Abstract

Antibodies have been explored for decades for the delivery of small molecule cytotoxins directly to diseased cells. In antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy (ADEPT), antibodies are armed with enzymes that activate nontoxic prodrugs at tumor sites. However, this strategy failed clinically due to off-target toxicity associated with the enzyme prematurely activating prodrug systemically. We describe here the design of an antibody-fragment split enzyme platform that regains activity after binding to HER2, allowing for site-specific activation of a small molecule prodrug. We evaluated a library of fusion constructs for efficient targeting and complementation to identify the most promising split enzyme pair. The optimal pair was screened for substrate specificity among chromogenic, fluorogenic, and prodrug substrates. Evaluation of this system on HER2-positive cells revealed 7-fold higher toxicity of the activated prodrug over prodrug treatment alone. Demonstrating the potential of this strategy against a known clinical target provides the basis for a unique therapeutic platform in oncology.

Keywords: Antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy, split enzyme, complementation, prodrug, targeted delivery, HER2

The goal of targeted drug delivery is the preferential delivery of high levels of a therapeutic to a disease cell population. Delivery of potent chemotherapeutics directly to the tumor site has been a long-standing challenge in cancer therapy. Over 30 years ago, the idea of using endogenous, tumor-specific enzymes to site-specifically activate a nontoxic prodrug to a toxic chemotherapeutic was first explored.1,2 While appropriate tumor-specific enzymes have yet to be identified, the clinical use of tumor-antigen-directed monoclonal antibodies to deliver an exogenous enzyme to the tumor site was attempted, a strategy termed antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy (ADEPT). Circulation of the antibody-enzyme fusion should result in tumoral localization where activation of a prodrug can occur in the extracellular microenvironment. Tumor-specific prodrug activation is advantageous compared to covalent conjugation of small molecule drugs to an antibody due to the ability for greater quantity of drug delivery into diseased cells as the active enzyme at the tumor can turn over as much prodrug as it encounters, rather than delivery limited by the number of drugs that can be covalently bound to a targeting molecule. Further, delivery of a small molecule drug rather than a large biomolecule is expected to lead to increased tumor penetration.3 While the ADEPT concept has been widely explored in academia and industry for several decades, a product has never reached full clinical success due to two major challenges: (1) immunogenicity of nonhuman enzymes and (2) premature activation of the prodrug in serum leading to systemic toxicity.4 In recent decades, methods to decrease the immunogenicity of antibodies, exogenous proteins, and enzymes have reopened the door to the use of these nonhuman proteins;5−7 however, off-target activation has yet to be overcome. The “always on” nature of the enzymes dictates that antibody-enzyme constructs present anywhere in circulation will activate prodrug, leading to off-target drug release.

Our lab has developed a system termed target engaged complementation (TEC)8−10 for the diagnostic analysis of protein–protein interactions and analyte detection. In TEC, an enzyme is split into inactive fragments and each fragment is fused to a different antibody. The antibodies bind to two non-overlapping epitopes on the target antigen, placing the split protein fragments into proximity where they reform active enzyme. Critically, each fragment is enzymatically inactive, meaning that separated constructs are unable to activate available substrate until the enzyme is reformed. In previous studies, our lab has developed luciferase-based TEC diagnostic assays to monitor cell-surface and soluble human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (ErbB-2 or HER2).8,9

HER2 is an important and highly characterized biomarker overexpressed in breast,11 ovarian,12 and gastric13 cancers and is the target of significant diagnostic and therapeutic research efforts. The overexpression of HER2 leads to aggressive growth and is a long-standing tumor antigen for directed therapeutics, including antibodies (trastuzumab, pertuzumab, etc.) and antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs; Kadcyla and Enhertu).14 Resistance to antibody and ADC therapies has been observed,15 and lower HER2 expressing tumor cells do not respond as well to traditional HER2 therapies compared to high HER2 cell populations.16 Despite their clinical importance, ADCs still suffer from systemic and dose-limiting toxicity.17 Strategies to enable the targeted delivery of cytotoxic drugs in high levels, such as targeted enzyme activation of prodrugs, remain a critical medical need in HER2-positive cancers.

To overcome the challenges of premature activation that plagued ADEPT, we have adapted our TEC split enzyme approach to promote greater site-specific activation of a chemotherapeutic prodrug at the target site, thus reducing premature or off-target activation and toxicity. Our platform, termed complementation dependent enzyme prodrug therapy (CoDEPT), employs β-lactamase split into two inactive fragments which upon refolding can activate cephem-derived prodrugs into a toxic form. Previously, the TEM-1 β-lactamase variant was split into two fragments, amino acid residues 26–196 (N-terminal fragment, βN) containing a stability inducing M182T mutation18 and amino acid residues 198–290 (C-terminal fragment, βC).19,20 The catalytic residue Ser70 and active site residues Lys73, Asn132, Glu166, Lys234, Ser235, Arg244, and Asn276 that affect substrate affinity and spatial confirmation of the active center are divided between the N-terminal and C-terminal fragments.21−23 The split between residues 196 and 198 occurs on the face opposite to the active site.19 The split β-lactamase system has been employed as a diagnostic reporter for DNA,24,25 protein–protein interactions,20 analyte detection,26 and cytosolic peptide delivery27 and as a functional system to induce β-lactam resistance in bacteria.28

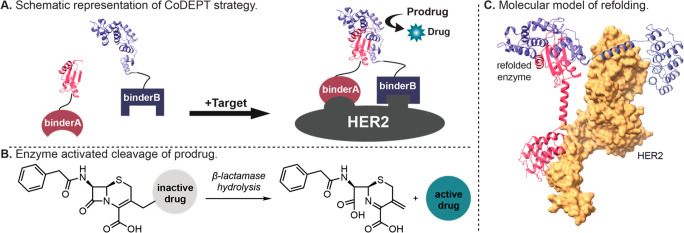

Herein we describe the development of a split enzyme approach where each β-lactamase fragment is fused to a distinct anti-HER2 antibody derivative binder. The system is designed such that the HER2 binder pairs have different epitopes so that both fusion constructs can bind HER2 simultaneously and allow for proximity-dependent refolding of the active β-lactamase enzyme (Figure 1A). After complementation, β-lactamase cleaves the lactam ring of the prodrug, resulting in the release of the active drug (Figure 1B). Critically, the split enzyme bound to different antibody partners will be active only after binding to the target tissue, resulting in minimized premature activation of prodrug and, therefore, lower off target toxicity.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the CoDEPT strategy. (A) Each binder for HER2 is fused to βN or βC. Upon simultaneous binding of the fusion constructs to distinct epitopes on HER2, β-lactamase reconstitutes into fully active enzyme allowing for (B) cleavage of prodrug to active drug. (C) Molecular approximation of complemented TEM-1 β-lactamase with example fusion constructs DARPin 9.29 to βN (βN-9.29, purple) and DARPin G3 to βC (G3-βC, pink) after binding to HER2 (yellow).

Screening of Binder Fusions to Identify the Most Promising Lead Pair

In the development of previous split enzyme-based diagnostic assays, our lab identified and validated six potential antibodies or antibody fragments that each bind to different epitopes on HER2 (Table 1).8,9 As the function of the Fc region of the antibody is not required for targeting, antibody fragments and antibody-like targeting proteins were examined for easier expression of the constructs. These include Fabs of therapeutic antibodies, designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins), and affibodies.

Table 1. Anti-HER2 Binder Name and Protein Scaffold Typea.

| Binder Name | KD (nM) | PDB | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZHER2 | 0.022 | 2KZI(solution)29 | Affibody |

| G3 | 0.9 | 2JAB(30) | DARPin |

| Pertuzumab | 1.6 | 1S78/4LLW31 | Fab |

| 9.29 | 3.8 | 4HRL(30) | DARPin |

| 73J | 8.6 | –32 | Fab |

| Trastuzumab | 0.5 | 1N8Z(33) | Fab |

Fusion of βN fragment or βC fragment at either the N- or C-terminus of each binder resulted in four constructs per binder. Each βN construct was tested with every βC construct, giving 169 pairs screened. Binding affinities are from references listed.

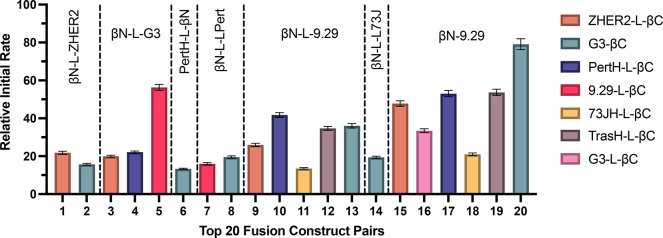

The split β-lactamase fragments βN and βC were fused to the N- and C- termini, respectively, of the HER2 binders to create the fusion constructs tested. For each binder, different constructs were created with βN or βC fused at the N- and C-termini of the binder through peptide spacers. We tested a total of 32 different binder fusions and analyzed each βC-containing binder with each βN-containing binder. See Table S1 for the complete sequences of each of the binder fusions. Using the commercially available chromogenic substrate nitrocefin, we were able to rapidly evaluate each binder fusion from expression lysate. Screening of combinations in triplicate revealed at least 30 pairs that were able to efficiently turn over nitrocefin. Figure 2 illustrates the relative initial rate of nitrocefin turnover for the best 20 binder fusion pairs. Inspection of this data indicates that efficient refolding and enzyme activity of the split enzyme were best with fusion of the βN construct at the N-terminus of the HER2 binder and fusion of the βC fragment at the C-terminus of the HER2 binder. Effective complementation was occasionally observed with fusion pairs that contained the same antibody fragment (e.g., βN-9.29 and 9.29-βC). It is likely that their activity comes from binding to HER2 homodimers on the cell surface; as HER2 is present as both monomers and dimers,34 these pairs were removed from consideration to avoid epitope binding competition. Employing a shorter linker (GGGGSG) as in G3-βC and βN-9.29 increased the turnover rate in all pairs up to 2-fold, demonstrating a linker dependence on complementation for related pairs. Initial rates and signal to background for all tested fusion pairs can be found in Table S2. Ultimately, G3-βC (βC fused to the C-terminus of binder G3) and βN-9.29 (βN fused to the N-terminus of binder 9.29) were identified as the most promising binder fusion pair and were expressed and purified for further evaluation throughout the rest of the study.

Figure 2.

Relative initial rates of top 20 binder fusion pairs evaluated by chromogenic substrate turnover on HER2-positive SKOV3 cells. Effective complementation requires N-terminal fusion of the βN fragment and C-terminal fusion of the βC fragment of the split β-lactamase. Linker L = GGSGVSGWRLFKKISGGSG. Mean ± SD, N = 3.

After identification of our optimal target binder fusion pair, G3-βC and βN-9.29, we performed molecular modeling to aid in the understanding of the possible spatial relationship of enzyme refolding around HER2 (Figure 1C). Molecular approximation indicates a plausible orientation of the fusion constructs to allow for complementation of β-lactamase. As highlighted in previous development of TEC systems, structural-binding representations such as this are useful to aid in the identification of potential fusion pairs with correct orientation and distance to allow for enzyme refolding.9 We determined the binding affinity of the fusion constructs to verify that addition of the βN or βC fragments did not affect binding to the target HER2 (see Figure S1). While we performed all studies from one expression batch of binder fusions to remove the possibility of batch-to-batch variability, we were able to express each fusion construct multiple times and observe consistent activity between batches. Since the N-terminal fragment of β-lactamase contains the catalytic serine residue, βN alone was also expressed for controls to assess independent activity. No appreciable substrate turnover from βN alone was observed under our assay conditions (see Figure S2).

HER2 Titration and Fusion Protein Optimization

With split enzyme platforms, effective targeting and complementation depends on low affinity of the split enzyme fragments to each other. In the absence of HER2, we expect low or no levels of enzyme complementation and prodrug turnover. Surprisingly, we found that self-association and refolding of the β-lactamase enzyme (termed autocomplementation) was more prominent than anticipated. To the best of our knowledge, no examination of the contributions of autocomplementation has been attempted in previous reports of split β-lactamase, despite the observation of “background” activity that is likely caused by this issue.24−26,35 It is important to note that, for a diagnostic assay, subtraction of the background levels of autocomplementation signal is possible providing that it occurs at a lesser level than the desired signal. In the case of prodrug turnover resulting in free drug building up over time, high background levels of autocomplementation could preclude this strategy from becoming clinically viable.

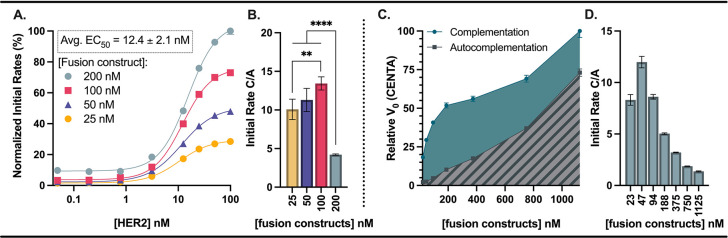

We monitored the effects of changing the concentrations of HER2 and fusion constructs to understand the concentration dependence of each component in our system. Notably, we found that a threshold of low nM HER2 was required for complementation to be faster than autocomplementation (Figure 3A–B). The concentration of HER2 required for half maximal rate of substrate turnover was calculated to be 12.4 ± 2.1 nM and was independent of fusion construct concentration. In a 96-well assay with recombinant HER2, 12.4 nM corresponds to a surface density of about 2.3 × 1012 HER2/cm2. As a rough comparison, a 10 μm diameter mammalian cell expressing 1.3 × 106 HER2 proteins36 has a surface density of about 4.1 × 1011 HER2/cm2. In a tumor environment with a multitude of cells, we anticipate this platform being able to achieve appropriate binding and activation of prodrug.

Figure 3.

HER2 concentration has a threshold for effective complementation and substrate turnover, and increasing binder fusion concentrations lead to an increased contribution from autocomplementation. A 1:1 ratio of βN-9.29 and G3-βC was used in each case. (A) The relative rates at varying HER2 concentrations are independent of fusion construct concentration. (B) Higher fusion construct loading reduces signal-to-noise as the contribution from autocomplementation increases. (C) Signal contribution from autocomplementation increases as fusion construct concentration increases. (D) Optimal signal to background (complementation/autocomplementation, C/A) was observed between 50 to 100 nM binder fusions. Mean ± SD (when not indicated, error smaller than symbols), N = 4, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

After determination of the threshold of HER2 required for efficient signal/background of complementation/autocomplementation, we determined the optimal fusion construct concentrations for HER2-dependent activation of β-lactamase prodrugs (Figure 3C–D). As we expect, increasing fusion construct concentration leads to an increase in initial rate and a larger signal contribution from autocomplementation. To better understand the background contribution of autocomplementation, we compared the complementation/autocomplementation (C/A) ratio across a range of fusion construct concentrations. At lower concentrations, there is more preferential prodrug turnover due to complemented β-lactamase relative to turnover from nonspecific complementation/binding. In the case of recombinant HER2, we found fusion construct concentrations of 50 to 100 nM to provide the highest C/A ratios. Specifically, this concentration range optimizes the amount of complemented enzyme before adding so much enzyme that autocomplementation begins to increase. Autocomplementation accounts for ∼10% of the initial rate at these concentrations.

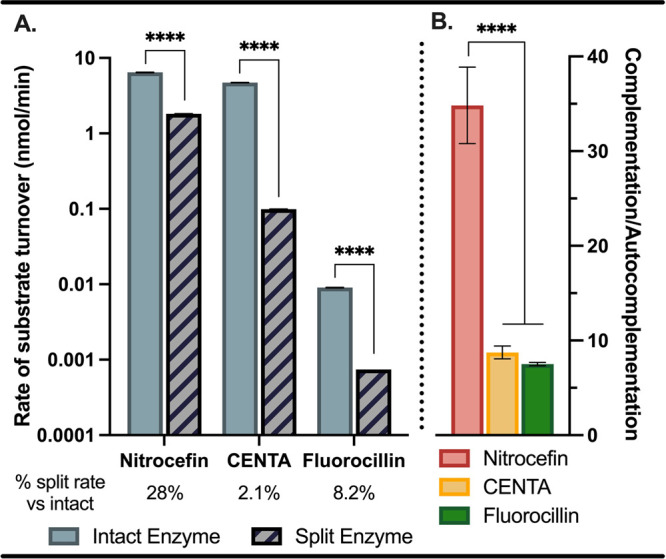

Substrate Scope of Split Enzyme Compared to Intact β-Lactamase

In addition to cytotoxins, cephalosporin-derived substrates have been developed for β-lactamase with chromophore,37,38 fluorophore,39,40 and chemiluminescent41 readouts. To gain an understanding of the substrate scope of our HER2-targeted split enzyme system, we evaluated turnover of nitrocefin and CENTA (chromophores) and fluorocillin (fluorophore) relative to an intact enzyme fusion construct (G3-TEM1). Rates adjusted to nmol/min for all substrates are shown in Table 2, including rates for untargeted activation (βN + G3-βC) and autocomplementation (βN-9.29 + G3-βC, -HER2). As highlighted in Figure 4, substrate was processed efficiently in each case with our split enzyme system. An example of the substrate time course study is shown in Figure S2 for nitrocefin turnover. As expected, the substrate turnover was slower for the split enzyme relative to the intact enzyme for all substrates. However, the magnitude of rate decrease was inconsistent, which may indicate that the binding site of the split enzyme has slightly altered structure and, therefore, altered substrate specificity compared to the parent enzyme. A general assumption is that the substrate specificity of split enzyme systems is the same as that of the intact enzyme,42 so observing differential rates in this case is surprising. This effect reiterates the importance of analyzing the split system rather than assuming that the substrate specificity is comparable to that of the parent enzyme.

Table 2. Relative Rates of Substrates with Intact Enzyme, Split Constructs, and Autocomplementationa.

| Enzyme | Nitrocefin | CENTA | Fluorocillin | C-5Fu |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G3-TEM1 | 6.44 ± 0.0559 | 4.71 ± 0.0312 | 9.0 × 10–3 ± 8.8 × 10–5 | 0.73 ± 0.11 |

| βN-9.29 + G3-βC | 1.81 ± 0.0156 | 0.099 ± 0.00038 | 7.4 × 10–4 ± 8.5 × 10–5 | 0.033 ± 0.0018 |

| βN + G3-βC | 0.034 ± 4.7 × 10–5 | 4.2 × 10–3 ± 4.8 × 10–4 | 4.9 × 10–5 ± 4.6 × 10–9 | |

| βN-9.29 + G3-βC (no HER2) | 0.033 ± 4.7 × 10–5 | 9.1 × 10–3 ± 1.9 × 10–4 | 9.9 × 10–5 ± 6.2 × 10–9 |

Slopes adjusted assuming maximum signal indicate complete substrate turnover, and turnover is given in nmol/min. Note: C-5Fu turnover was calculated using 750 nM enzyme, and the other substrates used 100 nM enzyme. Mean ± SD, N = 3.

Figure 4.

Relative rates of substrate turnover with intact and split enzyme. (A) Initial rates of substrate turnover and (B) comparative C/A ratios for split enzyme rates. Mean ± SD, N = 4, ****p < 0.0001.

In Vitro Cell Toxicity with Prodrug

In order to test the toxicity of our HER2-targeted split enzyme system, we synthesized a 5-fluorouracil prodrug, similar to payloads traditionally explored in ADEPT.43 An important design feature of the chosen cephem prodrug is that it releases unmodified drug, meaning that there is no concern of effects from additional conjugated chemical moieties on the activity of the released payload. As outlined in Figure 5A, 5-fluorouracil (5Fu) was protected by reaction with di-tert-butyl dicarbonate to give 1 in excellent yield. Subsequent reaction of 1 with commercially available cephem-derivative 2 followed by acid-mediated deprotection yielded the desired prodrug C-5Fu. Like the chromophore and fluorophore substrates, C-5Fu was efficiently converted to free drug by both intact and split enzymes (Figure 5B–C and Table 2). This synthetic strategy can be easily adapted for the conjugation of alternative small molecule payloads that have been used in ADEPT or cytotoxins that are employed for ADCs. Prodrug synthesis requires a functional handle, such as an amine or alcohol, for attaching to the cephem core. As the prodrug is designed to release unmodified drug, deleterious effects from drug modification are not expected to be a concern. In fact, it would be optimal to bind directly through the pharmacophore to improve the prodrug effect by blocking the active moieties. In evaluating a new warhead, it is critical to understand the toxicity of the prodrug to ensure that the cephem-modified compound does not maintain unacceptable toxicity.

Figure 5.

Synthesis and in vitro toxicity of split enzyme activated C-5Fu. (A) Outline of the synthesis of C-5Fu and (B) prodrug cleavage to active 5Fu. (C) Rates of C-5Fu activation in the presence of intact or split enzymes and (D) inhibitory concentration curves of prodrug, prodrug activated with split enzyme or intact enzyme, and 5-Fu positive control. Dashed lines indicate cellular toxicity from anti-HER2 antibodies of the intact or split enzyme constructs in the absence of prodrug.29 Mean ± SD, N = 3, ***p < 0.001.

We next tested our C-5Fu prodrug on the high-HER2-expressing gastric cancer cell line NCI-N87 to determine the difference in toxicity between the free drug and the parent compound. As shown in Figure 5D and Figure S4, we observed an IC50 for prodrug of 16.31 μM (95% CI = 7.7 to 27.31 μM) relative to a 300-fold change in IC50 for free drug of 0.052 μM (95% CI = 0.034 to 0.10 μM). In an in vitro cell assay, we determined that at least 300 μM enzyme was necessary to observe substrate turnover. This increase is likely due to a decrease in relative amounts of HER2 in the cellular concentrations required to run a viability assay in 96-well plates. For pilot studies, we evaluated the cytotoxicity of our CoDEPT system (βN-9.29 + G3-βC + C-5Fu) compared to the HER2-targeted intact enzyme (G3-TEM1 + C-5Fu). Gratifyingly, both the split enzyme and intact enzyme systems led to a significant decrease in prodrug toxicity proving that our system can be used to activate prodrug and result in cellular toxicity. In addition to investigating the in vivo applications of this platform, ongoing efforts are focused on exploring the use of further cephem-based prodrugs and the application of alternative split enzyme systems in the CoDEPT platform.

In this study, we have described the development and evaluation of a complementation dependent enzyme prodrug therapy (CoDEPT) capable of minimizing the intolerable off-target toxicity observed in ADEPT. We have demonstrated HER2-dependent complementation of our fusion constructs that leads to targeted substrate turnover. Importantly, differences in substrate specificity are observed in the split enzyme system relative to the parent enzyme, indicating that future substrate development should be performed on the split enzyme. Finally, we were able to successfully demonstrate efficacy using the split enzyme system in an in vitro model, reaching toxicity levels comparable to the targeted intact enzyme and achieving a 7-fold increase in toxicity over the prodrug. The conditional activation of drug from binding-dependent enzyme activation has the potential to overcome limitations that prevented clinical use of ADEPT and similar approaches. Next iterations of this approach should focus on decreasing the level of autocomplementation through protein engineering and/or by developing more potent prodrugs to allow lower concentrations of enzyme needed, while also preventing unwanted immunogenicity and thereby facilitating clinical translation. Successfully demonstrating the CoDEPT strategy against a known target antigen has the field-shifting potential of creating a unique therapeutic platform applicable to oncology and other clinically relevant applications.

Acknowledgments

We thank Morgan Marsh, a graduate student in the Department of Molecular Pharmaceutics, and Katelyn Pyper, an undergraduate student in Biomedical Engineering, for their help in expressing and purifying some of the binders. We appreciate Hsiao-nung Chen in the Chemistry Mass Spectrometry Core Facilities and Jaclyn Winter for generous access to UPLC-MS instrumentation.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 5Fu

5-fluorouracil

- ADC

antibody drug conjugate

- ADEPT

antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy

- CoDEPT

complementation dependent enzyme prodrug therapy

- C/A

complementation to autocomplementation ratio

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- TEC

target engaged complementation

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00394.

Experimental procedures and characterization of synthesized compounds; methods for recombinant protein and cell-based assays; supplemental figures and data tables for fusion constructs, including binding affinity, substrate turnover, consumption of C-5Fu, absolute IC50, and NMR. (PDF)

Author Contributions

Christine S. Nervig: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—revision and editing. Samuel T. Hatch: methodology, investigation. Shawn C. Owen: acquisition of funding, conceptualization, supervision, writing—revision and editing

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of NIH R01GM134069-04, the American Foundation of Pharmaceutical Education (Nervig), a PEO Scholar Award (Nervig), and the University of Utah Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program (Hatch).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bagshawe K.; Springer C.; Searle F.; Antoniw P.; Sharma S.; Melton R.; Sherwood R. A cytotoxic agent can be generated selectively at cancer sites. Br. J. Cancer 1988, 58 (6), 700–703. 10.1038/bjc.1988.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senter P. D.; Saulnier M. G.; Schreiber G. J.; Hirschberg D. L.; Brown J. P.; Hellström I.; Hellström K. E. Anti-tumor effects of antibody-alkaline phosphatase conjugates in combination with etoposide phosphate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1988, 85 (13), 4842–4846. 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K.; Takaoka A. Comparing antibody and small-molecule therapies for cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6 (9), 714–727. 10.1038/nrc1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S. K.; Bagshawe K. D. Antibody Directed Enzyme Prodrug Therapy (ADEPT): Trials and tribulations. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2017, 118, 2–7. 10.1016/j.addr.2017.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. D.; Crompton L. J.; Carr F. J.; Baker M. P.. Deimmunization of Monoclonal Antibodies. In Therapeutic Antibodies: Methods and Protocols; Dimitrov A. S., Ed.; Humana Press, 2009; pp 405–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvat R. S.; Verma D.; Parker A. S.; Kirsch J. R.; Brooks S. A.; Bailey-Kellogg C.; Griswold K. E. Computationally optimized deimmunization libraries yield highly mutated enzymes with low immunogenicity and enhanced activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114 (26), E5085–E5093. 10.1073/pnas.1621233114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osipovitch D. C.; Parker A. S.; Makokha C. D.; Desrosiers J.; Kett W. C.; Moise L.; Bailey-Kellogg C.; Griswold K. E. Design and analysis of immune-evading enzymes for ADEPT therapy. Protein Engineering, Design and Selection 2012, 25 (10), 613–624. 10.1093/protein/gzs044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon A. S.; Kim S. J.; Baumgartner B. K.; Krippner S.; Owen S. C. A Tri-part Protein Complementation System Using Antibody-Small Peptide Fusions Enables Homogeneous Immunoassays. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7 (1), 8186. 10.1038/s41598-017-07569-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. J.; Dixon A. S.; Owen S. C. Split-enzyme immunoassay to monitor EGFR-HER2 heterodimerization on cell surfaces. Acta Biomaterialia 2021, 135, 225–233. 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. J.; Dixon A. S.; Adamovich P. C.; Robinson P. D.; Owen S. C. Homogeneous Immunoassay Using a Tri-Part Split-Luciferase for Rapid Quantification of Anti-TNF Therapeutic Antibodies. ACS Sens 2021, 6 (5), 1807–1814. 10.1021/acssensors.0c02642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J. S.; Fletcher J. A.; Bloom K. J.; Linette G. P.; Stec J.; Symmans W. F.; Pusztai L.; Hortobagyi G. N. Targeted therapy in breast cancer: the HER-2/neu gene and protein. Mol. Cell Proteomics 2004, 3 (4), 379–398. 10.1074/mcp.R400001-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine J. N.; Wiegand K. C.; Vang R.; Ronnett B. M.; Adamiak A.; Köbel M.; Kalloger S. E.; Swenerton K. D.; Huntsman D. G.; Gilks C. B.; Miller D. M. HER2 overexpression and amplification is present in a subset of ovarian mucinous carcinomas and can be targeted with trastuzumab therapy. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 433. 10.1186/1471-2407-9-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen J. T. Role of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 in gastric cancer: biological and pharmacological aspects. World J. Gastroenterol 2014, 20 (16), 4526–4535. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i16.4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesca M. G.; Vian L.; Cristóvão-Ferreira S.; Pondé N.; de Azambuja E. HER2-positive advanced breast cancer treatment in 2020. Cancer Treatment Reviews 2020, 88, 102033. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barok M.; Joensuu H.; Isola J. Trastuzumab emtansine: mechanisms of action and drug resistance. Breast Cancer Res. 2014, 16 (2), 209. 10.1186/bcr3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarantino P.; Gandini S.; Nicolò E.; Trillo P.; Giugliano F.; Zagami P.; Vivanet G.; Bellerba F.; Trapani D.; Marra A.; Esposito A.; Criscitiello C.; Viale G.; Curigliano G. Evolution of low HER2 expression between early and advanced-stage breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 163, 35–43. 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters J. C.; Nickens D. J.; Xuan D.; Shazer R. L.; Amantea M. Clinical toxicity of antibody drug conjugates: a meta-analysis of payloads. Investigational New Drugs 2018, 36 (1), 121–135. 10.1007/s10637-017-0520-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W.; Palzkill T. A natural polymorphism in beta-lactamase is a global suppressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997, 94 (16), 8801–8806. 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarneau A.; Primeau M.; Trudeau L.-E.; Michnick S. W. β-Lactamase protein fragment complementation assays as in vivo and in vitro sensors of protein-protein interactions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002, 20 (6), 619–622. 10.1038/nbt0602-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrman T.; Kleaveland B.; Her J.-H.; Balint R. F.; Blau H. M. Protein-protein interactions monitored in mammalian cells via complementation of β-lactamase enzyme fragments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99 (6), 3469–3474. 10.1073/pnas.062043699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y.; Li Z.; Xu C.; Qin W.; Wu Q.; Wang X.; Cheng X.; Li L.; Huang W. Fluorogenic Probes/Inhibitors of β-Lactamase and their Applications in Drug-Resistant Bacteria. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (1), 24–40. 10.1002/anie.202006635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippon A.; Slama P.; Dény P.; Labia R. A Structure-Based Classification of Class A β-Lactamases, a Broadly Diverse Family of Enzymes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 29 (1), 29–57. 10.1128/CMR.00019-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N. G.; Shanker S.; Prasad B. V.; Palzkill T. Structural and biochemical evidence that a TEM-1 beta-lactamase N170G active site mutant acts via substrate-assisted catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284 (48), 33703–33712. 10.1074/jbc.M109.053819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi A. T.; Stains C. I.; Ghosh I.; Segal D. J. Sequence-Enabled Reassembly of β-Lactamase (SEER-LAC): A Sensitive Method for the Detection of Double-Stranded DNA. Biochemistry 2006, 45 (11), 3620–3625. 10.1021/bi0517032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J. R.; Stains C. I.; Segal D. J.; Ghosh I. Split beta-lactamase sensor for the sequence-specific detection of DNA methylation. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79 (17), 6702–6708. 10.1021/ac071163+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F.; Alesand V.; Nygren P. Site-Specific Photoconjugation of Beta-Lactamase Fragments to Monoclonal Antibodies Enables Sensitive Analyte Detection via Split-Enzyme Complementation. Biotechnol J. 2018, 13 (7), e1700688 10.1002/biot.201700688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone S. R.; Heinrich T.; Juraja S. M.; Satiaputra J. N.; Hall C. M.; Anastasas M.; Mills A. D.; Chamberlain C. A.; Winslow S.; Priebatsch K.; Cunningham P. T.; Hoffmann K.; Milech N. β-Lactamase Tools for Establishing Cell Internalization and Cytosolic Delivery of Cell Penetrating Peptides. Biomolecules 2018, 8 (3), 51. 10.3390/biom8030051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J. C.; Young L. M.; Mahood R. A.; Jackson M. P.; Revill C. H.; Foster R. J.; Smith D. A.; Ashcroft A. E.; Brockwell D. J.; Radford S. E. An in vivo platform for identifying inhibitors of protein aggregation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12 (2), 94–101. 10.1038/nchembio.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost C.; Schilling J.; Tamaskovic R.; Schwill M.; Honegger A.; Plückthun A. Structural Basis for Eliciting a Cytotoxic Effect in HER2-Overexpressing Cancer Cells via Binding to the Extracellular Domain of HER2. Structure 2013, 21 (11), 1979–1991. 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekerljung L.; Lindborg M.; Gedda L.; Frejd F. Y.; Carlsson J.; Lennartsson J. Dimeric HER2-specific affibody molecules inhibit proliferation of the SKBR-3 breast cancer cell line. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 377 (2), 489–494. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lua W.-H.; Ling W.-L.; Yeo J. Y.; Poh J.-J.; Lane D. P.; Gan S. K.-E. The effects of Antibody Engineering CH and CL in Trastuzumab and Pertuzumab recombinant models: Impact on antibody production and antigen-binding. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8 (1), 718. 10.1038/s41598-017-18892-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen S. C.; Patel N.; Logie J.; Pan G.; Persson H.; Moffat J.; Sidhu S. S.; Shoichet M. S. Targeting HER2+ breast cancer cells: Lysosomal accumulation of anti-HER2 antibodies is influenced by antibody binding site and conjugation to polymeric nanoparticles. J. Controlled Release 2013, 172 (2), 395–404. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H. S.; Mason K.; Ramyar K. X.; Stanley A. M.; Gabelli S. B.; Denney Jr D. W.; Leahy D. J. Structure of the extracellular region of HER2 alone and in complex with the Herceptin Fab. Nature 2003, 421 (6924), 756–760. 10.1038/nature01392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peckys D. B.; Hirsch D.; Gaiser T.; de Jonge N. Visualisation of HER2 homodimers in single cells from HER2 overexpressing primary formalin fixed paraffin embedded tumour tissue. Mol. Med. 2019, 25 (1), 42. 10.1186/s10020-019-0108-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J. R.; Stains C. I.; Jester B. W.; Ghosh I. A General and Rapid Cell-Free Approach for the Interrogation of Protein-Protein, Protein-DNA, and Protein-RNA Interactions and their Antagonists Utilizing Split-Protein Reporters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130 (20), 6488–6497. 10.1021/ja7114579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. Y.; Perry S. R.; Muniz-Medina V.; Wang X.; Wetzel L. K.; Rebelatto M. C.; Hinrichs M. J. M.; Bezabeh B. Z.; Fleming R. L.; Dimasi N.; Feng H.; Toader D.; Yuan A. Q.; Xu L.; Lin J.; Gao C.; Wu H.; Dixit R.; Osbourn J. K.; Coats S. R. A Biparatopic HER2-Targeting Antibody-Drug Conjugate Induces Tumor Regression in Primary Models Refractory to or Ineligible for HER2-Targeted Therapy. Cancer Cell 2016, 29 (1), 117–129. 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.; Hesek D.; Mobashery S. A Practical Synthesis of Nitrocefin. Journal of Organic Chemistry 2005, 70 (1), 367–369. 10.1021/jo0487395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebrone C.; Moali C.; Mahy F.; Rival S.; Docquier J. D.; Rossolini G. M.; Fastrez J.; Pratt R. F.; Frère J. M.; Galleni M. CENTA as a chromogenic substrate for studying beta-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45 (6), 1868–1871. 10.1128/AAC.45.6.1868-1871.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlokarnik G.; Negulescu P. A.; Knapp T. E.; Mere L.; Burres N.; Feng L.; Whitney M.; Roemer K.; Tsien R. Y. Quantitation of Transcription and Clonal Selection of Single Living Cells with β-Lactamase as Reporter. Science 1998, 279 (5347), 84–88. 10.1126/science.279.5347.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rukavishnikov A.; Gee K. R.; Johnson I.; Corry S. Fluorogenic cephalosporin substrates for β-lactamase TEM-1. Anal. Biochem. 2011, 419 (1), 9–16. 10.1016/j.ab.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maity S.; Wang X.; Das S.; He M.; Riley L. W.; Murthy N. A cephalosporin-chemiluminescent conjugate increases beta-lactamase detection sensitivity by four orders of magnitude. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56 (24), 3516–3519. 10.1039/C9CC09498A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S. A.; Wells J. A.. Chapter Twelve - Split enzymes: Design principles and strategy. In Methods in Enzymology; Tawfik D. S., Ed.; Academic Press, 2020; Vol. 644, pp 275–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham R.; Aman N.; von Borstel R.; Darsley M.; Kamireddy B.; Kenten J.; Morris G.; Titmas R. Conjugates of COL-1 monoclonal antibody and β-D-galactosidase can specifically kill tumor cells by generation of 5-fluorouridine from the prodrug β-D-galactosyl-5-fluorouridine. Cell Biophysics 1994, 24–25 (1–3), 127–133. 10.1007/BF02789223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.