Abstract

Background

Dozens of studies have demonstrated gut dysbiosis in COVID-19 patients during the acute and recovery phases. However, a consensus on the specific COVID-19 associated bacteria is missing. In this study, we performed a meta-analysis to explore whether robust and reproducible alterations in the gut microbiota of COVID-19 patients exist across different populations.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted for studies published prior to May 2022 in electronic databases. After review, we included 16 studies that comparing the gut microbiota in COVID-19 patients to those of controls. The 16S rRNA sequence data of these studies were then re-analyzed using a standardized workflow and synthesized by meta-analysis.

Results

We found that gut bacterial diversity of COVID-19 patients in both the acute and recovery phases was consistently lower than non-COVID-19 individuals. Microbial differential abundance analysis showed depletion of anti-inflammatory butyrate-producing bacteria and enrichment of taxa with pro-inflammatory properties in COVID-19 patients during the acute phase compared to non-COVID-19 individuals. Analysis of microbial communities showed that the gut microbiota of COVID-19 recovered patients were still in unhealthy ecostates.

Conclusions

Our results provided a comprehensive synthesis to better understand gut microbial perturbations associated with COVID-19 and identified underlying biomarkers for microbiome-based diagnostics and therapeutics.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12866-022-02686-9.

Keywords: COVID-19, Gut microbiota, Acute phase, Recovery phase, 16S rRNA

Introduction

The pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a global health issue caused by infection from the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which has devastated economies and overwhelmed healthcare systems all over the world [1]. Moreover, the emergence and rapid spread of various SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOCs) and variants of interest (VOIs) that is more contagious and potential to evade immunity has posed challenges to the control of the COVID-19 pandemic [2, 3]. It is essential to explore disease pathogenesis and develop new therapeutic strategies for COVID-19. Evidence accumulating in humans and animals implicated that gut dysbiosis is associated with infectious diseases caused by viral infections, such as influenza, HIV infection, and Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection [4–6]. Association between gut dysbiosis and SARS-CoV-2 infection has been receiving increasing attention [7]. Most COVID-19 patients exhibit gastrointestinal symptoms and inflammation [8, 9]. The possibility that gut dysbiosis contributes to SARS-CoV-2 infection was also raised by animal study, showing that the microbiota can affect angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) [10]. It has been extensively known that ACE2 is regarded as the crucial receptor for cell entry of SARS-CoV-2, which is widely distributed in alveolar tissue and gut [11–14]. Further, gut microbial alteration was reported to be strongly associated with persistent symptoms in COVID-19 [15]. It has been reported that known probiotic supplementation can promote symptom resolution and viral clearance in COVID-19 patients [16, 17]. These suggest pivotal roles of gut microbiota in developing diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic strategies for COVID-19.

Human studies from different populations have investigated perturbations in gut microbiota in COVID-19 patients during the acute and recovery phases through 16S rRNA gene amplified sequencing [17–39]. The common conclusion across these studies is that the gut microbiota of COVID-19 patients differs from that of healthy subjects. However, most of these studies are limited by small sample sizes, and, particularly, have yielded plentiful inconsistent results on the bacterial taxa associated with the disease. The wide variation of the gut microbiota across different populations, lifestyles, and diets together with heterogeneity in study designs, data processing and statistical methods make these reported results difficult to interpret [40]. Meta-analyses have been proposed to solve these problem for providing an effective approach to screen for consistent disease-associated microbial signatures, especially specific bacterial taxa, which may be promising biomarkers enhancing diagnostic accuracy, guiding treatment, promoting the monitoring of prognosis and improving the efficacy of vaccinations [41–43]. Here, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies that reported 16S rRNA gene sequences of fecal samples or rectal swabs from adult patients with COVID-19. We reanalyzed the 16S rRNA sequence data through a uniform analysis pipeline to identify the robust and reproducible perturbations in gut microbiota and elucidate potential microbial biomarkers in COVID-19.

Results

Study selection

The details of the searching and screening process were summarized in a flowchart (Fig. S1). After review, we identified 23 relevant articles, of which, 16 eligible articles were re-analyzed in our study (Table 1 and Table S2 showed information of studies included and excluded, separately). Ten studies were from Asia, others from America and Europe. The Illumina MiSeq was the most widely used sequencing platform (n = 11). The analysed datasets were generated mostly based on the V3–V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene (n = 14). Twelve studies made a comparison of gut microbiota between COVID-19 patients (COV) and non-COVID-19 individuals (non-COV); six made a comparison between COVID-19 recovered patients (RP/post-RP) and non-COV; four made a comparison between COV and RP/post-RP; and four studies involved gut microbiota of COVID-19 patients with different severity levels, including 161 non-severe COVID-19 patients and 108 severe COVID-19 patients. A total of 1385 individual samples were available, including 697 COV, 557 non-COV, 79 RP, and 52 post-RP. In most studies (n = 9), age and gender were not significantly different among the groups. Fourteen studies assessed the differential abundance of gut bacterial taxa or pathways between groups, of which, 11 studies were conducted without adjustment for relevant covariates, such as age, gender, antibiotics treatment, and so on.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Studies Included

| Author, Year [Ref] |

Country | Design | Study population a | Sample type | 16S region | Sequencing platform | Differential taxa analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al 2021 [18] | United Arab Emirates | Case-control | 78 COV, 50 non-COV | Fecal samples |

COV: V3-V4; non-COV: V4 |

MiSeq | DESeq2 |

| Cervino 2022 [19] | France | Case-control | 55 COV, 76 non-COV | Fecal samples | V3-V4 | MiSeq | Wilcoxon test |

| Chen 2022 [26] | China | Longitudinal | 26 COV, 20 RP, 30 post-RP, 30 non-COV | Fecal samples | V3-V4 | MiSeq | NM |

| Gaibani 2021 [27] | Italy | Case-control | 69 COV, 69 non-COV | Fecal samples |

COV: V3-V4; non-COV: V3-V4, V1-V3 |

MiSeq, 454 GS Junior |

LEfSe |

| Gu 2020 [28] | China | Case-control | 30 COV, 30 non-COV | Fecal samples | V3-V4 | MiSeq | LEfSe |

| Khan 2021 [29] | India | Case-control | 30 COV (10 asymptomatic, 10 non-severe, 10 severe), 10 non-COV | Fecal samples | V3-V4 | HiSeq 2000 | LEfSe |

| Kim 2021 [30] | Korea | Longitudinal | 12 COV, 12 RP, 36 non-COV b | Fecal samples | V3–V4 | MiSeq | MaAsLin2 |

| Mazzarelli 2021 [31] | Italy | Case-control | 15 COV, 8 non-COV | Rectal swabs | V2, V4, V8, V3-6, 7-9 | Ion Torrent S5 | DESeq2 |

| Moreira-Rosario 2021 [32] | Portugal | Cross-sectional | 111 COV (54 non-severe, 57 severe) | Fecal samples | V3-V4 | Ion Torrent S5 | NM |

| Newsome 2021 [33] | USA | Case-control | 50 COV, 9 RP, 34 non-COV | Fecal samples | V1-V3 | MiSeq | edgeR |

| Rafiqul 2022 [20] | Bangladesh | Case-control | 44 COV, 30 non-COV | Fecal samples | V3-V4 | MiSeq | Kruskal-Wallis |

| Reinold 2021 [21] | Germany | Case-control | 117 COV (79 non-severe, 38 severe), 95 non-COV | Rectal swabs | V3-V4 | NovaSeq 6000 | LEfSe |

| Ren 2021 [22] | China | Case-control | 36 COV, 18 RP, 72 non-COV | Fecal samples | V3-V4 | MiSeq | LEfSe |

| Tian 2021 [23] | China | Case-control | 7 post-RP, 7 non-COV | Fecal samples | V3-V4 | MiSeq | LEfSe |

| Wu 2021 [24] | China | Case-control | 24 COV (21 non-severe, 3 severe; 50 samples), 20 RP (31 samples), 32 non-COV (32 samples) | Fecal samples | V3-V4 | NovaSeq 6000 | LEfSe/MaAslin2 |

| Zhou 2021 [25] | China | Case-control | 15 post-RP, 14 non-COV | Fecal samples | V3-V4 | MiSeq | Wilcoxon test |

NM Not mentioned. a We focused on only study subjects that have available stool samples or rectal swabs. b Only the data of the COV group and the RP group was obtained from the corresponding author, the data of the non-COV group belong to other authors

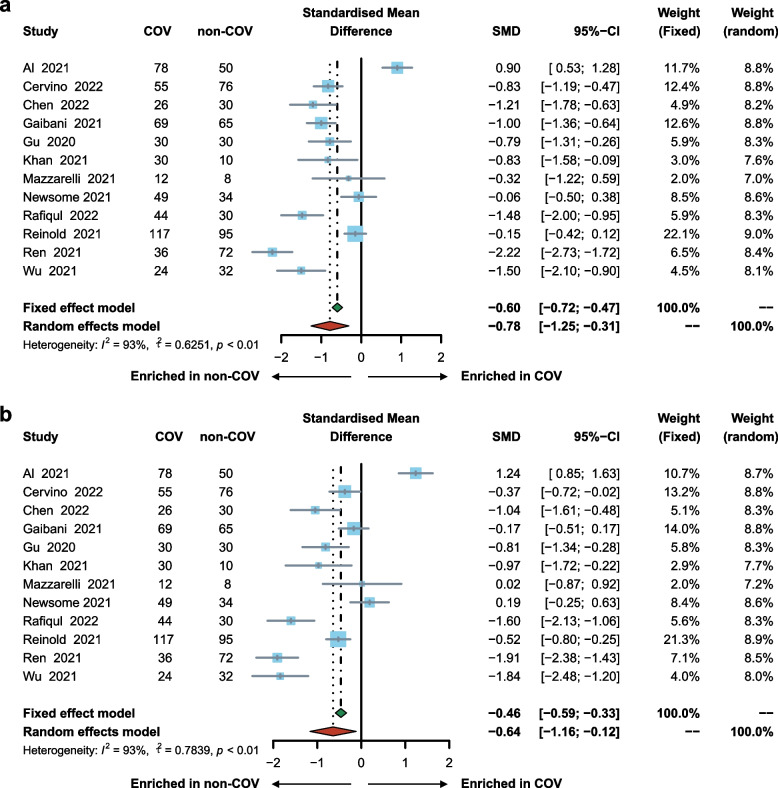

Microbial diversity was decreased in COV

The pooled estimate by random effects model showed a significant decrease in COV compared to non-COV in the measures of alpha diversity, including Shannon’s diversity index (SMD = − 0.78; 95% CI, − 1.25 to − 0.31; Fig. 1a), observed species (SMD = − 0.64; 95% CI, − 1.16 to − 0.12; Fig. 1b), Pielou’s evenness (SMD = − 0.72; 95% CI, − 1.10 to − 0.34), and Faith’s phylogenetic diversity (SMD = − 0.49; 95% CI, − 0.88 to − 0.10; Fig. S2). Sensitivity analysis showed that the results were consistent after the removal of either of the included studies (Fig. S3). The funnel plots symmetry in consonance with Begg’s and Egger’s test indicated no publication bias (Fig. S4). In the subset of four studies that involved COVID-19 patients with different severity levels (one study removed due to small sample size of severe COVID-19 patients), the pooled estimate of alpha diversity by fixed effects model revealed a non-significant decrease in severe COVID-19 patients compared with non-severe COVID-19 patients as measured by Shannon’s diversity index (SMD = − 0.24; 95% CI, − 0.49 to 0.02), observed species (SMD = − 0.21; 95% CI, − 0.47 to 0.05), Pielou’s evenness (SMD = − 0.21; 95% CI, − 0.47 to 0.04), and Faith’s phylogenetic diversity (SMD = − 0.16; 95% CI, − 0.42 to 0.10; Fig. S5).

Fig. 1.

Forest plot showing differences in alpha diversity between COV and non-COV by (a) Shannon’s diversity index, and (b) observed species. COV, samples derived from COVID-19 patients; non-COV, samples derived from non-COVID-19 individuals

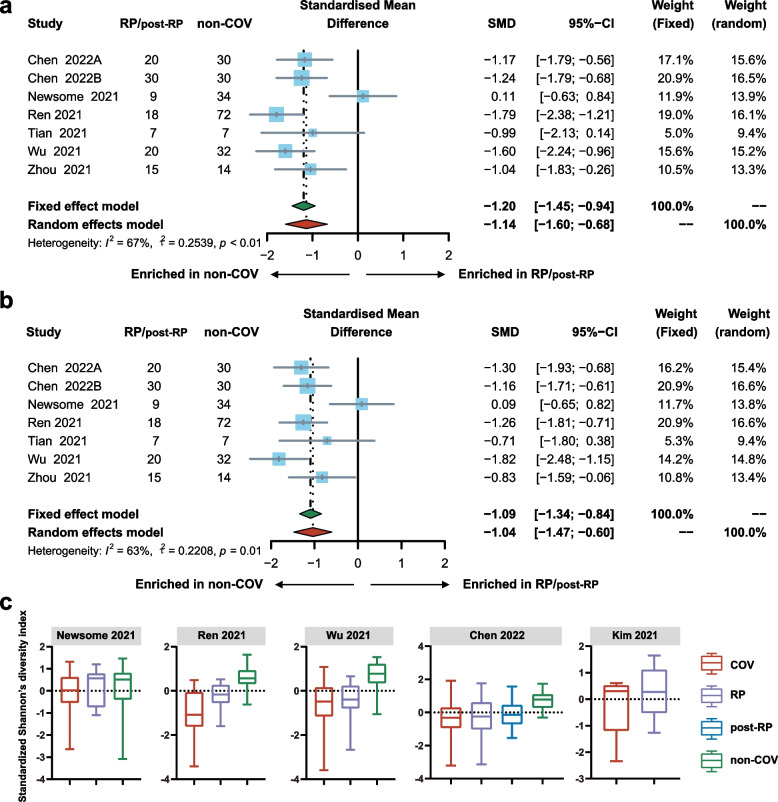

Microbial diversity was decreased in RP/post-RP vs. non-COV

A significant decrease in RP/post-RP compared with non-COV was demonstrated by the pooled estimate of alpha diversity using random effects model, including Shannon’s diversity index (SMD = − 1.14; 95% CI, − 1.60 to − 0.68; Fig. 2a), observed species (SMD = − 1.04; 95% CI, − 1.47 to − 0.60; Fig. 2b), Pielou’s evenness (SMD = − 0.94; 95% CI, − 1.37 to − 0.52), and Faith’s phylogenetic diversity (SMD = − 0.80; 95% CI, − 1.21 to − 0.39; Fig. S6). Sensitivity analysis showed that the results remained unchanged after the removal of one study at a time (Fig. S7). There was no publication bias identified by the funnel plots symmetry (Fig. S8). Test for subgroup differences demonstrated no significance when studies stratified by RP and post-RP (Fig. S9). Boxplots of standardized Shannon’s diversity index revealed an increased trend in RP/post-RP compared with COV (Fig. 2c). Boxplots of standardized observed species, standardized Pielou’s evenness and standardized Faith’s phylogenetic diversity demonstrated the same trend within most, though not all individual studies (Fig. S10).

Fig. 2.

Differences in alpha diversity between RP/post-RP and non-COV. (a) Forest plot of the differences in Shannon’s diversity index between RP/post-RP and non-COV. (b) Forest plot of the differences in observed species between RP/post-RP and non-COV. (c) Boxplots showing standardized Shannon’s diversity index by SARS-CoV-2 infection status (red = COV, purple = RP, blue = post-RP, and green = non-COV). COV, samples derived from COVID-19 patients; RP, samples derived from COVID-19 recovered patients who with clearance of SARS-CoV-2 RNA (negative conversion of viral RNA) within one month; those with negative conversion of viral RNA more than three months were especially grouped as post-RP; non-COV, samples derived from non-COVID-19 individuals

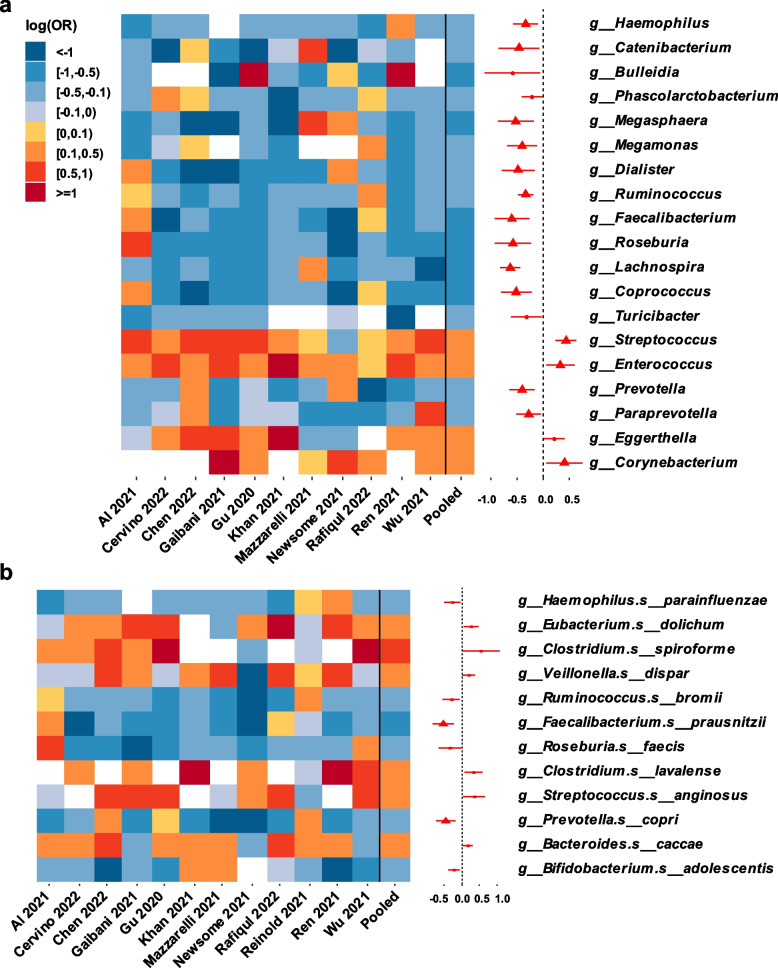

Microbial composition was altered in COV

In a subset of twelve studies reporting the comparison of gut microbiota between COV and non-COV (one study removed as the fit did not converge), at the genus level, COV had significantly lower relative abundances of Haemophilus, Catenibacterium, Megasphaera, Megamonas, Dialister, Ruminococcus, Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, Lachnospira, Coprococcus, Prevotella and Paraprevotella, as well as significantly higher relative abundances of Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Corynebacterium as compared to non-COV in the pooled log (OR) estimate from a random-effects meta-analysis (all FDR-adjusted P < 0.1; Fig. 3a, Table S3). In a subset of twelve studies, at the species level, COV had significantly lower relative abundances of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Prevotella copri as compared to non-COV in the pooled log (OR) estimate (all FDR-adjusted P < 0.1; Fig. 3b, Table S3). The results remained similar in sensitivity analyses when excluding either of the included studies (data not shown). To examine whether these differences were driven mostly by studies from China, we also removed the four Chinese studies in the sensitivity analysis, though a few aforementioned genera were not significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons, the results without adjustment for multiple comparisons did not change substantially (Fig. S11 and Table S4). This suggested that our results were robust to a certain extent, as a strict adjustment for multiple comparisons is not required at all times [44]. In a subset of three studies with available data on COVID-19 patients with different severity levels, at the genus level, the relative abundances of Roseburia (log (OR) = − 0.31; P = 0.018; FDR-adjusted P = 0.962) and Faecalibacterium (log (OR) = − 0.49; P = 0.046; FDR-adjusted P = 0.962) showed a non-significant decrease in severe COVID-19 patients compared with non-severe COVID-19 patients after adjusting for multiple testing (Table S5).

Fig. 3.

Differential gut microbial composition between COV and non-COV (a) at genus level, and (b) at species level. Heatmap showed log (OR) of relative abundances of bacterial taxa between COV and non-COV across each study. The bacterial taxa unavailable in a particular study were in white in heatmap. Forest plot indicated pooled log (OR) estimate and 95% CI of relative abundances of bacterial taxa between COV and non-COV across all studies included. Log (OR) estimates were from GAMLSS-BEZI and Random Effects Meta-analysis. Only bacterial taxa with pooled P of pooled log (OR) estimates below 0.05 were displayed. Pooled log (OR) estimates with FDR-adjusted pooled P < 0.1 were showed as red triangles. Log (OR) > 0 denoted an increase and log (OR) < 0 denoted a decrease of taxa relative abundance in COV compared with non-COV. COV, samples derived from COVID-19 patients; non-COV, samples derived from non-COVID-19 individuals

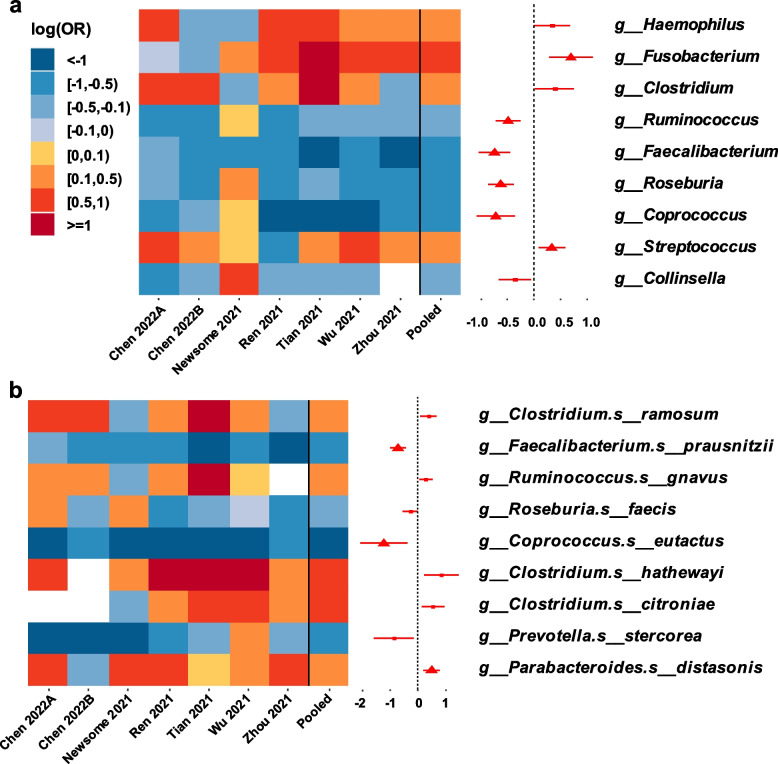

Microbial composition was altered in RP/post-RP

In a subset of six studies (Chen 2022 study [26] involved both RP dataset and post-RP dataset), at the genus level, the relative abundances of Ruminococcus, Faecalibacterium, Roseburia and Coprococcus were found to be significantly decreased, together with the relative abundances of Fusobacterium and Streptococcus were found to be significantly increased in RP/post-RP compared with non-COV in the pooled log (OR) estimate from a random-effects meta-analysis (all FDR-adjusted P < 0.1; Fig. 4a, Table S6). At the species level, the relative abundances of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Coprococcus eutactus were significantly decreased, while the relative abundance of Parabacteroides distasonis was significantly increased in RP/post-RP compared with non-COV in the pooled log (OR) estimate (all FDR-adjusted P < 0.1; Fig. 4b). Results did not change substantially in sensitivity analyses when excluding either of the included studies (data not shown). Fewer alterations were observed in the gut microbiota between COV and RP/post-RP at the genus level. At the species level, Clostridium clostridioforme was detected to be significantly decreased and Bifidobacterium breve was detected to be significantly increased in COV as compared to RP/post-RP (Table S7).

Fig. 4.

Differential gut microbial composition between RP/post-RP and non-COV (a) at genus level, and (b) at species level. Heatmap showed log (OR) of relative abundances of bacterial taxa between RP/post-RP and non-COV across each study. The bacterial taxa unavailable in a particular study were in white in heatmap. Forest plot indicated pooled log (OR) estimate and 95% CI of relative abundances of bacterial taxa between RP/post-RP and non-COV across all studies included. Log (OR) estimates were from GAMLSS-BEZI and Random Effects Meta-analysis. Only bacterial taxa with pooled P of pooled log (OR) estimates below 0.05 were displayed. Pooled log (OR) estimates with FDR-adjusted pooled P < 0.1 were showed as red triangles. Log (OR) > 0 denoted an increase and log (OR) < 0 denoted a decrease of taxa relative abundance in RP/post-RP compared with non-COV. RP, samples derived from COVID-19 recovered patients who with clearance of SARS-CoV-2 RNA (negative conversion of viral RNA) within one month; those with negative conversion of viral RNA more than three months were especially grouped as post-RP; non-COV, samples derived from non-COVID-19 individuals

Discussion

Our meta-analysis revealed consistent alterations in gut microbial diversity and microbial composition in COVID-19 patients during the acute and recovery phases. Owing to the larger datasets composed of populations from different geographic regions and the consistent method workflow for analyses, our meta-analysis provides more precise estimates of the potential effects and more robust results than a single study.

Our results showed substantial gut microbiota shifts in COVID-19 patients during the acute phase. Most consistently, a significant decrease in the gut microbiota of COVID-19 patients was observed as measured by four commonly applied alpha diversity indices. Decreased diversity in gut microbiota has frequently been considered as a hallmark of diseases, such as HIV infection, recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection, inflammatory bowel disease [45–47]. In addition, decreased diversity can predict mortality in hematopoietic stem cell recipients [48]. High heterogeneity was found in alpha diversity analyses of COV vs. non-COV. However, sensitivity analyses showed similar findings, and our meta-analysis results in alpha diversity were roughly concordant with the original researches, implying that our results are robust. We further demonstrated alterations in gut microbial composition of COVID-19 patients. The genera Megasphaera, Dialister, Ruminococcus, Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, Lachnospira, and Prevotella were decreased in COVID-19 patients. As these genera are the butyrate-producing genera [19, 49, 50], the associations between gut dysbiosis and SARS-CoV-2 infection may be partly mediated by short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), mainly acetate, propionate and butyrate, which play vital roles in maintaining mucosal integrity and exerting anti-inflammatory effects via macrophage function and down-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines [49, 51, 52]. Likewise, lower abundances of Faecalibacterium, Dialister, and Lachnospira were also observed in COVID-19 patients in a metagenomic study [53]. A previous systematic review reported that a reduction in abundances of Faecalibacterium, Ruminococcus, and Prevotella was associated with higher systemic inflammation characterized by increased high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) and IL-6 [54]. At the species level, significant decreases of F. prausnitzii and P. copri were observed in COVID-19 patients in our meta-analysis, which is consistent with several metagenomic studies [53, 55, 56]. F. prausnitzii, known for its anti-inflammatory properties, can down-regulate the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6, TNF-α, and TNF-β through multiple pathways [57–59]. One metagenomic study reported that the association bewteen higher abundance of P. copri and less vaccine adverse events is likely mediated via their anti-inflammatory properties, suggesting a beneficial role of P. copri in host immune homeostasis [60]. In addition, our meta-analysis demonstrated that the opportunistic pathogens Streptococcus, Enterococcus, and Corynebacterium were enriched in COVID-19 patients as compared to non-COVID-19 individuals. Streptococcus was associated with increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-18, TNF-α, and IFN-γ [61]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines may in turn predispose host to gut dysbiosis and consequently increase intestinal permeability [62]. Correspondingly, Oliva et al. [63] showed that COVID-19 patients displayed a high level of microbial translocation and increased gut permeability. Together, these evidence suggested that the decrease of anti-inflammatory butyrate-producing bacteria and enrichment of pro-inflammatory bacteria in COVID-19 patients during the acute phase might disturb intestinal barrier function and precipitate microbial translocation, which may further drive immune dysfunction [53].

The alpha diversity indices of gut microbiota in COVID-19 recovered patients were significantly lower than that of non-COVID-19 individuals, which implied that the gut microbiota of COVID-19 recovered patients were still in unhealthy ecostates. Nevertheless, the diversity showed an increase trend in recovered patients compared to COVID-19 patients during the acute phase, suggesting the unhealthy ecostates progressed towards the healthy ecostate after clearance of SARS-CoV-2. Differential abundance analyses revealed that the composition of gut microbiota in recovered patients was broadly closed to that of COVID-19 patients in the acute phase, but different from that of non-COVID-19 individuals to a certain extent. Zhang et al. [55] revealed that gut microbiota in COVID-19 patients manifested lasting impairment of SCFAs and L-isoleucine biosynthesis after disease resolution. Correspondingly, a high proportion of COVID-19 patients exhibited long-term immunologic effects after discharge [64]. Gut dysbiosis that persisted even after clearance of SARS-CoV-2, may be along with persistent gut barrier dysfunction and increased microbial translocation, driving systemic inflammation and promoting long-term immunologic effects in COVID-19 patients. Given the clinical relevance of microbiome disruption in patients with prolonged illness [65], the association between intestinal microbiome disruption and long COVID-19 needs further validation. Probiotics have been proposed for COVID-19 [16, 17, 50, 66]; however, most probiotics currently used are commonly beneficial to multiple diseases. Specific and disease-oriented probiotics are urgently needed, which can effectively promote the health and provide insight into how microbiomes may have restored health [67–69]. Moreover, approaches aimed to restore impaired gut barrier function in COVID-19 patients might be valuable therapeutic strategies.

This study has several limitations. First, we could not include medications and gastrointestinal symptoms during the acute phase and other demographic factors as covariates in the GAMLSS-BEZI model due to insufficient metadata. Consequently, it was not possible to assess these factors on gut microbiota of COVID-19 patients. A more robust cohort of healthy volunteers from whom a baseline sample before COVID-19 diagnosis and then follow-up samples before and after medications in case of COVID-19 diagnosis are collected, would allow deeper investigation of COVID-specific effects on the gut mocrobiota. Our meta-analysis integrated findings of the original studies since most of these studies were conducted without adjusting for any relevant covariates. Second, several studies included in our meta-analysis were small in size, especially studies involved recovered patients, due to the difficulty in recruiting of recovered patients after discharge. However, sensitivity analyses that removing either of the included studies imply that our results are robust. Further, in order to examine whether the differences were driven entirely by Chinese studies, we conducted sensitivity analyses in which removing Chinese studies in the differential abundance analysis of COV vs. non-COV, and the results did not change substantially. Third, since only a few studies collected the information of disease severity, there may be bias in our results of overall non-severe vs. severe analysis. To determine how exactly disease severity might affect gut microbiota in COVID-19, further large sample studies with more focus on different disease severity levels are suggested.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis reported a dysbiotic gut bacterial profile in COVID-19 patients during the acute phase, characterized by depletion of anti-inflammatory butyrate-producing bacteria and enrichment of taxa with pro-inflammatory properties. In addition, gut dysbiosis persisted even after clearance of SARS-CoV-2. Our analysis presents synthesizing knowledge of the current understanding of COVID-19 microbiology based on 16S rRNA gene datasets and provides evidence for future research on the specific COVID-19 associated bacteria. In future work, studies on the specific species of the COVID-19-related bacterial taxa and robust cohort studies with more focus on adjusting for covariates, are suggested to further understand the roles of gut mocrobiota in onset and progression of COVID-19.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

A systematic literature review was conducted for relevant studies published prior to May 2022 in PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, and Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with keyword and controlled vocabulary terms for COVID-19 and the gut microbiota (see Table S1 for the detailed search strategy). The inclusion criteria for eligible studies of our meta-analysis were as follows: all studies had to (i) be focused on assessing the relationships between the gut microbiota and COVID-19; (ii) the study subjects are ≥18 years old; (iii) use human clinical samples; (iv) include a comparative non-COVID-19 control, unless the study was focused on the gut microbiota of COVID-19 patients with different severity levels; (v) perform 16S rRNA gene sequencing; (vi) have publicly available raw data and corresponding metadata or made available upon request by personal communication with the authors; and (vii) be written in English. Review articles, case reports, or studies without full data available were excluded. Two independent reviewers (X.M.C. and Y.F.L.) assessed each article; differences were resolved by consensus. Since data of our study was publicly available from known publications, patient consent or institutional review board approval was not required.

Study population sampling

We included only stool samples or rectal swabs. Samples were assigned to different groups before downstream analyses. Designation of the group relied on the information or the metadata provided by the initial study. Samples derived from COVID-19 patients in the acute phase who were detected positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA were grouped as COV. Samples derived from SARS-CoV-2 non-infected subjects who were healthy individuals or seen by the hospital for unrelated respiratory medical conditions were grouped as non-COV. Samples derived from COVID-19 recovered patients who with clearance of SARS-CoV-2 RNA (negative conversion of viral RNA) within one month were grouped as RP; those with negative conversion of viral RNA more than three months were especially grouped as post-RP.

Data processing

Raw sequencing data from each included study were processed separately through a standardized pipeline in QIIME2 (Version 2020.6) [70]. After demultiplexing, the DADA2 plugin was used to perform sequence quality control and construct the feature table of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) [71]. Sequences of mitochondria, or chloroplast, were removed from further analysis. For taxonomic structure analysis, taxonomy was assigned to ASVs using a pre-trained GREENGENES 13_8 99% database and the q2-feature-classifier plugin [72]. Alpha diversity analysis including Shannon’s diversity index, observed species, Pielou’s evenness and Faith’s phylogenetic diversity were calculated using the core-diversity plugin of QIIME2. Prior to the alpha diversity analysis, the feature table of each dataset was subsampled to an even level of coverage. For the available longitudinal sample data, we analyzed only the first sample for the COV group and the last sample for the RP group by date.

Data synthesis and analysis

Meta-analyses for four measures of alpha diversity were performed utilizing the R package meta and metafor (R version 4.1.0) [73]. Fixed and random effects model estimates were calculated by Hedges’ g standardized mean difference statistic; those with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) above or below 0 were regarded as statistically significant. The I2 (percentage of variation reflecting true heterogeneity), τ2 (random-effects between study variance), and p-value from Cochran’s Q test was used to assess statistically significant heterogeneity. Asymmetry of the funnel plots were applied to detect the publication biases when the number of studies is greater than five. Begg’s correlation test and Egger’s regression test were also used to detect the publication biases when the number of studies is greater than ten, with a P value < 0.1 indicating a potential bias [74, 75]. Standardized alpha diversity indexes were calculated through mean centering to zero within each study and scaling to unit variance. Boxplots were generated using Prism 8.3.0 (GraphPad Software).

Counts of bacterial taxa were converted to relative abundances. Relative abundance data were then filtered to retain only the taxa that had an average relative abundance of at least 0.005% and were present in at least 5% of samples in that study. Generalized Additive Models for Location, Scale and Shape (GAMLSS) with a zero-inflated beta distribution (BEZI) implemented in the R package gamlss were used to examine relative abundances of bacterial taxa in each study [76, 77]. To evaluate the overall effects while addressing heterogeneity across studies, we applied random-effects meta-analysis models with inverse variance weighting and DerSimonian–Laird estimator for between-study variance across all included studies to combine the adjusted estimates and their standard errors. Meta-analyses were done for only bacterial taxa whose adjusted estimates and standard errors were available in at least 50% of the number of included studies. To account for the robustness of the results, sensitivity analyses were performed by removing one study at a time. All statistical tests were two-sided. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant and a false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P value of less than 0.1 was considered significant after adjusting for multiple testing.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank authors of Kim 2021 study [30], Mazzarelli 2021 study [31], and Gaibani 2021 study [27] for their response and providing the data of the studies. We thank other authors for sharing their data sets in publicly available database.

Authors’ contributions

J.H.L. and C.G. conceived and designed the study. J.H.L. secured the funding. X.M.C., Y.L.Z., Y.F.L., Q.W., and J.N.W. performed the literature search, data curation and validation. X.M.C. and Y.F.L. analyzed the sequencing data. S.K.P. provided sequencing datasets. X.M.C., and Y.L.Z. wrote the manuscript with suggestions from other authors. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Project (2018YFE0208000), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JSGG20220606142207017), the Guangdong Province Drug Administration Science and Technology Innovation Project (2022ZDZ12) and the Central Government Guides Local Science and Technology Development Funds to Freely Explore Basic Research Project (2021Szvup171).

Availability of data and materials

Raw data for this meta-analysis are available online (see Table S8). The R script used for this meta-analysis is included in the Supplementary Text and has been uploaded on https://github.com/XiaominCheng/16S_gut_meta. The authors confirmed that all supporting data have been provided within the article or through supplementary materials.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiaomin Cheng and Yali Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Cheng Guo, Email: cg2984@cumc.columbia.edu.

Jiahai Lu, Email: lujiahai@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Aleem A, Akbar Samad AB, Slenker AK. Emerging Variants of SARS-CoV-2 And Novel Therapeutics Against Coronavirus (COVID-19). Treasure Island (FL); 2022.

- 2.Li J, Lai S, Gao GF, Shi W. The emergence, genomic diversity and global spread of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021;600(7889):408–418. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan Y, Li X, Zhang L, Wan S, Zhang L, Zhou F. SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant: recent progress and future perspectives. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):141. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00997-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sencio V, Barthelemy A, Tavares LP, Machado MG, Soulard D, Cuinat C, et al. Gut Dysbiosis during influenza contributes to pulmonary pneumococcal Superinfection through altered short-Chain fatty acid production. Cell Rep. 2020;30(9):2934–2947.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Lin H, Cole M, Morris A, Martinson J, McKay H, et al. Signature changes in gut microbiome are associated with increased susceptibility to HIV-1 infection in MSM. Microbiome. 2021;9(1):237. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01168-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winkler ES, Shrihari S, Hykes BL, Jr, Handley SA, Andhey PS, Huang YS, et al. The Intestinal Microbiome Restricts Alphavirus Infection and Dissemination through a Bile Acid-Type I IFN Signaling Axis. Cell. 2020;182(4):901–918.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarkar A, Harty S, Moeller AH, Klein SL, Erdman SE, Friston KJ, et al. The gut microbiome as a biomarker of differential susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27(12):1115–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2021.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mao R, Qiu Y, He JS, Tan JY, Li XH, Liang J, et al. Manifestations and prognosis of gastrointestinal and liver involvement in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(7):667–678. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30126-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Effenberger M, Grabherr F, Mayr L, Schwaerzler J, Nairz M, Seifert M, et al. Faecal calprotectin indicates intestinal inflammation in COVID-19. Gut. 2020;69(8):1543–1544. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zuo T, Zhang F, Lui GCY, Yeoh YK, Li AYL, Zhan H, et al. Alterations in gut microbiota of patients with COVID-19 during time of hospitalization. Gastroenterology. 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32442562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, Function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell 2020;181(2):281-292.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Gheblawi M, Wang K, Viveiros A, Nguyen Q, Zhong JC, Turner AJ, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 receptor and regulator of the renin-angiotensin system: celebrating the 20th anniversary of the discovery of ACE2. Circ Res. 2020;126(10):1456–1474. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saponaro F, Rutigliano G, Sestito S, Bandini L, Storti B, Bizzarri R, et al. ACE2 in the era of SARS-CoV-2: controversies and novel perspectives. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:588618. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.588618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Q, Mak JWY, Su Q, Yeoh YK, Lui GC, Ng SSS, et al. Gut microbiota dynamics in a prospective cohort of patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Gut. 2022;71(3):544–552. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutierrez-Castrellon P, Gandara-Marti T, Abreu YAAT, Nieto-Rufino CD, Lopez-Orduna E, Jimenez-Escobar I, et al. Probiotic improves symptomatic and viral clearance in Covid19 outpatients: a randomized, quadruple-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Gut Microbes. 2022;14(1):2018899. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.2018899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu C, Xu Q, Cao Z, Pan D, Zhu Y, Wang S, et al. The volatile and heterogeneous gut microbiota shifts of COVID-19 patients over the course of a probiotics-assisted therapy. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11(12):e643. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al Bataineh MT, Henschel A, Mousa M, Daou M, Waasia F, Kannout H, et al. Gut microbiota interplay with COVID-19 reveals links to host lipid metabolism among middle eastern populations. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:761067. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.761067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cervino ACL, Fabre R, Plassais J, Gbikpi-Benissan G, Petat E, Le Quellenec E, et al. Results from EDIFICE : A French pilot study on COVID-19 and the gut microbiome in a hospital environment. medRxiv. 2022;(2022.02.06):22269945. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/medrxiv/early/2022/02/08/2022.02.06.22269945.full.pdf.

- 20.Rafiqul Islam SM, Foysal MJ, Hoque MN, Mehedi HMH, Rob MA, Salauddin A, et al. Dysbiosis of Oral and gut microbiomes in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients in Bangladesh: elucidating the role of opportunistic gut microbes. Front Med. 2022;9:163. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.821777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reinold J, Farahpour F, Fehring C, Dolff S, Konik M, Korth J, et al. A pro-inflammatory gut microbiome characterizes SARS-CoV-2 infected patients and a reduction in the connectivity of an anti-inflammatory bacterial network associates with severe COVID-19. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:747816. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.747816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren Z, Wang H, Cui G, Lu H, Wang L, Luo H, et al. Alterations in the human oral and gut microbiomes and lipidomics in COVID-19. Gut [Internet]. 2021;2021. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33789966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Tian Y, Sun KY, Meng TQ, Ye Z, Guo SM, Li ZM, et al. Gut microbiota may not be fully restored in recovered COVID-19 patients after 3-month recovery. Front Nutr. 2021;2021(8):638825. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.638825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu Y, Cheng X, Jiang G, Tang H, Ming S, Tang L, et al. Altered oral and gut microbiota and its association with SARS-CoV-2 viral load in COVID-19 patients during hospitalization. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2021;7(1):61. doi: 10.1038/s41522-021-00232-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou Y, Zhang J, Zhang D, Ma WL, Wang X. Linking the gut microbiota to persistent symptoms in survivors of COVID-19 after discharge. J Microbiol. 2021;59(10):941–948. doi: 10.1007/s12275-021-1206-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y, Gu S, Chen Y, Lu H, Shi D, Guo J, et al. Six-month follow-up of gut microbiota richness in patients with COVID-19. Gut. 2022;71(1):222. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaibani P, D’Amico F, Bartoletti M, Lombardo D, Rampelli S, Fornaro G, et al. The gut microbiota of critically ill patients with COVID-19. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:670424. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.670424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gu S, Chen Y, Wu Z, Chen Y, Gao H, Lv L, et al. Alterations of the gut microbiota in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 or H1N1 influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(10):2669–2678. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan M, Mathew BJ, Gupta P, Garg G, Khadanga S, Vyas AK, et al. Gut dysbiosis and il-21 response in patients with severe covid-19. Microorganisms. 2021;9(6). Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85107786663&doi=10.3390%2Fmicroorganisms9061292&partnerID=40&md5=f0496e4096852be5ed4bc03c676f4336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Kim HN, Joo EJ, Lee CW, Ahn KS, Kim HL, Park DI, et al. Reversion of gut microbiota during the recovery phase in patients with asymptomatic or mild COVID-19: longitudinal study. Microorganisms. 2021;9(6):1237. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9061237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazzarelli A, Giancola ML, Farina A, Marchioni L, Rueca M, Gruber CEM, et al. 16S rRNA gene sequencing of rectal swab in patients affected by COVID-19. PLoS One. 2021;16(2). Available from: https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&id=L2011134669&from=export. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Moreira-Rosario A, Marques C, Pinheiro H, Araujo JR, Ribeiro P, Rocha R, et al. Gut microbiota diversity and C-reactive protein are predictors of disease severity in COVID-19 patients. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:705020. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.705020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newsome RC, Gauthier J, Hernandez MC, Abraham GE, Robinson TO, Williams HB, et al. The gut microbiome of COVID-19 recovered patients returns to uninfected status in a minority-dominated United States cohort. Gut Microbes. 2021;13(1):1–15. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1926840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jagielski P, Luszczki E, Wnek D, Micek A, Boleslawska I, Piorecka B, et al. Associations of nutritional behavior and gut microbiota with the risk of COVID-19 in healthy Young adults in Poland. Nutrients. 2022;14(2). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35057534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Junior ASF, Borgonovi TF, de Salis LVV, Leite AZ, Dantas AS, de Salis GVV, et al. Persistent intestinal dysbiosis after SARS-CoV-2 infection in Brazilian patients. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mizutani T, Ishizaka A, Koga M, Ikeuchi K, Saito M, Adachi E, et al. Correlation analysis between gut microbiota alterations and the cytokine response in patients with coronavirus disease during hospitalization. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;0(0):e0168921. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01689-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schult D, Reitmeier S, Koyumdzhieva P, Lahmer T, Middelhof M, Erber J, et al. Gut bacterial dysbiosis and instability is associated with the onset of complications and mortality in COVID-19. Gut Microbes. 2022;14(1):2031840. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2022.2031840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Venzon M, Bernard-Raichon L, Klein J, Axelrad J, Hussey G, Sullivan A, et al. Gut microbiome dysbiosis during COVID-19 is associated with increased risk for bacteremia and microbial translocation. Res Sq. 2021. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34341786.

- 39.Xu R, Lu R, Zhang T, Wu Q, Cai W, Han X, et al. Temporal association between human upper respiratory and gut bacterial microbiomes during the course of COVID-19 in adults. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):240. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-01796-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Romano S, Savva GM, Bedarf JR, Charles IG, Hildebrand F, Narbad A. Meta-analysis of the Parkinson’s disease gut microbiome suggests alterations linked to intestinal inflammation. NPJ Park Dis. 2021;7(1):27. doi: 10.1038/s41531-021-00156-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nikolova VL, Smith MRB, Hall LJ, Cleare AJ, Stone JM, Young AH. Perturbations in gut microbiota composition in psychiatric disorders: a review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34524405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Chen J, Vitetta L, Henson JD, Hall S. The intestinal microbiota and improving the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccinations. J Funct Foods. 2021;87:104850. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2021.104850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lynn DJ, Benson SC, Lynn MA, Pulendran B. Modulation of immune responses to vaccination by the microbiota: implications and potential mechanisms. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;22(1):33–46. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00554-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Najafi S, Abedini F, Azimzadeh Jamalkandi S, Shariati P, Ahmadi A, Gholami FM. The composition of lung microbiome in lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Microbiol. 2021;21(1):315. doi: 10.1186/s12866-021-02375-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tuddenham SA, Koay WLA, Zhao N, White JR, Ghanem KG, Sears CL, et al. The impact of human immunodeficiency virus infection on gut microbiota alpha-diversity: an individual-level Meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;70(4):615–627. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vasilescu IM, Chifiriuc MC, Pircalabioru GG, Filip R, Bolocan A, Lazar V, et al. Gut Dysbiosis and Clostridioides difficile infection in neonates and adults. Front Microbiol. 2022;12:651081. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.651081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ni J, Wu GD, Albenberg L, Tomov VT. Gut microbiota and IBD: causation or correlation? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(10):573–584. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taur Y, Jenq RR, Perales MA, Littmann ER, Morjaria S, Ling L, et al. The effects of intestinal tract bacterial diversity on mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2014;124(7):1174–1182. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-554725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Louis P, Flint HJ. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Env Microbiol. 2016;19(1):29–41. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen J, Vitetta L. Modulation of gut microbiota for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. J Clin Med. 2021;10(13):2903. doi: 10.3390/jcm10132903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de la Cuesta-Zuluaga J, Mueller NT, Corrales-Agudelo V, Velásquez-Mejía EP, Carmona JA, Abad JM, et al. Metformin Is Associated With Higher Relative Abundance of Mucin-Degrading Akkermansia muciniphila and Several Short-Chain Fatty Acid–Producing Microbiota in the Gut. Diabetes Care. 2016;40(1):54–62. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Montandon SA, Jornayvaz FR. Effects of Antidiabetic drugs on gut microbiota composition. Genes (Basel). 2017;8(10). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28973971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Sun Z, Song ZG, Liu C, Tan S, Lin S, Zhu J, et al. Gut microbiome alterations and gut barrier dysfunction are associated with host immune homeostasis in COVID-19 patients. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-02212-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van den Munckhof ICL, Kurilshikov A, Ter Horst R, Riksen NP, Joosten LAB, Zhernakova A, et al. Role of gut microbiota in chronic low-grade inflammation as potential driver for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a systematic review of human studies. Obes Rev. 2018;19(12):1719–1734. doi: 10.1111/obr.12750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang F, Wan Y, Zuo T, Yeoh YK, Liu Q, Zhang L, et al. Prolonged impairment of short-Chain fatty acid and L-isoleucine biosynthesis in gut microbiome in patients with COVID-19. Gastroenterology. 2021;162(2):548–561 e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou T, Wu J, Zeng Y, Li J, Yan J, Meng W, et al. SARS-CoV-2 triggered oxidative stress and abnormal energy metabolism in gut microbiota. MedComm. 2022;3(1):e112. doi: 10.1002/mco2.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, Lakhdari O, Bermudez-Humaran LG, Gratadoux JJ, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(43):16731–16736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804812105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quevrain E, Maubert MA, Michon C, Chain F, Marquant R, Tailhades J, et al. Identification of an anti-inflammatory protein from Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a commensal bacterium deficient in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2015;65(3):415–425. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ma J, Sun L, Liu Y, Ren H, Shen Y, Bi F, et al. Alter between gut bacteria and blood metabolites and the anti-tumor effects of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in breast cancer. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20(1):82. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-01739-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ng SC, Peng Y, Zhang L, Mok CK, Zhao S, Li A, et al. Gut microbiota composition is associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccine immunogenicity and adverse events. Gut. 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35140064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Alberdi A, Martin Bideguren G, Aizpurua O. Diversity and compositional changes in the gut microbiota of wild and captive vertebrates: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):22660. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02015-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hussain I, Cher GLY, Abid MA, Abid MB. Role of gut microbiome in COVID-19: an insight into pathogenesis and therapeutic potential. Front Immunol. 2021;12:765965. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.765965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oliva A, Miele MC, Di Timoteo F, De Angelis M, Mauro V, Aronica R, et al. Persistent systemic microbial translocation and intestinal damage during coronavirus Disease-19. Front Immunol. 2021;12:708149. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.708149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peluso MJ, Donatelli J, Henrich TJ. Long-term immunologic effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection: leveraging translational research methodology to address emerging questions. Transl Res. 2021;241:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2021.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haran JP, Bradley E, Zeamer AL, Cincotta L, Salive MC, Dutta P, et al. Inflammation-type dysbiosis of the oral microbiome associates with the duration of COVID-19 symptoms and long COVID. JCI Insight. 2021;6(20). Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85117703010&doi=10.1172%2Fjci.insight.152346&partnerID=40&md5=5d1161863c0dcf6bdaa75068498cfc5b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Nguyen QV, Chong LC, Hor YY, Lew LC, Rather IA, Choi SB. Role of probiotics in the management of COVID-19: a computational perspective. Nutrients. 2022;14(2). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35057455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.McFarland LV, Evans CT, Goldstein EJC. Strain-specificity and disease-specificity of probiotic efficacy: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Front Med. 2018;5:124. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsai YL, Lin TL, Chang CJ, Wu TR, Lai WF, Lu CC, et al. Probiotics, prebiotics and amelioration of diseases. J Biomed Sci. 2019;26(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s12929-018-0493-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang Q, Hu J, Feng JW, Hu XT, Wang T, Gong WX, et al. Influenza infection elicits an expansion of gut population of endogenous Bifidobacterium animalis which protects mice against infection. Genome Biol. 2020;21(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02007-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet CC, Al-Ghalith GA, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(8):852–857. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJ, Holmes SP. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13(7):581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McDonald D, Price MN, Goodrich J, Nawrocki EP, DeSantis TZ, Probst A, et al. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J. 2011;6(3):610–618. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Balduzzi S, Rücker G, Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid Based Ment Heal. 2019;22(4):153–160. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication Bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ho NT, Li F, Wang S, Kuhn L. metamicrobiomeR: an R package for analysis of microbiome relative abundance data using zero-inflated beta GAMLSS and meta-analysis across studies using random effects models. BMC Bioinformatics. 2019;20(1):188. doi: 10.1186/s12859-019-2744-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ho NT, Li F, Lee-Sarwar KA, Tun HM, Brown BP, Pannaraj PS, et al. Meta-analysis of effects of exclusive breastfeeding on infant gut microbiota across populations. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4169. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06473-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data for this meta-analysis are available online (see Table S8). The R script used for this meta-analysis is included in the Supplementary Text and has been uploaded on https://github.com/XiaominCheng/16S_gut_meta. The authors confirmed that all supporting data have been provided within the article or through supplementary materials.