Abstract

Introduction

Essential tremor (ET) is a common movement disorder in the elderly. Bilateral postural tremor usually involves the hands and forearms; the primary diagnostic criteria can be with or without a kinetic tremor. Anticonvulsants are frequently prescribed as a primary medication, and botulinum toxin and deep brain stimulation as secondary options. In this case report, a patient with ET received medical painting therapy guided by the principles of anthroposophy and the work of Liane Collot d´Herbois.

Case Presentation

A 78-year-old woman presented ET, depression and bipolar symptoms. Additionally, she reported insomnia, constipation, lumbar pain, and sciatic pain. Current medications included lithium carbonate, folic acid, levothyroxine, and zinc, and she had refused to take propranolol for her ET. She agreed to begin medical painting therapy. Over 5 months, she had 16 sessions of medical painting therapy, carried out in 2 stages. The first stage consisted of 6 free painting sessions for patient evaluation, followed by the second stage of 10 therapeutic sessions.

Conclusion

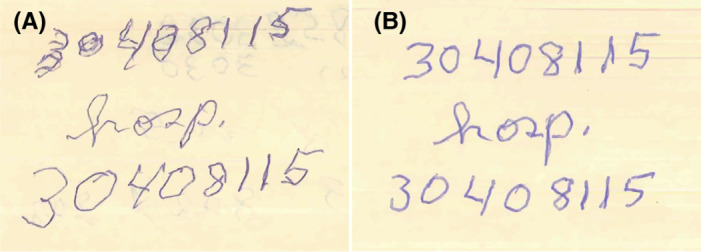

The patient reported an increased quality of life (including emotional aspects) and a decrease in her ET, as evidenced by the patient’s handwriting. Further research is needed to understand the strengths and limitations of this therapy for ET and related conditions.

Keywords: essential tremor, Liane Collot d’Herbois, anthroposophical medicine, integrative medicine, medical painting therapy, case reports

Introduction

Essential tremor (ET) is the most common movement disorder worldwide. Annually, 23.7 of 100,000 people are affected, and its incidence increases with age.1 In Brazil more than 28 million people are currently over 60 years old, representing 13% of its population; Brazil’s elderly population in 2060 is predicted to reach c 25,50%. .2 Presumably, the number of patients diagnosed with ET disorder will increase as well.

ET is characterized by a postural and kinetic tremor diagnosed through clinical examinations, with 90% of cases showing tremors in the upper extremities and about 10% in the lower limbs.3 Patients struggle to live a normal life, with simple actions such as eating, writing, or walking becoming increasingly difficult. Studies of ET have also identified non-motor symptoms such as a dominant and centralizing personality, anxiety, social phobias, depression, low self-esteem, and functional deficits.2

The anticonvulsant primidone is the primary medication recommended for ET. Botulinum toxin and deep brain stimulation are secondary treatment possibilities.4

This case report, following the CARE guidelines,5 was presented as a poster at the World Congress Integrative Medicine and Health, May 3–5, 2017, in Berlin, Germany.

Clinical Case

Patient information

A 78-year-old woman patient, a widow and mother of 2 daughters who was in mourning for the death of her eldest daughter from cancer, was diagnosed with ET (Table 1). She had a falling accident that she linked to her tremor. She did not want to leave her house anymore, began to isolate herself, and behaved aggressively in family and social situations, which adversely affected her quality of life.

Table 1:

Timeline

|

Relevant medical history and interventions

A 78-year-old woman was diagnosed with essential tremor. Observed clinical signs included postural and kinetic tremor, bilateral in the arms and hands. The patient complained of insecurity when walking and difficulties with daily activities. The patient was in mourning from her daughter’s death and worn out from accompanying her daughter through a long and arduous process of fighting cancer. | |||

| Time | Symptoms | Diagnosis | Treatment |

| 2009 | Tremors in arms and hands | Patient and family observation | |

| Jul 2015 | Search of diagnostics and treatment for essential tremor symptoms | Clinical examination | Propanolol (patient refuses to take) |

| Relevant medical history and interventions | |||

| 1996 —2016 | Anthroposophical psychiatric medical treatment for depression and bipolar diseases | Clinical examination | Lithium carbonate (300 mg), 3 times per day |

| Since 1996 | Constipation, lumbar sciatic pain, and insomnia as chronic disorders | Medical history | Dexa-citoneurin (injectable) |

| Jul 20, 2015 | Patient’s daughter´s death | Patient reported | Levothyroxine, folic acid |

| Jul 2, 2018 | Lithium-level monitoring | 1,43 mEq/L | Reduction from 3 to 2 lithium carbonate pills per day |

| Therapeutic process | |||

| Nov 25, 2015 | Start of art therapy | Patient dozed off on the way home | First charcoal work |

| Sep 25, 2015 | Third meeting | Signs of more vitality evident | Third charcoal work |

| Jan 13, 2016 | Sixth meeting | Patient reports no constipation, decreased insomnia, better sleep quality | Third color painting |

| Mar 3, 2016 | Last meeting | Tremor symptoms decrease markedly | Finished painting (Figure 3) |

| Jun 2016 | Occasional meetings between therapist and patient | Patient holds cup of coffee without any tremor | |

| Sep 2020 | Patient became 83 years old | Daughter reports that her mother is feeling well | |

Clinical findings

The patient’s chief complaint was insecurity when walking. The initial ET symptoms were tremors in her forearms, which progressively worsened until they affected her lower limbs, limiting her activities of daily living. She had a 20-year history of medical treatment for symptoms related to depression and bipolar disorder, and also reported insomnia, constipation, lumbar pain, and sciatic pain. After several clinical visits, which included laboratory and radiological evaluations, Parkinson’s disease was excluded. The patient refused treatment with propranolol and started treatment with medical painting therapy and acupuncture.

Medical painting therapy

The patient had 16 sessions over 5 months, which were divided into 2 stages. The first stage consisted of 6 free art work sessions (3 in charcoal and 3 in watercolor) for making an art diagnosis of the patient, which guided the second stage of therapy. In addition to medical painting therapy, the patient continued her medications: lithium carbonate, folic acid, levothyroxine, and zinc. She also tried acupuncture applications but elected not to continue with this therapy.

| Sidebar: Liane Collot d`Herbois’s medical painting therapy |

| The medical painting therapy proposed by Liane Collot d`Herbois is grounded on anthroposophy, which was developed by Rudolf Steiner. The human being is understood as a microcosmic expression of the macrocosm (the universe), and as a totality composed of body, soul, and spirit.6 Liane Collot d’Herbois based the medical painting therapy on the principles of light, color, and darkness. She believed that the principles of evolution are light and darkness, which are polar forces forming the constitution of the human organism; and that the light forces are present in the upper pole of the human organism and reflect the nervous system. Darkness is present in the lower pole of the human organism and expresses the metabolic-limb system, which is characterized by metabolism and movement rather than a specific organ system.7 She saw these forces in connection with tendencies of the human organism in health and disease: the tendency to sclerosis or inflammation; the disposition for contraction, hardness, and expansion; for neurasthenia or hysteria; and the organism’s propensity to generate catabolic or anabolic forces.8,9

The therapy is a way that both principles—light and darkness—meet harmoniously. When this meeting is healthy, atmosphere, space, and movement are created. By promoting these elements artistically, the patient mobilizes inner resources. When painting according to these laws and following the quality of each principle and the encounters between light and darkness, a dynamic of colors is printed. Each color presents itself in a specific place, with different movements, qualities, and features. Liane Collot d`Herbois presumed that by joining those elements in their proper qualities, the patient stimulates better functioning of all systems, including that of circulation and breathing.10 The first works, in charcoal, are believed to indicate the spiritual, soul, and physical levels of a human. These 3 levels are associated with qualities of consciousness, thinking, and the nervous system. The darkness is a reflection of the connection of the patient to the earth, the quality of the will, the metabolic-limb system, and the interaction between light and darkness.10,11 The later works, watercolor paintings, are associated with the functioning of the soul virtues and form the basis of the functioning of the organic process, including the organs.10,11 |

Diagnosis

The patient’s charcoal work and painting watercolor painting were interpreted using the principles of Liane Collot d`Herbois to reach a diagnosis (see Sidebar: Liane Collot d`Herbois’s medical painting therapy). In Figure 1 (charcoal), elements in the lower part of the picture indicate opaque, diffuse, and dispersive qualities of the patient, and the darkness at the top represents fragility without warmth; note the split between darkness in the upper and light in the lower part of the work. In Figure 2 (watercolor), pale colors and layers form lines and a division separating upper and lower, as well as the right and left sections.

Figure 1:

An example of the 3 free works on charcoal upon which the diagnosis was based. Technique: light and dark; material: Fabriano paper and charcoal.

Figure 2:

An example of the patient’s 3 free paintings in watercolor upon which the diagnosis was based. Technique: watercolor in wet paper; material: newsprint (paper) and Winsor & Newton watercolor paints.

Treatment

The therapeutic goal of medical painting therapy is to guide the patient using the principles of light, color, and darkness.10 In this case, because of the patient’s fragile nature, the therapy began with an emphasis on the principles of darkness, which are believed to help achieve warmth. By achieving warmth, the line patterns were transformed, widening layers and creating a color atmosphere, which is one of the elements aimed at through this art therapy.

The main colors to guide the process were chosen by the therapist: viridian green and magenta. The viridian green with its essence was felt to be able to bring together soul and spiritual qualities, reestablish the qualities of light, and strengthen the consciousness. This was important to integrate all parts in the painting (Figure 2). Magenta was used as a healing color to bring warmth, vitality, and moisture to the entire organism (Figure 3).10

Figure 3:

Therapeutic painting performed by the patient at the end of the process. Technique: wet paper to wet watercolor; material: Courrant paper, Winsor & Newton watercolor paints, Schmink and Old Holland watercolor paints.

Treatment comments

Empirical observations guided the therapy during the treatments; these included the patient’s artistic achievements, patient reports to the therapist, and the therapist’s observations. For example, during the first session the patient yawned continuously and reported dozing off in her car on the way home. After the first sessions, she showed signs of more vitality and had more color in her cheeks. The patient was often ambivalent about coming to therapy. But once she began painting, she seemed to experience pleasure and joy. She demonstrated involvement and seriousness, overcame artistic difficulties, and appeared surprised by her goals.

Results

After beginning medical painting therapy, the patient demonstrated more vitality and reported less constipation and insomnia. When the patient, through movement, began to portray the proposed principles and artistic elements of medical painting therapy internally, her thinking, feeling, and will improved. She appeared to become more alive and was able to transform ideas into action. From an artistic point of view the lines were expanded, bringing a greater sense of harmony. Her painting became more integrated, with a greater sense of balance (Figure 3).

Her handwriting improved, and she could sign documents and bank checks (Figure 4).

Figure 4:

Handwriting (A) before and (B) after the therapeutic process.

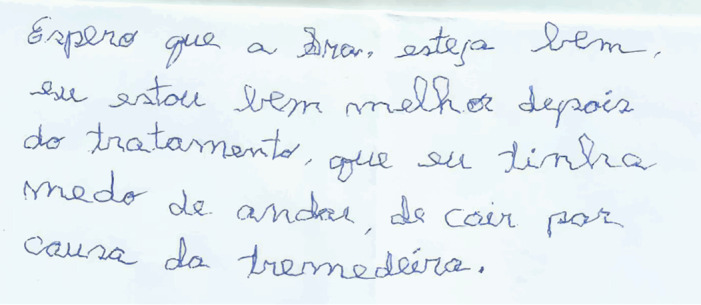

The patient’s self-report (Figure 5) and her daughter also reported that the patient’s moods became regular, without signs of depression or aggression in interpersonal relationships. The patient was happier, played with her grandchildren (cards and bingo), and maintained a healthy relationship with family members. In her daughter’s words: “She is firmer with her legs and confident with what she wants. She said that one day she wants to live to reach 100 years old.”

Figure 5:

Patient self-report. Translation: I hope Mrs. is fine [the therapist]. I am better after the treatment. Before, I was afraid of walking and falling down because of the tremor.

Three months after the end of the therapy, the therapist and patient meet occasionally in a social event, where the patient was observed steadily holding a full cup of coffee without any tremor.

Discussion

ET has been studied to understand its epidemiology, pathophysiology, viable treatments, and contraindications. ET causes inability and difficulties to complete simple or specifics tasks.1,3,4,12,13 Propranolol or primidone are used to control the symptoms of ET. Surgical treatment with deep brain stimulation is another treatment option for ET, despite its known adverse effects.1,3 Occupational therapists employ a variety of approaches, adapting tools and developing techniques to improve convenience and ease the lives of these patients.14 The painter Erich Otto Blaich showed that ET could be a special quality of patients, which leads to interesting effects in their paintings.15

The scientific literature points out the relationship between psychiatric illnesses associated with ET disorder such as depression and anxiety, and raises questions as to whether these are primary or secondary to the tremor.1,3,16 One study showed that depressive elderly had a reduction in depression-scale scores after an art therapy intervention.17 Studies developing art therapy for Parkinson’s disease patients demonstrated improvements in motor function and well-being.18,19 The epidemiology and clinical features of Parkinson’s disease and ET are different,20 yet the fact that art therapy can increase the quality of life of patients with these pathologies is hopeful.

At the beginning of the process, the patient was not secure to go out on the street and feared falling because of the tremor, progressively limiting her tasks of daily living. Emotionally she showed signs of depression and bipolar behavior. Throughout the art-therapy process and into the present, the patient presented behavioral changes that have resulted in a better quality of life, as reported in this case. It is presumed that medical painting therapy played a role in the improvement of the complaints and symptoms, and it should be considered as possible treatment for elderly people with ET.1,21

The strengths of this case demonstrate the potential of innovative medical art therapy in an individual patient. These changes appeared to happen because this methodology linked making art with changes in organic patterns and processes related to the physical body, as well as emotional and spiritual aspects. The limitations of this case are that the findings are based on empirical evidence from one patient only and that multiple interventions occurred simultaneously. Further investigations will study medical painting therapy as a potential methodology for ET and other pathologies.

Conclusion

In this case, medical painting therapy appeared to decrease the symptoms of ET and other symptoms, and it improved this patient’s quality of life. The patient’s self-report, her daughter’s comment, and observations of the medical painting therapist suggest that it may be a useful tool in treating similar patients suffering from ET.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nilo Gardin, Paula Franciulli, and Elaine Zanaroti for their critical review of manuscript drafts. The authors acknowledge the Emerald Foundation, disseminator of the principles of medical painting therapy.

Footnotes

Funding: The author received research funding from Instituto Internacional Ita Wegman and Instituto Mahle, São Paulo, Brazil.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no known conflicts of interests.

Consent: Informed consent was received from the case patient.

Author Contributions: Monica Elisabeth Winnubst, participated in the study design, guided the therapeutic process, obtained and analyzed data, and drafted and submitted the final manuscript. Ricardo José de Almeida Leme MD, PhD, participated in analysis of data and in the critical review. All authors have given final approval to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Zesiewicz TA, Chari A, Jahan I, Miller AM, Sullivan KL. Overview of essential tremor. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6:401–408. 10.2147/ndt.s4795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agência de Notícias [Internet], Número de idosos cresce 18% em 5 anos e ultrapassa 30 milhões em 2017 . Agência de Notícias - IBGE. 2018 [citado 20 de maio de 2022]. Accessed https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-noticias/2012-agencia-de-noticias/noticias/20980-numero-de-idosos-cresce-18-em-5-anos-e-ultrapassa-30-milhoes-em-2017.

- 3.Elble R, Deuschl G. Milestones in tremor research. Mov Disord. 2011;26(6):1096–1105. 10.1002/mds.23579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbosa ER, Ferraz HB, Tumas V, et al. Transtornos do movimento, diagnóstico e tratamento. Omnifarma. 2013;2:45–47. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riley DS, Barber MS, Kienle GS, et al. CARE guidelines for case reports: Explanation and elaboration document. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:218–235. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steiner RS. A ciência oculta. São Paulo. E Antroposofica. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girke M. Medicina interna. Fundamentos e conceitos terapêuticos da medicina antroposofica. São Paulo. João de Barro Ed. 2014;1:25–27. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bott V. Anthroposophical Medicine: An Extension of the Art of Healing. 3rd ed. Associação Beneficente Tobias; 1991:31–66. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Introduction [Internet]. IVAA. [citado 20 de maio de 2022]. Accessed https://www.ivaa.info/anthroposophic-medicine/introduction/.

- 10.D`Herbois LC. Light, Darkness and Color in Painting Therapy. 2nd ed. Floris Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernard C, Mager J. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Elements in Light-Darkness-Color: Research on Different Types of Depressio. 1st ed. Rudolf Steiner College; 1998:37–48. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borges V, Ferraz HB. Tremors. Revista Neurociências. 2006;14(1):43–47. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louis ED, Ottman R, Hauser WA. How common is the most common adult movement disorder? Estimates of the prevalence of essential tremor throughout the world. Mov Disord. 1998;13(1):5–10. 10.1002/mds.870130105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howard B . Strategies and therapies for combating essential tremor. Brain&Life. Accessed February/March 2019. https://www.brainandlife.org/articles/essential-tremor-cant-be-cured-yet-but-therapies-and-compensating

- 15.Andrade J. Erich Otto Blaich. São Paulo: Person; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Louis ED. Essential tremor as a neuropsychiatric disorder. J Neurol Sci. 2010;289(1–2):144–148. 10.1016/j.jns.2009.08.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciasca Eliana C. Art therapy in the health area with a focus on Alzheimer’s disease and depression in elderly. Revista de Arteterapia da AATESP. 2018;9(1):16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cucca A, Di Rocco A, Acosta I, et al. Art therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2021;84:148–154. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2021.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schofield SJ. Group Art Therapy for People with Parkinson’s. University of Manchester; 2018:362–363. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon K-Y, Lee HM, Lee S-M, Kang SH, Koh S-B. Comparison of motor and non-motor features between essential tremor and tremor dominant Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2016;361:34–38. 10.1016/j.jns.2015.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosa AR, Flávio K, Renata O, Airton S, Barros HMT. Monitoring the compliance to lithium treatment. Rev Psiquiatr Clin. 2006;33(5). 10.1590/S0101-60832006000500005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]