Highlights

-

•

Across Latin America and the Caribbean, policy measures and COVID-19 outcomes have differed.

-

•

Comparatively, Uruguay performed well in the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

•

Most countries reviewed relied on border closures and other restriction of movement.

-

•

Uruguay prioritized economic and social measures to support housing, food and self-isolation.

-

•

Social and economic safety-net measures are essential to support public health interventions.

Keywords: COVID-19; Policy review; Latin America & the Caribbean, pandemic response

Abstract

A range of public health and social measures have been employed in response to the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). Yet, pandemic responses have varied across the region, particularly during the first 6 months of the pandemic, with Uruguay effectively limiting transmission during this crucial phase. This review describes features of pandemic responses which may have contributed to Uruguay’s early success relative to 10 other LAC countries - Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Panama, Paraguay, and Trinidad and Tobago. Uruguay differentiated its early response efforts from reviewed countries by foregoing strict border closures and restrictions on movement, and rapidly implementing a suite of economic and social measures. Our findings describe the importance of supporting adherence to public health interventions by ensuring that effective social and economic safety net measures are in place to permit compliance with public health measures.

1. Introduction

The Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region has been disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic [1]. In the absence of approved treatments, and while waiting for widespread vaccination, countries in the region relied on public health and social measures such as mask wearing, physical distancing, quarantines, and curfews to protect the health and well-being of communities. In many LAC countries, these measures were coupled with strict enforcement to break chains of transmission, raising equity and human rights concerns [2].

Without question, public health measures during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic had social and economic impacts [3]. Across LAC, the economic recession caused by the pandemic increased the unemployment rate by 2.7 percentage points by the end of 2020 [4]. The impacts on income and employment status led 97 million more people to poverty that year [5]. Additionally, 14 million people in the region were at risk of reduced nutrition due to food insecurity [6]. Yet, only 50 % of the region’s population is covered by social protection to alleviate the impact of the pandemic on households [7].

While these figures speak to the impact of COVID-19 on communities in LAC, there was considerable variation in total cases and deaths among countries early in the pandemic. This regional variation emerged against a longstanding regional patchwork of fragmented health systems, vast inequities in housing, income, and healthcare, and in many countries, ongoing political instability, and social unrest [1], [2]. These realities created social conditions ideal for rapid viral spread – poverty, housing overcrowding, and lack of access to care – and presented multiple challenges to mounting and sustaining an effective public health response to an emerging infectious threat. The COVID-19 pandemic has further demonstrated the need to implement combined, multisectoral, swift, and strict measures to overcome public health emergencies [8], [9], [10].

During the first year of the pandemic, Uruguay remained an outlier in the region with far lower morbidity and mortality and earned global praise for an exemplary public health response during the first wave of infections [11], [12]. Six months after the declaration of the pandemic on March 11th, 2020, Uruguay had the lowest number of cases and deaths per million among the eleven countries included in our study. Despite Uruguay’s early success containing the pandemic, the existing literature has not compared the comprehensive set of policy interventions taken in Uruguay with other countries in the region. Some studies have provided high-level overviews of LAC countries’ responses [12], [13], including one study of a selection of LAC countries that did not include Uruguay [14], while others have focussed on social and economic protection measures [15], [16].

Uruguay’s health system and broader economic and social context are important to consider as it may have contributed to early success in the pandemic. For example, public spending on health in Uruguay was among the highest in the region, accounting for 7 % of GDP in 2017 compared to the average of 4 % in the Latin American and Caribbean region [17]. Also, there was relatively low out-of-pocket spending in Uruguay (15 % of current expenditure on health in 2019) compared to the LAC regional average (28 %) [18]. Supply of physicians and ICU beds were also higher in Uruguay (5 physicians per 1,000 population in 2017 and 19.9 ICU beds 100,000 population in 2020) than the OECD (3.5 physicians per 1,000 and 12 ICU beds per 100,000 population) and LAC regional average (2 per 1,000 population and 9.1 ICU beds per 100,000 population) [19], [20]. Importantly, Uruguay is also recognized for its comprehensive social protection systems and the lowest poverty rate of the region, allowing a large proportion of residents to have access to social supports and unemployment insurance (75 % with access to social security in 2018) [21], [22], [23], [24]. Additionally, according to the Gallup World Poll, trust in the government is relatively higher in Uruguay (36 % reported trusting the government in 2018) than the LAC regional average (34 %) which may increase public’s willingness to follow government recommendations [21], [25]. Taken together, this context pre-pandemic is important to consider when interpreting the findings of a review of pandemic responses.

In this paper, we explore the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic and describe features of pandemic responses which may have contributed to Uruguay’s early success in mitigating widespread community transmission relative to 10 other LAC countries; Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Panama, Paraguay, and Trinidad and Tobago. Comparing the pandemic response of an early successful case, Uruguay, can provide insights to other countries in the region into what constitute effective mitigation measures in the early stages of a pandemic.

2. Materials and methods

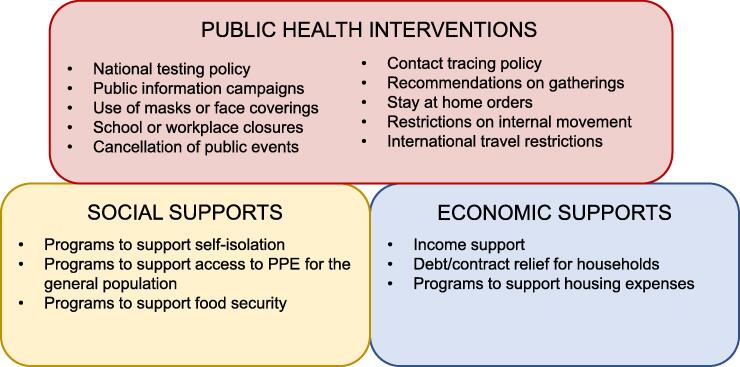

For the purposes of this comparative analysis, we set out three dimensions of early actions taken to prevent and mitigate community circulation of COVID-19: public health interventions, social supports, and economic supports (Fig. 1). The three dimensions include the comprehensive set of policy interventions needed for an effective public health response. This three-dimensional framework is conceptually grounded in the Dahlgren-Whitehead model, which recognizes that health and well-being are products of a range of structural and contextual factors [26]. Thus, this framework illustrates the role of combined and multisectoral public health interventions as crucial to preserving health and well-being during a pandemic.

Fig. 1.

Dimensions of early actions taken to mitigate community circulation of COVID-19.

Public health interventions aim to reduce transmission and are key to mitigating spread of COVID-19 in communities [27]. These measures pose many challenges to effectively implement in ways that support widespread and ongoing adherence, while minimizing social and economic harms to individuals, families, and communities. It is particularly difficult for marginalized populations to abide by some measures without experiencing additional harms [28], [29]. Social supports in the context of COVID-19 assist individuals or families to ensure access to the resources required to comply with public health interventions. Economic supports in the context of COVID-19 prevent or offset catastrophic costs or financial harms experienced by individuals or families due to compliance with public health interventions.

We selected eleven LAC countries who received emergency loans from the World Bank to finance their COVID-19 response, and agreed to participate in cross-country learning, including a World Bank study on which this article is based [30]. These countries represent a breadth of geographical, political, and socioeconomic contexts across the region. Our review focused on the strictest early interventions to reduce community transmission of COVID-19, with Uruguay as an exemplar for early responses. Given that the World Health Organization (WHO) characterized the spread of COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11, 2020, we considered policies and measures introduced during the first six months of the pandemic, from early March 2020 to late August 2020 [31], at a time when evidence about the effectiveness of policy responses was limited yet variation in cases and deaths from the pandemic was large.

We examined 18 government interventions based on indicators and stringency classification proposed by the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker plus five additional relevant interventions (Table 1) [32]. The interventions were coded based on the stringency of the measure, ranging from no measure in place to stringent. We also recorded the date when the strictest intervention for each of the indicators was introduced and a brief description of the policy. All indicators were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet and were chosen based on our study objectives; more information is provided in Supporting information file 1. To collect the data on policy measures, we conducted a review of academic and grey literature including the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker database, media sources, and websites or reports of key governmental and regional organizations. World Bank staff in each country identified additional data sources. Our findings were collated into standardized spreadsheets validated by the World Bank lead health expert in each country together with representatives from ministries of health over several iterative stages between November 9–18, 2020. We then conducted a narrative synthesis of the data by investigating the similarities and differences in the timing, stringency, and types of policy interventions across the countries.

Table 1.

Description of the strictest government interventions to COVID-19 considered in the review.

| Intervention | Description of most stringent measures |

|---|---|

| Public Health Interventions* | |

| National testing policy | Open public testing |

| Contact tracing policy | All COVID-19 cases undergo contact tracing |

| School closing | Mandatory closing |

| Workplace closing | Mandatory closing all-but-essential |

| Cancellation of public events | Required cancelling |

| Recommendations on gatherings | Restrictions on gatherings of 10 people or less |

| Close public transport | Mandatory closing or prohibit most citizen to use it |

| Stay at home | Mandatory with minimal exceptions |

| Restrictions on internal movement | Internal/local movement with restrictions in place |

| International travel restrictions | Ban on international entry from all regions or total border closure |

| Public info campaigns | Coordinated public information campaign |

| Economics Support Interventions * | |

| Income support | Replacement of 50 % or more of lost salary |

| Debt/contract relief for households | Broad debt/contract relief |

| Social support interventions | |

| Use of masks or face coverings**+ | Face mask or coverings are mandatory in all indoor public spaces |

| Programs to support food security + | Programs in place to support food security |

| Programs to support housing expenses+ | Programs in place to support housing expenses |

| Programs to support self-isolation+ | Programs in place to support self-isolation |

| Programs to support citizens’ access to personal protection equipment (PPE) + | Programs in place to support citizens’ access to personal protection equipment (PPE) |

* Measures and stringency classification proposed by the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker; ** Measure added to Oxford tracker in fall 2020; + Measures and stringency classification proposed by our research team.

3. Results

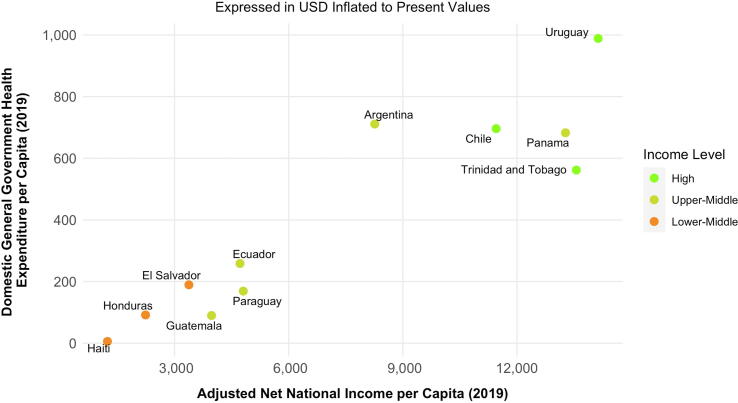

To provide the socioeconomic and political context for these findings, we have presented comparative measures for each of these 11 countries. These countries range from lower-middle income to high income, and there is a variation in the domestic general government health expenditure per capita (Fig. 2). The range of policy tools available to each of these countries varies due to the unique constraints and challenges of each country. More information is provided in Supporting information files 2 and 3. Uruguay is among the most socio-economically advanced LAC countries as measured by income, health, and education in the World Bank Human Capital Index [17]. However, this factor alone does not explain the successful pandemic response early in the pandemic since other countries in the study are comparable on these measures.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of economic indicators of selected LAC countries and Uruguay.

3.1. Public health interventions

Despite the WHO declaring COVID-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on 30 January 2020, the eleven countries in our study largely implemented public health interventions to prevent or limit chains of transmission in March [33]. These included public information campaigns, policies on the use of masks, policies to support physical distancing, and restrictions on movement or travel. Table 2 offers an overview of overall public health policies, specific measures, when they were announced in each comparator country.

Table 2.

Public health measures during the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic in 11 LAC countries.

| Uruguay | Argentina | Chile | Ecuador | El Salvador | Guatemala | Haiti | Honduras | Panama | Paraguay | Trinidad and Tobago | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National testing policy | Open public testing | Y (June) | N | N | Y (March) | N | Y (May) | N | N | N | N | N |

| Contact tracing policy | Allcases undergo contact tracing | Y (May) | Y (May) | Y (July) | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y (May) | Y (April) |

| Public information campaigns | Government website or campaign | Y (March | Y (January) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (January) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) |

| Use of Masks or Face Coverings | Mandatory masks only on public transport or public roads | N | Y (April) | N | N | N | N | Y (May) | N | N | N | N |

| Mandatory masks in public or private where people gather | Y (April) | N | N | Y (April) | Y (April) | Y (April) | N | Y (March) | Y (June) | Y (May) | Y (August) | |

| Restrictions on Movement or Travel | Stay at Home Orders | N | Y (March) | Y (May) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (April) | Y (March) |

| Public Transport Restrictions | N | Y (March) | Y (April) | Y (March) | Y (May) | Y (March) | Y (April) | Y (March) | Y (April) | Y (March) | Y (March) | |

| Restrictions on Internal Movement | Y (April) |

Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | |

| International Travel Restrictions | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | |

| Policies on Physical Distancing | Workplace Closures | N | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | N | Y (March) |

| School Closures | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | |

| Recommendations on Gatherings | N | Y (March) | Y (May) | N | Y (March) | N | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | |

| Cancellation of Public Events | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (March) |

N = No measure implemented; Y = Yes, a measure was implemented.

Central to outbreak response and management is the ability to rapidly test, trace, and isolate suspected cases and their contents. This must be supported by integrated laboratory and surveillance networks for reporting and coordination. Early in the pandemic, Uruguay became a regional leader in testing and contact tracing. This was facilitated by the development of domestic COVID-19 test kits and rapid creation of a decentralized network of laboratories to process tests. Most of the countries reviewed scaled up similar public health functions in response to rising case numbers after widespread community transmission. For example, in Argentina the Detectar program, which offered testing in communities, was not launched until May, after community transmission was widespread [34]. Similarly, in Ecuador, robust community centered testing efforts were coordinated in response to community transmission. Additionally, few countries reported contact tracing efforts early in the pandemic, for instance Chile introduced a strategy to test, trace, and isolate, monitoring its success through indicators; although, this program was adopted in July [35]. An exception to this was Uruguay, which purposively scaled up contact tracing with the purpose of identifying and breaking up the initial clusters resulting from a wedding attended by the country’s index case.

Countries in LAC also introduced comprehensive public health measures to contain viral transmission in the early phase of the pandemic. In advance of the PHEIC declaration, both Argentina and El Salvador implemented coordinated public information campaigns about the emerging COVID-19 threat. Compared to other countries, Uruguay, as well as Ecuador, El Salvador, and Guatemala, introduced policies on mask wearing in all public places relatively early. In Ecuador, on 6 April 2020, face masks were mandatory in all public spaces for people leaving their homes. On 13 April, in both El Salvador and Guatemala, face masks were mandatory in public spaces. By 21 April 2020, Uruguay required face masks to be worn in spaces where people gather, starting in supermarkets. Also, face masks were distributed to anyone on the street without a mask. Uruguay did not place legal restrictions on gatherings but did close schools, suspend public events, and encouraged workplace closures [36]. This contrasts with most other countries, which placed limitations on gathering early in the pandemic. Some had broad policies, for example, on 11 March 2020 (the same day the PHEIC was declared), Paraguay suspended large events such as concerts, religious meetings and activities in indoor places [37]. Other policies were more targeted and included attendance caps. For example, in Trinidad and Tobago, gatherings were limited to five or less people as of 31 March 2021 [38]. Others were more sweeping, for example Honduras banned all gatherings regardless of attendance for seven days beginning on 16 March 2020 [39].

Additionally, whereas Uruguay avoided lockdowns early in the pandemic, most other countries swiftly enacted strict stay at home orders and enforced curfews. For example, on 19 March 2020 in Haiti, the government declared a curfew throughout the national territory between 8:00 pm and 5:00 am for one month [40]. Exemptions to the curfew include health staff, individuals looking for health care, mass media workers, and other essential workers. This contrasts with Uruguay where no such restrictions were declared, and the public were urged through a public information campaign to stay home during tourism week in early April. Reviewed countries including Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Trinidad and Tobago restricted internal movement across regional borders; in some regions, such as Honduras, movement between specific cities was prohibited. However, Uruguay did not take similar action early in the pandemic beyond urging residents to stay home. Compared to other reviewed countries, Uruguay was also slow to fully close international borders, only doing so on 24 March 2020. Other countries had enacted strict border controls early in March. For example, El Salvador prohibited foreigners to enter the country as early as 12 March 2020, the day after the COVID-19 was characterized as a pandemic by the WHO [31].

3.2. Economic & social supports

Public health measures are not without economic consequences and the selected LAC countries have suffered significant economic contractions during the pandemic. These economic losses have emerged against a backdrop of long-standing economic instability, ongoing debt, a largely informal or underemployed workforce, and deepening inequality both within and across the region [2], [41], [42]. To support populations in adhering to restrictive public health measures requires additional measures to supplement income loss, relieve personal and household debt, and ensure that housing expenses are met. Table 3 illustrates social and economic supports and when they were enacted in comparator countries in contrast to those enacted in Uruguay.

Table 3.

Social and economic supports during the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic in LAC.

| Uruguay | Argentina | Chile | Ecuador | El Salvador | Guatemala | Haiti | Honduras | Panama | Paraguay | Trinidad and Tobago | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing Supports | Moratorium on Evictions | N | Y (March) | N | Y (March) | N | N | N | N | Y (May) | Y (April) | N |

| Offered Mortgage Supports | Y (March) | Y (March) | N | Y (March) | Y (March) | N | N | N | Y (May) | N | Y (March) | |

| Rental Pricing Supports (Freezing Prices, Subsidies) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (July) | N | N | N | N | N | Y (May) | N | Y (March) | |

| Income Supports | Cash Transfers for Low-Income Families | N | Y (March) | Y (June) | Y (April) | N | Y (April) | Y (June) | N | Y (April) | Y (March) | Y |

| Cash Transfers for Some Sectors (e.g., Frontline Workers, Textile Workers, Entrepreneurs) | Y (March) | N | N | N | Y (April) | N | Y (June) | Y (April) | N | Y (March) | N | |

| Increased Access to Benefits of Unemployment Insurance | Y (March) | N | Y (June) | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | |

| Self-isolation supports | Isolation Centres for Confirmed or Potential Cases of COVID-19 | N | Y (March) | Y (March) | N | Y (March) | N | N | N | Y (March) | N | N |

| Quarantine Centres for People Entering the Country (Citizens, Residents, Deported, Travelers) | N | N | N | Y (May) | Y (March) | Y (March) | N | N | N | Y (March) | Y (March) | |

| Shelter For People in Need of a Place to Isolate (e.g., Health Workers, People Experiencing Homelessness, Victims of Domestic Abuse) | Y (March) | N | N | Y (May) | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y (March) | |

| Citizen's access to PPE | Price Monitoring and/or Freezing | Y (April) | Y (March) | Y (April) | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Delivery of Sanitary Baskets (Included Items Such as Masks, Sanitizer Gel, Soap, Gloves) | N | N | Y (April) | N | Y (April) | N | N | Y (March) | N | N | N | |

| Delivery of Face Masks | N | N | N | N | N | Y (April) | Y (March) | N | Y (April) | N | Y (April) | |

| Hoarding Monitoring | N | N | N | N | N | Y (April) | N | Y (March) | N | N | N | |

| Debt relief | Postponement of Income Tax Payments | N | N | N | Y (March) | Y (May) | N | Y (May) | Y (April) | N | N | N |

| Suspension of Fines or Other Sanctions due to the Rejection of Cheques | N | Y (March) | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y (April) | N | |

| Increased Accessibility for Loans and Flexibilities on Their Payments | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (February) | Y (March) | Y (May) | Y(April) | Y (May) | Y (April) | Y (April) | N | Y (March) | |

| Subsidy and/or Suspension of Cancelation of Utilities | N | Y (March) | Y (February) | N | Y (May) | Y (April) | N | Y (April) | Y (April) | Y (April) | Y (March) | |

| Suspension of Fees or Commissions for Bank Operations | N | Y (March) | N | N | N | N | Y (May) | N | N | N | N | |

| Food security supports | Cash Transfers, Electronic Vouchers | Y (March) | Y (March) | N | N | Y (March) | N | N | N | Y (May) | Y (March) | Y (March) |

| Delivery of Food Baskets | Y (March) | N | Y (April) | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y(April) | N | Y (March) | Y (May) | Y (March) | N | |

| Price Monitoring and/or Freezing | Y (March) | Y (March) | Y (April) | N | Y (March) | Y (April) | N | Y (March) | N | N | N | |

| Increased Budget for Food Assistance Programs (Soup Kitchens, School Feeding Programs) | Y (March) | Y (March) | N | N | N | Y (April) | Y (March) | N | N | N | N | |

| Loans/Agreements with Food Producers | Y (March) | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y (March) | N | N | N |

N = No measure implemented; Y = Yes, a measure was implemented.

Economic supports in Uruguay implemented in the first six months of the pandemic broadly included housing supports, household debt relief, and income supports. By March 2020, Uruguay had offered a subsidy of up to 50 % of rent for those enrolled in unemployment insurance and flexible agreements on mortgage payments. Several other studies also implemented comprehensive housing supports early in the pandemic. Trinidad and Tobago took similar actions to Uruguay in March, and Ecuador additionally offered a moratorium on evictions in March, but Argentina offered the most comprehensive suite of housing supports with a moratorium on evictions, mortgage supports, and rental supports. Other reviewed countries offered housing supports later in the pandemic. Panama, for example, offered a moratorium on evictions, as well as rental pricing and mortgage supports in May 2020, while rental pricing supports were introduced in Chile in July 2020. Some countries did not offer extensive housing supports, however, such as Haiti, Guatemala, and Honduras.

Options to provide debt relief included postponement of income tax payments, suspensions of fines or other sanctions due to rejection of cheques, increased accessibility of loans and flexibilities on their payments, subsidy, or suspension of cancelation of utilities and suspension of fees or commissions for bank operations. In March 2020, Uruguay offered deferral of loans for retirees, new lines of credit with flexible conditions, offered loans for small and medium-sized businesses, and extended maturity terms of credits granted to the non-financial sector. In February, before the declaration of the pandemic, Chile introduced measures for both loan flexibility and to prevent cancelation of utilities. Other countries reviewed were slower to introduce debt relief measures – Haiti and El Salvador, for example - and most introduced measures to increase loan accessibility, followed by subsidies for, or suspension of cancellation of, utilities.

Income supports included cash transfers, either based on income or sector (e.g., frontline workers) and increased access to unemployment insurance benefits. In March 2020, Uruguay introduced measures that increased flexibility to use unemployment insurance and subsidies for three months employment by paying companies a third of the current minimum wage. Most countries took the cash transfer approach to provide income subsidies. Some countries provided income supports to low-income families, others provided supports to specific sectors, while Haiti and Paraguay provided both to both sector and income-eligible individuals. However, several months later, in June 2020, Chile introduced both cash transfers and increased access to unemployment insurance – the only country to do so.

To ensure compliance with public health measures, supports can be provided to help populations meet their basic subsistence needs. This is particularly important given the pre-existing and pervasive inequities in the region. Public health measures may have disproportionate impacts on people living in poverty, who are in precarious or informal employment, or are otherwise marginalized [43]. For many, pre-existing risks for, or realized, food insecurity may be worsened, self-isolation may be impossible in crowded living situations, and personal protective equipment (PPE) may be inaccessible or inadequate to ensure compliance with public health measures.

Social supports implemented in the first six months of the pandemic included measures to support food security, self-isolation, and citizens’ access to PPE. Food security supports included cash transfers or vouchers, food basket delivery, price monitoring or freezing, increased budgets for food assistance programs, and loans or agreements with food producers. In March 2020, Uruguay introduced a suite of measures for food security. This included distributing food cards and food baskets, increasing the budget for municipal dining rooms and food baskets, increasing access to family allowances, and establishing telephone lines to request food aid. Additionally, Uruguay monitored food prices and made agreements with producers, merchants, and intermediaries to ensure affordability. Most other countries introduced a similar combination of measures between March and May of 2020. For instance, in March 2020, Paraguay introduced a cash transfer program as a food aid, Haiti increased the food rations for children in school feeding programs, and Argentina and Honduras fixed food prices.

Self-isolation supports to mitigate household transmission included isolation centres for people confirmed or symptomatic of COVID-19, quarantine centres for people entering the country, and shelter for people in need of a safe place to self-isolate including health workers, people experiencing homelessness, and victims of domestic abuse. In March 2020, Uruguay took action to transfer some elderly people experiencing homelessness into permanent shelters, increased the budget to create new shelters for people experiencing homelessness, and extended the stay hours in the existing shelters. There was less evidence of national policies to address shelter for at-risk communities, with only Trinidad and Tobago and Ecuador implementing measures to ensure shelter. Most countries focused self-isolation supports on quarantine facilities for returning travelers, such as Paraguay and Guatemala, and isolation centres for people diagnosed or suspected to have been infected with COVID-19, such as Panama. Conversely, early in the pandemic.

Supports to ensure citizens had access to adequate PPE including price monitoring or price freezes, delivery of ‘sanitary baskets’ (which included items such as masks, sanitizer gel, soap, etc.), delivery of face masks, and mechanisms to monitor hoarding. Honduras implemented price monitoring and face mask delivery in March 2020, and Haiti delivered free masks at clinics and public settings. Uruguay introduced similar measures in April 2020. This included a weekly price list publication of basic health products. To ensure access to PPE for citizens, some countries provided free face masks, often through non-governmental organization (NGO) partnerships, such as Trinidad and Tobago.

4. Discussion

In characterizing early responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in LAC countries as compared to the early achievements of Uruguay, we offer insights into the measures and policies attempting to mitigate community transmission and preserve health and well-being early in the pandemic. While all countries in our study introduced a comprehensive set of public health interventions in March 2020, Uruguay implemented a timely suite of social and economic supports, combined with more widespread community testing and contact tracing than the other countries. By exploring these measures against an early success story, Uruguay, our findings lend support to the importance of supporting adherence to public health interventions by ensuring that effective social and economic safety net measures are in place to permit compliance with public health measures [44], [8], [9], [10]. However, globally, these social and economic measures have faced implementation challenges ranging from government fiscal restraints, differing priorities between donors and governments, as well as challenges in scaling what some consider ‘shock responsive’ measures (and what others consider to be mostly ‘stop gap’ measures), such as cash grants and food transfers, within a short time frame [45], [46]. Similarly, our findings underscore the challenges in mounting and sustaining pandemic responses over time.

When reviewing the timing of measures, our findings affirm recent global findings that February was a ‘lost month’ between the declaration of the PHEIC and the pandemic [47], [48]. This crucial time necessitated aggressive action to prevent local outbreaks from spreading [48]. However, most countries in our review either took no or piecemeal action in February, instead adopting a ‘wait and see approach,’ followed by ever increasing public health and social measures to curb infections. These social and economic measures in response to the unfolding COVID-19 crisis took an emergency approach, with countries taking what has been called an ‘emergency Keynesianism’ approach spending vast amounts on social and economic protections regardless of pre-crisis debt and fiscal concerns [49], [50], [51]. Others have highlighted how these novel programs to provide relief during the pandemic, although rapidly mounted through many channels, were often in part based on existing policies, programs, and avenues of government support [51] and shaped by state factors including formal political institutions and state capacity [52]. Indeed, Uruguay’s robust social support system before and during the early months of the pandemic helped maintain adherence to public health interventions, particularly among the population working in the formal sector. However, as seen in other countries in the region, Uruguay could not sustain these strong economic supports. Unsustainability and inequities in the distribution of the social supports contributed to a weaker adherence to the mobility restrictions later in the pandemic, leading to an increase of cases among the most vulnerable population [24].

Additionally, unlike what was seen in Uruguay for the most part, countries were selective in which guidance they followed or which ‘rules’ they abided by. Partially this was attributable to the models they used, based variously on past epidemics or outbreaks be it Ebola, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), or influenza containment. However, this dynamic situation was also reflective of the evolving evidence and policy playbook that determined national containment strategies. For example, one of the earliest actions taken by most reviewed countries was to close borders, either selectively or in entirety. Yet, this contravened the International Health Regulations (IHR) 2005 guidance at the time and disproportionately impacted vulnerable groups including cross-border workers, as well as refugees and asylum seekers who may be forced to take irregular channels putting them at risk of human trafficking [53], [54], [55] Similarly, despite calls for guidance, the WHO only offered recommendations on mask wearing in June 2020 [56], [57]. Most countries reviewed implemented masking measures in public with supportive measures for citizens to access PPE before this recommendation was made. As our findings highlight, the pandemic has suggested the lack of consistency between global recommendations and national actions taken, particularly against the backdrop of uncertainty, emerging evidence, and increasing case numbers characteristic of the pandemic [48]. In these ways COVID-19 has challenged and called into question the current model of global governance of pandemic response and preparedness [58].

Finally, while our review explores the first six months of the pandemic, we acknowledge the challenges faced by nations in sustaining COVID-19 responses in the face of second and third waves involving new variants. With time, inequities in vaccine access between poor and rich nations has grown, challenging the ability of some countries to maintain an effective pandemic response [59], [60]. In addition, policy approaches that worked in the first wave could be found wanting in subsequent waves or fiscally untenable for governments to renew [61]. Uruguay was seen as an early success story, in part due to rapidly scaled testing and contact tracing to identify and isolate or quarantine clusters of cases and their contacts, as well as public policies to prevent onward transmission in communities [12]. However, by May 2021 the country registered the most daily cases per capita globally, perhaps as a result of its robust testing and reporting infrastructure, but also in part due to the challenges they faced in sustaining economic and social supports, as noted above [62]. In press the deputy secretary of the Health Ministry commented “In Uruguay, it’s as if we had two pandemics, one until November 2020, when things were largely under control, and the other starting in November, with the arrival of the first wave to the country” [62].

4.1. Strengths and limitations

A strength of our study is the use of standardized indicators to compare across countries. Further, our collaboration with local experts to verify information further strengthens our descriptions of the policy landscape early in the pandemic. However, our study is not without limitations, for example in this work we describe policy actions taken and do not aim to offer evidence of the effectiveness of their implementation, combination, and impact. Future research should seek to isolate the causal effects of implementing these interventions on outcomes. Indeed, there has been growing evidence of gaps in implementation, and the ongoing high burden of COVID-19 in LAC countries points to the limitations or inequitable application of these measures in practice [63], [64], [65]. Moreover, while our findings explore the importance of early public health, social and economic interventions, the long-term outcome of pandemic responses raises important questions for future research to identify the most effective and equitable reopening measures and long-term pandemic containment strategies [8], [66]. Additionally, while our review describes policies enacted in the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic, we acknowledge that we are unable to fully explore the depth of contextual factors that underpin these responses in each country, particularly the robust pre-existing social policies, as well as lower income inequality, in Uruguay relative to other LAC [67], [68], [69], [70].

5. Conclusion

Our findings lend support to the growing evidence that pandemic responses require a multifaceted approach to mitigate community transmission at the outset of domestic outbreaks. Reviewed countries including Uruguay largely took comprehensive action only after the declaration of the pandemic, not in response to early warnings of an emerging infectious threat. Nevertheless, our findings describe how Uruguay took more rapid action and implemented a comprehensive suite of complementary public health, social, and economic measures. Our study reports on the promise of such an approach that considers social determinants of health and existing social vulnerabilities when implemented in tandem with robust testing and contact tracing efforts. However, our findings raise questions as to how best to scale and maintain pandemic response efforts considering sustained transmission, variants of concern, and with inequitable access to vaccines that characterize COVID-19 in 2021 and beyond.

Author contributions: SA supervised the study. SA, GPM, and JV conceptualized the study. VH, MM-V, and MJ curated the data and conducted formal analysis. VH, MM-V, and MJ wrote the original draft, all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grant funding from the World Bank.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Sara Allin received funding from the World Bank for research assistance support, and Jeremy Veillard is employed by the World Bank, and contributed to study design and write-up.

Footnotes

Supporting information files: Supporting information file 1. Stringency of COVID-19 Measures – Methods. Supporting information file 2. Socioeconomic indicators for the selected LAC countries. Supporting information file 3. Human Capital Index for Selected LAC Countries and Comparator. Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpopen.2022.100081.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Reuters. COVID-19 deaths in Latin America surpass 1 mln as outbreak worsens. Reuters [Internet]. 2021 May 21 [cited 2022 Feb 17]; Available from: https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/covid-19-deaths-latin-america-set-surpass-1-mln-outbreak-worsens-2021-05-21/.

- 2.The Lancet. COVID-19 in Latin America: a humanitarian crisis. The Lancet [Internet]. 2020 Nov 7 [cited 2022 Feb 17];396(10261):1463. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)32328-X/fulltext. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. COVID-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean: An overview of government responses to the crisis [Internet]. OECD. 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 6]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-an-overview-of-government-responses-to-the-crisis-0a2dee41/#component-d1e2952.

- 4.Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, International Labour Organization (OIT), Labour Organization (OIT). Coyuntura Laboral en América Latina y el Caribe: trabajo decente para los trabajadores de plataformas en América Latina [Internet]. CEPAL; 2021 Jun [cited 2022 Mar 4]. Report No.: No. 24 (LC/TS.2021/71). Available from: https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/46955-coyuntura-laboral-america-latina-caribe-trabajo-decente-trabajadores-plataformas.

- 5.World Bank. Updated estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on global poverty: Turning the corner on the pandemic in 2021? [Internet]. World Bank Blogs. 2021 [cited 2022 Mar 4]. Available from: https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/updated-estimates-impact-covid-19-global-poverty-turning-corner-pandemic-2021.

- 6.World Food Programme. Coronavirus puts 14 million people at risk of missing meals in Latin America and the Caribbean [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 17]. Available from: https://www.wfp.org/stories/coronavirus-puts-14-million-people-risk-missing-meals-latin-america-and-caribbean.

- 7.Williams A. Improving shock response in Latin America through adaptive social protection systems [Internet]. World Bank Blogs. 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 17]. Available from: https://blogs.worldbank.org/latinamerica/improving-shock-response-latin-america-through-adaptive-social-protection-systems.

- 8.Oliu-Barton M, Pradelski BSR, Aghion P, Artus P, Kickbusch I, Lazarus JV, et al. SARS-CoV-2 elimination, not mitigation, creates best outcomes for health, the economy, and civil liberties. The Lancet [Internet]. 2021 Jun 12 [cited 2022 Feb 17];397(10291):2234–6. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)00978-8/fulltext. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Carr D. Reducing the risk of pandemic disease threats through multisectoral action [Internet] ReliefWeb. 2020 https://reliefweb.int/report/world/reducing-risk-pandemic-disease-threats-through-multisectoral-action [cited 2022 Feb 17]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferguson NM, Laydon D, Nedjati-Gilani G, Imai N, Ainslie K, Baguelin M, et al. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand [Internet]. Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team; 2020. Report No.: Report 9. Available from: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/ide/gida-fellowships/Imperial-College-COVID19-NPI-modelling-16-03-2020.pdf.

- 11.Taylor L. Covid-19: Why Peru suffers from one of the highest excess death rates in the world. BMJ [Internet] 2021 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n611. https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n611 Mar 9 [cited 2022 Feb 17];372: n611 . Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor L. Uruguay is winning against covid-19. This is how [Internet] The BMJ. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3575. https://www.bmj.com/content/370/bmj.m3575.full.print [cited 2020 Nov 8]. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrus JK, Evans-Gilbert T, Santos JI, Guzman MG, Rosenthal PJ, Toscano C, et al. Perspectives on battling COVID-19 in countries of Latin America and the Caribbean. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2020 Aug [cited 2022 Feb 9];103(2):593–6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7410452/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Garcia PJ, Alarcón A, Bayer A, Buss P, Guerra G, Ribeiro H, et al. COVID-19 Response in Latin America. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2020 Nov [cited 2022 Feb 9];103(5):1765–72. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7646820/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Blofield M, Giambruno C, Filgueira F. Policy expansion in compressed time: Assessing the speed, breadth and sufficiency of post-COVID-19 social protection measures in 10 Latin American countries [Internet]. Santiago: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC); 2020 Sep [cited 2022 Feb 9] p. 96. (Social Policy series). Report No.: No. 235 (LC/TS.2020/112). Available from: https://www.cepal.org/en/publications/46016-policy-expansion-compressed-time-assessing-speed-breadth-and-sufficiency-post.

- 16.Busso M, Camacho J, Messina J, Montenegro G. Social protection and informality in Latin America during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLOS ONE [Internet]. 2021 Nov 4 [cited 2022 Feb 9];16(11):e0259050. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0259050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.World Bank. The Human Capital Index (HCI) [Internet]. 2020 HCI: Country Briefs and Data. 2020 [cited 2022 Mar 3]. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/human-capital.

- 18.World Bank. Out-of-pocket expenditure (% of current health expenditure) [Internet]. Latin America & Caribbean, Uruguay. [cited 2022 Oct 6]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS?locations=ZJ-UY.

- 19.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development O. Health at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2020 [Internet]. OECD iLibrary. [cited 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: ../../../../../els-2020-255-en/index.html.

- 20.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Latin America and the Caribbean countries need to spend more and better on health to be better able to face a major health emergency like COVID-19 effectively [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Oct 6]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/health/latin-america-and-the-caribbean-countries-need-to-spend-more-and-better-on-health-to-be-better-able-to-face-a-major-health-emergency-like-covid-19-effectively.htm.

- 21.Pelin Berkmen S., Che N., Internacional F.M. El Secreto Del Éxito De Uruguay Contra El COVID-19 [Internet] Blog. 2020 https://www.imf.org/es/Blogs/Articles/2020/08/03/blog-uruguays-secret-to-success-in-combating-covid-19 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 22.Division Observatorio Social de Programas e Indicadores, Direccion Nacional de Evaluacion y Monitoreo (DINEM). Indicadores basicos de desarrollo social en Uruguay. Evolucion departamental 2006-2018. [Internet]. Uruguay; 2019 Jun p. 68. Available from: https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-desarrollo-social/sites/ministerio-desarrollo-social/files/documentos/publicaciones/1645.pdf.

- 23.World Bank. Poverty Data [Internet]. Data Bank. 2017 [cited 2022 Oct 5]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/topic/poverty?locations=UY-MX-CL-AR-BR-ZJ.

- 24.Filgueira F., Pandolfi J., Gómez E., Cazulo P., Méndez G., Carneiro F., et al. Nuevo informe del Observatorio Socioeconómico y Comportamental sobre la pandemia [Internet] Observatorio Socioeconómico y Comportamental. 2021 https://cienciassociales.edu.uy/noticias-rapidas/nuevo-informe-del-observatorio-socioeconomico-y-comportamental-sobre-la-pandemia/ [cited 2022 Feb 9]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 25.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Inter-american development bank. Government at a Glance, Latin America and the Caribbean 2020, Uruguay [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/gov/gov-at-a-glance-lac-country-factsheet-2020-uruguay.pdf.

- 26.Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. European strategies for tackling social inequities in health [Internet]. The World Health Organization; 2007 [cited 2022 Feb 17]. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/social-determinants/publications/2007/european-strategies-for-tackling-social-inequalities-in-health-2.

- 27.Pan A, Liu L, Wang C, Guo H, Hao X, Wang Q, et al. Association of Public Health Interventions With the Epidemiology of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Wuhan, China. JAMA [Internet]. 2020 May 19 [cited 2022 Feb 17];323(19):1915–23. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Shadmi E, Chen Y, Dourado I, Faran-Perach I, Furler J, Hangoma P, et al. Health equity and COVID-19: global perspectives. International Journal for Equity in Health [Internet]. 2020 Jun 26 [cited 2022 Feb 17];19(1):104. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01218-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Roberts J.D., Dickinson K.L., Koebele E., Neuberger L., Banacos N., Blanch-Hartigan D., et al. Clinicians, cooks, and cashiers: Examining health equity and the COVID-19 risks to essential workers. Toxicol Ind Health. 2020 Sep;36(9):689–702. doi: 10.1177/0748233720970439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allin S, Haldane V, Jamieson M, Marchildon G, Morales-Vazquez M, Roerig M. Comparing Policy Responses to COVID-19 among Countries in the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) Region [Internet]. Washington DC: The World Bank; 2020 [cited 2022 Mar 4] p. 261. Report No.: No: AUS0001968. Available from: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail.

- 31.World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020 [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

- 32.Hale T, Angrist N, Cameron-Blake E, Hallas L, Kira B, Majumdar S, et al. Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government. [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 6]. Available from: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker.

- 33.World Health Organization. Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 17]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov).

- 34.Ministerio de Salud Argentina. Detectar [Internet]. Argentina.gob.ar. 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/coronavirus/detectar.

- 35.Ministerio de Salud. Protocolo de Coordinación para Acciones de Vigilancia Epidemiológica Durante la Pandemia COVID-19 en Chile: Estrategia Nacional de Testeo, Trazabilidad y Aislamiento [Internet]. Subsecretaría de Salud Pública División de Planificación Sanitaria Departamento de Epidemiología; 2020 Jul [cited 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Estrategia-Testeo-Trazabilidad-y-Aislamiento.pdf.

- 36.de la República P., del Uruguay O. Medidas del Gobierno para atender la emergencia sanitaria por coronavirus (COVID-19) en el transporte [Internet] Presidencia de la República Oriental del Uruguay. 2020 https://www.presidencia.gub.uy/comunicacion/comunicacionnoticias/medidas-gobierno-transporte-emergencia-sanitaria-covid19 [cited 2020 Oct 7]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 37.Presidencia de la Republica de Paraguay. Decreto No. 3451 [Internet]. Ministerio de Salud Pública y Bienestar Social; 2020. Available from: https://www.mspbs.gov.py/dependencias/portal/adjunto/41271d-DECRETO345112.pdf.

- 38.Hamilton-Davis R. 2 months after travel restrictions imposed; how TT progressed. Trinidad and Tobago Newsday [Internet] 2020 https://newsday.co.tt/2020/05/03/2-months-after-travel-restrictions-imposed-how-tt-progressed/ May 3 [cited 2020 Oct 8]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 39.Secretaria de Trabajo y Seguridad Social. En el marco de la emergencia nacional ante la amenaza de propagación de Covid-19 Se suspenden labores en el sector Público y Privado con excepciones [Internet]. Despacho de Comunicaciones y Estrategia Presidencial; 2020. Available from: https://covid19honduras.org/?q=Se-suspenden-labores-en-el-sector-Publico-y-Privado.

- 40.Haiti Libre. Haïti - Politique: Couvre-feu et mesures sanitaires peu suivies par la population [Internet]. HaitiLibre.com. 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 17]. Available from: https://www.haitilibre.com/article-30330-haiti-politique-couvre-feu-et-mesures-sanitaires-peu-suivies-par-la-population.html.

- 41.Sánchez-Ancochea D. Latin America: inequality and political instability have lessons for the rest of the world [Internet]. The Conversation. [cited 2022 Feb 17]. Available from: http://theconversation.com/latin-america-inequality-and-political-instability-have-lessons-for-the-rest-of-the-world-152929.

- 42.ILO. Labour Overview in times of COVID-19: Impact on the labour market and income in Latin America and the Caribbean [Second Edition] [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 17]. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/americas/sala-de-prensa/WCMS_756697/lang--en/index.htm.

- 43.World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. COVID–19 health equity impact policy brief: informal workers [Internet]. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 17]. Report No.: WHO/EURO:2020-1654-41405-56445. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/338203.

- 44.Greer SL. Coronavirus Politics: The Comparative Politics and Policy of COVID-19. [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Mar 7]. Available from: https://www.fulcrum.org/epubs/br86b586v?locale=en#/6/88[chapter34]!/4/2/2/2/2[ch34]/4/2/1:0.

- 45.Cook S, Ulriksen MS. Social policy responses to COVID-19: New issues, old solutions? Global Social Policy [Internet]. 2021 Dec [cited 2022 Oct 11];21(3):381–95. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/14680181211055645.

- 46.Leisering L. Social protection responses by states and international organisations to the COVID-19 crisis in the global South: Stopgap or new departure? Global Social Policy [Internet] 2021 Dec [cited 2022 Oct 11,;21(3):396–420. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/14680181211029089 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 47.The Independent Panel. The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response [Internet]. The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response. [cited 2022 Feb 17]. Available from: https://theindependentpanel.org/.

- 48.Sirleaf E.J., Clark H. Report of the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response: making COVID-19 the last pandemic. Lancet. 2021 Jul 10;398(10295):101–103. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01095-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moreira A, Hick R. COVID-19, the Great Recession and social policy: Is this time different? Soc Policy Adm [Internet]. 2021 Mar [cited 2022 Oct 11];55(2):261–79. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/spol.12679.

- 50.Ban C. Emergency Keynesianism 2.0: The political economy of fiscal policy in Europe during the Corona Crisis. Samfundsøkonomen [Internet]. 2020;(4):16–26. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7146/samfundsokonomen.v0i4.123557.

- 51.Béland D, Cantillon B, Hick R, Moreira A. Social policy in the face of a global pandemic: Policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis. Soc Policy Adm [Internet]. 2021 Mar [cited 2022 Oct 11];55(2):249–60. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/spol.12718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Greer S.L., King E.J., da Fonseca E.M., Peralta-Santos A. The comparative politics of COVID-19: The need to understand government responses. Global Public Health [Internet] 2020 Sep 1 [cited 2022 Oct 11,;15(9):1413–1416. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1783340. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khoudour D., Acuña-Alfaro J. Addressing the human mobility consequences of COVID-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean [Internet] World Bank Blogs. 2020 https://blogs.worldbank.org/peoplemove/addressing-human-mobility-consequences-covid-19-latin-america-and-caribbean [cited 2022 Feb 17]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 54.Habibi R, Burci GL, Campos TC de, Chirwa D, Cinà M, Dagron S, et al. Do not violate the International Health Regulations during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet [Internet]. 2020 Feb 29 [cited 2022 Feb 17];395(10225):664–6. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30373-1/fulltext. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Ferhani A, Rushton S. The International Health Regulations, COVID-19, and bordering practices: Who gets in, what gets out, and who gets rescued? Contemporary Security Policy [Internet]. 2020 Jul 2 [cited 2022 Feb 17];41(3):458–77. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2020.1771955.

- 56.Leung CC, Lam TH, Cheng KK. Mass masking in the COVID-19 epidemic: people need guidance. The Lancet [Internet]. 2020 Mar 21 [cited 2022 Feb 18];395(10228):945. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30520-1/fulltext. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 5 June 2020 [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 18]. Available from: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---5-june-2020.

- 58.Wenham C. What went wrong in the global governance of covid-19? BMJ [Internet]. 2021 Feb 4 [cited 2022 Feb 18];372:n303. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n303. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.World Health Organization. Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 9 April 2021 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 18]. Available from: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19-9-april-2021.

- 60.Pan American Health Organization. PAHO Director calls for closing “glaring” vaccine gap by expanding vaccine production in Latin America and the Caribbean [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 18]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/news/19-5-2021-paho-director-calls-closing-glaring-vaccine-gap-expanding-vaccine-production-latin.

- 61.Dorlach T. Social Policy Responses to Covid-19 in the Global South: Evidence from 36 Countries. Social Policy and Society [Internet] 2022 Jul 7 [cited 2022 Oct 11];1–12. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S1474746422000264/type/journal_article Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 62.Politi D. Uruguay has the world’s highest death toll per capita. The New York Times [Internet] 2021 https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/14/world/americas/uruguay-cases-deaths-coronavirus.html May 14 [cited 2022 Feb 18]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 63.Torres I., López-Cevallos D.F., Sacoto F. Elites can take care of themselves — Comment on COVID-19: the rude awakening for the political elite in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health [Internet] 2020 Jul 1 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003063. https://gh.bmj.com/content/5/7/e003063 [cited 2022 Feb 18];5(7):e003063. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Torres I, Sacoto F. Localising an asset-based COVID-19 response in Ecuador. The Lancet [Internet]. 2020 Apr 25 [cited 2020 Sep 17];395(10233):1339. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30851-5/abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Bojorquez I, Cabieses B, Arósquipa C, Arroyo J, Novella AC, Knipper M, et al. Migration and health in Latin America during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. The Lancet [Internet]. 2021 Apr 3 [cited 2022 Feb 18];397(10281):1243–5. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)00629-2/fulltext. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Han E, Tan MMJ, Turk E, Sridhar D, Leung GM, Shibuya K, et al. Lessons learnt from easing COVID-19 restrictions: an analysis of countries and regions in Asia Pacific and Europe. The Lancet [Internet]. 2020 Nov 7 [cited 2022 Feb 18];396(10261):1525–34. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140-6736(20)32007-9/fulltext. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Huber E, Nielsen F, Pribble J, Stephens JD. Politics and Inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean. American Sociological Review [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2022 Feb 18];71(6):943–63. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25472438.

- 68.Pribble J., Huber E. Social Policy and Redistribution: Chile and Uruguay. The Resurgence of the Latin American Left [Internet] 2013 Jan;1:117–138. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/polisci-faculty-publications/11 Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Centro Centroamericano de Poblacion. Satisfacción promedio con la democracia para cada país en los años 2006/7, 2008/9, 2010, 2012, 2014 y 2016. Países ordenados según ocurrencia 2016. [Internet]. AmericasBarometer. 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 18]. Available from: http://infolapop.ccp.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/nivel-satisfaccion-democracia-latam.html.

- 70.Pribble J. Uruguay quietly beats coronavirus, distinguishing itself from its South American neighbors – yet again [Internet]. The Conversation. 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 18]. Available from: http://theconversation.com/uruguay-quietly-beats-coronavirus-distinguishing-itself-from-its-south-american-neighbors-yet-again-140037.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.