Abstract

Introduction

The Cancer Health Assessments Reaching Many study seeks to reduce disparities in genomic care. Two patient advisory committees (PACs) were formed, 1 of English speakers and 1 of Spanish speakers, to vet study processes and materials. Stakeholder engagement in research is relatively new, and we know little about how stakeholders view their engagement. We wanted to learn how patient stakeholders viewed the process, to inform future patient engagement efforts.

Methods

Patients at 2 study sites were invited to serve on 2 PACs. We used an iterative engagement process to solicit and incorporate patient feedback. Much of the PAC feedback on study materials and processes was incorporated. Using surveys and exit interviews, we evaluated stakeholders’ experiences as PAC members.

Results

Nearly all PAC members felt satisfied and included in the study decisions, but surveys and exit interviews suggested the need to improve communications.

Discussion

Although most believed their feedback was used, and most felt included in study decisions, some said they did not know whether their opinions were used to modify materials or approaches. This suggests the need to explain to patient stakeholders the extent to which their feedback was used and to inform them about the impact that other stakeholders, such as institutional review boards, have on decisions.

Conclusion

Our evaluation highlights the value of dedicating resources to stakeholder engagement. Although gathering patient feedback on study materials and processes introduced time constraints and complexity to our study, adaptations to materials and processes furthered study goals.

Keywords: Genomics, disparities, underserved populations, stakeholder engagement, hereditary cancer

Introduction

Research is more likely to align with patients’ needs when their perspectives are taken into account. 1 Patient stakeholder engagement can increase the inclusion of underrepresented populations in research, “increase stakeholder trust[,] and … enhance mutual learning.” 2,3 The process requires the meaningful involvement of members of the populations affected by the research. Although researchers have recognized the importance of involving patient stakeholders, we know little about how to identify and effectively involve them, or how they feel about their engagement. 4 Most studies do not evaluate engagement activities, 5 but evaluations are critical to identify best practices and inform future efforts.

This paper describes lessons from a study involving 2 patient advisory committees (PACs). The goal of establishing the committees was to inform the procedures and patient-facing materials of a large clinical trial in cancer genomics, the Cancer Health Assessments Reaching Many (CHARM) study. CHARM seeks to increase uptake of risk assessment, genetic testing, and genetic counseling for hereditary cancer syndromes among underserved populations, particularly racial and ethnic minorities and individuals of low socioeconomic status and limited literacy. We describe our process of engagement with the PACs and report PAC participants’ assessments of their experience as stakeholders using both interviews and surveys. To evaluate stakeholder engagement, we used the framework suggested by Esmail et al 6 and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), 7 assessing various dimensions within contextual and process categories.

Methods

The CHARM study, 1 of 6 studies within the Clinical Sequencing Evidence-Generating Research consortium, seeks to engage populations historically underrepresented in genomics research 8 and to reduce health disparities in the use of genetic services. 9 CHARM 10 is implementing a hereditary cancer risk assessment program in adults (18–49) in 2 health care systems to assess uptake of clinical exome sequencing and its impact on patient care. This program aims to substantially improve clinical care by making genomic services widely accessible.

The study team includes experts in bioethics, genetics, medical anthropology, genetic counseling, behavioral health, and limited-literacy populations. This team created all patient-facing materials, including cancer risk assessment tools, to make them accessible for English speakers with limited literacy. Additionally, to promote Spanish speakers’ participation, all materials were translated into Spanish and culturally adapted for accessibility. To anticipate and address participants’ needs, concerns, and preferences, 2 separate PACs were formed, 1 of English speakers and 1 of Spanish speakers. Both provided input on CHARM processes and materials. 11

Setting

Patients from Kaiser Permanente Northwest in Portland, Oregon, and Denver Health (DH) in Colorado were invited to serve as PAC members. Kaiser Permanente Northwest serves more than 600,000 members in northwest Oregon and southwest Washington. Members are demographically representative of the coverage area—70% are non-Hispanic white, 9% self-identify as Hispanic, and nearly 10% receive Medicaid. DH is an integrated health system including a network of 9 federally qualified health centers with 170,000 patients. Over 75% of DH patients are racial/ethnic minorities (56% Hispanic, 16% Black), 70% live at or below 200% of the federal poverty level, 15% are uninsured, and 70% receive Medicaid or Medicare. 12

Evaluation of patient experience

At the completion of the PACs’ feedback activities, each member was invited to participate in a telephone interview to assess their experience. We interviewed 16 of the 17 PAC members. Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish by 2 CHARM staff members. The study’s Stakeholder Engagement Workgroup developed an interview guide grounded in the theoretical framework of Esmail et al. 6 Items reflected context (the conditions that underpin and support engagement) and process (how engagement is implemented), as well as 9 hypothesized impacts of engagement. 6 We focused on the following: empowering patients, democracy and accountability, moral obligation, evaluation of engagement (satisfaction), and measures of context and process. The interview guide was also framed within the PCORI’s 7 Engagement Principles: Reciprocal Relationships, Co-learning, Partnership and Trust, Transparency, and Honesty. 7 Surveys contained 34 items; 11 were open-ended questions, and 23 presented Likert scale options (eg, Very Satisfied, Satisfied, Neutral, Dissatisfied, Very Dissatisfied, Prefer Not To Answer). Table 1 presents all survey items, the theoretical framework from which each item derives, and the assessment domain each item represented. We developed different surveys for the English-language and Spanish-language PACs because the work they performed differed both in nature and format. For example, whereas the English-language PAC provided feedback on study processes and materials, the Spanish-language PAC provided feedback only on specific wording and graphics used in materials. Similarly, whereas the English-language PAC provided its feedback during in-person group meetings and telephone interviews, the Spanish-language PAC provided feedback only via individual telephone interviews. For this reason, the Spanish-language PAC survey omitted 5 questions relevant only to the English-language PAC in-person meeting experience.

Table 1:

Questions asked on PAC member survey

| No. | Question | Domain | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Describe why we wanted your feedback for CHARM. | Understanding of PAC task | CHARM |

| 2 | How satisfied were you with your experience with the PAC? | Patient empowerment | Esmail et al |

| 3 | What went well? | Advice for improvement | CHARM |

| 4 | What could we have done better? | Advice for improvement | CHARM |

| 5 | What were some surprises? | Advice for improvement | CHARM |

| 6 | Did the PAC represent the diversity of Kaiser Permanente Northwest/DH? a | Partnership and trust | PCORI |

| 7 | What do you think of the number of group meetings? a | Context: Time allocation Process: Timing |

Esmail et al |

| 8 | What do you think of the number of phone interviews? | Context: Time allocation Process: Timing |

Esmail et al |

| 9 | What do you think of the number of times we reached out to you? a | Context: Time allocation Process: Timing |

Esmail et al |

| 10 | What could we do to make it easier to review materials? | Advice for improvement | CHARM |

| 11 | What could we do to make it easier to participate in phone calls? | Advice for improvement | CHARM |

| 12 | What could we do to improve payment for your time? | Advice for improvement | CHARM |

| 13 | I was involved in deciding how and how often to work with team. | Reciprocal relationships | PCORI |

| 14 | I was paid in a fair way. | Partnership and trust | PCORI |

| 15 | It was easy to do phone interviews. | Partnership and trust | PCORI |

| 16 | It was easy to come to group meetings. | Partnership and trust | PCORI |

| 17 | I had good understanding of PAC work when I agreed. | Partnership and trust | PCORI |

| 18 | What I was asked to do was reasonable and thoughtful. | Partnership and trust | PORI |

| 19 | CHARM showed commitment to diversity. | Partnership and trust | PCORI |

| 20 | CHARM showed commitment to respecting my cultural background. | Partnership and trust | PCORI |

| 21 | CHARM helped me understand the research process. | Co-learn | PCORI |

| 22 | CHARM valued my opinions. | Co-learn | PCORI |

| 23 | In phone interviews, I got to share my opinions. | Co-learn | PCORI |

| 24 | In group meetings, I got to share my opinions. | Co-learn | PCORI |

| 25 | I felt included in the decisions in CHARM. | Transparency | PCORI |

| 26 | I got the information I needed to understand and give feedback. | Transparency | PCORI |

| 27 | The CHARM team was committed to open and honest communication. | Transparency | PCORI |

| 28 | CHARM used feedback from the PAC. | Co-learn | PORI |

| 29 | The PAC made CHARM more relevant to diverse patients. | Partnership and trust | PCORI |

| 30 | How did the PAC change your opinions about research? | Patient empowerment | Esmail et al |

| 31 | I would recommend to a friend to participate in research. | Democracy | Esmail et al |

| 32 | What have you learned by working in the PAC? | Patient empowerment | Esmail et al |

| 33 | Future work in the PAC? | Democracy | Esmail et al |

| 34 | Other feedback? | Advice for improvement | CHARM |

Indicates questions asked only to members of the English-language PAC. All other questions were asked to members of both PACS.

CHARM, Cancer Health Assessments Reaching Man; PAC, Patient Advisory Committee; PCORI, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Analyses

Data from closed-ended survey items were summarized separately for English- and Spanish-language PACs, and comments were noted. We summarized responses to open-ended questions, which mapped onto 3 general content areas: suggested improvements for future PACs, unexpected learning experiences for PAC members, and PAC members’ perspectives on research participation.

Results

Inclusion criteria for PAC membership mirrored the target study population of predominantly healthy adults. We sought racial, sexual, and ethnic minorities, non-native English speakers, and individuals with limited formal schooling. 13,14

At our request, Kaiser Permanente Northwest and DH physicians identified potential English- and Spanish-speaking PAC members and briefly described the project to them. Bilingual recruiters called patients expressing interest and told them about the PAC’s purpose, activities, and compensation (a $30 gift card after each meeting or interview). If individuals remained interested, recruiters gathered demographic information and assessed suitability (eg, comfort sharing opinions, past reactions when others disagreed).

Seventeen patients participated, with 10 in the Spanish-language PAC (3 from DH, 7 from Kaiser Permanente Northwest) and 7 in the English-language PAC (all from DH). English-speaking and Spanish-speaking PAC members did not differ substantially in terms of age, education, or health insurance (data not shown). PAC members’ mean age was 44 years (SD = 13.6; range = 20–69), most (14/17) were women, and approximately half (10/17) had attended at least some college.

Development of study materials

Five workgroups, composed of subject matter experts, were tasked with developing the following study processes and associated materials: Recruitment (brochures and postcards), Consent (consent forms), Risk Assessment (adapted risk assessment tools), Lab (instructions for genetic testing kits), and Genetic Counseling (letters summarizing test results). A Literacy Adaptation Workgroup reviewed all materials to ensure a fifth-grade reading level and consistency before being sent to the PACs for feedback. Finally, the Stakeholder Engagement Workgroup coordinated and facilitated the PACs’ review of materials.

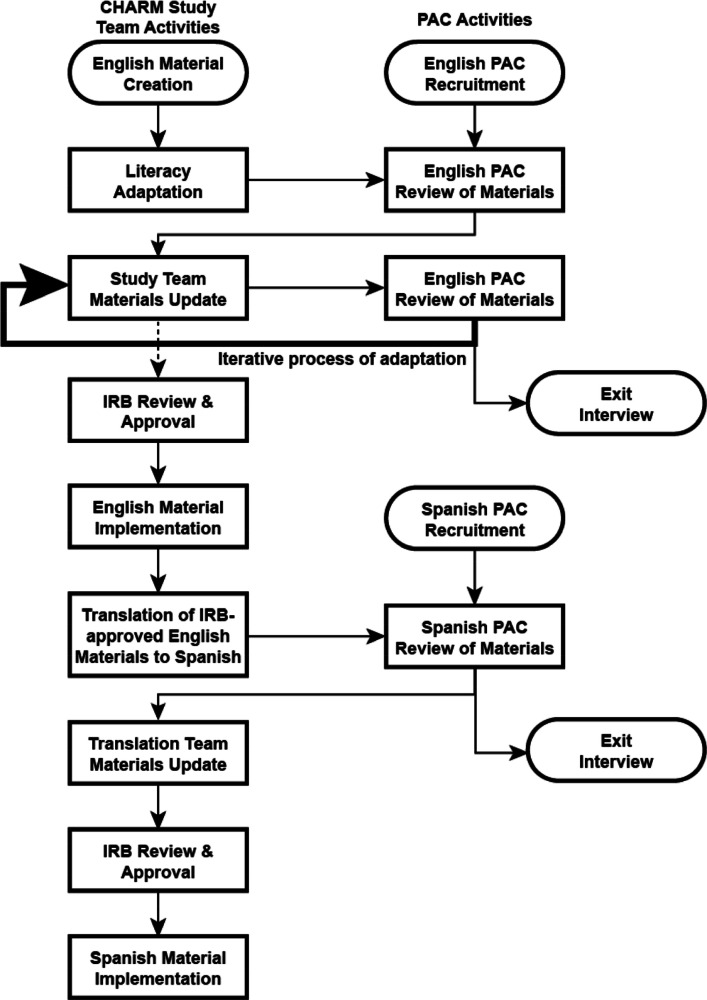

Figure 1 shows the process for PAC feedback about study materials. The Stakeholder Engagement Workgroup proposed a sequence of topics and materials and worked iteratively with respective workgroups to determine the best way to present and obtain feedback on materials and study processes. Literacy-adapted materials and study processes were first reviewed by the English-language PAC; once reviewed, impacted workgroups received a summary of feedback. Workgroups considered the feedback, updated materials where appropriate, and responded to the Stakeholder Engagement Workgroup when suggestions were not methodologically or scientifically appropriate and not implemented. 11 In some cases, updated materials were reviewed again by the PAC and returned to a workgroup for updates.

Figure 1:

Figure 1 shows the process for obtaining PAC feedback about study materials. It shows the flow of CHARM study team activities and materials, as well as how materials were informed by input from the English-language and Spanish-language PACs. IRB = Institutional Review Board. PAC = Patient Advisory Committee.

Finalized materials and processes were sent to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) for review. If the IRB requested changes, materials were sent back to the study team, changed, and resubmitted. Following IRB approval, English-language materials were translated into Spanish. Spanish translation was led by a CHARM co-investigator (NML), a certified translator specialized in adapting health-related materials for limited-literacy populations. Translated materials were sent to the Spanish-language PAC for review and returned to the Translation Workgroup for updates. Updated Spanish-language materials were then sent to the IRB. Following IRB approval, English- and Spanish-language materials were published as patient-facing documents.

Review of materials

English-language PAC

Each group meeting took place in person near the DH medical center and lasted about 90 minutes. CHARM study staff with stakeholder engagement expertise (CM) facilitated and audio-recorded the sessions, which were conducted as webinars; members of our multisite teams could listen in on and observe in real time PAC members’ reactions and feedback, and participate in the webinar as appropriate. The Stakeholder Workgroup spent considerable time tailoring presentations to the PAC so that they were clear and accessible, and elicited information that would be useful. The workgroups selected materials for PAC feedback and attempted to present materials to the PAC in an order that paralleled participant flow through the study. However, due to delays in materials from some workgroups, and in order to move forward with other materials that were ready, materials were not always presented in the order intended.

Materials or processes were shown to participants as a PowerPoint or in paper form and were read out loud to aid those with limited literacy. In the first meeting, the facilitator explained the process and emphasized the importance of hearing all viewpoints and reaching consensus, where possible.

The first session presented a study overview, followed by a detailed description of what participants would do in the study and the communications they would encounter—recruitment materials, consent forms, risk-screening surveys, and, if appropriate, a kit requiring a saliva sample for genetic testing, as well as receiving test results from a genetic counselor by telephone. The PAC reviewed the study’s recruitment postcard and brochure, and members were asked to provide feedback (eg, “Would you contact the study for more information? Would you feel comfortable being approached in person?”).

The second session centered on the family history risk assessment tool, a modified version of the PREMM5 15 and Breast Cancer Genetics Referral Screening Tool 16 3.0. PAC members suggested easy-to-understand language for health concepts (eg, describing “hereditary cancer” as “cancer in your family”), literacy aids such as a family tree diagram, and wording for questions for individuals who were adopted. The group also reviewed the consent process, suggested plain language to describe study objectives, and provided feedback on the study’s description of how information would be kept confidential.

The third session sought to refine language in the risk assessment tool, and the fourth and final session centered on the approach and wording to be used by genetic counselors returning test results by telephone. PAC members suggested that the counselor repeat the participant’s family history at the beginning of the call, avoid saying “you screened positive” (because “positive” suggested a “good result”), and emphasize actions to diminish risk.

Between PAC group sessions, we conducted individual telephone interviews with English-language PAC members (KJS) to obtain more detailed feedback. In contrast to group sessions, which encouraged “big picture” feedback, these interviews focused on comprehension, layout, and suggestions for alternative wording. Interviews were scheduled at PAC members’ convenience, and materials were delivered to PAC members a week prior to the interview. Responses were entered directly into a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) 17,18 database hosted at the University of Washington. PAC feedback was then returned to the appropriate workgroups, which updated the materials.

Spanish-language PAC

Feedback sessions for the English- and Spanish-language PACs were conducted sequentially, rather than in parallel. The scope of work by the Spanish-language PAC involved soliciting feedback only on specific wording used in the Spanish translation, rather than on study processes. We originally intended to obtain feedback from both PACs in a group setting, but because most Spanish-language PAC members had irregular work shifts that changed unexpectedly, it was impossible for the Spanish-language PAC to meet in a group. Instead, all feedback was obtained individually, with 1 initial in-person orientation meeting followed by 4 telephone interviews.

During the in-person orientation meeting, the coordinator of the Spanish-language PAC (NML) met with each person who expressed an interest in participating at Kaiser Permanente Northwest and DH. She provided basic information about clinical research, including the process of recruitment, informed consent, randomization, participation, and dissemination of findings. She explained the CHARM study’s goal of using genetic information to improve patient care and its focus on cancer that runs in families. She explained the PAC’s task of reviewing and providing feedback on study materials and how this would help the study reach people who normally do not take part in research.

The study team then mailed the Spanish-language PAC members the materials they were asked to review. In cases when PAC members reported not having received the materials, we hand-delivered them to their homes. The study team scheduled a 1-hour telephone call 7 to 10 days after the materials were received. To accommodate PAC members, calls were often scheduled for evenings or weekends, and frequently had to be rescheduled because of unexpected events (eg, additional work shifts or no childcare).

Each member of the Spanish-language PAC received 4 separate mailings and took part in 4 subsequent telephone interviews. The interviews were conducted by native Spanish speakers (2 at Kaiser Permanente Northwest, 2 at DH) who directly entered PAC members’ responses into the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database. The Spanish-language PAC coordinator selected the materials or portions of text for PAC review. We focused on instructions, common English terms without a clear Spanish translation (eg, “kit”), alternatives for terms not often used (eg, “blood relatives”), and suggestions to improve the readability and accessibility of materials. Feedback from the Spanish-language PAC included using a common expression “como echar un volado” (“like flipping a coin”) to describe the randomization process, and specifying earlier in the materials that the genetic test was a saliva test, not a blood draw. For each set of materials to be reviewed, the coordinator developed a semistructured interview guide with specific questions. Portions of text to be reviewed were numbered or highlighted to facilitate identification.

Evaluation results

The follow-up survey was administered by telephone by bilingual study staff who had not been previously involved with the Stakeholder Workgroup. PAC members were informed that their responses would be kept confidential. Evaluation interviews were completed by 16 of 17 PAC members. We were unable to reach 1 PAC member after 6 attempts.

Likert scale responses

Satisfaction, Patient Empowerment

Table 2 shows that PAC members were generally satisfied with their participation, with most choosing “Very satisfied” (6/7 in the English-language PAC, 6/9 in the Spanish-language PAC) or “Satisfied” (3/9 in the Spanish-language PAC).

Table 2:

Survey responses: assessing satisfaction and empowerment

| Survey Questions and Responses | ENG (N) | SPAN (N) | Example Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| How satisfied were you with your experience with the PAC? | |||

| Very satisfied | 6 | 6 | “I felt like I was doing something to help other people.” (E) “I’m super excited because I can give something to society … to the group that is doing this study!” (S) |

| Satisfied | 0 | 3 | “I felt they took our opinions seriously.” (S) |

| Neutral | 1 | 0 | |

| What did you think of the number of group meetings? | |||

| Just right | 4 | n/a | |

| Too few | 3 | ||

| What did you think of the number of phone interviews? | |||

| Just right | 6 | 8 | |

| Too few | 1 | 1 | |

| What do you think of the number of times we reached out to you? | |||

| Just right | 7 | n/a | |

| Would you work as a PAC member on a different study in the future? | |||

| Yes | 2 | 8 | “I would, to help people … so they can get more information about illnesses they may have.” (S) |

| No | 2 | 2 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 | 0 |

PAC, Patient Advisory Committee.

Nearly all participants considered that their number of telephone interviews were “Just right.” English-language PAC members were split in their assessment of the number of group meetings, with about half (4/7) stating they were “Just right” and the remaining 3 selecting “Too few.” Most (8/9) Spanish-language PAC members said they would choose to work in a PAC in the future; a minority (2/7) of English-language PAC members indicated they would do so.

Assessment of PCORI Engagement Principles

Table 3 indicates that most PAC members either strongly agreed (3/16) or agreed (7/16) with the statement “I was involved in deciding how and how often to work with the research team” (item assessing Reciprocal Relationships). However, 6 of 16 disagreed, explaining that they were “not involved in” determining the time, frequency, or nature of meetings or phone calls, and that “one can give their opinion, but it’s [the research team] who has the final say.” Nearly all PAC members strongly agreed or agreed with all items assessing Co-Learning. One member “neither agreed nor disagreed” with whether the study used PAC feedback and whether the study helped the participant understand the research process.

Table 3:

Survey responses: assessing reciprocal relationships and co-learning

| Survey Questions and Responses | ENG (N) | SPAN (N) | Example Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| I Was Involved in Deciding How and How Often to Work with Research Team | |||

| Strongly agree | 1 | 2 | “I wasn’t the one deciding when we talked. You guys set the times.” (S) |

| Agree | 2 | 5 | |

| Disagree | 4 | 2 | |

| In telephone interviews, I got to share my opinions about study materials. a | |||

| Strongly agree | 3 | 2 | |

| Agree | 4 | 7 | |

| In group meetings, I got to share my opinions about study materials | |||

| Strongly agree | 4 | n/a | |

| Agree | 3 | ||

| The study team used feedback from the PAC. a | |||

| Strongly agree | 3 | 2 | “The study already had materials that were almost finished, but they took our opinion into account.” (S) |

| Agree | 4 | 6 | |

| Neutral | 1 | “I don’t know if they changed materials based on my opinion.” (S) | |

| The study team helped me to understand the research process. | |||

| Strongly agree | 3 | 3 | “I never thought about genetics before, now I know that cousins are not considered close relatives in terms of illnesses.” (S) |

| Agree | 4 | 5 | |

| Neutral | 1 | ||

| The study team valued my opinion. a | |||

| Strongly agree | 6 | 5 | |

| Agree | 1 | 4 |

Indicates questions asked only to members of the English-language PAC. All other questions were asked to members of both PACS.

PAC, Patient Advisory Committee.

As Table 4 shows, all Spanish-language PAC members endorsed “Strongly agree” or “Agree” on all items assessing Partnership. Although English-language PAC members endorsed most items positively, 2 neither agreed nor disagreed as to whether PAC participation made the study more relevant to diverse patients, and 1 expressed not having had a good understanding of the work involved prior to it beginning. One PAC member noted having difficulties attending in-person or telephone meetings.

Table 4:

Survey responses: assessing partnership

| Survey Questions and Responses | ENG (N) | SPAN (N) | Example Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| I was paid in a fair way for the work I did. a | |||

| Strongly agree | 3 | 3 | “Sometimes you have to wait for that pay period … wait up to a month.” (E) |

| Agree | 4 | 6 | |

| It was easy for me to do the phone interviews. a | |||

| Strongly agree | 4 | 4 | |

| Agree | 2 | 0 | |

| Disagree | 1 | 5 | |

| It was easy for me to come to the group meetings. a | |||

| Strongly agree | 3 | n/a | “I’m not always able to drive because of my health, but if I couldn’t drive [study] would always help get me there.” (E) |

| Agree | 3 | ||

| Disagree | 1 | ||

| I had a good understanding of the work I was going to do when I agreed to be in the PAC. a | |||

| Strongly agree | 4 | 3 | |

| Agree | 2 | 6 | |

| Disagree | 1 | 0 | |

| What the CHARM team asked me to do was reasonable and thoughtful. | |||

| Strongly agree | 4 | 4 | |

| Agree | 3 | 5 | |

| The CHARM team showed a commitment to diversity. a | |||

| Strongly agree | 5 | 2 | |

| Agree | 2 | 7 | |

| The CHARM team showed a commitment to respecting my cultural background. a | |||

| Strongly agree | 3 | 3 | |

| Agree | 4 | 6 | |

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | |

| My work as a PAC member made the CHARM study more relevant to diverse patients. | |||

| Strongly agree | 2 | 2 | |

| Agree | 3 | 7 | |

| Neutral | 2 | 0 | |

| Do you think the PAC represented the diversity of Kaiser Permanente Northwest/DH organization? a | |||

| Yes | 7 | n/a | |

| No | 0 |

Indicates questions asked only to members of the English-language PAC. All other questions were asked to members of both PACS.

CHARM, Cancer Health Assessments Reaching Man; PAC, Patient Advisory Committee.

Table 5 shows that all PAC participants strongly agreed or agreed with the statements “I got the information I needed to understand and give feedback about the study” and “The study team was committed to open and honest communication.” Most PAC members (13/16) strongly agreed or agreed with “I felt included in decisions about the study.” However, 3 PAC members stated they did not know how the research team’s decisions were made or stated “I don’t think we [PAC members] were included in the decisions.”

Table 5:

Survey responses: assessing transparency, honesty, and trust

| Survey Questions and Responses | ENG (N) | SPAN (N) | Example Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| I felt included in the decisions about the CHARM study. | |||

| Strongly agree | 3 | 3 | “They were always focused on what I said, even details.…” (S) |

| Agree | 2 | 5 | |

| Neutral | 2 | 1 | “I honestly don’t know how they used my opinion.” (S) “Yes about the materials, but I don’t think we were included in general decisions.” (E) |

| I got the information that I needed to understand and give feedback about the CHARM study. | |||

| Strongly agree | 4 | 2 | |

| Agree | 3 | 7 | |

| The CHARM team was committed to open and honest communication. | |||

| Strongly agree | 4 | 3 | |

| Agree | 3 | 6 | |

| Disagree | 0 | 0 |

CHARM, Cancer Health Assessments Reaching Man.

Open-ended questions

PAC members were generally satisfied with the process. A few offered suggestions:

“I would have liked to walk through the whole process, from approach to [consent] signing, etc.”

All members of both PACs understood why the study sought their feedback, stating:

“[The study] want[s] people who will be participating to understand perfectly what they’re being asked.…” “To ensure that low-income and possibly low-education people can access medical care like those who are possibly more privileged.…” “I liked explaining how to make it easier, so others can understand.…”

PAC members expressed satisfaction with the way materials were made available, working by telephone, and the work itself. “My satisfaction came from feeling useful…”; “the study took our suggestions seriously—we were able to make contributions.” English-language PAC members appreciated the opportunity to “hear [feedback] from different aspects, different perspectives.” Nearly all participants expressed feeling valued and learning a great deal:

“My opinion did matter.… I felt valued in how to make research better and understandable to others who wouldn’t be ‘book-smart.’…”

Suggested improvements

PAC members suggested providing all the study information and documents in a binder from the beginning. Although most preferred paper copies of materials, some suggested providing materials online as well. Members of both groups reported problems receiving the materials by US Postal Service and suggested delivering materials by messenger service. PAC members suggested sending surveys via email, providing a video connection for meetings, and having a single staff member schedule meetings and calls. No improvement suggestions were offered regarding compensation.

Unexpected learning experiences for PAC members

When asked what surprised them, most PAC members stated learning “about the types of cancer we didn’t know [existed],” or “how cancer can affect different generations.” Several Spanish-language PAC members expressed surprise that their opinions were sought and noted this was a learning experience:

“I was surprised that [the study] would consider our opinion as important…”

“I learned the difference between just translating and translating to actually help people understand.…”

Patient involvement

Few PAC members expressed a negative view of research prior to participating, but all said their participation made them more interested in, and supportive of, research. All reported being more likely to recommend that family or friends participate in research.

“It is refreshing to see people going out of their way to make sure [African Americans] understand what they are consenting to….”

Discussion

The lack of diversity in genomic research impedes equitable care. Engaging patient stakeholders in genomic research can increase recruitment of underrepresented groups, make research more relevant to clinical care of diverse populations, improve the clarity and transparency of the consent process, 19 foster adoption of clinical findings, improve patients’ care experience and health outcomes, and increase the integration of research into real-world settings. 3,6 In a study aimed at reducing disparities in genomic care, we engaged stakeholders in intervention development and modified study materials based on their feedback and concerns regarding genetic testing.

Exit interviews suggested that nearly all PAC members felt satisfied and felt their tasks were not burdensome. Most believed their feedback was used, and most felt included in study decisions, but some said they did not know whether their opinions were used to modify materials or approaches. This suggests the need to explain to patient stakeholders the extent to which their feedback was used, and to inform them about the impact that other stakeholders, such as IRBs, have on decisions. 11 From this observation, we make the recommendation that future studies employing PACs communicate to PAC members regularly about how their feedback has been implemented by the study team.

We also learned valuable lessons about how to incorporate a patient engagement process. We did not anticipate the difficulty of coordinating the development of materials by various study workgroups. Some groups’ work was contingent on other groups, and presenting materials to the PACs in a coherent manner presented challenges. The simultaneous development of different study materials created document bottlenecks, with some workgroups competing for PAC time to assess their materials. The study also experienced challenges in allocating sufficient time for workgroups to respond to PAC feedback while balancing other study needs, particularly the need to submit materials for IRB approval. Additional time for expert workgroups to modify materials in response to PAC feedback, or the need for additional PAC review, created tension between workgroups vying for PAC time, and between workgroups and study leaders, as delays due to PAC-informed revisions impacted recruitment start-up. From these observations, we recommend that future studies build sufficient time for integration of PAC feedback and that study milestones reflect the need for lengthier start-up in studies that intend to rely on stakeholder feedback to inform the development of study materials. Creating the Spanish-language PAC required substantial time from Spanish-speaking staff, and addressing Spanish-language PAC needs, such as obtaining their feedback in individual interviews instead of group meetings, created logistical difficulties. For practical reasons, we limited the Spanish-language PAC feedback to specific wording and graphics. Although obtaining Spanish speakers’ feedback from the initial stages of study planning may result in more culturally centered study processes and possibly greater recruitment, this would add complexity to the development of materials and likely result in further delays in recruitment start-up.

Limitations

Although we attempted to recruit PAC members from diverse backgrounds, our members were not fully representative of the study sites. Thus, their feedback may not be generalizable.

Our interviews could have benefited from a deeper exploration of ambiguous responses. Although the interviewers assured PAC members that their names or other identifiable characteristics would not be revealed, because of the small PAC sizes, PAC members may have felt their responses might nevertheless identify them. Additionally, whether to avoid offending the study team, or reflective of self-affirmation, 20 PAC members may have been reluctant to offer critical feedback. An anonymous and more open-ended exit interview may have provided more opportunity for constructive criticism.

Conclusion

Our evaluation highlights the value of dedicating substantial resources to adapting materials and procedures through stakeholder engagement. Although that investment introduced complexity and time constraints during project start-up, adaptations to study materials and processes will contribute to robust recruitment and further study goals.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Jill Pope, Cassandra Angus, and Ana Reyes of the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research for valuable editing, administrative assistance, and contribution to data collection, respectively.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was funded as part of the Clinical Sequencing Evidence-Generating Research consortium funded by the National Genome Research Institute (2U01HG007292 Goddard & Wilfond Co-PI).

Conflicts of Interest: None declared

Author Contributions: Nangel M Lindberg, PhD, Kathleen F Mittendorf, PhD, Carmit McMullen, PhD, Katrina AB Goddard, PhD, Benjamin S Wilfond, MD, Alyssa Koomas, RD, Sonia Okuyama, MD, Kelly J Shipman, MS, and Devan M Duenas, MA participated in the study design and in acquisition of data. Nangel M Lindberg, PhD, Kathleen F Mittendorf, PhD, Devan M Duenas, MA, and Carmit McMullen, PhD, participated in data analyses, manuscript development, critical review, drafting, and submission of the final manuscript. All authors provided critical review of and have given final approval to the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- B-RST

Breast Cancer Genetics Referral Screening Tool

- CHARM

Cancer Health Assessments Reaching Many

- CSER

Clinical Sequencing Evidence-Generating Research

- DH

Denver Health

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- KPNW

Kaiser Permanente Northwest

- PAC

Patient Advisory Committee

- PCORI

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute

- PREMM

Prediction Model for gene Mutations

- REDCap

Research Electronic Data Capture

- SES

socioeconomic status

References

- 1.Forsythe LP, Carman KL, Szydlowski V, et al. Patient engagement In research: Early findings from the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(3):359–367. 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Concannon TW, Fuster M, Saunders T, et al. A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(12):1692–1701. 10.1007/s11606-014-2878-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraft SA, Cho MK, Gillespie K, et al. Beyond consent: Building trusting relationships with diverse populations in precision medicine research. Am J Bioeth. 2018;18(4):3–20. 10.1080/15265161.2018.1431322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pickard AS, Lee TA, Solem CT, Joo MJ, Schumock GT, Krishnan JA. Prioritizing comparative-effectiveness research topics via stakeholder involvement: An application in COPD. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90(6):888–892. 10.1038/clpt.2011.237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esmail LC, Roth J, Rangarao S, et al. Getting our priorities straight: A novel framework for stakeholder-informed prioritization of cancer genomics research. Genet Med. 2013;15(2):115–122. 10.1038/gim.2012.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esmail L, Moore E, Rein A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: Moving from theory to practice. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(2):133–145. 10.2217/cer.14.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.PCORI. PCORI engagement rubric. 2014. Accessed 2 February 2022. http://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/Engagement-Rubric.pdf

- 8.Research CCSE-G. Clinical Sequencing Evidence-Generating Research(CSER) consortium. March 2019. Accessed https://cser-consortium.org.

- 9.Amendola LM, Berg JS, Horowitz CR, et al. The clinical sequencing evidence-generating research consortium: Integrating genomic sequencing in diverse and medically underserved populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;103(3):319–327. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clinical Sequencing Evidence-Generating Research (CSER). CHARM (Cancer Health Assessments Reaching Many). 2019. Accessed https://cser-consortium.org/projects/155.

- 11.Kraft SA, McMullen C, Lindberg NM, et al. Integrating stakeholder feedback in translational genomics research: An ethnographic analysis of a study protocol’s evolution. Genet Med. 2020;22(6):1094–1101. 10.1038/s41436-020-0763-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Health Center Program. 2017 Denver health & hospital authority health center program awardee data. 2019. Accessed 2 February 2022. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds2017/datacenter.aspx?q=d&bid=080060&state=CO&year=2017

- 13.Shavers VL. Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(9):1013–1023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng TL, Goodman E, Committee on Pediatric Research . Race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status in research on child health. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e225-37. 10.1542/peds.2014-3109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kastrinos F, Uno H, Ukaegbu C, et al. Development and validation of the PREMM5 model for comprehensive risk assessment of lynch syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(19):2165–2172. 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.6120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellcross C, Hermstad A, Tallo C, Stanislaw C. Validation of version 3.0 of the Breast Cancer Genetics Referral Screening Tool (B-RST). Genet Med. 2019;21(1):181–184. 10.1038/s41436-018-0020-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skinner HG, Calancie L, Vu MB, et al. Using community-based participatory research principles to develop more understandable recruitment and informed consent documents in genomic research. PLoS One. 2015;10(5). 10.1371/journal.pone.0125466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Festinger L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]