Abstract

The voltage-gated sodium channel isoform NaV1.7 has drawn widespread interest as a target for non-opioid, investigational new drugs to treat pain. Selectivity over homologous, off-target sodium channel isoforms, which are expressed in peripheral motor neurons, the central nervous system, skeletal muscle and the heart, poses a significant challenge to the development of small molecule inhibitors of NaV1.7. Most inhibitors of NaV1.7 disclosed to date belong to a class of aryl and acyl sulfonamides that preferentially bind to an inactivated conformation of the channel. By taking advantage of a sequence variation unique to primate NaV1.7 in the extracellular pore of the channel, a series of bis-guanidinium analogues of the natural product, saxitoxin, has been identified that are potent against the resting conformation of the channel. A compound of interest, 25, exhibits >600-fold selectivity over off-target sodium channel isoforms and is efficacious in a preclinical model of acute pain.

Keywords: Nav1.7, sodium channel, pain, non-opioid, saxitoxin

The voltage-gated Na+ ion channel isoform NaV1.7 is a promising target for non-opioid analgesic drug development based on the finding that humans with genetic NaV1.7 loss-of-function exhibit profound insensitivity to pain.1,2 Biophysical experiments have demonstrated that NaV1.7 plays an obligatory role in modulating the excitability of nociceptors by serving as a threshold channel, integrating subthreshold depolarizations and contributing to action potential electrogenesis.3,4 In the pursuit of NaV1.7-selective therapeutics, multiple chemotypes have been investigated, including toxin-derived peptides, antibodies, and small molecules.5,6 A major challenge of this research has been achieving high selectivity over off-target Na+ ion channel isoforms (NaV1.1–1.6, NaV1.8, NaV1.9) to avoid safety liabilities.

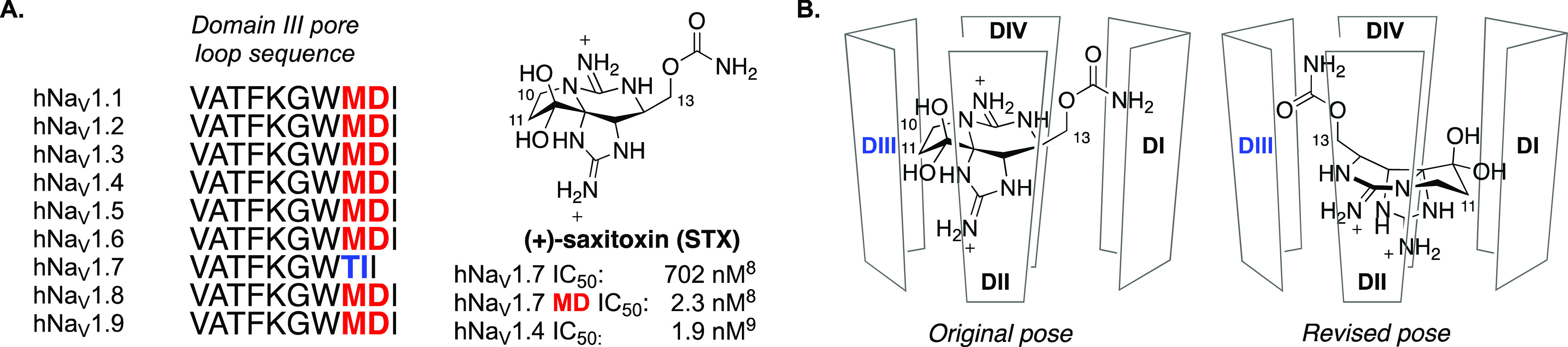

Saxitoxin (STX), tetrodotoxin (TTX), and the gonyautoxins are members of a family of naturally occurring secondary metabolites that bind to the extracellular vestibule of the sodium channel and block Na+ ion conductance.7 Studies to understand the binding pose and molecular interactions of these compounds identified a two amino acid sequence motif in the domain III pore loop of human NaV1.7 that markedly affects ligand potency (Figure 1A).8,9 Accordingly, we posited that derivatives of STX could be advanced that preferentially interact with the threonine/isoleucine sequence variant in hNaV1.7 and that were destabilized from binding the methionine/aspartic acid variant present in all other hNaV isoforms.

Figure 1.

(A) Amino acid sequence of human NaV isoforms comprising the domain III pore loop affects potency of (+)-saxitoxin. (B) Schematic representations of the original proposed pose10 and revised pose15 for binding of STX in the extracellular pore of NaV isoforms.

At the outset of our effort, information from mutagenesis and computational modeling studies suggested that STX binds to the extracellular vestibule of the sodium channel in a pose that orients the C10 and C11 substituents toward the domain III pore loop (Figure 1B, Original pose).10,11 Decarbamoylsaxitoxin (dcSTX, 4), which lacks a substituent at C11 and bears a hydroxyl group at C13, served as a starting point for structure–activity relationship studies. A series of derivatives bearing C11 ester and amide groups was prepared with the goal of improving potency against hNaV1.7 and simultaneously reducing affinity for off-target sodium channel isoforms (Table 1).

Table 1. Potency of C11 Analogues of Decarbamoylsaxitoxin.

IC50 values determined by manual patch clamp electrophysiology; data represent the mean of at least two replicates.

Data obtained from a single experiment.

Preparation of C11-substituted derivatives of dcSTX (4) was accomplished from tricyclic intermediate 1, which has been previously identified as a versatile precursor for the synthesis of naturally occurring guanidinium toxins (Scheme 1).12,13 Dihydroxylation of 1 followed by coupling of diol 2 to activated carboxylic acids gave rise to C11 esters. Acylation was regioselective for the C11-OH, as previously reported, likely due to the crowded steric environment of the C12-OH on the concave face of the fused [4.3] ring system.12 C11 amide substituents were introduced by base-free aminohydroxylation of 1 with 4-chlorobenzoyl tert-butyl carbamate and catalytic OsO4, Boc deprotection, and amide coupling.14 The intermolecular aminohydroxylation reaction is regio- and diastereoselective, affording 3 as the major product; a minor regioisomeric product was also obtained (∼4:1 rs). Oxidation of the C12-OH to the hydrated ketone with Dess–Martin periodinane and removal of protecting groups completed preparation of C11 ester- and amide-substituted derivatives of dcSTX (Table 1).

Scheme 1. Preparation of C11-Substituted Analogues of Decarbamoylsaxitoxin.

Reagents and conditions: (a) OsO4, N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide (NMO), THF, rt, 88%; (b) 2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl-benzoate derivative, DMAP, CH2Cl2, rt; (c) Dess–Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2, rt; (d) PdCl2, H2 (1 atm), H2O/MeOH/CF3CO2H, then 1 N HCl, rt; (e) OsO4, tert-butyl-4-chlorobenzoyloxycarbamate, CH3CN/H2O, 30 °C, 42%; (f) CF3CO2H, CH2Cl2; (g) aryl or alkyl carboxylic acid, HBTU, Et3N, DMF, 0 °C to rt; (h) Dess–Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2, rt; (i) PdCl2, H2 (1 atm), H2O/MeOH/CF3CO2H, then 1 N HCl, rt. Tces = S(O)2OCH2CCl3.

Analogues bearing ester substituents such as 5 and 6 exhibited potency similar to that of dcSTX (4) against hNaV1.7 (Table 1). Selectivity over hNaV1.4 was assessed due to the potential safety liability of inhibiting the predominant isoform in skeletal muscle as well as the sensitivity of this isoform to STX (Figure 1A). NaV isoform selectivity was comparable for all three compounds, and metabolic stability was poor (e.g., HLM Clint > 500 μL/min/mg). Replacement of the labile C11 ester with certain amide groups, in particular aryl amides, substantially improved hNaV1.7 potency by up to ∼50 fold (7–12). Whereas cycloalkyl amides such as 8 showed hNaV1.7 potency similar to that of dcSTX, the 2-trifluoromethyl and 2,5-bis-trifluoromethyl benzamides 7 and 10 gave IC50 values of <10 nM against the channel. Interestingly, the 2,4-bis-trifluoromethyl benzamide 9 demonstrated reduced NaV1.7 potency, suggesting that para- substitution is not well-tolerated within the binding pocket. The finding that ortho- and meta-substitution of the benzamide moiety improved hNaV1.7 potency motivated the synthesis of bicyclic amides such as indane 11 and dihydrobenzofuran 12. These compounds demonstrated 2- and 17-fold selectivity, respectively, over hNaV1.4. These results indicate that introduction of an aryl amide at the C11 position of dcSTX can substantially improve hNaV1.7 potency and moderately increase selectivity over off-target isoforms such as hNaV1.4.

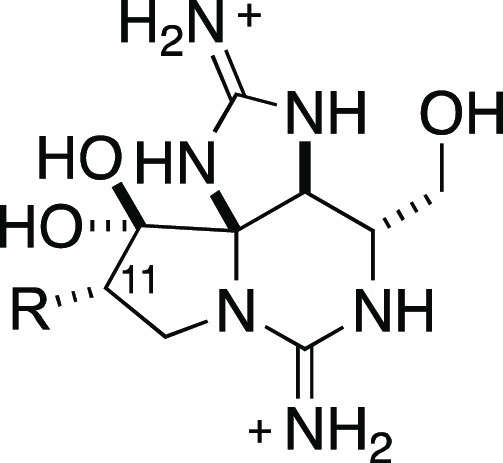

The limited improvement in selectivity for hNaV1.7 over hNaV1.4 that was achieved through modification at C11 of dcSTX suggested that functional groups installed at this position might not be oriented toward the domain III pore loop, as assumed at the outset (see Figure 1). A number of lines of evidence converged at this time to indicate that STX, dcSTX, and related guanidinium toxins bind hNaV1.7 in an orientation that positions C13, rather than C11, in proximity to the domain III pore loop (Figure 1B, Revised pose). Our observations included (1) the reduced potency of STX relative to dcSTX against hNaV1.7, (2) the increased potency of a C13 acetate derivative toward hNaV1.7, and (3) results from mutant cycle analysis indicating that the T1398/I1399 sequence motif in domain III substantially influences the potency of C13-modified ligands.15 The proximity of the C13 substituent to the T1398/I1399 motif was subsequently confirmed by a cryo-EM structure of STX bound to hNaV1.7.16 Inspired by these findings, a series of analogues of STX bearing both C11 and C13 substituents was prepared (Table 2).

Table 2. Potency of Analogues Modified at the C11 and C13 Positions against hNaV1.7 and Off-Target hNaV Isoforms.

IC50 values determined by manual patch clamp electrophysiology; data represent the mean of at least two assay determinations.

Data obtained from a single assay.

NT = not tested.

IC50 value reported in ref (15).

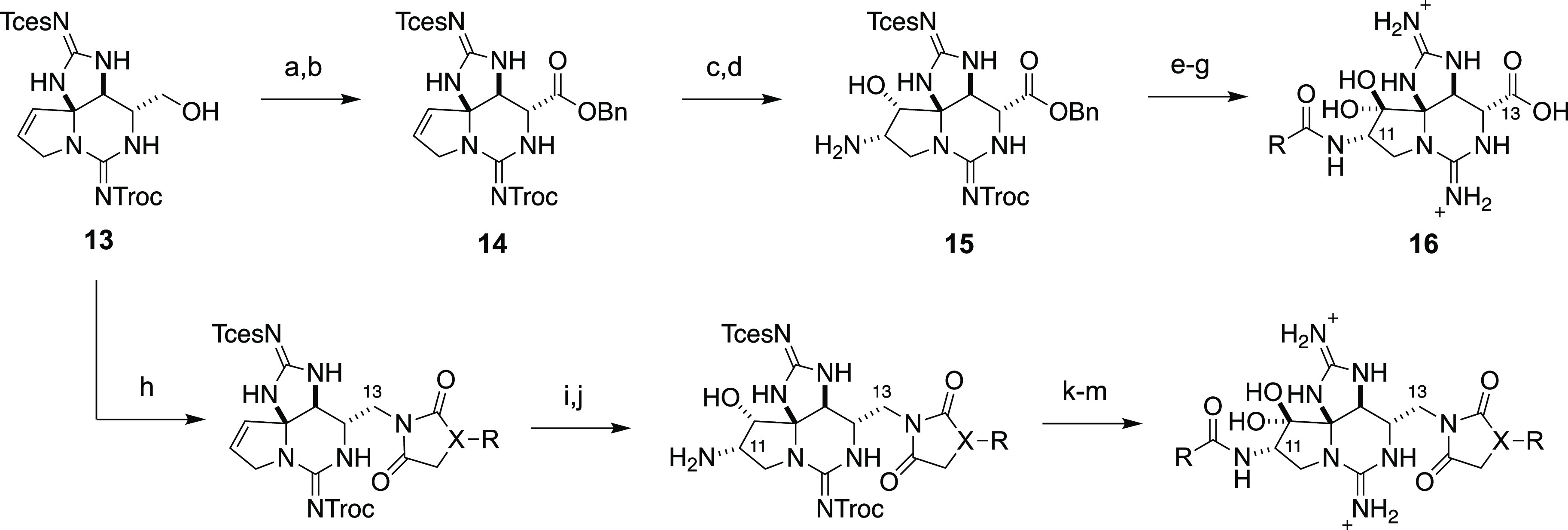

Compounds bearing a C13 carboxylic acid such as 17 and 19 were initially targeted based on the hypothesis that introduction of an anionic carboxylate would destabilize binding to off-target hNaV isoforms having the methionine/aspartate sequence motif in domain III (Figure 1 and Table 2). Preparation of the carboxylic acid was accomplished by desilylation of 1 and oxidation of the C13-OH with CrO3 and H2SO4. Following esterification of the resultant carboxylic acid, C11 ester and amide groups were attached (Scheme 2). Compounds possessing a C13 carboxylate such as 17 and 19 exhibited significantly reduced potency against hNaV1.4 (IC50 > 100 μM) while maintaining low μM activity against hNaV1.7.

Scheme 2. Preparation of C11,C13-Substituted NaV1.7-Selective Analogues of Saxitoxin.

Reagents and conditions: (a) CrO3, H2SO4, acetone, 0 °C, 75%; (b) benzyl alcohol, HBTU, iPr2NEt, DMF, 0 °C to rt, 38%; (c) OsO4, tert-butyl-4-chlorobenzoyloxycarbamate, CH3CN/H2O, 30 °C, 19%; (d) CF3CO2H, CH2Cl2, rt; (e) aryl or alkyl carboxylic acid, HBTU, Et3N, DMF, rt; (f) Dess–Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2, rt; (g) PdCl2, H2 (1 atm), H2O/MeOH/CF3CO2H, overnight, then 1 N HCl, rt; (h) Ph3P, DIAD, Et3N, succinimide or hydantoin, THF, 0 °C to rt; (i) OsO4, tert-butyl-4-chlorobenzoyloxycarbamate, CH3CN/H2O, 30 °C; (j) CF3CO2H, CH2Cl2, rt; (k) aryl or alkyl carboxylic acid, iPr2NEt, DMF, HBTU, 0 °C to rt; (l) Dess–Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2, rt; (m) PdCl2, H2 (1 atm), H2O/MeOH/CF3CO2H, overnight, then 1 N HCl, rt.

In principle, pairing of an optimal C11 amide (e.g., benzofuran as in 12) with a C13 acetate ester would result in a potent and selective hNaV1.7 inhibitor; however, the ester is likely to be metabolically labile and give rise to the less selective C13-OH metabolite. Consequently, further exploration of substituent groups at C13 focused on acetate isosteres that were predicted to have improved metabolic stability. Succinimide and hydantoin heterocycles were appended at C13, and the resultant intermediates were elaborated to install C11 amide groups along with the requisite C12 hydrated ketone (Scheme 2). Analogues possessing appropriately substituted aryl amides at C11 and succinimide or hydantoin moieties at C13 are potent inhibitors of hNaV1.7, displaying excellent selectivity over other off-target NaV isoforms expressed in the peripheral nervous system and in cardiac tissue (hNaV1.4–1.6, Table 2). Within the trifluoromethyl benzamide series (21–23), C11 substitution was systematically re-examined, with results indicating that meta- > ortho- ≫ para-CF3 with regard to hNaV1.7 potency and selectivity over hNaV1.4. Exploration of bicyclic aryl amides (24–28) led to the discovery of indane (24), tetrahydronaphthalene (25), and chromane (26) derivatives with good hNav1.7 potency (IC50 < 100 nM) and excellent selectivity over hNaV1.4–1.6.

Compound 25 was selected for further characterization on the basis of potency and NaV isoform selectivity. Profiling against hNaV1.1–1.3, hNaV1.8, CaV1.2, and hERG demonstrated >800× selectivity over these anti-targets (Table 3).17 Low clearance of 25 was observed in human and rat liver microsome, human S9, and hepatocyte incubations (Figure 2). In pharmacokinetic studies in rats and cynomolgus monkeys, 25 exhibited a low volume of distribution and low clearance with 26% of the administered dose recovered unchanged in cyno urine, indicating significant renal clearance. Consistent with the polar structure of 25, oral availability was 2% suggesting that parenteral routes are more suitable for dosing. Compound 25 was evaluated in a pain behavior experiment in cynomolgus monkeys due to its reduced potency against rat and mouse NaV1.7 (IC50 = 4.95 and 3.78 μM, respectively). At a dose of 1.25 mg/kg IV, which results in a free drug concentration 16-fold greater than the IC50 value for cynoNaV1.7 30 min after administration, both the paw withdrawal response and the heart rate response to a noxious thermal stimulus were completely blocked.17

Table 3. Potency of Compound 25 against hNaV1.1–1.8, CaV1.2, and hERG17.

| isoform | IC50 (μM)a | no. of cells |

|---|---|---|

| hNaV1.1 | >100 | 3 |

| hNaV1.2 | >100 | 3 |

| hNaV1.3 | 65.3, 62.7–68.1 | 3 |

| hNaV1.4 | 80.7, 71.1–93.3 | 14 |

| hNaV1.5 | >100 | 9 |

| hNaV1.6 | 17.9, 14.8–22.1 | 13 |

| hNaV1.7 | 0.072, 0.064–0.082 | 25 |

| hNaV1.8 | >100 | 3 |

| CaV1.2 | >100 | 2 |

| hERG | >100 | 2 |

IC50 determined by manual patch clamp reported as mean; 95% confidence interval.

Figure 2.

ADME and pharmacokinetic characteristics of compound 25. aμL/min/mg protein. bμL/min/million cells.

Potent, isoform-selective inhibitors of human NaV1.7 have been identified through a design strategy that leverages the natural product STX and an amino acid sequence variation between human NaV isoforms in the extracellular pore.8 Insights from structure–activity relationship studies of the C11 and C13 positions of STX have led to the advancement of compound 25. This ligand exhibits physicochemical properties amenable to parenteral routes of administration such as high solubility, a high unbound fraction, and low clearance. Results from pain behavior studies in non-human primates support the view that pharmacologic inhibition of NaV1.7 is sufficient to produce robust analgesia in a preclinical model of acute pain.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- dcSTX

decarbamoylsaxitoxin

- NaV1.7

voltage-gated sodium channel alpha subunit isoform 1.7

- STX

saxitoxin

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00378.

Experimental procedures and characterization of key compounds, and methods for biological assays (PDF)

Author Present Address

† Assembly Biosciences, Inc., South San Francisco, California 94080, United States

Author Present Address

‡ Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, California 94080, United States

Author Present Address

§ Sage Therapeutics, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02142, United States

Author Present Address

⊥ Pliant Therapeutics, Inc., South San Francisco, California 94080, United States

Author Present Address

∥ Septerna, Inc., South San Francisco, California 94080, United States

Research reported in the publication was supported in part by the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the U.S. National Institutes of Health under award number R44NS081887.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): H.P., S.K., G.L., J.D., J.C.H., and J.V.M. are shareholders and/or employees of SiteOne Therapeutics, Inc.

Supplementary Material

References

- Cox J. J.; Reimann F.; Nicholas A. K.; Thornton G.; Roberts E.; Springell K.; Karbani G.; Jafri H.; Mannan J.; Raashid Y.; Al-Gazali L.; Hamamy H.; Valente E. M.; Gorman S.; Williams R.; McHale D. P.; Wood J. N.; Gribble F. M.; Woods C. G. An SCN9A Channelopathy Causes Congenital Inability to Experience Pain. Nature 2006, 444 (7121), 894–898. 10.1038/nature05413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg Y. P.; MacFarlane J.; MacDonald M. L.; Thompson J.; Dube M.-P.; Mattice M.; Fraser R.; Young C.; Hossain S.; Pape T.; Payne B.; Radomski C.; Donaldson G.; Ives E.; Cox J.; Younghusband H. B.; Green R.; Duff A.; Boltshauser E.; Grinspan G. A.; Dimon J. H.; Sibley B. G.; Andria G.; Toscano E.; Kerdraon J.; Bowsher D.; Pimstone S. N.; Samuels M. E.; Sherrington R.; Hayden M. R. Loss-of-Function Mutations in the NaV1.7 Gene Underlie Congenital Indifference to Pain in Multiple Human Populations. Clin. Genet. 2007, 71 (4), 311–319. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins T. R.; Howe J. R.; Waxman S. G. Slow Closed-State Inactivation: A Novel Mechanism Underlying Ramp Currents in Cells Expressing the HNE/PN1 Sodium Channel. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18 (23), 9607–9619. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09607.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrou A. J.; Brown A. R.; Chapman M. L.; Estacion M.; Turner J.; Mis M. A.; Wilbrey A.; Payne E. C.; Gutteridge A.; Cox P. J.; Doyle R.; Printzenhoff D.; Lin Z.; Marron B. E.; West C.; Swain N. A.; Storer R. I.; Stupple P. A.; Castle N. A.; Hounshell J. A.; Rivara M.; Randall A.; Dib-Hajj S. D.; Krafte D.; Waxman S. G.; Patel M. K.; Butt R. P.; Stevens E. B. Subtype-Selective Small Molecule Inhibitors Reveal a Fundamental Role for NaV1.7 in Nociceptor Electrogenesis, Axonal Conduction and Presynaptic Release. PLoS One 2016, 11 (4), e0152405. 10.1371/journal.pone.0152405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahy J. V.; Pajouhesh H.; Beckley J. T.; Delwig A.; Du Bois J.; Hunter J. C. Challenges and Opportunities for Therapeutics Targeting the Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel Isoform NaV1.7. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62 (19), 8695–8710. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKerrall S. J.; Sutherlin D. P. NaV1.7 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Chronic Pain. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28 (19), 3141–3149. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetrodotoxin, Saxitoxin, and the Molecular Biology of the Sodium Channel. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1986, 479, 1–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J. R.; Novick P. A.; Parsons W. H.; McGregor M.; Zablocki J.; Pande V. S.; Du Bois J. Marked Difference in Saxitoxin and Tetrodotoxin Affinity for the Human Nociceptive Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel (NaV1.7). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109 (44), 18102–18107. 10.1073/pnas.1206952109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso E.; Alfonso A.; Vieytes M. R.; Botana L. M. Evaluation of Toxicity Equivalent Factors of Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning Toxins in Seven Human Sodium Channels Types by an Automated High Throughput Electrophysiology System. Arch. Toxicol. 2016, 90 (2), 479–488. 10.1007/s00204-014-1444-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov D. B.; Zhorov B. S. Modeling P-Loops Domain of Sodium Channel: Homology with Potassium Channels and Interaction with Ligands. Biophys. J. 2005, 88 (1), 184–197. 10.1529/biophysj.104.048173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkind G. M.; Fozzard H. A. A Structural Model of the Tetrodotoxin and Saxitoxin Binding Site of the Na+ Channel. Biophys. J. 1994, 66 (1), 1–13. 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80746-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahy J. V.; Walker J. R.; Merit J. E.; Whitehead A.; Du Bois J. Synthesis of the Paralytic Shellfish Poisons (+)-Gonyautoxin 2, (+)-Gonyautoxin 3, and (+)-11,11-Dihydroxysaxitoxin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (18), 5994–6001. 10.1021/jacs.6b02343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J. R.; Merit J. E.; Thomas-Tran R.; Tang D. T. Y.; Du Bois J. Divergent Synthesis of Natural Derivatives of (+)-Saxitoxin Including 11-Saxitoxinethanoic Acid. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (6), 1689–1693. 10.1002/anie.201811717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z.; Naylor B. C.; Loertscher B. M.; Hafen D. D.; Li J. M.; Castle S. L. Regioselective Base-Free Intermolecular Aminohydroxylations of Hindered and Functionalized Alkenes. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77 (2), 1208–1214. 10.1021/jo202375a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas-Tran R.; Du Bois J. Mutant Cycle Analysis with Modified Saxitoxins Reveals Specific Interactions Critical to Attaining High-Affinity Inhibition of HNaV1.7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016, 113 (21), 5856–5861. 10.1073/pnas.1603486113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H.; Liu D.; Wu K.; Lei J.; Yan N. Structures of Human Na v 1.7 Channel in Complex with Auxiliary Subunits and Animal Toxins. Science 2019, 363 (6433), 1303–1308. 10.1126/science.aaw2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajouhesh H.; Beckley J. T.; Delwig A.; Hajare H. S.; Luu G.; Monteleone D.; Zhou X.; Ligutti J.; Amagasu S.; Moyer B. D.; Yeomans D. C.; Du Bois J.; Mulcahy J. V. Discovery of a Selective, State-Independent Inhibitor of NaV1.7 by Modification of Guanidinium Toxins. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10 (1), 14791. 10.1038/s41598-020-71135-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.