Abstract

Purpose

To gauge the effects of treatment practices on prognosis for older patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer, particularly to determine whether adjuvant trastuzumab alone can offer benefit over no adjuvant therapy. This is a prospective cohort study which accompanies the RESPECT that is a randomized-controlled trial (RCT).

Methods

Patients who declined the RCT were treated based on the physician's discretion. We studied the 1) trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group, 2) trastuzumab-monotherapy group, and 3) non-trastuzumab group (no therapy or anticancer therapy without trastuzumab). The primary endpoint was disease-free survival (DFS), which was compared using the propensity-score method. Relapse-free survival (RFS) and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) were assessed.

Results

We enrolled 123 patients aged over 70 years (median: 74.5). Treatment categories were: trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group (n = 36, 30%), trastuzumab-monotherapy group (n = 52, 43%), and non-trastuzumab group (n = 32, 27%). The 3-year DFS was 96.7% in trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group, 89.2% in trastuzumab-monotherapy group, and 82.5% in non-trastuzumab group. DFS in non-trastuzumab group was lower than in trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy and trastuzumab-monotherapy groups (propensity-adjusted hazard ratio; HR: 3.29; 95% CI: 1.15–9.39; P = 0.026). The RFS in non-trastuzumab group was lower than in trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy and trastuzumab-monotherapy groups (propensity-adjusted HR = 7.80; 95% CI: 2.32–26.2, P < 0.0001). There were no significant intergroup differences in the proportions of patients showing HRQoL deterioration at 36 months (P = 0.717).

Conclusion

Trastuzumab-treated patients had better prognoses than patients not treated with trastuzumab without deterioration of HRQoL. Trastuzumab monotherapy could be considered for older patients who reject chemotherapy.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Older, HER2, Trastuzumab, Without chemotherapy

Highlights

-

•

There is less known about the efficacy of trastuzumab alone, although it avoids toxicity, especially in older patients.

-

•

It is currently unknown whether adjuvant trastuzumab therapy alone can offer a benefit over no adjuvant therapy.

-

•

Here, for the first time, we added an implication to this issue with propensity-adjustment analysis in a prospective study.

-

•

We found that trastuzumab-treated patients had better prognoses than patients not treated with trastuzumab.

-

•

Although trastuzumab plus chemotherapy remains a standard of care, trastuzumab can be considered for selected older patients.

1. Introduction

This prospective cohort study accompanied the RESPECT study [1], which is a randomized controlled trial (RCT) designed to compare the value of trastuzumab monotherapy with trastuzumab plus chemotherapy in patients over 70 years, with human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2)-positive early breast cancer. It aimed to determine the overall prognosis of older patients with HER2-positive breast cancer who did not agree to participate in the RCT despite meeting the eligibility criteria. Before starting the RCT, we questioned whether acquiring consent to participate in this RCT might be difficult in older patients, because of the possibility of emphasizing treatment in accordance with the patient's wishes, considering the potential adverse events (AEs) of chemotherapy. It is currently unknown whether adjuvant trastuzumab therapy alone can offer a benefit over no adjuvant therapy. Although we sought to directly compare trastuzumab monotherapy with no treatment in older patients, we were concerned that such a study would not be feasible or ethical because some patients might refuse to participate in an arm without trastuzumab despite having HER2-positive disease. In addition, only healthy patients could participate in the RCT. Thus, we designed a non-interventional cohort study to gauge the effects of treatment practices on prognosis for all older patients with HER2-positive breast cancer.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Patients

The trial protocol is described within the full text of this article (Supplement). We recruited patients, aged 70–80 years old, with HER2-positive invasive breast cancer who underwent curative surgery. The patient-inclusion criteria were as follows: patients with invasive breast cancer histologically diagnosed as HER2-positive breast cancer, who underwent curative surgery for stage I (pathological tumor size >0.5 cm), IIA, IIB, or IIIA disease. HER2-positivity was defined by the ASCO/CAP guidelines [2], which lay down the following criteria: immunohistochemical staining of 3+ (uniform, intense membrane staining of >30% of invasive tumor cells) and a fluorescence-in situ hybridization (FISH) result of more than six HER2 gene copies per nucleus or a FISH ratio (HER2 gene signal: chromosome 17 signal) of more than 2.2. Other key eligibility criteria were as follows: a baseline left ventricular-ejection fraction of ≥55% (measured by echocardiography) within 4 weeks of registration, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PS) score of 0 or 1, and sufficient organ function that meets the prescribed criteria in laboratory tests performed within four weeks of registration. The key exclusion criteria were as follows: the presence of active multiple primary cancer (synchronous multiple primary cancer and invasive cancer of other organs); ≥4 histological axillary lymph node metastases; no histological evaluation of axillary lymph nodes; a histologically confirmed positive margin found during breast-conservation surgery; any history of or complication following cardiac disorders; poorly-controlled hypertension; difficulty in regularly attending a medical institution due to a deterioration in the ability to perform the activities of daily living.

2.2. Trial design and oversight

Patients who were eligible for but declined participation in the RESPECT trial [1] were recruited to this cohort study. Patients who consented to participate in the RCT were randomly assigned to the trastuzumab-monotherapy group or trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group [1]. In this cohort study, treatment was chosen based on the discretion of the treating physician and the patients’ wishes without intervention, and patients were prospectively reviewed based on routine medical records. This study included three categories: 1) the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group, 2) the trastuzumab-monotherapy group, and 3) a group that received no therapy at all or received any anticancer therapy without trastuzumab (the non-trastuzumab group). The purpose of this prospective cohort study was to assess the overall effect of adjuvant therapy on HER2-positive primary breast cancer in older patients (≥70 years) and to investigate the efficacy and safety of trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy, trastuzumab-monotherapy, and non-trastuzumab treatment.

2.3. End points

The primary endpoint of the cohort study was disease-free survival (DFS), and the secondary endpoints were overall survival (OS), relapse-free survival (RFS), AEs, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL). DFS was defined by the occurrence of any of the following: a diagnosis of recurrence after breast-conservation therapy, local (ipsilateral chest wall) recurrence, regional lymph node recurrence or distant organ metastasis; a diagnosis of metachronous breast cancer or secondary cancer (not including cutaneous basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell cancer, or endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma); and all deaths (regardless of cause). RFS was defined by the occurrence of any of the following: any local recurrence (including local recurrence after breast-conservation therapy), regional lymph node recurrence or distant organ metastasis (not including metachronous breast cancer or secondary cancer), and death (regardless of cause). HRQoL was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-general (FACT-G) scale [3].

2.4. Assessment

In this cohort study, medical records were reviewed by attending physicians to detect DFS, OS, RFS, AEs, and HRQoL events without interventions, such as prospective treatment and testing. Types and grades of AEs were determined according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0. If a recurrence was observed, the date of recurrence, the type of recurrence, and the information on which the judgement was investigated. In the case of death, the date of death and the reason was investigated. The survival data and AEs were reviewed every year, beginning from the time of first enrollment to the end of the study. HRQoL of all participants in this cohort study was assessed at registration, and after 36 months.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The DFS was set as the primary endpoint. The DFS and other endpoints among trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy, trastuzumab-monotherapy, and non-trastuzumab groups were compared using propensity score-based covariate adjustments by the Cox regression model. The propensity score was estimated for each participant using a multinomial regression model, based on the age (70–75 versus 76–80 years), hormone receptor status (positive versus negative), pathologic nodal status (positive versus negative), and PS (0 or 1) in the model. Group comparisons of FACT-G total and subdomain scores were performed using an Analysis of Co-Variance (ANCOVA). This model used scores at 36 months as an outcome, and the adjusted covariates were scored at baseline in addition to the same factors in the survival analysis (i.e., age, hormone receptor status, pathologic nodal status, and PS). The estimated score difference at 36 months from trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy (as a reference) in the trastuzumab-monotherapy group and the non-trastuzumab group, 95% confidence interval (CI), and p-value were calculated. In addition, responder analysis for FACT-G was performed, with a decrease/increase of at least 5 points, which is reported as the minimally important difference (MID), from the baseline FACT-G total score defined as QoL deterioration/improvement [4]. The number and proportion of patients showing QoL deterioration/improvement are presented for each group at 36 months and compared between groups using Mantel-Haenszel test, which was stratified by the same factors in the ANCOVA.

All collected data were analyzed using SAS® version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc). A p-value of <0.05 was considered to reflect a statistically significant difference. The end points, assessments, and statistical analyses are described in detail in the protocol.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

We enrolled 123 eligible patients, aged over 70 years, with HER2-positive invasive breast cancer, from 114 institutions, between October 2009 and October 2014 in this cohort study. The CONSORT diagram is presented in Fig. 1. Three patients (2.4%) were excluded because all efficacy data was missing, leaving 120 patients for a full-set analysis; the treatment categories were as follows: 1) the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group (n = 36, 30%), 2) the trastuzumab-monotherapy group (n = 52, 43%), and 3) the non-trastuzumab group (n = 32, 27%). A total of 73% of patients received trastuzumab-containing regimens, with or without chemotherapy. The median age of the patients at entry was 74.5, the mean age was 74.6, respectively. The characteristics of the patients in the cohort study are shown in Table 1, according to the treatment options (n = 120). P values were assessed by chi squared test. Among the three subgroups, estrogen receptor (ER) and/or progesterone receptor (PgR) positivity were higher in the non-trastuzumab group (81.3% versus 48.1% in the trastuzumab group, 47.2% in the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group; P = 0.005). No differences existed among the groups in terms of the age category, stage, surgical procedure, lymph node metastasis, or co-morbidities. Irradiation of the breast after partial mastectomy was performed for all patients (n = 14/14) in the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group, whereas for only 40.0% (n = 6/15) in the trastuzumab-monotherapy group and 44.4% (n = 4/9) in the non-trastuzumab group. In the non-trastuzumab group, no patients received chemotherapy and 81.3% (n = 26/32) received endocrine therapy and thereby 18.8% (n = 6/32) simply observed.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram. Patients who met the eligibility criteria but did not agree to participate in the randomized controlled trial were included in the cohort study with written informed consent. The treatment was selected for each patient based on the discretion of the treating physician and the patient's wishes, without intervention.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics in the cohort study according to the treatment options (n = 120).

| n (%) | Trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group (n = 36) |

Trastuzumab-monotherapy group (n = 52) |

Non-trastuzumab group (n = 32) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Age | <75 | 70 (58.3) | 26 (72.2) | 27 (51.9) | 17 (53.1) | 0.13 |

| ≧75 | 50 (41.7) | 10 (27.8) | 25 (48.1) | 15 (46.9) | ||

| Stage | I | 51 (42.5) | 14 (38.9) | 20 (38.5) | 17 (53.1) | 0.43 |

| IIA | 49 (40.8) | 16 (44.4) | 22 (42.3) | 11 (34.4) | ||

| IIB | 16 (13.3) | 5 (13.9) | 9 (13.7) | 2 (6.3) | ||

| IIIA | 4 (3.3) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (6.3) | ||

| Surgery | Mastectomy | 82 (68.3) | 22 (61.1) | 37 (71.2) | 23 (71.9) | 0.99 |

| Partial mastectomy | 38 (31.7) | 14 (38.9) | 15 (28.8) | 9 (28.1) | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | Negative | 82 (68.3) | 23 (63.9) | 35 (67.3) | 24 (75.0) | 0.88 |

| Positive | 37 (30.8) | 12 (33.3) | 17 (32.7) | 8 (25.0) | ||

| N.A | 1 (0.8) | 1 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Pathology | Invasive ductal carcinoma | 112 (93.3) | 32 (88.9) | 49 (94.2) | 31 (96.9) | 0.85 |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 5 (4.2) | 1 (2.8) | 3 (5.8) | 1 (3.1) | ||

| Special type | 3 (2.5) | 3 (8.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| ER+ and/or PgR+ | Positive | 68 (56.7) | 17 (47.2) | 25 (48.1) | 26 (81.3) | 0.005 |

| Negative | 52 (43.3) | 19 (52.8) | 27 (51.9) | 6 (18.8) | ||

| Performance Status | 0 | 109 (90.8) | 34 (94.4) | 45 (86.5) | 30 (93.8) | 0.36 |

| 1 | 11 (9.2) | 2 (5.6) | 7 (13.5) | 2 (6.3) | ||

| Major Comorbidity | ||||||

| Hypertension | No | 74 (61.7) | 23 (63.9) | 30 (57.7) | 21 (65.6) | 0.73 |

| Yes | 46 (38.3) | 13 (36.1) | 22 (42.3) | 11 (34.4) | ||

| Diabetes | No | 105 (87.5) | 31 (86.1) | 48 (92.3) | 26 (81.2) | 0.32 |

| Yes | 15 (12.5) | 5 (13.9) | 4 (7.7) | 6 (18.8) | ||

| Osteoporosis | No | 108 (90.0) | 32 (88.9) | 47 (90.5) | 29 (90.6) | 0.97 |

| Yes | 12 (10.0) | 4 (11.1) | 5 (9.6) | 3 (9.4) | ||

| Hyperlipidaemia | No | 95 (79.2) | 27 (75.0) | 41 (78.8) | 27 (84.4) | 0.64 |

| Yes | 25 (20.8) | 9 (25.0) | 11 (21.2) | 5 (15.6) | ||

N.A: Non available.

3.2. DFS, RFS, and OS

The data cut-off date was October 31, 2017. The median follow-up time was 3.2 years (range: 0.9–7.0 years) in this cohort study. The details of DFS events are listed in Table 2. The DFS at 3 years was 96.7% in the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group, 89.2% in the trastuzumab-monotherapy group, and 82.5% in the non-trastuzumab group (Fig. 2). In the non-trastuzumab group, 26 of 32 patients (81.3%) were ER-positive; hormone therapy was initiated for 25 patients (96.2%). The DFS of patients in the non-trastuzumab group was lower than that of patients in the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy and trastuzumab-monotherapy groups (propensity-adjusted HR = 3.29; 95% CI: 1.15–9.39, P = 0.026). DFS of the non-trastuzumab group also showed a worse prognosis than that of the trastuzumab-monotherapy group (propensity-adjusted HR: 2.15; 95% CI: 1.20–3.93, P = 0.012). It appeared that more local recurrences were occurred in non-trastuzumab group; three patients recurred, one was ipsilateral breast recurrence without irradiation, two cases were regional lymph nodes recurrence after sentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary dissection, respectively, whereas there was neither local recurrences in the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group nor in the trastuzumab-monotherapy group. The RFS of patients in the non-trastuzumab group was lower than that of patients in the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy and trastuzumab monotherapy groups (propensity-adjusted HR = 7.80; 95% CI: 2.32–26.2, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3). In the non-trastuzumab group the OS of patients trended lower than that of patients in the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy and trastuzumab-monotherapy groups (propensity-adjusted HR = 3.44; 95% CI: 0.75–15.67, P = 0.11) (Fig.A.1).

Table 2.

The disease-free survival events in the cohort study (n = 120).

| Variable | Trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group (n = 36) | Trastuzumab-monotherapy group (n = 52) | Non-trastuzumab group (n = 32) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total events of diseasea | 0 | 4 | 7 |

| ipsilateral breast recurrence | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| regional lymph node | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Distant | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| second malignancy | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| causes of death | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| breast cancer specific | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Others | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Including all recurrences in the breast and regional lymph nodes, distant metastasis, second malignancies, and death. Duplications were observed.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of disease-free survival (DFS). The DFS at 3 years was 96.7% in the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group, 89.2% in the trastuzumab-monotherapy group, and 82.5% in the non-trastuzumab group. The DFS period of the non-trastuzumab group was lower than that of the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy and the trastuzumab monotherapy groups (propensity-adjusted HR: 3.29; 95% CI: 1.15–9.39; P = 0.026). The DFS in the non-trastuzumab group also showed a worse prognosis compared with the trastuzumab monotherapy group (propensity-adjusted HR: 2.15; 95% CI: 1.20–3.93; P = 0.012). Tick marks indicate censored data.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of relapse-free survival (RFS). The RFS of patients in the non-trastuzumab group was lower than that of patients in the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy and trastuzumab monotherapy groups (propensity-adjusted HR = 7.80; 95% CI: 2.32–26.2, P < 0.0001). Tick marks indicate censored data.

3.3. Safety

Patients who registered for the cohort group (n = 120) were included in the safety analysis. Common AEs are listed in Table A1. They are fatigue (18.3%), alopecia (18.3%), anorexia (17.5%), nail changes (15.8%) and hypertension (15.0%). All serious AEs resolved.

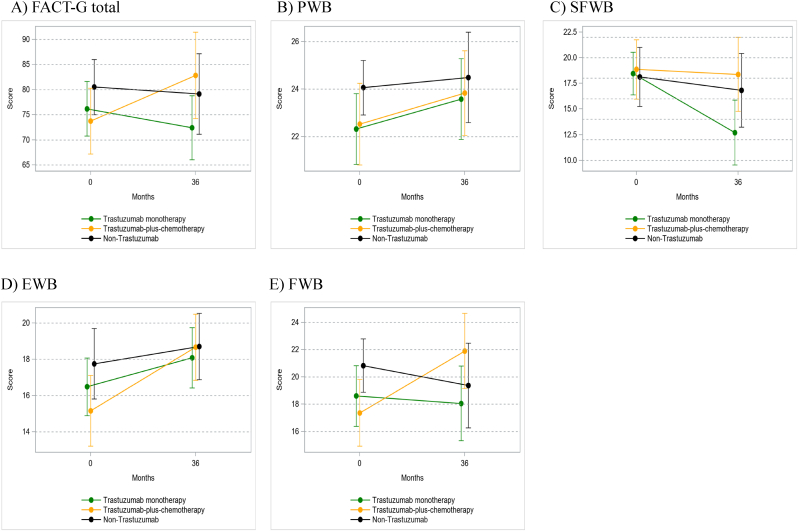

3.4. HRQoL

The completion rates for FACT-G questionnaire at registration and 36 months were 81% and 56% in the non-trastuzumab group, 78% and 50% in the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group, and 69% and 50% in trastuzumab-monotherapy group, respectively. Mean scores and 95% CI for the FACT-G total and sub-domain at each survey point are presented in Table A2 and Fig. 4. ANCOVA showed that there were no significant differences in FACT-G total score after 36 months between the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy and trastuzumab-monotherapy groups, and the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy and non-trastuzumab groups (Table A.3). The only difference between the groups was that the social and family well-being (SFWB) score at 36 months between the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group and the trastuzumab-monotherapy group (estimated value = −5.5, P = 0.036), and SFWB score of trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group at 36 months was better than that of trastuzumab-monotherapy group. Responder analysis for FACT-G showed that there were no significant intergroup differences in the proportions of patients showing QoL deterioration (P = 0.717) and improvement (P = 0.652) at 36 months (Table A.4).

Fig. 4.

Means and 95%CI of FACT-G scores at each survey point. Mean value and 95% confidential interval (95%CI) of A) Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-general (FACT-G) total, B) physical well-being (PWB), C) social and family well-being (SFWB), D) emotional well-being (EWB) and E) functional well-being (FWB) scores at baseline, and after 36 months in each group.

4. Discussion

The RESPECT study is the first randomized adjuvant trial comparing trastuzumab monotherapy with trastuzumab plus chemotherapy for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer [1]. The RESPECT study was accompanied by a cohort study for patients who refused to participate in the RCT. In the cohort study, we could evaluate the overall efficacy of adjuvant therapy for HER2-positive breast cancer patients over 70 years of age in detail, which enabled us to determine the prognoses of patients who did not receive trastuzumab prospectively, despite meeting the criteria for the RCT. We found that the DFS of the non-trastuzumab group was significantly lower than that of the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy and the trastuzumab-monotherapy groups.

Trastuzumab with chemotherapy has been approved as a standard adjuvant therapy for HER2-positive breast cancer based on previous studies that compared chemotherapy with trastuzumab plus chemotherapy [[5], [6], [7], [8]]. Thus, since 2005 no data have been generated through clinical trials regarding 1) trastuzumab without chemotherapy, and 2) no trastuzumab treatment, because all patients receive trastuzumab. In a previous study, trastuzumab-plus-pertuzumab was tested in a neoadjuvant setting as a treatment regimen without chemotherapy [9], but chemotherapy was administered after surgery, and the study lacked a no-treatment arm without anti-HER2 therapy.

Here, for the first time, we added an implication to this issue with propensity-adjustment analysis in a prospective cohort study. Recent retrospective data obtained using the National Cancer Database (NCDB) revealed no significant difference in survival by administering HER2 targeted therapy to patients who did not receive chemotherapy [10]. This NCDB is the largest series that revealed impact of anti-HER2 therapy on OS after propensity score matching, although our study collected DFS in a prospective cohort study as a primary endpoint. Especially in older patients endpoints such as DFS or RFS or breast cancer-specific survival might be important rather than OS because age and comorbidity are potential confounders [10]. Data from a large observational study suggested that trastuzumab plus chemotherapy should remain the preferred option for all patients indicated for adjuvant treatment, and that a low proportion of patients need an alternative treatment approach, either because of contraindications or the patient's preference, in those patients trastuzumab monotherapy might be a reasonable option [11], and the expert position paper from the International Society of Geriatric Oncology discussed as well [12]. But to our knowledge, no prospective data exist to suggest that prospective adjuvant trastuzumab alone can offer a benefit over no adjuvant therapy. A trial comparing no adjuvant treatment to trastuzumab alone would not be feasible or ethical. In our study, in the non-trastuzumab group, ER-positivity was 81.3%, and majority of the patients only received hormonal therapy. Subsequently, it was associated with a worse prognosis compared to the chemotherapy-plus-trastuzumab, and the trastuzumab-monotherapy groups. Even in patients with ER-positive tumors trastuzumab would be important, which was compatible to the results of RCT irrespective of hormone receptor status [6,7]. In our study there would be a caution that more local recurrences might be occurred due to undertreatment, especially in the non-trastuzumab group. For further research, a prognostic score, HER2DX, has been developing in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer to predict survival outcome and select candidate for escalated or de-escalated systemic treatment [13,14].

Older patients are at an increased risk for severe chemotherapy-induced toxicity [[15], [16], [17]]. Regarding the safety of trastuzumab in older patients, the results of a large observational study indicated that the risk of cardiac function toxicity was 5.7% [18] and that it was associated with age [18,19], although it remained manageable [18], and the risks associated with trastuzumab were outweighed by the benefits [18,20]. A phase II study of trastuzumab monotherapy in older women showed that DFS at 5-year was 86.4% (95% CI: 73.6 to 93.3) with cardiac safety [21]. In terms of the balance between benefit and harm, we recommend trastuzumab monotherapy if the patients do not receive chemotherapy, based on our current findings. The ATOP trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03587740), is an ongoing single-arm study of T-DM1 in patients over 60 years of age that seeks a more definitive insight to anti-HER2 therapy in older patients, the result of which are much anticipated.

Besides the incidence of AEs, HRQoL is also important, because chemotherapy causes significant deterioration of HRQoL in older patients [22,23]. The large clinical trial in older patients showed that one-third had a clinically meaningful decline of physical function at 12 months, although half recovered [24]. We observed a clinically significant HRQoL rate of deterioration between 2 months and 1 year into the RCT, which recovered after 3 years [1,25]. As a result of the QoL evaluation in this cohort study, chemotherapy plus trastuzumab or trastuzumab monotherapy as postoperative adjuvant therapy did not affect HRQoL at 36 months. We also observed the impact of chemotherapy on cognitive functioning in the RCT [26], the information would be important to share decision making between clinicians and patients.

This study has a few limitations. No definitive conclusions regarding trastuzumab without chemotherapy can be made because of a non-randomized small study, although 120 patients were treated and assessed prospectively with a propensity score-adjusted analysis with regard to pre-defined endpoints. There were fewer events because patients enrolled had stage I or stage IIA breast cancer, even in the non-trastuzumab arm of the cohort group, the 3-year DFS was over 80%. Although more patients were needed for a higher number of events, it was difficult to complete enrollment, because of the low number of older HER2-positive patients and disease heterogeneity [27]. We could have extended the follow-up period to detect more events, but it was assumed that non-breast cancer deaths as well as recurrences would accumulate, because eight years passed after the first patient was enrolled. However, a longer follow-up period is needed to shed light on patient prognosis. In older patients the geriatric assessment screening tools can be useful for predicting severe AEs for chemotherapy [28], and it is important to intensify supportive care and develop modified treatment regimens in vulnerable patients who may subsequently experience greater toxicity [29]. Chronological age by itself is not a stand-alone biomarker, in this study the scope of assessment included activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, depression, cognitive function, and subjective well-being [30]. After analyzing them we hope to create predictive tools for AEs or prognosis.

5. Conclusions

We found here, that patients who received any trastuzumab-containing regimen, even trastuzumab monotherapy, had a better prognosis than those who were not treated with trastuzumab, without deterioration of QoL. Although trastuzumab plus chemotherapy remains a standard of care, trastuzumab monotherapy could be considered for selected older patients, even if the patients are not willing to receive chemotherapy.

Trial registration number

The protocol was registered on the website of the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN), Japan (protocol ID: UMIN 000028476).

Funding

This study was funded by the Comprehensive Support Project for Oncology Research (CSPOR) of the Public Health Research Foundation, Japan. All decisions concerning the planning, implementation, and publication of this study were made by the executive committee of this study. The corporate and individual sponsors of this study are listed on the CSPOR website (http://www.csp.or.jp/cspor/kyousan_e.html).

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: MS, NT, YU, HB, TN, MK, TM, YY, HI and HM. Provision of study material or patients: TS, SB, KK, HK, HM, MT, NS, MT, MY, TT, KT and TT. Data and statistical analysis: YU and TK. Manuscript preparation: MS, NT, YU, and TK. Manuscript editing: MS and NT. Manuscript review: All authors.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by independent ethics committees and institutional review boards. The trial protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions. The study conformed with the Declaration of Helsinki and the “Ethical Guidelines for Clinical Research” guidelines of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Declaration of competing interest

YU reports honoraria for consulting from Chugai pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. TT reports honoraria for lectures from Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., Pfizer Japan Inc., Novartis Pharma K·K., AstraZeneca K·K., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K·K., and Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. TN reports fees for Non-CME services and honoraria for lectures from Chugai pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., AstraZeneca K·K., Novartis Pharma K·K., Eli Lilly Japan K·K., Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, and Eisai Co., Ltd. TM reports fees for non-CME services and honoraria for lectures from AstraZeneca K·K, Chugai pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K·K., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Nippon Kayaku Co., Ltd., and Pfizer Japan Inc. HI reports honoraria for lectures from Chugai pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. HM reports honoraria from AstraZeneca K·K, Pfizer Japan Inc, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd and Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd; and research grants from the Japanese government, Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd, Eisai Co., Ltd, Nippon Kayaku Co., Ltd and Pfizer Japan Inc, outside the submitted work.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Toru Watanabe and Yasuo Ohashi for valuable advice on the research plan for the RESPECT study group. We thank the patients who participated in this trial and their families and caregivers, all investigators involved in this study, and all members of the independent data-monitoring committee for their contributions to the study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2022.10.017.

Appendix A.

Fig. A.1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival (OS). The OS of patients in the non-trastuzumab group was marginally lower than that of patients in the trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy, and trastuzumab monotherapy groups (propensity-adjusted HR = 3.44; 95% CI: 0.75–15.67, P = 0.11). Tick marks indicate censored data.

Table A.1Common adverse events in the cohort group (n = 120)

| Events/Grade | Grade 1 |

Grade 2 |

Grade 3 |

Grade 4 |

Grade 3 or 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | % | ||||

| Allergic reaction | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0.8 |

| Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.8 |

| Hypertension | 14 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0.8 |

| Fatigue | 13 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 2.5 |

| Nausea | 11 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anorexia | 16 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2.5 |

| Oral cavity mucositis (clinical exam) | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alopecia | 6 | 16 | – | – | – |

| Nail changes | 16 | 3 | 0 | – | 0 |

| Fracture | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2.5 |

| Pain (muscle) | 5 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1.7 |

| Fever | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table A.2.

Mean scores and 95% CI for the FACT-G total and sub-domain at each survey point

| Trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy (n = 36) |

Trastuzumab monotherapy (n = 52) |

Non-trastuzumab (n = 32) |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responses | Mean | 95%CI | Responses | Mean | 95%CI | Responses | Mean | 95%CI | ||||||||

| Total score | Baseline | 28 | 73.8 | 67.2 | – | 80.3 | 36 | 76.2 | 70.8 | – | 81.6 | 26 | 80.5 | 75.1 | – | 86.0 |

| 36 months | 18 | 82.8 | 74.2 | – | 91.5 | 26 | 72.4 | 66.1 | – | 78.8 | 18 | 79.2 | 71.2 | – | 87.2 | |

| PWB score | Baseline | 28 | 22.5 | 20.8 | – | 24.2 | 40 | 22.3 | 20.8 | – | 23.8 | 28 | 24.1 | 22.9 | – | 25.2 |

| 36 months | 20 | 23.8 | 22.1 | – | 25.6 | 28 | 23.6 | 21.9 | – | 25.3 | 19 | 24.5 | 22.6 | – | 26.4 | |

| SFWB score | Baseline | 28 | 18.9 | 16.0 | – | 21.8 | 39 | 18.5 | 16.4 | – | 20.5 | 26 | 18.1 | 15.2 | – | 21.0 |

| 36 months | 20 | 18.4 | 14.8 | – | 22.0 | 27 | 12.7 | 9.5 | – | 15.9 | 18 | 16.8 | 13.2 | – | 20.4 | |

| EWB score | Baseline | 29 | 15.2 | 13.2 | – | 17.1 | 38 | 16.5 | 14.9 | – | 18.1 | 28 | 17.8 | 15.8 | – | 19.7 |

| 36 months | 18 | 18.7 | 16.8 | – | 20.5 | 27 | 18.1 | 16.4 | – | 19.7 | 19 | 18.7 | 16.9 | – | 20.5 | |

| FWB score | Baseline | 29 | 17.4 | 14.9 | – | 19.8 | 39 | 18.6 | 16.4 | – | 20.8 | 28 | 20.8 | 18.9 | – | 22.8 |

| 36 months | 20 | 21.9 | 19.1 | – | 24.7 | 28 | 18.1 | 15.3 | – | 20.8 | 19 | 19.4 | 16.3 | – | 22.5 | |

Table A.3.

Estimated difference of FACT-G scores at 36 months by ANCOVA

| Questionnaire | Group | Difference from trastuzumab-plus-chemotherapy group |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Standard error | P-value | ||

| FACTG | Non-trastuzumab | −3.6 | 6.0 | 0.552 |

| Trastuzumab monotherapy | −7.3 | 5.2 | 0.161 | |

| PWB | Non-trastuzumab | 0.1 | 1.6 | 0.973 |

| Trastuzumab monotherapy | 0.6 | 1.4 | 0.647 | |

| SFWB | Non-trastuzumab | −0.3 | 3.0 | 0.926 |

| Trastuzumab monotherapy | −5.5 | 2.5 | 0.036 | |

| EWB | Non-trastuzumab | −0.5 | 1.5 | 0.749 |

| Trastuzumab monotherapy | 0.0 | 1.3 | 0.987 | |

| FWB | Non-trastuzumab | −4.0 | 2.2 | 0.076 |

| Trastuzumab monotherapy | −3.5 | 1.9 | 0.069 | |

Abbreviations: ANCOVA, Analysis of Co-Variance; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-general; PWB, physical well-being; SFWB, social and family well-being; EWB, emotional well-being; FWB, functional well-being.

Table A.4.

Results of responder analysis for FACT-G total score

| FACT-G | Trasutuzumab-plus-chemotharapy |

Trastuzumab monotherapy |

Non-trastuzumab group |

P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number surveyed | Number changed | % changed | Number surveyed | Number changed | % changed | Number surveyed | Number changed | % changed | ||

| Deterioration at 36 months* | 15 | 4 | 26.7 | 22 | 8 | 36.4 | 18 | 4 | 22.2 | 0.717 |

| Improvement at 36 months* | 15 | 6 | 40.0 | 22 | 7 | 31.8 | 18 | 5 | 27.8 | 0.652 |

NOTE. *Responder analysis was performed for FACT-G, with an increase (decrease) of at least 5 points from baseline in the FACT-G total score defined as improvement (deterioration) at 36 months. P value for comparison of the percentage of patients showing improvement (deterioration) between groups by Mantel-Haenszel test, which was stratified by hormone receptor status, pathaological noda status, and performance status.

Appendix B. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Sawaki M., Taira N., Uemura Y., Saito T., Baba S., Kobayashi K., et al. Randomized controlled trial of trastuzumab with or without chemotherapy for HER2-positive early breast cancer in older patients. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3743–3752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolff A.C., Hammond M.E., Schwartz J.N., Hagerty K.L., Allred D.C., Cote R.J., et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:118–145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cella D.F., Tulsky D.S., Gray G., Sarafian B., Linn E., Bonomi A., et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eton D.T., Cella D., Yost K.J., Yount S.E., Peterman A.H., Neuberg D.S., et al. A combination of distribution- and anchor-based approaches determined minimally important differences (MIDs) for four endpoints in a breast cancer scale. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:898–910. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piccart-Gebhart M.J., Procter M., Leyland-Jones B., Goldhirsch A., Untch M., Smith I., et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1659–1672. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romond E.H., Perez E.A., Bryant J., Suman V.J., Geyer C.E., Jr., Davidson N.E., et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1673–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith I., Procter M., Gelber R.D., Guillaume S., Feyereislova A., Dowsett M., et al. 2-year follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:29–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slamon D., Eiermann W., Robert N., Pienkowski T., Martin M., Press M., et al. Adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1273–1283. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gianni L., Pienkowski T., Im Y.H., Roman L., Tseng L.M., Liu M.C., et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early HER2-positive breast cancer (NeoSphere): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:25–32. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70336-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguy S., Wu S.P., Oh C., Gerber N.K. Outcomes of HER2-positive non-metastatic breast cancer patients treated with anti-HER2 therapy without chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;187:815–830. doi: 10.1007/s10549-021-06115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dall P., Koch T., Gohler T., Selbach J., Ammon A., Eggert J., et al. Trastuzumab without chemotherapy in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer: subgroup results from a large observational study. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:51. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3857-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brain E., Caillet P., de Glas N., Biganzoli L., Cheng K., Lago L.D., et al. HER2-targeted treatment for older patients with breast cancer: an expert position paper from the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10:1003–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prat A., Guarneri V., Paré L., Griguolo G., Pascual T., Dieci M.V., et al. A multivariable prognostic score to guide systemic therapy in early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer: a retrospective study with an external evaluation. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1455–1464. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30450-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prat A., Guarneri V., Pascual T., Braso-Maristany F., Sanfeliu E., Pare L., et al. Development and validation of the new HER2DX assay for predicting pathological response and survival outcome in early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer. EBioMedicine. 2022;75 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinder M.C., Duan Z., Goodwin J.S., Hortobagyi G.N., Giordano S.H. Congestive heart failure in older women treated with adjuvant anthracycline chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3808–3815. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patt D.A., Duan Z., Fang S., Hortobagyi G.N., Giordano S.H. Acute myeloid leukemia after adjuvant breast cancer therapy in older women: understanding risk. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3871–3876. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du X.L., Xia R., Liu C.C., Cormier J.N., Xing Y., Hardy D., et al. Cardiac toxicity associated with anthracycline-containing chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:5296–5308. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dall P., Lenzen G., Gohler T., Lerchenmuller C., Feisel-Schwickardi G., Koch T., et al. Trastuzumab in the treatment of elderly patients with early breast cancer: results from an observational study in Germany. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6:462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaz-Luis I., Keating N.L., Lin N.U., Lii H., Winer E.P., Freedman R.A. Duration and toxicity of adjuvant trastuzumab in older patients with early-stage breast cancer: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:927–934. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brollo J., Curigliano G., Disalvatore D., Marrone B.F., Criscitiello C., Bagnardi V., et al. Adjuvant trastuzumab in elderly with HER-2 positive breast cancer: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Owusu C., Margevicius S.P., Klepin H.D., Vogel C.L., Alahmadi A., Vuyyala S., et al. Safety and efficacy of single-agent adjuvant trastuzumab in older women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:528. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muss H.B., Berry D.A., Cirrincione C.T., Theodoulou M., Mauer A.M., Kornblith A.B., et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2055–2065. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kornblith A.B., Lan L., Archer L., Partridge A., Kimmick G., Hudis C., et al. Quality of life of older patients with early-stage breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a companion study to cancer and leukemia group B 49907. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1022–1028. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.9859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurria A., Soto-Perez-de-Celis E., Allred J.B., Cohen H.J., Arsenyan A., Ballman K., et al. Functional decline and resilience in older women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:920–927. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taira N., Sawaki M., Uemura Y., Saito T., Baba S., Kobayashi K., et al. Health-related quality of life with trastuzumab monotherapy versus trastuzumab plus standard chemotherapy as adjuvant therapy in older patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:2452–2462. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hagiwara Y., Sawaki M., Uemura Y., Kawahara T., Shimozuma K., Ohashi Y., et al. Impact of chemotherapy on cognitive functioning in older patients with HER2-positive breast cancer: a sub-study in the RESPECT trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;188:675–683. doi: 10.1007/s10549-021-06253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leonard R., Ballinger R., Cameron D., Ellis P., Fallowfield L., Gosney M., et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in older women (ACTION) study - what did we learn from the pilot phase? Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1260–1266. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurria A., Mohile S., Gajra A., Klepin H., Muss H., Chapman A., et al. Validation of a prediction tool for chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2366–2371. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.4327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magnuson A., Sedrak M.S., Gross C.P., Tew W.P., Klepin H.D., Wildes T.M., et al. Development and validation of a risk tool for predicting severe toxicity in older adults receiving chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:608–618. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohile S.G., Dale W., Somerfield M.R., Schonberg M.A., Boyd C.M., Burhenn P.S., et al. Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: ASCO guideline for geriatric Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2326–2347. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.8687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.