Abstract

Background

The aim of the study was to explore the treatment outcomes and prognostic factors for patients with previously irradiated but unresectable recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (rHNSCC) treated by stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) plus cetuximab at a single institute in Taiwan.

Methods

From February 2016 to March 2019, 74 patients with previously irradiated but unresectable rHNSCC were treated with SBRT plus cetuximab. All patients received irradiation to the gross tumor and/or nodal area with 40–50 Gy in five fractions, with each fraction interval ≥2 days over a 2-week period by using the CyberKnife M6 machine. An18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan was performed before treatment for treatment target delineation (n = 74) and 2 months later for response evaluation (n = 60). The median follow-up time was 9 months (range 1–36 months).

Results

The treatment response rate was complete response: 25.0%, partial response: 41.7%, stable disease: 11.7%, and progressive disease: 21.7% based on the criteria of the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (n = 72) and complete metabolic response: 21.7%, partial metabolic response: 51.7%, stable metabolic disease: 13.3%, and progressive metabolic disease: 13.3% based on PET-CT (n = 60), respectively. The 1-/2-year overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) rates were 42.8%/22.0% and 40.5%/19.0%, respectively. In the logistic regression model, a re-irradiation interval >12 months was observed to be the only significant prognostic factor for a favorable treatment response. In the Cox proportional hazards model, a re-irradiation interval >12 months and gross tumor volume (GTV) ≦ 50 ml were favorable prognostic factors of OS and PFS.

Conclusion

SBRT plus cetuximab provides a promising salvage strategy for those patients with previously irradiated but unresectable rHNSCC, especially those with a re-irradiation interval >12 months or GTV ≦ 50 ml.

Keywords: Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, Stereotactic body radiotherapy, Cetuximab, Gross tumor volume, Re-irradiation, PET-CT

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

In contrast to conventional fractionated RT, SBRT allows for more precise dose distribution by the stereotactic technique and delivers a large dose per fraction to the treatment target. Several reports have revealed that the combination of SBRT plus cetuximab is a safe and promising salvage strategy for unresectable rHNSCC.

What this study adds to the field

SBRT plus cetuximab has seldom been reported for patients in Asian countries. In this study, we observed SBRT plus cetuximab provides a promising salvage strategy for those patients with previously irradiated but unresectable rHNSCC, especially those with a re-irradiation interval > 12 months or GTV ≦ 50 ml.

Introduction

The treatment strategies for locally recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (rHNSCC) in a previously irradiated field remain diverse. Although salvage surgery is the treatment modality of choice for resectable disease [1], many patients present with unresectable tumor status, such as proximity to vital structures or high comorbidities rendering surgery unfeasible [2]. In the setting of unresectable and previously irradiated rHNSCC, the treatment options might include re-irradiation, chemotherapy, target therapy or immunotherapy [3].

The advent of modern radiotherapy (RT), such as intensity modulated RT (IMRT), particle therapy or stereotactic body RT (SBRT), has reinvigorated interest in the use of RT for the salvage treatment of rHNSCC. SBRT has been shown to be a safe technique for previously irradiated but unresectable rHNSCC in the clinical setting [4]. In contrast to conventional fractionated RT, SBRT allows for more precise dose distribution by the stereotactic technique and delivers a large dose per fraction to the treatment target with short treatment duration. Although a lower total dose is delivered over the course of SBRT, a biologically equivalent effective dose to the tumor can be achieved; moreover, low toxicities for SBRT have been reported in the treatment of rHNSCC [5,6].

Cetuximab, a humanized murine monoclonal antibody against the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), has been shown to increase locoregional control and improve overall survival (OS) when compared to RT alone for locally advanced HNSCC with improved survival outcomes when combined with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic HNSCC [7,8]. Several reports from Western countries have revealed that the combination of SBRT with concurrent cetuximab is a safe and promising salvage strategy for unresectable rHNSCC [[9], [10], [11], [12]]. As far as we know, such clinical experience has seldom been reported for patients in Asian countries. In this study, we evaluated the treatment outcomes and prognostic factors for patients with previously irradiated but unresectable rHNSCC treated by SBRT plus cetuximab at a single institute in Taiwan.

Materials and methods

Study design

The study was a retrospective study of patients who were treated using SBRT for recurrent, unresectable and previously irradiated HNSCC at Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital from February 2016 to March 2019. The study was approved by the institutional review board, and all patients provided signed written informed consent prior to treatment. Patients excluded from this analysis included those with distant metastases, and patients who did not complete the prescribed treatment. All patients received an 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan before treatment for tumor staging and target delineation of SBRT. Tumor status was reviewed and a treatment decision regarding SBRT was made at the multidisciplinary clinic of the institute.

Technique of SBRT

A thermoplastic head and neck mask was made for immobilization. The CT simulator was used to scan the patient at a slice thickness of 1.25 mm and computerized optimization was used with fusion of PET-CT with the CT images to accurately delineate the gross tumor volume (GTV) and organs at risk (OARs). SBRT was delivered by the CyberKnife M6 machine equipped with the IRIS or an InCise MLC system. Treatment plans were created using Multiplan Treatment Planning Software (MTPS; version 5.1.3; Accuray Inc., Chesapeake Terrace, Sunnyvale, CA). The values of GTV in the study were calculated from the treatment planning system. The planning target volume (PTV) was created for an additional three-dimensional 1.0–3.0 mm safe margin of GTV to take into account motion uncertainties and setup problems of the patients. The prescribed doses were 8–10 Gy per fraction for five fractions with each fraction interval ≥2 days over a 2-week period. The prescribed isodose line was 80%, and the planning goal for the PTV was application of a minimum dose to >95% of the GTV. During the treatment, near real-time digital X-ray images were obtained for each patient to confirm and ensure the accuracy of the treatment positioning and target location. Fig. 1 demonstrates the dosimetric distribution of a case of rHNSCC in the left upper neck area.

Fig. 1.

The dosimetric distribution of a case with rHNSCC at left upper neck area treated by stereotactic body radiotherapy planned with Multiplan Treatment Planning Software and delivered using CyberKnife M6 machine.

Combination of cetuximab

Cetuximab was given via intravenous infusion for 120 min with a loading dose of 400 mg/m2 on day one of SBRT and then 250 mg/m2 on day 8 and day 15. All patients were pre-medicated with an antihistamine or dexamethasone prior to each dose of cetuximab.

Response assessment

The assessment of tumor response was performed according to the criteria of the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.0 by head and neck MRI/CT and/or PET-CT 1–2 months after completion of the SBRT course. The metabolic response to PET was based on standardized uptake values (SUVs). The maximum SUV value (SUVmax) in the tumor region was measured before and after therapy. Response was assessed by comparison between pre- and post-treatment PET scans according to the criteria proposed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) recommendations [13], which were categorized as progressive metabolic disease (PMD), stable metabolic disease (SMD), partial metabolic response (PMR), and complete metabolic response (CMR). CMR is defined when the SUV of the tumor is equivalent to the background or there is complete resolution of FDG avidity; PMR is defined when the SUV is decreased by ≥ 15%; SMD is defined as an SUV increase of <25% or decrease of <15%; and PMD is defined as an SUV increase of ≥25% or new FDG-avid areas.

Statistical analysis

All patients received regular follow-up examinations or were followed until death. The descriptive analysis was summarized using frequencies, percentages, and medians (ranges). For analysis of treatment response, patients with complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) versus stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD) based on the RECIST criteria was defined as the positive response, and patients with metabolic response >50% versus ≤50% on PET-CT as a positive metabolic response. Continuous variables were categorized into groups that were clinically logical. Subsequently, multivariate analysis was performed using the logistic regression method. The survival time and time intervals for disease progression were calculated from the end of SBRT. The actuarial estimates of OS and progression-free survival (PFS) were analyzed by using the Kaplan-Meier method. The statistical difference between survival functions was further estimated through the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was conducted to explore the potential predictors. For all analyses, two-sided tests of significance were used, with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Two cases did not complete the prescribed five fractions. The treatment was stopped in one patient after receiving two fractions because of aspiration pneumonia, and the other patient discontinued the treatment after one fraction because he could not tolerate the long time needed to deliver the beam (about 1 h) with a tight mask on his face. In total, 74 patients were included in the study. The patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 58 years (range 37–85 years). Most patients (91.9%) were male and had a history of smoking (77.0%) or betel nut chewing (68.9%). The primary cancer sites for rHNSCC were the oral cavity (47.3%), oropharynx (29.7%), and hypopharynx or larynx (23.0%). The original cancer stage was stage I: 1 (1.4%) patient, II: 2 (2.8%) patients, III: 14 (18.8%) patients, IVa: 37 (50.0%) patients, and IVb: 20 (27.0%) patients. The recurrent cancer stage was rcIVa: 8 (10.8%) patients and rcIVb: 66 (89.2%) patients. Many patients had received prior surgery (89.2%) or chemotherapy (100%). In the immunohistochemistry study, all patients were positive for EGFR and 14 (18.9%) patients were positive for p-16.The median dose of previous irradiation was 70 Gy (range 60–120 Gy). The interval between previous RT and SBRT ranged 1–145 months (median 22 months) and 47 (63.5%) patients had an interval >12 months. The sites of SBRT were at the tumor (51.4%), nodes (25.6%), or both (23.0%). The median value of GTV was 64.5 ml (range 9.0–358.7 ml). The median follow-up time was 9 months (range 1–36 months) [Table 2].

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| Median | 58 |

| Range | 37–85 |

| Gender, male/female | 68/6 |

| Smoking, yes | 57 (77.0%) |

| Betel nut chewing, yes | 51 (68.9%) |

| EGFR, positive | 74 (100%) |

| P-16 | |

| Positive | 14 (18.9%) |

| negative | 51 (68.9%) |

| unknown | 9 (12.2%) |

| Primary cancer sites | |

| Oral cavity | 35 (47.3%) |

| Oropharynx | 22 (29.7%) |

| Hypopharynx or larynx | 17 (23.0%) |

| Original AJCC stage | |

| I | 1 (1.4%) |

| II | 2 (2.8%) |

| III | 14 (18.8%) |

| IVa | 37 (50.0%) |

| IVb | 20 (27.0%) |

| Recurrent AJCC stage | |

| rcIVa | 8 (10.8%) |

| rcIVb | 66 (89.2%) |

| Previous surgery | 66 (89.2%) |

| Previous chemotherapy | 74 (100%) |

| Previous RT dose, Gy | |

| Median | 70 |

| Range | 60–120 |

| Re-irradiation interval, months | |

| Median | 22 |

| Range | 1–145 |

| SBRT, sites | |

| T | 38 (51.4%) |

| N | 19 (25.6%) |

| T + N | 17 (23.0%) |

| SBRT, total dose (Gy) | |

| Median | 40 |

| Range | 40–50 |

| SBRT, dose per fraction (Gy) | |

| Median | 8 |

| Range | 8–10 |

| GTV, median (range), ml | 64.5 (9.0–358.7) |

| ≦50 | 25 (33.8%) |

| 50-100 | 22 (29.7%) |

| >100 | 27 (36.5%) |

| PET-CT, delayed SUVmax | |

| Median | 10.6 |

| Range | 3.3–22.7 |

Abbreviations: RT: radiotherapy; SBRT: stereotactic body radiotherapy; T: gross tumor area; N: gross nodal area; GTV: gross tumor volume; PET-CT: Positron emission tomography–computed tomography scans; AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging System, 8th edition.

Table 2.

Treatment response based on RECIST or PET.

| Response | RECIST | PET |

|---|---|---|

| CR/CMR | 15 (25.0%) | 13 (21.7%) |

| PR/PMR | 37 (41.6%) | 31 (51.7%) |

| SD/SMD | 7 (11.7%) | 8 (13.3%) |

| PD/PMD | 13 (21.7%) | 8 (13.3%) |

| Total | 72 (100%) | 60 (100%) |

Abbreviations: RECIST: Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; PET: positron emission tomography; CR: complete response; CMR: complete metabolic response; PR: partial response; PMR: partial metabolic response; SD: stable disease; SMD: stable metabolic disease; PD: progressive disease; PMD: progressive metabolic disease. The response of PET is based on the criteria of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) recommendations [13].

Response after SBRT

Two patients who did not undergo the imaging study post-SBRT were not evaluable in terms of the response. Among the 72 patients who were evaluable for the response after SBRT, the response rates meeting the RECIST criteria were CR: 25.0%, PR: 41.7%, SD: 11.7%, and PD: 21.7%. Sixty (83.3%) patients received a PET-CT scan approximately 2 months after SBRT. Of the 60 cases evaluable for the metabolic treatment response, the response rates according to the EORTC recommendations were CMR: 21.7%, PMR: 51.7%, SMD: 13.3%, and PMD: 13.3%. Fig. 2 depicts an example of a case with a metabolic complete response after treatment. The kappa value was 0.61 (p < 0.01) for the agreement between the RECIST and PET-CT for the 60 patients. Assessing the prognosticators of CR + PR or metabolic response >50% by multivariate analysis, the re-irradiation interval was the only statistically significant prognostic factor [Table 3]. The response rate (CR + PR) was 65.2% vs. 26.9% (p = 0.003), and the metabolic response rate >50% was 55.9% vs. 11.1% (p = 0.003) for those with a re-irradiation interval >12 months compared with the other group. The response rate was independent of age, gender, smoking and betel nut chewing history, p-16 status, initial cancer site, original AJCC stage, recurrent AJCC stage, sites of SBRT, dose of SBRT, GTV, or grading of acne formation.

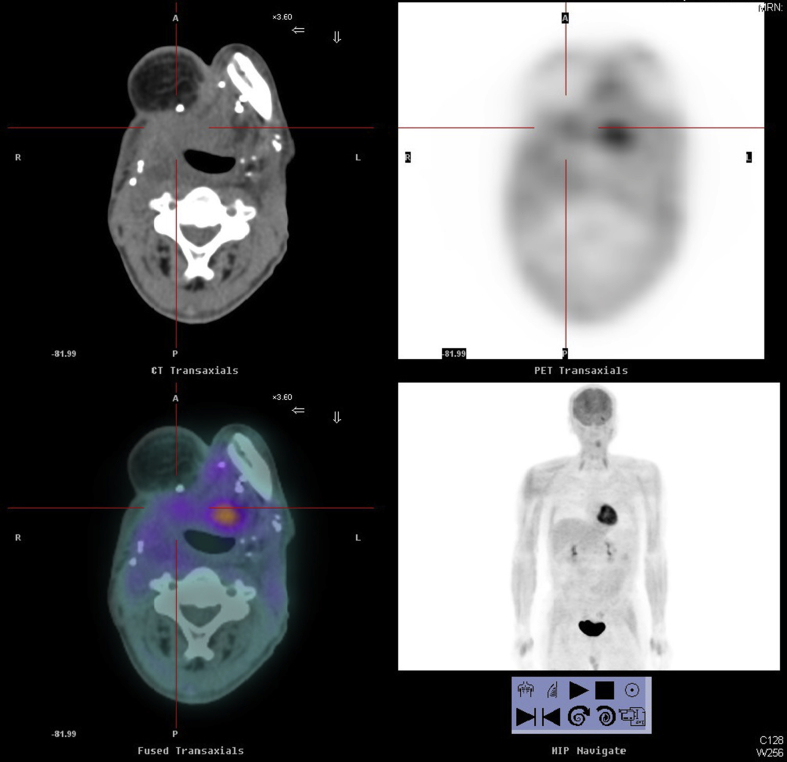

Fig. 2.

Positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) scans of a case with rHNSCC at right tongue base area before (A) and after (B) treatment.

Table 3.

Logistic regression model to predict variables associated with treatment response based on RECIST or PET.

| RECIST (CR + PR) |

PET (metabolic response>50%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Variables | ||||

| Age: >58 years (Ref:≦58 years) | 0.7 (0.2–2.2) | 0.51 | 0.7 (0.2–2.7) | 0.57 |

| Gender: female (Ref: male) | 0.1 (0.1–1.9) | 0.12 | 0.1 (0.1–5.1) | 0.89 |

| Smoking: yes (Ref: no) | 1.4 (0.2–10.8) | 0.75 | 4.8 (0.4–9.9) | 0.22 |

| Betel nut: yes (Ref: no) | 0.3 (0.1–1.8) | 0.18 | 0.3 (0.1–2.2) | 0.22 |

| P-16: positive (Ref: negative or unknown) | 1.1 (0.2–5.7) | 0.88 | 2.9 (0.3–6.1) | 0.48 |

| Primary cancer sites: others (Ref: oral cavity) | 2.0 (0.6–7.3) | 0.27 | 0.6 (0.1–3.0) | 0.57 |

| Original AJCC stage: IV (Ref: I-III) | 0.7 (0.2–3.1) | 0.65 | 0.4 (0.1–2.3) | 0.31 |

| Recurrent AJCC stage: rcIVb (Ref: rcIVa) | 2.7 (0.7–5.9) | 0.22 | 5.1 (0.3–3.2) | 0.27 |

| Re-irradiation interval: ≦12 months (Ref: >12 months) | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) | 0.006 | 0.1 (0.1–0.3) | 0.003 |

| SBRT sites: N or T + N (Ref: T) | 2.4 (0.6–9.5) | 0.21 | 3.8 (0.8–8.5) | 0.10 |

| SBRT dose: >40 Gy (Ref: 40 Gy) | 1.4 (0.4–4.9) | 0.57 | 4.9 (0.8–3.8) | 0.17 |

| Gross tumor volume: >50 ml (Ref:≦50 ml) | 0.6 (0.2–2.1) | 0.34 | 0.3 (0.1–1.1) | 0.17 |

| Acne formation: ≧grade 2 (Ref: grade 0–1) | 1.0 (0.2–4.4) | 0.99 | 0.7 (0.1–4.1) | 0.73 |

Abbreviations: RECIST: Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; PET: positron emission tomography; OR: Odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; Ref: reference; SBRT: stereotactic body radiotherapy; T: gross tumor area; N: gross nodal area; SBRT: stereotactic body radiotherapy; AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging System, 8th edition.

Survival and patterns of failure

At the last follow-up, 50 (67.6%) patients had died of the disease, seven (9.4%) patients had died of other medical diseases, 11 (14.9%) patients were alive without disease progression, and 6 (8.1%) patients were alive with disease progression. Fifty patients (67.5%) had locoregional failure, 10 (13.5%) patients had distant failure, and eight (10.9%) patients had both locoregional and distant failure. There were six (8.1%) patients in complete remission after treatment, with a long-term complete response of more than 2 years. The median OS months and 1- and 2-year OS rates were 9 months (95% CI: 6.5–11.5) and 42.8% and 22.0%, respectively. The median PFS months and 1- and 2-year PFS rates were 9 months (95% CI: 6.9–11.1) and 40.5% and 19.0%, respectively. In the Cox proportional hazards model, we observed that the re-irradiation interval and GTV were statistically significant prognosticators of OS and PFS [Table 4]. The median OS and PFS months for those with a re-irradiation interval >12 months were 16.9 (13.2–20.7) and 15.4 (12.2–18.7), respectively, compared with 9.4 (6.6–12.2) and 9.0 (6.4–11.7) for those with a re-irradiation interval ≤12 months (p = 0.007).The median OS and PFS months for those with GTV ≦ 50 ml were 21.9 (16.1–27.8) and 19.1 (13.9–24.4), respectively, compared with 12.6 (9.1–16.2) and 12.1 (8.7–15.6) for those with GTV 50–100 ml and 8.6 (6.3–10.9) and 8.6 (6.3–10.9) for those with GTV >100 ml. OS and PFS were independent of age, gender, smoking and betel nut chewing history, p-16 status, initial cancer sites, original AJCC stage, recurrent AJCC stage, sites of SBRT, dose of SBRT, or grading of acne formation.

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazards model to predict variables associated with overall survival and progression free survival.

| Overall survival |

Progression free survival |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Variables | ||||

| Age: >58 years (Ref: ≦58 years) | 1.4 (0.8–2.6) | 0.28 | 1.2 (0.6–2.0) | 0.61 |

| Gender: female (Ref: male) | 0.8 (0.3–2.7) | 0.68 | 0.7 (0.2–2.4) | 0.59 |

| Smoking: yes (Ref: no) | 0.9 (0.4–2.8) | 0.97 | 1.2 (0.5–3.2) | 0.68 |

| Betel nut: yes (Ref: no) | 1.1 (0.4–2.6) | 0.95 | 0.7 (0.3–1.6) | 0.38 |

| P-16: positive (Ref: negative or unknown) | 0.9 (0.4–1.9) | 0.61 | 0.8 (0.4–1.9) | 0.65 |

| Primary cancer sites: others (Ref: oral cavity) | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) | 0.52 | 1.1 (0.6–2.1) | 0.74 |

| Original AJCC stage: IV (Ref: I-III) | 1.0 (0.4–2.1) | 0.93 | 1.2 (0.5–2.5) | 0.70 |

| Recurrent AJCC stage: rcIVb (Ref: rcIVa) | 2.5 (0.7–9.7) | 0.17 | 2.3 (0.6–8.7) | 0.20 |

| Re-irradiation interval: ≦12 months (Ref: >12 months) | 3.3 (1.7–6.5) | <0.001 | 3.1 (1.6–5.9) | <0.001 |

| SBRT sites: N or T + N (Ref: T) | 0.8 (0.4–1.5) | 0.45 | 0.9 (0.5–1.9) | 0.92 |

| SBRT dose: >40 Gy (Ref: 40 Gy) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.12 | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.16 |

| Gross tumor volume: >50 ml (Ref:≦50 ml) | 4.6 (2.1–9.9) | <0.001 | 3.5 (1.7–7.1) | 0.001 |

| Acne formation:≧grade 2 (Ref: grade 0–1) | 0.6 (0.2–1.4) | 0.22 | 0.6 (0.2–1.3) | 0.16 |

Abbreviations: HR: Hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; Ref: reference; SBRT: stereotactic body radiotherapy; T: gross tumor area; N: gross nodal area; AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging System, 8th edition.

Treatment-related toxicities

Acute grade 3 toxicity related to SBRT was observed in 13 (17.6%) patients (eight grade 3 mucositis and five grade 3 radiation dermatitis). Severe late toxicity (≥grade 3) was observed in 15 (20.3%) patients, including grade 3 dysphagia and/or laryngeal edema in nine patients, osteonecrosis or soft tissue necrosis in five patients, and carotid artery blowout in one patient. Acne formation related to cetuximab was observed in 37 (50.0%) patients, with grade 1 in 17 (23.0%) patients and grade 2 or more in 20 (27.0%) patients.

Discussion

In the literature review, Heron et al. [9] published the first report of concurrent use of SBRT with cetuximab compared with SBRT alone in a matched control study. They observed that the use of concurrent cetuximab conferred an improvement in local control duration (median 23.8 months vs. 13.2 months) and OS (median 24.5 months vs. 14.8 months) compared with SBRT alone. Then, two prospective phase II clinical trials were conducted. A study performed in Pittsburgh treated 48 patients with 40 or 44 Gy in five fractions plus concurrent weekly cetuximab in three injections [11]. The median GTV was 36.5 ml (range 3.6–209.2 ml) in the series. They reported a median OS of 10 months and 1-year OS in 40%, with only 6% grade 3 or more acute or late toxicity; GTV <25 ml was observed to be significantly associated with improved locoregional PFS and OS. In France, another study by Lartigau et al. was a multi-institutional trial that reported on 56 patients treated with 36 Gy in six fractions plus concurrent weekly cetuximab in five injections [10]. They reported a median OS of 11.8 months and 1-year OS in 48%. Of 49 evaluable cases, 49% of cases had a complete response and 20% of cases had a partial response; 32% of patients developed toxicities of grade 3 or higher. Our study basically followed the treatment protocol of the Pittsburgh study. Although the median GTV (64.5 ml) was much larger in our study cohort, we observed that the treatment response and survival was compatible with the published series.

GTV was observed to be a significant survival predictor in this study and in the other series [11,12,14,15]. GTV is linearly correlated with tumor burden and could be the most direct indicator of tumor burden. Diseases with a larger tumor burden usually afford a favorable environment for the proliferation of hypoxic cells and G0 cells and thus result in lower radiosensitivity and an inferior tumor control rate [16]. Accurate measurement of tumor volume is difficult using the conventional two-dimensional RT technique but has become readily available with the advent of conformal techniques (e.g., SBRT or IMRT). A number of studies have confirmed the influence of GTV on locoregional control and/or survival for patients with rHNSCC treated with SBRT. The cut-off value of GTV varies among different study cohorts; it was 50 ml in our series, 25 ml in studies by Vargo et al. [11,12] and Rwigema et al. [14], and 15 ml in a study by Kodani et al. [15].

A re-irradiation interval >12 months was observed to be the other significant favorable survival predictor and an indicator of treatment response in this study. The prognostic significance of the re-irradiation interval for rHNSCC remains controversial. Spencer et al. [17] reported the outcome of RTOG trial 9610 for rHNSCC treated with re-irradiation and chemotherapy and observed that those who entered the trial at > 1 year out from initial RT had better survival than those who were <1 year out from prior RT. Kress et al. treated 85 patients with rHNSCC by SBRT alone and observed that a re-irradiation interval >2 years was associated with improved OS [18]. In contrast, Vargo et al. observed no significant difference in local control, distant control, and OS according to the re-irradiation interval (continuous data) [11].

Taiwan has one of the highest incidences of HNSCC in the world. The high incidence of HNSCC may be associated with the habits of cigarette smoking and betel quid chewing in the population [19]. However, recent epidemiological reports claim that the rising incidence of HNSCC in Taiwan might also be due to the increasing incidence of human papilloma virus (HPV)-related HNSCC [20]. Positive HPV status has been observed to be a favorable survival predictor for rHNSCC treated by salvage chemo-RT ± cetuximab [21] or SBRT ± cetuximab [22]. However, in our cohort, we failed to observe a difference in treatment response or survival regarding the history of smoking or betel nut consumption and the p-16 status, a surrogate of HPV infection.

Acne formation is one of the most common toxicities related to cetuximab and has been observed to be a survival predictor for patients with locally advanced HNSCC treated with RT plus cetuximab. Bonner et al. reported that OS was significantly improved in those who experienced an acneiform rash of at least grade 2 severity compared with patients with no rash or grade 1 rash [23]. In the current study, 50% of cases presented with acne formation related to cetuximab, and most were grade 1. However, we failed to observe significant differences in the treatment response or survival in those with or without obvious acne formation.

In our patients, 20.3% experienced grade 3 or more late toxicities, including dysphagia, laryngeal edema, osteonecrosis, soft tissue necrosis, and carotid artery blowout. The incidence rate was compatible with the series reported by Ling et al. [24]. In this study, carotid artery blowout caused by the treatment was observed in one patient. In the Pittsburgh study, Gebhardt et al. [25] observed an incidence of carotid blowout of 2.7% for the 186 patients with rHNSCC treated with SBRT ± cetuximab, but no significant association could be found between dose–volume parameters and the risk of carotid blowout.

All of our patients received a PET-CT scan for tumor staging and target delineation of SBRT. Compared with conventional CT scan, PET-CT has been shown to be potentially more sensitive and accurate in target delineation of RT planning and response assessment after treatment in patients with head and neck cancer [26,27]. Metabolic response might precede the anatomic response seen on the CT scan, and a recurrent tumor might be multicentric, containing numerous foci that are easily confused with scar tissue in patients with previously irradiated HNSCC. Heron et al. showed good agreement between PET and CT scans, but only for the assessment of CR and PD [9]. In contrast, our data revealed significant good agreement (kappa value 0.61) between the measures of the RECIST and PET-CT for the 60 evaluable patients.

Due to its retrospective nature, this study has several potential limitations or sources of bias. With short-term survival and follow-up, patients could have had toxicities that were not presented, and the long-term toxicities could be underestimated. Additional management (e.g., chemotherapy, biochemotherapy or immunotherapy) for those with treatment failure after SBRT + cetuximab was not included in the analysis of the current study. However, as a result, this study serves to support the clinical evidence that SBRT plus cetuximab provides a promising salvage strategy for those patients with previously irradiated but unresectable rHNSCC, especially those with a re-irradiation interval >12 months or GTV ≦ 50 ml.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The study was partly supported by the manpower from grant “CMRPG8K1061-2” and “CMRPG8J1031-3” of the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Parsons J.T., Mendenhall W.M., Stringer S.P., Cassisi N.J., Million R.R. Salvage surgery following radiation failure in squamous cell carcinoma of the supraglottic larynx. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;32:605–609. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00527-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jayaram S.C., Muzaffar S.J., Ahmed I., Dhanda J., Paleri V., Mehanna H. Efficacy, outcomes, and complication rates of different surgical and nonsurgical treatment modalities for recurrent/residual oropharyngeal carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2016;38:1855–1861. doi: 10.1002/hed.24531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sacco A.G., Cohen E.E. Current treatment options for recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3305–3313. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim C.M., Clump D.A., Heron D.E., Ferris R.L. Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT) for primary and recurrent head and neck tumors. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teckie S., Lok B.H., Rao S., Gutiontov S.I., Yamada Y., Berry S.L., et al. High-dose hypofractionated radiotherapy is effective and safe for tumors in the head-and-neck. Oral Oncol. 2016;60:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quan K., Xu K.M., Zhang Y., Clump D.A., Flickinger J.C., Lalonde R., et al. Toxicities following stereotactic ablative radiotherapy treatment of locally-recurrent and previously irradiated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2016;26:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonner J.A., Harari P.M., Giralt J., Azarnia N., Shin D.M., Cohen R.B., et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:567–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vermorken J.B., Mesia R., Rivera F., Remenar E., Kawecki A., Rottey S., et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1116–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heron D.E., Rwigema J.C., Gibson M.K., Burton S.A., Quinn A.E., Ferris R.L. Concurrent cetuximab with stereotactic body radiotherapy for recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a single institution matched case-control study. Am J Clin Oncol. 2011;34:165–172. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181dbb73e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lartigau E.F., Tresch E., Thariat J., Graff P., Coche-Dequeant B., Benezery K., et al. Multi institutional phase II study of concomitant stereotactic reirradiation and cetuximab for recurrent head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2013;109:281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vargo J.A., Ferris R.L., Ohr J., Clump D.A., Davis K.S., Duvvuri U., et al. A prospective phase 2 trial of reirradiation with stereotactic body radiation therapy plus cetuximab in patients with previously irradiated recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int I Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91:480–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vargo J.A., Heron D.E., Ferris R.L., Rwigema J.C., Kalash R., Wegner R.E., et al. Examining tumor control and toxicity after stereotactic body radiotherapy in locally recurrent previously irradiated head and neck cancers: implications of treatment duration and tumor volume. Head Neck. 2014;36:1349–1355. doi: 10.1002/hed.23462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young H., Baum R., Cremerius U., Herholz K., Hoeskstra O., Lammertsma A.A., et al. Measurement of clinical and subclinical tumour response using [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography: review and 1999 EORTC recommendations. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) PET Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1773–1782. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rwigema J.C., Heron D.E., Ferris R.L., Gibson M., Quinn A., Yang Y., et al. Fractionated sterotactic body radiation therapy in the treatment of previously-irradiated recurrent head and neck carcinoma: updated report of the University of Pittsburgh experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:286–293. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181aacba5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kodani N., Yamazaki H., Tsubokura T., Shiomi H., Kobayashi K., Nishimura T., et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for head and neck tumor: disease control and morbibity outcomes. J Radiat Res. 2011;52:24–31. doi: 10.1269/jrr.10086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Z., Su Y., Zeng R.F., Gu M.F., Huang S.M. Prognostic value of tumor volume for patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with concurrent chemotherapy and intensity-modulated radiotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:69–76. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1542-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spencer S.A., Harris J., Wheeler R.H., Machtay M., Schultz C., Spanos W., et al. Final report of RTOG 9610, a multi-institutional trial of reirradiation and chemotherapy for unresectable recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2008;30:281–288. doi: 10.1002/hed.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kress M.A., Sen N., Unger K.R., Lominska C.E., Deeken J.F., Davidson B.J., et al. Safety and efficacy of hypofractionated stereotactic body reirradiation in head and neck cancer: long-term follow-up of a large series. Head Neck. 2015;37:1403–1409. doi: 10.1002/hed.23763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu W.L., Yu K.J., Chiang C.J., Chen T.C., Wang C.P. Head and neck cancer incidence trends in Taiwan, 1980 ∼ 2014. Int J Head Neck Sci. 2017;1:180–189. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang T.Z., Hsiao J.R., Tsai C.R., Chang J.S. Incidence trends of human papillomavirus-related head and neck cancer in Taiwan, 1995-2009. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:395–408. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fakhry C., Zhang Q., Nguyen-Tan P.F., Rosenthal D., El-Naggar A., Garden A.S., et al. Huaman papilloma virus and overall survival after progression of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3365–3373. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis K.S., Vargo J.A., Ferris R.L., Burton S.A., Ohr J.P., Clump D.A., et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for recurrent oropharyngeal cancer - influence of HPV status and smoking history. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:1104–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonner J.A., Harari P.M., Giralt J., cohen R.B., Jones C.U., Sur R.K., et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer: 5 year survival data from a phase 3 randomised trial, and relation between cetuximab-induced rash and survival. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:21–28. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ling D.C., Vargo J.A., Ferris R.L., Ohr J., Clump D.A., Yau W.W., et al. Risk of severe toxicity according to site of recurrence in patients treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy for recurrent head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;95:973–980. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gebhardt B.J., Vargo J.A., Ling D., Jones B., Mohney M., Clump D.A., et al. Carotid dosimetry and the risk of carotid blowout syndrome after reirradiation with head and neck stereotactic radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;101:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garg M.K., Glanzman J., Kalnicki S. The evolving role of positron emission tomography-computed tomography in organ-preserving treatment of head and neck cancer. Semin Nucl Med. 2012;42:320–327. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Troost E.G., Schinagl D.A., Bussink J., Oyen W.J., Kaanders J.H. Clinical evidence on PET-CT for radiation therapy planning in head and neck tumours. Radiother Oncol. 2010;96:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]