Abstract

Janus kinases (JAK) play a critical role in JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling pathways that mediate immune response and cell growth. From high-throughput screening (HTS) hit to lead optimization, a series of pyrimidine compounds has been discovered as potent JAK1 inhibitors with selectivity over JAK2. Cell-based assays were used as primary screening methods for evaluating potency and selectivity, the results were further assessed and confirmed by biochemical and additional cellular assays for lead molecules. Also discussed is the unique correlation between a trifluomethyl group and CYP3A4 inhibition in the presence of NADPH, the activity of which was successfully decreased with the reduction of fluoro-atoms, increasing IC50 from 0.5 μM to >10 μM. The development of novel and scalable synthetic routes for amino-phenyl intermediates was essential for the discovery of late-stage lead molecules, including clinical candidate R507 (33). In preclinical studies, 33 exhibited great efficacy in mouse studies by inhibiting IFNγ expression induced by IL-2 and in a rat collagen-induced arthritis disease model.

Keywords: JAK inhibitor, JAK1, kinase inhibitor, pyrimidine

Janus kinases (JAK) are a family of tyrosine kinases that, after phosphorylation, bind and activate various signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins, and mediate signaling from a broad range of cell surface receptors, which regulate a variety of biological processes, including various immune responses, cell proliferation, and hematopoiesis. Many JAK inhibitors have been approved worldwide for the treatment of immune-related diseases and conditions, as well as for oncology indications.1−6

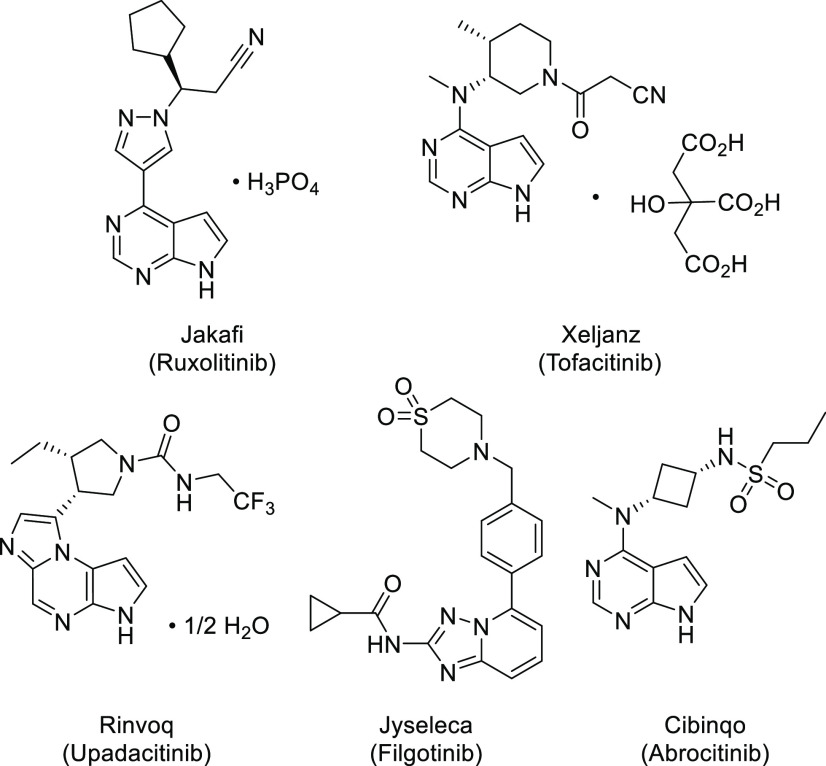

There are four known kinases in the JAK family, which are JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2. The very first two marketed JAK inhibitors, ruxolitinib and tofacitinib (Figure 1), approved in 2011 and 2012, respectively, are not selective within JAK family kinases. Certain adverse events, for example, thrombosis, which was observed with both ruxolitinib and tofacitinib treatments,1 are believed to be associated with inhibition of JAK2 kinase, which controls signaling of hematopoietic growth factors, including erythropoietin (EPO) and thrombopoietin (TPO), among others.1,4 Since then, industry efforts have been focused on the development of selective JAK inhibitors, especially over JAK2 kinase, for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. The first JAK1 selective inhibitor, upadacitinib (Figure 1), was launched in 2019 for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. More recently, in 2020, JAK1 selective inhibitor filgotinib (Figure 1) was approved for rheumatoid arthritis and ulcerative colitis treatment, and in 2021, another JAK1 selective drug, abrocitinib (Figure 1), was launched for atopic dermatitis therapy. We initiated efforts for the development of selective JAK inhibitors after the approval of the first two JAK inhibitors and here would like to report our journey for the discovery of R507, a JAK1 selective inhibitor for the treatment of immune related diseases or disorders.

Figure 1.

Selected approved JAK inhibitors.

Based on earlier publications, the binding affinity for each subtype in the JAK family seemed to vary depending on assay methods and conditions7,8 and did not always track with results obtained from cellular functional assays although efforts have been made to better understand the disconnections.9 Over the years, with better understanding of JAK signaling pathways, biological assays have also evolved, but the understanding of how in vitro selectivity studies would predict clinical outcomes still remains challenging.10 Thus, we have decided to use cell-based assays as primary screening methods to measure different kinase activities for potency and selectivity, and the results will be further confirmed by biochemical and additional cellular assays for the lead molecule.

It has been well established that certain cytokines, for example, IL-2, can activate JAK1 or JAK3 kinase, which upon phosphorylation, binds STAT5 proteins and initiates the signaling pathways that regulate immune response and cell proliferation. To characterize JAK1/3 inhibitors functionally,11 we used cell-based assays that measure the inhibition of STAT5 phosphorylation and the cell proliferation of human primary T-cells when induced by IL-2.12,13 Since the inhibition of JAK2 kinase is associated with anemia, thrombocytopenia, hyperlipidemia, and neutropenia, it is desirable to develop JAK1/3 inhibitors with selectivity over JAK2. It is also known that JAK2 kinase is involved in survival of erythroid precursor cells, which give rise to mature red blood cells, upon activation by erythropoietin (EPO); thus, a cell-based assay measuring survival of cultured human erythroid precursor cells (CHEP) was used to evaluate the activity for JAK2 inhibition.14,15

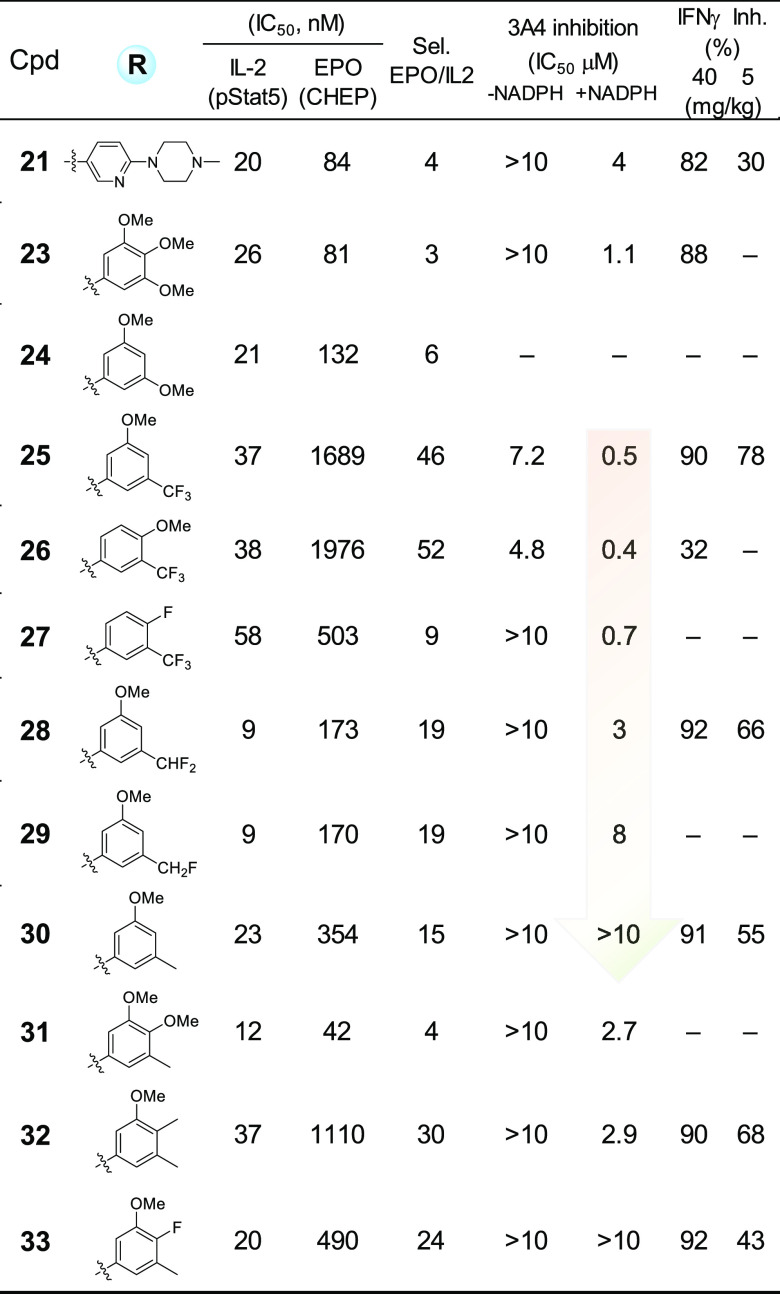

High-throughput screening (HTS) of the company’s compound library identified initial hits as exemplified by molecules 1–3 (Figure 2). These compounds showed promising on-target JAK1/3 activities in the IL-2 cell-based assay for the inhibition of STAT5 phosphorylation in primary T-cells. Compounds 1–3 have 2,4-diaminopyrimidine as a core structure that binds to the hinge in ATP binding pocket and a 6,6-bicyclic moiety and a 3-sulfonamide-phenyl group connected to the 4-amino and 2-amino groups, respectively. While having gem-dimethyl (2) or gem-difluoro (3) substitutions next to a carbonyl group might help with chemical stability for preventing the opening of the lactam ring, the IL2 cell potency of these two compounds did not seem to be significantly different from unsubstituted compound 1. On the other hand, higher molecular weight (compounds 2 and 3) might result in unfavored physicochemical properties. Thus, we decided to explore the SAR of the molecules by removing that carbon atom along with its substituents, to find out the impact of resulting 5,6-bicyclic systems on potency, selectivity, and PK properties.

Figure 2.

HTS hits: compounds as JAK1/3 inhibitors.

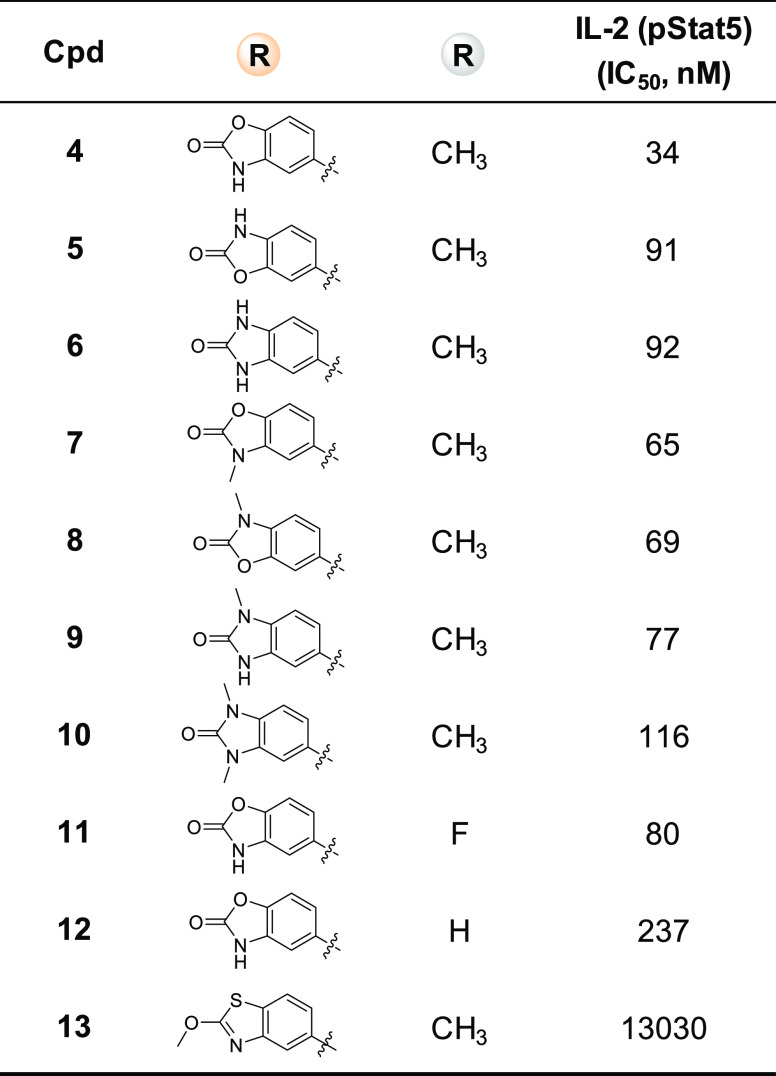

Compound 4 (Table 1), with a 5-aminobenzo[d]oxazol-2(3H)-one moiety substituted at the 4-position of the pyrimidine, was synthesized as a direct analogue of compound 1. This new molecule, 4, retained IL-2 cell potency as compared with its 6,6-bicyclic analogue 1. Interestingly, its carbamate regioisomer 5 and urea analogue 6 lost IL-2 potency by ∼3-fold. Compound 7, an N-methyl analogue of compound 4, is slightly less potent. Compounds 8 and 9, mono-N-methyl analogues of 5 and 6, respectively, marginally regained some IL-2 activity but are still less potent than compound 4. Similarly, dimethyl cyclic-urea compound 10 is less potent than its monomethyl analogue 9 and parent molecule 6. Compounds 11 and 12, with fluoro or no substituent at the 5-position of the pyrimidine, showed reduced potency in comparison to the 5-methyl-pyrimidine analogue 4. Drastic change to the 5,6-bicyclic systems, such as compound 13, caused complete loss of IL-2 potency.

Table 1. Compounds with Various 5,6-Bicyclic Systems.

Since HTS hit molecules 1–3 were originally made as spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) inhibitors, new compound 4 was tested in a cell-based assay measuring immunoglobulin M (IgM) stimulated inhibition of phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activity, which is part of SYK signaling pathways. In this assay, compound 4 showed much less activity than molecule 1 (IC50 = 0.7 μM), with IC50 = 5 μM.

Encouraged by the IL-2 cell potency and selectivity over SYK kinase, compound 4 was further evaluated for plasma protein binding and in IL-2 induced IFNγ inhibition16−18 mouse model studies. Molecule 4 appeared to have high plasma protein binding in both rat (97%) and human (96%) species and have relatively low in vivo efficacy with 30% inhibition at 40 mg/kg dosage (Table 2). We believe, for compound 4, high topological polar surface area (TPSA), which is associated with the sulfonamide moiety, and a high calculated LogD value (cLogD = 3.7 at pH 7, data not shown in Table 2) might have at least in part contributed to low in vivo efficacy. More compounds were made by varying substituents at the 2-position of the pyrimidine (Table 2), focusing on improving physicochemical properties of the molecules, which hopefully would result in better PK properties and in vivo efficacy, while at the same time examining their impact on IL-2 potency. Compound 14, with a p-sulfonamide substituent, is about 3-fold less potent than its m-analogue 4. Compounds 15 and 16, with reversed-sulfonamide substituents and lower TPSA, have similar IL-2 cell potency as compound 4, but somehow their in vivo efficacy dropped significantly. Compounds 17 and 18, with further lowered TPSA values, have better IL-2 potency regardless of substituent positions. Further profiling of m-sulfone analogue 17 revealed slightly lowered plasma protein binding and better in vivo efficacy compared with compound 4. For compounds 19 and 20, with m-CN or p-CN substitutions and further lowered TPSA values, their in vivo efficacies were rather disappointing. Finally, compounds 21 and 22, having N-methyl-piperazine or morpholine-substituted pyridine moieties, with relatively low TPSA and cLogD values (cLogD, pH 7, 3.1, and 2.2, respectively, data not shown in Table 2), exhibited decreased plasma protein binding and good efficacy in acute animal model studies for compound 21, although the results from morpholine analogue 22 were still unsatisfactory, despite their similar IL-2 cell potency. Further in vivo PK studies revealed 4% oral bioavailability in rat (with 0.25% CMC as po vehicle) for compound 21 and <1% oral bioavailability for compound 22. It became clear to us, for this scaffold of molecules, that improvement of single or even multiple physicochemical properties alone might not be enough to improve in vivo efficacy.

Table 2. Compounds to Improve Physicochemical Properties.

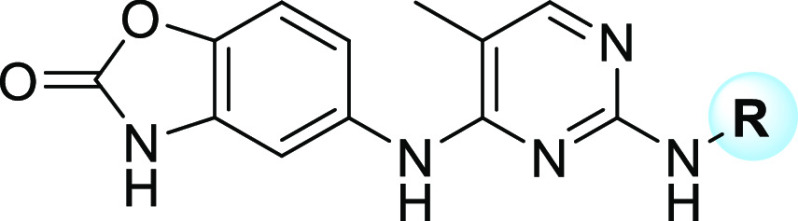

Compound 21 was further examined for selectivity over JAK2 kinase in an EPO cell-based assay and showed an IC50 of 84 nM, making it only 4-fold selective with respect to IL-2 cell potency (Table 3). At a lower dose of 5 mg/kg, compound 21 showed 30% inhibition of IFNγ production in vivo and did not appear to be a CYP3A4 inhibitor, both in the absence or presence of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). Compounds 23 and 24, with 3,4,5-trimethoxy and 3,5-dimethoxy-phenyl moieties incorporated into the molecules, are potent IL-2 inhibitors, but both compounds failed to improve JAK2 selectivity in an EPO assay. When one methoxy group was replaced by CF3, as in compound 25, EPO selectivity was considerably increased to 46-fold, and the molecule exhibited great efficacy in acute animal model studies at both doses (Table 3). However, compound 25 appeared to be a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor in the presence of NADPH with an IC50 of 0.5 μM, indicating a possible mechanism based P450 inhibition from its metabolite(s). Replacement of the potentially metabolically labile methyl group in methoxy with a more stable isopropyl or cyclo-butyl caused loss of IL-2 potency, with IC50 values of 1.5 μM and 3.9 μM, respectively. Intriguingly, both compounds 26 and 27, having a methoxy- or fluoro-substituent at the para-position to the amino group, also showed potent CYP3A4 inhibition in the presence of NADPH, regardless of their differences in potency, selectivity over JAK2, or in vivo efficacy.

Table 3. SAR through Multiparameter Optimizations.

It became noticeable that all three compounds, 25–27, share one common structural feature, which is having a CF3 group substituted at the 3-position of the phenyl ring. To test the hypothesis that the m-CF3 group is the cause for potent CYP3A4 inhibition in the presence of NADPH, compounds 28–30 (Table 3) were prepared by replacing CF3 with CF2H, or CFH2, or CH3. To our pleasant surprise, in the presence of NADPH, CYP3A4 inhibition was decreased with the reduction of fluoro-atoms at that position (Table 3), with IC50 increasing from 0.5 μM for compound 25, to 3 μM for compound 28, 8 μM for compound 29, and >10 μM for compound 30. All three new molecules (28, 29, 30) have better IL-2 cell potency than compound 25, albeit slightly decreased selectivity over JAK2 in the EPO assay. Compounds 28 and 30 also showed good efficacy in acute animal model studies at both doses. Follow-up compounds 31, 32, and 33 (Table 3) were synthesized by adding another substituent between the methyl and methoxy groups. Although compounds 31 and 32 showed more CYP3A4 inhibition than compound 30 in the presence of NADPH, compound 32 regained selectivity over JAK2 in the EPO assay and is more efficacious in acute animal studies at a lower 5 mg/kg dose.

As for compound 33, with good potency in the IL-2 cell assay and 24-fold selectivity over JAK2 in EPO functional assay, it does not show CYP3A4 inhibition in the presence of NADPH, although it is less efficacious in mouse models at 5 mg/kg in comparison with 32. Both compounds 32 and 33 showed weak inhibition for CYP1A2 with Ki of 6–9 μM and 1–3 μM, respectively, but did not show inhibition against CYP2D6 and CYP2C19. In biochemical assays for JAK family kinases (Invitrogen Z′-LYTE), 33 showed IC50 values of 2.1 nM, 12 nM, 923 nM, and 12 nM for JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2, respectively (Table 4). Compound 33 also has acceptable kinase selectivity (Supporting Information), including <50% inhibition for SYK kinase (at 250 nM concentration), which supports the low SYK cell-based potency observed for early lead molecule 4.

Table 4. Additional in Vitro Characterizations of 33 (IC50, nM).

| Biochemical Assays | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| JAK1 | JAK2 | JAK3 | TYK2 |

| 2.1 | 12 | 923 | 12 |

| Cell-Based Assays | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-2 (hPrim-T,Prolif.) JAK1/JAK3 | IFNα (hPrim-T,STAT1) JAK1/TYK2 | UKE-1 (Prolif) JAK2 | IL-12 (hPrim-T,STAT4) JAK2/TYK2 | IFNγ (U937,ICAM1) JAK1/JAK2 | IL-2 (hu-WB,STAT5) JAK1/JAK3 |

| 20 | 8 | 915 | 1189 | 417 | 451 |

In additional cellular assays19 (Table 4), compound 33 showed an IC50 of 20 nM for the inhibition of IL-2 dependent T-cell proliferation (JAK1/3 dependent signaling pathway) and an IC50 of 8 nM for the inhibition of IFNα induced STAT1 phosphorylation (JAK1/TYK2 dependent signaling pathway), validating on-target JAK1 inhibition. As for cell-based assays involving JAK2 mediated signaling pathways, lower potency was observed not only in inhibition of EPO induced CHEP cell survival (IC50 of 490 nM, Table 3) but also in the UKE-1 proliferation assay20 (JAK2 dependent signaling pathway) with IC50 of 915 nM and in the inhibition of IFNγ induced ICAM-1 expression (JAK1/2 dependent signaling pathway) in U937 cells with IC50 of 417 nM. In terms of fold-selectivity over JAK2, although the numbers change depending on types of cellular assays, the trend remained the same, consistent with biochemical assay results, confirming 33 as a JAK1 inhibitor with selectivity over JAK2. Compound 33 also showed IC50 of 0.45 μM for the inhibition of IL-2 induced STAT5 phosphorylation in a human whole blood assay (Table 4).

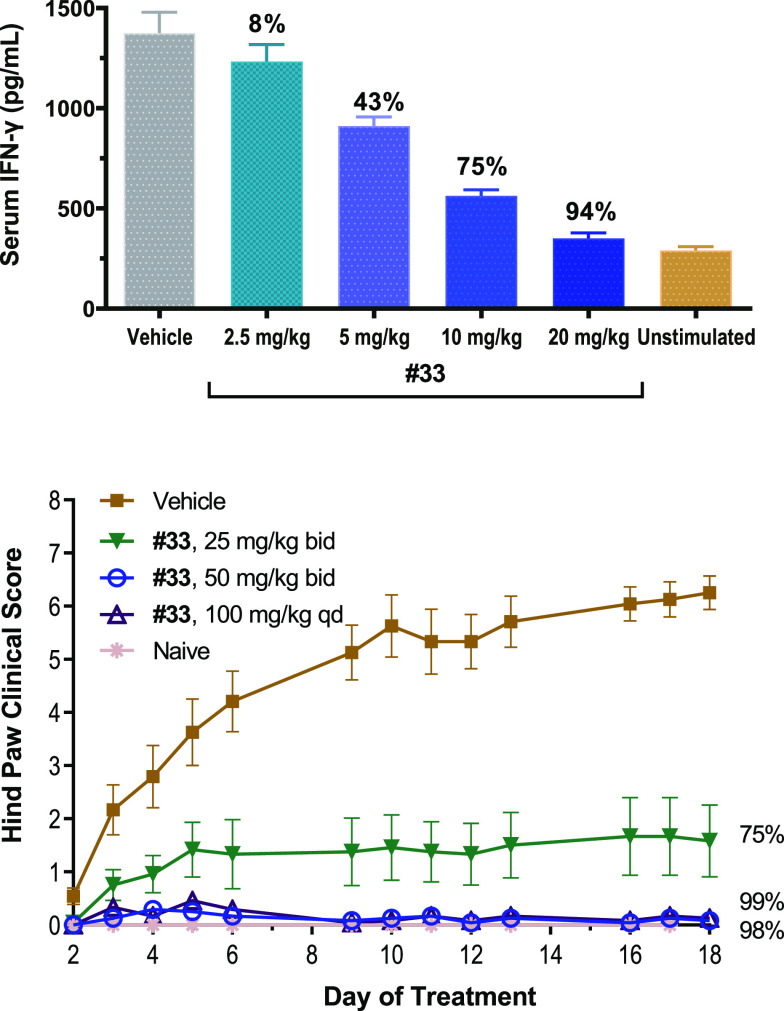

Further profiling of compound 33 in the IL-2 induced IFNγ production mouse model showed 94% inhibition at 20 mg/kg, 75% inhibition at 10 mg/kg, 43% inhibition at 5 mg/kg, and 8% inhibition at 2.5 mg/kg, in a very well-behaved dose response manner (Figure 3). Compound 33 also has improved oral bioavailability (28%F with 0.25% CMC as vehicle, 5 mg/kg) than compound 32 (12%F with the same vehicle, 5 mg/kg) and compound 30 (5%F with the same vehicle, 5 mg/kg) in SD rats, and its benzenesulfonic acid salt (besylate) has 37% oral bioavailability (0.25% HPMC as vehicle, 5 mg/kg, with clearance of 47 (mL/min)/kg, and AUC of 507 (ng·h)/mL). The besylate salt of 33 was further evaluated in the collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) rat model, which is a commonly used autoimmune model for rheumatoid arthritis (Figure 3); it almost completely blocked disease progression based on hind paw clinical scores at 100 mg/kg (QD) and at 50 mg/kg (BID) and decreased disease severity by 75% at 25 mg/kg (BID). In additional animal model studies, for example, the organ transplant rodent model (32 as R545 and 33 as R507 in the articles)21 and obliterative airway disease rat model22 (33 as R507 in the article), both 32 and 33 showed great efficacy.

Figure 3.

Compound 33 in IL-2 mouse model and rat CIA studies.

All compounds, including HTS molecules, were synthesized by following general synthetic routes outlined in Scheme 1. First step is an SNAr reaction between a bicyclic-amino moiety (S-1) and the 2,4-dichloro-pyrimidine synthon (S-2) (step a, Scheme 1) under thermal conditions and in the presence of NaHCO3 to reduce or eliminate the formation of the 2-amino-pyrimidine regioisomer. Intermediate S-3 can then undergo another thermal SNAr reaction facilitated by acid or a palladium-catalyzed coupling reaction with desired aromatic-amines (step b, Scheme 2) to provide final compounds 1–33.

Scheme 1. General Synthetic Scheme.

Scheme 2. Synthon Synthesis for Compounds 30 and 33.

For compound 30, a new reaction sequence was developed for its aniline synthon (30-S-4) synthesis (Scheme 2). The key step is a two-step/one-pot sequence for generating a benzyne intermediate with solid sodium amide in THF and in situ trapping with benzylamine (step b for 30-S-3), without using liquid ammonium and sodium metal as described in an earlier publication.23 Aniline 30-S-4 can then be generated by debenzylation of intermediate 30-S-3. For novel amine synthon 33-S-5 in compound 33, a scalable synthetic route was developed (Scheme 2). It started with dibromination of phenol 33-S-1,24,25 followed by methylation of 33-S-2; a nitro group can then be effectively introduced to intermediate 33-S-3 at the meta-position to the strong electron-donating methoxy group. Final global hydrogenation and debromination of 33-S-4 in the presence of sodium carbonate provided key aniline synthon 33-S-5 (Scheme 2). The aniline intermediate synthesis for compound 32 can be accomplished in a similar manner.

In summary, through rational design and optimization of HTS hit molecules, a series of 5-aminobenzo[d]oxazol-2(3H)-one substituted pyrimidine compounds have been identified as potent JAK1 inhibitors, with selectivity over JAK2 in biochemical assays and more significantly in various cell-based assays. After multiple rounds of lead optimization, with the focus on improving physicochemical properties, reducing CYP3A4 activities, and improving PK properties, compound 33 (R507) was identified as a clinical candidate with good JAK1 on-target potency, respectable selectivity over JAK2, adequate PK properties, and great efficacy in various preclinical animal studies, including an IL-2 induced IFNγ inhibition mouse model and a rat arthritis disease model, in a dose dependent manner. Compound 33 (R507) was selected as a clinical candidate and a prodrug (R548) was prepared for better solubility and exposure. In collaboration with Aclaris Therapeutics, Inc., a phase II clinical trial (NCT03594227) was completed with prodrug R548 (ATI-501) for the treatment of alopecia. The oral administration of prodrug R548 (ATI-501) was generally well-tolerated at all doses, did not show serious adverse events, and had statistically significant improvements compared to placebo for the primary endpoint in all three dose groups (400 mg, 600 mg, and 800 mg); the prodrug and the clinical results will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

We thank Earnest Tai, Stacey Siu, Roy Frances, Sothy Yi, and Meagan Chan for running biological assays; Mark Irving, Duayne Tokushige, and Van Nguyen Ybarra for purifying some of the final compounds; and Sarkiz Issakani, Caroline Sula, and Christina Coquilla for HTS screening.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- JAK

Janus kinase

- JAK1

Janus kinase 1

- JAK2

Janus kinase 2

- JAK3

Janus kinase 3

- TYK2

tyrosine kinase 2

- HTS

high-throughput screening

- IL-2

interleukin 2

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- IFNγ

interferon gamma

- EPO

erythropoietin

- CHEP

cultured human erythroid precursor cells

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- TPSA

topological polar surface area

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- CMC

carboxymethylcellulose

- HPMC

hydroxypropyl methylcellulose

- CIA

collagen-induced arthritis

- QD

once a day

- BID

twice a day

- po

by mouth

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00411.

Representative experimental procedures, 1H NMR and MS data for all compounds, 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra, additional in vitro and in vivo data for compounds 32 and 33, biological assay methods, and protocols for animal model studies (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Tanaka Y.; Luo Y.; O’Shea J. J.; Nakayamada S. Janus Kinase-Targeting Therapies in Rheumatology: A Mechanisms-Based Approach. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2022, 18, 133–145. 10.1038/s41584-021-00726-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli F. R.; Meylan F.; O’Shea J. J.; Gadina M. JAK Inhibitors: Ten Years After. Eur. J. Immunol. 2021, 51 (7), 1615–1627. 10.1002/eji.202048922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng H. T.; Chyuan I. T.; Lai J. H. Targeting the JAK-STAT Pathway in Autoimmune Diseases and Cancers: A Focus on Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 193, 114760. 10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J. D.; Flanagan M. E.; Telliez J. B. Discovery and Development of Janus Kinase (JAK) Inhibitors for Inflammatory Diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57 (12), 5023–5038. 10.1021/jm401490p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan M. C.; Rajapaksa N. S. Kinase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Immunological Disorders: Recent Advances. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61 (20), 9030–9058. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P.; Shen P.; Yu B.; Xu X.; Ge R.; Cheng X.; Chen Q.; Bian J.; Li Z.; Wang J. B. Janus Kinases (JAKs): The Efficient Therapeutic Targets for Autoimmune Diseases and Myeloproliferative Disorders. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 192, 112155. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan M. E.; Blumenkopf T. A.; Brissette W. H.; Brown M. F.; Casavant J. M.; Shang-Poa C.; Doty J. L.; Elliott E. A.; Fisher M. B.; Hines M.; Kent C.; Kudlacz E. M.; Lillie B. M.; Magnuson K. S.; McCurdy S. P.; Munchhof M. J.; Perry B. D.; Sawyer P. S.; Strelevitz T. J.; Subramanyam C.; Sun J.; Whipple D. A.; Changelian P. S. Discovery of CP-690,550: A Potent and Selective Janus Kinase (JAK) Inhibitor for the Treatment of Autoimmune Diseases and Organ Transplant Rejection. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53 (24), 8468–8484. 10.1021/jm1004286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J. K.; Ghoreschi K.; Deflorian F.; Chen Z.; Perreira M.; Pesu M.; Smith J.; Nguyen D. T.; Liu E. H.; Leister W.; Costanzi S.; O’Shea J. J.; Thomas C. J. Examining the Chirality, Conformation and Selective Kinase Inhibition of 3-((3R,4R)-4-Methyl-3-(Methyl(7H-Pyrrolo[2,3-d]Pyrimidin-4-Yl)Amino) Piperidin-1-Yl)-3-Oxopropanenitrile (CP-690,550). J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51 (24), 8012–8018. 10.1021/jm801142b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorarensen A.; Banker M. E.; Fensome A.; Telliez J. B.; Juba B.; Vincent F.; Czerwinski R. M.; Casimiro-Garcia A. ATP-Mediated Kinome Selectivity: The Missing Link in Understanding the Contribution of Individual JAK Kinase Isoforms to Cellular Signaling. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9 (7), 1552–1558. 10.1021/cb5002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortezavi M.; Martin D. A.; Schulze-Koops H. After 25 Years of Drug Development, Do We Know JAK?. RMD Open 2022, 8 (2), e002409 10.1136/rmdopen-2022-002409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spergel S. H.; Mertzman M. E.; Kempson J.; Guo J.; Stachura S.; Haque L.; Lippy J. S.; Zhang R. F.; Galella M.; Pitt S.; Shen G.; Fura A.; Gillooly K.; McIntyre K. W.; Tang V.; Tokarski J.; Sack J. S.; Khan J.; Carter P. H.; Barrish J. C.; Nadler S. G.; Salter-Cid L. M.; Schieven G. L.; Wrobleski S. T.; Pitts W. J. Discovery of a JAK1/3 Inhibitor and Use of a Prodrug to Demonstrate Efficacy in a Model of Rheumatoid Arthritis. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10 (3), 306–311. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour K. C.; Pine R.; Reich N. C. Interleukin 2 Activates STAT5 Transcription Factor (Mammary Gland Factor) and Specific Gene Expression in T Lymphocytes (Prolactin/Tyrosine Phosphorylation). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995, 92, 10772–10776. 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitar M.; Boldt A.; Freitag M. T.; Gruhn B.; Köhl U.; Sack U. Evaluating STAT5 Phosphorylation as a Mean to Assess T Cell Proliferation. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 722. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy J. A.; Barabé F.; Patterson B. J.; Bayani J.; Squire J. A.; Barber D. L.; Dick J. E. Expression of TEL-JAK2 in Primary Human Hematopoietic Cells Drives Erythropoietin-Independent Erythropoiesis and Induces Myelofibrosis in Vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103 (45), 16930–16935. 10.1073/pnas.0604902103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J.; Yuan B.; Hu W.; Lodish H. JAK2 V617F Stimulates Proliferation of Erythropoietin- Dependent Progenitors and Delays Their Differentiation by Activating Stat1 and other Non-Erythroid Signaling Pathways. Exp. Hematol. 2016, 44 (11), 1044. 10.1016/j.exphem.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara T.; Hooks J. J.; Dougherty S. F.; Oppenheim J. J. Interleukin 2-Mediated Immune Interferon (IFN-Gamma) Production by Human T Cells and T Cell Subsets. J. Immunol. 1983, 130 (4), 1784–1789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton S.; Kuhn K. A.; Finkelman F. D.; Hirsch R. NK Cells Secrete High Levels of IFN-γ in Response to in Vivo Administration of IL-2. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001, 31 (11), 3355–3360. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S. H.; Cantrell D. A. Signaling and Function of Interleukin-2 in T Lymphocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 36, 411. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes I. B.; Szekanecz Z.; McGonagle D.; Maksymowych W. P.; Pfeil A.; Lippe R.; Song I. H.; Lertratanakul A.; Sornasse T.; Biljan A.; Deodhar A. A Review of JAK–STAT Signalling in the Pathogenesis of Spondyloarthritis and the Role of JAK Inhibition. Rheumatology 2022, 61 (5), 1783–1794. 10.1093/rheumatology/keab740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buors C.; Douet-Guilbert N.; Morel F.; Lecucq L.; Cassinat B.; Ugo V. Clonal Evolution in UKE-1 Cell Line Leading to an Increase in JAK2 Copy Number. Blood Cancer J. 2012, 2 (4), e66 10.1038/bcj.2012.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuse T.; Hua X.; Taylor V.; Stubbendorff M.; Baluom M.; Chen Y.; Park G.; Velden J.; Streichert T.; Reichenspurner H.; Robbins R. C.; Schrepfer S. Significant Reduction of Acute Cardiac Allograft Rejection by Selective Janus Kinase-1/3 Inhibition Using R507 and R545. Transplantation 2012, 94 (7), 695–702. 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182660496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuse T.; Hua X.; Stubbendorff M.; Spin J. M.; Neofytou E.; Taylor V.; Chen Y.; Park G.; Fink J. B.; Renne T.; Kiefmann M.; Kiefmann R.; Reichenspurner H.; Robbins R. C.; Schrepfer S. The Selective JAK1/3-Inhibitor R507 Mitigates Obliterative Airway Disease Both with Systemic Administration and Aerosol Inhalation. Transplantation 2016, 100, 1022–1031. 10.1097/TP.0000000000001110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott E. L.; Bushell S. M.; Cavero M.; Tolan B.; Kelly T. R. Total Synthesis of Nigellicine and Nigeglanine Hydrobromide. Org. Lett. 2005, 7 (12), 2449–2451. 10.1021/ol050769m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajigaeshi S.; Kakinami T.; Tokiyama H.; Hirakawa T.; Okamoto T. Bromination of Phenols by Use of Benzyltrimethylammonium Tribromide. Chem. Lett. 1987, 16, 627–630. 10.1246/cl.1987.627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boers R. B.; Randulfe Y. P.; Haas H. N. S. v. d.; Rossum-Baan M. v.; Lugtenburg J. Synthesis and Spectroscopic Characterization of 1-13C- and 4-13C-Plastoquinone-9. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 2002 (13), 2094–2108. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.