specific characteristics to generate dormant embryos, generally termed “cysts,” that account its popularity as a convenient, appropriate, or excellent larval feed supply. The nutritional quality of Artemia may be further designed to provide adequate requirements for the fish larvae by bio-encapsulating appropriate quantities of particulate or emulsified compounds rich in highly unsaturated fatty acids from brine shrimp meta-nauplii stage (Van Stappen 1996). This method of bio-encapsulation, also known as Artemia enrichment, has a significant impact in fish larviculture production, in terms of their survival, growth, and metamorphosis success of many species of fish and crustaceans, along with the quality, reduced diseases, improved health, and stress resistance of fishes. Artemia naturally intakes the bacteria in which they are present encapsulating them efficiently, and this characteristic is used in artemia-enriched vaccine production and administration directly to fish (Rombout et al. 2014).

This method has been tested in the oral vaccination of fish against a variety of microorganisms, including V. anguillarum, and also in combination with advanced recombinant E. coli. Early-stage bio-encapsulated vaccine administration has caused immunosuppression in early-stage fishes in some cases which also showed an improved immune response in almost 50 to 58th-day fishes (Bergh et al. 2001).

One such work was carried out in 1997, where they used bio-encapsulation methods for protecting antigens from digestive breakdown. That method involves encapsulating antigen in live feed artemia and feeding it to juvenile carp and seabream. Oral immunization of carp at 2 and 4 weeks of age resulted in immunological tolerance. However, 8-week-old carp and seabream (8 and above) generated an immunological response with memory with which they inferred that oral immunization is beneficial. It also exhibits the fact that the age of fishes during vaccination is a significant factor in determining immune response (Gomez-Gil et al. 1998). Previous studies have demonstrated that Artemia urmiana nauplii may be bio-encapsulated with various beneficial bacteria in a variety of fish species. A vaccination trial in juvenile ayu through bio-encapsulation of V. anguillarum in rotifer was investigated. After 22 days of feeding with this enriched plankton, the animals were challenged with V. anguillarum, and Relative Percent Survival (RPS) was found to be 92.4% in comparison to 64.2% in the control group. A combination of liposomes and Artemia nauplii (Campbell et al. 1993) delivery system was established, which improved liposome content in Artemia nauplii which further boosted antigen delivery to juvenile fish (Soto et al. 2015). The kinetics of bacterial absorption by nauplii from brine shrimp (Artemia franciscana) was investigated when two groups of nauplii were supplemented with various bacteria. It was found that the efficacy of Artemia nauplii in bio-encapsulating bacteria is greatly influenced by the kind of bacteria utilized, the duration of exposure, and the condition (living or dead) of the bacteria, according to this study. Another study on the efficacy of Artemia bio-encapsulated oral vaccination of sea perch (Lateolabrax japonicus), against Vibrio anguillarum revealed that after a pathogenic challenge test through injection a week later, the group of Artemia nauplii carrying bio-encapsulated vaccine had the highest relative percentage survival (RPS) of all other vaccine groups, at around 73.7 percent (Yang and Cao 2008). Around that period, the uptake of antigens by Artemia salina was also studied. The presence of bacterial antigens from the bacterin in individual nauplii was analyzed using immunohistochemistry. Under the parameters employed, around 1·5–2·5 × 105 cells were bio-encapsulated into each Artemia, as determined by ELISA. After 30 min, the highest cell incorporation was seen, followed by a drop in number after 60 min (Campbell et al. 1993). Recent research has also analyzed the bio-encapsulation of a recombinant vaccine against cyprinid herpesvirus 3 (CyHV-3), the etiological agent of koi herpesvirus disease (KHVD), which causes significant economic losses in common carp across the world. The fluorescence observation revealed that Artemia and S. cerevisiae expression systems were capable of delivering intact antigen to the hindgut of carp larvae, indicating that the vector is significant for oral vaccination. On this premise, the oral vaccination generated a high level of specific anti-pORF65 antibody after three injections in a time period of 1 week. This reveals the significance of live feed bio-encapsulated oral route for administration of recombinant subunit vaccine (Jia et al. 2020).

Artemia bio-encapsulated vaccines are also effective against viral diseases in aquaculture (Fig. 3). One such efficacy trial was done against oral nervous necrosis virus (NNV) that promotes immunity in Epinephelus coioides larvae. Before infection with NNV, effective NNV vaccinations must be administered at the early larval stage. Owing to the tiny size of larvae and their susceptibility to stress, oral vaccination was considered a better method of immunization in comparison to injection or immersion. And the oral method adopted was bio-encapsulation of bacteria utilizing live Artemia where the recombinant E. coli that possesses and simultaneously expresses the NNV capsid gene was incorporated in a natural feeder diet for fish larvae, which showed complete antigen absorption and subsequent immune response (Sirirustananun et al. 2011). The protective immune response was due to the effective uptake through feed and double layer protection (the cell wall of artemia and artemia cuticle) of the antigen which protects it from the digestive enzymes and effective delivery into the hindgut. The antigen in the insoluble form was found to be more resistant to digestion, and slow release in the hindgut enables sequential uptake by mucosal macrophages provoking an immune response. With their results, efforts to encapsulate recombinant E. coli in Artemia and similarly in certain rotifers that aid in early immunization have generated encouraging results (Rombout et al. 2014).

Fig. 3.

Brine shrimp Artemia bio-encapsulated oral vaccine development and design

Zebrafish administered with a similar Artemia bio-encapsulated oral vaccination containing rPE antigen showed immunity against Pseudomonas Exotoxin (PE toxin) challenge through injection into muscles, suggesting that an oral vaccine can generate systemic immunity along with localized mucosal immunity (Rajanbabu and Chen 2011). Recently, as part of the EU (European Union) project Target Fish, a research work aimed to develop a methodology for oral immunization of fish larvae using other live prey such as copepods, rotifers, and daphnia. It is anticipated that the prey would acquire inactivated antigens in their digestive tract, with the live prey being administered to the fish larvae in the form of bio-capsules, functioning as vaccination for fish at an early stage when vaccination process is challenging (Midtlyng 2016). Furthermore, the antigen was persistent enough in the microorganism to be identified within the gut of fish larvae fed with (Green Fluorescent Protein) GFP-microorganisms. As a result, the expression of an antigen in the yeast and bacterial systems was possible for the oral vaccine development strategy. This method of GFP-tagged bio-encapsulated vaccine delivery aids in better visualization and ensures confirmation in the protection of antigens inside the live prey as well as in the fish gut environment (Midtlyng 2016). Such analytical technique also aids in the scope of utilizing artemia as a potent bio-carrier for also administering probiotics for various diseases in aquaculture. L. lactis subsp. lactis CF4MRS was shown to colonize Artemia effectively and also act as potential biocontrol/probiotic agent against Edwardsiella sp. infection (Chong et al. 2019). Various such works are aimed at using the artemia bio-encapsulation method in administering probiotics in aquaculture which showed to be a promising method.

Significance of bio-encapsulated vaccines in live feed

Fish, like other vertebrates, have a complex defense mechanism that allows their survival and integrity in hazardous environments. The immune systems are geared against foreign components that are identified as non-self, such as infectious agents and cancer cells. A wide range of therapeutic measures including chemical treatment, antibiotics, and vaccines are being formulated over years for successful aquaculture (Chong et al. 2019). A solid grasp of fish diseases and the most advantageous vaccine development is often achieved with two fields, microbiology and immunology. With the advent of molecular biology and increased awareness of protective antigens, new generations of vaccines for use in animals and humans are being developed at a rapid pace. Modern vaccination technology targets particular pathogens, and vaccines generated utilizing such techniques include subunit or recombinant DNA vaccines including new antigens manufactured using diverse expression systems (Ma et al. 2019). But implementation of such methods could be difficult, owing to the constraints of the aqueous environment and the practical application of mass vaccination due to the nature of commercial fish farming. Hence, a thorough analysis and modification of conventional oral vaccination method that is easier and cost-effective could be an effective approach in current aquaculture system (Gudding et al. 2014).

In animals, parenteral antigen administration elicits minimal mucosal effects, whereas antigen distribution onto mucosal surfaces elicits both local and systemic humoral and cell-mediated responses. The role of inducing particular immune responses at mucosal surfaces for protection against mucosal infections is widely investigated and proved to be more significant (Das and Salinas 2020). Previous research has shown that mucosal vaccines are most successful when they match the pathogen’s natural route of infection, can stick to, and traverse mucosal surfaces, and trigger adequate innate and adaptive immune responses. In terms of pathogen type, all oral vaccines authorized for use in humans and veterinary species are against mucosal pathogens that either infect the mucosal surface directly or use the mucosa as a portal of entry to develop a systemic infection (Mutoloki et al. 2015). Oral vaccinations that are effective are mostly based on live-attenuated viruses or bacteria that closely imitate the pathogen’s route of infection and elicit significant local immune responses without the need of any extra adjuvant. Antigens appear to be taken up via pinocytosis in freshwater fishes and then delivered to intraepithelial macrophages. This characteristic, together with the presence of many mucosal lymphoid cells, contributes to the activation of a mucosal immune response following oral immunization (Munang’andu et al. 2015).

As a result, when antigens are administered to the hindgut in sufficient amounts, oral immunization can produce both systemic and mucosal immune responses that add dual benefits. An earlier analysis of oral vaccination resulted in limited protection or low serum antibody levels along with the disadvantage of the necessity of large quantities of bacterin to be bio-encapsulated. It was found that low immune potential was due to the fact that most of the antigen was destroyed before reaching the hindgut, which was identified to be the most significant antigen-transporting region in the fish digestive system (Munang’andu et al. 2015). Hence, vaccines that adopt a natural route of entry into mucosa should be protected from the acidic proteolytic digestion in the foregut that will enable them to get exposed in the hindgut in sufficient concentration and will lead to a better immune response. In that aspect, the bio-encapsulation of a bacterin into live feeds appears to be a potential oral vaccination technique. Artemia bio-encapsulated antigen possesses dual protection from gut enzymes in fishes and stands unique in comparison to parenteral administered vaccines in terms of their protection and stability. The production of marine fish fry in commercial aquatic hatcheries is heavily reliant on live prey such as rotifers and artemia as feeding sources (Dadar et al. 2017; Dang et al. 2021). Optimizing the nutritional and microbiological components of live feeds can help to lower the high mortality rates of fish larvae which affect aquaculture. Live prey have been identified as one of the significant routes for harmful bacteria to enter fish larvae, which enable them to serve also as a potential vector for the administration of nutrients, antibiotics, vaccinations, and probiotics (Joosten and Sorgeloos 1995).

Challenges involved in oral bio-encapsulated vaccination

With proofs over the literature, it is obvious that oral vaccination has yet to make a major contribution to the entire vaccination firm for aquaculture. Oral vaccinations, on the other hand, have a huge potential in protecting and maintaining fish health and production. Easier administration and low-cost manufacturing methods provide a great incentive to resume and perform research on oral vaccines and production in aquaculture. Oral vaccination production also accompanies significant challenges (Dhar et al. 2014). The most significant of these challenges is the vaccine stability in the gut and the efficacy of a substantial humoral immune response in the vaccinated fish. With present methodologies, humoral immunity induction is not that much effective as injectable vaccination which accompanies stress in fishes. That should be overcome by a thorough analysis of the antigen to be utilized along with its immunostimulant characteristic prior to vaccine development.

Oral vaccination should be produced in more accessible form so as to be stable with better shelf life for rapid administration in aquaculture sites. Live feed bio-encapsulated vaccines show efficacy in freshwater and marine fishes based on their antigen uptake and even administration into larvae of fishes in most cases as described above. Complete uptake of antigen and protection inside live feed along with its proper transit into the fish hind gut should be ensured with proper analytical and visualization techniques for better protection. However, such vaccines which are easier and effectively applicable for vaccinating fishes at an early larval stage may cause oral tolerance and immunosuppression in fishes (Dhar 2013). This can be overcome by analyzing the age, gut immunity, and mucosal immune cells with their corresponding responses and thereby formulating the appropriate dosage of antigen through bio-encapsulation. Oral tolerance can be avoided through specific protection of particulate antigens, insulating vaccines, and delivering antigen in coated forms (Heurtault et al. 2010). Vaccinating fish at an early age also tends to have an unfavorable immunosuppressive effect. For each fish species, vaccine, and immunization procedure, the appropriate age for immunization must be determined for a better vaccination effect.

Advanced approaches in oral vaccine carriers

Along with these encapsulation techniques, various other carrier systems are also being successfully utilized for aquatic oral vaccination. Such carrier systems utilize bio-available microorganisms and molecules that can act as immune-stimulator and adjuvants, thereby enhancing immune efficacy by carrying the antigen molecule. Microorganisms such as yeasts and Bacillus sp. have been engineered and designed into characteristic vaccine carriers as per reports (Niazifar et al. n.d.). Yeasts are significantly used as immune adjuvants and as carrier for oral vaccinations owing to their oral efficacy while also extending the duration of protection in organisms. Yeasts have a eukaryotic expression system for foreign proteins that includes a unique transcription, translation, and modification mechanism that allows the protein to be processed and kept at its functional stability. Yeast-based vaccinations offer various benefits over conventional vaccines, including safety, ease of use, low stress, cost, labor, and time (Kang et al. 2018). More significantly, when delivered orally, the yeast cells are immune-stimulatory and can operate as immunological adjuvants. Research has revealed that oral administration of recombinant S. cerevisiae expressing VP2 protein from infectious pancreatic necrosis virus can generate a protective immune response in rainbow trout. Effective production of the VP37 protein is critical in the therapy of the shrimp white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) (Somsoros et al. 2021). Similarly, the Bacillus sp. are significant microorganisms that produce spores that are resistant to adverse gastrointestinal conditions and so can be utilized as effective oral vaccine carriers that protect the antigen. B. subtilis spores have been designed to express vaccine antigens, resulting in systemic and mucosal antibodies, and B. subtilis antigen appears to play a key role in eliciting a stableTh1/Th2 immune response. Initially, a study on the grass carp immunological responses following oral treatment of B. subtilis spores expressing Clonorchis sinensis enolase was carried out. The results demonstrated that C. sinensis enolase generated particular antibodies and immune gene expression (Jiang et al. 2017).

Apart from these certain probiotics used in aquaculture such as lactobacillus are also reported to be utilized as an effective vaccine carrier owing to their survival in the intestine and non-specific immune response-generating mechanism. Lactobacillus casei prototype vaccines against transmissible gastroenteritis virus and Lactobacillus plantarum (L. plantarum) prototype vaccines against Eimeria tenella have been reported to date successfully. The L. plantarum genetically engineered to co-express glycoprotein of SVCV and ORF81 protein of koi herpes virus was also employed as an oral vaccine for cyprinid fish against SVCV and koi herpes virus infection to elicit protective immunity (Liu et al. 2019).

In the realm of genetic engineering, plant-based expression vectors are also investigated for effective vaccine carriers in aquaculture. Transgenic plant vaccines can prevent antigen digestion in the foregut with no requirement for purified proteins, and they preserve protein function. The utilization of plant expression vectors for the production of fish vaccines facilitates non-toxic, low-cost, and mass vaccine production, compared to other vaccines, and can effectively transcribe the modified antigen thereby ensuring its antigenicity (Plant and Lapatra 2011). An Escherichia coli expression system was used to design a heat-labile enterotoxin B component (LTB) along with a viral polypeptide or green fluorescent protein in the stem of the potato. Following oral vaccination, carp displayed enhanced LTB absorption with particular immunological responses. Such novel oral vaccination strategies and their success rate unveil and attract the need of more investigations for sustainable disease prevention in aquaculture (Zhang et al. 2009).

Conclusion

Vaccination appears to be the most significant and sustainable solution for controlling and averting disease outbreaks in aquaculture. Vaccines for fish should be easier to administer, effective, powerful, and safe, with no negative consequences for humans and the surrounding environment. In comparison with other vaccination methods, oral vaccination methods impose less stress and healthy immune response stimulation, along with the easier administration in a mass aquaculture along with cost efficiency. Oral vaccination can also be used as booster vaccine along with immunostimulant adjuvants for greater efficacy. Owing to the significance of mucosal immunity in invertebrates, oral vaccine development should be focused with more interest along with recombinant vaccine production, and such vaccines can be designed to be administered in a specialized route to overcome the associated challenges. Overall, nano-encapsulation is a promising method that has the potential to significantly enhance the production of efficacious vaccinations in aquacultured fish. The study of viral vaccine delivery utilizing nanoparticles will be more significant and novel in fish vaccinology and needs more research. Live feeds such as artemia can be employed in such cases as potent biological carriers owing to their smaller size, easier cultivation as larval feed, and non-filter feeding characteristics to carry a wider range of bacterins as potent vaccines. This method aids in the complete uptake and protection of antigen as well as probiotics in the fish intestine which is a drawback for other oral means of vaccination that is susceptible to degradation. Hence, a wide variety of vaccines (live attenuated, inactivated, and recombinant) can be tested for their efficacy when administered through bio-encapsulation in live feeds which promotes immune response as par as equivalent to natural aquatic infection. Hence, this review aimed in comprising the peculiar encapsulated oral vaccination approaches in aquaculture. To precisely build encapsulation methods tailored to the fish immune system and to elucidate the conceptual basis of the fish immune system, further study is still required.

Author contribution

I would like to thank AR for participating in the data collection, interpretation, and manuscript preparation and BV and SJ for manuscript analysis and guidance in all aspects.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adomako M, St-Hilaire S, Zheng Y, et al. Oral DNA vaccination of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum), against infectious haematopoietic necrosis virus using PLGA [Poly(D, L-Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid)] nanoparticles. J Fish Dis. 2012;35:203–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2011.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahne W, Bjorklund HV, Essbauer S, et al. Spring viremia of carp (SVC) Dis Aquat Org. 2002;52:261–272. doi: 10.3354/dao052261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arijo S, Brunt J, Chabrillón M, et al. Subcellular components of Vibrio harveyi and probiotics induce immune responses in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum), against V. harveyi. J Fish Dis. 2008;31:579–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2008.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assefa A, Abunna F. Maintenance of fish health in aquaculture: review of epidemiological approaches for prevention and control of infectious disease of fish. Vet Med Int. 2018;2018:5432497. doi: 10.1155/2018/5432497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros NA, Alonso M, Saint-Jean SR, Perez-Prieto SI. An oral DNA vaccine against infectious haematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV) encapsulated in alginate microspheres induces dose-dependent immune responses and significant protection in rainbow trout (Oncorrhynchus mykiss) Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015;45:877–888. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2015.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergh O, Nilsen F, Samuelsen OB. Diseases, prophylaxis and treatment of the Atlantic halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus: a review. Dis Aquat Org. 2001;48:57–74. doi: 10.3354/dao048057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann-Leitner ES, Leitner WW. Adjuvants in the driver’s seat: how magnitude, type, fine specificity and longevity of immune responses are driven by distinct classes of immune potentiators. Vaccines (Basel) 2014;2:252–296. doi: 10.3390/vaccines2020252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi D (2010) Oral vaccination against lactococcosis in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) using sodium alginate and poly (lactide-co-glycolide) carrier. Kafkas Üniversitesi Veteriner Fakültesi Dergisi 16

- Bøgwald J, Dalmo RA (2021) Protection of teleost fish against infectious diseases through oral administration of vaccines: update 2021. Int J Mol Sci 22. 10.3390/ijms222010932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Campbell R, Adams A, Tatner MF, et al. Uptake of Vibrio anguillarum vaccine by Artemia salina as a potential oral delivery system to fish fry. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 1993;3:451–459. doi: 10.1006/fsim.1993.1044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castro R, Martínez-Alonso S, Fischer U, et al. DNA vaccination against a fish rhabdovirus promotes an early chemokine-related recruitment of B cells to the muscle. Vaccine. 2014;32:1160–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong W-W, Lim CS-Y, Lai K-S, Loh J-Y (2019) In vitro antimicrobial assessment on lactic acid bacteria isolated from common freshwater fishes. Asia Pac J Mol Biol Biotechnol 18–25. 10.35118/apjmbb.2019.027.2.03

- Colquhoun DJ, Lillehaug A. Vaccination against vibriosis. In: Gudding R, Lillehaug A, Evensen Ø, editors. Fish Vaccination. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2014. pp. 172–184. [Google Scholar]

- Companjen AR, Florack DEA, Slootweg T, et al. Improved uptake of plant-derived LTB-linked proteins in carp gut and induction of specific humoral immune responses upon infeed delivery. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2006;21:251–260. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadar M, Dhama K, Vakharia VN, et al. Advances in aquaculture vaccines against fish pathogens: global status and current trends. Rev Fish Sci Aquacult. 2017;25:184–217. doi: 10.1080/23308249.2016.1261277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dang M, Cao T, Vasquez I et al (2021) Oral immunization of larvae and juvenile of lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus) against Vibrio anguillarum does not influence systemic immunity. Vaccines (Basel) 9. 10.3390/vaccines9080819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Das PK, Salinas I. Fish nasal immunity: from mucosal vaccines to neuroimmunology. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020;104:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar AK, Manna SK, Thomas Allnutt FC. Viral Vaccines for Farmed Finfish. Virusdisease. 2014;25:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s13337-013-0186-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar AK (2013) Challenges and opportunities in developing oral vaccines against viral diseases of fish. J Marine Sci Res Dev 3. 10.4172/2155-9910.S1-003

- Elliott DG, Wiens GD, Hammell KL, Rhodes LD. Vaccination against bacterial kidney disease. In: Gudding R, Lillehaug A, Evensen Ø, editors. Fish Vaccination. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2014. pp. 255–272. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis AE. Immunity to bacteria in fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 1999;9:291–308. doi: 10.1006/fsim.1998.0192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Embregts CWE, Forlenza M. Oral vaccination of fish: lessons from humans and veterinary species. Dev Comp Immunol. 2016;64:118–137. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2016.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evensen O. Development in fish vaccinology with focus on delivery methodologies, adjuvants and formulations. Options Mediterraneennes. 2009;86:177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gil B, Tron-Mayén L, Roque A, et al. Species of Vibrio isolated from hepatopancreas, haemolymph and digestive tract of a population of healthy juvenile Penaeus vannamei. Aquaculture. 1998;163:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(98)00162-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gudding R, Lillehaug A, Evensen Ø, editors. Fish vaccination. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harikrishnan R, Balasundaram C, Heo M-S. Impact of plant products on innate and adaptive immune system of cultured finfish and shellfish. Aquaculture. 2011;317:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2011.03.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heurtault B, Frisch B, Pons F. Liposomes as delivery systems for nasal vaccination: strategies and outcomes. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2010;7:829–844. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2010.488687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Ma Y, Wang Y et al (2021) Oral probiotic vaccine expressing koi herpesvirus (KHV) ORF81 protein delivered by chitosan-alginate capsules is a promising strategy for mass oral vaccination of carps against KHV infection. J Virol 95. 10.1128/JVI.00415-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hu F, Li Y, Wang Q, et al. Carbon nanotube-based DNA vaccine against koi herpesvirus given by intramuscular injection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020;98:810–818. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JY, Kwon MG, Seo JS, et al. Current use and management of commercial fish vaccines in Korea. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020;102:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie T, Watarai S, Iwasaki T, Kodama H. Protection against experimental Aeromonas salmonicida infection in carp by oral immunisation with bacterial antigen entrapped liposomes. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2005;18:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie T, Watarai S, Kodama H. Humoral immune response of carp (Cyprinus carpio) induced by oral immunization with liposome-entrapped antigen. Dev Comp Immunol. 2003;27:413–421. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(02)00137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibe K, Osatomi K, Hara K, et al. Comparison of the responses of peritoneal macrophages from Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) against high virulent and low virulent strains of Edwardsiella tarda. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2008;24:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J, Torrealba D, Ruyra À, Roher N. Nanodelivery systems as new tools for immunostimulant or vaccine administration: targeting the fish immune system. Biology (Basel) 2015;4:664–696. doi: 10.3390/biology4040664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Chen T, Sun H, et al. Immune response induced by oral delivery of Bacillus subtilis spores expressing enolase of Clonorchis sinensis in grass carps (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017;60:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao X, Zhang M, Hu Y, Sun L. Construction and evaluation of DNA vaccines encoding Edwardsiella tarda antigens. Vaccine. 2009;27:5195–5202. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y-J, Guo Z-R, Ma R, et al. Immune efficacy of carbon nanotubes recombinant subunit vaccine against largemouth bass ulcerative syndrome virus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020;100:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joosten PH, Sorgeloos P. Vibrio anguillarum bacterin. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 1995;5:289–299. doi: 10.1006/fsim.1995.0028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M, Feng F, Wang Y, et al. Advances in research into oral vaccines for fish. Int J Fish Aquacult. 2018;8:19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kibenge FSB, Godoy MG, Fast M, et al. Countermeasures against viral diseases of farmed fish. Antiviral Res. 2012;95:257–281. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W-S, Kim S-R, Kim D, et al. An outbreak of VHSV (viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus) infection in farmed olive flounder Paralichthys olivaceus in Korea. Aquaculture. 2009;296:165–168. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2009.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kole S, Qadiri SSN, Shin S-M, et al. Nanoencapsulation of inactivated-viral vaccine using chitosan nanoparticles: evaluation of its protective efficacy and immune modulatory effects in olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) against viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus (VHSV) infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019;91:136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurath G (2008) Biotechnology and DNA vaccines for aquatic animals. Revue scientifique et technique-Office international des épizooties 27(1):175 [PubMed]

- Lakra WS, Gopalakrishnan A (2021) Blue revolution in India: status and future perspectives. Indian J Fish 68(1):137–150. 10.21077/ijf.2021.68.1.109283-19

- Lavelle EC, Jenkins PG, Harris JE. Oral immunization of rainbow trout with antigen microencapsulated in poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) microparticles. Vaccine. 1997;15:1070–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal CAG, Carvalho-Castro GA, Sacchetin PSC, et al. Oral and parenteral vaccines against Flavobacterium columnare: evaluation of humoral immune response by ELISA and in vivo efficiency in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Aquacult Int. 2010;18:657–666. doi: 10.1007/s10499-009-9287-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little DC, Newton RW, Beveridge MCM. Aquaculture: a rapidly growing and significant source of sustainable food? Status, transitions and potential. Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75:274–286. doi: 10.1017/S0029665116000665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Cheng Y, Lu Y, et al. Bacillus subtilis spores as an adjuvant to enhance the protection efficacy of the SVCV subunit vaccine (SVCV-M protein) in German mirror carp ( Cyprirnus Carpio Songpa Linnaeus Mirror ) Aquac Res. 2021;52:4648–4660. doi: 10.1111/are.15299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Yang G, Gao X, et al. Recombinant invasive Lactobacillus plantarum expressing fibronectin binding protein A induce specific humoral immune response by stimulating differentiation of dendritic cells. Benef Microbes. 2019;10:589–604. doi: 10.3920/BM2018.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ma S, Woo NYS (2015) Vaccination of silver sea bream (Sparus sarba) against Vibrio alginolyticus: protective evaluation of different vaccinating modalities. Int J Mol Sci 17. 10.3390/ijms17010040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Locke JB, Aziz RK, Vicknair MR, et al. Streptococcus iniae M-like protein contributes to virulence in fish and is a target for live attenuated vaccine development. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malick RC, Bera AK, Chowdhury H, et al. Identification and pathogenicity study of emerging fish pathogens Acinetobacter junii and Acinetobacter pittii recovered from a disease outbreak in Labeo catla (Hamilton, 1822) and Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (Valenciennes, 1844) of freshwater wetland in West Bengal, India. Aquac Res. 2020;51:2410–2420. doi: 10.1111/are.14584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Bruce TJ, Jones EM, Cain KD (2019) A review of fish vaccine development strategies: conventional methods and modern biotechnological approaches. Microorganisms 7. 10.3390/microorganisms7110569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Meeusen ENT, Walker J, Peters A, et al. Current status of veterinary vaccines. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:489–510. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00005-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midtlyng PJ. Methods for measuring efficacy, safety and potency of fish vaccines. In: Adams A, editor. fish vaccines. Basel: Springer; 2016. pp. 119–141. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad A, Zamri-Saad M, Amal MNA et al (2021) Vaccine efficacy of a newly developed feed-based whole-cell polyvalent vaccine against vibriosis, streptococcosis and motile aeromonad septicemia in asian seabass Lates Calcarifer. Vaccines (Basel) 9. 10.3390/vaccines9040368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Monir MS, Yusoff MSM, Zulperi ZM, et al. Immuno-protective efficiency of feed-based whole-cell inactivated bivalent vaccine against Streptococcus and Aeromonas infections in red hybrid tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus × Oreochromis mossambicus) Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2021;113:162–175. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2021.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muktar Y, Tesfaye S (2016) Present status and future prospects of fish vaccination: a review. J Veterinar Sci Technol 07. 10.4172/2157-7579.1000299

- Munang’andu HM, Evensen Ø. Correlates of protective immunity for fish vaccines. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019;85:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munang’andu HM, Fredriksen BN, Mutoloki S, et al. Antigen dose and humoral immune response correspond with protection for inactivated infectious pancreatic necrosis virus vaccines in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L) Vet Res. 2013;44:7. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-44-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munang’andu HM, Mutoloki S, Evensen Ø. An overview of challenges limiting the design of protective mucosal vaccines for finfish. Front Immunol. 2015;6:542. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutoloki S, Munang’andu HM, Evensen Ø. Oral vaccination of fish - antigen preparations, uptake, and immune induction. Front Immunol. 2015;6:519. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niazifar M, Taghizadeh A, Palangi V (2022) The role of nano-vaccines in animal science and health. NanoEra 2:14–18

- Nishizawa T, Takami I, Yang M, Oh M-J. Live vaccine of viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) for Japanese flounder at fish rearing temperature of 21°C instead of Poly(I:C) administration. Vaccine. 2011;29:8397–8404. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra D, Korytář T, Takizawa F, Sunyer JO. B cells and their role in the teleost gut. Dev Comp Immunol. 2016;64:150–166. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piganelli JD, Zhang JA, Christensen JM, Kaattari SL. Enteric coated microspheres as an oral method for antigen delivery to salmonids. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 1994;4:179–188. doi: 10.1006/fsim.1994.1017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plant KP, Lapatra SE. Advances in fish vaccine delivery. Dev Comp Immunol. 2011;35:1256–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polk AE, Amsden B, Scarratt DJ, et al. Oral delivery in aquaculture: controlled release of proteins from chitosan-alginate microcapsules. Aquacult Eng. 1994;13:311–323. doi: 10.1016/0144-8609(94)90018-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pridgeon JW, Klesius PH. Molecular identification and virulence of three Aeromonas hydrophila isolates cultured from infected channel catfish during a disease outbreak in west Alabama (USA) in 2009. Dis Aquat Org. 2011;94:249–253. doi: 10.3354/dao02332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajanbabu V, Chen J-Y. Applications of antimicrobial peptides from fish and perspectives for the future. Peptides. 2011;32:415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajesh Kumar S, Ishaq Ahmed VP, Parameswaran V, et al. Potential use of chitosan nanoparticles for oral delivery of DNA vaccine in Asian sea bass (Lates calcarifer) to protect from Vibrio (Listonella) anguillarum. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2008;25:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romalde JL, Luzardo-Alvárez A, Ravelo C, et al. Oral immunization using alginate microparticles as a useful strategy for booster vaccination against fish lactoccocosis. Aquaculture. 2004;236:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.02.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rombout JHWM, Yang G, Kiron V. Adaptive immune responses at mucosal surfaces of teleost fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014;40:634–643. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahdev P, Ochyl LJ, Moon JJ. Biomaterials for nanoparticle vaccine delivery systems. Pharm Res. 2014;31:2563–2582. doi: 10.1007/s11095-014-1419-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]