Abstract

Introduction

Although cancer most directly affects the patient, its impact is also widely recognized to extend to those who are caring for the patient. Cancer patient caregivers endure psychological distress, have high levels of depression, and report isolation and strain. Research on targeted caregiver interventions is limited. This case report examines the use of health and wellness coaching (HWC) with a caregiver of a patient with neuroendocrine tumors, a rare, insidious type of cancer.

Case Presentation

We present the first known case report on using HWC with a 44-year-old woman adult cancer patient caregiver who was caring for a patient with neuroendocrine tumors. The patient had a chronically elevated body mass index, cholesterol, and stage 2 hypertension. Her primary care physician had prescribed weight loss medication (naltrexone/bupropion), which the patient hesitated to take and wanted to try HWC instead. The 10-session intervention targeted multiple components of health, including blood pressure, body mass index, cholesterol, weight loss, stress management, relationship success, and vocational progress. Outcomes were followed over a 1-year period.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates multiple unique aspects of the HWC process that support successful, sustainable behavioral change. The case patient’s success suggests HWC may be effective in supporting beneficial physical and psychosocial outcomes with an adult cancer caregiver and should be considered a viable option for promoting health in caregivers.

Keywords: health coaching, neuroendocrine tumors (NETS), caregiver, cancer caregiving, caregiver support, self-care, case report

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) arise from neuroendocrine cells in the body and are a diverse group of malignancies. Although NETs are a rare type of cancer, the incidence and prevalence are rising due to increased early-stage detection and improved survival. 1 Although the effects of cancer most directly affect the patient, its impact is also widely recognized to extend to the relatives or friends who are caring for the cancer patient (caregivers). 2–4 Caregivers of cancer patients endure psychological distress; compared to the adult with cancer, caregivers report levels of depressive symptoms similar to or even greater. 2 Four in 10 cancer caregivers want more help to manage their own emotional and physical stress, 5 and many caregivers struggle with isolation and strain. 6 Although there are multiple interventions targeted for cancer caregivers, there are few targeted specifically for NETs caregivers, who often care for their loved one for a prolonged period of time. Health and wellness coaching (HWC) may serve this population well.

As a rare and insidious disease, a NET affects both patients and caregivers in unique ways. Although NET patients live longer than other cancer patients, they report an equally poor health-related quality of life. 7 Sixty percent of patients report that living with NETs substantially affects their emotional health. Further, there is a substantial effect on the emotional health of their caregivers. Almost half (48%) report the emotional health of family and friends is negatively affected and 34% report their relationships with family and friends were impacted. 8 This highlights the psychosocial impact of cancer on the caregiver and the need to attend to caregiver health and well-being. Caregiving for a NET patient is particularly challenging because of the unusual difficulty in diagnosing and treating the condition, which requires a very individualized approach, and the slow-growing nature of NETs, which means patients with NETs can live with cancer for years or decades.

The limited research on interventions for cancer caregivers focuses on problem-solving, education, communication, and mindfulness. 9,10 To our knowledge, there are no existing studies on NET caregivers, this being the first. This case report examines the use of HWC with a caregiver of a NET patient. Defined as a patient-centered approach involving patient education, goal-directed health behavior change techniques, and an interpersonal coach–patient relationship, HWC elicits a patient’s own motivations for change. 11 In randomized, controlled trials of cancer survivors, HWC improves quality of life and psychological outcomes 12–14 as well as nutrition variables, exercise behavior, and weight control. 12,15 In randomized, controlled trials of patients with active cancer, HWC has enhanced psychological and quality-of-life indices, 16,17 communication regarding pain control, 16,17 and pain interference. 17 Caregivers can have myriad health issues and, fortunately, HWC can improve a variety of behavioral concerns (eg, weight, physical activity) and enhance physical and mental health in a number of chronic diseases. 18,19 This case report illustrates the potential value of HWC for a caregiver population, offering a supportive patient-centered approach to empower the NET caregiver to change behavior, ease psychosocial distress, and increase well-being. HWC could be evaluated for use with all cancer caregivers, particularly those whose family or friends are living with such a difficult disease as NET.

Methods

This case report uses the methods described in the internationally developed CARE guidelines 20 , created to increase the accuracy, transparency, and usefulness of case reports. It provides data from the patient of a national board-certified health and wellness coach, LH. The coach completed the Vanderbilt Health Coaching Program, which included 135 hours of continuing education and mentoring practices with patients over a minimum of 14 months. All coaching sessions took place over the telephone, which is standard practice in the field of HWC. All patient data was collected at the coach point of care and confirmed through patient self-reporting, medical data from the patient’s physician, and review of the coach’s notes. This study is based on the patient’s point of view and interpretation. This study was exempted by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this case report and her perspective. The patient has reviewed and approved all content.

Presenting concerns

A 44-year-old divorced woman (HD) providing care for her mother with cancer was referred to a trained national board-certified health and wellness coach (LH) by the Los Angeles Carcinoid Neuroendocrine Tumor Society, a national patient advocacy organization that provides support and education for those with neuroendocrine cancer and their loved ones. HD stated she had neglected her health throughout caregiving and had “concerning issues” in multiple areas of her life. The patient had a chronically elevated body mass index, high cholesterol, and stage 2 hypertension. Her primary care physician (PCP) had prescribed weight loss medication (naltrexone/bupropion), which as a side effect could also reduce anxiety. She was hesitant to take it and wanted to see if HWC would help her address her health issues so that she did not have to take the medication.

History and diagnosis

The patient’s mother was diagnosed with NET in 2012 and HD became her medical advocate. In 2017, HD became her primary caregiver as well. As a caregiver, she said she prioritized her mother’s health while overlooking her own. In 2015, HD was diagnosed with elevated cholesterol; in 2017, she was overweight and had high blood pressure. When HD presented for coaching in 2019, her body mass index was 38 and she was categorized as obese. She was under the care of her PCP, but had not started the prescribed medication. She valued an interpersonal approach; she had previously worked well with a therapist who committed suicide. Although she tried another therapist, she said she did not feel a strong connection with her. She had also tried hypnosis, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, and emotional freedom technique. She had worked with a health coach through her insurance company, but had not found it helpful due to the online nature of interactions and lack of personalization. She occasionally walked for exercise, but reported little motivation, and refrained from social activities due to discomfort over her high weight and lack of financial resources. HD had supportive friends and family, but did not feel comfortable confiding in them about her stress and other issues. She had been unemployed since 2017, was too financially restricted to join a gym or exercise class, and did not see a viable path for the career she sought. She felt like she was “stuck” and “spinning her wheels going nowhere.” Additionally, the patient had trichotillomania (hair pulling) since she was 8 years old. She came to health coaching in order to establish daily habits to support her health and self-care (eg, exercise, sleep, stress reduction).

Intervention

When originally referred, the patient was offered 8 sessions of HWC free of charge (funded by the Los Angeles Carcinoid Neuroendocrine Tumor Society) and an additional 2 subsidized sessions at a fee of $20 each. She was also provided a brief introduction to HWC, with information about what to expect. The patient was informed about what HWC is, the roles of the health coach and patient, the logistics of the sessions, and given preparation materials for the calls (eg, Health Coaching Agreement, Wheel of Health (WOH), and a health coaching intake form). HD completed an intake form and WOH self-assessment prior to the first call. This initial telephone call (60 minutes in length) allowed her to explore and assess her health perceptions and goals. This self-assessment created the foundation for the personalization of the coaching process. In total, the patient received 10 sessions (60–75 minutes in length) over the telephone over 7 months. See Figure 1 for the Vanderbilt Health Coaching Program WOH tool that was used for self-assessment.

Figure 1:

Vanderbilt Health Coaching Program Wheel of Health. © 2015 Vanderbilt University Osher Center for Integrative Medicine. Used with permission.

Self-Discovery

Across the course of coaching, HD was led through a process of self-discovery to create her own optimal vision of health. With the use of guided imagery and the WOH to compare her optimal health to her current health in multiple domains of her life, the coach and patient explored areas of discrepancy for readiness to change. HD prioritized the creation of daily rhythm and balance as the place to begin making small changes. By responding to open-ended questions about what behavioral changes would be most important to her and why, she was encouraged to make skillful decisions congruent with her individual values, long-term vision, and sense of purpose. Strong theoretical support demonstrates that patients are more likely to create self-sustaining agendas for themselves when they have considered the greater perspectives of their lives and make their goals concordant with their values. 21–26

By committing to small action steps at each session, HD moved toward a self-identified Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Realistic, and Time-Bound (SMART) health goal, as noted in Table 1. Multiple action steps led her toward her goal. In 1 of the action steps, HD actively researched the medication suggested by her doctor and decided not to take it. Her desired outcomes were to feel connected to her physical body and to feel rested, rejuvenated, and motivated with the ultimate outcomes to be healthier (eg, lower blood pressure, lower cholesterol, less stress, progression in career) and achieve weight loss. See Table 1.

Table 1:

Sample SMART goals and action steps

| SMART is a goal-setting approach that consists of Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Realistic, and Time-Bound goals and action steps. SMART action steps are small steps taken on a weekly basis to achieve a SMART goal. This approach is used to facilitate behavioral change and predicts long-term engagement and success. SMART GOAL CREATED BY HD: By the end of 6 mo, I will establish a daily routine that includes a consistent bedtime of 11 pm, consistent wake time of 7 am, 8 min of prayer/reflection/setting intentions, 30 min of exercise, and time each morning to plan the day. SAMPLE ACTION STEPS CREATED BY HD:

|

The HWC process itself elicits intrinsic motivation to make needed changes. Specifically, the process entails exploring what the patient values most and how to link those values and sense of purpose to the health behaviors needed. 27–29

Gaining traction

HWC sessions began with a mindful moment and a brief check-in, during which HD reported on the specific action step(s) she committed to during the preceding session(s). She was asked to note success first, then to problem-solve and explore solutions for upcoming obstacles. More importantly, she was repeatedly asked what she learned from failed problem-solving attempts, which were nonjudgmentally framed as “experiments” necessary for true learning. Nonjudgmental framing was essential to maintain rapport and to encourage HD to experiment with solutions without fear of failure. As she was ready to take them on, HD then committed to new action steps toward her goals to be accomplished before the next call. She stated that the SMART action step approach built momentum and confidence and enabled her to approach larger goals that had previously seemed insurmountable.

The session then moved into a discussion of the patient’s choice, with the explicit aim of exploring what topic was personally important and how she wanted the topic to evolve. The exploration led to setting next steps to continue moving toward her desired long-term goal. Multiple communication skills are used in different portions of the session, and are beyond the scope of this report.

Intervention tolerability and unexpected events

The intervention was well-tolerated and highly appreciated. No adverse events were reported.

Follow-Up and Outcomes

Short term

The patient received multiple benefits from HWC. In her final session, she reported success in accomplishing her most important long-term goal: establishing a daily rhythm and balance that prioritized herself and her health. Her new routine included a consistent bedtime, consistent wake time, prayer/reflection/setting intentions, at least 30 minutes of exercise most days, and time each morning to plan the day. To support her desired outcome for weight loss, HD incorporated intermittent fasting 12–16 hours daily. Prior to the start of HWC, her PCP had recommended medication (naltrexone/bupropion) for weight loss. By the end of her coaching sessions, HD no longer had a need to take medications as a result of the behavioral changes she accomplished through the coaching process. In addition, HD said coaching substantially reduced her anxiety by showing her how to take small steps, gain traction and momentum, and track progress. After being unemployed and “feeling stuck,” she enrolled in a certification program through University of California, Berkeley to begin to pursue her desired career path. She developed an ability to self-reflect and reported positive shifts in how she saw herself and her relationships. She said she felt optimistic.

Long term

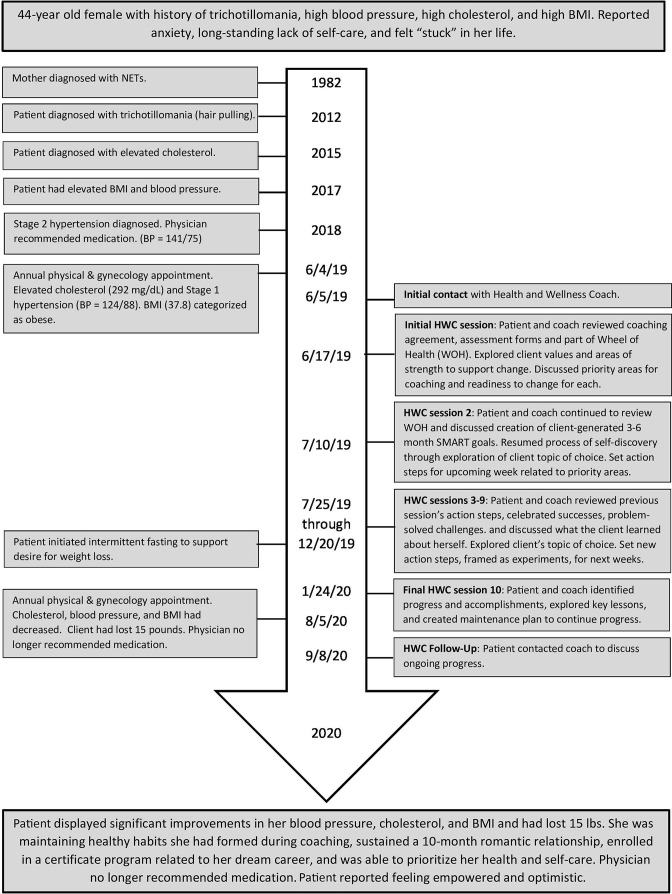

One year after the initial session, HD initiated contact with the health coach and notified her of the results from a recent annual physical with her PCP. HD reported substantial improvements in her blood pressure, cholesterol, and body mass index. She was maintaining healthy habits she had formed during coaching (eg, daily rhythm and balance, adequate sleep, regular exercise, intermittent fasting) and indicated a decreased stress level and improvement with trichotillomania. She stated that for the first time in a while, she felt connected to her physical body. HD reported more self-compassion and increased confidence. The patient noted that she successfully began and sustained a 10-month romantic relationship, which she saw as substantial progress with her emotional, psychosocial, and relational well-being, including the ability to be vulnerable. HD said she felt empowered, in control, and newly able to prioritize her health and self-care. She stated HWC was the catalyst for change in all areas of her life, demonstrating the value of HWC for this patient. See Figure 2 for a full timeline of the case. The patient perspective is in the Sidebar. See Table 2 for a detailed description of physical outcomes and Table 3 for psychosocial and other outcomes.

Figure 2:

Timeline of the case. NETs = neuroendocrine tumors; HWC = health and wellness coaching; BMI = body mass index; BP = blood pressure.

Table 2:

Physical outcomes

| Medical measurements | Pre-Health coaching (June 2019) |

Post-Health coaching (August 2020) |

Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass index | 38 | 35.58 | ↓ 2.42 |

| Weight | 229 lbs | 214 lbs | ↓ 15 lbs |

| Blood pressure | 124/88 mmHg | 118/80 mmHg | ↓ 6/8 mmHg |

| Total cholesterol | 292 mg/dL | 234 mg/dL | ↓ 58 mg/dL |

| Triglycerides | 194 mg/dL | 164 mg/dL | ↓ 30 mg/dL |

| LDL | 186 mg/dL | 139 mg/dL | ↓ 47 mg/dL |

LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Table 3:

Psychosocial and other coaching outcomes reported by the patient

| Health domain | Outcome description |

|---|---|

| Daily rhythm and balance (daily routine) |

Established and maintained a daily rhythm and balance that prioritized herself and her health. Her new routine included a consistent bedtime, consistent wake time, meditation, movement, and time each morning to plan the day. |

| Mind–Body connection (interaction between mind, body, and spirit) |

Stress level decreased from 7.5 to 6 on a 10-point scale. Managing stress through self-compassion and optimism rather than through food or television. |

| Reported less anxiety. Sense of fear and panic decreased. Developed an increased sense of control over life. | |

| Improvement in trichotillomania (hair pulling). | |

| Personal growth and development | Self-worth increased. Prioritized making time for own self-care and health, which was new. |

| Self-compassion and confidence increased. | |

| Allowed herself permission to fail and to be a “work in progress” as a person. | |

| Relationships and community | Engaged in a successful 10-mo romantic relationship after not having one for 3.5 y. For the first time in decades, was able to be honest, vulnerable, and her authentic self within a relationship. |

| Put boundaries in place in relationships rather than always putting the needs of others before her own. | |

| Spirit and soul (including meaningful work) | Enrolled in a certification program related to her dream career path and no longer felt “stuck.” |

| Began to pray regularly and incorporate spiritual material (podcasts, books, blogs, etc). | |

| Movement, exercise, and play | Exercised 30–45 min 5–6 d/wk. Felt connected to her own body, whereas before she was disconnected. |

| Patient Perspective |

|---|

|

I had been caretaking for so long I’d forgotten how to prioritize myself and my life … I felt very disconnected from my identity, my physical being, and was in the midst of a very transitional period of my life. The stress and strain in advocating for my mother during her illness had taken a significant toll … I was recovering from burn-out and it was negatively impacting my overall physical health …

[It] was so refreshing and empowering to be guided by someone optimistic, who showed me progress where I did not see any, and answers I did not realize I arrived at yet. And during the sessions/overall process my mind-set was shifting, I was learning to use my energy and efforts towards my wellness, not just others. Coaching reminded me that I am holding the reins in my life and although I cannot magically make things happen, I can steer and take ownership of my actions/goals in my control. One step at a time, one slight turn this way or that will lead to larger, tangible changes/destination. Before coaching I felt like I was not even on the horse and now I feel like I’m at a comfortable trot or canter, working up to a gallop! |

Discussion

This is the first case study reporting on the use of HWC with a cancer patient caregiver. It illustrates the potential value of HWC in helping caregivers, who are by necessity focused on the health of others, to also invest in their own health and well-being. The case demonstrates multiple strengths of the HWC process and details numerous successful outcomes that were achieved by an individual caring for her mother with NETs.

Several aspects of the HWC process enabled HD’s success. First, with a whole-person focus, coaching successfully facilitated her improvement in numerous areas of health (see Table 3), all of which affected and synergistically supported one another. Second, the intervention is individualized for each patient based on their own unique values, aspirations, and circumstances. This personalization enabled HD, with the assistance of the coach, to create a plan suited to work specifically for her. Third, the coach’s unconditional positive regard (a critical element of coaching) and guidance toward small, attainable actions empowered the patient to try new things and continue to move forward even during setbacks. As reported, the patient was able to maintain and even augment her improvements for more than a year after HWC. She had successfully reached the maintenance stage for a number of behaviors, including a standardized bed and wake time, meditation/prayer, regular exercise, and intermittent fasting. Maintenance is a critical stage in being able to sustain behavioral change over time. 30 Her ability to develop and maintain a number of healthy behaviors is especially notable given the time period included the severe stress of a worldwide pandemic (COVID-19) and a contentious political and social environment in the United States.

As described earlier, cancer caregivers often face anxiety and difficulty navigating role strain. As a result of what she learned and practiced in HWC, HD was able to decrease her stress and improve her ability to cope with it. Rather than using food or television, she began to successfully manage anxiety and stress through the tools of setting healthy relationship boundaries, exercise, regular prayer, and reframing her thoughts. Balancing multiple roles can be especially challenging for caregivers; through the coaching process, HD learned how to navigate her life’s competing demands. She was able to continue to care for her mother in the role of caregiver, while also incorporating her own health, growth, and development. Her trichotillomania improved, but was not fully resolved and there were periods of relapse.

As valuable as HWC is, it does not work for everyone. Limitations of this case report include that this is a single case of a highly educated and motivated patient who was able to optimize the benefits of the intervention. As such, her experience may not apply to all cancer caregivers or to the general population. Also, many of the reported outcomes were self-reported and subjective. Additional objective measures, such as activity from an activity tracker or scores on a validated distress scale, would strengthen the report. Future research should address these issues and include a larger sample size in order to further understand potential feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy.

Conclusion

The use of HWC with an adult cancer caregiver resulted in successful outcomes in many domains, including those that can be a particular struggle for caregivers. This shows the promise of HWC in improving quality of life for caregivers, who need support just as much or possibly more than the cancer patient does. The key finding in this case is that HWC should be considered a viable option for supporting caregivers in the multiple physical, psychological, and emotional challenges they face. Perhaps this can help prevent chronic illness in caregivers and avoid further strain on an already stretched medical system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Los Angeles Carcinoid Neuroendocrine Tumor Society for funding the Los Angeles Carcinoid Neuroendocrine Tumor Society health coaching project itself. Without their vision and support, this case study would not be possible. We also acknowledge this case patient for her hard work and for inspiring us.

Footnotes

Funding: None declared

Conflicts of Interest: Ruth Q Wolever serves as Chair of the Certification Commission and is on the Board of Directors for the National Board for Health and Wellness Coaching. She has grant funding from the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, contract funding from Meharry Medical Center and the Coalition for Better Health, and consults for Fullfill, Inc and Wondr. Katherine Smith serves on the National Board of Health and Wellness Coaching Research Commission and the American Public Health Association's Integrative, Traditional and Complementary Health Practices Executive Committee.

Author Contributions: Katherine Smith, MPH, NBC-HWC, ACC, participated in the critical review, drafting, and submission of manuscript. Leeann Hays, BSN, RN, NBC-HWC, participated in critical review and drafting of manuscript, and delivered the intervention. Lisa Yen, BSN, MSN, ACNP-BC, NBC-HWC, participated in patient recruitment and critical reveiw and drafting of the manuscript. Ruth Q Wolever, PhD, NBC-HWC, oversaw the research study and participated in critical review and drafting of manuscript. All authors have given final approval to the manuscript.

Consent: Informed consent was received from the case patient.

References

- 1.Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, et al. Trends in the incidence, prevalence, and survival outcomes in patients with neuroendocrine tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(10):1335–1342. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim Y, Given BA. Quality of life of family caregivers of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2008;112(S11):2556–2568. 10.1002/cncr.23449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Q, Terhorst L, Geller DA, et al. Trajectories and predictors of stress and depressive symptoms in spousal and intimate partner cancer caregivers. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2020;38(5):527–542. 10.1080/07347332.2020.1752879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodges LJ, Humphris GM, Macfarlane G. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between the psychological distress of cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(1):1–12. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer caregiving in the U.S . An Intense, Episodic, and Challenging Care Experience. Accessed 7 December 2020. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CancerCaregivingReport_FINAL_June-17-2016.pdf.

- 6.Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19(10):1013–1025. 10.1002/pon.1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaumont JL, Cella D, Phan AT, Choi S, Liu Z, Yao JC. Comparison of health-related quality of life in patients with neuroendocrine tumors with quality of life in the general US population. Pancreas. 2012;41(3):461–466. 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182328045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh S, Granberg D, Wolin E, et al. Patient-reported burden of a Neuroendocrine Tumor (NET) diagnosis: Results from the first global survey of patients with NETs. J Glob Oncol. 2017;3(1):43–53. 10.1200/JGO.2015.002980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hendrix CC, Bailey DE, Steinhauser KE, et al. Effects of enhanced caregiver training program on cancer caregiver’s self-efficacy, preparedness, and psychological well-being. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(1):327–336. 10.1007/s00520-015-2797-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodschwinna D, Lorenz I, Bauereiss N, Gündel H, Baumeister H, Hoenig K. PartnerCARE-a psycho-oncological online intervention for partners of patients with cancer: Study protocol for a randomised controlled feasibility trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e035599. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolever RQ, Simmons LA, Sforzo GA, et al. A systematic review of the literature on health and wellness coaching: Defining a key behavioral intervention in healthcare. Glob Adv Health Med. 2013;2(4):38–57. 10.7453/gahmj.2013.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett JA, Lyons KS, Winters-Stone K, Nail LM, Scherer J. Motivational interviewing to increase physical activity in long-term cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res. 2007;56(1):18–27. 10.1097/00006199-200701000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawkes AL, Pakenham KI, Chambers SK, Patrao TA, Courneya KS. Effects of a multiple health behavior change intervention for colorectal cancer survivors on psychosocial outcomes and quality of life: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2014;48(3):359–370. 10.1007/s12160-014-9610-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barakat S, Boehmer K, Abdelrahim M, et al. Does health coaching grow capacity in cancer survivors? A systematic review. Popul Health Manag. 2018;21(1):63–81. 10.1089/pop.2017.0040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawkes AL, Chambers SK, Pakenham KI, et al. Effects of a telephone-delivered multiple health behavior change intervention (CanChange) on health and behavioral outcomes in survivors of colorectal cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(18):2313–2321. 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.5873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Street RL, Slee C, Kalauokalani DK, Dean DE, Tancredi DJ, Kravitz RL. Improving physician-patient communication about cancer pain with a tailored education-coaching intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(1):42–47. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas ML, Elliott JE, Rao SM, Fahey KF, Paul SM, Miaskowski C. A randomized, clinical trial of education or motivational-interviewing-based coaching compared to usual care to improve cancer pain management. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39(1):39–49. 10.1188/12.ONF.39-49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ammentorp J, Uhrenfeldt L, Angel F, Ehrensvärd M, Carlsen EB, Kofoed P-E. Can life coaching improve health outcomes? A systematic review of intervention studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):1–11. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kivelä K, Elo S, Kyngäs H, Kääriäinen M. The effects of health coaching on adult patients with chronic diseases: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97(2):147–157. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, Moher D, Sox H, Riley DS. The CARE guidelines: Consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(1):46–51. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deci EL. Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: An overview of self-determination theory. In: Ryan RM, ed. Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2012:85–107. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York: Guilford Publishing; 2017. 10.1521/978.14625/28806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bem DJ. Self-perception: An alternative interpretation of cognitive dissonance phenomena. Psychol Rev. 1967;74(3):183–200. 10.1037/h0024835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bem DJ. Self-perception theory. In: Berkowitz L, ed. Advances in Experimental Psychology. Vol 6., New York: Academic Press; 1972:1–62. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheldon KM. Becoming oneself: The central role of self-concordant goal selection. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2014;18(4):349–365. 10.1177/1088868314538549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolever RQ, Dreusicke MH, Fikkan JL, et al. Integrative health coaching for patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(4):629–639. 10.1177/0145721710371523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolever RQ, Caldwell KL, Wakefield JP, et al. Integrative health coaching: An organizational case study. Explore (NY). 2011;7(1):30–36. 10.1016/j.explore.2010.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith LL, Lake NH, Simmons LA, Perlman A, Wroth S, Wolever RQ. Integrative health coach training: A model for shifting the paradigm toward patient-centricity and meeting new national prevention goals. Glob Adv Health Med. 2013;2(3):66–74. 10.7453/gahmj.2013.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prochaska JO, Norcross JC, DiClemente CC. Changing for Good: A Revolutionary Six-Stage Program for Overcoming Bad Habits and Moving Your Life Positively Forward. NewYork: Harper Collins; 2010. [Google Scholar]