Abstract

The circadian rhythm involves multiple genes that generate an internal molecular clock, allowing organisms to anticipate environmental conditions produced by the Earth’s rotation on its axis. Here, we present the results of the manual curation of 27 genes that are associated with circadian rhythm in the genome of Diaphorina citri, the Asian citrus psyllid. This insect is the vector for the bacterial pathogen Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (CLas), the causal agent of citrus greening disease (Huanglongbing). This disease severely affects citrus industries and has drastically decreased crop yields worldwide. Based on cry1 and cry2 identified in the psyllid genome, D. citri likely possesses a circadian model similar to the lepidopteran butterfly, Danaus plexippus. Manual annotation will improve the quality of circadian rhythm gene models, allowing the future development of molecular therapeutics, such as RNA interference or antisense technologies, to target these genes to disrupt the psyllid biology.

Data description

Background

Huanglongbing (HLB), or citrus greening disease, is caused by the bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (CLas), which infects citrus phloem. This causes loss of fruit production and, eventually, tree death [1, 2]. The Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri (Order: Hemiptera; NCBI:txid121845) acts as an effective vector for the pathogen, thereby spreading the disease. Currently, there is no effective treatment to stop the disease, and it has caused widespread crop damage, resulting in substantial financial losses in the citrus industry [3]. To prevent further damages, the development of management strategies, such as molecular therapeutics, are being investigated, which requires a solid foundation of the genetic basis of psyllid biology. To better understand D. citri biology, we first need to identify gene pathways within the psyllid genome. To this end, genes involved in the main circadian rhythm pathway loops, along with ancillary circadian rhythm genes, were manually annotated in the D. citri genome. Circadian rhythm genes serve to regulate various time-based metabolic processes [4, 5]. Thus, disruption of these genes can affect various downstream biological processes. This makes many of the identified genes promising targets for the development of molecular therapeutics based on RNA interference (RNAi) strategies in insects (Table 1). Disruption of D. citri circadian rhythm may alter psyllid behavior, potentially hindering the spread of HLB.

Table 1.

List of annotated genes related to circadian rhythm, with the outcomes from corresponding RNA interference (RNAi) studies.

| Genes | Organism | RNAi outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Cycle and Mip | Plautia stali | RNAi of cyc in conjunction with myoinhibitory peptide (Mip) induced diapause by disrupting photo periodic response in ovarian development [6] |

| Cycle | Riptortus pedestris | Diapause was induced under a diapause-averting photoperiod [7] |

| Period | Riptortus pedestris | Diapause was prevented under a diapause-inducing photoperiod [7] |

| Period | Ostrinia nubilalis | Underlies a polymorphism among populations that results in the early termination of diapause [8] |

| Pigment-dispersing factor receptor | Ostrinia nubilalis | Affects diapause occurrence and may influence seasonal timing through alteration of circadian clock function [8] |

| Clock | Schistocerca gregaria | Knockdown of clk caused mortality in female insects before breeding age [9] |

| Period | Schistocerca gregaria | per and tim RNAi resulted in reduced progeny suggesting that PER and TIM are needed in the ovaries for egg development [9] |

| Timeless | Schistocerca gregaria | tim knockdown affected female insect egg deposition and resulted in reduced numbers of offspring [9] |

| Vrille | Drosophila melanogaster | Dominant maternal enhancer of defects in dorsoventral patterning causing embryo mortality [10] |

| Takeout | D. melanogaster | Mutant takeout causes abnormal locomotor activity resulting in insect death from starvation [11] |

Context

The circadian rhythm is critical for an organism to regulate its biological systems in conjunction with the external environment. It is a process regulated by the interactions between multiple genes, allowing a cell to respond to, and anticipate, day/night conditions during a roughly 24-hour cycle [4, 5]. Periodicity occurs owing to fluctuations in gene expression autoregulated by inhibitory feedback loops based on external stimuli (principally light, but also temperature, humidity, nutrition, and others), also known as Zeitgeibers [5, 12–15]. The basic mechanism for circadian clocks in animals is highly conserved across all taxa, and the best-studied insect circadian system is that of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster (Order: Diptera) [16]. In this model, the circadian rhythm is primarily regulated by six transcription factors: PERIOD (PER), TIMELESS (TIM), CYCLE (CYC), CLOCK (CLK), VRILLE (VRI), and PAR DOMAIN PROTEIN 1 (PDP1) [17]. The D. melanogaster model is an invaluable reference point for understanding the circadian rhythm, but it cannot be completely generalized to D. citri. This is because hemipterans are a more evolutionarily ancient lineage [18] and there are differences in cryptochrome genes (cry) between insects [19–21].

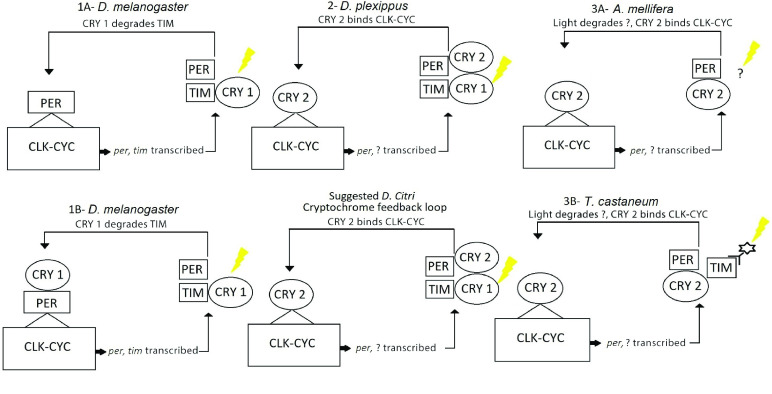

In nature, individual cryptochrome proteins (CRY) have evolved to complete different functions. CRY1 operates as a blue light receptor, while CRY2 works as a circadian transcription repressor [19, 21]. Insects can possess one or both cryptochrome genes, and this affects the operation of their feedback loops. These differences result in three different circadian rhythm models: the D. melanogaster model possesses cry1, the butterfly Danaus plexippus possesses both cry1 and cry2, and the honeybee Apis mellifera and the beetle Tribolium castaneum have only cry2 (Figure 1) [20, 21]. Cryptochrome variation gives possible insight into the evolution and function of the circadian rhythm in insects, but also makes the D. melanogaster model different from non-dipterans because they possess cry2 [20].

Figure 1.

Insect clockwork pathway structure differs based on which of the two functionally different cryptochromes (CRY) are present [20]. Drosophila melanogaster possesses only CRY1, and there are two proposed models for its circadian pathway. (1A) CRY1 degrades the transcript of timeless (tim), and only PERIOD (PER) binds to the CLOCK-CYCLE (CLK-CYC) complex [19]. (1B) The second D. melanogaster model proposes that CRY1 degrades TIMELESS (TIM) then binds to PER [22]. (2) Danaus plexippus possesses both CRY1 and CRY2, which perform different functions [20]. The presence of both cryptochromes in Diaphorina citri suggests a similar circadian model to D. plexippus. (3) Apis mellifera and Tribolium castaneum possess only CRY2. Since CRY1 is not present to function as a blue light receptor, light interacts with alternate proteins to regulate circadian rhythm; however, CRY 2 retains the same function as in the other clockwork models. (3A) The mechanism of light interaction is unknown in A. mellifera. (3B) In T. castaneum, light enters the pathway by interacting with TIM and other associated factors (represented by the “star”) [23]. The interaction of light with the pathway is represented by the lightning bolt symbol.

In addition to cryptochrome variation between insects, the presence or absence of other genes can affect the operation of an organism’s circadian model. For example, the D. citri genome possesses clockwork orange (cwo), Hormone receptor 3 (Hr3) and ecdysone-induced protein 75 (E75), which suggests a cyc transcriptional regulation system similar to those found in Thermobia domestica and Gryllus bimaculatus [24, 25].

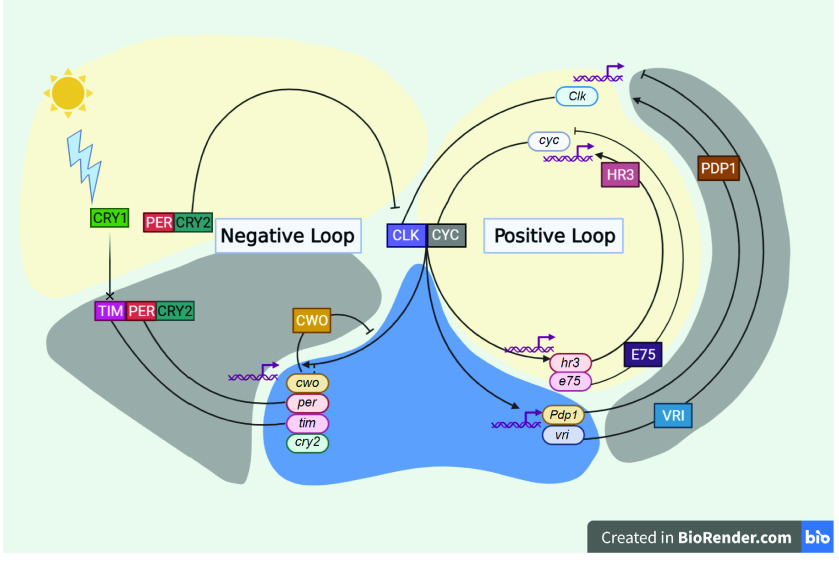

Based on the genes identified and annotated in the D. citri genome, Figure 2 presents a theoretical model of the circadian rhythm pathway in D. citri. Regulation of the pathway operates in two feedback loops; one negative and one positive [17]. The negative loop involves the per and tim genes, whose expression is promoted when a heterodimer of CLK and CYC binds to their E-Box promoters [16, 26–29]. The CLK–CYC heterodimer is also responsible for the transcriptional activation of cry2 and cwo [25]. Transcripts for tim and per peak at dusk, allowing their protein products to accumulate in the cytoplasm during the night [16, 25, 30]. A trimer of PER, TIM and CRY2 forms and migrates to the nucleus. CRY1 acts as a blue light photoreceptor, which in turn degrades TIM, resulting in a PER–CRY2 dimer [31]. PER primarily serves to stabilize CRY2, which acts as an important transcriptional repressor, preventing CLK–CYC from transcribing per and tim genes, resulting in mRNA levels being minimum at dawn [31, 32]. Additionally, during the night, CWO acts to repress per and tim transcription through competitive inhibition, binding to per and tim E-box promoters, preventing CLK–CYC from inducing expression [25].

Figure 2.

Theoretical model of circadian rhythm in Diaphorina citri based on curated genes and studies in other insect species. Ovals represent genes; boxes represent proteins (with the exception of “Positive Loop” and “Negative Loop” which are labels); connected boxes indicate that a protein complex has formed; lines from boxes to ovals ending in arrows represent that a protein is inducing transcriptional activation of a gene; lines from boxes to ovals ending in perpendicular lines represent that a protein is repressing transcriptional activation of a gene; lines connecting ovals to boxes indicate that a gene was translated into a protein; lines ending in an “X” indicate that degradation is occurring; helical symbols indicate that transcription occurs; the sun and lightning bolt symbol represent the interaction of light with the pathway; the colors of the background correspond to the time of day that a part of the process occurs (yellow: day, gray: night, blue: dusk). List of abbreviations: Clk: clock; CRY1: Cryptochrome 1; cry2: cryptochrome 2; cwo; clockwork orange; cyc: cycle; e75: ecdysone-induced protein 75; hr3: hormone receptor 3; Pdp1: par domain protein 1; per: period; tim: timeless; vri: vrille. Figure created using BioRender.com [33].

In the positive loop, Clk and cyc are rhythmically expressed. Transcription of vri and Pdp1 occur through activation by CLK—CYC [16]. VRI acts as a transcriptional repressor and acts to delay the action of PDP1, which acts as a transcriptional activator [16, 17]. Expression of Clk by PDP1 occurs at dawn, causing Clk transcripts to peak in concentration in the opposite phase to that of per and tim [16]. Rhythmic regulation of cyc transcription was observed to occur in a similar manner, with E75 acting as a transcriptional repressor which that delays expression of cyc by HR3 [24, 25].

Methods

Through a community genome curation project, the D. citri (NCBI:txid121845) genes involved in the circadian rhythm pathway were manually annotated in genome version 3.0 [34–36], following our standard annotation protocol (Figure 3) [37]. Protein sequences of circadian rhythm genes were collected from the National Center of Biotechnology (NCBI) protein database (RRID:SCR_003496) [38]. The collected protein sequences were used to BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) search the D. citri MCOT (Maker (RRID:SCR_005309), Cufflinks (RRID:SCR_014597), Oases (RRID:SCR_011896), and Trinity (RRID:SCR_013048)) protein database for MCOT model identifiers [39]. The circadian rhythm genes were found in the D. citri genome (version 3.0) using the mapped MCOT model identifiers in the WebApollo (RRID:SCR_005321) system hosted at the Boyce Thompson Institute. Utilizing the NCBI BLAST tool (RRID:SCR_004870), a reciprocal BLASTp was performed for each located D. citri gene model to confirm the predicted circadian rhythm gene. Examination of RNA-seq reads, Illumina DNA-seq reads, and PacBio Iso-seq transcripts were used to annotate the final D. citri circadian rhythm genes. These tools allowed common issues within gene models to be identified and corrected, such as artifact duplications, splice site errors, incorrect untranslated regions, insertions, deletions, incorrect start sites, incorrect stop sites, faulty exon boundaries, and alternative splice sites. These issues arise from sequencing or genome assembly errors and analysis of available evidence makes necessary revisions possible. A more detailed explanation of the annotation process is available through a previously reported protocol (Figure 3) [37]. After correcting any of the common issues previously described, the manually annotated circadian rhythm gene models were included into the version 3.0 Official Gene Set (OGS).

Figure 3.

Protocol for Diaphorina citri genome community curation [37]. https://www.protocols.io/widgets/doi?uri=dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.bniimcce

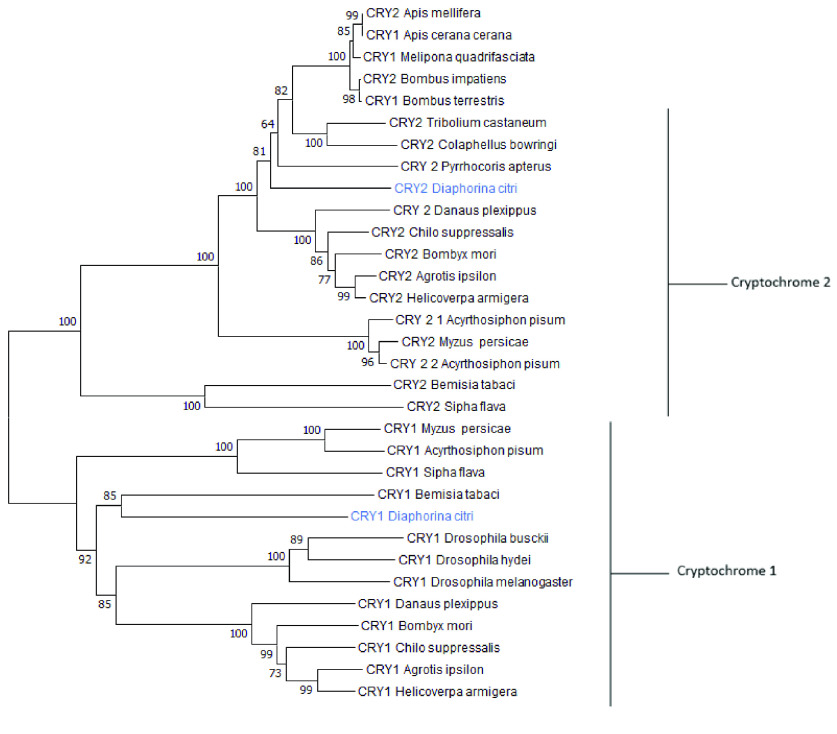

Table 2 shows the evidence supporting the D. citri final gene models [39]. Comparison of data from the MCOT transcriptome, de novo transcriptome, PacBio Iso-seq transcripts, and RNA-seq reads and the annotated D. citri circadian rhythm gene determined the status of support listed in Table 2. A gene copy number table was created to observe the number of true duplications of circadian rhythm genes of interest that were present within other insect species (Table 3). Creation of this table involved conducting peptide BLASTs for each OGS v3.0 D. citri model. The NCBI descriptions, percentage sequence identity, and query coverage for each gene were observed. Only orthologs with appropriate descriptions with a 40% or higher identity and query coverage were incorporated as evidence. Table 4 displays the ortholog accession numbers used to create Table 3. A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree (Figure 4) of the D. citri CRY1 and CRY2 protein sequences was made, along with various related orthologs, with MEGA 7 (MEGA software, RRID:SCR_000667) [40]. Tree construction used MUSCLE (RRID:SCR_011812) for multiple sequence alignments with p-distance for determining branch length and 1000 bootstrap replicates [40]. The insects, with their corresponding accession numbers, used to create the phylogenetic tree are found in Table 5. The circadian rhythm pathway image (Figure 2) was created using BioRender (RRID:SCR_018361) [33].

Table 2.

Evidence supporting gene annotation available as tracks in the Apollo genome curation tool. There are 27 annotated circadian rhythm genes in Diaphorina citri. Each gene model has been assigned an Official Gene Set (OGS) version 3.0 gene identifier. Evidence types used to validate or modify the structure of the gene model have been marked with an X if available and are left blank if unavailable. Genes marked as complete have been marked with an X and have a complete coding region. Those not marked as complete are left blank and were only annotated as partial gene models. Completeness refers to the wholeness of the coding regions of these models and was determined through comparison with orthologous proteins. Descriptions of the various evidence sources and their strengths and weaknesses are included in the online protocol [37]. All evidence supporting annotation is available from the Citrus Greening Solutions website [39]. Terminology is used as in Flybase [41].

| Gene | OGSv3 ID | MCOT ID | de novo | Gene model | Evidence supporting annotation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete/Partial | MCOT | Iso-seq | RNA-seq | Ortholog | ||||

| D. melanogaster model core clock genes | ||||||||

| Circadian locomotor output cycles protein kaput | Dcitr05g05480.2.1 | MCOT03010.0.CO | X | X | X | X | ||

| Cycle | Dcitr05g16440.2.3 | X | X | X | ||||

| PAR domain protein 1 | Dcitr05g02780.2.1 | MCOT14609.2.CT | X | X | X | X | ||

| Period | Dcitr09g03540.1.1 | MCOT12213.0.CO | X | X | X | |||

| Timeless | Dcitr04g02940.1.1 | MCOT23350.0.CT | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Vrille | Dcitr10g05230.1.1 | MCOT16283.2.CT | X | X | X | X | ||

| Other negative loop-associated genes | ||||||||

| Casein kinase 2 alpha subunit | Dcitr02g18000.1.1 | MCOT21500.0.CO | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Casein kinase 2 beta subunit | Dcitr11g02180.1.1 | X | X | X | X | |||

| Cryptochrome 1 | Dcitr07g01550.1.1 | MCOT00625.0.CT | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Cryptochrome 2 | Dcitr09g09100.1.1 | MCOT19207.3.CO | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Double-time | Dcitr07g07760.2.1 | MCOT08150.0.MT | X | X | X | X | ||

| Other positive loop-associated genes | ||||||||

| Ecdysone-induced protein 75 | Dcitr12g07770.2.1 | MCOT02379.0.CT | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Hormone Receptor 3/Rora | Dcitr08g04060.1.1 | MCOT23147.0.CC | X | X | X | X | ||

| Genes documented to be under circadian influence | ||||||||

| Clockwork orange isoform 1 | Dcitr01g06780.1.1 | MCOT17066.1.CO | X | X | X | X | ||

| Clockwork orange isoform 2 | Dcitr01g06780.1.1 | MCOT17066.2.CO | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Ecdysone receptor | Dcitr02g19530.1.1 | MCOT15763.0.CT | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Hormone Receptor 3 Homolog | Dcitr08g02450.1.3 | X | X | X | ||||

| Insulin related peptide | Dcitr06g08750.1.1 | MCOT08282.0.MO | X | X | X | |||

| Lark | Dcitr01g16940.1.1 | MCOT03363.0.CT | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Ovary maturing parsin | Dcitr09g03370.1.1 | MCOT04488.1.CT | X | X | ||||

| Protein phosphatase PP2A 55 kDa regulatory subunit | Dcitr09g05720.1.1 | MCOT08076.0.OO | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Serine/Threonine-Protein phosphatase 2A 56 kDa regulatory subunit epsilon | Dcitr03g10950.1.1 | MCOT02984.0.CT | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Serine/Threonine-Protein phosphatase 2A 56 kDa regulatory subunit epsilon | Dcitr03g03510.1.1 | MCOT08848.0.MO | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Takeout 1 | Dcitr07g05480.1.3 | MCOT21001.2.CT | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Takeout 2 | Dcitr06g07220.1.1 | MCOT16413.0.CO | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Takeout-Like | Dcitr09g07620.1.1 | MCOT13357.0.CC | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Timeless 2/timeout fragment 1 | Dcitr00g11340.2.1 | X | X | |||||

| Timeless 2/timeout fragment 2 | Dcitr00g05520.2.1 | X | ||||||

| Timeless 2/ timeout Fragment 3 | Dcitr00g05510.2.1 | X | X | |||||

| Vestigial | Dcitr08g07920.1.1 | MCOT06810.0.CC | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Vitellogenin-1 | Dcitr08g09320.1.1 | X | X | |||||

| Vitellogenin-2 | Dcitr01g05660.1.1 | MCOT05282.2.CO | X | X | X | X | ||

Table 3.

Gene copy numbers for Diaphorina citri compared with other insects. Numbers were obtained from NCBI unless otherwise indicated, except for D. melanogaster, whose copy numbers were obtained from Flybase [41].

| Gene name | Diaphorina citri | Acyrthosiphon pisum | Bemisia tabaci | Cimex lectularius | Halyomorpha halys | Drosophila melanogaster | Anopheles aegypti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. melanogaster model core clock genes | |||||||

| Circadian locomotor output cycles protein kaput | 1 | 1* | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cycle | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PAR domain protein 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Period | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Timeless | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Vrille | 1 | 1* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Other negative loop-associated genes | |||||||

| Casein kinase 2 alpha subunit | 1 | 1* | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Casein kinase 2 beta subunit | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cryptochrome 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Cryptochrome 2 | 1 | 2* | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| double-time | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other positive loop-associated genes | |||||||

| Ecdysone-induced protein 75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hormone Receptor 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Genes documented to be under circadian influence | |||||||

| Clockwork orange | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ecdysone receptor | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hormone Receptor 3 Homolog | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Insulin related peptide | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Lark | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ovary maturing parsin | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Protein phosphatase PP2A 55 Kda regulatory subunit | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Serine/Threonine Protein phosphatase 2A 56 Kda regulatory subunit epsilon | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Takeout | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 8 |

| Takeout-Like | 1 | 7 | 12 | 19 | 23 | 0 | 1 |

| Timeout | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Vestigial | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Vitellogenin-1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Vitellogenin-2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

*Denotes gene copy numbers retrieved from Cortes et al. 2010 [16].

Table 4.

Accession numbers searched using NCBI for ortholog copy number analysis (see Table 3). Genes without listed accession numbers underneath the corresponding Hemiptera did not meet the criteria listed in the Methods section, or had no identifiable NCBI ortholog accession number.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of Cryptochrome 1 and 2 amino acid sequences. Diaphorina citri cryptochromes are in blue and group with their respective type of cryptochrome. Nephila clavipes CRY2 was used as the outgroup. The tree was made with MEGA7 using the bootstrap test (1000) replicates with the percentage of replicate trees clustered together shown next to the branches. The total number of positions used for alignment was 349 using MUSCLE alignment in MEGA7 [40].

Table 5.

NCBI accession numbers used to create the neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree, displaying orthologous sequences for CRY1 and CRY2 genes.

| Insects | CRY1 | CRY2 |

|---|---|---|

| Non-hemipteran | ||

| Drosophila melanogaster | NP_732407.1 | |

| Danaus plexippus | XP_032522602.1 | XP_032511499.1 |

| Drosophila busckii | XP_017845052.1 | |

| Drosophila hydei | XP_023171160.2 | |

| Apis mellifera | NP_001077099.1 | |

| Apis cerana | PBC28621.1 | |

| Melipona quadrifasciata | KOX67887.1 | |

| Bombus impatiens | NP_001267051.1 | |

| Bombus terrestris | XP_003398531.1 | |

| Tribolium castaneum | NP_001076794.1 | |

| Colaphellus bowringi | APP94027.1 | |

| Agrotis ipsilon | AFJ22638.1 | AFJ22639.1 |

| Helicoverpa armigera | XP_021184238.1 | ADN94465.2 |

| Bombyx mori | NP_001182628.1 | NP_001182627.1 |

| Chilo suppressalis | CDK02014.2 | AHL69753.1 |

| Hemipteran | ||

| Bemisia tabaci | XP_018915448.1 | XP_018904762.1 |

| Sipha flava | XP_025414102.1 | XP_025423877.1 |

| Myzus persicae | AUN43313.1 | AUN43314.1 |

| Acyrthosiphon pisum | NP_001164532.2 |

NP_001164572.1 NP_001164573.1 |

| Pyrrhocoris apterus | AGI17567.1 | |

Data validation and quality control

Core clock genes

Gene models were annotated in the Apollo D. citri v3.0 genome using the Citrus Greening online portal [42, 43]. We identified all six of the core clock genes found in the D. melanogaster model [11]: Clk, cyc, per, tim, vri and Pdp1. As has been reported in D. melanogaster and the hemipteran A. pisum, only one copy of each gene was found in the D. citri genome (Table 3). However, false duplications of Clock and Pdp1 resulting from genome assembly errors were found and removed from the OGS. These errors are identifiable within WebApollo by examining the Illumina DNA-seq or RNA-seq data for the locus and by conducting NCBI pairwise BLAST comparisons between duplicate and true models. Additionally, two of the models, per and tim, were substantially improved from the computational gene predictions. Annotation of per identified and corrected a splice site error, increased the amino acid length of the peptide, and improved BLAST score, query coverage and percent identity. Curation of tim also led to an amino acid increase from 1093 to 1109 and saw notable improvements in BLAST score, query coverage and percentage sequence identity. Notably, the added amino acids were part of a Timeless serine-rich domain in the 260–292 amino acid range of the peptide, which has been identified as an important site for phosphorylation [44]. Annotation of the vri model may prove particularly important since lack of VRI function leads to embryonic mortality in D. melanogaster (Table 1) [10]. This may make vri a useful target for D. citri population control.

Other negative loop-associated genes

Genes related to the negative feedback loop, aside from the core clock genes, include cry1, cry2, Casein kinase 2 alpha (Ck2𝛼) subunit, Casein kinase 2 beta (Ck2𝛽) subunit, and double-time (dbt) (Table 3). Cryptochrome copy number variation (Figure 1) is of great importance since discrepancies between insects gives possible insight into the evolution and function of circadian rhythm in insects [20]. In D. citri, both cry1 and cry2 genes were found. A pairwise alignment between the two annotated models resulted in 41% amino acid identity with 93% query coverage. Both models have the DNA_photolyase (pfam00875) and FAD_binding_7 (pfam03441) domains typically found in CRY proteins. The DNA_photolyase domain is the binding site for a light-harvesting cofactor, and the FAD_binding_7 domain binds a flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) molecule [45]. The BLAST results confirm that the two models were not duplications, and phylogenetic analysis could discern the identity of each cryptochrome (Figure 4). The presence of cry1 and cry2 genes in D. citri reinforces that non-drosophilid insects possess cry2 [20]. The presence of both genes also suggests that D. citri follows an ancestral butterfly-like clockwork model (Figure 1) [20]. D. citri only has one cry2 gene, while A. pisum has two cry2 genes; this supports the assertion that A. pisum core clock genes may be evolving at a faster rate than in other hemipterans [16].

Another important gene in the negative loop is dbt, also known as discs overgrown (dco). This gene encodes a circadian rhythm regulatory protein that affects the stability of PER [46] and was also annotated. The mammalian homolog of dbt is Casein kinase 1 (Ck1) epsilon [47]. The Homo sapiens (ABM64212.1) and D. melanogaster (NP_733414.1) homologs both have the STKc_CK1_delta_epsilon (accession number: cd14125) domain at the same position, amino acids 8–282. The D. citri model reflects the conservation between species by also exhibiting a CK1_delta_epsilon domain located at the same position.

Other positive loop-associated genes

Two genes present in D. citri, Hr3 and E75, are responsible for positive loop transcriptional regulation of cyc in T. domestica and G. bimaculatus [24, 25], and a similar regulation mechanism may exist in D. citri (Figure 2). Curation of these genes led to minimal changes to the Hr3 gene model; however, changes in E75 resulted in its translated peptide sequence being extended from 664 to 729. This improved its score, percentage sequence identity, and query coverage when BLASTed to orthologous insects.

Genes documented to be under circadian influence

Fourteen additional genes involved in the circadian rhythm, but not directly classified in the two feedback loops, were also annotated (Table 3). Of these genes, takeout is of interest as a potentially good molecular target to control D. citri. Takeout in D. melanogaster has been shown to regulate starvation response, and if the gene or protein loses function, the organism dies faster in starvation conditions than the wild type (Table 1) [11]. Takeout and takeout-like in D. citri have low gene copy numbers compared with other non-drosophilid insects (Table 3). The discrepancy may be because these genes are computationally predicted in the other insects, and many sequences are short and might represent fragments of larger genes.

Another of these ancillary genes annotated was the tim paralog timeout, also known as timeless 2 [23]. Timeout has several functions and does not fit categorically into either of the feedback loops, although it is structurally very similar to tim [48]. To confirm that the annotated gene models were not the result of a false duplication in the genome assembly, they were compared with orthologs from other insects. The conserved domains in protein sequences for tim and timeout from D. melanogaster (NP_722914.3 and NP_524341.3) and A. pisum (ARM65416.1 and XP_016662949.1) were compared with the D. citri sequences. For the TIM proteins, the main conserved domain was the TIMELESS (pfam04821) domain located near the N-terminus. TIMEOUT proteins also have this N-terminal TIMELESS domain, but also have a C-terminal TIMELESS_C (pfam05029) domain. These conserved domains were also identified in the corresponding D. citri protein sequences, indicating that the timeout model is not an artifactual duplication of tim. In genome version 3.0, a problem still exists causing the timeout sequence to be split into three different models (Table 2), despite the comparative sequence analysis that supports the presence of this gene in the genome.

Conclusion

The circadian rhythm is an important pathway for an organism’s ability to regulate its biological systems in conjunction with the external environment [5]. A total of 27 putative circadian rhythm-associated genes have been annotated in the D. citri genome (Table 2). These data have been used to construct models of both positive and negative feedback loops. The relationship of these genes to D. citri circadian rhythm is putative and is based on insect orthologs. Future research with RNA-seq experimental analysis over a 24-hour day/night cycle will validate these relationships and provide a more definitive list of circadian rhythm associated genes in D. citri. Annotation of these genes provides a better understanding of the circadian pathway in D. citri and adds to the evidence supporting the ways in which hemipteran circadian rhythm pathways function.

Reuse potential

Manual curation of these circadian rhythm genes was conducted as part of the D. citri collaborative community annotation project [43, 49]. These models will be incorporated into the third OGS of the Citrus Greening Expression Network (CGEN) [43]. This publicly available tool is useful for comparative expression profiling through its transcriptome data for different D. citri tissues and life stages. There is considerable potential for the practical application of these curated models in controlling the spread of Huanglongbing. Understanding the circadian pathway and essential genes within it provide opportunities for pest control strategies through molecular-based therapeutics. Availability of accurate gene models brought about through our manual annotations can facilitate the design of future experiments aimed at developing gene editing and RNAi systems to target and disrupt critical D. citri biological processes.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Helen Wiersma-Koch (Indian River State College), Elizabeth Michels, Sarah Michels, and Tanner Wise for their assistance.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by USDA-NIFA grants 2015-70016-23028, HSI 2020-38422-32252 and 2020-70029-33199.

Data Availability

The D. citri genome assembly, official gene sets, and transcriptome data are accessible on the Citrus Greening website [39]. The gene models will also be part of an updated OGS version 3 for D. citri [35, 37, 42]; the data are also available through NCBI (BioProject: PRJNA29447). All additional data supporting this article is available via the GigaScience GigaDB repository [50].

Editor’s note

This article is one of a series of Data Releases crediting the outputs of a student-focused and community-driven manual annotation project curating gene models and, if required, correcting assembly anomalies, for the Diaphorina citri genome project [51].

Declarations

List of abbreviations

BLAST: Basic local alignment search tool; BLASTp: BLAST protein; CGEN: Citrus Greening Expression Network; Ck1: Casein kinase 1; clk: Clock; CLOCK: Circadian locomotor output cycles protein kaput; CLas: Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus; cry1: Cryptochrome 1; cry2: Cryptochrome 2; cwo; clockwork orange; cyc: cycle; dbt: double-time; dco: discs overgrown; E75: ecdysone-induced protein 75; HLB: Huanglongbing; Hr3: Hormone receptor 3; Iso-seq: Full-length isoform sequencing; MCOT: MAKER Cufflinks Oases Trinity; Mip: myoinhibitory peptide; NCBI: National Center for Biotechnology Information; OGS: Official gene set; Pdp1: PAR domain protein 1; per: period; PP2A: Protein phosphatase 2A; RNA-seq: RNA-sequencing; RNAi: RNA interference; STKc: Serine/threonine kinase catalytic domain; tim: timeless; vri: vrille.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by USDA-NIFA grants 2015-70016-23028, HSI 2020-38422-32252 and 2020-70029-33199.

Authors’ contributions

SJB, WBH, TD and LAM conceptualized the study; TD, SS, TDS, CM, JAQ, CV and SJB supervised the study; TD, SS, LAM and SJB contributed to project administration; LD, CM, JN, YO, ME, ND, RM, AN, RH, KG, MK, MTH conducted the investigation; PH, SS, MF-G contributed to software development; SS, TDS, PH and MF-G developed methodology; SJB, WBH, KP-S, JAQ, TD and LAM acquired funding; MR, LD, TP and YO prepared and wrote the original draft; LD, TP, WBH, TDS, JAQ, JBB, YO, ME, RM, AN, reviewed and edited the draft.

References

- 1.Garnier M, Jagoueix-Eveillard S, Cronje PR et al. Genomic characterization of a liberobacter present in an ornamental rutaceous tree, Calodendrum capense, in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Proposal of “Candidatus Liberibacter africanus subsp. capensis”. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., 2000; 50: 2119–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.da Graca JV. . Citrus Greening disease. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol., 1991; 29: 109–136. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halbert SE, Manjunath KL. . Asian citrus psyllids (Sternorrhyncha: Psyllidae) and greening disease of citrus: A literature review and assessment of risk in Florida. Fla. Entomol., 2004; 87(3): 330–353. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panda S, Hogenesch JB, Kay SA. . Circadian rhythms from flies to human. Nature, 2002; 417(6886): 329–335. doi: 10.1038/417329a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glossop N, Houl J, Zheng H et al. VRILLE feeds back to control circadian transcription of clock in the Drosophila circadian oscillator. Neuron, 2003; 37: 249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamai T, Shiga S, Goto SG. . Roles of the circadian clock and ENDOCRINE regulator in the photoperiodic response of the Brown-winged green Bug Plautia stali. Physiol. Entomol., 2018; 44(1): 43–52. doi: 10.1111/phen.12274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikeno T, Tanaka SI, Numata H et al. Photoperiodic diapause under the control of circadian clock genes in an insect. BMC Biol., 2010; 8(1): 116. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kozak GM, Wadsworth CB, Kahne SC et al. Genomic basis of CIRCANNUAL rhythm in the European Corn Borer Moth. Curr. Biol., 2019; 29(20): 3501–3509. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tobback J, Boerjan B, Vandersmissen HP et al. The circadian clock genes affect reproductive capacity in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol., 2011; 41(5): 313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George H, Terracol R. . The vrille gene of Drosophila is a maternal enhancer of decapentaplegic and encodes a new member of the bZip family of transcription factors. Genetics, 1997; 146: 1345–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarov-Blat L, Venus So W, Liu L et al. The Drosophila Takeout gene is a novel molecular link between circadian rhythms and feeding behavior. Cell, 2000; 101: 647–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephan FK. . The “other” Circadian System: Food as a Zeitgeber. J. Biol. Rhythms, 2002; 17(4): 284–292. doi: 10.1177/074873002129002591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lincoln G, Andersson H, Loudon A. . Clock genes in calendar cells as the basis of annual timekeeping in mammals-a unifying hypothesis. J. Endocrinol., 2003; 179(1): 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshii T, Vanin S, Costa R et al. Synergic entrainment Of DROSOPHILA’S circadian clock by light and temperature. J. Biol. Rhythms, 2009; 24(6): 452–464. doi: 10.1177/0748730409348551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mwimba M, Karapetyan S, Liu L et al. Daily humidity oscillation regulates the circadian clock to influence plant physiology. Nat. Commun., 2018; 9(1): 4290. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06692-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cortes T, Ortiz-Rivas B, Martinez-Torres D. . Identification and characterization of circadian clock genes in the Pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. Insect Mol. Biol., 2010; 19(2): 123–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cyran S, Buchsbaum A, Reddy K et al. Vrille, Pdp1, and Clock form a second feedback loop in the Drosophila circadian clock. Cell, 2003; 112: 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas G, Dohmen E, Huges DST et al. Gene content evolution in the arthropods. Genome Biol., 2020; 21: 15. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1925-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emery P, Stanewsky R, Helfrich-Forster C et al. Drosophila CRY is a deep brain circadian photoreceptor. Neuron, 2000; 26: 493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan Q, Metterville D, Briscoe A et al. Insect Cryptochromes: Gene duplication and loss define diverse ways to construct insect circadian clocks. Mol. Biol. Evol., 2007; 24(4): 948–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu H, Yuan Q, Froy O et al. The two CRYs of the butterfly. Curr. Biol., 2005; 15(23): 953–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishnan B, Levine J, Lynch M et al. A new role for cryptochrome in a Drosophila circadian oscillator. Nature, 2001; 411: 313–317. doi: 10.1038/35077094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubin EB, Shemesh Y, Cohen M et al. Molecular and phylogenetic analyses reveal mammalian-like clockwork in the honey bee (Apis mellifera) and shed new light on the molecular evolution of the circadian clock. Genome Res., 2006; 16: 1352–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamae Y, Uryu O, Miki T et al. The nuclear receptor genes HR3 and E75 are required for the circadian rhythm in a primitive insect. PLoS One, 2014; 9(12): e114899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomiyama Y, Shinohara T, Matsuka M et al. The role of clockwork orange in the circadian clock of the cricket Gryllus bimaculatus. Zool. Lett., 2020; 6(1): 12. doi: 10.1186/s40851-020-00166-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allada R, White NE, So WV et al. A mutant Drosophila homolog of mammalian CLOCK disrupts circadian rhythms and transcription of period and timeless. Cell, 1998; 93(5): 791–804. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hardin PE, Hall JC, Rosbash M. . Feedback of the Drosophila Period gene product on circadian cycling of its messenger RNA LEVELS. Nature, 1990; 343(6258): 536–540. doi: 10.1038/343536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bargiello TA, Jackson FR, Young MW. . Restoration of circadian behavioural rhythms by gene transfer in Drosophila. Nature, 1984; 312(5996): 752–754. doi: 10.1038/312752a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sehgal A, Price J, Man B et al. Loss of circadian behavioral rhythms and per RNA oscillations in the Drosophila mutant timeless. Science, 1994; 263(5153): 1603–1606. doi: 10.1126/science.8128246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saez L, Young MW. . Regulation of nuclear entry of the Drosophila clock proteins period and timeless. Neuron, 1996; 17(5): 911–920. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu H, Sauman I, Yuan Q et al. Cryptochromes define a novel circadian clock mechanism in monarch butterflies that may underlie sun compass navigation. PLoS Biol., 2008; 6(1): e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardin PE. . The circadian timekeeping system of Drosophila. Curr. Biol., 2005; 15(17): R714–R722. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.BioRender . https://biorender.com/. Accessed 18 June 2021.

- 34.Dunn NA, Unni DR, Diesh C et al. Apollo: Democratizing genome annotation. PLoS Comput. Biol., 2019; 15: e1006790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saha S, Hosmani PS, Villalobos-Ayala K et al. Improved annotation of the insect vector of Citrus greening disease: Biocuration by a diverse genomics community. Database, 2017; 2017: bax032. doi: 10.1093/database/bax032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosmani PS, Shippy T, Miller S et al. A quick guide for student-driven community genome annotation. PLoS Comput. Biol., 2019; 15(4): e1006682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shippy T. . Annotating genes in Diaphorina citri genome version 3. protocols.io. 2020; 10.17504/protocols.io.bniimcce. [DOI]

- 38.National Center for Biotechnology Information Protein Database . Bethesda, MD:NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein. Accessed 01 December 2020.

- 39.Citrus Greening Solution . https://citrusgreening.org/. Accessed 18 December 2020.

- 40.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M et al. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics 34analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol., 2018; 35: 1547–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larkin A, Marygold SJ, Antonazzo G et al. FlyBase: Updates to the Drosophila melanogaster knowledge base. Nucleic Acids Res., 2021; 49(D1): D899–D907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hosmani P, Flores-Gonzalez M, Shippy T et al. Chromosomal length reference assembly for Diaphorina citri using single-molecule sequencing and Hi-C proximity ligation with manually curated genes in developmental, structural and immune pathways. bioRxiv. 2019; 869685. 10.1101/869685. [DOI]

- 43.Flores-Gonzalez M, Hosmani PS, Fernandez-Pozo N et al. Citrusgreening.org: An open access and integrated systems biology portal for the Huanglongbing (HLB) disease complex. bioRxiv. 2019; 868364. 10.1101/868364. [DOI]

- 44.Meissner R-A, Kilman VL, Lin J-M et al. TIMELESS is an important mediator of CK2 effects on circadian CLOCK function in vivo. J. Neurosci., 2008; 28(39): 9732–9740. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0840-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamada T, Kitadokoro K, Inaka K et al. Crystal structure of DNA photolyase from Anacystis nidulans. Nat. Struct. Biol., 1997; 4(11): 887–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Price J, Blau J, Rothenfluh A et al. Double-time is a novel Drosophila clock gene that regulated PERIOD protein accumulation. Cell, 1998; 94: 83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kloss B, Price J, Saez L et al. The Drosophila clock gene double-time encodes a protein closely related to human casein kinase 1 epsilon. Cell, 1998; 94: 97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gu H-F, Xiao J-H, Niu L-M et al. Adaptive evolution of the circadian gene timeout in insects. Sci. Rep., 2014; 4(1): 4212. doi: 10.1038/srep04212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Citrus Greening Solutions . Annotation of psyllid genome. 2018; https://citrusgreening.org/annotation/index. Accessed 18 December 2020.

- 50.Reynolds M, Oliveira Ld, Vosburg C et al. Supporting data for “Annotation of Putative Circadian Rhythm-Associated Genes in Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera: Liviidae)”. GigaScience Database. 2022; 10.5524/100997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Asian citrus psyllid community annotation series. GigaByte. 2022; 10.46471/GIGABYTE_SERIES_0001. [DOI]