Abstract

Objective:

This study aimed to describe Israeli maternity departments’ policies regarding cesarean delivery on maternal request, and factors associated with obstetricians’ support for cesarean delivery on maternal request in specific scenarios.

Methods:

This multicenter cross-sectional study included 22 maternity department directors and 222 obstetricians from the majority of Israeli hospitals. Directors were interviewed and completed a questionnaire about their department’s cesarean delivery on maternal request policy, and obstetricians responded to a survey presenting case scenarios in which women requested cesarean delivery on maternal request. The scenarios represented profiles referring to the following factors: maternal age, poor obstetric history, pregnancy complications, and psychological problems. The survey also included the obstetricians’ socio-demographic information and questions about other issues associated with cesarean delivery on maternal request. The main outcome measures were department policies regarding cesarean delivery on maternal request and obstetricians’ support for cesarean delivery on maternal request in specific cases.

Results:

Policies were divided between allowing and prohibiting cesarean delivery on maternal request (n = 10 and 12, respectively), and varied regarding issues such as informed consent and pre-surgery consultation. Most of the obstetricians (96.5%) did not support cesarean delivery on maternal request in the “reference scenario” describing a young woman with no obstetric complications. Additional factors increased the rate of support. Support was greater among obstetricians aged > 45 (odds ratio = 2.11; 95% confidence intervals 1.33–3.36) and lower among females (odds ratio = 0.58; 95% confidence intervals 0.39–0.86). Obstetricians whose department policy was less likely to allow cesarean delivery on maternal request reported lower rates of support for cesarean delivery on maternal request in most cases.

Conclusion:

Policies and obstetricians’ support for cesarean delivery on maternal request vary broadly depending on clinical profiles and physician characteristics. Department policy has an impact on obstetricians’ support for cesarean delivery on maternal request. Health policy will benefit from a framework in which the organizations, physicians, and patients are consulted.

Keywords: cesarean delivery, interview, maternal request, maternity departments, obstetricians, survey

Introduction

Cesarean delivery on maternal request (CDMR) is the delivery of a singleton infant by cesarean section based solely on maternal request in the absence of medical or obstetric indication.1 In a systematic review of CDMR rates,2 the proportion of CDMR out of total births was 3.0% (range between 0.2% and 42.0%), and out of the total cesarean deliveries (CDs), the CDMR proportion was 11% (range between 0.9% and 60.0%), with considerable variations across studies and subgroups depending on population characteristics. Upon reviewing the reasons for the relatively high rate of 28.4% in Italy, compared with other European countries, Laurita et al.3 attributed the rates to various interactions between such factors as the hyper-medicalization of delivery, legal and social issues, and attitudes toward childbirth. In a systematic review and meta-regression of the global incidence of CDMR, it was found that the economic status of the country was the primary factor associated with CDMR rates.2 High-income (HI) countries had the lowest CDMR rates compared with all other income-level categories. Strikingly, upper-middle income (UMI) countries reported 11 times the rate of CDMR compared with HI countries. A reason for this outcome, the authors suggest, is that HI countries may provide better healthcare systems; thus, confidence in the level of care may be less likely to lead to desire for physician choice; in contrast, in UMI countries, patient autonomy may play a greater role on CDMR decision-making.

Widespread public and scientific debates regarding CDMR deal with the definition, clinical aspects, and health policy. From a medical perspective, no evidence has been found upon which to base practice recommendations regarding planned CD for non-medical reasons.1,4 The debate has often centered around ethical and legal aspects.5–8

While the term CDMR implies a procedure initiated by women, the obstetrician’s role (as a facilitator or barrier) and variations in their attitudes have also been considered.5,9,10 Indeed, when considering the patient’s obstetric history and socio-demographic characteristics, as well as the obstetricians’ personal characteristics (e.g. gender and age), variations in the rates of agreement to perform CDMR have been reported.11–14 Rates of obstetricians’ support for CDMR have ranged from 15% to 22% in Brazil, France, and the Netherlands, to 67%–80% in Germany, Argentine, and the United Kingdom.14 In Israel, the rate of support among obstetricians has been reported as ranging from 40% to 79%.12

The aims of the present study were to describe Israeli maternity departments’ policies regarding CDMR, as well as to assess obstetricians’ willingness to perform CDMR in light of their personal characteristics in specific cases with various maternal obstetric scenarios. A better understanding of the factors associated with decisions regarding performing CDMR can contribute to reducing the rate of unnecessary surgical interventions.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in maternity departments of Israeli public hospitals during 2012–2013. The study included face-to-face interviews with department directors during which they responded to a questionnaire (Part 1) and a survey among obstetricians regarding their support for specific CDMR case scenarios (Part 2).

Part 1

All maternity department directors were requested by the principal investigator to be interviewed face-to-face in their offices. During the 20-min interview, they were asked to respond to questions on a structured questionnaire regarding their departments’ policy in cases in which a woman requests a CDMR, including if they would allow it at all, if a pre-surgery clinic visit would be required, if a specific CDMR informed consent had to be signed, etc. The questions were developed in consultation with heads of the Israel Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine. The questionnaire was not piloted due to the relatively small number of interviewees.

Part 2

Obstetricians were recruited at staff meetings, upon permission from the department directors, and those from 18 hospitals were included. The inclusion criterion was having worked at least 1 h weekly in the delivery room in the last year. The obstetricians were requested to complete a self-report questionnaire, which was distributed and completed during staff meetings. Completion of the questionnaire took about 15–20 min. The questionnaire included 15 “scenarios” of cases in which the women requested CDMR (Table 1). All of the women described were at 39 weeks of gestation, without any medical indication for CD, with no previous CD, carrying a healthy singleton in vertex position with an estimated weight of 3200 g (except three cases in which birthweight was > 3200). The scenarios represented profiles in which varying combinations of the following four factors were (or were not) included: A—advanced maternal Age at delivery (> 42); H—traumatic obstetric History (e.g. stillbirth, miscarriage); C—Current pregnancy complication (e.g. gestational diabetes and hypertension); and P—Psychological problems (e.g. anxiety). These factors were drawn from actual cases encountered in a previous study on CDMR.15 In that study over 400 women who underwent CDMR were compared with women who delivered vaginally, and the main variables characterizing the CDMR groups were selected for this study.

Table 1.

Study scenarios.

| Scenario | Characteristicsa: Absent (−) or Present (+) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Description | A | H | C | P |

| 1 | 25 y/o,b first pregnancy, healthy fetus, vertex position | − | − | − | − |

| 2 | 26 y/o, first pregnancy, gestational diabetes treated with insulin | − | − | + | − |

| 3 | 42 y/o, first pregnancy, no complications or background illness | + | − | − | − |

| 4 | 25 y/o, second pregnancy, no complications or background illness, history of prolonged labor and stillborn | − | + | − | − |

| 5 | 42 y/o, fifth pregnancy, no complications or background illness, history of three late miscarriages, previous vaginal delivery following prolonged labor | + | + | − | − |

| 6 | 42 y/o, third pregnancy, current gestational hypertension, requiring high-risk protocol, two previous vaginal deliveries with no complications | + | − | + | − |

| 7 | 25 y/o, first pregnancy, has been suffering from sleep disturbances throughout the pregnancy, due to anxiety because of stories she heard from friends about their difficult deliveries | − | − | − | + |

| 8 | 25 y/o, first pregnancy, taking anti-anxiety medications, gestational diabetes treated with insulin | − | − | + | + |

| 9 | 26 y/o, third pregnancy, diagnosed with gestational hypertension, requiring high-risk protocol. Previous spontaneous miscarriage and one child with severe cardiac malformation | − | + | + | − |

| 10 | 43 y/o, anesthesiologist, fifth pregnancy without complication or background illness, one livebirth 10 years previously, and three miscarriages in Week 12 | + | + | − | + |

| 11 | 42 y/o, fourth pregnancy, diagnosed gestational hypertension, three previous miscarriages in Week 12 | + | + | + | − |

| 12 | 43 y/o, second pregnancy, without complications, previous vaginal delivery without complications works in a child development clinic for children with brain injuries, and, therefore, fears delivering vaginally again | + | − | − | + |

| 13 | 26 y/o, second pregnancy, history of prolonged labor with a vacuum delivery. Suffers from anxiety disorder due to fear of another vaginal delivery | − | + | − | + |

| 14 | 43 y/o, second pregnancy, previous vaginal delivery without complication, gestational diabetes treated with insulin, sleep disturbances due to anxiety surrounding vaginal delivery | + | − | + | + |

| 15 | 27 y/o, fourth pregnancy, gestational diabetes treated with insulin, estimated fetal weight 3600 gr., two previous miscarriages, one prolonged labor with a vacuum delivery. She is anxious about another prolonged delivery that might harm the baby | − | + | + | + |

All cases were singleton, no previous cesarean deliveries, 39 weeks’ gestation, vertex presentation, estimated birthweight 3200 gr. unless otherwise noted. The letters represent the women’s characteristics by the following variables: A: advanced maternal Age; H: traumatic obstetric History; C: Current pregnancy complications; and P: Psychiatric problems (see methods).

y/o: years old.

The respondents assessed the degree to which they supported CDMR in each scenario on a 9-point Likert-type scale (1 = “highly supportive” and 9 = “not supportive at all”). The degree of support was categorized as follows: Answers in the 1–3 range were defined as “supporting the request,” 4–6 indicated “uncertainty,” and 7–9 were defined as “not supporting the request.”

The questionnaire also included items regarding obstetricians’ socio-demographic and professional characteristics, such as sex, age, seniority, country and status of residency, and current position. Additional questions related to their attitudes toward entitlement to public funding for this procedure, and whether medico-legal aspects influence their decision to perform CDMR.

Statistical analysis

Hospital policy is presented as frequencies of department directors’ responses to each question. Regarding the obste-tricians’ survey, the power calculation for the sample size (> 80%) was based on the significant differences in the rate of support (approximately double) for CDMR among categories of selected participant characteristics (sex, age, seniority). The various degrees of their support for performing CDMR are presented as percentages, and in sample scenarios, standard error is included.

For logistic analysis, degree of support (response scores 1–3) was the dependent variable, and obstetricians’ socio-demographic and professional characteristics were the independent variables. Due to the strong correlations between many of the independent variables, separate logistic regressions were conducted for each variable, adjusted for the scenario profiles. Odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by generalized estimating equation (GEE) model to control for dependence of individual obstetrician’s answer to each of the 15 cases that he or she scored. The models used 3330 observations resulting from the responses of the 222 physicians to the 15 scenarios. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Sheba Medical Center IRB, No.8671-11 SMC.

Results

Department policy regarding CDMR (Part 1)

Directors of 22 of the 29 maternity departments in Israel participated in Part 1 of the study. These departments, which serve all of Israel’s geographic areas and diverse populations, accounted for more than 87% of the 171,994 deliveries in the study year (2012).16 None of the interviewees stated that their department actually recommended the procedure (Table 2), but the responses were almost equally divided between those who would allow CDMR and those who would not recommend, but would allow it. Nearly two-thirds reported that the woman is required to visit their pre-surgery clinic for consultation regarding her decision. In addition, in some departments, staff discussions are held on each such case.

Table 2.

Department policy regarding CDMRa (n = 22).

| N | %b | |

|---|---|---|

| What is the department’s attitude toward a woman’s request for a CDMR | ||

| Does not recommend, but agrees | 10 | 45.5 |

| Does not recommend and does not agree | 12 | 54.5 |

| How does a woman book a CDa in your department? | ||

| Pre-surgery clinic | 14 | 63.6 |

| Telephone conversation | 5 | 22.7 |

| Maternity department triage upon admission to delivery room | 3 | 13.6 |

| What consent form is used in the case of CDMR? | ||

| A special consent form for CDMR | 10 | 90.9 |

| A regular consent form for CD | 1 | 9.1 |

| What are the recommendations for a repeat cesarean delivery? | ||

| Only CD | 5 | 23.8 |

| VBACa | 7 | 33.3 |

| Whatever the woman requests | 9 | 42.9 |

| What form must be signed by a woman who requests a repeat CD? | ||

| VBAC refusal form | 8 | 44.4 |

| A regular CD form | 10 | 55.6 |

| In what gestational week should CDMR be carried out? | ||

| Week 39 | 12 | 66.7 |

| Week 38 | 5 | 27.8 |

| Week 37 | 1 | 5.6 |

| From what birthweight (gr) would you recommend a CD? | ||

| 4100–4000 | 9 | 52.9 |

| 4400–4200 | 2 | 11.8 |

| 4500 | 6 | 35.3 |

| How would you relate to a 40-year-old woman after undergoing several fertility treatments? | ||

| Support for a CD, as it is a “precious pregnancy” | 12 | 60 |

| Not support a CD | 8 | 40 |

| What is your recommendation for a twin pregnancy? | ||

| Do not recommend, but agree | 13 | 76.5 |

| Recommend CD | 2 | 11.8 |

| Do not recommend and do not agree | 2 | 11.8 |

CDMR: Cesarean delivery on maternal request; CD: cesarean delivery; and VBAC: vaginal birth after cesarean.

Not including missing values.

Only three departments would allow a CDMR upon the woman’s arrival for delivery without consultation or without scheduling in advance. When the request is based only on the fact that the woman had a single previous CD, one-third of the departments recommend “vaginal birth after caesarean” (VBAC), nearly one-quarter would recommend a CD; the remainder would leave the decision up to the woman. When the request is for a primary CD, almost all respondents who mentioned informed consent stated that women are required to sign a form specifically prepared for CDMR. The policy in most departments is to perform CDMR at 39 weeks of gestation.

Obstetricians’ support for CDMR (Part 2)

In Part 2 of the study, 378 questionnaires were distributed and of these 266 were returned by obstetricians from 21 hospitals. (70.4% response rate). Forty-four questionnaires were excluded because the respondents had worked in the delivery room for less than a year. Therefore, the final study population included 222 obstetricians,

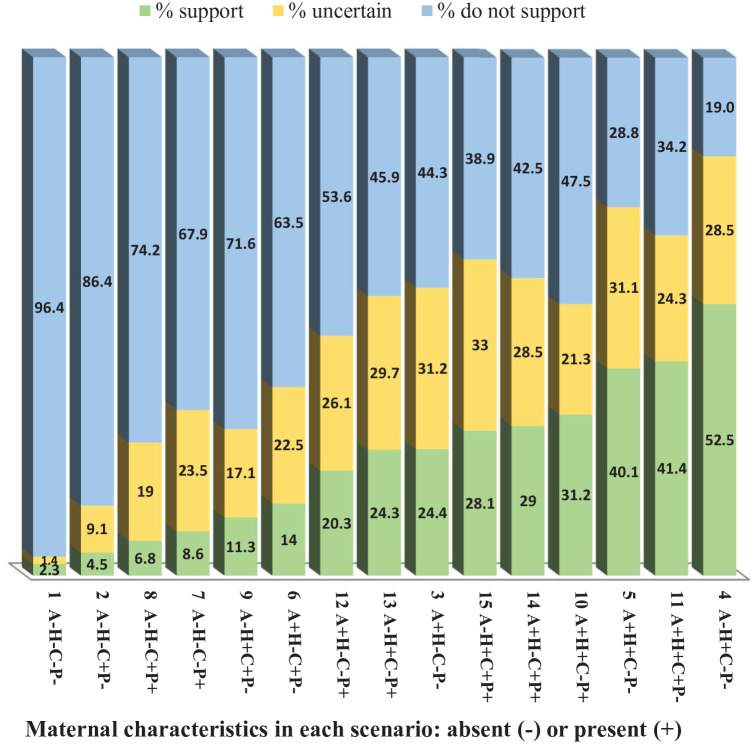

Figure 1 presents the 15 scenarios by the obstetricians’ degree of support for each. The “reference scenario” (Scenario 1) described a young woman with no obstetric complications, at 39 weeks’ gestation, with a singleton pregnancy and vertex presentation. This case received the lowest degree of support for CDMR, with only 2.3% (± 1.1%) of the respondents supporting CDMR (Scores 1–3). The vast majority did not support CDMR in this case (Scores 7–9). As compared to the reference scenario, inclusion of any single additional factor in a profile increased the degree of support. The greatest degree of support, 52.5% (± 11.3), was for the profile of a young woman without pregnancy complications but with a traumatic obstetric history that included prolonged labor and a stillbirth (Scenario 4). Only three of the respondents would support CDMR (Scores 1–3) in all of the 15 cases presented. On the contrary, 15 obstetricians would not support CDMR (Scores 7–9) in any of the cases.

Figure 1.

Rates (%) of obstetricians’ support for CDMR by maternal characteristics as presented in the scenarios.

A: advanced maternal Age at delivery (> 42); H: traumatic obstetric History; C: Current pregnancy complications; P: Psychological problems; CDMR: cesarean delivery on maternal request.

Within the group of 222 obstetricians surveyed, a majority were male, Jewish, Israeli-born, below 45 years of age, and married with children (Table 3). Regarding the professional aspect, almost all had completed their obstetric residency in Israel, and over one-third had been ob-gyn specialists for more than 10 years. A majority had over 5 years’ delivery room experience and had worked for at least 10 h weekly in the delivery room at the time of the survey. Nearly one-quarter held management positions, and over one-third held an academic position.

Table 3.

Socio-demographic and professional characteristics of obstetricians (n = 222).

| %a | n | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 27–35 | 26.1 | 58 |

| 36–45 | 32.4 | 72 |

| 46–71 | 41.5 | 92 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 63.5 | 141 |

| Female | 36.5 | 81 |

| Country of birth | ||

| Israel | 72.5 | 158 |

| Other | 27.5 | 60 |

| Religion | ||

| Jewish | 90.1 | 199 |

| Muslim | 3.6 | 8 |

| Christian | 3.6 | 8 |

| Other | 2.7 | 6 |

| Level of religious practice | ||

| Secular | 70.5 | 136 |

| Traditional | 14.0 | 27 |

| Orthodox | 15.0 | 29 |

| Ultra-orthodox | 0.5 | 1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 9.1 | 19 |

| Married | 86.6 | 181 |

| Divorced | 4.3 | 9 |

| No. of children | ||

| 0 | 13.0 | 26 |

| 1–2 | 45.0 | 90 |

| 3–5 | 42.0 | 84 |

| Country of residency | ||

| Israel | 96.7 | 202 |

| Other | 3.4 | 7 |

| Status of specialization | ||

| Residency stages 1–2 | 36.9 | 82 |

| Specialist | 63.1 | 140 |

| Management role | ||

| Yes | 22.0 | 48 |

| No | 78.0 | 170 |

| Academic position | ||

| No position | 60.3 | 114 |

| Tutor | 15.3 | 29 |

| Lecturer | 15.4 | 29 |

| Professor | 9.0 | 17 |

| Delivery room experience (years) | ||

| 1–5 | 64 | 29.4 |

| 6–15 | 77 | 35.3 |

| 16–40 | 77 | 35.3 |

| Hours per week in delivery room | ||

| 1–9 | 58 | 26.1 |

| 10–29 | 72 | 32.4 |

| 30–90 | 92 | 41.4 |

Not including missing data.

The association between socio-demographic and professional characteristics of the obstetricians and the rate of support for CDMR is presented in Table 4. Support for CDMR was significantly greater among obstetricians aged > 45, compared with those ⩽ 35 years of age. Females were significantly less likely than males to support CDMR, as were Muslim obstetricians. Those who were parents of at least three children, who had completed their obstetric residency, or had over 5 years’ delivery room experience, were also more likely to support CDMR. No significant associations were found between the probability of CDMR support and respondents, country of birth, marital status, level of religious practice, management role, country of residency, weekly hours in the delivery room, or academic positions.

Table 4.

Likelihood of obstetricians’ supporta for CDMRb by socio-demographic and professional characteristics.

| ORb,c | 95% CIb,d | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 27–35 | ref | |

| 36–45 | 1.65 | 0.92–2.93 |

| 46–71 | 2.82 | 1.70–4.66 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | ref | |

| Female | 0.53 | 0.34–0.85 |

| Country of birth | ||

| Israel | ref | |

| Other | 0.93 | 0.57–1.49 |

| Religion | ||

| Jewish | ref | |

| Muslim | 0.18 | 0.05–0.68 |

| Christian | 0.73 | 0.24–2.19 |

| Other | 0.54 | 0.13–2.26 |

| Level of religious practice | ||

| Secular | ref | |

| Traditional | 0.94 | 0.52–1.69 |

| Orthodox/Ultra-orthodox | 1.13 | 0.62–2.07 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 0.68 | 0.32–1.41 |

| Married | ref | |

| Divorced | 0.61 | 0.20–1.83 |

| No. of children | ||

| 0–2 | ref | |

| 3–5 | 2.41 | 1.51–3.85 |

| Country of residency | ||

| Israel | ref | |

| Other | 1.22 | 0.41–3.64 |

| Status of specialization | ||

| Resident | ref | |

| Specialist | 2.52 | 1.63–3.90 |

| Management role | ||

| No | ref | |

| Yes | 1.16 | 0.72–1.85 |

| Academic position | ||

| No position | ref | |

| Tutor | 1.61 | 0.83–3.13 |

| Lecturer | 1.47 | 0.61–1.61 |

| Professor | 1.30 | 0.70–2.44 |

| Delivery room experience (years) | ||

| 1–5 | ref | |

| 6–15 | 1.87 | 1.07–3.28 |

| 16–40 | 2.98 | 1.75–5.08 |

| Weekly hours in delivery room | ||

| 1–9 | ref | |

| 10–29 | 0.92 | 0.53–1.61 |

| 30–90 | 0.63 | 0.38–1.06 |

Response scores 1–3.

CDMR: cesarean delivery on maternal request; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Each variable was adjusted separately for the 15 scenarios.

Bold-faced values indicate statistical significance.

Several questions related to the respondents’ attitudes regarding CDMR. When asked if they would request CDMR for themselves or their spouse, only 4.7% of the respondents stated that they would prefer it to vaginal delivery. A majority (67.9%) thought that the expense of CDMR should be covered by the patient, not by public funding. Regarding concern for lawsuits as they relate to CDMR, 14.4% responded that this issue would influence their decision to perform CDMR often, while 48.2% that it would do so only rarely, and 37.5% that it would not influence their decision at all.

The rate of obstetricians who would agree to perform CDMR was lower among those whose department’s policy would not tend to allow the procedure, compared with those whose department’s policy would allow CDMR, and in 10 of the 15 cases, this trend was significant (Table 5).

Table 5.

Rate of obstetricians’ agreement to perform CDMRa by case scenarios and department policy.

| Scenario No. | Rate of obstetricians’ support CDMR for each scenario | P valuec | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among departments with policy allowing CDMR | Among departments with policy not allowing CDMR | ||||

| N | %b | N | %b | ||

| 89 | 100.0 | 133 | 100.0 | ||

| 1 | 4 | 3.7 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.16 |

| 2 | 7 | 6.5 | 3 | 2.7 | 0.17 |

| 3 | 33 | 61.1 | 21 | 38.9 | 0.04 |

| 4 | 64 | 59.3 | 52 | 46.0 | 0.05 |

| 5 | 53 | 49.1 | 36 | 31.6 | 0.01 |

| 6 | 21 | 19.4 | 10 | 8.8 | 0.02 |

| 7 | 15 | 13.9 | 4 | 3.5 | 0.01 |

| 8 | 9 | 8.4 | 6 | 5.3 | 0.35 |

| 9 | 17 | 15.7 | 8 | 7.0 | 0.04 |

| 10 | 44 | 41.1 | 25 | 21.9 | 0.00 |

| 11 | 49 | 45.4 | 43 | 37.7 | 0.23 |

| 12 | 30 | 27.8 | 15 | 13.2 | 0.01 |

| 13 | 32 | 29.6 | 22 | 19.3 | 0.07 |

| 14 | 40 | 37.4 | 24 | 21.1 | 0.01 |

| 15 | 35 | 32.7 | 27 | 23.7 | 0.14 |

CDMR: cesarean delivery on maternal request.

Not including missing data.

Bold-faced values indicate statistical significance.

Discussion

In the present study, directors of maternity departments in Israel were interviewed regarding their departmental policy toward CDMR, and obstetricians were surveyed about their considerations regarding CDMR. The results reflect considerable variation in hospital policy, as well as in obstetricians’ opinions.

Interviews with the maternity department directors indicated differences in the policies and practice of each center with respect to CDMR, as has been found between medical centers in previous research study.11,17 In Israel, as elsewhere, a combination of different hospital policies (or lack thereof), different populations of women, and different physician characteristics may lead to differing rates of CDMR.

It was found that both the patient profiles and the obstetricians’ personal characteristics were associated with the latter’s decision of whether or not to support CDMR. Obstetricians can make a significant (if sometimes subtle) contribution to the woman’s decision regarding mode of delivery. It has been reported that women considered the obstetrician’s opinion to be a major factor,18 and previous research in Israel highlighted the extent to which the woman’s consultation with her obstetrician influences her decision to give birth by CDMR.15 Thus, the likelihood of undergoing CDMR may be related to the attitudes of the specific obstetrician, beyond the personal and clinical characteristics of the woman. In this study, it was found that 6.3% of the obstetricians would not perform CDMR in any case. This is in comparison with the rates of obstetricians in Europe who would refuse to perform CDMR in any case: the United Kingdom 0%, Germany and Italy 2%, Sweden and the Netherlands 6%, Luxemburg 7%, France 16%, and Spain 33%.14

Only 5 of the 222 obstetricians (11%) would agree to perform CDMR in the case of a 25-year-old primipara, with a healthy fetus in a vertex position at 39 weeks of gestation. This is a considerably lower rate than that reported among obstetricians in Europe, where the proportion of those who would perform a CD at term for a woman with similar characteristics ranged from 15% to 79%.14

The obstetrician’s decision-making process is obviously not clear-cut. As seen in the individual cases illustrated in this study, every scenario is unique. There was more support if a woman had at least one of the criteria mentioned. Older women and those with a poor obstetric history were more likely to receive support for CDMR. The request of a woman with a previous stillbirth received support from over half of the obstetricians. In the European multicenter study,14 those with a previous intrapartum pregnancy loss received a higher degree of support: 60% in Spain; 67% in France; 81% in Italy; 90% or greater in Sweden, Luxembourg, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

The reasons for professionals’ attitudes toward CDMR are sometimes paradoxical. For example, in a systematic review and meta-synthesis of 34 studies,19 the potential risk of vaginal deliveries compared with CD was given by some of the respondents for positive attitudes toward CDMR, while the opposite assessment (i.e. risk of CD compared with vaginal delivery) was given by others with negative attitudes toward CDMR. In a survey of over 500 Chinese obstetricians,20 35.9% believed that it is the women’s right to decide to give birth by CD. Similarly, in a recent study of French senior obstetricians, 27.2% expressed willingness to perform non-medically indicated CD, primarily in consideration of women’s autonomy.21 An interesting finding specific to the COVID-19 pandemic22 reported that during the Wuhan lockdown, the rate of CDMR increased, although the general rate of CD was not significantly different between the pre-pandemic and lockdown periods. The reason given for this was that women wanted to reduce the time that might be required to wait for a natural birth due to concern for contracting COVID-19 infection during pre-delivery hospitalization.

With regard to the obstetricians’ characteristics, a positive association was found between their seniority and being more amenable to the woman’s request. In addition, female obstetricians and those with more children were less likely to support CDMR, as reported by others.12,14,20 In the present study, only 4.7% would prefer CD for themselves or their partners. This is similar to the rate of French residents who would prefer a vaginal trial of labor for themselves or their partner,21 but a somewhat lower rate than the 9% reported in a previous Israeli study.12

A strength of this study lies in the fact that the respondents offer a broad representation of the maternity units in Israel, accounting for 22 of the 29 departments and over 80% of the deliveries. The main limitation was in the “theoretical” nature of the survey, which did not allow for pursuing the attitudes and considerations on which the respondents’ decisions were based in actual real-time situations. Future research would do well to gain a more in-depth perspective of professional and organizational practice.

Concern has been expressed that the impact of defensive medicine on practice may influence obstetricians to pre-emptively perform CDs.8 In this study, over one-third of the obstetricians indicated that medico-legal aspects would not influence their decision to perform CDMR at all, and nearly one-half indicated that this influenced them only rarely. Similarly, in a study of French senior obstetricians,21 only four of the 83 surveyed stated that avoiding legal consequences would influence their decision to perform CDMR, In contrast, a study of British obstetric consultants23 found that over half noted fear of litigation leading to defensive medicine in such cases. Furthermore, in eight European countries surveyed,14 fear of litigation was also a prevalent reason to acceding to a woman’s request for CDMR, ranging from 33% to 89% of respondents, and in a systematic review of 34 studies on this topic among countries around the world,19 21 reported that the clinicians’ concern for litigation was the most common factor influencing the decision to perform CD. The differing attitudes toward this issue likely reflect the medico-legal aspects in the specific countries.13

In addition to the woman’s personal circumstances and the obstetrician’s characteristics and attitudes, the institution in which they work also plays a role. A Chinese study24 that found a reduced likelihood to perform CDMR among those whose hospital had measures to decrease CD rates. In the present study, the rate of agreement to perform CDMR was lower among those whose department head would not support the procedure. Research in France21 also found that OB/GYN residents shared similar attitudes toward CDMR as those of the senior OB/GYNs, and this could lead to perpetuating current practice.

With respect to the scenarios presented in this study, while the female and Muslim obstetricians were significantly less likely to support CDMR the older and more experienced ones were more likely to support CDMR. If the goal of reducing the rate of CDMR is to be advanced, it is suggested that forums for discussing these personal, cultural, and professional aspects of the issue could lead to better understanding of the factors influencing the obstetricians’ attitudes, and achieve an improved and balanced approach.

According to the OECD “Health at a Glance” reports, the rate of CD in Israel has not changed appreciably over the ensuing years. It was 15.4% in 2013,25 14.8% in 2017,26 and 15.1% in 2019.27 Similarly, the average rate for OECD countries in those years also changed only from 27.6% to 28.1% and 26.9%, respectively. Thus, in the absence of specific CDMR data, and no change in recommendations by any formal body, such as the Ministry of Health or the Israel Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, we do not have reason to believe that these data are significantly different today from when our research was conducted. Furthermore, recent research dealing with the issue of CDMR has not revealed significantly different issues or reasons for physicians’ deliberating than those raised in the present study.19–21

Conclusion

Position statements and guidelines have attempted to provide recommendations for reducing rates of unnecessary CDs without enforcing strict policy, whereby the rights of both parties (physician and patient) are respected.28–31 In addition, interventions aimed to reduce CDMR rates have been reported.32–34 These have included personal meetings between medical staff and expectant parents regarding the advantages and disadvantages of CD, requiring signing a specific CDMR informed consent form—as was reported by most of the hospitals in the present study.

This study highlights the complex issues surrounding CDMR from the organization’s and obstetrician’s perspective. It is recommended that health policy will benefit from a framework in which the organizations’, the obstetricians’, and the patients’ considerations are reflected, as well as those of health systems burdened with limited resources.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Saralee Glasser  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0084-2710

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0084-2710

Guarantor: Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The IRB committee approved this research (stated in the text: Sheba Medical Center IRB, No.8671-11 SMC.), and a waiver was provided for written informed consent by the department directors interviewed and the obstetricians surveyed. With respect to the interviews, agreement to be interviewed implied informed consent and no personal details of patients were reported. Regarding the survey, participation was voluntary and anonymous, and no personal details of patients were reported.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contribution(s): Galit Hirsh-Yechezkel: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Saralee Glasser: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Adel Farhi: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Gila Levitan: Data curation; Methodology; Project administration; Writing – original draft.

Yael Shachar: Data curation; Methodology; Project administration; Writing – original draft.

Inna Zaslavsky-Paltiel: Formal analysis; Software; Writing – review & editing.

Valentina Boyko: Formal analysis; Methodology; Software; Writing – review & editing.

Yossef Ezra: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing.

Liat Lerner-Geva: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the Israel National Institute for Health Policy Research, Grant No. 2009/53.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of data and material: Will be considered upon request.

References

- 1. National Institutes of Health. NIH state-of-the-science conference: cesarean delivery on maternal request, https://consensus.nih.gov/2006/cesareanabstracts.pdf (2006, Accessed June 28, 2022). [PubMed]

- 2. Begum T, Saif-Ur-Rahman KM, Yaqoot F, et al. Global incidence of caesarean deliveries on maternal request: a systematic review and meta-regression. BJOG 2020; 128: 798–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laurita Longo V, Odjidja EN, Beia TK, et al. “An unnecessary cut?” multilevel health systems analysis of drivers of caesarean sections rates in Italy: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020; 20(1): 770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 761 summary: cesarean delivery on maternal request. Obstet Gynecol 2019; 133(1): 226–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burrow S. On the cutting edge: ethical responsiveness to cesarean rates. Am J Bioeth 2012; 12(7): 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Williams HO. The ethical debate of maternal choice and autonomy in cesarean delivery. Clin Perinatol 2008; 35(2): 455–462viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nilstun T, Habiba M, Lingman G, et al. Cesarean delivery on maternal request: can the ethical problem be solved by the principlist approach? BMC Med Ethics 2008; 9: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheng YW, Snowden JM, Handler SJ, et al. Litigation in obstetrics: does defensive medicine contribute to increases in cesarean delivery? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2014; 27(16): 1668–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fuglenes D, Oian P, Kristiansen IS. Obstetricians’ choice of cesarean delivery in ambiguous cases: is it influenced by risk attitude or fear of complaints and litigation? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009; 200(1): 48e1–48.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O’Donovan C, O’Donovan J. Why do women request an elective cesarean delivery for non-medical reasons? A systematic review of the qualitative literature. Birth 2018; 45(2): 109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bettes BA, Coleman VH, Zinberg S, et al. Cesarean delivery on maternal request: obstetrician-gynecologists’ knowledge, perception, and practice patterns. Obstet Gynecol 2007; 109(1): 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gonen R, Tamir A, Degani S. Obstetricians’ opinions regarding patient choice in cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2002; 99(4): 577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gunnervik C, Sydsjö G, Sydsjö A, et al. Attitudes towards cesarean section in a nationwide sample of obstetricians and gynecologists. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008; 87(4): 438–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Habiba M, Kaminski M, Da Frè M, et al. Caesarean section on request: a comparison of obstetricians’ attitudes in eight European countries. BJOG 2006; 113(6): 647–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lerner-Geva L, Glasser S, Levitan G, et al. A case-control study of caesarean delivery on maternal request: who and why? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016; 29(17): 2780–2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ministry of Health. Inpatient Institutions and Day Care Units in Israel 2012 Part II: Movement of Patients by Institution and Department. 2014; Ministry of Health, Division Health Information, Jerusalem, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alnaif B, Beydoun H. Practice of primary elective cesarean upon maternal request in the commonwealth of Virginia. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2012; 41(6): 738–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Loke AY, Davies L, Mak Y-W. Is it the decision of women to choose a cesarean section as the mode of birth? A review of literature on the views of stakeholders. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019; 19(1): 286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Panda S, Begley C, Daly D. Clinicians’ views of factors influencing decision-making for caesarean section: a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies. Plos One 2018; 13(7): 1–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sun N, Yin X, Qiu L, et al. Chinese obstetricians’ attitudes, beliefs, and clinical practices related to cesarean delivery on maternal request. Women Birth 2020; 33(1): e67–e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boucherie AS, Girault A, Berlingo L, et al. Cesarean delivery on maternal request: how do French obstetricians feel about it? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2022; 269: 84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li M, Yin H, Jin Z, et al. Impact of Wuhan lockdown on the indications of cesarean delivery and newborn weights during the epidemic period of COVID-19. Plos One 2020; 15(8): e0237420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Savage W, Francome C. British consultants’ attitudes to caesareans. J Obstet Gynaecol 2007; 27(4): 354–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kwee A, Cohlen BJ, Kanhai HHH, et al. Caesarean section on request: a survey in The Netherlands. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2004; 113(2): 186–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. OECD. Health at a glance 2015-OECD indicators: caesarean sections. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26. OECD. Health at a glance health at a glance 2019-OECD indicators: cesarean sections, 10.1787/4dd50c09-en (2019, accessed 28 June 2022). [DOI]

- 27. OECD. Caesarean sections (indicator), https://data.oecd.org/healthcare/caesarean-sections.htm (2022, accessed 28 June 2022).

- 28. D’Souza R. Caesarean section on maternal request for non-medical reasons: putting the UK National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines in perspective. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2013; 27(2): 165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 761: cesarean delivery on maternal request. Obstet Gynecol 2019; 133(1): e73–e77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians Gynaecologists. Caesarean Delivery on Maternal Request (CDMR), https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Caesarean-Delivery-on-Maternal-Request-CDMR.pdf (2017, accessed 14 September 2022).

- 31. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Caesarean birth: NICE guideline [NG192] 2021, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng192/chapter/Recommendations (2021, accessed 14 September, 2022). [PubMed]

- 32. Betran AP, Temmerman M, Kingdon C, et al. Interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections in healthy women and babies. Lancet 2018; 392(10155): 1358–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kingdon C, Downe S, Betran AP. Non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean section targeted at organisations, facilities and systems: systematic review of qualitative studies. Plos One 2018; 13(9): e0203274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rosenstein MG, Chang SC, Sakowski C, et al. Hospital quality improvement interventions, statewide policy initiatives, and rates of cesarean delivery for nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex births in California. JAMA 2021; 325(16): 1631–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]