Abstract

Trauma- (and violence-) informed care (T(V)IC) has emerged as an important practice approach across a spectrum of care settings; however how to measure its implementation and impact has not been well-examined. The purpose of this scoping review is to describe the nature and extent of available measures of T(V)IC, including the cross-cutting concepts of vicarious trauma and implicit bias. Using multiple search strategies, including searches conducted by a professional librarian from database inception to Summer 2020, 1074 articles were retrieved and independently screened for eligibility by two team members. A total of 228 were reviewed in full text, yielding 13 measures that met pre-defined inclusion criteria: 1) full-text available in English; 2) describes the initial development and validation of a measure, that 3) is intended to be used to evaluate T(V)IC. A related review of vicarious trauma measures yielded two that are predominant in this literature. Among the 13 measures identified, there was significant diversity in what aspects of T(V)IC are assessed, with a clear emphasis on “knowledge” and “safety”, and less on “collaboration/choice” and “strengths-based” concepts. The items and measures are roughly split in terms of assessing individual-level knowledge, attitudes and practices, and organizational policies and protocols. Few measures examine structural factors, including racism, misogyny, poverty and other inequities, and their impact on people’s lives. We conclude that existing measures do not generally cover the full potential range of the T(V)IC, and that those seeking such a measure would need to adapt and/or combine two or more existing tools.

Keywords: vicarious trauma, violence exposure, intergenerational transmission of trauma, mental health and violence

Trauma is both the experience of, and a person’s response to, an overwhelmingly negative event or series of events (van der Kolk et al., 1996). Trauma exposure is widespread, and the impacts can be (though are not always) severe and long-term. Based on survey data from 24 countries, Benjet et al. (2016) found that 70.4% of respondents in 24 countries overall, and 82.7% of those in the United States, had experienced at least one type of traumatic event; in Canada, the prevalence is approximately 76% of adults (Van Ameringen et al., 2008). Exposure to traumatic events may cause post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but also a range of other negative mental and physical health outcomes, impacts on daily living and coping, cognitive processes, and even neurobiological changes (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014). The types of experiences that may be traumatic include, but are not limited to, accidents and injuries (e.g., natural disasters, car accidents), interpersonal violence (e.g., intimate partner violence, child maltreatment), collective violence (e.g., war, genocide, and the ongoing effects of colonialism), and others such as the death of a loved one (Benjet et al., 2016). Overall, trauma is a serious threat to individual health and well-being worldwide, and significant efforts are expended to understand, prevent, and address the problem (SAMHSA, 2014). One such effort—trauma- (and violence-) informed care (T(V)IC)—is discussed in this article.

How services are provided can have important impacts on health and well-being (Lee & Lin, 2010; Rathert et al., 2013). When serving survivors of trauma and violence, a lack of understanding of the complex and lasting impacts of these experiences may lead to harm and to missed opportunities to provide effective care. In response to this growing awareness, the last two decades have seen increased attention to “trauma-informed care/practice” (TIC/P) to help services attend to the effects of trauma, and its links to health and behavior, so as to create safe spaces that limit the potential for further harm (Covington, 2008; Elliot et al., 2005; Hopper et al., 2010; Strand et al., 2016). Trauma- and violence-informed care (TVIC) expands on TIC/P to account for the intersecting impacts of systemic and interpersonal violence and structural inequities on a person’s life, emphasizing both historical and ongoing violence and their traumatic impacts. TVIC focuses on a person’s experiences of past and current violence to situate problems as residing in both their psychological state and their social circumstances (Ponic et al., 2016; Purkey et al., 2020). There is emerging evidence that educating health and social services providers about TVIC can lead to practice change (Wathen et al., 2021). Both approaches are differentiated from trauma-specific services, which focus on the treatment of trauma symptoms.

Because T(V)IC frames and orients the provision of an organization’s primary services, assessing “success” can prove challenging. An existing gap in the literature is how best to measure the provision and impact of T(V)IC in various service contexts, at both the individual (i.e., how do providers shift their practice? what impact does this have on client/patient outcomes?) and organizational (i.e., how do organizations embed T[V]IC in their protocols and policies? how do staff and clients/patients experience these changes?) levels. The present scoping review sought to address this gap by examining existing measures and mapping them onto a specific definition of T(V)IC based on four intersecting principles of TVIC (Ponic et al., 2016; Wathen & Varcoe, 2019) with additional attention to cross-cutting concepts of vicarious trauma ([VT] including secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue) and implicit bias. Taking stock of measures in this way is a necessary step to directing future development of measurement approaches and facilitating research to identify how to effectively implement TVIC.

Principles of T(V)IC

As the TVIC concept has evolved, key authors in the field, building on previous work (e.g., Elliot et al., 2005), have articulated four integrated principles of TVIC (Ponic et al., 2016; Wathen & Varcoe, 2019):

understand structural and interpersonal experiences of trauma and violence and their impacts on peoples’ lives and behaviors;

create emotionally, culturally, and physically safe spaces for service users and providers;

foster opportunities for choice, collaboration, and connection; and

provide strengths-based and capacity-building ways to support service users.

TVIC is considered a universal approach to care, that is, the prevalence of multiple forms of trauma and violence, including interpersonal violence (e.g., child maltreatment, intimate partner violence) and structural violence (e.g., racism, poverty), means providers must assume that any person seeking service may have experienced one or more forms of trauma and violence and approach them being mindful of that potential history or ongoing experience. Understanding that these experiences may foster reactions such as distrust, disengagement, and agitation, be linked to behaviors such as substance use, and result in health problems such as chronic pain and sleeplessness, helps providers to anticipate and understand what they might see in a service interaction, classroom, or other setting.

TVIC also attends closely to the well-being of those providing care, with a focus on VT/secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue. We therefore conducted a subreview of measurement approaches in this realm to understand how existing measures fit with our operationalization of TVIC. Finally, as the concept of TVIC continues to evolve, we must examine the issue of implicit biases: unconscious stereotypes, assumptions, and associations that people may not be aware they hold and can be present even among those who are educated otherwise. These biases have been shown to be present, and highly detrimental, in health and social services, and are a significant barrier to equity-oriented, structurally competent care (Sukhera & Watling, 2018).

The TVIC principles above align in some respects with approaches to defining TIC/P, such as those of Elliot et al. (2005) and Bowen and Murshid (2016), including common elements such as choice, safety, trust, and collaboration. However, our articulation operationalizes TVIC from a more structural perspective. The provider–client interaction is emphasized as a site for validating the person’s experiences of harm from both intra- and interpersonal experiences of trauma and violence and from the ongoing conditions of their lives, especially stigma, lack of access to social determinants of health, racism, and discrimination based on gender, sexuality, ability, and so on. Importantly, TVIC emphasizes the organizational policies required to support this work. Our preliminary scan of T(V)IC measures indicated variability in how well they assessed the spectrum of knowledge, attitudes, and practices underpinning the four principles. As an additional part of the present analysis, we therefore mapped all items from included measures to the four principles and determined whether implicit bias was addressed.

To address these interrelated issues, we conducted a scoping review (Daudt et al., 2013; Peters et al., 2015) with the following research questions: (1) What validated measures exist to assess T(V)IC, including VT (Stages 1 and 2, see Method section)? (2) How are the principles of TVIC, and implicit bias, represented in existing measures (Stage 3)? and (3) What gaps exist in how TVIC is measured (Stages 1–3)?

Method

Because T(V)IC and VT are represented by distinct literatures, we used different strategies to identify and examine measures for each. These are described below in Stages 1 and 2. In Stage 3, the measures from Stage 1 were mapped onto the four T(V)IC principles and the additional element of implicit bias.

Stage 1: T(V)IC Measures

Search strategies

Four searches conducted in June and July of 2020 identified T(V)IC measures in Stage 1. First, a professional librarian searched, from inception date, the following databases: ERIC, Medline, Sociological Abstracts, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Embase. Search terms for the T(V)IC concept were focused and included the text words “trauma” and “violence” combined through proximity operators with “informed,” “based,” “sensitive,” and variations of “competence.” Additionally, the term “universal trauma precaution” was included. Search terms for the measures concept included variations of “tool,” “instrument,” “questionnaire,” “list,” “checklist,” “screen,” “scale,” “index,” “assessment,” among others, in both text words and controlled vocabulary. They were then combined with terms for measurement properties and instrument validation based on Terwee and colleagues (2009); the text words for these concepts were combined through proximity operators and the controlled vocabulary terms combined with “AND” (sample strategy available on request). Second, gray literature was sought using Google’s Advanced Search function with the term “trauma-informed” and results limited to English language and PDF format. Third, one team member conducted forward citation chaining using our database of commonly cited and foundational TVIC articles and added unique articles to the results to be screened. Finally, forward and backward citation chaining was conducted on the primary measure articles from the three prior strategies.

Screening and eligibility

References identified through database searching were imported into the online review management software Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016). Two team members independently screened titles and abstracts. The same two team members completed independent full-text screening. Decisions were compared and discussed, and the third team member was consulted to resolve disagreements in both of the above steps. References identified through all other means were put forward to double, independent full-text screening and then followed the screening process outlined above.

Eligible items were published, peer-reviewed journal articles or gray literature reports produced by national or province-/state-level government organizations, or national/supranational nongovernment organizations. These reports needed to provide some indication of peer review (e.g., use of a committee or expert panel). The following questions were used to assess eligibility: (1) Is the full-text available in English? (2) Does the source describe the initial development and validation of a measure? and (3) Is the measure intended to be used to evaluate TIC or TVIC at any stage of the research process? (including implementation research; e.g., provider needs, beliefs, knowledge, impacts). To maximize the number of measures that were included in the review while maintaining rigor, measures did not need to be formally “validated” in order to be included. However, to meet the requirements of the second eligibility question, articles needed to (a) describe the measure’s development process to some degree, (b) describe the measure in full (including overview of items, subscales, and scoring), and (c) report the measure’s psychometric properties (at least one type of reliability and one type of validity according to the Cosmin taxonomy of measurement properties; Mokkink et al., 2010). 1

Eligible measures could be intended for use in any sector or setting and with any population (i.e., organization, provider/staff, or patient/client). Sources reporting on only 2 the following were not eligible: unvalidated and “study-specific” measures (e.g., ones designed to evaluate the impact of a particular intervention); “trauma-specific” measures (e.g., ones measuring types of traumatization, PTSD, therapy impacts, or trauma skills); those measuring related but diverging constructs (e.g., patient-centered care, cultural competence); T(V)IC-related coding schemes, indicators, frameworks, or walk-throughs; and those measuring myths, perceptions, or knowledge about trauma.

Use of measures

To examine how (and how much) included measures were used in subsequent research, we conducted forward citation chaining using Google Scholar’s “cited by” function for each included primary article. The resulting references were screened by two team members. Each reference was assessed for whether it (1) collected data using the measure and reported results and (2) was available in full-text. For sources meeting these criteria, data extraction was conducted by one team member and verified by a second. The following were extracted into a shared spreadsheet: sample population, setting, whether the measure was adapted in any way, and whether new psychometric properties were reported.

Stage 2: VT Measures

VT has been of interest to researchers and clinicians for several decades, and many potential measures exist. The goal of Stage 2 was to identify and describe the most common validated measures of VT experiences and interventions and provide a general overview of their use. We conducted focused searches in June 2020 for recent review articles (2015 onward) on VT in the same six databases used for Stage 1. Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two team members and disagreements were resolved by discussion. Potentially relevant articles were examined in full text by one team member. Reviews were considered relevant for identifying measures if their full text was available in English and provided a list of research articles related to VT. If information on the measures used was not provided or unclear, the original article was examined.

The names of the measures and how many included articles used them were entered into a spreadsheet. For each, the original development/validation article(s) and any accompanying manuals were identified and used to report the measure’s characteristics. To get a sense of overall use, findings or author conclusions regarding the use and psychometric properties of the measure or related to the general state of measurement in this area were extracted.

Stage 3: Representation of TVIC Principles

To assess how comprehensively the T(V)IC construct was represented across measures, all items in those identified in Stage 1 were examined and coded as to which (if any) TVIC principle they addressed. This was done independently by two team members with consultation from the third. A coding guide including definitions of each principle (Wathen & Varcoe, 2019) was developed and each item could be coded with a single principle; coders also noted when a secondary, overlapping principle was relevant. Whether the item measured the concept at an “individual” versus “organizational” level was also coded, as were items that assessed implicit bias.

Results

Stage 1: T(V)IC Measures

Characteristics

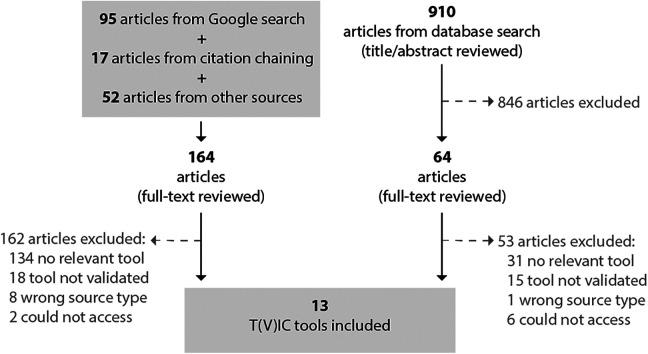

In total, the full text of 228 unique references was examined and 13 measures related to T(V)IC were included (Figure 1). Characteristics of the included measures are described in Table 1. They were published from 2008 to 2019, but most (n = 10, 77%) were published in 2016 or later. Most were described in peer-reviewed journal articles (n = 12, 92%) or reports (THRIVE, 2011) specifically focused on development and validation (n = 11, 85%). All primary articles reported validation findings derived from U.S.-based samples, and many were lacking with respect to gender and/or ethnic diversity (n = 8, 62%); about half did not report sample statistics for one or both of these factors (n = 6, 46%).

Figure 1.

Process flow diagram, Stage 1.

Table 1.

Trauma- (and Violence-) Informed Measures, Stage 1.

| Name (Author, Year) | Description | Development Process | Pilot/Initial Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARTIC scale (Baker et al., 2016) |

|

|

|

| TICOMETER (American Institutes for Research, 2016; Bassuk et al., 2017) |

|

|

|

| CPC (Clark et al., 2008) |

|

|

|

| TIP Scales (Goodman et al., 2016) |

|

|

|

| VT-ORG (Hallinan et al., 2019) |

|

|

|

| Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of TIP Survey (King et al., 2019) |

|

|

|

| TSRT (Chadwick Center for Children and Families, 2013; Lang et al., 2016)a |

|

|

|

| Child Welfare Trauma-Informed Assessment Tool (Madden et al., 2017) |

|

|

|

| TISCI (2nd ed.; (Richardson et al., 2010, 2012) |

|

|

|

| TISC-R (Salloum et al., 2015, 2018 c) |

|

|

|

| STSI-OA (Sprang et al., 2016) |

|

|

|

| Measure of foundational knowledge about TIC (Sundborg, 2019) |

|

|

|

| TIAA (THRIVE, 2011; Thrive Initiative, 2011a, 2011b, 2011c) |

|

|

|

Note. ACE = adverse childhood experiences; ARTIC = Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care; CFA = confirmatory factor analysis; CPC = consumer perceptions of care; CTISP = Chadwick Trauma-Informed Systems Project; DV = domestic violence; EBPAS = Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale; EFA = exploratory factor analysis; ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient; NCTSN = National Child Traumatic Stress Network; ROC = Receiver Operating Characteristic; STS = secondary traumatic stress; STSI-OA = Secondary Traumatic Stress–Informed Organizational Assessment; TIAA = System of Care Trauma-Informed Agency Assessment; TIC = trauma-informed care; TICS = Trauma-Informed Climate Scale; TIP = trauma-informed practice; TISC = trauma-informed self-care; TISCI = Trauma-Informed System Change Instrument; TSRT = Trauma System Readiness Tool; VT-ORG = Vicarious Trauma Organizational Readiness Guide.

a We evaluated the Lang et al. (2016) version of the scale originally developed for the CTISP. b The version we obtained from authors has 100 items. c Multiple articles report on early validation, but this has been treated as the primary one for the purposes of data extraction.

The development processes for the included measures ranged from reviewing the literature and existing measures to extensive multistage processes involving consultation with expert panels, field testing, and/or community-based participatory research (e.g., Baker et al., 2016; Sprang et al., 2016). For seven measures, theory appeared to be integrated into or foundational to development (Goodman et al., 2016; Hallinan et al., 2019; Madden et al., 2017; Richardson et al., 2012; Salloum et al., 2018; THRIVE, 2011), whereas theory was mentioned, but not integrated, or not mentioned at all for the others; details regarding the role of theory were not always clear. Similarly, some articles reported more extensive validation work than others, and a few articles explicitly noted that further validation was needed (e.g., Richardson et al., 2012; Salloum et al., 2018; THRIVE, 2011).

The individual included measures ranged in length from 10 to 100 items; some were represented by a set of submeasures. For example, the Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care (ARTIC; Baker et al., 2016) has different versions tailored for social services and education. Most measures were designed to be completed by service providers or staff (n = 10, 77%) as opposed to service users (Clark et al., 2008; Goodman et al., 2016) or both (THRIVE, 2011). Many sectors were represented including child welfare, education, law enforcement, mental health services, and health care. Some measures contained mostly or all organization-level items (n = 5, 38%) or all or mostly individual-level items (n = 6, 46%) and one measure had about half of each (Goodman et al., 2016). The System of Care Trauma-Informed Agency Assessment (THRIVE, 2011) has three versions, two with individual-level items (family and youth versions) and for staff at the organizational level (agency version).

Measures were designed to assess a variety of constructs related to T(V)IC. Two were focused on VT (Hallinan et al., 2019; Sprang et al., 2016) but were included in Stage 1 because they explicitly measured it from a trauma-informed organization perspective. Similarly, one measured trauma-informed self-care (Salloum et al., 2018). Otherwise, they were designed to measure client perceptions of care (Clark et al., 2008; Goodman et al., 2016), capacity to implement T(V)IC (Baker et al., 2016; Lang et al., 2016), T(V)IC practice (Bassuk et al., 2017; Richardson et al., 2012; THRIVE, 2011), T(V)IC knowledge only (Sundborg, 2019), and a combination of knowledge, attitudes, and/or practice (King et al., 2019; Madden et al., 2017).

Use

In total, the primary articles for the 13 included measures had been cited 348 times. Of these, 142 were ineligible because they were a book, book chapter, or thesis; a duplicate citation; not accessible; not in English; or did not actually appear to cite the primary article. The measures included in this review have been infrequently used to collect data. The most commonly used was the ARTIC (most often the ARTIC-35; Baker et al., 2016) which was used 10 times in various contexts such as education, child welfare, nursing, and human services. Of the 10 articles, half reported new psychometric properties, one developed a new version (Japanese language; Niimura et al., 2019), and two used only a subset of ARTIC items. Of the remaining measures, seven had not been used at all and five had been used one to five times (for a total of 16 uses; Clark et al., 2008; Goodman et al., 2016; Lang et al., 2016; Richardson et al., 2012; Salloum et al., 2018). Of the articles using these, eight (50%) reported new psychometrics (usually internal consistency). Most (n = 10, 77%) did not revise or adapt the measure, five (38%) slightly revised or used part(s) of it, and one article reported on a new version (Trauma System Readiness Tool-Short Form; Connell et al., 2019). Data were collected from a variety of sectors such as child welfare, domestic violence services, and mental health services. Three measures were cited in subsequent articles because they were used to inform the development of other instruments (Lang et al., 2016; Richardson et al., 2012; THRIVE, 2011).

Stage 2: VT Measures

In total, 35 unique references were screened, 27 were reviewed in full, and 14 were examined to determine the most used VT measures. Excluded reviews either were not available in English or not published in full (e.g., conference abstracts), had no articles meeting their inclusion criteria, or did not include information regarding measures (e.g., qualitative reviews). The 14 reviews reported on 324 unique sources published from 1981 to 2017 and targeted health and/or social service providers in general or those with specific occupations within these fields. Ultimately, two measures were most commonly used: the Professional Quality of Life (ProQoL-5) instrument (Stamm, 2010), including its precursors, and the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale (STSS; Bride et al., 2004; see Table 2), a finding consistent with extant literature on assessing “empathy-based strain” (Rauvola et al., 2019).

Table 2.

Vicarious Trauma Measures, Stage 2.

| Name (Author, Year) | Description | Development Process | Pilot/Initial Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProQoL 5a (Stamm, 2009, 2010) |

|

|

|

| STSS (Bride et al., 2004) |

|

|

|

Note. CFA = confirmatory factor analysis; CFST = Compassion Fatigue Self-Test; CSFT = Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue Test; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; ProQoL = Professional Quality of Life Scale; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; STSS = Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale.

a Tool details for the most recent version of the ProQoL are described in this table.

Although the ProQoL-5 (including previous versions) and STSS have undergone psychometric assessment (for an overview for the ProQoL, see Keesler & Fukui, 2020), they are not without criticism. For example, they have both been found to have varying factor structures, and problematic items and factor loadings for the ProQoL have been identified (Geoffrion et al., 2019; Rauvola et al., 2019). Further, evidence of the measures’ construct validity is lacking (Hemsworth et al., 2018; Heritage et al., 2018; Rauvola et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the ProQoL in its various forms is widely accepted as the most frequently used measure of compassion fatigue (Sinclair et al., 2017). Although we did not do a full review of their use, it should be noted that to date the primary articles for the STSS (Bride et al., 2004) and ProQoL-5 (Stamm, 2010) have been cited in Google Scholar 734 and 1,432 times, respectively. The ProQoL-5 has been translated into many languages (ProQoL.org, 2019; Stamm, 2010) and the STSS has French and Italian versions (Jacobs et al., 2019; Setti & Argentero, 2012).

Stage 3: Representation of TVIC Principles

A total of 499 items across the 13 (Stage 1) measures were coded. Descriptions for each TVIC principle code and sample items receiving that code are presented in Table 3. Table 4 presents the results of our mapping of each measure to the four TVIC principles. No items addressing implicit bias were identified, and only three measures had items related to structural issues, including social determinants of health, racism, stigma, and discrimination. Some items received no code, for example, because they measured more general aspects of care environments, aspects of trauma-focused (as opposed to informed) care, or the appropriate principle was unclear. Overall, Principles 1 and 2 were most often represented in the measures. Given the overlapping nature of the TVIC principles, it is not surprising that some items (n = 94, 18.8%) also received a secondary code. The most common secondary code was Principle 1 (n = 60, 63.8%) followed by Principles 2 (n = 14, 14.9%), 3 (n = 13, 13.8%), and 4 (n = 7, 7.4%). By far, the most common pairing was Principles 1 and 2 (n = 59, 62.8%), for example, items about policies/procedures (P1) to ensure safety (P2) such as “My performance evaluation includes a discussion of organizational and individual strategies to minimize risk for vicarious traumatization” (VT Organizational Readiness Guide; Hallinan et al., 2019) or about training (P1) related to safety (P2): for example, “Reception staff are trained to greet service users in a welcoming manner” (TICOMETER; Bassuk et al., 2017). A summary of the strengths and weaknesses of each tool is presented in Table 5.

Table 3.

TVIC Principles Code Descriptions and Sample Items, Stage 3.

| Principle and Code Description | Sample Items Receiving Code |

|---|---|

| Principle 1: Understand trauma, violence, and its impacts on

people’s lives and

behavior Knowledge/understanding/training on trauma (including vicarious), violence (including structural), and the impacts on people and their behavior? This may include knowledge about appropriate initial responses to disclosure to minimize risk of further harm, for example, as well as policies or procedures in place indicating a culture of T(V)IC or anything to do with T(V)IC training |

“Written policy is established committing to trauma informed

practices.” (Richardson et al.,

2010, 2012) “I understand how historical and structural oppression may create traumatic conditions and psychological trauma.” (Sundborg, 2019) |

| Principle 2: Create emotionally and physically safe

environments for all clients and providers Addresses safety (physical, emotional, cultural, and spiritual), or aspects of place/space that contribute to perceptions of safety. Focuses on interactions that may influence perceived safety such being nonjudgmental, avoiding “triggering,” fostering connection/trust, providing clear information or ensuring confidentiality/privacy. Measures an aspect of provider safety (e.g., self-care) |

“I felt safe and comfortable when I met with my service

providers” (Clark et al.,

2008) “Supervisors promote safety and resilience to STS by routinely attending to the risks and signs of STS” (Sprang et al., 2016) |

| Principle 3: Foster opportunities for choice, collaboration,

and connection Emphasis on shared decision making or the service user having meaningful choice in their own care or involvement in how/what services are provided. The provider/organization offers choices that are feasible for people given life circumstances (e.g., poverty). Describes collaboration or communication between providers or organizations related to client care? |

“Service users’ desires and preferences are given top

priority in the treatment or service plan” (Bassuk et

al., 2017) “I am encouraged to network and collaborate with coworkers and other organizations” (Hallinan et al., 2019) |

| Principle 4: Use a strengths-based and capacity-building

approach to support clients What the service user brings (e.g., coping strategies, knowledge or strengths), their resilience, or a capacity-building approach to services (i.e., understanding where capacities lie and helping people to develop skills). Indicates that sufficient time is allowed for meaningful engagement, providing tailored/flexible program options to meet people’s needs, strengths, or situations |

“Staff respect the strengths I have gained through my life

experiences” (Goodman et al.,

2016) “I ask the parents I work with how they cope with the difficult feelings that surround the trauma they have experienced” (Madden et al., 2017) |

| Implicit bias. Acknowledges that an individual/organization may unintentionally discriminate against, stereotype or have stigmatizing thoughts about people using services, and/or that this could influence care provision |

No examples found |

Note. TVIC = trauma- and violence-informed care; T(V)IC = trauma- (and violence-) informed care.

Table 4.

TVIC Principles in T(V)IC Measurement Items, Stage 3.

| Principle 1 | Principle 2 | Principle 3 | Principle 4 | No Principle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tool Name (Number of Items) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| ARTIC scale (45) | 14 (31.1) | 21 (46.7) | 0 (0) | 4 (8.9) | 6 (13.3) |

| TICOMETER (15 a) | 4 (26.7) | 6 (40.0) | 3 (20.0) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) |

| CPC (26) | 3 (11.5) | 10 (38.5) | 7 (26.9) | 5 (19.2) | 1 (3.8) |

| TIP Scales (20 + 13 supplemental) | 11 (33.3) | 9 (27.3) | 5 (15.2) | 7 (21.2) | 1 (3.0) |

| VT-ORG (68 b) | 8 (11.8) | 29 (42.6) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 30 (44.1) |

| Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Trauma-Informed Practice Survey (21) | 11 (52.4) | 3 (14.3) | 3 (14.3) | 3 (14.3) | 1 (4.8) |

| TSRT (100) | 31 (31.0) | 21 (21.0) | 9 (9.0) | 14 (14.0) | 25 (25.0) |

| Child Welfare Trauma-Informed Assessment Tool (11) | 6 (54.5) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) |

| TISCI (2nd ed.; 18) | 6 (33.3) | 6 (33.3) | 5 (27.8) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0) |

| TISC-R (10) | 3 (30.0) | 7 (70.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| STSI-OA (40) | 6 (15.0) | 31 (77.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.0) |

| Measure of foundational knowledge about TIC (30) | 30 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| TIAA (Agency) c (35) | 8 (22.9) | 18 (51.4) | 8 (22.9) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) |

| TIAA (Youth) c (42 plus 5 subquestions) | 2 (4.3) | 18 (38.3) | 17 (36.2) | 7 (14.9) | 3 (6.4) |

| Total (499) | 143 (28.7) | 182 (36.5) | 59 (11.8) | 45 (9.0) | 70 (14.0) |

Note. ARTIC = Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care; CPC = Consumer Perceptions of Care; CTISP = Chadwick Trauma-Informed Systems Project; DV = domestic violence; STS = secondary traumatic stress; STSI-OA = Secondary Traumatic Stress Informed Organizational Assessment; TIAA = System of Care Trauma-Informed Agency Assessment; TIC = trauma-informed care; TICS = Trauma-Informed Climate Scale; TIP = trauma-informed practice; TISC = trauma-informed self-care; TISCI = Trauma-Informed System Change Instrument; TSRT = Trauma System Readiness Tool; VT-ORG = Vicarious Trauma Organizational Readiness Guide; TVIC = trauma- and violence-informed care; T(V)IC = trauma- (and violence-) informed care.

a The TICOMETER has 35 items in total, but we were not able to access the complete tool.

b There are multiple versions of the VT-ORG; therefore, we used one and then also coded any unique items from the other versions.

c There are three versions of the TIAA, but the Youth and Family versions are almost identical; therefore, we coded the Agency and Youth versions only.

Table 5.

Summary of Strengths and Weaknesses of T(V)IC Measures.

| Name (Author, Year) | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| ARTIC scale (Baker et al., 2016) |

|

|

| TICOMETER (Bassuk et al., 2017) |

|

|

| CPC (Clark et al., 2008) |

|

|

| TIP Scales (Goodman et al., 2016) |

|

|

| VT-ORG (Hallinan et al., 2019) |

|

|

| Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Trauma-Informed Practice Survey (King et al., 2019) |

|

|

| TSRT (Chadwick Center for Children and Families, 2013; Lang et al., 2016) |

|

|

| Child Welfare Trauma-Informed Assessment Tool (Madden et al., 2017) |

|

|

| TISCI (2nd ed.) (Richardson et al., 2010, 2012) |

|

|

| TISC-R (Salloum, 2018) |

|

|

| STSI-OA (Sprang et al., 2016) |

|

|

| Measure of TIC foundational knowledge (Sundborg, 2019) |

|

|

| TIAA (THRIVE, 2011) |

|

|

Note. ARTIC = Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care; CPC = Consumer Perceptions of Care; CTISP = Chadwick Trauma-Informed Systems Project; DV = domestic violence; STS = secondary traumatic stress; STSI-OA = Secondary Traumatic Stress–Informed Organizational Assessment; TIAA = System of Care Trauma-Informed Agency Assessment; TIC = trauma-informed care; TICS = Trauma-Informed Climate Scale; TIP = trauma-informed practice; TISC = trauma-informed self-care; TISCI = Trauma-Informed System Change Instrument; TSRT = Trauma System Readiness Tool; VT-ORG = Vicarious Trauma Organizational Readiness Guide.

Discussion

This three-stage scoping review was conducted to assess the nature and extent of existing measures of TVIC. In Stage 1, we identified 13 measures used primarily to assess the original articulation of TIC/P, roughly split in terms of measurement at the individual provider/client level and organizational approaches to supporting practice. Overall, the primary aspects of T(V)IC assessed were VT or self-care from a trauma-informed perspective, client perceptions of care, capacity to implement T(V)IC, and T(V)IC knowledge, attitudes, and practice. Less attention was given to structural issues, including social determinants of health, racism, stigma, and discrimination. None of the 13 measures included items to assess implicit bias.

These measures tended to be more recent (since 2016) and therefore not (yet) well-cited, with certain exceptions (e.g., the ARTIC); many addressed T(V)IC in fairly homogenous, U.S.-based samples. About half of the measures alluded in some way to theory, though the role of theory in developing items or instruments was not always clear. A range of development and validation approaches was described. Several of the measures had multiple versions for use in different human service contexts, and overall, a wide range of practice settings, from acute and community-based health care to policing to education, were represented.

In terms of measuring VT, our focused review, consistent with existing literature, found that the ProQoL-5 instrument (Stamm, 2010), including its precursors, and the STSS (Bride et al., 2004) were most commonly used. Both are well-cited and translated into multiple languages. However, each requires additional validation and testing (Rauvola et al., 2019).

Our mapping of items from Stage 1 onto the four TVIC principles showed that these core elements are treated unequally, with most (65%) of the 499 items included in the 13 measures focusing on Principles 1 (knowledge) or 2 (safety). Only 12% focused on Principle 3 (collaboration) and 9% on Principle 4 (strengths-based); 14% of items did not map onto any of the four principles. The weighting of these principles across measures varied considerably, with some having relatively equal distribution across items, and others addressing only one principle.

One issue we noted was the conflation of “trauma-focused” (i.e., treatments for trauma) and “trauma-informed”; that is, some of the measures we examined included items we would consider “trauma-focused” rather than “trauma-informed.” This lack of conceptual clarity has been discussed in the TVIC literature more broadly and identified as a barrier to quality research (Donisch et al., 2016; Hanson & Lang, 2016; Mersky et al., 2019). The inclusion of trauma-focused items to evaluate T(V)IC in settings where trauma-specific services are not part of routine care (e.g., primary health care, policing, education) is potentially problematic, as it presents an unfair test of these services; it may also unduly emphasize seeking out disclosures rather than treating everyone as though they may have experienced trauma.

Our review was not without limitations. First, our decision to articulate TVIC according to four principles (Ponic et al., 2016; Wathen & Varcoe, 2019), rather than, for example, the 10 proposed by Elliot et al. (2005) or the seven used by Bowen and Murshid (2016) for policy contexts, means that approaches using those conceptualizations might have different findings. However, a smaller set of principles does allow for more convergence around concepts, and less atomization, which may better help us understand important gaps in measurement. In addition, while our search was systematic and comprehensive, it was not exhaustive—some measures or articles citing measures could have been missed, especially with the more focused review-based search for measures of VT. Again, however, we selected the more efficient approach to answer this more specific research question.

The most pressing need for future research is the development of a TVIC measure that “does it all.” This could take the form of adapting and testing an already near-comprehensive measure with additional questions to fill gaps, as was the approach taken by Rodger et al. (2020), who used the education version of the ARTIC but added questions to assess the more structural aspects of trauma and violence experienced by children and youth to fill those gaps in assessing TVIC education with student teachers. Alternatively, a new measure could be developed, starting with theoretical underpinnings of trauma, structural and interpersonal violence, implicit bias, VT and organizational change (among others), and using an iterative and participatory approach to collecting empirical data. Such a process should incorporate the lived/living experience of all relevant actors, including service leaders, providers, and users, with an emphasis on capturing these experiences among samples diverse across various social locations and conditions, including race, gender, sexuality, geography, income, and ability status.

Conclusion

The primary motivation in conducting this review was pragmatic, that is, to find measures that would assist in assessing interventions to implement TVIC, including a focus on both interpersonal and structural forms of violence. As evidence is generated indicating that educating professionals about TVIC (Wathen et al., 2021) and providing care in these ways (Purkey et al., 2020) can improve both provider and patient experiences and outcomes, it is important to understand how both organizations and researchers can evaluate these practices at both the individual and organizational levels. Overall, a range of high-quality measures exist, but none that completely cover the range of knowledge, attitudes, practices, and policies that reflect the structural competence required to safely recognize and respond to the historical and ongoing experiences of trauma and violence faced by most care seekers, and the intersection of various social locations on people’s experiences of receiving and providing care. Given increased attention to structural issues, from racism to poverty, and their impact on every aspect of people’s lives, it is increasingly obvious that we must not only implement interventions that approach TVIC from a structural stance, but also that we develop more nuanced and rigorous ways to assess these efforts.

Critical Findings

While a number of measures exist, there is significant diversity in what aspects of T(V)IC are assessed, with a clear emphasis on “knowledge” and “safety.”

The items and measures are roughly split with some focusing on individual-level knowledge, attitudes and practices, and others designed to assess organizational policies and protocols. Few measures examine structural factors such as poverty and racism, and none included in this review assessed implicit bias as a facet of T(V)IC.

Two VT measures dominate the assessment landscape in this area; both are well-used but each requires additional validation. Several T(V)IC measures explicitly include VT (or related concepts), but this is not uniform.

Implications for Practice, Policy, and Research

Organizations and systems implementing trauma- and violence-informed approaches to service delivery require robust ways to assess the success of these efforts, including impacts on staff and users of service.

Existing measures do not generally cover the full potential range of the core principles of what we have defined as TVIC, which takes a structural lens to both people’s past and ongoing experiences, and to the conditions of their lives.

Since no one measure assesses the core principles comprehensively, while at the same time attending at least to some extent to individual, organizational as well as structural factors, those seeking such a measure would need to adapt and/or combine two or more existing tools.

Author Biographies

C. Nadine Wathen, PhD, is a full professor and Canada Research Chair in mobilizing knowledge on gender-based violence. She works in the Arthur Labatt Family School of Nursing at Western University and is a research scholar at Western’s Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women and Children. She is a member of the College of the Royal Society of Canada. Her research examines the health and social service sector response to gender-based violence, interventions to reduce health inequities, and the science of knowledge mobilization, with a focus on partnerships to enhance the use of research in policy and practice. She has led a number of federally funded research initiatives and international research and knowledge mobilization networks.

Brenna Schmitt, HBSc, is a recent graduate of the University of Toronto, where she studied Human Biology and Health Studies. She works as a research assistant for the Arthur Labatt Family School of Nursing at Western University. She also works as a research assistant for the Mental Health Nursing Research Alliance at Lawson Health Research Institute. Her research interests include gender-based and reproductive health service disparities, food justice, and equity-oriented health policy solutions.

Jen C. D. MacGregor, PhD, is a senior research associate in the Arthur Labatt Family School of Nursing at Western University and Community Research Associate at Western’s Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women and Children. She is a member of the Domestic Violence at Work Network and was a lead researcher on the first Canadian national study on the impacts of domestic violence on the workplace. Her current projects focus on domestic violence in the Canadian media, the evaluation of trauma- and violence-informed care training initiatives, and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on domestic violence shelter services.

Notes

We considered evaluating each tool using the COSMIN (Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement INstruments) checklist. However, because articles were not required to have performed a formal validation process, we concluded it was not appropriate to hold papers to this standard.

Having items on these topics did not exclude the measure from consideration, but it could not solely measure these constructs.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded in part by Nadine Wathen’s Canada Research Chair.

ORCID iDs: C. Nadine Wathen  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2646-2919

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2646-2919

Jennifer C. D. MacGregor  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5908-9108

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5908-9108

References

- Aarons G. A. (2005). Measuring provider attitudes toward evidence-based practice: Organizational context and individual differences. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 14, 255–271. 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdoh N., Bernardi E., McCarthy A. (2017). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of trauma-informed practice: A survey of health care professionals and support staff at Alexander Street Community [Unpublished manuscript]. http://hdl.handle.net/2429/60785

- American Institutes for Research. (2016). Trauma-informed organizational capacity scale (TIC Scale): An agency-wide assessment [PDF file]. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/trauma-informed-organizational-capacity-scale.pdf

- Baker C. N., Brown S. M., Wilcox P. D., Overstreet S., Arora P. (2016). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care (ARTIC) Scale. School Mental Health, 8(1), 61–76. http://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs12310-015-9161-0 [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk E. L., Unick G. J., Paquette K., Richard M. K. (2017). Developing an instrument to measure organizational trauma-informed care in human services: The TICOMETER. Psychology of Violence, 7(1), 150–157. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/vio0000030 [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C., Bromet E., Karam E. G., Kessler R. C., McLaughlin K. A., Ruscio A., Shahly V., Stein D. J., Petukhova M., Hill E., Alonso J., Atwoli L., Bunting B., Bruffaerts R., Caldas-de-Almeida J. M., de Girolamo G., Florescu S., Gureje O., Huang Y.…Koenen K. C. (2016). The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: Results from the world mental health survey consortium. Psychological Medicine, 46(2), 327–343. http://doi.org/ 10.1017/S0033291715001981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bowen E. A., Murshid N. S. (2016). Trauma-informed social policy: A conceptual framework for policy analysis and advocacy. American Journal of Public Health, 106, 223–229. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bride B. E., Robinson M. M., Yegidis B., Figley C. R. (2004). Development and validation of the secondary traumatic stress scale. Research on Social Work Practice, 14(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1049731503254106 [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick Center for Children and Families. (2013). Trauma-informed child welfare practice toolkit. https://ctisp.wordpress.com/trauma-informed-child-welfare-practice-toolkit/

- Child Welfare Committee, National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2008). Child welfare trauma training toolkit: Comprehensive guide (2nd ed.). National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. [Google Scholar]

- Clark C., Young M. S., Jackson E., Graeber C., Mazelis R., Kammerer N., Huntington N. (2008). Consumer perceptions of integrated trauma-informed services among women with co-occurring disorders. The Journal of Behavioural Health Services & Research, 35(1), 71–90. 10.1007/s11414-007-9076-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell C. M., Lang J. M., Zorba B., Stevens K. (2019). Enhancing capacity for trauma-informed care in child welfare: Impact of a statewide systems change initiative. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(3–4), 467–480. 10.1002/ajcp.12375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington S. S. (2008). Women and addiction: A trauma-informed approach. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 40(S5), 377–385. 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daudt H. M., van Mossel C., Scott S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13, 48. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donisch K., Bray C., Gewirtz A. (2016). Child welfare, juvenile justice, mental health, and education providers’ conceptualizations of trauma-informed practice. Child Maltreatment, 21(2), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1077559516633304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot D. E., Bjelajac P., Fallot R. D., Markoff L.S., Reed B. G. (2005). Trauma-informed or trauma-denied: Principles and implementation of trauma-informed services for women. Journal of Community Psychology, 33(4), 461–477. 10.1002/jcop.20063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fallot R. D., Harris M. (2001). A trauma-informed approach to screening and assessment. New Directions for Mental Health Services, 2001(89), 23–31. 10.1002/yd.23320018904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figley C. R. (1995). Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. In Figley C. R. (Ed.), Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized (pp. 1–20). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Figley C. R., Stamm B. H. (1996). Psychometric review of compassion fatigue self test. In Stamm B. H. (Ed.), Measurement of stress, trauma, and adaptation (pp. 127–130). Sidran Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith J. R. (2002). Organizing to deliver solutions. Organizational Dynamics, 31, 194–207. [Google Scholar]

- Geoffrion S., Lamothe J., Morizot J., Giguère C.-E. (2019). Construct validity of the professional quality of life (ProQoL) Scale in a sample of child protection workers. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(4), 566–576. 10.1002/jts.22410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittell J. H. (2006). Relational coordination: Coordinating work through relationships of shared goals, shared knowledge and mutual respect. In Kyriakidou O., Ezbilgin M. (Eds.), Relational perspectives in organizational studies: A research companion (pp. 74–94). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman L. A., Sullivan C. M., Serrata J., Perilla J., Wilson J. M., Fauci J. E., DiGiovanni C. D. (2016). Development and validation of the trauma-informed practice scales. Journal of Community Psychology, 44(6), 747–764. 10.1002/jcop.21799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hallinan S., Shiyko M. P., Volpe R., Molnar B. E. (2019). Reliability and validity of the vicarious trauma organizational readiness guide (VT-ORG). American Journal of Community Psychology, 64, 481–493. 10.1002/ajcp.12395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson R. F. & Lang J. (2016). A critical look at trauma-informed care among agencies and systems serving maltreated youth and their families. Child Maltreatment, 21(2), 95–100. 10.1177/1077559516635274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsworth D., Baregheh A., Aoun S., Kazanjian A. (2018). A critical enquiry into the psychometric properties of the professional quality of life scale (ProQoL-5) instrument. Applied Nursing Research, 39, 81–88. 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks A., Conradi L., Wilson C. (2011). The trauma system readiness tool. Chadwick Center for Children and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage B., Rees C. S., Hegney D. G. (2018). The ProQOL-21: A revised version of the professional quality of life (ProQOL) scale based on Rasch analysis. PLoS One, 13(2), e0193478. 10.1371/journal.pone.0193478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper E. K., Bassuk E. L., Oliver J. (2010). Shelter from the storm: Trauma-informed care in homelessness services settings. Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 3, 80–100. 10.2174/1874924001003010080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs I., Charmillot M., Martin Soelch C., Horsch A. (2019). Validity, reliability, and factor structure of the secondary traumatic stress scale-French version. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 191. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keesler J. M., Fukui S. (2020). Factor structure of the professional quality of life scale among direct support professionals: Factorial validity and scale reliability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 64(9), 681–689. 10.1111/jir.12766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King S., Kuan-Lang D. C., Chokshi B. (2019). Becoming trauma informed: Validating a tool to assess health professional’s knowledge, attitude, and practice. Pediatric Quality and Safety, 4(5), e215. https://doi.org/10.1097%2Fpq9.0000000000000215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang J. M., Campbell K., Shanley P., Crusto C. A., Connell C. M. (2016). Building capacity for trauma-informed care in the child welfare system: Initial results of a statewide implementation. Child Maltreatment, 21(2), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1077559516635273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.-Y., Lin J. L. (2010). Do patient autonomy preferences matter? Linking patient-centered care to patient-physician relationships and health outcomes. Social Science & Medicine, 71(10), 1811–1818. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden E. E., Scannapieco M., Killian M. O., Adorno G. (2017). Exploratory factor analysis and reliability of the child welfare trauma-informed individual assessment tool. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 11(1), 58–72. 10.1080/15548732.2016.1231653 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mersky J. P., Topitzes J., Britz L. (2019). Promoting evidence-based, trauma-informed social work practice. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(4), 645–657. 10.1080/10437797.2019.1627261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mokkink L. B., Terwee C. B., Patrick D. L., Alonso J., Stratford P. W., Knol D. L., Bouter L. M., de Vet H. C. (2010). The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(7), 737–745. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2008). Essential elements of trauma-informed child welfare practice. National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. [Google Scholar]

- Niimura J., Nakanishi M., Okumura Y., Kawano M., Nishida A. (2019). Effectiveness of 1-day trauma-informed care training programme on attitudes in psychiatric hospitals: A pre-post study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28, 980–988. 10.1111/inm.12603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., Elmagarmid A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5, 210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M. D. J., Godfrey C. M., Khalil H., McInerney P., Parker D., Soares C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. 10.1097/xeb.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponic P., Varcoe C., Smutylo T. (2016). Trauma- (and violence-) informed approaches to supporting victims of violence: Policy and practice considerations. Victims of Crime Research Digest, (9). https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/victim/rd9-rr9/p2.html

- ProQoL.org. (2019). The ProQoL Measure in English and Non-English translations. https://proqol.org/ProQol_Test.html

- Purkey E., Davison C., MacKenzie M., Beckett T., Korpal D., Soucie K., Bartels S. (2020). Experience of emergency department use among persons with a history of adverse childhood experiences. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 455. 10.1186/s12913-020-05291-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathert C., Wyrwich M. D., Boren S. A. (2013). Patient-centered care and outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Medical Care Research and Review, 70(4), 351–379. 10.1177/1077558712465774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauvola R. S., Vega D. M., Lavigne K. N. (2019). Compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress, and vicarious traumatization: A qualitative review and research agenda. Occupational Health Science, 3, 297–336. 10.1007/s41542-019-00045-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson M. M., Coryn C. L. S., Henry J., Black-Pond C., Unrau Y. (2010). Trauma informed system change instrument (TISCI) (2nd Ed.). Southwest Michigan Children’s Trauma Assessment Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson M. M., Coryn C. L. S., Henry J., Black-Pond C., Unrau Y. (2012). Development and evaluation of the trauma-informed system change instrument: Factorial validity and implications for use. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 29(3), 167–184. 10.1007/s10560-012-0259-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodger S., Bird R., Hibbert K., Johnson A., Specht J., Wathen N. (2020). Preparing teachers to teach all students: Initial teacher education and trauma and violence informed care in the classroom. Psychology in the Schools, 57(2), 1798–1814. 10.1002/pits.22373 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum A., Choi M. J., Stover C. (2018). Development of a trauma-informed self-care measure with child welfare workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 93, 108–116. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.07.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum A., Kondrat D. C., Johnco C., Olson K. R. (2015). The role of self-care on compassion satisfaction, burnout and secondary trauma among child welfare workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 49, 54–61. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.12.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Setti I., Argentero P. (2012). Vicarious trauma: A contribution to the Italian adaptation of the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale in a sample of ambulance operators. Giunti Organizzazioni Speciali, 264(59), 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair S., Raffin-Bouchal S., Venturato L., Mijovic-Kondejewski J., Smith-MacDonald L. (2017). Compassion fatigue: A meta-narrative review of the healthcare literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 69, 9–24. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprang G., Ross L., Miller B. C., Blackshear K., Ascienzo S. (2016). Psychometric properties of the secondary traumatic stress-informed organizational assessment. Traumatology, 23(2), 165–171. 10.1037/trm0000108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stamm B. H. (2002). Measuring compassion satisfaction as well as fatigue: Developmental history of the Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue Test. In Figley C. R. (Ed.), Treating compassion fatigue (pp. 107–119). Brunner-Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Stamm B. H. (2005). The ProQOL manual [PDF file]. http://compassionfatigue.org/pages/ProQOLManualOct05.pdf

- Stamm B. H. (2009). Professional quality of life: Compassion satisfaction and fatigue version 5 (ProQOL) [PDF file]. https://proqol.org/uploads/ProQOL_5_English.pdf

- Stamm B. H. (2010). The concise ProQOL manual [PDF file]. https://proqol.org/uploads/ProQOLManual.pdf

- Strand V., Popescu M., Abramovitz R., Richards S. (2016). Building agency capacity for trauma-informed evidence-based practice and field instruction. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 13(2), 179–197. 10.1080/23761407.2015.1014124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’S concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. SAMHSA. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAMHSA-s-Concept-of-Trauma-and-Guidance-for-a-Trauma-Informed-Approach/SMA14-4884.html

- Sukhera J., Watling C. (2018). A framework for integrating implicit bias recognition into health professions education. Academic Medicine, 93(1), 35–40. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundborg S. A. (2019). Knowledge, principal support, self-efficacy, and beliefs predict commitment to trauma-informed care. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 11(2), 224–231. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/tra0000411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwee C. B., Jansma E. P., Riphagen I. I., de Vet H. C. W. (2009). Development of a methodological PubMed search filter for finding studies on measurement properties of measurement instruments. Quality of Life Research, 18(8),1115–1123. 10.1007/s11136-009-9528-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THRIVE. (2011). System of care trauma-informed agency assessment (TIAA) overview [PDF file]. https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/trauma-informed-self-assessment-tiaa.pdf

- Thrive Initiative. (2011. a). System of care trauma-informed agency assessment [PDF file]. https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/ocfs/cbhs/webinars/documents/SOC-TIAA-Agency.pdf

- Thrive Initiative. (2011. b). System of care trauma-informed agency assessment: Family version [PDF file]. https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/ocfs/cbhs/webinars/documents/SOC-TIAA-Family.pdf

- Thrive Initiative. (2011. c). System of care trauma-informed agency assessment: Youth version [PDF file]. https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/ocfs/cbhs/webinars/documents/SOC-TIAA-Youth.pdf

- van Ameringen M., Mancini C., Patterson B., Boyle M. H. (2008). Post-traumatic stress disorder in Canada. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 14, 171–181. 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00049.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk B. A., McFarlane A. C., Weisaeth L. (Eds.). (1996). Traumatic stress: The effects of overwhelming experience on mind, body, and society. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wathen C. N., MacGregor J. C. D., Beyrem S. (2021). Impacts of trauma- and violence-informed care education: A mixed method follow-up evaluation with health & social service professionals. Public Health Nursing. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/phn.12883 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wathen C. N., Varcoe C. (2019). Trauma- & violence-informed care: Prioritizing safety for survivors of gender-based violence [PDF file]. https://gtvincubator.uwo.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/05/TVIC_Backgrounder_Fall2019r.pdf