Abstract

Mitigating the COVID-19 related disruptions in mental health care services is crucial in a time of increased mental health disorders. Numerous reviews have been conducted on the process of implementing technology-based mental health care during the pandemic. The research question of this umbrella review was to examine what the impact of COVID-19 was on access and delivery of mental health services and how mental health services have changed during the pandemic. A systematic search for systematic reviews and meta-analyses was conducted up to August 12, 2022, and 38 systematic reviews were identified. Main disruptions during COVID-19 were reduced access to outpatient mental health care and reduced admissions and earlier discharge from inpatient care. In response, synchronous telemental health tools such as videoconferencing were used to provide remote care similar to pre-COVID care, and to a lesser extent asynchronous virtual mental health tools such as apps. Implementation of synchronous tools were facilitated by time-efficiency and flexibility during the pandemic but there was a lack of accessibility for specific vulnerable populations. Main barriers among practitioners and patients to use digital mental health tools were poor technological literacy, particularly when preexisting inequalities existed, and beliefs about reduced therapeutic alliance particularly in case of severe mental disorders. Absence of organizational support for technological implementation of digital mental health interventions due to inadequate IT infrastructure, lack of funding, as well as lack of privacy and safety, challenged implementation during COVID-19. Reviews were of low to moderate quality, covered heterogeneously designed primary studies and lacked findings of implementation in low- and middle-income countries. These gaps in the evidence were particularly prevalent in studies conducted early in the pandemic. This umbrella review shows that during the COVID-19 pandemic, practitioners and mental health care institutions mainly used synchronous telemental health tools, and to a lesser degree asynchronous tools to enable continued access to mental health care for patients. Numerous barriers to these tools were identified, and call for further improvements. In addition, more high quality research into comparative effectiveness and working mechanisms may improve scalability of mental health care in general and in future infectious disease outbreaks.

Keywords: COVID-19, Mental health service delivery, e-mental health psychological interventions, Implementation, Scalability, Continuity of care

1. Background

The COVID-19 pandemic with its large-scale loss of lives, long-term morbidity due to post-COVID-19 conditions and immense emotional and societal changes, has resulted in an unprecedented global health crisis (Huang et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). Besides great cross-national variation and variations across waves, the primary response of governments to contain the spread of Sars-CoV-2 has been to issue measures limiting social contacts between people and requiring people to stay at home (Hale et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2022). The more stringent measures such as lockdowns, have however been found related to higher levels of anxiety and depression (Buffel et al., 2022; Prati & Mancini, 2021). Altogether, it has been estimated that the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a relatively small but meaningful increase of mental health problems within general and specific populations such as young people, women and people with pre-existing health conditions, at least in the first half year of the pandemic (Fancourt, Steptoe, & Bu, 2021; Pierce et al., 2021; Robinson, Sutin, Daly, & Jones, 2022; Santomauro et al., 2021).

Besides this moderate increase of mental health problems, the COVID-19 pandemic and its control measures threatened the continuity and access to mental health care services (World Health Organization, 2021). Although experts and international bodies called for immediate action to integrate mental health into response- and preparedness plans in the early phase of the pandemic (Holmes et al., 2020; Xiang et al., 2020; WHO Executive board, 2020), significant reduction of mental health services and contacts for anxiety, depression, and other mental health conditions could not be prevented (Mansfield et al., 2021; WHO, 2020). This observed reduction in health-care contacts is particularly concerning for people with mental illness(es). They are at greater risk of poor health outcomes from COVID-19 (Ceban et al., 2021; Vai et al., 2021), more often depend on regular outpatient services and prescriptions (Pfefferbaum & North, 2020; Yao, Chen, & Xu, 2020) and more often suffer from socio-economic inequalities such as a low-income and delayed mental health care during the pandemic (Lee & Singh, 2021; Sareen, Afifi, McMillan, & Asmundson, 2011). A significant change in mental health outcomes in people with pre-existing mental health problems during the initial stages of the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic times was however not found (Robinson et al., 2022). Possibly, adaptations in mental health service provision may have buffered negative effects of the pandemic (Moreno et al., 2020; Yao et al., 2020).

Most mental health services adapted to the sudden disruptions in continuity of care by rapidly shifting to digital formats such as remote synchronous telemental health care (sTMH) delivery (e.g. video- or telephone-conferencing) (Ganjali, Jajroudi, Kheirdoust, Darroudi, & Alnattah, 2022). Formats such as guided or unguided internet-based psychotherapy or psychosocial support mobile- or web-applications, often referred to as asynchronous virtual mental health care (aVMH), have also been implemented during the pandemic (Richardson et al., 2020). Digital formats including guided self-help CBT and telephone-based CBT have recently been evaluated in meta-analyses and showed moderate to large effect sizes when compared to wait-list control conditions and comparable effectiveness as face-to-face psychotherapy. Acceptability of guided self-help CBT, however, was significantly lower (Carlbring et al., 2018; Cuijpers et al., 2019). sTMH services and, to a greater extent, aVMH services have the potential to expand the reach and accessibility of mental health care. In reality, however, their translation and implementation in routine mental health care lagged behind until the pandemic unfolded. Factors such as expectations and preferences of patients and mental health care staff, availability and reliability of required technologies, and appropriateness of interactions such as therapeutic alliance delivered through ICT, are thought to play a role in the delayed uptake of sTMH and aVMH interventions (Vis et al., 2018). Interestingly, during the COVID-19 pandemic other common-as well as specific therapeutic factors at work in various psychosocial treatment modalities, were rated, particularly by therapists rather than service users, as more typically used during face-to-face rather than remote psychotherapy (Probst et al., 2021). These findings illustrate the importance of proper training to adapt to the remote delivery of interventions. Not all therapeutic interventions however, can be tailored well to remote psychotherapy. For example, specific interventions such as exposure (e.g. during PTSD treatment) have been found difficult to implement remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic (Cassiello-Robbins, Rosenthal, & Ammirati, 2021; van Leeuwen et al., 2021). Moreover, significant variation was found in the provision of psychotherapy during the first half year of the pandemic in terms of number of patients treated and change in mode of delivery from face-to-face to remote psychotherapy across several mid-European countries. This was due to country-specific regulations, reimbursement issues or experience in use of e-mental health applications (Humer & Probst, 2020).

From the onset of the pandemic, a comprehensive research base of primary studies into mental health disruptions and the subsequent adaptation and implementation of mental health interventions quickly developed. In a large number of systematic reviews these findings have been synthesized in terms of barriers and facilitators of this implementation process during the pandemic. However, the available review findings are rather fragmented. A good overview of the barriers and facilitators of the implementation of technology and interventions to scale up evidence-based mental health treatments in future pandemics is needed. The aim of this umbrella review was threefold: (1) to identify the main disruptions in the provision of mental health care during the pandemic; (2) to map the most important adaptations during the pandemic in terms of digital mental health care; and (3) to identify barriers and facilitators of implemented adaptations of synchronous and asynchronous remote interventions. To understand and structure these findings, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Damschroder et al., 2009) will be used. This organizes implementation aspects of adapted mental health interventions during the pandemic into five domains (the intervention characteristics, the characteristics of individuals involved, the inner and outer settings and implementation processes). In addition to these three aims, the methodological quality of the reviews and limitations to the evidence presented will be evaluated in order to identify discrepancies or gaps in the current evidence base.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

We followed guidelines for umbrella reviews (Ioannidis, 2009; Papatheodorou, 2019; Solmi, Correll, Carvalho, & Ioannidis, 2018). An umbrella review systematically collects and evaluates information from multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses on all clinical outcomes for which have been collected and follows a uniform approach to allow their comparison (Fusar-Poli & Radua, 2018). With an umbrella review approach a clear picture of broad healthcare areas can be provided and may highlight whether the evidence base on a topic is consistent or contradictory (Fusar-Poli & Radua, 2018; Ioannidis, 2009). This umbrella review is part of a broader umbrella that includes other research questions that will not be reported here, including the (change of) prevalence of mental disorders and mental health symptoms, suicidal behavior and thoughts, and the risk for (severe) COVID-19 among people with pre-existing mental disorders (registered protocol available in the Open Science Framework platform (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/JF4Z2).

2.2. Literature search, study selection and data extraction

Ovid MEDLINE All, Embase (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), CINAHL, and Web of Science were initially searched from December 31, 2019 until October 6, 2021. An update of the search was performed to capture additional reviews published between October 7th, 2021 and August 12, 2022. The search strategy combined keywords for (systematic) reviews or meta-analyses with a very broad combination of key- and text words on COVID-19 and mental disorders or problems. We anticipated that some studies were answering multiple objectives of our broader umbrella review. All search strings are provided in the Appendix.

Pairs of two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts (CP, CC, SY, MG, FB, JW, ND, DF, MC and AW) using the software tool Rayyan and Endnote for deduplication. The full texts of all records considered potentially eligible by at least one of the reviewers were again screened by two independent reviewers. Disagreements were resolved via consensus, involving a third, senior member of the team. Reasons for exclusion at full-text level were recorded.

Data on review characteristics (time and number of databases searched, geographical scope), methodology (aims, number of studies included, review type), population and healthcare settings, interventions and outcomes of interest were extracted by two independent researchers according to a predefined data extraction sheet. Sheets were cross-checked, and disagreements resolved by discussion or by consultation with a third investigator. Researchers extracted statements summarizing the authors’ interpretation of primary study-findings on type of disruptions, adaptations and barriers and facilitators to the implementation of remote interventions.

2.3. Eligibility criteria

Studies defined as systematic or scoping reviews of non-randomized or randomized studies were included based on the following eligibility criteria: reviews should have 1) been published in a peer-reviewed international journal; and should have included: 2) study selection criteria, 3) systematically searched in at least one bibliographic database, 4) included a list and synthesis of included studies, 5) primary studies with data collected after December 31, 2019 (the date that the first Chinese outbreak was first reported to WHO), 6) no restrictions regarding population or type of mental health service (according to the definition of the American Psychological Association - APA), 7) a synthesis of information (i.e. barriers and facilitators) on access to COVID-19 adapted mental healthcare (e.g., changes in numbers accessing services, frequency or intensity of services, waiting times) or information of changes in mental health service delivery (e.g., types of service available, adapted delivery mode(s)). There were no language restrictions and systematic reviews from other infectious disease epidemics were only eligible if they also included separate data from COVID-19 studies.

2.4. Quality of included systematic reviews

The quality of included systematic reviews was assessed by two independent reviewers for each question using AMSTAR-2 (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews), a 16-point assessment tool to critically appraise the methodological quality of systematic reviews of randomized and non-randomized studies (Shea et al., 2017) (see Appendix for details). Due to the inclusion of mainly systematic reviews without meta-analyses, items concerning meta-analyses (items 11, 12 and 15) were not applicable for scoring. Also, small adaptations to some items were performed to make them more suitable to score (see Appendix). For interpreting the scores, we deviated from the broader umbrella review protocol (that includes meta-analyses) by not using the proposed scheme for identifying weaknesses in terms of critical and non-critical items (Shea et al., 2017). Instead, we summed up yes and partial yes scores to arrive at a total score based on the relevant AMSTAR-2 items.

3. Results

3.1. Selection and inclusion of systematic reviews

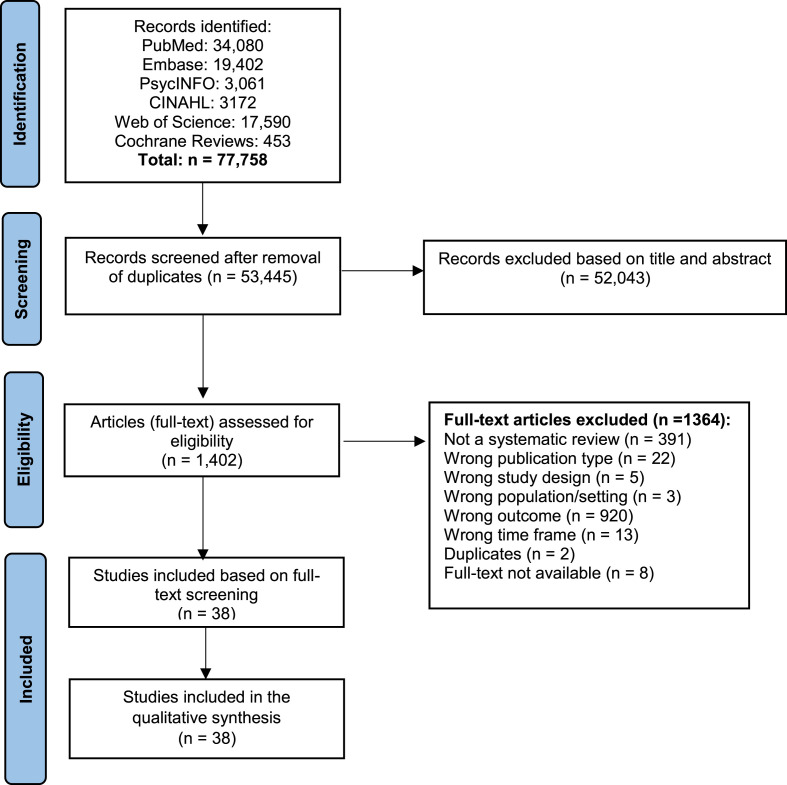

The initial and updated systematic searches yielded in total 77,758 records resulting in 53,445 records after removal of duplicates. After title and abstract screening, 1402 articles (full-text, when available) for the broader umbrella review on mental health impact of COVID-19 were retrieved and assessed. Of these, in total 38 systematic reviews from our initial and updated searches met the umbrella review criteria specified above. The PRISMA flowcharts in Fig. 1 describe the inclusion process with reasons for exclusion.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the inclusion of systematic reviews of the impact of COVID-19 on access and delivery of mental health care and services based on initial (Dec. 31, 2019–Oct. 6, 2021) and updated search (Oct. 7, 2021–Aug. 12, 2022).

3.2. Characteristics of included systematic reviews

All reviews used narrative synthesis as method to extract findings from a median of 11 highly heterogenous primary studies and information sources (see Table 1 in Appendix). Most reviews were defined as ‘systematic’ or ‘scoping’ and used the PRISMA (k = 20), the PRISMA-P statement (k = 3) on reporting of systematic reviews (Moher et al., 2009, 2015) or the PRISMA-ScR statement for scoping reviews (k = 7) (Tricco et al., 2018). Eight reviews followed no explicit reporting guidelines. Only three reviews were restricted to a specific geographical area (i.e. India, UK, or Philippines) while most reviews covered studies from multiple countries and continents, and most often from USA (k = 28), European countries (k = 27); China (k = 17); UK (k = 18) or Canada (k = 9). Most reviews (k = 22, Table 1) presented findings from 2020. Sixteen reviews searched for studies until the end of 2021 or the first quarter of 2022 (Hatami et al., 2022). As presented in the characteristics table included in the Appendix, reviews most commonly synthesized findings from studies performed in outpatient mental health services (k = 17), inpatient psychiatric services (k = 10), community mental health services (k = 6) and (general hospital) emergency departments (k = 7). Forensic settings (k = 4), home settings (k = 5), non-specialist care settings (k = 5) and university-settings (k = 3) were less often included. Populations studied were often people at risk for deterioration of mental health for a number of reasons including: pre-existing mental disorders such as being psychiatric (in)patients and/or having vulnerable living situations (k = 29), institutionalized or incarcerated populations (k = 4), (mental) health care workers (k = 9), and general (mixed) populations including youth and older people (k = 14). The primary aim of most reviews was to develop an overview of the impact of COVID-19 on the delivery of and access to mental health care and the adaptations made to interventions and strategies (e.g. organizational, technological) to continuously support populations with (a risk of) mental disorders (k = 21). Others (k = 29) more exclusively focused on the on barriers and/or facilitators of implementing tele- and virtual mental health care during the pandemic.

Table 1.

Disruptions, changes and adaptations in mental health care delivery during COVID-19 pandemic for each half year in the pandemic.

| Author, year | Disruption in access and availability MH care | Changes and adaptations synchronous TMH and asynchronous VMH care | Q | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Search up to first half year of 2020 | ||||

| Cabrera et al. (2020) | Less outpatient appointments and shorter inpatient stays. | Telepsychiatry (videoconferencing) | 6 | |

| Meloni et al. (2020) | Reduction psychiatric hospitalization and consultations psychiatric emergency departments. Reorganization of psychiatric departments for COVID-19 patients. Total/partial mental health services closures, home visits, (early) exit permits. | Telepsychiatry (videoconferencing, telephone) and digital health utilization (online, websites) | 4 | |

| Raphael et al. (2021) | Inpatient: increased outdoor visits; external and group activities suspended, early discharge with intensive telephone follow-up, remote risk assessment and face-to-face only for high risk. | Outpatient: online self-help (websites, apps) and telepsychiatry (videoconferencing, telephone). Inpatient: remote triaging, virtual visits by staff. | 7 | |

| Thenral and Annamalai (2020) | Not reported | Synchronous (videoconference, telephone) to asynchronous (e.g. social media, games) care using artificial intelligence. | 2 | |

| Yue et al. (2020) | Hospitals: early discharge, suspension of visits. Community and outpatient: in person visits for psychiatric emergencies only. |

Psychoeducational and self-help material distributed online (e.g. e-mails or Alihealth platforms, text-messages, WeChat) and community- (e.g. hotline) and outpatient telepsychiatry (e.g. through telephone or Zoom) | 5 | |

| Search up to second half of 2020 | ||||

| Abd-Alrazaq et al. (2021) | Not reported | Synchronous delivery and adaptations most common (77%): mostly telemedicine (85%) most often telepsychiatry (60%) and follow-up consultations (40%) (e.g. videoconferencing, telephone) and clinical decision support tools (9%; desktop or mobile apps). | 5 | |

| Abraham, Chaabna, et al. (2021) | Not reported | Telemental health (telephone, videoconferencing e.g. CBT by psychologists and psychiatrists) and digital mental health technologies (e.g. applications smartphone, websites). | 7 | |

| Ali, Khoja, and Kazim (2021) | Reduction in face-to-face mental health consultations and care. | Remote (audiovisual) telemental health (telephone and television-based technology) with trained health professionals and in internet-based mental health assessment and management of anxiety and depression. | 2 | |

| Appleton et al. (2021) | Face-to-face models of care transitioned to remote delivery | Studies report high uptake of telemental health delivery by service and care providers (videoconferencing, telephone, videos most common; email, text-messaging, online forums less common). | 6 | |

| Baumgart et al. (2021) | Reorganizing psychiatric facilities: reduced staff and outpatient appointments, less admissions, screening to discharge more easily. | Developed mental health programs to prevent onset mental health disorders (in GP, HCW, psychiatric patients) and implementation of telemental health consultations and counseling for private practice and community services. | 5 | |

| Chiesa et al. (2021) | Lower availability and postponed face-to-face services and hospital access. | Tele-psychotherapy and meetings for clinical decisions and team care (online/videoconferencing). | 4 | |

| Clemente-Suárez et al. (2021) | Closure of psychiatric services; face-to-face care only for high-risk patients; shortened inpatient stay and reduced outpatient visits. | Telepsychiatry (video or telephone calls), enhanced hotline use, psychoeducation material distributed (online). | 3 | |

| Drissi et al. (2021) | Number of patients treated by personal contact decreased significantly. | Remote psychotherapy and appointments (telephone) and internet-based mental health (e-learning content, mobile phone applications, social media platforms). | 2 | |

| Filho, Araújo, Fernandes, and Pillon (2021) | Increased demand from psychiatric institutions and restriction of visits. Reduction of hospital admission, exclusion of patients without serious mental health state, more isolation units, earlier hospital discharge, activities only for hospitalized. | Not reported. Adoption of remote services for care and visits recommended. | 3 | |

| John et al. (2021) | Reduced or same levels of presentation to services with suicidal thoughts. Higher proportion of emergency department presentations of suicide attempts (because other causes decreased). Calls for suicidal threats inversely correlated with rates of infections. | Not reported. | 8 | |

| Kane et al. (2022) | Remote care to reduce COVID-19 infection risks. | Mental health care adopted new digital technologies and integrated them for remote monitoring and assessment (online – videoconferencing and telephone assessment and care). | 2 | |

| Lemieux et al. (2020) | Release or home detention of inmates with mental health issues. Fewer and slower admission process, fewer group activities or only outdoors, suspension of therapeutic and recreational activities and more isolation. | Communication of staff online and virtual visits to patients (videoconferencing); telepsychiatry for assessment and intervention (videoconferencing, telephone). | 4 | |

| Li et al. (2021) | Not reported. | Telepsychiatry (videoconferencing, telephone): initially a decrease in service use and more no-shows, later an increase even from pre-pandemic levels and decreased no-shows. | 3 | |

| Minozzi, Saulle, Amato, and Davoli (2021) | Reduction of volunteer admissions to psychiatric hospital and reduced access to emergency department for self-harm/suicide attempts and psychiatric problems. | Not reported. | 6 | |

| Murphy et al. (2021) | Lack of access to usual care. | New online programmes, hotlines, courses through online platforms, videoconferencing and apps (esp. for HCWs). | 4 | |

| Soklaridis et al. (2020) | Not reported. | Rapidly developed new psychological interventions and support and referral systems for HCWs and COVID-19 patients (e.g. hotlines-telephone, internet-based self-help psychosocial support program). | 9 | |

| Tuczyńska et al., 2021 | Decrease in psychiatric emergency admissions, in referrals from primary care to specialized mental health care services and in mental health consultations. | No reported. | 2 | |

| Search up to first half year of 2021 | ||||

| Ardekani et al. (2021) | Not reported | Fully online services and support groups switched to online videoconferencing and group chats. Short videos addressing issues and coping strategies. Near peer monitoring through social media platforms. | 7 | |

| Bertuzzi et al. (2021) | Not reported | Telehealth delivery of mental health care strategies for caregivers (phone vs. videoconferencing). | 10 | |

| Fornaro et al. (2021) | Higher hospitalization rates | Telepsychiatry (telephone, videoconference) and online assessment of mental health (survey). | 7 | |

| Gao, Bagheri, and Furuya-Kanamori (2022) | Reduced access face-to-face treatment and support networks; reduced admissions; treatment suspension, cancellation non-urgent treatment. | Online treatment (teletherapy, videoconferencing); | 5 | |

| Keyes et al. (2022) | Not reported | Increased use of telemedicine (telephone and videoconferencing) and digital interventions in mental health care internationally. Assessment of effectiveness and feasibility of digital (online) mental health interventions. | 3 | |

| Samji et al. (2021) | Mixed findings: increase and decrease in pediatric emergency department presentation. Same or decreased levels of secondary mental healthcare referral. Higher hospitalization rates but shorter stay. | Not reported | 8 | |

| Selick et al. (2021) | Decreased service use (of virtual care) compared to in person prior to the pandemic. | Telepsychiatry (videoconferencing and telephone). | 5 | |

| Search up to second half year of 2021/early 2022 | ||||

| Devoe et al. (2022) | Increased hospital admissions (48%) in admissions for eating disorders; treatments shortened, delayed, lack of professional assistance for mental problems. | Telemental health care (videoconferencing, telephone) and VMH (instant chat-messaging) | 8 | |

| Hatami et al. (2022) | Not reported | Development of and transition to tele-medicine services (videoconference) and digital mental health care (online apps). | 5 | |

| Lignou, 2022 | Reduction in use primary care; difficulties in accessing medication. Children with neurodevelopmental conditions: restrictions to face-to-face clinician contacts. Non-urgent new referrals on hold, significantly increased waiting lists. | Increased use telemedicine within universal children's services (mainly telephone consultation or videoconferencing 98%). Increase in digital healthcare psycho-educational resources (webinars, online videos). | 6 | |

| Linardon et al. (2022) | Increased demand eating disorder services. Significant disrupted or negatively impacted treatment. | Transitioning to online treatment (telehealth, videoconferencing). | 5 | |

| Mohammadzadeh, Maserat, and Davoodi (2022) | Not reported | Some existing infrastructure was upgraded and used to provide COVID-19 adapted mental health services or new systems (online parenting tips; TMH measurement-based care and protocols) were developed. | 7 | |

| Narvaez (2022) | Not reported | Not reported | 3 | |

| Segenreich (2022) | Changes in medication treatment patterns (dosage lower or stopped) and difficulties in purchasing ADHD medication. Difficulties of evaluating and diagnosing new symptoms or comorbidities. | Videoconferencing for ADHD medication and psychotherapy and for remote monitoring of vital functions through smart-phones in ADHD medication users. | 4 | |

| Siegel et al. (2021) | Decrease in missed and cancelled appointments. | Telepsychiatry (Zoom, telephone, MyChat). | 2 | |

| Steeg et al. (2022) | High-moderate quality studies: decrease in service utilization (first months) and decrease in frequency of presentation for self-harm episodes. | Not reported. | 9 | |

3.3. Quality of the reviews

The AMSTAR-2 aggregated ratings of included systematic reviews on applicable criteria ranged from 2 to 10 indicating a low to moderate/high level of quality (see Appendix). Twenty-three studies met (either partially or completely) a maximum of five of the 13 relevant criteria indicating low quality. Fifteen systematic reviews were of more moderate to high quality with total ratings from 6 to 10 of the applicable AMSTAR-2 criteria. Almost all systematic reviews included a PICO (patient/population, intervention, comparison and outcomes)-based review question (k = 35) and reported potential conflict of interest for the review (k = 34). Study-selection and data extraction were, respectively, performed by at least two reviewers in 22 and 14 reviews. In fourteen reviews an (unregistered) protocol was developed or published prior to data-collection. Risk of bias was accounted for when interpreting results in eight reviews. Clinical or methodological heterogeneity was accounted for in five reviews. The proportion of reviews with an AMSTAR-2 rating of 6 or higher was 32% in reviews covering primary studies until end of 2020 (7 of k = 22) and 50% in reviews covering studies until end of 2021 or early 2022 (8 of k = 16).

Besides AMSTAR-2 ratings of the methodological quality of the included reviews, authors of reviews flagged important limitations to the primary study data included in their reviews. The main limitation reported was that the conclusions had to be drawn from primary studies with heterogenous designs and of generally poor quality (e.g. due to selective sampling and high risk of bias). Meta-analyzing quantitative data was often methodologically not possible or beyond the scope of the reviews. Another important limitation emphasized by authors was the small timeframe of earlier reviews with searches until the end of 2020 that often included rapidly conducted primary articles with weak scientific methodology.

3.4. Disruptions in the delivery of mental health care during the early phase of the pandemic

Table 1 shows descriptive findings from included reviews (k = 38) on disruptions in mental health care delivery for each half year starting from early 2020 until the end of 2021 or early 2022. Quantitative data supporting the review findings on disruption of care were however lacking. In many of these reviews it was concluded that face-to-face or in-person appointments for outpatients were reduced, shortened, postponed or canceled or only available for high risk patients or psychiatric emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic (k = 17). Difficulties with prescription medications for psychiatric out- or inpatients due to e.g. remote follow-up (Lignou, Greenwood, Sheehan, & Wolfe, 2022; Segenreich, 2022) and an increased risk for worse outcomes due to barriers in accessing health services timely was often highlighted, particularly for people with pre-existing mental health conditions and people from marginalized populations (i.e., black, indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC), refugees, migrants and prisoners) (Cabrera, Karamsetty, & Simpson, 2020; Fornaro et al., 2021; Lemieux et al., 2020; Murphy et al., 2021). Concerning inpatient mental health care, reduced access to emergency departments and (voluntary) admissions in psychiatric hospitals or self-harm/suicide were mentioned by multiple reviews (k = 9). Other reviews concluded increased psychiatric hospitalization rates (e.g. for eating disorders) or a mixture of increased or decreased emergency departments visits due to suicidal behaviour (Devoe et al., 2022; John et al., 2021; Samji et al., 2021; Steeg et al., 2022; Tuczyńska, Matthews-Kozanecka, & Baum, 2021). Shorter stay or earlier discharge or release from inpatient mental health care facilities were also frequently mentioned disruptions in multiple reviews (k = 9). Group- and external activities and family visits were often suspended and isolation increased in inpatient care or in secure settings (k = 7). Reviews of primary study-findings published in 2020 did not synthesize different findings in terms of disruptions from those of study-findings published in 2021 or early 2022 (see Table 1).

3.5. Adaptations to mental health care services during the pandemic

As shown in Table 1, in the majority of reviews (k = 32) the main adaptation to the pandemic was implementing sTMH interventions for outpatient or community care (i.e. consultation and counseling of psychotherapy or psychotropic medication prescriptions and follow-ups through telephone or video-conferencing platforms). Earlier in the pandemic, implementation of aVMH care appeared mostly limited to online provision of psycho-educational self-help materials (Clemente-Suárez et al., 2021; Meloni, de Girolamo, & Rossi, 2020; Raphael, Winter, & Berry, 2021; Yue et al., 2020) or clinical decision assessment tools through internet or e-mail (Abd-Alrazaq et al., 2021; Fornaro et al., 2021). Few reviews reported implementation of a combination of both sTMH care and aVMH tools or interventions. Transition to aVMH interventions such as i-CBT or psychosocial support apps for healthcare workers or recovering COVID-19 patients, appeared much less prevalent and often conducted later in the pandemic (Bertuzzi et al., 2021; Hatami et al., 2022; Soklaridis, Lin, Lalani, Rodak, & Sockalingam, 2020). Reviews examining uptake of sTMH care noted, after an initial slight decrease in appointments, an increase in remote therapy sessions and consultations even beyond pre-pandemic levels, with better adherence and decreased no-shows (Li et al., 2021; Siegel, Zuo, Moghaddamcharkari, McIntyre, & Rosenblat, 2021). In general, accessibility in more vulnerable patient populations and in those needing a support person present to facilitate remote sessions were found to be more limited. In these instances, telephone calls were seen as the second best solution, particularly for people of low SES (Socio-Economic Status) (Li et al., 2021; Selick et al., 2021; Siegel et al., 2021).

3.6. Barriers, facilitators and appraisal of adapted mental health services

Our findings in terms of barriers and facilitators of the transition to sTMH and aVMH care services are structured according to the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR (Damschroder et al., 2009);) in Table 2 (findings from k = 28 reviews). In terms of intervention characteristics, sTMH designs generally improved scheduling, time efficiency and treatment adherence during the pandemic although certain populations have been more difficult to reach (e.g. in low and middle income countries (LMICs) or economically disadvantaged groups). Synchronous and asynchronous designs that lack non-verbal cues (e.g. telephone, guided apps) were evaluated negatively, particularly for people with severe mental problems. Lack of cultural and contextual adaptations of aVMH interventions was found to be a barrier to implementation in LMICs, although the adaptability for physical activity or mindfulness apps was evaluated positively during the pandemic. Effectiveness of the sTMH and aVMH interventions during the pandemic in the reviews was not based on meta-analytic findings but these were evaluated to be effective, feasible and acceptable based on interviews or surveys among professionals and patients, particularly for (early prevention of) common mental health disorders and for people already receiving pre-COVID mental health care. aVMH interventions were evaluated as particularly effective in well-selected motivated patients.

Table 2.

Findings telemental health (TMH) applications (video-conferencing and telephone) and digital mental health intervention tools (VMH) (e.g. apps, social media platforms).

| CFIR domain |

Barriers/negative appraisals |

Reviews |

Facilitators/positive appraisals |

Reviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention characteristics | ||||

| Design (e.g. guided vs unguided; scalability, fidelity, adaptability) | TMH/VMH: designs (phone, guided apps) lack non-verbal cues. Instant chat messages throughout the pandemic too limited for people with severe mental problems (eating disorders); TMH: videoconferencing preferred over audio/telephone | (Appleton et al., 2021; Ardekani et al., 2021; Devoe et al., 2022) | VMH: adaptability (e.g. contextual and cultural) to aim at physical activity, relaxation, mindfulness. | (Keyes et al., 2022; Soklaridis et al., 2020) |

| TMH: improves scheduling of consultations and counseling; time efficient; reduces consultation time. | (Ardekani et al., 2021; Bertuzzi et al., 2021; Keyes et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021; Selick et al., 2021) | |||

| TMH: difficulties to reach all populations (e.g. new patients; people in LMICs; economically disadvantaged) | (Appleton et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Tuczyńska et al., 2021) | VMH: quality and usability of e-packages/social media platform for healthcare workers | (Drissi et al., 2021) | |

| VMH: lack of cultural or contextual adaptations (e.g. in LMICs) | (Soklaridis et al., 2020) | TMH care increases treatment adherence/less no-shows | (Ali et al., 2021; Lemieux et al., 2020) | |

| Effectiveness/trialability (appraisals often not based on meta-analyses of RCTs) | VMH: Questionable quality of digital mental health tools (e.g. apps); not effective when used as a standalone therapy. | (Hatami et al., 2022; Murphy et al., 2021) | TMH evaluated as (cost-) effective and feasible/acceptable | (Ali et al., 2021; Ardekani et al., 2021; Bertuzzi et al., 2021; Hatami et al., 2022; Keyes et al., 2022; Lemieux et al., 2020; Linardon et al., 2022 ; Murphy et al., 2021; Selick et al., 2021) |

| TMH/VMH: lack of (long-term) effectiveness studies during COVID-19 | (Abd-Alrazaq et al., 2021; Appleton et al., 2021; Lignou et al., 2022; Thenral & Annamalai, 2020) | TMH: effective evaluation for (early stage of) common mental health disorders | (Abraham, Jithesh, et al., 2021; Chiesa et al., 2021; Mohammadzadeh et al., 2022) | |

| TMH care evaluated as not effective for prevention and rehabilitation care. | (Abraham, Jithesh, et al., 2021) | TMH versus VMH: therapist-guided online therapies more efficacious in reducing depression and anxiety than self-help internet-based treatment or apps. | (Hatami et al., 2022) | |

| VMH: evaluated as being effective for marginalized populations | (Abraham, Jithesh, et al., 2021) | |||

| TMH/VMH effective during COVID (e.g. people already receiving care/with established therapeutic relationship) | (Appleton et al., 2021; Keyes et al., 2022; Linardon et al., 2022 ; Selick et al., 2021) | |||

| VMH (e.g. iCBT) more effective in selected highly motivated patients | (Keyes et al., 2022) | |||

|

Characteristics of individuals involved: | ||||

| Practioners:beliefs, perceptions, knowledge, and self-efficacy in terms of TMH | TMH/VMH: lack of technological literacy and experience in providers | (Bertuzzi et al., 2021; Cabrera et al., 2020; Narvaez, 2022; Siegel et al., 2021) | TMH increases access for young people with mental health problems (de-stigmatizing) | (Keyes et al., 2022) |

| TMH/VMH: concerns about therapeutic relationship/impersonal | (Appleton et al., 2021; Kane et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021; Meloni et al., 2020; Selick et al., 2021; Siegel et al., 2021; Thenral & Annamalai, 2020; Tuczyńska et al., 2021) | Limitations of TMH/VMH less important in medication consultations compared to psychotherapy | (Segenreich, 2022) | |

| TMH: reluctance to use because desire for face-to-face or lack of confidence | (Ardekani et al., 2021; Baumgart et al., 2021; Narvaez, 2022) | TMH: more control over time-schedule | (Keyes et al., 2022; Narvaez, 2022) | |

| TMH: requires more concentration; screen fatigue | (Appleton et al., 2021; Keyes et al., 2022; Siegel et al., 2021) | |||

| TMH: missing essential psychological cues | (Drissi et al., 2021; Siegel et al., 2021) | |||

| TMH: intercultural communication and language | (Keyes et al., 2022) | |||

| TMH: ethical concerns | (Kane et al., 2022) | |||

| TMH: inadequate information to support diagnosis | (Li et al., 2021) | |||

| TMH/VMH: increases pre-existing health inequalities | (Keyes et al., 2022) | |||

| TMH/VMH: perceived inefficacy | (Abraham, Jithesh, et al., 2021) | |||

| Participants:beliefs, perceptions, knowledge, and self-efficacy | TMH/VMH: lack of technological literacy/skills (e.g. cognitively impaired, elderly, young, low SES) | (Abd-Alrazaq et al., 2021; Baumgart et al., 2021; Murphy et al., 2021; Selick et al., 2021; Siegel et al., 2021) | Patient satisfaction TMH for eating disorders | (Devoe et al., 2022) |

| VMH: low literacy in general (e.g. for implementation in LMICs) | (Soklaridis et al., 2020) | Patient satisfaction TMH higher than face-to-face | (Keyes et al., 2022) | |

| Concerns over efficacy | (Abraham, Jithesh, et al., 2021; Meloni et al., 2020) | |||

| Limited access or availability to use the TMH and VMH technology (WiFi, webcam, smartphone) | (Abraham, Jithesh, et al., 2021; Appleton et al., 2021; Devoe et al., 2022; Siegel et al., 2021) | Increased anonymity | (Thenral and Annamalai, 2020) | |

| Perceptions of low efficacy/effectiveness | (Murphy et al., 2021) | Willingness of users | (Murphy et al., 2021) | |

| Increases pre-existing (digital) inequalities | (Abraham, Jithesh, et al., 2021; Murphy et al., 2021) | |||

| Unwillingness/low motivation to participate in TMH or VMH | (Abraham, Jithesh, et al., 2021; Drissi et al., 2021; Selick et al., 2021) | |||

| TMH/VMH: Distractions/less concentration | (Li et al., 2021) | |||

| TMH/VMH: Perception of being impersonal/preference for face-to-face/low satisfaction | (Ardekani et al., 2021; Hatami et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021; Linardon et al., 2022) | |||

| TMH does not replace face-to-face for severe mental health problems (e.g. eating disorders) | (Gao et al., 2022) | |||

| Inner setting: | ||||

| Specific organization or setting in which a TMH/VMH will be deployed (e.g. clinic led communication, guidelines, organizational support). | Lack of organizational support for technological implementation/no support person to manage technology | (Murphy et al., 2021; Selick et al., 2021; Tuczyńska et al., 2021) | Organizational (technical) support (second person to assist) | (Ardekani et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021) |

| Time constraints to use TMH and VMH due to competing tasks COVID-19 | (Narvaez, 2022; Siegel et al., 2021) | Guidelines available from (international) professional bodies | (Appleton et al., 2021; Segenreich, 2022) | |

| TMH or VMH not made available in organizations | (Murphy et al., 2021) | Decrease of waiting lists | (Bertuzzi et al., 2021) | |

| Lack of equipment for TMH virtual platforms Inadequate IT infrastructure |

(Keyes et al., 2022; Mohammadzadeh et al., 2022; Selick et al., 2021; Siegel et al., 2021) | Good quality of internet Computer in private area |

( Selick et al., 2021) |

|

| Outer setting: | ||||

| Patient needs accurately known and prioritized by the organization (e.g. payment and funding; privacy and ethics; regulations). | Limited privacy (i.e. home setting patient) | (Drissi et al., 2021; Meloni et al., 2020; Thenral & Annamalai, 2020) | TMH: home setting (valid information socio-environmental determinants) | (Abraham, Jithesh, et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Selick et al., 2021) |

| Confidentiality | (Abraham, Jithesh, et al., 2021; Appleton et al., 2021) | |||

| Security and safety issues/risks | (Murphy et al., 2021) | |||

| Removal regulatory barriers | (Kane et al., 2022) | |||

| Lack/limited access for homeless, technologically uncomfortable (older people), cognitively impaired, young children and people from rural areas. | (Abd-Alrazaq et al., 2021; Cabrera et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021; Yue et al., 2020) | Increased access for marginalized people (from rural areas, migrants, refugees); for people with discontinued care for severe mental health disorders; young people | (Abraham, Jithesh, et al., 2021; Appleton et al., 2021; Gao et al., 2022; Kane et al., 2022) | |

| Lack of knowledge of support needed for technology in organizations | (Keyes et al., 2022) | Time for setting treatment | (Abraham, Jithesh, et al., 2021) | |

| Lack of sufficient funds and resources | (Mohammadzadeh et al., 2022) | Offering geographical flexibility | (Siegel et al., 2021) | |

| Implementation Process: | ||||

| Active efforts undertaken to integrate telemental- and virtual mental health (clinical and technological integration) | Failed integration/acceptance in organizational or national systems | (Abd-Alrazaq et al., 2021) | Organization facilitating access to TMH (in general) | (Abraham, Jithesh, et al., 2021; Ali et al., 2021; Chiesa et al., 2021; Keyes et al., 2022) |

| Lack of insurance coverage | (Appleton et al., 2021; Murphy et al., 2021) | More easily reimbursed | (Baumgart et al., 2021) | |

| Lack of information for staff | (Lemieux et al., 2020) | Delivered at lower costs/increased cost-effectiveness | (Thenral & Annamalai, 2020; Yue et al., 2020) | |

| Limited use or access to available technologies | (Kane et al., 2022; Lemieux et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021) | |||

| Lack of training/shortage of trained or skilled staff | (Keyes et al., 2022; Lemieux et al., 2020; Soklaridis et al., 2020) | Training and education of staff in TMH and guided VMH | (Keyes et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021; Siegel et al., 2021) | |

| Sustainability and adoption (e.g. include more stakeholders) | (Abd-Alrazaq et al., 2021; Chiesa et al., 2021) | Delivery of higher level digital performance | (Kane et al., 2022) | |

Telemental health (TMH) is the use of synchronous therapist contact through telecommunications or videoconferencing technology to provide mental health services. Virtual mental health interventions (VMH) are asynchronous forms of therapist contact through computer, web-based, and mobile delivery of therapy (e.g. apps and chats for training, and web-based peer and social support programs and platforms). Q = total score based on the relevant AMSTAR-2 items.

Barriers in terms of characteristics of practitioners were a lack of technological literacy, experience and confidence, concerns about the therapeutic relationship (e.g. missing psychological cues), being impersonal and becoming easily exhausted when providing sTMH care during the pandemic. Practitioners also perceived sTMH and aVMH interventions as less effective and were concerned about ethics, intercultural communication and about increasing existing health inequalities. Implementation of sTMH and aVMH interventions was found to facilitate access for young people (de-stigmatizing) and for patients receiving psychiatric care (e.g. medication and vital function checks through smartphones). The main barriers in participants were low technological literacy and literacy in general (e.g. in older people, the cognitively impaired, and low SES), limited access or availability of technology (e.g. smartphone, WiFi), even more so in people in LMICs or with low SES. Several beliefs challenging implementation in participants were similar to those of practitioners (e.g., easily distracted, impersonal, not effective, increasing health inequalities and not suitable for severe mental health problems). Patient satisfaction, staying anonymous and greater willingness to use aVMH or sTMH were synthesized as facilitators in only a few reviews.

In terms of inner settings, absence of organizational support for technological implementation of sTMH or aVMH due to a lack of technological equipment, inadequate IT infrastructure and time constraints for personnel to properly use these technologies, as well as lack of funding and resources, were often found barriers during COVID-19. Fewer reviews reported positive aspects such as technical support and knowledge from the organization (e.g. good quality internet, computer in private area and (user-)guidelines) during COVID-19. Organizational barriers in terms of the outer setting (Damschroder et al., 2009) (i.e. patients using sTMH or aVMH) were limited confidentiality, other safety/security issues and lack of privacy for the patient. Visibility of the home environment was however also found to be a facilitator of using TMH care because of additional insight into socio-environmental determinants. In terms of access to care made available by organizations for subgroups of patients, there were mixed findings on whether the removal of regulatory barriers facilitating access to care. Some had increasing or decreasing access to TMH and VMH care for marginalized or vulnerable populations. Barriers in terms of active implementation processes during the pandemic, revolved around the failed technological integration of sTMH and aVMH care into organizational and national systems, health insurance funding issues and limited sustainability and adoption due to lack of involvement of stakeholders. Furthermore, a lack of (culturally adapted) training and shortage of trained or skilled staff was found to be a barrier, although other reviews presented findings with well-trained staff with a higher level of achievement.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

Adapting to the disruptions of mental health service delivery to address the COVID-19 related increase in mental health problems is of great importance to manage current and future world-wide health care crises, particularly for vulnerable populations and settings (Xiang et al., 2020). This umbrella review identified 38 systematic reviews of overall low to moderate methodological quality that met the inclusion criteria. Nearly all reviews provided narratively synthesized findings based on highly heterogeneously designed studies. Findings of our umbrella review suggest reduced access in 2020 and in 2021 to in-person mental health services in outpatient settings, reduced psychiatric emergency admissions, earlier discharge, cancellations of (group) activities and more isolation in inpatient settings, although exact quantitative data to support these findings is lacking. In response to this general scale-down of face-to-face services, the majority of reviews reported remote delivery of synchronous TMH services in several populations and countries while the implementation of asynchronous VMH interventions lagged behind during the pandemic. Implementation of remote forms of counseling and therapy (e.g. through videoconferencing) facilitated access to care because of its time-efficiency, geographical flexibility and design (i.e., similar to non-remote forms). Implementation was however challenged by several barriers such as the worries of practitioners about their technological skills and lack of experience, and lack of technological literacy and resources in patients, specifically in those with pre-existing health inequalities. A lack of organizational support and knowledge on technological implementation, as well as a lack of resources, funding and guidelines for the adaptation to remote care were also often found barriers. Altogether, this umbrella review demonstrates an overview of the rapidly evolving literature on the implementation of tele- and virtual-mental health care interventions as solutions to pandemic-related disruptions in mental health care provision.

Besides multiple technological barriers for implementation according to several domains of the CFIR framework, a key barrier was the concern of practitioners that they would not be able to establish an effective therapeutic alliance (Appleton et al., 2021; Kane et al., 2022 Kane et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021; Meloni et al., 2020; Selick et al., 2021; Siegel et al., 2021; Thenral & Annamalai, 2020; Tuczyńska et al., 2021). A recent review of different video-conferencing and internet-based psychotherapies, however, showed that independent of communication modalities and the amount of contact, therapeutic alliance ratings were comparable to those found in face-to-face therapy (Berger, 2017). In view of multiple advantages such as flexibility in scheduling the appointments and the increased uptake of tele- and (guided) virtual mental health in later stages of the pandemic, mental health care institutions may continue to serve their patients via tele- or virtual mental health solutions or through a mixture of both by providing blended care even beyond pandemic times (Wind, Rijkeboer, Andersson, & Riper, 2020).

In the transition of face-to-face to tele- or virtual mental health care during the pandemic, many reviews synthesized appraisals of efficacy, (cost-)effectiveness and feasibility and acceptability of tele- or virtual mental health interventions for common mental health disorders (Abraham, Chaabna, et al., 2021; Chiesa, Antony, Wismar, & Rechel, 2021; Hatami et al., 2022; Lemieux et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021; Yue et al., 2020). These findings were often biased because they were based on interviews and surveys reflecting appraisals of professionals sometimes involved in the development or implementation of the new interventions (Ardekani et al., 2021; Baumgart et al., 2021; Bertuzzi et al., 2021; Lemieux et al., 2020; Linardon, Messer, Rodgers, & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, 2022; Siegel et al., 2021). Beliefs among practitioners and patients about low effectiveness of tele- and virtual mental health care interventions were however found to challenge their uptake during the pandemic (Abraham, Jithesh, et al., 2021; Chiesa et al., 2021; Murphy et al., 2021). Some reviews evaluated quantitative findings indicating effectiveness of sTMH and aVMH interventions in terms of a reduction in common mental health problems both during the COVID-19 pandemic and other pandemics (Hatami et al., 2022; Soklaridis et al., 2020). For example, therapist-guided online interventions appeared more efficacious in reducing anxiety and depression than self-help internet based interventions (Hatami et al., 2022). Remote tools that lack non-verbal cues such as asynchronous internet-based or smartphone interventions were more negatively appraised in terms of effectiveness when used as stand-alone treatment for severe mental health disorders (Hatami et al., 2022; Devoe et al., 2022; Murphy et al., 2021) but might be well adaptable and effective for (early prevention of) common mental health disorders and are better scalable throughout communities and populations facing adversity (Abraham, Chaabna, et al., 2021, pp. 1–18; Chiesa et al., 2021).

Building the evidence-base of effectiveness of remotely delivered interventions is important for adoption and sustainability of remotely delivered mental health care in future pandemics. Interestingly, a huge amount of trials during COVID-19 have been conducted to identify physical health treatments for people hospitalized with COVID-19 while only few remote psychosocial interventions to prevent depression and loneliness in susceptible populations were evaluated in trials during the pandemic (Gilbody et al., 2021). Some reviews of the efficacy and clinical utility of specific forms of tele-psychotherapy are available but also lack direct comparisons of face-to-face formats to online or blended psychotherapy formats (van Leeuwen et al., 2021; Cassiello-Robbins 2021). Moreover, reviewing meta-analytic findings of comparative efficacy or effectiveness of remote interventions during the pandemic was beyond the scope of our review (e.g. D'onofrio et al., 2022; Doherty et al., 2021).

Besides the provision of technical integration and support (e.g. guidelines) by organizations as important factors to facilitate the implementation process, training and education of staff in tele- and virtual mental health tools during the pandemic were reported both as barriers and as facilitators of implementation (Keyes et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021; Siegel et al., 2021; Soklaridis et al., 2020). Organizations should provide proper training of practitioners to develop competencies to effectively use tools and facilitate staff to become involved in communities of practice and training of tele- and virtual mental health tools by appointing an internal champion (Schueller & Torous, 2020). Barriers in terms of consumer costs of using sTMH and aVMH interventions (e.g. apps, iCBT), should actively be removed by organizations or (inter)national bodies by providing reimbursement or free products. For example, the WHO has developed a freely available digital intervention that can be adapted for use in settings with different cultural contexts and resource availability (Carswell et al., 2018). Involving champions in organizations as well as stakeholders may help to address the lack of sustainability and adoption of sTMH and aVMH intervention tools (Abd-Alrazaq et al., 2021; Schueller & Torous, 2020).

This is the first umbrella review that provides a complete overview of available literature on mental health access during COVID-19 until now. However, one of the limitations of our umbrella review concerns the inclusion of reviews based on pre-defined inclusion- and exclusion criteria for a broader umbrella review on the impact of COVID-19 on mental health in general (World Health Organization, 2022). Although specific inclusion criteria for the aims on health care access and delivery were defined in the protocol, these criteria may not have stipulated clear enough which systematic review types would have been excluded a priori (Aromataris et al., 2015). Another limitation was the inclusion of systematic or scoping reviews not always clearly designed as such. Although most reviews followed the original PRISMA or PRISMA-ScR statement reporting criteria (Moher et al., 2009; Tricco et al., 2018), the definition of such reviews contains vague terms such as clearly, systematic and explicit (Krnic Martinic, Pieper, Glatt, & Puljak, 2019). Another limitation is the lack of quantitative findings and the narrative analysis.

Although the geographical coverage of primary studies included in the reviews of this umbrella review was rather broad, high income countries were overrepresented. Scaling-up mental health services is an essential component of universal health coverage and should be integrated into the global response and not for high-income countries exclusively. However, findings of most scalable asynchronous VMH interventions were lacking and when available from LMICs, implementation of such interventions appeared very limited (Narvaez, 2022; Soklaridis et al., 2020). This knowledge gap has been extensively reflected on by The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development as well (Patel et al., 2018). Barriers in the implementation of sustainable remotely delivered asynchronous VMH care in LMICs may be even larger because of poor technological literacy, socio-economic inequalities and lack of IT resources in mental health services (Naslund et al., 2019). Nonetheless, the majority of interventions effective in high income countries have also been shown to be effective in LMICs (Morina, Malek, Nickerson, & Bryant, 2017), and findings and recommendations from scaling-up interventions and mental health care programs identified from studies of infectious disease outbreaks other than COVID-19 (e.g. Ebola) also show opportunities to bridge gaps in available mental health care with culturally adapted e-mental health technologies in these low resource settings (Soklaridis et al., 2020).

5. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic poses a continuing challenge on health systems across the world. Our review showed that the disruption of mental health services worldwide and particularly in high-income countries during the pandemic, was characterized by an extensive scale-down of face-to-face outpatient care and reduced admission and earlier discharge of psychiatric inpatients. Existing interventions were rapidly converted into remote synchronous telemental health tools such as videoconferencing platforms, facilitated by the time-efficient and (geographical) flexibility of these interventions. The more scalable asynchronous virtual mental health tools were however implemented less often, later in the pandemic and for specific groups only. Barriers and facilitators in terms of technological and financial integration at organizational or national level, training and programming of remotely delivered interventions, common beliefs and characteristics of practitioners and patients such as technological literacy and resources are important factors to consider for more sustainable adoption of synchronous and particularly asynchronous virtual mental health tools in future pandemics. Finally, research to determine the effectiveness of tele- and virtual mental health interventions to support resilience of diverse populations, including patients and healthcare workers, is a high priority given the uncertainties of current or future pandemics.

Funding

The World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland and the RESPOND project funded under Horizon 2020 – the Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (2014–2020). The content of this article reflects only the authors’ views and the European Community is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

A.B. Witteveen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. S. Young: Investigation, Formal analysis, Project administration. P. Cuijpers: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. C. Barbui: Writing – review & editing. F. Bertolini: Investigation, Formal analysis. M. Cabello: Investigation, Formal analysis. C. Cadorin: Investigation, Formal analysis. N. Downes: Investigation, Formal analysis. D. Franzoi: Investigation, Formal analysis. M. Gasior: Investigation, Formal analysis. A. John: Writing – review & editing, Writing – review & editing. M. Melchior: Writing – review & editing. D. McDaid: Writing – review & editing. C. Palantza: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. M. Purgato: Writing – review & editing. J. Van der Waerden: Investigation, Formal analysis. S. Wang: Investigation, Formal analysis. M. Sijbrandij: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support of dr. Mark van Ommeren and dr. Brandon Gray of the Department of Mental Health and Substance Use, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. We also like to thank Olivia Zurcher for her support in organizing the flow-chart of studies.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2022.104226.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Abd-Alrazaq A., Hassan A., Abuelezz I., Ahmed A., Alzubaidi M.S., Shah U., et al. Overview of technologies implemented during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: Scoping review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2021;23(9) doi: 10.2196/29136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham A., Chaabna K., Doraiswamy S., Bhagat S., Sheikh J., Mamtani R., et al. Human resources for health. BioMed Central Ltd; 2021. Depression among healthcare workers in the eastern mediterranean region: A systematic review and meta-analysis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham A., Jithesh A., Doraiswamy S., Al-Khawaga N., Mamtani R., Cheema S. Telemental health use in the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review and evidence gap mapping. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.748069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali N.A., Khoja A., Kazim F. Role of the telemental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi = Turkish Journal of Psychiatry. 2021;32(4):275–282. doi: 10.5080/u26021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleton R., Williams J., Juan N.V.S., Needle J.J., Schlief M., Jordan H., et al. Implementation, adoption, and perceptions of telemental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2021;23(Issue 12) doi: 10.2196/31746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardekani A., Hosseini S.A., Tabari P., Rahimian Z., Feili A., Amini M., et al. Student support systems for undergraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic narrative review of the literature. BMC Medical Education. 2021;21(1) doi: 10.1186/S12909-021-02791-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris E., Fernandez R., Godfrey G.C., Holly C., Khalil H., Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare. 2015;13(3):132–140. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgart J.G., Kane H., El-Hage W., Deloyer J., Maes C., Lebas M.C., et al. The early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health facilities and psychiatric professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(15) doi: 10.3390/IJERPH18158034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger T. The therapeutic alliance in internet interventions: A narrative review and suggestions for future research. Psychotherapy Research. 2017;27(5):511–524. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2015.1119908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertuzzi V., Semonella M., Bruno D., Manna C., Edbrook‐childs J., Giusti E.M., et al. Psychological support interventions for healthcare providers and informal caregivers during the covid‐19 pandemic: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(Issue 13) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18136939. MDPI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffel V., Van de Velde S., Akvardar Y., Bask M., Brault M.-C., Busse H., et al. Depressive symptoms in higher education students during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of containment measures. The European Journal of Public Health. 2022 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckac026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera M.A., Karamsetty L., Simpson S.A. Coronavirus and its implications for psychiatry: A rapid review of the early literature. Psychosomatics. 2020;61(6):607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.05.018. Psychosomatics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carswell K., Harper-Shehadeh M., Watts S., Hof E. van’t, Ramia J.A., Heim E., et al. Step-by-Step: A new WHO digital mental health intervention for depression. mHealth. 2018;4 doi: 10.21037/MHEALTH.2018.08.01. 34–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassiello-Robbins C., Rosenthal M.Z., Ammirati R.J. Delivering transdiagnostic treatment over telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: Application of the unified protocol. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2021;28(4):555–572. doi: 10.1016/J.CBPRA.2021.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceban F., Nogo D., Carvalho I.P., Lee Y., Nasri F., Xiong J., et al. Association between mood disorders and risk of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(10):1079–1091. doi: 10.1001/JAMAPSYCHIATRY.2021.1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa V., Antony G., Wismar M., Rechel B. COVID-19 pandemic: Health impact of staying at home, social distancing and “lockdown” measures - a systematic review of systematic reviews. Journal of Public Health. 2021;43(Issue 3):E462–E481. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdab102. J Public Health (Oxf) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente-Suárez V.J., Navarro-Jiménez E., Jimenez M., Hormeño-Holgado A., Martinez-Gonzalez M.B., Benitez-Agudelo J.C., et al. Sustainability (Switzerland) Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2021. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic in public mental health: An extensive narrative review. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder L.J., Aron D.C., Keith R.E., Kirsh S.R., Alexander J.A., Lowery J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50/TABLES/1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoe J., D. Han A., Anderson A., Katzman D.K., Patten S.B., Soumbasis A., et al. International journal of eating disorders. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2022. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating disorders: A systematic review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty A., Benedetto V., Harris C., Boland P., Christian D.L., Hill J., et al. The effectiveness of psychological support interventions for those exposed to mass infectious disease outbreaks: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):592. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03602-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’onofrio G., Trotta N., Severo M., Iuso S., Ciccone F., Prencipe A.M., et al. Psychological interventions in a pandemic emergency: A systematic review and meta-analysis of SARS-CoV-2 studies. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022;11(11):3209. doi: 10.3390/jcm11113209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drissi N., Ouhbi S., Marques G., De La Torre Díez I., Ghogho M., Janati Idrissi M.A. A systematic literature review on e-mental health solutions to assist health care workers during COVID-19. Telemedicine and E-Health. 2021;27(6):594–602. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt D., Steptoe A., Bu F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in england: A longitudinal observational study. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(2):141–149. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30482-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filho V., Araújo A., Fernandes M., Pillon S. Adoption of measures by psychiatric hospitals to prevent SARS-CoV-2. Annales Medico-Psychologiques. 2021;180(2) doi: 10.1016/j.amp.2021.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornaro M., De Prisco M., Billeci M., Ermini E., Young A.H., Lafer B., et al. Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for people with bipolar disorders: A scoping review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;295:740–751. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.091. J Affect Disord. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P., Radua J. Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews. Evidence-Based Mental Health. 2018;21(3):95–100. doi: 10.1136/EBMENTAL-2018-300014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganjali R., Jajroudi M., Kheirdoust A., Darroudi A., Alnattah A. Telemedicine solutions for clinical care delivery during COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/FPUBH.2022.937207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Bagheri N., Furuya-Kanamori L. Journal of public health (Germany) 2022. Has the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown worsened eating disorders symptoms among patients with eating disorders? A systematic review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody S., Littlewood E., Gascoyne S., McMillan D., Ekers D., Chew-Graham C.A., et al. Mitigating the impacts of COVID-19: Where are the mental health trials? The Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(Issue 8):647–650. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00204-2. Lancet Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale T., Angrist N., Goldszmidt R., Kira B., Petherick A., Phillips T., et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker) Nature Human Behaviour. 2021;5(4):529–538. doi: 10.1038/S41562-021-01079-8. 2021 5:4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatami H., Deravi, Niloofar D., | Bardia, Zangiabadian, | Moein, Hashem. Amir. Bonjar S., et al. Tele-medicine and improvement of mental health problems in COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Holmes E.A., O'Connor R.C., Perry V.H., Tracey I., Wessely S., Arseneault L., et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. Lancet Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Huang L., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Gu X., et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study. The Lancet. 2021;397:220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. 10270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humer E., Probst T. Provision of remote psychotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Digital Psychology. 2020;1(2):27–31. doi: 10.24989/DP.V1I2.1868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis J.P.A. Integration of evidence from multiple meta-analyses: A primer on umbrella reviews, treatment networks and multiple treatments meta-analyses. Canadian Medical Association Journal : Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de l’Association Medicale Canadienne. 2009;181(8):488–493. doi: 10.1503/CMAJ.081086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John A., Eyles E., Webb R.T., Okolie C., Schmidt L., Arensman E., et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on self-harm and suicidal behaviour: Update of living systematic review [version 2; peer review: 1 approved, 2 approved with reservations] F1000Research. 2021;9:1–44. doi: 10.12688/F1000RESEARCH.25522.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane H., Gourret Baumgart J., El-Hage W., Deloyer J., Maes C., Lebas M.-C., et al. Opportunities and challenges for professionals in psychiatry and mental health care using digital technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic: Systematic review. JMIR Human Factors. 2022;9(1) doi: 10.2196/30359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes B., McCombe G., Broughan J., Frawley T., Guerandel A., Gulati G., et al. Enhancing GP care of mental health disorders post-COVID-19: A scoping review of interventions and outcomes. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine. 2022:1–17. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2022.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krnic Martinic M., Pieper D., Glatt A., Puljak L. Definition of a systematic review used in overviews of systematic reviews, meta-epidemiological studies and textbooks. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0855-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Singh G.K. Monthly trends in access to care and mental health services by household income level during the COVID-19 pandemic, United States, april: December 2020. Health Equity. 2021;5(1):770–779. doi: 10.1089/HEQ.2021.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen H., Sinnaeve R., Witteveen U., Van Daele T., Ossewaarde L., Egger J.I.M., et al. Reviewing the availability, efficacy and clinical utility of Telepsychology in dialectical behavior therapy (Tele-DBT) Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation. 2021;8(1) doi: 10.1186/S40479-021-00165-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux A.J., Dumais Michaud A.A., Damasse J., Morin-Major J.K., Nguyen T.N., Lesage A., et al. Management of COVID-19 for persons with mental illness in secure units: A rapid international review to inform practice in québec. Victims and Offenders. 2020;15(7–8):1337–1360. doi: 10.1080/15564886.2020.1827111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Glecia A., Kent-Wilkinson A., Leidl D., Kleib M., Risling T. Psychiatric quarterly. 2021. Transition of mental health service delivery to telepsychiatry in response to COVID-19: A literature review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lignou S., Greenwood J., Sheehan M., Wolfe I. Changes in healthcare provision during covid-19 and their impact on children with chronic illness: A scoping review. Inquiry : A Journal of Medical Care Organization, Provision and Financing. 2022;59 doi: 10.1177/00469580221081445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardon J., Messer M., Rodgers R.F., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M. International journal of eating disorders. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2022. A systematic scoping review of research on COVID-19 impacts on eating disorders: A critical appraisal of the evidence and recommendations for the field. Vol. 55, Issue 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield K.E., Mathur R., Tazare J., Henderson A.D., Mulick A.R., Carreira H., et al. Indirect acute effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health in the UK: A population-based study. The Lancet Digital Health. 2021;3(4):e217–e230. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00017-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloni S., de Girolamo G., Rossi R. Covid-19 and mental health services in europe. Epidemiologia e Prevenzione. 2020;44(5–6):383–393. doi: 10.19191/EP20.5-6.S2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minozzi S., Saulle R., Amato L., Davoli M. [Impact of social distancing for covid-19 on young people: Type and quality of the studies found through a systematic review of the literature] Recenti Progressi in Medicina. 2021;112(5):E51–E67. doi: 10.1701/3608.35881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadzadeh Z., Maserat E., Davoodi S. Role of Telemental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Early Review. 2022;16(1) doi: 10.5812/ijpbs.116597. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Altman D., Antes G., et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PMED.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews. 2015;4(1):148–160. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno C., Wykes T., Galderisi S., Nordentoft M., Crossley N., Jones N., et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(9):813–824. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]