Abstract

Objective

To advance equity by developing stakeholder‐driven principles of shared measurement, which is using a common set of measurable goals that reflect shared priorities across communities and systems, such as health care, public health, and human and social services.

Data Sources

From October 2019 to July 2021, we collected primary data from leaders in cross‐systems alignment, measurement, and community engagement—including community members and community‐based organization leaders—across the United States.

Study Design

In partnership with equity and community engagement experts, we conducted a mixed‐methods study that included multiple formative research activities and culminated in a six‐week, stakeholder‐engaged modified‐Delphi process.

Data Collection

Formative data collection occurred through an environmental scan, interviews, focus groups, and an online survey. Principles were developed using a virtual modified Delphi with iterative rapid‐analysis. Feedback on the final principles was collected through virtual focus groups, an online feedback form, and during virtual presentations.

Principal Findings

We developed a set of five guiding principles. Measurement that aligns systems with communities toward equitable outcomes: (1) Requires upfront investment in communities; (2) Is co‐created by communities; (3) Creates accountability to communities for addressing root causes of inequities and repairing harm; (4) Focuses on a holistic and comprehensive view of communities that highlights assets and historical context; and (5) Reflects long‐term efforts to build trust. Using an equity‐focused process resulted in principles with broad applicability.

Conclusions

Leaders across systems and communities can use these shared measurement principles to reimagine and transform how systems create equitable health by centering the needs and priorities of the communities they serve, particularly communities that historically have been harmed the most by inequities. Intentionally centering equity across all project activities was essential to producing principles that could guide others in advancing equity.

Keywords: community health, community participation, Delphi technique, health equity, intersectoral collaboration, measurement, social determinants of health

What is known on this topic

Achieving health equity requires creating aligned systems that work together with communities to meet their goals and needs.

A shared measurement system is essential to align efforts around outcomes, evaluate collective progress, improve the quality and credibility of data, and reduce costs associated with collecting and reporting data.

What this study adds

Building shared measurement into systems' structure enables sustained progress toward equitable outcomes through redistribution of power, building partnerships, creating accountability to communities, and facilitating co‐learning.

Five guiding principles show how community members, community‐based organizations, system leaders, service providers, and policy makers can use shared measurement to align decisions, policies, and practices toward equitable health and well‐being.

We found that how we approached the work—with the intention of centering equity across all project activities—was essential to producing principles that could themselves guide others in advancing equity.

1. INTRODUCTION

Achieving lasting and meaningful improvements in individual and population health requires aligning efforts across various systems—organizations, programs, and activities—within communities that directly influence the health and well‐being of community members. 1 Such systems include medical care, public health, housing, education, transportation, justice, and human services. Alignment acknowledges that inequities in health outcomes result from policies and practices that inequitably benefit some groups and burden others.2, 3 These differences in lived circumstances, also called social determinants or social drivers of health, 4 have been recognized for decades. However, fragmentation across systems hinders efforts to improve health equity in communities (i.e., where every individual has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible), 5 and to understand the most effective ways of making such improvements. Also, achieving health equity requires that aligned systems work with communities. 6 Otherwise, systems leaders will not understand community interests and priorities, share values, and establish trustworthiness in the communities they serve. 7

Cross‐system initiatives can use different strategies to facilitate alignment. 8 One such strategy is shared measurement. As one of the five conditions of the Collective Impact approach, shared measurement is defined as “collecting data and measuring results consistently across all participants to ensure efforts remain aligned and participants hold each other accountable.” 9 , 10 Shared measurement plays an important role in priority‐setting, investment, resource allocation, policy making, and evaluation. As an example of a cross‐system initiative that uses shared measurement as a strategy, the Well Being In The Nation Measurement Framework offers a set of common measures to assess and improve population and community health and well‐being across systems. Another example is Vermont's Health in All Policies Task Force, which developed a Dashboard for Healthy Communities with performance metrics contributed by all partners, promoting a shared vision, and showcasing leadership across systems. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14

Many such cross‐system initiatives have also centered on community voices. For example, San Antonio's city council convened 6000 residents in 2010 to develop a vision for an equitable community and determine a long‐term sustainable strategy to address inequality and respond to community needs. However, questions remain about how best to harness the power of shared measurement to effectively align systems with communities by using a common set of measurable goals that reflect shared priorities toward equity.

This paper describes an iterative stakeholder‐ and community‐driven process to develop principles—a set of fundamental values—for how shared measurement can be used as a strategy by cross‐systems initiatives to advance equity and center the needs and priorities of communities. The principles are for community members, systems leaders, service providers, and policy makers working in cross‐systems efforts. In developing the principles, our research questions were: (1) What principles for shared measurement drive the alignment of systems and communities toward equitable health outcomes? (2) How do we use shared measurement in a way that makes inequities visible and enables actions across systems to address those inequities?

2. METHODS

2.1. Design

We conducted a mixed‐methods study that included multiple formative research activities and culminated in a six‐week, stakeholder‐engaged modified‐Delphi process. All study activities were approved by the American Institutes for Research Institutional Review Board (IRB00000436).

2.2. Modeling equity

From the outset, we recognized that a genuine commitment to advancing health equity required an equity‐centered process of conducting the work, from start to finish. This included attention toward those who had opportunities to conduct and shape the work, and how the work was carried out. Our team included researchers who brought diversity in expertise (such as qualitative and quantitative methods, equity, health services research, and engagement) (THB, KF, TD, TC, HD, MMa, and ES); community organizers with expertise in equity, social justice, community‐engaged research and working with community‐based organizations (PCR, MMu, and AR), and expert facilitators specializing in equity and co‐creation (EPS and WP). Together, the team reflected diversity in race, ethnicity, education, and experience. In designing this project, we intentionally implemented a project management approach that focused on collaboration, partnership, power‐sharing, transformational relationships, and a commitment to advancing equity.

We extended this intentionality as we convened a seven‐member steering committee of leaders in cross‐systems alignment, measurement, and community engagement to provide strategic guidance, technical expertise, and accountability throughout all aspects of the project. We leveraged the steering committee's expertise in setting the project's objectives; understanding the landscape of measurement across local, state, and national levels and how we could build on existing knowledge; structuring project activities to elevate, embrace and value different perspectives and lived experiences; and continuously reflecting on learnings and how this work advances the field of shared measurement.

Throughout the project, we implemented processes that reflected our commitment to inclusion and equitable partnership. To foster shared ownership of data gathered from communities, all partners had full access to collected de‐identified data, were involved in data analysis, interpretation of results, and shared sensemaking, and received a summary of findings for distribution to relevant stakeholders including community‐based organizations (CBO) networks. Further, we implemented a communication strategy that included frequent engagement of the team and internal and external feedback loops.

2.3. Formative research activities

To lay the groundwork for the development of the principles, we completed formative research activities between October 2019 and July 2020. These included: (1) conducting an environmental scan of existing cross‐systems alignment initiatives 15 ; (2) developing use cases for six purposively selected initiatives 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ; (3) surveying CBOs about their experiences servicing communities before and during the early months of the COVID‐19 pandemic 22 ; and (4) conducting virtual focus group listening sessions in six distinct communities 23 (Figure S1). The results of these activities provided a foundation for the Delphi process, including providing shared definitions and examples to set level among the diverse group of Delphi panelists; providing detailed, concrete examples to ground the discussion in real‐world experience; centering what was important to community members; and informing an initial set of nine draft principles. (see Figure S2).

2.4. Developing the principles

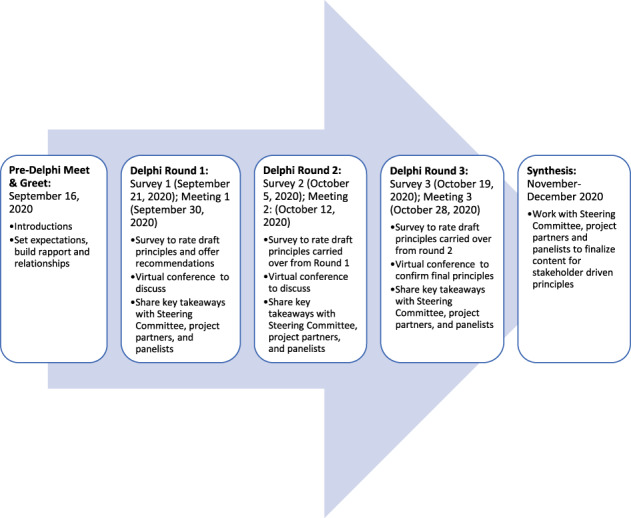

To develop the principles, we conducted a six‐week (9/16–10/28/2020) virtual modified Delphi process with an 18‐member stakeholder panel (Figure 1). The process included three rounds of participant feedback. Each round included an online anonymously‐rated survey, followed by a facilitated virtual meeting.

FIGURE 1.

Modified Delphi process to develop guiding principles [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The first survey included the nine draft principles developed based on learning from the formative activities (see Table S1). These principles framed the discussion at the first virtual meeting. Each virtual meeting included time for panelists to discuss their opinions and perspectives about the current set of principles in real‐time before completing subsequent questionnaires. We revised principles between meetings according to survey and meeting feedback.

2.5. Participants

To identify panelists for the modified Delphi, 24 we sought to include up to 20 individuals on the panel who were leaders or change agents in the field of cross‐systems partnerships to advance health equity and people with a vested interest in cross‐systems partnerships that lead to sustainable gains in health equity. To guide the identification of panelists, we outlined four critical perspectives of interest: (1) community members with lived experience navigating aligned and unaligned systems (e.g., community residents, grassroots community organizers); (2) advocates for community and health equity (e.g., community health workers); (3) bridge‐builders who foster cross‐systems collaboration and alignment (e.g., multi‐sector and community data sharing learning collaboratives); and (4) implementers at various levels representing various systems including health care, public health, and human and social services (e.g., state or local government policy makers, practitioners, community‐based organizations). These perspectives represented various levels of influence and ensure that the principles developed were actionable and rooted in diverse real‐world experiences. We created an initial list during the formative research activities. Then we applied a purposeful sampling approach to identify a diverse mix of priority and alternate candidates with both lived and learned experience. We distributed email invitations in three waves and recruited a final panel of 18 experts with experience in working to understand or address the needs and priorities of communities that have perpetually been excluded, marginalized, and disadvantaged by inequitable, systemic policies, and practices (Table 1). All panelists received equal compensation for their time and participation.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Delphi panelists

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Panelists (n = 18) | |

| Primary perspective | |

| Community members with lived experience navigating aligned and unaligned systems | |

| Community member with lived experience | 4 (22%) |

| Advocates for community and health equity | |

| Community Advocate | 1 (6%) |

| Community‐based organization (CBO) | 2 (11%) |

| Bridge‐builders who foster cross‐systems collaboration and alignment | |

| Bridge‐builder | 5 (28%) |

| Implementers at various levels, such as state or local government representing various systems including health care, public health, and human and social services | |

| Implementer—National level | 3 (17%) |

| Implementer—Local, community‐level | 3 (17%) |

| Geographic location | |

| Atlanta, GA | 2 (11%) |

| Boston, MA | 2 (11%) |

| Chapel Hill, NC | 2 (11%) |

| Chicago, IL | 2 (11%) |

| Detroit, MI | 2 (11%) |

| Los Angeles, CA | 1 (6%) |

| San Francisco, CA | 2 (11%) |

| Washington, DC | 4 (22%) |

| Wenatchee, WA | 1 (6%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 13 (72%) |

| Male | 5 (28%) |

| Nonbinary | 0 |

2.6. Approach

2.6.1. Preparation

We recognized the importance of building relationships with our team and within the panel, including creating a separate space for the community experts to connect before the start of the Delphi process. To meet this need, we hosted two introductory meet‐and‐greets before the first round, one for the full panel and one dedicated exclusively to community representatives, including panelists who were community members, community advocates, CBO leaders, or implementers at the local community level. In both meet‐and‐greets, we acknowledged existing power dynamics, explained the process to set expectations for equitable participation, answered questions, and led activities to familiarize panelists with one another and our team. In the meet‐and‐greet for community representatives, we also reiterated the intentional centering of community voices in the work, discussed channels for directly and indirectly communicating concerns or suggested redirections, and introduced community partner Community‐Campus Partnerships for Health as a resource.

To facilitate mutual understanding and prepare for constructive dialogue in advance of the first Delphi meeting, we shared a resource guide that included definitions, a summary of formative research learnings, a framework explaining project goals and concepts, and the nine draft principles. Recognizing different communication preferences and learning styles, we provided materials in a variety of formats (written documents and an 8‐minute introductory video) 25 and created opportunities for contributions via group discussions, individual surveys, and written comments.

2.6.2. Three‐round modified‐Delphi process

Surveys

At the start of each round, we administered an online survey via SurveyShare before each panel meeting. 26 Each survey presented the set of principles (modified between each round of data collection based on prior panel feedback) and asked panelists to rate and re‐rate (if applicable) each of the draft principles in terms of importance for inclusion. Panelists rated the importance of inclusion using a 4‐point Likert scale: (1) omit, (2) possible candidate for inclusion, (3) desirable candidate for inclusion, and (4) essential for inclusion. 27 The survey also included open‐text fields for each principle where panelists could offer recommendations for modified wording of the principles and their corresponding descriptions, as well as for new principles to consider. The final survey also included open‐ended questions about considerations for implementation of the principles. Surveys were open for a 3‐day period. All responses were anonymous. Upon analyzing the results, we developed and shared a summary of key takeaways with panelists and the Steering Committee.

Meetings

Following each survey, we convened Delphi panelists in a virtual, 90‐minute session to review survey results and discuss principle recommendations. Before each meeting, we sent an email reminder with a summary of key takeaways from the survey to help guide the discussion.

Two expert facilitators (EPS & WP) co‐moderated each meeting, which we structured to include a combination of full‐ and small‐group interaction (breakout rooms) and inclusive activities that incorporated and demonstrated the value of all perspectives (e.g., open space). Using detailed moderator guides, facilitators engaged participants in establishing norms that set expectations and intended outcomes, communicated meeting objectives and guiding questions, set the tone for the discussion by acknowledging external events/factors that might impact reactions, asked probing questions to uncover perspectives on the principles, and recapped learnings and reflections at key points in time during the meeting.

At the beginning of each meeting, we reiterated our expectations and norms for virtual interaction, such as encouragement to be on video if possible and to mute when not speaking. We also reviewed the agenda for the session including objectives and questions of the day (Table S3). Before starting each content discussion, facilitators engaged the panel with icebreaker/warm‐up activities such as presenting a meaningful object to the group, creating word clouds, and sharing a word that symbolized what this project means to them in an effort to break barriers and build trust within the group. Throughout, facilitators encouraged free sharing of ideas and opinions; equal and collaborative participation; and as appropriate to the task at hand, creativity, and out‐of‐the‐box thinking. We offered and held one‐on‐one meetings with any panelists who missed a meeting or had additional thoughts to share.

All meetings were audio‐recorded with panelists' permission. After each meeting, we shared takeaways, meeting notes, and recording links with panelists and the Steering Committee for transparency and convenience. At the end of the modified Delphi process, we asked panelists to share feedback on their experiences and reflections on the process and principles.

Analysis

Given the progressive nature of the modified Delphi and the need for interim analysis and revision between rounds to inform subsequent activities, we applied an iterative, rapid‐analysis approach, the sort and sift, think and shift method. 28 With the goal of connecting emergent findings and concepts across surveys and meetings, we developed structured memo templates for analysis with sections for existing principle language, panel recommendations for revisions to language or principle concepts, newly proposed principles, and general comments. We created two dedicated analysis teams. First, two analysts summarized survey ratings descriptively using frequencies and percentages, with the views of all panelists equally weighted. Based on survey ratings, we grouped the draft principles into three categories:

Prioritized Principle: If at least 75% of participants rated a principle in the “essential” category.

Principle to Consider for Omission: If at least 75% of participants rated a principle in the “omit” category.

Potential Principle: All remaining principles—if less than 75% of participants rated a principle in the “essential” and/or “omit” category.

Analysts reviewed and categorized open‐ended responses (rationale for principle ratings, suggestions, additional comments) and prepared memos summarizing key themes (takeaways) regarding principle modifications.

After each meeting, we held 1‐hour team debrief calls to discuss initial interpretations and identify areas of alignment or divergence with survey feedback, proposed redirection, and modifications, or new concepts for incorporation into the principles.

A separate team of two analysts independently, then collectively, reviewed meeting transcripts and notes and prepared memos highlighting new ideas and panel‐endorsed changes to or confirmation of principle language. All four analysts met to systematically categorize and compare the data across sources, resolving discrepancies in interpretation, identifying thematic patterns, and drawing connections across survey and panel meeting content to identify areas of convergence. Across Delphi rounds, the team reflected on what we learned relative to prior feedback and identified areas where additional probing would be helpful to further elicit or support the determination of consensus. Together, analysts revised the draft principles and included these revised principles, as appropriate, in the next survey.

Following the completion of the Delphi process, we synthesized findings throughout the process and drafted the final principles. We shared this draft with our panelists and advisors and used their feedback to reach a consensus on the final set of principles.

Feedback on the final principles

From May to July 2021, we facilitated feedback cycles with intended audiences—systems leaders and stewards, CBOs, and community members engaged in cross‐systems initiatives—to get their reflections and considerations for practice needed for sustained uptake and use of these principles. These feedback cycles included sharing what we learned about shared measurement and the principles; listening to audiences' reflections, questions, and considerations for practice; and synthesizing their feedback to inform principles adoption. We shared the principles, a companion guide, 29 and other materials through presentations, features in newsletters, and posts on digital forums and social media; during meetings with systems leaders and stewards; and through the development of social‐media‐friendly videos about putting the principles into practice. 30 We gathered audience members' reactions to the principles via an online feedback form (12 completed forms); two listening sessions (17 attendees who represented each of our intended audiences); and during six national presentations that included virtual workshops, webinars, and an annual research meeting. We then synthesized reactions to the principles and considerations for putting the principles into practice.

3. RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, Delphi panelists represented various geographic locations across the United States. Over half (56%) of the panel represented community interests. Three panelists (17%) were community members who had participated in our focus group listening sessions. Five panelists (28%) were bridge‐builders, and 6 (33%) panelists were implementers at the national and local levels.

Across Delphi rounds, survey response rates were 67%, 67%, and 61%, respectively. In addition, meeting attendance rates were 70%, 89%, 94%, 72%, and 89% across the community‐centered and full panel Meet & Greets and three Delphi rounds, respectively.

Table 2 details the evolution of the principles over time, based on key points from surveys and panel meeting discussions, suggestions for principle revisions, and modifications applied in each round of the modified Delphi process. We began with nine draft principles and added, combined, or eliminated principles based on feedback gathered over three rounds of surveys and meetings. We also added a preamble to contextualize the principles and glossary of key terms based on recommendations from panelists.

TABLE 2.

Delphi panel feedback on principles, by round

| Modified Delphi round | Combined key points from survey and meeting | Suggestions | Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 |

|

|

|

| Round 2 |

|

|

|

| Round 3 |

|

|

|

3.1. Final principles

In the third and final survey, agreement on the five principles as being “essential” or “desirable” ranged from 73% to 100% (see Table S2). During our final meeting, panelists provided feedback on the remaining principles. This feedback included suggestions for further refinement and organization. No panelists offered any objections to including the five principles in the final set (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Final principles

| Final principles for using shared measurement as a strategy for alignment to advance equity | Expanded definition |

|---|---|

| Measurement that aligns systems with communities toward equitable outcomes… | |

| Requires up‐front investment in communities to develop and sustain community partner capacity; |

|

| Is co‐created by communities to center their values, needs, priorities, and actions; |

|

| Creates accountability to communities for addressing root causes of inequities and repairing harm; |

|

| Focuses on a holistic and comprehensive view of people and communities that highlights assets and historical context |

|

| Reflects shared values and intentional, long‐term efforts to build and sustain trust. |

|

The first principle details how investment is essential to building authentic partnerships among stakeholders engaged in measurement. As one panelist stated, “There is a lot more that happens in the research process that I do feel that communities are so often left out of. It is design, it is data collection, it is data interpretation, dissemination of the research, publishing…What investment is needed for those partnerships to be collaborative not be top down as they have been historically?” (Bridge‐builder, cross‐systems collaboration) Panelists prioritized this principle as foundational and the precedent for all others.

In developing the second principle, panelists emphasized the need to shift power so that no one group or system dominates the measurement process or dictates what is measured: “You have to get the power ready to share. Then invite communities to share that power.” (Community member with lived experience) For the third principle, panelists highlighted the importance of communities defining when measurement itself causes harm, such as when measuring inequities is used to reinforce negative narratives about communities or when inequities are highlighted but not addressed. Therefore, measurement can be used as a tool for accountability through goal setting, progress tracking, and transparency. The fourth principle reflects panelists' emphasis on acknowledging and highlighting communities' strengths, resilience, and resources, not just areas for improvement and balancing the numbers with narratives and stories that provide context and deeper understanding.

The fifth and final principle emphasizes that community members' trust is earned over time and that measurement should reinforce trust, relationship building, and accountability. Throughout the process, panelists reiterated the importance of framing these principles as laying out a core set of values to help systems and communities work together, recognizing that shared measurement is a journey: “We must view this as iterative. This is a starting point, and we want to strive to improve it over time.” (Implementer‐local, health care)

3.2. Feedback on the final principles

After finalizing the principles, we solicited input through feedback cycles from systems leaders and stewards, CBOs, and community members engaged in cross‐systems initiatives.

3.2.1. Reactions to the shared measurement principles

Stakeholders' expressed that the principles are “on target,” “transformative,” and timely given the COVID‐19 pandemic and the country's reckoning with systemic racism and inequities. One CBO leader said, “[S]ometimes the language about shared‐measurement or accountability or systems change or racism gets co‐opted by the institutions that we are trying to change, and the [words] lose their critical mileage or value. The principles provide fresh language to talk about things that we've been talking about for years and years.” Stakeholders connected with the principles' focus on equity and the need to center communities' perspectives in measurement to avoid reinforcing systemic racism. For example, community members discussed how better engagement can improve accountability to the communities they serve; CBO leaders shared how community members can use the principles to hold those in power accountable.

3.2.2. Putting the principles into practice

Stakeholders identified several barriers for putting the principles into practice, including systems not sharing power with communities, lack of a culturally welcoming environment to support community members' involvement in cross‐system initiatives, inadequate upfront investment in community capacity building, and an absence of stable funding to develop long‐term and sustainable partnerships.

Stakeholders also identified resources and support to put the principles into practice. Identified supports included participation in communities of practice or affinity groups to share challenges, best practices, and solutions; receiving individual coaching and technical assistance on implementation; developing long‐term relationships between systems and community partners; investing in long‐term funding of CBOs and communities; and training staff within systems and funders to understand communities' perspectives.

4. DISCUSSION

Leaders across systems and communities can use these shared measurement principles to drive transformation and reimagination of how systems create equitable health by centering the needs and priorities of the communities they serve, particularly communities that historically have been harmed the most by inequities. Measurement that aligns systems with communities toward equitable outcomes: (1) Requires upfront investment in communities; (2) Is co‐created by communities; (3) Creates accountability to communities for addressing root causes of inequities and repairing harm; (4) Focuses on a holistic and comprehensive view of communities that highlights assets and historical context; and (5) Reflects long‐term efforts to build trust.

4.1. Addressing root causes of inequities through shared measurement

In the United States, our current systems produce, and were often designed to produce unequal treatment and outcomes. 31 In their discussion of an equity agenda for the field of health care quality improvement, O'Kane and colleagues 32 argue that a more equitable health care system will not emerge from individual programs, payment models, delivery approaches, or interventions. Partnership with individuals and communities who have experienced inequities ensures that change efforts advance equity, rather than reinforcing existing inequities. Community leadership is essential to defining problems, cocreating solutions in partnership with systems, and using measurement to advance equity. Our shared measurement principles illustrate one way to build equity into the structures of programs by integrating communities' priorities, needs, and values into measurement efforts that guide quality improvement, transparency, and accountability mechanisms.

4.2. Equity‐centered process is essential

There are many variations of the traditional Delphi method. Online modified Delphi approaches, such as the RAND/PPMD Patient‐Centeredness Method, engage diverse groups of stakeholders with the addition of direct interaction among panelists via iterative group discussions to generate ideas, rate draft recommendations, discuss the rationale for ratings and suggestions, and reconsider ratings in light of these discussions. 33 , 34 Because of the effectiveness of this method in equitably engaging patients and other experts across a variety of fields to develop clinical practice guidelines and other consensus‐based policy recommendations, it served as an appropriate and viable option to bring together participants from across the country in a virtual format. By using a modified Delphi process, we were able to systematically and progressively develop the principles collaboratively with the members of our Delphi panel. We further tailored the process to align with the needs of our panel using a continual dedication to centering stakeholder voices. Especially important for equitable engagement was intentionally preparing stakeholders with different lived and learned experiences to work together by facilitating mutual understanding and building relationships in advance of the Delphi process. During the Delphi, we garnered trust in the process by reflecting back to panelists on how we understood and acted on their recommendations while making space to gather feedback on further revisions.

Beyond the Delphi process, we intentionally structured every aspect of the project as a co‐creation process of listening, discussion, drafting, review and reflection, revision, and more listening. We practiced this co‐creation at multiple levels—within our team; with our steering committee; and with external stakeholders such as the community members, alignment practitioners, and bridge builders who participated in the Delphi process or formative activities. This attention to how the work was done—including our people, approach, and values as a team—has helped us develop and live our own principles over the course of the project. Within the process of co‐creation, we included mechanisms for transparency and accountability within our team and across our collaborators. This included routinely sharing out notes, insights from meetings, and the changes we made—whether to our approach or products—to show that we had acted on feedback. We established the practice of weekly reflections back to the extended team to facilitate ongoing dialogue and connect dots across team efforts. We also created space for relationship‐ and trust‐building. These principles for shared measurement reflect our inclusive and equity‐focused process, which may broaden the applicability of these principles to communities and systems working together to address inequities.

Kania and colleagues 35 have a similar reflection in discussing centering equity in the Collective Impact approach, stating “changing structure without shifting relationships, power dynamics, and mental models can lead to irrelevant, ineffective, unaccountable, and unsustainable solutions. This tendency particularly holds if the solutions were developed in a context where marginalized groups have no voice and power.” By bringing people into the process of measurement, we can address the ways that structural racism and other systemic inequities are built‐in at structural, relational, and transformational levels. Transforming how we conduct measurement is a mechanism for shifting power because the measurement is a part of priority‐setting, investment, resource allocation, policy making, and evaluation. A necessary part of rebalancing power happens through partnerships and co‐creation in choosing what to measure, why, how, and what it means. It's also an important mechanism for accountability because it gives community members tools to define success on their own terms, monitor progress toward those goals, and reshape narratives.

4.3. Limitations

Although our panel was diverse, the results may not be reflective of the experiences and perspectives of all communities. We conducted the modified Delphi process during the upheaval of the initial first six months of the COVID‐19 pandemic which affected the availability of panelists. Although response rates varied across surveys and not all panelists attended every meeting, we achieved strong participation rates across the meetings which still allowed panelists who did not complete the survey to provide input and feedback. While we did provide one‐on‐one follow‐up opportunities to gather individual feedback, participation may have been higher if data had been collected before the pandemic. We encouraged the use of video on group calls and thus, the lack of full anonymity throughout the process may have influenced the results. In addition, we have not yet formally evaluated the application of the shared measurement principles. However, gathering additional data through an online feedback form and listening sessions helped identify needs for adoption and application of the principles. Lastly, while we were intentional in centering equity in our team and throughout our process, we recognize that we have much work to do. Inequities are still reflected in our team and our work, despite our best efforts. The work of equity is a continuous journey of unlearning, relearning, and reimagining.

4.4. Implications

Shared measurement can enhance efforts to advance equity by rebalancing power, building partnerships, creating accountability to communities, and facilitating co‐learning. Our five guiding principles show how community members, system leaders, service providers, and policy makers actively engaged in cross‐systems efforts can use shared measurement as a strategy to align decisions, policies, and practices toward equitable health and well‐being. We found that how we approached the work—with the intention of centering equity across all project activities—was essential to producing principles that could themselves guide others in advancing equity and demonstrates the transformative power of inviting community leaders into the process of aligning and redesigning systems. Once built into systems' structure, shared measurement becomes a tool for sustaining change by showing progress toward specific outcomes defined by communities.

4.4.1. Next steps

Based on feedback from systems leaders and stewards, CBOs, and community members engaged in cross‐systems initiatives, we developed three concrete recommendations to move the principles into action. First, use communities' own stories and narratives as a foundation for authentic partnerships with communities on measurement. To shift measurement from supporting the status quo to driving systems change, new narratives need to be developed and adopted using stories that are owned by communities. This involves seeing communities as essential in defining problems, cocreating solutions through partnerships among systems and communities, and using measurement to advance equity.

Second, provide guidance and support systems and communities to move principles from theory to action. Stakeholders expressed an urgency for putting the principles into action. Cross‐system initiatives could take initial steps to pilot test the principles, learn from each other, and make the necessary changes to adapt the principles to fit their needs. This continuous process will help move the principles from theory into action.

In addition, systems and communities need support in the long‐term process of repairing relationships and building and maintaining trust. Cross‐systems initiatives and communities need time to be reflective, address harms, repair relationships, and build and maintain trust. While taking steps to put the principles into action, initiatives can simultaneously invest in capacity‐building to support the codesign process in measurement which can facilitate long‐term partnerships to advance health equity.

Third, shift the funding landscape to enable community‐led measurement based on authentic partnership. Current funding practices are directive to systems and communities in determining goals and partnerships, how outcomes should be achieved, and how success is measured. To put the shared measurement principles into practice, funders can fund community‐led initiatives. Community leaders can determine their communities' priorities, choose relevant partners from local systems and other stakeholders, and set agendas and processes to achieve their pre‐determined priorities.

5. CONCLUSION

Shared measurement can help reimagine and transform how systems create equitable health through redistribution of power, partnerships, accountability, and co‐learning with the communities they serve, particularly communities that historically have been harmed the most by inequities. These five guiding principles show how community members, CBOs, system leaders, service providers, and policy makers actively engaged in cross‐systems initiatives can use shared measurement as a strategy to align decisions, policies, and practices toward equitable health and well‐being.

Through sustained, collective, and intentional activities, we can measure progress toward defined standards of equity.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Support for this project was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Grant IDs: 76570 and 78502). The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation.

Supporting information

Table S1 Draft set of 9 principles

Table S2. Survey ratings, by round

Table S3. Delphi meeting agendas

Figure S1 Summary of formative activities to inform Delphi process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is the result of collaboration among many people with both lived and learned experts who contributed ideas, insights, and effort. A full list of contributors is available at https://www.air.org/project/cross-sector-measurement-advance-health-equity. We thank the many individuals who shared their time and insights with us to inform this work, including project staff, advisors, and clients; subject matter experts; Delphi panelists; Steering Committee members; and community members and champions from Asheville Buncombe Institute of Parity Achievement, Cincinnati All Children Thrive Learning Network, Colorado Black Health Collaborative, Community Schools Initiative, Connect SoCal, Healthy Washington Heights, LA County Homeless Initiative, Multicultural AIDS Coalition, SA2020, The Community for the Advancement of Family Education, The Dr's. Aaron and Ollye Shirley Foundation, and Vermont Health in All Policies.

Hilliard‐Boone T, Firminger K, Dutta T, et al. Stakeholder‐driven principles for advancing equity through shared measurement. Health Serv Res. 2022;57(Suppl. 2):291‐303. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.14031

Funding information Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Grant/Award Numbers: 76570, 78502

REFERENCES

- 1. Association of State and Territorial Health Officials . Maximizing limited resources through cross‐sector partnerships. Integration Forum. 2017. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.astho.org/uploadedFiles/Programs/Health_Systems_Transformation/Primary_Care_and_Public_Health_Integration/Maximizing-Limited-Resources-Through-Cross-Sector-Partnerships.pdf.

- 2. Institute of Medicine . Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Research. The National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lavizzo‐Mourey R, Besser R, Williams D. Understanding and mitigating health inequities – past, current, and future directions. New England J Med. 2021;384(18):1681‐1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anchor Institutions Task Force . Value added: Adopting a “social determinants of health” lens. Marga Inc. 2019. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.margainc.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/AITF-White-paper-on-SDOH.pdf.

- 5. Braveman P, Arkin E, Orleans T, Proctor D, Plough A. What is Health Equity? Robert Wood Johnson Foundation – Achieving Health Equity Collection. 2017. Accessed April 29, 2022. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2017/05/what-is-health-equity-.html.

- 6. Georgia Health Policy Center . Framework for Aligning Sectors with Glossary. Georgia State University; 2021. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://ghpc.gsu.edu/download/aligning-systems-for-health-a-framework-for-aligning-sectors/ [Google Scholar]

- 7. Amarasingham R, Xie B, Karam A, Nguyen N, Kapoor B. Using Community Partnerships to Integrate Health and Social Services for High‐Need, High‐Cost Patients. The Commonwealth Fund; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Georgia Health Policy Center . Equity from a Cross‐Sector Alignment Perspective: Findings from a Literature Review. Georgia State University; 2020. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://ghpc.gsu.edu/download/equity‐from‐a‐cross‐sector‐alignment‐perspective‐findings‐from‐a‐literature‐review/?ind=1586867628227&filename=Aligning%20Barriers%20to%20Equity.pdf&wpdmdl=4753777&refresh=61a7822a612d31638367786. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kania J, Kramer M. Collective impact. Stanford Soc Innov Rev. 2011;9(1):36‐41. Accessed January 26, 2022. doi: 10.48558/5900-kn19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ogain EN, Svistak M, de Las Casas L. Blueprint for Shared Measurement: Developing, Designing and Implementing Shared Approaches to Impact Measurement. NPC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11. About WIN Measures . Well Being in the Nation Network. 2019. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://insight.livestories.com/s/v2/win-measures/2fda874f-6683-49bd-adb2-22f6f3c5a718/.

- 12. Measurement, Learning and Evaluation. Thriving Together. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://thriving.us/measurement-learning-evaluation/

- 13. Caldwell J, LaBoy A, Lanford D, Petiwala A, Raji A, Thomas, K . Existing measures: Anticipating a cross‐sector alignment measurement system. 2020. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://ghpc.gsu.edu/download/existing-measures-anticipating-a-cross-sector-alignment-measurement-system/.

- 14. Vermont Department of Health . Creating Cross‐Sector Action and Accountability for Health in Vermont. 2018. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.healthvermont.gov/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/ADM_CoH_Guide.pdf.

- 15. Mangrum R, Ali M, Cowans T, Dutta T, Schultz E. Using Measurement to Drive Cross‐Sector Alignment towards Equitable Health Outcomes: An Environmental Scan Report. 2020. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/RWJF-CSM-Environmental-Scan-Report-Jan-2020.pdf.

- 16. Dutta T, Childers T, Ali M, DePatie H, Firminger K, Lin A. Aligning Systems with Communities to Advance Equity through Shared Measurement: Cincinnati All Children Thrive Learning Network. American Institutes for Research. 2021. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/Shared‐Measurement‐Use‐Case‐Cincinnati‐All‐Children‐Thrive‐Learning‐Network‐Jan‐2021.pdf.

- 17. Dutta T, Childers T, Ali M, DePatie H, Firminger K, Lin A, Lowers J. Aligning Systems with Communities to Advance Equity through Shared Measurement: Connect SoCal (SB‐375). American Institutes for Research. 2021. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/AIR-Shared-Measurement-Use-Case-Connect-SoCal.pdf.

- 18. Ali M, Childers T, Dutta T, DePatie H, Firminger K, Lin A. Aligning Systems with Communities to Advance Equity through Shared Measurement: The Los Angeles Homeless Initiative. American Institutes for Research. 2021. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/AIR‐Shared‐Measurement‐Use‐Case‐LAHI.pdf.

- 19. Dutta T, Childers T, Ali M, DePatie H, Firminger K, Lin A. Aligning Systems with Communities to Advance Equity through Shared Measurement: SA2020. American Institutes for Research. 2021. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/Shared-Measurement-Use-Case-SA2020-Jan-2021.pdf.

- 20. Childers T, Ali M, DePatie H, Dutta T, Firminger K, Lin A. Aligning Systems with Communities to Advance Equity through Shared Measurement: Vermont Health in All Policies. 2021. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/Shared‐Measurement‐Use‐Case‐Vermont‐Health‐in‐All‐Policies‐Jan‐2021.pdf.

- 21. Ali M, Childers T, Dutta T, DePatie H, Firminger K, Lin A, Lowers J. Aligning Systems With Communities to Advance Equity Through Shared Measurement: the Community Schools Initiative. 2021. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/AIR-Shared-Measurement-Use-Case-Community-Schools.pdf.

- 22. Cowans T, Firminger K, De Patie H. Community‐based organizations survey summary. 2021. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/AIR‐Shared‐Measurement‐CBO‐Survey‐Summary‐April‐2021.pdf

- 23. Cowans T, Firminger K, De Patie H. Knowing It When I See It: Listening to Community Members About What It Means for Systems to Align for Their Health and Well‐Being. 2021. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/AIR-Shared-Measurement-Cross-Community-Summary.pdf.

- 24. Taylor E. We agree, Don't we? The Delphi method for health environments research. Health Environ Res Des J. 2020;13(1):11‐23. doi: 10.1177/1937586719887709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. American Institutes for Research . Aligning Systems with Communities Through Shared Measurement – Project Overview. YouTube. 2021. Accessed April 29, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M2O7NtqBG9U.

- 26. SurveyShare. 2022. https://www.surveyshare.com/.

- 27. Durand M, Dannenberg MD, Saunders CH, et al. Modified Delphi survey for the evidence summarisation of patient decision aids: study protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e026701. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maietta R, Mihas P, Swartout K, Petruzzelli J, Hamilton AB. Sort and sift, think and shift: let the data be your guide an applied approach to working with, learning from, and privileging qualitative data. Qualit Rep. 2021;26(6):2045‐2060. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2021.5013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Childers T, Ali M, Cowans T, Dutta T, Schultz E. Promising Practices: A Companion Guide for Principles to Advance Equity through Shared Measurement. 2021. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/AIR‐Shared‐Measurement‐Promising‐Practices‐Feb‐2021.pdf.

- 30. American Institutes for Research . Co‐creation: a Principle of Shared Measurement to Align Systems and Communities towards Equity. YouTube. 2021. Accessed April 29, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9gPZPEP27MI.

- 31. Hammonds E, Reverby S. Toward a historically informed analysis of racial health disparities since 1619. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1348‐1349. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. O'Kane M, Agarwal S, Binder L, et al. An Equity Agenda for the Field of Health Care Quality Improvement. National Academy of Medicine. 2021. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://nam.edu/an-equity-agenda-for-the-field-of-health-care-quality-improvement/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33. Khodyakov D, Grant S, Denger B, et al. Practical considerations in using online modified‐Delphi approaches to engage patients and other stakeholders in clinical practice guideline development. Patient. 2020;13(1):11‐21. doi: 10.1007/s40271-019-00389-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Khodyakov D, Denger B, Grant S, et al. The RAND/PPMD patient‐centeredness method: a novel online approach to engaging patients and their representatives in guideline development. Eur J Pers Cent Healthc. 2019;7(3):470‐475. Accessed January 26, 2022. http://www.ejpch.org/ejpch/article/view/1750 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kania J, Williams J, Schmitz P, Brady S, Kramer M, Splansky Juster J. Centering equity in collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review. 2021;20(1):38‐45. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/centering_equity_in_collective_impact [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Draft set of 9 principles

Table S2. Survey ratings, by round

Table S3. Delphi meeting agendas

Figure S1 Summary of formative activities to inform Delphi process.