Abstract

The rate of Biomedical waste generation increases exponentially during infectious diseases, such as the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which burst in December 2019 and spread worldwide in a very short time, causing over 6 M casualties worldwide till May 2022. As per the WHO guidelines, the facemask has been used by every person to prevent the infection of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and discarded as biomedical waste. In the present work, a 3-ply facemask was chosen to be treated using the solvent, which was extracted from the different types of waste plastics through the thermal–catalytic pyrolysis process using a novel catalyst. The facemask was dispersed in the solvent in a heating process, followed by dissolution and precipitation of the facemask in the solvent and by filtration of the solid facemask residue out of the solvent. The effect of peak temperature, heating rate, and type of solvent is observed experimentally, and it found that the facemask was dissolved completely with a clear supernate in the solvent extracted from the (polypropylene + poly-ethylene) plastic also saved energy, while the solvent from ABS plastic was not capable to dissolute the facemask. The potential of the presented approach on the global level is also examined.

Keywords: Energy saving, Pyrolysis, Biomedical waste, COVID-19, Facemask

Graphical abstract

Nomenclature

- ABS

Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene

- ADFPC

Average daily disposable facemasks per capita

- BMW

Biomedical waste

- CPCB

Central Pollution Control Board

- FAR

Facemask acceptance rate

- FFP

Filtering face-piece

- HDPE

High-density Polyethylene

- LDPE

Low-density Polyethylene

- Mt

Million tonnes

- PE

Polyethylene

- PP

Polypropylene

- PPE

Personal protective equipment

- TDDF

Total daily disposable facemasks

- TP

Total Population

- UP

Urban Population(%)

- WHO

World Health Organisation

1. Introduction

The burst of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID–19) was due to the SARS-CoV-2 virus in December 2019, which soon spread worldwide and converted to the ongoing pandemic (third – wave). To remain safe from the COVID–19 outside clinical facilities, most of the population also started the use of facemasks, gloves, and PPE kits, leading to an exponential growth in biomedical waste worldwide. An estimation of the total daily facemasks used, assuming the total urban population of 35% in India and a mass of a disposable (single-use) mask of about 3.0 g., was conducted [1]. The estimated quantity of disposable facemasks was about 777 m pieces, weighted about 2,331 t/d, out of total medical waste generated of about 26,453 t. A more detailed estimation of the total disposable facemasks on a daily basis used in all the 29 states, the National Capital Territory of Delhi, and seven union territories (UTs: Chandigarh, Daman and Diu, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Lakshadweep, Pondicherry, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and Ladakh) of India was estimated using the following relation formulated [2] and shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Estimated total daily disposable facemasks in the states and union territories (UTs) in India in 2021.

In the estimation of facemasks used, the FAR and ADFPC were assumed to equal 80% and 2 for the year 2021, when the second wave of COVID–19 virus peaked in India. The total population of India in the year 2021 was taken from a report presented by the National Commission on Population under the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, India. In total, about 698 M disposable facemasks were used daily [3]. The average mass of a disposable facemask was measured at about 3.0 g, given the mass of about 2094 t generated due to the disposable facemask on a daily basis only.

Another way to indicate the inflow of facemasks in the society of India can be based on an exponential rise in the market share. As per the “Indian Surgical Masks Market 2021″ report presented by Allied Market Research [4], the value of the surgical mask [5] market will increase from $ 71.73 M in 2019 with a compounded annual growth rate of 10.3% to $157.13 M by 2027. The requirement of about 89 M facemasks was estimated only for worldwide medical professionals in one month of the year 2020, while about 129 × 109 facemasks in the whole world [6]. These estimations show the seriousness of the immediate employment of biomedical waste management strategies for the mitigation of waste generation.

There are various types of facemasks that have been recommended by the WHO and the governing bodies of various countries, as shown in Table 1 . Except for the cloth mask, the row materials for manufacturing the nose and mouth covering layers used for all types of disposable facemasks is the nonwoven plastic polymers such as PP, PE, polyvinyl chloride, polystyrene, polylactic acid, and polyamide [7]. In addition to the layers, the rope or strap to tighten the facemask is prepared using polyurethane and nylon [8]. PP and PE are the types of thermoplastics which can be melted at high temperatures. In addition, only cloth facemasks are used as reusable, but with at least one disposable mask [9]. From the above facts, estimation of quantity, and raw material used for facemasks, it can be inferred that an ample amount of PP and PE plastic waste has been generated in India during the COVID–19 pandemic period.

Table – 1.

Different types of facemasks and their characteristics [10].

| Type of masks | Mask Name | General Characteristics | Material Composition | Appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical or Medical mask | Tie-on surgical facemask | Fluid resistant | 3-ply, pleated rayon outer web with PP inner web |  |

| Classical surgical mask | Protects the wearer from harmful fluids in the form of big drops, splashes, or sprays. | 3-ply, pleated cellulose PP, PE |  |

|

| Sofloop extra protection mask | It is not considered respiratory protection because it does not provide a reliable level of protection against inhaling tiny airborne particles. | 3-ply, pleated blended cellulosic fibres with PP and PE, ethylene methyl acrylate strip, High filtration efficiency down to 0.6 μm | ||

| Surgical grade cone-style mask | Moulded PP |  |

||

| Respirators (Breathing can be difficult while using these masks.) | N95 (N stands for non-Oil) | The minimum size of .3 μm of particulates and large droplets doesn't pass through the barrier | Nonwoven PP fabric, with 95% filtration efficiency, is produced by melt blowing and forms the inner filtration layer |  |

| FFP1 (Identified by a yellow elastic band) | Mainly used as an environmental dust mask. | PP, aerosol filtration efficiency of at least 80% for 0.3 μm particles. |  |

|

| FFP2 (Identified by a blue or white elastic band) | Serves as a protector against viruses of avian influenza, SARS with Coronavirus, pneumonia, and tuberculosis. | 5-ply, PP, 94% filtration efficiency, net reinforced sheet. |  |

|

| FFP3 (Identified by a red elastic band) | Protects against solid and liquid aerosols. Recommended for those who remain in contact with aerosols for prolonged periods. | 5-ply, PP, 99% filtration efficiency. |  |

|

| A mask can be graded as FFP3 only if it is waterproof and extremely impermeable | ||||

| Non-certified mask | Cloth mask | Reusable. Recommended to wear one disposable mask underneath a cloth mask that has multiple layers of fabric. | Cotton used. Vinyl and non-breathable materials are not recommended for masks. | |

Various thermoplastic polymers, such as PP, LDPE, HDPE, polyvinyl chloride, polystyrene, nylons, polylactic acid, polyamide, etc., are used to manufacture single-use disposable facemasks [7]. These polymers, PP and PE of low density and high density, are the primary constituents in the manufacturing of disposable facemasks, as listed in Table 1. The mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties of the primary constituents are of utmost importance to be analysed in Table 2 To prepare a suitable management strategy for the used or discarded facemasks.

Table – 2.

Various properties of polymers used in the manufacturing of the disposable facemasks.

| Property | PP [11] | LDPE [12] | HDPE [13] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm3) | 1.04–1.06 | 0.915–0.92 | 0.94–0.96 |

| Elastic modulus (GPa) | 1.5–3 | 0.2–0.48 | 0.6–1.4 |

| Coefficient of thermal expansion (1/K at 20 °C) | 6 × 10−5 – 1 × 10−4 | 23 × 10−5 – 25 × 10−5 | 12 × 10−5 – 20 × 10−5 |

| Max. Service temperature, short | 140 | – | – |

| Melting point (°C) | 160–168 | 105–120 | 126–135 |

| Specific heat capacity (J/kg. K at 20 °C) | 1,520 | 2,100–2500 | 2,100–2,700 |

| Thermal conductivity (W/m.K at 20 °C) | 0.41 | 0.32–0.4 | 0.38–0.51 |

| Flammability | UL 94 H B | UL 94 H B | UL 94 H B |

| Dielectric constant (at 20 °C) | 2.8 | 2.2–2.3 | 2.3–2.5 |

| Electrical resistivity (Ω.m at 20 °C) | 1013–1014 | 1015 | 1015 |

1.1. Effects of BMW on the environment

Biomedical wastes are exceedingly hazardous, and they could cause major environmental and health problems if they are not treated scientifically and systematically. As per the report, 85% of healthcare wastes are non-hazardous [14], 10% are hazardous and infectious, and the remaining 5% are non-infectious but hazardous waste; if not properly segregated and mixed with municipal waste, this 5% of non-infectious waste can become infectious.

Numerous recent studies also reported the effect of biomedical waste generated on the environment, marine life, humans, animals, etc. The availability of used facemasks on one of the beaches in northern-central Chile with an average density of 0.006 ± 0.002 (mean ± standard error) facemasks per 1 m2 area was reported [15]. A report based on the scale, source, and impact of plastic pollution in the marines with a focus on the use of PPE kits and facemasks due to COVID–19 were published [16].

1.2. Strategies for BMW management

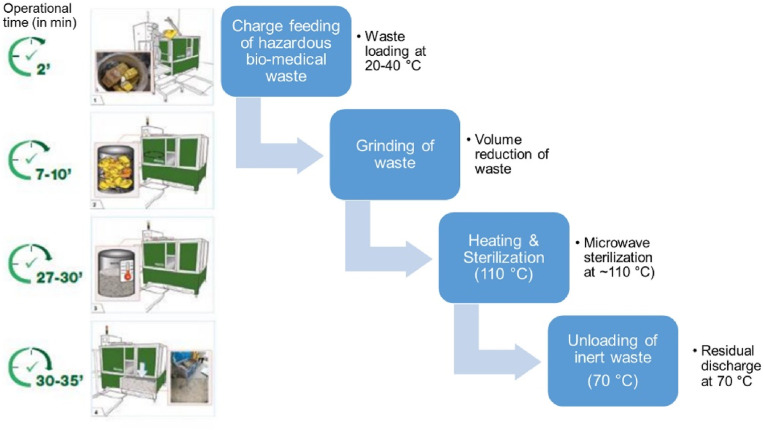

An exposure of surfaces or materials containing SARS-CoV- 2 viruses to the heat at high temperatures for a certain period was recommended to disinfect the biomedical waste in the guidelines shared by the WHO and also in the reported literature. The suggested exposure of virus-containing objects [17] (biomedical waste [18]) to the heat at a temperature of more than 75 °C for 3 min, 65 °C for 5 min, or 60 °C for 20 min. Several disinfection techniques have been reported in the literature based on the exposure of virus-containing objects or infected objects to heat at higher temperatures. A mobile BMW treatment facility, Sterilwave, having a capacity of 80 kg/h, has been reported [19]. The operation of the Sterilwave system consisted of loading, shredding, and heating shredded particles to 100–110 °C using a microwave generator and unloading of residual at 70 °C, as shown in Fig. 2 . The holding time of BMW in Sterilwave was about 30 min. The emission of toxic contaminants, if available in the BMW, the spread of offensive odours around the system, and the high capital cost and a few drawbacks were also reported [19]. Kumar et al. [20] suggested the use of high-intensity UV lights on the used medical objects for nearly 40 min to disinfect the COVID – 19 virus. A transparent acrylic medical waste was fabricated [21]. A bin having a volume of about 200 L to disinfect the COVID-19-contaminated BMW using direct solar radiation was collected [22]. At the ambient air temperature of around 30 °C, a temperature of more than 50 °C was recorded inside the bin, at which the viruses became below levels of detection within 90 min. The medical waste bin cost only $30 but was not effective at an ambient temperature of less than 20 °C.

Fig. 2.

A pictorial presentation of the Sterilwave apparatus [19].

Another popular approach to disinfect or manage the COVID-19 BMW is thermal pyrolysis, where the waste is heated up to a very high temperature in the absence of oxygen and converted into oil, gas, and char based on the composition of the BMW material. This approach is proven suitable for the BMW consisting the plastic polymer. The release of hazardous gases such as Syngas and Cl-2 hydrocarbons from the disposable facemask prepared by using PP and PE limits the use of thermal pyrolysis [23]. In addition to these approaches, the incineration for the facemask, carbonisation for protective cloth, pyrolysis of gloves and goggles, and gasification for the containers are the possible thermal conversion technologies for the BMW treatment to get the energy-related products have been reported [24]. The thermal conversion technologies are based on endothermic processes, where energy in the form of heat is required for the BMW treatment. In thermal pyrolysis, the BMW is heated up to a very high temperature based on the process. The temperature range for various technologies used for BMW treatment is mentioned [24], like, the temperature range is 300–400 °C for torrefaction, 200–300 °C for hydrothermal carbonisation, 350–600 °C for thermal pyrolysis, 800–850 °C for gasification, 700–1200 °C for plasma gasification and higher than 800 °C for the incineration process. The requirement of very high temperatures for the above-said processes motivates us to develop an energy-saving approach to treat BMW.

As per the guideline of CPCB (2020), COVID-19 virus-infected biomedical waste should be disposed of or treated immediately upon receipt at the treatment facility [25]. The transportation of COVID biomedical waste from a generator to the collector further enhances the chances of infection, as the COVID-19 virus remains active on the rigid surface for a few days [26]. Based on the stated guidelines and reported BMW treatment technologies, the authors conclude that:

-

•

The BMW should be treated immediately at the site of waste generation, and transportation of COVID BMW should be avoided to minimise the spread of the virus.

-

•

The release of hazardous gases should be avoided or reduced during the BMW treatment.

-

•

The energy input for the BMW treatment should be minimum.

-

•

The residual of BMW treatment should be stable, and the final dry waste can be used for safe disposal or used as a constituent to a process or product.

With consideration of the above conclusion, the present work employs a novel approach to disinfecting the disposable facemask using a solvent prepared from the waste plastic through the thermal–catalytic pyrolysis [27] process. The use of such solvent has not been reported for the BMW treatment.

2. Preparation and characterisation of solvent and mask dissolution

2.1. Preparation of solvent from pyrolysis of waste plastic

A patent (Application No. 201911037520) has been filed by the team of E-waste Research & Development Centre, IET, Alwar, in the Patent Office, New Delhi, India, on the novel thermal–catalytic pyrolysis process used to get the solvent from the plastic waste. A general description of the solvent extraction, without including the information related to the patent filed, is as follows.

The waste plastic was pyrolysed in a prototype of a batch-type pyrolysis unit, gaseous fuel heated, with a handling capacity of 2 kg waste. The temperature in the pyrolysis [28] unit was kept at about 450 °C in isothermal condition for about 30 min with a heating rate of 20 °C/min from room temperature. The plant for the production of pyrolytic solvent has comprised the reactor assembly, condensing unit, separator, and gas collection systems, as shown in Fig. 3 , and is situated in the E-waste Research and Development Centre, IET, Alwar. The process of pyrolysis was carried out by breaking the waste plastic into small pieces for granulation and feeding it into the reactor for pyrolysis. Inside the reactor, the material begins to degrade as soon as the degradation temperature is reached, and the volatiles created are passed to the condensing unit for cooling, and then the vapours are passed to the separator, which separates the vapours into gas and oil. The vapours formed in the reactor come into the water tank through the pipelines. The water sprinkler then sprinkles the water on the water tank containing the heated vapours to cool down the vapours. The gas collected in the separator passes to the gas filtration tank and is then stored in the gas storage tank to be further used as fuel in the LPG burner. Gases were also released at predetermined intervals to keep the pressure in the reactor system low. Using this method, the yield of oil was about 75% of the input, which was found to be very promising and economical. The process stated above was repeated for different types of plastic waste, and four types of solvents were prepared by the pyrolysis of different waste plastics, such as PE + PP, PP, HDPE + LDPE, and ABS. These solvents were used to dissolve the biomedical waste by maintaining a constant volume of 200 mL for each experiment.

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagram of the pyrolysis setup used for the pyrolytic solvent production using the solid plastic chairs.

2.2. Experimental process of mask dissolution

In the present study, an unused surgical mask was taken and cut into tiny pieces having a size of 5 mm, as shown in Fig. 4 . The rubber thread was removed from the mask. These pieces were mixed with the pyrolysis solvent oil and placed into a conical flask (Erlenmeyer flask) [29]. The conical flask was placed on the heating mantle for heating. The heating mantle was provided with jointless hand-knitted heating nets of glass yarn, capable of withstanding up to 400 °C, to maintain a better heat transfer contact area. A rubber cork was used to make the flask leak-proof, as shown in Fig. 5 . A thermometer (temperature range: 60 °C to 300 °C) was used to measure the instantaneous temperature of the solution filled in the flask and set, as shown in Fig. 5. A U-tube manometer was also used to measure the pressure difference in the flask while heating the solution. All the instruments were used in such a manner to avoid any kind of leakage or disturbance at the time of the experiments.

Fig. 4.

Shredded Surgical mask used in the present study.

Fig. 5.

Arrangement to heat the mixture of pyrolysis oil and plastic waste.

The mixture of mask and solvent filled in the conical flask was heated progressively by increasing the voltage supplied to the heating mantle, and the temperature and pressure were noted down after each increment. When the mask pieces were dissolved completely in the pyrolysis solvent oil, the heating was stopped, and the flask containing the solution of the dissolved mask was placed on a flat surface for cooling and visualising the precipitation of the dissolved mask. After visualising the precipitation for several hours, the dissolved mask was filtered from the pyrolysis solvent oil and dried to measure the mass of the precipitated mask. To estimate the capability of the solvent to dissolve the mask several times, the shredded and undissolved masks were mixed again into the solvent, which was left after filter-out the precipitation. It

Was repeated similarly to the previous step, and the dissolved mask was filtered and dried. This process was repeated several times for different solvents based on the source plastic and different heating rate.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Pyrolytic solvent

As mentioned in the previous section, the solvent oil was prepared using the pyrolysis process; indigenously, variations in the heat input, oil, and char output for different plastic waste sources are shown in Fig. 6 [30]. The effect of the catalyst is very significant on the heat input and oil output for each sample. For the PP plastic waste, a reduction in the heat input of about 44.2% was measured when about 16.7% catalyst was added to the plastic waste during the pyrolysis process [31]. After increasing the amount of catalyst (23.08%), the reduction in the heat input was found to be about 20.3%. The oil yield was also measured more by 3.05% for the 16.7% catalyst, compared to the without catalyst, and a reduction of 12.9% in the oil yield occurred for the 23.08% catalyst. The char production was also similar to the oil yield. A lower amount of catalyst was found to be efficient and economical, with a higher conversion rate of oil output and lesser heat input. A mixture of PP and PE (PP + PE) plastic waste was also fed in the pyrolysis process without and with a catalyst. In the case of only PP plastic, a reduction in the heat input was found with the addition of catalyst, but a reduction in the oil yield was found by the addition of catalyst in the PP + PE oil. Along with PP and PP + PE, other types of plastic wastes of ABS and HDPE + LDPE were also used to prepare the pyrolysis oil, and the same was used as the solvent to dissolve the biomedical plastic waste.

Fig. 6.

A plot relating the weight of plastic waste, input energy, output oil, and char with the different input plastic waste.

3.2. GC-MS of the pyrolytic solvent

For the identification of the unknown components of the prepared solvent, a sample of solvent extracted from the mixture of only PP + PE was tested in the GC-MS (make: SHIMADZU corporation, model: Shimadzu TQ8040). The temperature range for the experimentation was kept from 40°C to 270 °C with a rate of 8 °C increase after every 3.25 min. The sample was first filtered through filter paper and then diluted with acetone tenfold the sample's volume. The diluted sample was placed in the machine and was let to perform the analysis. Most of the carbon-heavy compounds (C > 20) came to light after the 22 min mark, where the overall time for the whole experiment was kept to 34 min.

The GC-MS composition of the pyrolytic solvent is shown in Table 3 . The table summarises the identification and distribution of the various compounds in the sample. It was observed from the test data that a high quantity of alkane and alkenes are present in the sample, and it has a higher concentration of aromatics mixtures. The derived solvent has a low number of heavier hydrocarbons (>C20) which suggests that the sample is wax-free liquid, while similar results were obtained in the literature [20]. A few oxygen-containing compounds were also observed in the derived sample, like Cyclohexane, 1,2,3,4,5,6-hexaethyl, Cyclooctane, 1-methyl-3-propyl, etc.

Table 3.

GC-MS of the solvent oil derived from a solid waste plastic chair at 270 °C.

| Peak | Name | Formula | Reaction Time | Area % | Height % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1-Pentene, 2-methyl- | C6H12 | 2.136 | 1.84 | 3.13 |

| 2 | n-Hexane | C6H14 | 2.198 | 0.22 | 0.4 |

| 3 | 2-Butene, 2,3-dimethyl- | C6H12 | 2.25 | 0.19 | 0.37 |

| 4 | 1-Pentene, 2,4-dimethyl- | C7H14 | 2.592 | 0.38 | 0.56 |

| 5 | 2,4-Dimethyl 1,4-pentadiene | C7H12 | 2.671 | 0.47 | 0.62 |

| 6 | 1-Heptene | C7H14 | 3.096 | 0.53 | 0.92 |

| 7 | Heptane | C7H16 | 3.212 | 0.4 | 0.69 |

| 8 | 2-Hexene, 3,5-dimethyl- | C8H16 | 4.129 | 0.39 | 0.46 |

| 9 | Heptane, 4-methyl- | C8H18O | 4.302 | 1.23 | 1.65 |

| 10 | 1-Octene | C8H16 | 4.759 | 0.49 | 0.72 |

| 11 | Octane | C8H18 | 4.935 | 0.47 | 0.66 |

| 12 | Cyclopentane, 1,1,3,4-tetramethyl-, cis- | C9H18 | 5.18 | 0.28 | 0.41 |

| 13 | 2-Hexene, 4,4,5-trimethyl- | C9H18 | 5.582 | 0.3 | 0.44 |

| 14 | Cyclohexane, 1,3,5-trimethyl- | C9H18 | 5.626 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| 15 | 2,4-Dimethyl-1-heptene | C9H18 | 5.771 | 8.41 | 11.29 |

| 16 | Cyclohexane, 1,3,5-trimethyl- | C9H18 | 6.14 | 0.81 | 1.13 |

| 17 | o-Xylene | C8H10 | 6.39 | 0.21 | 0.22 |

| 18 | Cyclopropane, 1,1-dimethyl-2-(2-methyl-1-p | C9H16 | 6.434 | 0.24 | 0.28 |

| 19 | 1-Undecene, 8-methyl- | C12H24 | 6.867 | 1.41 | 1.66 |

| 20 | Nonane | C9H20 | 7.053 | 0.43 | 0.54 |

| 21 | 1-Decene | C10H20 | 9.028 | 0.82 | 1.1 |

| 22 | Decane | C10H22 | 9.216 | 0.42 | 0.57 |

| 23 | Heptane, 2,5,5-trimethyl- | C10H22 | 9.367 | 0.31 | 0.43 |

| 24 | Heptane, 2,5,5-trimethyl- | C10H22 | 9.456 | 0.33 | 0.45 |

| 25 | 11-Methyldodecanol | C13H28O | 10.802 | 1.02 | 1.34 |

| 26 | 1-Undecene, 7-methyl- | C12H24 | 10.888 | 0.63 | 0.85 |

| 27 | 1-Undecene | C12H24 | 11.108 | 0.7 | 0.91 |

| 28 | Undecane | C11H24 | 11.283 | 0.48 | 0.63 |

| 29 | (2,4,6-Trimethylcyclohexyl) methanol | C10H20O | 12.213 | 0.28 | 0.39 |

| 30 | 3-Tetradecene, (Z)- | C14H28 | 13.065 | 0.63 | 0.85 |

| 31 | Dodecane | C12H26 | 13.226 | 0.52 | 0.67 |

| 32 | 1-Tridecene | C13H26 | 14.9 | 0.59 | 0.83 |

| 33 | 1-Decanol, 2-hexyl- | C16H34O | 15.062 | 2.23 | 2.6 |

| 34 | 11-Methyldodecanol | C13H28O | 15.214 | 0.68 | 0.77 |

| 35 | 11-Methyldodecanol | C13H28O | 15.361 | 1.36 | 1.69 |

| 36 | 1-Heptanol, 2,4-diethyl- | C11H24O | 15.825 | 0.2 | 0.27 |

| 37 | Cyclopentaneethanol, beta.,2,3-trimethyl- | C10H20O | 16.274 | 0.37 | 0.48 |

| 38 | 3-Hexadecene, (Z)- | C16H32 | 16.628 | 0.78 | 0.99 |

| 39 | Tetradecane | C14H30 | 16.763 | 0.61 | 0.76 |

| 40 | Cyclohexane, octadecyl- | C24H48 | 18.105 | 0.37 | 0.2 |

| 41 | 1-Pentadecene | C15H30 | 18.254 | 0.88 | 1.09 |

| 42 | Tetradecane | C14H30 | 18.377 | 0.81 | 0.87 |

| 43 | 1-Decanol, 2-hexyl- | C16H34O | 18.637 | 0.72 | 0.86 |

| 44 | 1-Decanol, 2-hexyl- | C16H34O | 18.788 | 0.29 | 0.3 |

| 45 | 1-Decanol, 2-hexyl- | C16H34O | 19.06 | 0.38 | 0.44 |

| 46 | 11-Methyldodecanol | C13H28O | 19.213 | 0.28 | 0.34 |

| 47 | (2,4,6-Trimethylcyclohexyl) methanol | C10H20O | 19.721 | 0.53 | 0.64 |

| 48 | 1-Heptadecene | C17H34 | 19.79 | 0.91 | 1.2 |

| 49 | Heptadecane | C17H36 | 19.902 | 0.85 | 1.03 |

| 50 | 1,19-Eicosadiene | C20H38 | 21.14 | 0.3 | 0.22 |

| 51 | 1-Heptadecene | C17H34 | 21.247 | 1.39 | 1.26 |

| 52 | Heptadecane | C17H36 | 21.35 | 1.36 | 1.43 |

| 53 | Disparlure | C19H38O | 21.48 | 0.85 | 0.37 |

| 54 | Cyclohexane, 1,2,3,4,5,6-hexaethyl- | C18H36 | 21.63 | 0.76 | 0.28 |

| 55 | Hexacosyl trifluoroacetate | C28H53F3O2 | 21.76 | 1.11 | 1.26 |

| 56 | 1-Decanol, 2-hexyl- | C16H34O | 22.156 | 0.88 | 0.79 |

| 57 | Cyclohexane, octadecyl- | C24H48 | 22.278 | 0.21 | 0.28 |

| 58 | 1-Dodecanol, 2-hexyl- | C18H38O | 22.346 | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| 59 | 1-Nonadecene | C19H38 | 22.631 | 1.46 | 1.36 |

| 60 | Heptadecane | C17H36 | 22.726 | 2.02 | 1.62 |

| 61 | Oleyl alcohol, trifluoroacetate | C20H35F3O2 | 23.861 | 0.25 | 0.29 |

| 62 | 1-Nonadecene | C19H38 | 23.948 | 1.18 | 1.37 |

| 63 | Heneicosane | C21H44 | 24.032 | 1.35 | 1.62 |

| 64 | Cyclohexane, octadecyl- | C24H48 | 24.13 | 0.31 | 0.15 |

| 65 | Tetratriacontyl heptafluorobutyrate | C38H69F7O2 | 24.555 | 0.85 | 0.98 |

| 66 | Hexatriacontyl trifluoroacetate | C38H73F3O2 | 24.888 | 0.29 | 0.35 |

| 67 | 1,19-Eicosadiene | C20H38 | 25.122 | 0.36 | 0.27 |

| 68 | 1-Nonadecene | C19H38 | 25.203 | 1.43 | 1.44 |

| 69 | Heneicosane | C21H44 | 25.282 | 1.63 | 1.86 |

| 70 | Cyclooctane, 1-methyl-3-propyl- | C12H24 | 25.46 | 0.71 | 0.91 |

| 71 | 1,37-Octatriacontadiene | C38H74 | 26.33 | 0.21 | 0.26 |

| 72 | 1-Nonadecene | C19H38 | 26.404 | 1.02 | 1.24 |

| 73 | Heneicosane | C21H44 | 26.476 | 1.53 | 1.88 |

| 74 | Cyclooctane, 1-methyl-3-propyl- | C12H24 | 26.847 | 0.2 | 0.23 |

| 75 | Hexatriacontyl trifluoroacetate | C38H73F3O2 | 27.084 | 0.63 | 0.79 |

| 76 | 1-Decanol, 2-hexyl- | C16H34O | 27.362 | 1.99 | 1.28 |

| 77 | Cyclohexane, 1,2,3,5-tetraisopropyl- | C18H36 | 27.4 | 2 | 1.15 |

| 78 | (E)-Dodec-2-enyl (E)-2-methylbut-2-enoate | C17H30O2 | 27.505 | 0.79 | 0.54 |

| 79 | 1-Nonadecene | C19H38 | 27.552 | 1.04 | 1.16 |

| 80 | Heneicosane | C21H44 | 27.618 | 1.63 | 1.91 |

| 81 | Cyclohexane, 1,2,3,5-tetraisopropyl- | C18H36 | 27.921 | 0.75 | 0.79 |

| 82 | 1-Nonadecene | C19H38 | 28.653 | 0.79 | 0.94 |

| 83 | Heneicosane | C21H44 | 28.712 | 1.57 | 1.82 |

| 84 | 1-Hexacosanol | C26H54O | 29.005 | 1.81 | 0.73 |

| 85 | Tetratetracontane | C44H90 | 29.162 | 6.33 | 2.66 |

| 86 | Cyclohexane, 1,2,3,5-tetraisopropyl- | C18H36 | 29.34 | 0.39 | 0.15 |

| 87 | Hexatriacontyl trifluoroacetate | C38H73F3O2 | 29.392 | 0.43 | 0.55 |

| 88 | Behenic alcohol | C22H46O | 29.71 | 0.59 | 0.74 |

| 89 | Heneicosane | C21H44 | 29.764 | 1.57 | 1.72 |

| 90 | Cyclohexane, 1,2,3,5-tetraisopropyl- | C18H36 | 30.171 | 0.49 | 0.63 |

| 91 | 1-Heptacosanol | C27H56O | 30.725 | 0.53 | 0.65 |

| 92 | Heneicosane | C21H44 | 30.775 | 1.75 | 1.79 |

| 93 | Octatriacontyl trifluoroacetate | C40H77F3O2 | 31.565 | 0.53 | 0.48 |

| 94 | Tetrapentacontane, 1,54-dibromo- | C54H108Br2 | 31.661 | 2.74 | 1.08 |

| 95 | 2-Methylhexacosane | C27H56 | 31.843 | 3.75 | 2.06 |

| 96 | Tetracosane | C24H50 | 31.963 | 3.65 | 1.61 |

| 97 | Cyclohexane, 1,2,3,5-tetraisopropyl- | C18H36 | 32.458 | 0.46 | 0.41 |

| 98 | 1-Hexacosanol | C26H54O | 33.025 | 0.26 | 0.2 |

| 99 | Eicosane | C20H42 | 33.093 | 0.93 | 0.74 |

| 100 | Cyclohexane, 1,2,3,5-tetraisopropyl- | C18H36 | 33.884 | 2.52 | 1.04 |

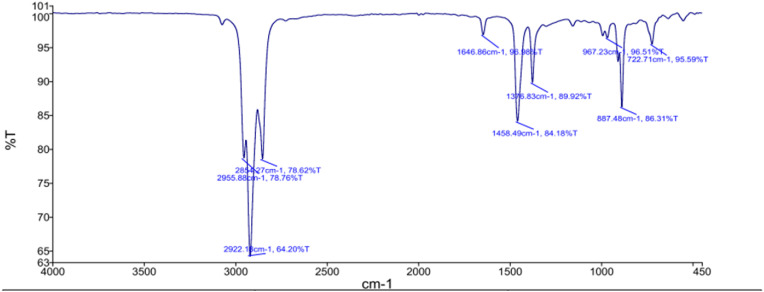

3.3. FTIR analysis of the derived solvent oil

Both GC-MS and the FTIR spectra of solvent samples based on PP + PE plastic were recorded between 4,000 and 400 cm−1 with a resolution of 2 cm−1 wavenumbers using a spectrophotometer (make: PerkinElmer, model: Spectrum-65) to determine the main functional groups. This technique classifies the chemical bonds in a molecule by producing an infrared absorption spectrum result for several functional groups present in the solvent oil. It is to be noted that when the solvent sample is exposed to infrared radiation, the chemical bonds within the solvent contract, stretch, and absorb these radiations in a specific range of wavelength independent of the structure of the rest of the molecules. The FTIR spectrum obtained for solvent oil is shown in Fig. 7 .

Fig. 7.

FTIR result obtained of the solvent oil.

3.4. Analysis of facemask

It is important to understand the structure of the 3-ply facemask before its treatment. Therefore, Scanning Electron Microscopy (Make: Hitachi, Model: S–3400 N) was used to capture the SEM images of the facemask before the shredding or treatment, as shown in Fig. 8 . The 3-ply surgical mask is made up of 3 different layers of fabric material made from long and staple fibres, bonded together [32], as depicted in Fig. 8 for all three layers. The function of the outermost layer is to repel the fluids, such as many salivary droplets from the other person. Similar to trapping many salivary droplets from the user and improving the comfort of the user by absorbing the moisture from exhaling air, the innermost layer of the facemask is made of absorbent material. A filter is used as the middle piece to prevent the transmission of particles or viruses, or pathogens above a certain size from another person to the user. Large flat areas in the inner and outer layers (Fig. 8 (a-b)) are the bonds to hold the long fibres together. The diameter of these fibres varies in the range of 23 μm–30 μm in the inner and outer layers, while the diameter of fibres present in the filter section is approximately 40 μm. The space between the two nearby fibres is found to be less than the diameter of the fibres, which may suggest that pathogens or viruses having a size smaller than 40 μm are also restricted by the filter.

Fig. 8.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the inner, middle (filter), and outer layer of the facemask before the treatment before the shredding.

3.5. Effect of heating rate of the facemask dissolution

The shredded facemask was dipped into the solvent prepared through pyrolysis solvent oil, and the experimental process of mask dissolution was followed for different types of solvents.

3.5.1. PE + PP solvent

About eight samples of shredded facemasks were treated in the solvent at different heating rates, as shown in Fig. 9 . The heating of the mixture of shredded facemask and solvent was continued till the full dissolution of the facemask into the solvent. Out of 8, 7 samples showed almost similar behaviour, except sample 6. The dissolution of the facemask was achieved in the temperature range from 108 to 150 °C within 70 min, except for sample 6. The slope of the curve represents the heating rate; the larger the slope, the faster the heating or vice-versa. For samples 5–8, descending heating rate is given as samples 5–8 – 7–6. Once the dissolution was achieved, the mixture was kept for cooling, and precipitation of the dissolved facemask occurred, as shown in Fig. 10 . Heating was done up to 130 °C for sample 7, which was minimum as compared to the remaining three. The heating of the mixture at this lower temperature was not sufficient to dissolute the facemask completely, which further delayed the precipitation. A clear supernate was observed for faster heating in the case of sample 5 with complete precipitation of the facemask residues. But at the lower peak temperature of 130 °C, the cloudy supernate was experienced for sample 7. The visual observations are listed in Table 4 , which shows a clear supernate for higher peak temperature, irrespective of heating rate.

Fig. 9.

Variation in the temperature with time for eight different samples of a facemask in the solvent extracted from the PP + PE oil.

Fig. 10.

Precipitation of dissolved facemask for samples 5–8.

Table 4.

Observational findings from the treatment of BMW in PP + PE solvent.

| S. No. | Sample No. | The temperature of dissolution initiation | Peak Temperature | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1–4 | 110–115 | 108,115,120 | Mask dissolve in oil but does not settle down after condensation |

| 2 | 5 | 110–115 | 140 | Clear supernate |

| 3 | 6 | 110–115 | 160 | Clear supernate, the thickness of precipitate was less than sample 5 |

| 4 | 7 | 110–115 | 130 | Cloudy supernate |

| 5 | 8 | 110–115 | 150 | In clear supernate, the thickness of the precipitate was less than sample 5 but more than 6. |

3.5.2. PP solvent

Similar to the PE + PP solvent, the oil extracted from only PP plastic was also used as the solvent for the BMW treatment. The heating rate of the mixture consisting of PP solvent and facemask for four different samples is depicted in Fig. 11 , where the heating rate in descending order is as follows: 17–16 – 10–9. The observations experienced visually are listed in Table 5 and also shown in Fig. 12 . A clear supernate is depicted for the lower heating rate but at a higher peak temperature, while a cloudy supernate was visualised for the higher heating rate and lower peak temperature. The precipitation of facemask residue was slower in the solvent from PP as compared to the PE + PP oil at the same peak temperature.

Fig. 11.

Variation in the temperature with time for four different samples of a facemask in the PP solvent.

Table 5.

Observational findings from the treatment of BMW in PP solvent.

| S. No. | Sample No. | The temperature of dissolution initiation | Peak Temperature | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 9 | 120–125 | 150 | Clear supernate |

| 7 | 10 | 120–125 | 130 | Mask dissolves in oil but does not settle down after condensation |

| 8 | 16 | above 120 | 140 | Clear supernate |

| 9 | 17 | 120 | 120 | Dissolution occurred in the solvent but did not settle down after condensation |

Fig. 12.

Precipitation of dissolved facemask for samples 9 and 10 in ascending order of heating rate.

3.5.3. ABS solvent

As stated earlier that the pyrolysis oil prepared using ABS plastic was also used in the present study as a solvent for the plastic waste [33]. The heating rate in descending order is given as 19–18 – 11, as shown in Fig. 13 , using the same heating assembly. The observations experienced visually are listed in Table 6 and also shown in Fig. 14 , which shows a cloggy supernate for all three samples. The precipitation of the dissolved mask was also not occurred, even though the sample was kept for a long period without shaking. The use of solvent occurred from the ABS is not suitable for the dissolution of facemasks.

Fig. 13.

A temperature-time plot of the heating process for ABS solvent.

Table 6.

Observational findings from the treatment of BMW in ABS solvent.

| S. No. | Sample No. | The temperature of dissolution initiation | Peak Temperature | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 11 | 120 | 130 | Dissolve in oil but do not settle down after condensation |

| 11 | 18 | above 110 | 140 | |

| 12 | 19 | above 110 | 120 |

Fig. 14.

Solutions of ABS solvent after the dissolution of plastic mask for samples (a) 11, (b) 18 (shown as a sample – 5), and (c) 19 (shown as a sample – 6).

3.5.4. HDPE + LDPE solvent

The dissolution of a shredded facemask was also examined in the solvent prepared from the HDPE + LDPE plastic. The facemask was treated in four samples at different heating rates and peak temperatures, as shown in Fig. 15 . The heating rates in descending order were followed as 13–12 – 15–14, while the peak temperature ranged from 130 to 150 °C. The visual observations found for HDPE + LDPE solvent were similar to the PP oil, shown in Fig. 16 . A clear supernate did not occur for any heating rate; instead, a slightly cloudy supernate was experienced at a peak temperature of 140 °C (sample – 12), while a complete cloudy supernate was observed at 150 °C (sample – 14). The former sample was heated at a faster rate than the later sample, which may affect the occurrence of clear supernate. The visual observations for all four samples in HDPE + LDPE solvent are listed in Table 7 .

Fig. 15.

A temperature-time plot of the heating process for the LDPE + HDPE solvent.

Fig. 16.

Solutions of LDPE + HDPE solvent after the dissolution of plastic mask for samples 12 and 13.

Table 7.

Observational findings from the treatment of BMW in LDPE + HDPE solvent.

| S. No. | Sample No. | The temperature of dissolution initiation | Peak Temperature | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 12 | 115–120 | 140 | Slightly cloudy supernate |

| 14 | 13 | 115 | 130 | dissolve in oil but do not settle down |

| 15 | 14 | 115, speed up after 130 | 150 | |

| 16 | 15 | 115 | 130 |

3.6. Analysis of precipitated residue of facemask

The precipitate of the facemask residue was separated from the solvent using the filter and dried to convert into powder form, as shown in Fig. 17 . After removing this precipitate from the solvent, another sample of the mask was dissolved in the same solvent to investigate the ability of dissolution of the same solvent for the repeated cycle. The precipitate was filtered and dried to make it into powder form. These two samples of dry powder were analysed in the form of SEM images, as shown in Fig. 18 , at different magnification levels. In both samples, no significant difference was observed, indicating no impact on the dissolution of a facemask in the solvent in more than one cycle.

Fig. 17.

Powder form of dried precipitate of the dissolved facemask for sample 8 (PP + PE oil).

Fig. 18.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the dry residue of a dissolved facemask in the solvent of (PE + PP) after the first (left side) and second (right side) cycle.

4. Global potential

The production of plastic [34] was about 2 Mt/y in 1950, which increased almost 200 times in 2015, up to 381 Mt/y [35]. About 7800 Mt have been produced in total till 2015, while the 50% of the total was produced only in the last 13 years. This exponential growth in plastic production resulted in waste generation, about 5,800 Mt of plastic waste, by the end of 2015 in total. By updating the data [36], it is estimated that about 273.15 Mt of plastic waste would be produced by April 2022, where China and the USA are the largest producers of plastic waste among the 166 countries, as shown in Fig. 19 .

Fig. 19.

Plastic production by countries in 2022 (in mt) [36].

The produced plastic waste is disposed of in three ways, incineration, recycling, and whatever is left being discarded [37]. The shares of plastic waste disposal globally are depicted in Fig. 20 , where the fraction of recycling and incineration increased with time while discarding was reduced. In 2015, 19.5%, 25.5%, and 55% of the total waste generated were recycled (74.3 Mt), incinerated (97.2 Mt), and discarded (209.5 Mt) [35]. The discarded plastic waste enters the oceans and affects the marine ecosystem, and it is of utmost requirement to deduce the discarded plastic waste into the incineration or recycling process. Based on the studies conducted on pyrolysis [40] in the literature and with technological advancement, plastic waste should be treated in a controlled environment with higher conversion efficiency into the products such as fuel or solvent to minimise the emissions.

Fig. 20.

Trends of estimated shares of global plastic waste disposal [35].

The novel approach presented in the current work is capable of solving the problem of plastic waste and BMW by converting the former into solvent and treating of latter by dissolving it into the solvent simultaneously. As the production of plastic waste and BMW is growing exponentially in the current scenario, the presented approach has global potential and sustainability for plastic waste and BMW management [38] and to reduce the pandemic's negative impact [39].

5. Conclusions

In the literature, to disinfect the COVID-19 virus from the BMW, it was suggested to heat it at a temperature of more than 60–70 °C for almost 30 min. By accounting for this guideline, the COVID-19-infected BMW (facemask) was heated up to a temperature of 110 °C or more in a solvent. In the present work, the liquid oils were prepared from the thermal–catalytic pyrolysis of different types of plastics, such as PP + PE, PP, ABS, and HDPE + LDPE, using a novel catalyst. The prepared oils were used as the solvents for the treatment of BMW. The mixture of solvent and shredded facemask was heated at different heating rates and at different peak temperatures to investigate the effect of heat on the dissolution of the facemask. Based on the experimental observations, the following results were found:

-

i.

Out of four different solvents, disposal of a facemask in the PP + PE solvent was better followed by the PP solvent, compared to other solvents.

-

ii.

ABS and HDPE + LDPE solvents were found not suitable for the treatment of the facemask.

-

ii.

The higher peak temperature is a dominant factor in the disposal of the facemask, as compared to the heating rate for PP + PE and PP solvent.

-

iv.

No significant difference in the precipitate of facemask residue was observed when the same solvent was used again for the dissolution of a facemask in more than one cycle.

-

v.

The possible cause of the disposal of the facemask in the PP + PE and PP solvent is the similar material of the facemask and solvent, i.e., PP and PE.

To counter the BMW generated due to the COVID – 19 pandemic, the treatment method used in the present work can be used as a primary approach due to two benefits. First, it is a controlled process to treat the BMW made of plastic polymers, and it requires the solvent prepared from the waste plastic, resulting in the management of waste plastics. In the present work, an investigation of gases released during the heating of the mixture is not conducted, for which a detailed parametric study can be held in the future.

Credit author statement

Rajesh Choudhary: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Abhishek Mukhija: Methodology, Writing – original draft. Subhash Sharma: Methodology, Writing – original draft. Rohitash Choudhary: Writing – review & editing. Ami Chand: Writing – review & editing. Ashok K. Dewangan: Writing – review & editing. Gajendra Kumar Gaurav: Writing – review & editing. Jiří Jaromír Klemeš: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Proof reading, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr V.K. Agarwal, Chairman, and Dr Manju Agarwal, Managing Director, Group of Institute of Engineering & Technology, Alwar (Rajasthan), for providing the financial support and facilities to conduct the research work. This research was also supported by a project, “Sustainable Process Integration Laboratory - SPIL”, project No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/15_003/0000456 funded by EU as “CZ Operational Programme Research, Development and Education”, Priority 1: Strengthening capacity for quality research and the research was also supported by the GACR (Grant Agency of the Czech Republic) under No. 21–45726 L and from the Slovenian Research Agency for project No. J7-3149.

Data availability

The authors do not have permission to share data.

References

- 1.Hantoko D., Li X., Pariatamby A., Yoshikawa K., Horttanainen M., Yan M. Challenges and practices on waste management and disposal during COVID-19 pandemic. J Environ Manag. 2021;286 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nzediegwu C., Chang S.X. Improper solid waste management increases potential for COVID-19 spread in developing countries. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Commission on Population under Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, India . July, 2020. Population projections for India and states 2011 – 2036, report of the technical group on population projections.https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/Population%20Projection%20Report%202011-2036%20-%20upload_compressed_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allied Market Research . 2021. Indian surgical masks market.https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/surgical-mask-market [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health . 2018. NIOSH infographic for the difference between surgical masks and N95 face pieces.https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/pdfs/UnderstandDifferenceInfographic-508.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prata J.C., Silva A.L.P., Walker T.R., Duarte A.C., Rocha-Santos T. COVID-19 pandemic repercussions on the use and management of plastics. Environ Sci Technol. 2020;54:7760–7765. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasan N.A., Heal R.D., Bashar A., Haque M.M. Face masks: protecting the wearer but neglecting the aquatic environment? - a perspective from Bangladesh. Environmental Challenges. 2021;4 doi: 10.1016/j.envc.2021.100126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen R., Zhang D., Xu X., Yuan Y. Pyrolysis characteristics, kinetics, thermodynamics and volatile products of waste medical surgical mask rope by thermogravimetry and online thermogravimetry-Fourier transform infrared-mass spectrometry analysis. Fuel. 2021;295 doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.120632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Kelly E., Arora A., Pirog S., Ward J., Clarkson P.J. Comparing the fit of N95, KN95, surgical, and cloth face masks and assessing the accuracy of fit checking. PLoS One. 2021;16(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenneth K.W.L., Joussen A.M., Joseph K.C.K., Steel D.H.W. FFP3, FFP2, N95, surgical masks and respirators: what should we be wearing for ophthalmic surgery in the COVID-19 pandemic? Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258(8):1587–1589. doi: 10.1007/s00417-020-04751-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polypropylene: properties, processing, and applications. 2021. https://matmatch.com/learn/material/polypropylene [Google Scholar]

- 12.Low density Polyethylene (LDPE) 2021. https://matmatch.com/materials/mbas004-low-density-polyethylene-ldpe [Google Scholar]

- 13.High density Polyethylene (HDPE) 2021. https://matmatch.com/materials/mbas008- high-density-polyethylene-hdpe [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emmanuel J., Pieper U., Rushbrook P., Ruth S., William T., Susan W. Safe management of wastes from health care activities. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(2):171. doi: 10.1590/S0042-96862001000200013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thiel M., Veer D., Espinoza-Fuenzalida N.L., Espinoza C., Gallardo C., Hinojosa I.A., Kiessling T., Rojas J., Sanchez A., Sotomayor F., Vasquez N., Villablanca R. COVID lessons from the global south – face masks invading tourist beaches and recommendations for the outdoor seasons. Sci Total Environ. 2021;786 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bondaroff T.P., Cooke S. The impact of COVID-19 on marine plastic pollution. Ocean Asia. 2020 https://oceansasia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Marine-Plastic-Pollution-FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abraham J.P., Plourde B.D., Cheng L. Using heat to kill SARS-CoV-2. Rev Med Virol. 2020;30(5):8–10. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Messerle V.E., Mosse A.L., Ustimenko A.B. Processing of biomedical waste in plasma gasifier. Waste Manag. 2018;79:791–799. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2018.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ilyas S., Srivastava R.R., Kim H. Disinfect. ion technology and strategies for COVID-19 hospital and bio-medical waste management. Sci Total Environ. 2020;749 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar A., Sagdeo A., Sagdeo P.R. Possibility of using ultraviolet radiation for disinfecting the novel COVID-19. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2021;34:2020–2021. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2021.102234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maher O.A., Kamal S.A., Newir A., Persson K.M. Utilisation of greenhouse effect for the treatment of COVID-19 contaminated disposable waste - a simple technology for developing countries. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2021;232:17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2021.113690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neto A.G., de Carvalho J.N., Costa da Fonseca J.A., da Costa Carvalho A.M., de Melo Vasconcelos Castro M.M. Microwave medical waste disinfection: a procedure to monitor treatment quality. 2003:63–65. doi: 10.1109/imoc.1999.867043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Debnath B., Ghosh S., Dutta N. Resource resurgence from COVID-19 waste via pyrolysis: a circular economy approach. Circular Economy and Sustainability. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s43615-021-00104-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purnomo C.W., Kurniawan W., Aziz M. Technological review on thermochemical conversion of COVID-19-related medical wastes. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2021;167 doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Central Pollution Control Board . vol. 4. 2020. https://cpcb.nic.in/uploads/Projects/Bio-Medical-Waste/BMW-GUIDELINES-COVID_1.pdf (Guidelines for handling, treatment, and disposal of waste generated during treatment/diagnosis/quarantine of COVID-19 patients). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tripathi A., Tyagi V.K., Vivekanand V., Bose P., Suthar S. Challenges, opportunities and progress in solid waste management during COVID-19 pandemic. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.cscee.2020.100060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fivga A., Dimitriou I. Pyrolysis of plastic waste for production of heavy fuel substitute: a techno-economic assessment. Energy. 2018;149:865–874. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2018.02.094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miranda M., Cabrita I., Pinto F., Gulyurtlu I. Mixtures of rubber tyre and plastic wastes pyrolysis: a kinetic study. Energy. 2018;58:270–282. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2013.06.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leonas K.K., Jones C.R. The relationship of fabric properties and bacterial filtration efficiency for selected surgical face mask. J Text Appar Technol Manag. 2003;3(2):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S., Alejandro D.A.R., Kim H., Kim J.Y., Lee Y.R., Nabgan W., et al. Experimental investigation of plastic waste pyrolysis fuel and diesel blends combustion and its flue gas emission analysis in a 5 kW heater. Energy. 2022;247 doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2022.123408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park K.B., Choi M.J., Chae D.Y., Jung J., Kim J.S. Separate two-step and continuous two-stage pyrolysis of a waste plastic mixture to produce a chlorine-depleted oil. Energy. 2022;244(A) doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2021.122583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chua M.H., Cheng W., Goh S.S., Kong J., Li B., Lim J.Y.C., et al. Face masks in the New COVID-19 normal: materials. Testing, and Perspectives. 2020 doi: 10.34133/2020/7286735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahari W.A.W., Chong C.T., Cheng C.K., Lee C.L., Hendrata K., Yek P.N.Y., et al. Production of value-added liquid fuel via microwave co-pyrolysis of used frying oil and plastic waste. Energy. 2018;162:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2018.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klemeš J.J., Fan Y.V., Tan R.R., Jiang P. Minimising the present and future plastic waste, energy and environmental footprints related to COVID-19. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2020;127 doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2020.109883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geyer R., Jambeck J.R., Law K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci Adv. 2017;3 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1700782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ritchie H., Roser M. 2022. Plastic pollution.https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klemeš J.J., Fan Y.V., Jiang P. Plastics: friends or foes? The circularity and plastic waste footprint. Energy Sources, Part A Recovery, Util Environ Eff. 2020;43(13):1549–1565. doi: 10.1080/15567036.2020.1801906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimmermann K. Microwave as an emerging technology for the treatment of biohazardous waste: a mini-review. Waste Manag Res. 2017;35(5):471–479. doi: 10.1177/0734242X16684385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang P., Klemeš J.J., Fan Y.V., Fu X., Tan R.R., You S., Foley A.M. Energy, environmental, economic and social equity (4E) pressures of COVID-19 vaccination mismanagement: a global perspective. Energy. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2021.121315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaurav Gajendra, Mehmood Tariq, Cheng Liu, Klemeš Jiří Jaromír, Shrivastava Devesh Kumar. Water hyacinth as a biomass: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2020;277 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.