Abstract

Background:

This memory-clinic study joins efforts to study earliest clinical signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: subjective reports and objective neuropsychological test performance.

Objective:

The memory-clinic denoted two clinical “grey zones”: 1) subjective cognitive decline (SCD; n = 107) with normal objective test scores, and 2) isolated low test scores (ILTS; n = 74) without subjective complaints to observe risk for future decline.

Methods:

Initial and annual follow-up clinical research evaluations and consensus diagnosis were used to evaluate baseline characteristics and clinical progression over 2.7 years, compared to normal controls (NC; n = 117).

Results:

The ILTS group was on average older than the NC and SCD groups. They had a higher proportion of people identifying as belonging to a minoritized racial group. The SCD group had significantly more years of education than the ILTS group. Both ILTS and SCD groups had increased risk of progression to mild cognitive impairment. Older age, minoritized racial identity, and baseline cognitive classification were risk factors for progression.

Conclusion:

The two baseline risk groups look different from each other, especially with respect to demographic correlates, but both groups predict faster progression than controls, over and above demographic differences. Varied presentations of early risk are important to recognize and may advance cognitive health equity in aging.

Keywords: Cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, neurocognitive tests, risk factors

INTRODUCTION

In past decades, spurred by increasing dementia burden on individuals and societies, research efforts have focused increasingly on characterizing the earliest clinical signs and symptoms predicting dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s disease [1]. Although primary care providers (PCPs) deliver most of the care to older adults at greatest risk for cognitive decline, diagnosis of cognitive syndromes, including mild cognitive impairment (MCI), are most common in specialty settings [2]. This relies on both subjective reports of cognitive change and objective neuropsychological measures [3–5]. Subjective cognitive decline (SCD), defined as self-perceived cognitive changes in the context of normal neuropsychological assessment, has been a focus of research with consensus recommendations [5–7]. However, the converse putative risk state—low neuropsychological test performance in isolation (without subjective cognitive complaints)—is less frequently studied or observed [2, 8]. Several studies from observational research cohorts have investigated isolated (or ‘subtle’) objectively measured cognitive impairment, finding baseline functional MRI differences in the brain [9]; increased progression to MCI or dementia [10–12]; and increased amyloid-β accumulation and cortical thinning over time [10].

This study sought to investigate two classifications of putative risk for MCI, compared to healthy controls, in an academic memory clinic setting: 1) SCD with normal objective test scores, and 2) lower than expected test scores without subjective complaints (isolated low test scores; ILTS). The first study objective was to evaluate demographic and risk factor differences between baseline groups, and the second was to examine group differences in clinical progression to MCI or dementia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Participants were enrolled in the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) in accordance with procedures approved by the Institutional Review Board. As an academic memory disorders research center funded by the National Institute on Aging, one of currently 33 ADRCs in the U.S., it is also a research registry. People apply to participate for two broad reasons: clinical evaluation or participation in research (or both). Participants may be self-referred, physician-referred, or respond to community outreach efforts either because of concern about possible cognitive decline or as healthy controls. These include targeted recruitment events in under-represented group communities, social/professional contacts, online and print advertisements, and occasional local media features. The present cohort was not systematically enriched other than prioritizing enrollment of applicants from under-represented groups, those likely to participate further in research protocols, and those on the milder end of the cognitive impairment spectrum.

This study analyzed longitudinal data beginning July 1, 2009, when the center implemented the diagnostic category ‘low cognitive test performance without subjective complaints,’ through December 12, 2019. Center inclusion criteria were English-speaking fluency, minimum 7 years of education, adequate vision and hearing to complete neuropsychological tests, and a reliable informant. Lifetime history of serious psychiatric illness, age <60 without memory complaints, or recent health conditions or treatments that could affect neuropsychological performance (e.g., electroconvulsive therapy, alcohol or substance use disorder) or life expectancy (some cancers) were excluded. 298 participants satisfied these criteria and did not meet criteria for MCI or dementia at initial evaluation (see below, ‘Evaluation and Diagnosis’).

Evaluation and diagnosis

Initial evaluation included clinical interviews with participant and informant, neuropsychological testing, self-reported race/ethnicity, health history, family history, physical and neurological exams. The Clinical Dementia Rating scale was administered [13]. An interdisciplinary diagnostic consensus panel reviewed available clinical data, including MRI of the brain. The diagnostic process was clinical in nature, not algorithmic; the consensus conference process included consideration of all sources of information, including motivation for evaluation by the ADRC. Presence of clinically significant cognitive complaints was generally supported by concern for memory/cognition as motivation for seeking evaluation by the participant and/or informant. A Clinical Dementia Rating global score of 0.5 was typical for this determination.

The neuropsychological test norms utilized in this study were primarily derived from healthy control participants of the center at their baseline visit, but from an earlier time period relative to the current study. For most tests, the norms were adjusted by two broad age-categories: 75 and younger, and 76 and older. Mild impairment/lower-than-expected test scores on neuropsychological evaluation were both considered to be below −1.0 standard deviation (SD) from age-adjusted normative means, while taking account for educational/occupational background. The SCD group was defined as having subjective complaints with normal cognitive test performance [6], with no more than 1 low score within a domain or 2 low scores across domains. The ILTS group was defined as lower-than-expected test scores, generally, with at least 3 scores below −1.0 SD from age-adjusted normative means, without subjective cognitive complaints (including from informants). Normal controls (NC) had neither low neuropsychological test performance, nor clinically significant cognitive complaints. Both ILTS and NC participants were generally motivated to come to the ADRC primarily to volunteer for research.

APOE genotyping was performed according to previously reported methods [14].

Participants were followed annually with the same evaluation and diagnostic procedures. MCI and dementia diagnoses followed 2011 NIA-AA criteria [3, 15]. MCI was diagnosed when there was participant or informant concern (typically Clinical Dementia Rating of 0.5) or other evidence for change in cognitive abilities (e.g., decline in test scores over repeated assessments); mildly impaired neuropsychological test scores (below −1.0 SD) in at least one cognitive domain (≥2 tests within domain or 3 tests across domains); and independence in daily life [3]. MCI was further subtyped as amnestic, non-amnestic, single domain, and multi-domain [16]. Dementia was diagnosed as follows: cognitive impairment interferes with daily functioning; represents a decline from previous functioning; is not explained by delirium or major psychiatric disorder; and impairment is in at least two cognitive or behavioral domains.

Neuropsychological testing

The neuropsychological battery assessed memory, attention/concentration, visuo-construction, language, and executive function abilities. Tests were components of the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) Uniform Data Set Version 2 [17] and, starting March 2015, Version 3 [18]. Supplemental tests included a word list learning test [19]; modified Block Design [20, 21]; Stroop color and word test [22]; 15- point scoring of clock drawing [23]; and letter fluency trials [24]. Prior to implementation of NACC Uniform Data Set Version 3 the battery also included a modified Rey-Osterrieth Figure [25] and the Boston Naming Test [26].

Analysis

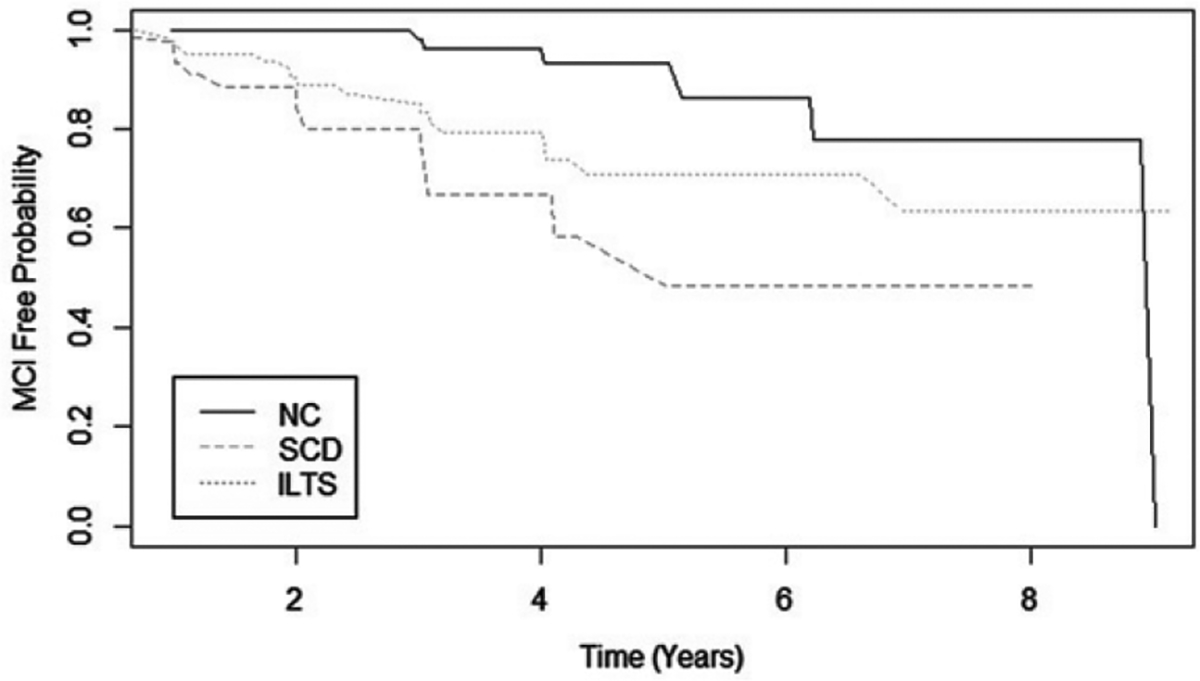

R 3.6.0 was used to analyze study data. All p-values reported are two-tailed. Due to non-normal distributions, Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance was used to compare groups at baseline, followed by Dunn-Bonferroni pairwise comparisons. For categorical variables the Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests were adopted for baseline group comparisons followed by pairwise comparisons. Self-reported race/ethnicity other than white was coded as a minoritized racial group. A Bonferroni correction for multiple pair-wise comparisons was applied by comparing p-values to a 0.05/3 significance level [27]. The most recent visit was used to calculate duration of follow-up time. The visit date of first occurrence of MCI or dementia diagnosis (without previous MCI diagnosis) was used to calculate time to diagnostic progression. Kaplan-Meier curves [28] were used to depict the probability of progressing to MCI/dementia over time. The two-sided log-rank test was used to compare the three MCI trajectories. Cox proportional hazards models were further used to compare the diagnosis groups while adjusting for risk factors including age, racial identity, education, sex, family history of dementia, and APOE ε4 status. The model fitting was evaluated by graphic checks based on estimated cumulative hazards and Cox-Snell residuals.

Sensitivity and post-hoc analyses included a) evaluating the stability of MCI diagnosis over subsequent follow-up visits; b) running the Cox proportional hazards model in white participants only; and c) and running the model with a combined SCD and ILTS group.

RESULTS

Of the n = 298 participants, n = 117 were classified as NC, n = 107 as SCD, and n = 74 as ILTS at baseline (Table 1). The ILTS group was on average older than the NC (p < 0.01) and SCD groups (p < 0.01). They had a higher proportion of people identifying as belonging to a minoritized racial group (ps < 0.01), including ‘Black or African-American’ (n = 57; 19% of total sample), ‘Asian’ (n = 3; 1%), ‘Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander’ (n = 1; 0.3%), and ‘Other’ (n = 1; 0.3%). The ILTS group had significantly fewer years of education than the SCD group (p < 0.01). All other pairwise comparisons did not show significant differences. Effect sizes were generally small to moderate except for minoritized racial group with a relatively large effect size [29] (https://imaging.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/statswiki/FAQ/effectSize).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by risk group

| NC N=117 Mean (SD) |

SCD N = 107 Mean (SD) |

ILTS N = 74 Mean (SD) |

Pairwise Comparison Adjusted p-values |

Test | p | Effect Size* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Age (y) | 65.3 (12.9) | 66.4 (7.2) | 71.3 (7.2) | NC versus SCD | 0.49 | Kruskal H (2) = 18.7 | <0.001 | 0.06 |

| NC versus ILTS | <0.01 | |||||||

| SCD versus ILTS | <0.01 | |||||||

| Education (y) | 16.3 (2.4) | 16.7 (2.5) | 15.4 (2.6) | NC versus SCD | 0.14 | Kruskal H (2) = 10.9 | <0.01 | 0.03 |

| NC versus ILTS | 0.04 | |||||||

| SCD versus ILTS | <0.01 | |||||||

| Females, N (%) | 89 (83.2%) | 69 (64.5%) | 47 (63.5%) | NC versus SCD | 0.06 | χ2 (2) = 4.8 | 0.09 | 0.12 |

| NC versus ILTS | 0.06 | |||||||

| SCD versus ILTS | 0.89 | |||||||

| Minoritized Racial | 22 (18.8%) | 7 (6.5%) | 33 (44.6%) | NC versus SCD | <0.01 | χ2 (2) = 38.8 | <0.001 | 0.36 |

| Identity, N (%) | NC versus ILTS | <0.001 | ||||||

| SCD versus ILTS | <0.001 | |||||||

| Family History | 64 (54.7%) | 62 (57.9%) | 39 (52.7%) | NC versus SCD | 0.63 | χ2 (2) = 0.52 | 0.77 | 0.04 |

| MCI/Dementia, N (%) | NC versus ILTS | 0.79 | ||||||

| SCD versus ILTS | 0.49 | |||||||

| APOE ε4, N (%) | 33 (28.2%) | 35 (32.7%) | 16(21.6%) | NC versus SCD | 0.46 | χ2 (2) = 2.65 | 0.27 | 0.09 |

| NC versus ILTS | 0.31 | |||||||

| SCD versus ILTS | 0.10 | |||||||

| Time Observed (y) | 2.8 (2.4) | 3.0 (2.6) | 2.0 (2.1) | NC versus SCD | 0.59 | Kruskal H (2) = 8.6 | 0.001 | 0.02 |

| NC versus ILTS | 0.02 | |||||||

| SCD versus ILTS | <0.01 | |||||||

η2 for continuous data; Cramer’s V for categorical data. NC, normal controls; SCD, subjective cognitive decline; ILTS, isolated low test scores.

Participants were followed annually to a maximum 9.3 years; however, 83 participants did not return for follow-up, and thus are not included in the longitudinal analyses. Participants without follow-up were significantly younger (mean 65.7 versus 68.0 years) and had a higher proportion identifying as a minoritized racial group (34.9% versus 15.3%). There were no differences in education, proportion of women, family history of MCI/dementia, or APOE ε4 allele. The proportions of participants not returning for follow-up were 0.26, 0.23, and 0.36 in the NC, SCD, and ILTS groups, respectively, which did not differ between groups (p = 0.14). The mean (SD) follow-up durations were 2.8 (2.4), 3.0 (2.6), and 2.0 (2.1) years for the NC, SCD, and ILTS groups, respectively, with significant difference among groups (Table 1). During the time observed, participants progressed as follows: In the NC group, 4 (3%) progressed to amnestic MCI, 1 (1%) to non-amnestic MCI, and 1 (1%) to dementia. In the SCD group, 14 (13%) progressed to amnestic and 3 (3%) to non-amnestic MCI. In the ILTS group, 10 (14%) progressed to amnestic and 3 (4%) to non-amnestic MCI.

As shown in Fig. 1, the ILTS group progressed to MCI the fastest, followed by the SCD and then NC groups. The log-rank test indicated significant differences in MCI progression probabilities between the NC and SCD groups (Z12 = 2.47, p = 0.01), and significant differences between NC and ILTS groups (Z13 = 4.18 and p < 0.001). However, the SCD and ILTS groups did not differ significantly from each other (Z23 = 1.49 and p = 0.14).

Fig. 1.

Probability of incident MCI/dementia among baseline risk groups. Risk of progression to MCI/dementia over follow-up time, by baseline diagnostic group. NC, normal controls; SCD, subjective cognitive decline; ILTS, isolated low test scores.

Table 2 presents Cox proportional hazards model results for prediction of incident MCI. Older age, minoritized racial identity, and baseline diagnostic group (reference = NC) were significant risk factors. Both SCD and ILTS groups were significantly different from the NC group, with comparable effect size (HR = 4.62, p < 0.01 SCD versus NC; HR = 4.80, p < 0.01 ILTS versus NC). As the ILTS group was older and had a higher proportion of people identifying as a minoritized race, MCI risk between the ILTS and SCD groups were not different (HR = 1.04, p = 0.91) after controlling for age, minoritized racial identity, education, and sex.

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazards model (HR: hazard ratio) predicting incident MCI/dementia in full longitudinal sample (n = 215)

| Variables | HR | Z test | p | 95% CI HR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Female sex | 1.07 | 0.18 | 0.86 | (0.49, 2.36) |

| Education | 0.90 | −1.51 | 0.13 | (0.79,1.03) |

| Age | 1.08 | 2.99 | <0.01 | (1.03, 1.14) |

| Minoritized Racial Identity, N (%) | 3.13 | 2.56 | 0.01 | (1.30, 7.51) |

| SCD (reference = NC) | 4.62 | 3.09 | <0.01 | (1.75,12.23) |

| ILTS (reference = NC) | 4.80 | 2.97 | <0.01 | (1.70,13.58) |

| Family History of MCI/Dementia | 1.53 | 1.22 | 0.22 | (0.77, 3.02) |

| APOE ε4 | 0.97 | −0.08 | 0.93 | (0.47, 2.01) |

NC, normal controls; SCD, subjective cognitive decline; ILTS, isolated low test scores.

In a post-hoc analysis evaluating the subsequent stability of MCI: of the n = 36 cases of incident MCI/dementia, 6 had no further follow-up (median number of visits = 2, range 0–9). Of those with further follow-up visits after incident MCI, 63% remained MCI (n = 14) or progressed to dementia (n = 5), while the remaining reverted to NC (n = 2), SCD (n = 7) or ILTS (n = 2).

In sensitivity analyses to probe robustness of the primary Cox model results, we found that restricting the model to white participants only (n = 215) (Supplementary Table 1), significant predictors of incident MCI/dementia were age, SCD classification (NC as reference) and ILTS classification (NC as reference). Sex, education, family history and APOE ε4 were not significant predictors. In the model combining SCD and ILTS (Supplementary Table 2), age, minoritized racial/ethnic identity and the combined SCD + ILTS baseline group (NC as reference) were significant, while sex, education, family history, and APOE ε4 were not significant.

DISCUSSION

This study examined two baseline risk states for cognitive decline within a “clinical gray zone,” neither clearly meeting criteria for normal cognition or MCI: 1) subjective cognitive complaints with normal neuropsychological test performance (SCD), and 2) lower-than-expected test performance without subjective cognitive complaints (ILTS). The ILTS group was older on average and had a higher proportion of racially minoritized groups (45% versus19% of controls). The SCD group had more years of education than the ILTS group. Both SCD and ILTS groups showed increased risk for clinical progression to MCI compared to NC, adjusting for significant risk/protective factors. In sum, MCI baseline risk states look different from each other, especially with respect to demographic correlates; however, both risk states predict faster progression than control participants, over and above demographic differences.

Few studies have directly compared these two presentations of cognitive decline risk states on clinical outcomes. Similar classifications, methods and findings were reported in a Florida ADRC research cohort [11]. One salient difference was that the ‘pre-MCI-NP’ category was restricted to memory test impairment, whereas in the present study, ILTS also included low scores on non-memory tests. Other studies focusing on objectively measured, often termed “subtle,” test impairment not meeting MCI diagnostic thresholds, have reported associated increased amyloid-β accumulation and cortical thinning over time, prospectively [10], and increased risk for cognitive decline in newly diagnosed Parkinson’s disease [12]. Papp et al. [30] measured subtle longitudinal decline on test performance over three years in clinically normal older adults with elevated amyloid-β and found steeper decline increased risk for progression to MCI. The present study adds support to the literature indicating lower-than-expected cognitive test scores, without meeting MCI criteria, confer risk for future clinical progression, and to about the same degree as SCD.

Age, education, and minoritized status were key demographic group differences between SCD and ILTS. A sizeable literature documents increased risk of SCD for clinical progression and presence of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers [31]. However, evidence also suggests Black research participants are less likely to endorse subjective memory complaints [32, 33], and perhaps other minoritized racial/ethnic groups, as well [34, 35]. There is a critical need to widen consideration of how early risk factors for cognitive decline manifest in different research, clinical, and community settings. Achieving greater representation of minoritized races and ethnicities in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias research studies should continue to be a high priority [36, 37], as is engaging minoritized older adults in clinical screening and follow-up [2]. As normative data and cut- offs for neuropsychological tests directly affect specificity and sensitivity of MCI or dementia diagnosis, validation of diagnostic tools and criteria needs to be established with adequate inclusion of under-represented groups [38].

Important limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size, small number of incident MCI/dementia cases, and follow-up duration of 2.7 years on average. Although we followed some participants up to 9.3 years, there was a significant proportion with no follow-up, and overall limited power to better understand selection bias or investigate informative interactions, such as effects of minoritized status and other demographic factors by baseline diagnosis. The ILTS group had the shortest mean follow-up of 2.0 years; this suggests the effect of baseline ILTS on progression risk is likely underestimated, since people with cognitive disorders are over-represented in loss to follow-up [39]. Baseline diagnostic definitions were not independent of the outcome; however, we believe the diagnostic consensus process, involving a large inter-disciplinary group of clinical investigators, and a gold standard in dementia research, mitigates the risk of frank diagnostic bias. Some minoritized racial groups were too small to analyze separately. Results may not generalize well outside an academic memory disorders research center, where participants receive diagnostic feedback. The neuropsychological test norms were derived from samples which were not well representative of minoritized people, which was one of the key rationales for establishing the ILTS classification, in an attempt to avoid being overly punitive (i.e., an MCI diagnosis) as a result of non-representative norms. Finally, inclusion of biomarkers may well change prediction results. As Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias biomarkers become more available and clinically meaningful, their nexus with early clinical signs and symptoms should be investigated for potential application in clinical settings.

In summary, this study found comparably heightened risk for progression to MCI from both baseline SCD and ILTS. Different presentations of early risk are associated with minoritized group identification and are likely important to advancing cognitive health equity in aging. Both should be considered and included in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias prevention trials and investigated further in observational studies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by P30 AG066468 from the NIH-NIA. We thank University of Pittsburgh First Experience in Research students, Lauren Chmielewski and Jillian Farrell, along with the study participants and staff of the University of Pittsburgh ADRC without whose time and effort this research would not be possible.

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/21-5607r2).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-215607.

REFERENCES

- [1].Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR Jr, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH (2011) Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, 280–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fowler NR, Perkins AJ, Gao S, Sachs GA, Boustani MA (2019) Risks and benefits of screening for dementia in primary care: The Indiana University Cognitive Health Outcomes Investigation of Comparative Effectiveness of Dementia Screening (IU CHOICE) Trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 68, 535–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox FC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Phelps CH (2011) The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging- Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, 270–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Clark LR, Delano-Wood L, Libon DJ, McDonald CR, Nation DA, Bangen KJ, Jak AJ, Au R, Salmon DP, Bondi MW (2013) Are empirically-derived subtypes of Mild Cognitive Impairment consistent with conventional subtypes? J Int Neuropsychol Soc 19, 635–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jessen F, Amariglio R, van Boxtel M, Breteler M, Ceccaldi M, Chételat G, Dubois B, Dufouil C, Ellis KA, van der Flier WM, Glodzik L, van Harten AC, de Leon MJ, McHugh P, Mielke MM, Molinuevo JL, Mosconi L, Osorio RS, Perrotin A, Petersen RC, Rabin LA, Rami L, Reisberg B, Rentz DM, Sachdev PS de la Sayette V, Saykin AJ, Scheltens P, Shulman MB, Slavin MJ, Sperling RA, Stewart R, Uspenskaya O, Vellas B, Visser PJ, Wagner M, Subjective Cognitive Decline Initiative (SCD-I) Working Group (2014) A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 10, 844–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Peterson RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, Getchius TS, Ganguli M, Gloss D, Gronseth GS, Marson D, Pringsheim T, Day GS, Sager M, Stevens J, Rae-Grant A (2018) Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment: Report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 90, 126–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Patnode CD, Perdue LA, Rossom RC, Rushkin MC, Redmond N, Thomas RG, Lin JS (2020) Screening for cognitive impairment in older adults: Updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 323, 764–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cui L, Zhang Z, Lo CZ, Guo Q (2021) Local functional MR change pattern and its association with cognitive function in objectively-defined subtle cognitive decline. Front Aging Neurosci 13, 684918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Thomas KR, Bangen KJ, Weigand AJ, Edmonds EC, Wong CG, Cooper S, Delano-Wood L, Bondi MW, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2020) Objective subtle cognitive difficulties predict future amyloid accumulation and neurodegeneration. Neurology 94, e394–e406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Loewenstein DA, Greig MT, Schinka JA, Barker W, Shen Q, Potter E, Raj A, Brooks L, Varon D, Schoenberg M, Banko J, Potter H, Duara R (2012) An investigation of PreMCI: Subtypes and longitudinal outcomes. Alzheimers Dement 8, 172–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jones JD, Uribe C, Buch J, Thomas KR (2021) Beyond PD-MCI: Objectively defined subtle cognitive decline predicts future cognitive and functional changes. J Neurol 268, 337–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Morris J (1993) The clinical dementia rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology 143, 2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kamboh MI, Aston CE, Hamman RF (1995) The relationship of APOE polymorphism and cholesterol levels in normoglycemic and diabetic subjects in a biethnic population from the San Luis Valley, Colorado. Atherosclerosis 112, 145–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeyx R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, 263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Petersen RC (2004) Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med 256, 183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) (2008) NACC Uniform Data Set (UDS).

- [18].Weintraub S, Besser L, Dodge HH, Teylan M, Ferris S, Goldstein FC, Giordani B, Kramer J, Loewenstein D, Marson D, Mungas D, Salmon D, Welsh-Bohmer K, Zhou X, Shirk SD, Atri A, Kukull WA, Phelps C, Morris JC (2018) Version 3 of the Alzheimer Disease Centers’ neuropsychological test battery in the Uniform Data Set (UDS). Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 32, 10–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL (1984) A new rating scale for Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 141, 1356–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lopez OL, Becker JT, Jagust WJ, Fitzpatrick A, Carlson MC, DeKosky ST, Breitner J, Lyketsos CG, Jones B, Kawas C, Kuller LH (2006) Neuropsychological characteristics of mild cognitive impairment subgroups. J Neurol Neurosurg 77, 159–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wechsler D (1981) Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Revised, The Psychological Corporation, New York. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Golden CJ (1976) Identification of brain disorders by the stroop color and word test. J Clin Psychol 32, 654–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Freedman M, Leach L, Kaplan E, Winocur G, Shulman KI, Delis DC (1994) Clock Drawing: A neuropsychological analysis, Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Benton AL (1968) Differential behavioral effects in frontal lobe disease. Neuropsychologia 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Becker JT, Boller F, Saxton J, McGonigle-Gibson KL (1987) Normal rates of forgetting of verbal and non-verbal material in Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex 23, 59–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S (1983) Boston Naming Test, second edition, Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bland JM, Altman DG (1995) Multiple significance tests: The Bonferroni method. BMJ 310, 170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kaplan EL, Meier P (1958) Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 53, 457–481. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, second edition, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Papp KV, Buckley R, Mormino E, Maruff P, Villemagne VL, Masters CL, Johnson KA, Rentz DM, Sperling RA, Amariglio RE, Collaborators from the Harvard Aging Brain Study, the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative and the Australian Imaging, Biomarker and Lifestyle Study of Aging (2020) Clinical meaningfulness of subtle cognitive decline on longitudinal testing in preclinical AD. Alzheimers Dement 16, 552–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Rabin LA, Smart CM, Amariglio RE (2017) Subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 13, 369–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].John SE, Evans SA, Hanfelt J, Loring DW, Goldstein FC (2020) Subjective memory complaints in White and African American participants. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 33, 135–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hill NL, Mogle J, Bhargava S, Bell TR, Wion RK (2019) The influence of personality on memory self- report among black and white older adults. PLoS One 14, e0219712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Mukadam N, Cooper C, Livingston G (2013) Improving access to dementia services for people from minority ethnic groups. Curr Opin Psychiatry 26, 409–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Roberts LR, Schuh H, Sherzai D, Belliard JC, Montgomery SB (2015) Exploring experiences and perceptions of aging and cognitive decline across diverse racial and ethnic groups. Gerontol Geriatr Med 1, 2333721415596101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wilkins CH, Schindler SE, Morris JC (2020) Addressing health disparities among minority populations: Why clinical trial recruitment is not enough. JAMA Neurol 77, 1063–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Babulal GM, Quiroz YT, Albensi BC, Arenaza-Urquijo E, Astell AJ, Babiloni C, Bahar-Fuchs A, Bell J, Bowman GL, Brickman AM, Chételat G, Ciro C, Cohen AD, Dilworth-Anderson P, Dodge HH, Dreux S, Edland S, Esbensen A, Evered L, Ewers M, Fargo KN, Fortea J, Gonzalez H, Gustafson DR, Head E, Hendrix JA, Hofer SM, Johnson LA, Jutten R, Kilborn K, Lanctôt KL, Manly JJ, Martins RN, Mielke MM, Morris MC, Murray ME, Oh ES, Parra MA, Rissman RA, Roe CM, Stantos OA, Scarmeas N, Schneider LS, Schupf N, Sikkes S, Snyder HM, Sohrabi HR, Stern Y, Strydom A, Tang Y, Terrera GM, Teunissen C, van Lent DM, Weinborn M, Wesselman L, Wilcock DM, Zetterberg H, O’Bryant SE, International Society to Advance Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment, Alzheimer’s Association (2019) Perspectives on ethnic and racial disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: Update and areas of immediate need. Alzheimers Dement 15, 292–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Manly JJ, Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, Deters KD (2021) Inclusion of underrepresented groups in preclinical Alzheimer disease trials—opportunities abound. JAMA Netw Open 4, e2114606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Jacobsen E, Ran X, Liu A, Chang CH, Ganguli M (2021) Predictors of attrition in a longitudinal population-based study of aging. Int Psychogeriatr 33, 767–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.