Abstract

An immunocompetent man in his 20s presented with a 24-hour history of severe odynophagia, nausea, vomiting and throat pain. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed severe esophagitis with ulcerated mucosa, exudative debris, haemorrhage and multiple erosions. Biopsy of the oesophageal tissue demonstrated marginated chromatin, multinucleated giant cells and molding of nuclei, consistent with herpes simplex virus esophagitis (HSE). Treatment with oral acyclovir led to the complete resolution of symptoms. The patient subsequently developed dysphagia again, 8 months later. EGD showed furrowing and concentric rings typical of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), a diagnosis confirmed by biopsy. Treatment with a proton pump inhibitor and swallowed topical corticosteroids led to symptomatic improvement. Thus, HSE can occur in immunocompetent hosts and on occasion, HSE may be a harbinger of EoE, as evidenced by our extensive literature review. Mechanical disruption of the mucosal barrier by viruses, facilitating food allergen penetration, and associated immunological signaling abnormalities may be responsible phenomena requiring further elucidation.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal system, Infection (gastroenterology), Immunology

Background

Odynophagia is defined as pain with swallowing (or painful deglutition). The differential diagnosis of odynophagia in a young male is broad (as shown in box 1). In these diseases, concurrent dysphagia can be present.1 Inquiring about the nature and duration of symptoms as well as any associated risk factors may help narrow the differential diagnosis. Infectious, pill-induced and reflux esophagitis are some of the common causes of esophagitis that can present with odynophagia and/or dysphagia. An infectious aetiology of esophagitis could include viruses, fungi and rarely bacteria.2

Box 1. Differential diagnosis for odynophagia (citations 1,2).

Esophageal neoplasm.

Oral ulcer.

Corrosive esophagitis.

Pill-induced esophagitis.

Radiation-induced esophagitis.

Reflux esophagitis.

-

Infectious esophagitis.

Fungal—candida.

Viral—herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus.

Bacterial.

Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common viral causes of esophagitis. Herpes simplex virus esophagitis (HSE) primarily occurs in immunocompromised patients and is readily diagnosed by esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD).3 However, it can also occur in immunocompetent individuals, such as in our patient. HSE is usually treated with antiviral drugs; however, there is no robust data to support mandatory treatment of HSE in immunocompetent patients.4

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is an immune-mediated disease that presents with some of the symptoms also seen in HSE. EoE is diagnosed by the histological finding of eosinophilic inflammation (along with other pathological features) and the associated clinical appearance of the oesophagus in the appropriate clinical setting (atopic patients, eg).5 HSE and EoE are separate entities, and there is no established relationship between the two diseases. However, there have been reported cases of the two diseases occurring in sequence in some individuals. Herein, we present a case in which an immunocompetent patient presented with HSE followed by a de novo development of EoE 8 months later. Overall, this case highlights HSE as a possible trigger for the development of EoE and emphasises the need for continued follow-up of the patient even after the resolution of HSE.

Case presentation

A man in his early 20s with a history of diet-controlled gastro-oesophageal reflux disease presented to the emergency room with a 2-day history of nausea and vomiting followed by an acute onset of odynophagia and severe throat pain without fever. He reported a globus sensation and discomfort in his lower neck and upper chest but denied abdominal pain, retching or any infectious symptoms (including fever, chills, cough, or dyspnoea).

Historically, he denied recurrent infections, or the prior use of immunosuppressive medications and illicit/recreational drugs. The patient had no prior history of malignancy or HIV.

On examination, he was haemodynamically stable with a blood pressure of 155/52 mm Hg, a heart rate of 93 bpm and a temperature of 37.4°C. Oropharyngeal examination was normal without any exudate, erythema, or ulceration. General examination was unremarkable and the patient had no evidence for exanthema, adenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly.

Investigations

In the emergency room, the complete blood count revealed a white blood count of 13.9 x 109/L with 80.8% neutrophils on the differential and no eosinophilia. His other labs, including a basic metabolic panel and HIV screening test, were unremarkable. The CT scan of the chest did not show any evidence of pleural effusion, pulmonary inflammation/infection, mediastinal lymphadenopathy or emphysema (thereby excluding oesophageal rupture or Boerhaave syndrome).

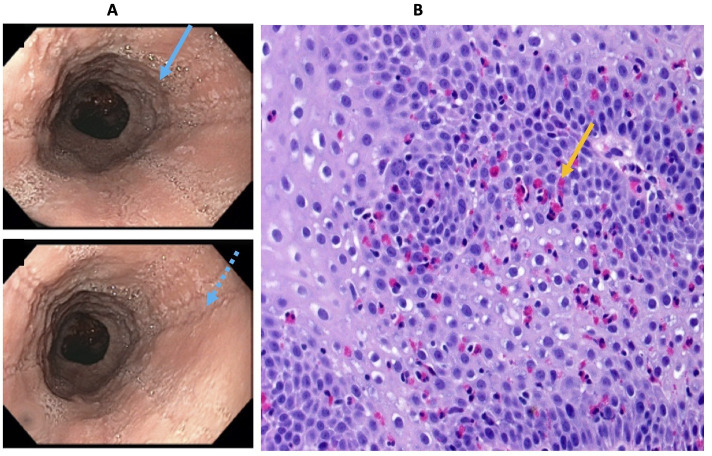

He was hospitalised for further evaluation, due to his inability to maintain good oral intake secondary to odynophagia. He was seen by a gastroenterologist and underwent urgent upper endoscopy, the gold standard test for the evaluation of odynophagia. This revealed severe esophagitis with ulcerated mucosa throughout, areas of haemorrhage, multiple annular white-coloured erosions with exudative debris and granulation tissue (figure 1A, B). The mucosal tissue biopsy showed oesophageal squamous mucosa with cytopathic effect that are classically found with herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. The pathological findings included the three Ms of Multinucleated cells, Margination of nuclear chromatin and Moulding of the nuclei, typical of the cytopoathic effects seen with herpetic infection (figure 1C–E). He was treated with a course of oral acyclovir and discharged after symptomatic improvement. Eight months later, the patient returned to the emergency room eporting of symptoms of active acid reflux and intermittent food impaction. Emergent EGD was carried out, which demonstrated non-erosive gastritis, linear furrowing and concentric oesophageal rings typically seen in EoE (figure 2A). The oesophageal biopsies revealed greater than 15 eosinophils per high-power field, consistent with the diagnosis of EoE (figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Initial presentation with herpetic esophagitis (A–E): Endoscopy demonstrated severe esophagitis with mucosa appearing ulcerated with white plaques (black arrow) and area of haemorrhages (A and B). The histopathology of the biopsied lesion shows findings consistent with viral esophagitis-most likely herpetic esophagitis. These findings include surface epithelial cells showing multinucleation (C, yellow arrow), margination of the nuclear chromatin (D, red arrow) and nuclear moulding (E, green arrow).

Figure 2.

Later development of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) (A, B): EGD demonstrated concentric rings (A, blue solid arrow) and linear furrowing of oesophagus (A, blue interrupted arrow). The biopsies from the proximal/mid/distal oesophagus were consistent with EoE—showing typical squamous mucosa with basal hyperplasia (increased thickness of the layer of small, [high nuclear: cytoplasmic ratio] basal epithelial cells, that gives the epithelium an overall darker appearance) along with numerous intraepithelial eosinophils (B, orange arrow).

An extensive evaluation for immunodeficiency was initiated. This demonstrated normal T-cell enumeration, tryptase and liver functions. IgE immunocap assay demonstrated multiple non-specific positive responses to food allergens (wheat, peanuts, milk) as well as respiratory inhalant allergens (dust mites, grasses, trees). His immunoglobulin levels were normal except for low IgG at 556 mg/decilitre. Since he responded to pneumococcal vaccination, this was felt to be secondary to a protein losing enteropathy (related to his prior herpetic esophagitis or EoE and immunoglobulin shedding). The patient had no evidence for a serious, underlying disorder of immunity that could have predisposed him to these complications.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for odynophagia are shown in box 1. The differential was narrowed to infectious esophagitis based on careful analysis of our patient’s clinical history, physical examintion and lab testing. Given his acute onset of odynophagia, an infectious aetiology for esophagitis was at the top of the differential diagnostic considerations. To evaluate further, gastroenterology was consulted and an EGD was performed. Based on the EGD with biopsy results, the patient was diagnosed with HSE. The patient’s biopsy showed marginated chromatin, multinucleation and moulding of nuclei that were also consistent with HSE (figure 1C–E).

The patient had recurrent symptoms of oesophageal dysphagia and intermittent food impaction 8 months later. The patient underwent a repeat EGD, which revealed greater than 15 eosinophils per high-power field (figure 2B) on biopsy. The differential diagnosis for increased eosinophil numbers in the oesophagus includes proton pump inhibitor-responsive oesophageal eosinophilia, GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease) and EoE. The repeat EGD also revealed linear furrowing and stacked concentric rings of the oesophagus (figure 2A) consistent with EoE.

Treatment

The recommended treatment duration for HSE in an immunocompetent patient is a short course of oral acyclovir (200 mg five times a day or 400 mg oral three times a day for 7–10 days). The recommended dose and duration are higher and longer in patients who are immunocompromised (acyclovir 400 mg orally five times a day for 14–21 days). Intravenous acyclovir can be considered in patients who are unable to tolerate oral acyclovir. The decision was made to treat our patient with oral acyclovir 400 mg three times a day for 10 days to hasten the resolution of symptoms. The patient tolerated oral acyclovir well with rapid improvement.

After the recurrent odynophagia with food impaction symptoms, he was diagnosed with EoE. This condition is treated with education, empiric or testing-directed food allergen avoidance and pharmacotherapy, including proton pump inhibitors and topical glucocorticoids. Dupilumab has been recently approved by the FDA in the USA for refractory or severe EoE. Our patient was treated with omeprazole 40 mg two times per day (orally administered, before meals) and fluticasone propionate 440 μg (swallowed and not inhaled) two times per day, which led to rapid improvement.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient’s odynophagia resolved within 5 days of initiating acyclovir. He was discharged home from the hospital soon after he started tolerating oral fluids. Eight months later, he developed recurrent symptoms and was diagnosed with EoE. He was treated with omeprazole and swallowed fluticasone (administered via metered dose inhaler), with dramatic improvement in his symptoms. He was also placed on a wheat and dairy-elimination diet. He continued to have some dysphagia, odynophagia and food impaction and is being followed by gastroenterology and allergy/immunology for the management of his symptoms secondary to EoE.

Discussion

HSE most commonly occurs in immunocompromised patients, particularly solid organ transplant and bone marrow transplant patients.6 However, there have been case reports of HSE in immunocompetent patients. A review of 56 patients (39 men and 17 women) showed that the mean age at presentation was 35 years among the men.7 Patients with HSE present with symptoms of odynophagia and/or dysphagia associated with fever. Patients can have coexisting herpes labialis or oropharyngeal ulcers as well.8 Our patient had the classic presentation of HSE with the acute onset of odynophagia. Given that our patient presented with HSV esophagitis, more commonly seen in immunocompromised patients, he was evaluated for common immunodeficiency disorders. The patient had no evidence of infectious, neoplastic, iatrogenic or other primary causes of immunodeficiency. His low immunoglobulin levels were most likely secondary to a protein-losing enteropathy related to the inflammatory changes in the oesophagus.

The diagnosis of HSE is usually based on endoscopic findings confirmed by histopathological examination of the biopsied lesions. HSV usually affects the squamous mucosa of the distal oesophagus. During the early stages of infection, HSV causes vesicles, which can coalesce to form volcano-like ulcers with sizes that vary from a few millimetres up to 2 cm. Eventually, in the later stages of infection, the mucosa becomes friable with a potential for superficial haemorrhage.9 10 Histopathology of the biopsy taken from the margin of the ulcer usually shows squamous epithelial cells that have nuclei with characteristic findings of the three Ms: marginated chromatin, multinucleation and moulding of the nucleus (figure 2C–E). The biopsy may also demonstrate Cowdry-type A inclusions, which are eosinophilic or basophilic inclusion bodies in the squamous epithelial cells. Furthermore, immunohistochemical stains can be used to detect HSV-infected cells.6 HSE should be treated with antiviral agents in immunocompromised patients. Options include acyclovir, valacyclovir and famiciclovir with foscarnet restricted to drug-resistant viral infection. However, there are no current guidelines for treatment in immunocompetent individuals. Usually, HSV esophagitis is self-limiting in immunocompetent patients, but case reports and treatment experience suggest that acyclovir can hasten the resolution of lesions.4

Diagnostic criteria for EoE include symptoms related to oesophageal dysfunction (eg, dysphagia, food impaction, food refusal, odynophagia), eosinophilic-predominant inflammation on biopsy (characteristically consisting of a peak value of ≥15 eosinophils per high power field) and exclusion of other causes of oesophageal eosinophilia (such as parasitic disease, inflammatory bowel disease and malignancy).11 EoE is highly associated with allergic diseases. Medical treatment options include proton pump inhibitors and swallowed steroids.12 A relationship between EoE and food allergy exists. Seventy per cent of patients with EoE have evidence of food antigen sensitisation or other atopic conditions.13 The studies assessing the role of allergy testing to predict food triggers of EoE have been inconclusive. Thus, the American Gastroenterological Association provides some guidance on allergy testing in patients with EoE.14 Our patient described above was evaluated by an allergist and was found to have multiple non-specific positive IgE-responses to food and respiratory inhalant allergens leading to an empiric recommendation to avoid dairy and wheat from his daily diet.

Relationship between HSE and EoE

HSE and EoE are different and independent entities. However, there have been rare cases of EoE following HSE. A PubMed search was conducted using medical subject heading (MeSH) phrases: herpes esophagitis (herpes simplex virus, esophagitis) AND EoE. The Boolean operator ‘AND’ was used to combine and narrow the searches. Search results were further refined by restricting to the literature published between 1982 and 2022 and published in the English language. The search yielded 36 articles and of these, only 16 pertained to HSE and EoE.15–30 These 16 articles described 26 cases of HSE and EoE, as summarised in table 1. These cases were reviewed independently by the authors to understand the relationship between HSE and EoE. There are certain patterns that can be inferred from our literature review.

Table 1.

Summary of cases of herpes simplex esophagitis (HSE) and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) occurring sequentially in the world literature

| Case study | Age/sex | Temporal relationship between HSV esophagitis (HSE) and EoE | Immuno compromised? | Reference |

| 1 | 13/M | EoE was diagnosed 2 months after HSE | No | 15 |

| 8/M | EoE was diagnosed 2 months after HSE | No | ||

| 11/M | EoE was diagnosed 5 months after HSE | No | ||

| 16/M | EoE was diagnosed 4 months after EoE | No | ||

| 2 | 26/M | EoE was diagnosed 3 months after HSE | No | 16 |

| 3 | 51/F | HSE and EoE diagnosed concurrently | Yes | 17 |

| 4 | 11/M | EoE was diagnosed 12 weeks after HSE | No | 18 |

| 5 | 30/M | HSE was diagnosed 4 months after EoE | No | 19 |

| 6 | 17/M | EoE was diagnosed 1 month after HSE | No | 20 |

| 36/M | HSE and EoE were diagnosed concurrently | No | ||

| 7 | 4/M | EoE was diagnosed 6 weeks after HSE | Unknown | 21 |

| 8 | 43/F | EoE was diagnosed 7 years after HSE | No | 22 |

| 9 | 17/F | EoE and HSE diagnosed concurrently | No | 23 |

| 10 | 13/M | EoE was diagnosed 1 month after HSE | No | 24 |

| 11 | 20/M | EoE was diagnosed 6 months after HSE | No | 25 |

| 12 | 25/F | The patient had history of untreated EoE for unclear duration and then patient was diagnosed with HSE | Unknown | 26 |

| 27/F | HSE was diagnosed 5 years after EoE | Unknown | ||

| 29/M | The patient was presumed to have clinical history of EoE. However, diagnosis of with EoE and HSE was made concurrently | No | ||

| 30/M | HSE was diagnosed 6 years after EoE | Yes | ||

| 28/M | EGD showed increased eosinophil in asymptomatic patient 9 weeks after HSE | Unknown | ||

| 13 | 20/M | Persistent oesophageal eosinophilia in an asymptomatic patient was diagnosed 4 months after HSE | Unknown | 27 |

| 14 | 19/F | HSE was diagnosed 10 months after EoE | No | 28 |

| 15 | 14/M | EoE was diagnosed 2 months after HSE | Unknown | 29 |

| 16/M | EoE was diagnosed 6 months after HSE | Unknown | ||

| 9/M | EoE was diagnosed 1 month after HSE | No | ||

| 16 | 18/M | EoE and HSE were diagnosed concurrently | No | 30 |

*Table shows sequential development of eosinophilic or herpetic esophagitis in cases reported in the world literature.

EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; F, female; HSE, herpes simplex esophagitis; HSV, herpes simplex virus; M, male.

The majority of patients described (with the two conditions occurring in sequence) were men (76.9%, n=20). The average age for diagnosis of either HSE or EoE was 18 years in men. Similarly, our patient was a young man with a diagnosis of HSE who developed subsequent EoE 8 months later. Our literature review revealed only six female patients with HSE and EoE, suggesting men are more affected. The majority of cases (80.7%, n=21) described had a chronological order between the two diseases and there were only five reported cases where HSE and EoE were diagnosed concurrently. The duration between the two diagnoses was highly variable, ranging anywhere from a few weeks to a few months or even years.

There are baseline differences in the cases described in box 1, which limit our ability to compare and draw conclusions. Though most patients in our literature search were immunocompetent, the immune status of 26.9% (n=7) of the patients was not reported. The patient described in case 14 was on fluticasone propionate for treatment of EoE at the time of the diagnosis of HSE. Thus, perhaps the use of topical glucocorticoids could have predisposed this patient to HSE, though the dosing used makes this an unlikely scenario.

A note on mechanisms

Given the number of cases described in the literature, there is a possible relationship between HSE and EoE. However, it is very unclear which disease is the inciting factor. Currently there are two proposed clinicopathological mechanisms that may explain the temporal relationship between the two diseases. The increased localised inflammation in EoE can make the oesophageal mucosa more susceptible to infections such as HSV. On the other hand, having an HSV infection can cause a breach in the mucosal barrier with increased allergen penetration, which leads to an overactive immune system and eventual disruption of immune tolerance leading to hypersensitivity and eosinophil recruitment.29–31

There are additional molecular interactions between viruses and allergens that might be of relevance to our discussion, and these are summarised in figure 3. Asthma, eczema and food allergy are considered atopic diseases, mediated by the Th2 T cells and canonical cytokines, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 among others. Transcription factor, STAT 6 (signal transducer and activation of transcription signalling) plays a key role in this process.32–34 STAT 6 is also of importance to the function of IL-4 and IL-13, two cytokines which are responsible for eosinophil recruitment, Th2 T helper cytokine expansion as well as IgE synthesis, all hallmarks of Th2-T cell-driven atopic diseases. Similar findings are observed in eosinophilic esophagitis as well.

Figure 3.

This figure demonstrates a potential central role for shared signalling pathway [such as STAT 6 (signal transducer and activation of transcription signaling))]in the molecular pathogenesis of EoE and HSE. Asthma, eczema and food allergy are considered atopic diseases, mediated by the canonical cytokines, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-1 among others. A key role is likely played by the transcription factor, STAT 6. STAT 6 is also of importance to the function of IL-4 and IL-13, responsible for eosinophil recruitment, type 2 T helper cytokine expansion as well as IgE synthesis, all hall marks of atopic diseases. Similar findings are observed in eosinophilic esophagitis as well. At the same time, double stranded DNA viruses such as herpes simplex can also activate STAT 6 using a non-canonical pathway that involves the recruitment of STING (stimulator of interferon genes) in association with IRF3 (interferon regulatory factor 3) that activate gene expression for antiviral chemokines and interferons respectively. It is likely that hyperactivation of STAT 6 can allow shared pathogenesis of both HSE and EoE but this remains to be conclusively demonstrated. This figure was created by Dr. Guha Krishnaswamy specifically for this manuscript. EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; HSE, herpes simplex virus oesophagitis; HSV, herpes simplex virus; IRF, interferon regulatory factor.

At the same time, double-stranded DNA viruses such as herpes simplex can also activate STAT 6 using a non-canonical pathway that involves the recruitment of STING (stimulator of interferon genes) in association with interferon regulatory factor 3, activating gene expression for antiviral chemokines and interferons, respectively.32–34 It is likely that hyperactivation of STAT 6 can allow for the shared pathogenesis of both HSE and EoE, by allowing a skewing to a Th2-dominant pathway. This is speculative and future studies may elucidate these molecular interactions in oesophageal tissue.

Conclusion

Our case and the literature review further highlight the relationship between HSE and EoE. Based on the current literature, we cannot draw firm conclusions regarding a causation or a time frame for both pathologies and, therefore, there is a need for more research in this area. It is imperative to understand the association between the two diseases, as patients can develop complications from either a failure to recognise or the delayed diagnosis of these two diseases.

Learning points.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) esophagitis can present with acute odynophagia concurrently with/without dysphagia.

Though HSV esophagitis is commonly seen in immunocompromised individuals, occurrences in immunocompetent patients have also been described (as in our patient).

The diagnosis of viral esophagitis is based on endoscopic findings. However, the actual confirmation of HSV requires further immunocytological or molecular analysis.

Diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis are comprised of symptoms related to oesophageal dysfunction, eosinophilic-predominant inflammation on biopsy consisting of a peak value of ≥15 eosinophils per high power field and exclusion of other causes of oesophageal eosinophilia.

HSV esophagitis can be followed by eosinophilic esophagitis, due to an unclear mechanism. Therefore, patients with HSE esophagitis need to be followed for the development of new symptoms such as dysphagia or food impaction. In the absence of large epidemiological data, firm recommendations on follow-up and management may be difficult to make.

It is likely that mucosal injury by viral infection results in hyperpermeability to food allergens and resulting allergic inflammation mediated by eosinophils. However, a molecular basis for this intertwined disease cannot be excluded and may involve interactions of immunological and signalling molecules (such as cytokines and STAT proteins) which require further study.

Footnotes

Contributors: HP wrote the first draft and did literature research. The conception and design of the case report were conducted by HP and SMTN. The article was critically revised for publication by HP, SMTN, AH and GK. The patient was treated by GK. GK was responsible for the generation of figures, figure legends, figure 3 (mechanism) and discussion of molecular mechanisms. GK restructured the abstract and ovresaw the organization of the entire manuscript, carrying out detailed editing and proof reading through many interations.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

References

- 1.Feldman M, Friedman LS, Sleisenger MH. Sleisenger & Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilcox CM. Infectious esophagitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;2:567–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grossi L, Ciccaglione AF, Marzio L. Esophagitis and its causes: Who is "guilty" when acid is found "not guilty"? World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:3011–6. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i17.3011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kadayakkara DK, Candelaria A, Kwak YE, et al. Herpes simplex virus-2 esophagitis in a young immunocompetent adult. Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2016;2016:7603484 10.1155/2016/7603484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:3–20. 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Généreau T, Rozenberg F, Bouchaud O, et al. Herpes esophagitis: a comprehensive review. Clin Microbiol Infect 1997;3:397–407. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canalejo E, García Durán F, Cabello N, et al. Herpes esophagitis in healthy adults and adolescents: report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Medicine 2010;89:204–10. 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181e949ed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoversten P, Kamboj AK, Wu T-T, et al. Variations in the clinical course of patients with herpes simplex virus esophagitis based on immunocompetence and presence of underlying esophageal disease. Dig Dis Sci 2019;64:1893–900. 10.1007/s10620-019-05493-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McBane RD, Gross JB. Herpes esophagitis: clinical syndrome, endoscopic appearance, and diagnosis in 23 patients. Gastrointest Endosc 1991;37:600–3. 10.1016/S0016-5107(91)70862-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baehr PH, McDonald GB. Esophageal infections: risk factors, presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology 1994;106:509–32. 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90613-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: proceedings of the agree conference. Gastroenterology 2018;155:1022–33. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson JM, Li R-C, McGowan EC. The role of food allergy in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Asthma Allergy 2020;13:679–88. 10.2147/JAA.S238565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anyane-Yeboa A, Wang W, Kavitt RT. The role of allergy testing in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;14:463–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirano I, Chan ES, Rank MA, et al. AGA Institute and the joint Task force on allergy-immunology practice parameters clinical guidelines for the management of eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2020;124:416–23. 10.1016/j.anai.2020.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fritz J, Lerner D, Suchi M. Herpes simplex virus esophagitis in immunocompetent children: a harbinger of eosinophilic esophagitis? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2018;66:609–13. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quera R, Sassaki LY, Nuñez P, et al. Herpetic esophagitis and eosinophilic esophagitis: a potential association. Am J Case Rep 2021;22:e933565. 10.12659/AJCR.933565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marella HK, Kothadia JP, Saleem N, et al. A patient with eosinophilic esophagitis and herpes simplex esophagitis: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2021;2021:5519635 10.1155/2021/5519635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, Lee K, Lee W. A case of eosinophilic esophagitis associated with herpes esophagitis in a pediatric patient. Clin Endosc 2019;52:606–11. 10.5946/ce.2019.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wichelmann TA, Hoff RT, Silas DN. Acute herpes simplex esophagitis in an immunocompetent adult with eosinophilic esophagitis. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2021;15:1003–7. 10.1159/000521124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bustamante Robles KY, Burgos García A, Suárez Ferrer C. Eosinophilic esophagitis and herpetic esophagitis: cause or consequence? Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2017;109:393–4. 10.17235/reed.2017.4616/2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sehgal S, Darbari A, Bader A. Herpes simplex virus and eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013;56:e1. 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31824d0660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alcaide Suárez N, Santos Fernández J, Fernández Salazar L. Eosinophilic esophagitis after an episode of herpetic esophagitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2019;111:406–7. 10.17235/reed.2019.5903/2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Žaja Franulović O, Lesar T, Busic N, et al. Herpes simplex primo-infection in an immunocompetent host with eosinophilic esophagitis. Pediatr Int 2013;55:e38–41. 10.1111/ped.12027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cristoforo TA, Rietsma K, Wilsey A, et al. Herpes esophagitis with concomitant eosinophilic esophagitis in a child: a case report. Clin Pediatr 2018;57:618–20. 10.1177/0009922817730350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monsanto P, Almeida N, Cipriano MA, et al. Concomitant herpetic and eosinophilic esophagitis--a causality dilemma. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 2012;75:361–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmermann D, Criblez DH, Dellon ES, et al. Acute herpes simplex viral esophagitis occurring in 5 immunocompetent individuals with eosinophilic esophagitis. ACG Case Rep J 2016;3:165–8. 10.14309/crj.2016.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iriarte Rodríguez A, Frago Marquínez I, de Lima Piña GP. A case report: asymptomatic esophageal eosinophilia after herpes simplex esophagitis. controversies in the therapeutic approach. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2018;110:471–2. 10.17235/reed.2018.5508/2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindberg GM, Van Eldik R, Saboorian MH. A case of herpes esophagitis after fluticasone propionate for eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;5:527–30. 10.1038/ncpgasthep1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Squires KAG, Cameron DJ, Oliver M, et al. Herpes simplex and eosinophilic oesophagitis: the chicken or the egg? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;49:246–50. 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31817b5b73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Machicado JD, Younes M, Wolf DS. An unusual cause of odynophagia in a patient with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2014;147:37–8. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Shea KM, Aceves SS, Dellon ES, et al. Pathophysiology of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2018;154:333–45. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen H, Sun H, You F, et al. Activation of STAT6 by sting is critical for antiviral innate immunity. Cell 2011;147:436–46. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karpathiou G, Papoudou-Bai A, Ferrand E, et al. Stat6: a review of a signaling pathway implicated in various diseases with a special emphasis in its usefulness in pathology. Pathol Res Pract 2021;223:153477. 10.1016/j.prp.2021.153477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mougey EB, Nguyen V, Gutiérrez-Junquera C, et al. Stat6 variants associate with relapse of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients receiving long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:2046–53. 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]