Abstract

In the three decades since endocrine disruption was conceptualized at the Wingspread Conference, we have witnessed the growth of this multidisciplinary field and the accumulation of evidence showing the deleterious health effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals. It is only within the past decade that, albeit slowly, some changes regarding regulatory measures have taken place. In this Perspective, we address some historical points regarding the advent of the endocrine disruption field and the conceptual changes that endocrine disruption brought about. We also provide our personal recollection of the events triggered by our serendipitous discovery of oestrogenic activity in plastic, a founder event in the field of endocrine disruption. This recollection ends with the CLARITY study as an example of a discordance between ‘science for its own sake’ and ‘regulatory science’ and leads us to offer a perspective that could be summarized by the motto attributed to Ludwig Boltzmann: “Nothing is more practical than a good theory”.

The concept of endocrine disruption was introduced in 1991 at the Wingspread Conference entitled “Chemically-induced alterations in sexual development: the wildlife/human connection”. An overwhelming amount of evidence showing the deleterious health effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals has been gathered. Increasingly, opinion pieces are being published that connect scientific knowledge regarding endocrine-disrupting chemicals and its application to public health policy, and in some countries a few regulatory actions have been implemented. In this Perspective, we address the gap between scientific knowledge and its application towards public and environmental health policy from a personal historical perspective derived from our serendipitous discovery of oestrogenic activity in plastic that led to our participation at the foundational event of the endocrine disruption field, the Wingspread Conference. The CLARITY study is also discussed.

From Rachel Carson to Theo Colborn

The publication of Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring, in 1962 is considered a watershed moment regarding the awareness of the deleterious consequences of human actions on the ecosystem. Her book examined the consequences of widespread pesticide use and triggered the development of environmental activism and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the USA. Carson assumed that cancer is a direct result of pesticide exposure but considered that it can also arise indirectly via liver alterations that result in increased levels of oestrogen. In 1979, almost two decades after Carson’s pioneering work, John McLachlan, then at the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), organized the first of a series of conferences entitled “Oestrogens in the Environment” at Research Triangle Park, NC, USA. At this conference, emerging problems caused by various environmental pollutants (such as pesticides with oestrogenic activity), the widespread use of oral contraceptives and the discovery of diethylstilbestrol syndrome were thoroughly discussed1.

In the decade that followed this conference, Theo Colborn and her collaborators conducted a survey on the state of the environment in the Great Lakes area. They observed that young animals exhibited alterations that eventually caused premature death or abnormal development. These alterations included metabolic changes that manifested as ‘wasting’. Animals affected by wasting were lethargic, lost their appetite, experienced weight loss and died prematurely. Organ damage, which is more subtle than wasting, also occurred. For instance, Colborn and her colleagues observed thyroid and heart problems, porphyria, abnormal metabolism of iron, reduced levels of vitamin A in critical tissues, male birds growing ovarian tissue, female birds growing excessive oviduct tissue, male fish not reaching full sexual maturity and fish exhibiting hermaphroditism. Birth defects and behavioural changes were also observed by the team2. Colborn wondered whether these devastating health effects were the consequence of the lowering levels of oestrogenic chemicals, such as DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) and PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), following the introduction of regulations by the EPA in the 1970s. This observation suggested that the residual action of the banned chemicals only became apparent once the initial effects of their widespread use on mortality had dissipated following several years of their use being regulated. If indeed this was the case, there was nothing else to do but wait for a further lowering of these levels. Instead, an accident in our laboratory at that time revealed that there were xenoestrogens in the environment that were yet to be regulated3.

‘Unregulated’ oestrogens

To provide context, a brief historical account will be helpful. While working on oestrogen regulation of cell proliferation in breast epithelial MCF7 cells, we concluded that oestrogen was not stimulating cell proliferation in these cells. Instead, the protagonist of this phenomenon was an inhibitor present in human serum that affected these oestrogen target cells4; oestrogens affected cell proliferation by neutralizing this inhibitor rather than by directly affecting cell proliferation. These results inspired us to postulate that all cells, both in unicellular and multicellular organisms, proliferate and move constitutively when in the presence of adequate amounts of nutrients5–7. Based on this principle, starting in 1986, we proceeded to purify the blood-borne inhibitor4.

During this purification process, fractions were being tested both in the presence and the absence of oestrogen; the fractions containing inhibitory activity resulted in a statistically significant decrease in cell number, while oestrogen supplementation overrode the inhibition. Unexpectedly, in 1987, all the cultures of breast epithelial oestrogen target cells (MCF7 and T47D cell lines) proliferated maximally. It took us 4 months of systematic substitutions to track the contamination to the plastic tubes where the human serum that did not contain oestrogen was being stored. After 1 year of additional work, we identified nonylphenol as the contaminant that caused the cell proliferation3. Nonylphenol, as well as other oestrogenic alkylphenols, is used as an antioxidant and in the synthesis of non-ionic detergents8. Humans are directly exposed because some of these detergents are used as spermicides and in hair and skin care products. Additionally, the degradation products of these detergents have been found in river water8. Based on this finding, we were invited to participate at the first Wingspread Conference, where the term ‘endocrine disruptor’ was coined9,10.

The endocrine disruption concept

Colborn, then a fellow of the W. Alton Jones Foundation, brought together a group of 21 scientists to discuss the observations she and her colleagues had made on the state of the environment in the Great Lakes area; the conference took place at the Wingspread Conference Center, Racine, WI, USA, in July 1991. The opening statement of the Wingspread Declaration asserted that “Many compounds introduced into the environment by human activity are capable of disrupting the endocrine system of animals, including fish, wildlife, and humans. Endocrine disruption can be profound because of the crucial role hormones play in controlling development”11. To address this global concern, a number of issues were discussed. The first issue addressed by the participants of the Wingspread meeting was the link between alterations described in wildlife and the iatrogenic syndrome caused by the synthetic oestrogen diethylstilbestrol12. Daughters born to mothers who were given diethylstilbestrol during pregnancy to prevent miscarriage showed increased rates of vaginal clear cell adenocarcinoma, various genital tract abnormalities, abnormal pregnancies and altered immune responses12,13. Both sons and daughters exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol developed congenital anomalies of their reproductive system and had reduced fertility later in life14. The effects observed in humans exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero were similar to those found in wildlife and laboratory animals exposed to xenoestrogens, which suggests that humans are also at risk when exposed to the same environmental hazards as wildlife15 (FIG. 1).

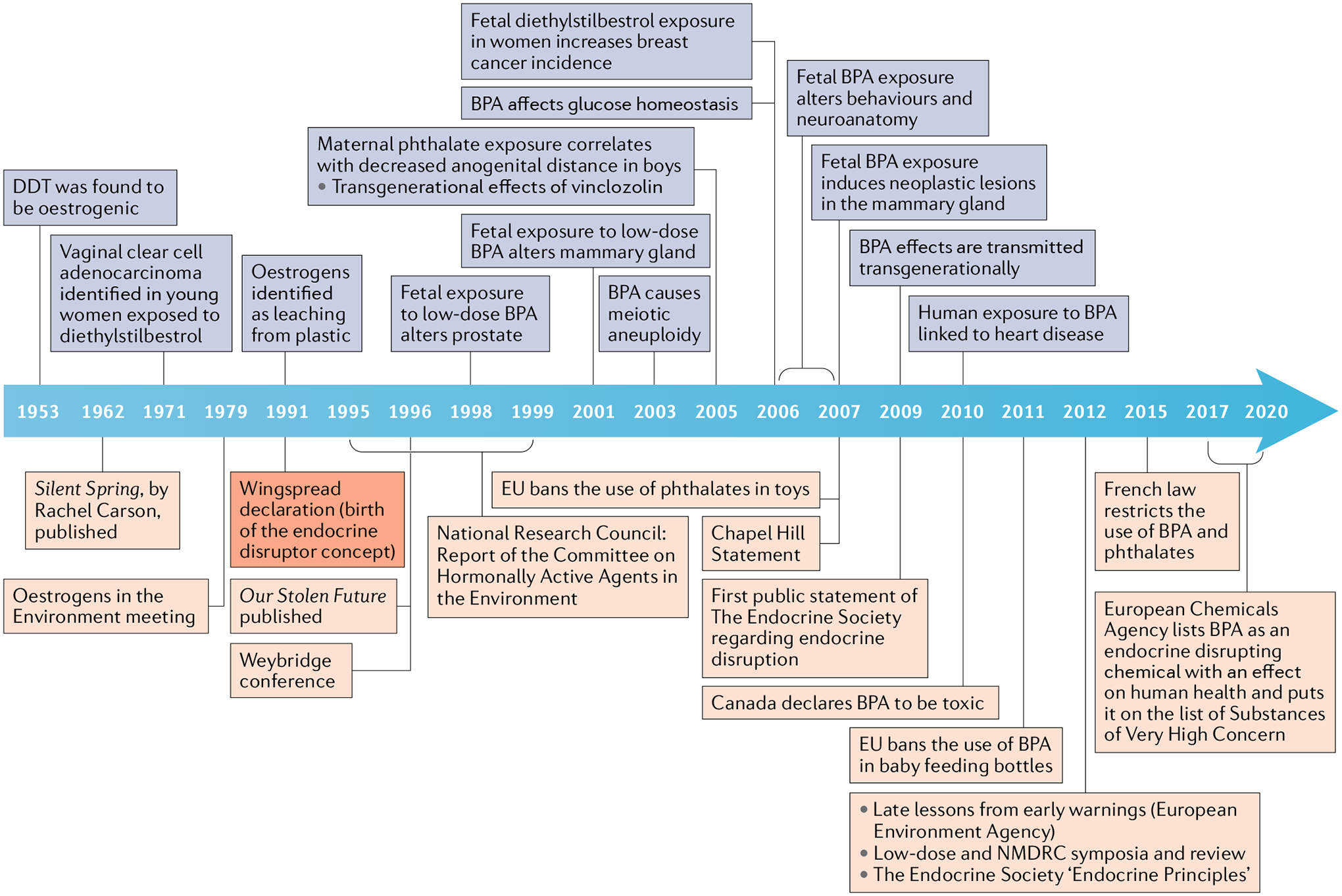

Fig. 1 |. A timeline of the concept of endocrine disruptors.

Blue squares represent scientific findings, such as the oestrogenicity of dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) in 1953, that led to the concept of endocrine disruptors at the Wingspread Conference in 1991. From 1991 on, blue squares show discoveries that buttressed, expanded and refined the concept and its theoretical and practical implications. Orange squares represent the events that mark the conceptual development of endocrine disruptors regarding environmental and public health and the regulatory consequences of conceptual and experimental advances. The Weybridge conference and the National Research Council Report represent the earlier assessments of the endocrine-disrupting chemicals problem from the European and US perspectives, respectively. The Chapel Hill Consensus Statement is the first global assessment of the toxicity of bisphenol A (BPA) in the context of endocrine disruption.; EU, European Union; NMDRC, non-monotonic dose–response curve.

Equally important was the issue of human exposure levels, which were then unknown. To address this issue, the participants focused on the physiological effects of hormones during normal development. In polytocous (litter bearing) animals such as rodents, the intrauterine positioning of fetuses has marked effects on anatomical, functional and behavioural outcomes later in life. The sex of the neighbouring fetuses results in small local differences in sex steroid levels during fetal life, thus revealing that small physiological variations of hormone levels during morphogenesis have measurable consequences in the adult phenotype. For example, in several rodent species, a female fetus positioned between two other female fetuses has earlier vaginal opening, earlier age at first oestrus and is more likely to be chosen by a male than other rodents16, while a female fetus between two male fetuses tends to show masculinized anatomical, physiological and behavioural traits in adulthood17,18. Knowing the levels of exposure to hormonally active chemicals in the general population was deemed crucial because we expected that they were lower than those affecting wildlife exposed to DDT or of humans exposed occupationally to pesticides19.

The Wingspread statement also made recommendations about the type of research needed to understand the problem and to assess the effect in human populations. Many of the participants were concerned that the then current toxicological tests used by regulatory agencies assessed acute toxicity, mutagenicity and carcinogenicity; that is, end points that were likely to miss most endocrine disruptors (EDs), given that they are seldom mutagens10. The statement also made it clear that new methods to detect and measure these types of toxicants needed to be developed11 (BOX 1). Thus, we adapted the assay for the inhibitor in serum (described in a previous section) to screen for suspected oestrogenic substances and uncovered oestrogenic activity in multiple environmental contaminants that are produced in large volumes20. This assay is now known as the E-SCREEN assay21.

Box 1 |. Wingspread foundational concepts.

Endocrine disruptors are chemicals in the environment that have hormonal activity, and, unlike DDT and PCBs, their use is unregulated.

Low doses matter: a tiny difference within the physiological range has phenotypic consequences.

The fragile fetus: the organism is most vulnerable as it is developing.

What is bad for wildlife, is bad for humans. Theoretically supported by common evolutionary ancestry, this concept is clearly illustrated by the similarity of the diethylstilbestrol syndrome in humans and rodents. The diethylstilbestrol ‘experiment’ in humans shows that hormones in the wrong place at the wrong time produce irreversible adverse effects — some of which are similar to those observed in wildlife. This observation illustrates the wildlife–human connection evoked in the title of the conference.

The regulatory focus on the mutagenicity and carcinogenicity of chemicals will lead to malformations and functional deficits caused by endocrine disruptors being overlooked.

Hence, new tools need to be developed to identify these chemicals and for biomonitoring populations.

DDT, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane; PCBs, polychlorinated biphenyls.

The main conceptual themes

The main concepts invoked in the Wingspread statement were further explained by Colborn and colleagues10. Most of the foundational concepts of endocrine disruption were already uncontroversial in endocrinology. Furthermore, the reliability of these concepts is demonstrated by almost three decades of peer-reviewed research following the Wingspread Conference (FIG. 1). In this regard, the Endocrine Society published its first scientific statement in 2009 addressing the threat posed by EDs and “advocating involvement of individual and scientific society stakeholders in communicating and implementing changes in public policy and awareness”22. An updated statement was published in 2015 (REF.23).

Defining endocrine disruption

The Endocrine Society adopted a succinct definition of an ED as “an exogenous chemical, or mixture of chemicals, that interferes with any aspect of hormone action”24. This definition has the virtue of brevity and has the advantage of not conflating the concept of interfering with hormone action with that of producing adverse effects.

One endocrine disruptor, many targets

The specificity of natural hormones is not absolute. For instance, high doses of androgens produce a positive effect on the uterotropic assay, which was traditionally used to determine whether a compound has oestrogenic properties25. Hence, it is not surprising that EDs might affect various targets. For example, xenoestrogens mimic the effects of ovarian oestrogens but they also produce additional endocrine effects. Among the xenoestrogens, bisphenol A (BPA) is not only an oestrogen agonist but at high doses interferes with thyroid hormone action26,27. Additionally, for some end points mediated by oestrogen receptors, the effects of oestradiol and BPA are different, if not opposite28,29. These differences in the effects of various oestrogens should not be used by regulators to dismiss the effects of xenoestrogens that differ from those of the positive control (usually a steroidal oestrogen such as ethinyl oestradiol) as being due to chance30. Instead, these different effects should be taken seriously as they provide an opportunity to uncover physiological regulatory processes31.

Windows of susceptibility

EDs can affect health at any and all life stages. However, the effects of exposure during embryonic and fetal development are generally more deleterious than the effects of exposure at later life stages because the organism is more vulnerable during organogenesis; these so-called organizational effects are mostly irreversible32. By contrast, activational effects seem to be mostly reversible. For example, occupational exposures to oestrogenic chemicals might result in azoospermia and reduced libido, effects that recede after cessation of exposure19. However, a clear distinction between activational and organizational effects is blurred in some cases. For instance, dams exposed to low doses of BPA during pregnancy develop glucose intolerance and altered insulin sensitivity several months after delivery. In this case, the deleterious effects, unlike activational effects, manifest several months after cessation of exposure33.

Epidemiological studies have found positive correlations between exposure to EDs such as BPA and obesity and heart disease34. Regarding cancer, diethylstilbestrol exposure during pregnancy increases the incidence of breast cancer in the same age range in which these cancers manifest in the general population35, and the daughters of these women have an increased risk of breast cancer at 40 years of age and beyond36. Exposure to DDT also results in an increase in the incidence of breast cancer that manifests 40 years after exposure; of note, the incidence is higher in those exposed perinatally than in those exposed later in life37.

As the endocrine system regulates multiple functions, including growth, development and metabolism, it is expected that the syndromes produced by exposure to EDs will be complex and include direct and indirect effects. For instance, some EDs increase the risk of obesity; pubertal timing is affected by obesity, and, consequently, exposure to EDs might indirectly increase the risk of breast cancer (early onset of puberty is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer)23. Additionally, EDs might also alter the whole hormonal milieu, thus affecting many reproductive tissues simultaneously38.

Dose matters

EDs, like endogenous hormones, are active at low concentrations and doses, exhibit non-monotonic dose–response curves (NMDRCs) and can act additively with endogenous hormones and other EDs. In spite of these many similarities, some unexpected results have been obtained when assessing the effect of EDs using standard toxicological tests. For example, exposure to xenoestrogens during fetal development in mice produces effects at much lower doses than those required in vitro or in the standard toxicological test, the uterotropic assay39. Various low dose effects have now been clearly mapped to extranuclear receptors such as ERα, ERβ and GPR30 (REF.31).

Non-monotonicity.

Before the Wingspread Conference, it was already known that hormones often exhibit NMDRCs. That is, a non-linear relationship exists between dose and effect that is characterized by a change of sign of the slope of the curve within the range of doses examined. This feature is illustrated by the proliferative effect of oestrogens40 and androgens, which is biphasic; namely, at lower doses the net effect is more cells, while at higher doses, the effect is a lower cell number41,42. These two effects are mediated by distinct processes that can be separated from each other in an experimental setting41–43; that is, the NMDRC is a composite of two or more monotonic curves. Not surprisingly, EDs also exhibit NMDRCs44–46. For example, BPA and bisphenol S (BPS) are potent oestrogens when acting via extranuclear ERα, ERβ and GPR30. The NMDRC that BPA and BPS elicit in pancreatic β-cells could be attributed to the fact that the different components of the curve are mediated by distinct pathways involving different receptors31,46.

Additive effects.

Experimental studies traditionally investigate chemicals singly because this is the most straightforward way to learn about them without worrying about how to deal with complex interactions. However, determining the effects of simultaneous exposure to combinations of chemicals is of the utmost relevance because humans, as well as wildlife, are usually exposed simultaneously to a multitude of EDs47. In fact, owing to the substantial knowledge obtained using traditional studies, effects of mixtures are now being assessed in experimental models48 and in epidemiological studies49.

Same hormone but different effects.

In addition to non-monotonicity, which refers to effects of different doses administered during a similar period, natural hormones produce dissimilar effects depending on whether they are administered in a single dose (acute effect) or continuously (chronic effect). For example, a single oestrogen dose induces a wave of cell proliferation on the luminal epithelium of the uterus of ovariectomized rats, while continuous administration first induces cell proliferation and later inhibits further proliferation50. Similarly, androgens administered to a castrated male rat resulted in a proliferative effect, and later promoted quiescence51,52.

Moreover, the same hormone can produce dissimilar and even contrary effects in different targets or in the same target at different times53. Additionally, a hormone might affect different tissues when administered to animals during different developmental stages. For example, a single oestradiol dose results in increased mitotic activity both in the lamina propria and in the epithelium of the endometrium of immature rats, while in mature ovariectomized rats the increased mitotic activity occurs exclusively in the epithelial compartment54,55.

Another important factor is the velocity of change of the hormone level. A fast increase in oestradiol levels during the pre-ovulatory period triggers a positive feedback response and luteinizing hormone release, which leads to ovulation56. By contrast, constant, low levels of oestrogen generate a negative feedback57,58. Additionally, in hormone-sensitive neoplastic tissues, the same hormone might have proliferative or inhibitory effects, depending on the mode of delivery. For example, the cyclic activity of the ovary is needed for the development of mammary tumours induced by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a] anthracene (DMBA), but constant high levels of oestrogens inhibit tumour formation59. It is noteworthy that synthetic oestrogens such as diethylstilbestrol can increase the propensity to develop breast cancer35,60, inhibit the development of breast cancer59 and induce regression of breast cancer depending on when the synthetic oestrogen is administered61,62. The same exposure to diethylstilbestrol can trigger different effects in different organs within the same individual. Some women treated with diethylstilbestrol to induce breast cancer regression develop endometrial carcinomas63, and men treated with diethylstilbestrol to induce prostate cancer regression can develop gynaecomastia and, less frequently, breast cancer64.

In sum, the non-monotonicity and the contextuality of the response to hormones should be taken into consideration when evaluating the effect of EDs. Responses to hormone agonists should not be expected to be monotonic or similar to responses to the natural hormones they mimic, regardless of the age at exposure, or the duration and type of exposure.

New developments since Wingspread

A documentary film, “Assault on the Male” (producer Deborah Cadbury, BBC series Horizon) that was released in 1993 was one of the first films dedicated to the topic of EDs. It realistically conveyed the state of the field 2 years after Wingspread. The central theme was the alterations in male reproduction being observed in humans and wildlife and it posited the hypothesis that this outcome was due to the deleterious effects of EDs. Three years later, Our Stolen Future, a book by T. Colborn, D. Dumanoski and J. P. Myers, which is often compared to Silent Spring, made a persuasive case about the ED problem and its probable consequences65 (FIG. 1). Since then, the scientific literature on the subject has grown exponentially, revealing additional EDs and the related health effects anticipated by the Wingspread participants. For example, perinatal exposure of female rodents to BPA results in similar effects to those resulting from prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol in women and female rodents (TABLE 1). Similar effects were obtained in male mice regarding behavioural66, reproductive, neoplastic and metabolic end points (alterations of the male genital organs, decreased daily sperm production, and increased propensity for prostate cancer, obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus)67–69.

Table 1 |.

Representative examples of affected targets resulting from xenoestrogen exposure

| Affected target | BPA | Diethylstilbestrol |

|---|---|---|

| Onset of puberty | Earlier onset in mice103,104 | Accelerated vaginal opening in mice105 |

| Oestrous cycles | Altered cycling, early cessation in rats106 | Altered oestrus or menstrual cyclesa,105 in rats, mice and humans, early menopausea,107 |

| Hormone profiles | Adverse thyroid hormone action in rats26, altered hormone receptor expression in the uterus in mice108, altered LH levels in mice39 | Altered plasma levels of thyroxine, TSH and LH, altered thyroid functions in rats109, altered pituitary response to GnRH in ratsb,110 |

| Response to oestrogens | Altered sensitivity in mice111,112 | Altered response in mice113 |

| Obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolism | Obesogenic action in miceb,114, altered metabolites in mice115, altered metabolome in mice and rats90,116, diabetogenic action in miceb,91,117 | Obesogenic action in mice23 |

| Behaviour | Impaired neurological activity in mice118, hyperactivity, increased repetitive behaviours in rodents91 | Increased aggressive behaviour in mice119 |

| Reproductive tract morphogenesis | Altered oogenesis120, increases in ovarian, vaginal and uterus abnormalities in mice108 | Increases in polycystic ovaries, ovary-independent vaginal cornification, vaginal adenosisc, malformations of the oviduct, uterus and cervixc,105 |

| Mammary gland morphogenesis | Altered mammary gland development121,122, altered response to oestradiol112, altered response to progesterone in mice112 | Altered hormone response123, altered development in mice124 |

| Fertility or fecundity | Decreased fertility and fecundity (decreased litter numbers and pup numbers)45, impaired ovulation125 | Decreased fertility105, decreased pup numbers, increased time to first litter in mice126 |

| Mammary neoplasms | Carcinoma in situ127, adenocarcinoma in rats128 | Adenocarcinomasc,129 |

| Reproductive tract neoplasms | Preneoplastic and/or neoplastic lesions in ovary and reproductive tract in mice130 | Carcinomas in mice126, clear cell carcinoma of the vaginaa |

| Transgenerational transmission | Impaired social recognition131, reduced reproductive capacity in mice132 | Increase in reproductive tract abnormalities, neoplasms in mice126 |

The effects listed have been observed after fetal or perinatal exposure to either BPA or diethylstilbestrol. All effects listed are found in rodent studies except where indicated. BPA, bisphenol A; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone.

Effects in women fetally exposed.

Effects in male mice.

Effects in both women and rodents.

In spite of the many well-documented deleterious effects of BPA (TABLE 1), there has been little translation into regulatory action. In the next sections, we discuss why this might be, and we identify two types of explanation, one theoretical and the other, for lack of a better word, institutional.

Theoretical inconsistencies

The ED concept emerged simultaneously with important theoretical developments in the biological sciences. Since the 1950s, the molecular biology revolution has updated the metaphorical status of the organism from a machine to that of a computer70; these developments were due to the introduction of metaphors loosely based on the mathematical theories of information. Philosophers and theoreticians repeatedly warned of the inadequacy of these metaphors71. The ascent of the disciplines known as ecological developmental biology (eco-devo) and evolutionary developmental biology also brought a critique of the genocentric views in biology72. Eco-devo not only brought to light the role of the environment as a co-maker of phenotypes, but in doing so explicitly rejected the idea of a genetic developmental programme, or the supremacy of genetic explanations over functional ones. In other words, there is no ‘central control’, genes do not hold a privileged causal role; instead, there is redundancy and plasticity. Additional theoretical developments include strong arguments to abandon metaphors equating organisms and cells with machines, and the validity of mechanisms (particularly molecular ones) as the only type of explanation in biology73,74.

Owing to the strong theoretical frame of evolutionary biology, the introduction of novel concepts, such as the role of epigenetic inheritance, has generated wide-ranging discussions (and disagreements) about which concepts should be kept, which need modification and which have to be rejected75. By contrast, in organismal biology, the lack of theoretical engagement by the mainstream research community led to the coexistence of conflicting postulates, whereby lack of fit between data and presuppositions could easily be fixed by ad hoc additions. For example, the role of the environment as a determinant of phenotype is metaphorically referred to as ‘reprogramming’ even by those that are aware that development is not a programme; a much more neutral term for the induction of developmental plasticity is ‘environmentally elicited’76.

Although frequently ignored by biologists, philosophical stances matter. Thus, it has been to the delight of those who would like to delay regulatory action regarding EDs that some biologists have proposed the development of adverse outcome pathways77,78 that will connect molecules in a linear path through mechanisms to adverse effects. However, linearity is uncommon in biological systems; their phenomena are multicausal and circular owing to feedbacks and history, namely ontogeny and evolution79. Fortunately, a plausible alternative to this theoretically flawed stance exists that has an immediate practical consequence. It consists of putting mechanism aside and instead using key characteristics (KCs) as the basis for hazard identification. In other words, KCs would be the “common features of hormone regulation and action that are independent of the diversity of the effects of hormones during the life cycle”. Additionally, “KCs of EDs are the functional properties of agents that alter hormone action”, and “… KCs are agnostic with respect to current or future knowledge of downstream health hazards and mechanistic pathways”80. Although the proponents of this alternative did not offer theoretical arguments on the validity of mechanistic pathways, their approach had the virtue of not depending on stances of dubious scientific legitimacy and, most importantly, could be applied immediately for rigorous regulatory purposes. This pragmatic solution does not make the resolution of theoretical issues superfluous or less timely.

The conceptual developments brought about by eco-devo biology and evolutionary developmental biology were helpful in providing a loose theoretical frame that allowed scientists to circumvent the hindrances caused by the misuse of the notions of programme, information and mechanism. However, the elaboration of solid principles for a theory of organisms81,82 that spans the complete life cycle would certainly provide an adequate framework for experimentation and also would help to exclude unreasonable regulation-hindering arguments developed by the practitioners of the so-called regulatory science.

Regulation and the BPA issue

Government regulatory agencies in the USA and Europe, such as the FDA and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), systematically claimed that there was not enough evidence for regulatory action or that the evidence indicated that BPA was safe at the usual levels of exposure. These conclusions were reached mostly owing to a biased choice of datasets that favoured those researchers using good laboratory practice (GLP) protocols83. GLP was created to make it difficult to hide inconvenient data by those interested in promoting the use of the chemical being tested. These GLP studies use classic toxicological end points that are inappropriate for detecting the effects reported by academic laboratories84. Owing to the contradiction between the opinion of these two agencies (FDA and EFSA) and the evidence from animal studies conducted by scientists in academic institutions revealing that exposure to environmentally relevant levels of BPA results in a constellation of deleterious effects, France promulgated legislation banning the use of BPA in food contact materials (Law no. 2010-729 of 30 June 2010 modified by Law no. 2012-1442 of 24 December 2012 (INERIS 2015)). Simultaneously, studies sponsored by ANSES, the French equivalent of EFSA and the FDA, identified BPA as an ED by using both academic and GLP studies85 (FIG. 1).

As a result of this conflicting situation, in 2013 the FDA decided to conduct a toxicological evaluation of BPA. The NIEHS proposed that academic researchers could participate in the study by obtaining the organs of interest from the GLP study and using them to test the end points that prompted academic researchers to claim that BPA induces serious health effects. This concept materialized as the Consortium Linking Academic and Regulatory Insights on Bisphenol A Toxicity (CLARITY-BPA), a collaboration between academic and federal government scientists, organized by the National Toxicology Program, NIEHS and the FDA National Center for Toxicological Research (NCTR)86. This research consortium was “expected to significantly improve the interpretation of the wealth of data that is being generated by all consortium partners, including the characterization of the dose response of the effects observed and their interpretation in an integrated biological context”87.

The CLARITY study

The CLARITY core study was conducted in rats and had two experimental branches, with exposures started at gestational day 6 in both studies. In the so-called stop dose branch, which aimed to detect effects due solely to developmental exposure, exposure ended at postnatal day 21. The other branch was called ‘continuous’, and exposure ended when the animals were killed (interim 1 year, final 2 years). The continuous branch represents a typical design for regulatory studies aiming to detect classic toxicants, not EDs. From an endocrinological perspective, these two regimens are not comparable. As alluded to already, according to whether the exposure is acute or chronic, and depending on the timing of exposure, the same hormone can produce different effects in the same organ or tissue.

The objective of the academic studies in the CLARITY consortium was mostly to determine whether, in this GLP set-up, the results previously obtained could be reproduced and thus verified. They assessed the prostate, urinary tract, ovary, mammary gland, brain and heart. The academic studies within CLARITY confirmed previous academic studies; they found non-linear dose–responses, and some were clearly non-monotonic (sometimes U-shaped (prostate)88 or W-shaped (ovary)89). The largest and sometimes only effect in these studies was observed at the lowest dose, which suggested that BPA could have effects at lower doses than the ones tested in the CLARITY study (the lowest dose used in the CLARITY study was 2.5 μg/kg body weight per day). In fact, some earlier academic studies found effects at 25 ng/kg per day and 250 ng/kg per day18,39,90,91. Additionally, statistical correlations among the different CLARITY academic studies revealed patterns of effects across the organs of the same sets of animals, thus showing that contrary to the NCTR conclusions, low-dose effects were not random, and again, the largest effects consistently occurred at the lowest doses89.

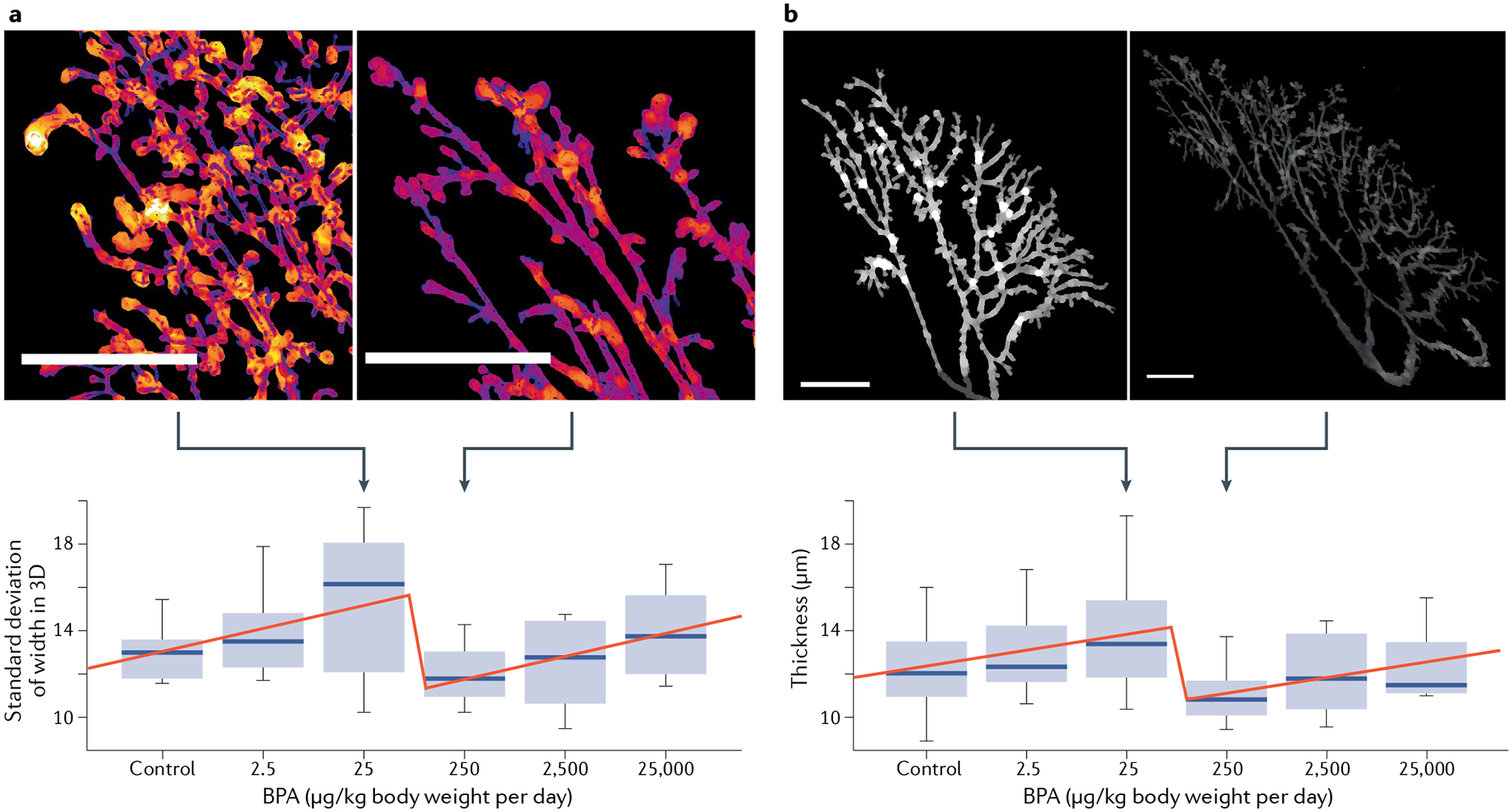

An excellent discussion of the CLARITY study has already been published in this journal92. We only focus on an academic study on the NMDRC of BPA obtained in specimens from the CLARITY study; it was not available at the time of the previous discussion of the CLARITY study. This new evidence refutes the interpretation of the core study provided by the FDA. It focuses on the effects of BPA on the structure and growth of the ductal tree of the rat mammary gland and, most importantly, whether these effects reveal a NMDRC (a controversial issue among toxicologists in regulatory agencies). For this purpose, a novel software tool was developed for non-supervised, automatic evaluation of quantifiable aspects of the mammary ductal tree. This analysis of specimens from postnatal day 21 revealed a NMDRC of BPA effects with a breaking point (an abrupt change in direction of the dose–response curve) between the 25 μg/kg per day and 250 μg/kg per day doses for most of the 91 measurements93 (FIG. 2).

Fig. 2 |. Non-monotonic responses to BPA in the mammary gland of female 21-day-old rats.

Dose–response curves depicting the breaking point between the 25 μg bisphenol A (BPA) and 250 μg BPA per kilogram body weight per day within two representative end points in the mammary gland. Higher values occur before the break (250 μg BPA) and lower values after the break (25 μg BPA) (scale bars represent 2 mm). a | Standard deviation of width (mean variation in ductal thickness). A low value indicates more tubular structures. A high value indicates more budding structures. b | Thickness (average local thickness of the gland ductal tree). Figure adapted from Environmental Health Perspectives with permission from Montévil et al.93.

This result was confirmed by a global statistical analysis of both the stop and continuous dose animals at postnatal day 90 and at 6 months of age. Additionally, the effects of BPA and ethinyl oestradiol, the positive control, were different for several features. This study provided the strongest evidence of non-monotonicity within the CLARITY study, thus validating the theoretical stance in endocrinology regarding the prevalence of NMDRCs. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that the default mathematics to show causation should not always be to find a linear response, as expected by the FDA toxicologists, but when the response is not linear, to show the prevalence of a specific non-monotonic pattern, here a breaking point between 25 μg/kg per day and 250 μg/kg per day doses. Moreover, as for linear (monotonic) responses, knowledge of the molecular mechanisms underlying each one of these NMDRCs is not needed to recognize the existence of this well-described statistically significant phenomenon93–95. Therefore, lack of a mechanistic explanation should not be used to dismiss NMDRCs obtained with statistically appropriate methods in regulatory science, as has been done previously30.

Returning to the core study30, it showed various statistically significant effects related to disease; the most critical of them was that BPA induced mammary cancers at the lowest dose, thus confirming experiments conducted in academia. Unfortunately, the interpretation of the core study by the NCTR did not take account of the principles of endocrinology. By dismissing these empirically supported concepts of non-monotonicity, the authors of the study concluded that as the responses within the continuous dose and stop dose arms and the responses within and across tissues were all inconsistent, the plausibility of the relationship between most of the lesions and BPA treatment could be questioned30. Objectively, this conclusion does not appear to be based on scientific reasons. That is, the finding of inconsistent responses means that the findings did not agree with the concept that linearity is the only correct mathematics of causality, that all oestrogens do exactly the same thing and that a longer exposure should produce at least the same result as a shorter exposure, not a less severe outcome. All these concepts are invalid in endocrinology. To overcome this resistance by the NCTR, we should make explicit the principles and theoretical frameworks that guide research in endocrinology and developmental origins of adult disease. Otherwise, by putting the mechanistic cart before the phenomenological horse, institutions created to protect the public might adopt measures to postpone much needed regulation94.

Personal experience

Returning to our personal experience, our serendipitous finding of oestrogens in plastic motivated us to study endocrine disruption of the developing fetus. This research project produced results that led us, again, to question the assumptions that originally guided our research; namely, those that dominated research on development and cancer during the second half of the past century, a period during which reductionism became hegemonic and the practice of molecular biology thrived.

During this period, fetal development has been interpreted as a programme that is mostly impervious to environmental modulation. In parallel, cancer was considered a cell-based problem caused by mutations in genes that allegedly controlled cell proliferation. The carcinogenicity of diethylstilbestrol and other EDs motivated our re-appraisal of these two dogmas, namely, the developmental programme and the somatic mutation theory96. In practical terms, we realized that for the good of our continuing activity as experimental biologists, we needed to examine the inconsistencies of the theoretical frame under which research was conducted at the intersection of developmental origins of adult disease, EDs, reproduction and cancer.

We began by studying endocrine disruption using the principles of eco-devo biology, whereby the embryo is considered an open system and the environment a co-determinant of phenotypes. As development is about ‘becoming’, it is better served by an organicist explanatory perspective rather than by a reductionist and/or mechanistic perspective fixed on ‘being’70. Under the eco-devo framework, hormones act as morphogens97,98.

Using the framework provided for these principles, we developed the tissue organization field theory of carcinogenesis, which posits that cancer is a tissue-based disease caused by various deleterious exposures that interfere with the reciprocal communication between cells in the morphogenetic field and between cells and their surrounding extracellular matrix. From this perspective, cancer is seen as development gone awry99. In this context, exposures to EDs will do the most harm when occurring during organogenesis. In turn, this understanding led us to re-examine the broad picture of developmental biology and propose principles for a Theory of Organisms that addresses the entire life cycle81,82. This theory is compatible with and complements evolutionary theory.

Theories have a practical purpose: to construct objectivity and to determine what can be observed; in our case, our theoretical work led to successful mathematical modelling and robust explanations of developmental and endocrinological processes100,101. When a theory is not vague, it also permits us to decide when to reject an interpretation or drop a hypothesis. Our theoretical work allowed us to deal with this type of problem and restrained us from looking for ad hoc explanations, or from using terms loaded with theoretical baggage that when made explicit are incompatible with the accepted theoretical framework. This positive experience emboldens us to propose a future direction for the field of endocrine disruption: to construct a rigorous and explicit theoretical frame. This approach will not only facilitate research by determining which are the proper postulates and observables, but it would also serve to unmask and overcome spurious arguments intended to delay regulation.

Conclusions

Sufficient data have been gathered on the deleterious effects of EDs to warrant immediate action to decrease human exposure to these agents by means of a well-thought-out and enforceable public health policy. Fortunately, in the particular case of BPA, the enormous body of evidence gathered, mostly through studies in academia, resulted in BPA being listed as an ED by the European Chemicals Agency and BPA being placed in the Candidate List of substances of very high concern owing to its reproductive toxicity properties. Undoubtedly, this is a move in the right direction and should be extended by additional regulation. To speed up this process, we propose to concentrate on principles and theories. The precautionary principle is already being invoked in countries of the European Union; its worldwide application as a guide for a protective public and environmental health policy could immediately help to reduce risk by curtailing exposure to EDs. Again, on 14 October 2020, the European Commission published a comprehensive chemicals strategy for sustainability. It proposes, among other things, to “establish legally binding hazard identification of endocrine disruptors, based on the definition of the WHO, building on criteria already developed for pesticides and biocides, and apply it across all legislation”, and to “ensure that endocrine disruptors are banned in consumer products as soon as they are identified”102. Regarding theories, the field of endocrinology in general, and of EDs in particular, would benefit from theoretical work leading to the identification of fundamental principles, a notion that has started to be discussed and that deserves further development24,84. This theoretical work is greatly needed, on the one hand to guide experimental work for the sake of finding accurate explanations of phenomena, and on the other to perform regulatory science, informed by a proper theoretical framework. We expect that endocrinologists, now armed with the proper principles and a clear understanding of when ‘enough is enough’, could help to overcome the delaying tactics that sooner or later will try to derail the European Commission strategy.

Acknowledgements

We thank V. Bouffard for her insightful reading of this manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge support by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (grants ES030045 and ES026283). The funders had no role in the content of this article, and it does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Competing interests

A.M.S. and C.S. have received travel reimbursements from universities, governments, non-governmental agencies and industry to speak about endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

A.M.S. serves ad honorem/pro bono on two scientific advisory boards. C.M.S. declares no competing interests.

References

- 1.McLachlan JA Estrogens in the Environment (Elsevier, 1980). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colborn T & Liroff RA Toxics in the Great Lakes. EPA J 16, 5–8 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soto AM, Justicia H, Wray JW & Sonnenschein C p-Nonyl-phenol: an estrogenic xenobiotic released from “modified” polystyrene. Environ. Health Perspect 92, 167–173 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonnenschein C, Soto AM & Michaelson CL Human serum albumin shares the properties of estrocolyone-I, the inhibitor of the proliferation of estrogen-target cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol 59, 147–154 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soto AM & Sonnenschein C Regulation of cell proliferation: the negative control perspective. Ann. NY Acad. Sci 628, 412–418 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sonnenschein C & Soto AM The Society of Cells: Cancer and Control of Cell Proliferation (Springer, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soto AM, Longo G, Montévil M & Sonnenschein C The biological default state of cell proliferation with variation and motility, a fundamental principle for a theory of organisms. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol 122, 16–23 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markey CM, Michaelson CL, Sonnenschein C & Soto AM in Endocrine Disruptors - Part I (ed Metzler M) 129–153 (Springer, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colborn T & Clement C Chemically Induced Alterations in Sexual and Functional Development: the Wildlife/Human Connection (Princeton Scientific, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colborn T, vom Saal FS & Soto AM Developmental effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in wildlife and humans. Environ. Health Perspect 101, 378–384 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bern HA et al. in Chemically Induced Alterations in Sexual and Functional Development: The Wildlife/Human Connection (eds Colborn T & Clement C) 1–8 (Princeton Scientific, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbst AL, Ulfelder H & Poskanzer DC Adenocarcinoma of the vagina: association of maternal stilbestrol therapy with tumor appearance in young women. N. Engl. J. Med 284, 878–881 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noller KL et al. Increased occurrence of autoimmune disease among women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. Fertil. Steril 49, 1080–1082 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bern HA in Chemically-Induced Alterations in Sexual and Functional Development: The Wildlife/Human Connection (eds Colborn T & Clement C) 9–15 (Princeton Scientific, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox GA in Chemically Induced Alterations in Sexual and Functional Development: the Wildlife/Human Connection (eds Colborn T & Clement C) 147–158 (Princeton Scientific, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryan BC & Vandenbergh JG Intrauterine position effects. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 26, 665–678 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.vom Saal FS TRIENNIAL REPRODUCTION SYMPOSIUM: Environmental programming of reproduction during fetal life: effects of intrauterine position and the endocrine disrupting chemical bisphenol A. J. Anim. Sci 94, 2722–2736 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vandenberg LN et al. Exposure to environmentally relevant doses of the xenoestrogen bisphenol-A alters development of the fetal mouse mammary gland. Endocrinology 148, 116–127 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guzelian PS Comparative toxicology of chlorodecone (kepone) in humans and experimental animals. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 22, 89–113 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soto AM, Chung KL & Sonnenschein C The pesticides endosulfan, toxaphene, and dieldrin have estrogenic effects on human estrogen sensitive cells. Environ. Health Perspect 102, 380–383 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soto AM et al. The E-SCREEN assay as a tool to identify estrogens: an update on estrogenic environmental pollutants. Environ. Health Perspect 103, 113–122 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diamanti-Kandarakis E et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr. Rev 30, 293–342 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gore AC et al. EDC-2: the Endocrine Society’s second scientific statement on endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Endocr. Rev 36, E1–E150 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zoeller RT et al. Endocrine-dsrupting chemicals and public health protection: a statement of principles from the Endocrine Society. Endocrinology 153, 4097–4110 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armstrong DT, Moon YS & Leung PCK Uterotrophic effects of testosterone and 5à-dihydrotestosterone in intact and ovariectomized immature female rats. Biol. Reprod 15, 107–114 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zoeller RT, Bansal R & Parris C Bisphenol-A, an environmental contaminant that acts as a thyroid hormone receptor antagonist in vitro, increases serum thyroxine, and alters RC3/neurogranin expression in the developing rat brain. Endocrinology 146, 607–612 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fini JB et al. An in vivo multiwell-based fluorescent screen for monitoring vertebrate thyroid hormone disruption. Env. Sci. Technol 41, 5908–5914 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurian JR et al. Acute influences of bisphenol A exposure on hypothalamic release of gonadotropin- releasing hormone and kisspeptin in female rhesus monkeys. Endocrinology 156, 2563–2570 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Speroni L et al. New insights into fetal mammary gland morphogenesis: differential effects of natural and environmental estrogens. Sci. Rep 7, 40806 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camacho L et al. A two-year toxicology study of bisphenol A (BPA) in Sprague-Dawley rats: CLARITY-BPA core study results. Food Chem. Toxicol 132, 110728 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nadal A et al. Extranuclear-initiated estrogenic actions of endocrine disrupting chemicals: is there toxicology beyond paracelsus? J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol 176, 16–22 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phoenix CH, Goy RW, Gerall AA & Young WC Organizing action of prenatally administered testosterone propionate on the tissues mediating mating behavior in the female guinea pig. Endocrinology 65, 369–382 (1959). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alonso-Magdalena P, Garcia-Arevalo M, Quesada I & Nadal A Bisphenol-A treatment during pregnancy in mice: a new window of susceptibility for the development of diabetes in mothers later in life. Endocrinology 156, 1659–1670 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ranciere F et al. Bisphenol A and the risk of cardiometabolic disorders: a systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence. Env. Health 14, 46 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Titus-Ernstoff L et al. Long-term cancer risk in women given diethylstilbestrol (DES) during pregnancy. Br. J. Cancer 84, 126–133 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoover RN et al. Adverse health outcomes in women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. N. Engl. J. Med 365, 1304–1314 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohn BA, Cirillo PM & Terry MB DDT and breast cancer: prospective study of induction time and susceptibility windows. J. Natl Cancer Inst 111, 803–810 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sonnenschein C, Wadia PR, Rubin BS & Soto AM Cancer as development gone awry: the case for bisphenol-A as a carcinogen. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis 2, 9–16 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubin BS et al. Evidence of altered brain sexual differentiation in mice exposed perinatally to low environmentally relevant levels of bisphenol A. Endocrinology 147, 3681–3691 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amara JF & Dannies PS 17β-Estradiol has a biphasic effect on GH cell growth. Endocrinology 112, 1141–1143 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sonnenschein C, Olea N, Pasanen ME & Soto AM Negative controls of cell proliferation: human prostate cancer cells and androgens. Cancer Res 49, 3474–3481 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geck P, Maffini MV, Szelei J, Sonnenschein C & Soto AM Androgen-induced proliferative quiescence in prostate cancer: the role of AS3 as its mediator. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 10185–10190 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soto AM et al. Variants of the human prostate LNCaP cell line as a tool to study discrete components of the androgen-mediated proliferative response. Oncol. Res 7, 545–558 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vandenberg LN et al. Hormones and endocrine disrupting chemicals: low dose effects and non-monotonic dose responses. Endocr. Rev 33, 378–455 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cabaton NJ et al. Perinatal exposure to environmentally relevant levels of bisphenol-A decreases fertility and fecundity in CD-1 mice. Environ. Health Perspect 119, 547–552 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Villar-Pazos S et al. Molecular mechanisms involved in the non-monotonic effect of bisphenol-a on Ca2+ entry in mouse pancreatic β-cells. Sci. Rep 7, 11770 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kortenkamp A, Faust M, Scholze M & Backhaus T Low-level exposure to multiple chemicals: reason for human health concerns? Environ. Health Perspect 115, 106–114 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Isling LK et al. Late-life effects on rat reproductive system after developmental exposure to mixtures of endocrine disrupters. Reproduction 147, 465–476 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pastor-Barriuso R et al. Total effective xenoestrogen burden in serum samples and risk for breast cancer in a population-based multicase-control study in Spain. Env. Health Perspect 124, 1575–1582 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stormshak F, Leake R, Wertz N & Gorski J Stimulatory and inhibitory effects of estrogen on uterine DNA synthesis. Endocrinology 99, 1501–1511 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bruchovsky N, Lesser B, Van Doorn E & Craven S Hormonal effects on cell proliferation in rat prostate. Vitam. Hormones 33, 61–102 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maffini MV, Geck P, Powell CE, Sonnenschein C & Soto AM Mechanism of androgen action on cell proliferation AS3 protein as a mediator of proliferative arrest in the rat prostate. Endocrinology 143, 2708–2714 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soto AM & Sonnenschein C The two faces of Janus: sex steroids as mediators of both cell proliferation and cell death. J. Natl Cancer Inst 93, 1673–1675 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kang YH, Anderson WA & DeSombre ER Modulation of uterine morphology and growth by estradiol-17beta and an estrogen antagonist. J. Cell Biol 64, 682–691 (1975). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martin L, Finn CA & Trinder G Hypertrophy and hyperplasia in the mouse uterus after oestrogen treatment: an autoradiographic study. J. Endocrinol 56, 133–144 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schaison G & Couzinet B Steroid control of gonadtropin secretion. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol 40, 417–420 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bronson FH The regulation of luteinizing hormone secretion by estrogen: relationships among negative feedback, surge potential, and male stimulation in juvenile, peripubertal, and adult female mice. Endocrinology 108, 506–516 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu X, Porteous R & Herbison AE Dynamics of GnRH neuron ionotropic GABA and glutamate synaptic receptors are unchanged during estrogen positive and negative feedback in female mice. eNeuro 4, 1–14 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huggins C, Moon RC & Morii S Extinction of experimental mammary cancer. I. Estradiol-17β and progesterone. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 48, 379–386 (1962). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palmer JR et al. Prenatal diethylstilbestrol exposure and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 15, 1509–1514 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ingle JN, Ahman DL & Green SJ Randomized clinical trial of DES versus tamoxifen in post-menopausal women with advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 304, 16–21 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goldenberg IS Results of studies of the Cooperative Breast Cancer Group 1961–1963. Cancer Chemotherapy Rep 41, 1–24 (1964). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khandekar JD, Victor TA & Mukhopadhyaya P Endometrial carcinoma following estrogen therapy for breast cancer. Report of three cases. Arch. Intern. Med 138, 539–541 (1978). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.O’Grady WP & McDivitt RW Breast cancer in a man treated with diethylstilbestrol. Arch. Pathol 88, 162–165 (1969). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Colborn T, Dumanoski D & Myers JP Our Stolen Future (Penguin, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gioiosa L, Palanza P, Parmigiani S & vom Saal FS Risk evaluation of endocrine-disrupting chemicals: effects of developmental exposure to low doses of bisphenol A on behavior and physiology in mice (Mus musculus). Dose Response 13, 1559325815610760 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Timms BG et al. Estrogenic chemicals in plastic and oral contraceptives disrupt development of the fetal mouse prostate and urethra. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 7014–7019 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.vom Saal FS et al. A physiologically based approach to the study of bisphenol A and other estrogenic chemicals on the size of reproductive organs, daily sperm production, and behavior. Toxicol. Ind. Health 14, 239–260 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ho SM, Tang WY, Belmonte de Frausto J & Prins GS Developmental exposure to estradiol and bisphenol A increases susceptibility to prostate carcinogenesis and epigenetically regulates phosphodiesterase type 4 variant 4. Cancer Res 66, 5624–5632 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Soto AM & Sonnenschein C Reductionism, organicism, and causality in the biomedical sciences: a critique. Perspect. Biol. Med 61, 489–502 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Longo G, Miquel PA, Sonnenschein C & Soto AM Is information a proper observable for biological organization? Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol 109, 108–114 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gilbert SF Developmental plasticity and developmental symbiosis: the return of eco-devo. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol 116, 415–433 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nicholson DJ Is the cell really a machine? J. Theor. Biol 477, 108–126 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nicholson DJ The concept of mechanism in biology. Stud. Hist. Philos. Biol. Biomed. Sci 43, 152–163 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laland K et al. Does evolutionary theory need a rethink? Nature 514, 161–164 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bateson P Developmental plasticity and evolutionary biology. J. Nutr 137, 1060–1062 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ankley GT et al. Adverse outcome pathways: a conceptual framework to support ecotoxicology research and risk assessment. Env. Toxicol. Chem 29, 730–741 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Leist M et al. Adverse outcome pathways: opportunities, limitations and open questions. Arch. Toxicol 91, 3477–3505 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lesne A Multiscale analysis of biological systems. Acta Biotheoretica 61, 3–19 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.La Merrill MA et al. Consensus on the key characteristics of endocrine-disruption chemicals as a basis for hazard indentification. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 16, 45–57 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Soto AM, Longo G & Noble D From the century of the genome to the century of the organism: new theoretical approaches. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol 122, 1–82 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Soto AM et al. Toward a theory of organisms: three founding principles in search of a useful integration. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol 122, 77–82 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Myers JP et al. Why public health agencies cannot depend on good laboratory practices as a criterion for selecting data: the case of bisphenol A. Environ. Health Perspect 117, 309–315 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vandenberg LN et al. Regulatory decisions on endocrine disrupting chemicals should be based on the principles of endocrinology. Reprod.Toxicol 38, 1–15 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Beausoleil C et al. Regulatory identification of BPA as an endocrine disruptor: context and methodology. Mol. Cell Endocrinol 475, 4–9 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schug TT et al. A new approach to synergize academic and guideline-compliant research: the CLARITY-BPA research program. Reprod. Toxicol 40, 35–40 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Heindel JJ et al. NIEHS/FDA CLARITY-BPA research program update. Reprod. Toxicol 58, 33–44 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Prins GS et al. Prostate cancer risk and DNA methylation signatures in aging rats following developmental BPA exposure: a dose-response analysis. Env. Health Perspect 125, 077007 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Heindel JJ et al. Data integration, analysis, and interpretation of eight academic CLARITY-BPA studies. Reprod. Toxicol 98, 29–60 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tremblay-Franco M et al. Dynamic metabolic disruption in rats perinatally exposed to low doses of bisphenol-A. PLoS ONE 10, e0141698 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rubin BS et al. Perinatal BPA exposure alters body weight and composition in a dose specific and sex specific manner: the addition of peripubertal exposure exacerbates adverse effects in female mice. Reprod. Toxicol 68, 130–144 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vandenberg LN, Hunt PA & Gore AC Endocrine disruptors and the future of toxicology testing – lessons from CLARITY-BPA. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 15, 366–374 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Montévil M et al. A combined morphometric and statistical approach to assess nonmonotonicity in the developing mammary gland of rats in the CLARITY-BPA study. Env. Health Perspect 128, 57001 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Soto AM & Sonnenschein C Endocrine disruptors – putting the mechanistic cart before the phenomenological horse. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 14, 317–318 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zoeller RT & Vandenberg LN Assessing dose-response relationships for endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs): a focus on non-monotonicity. Env. Health 14, 42 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sonnenschein C & Soto AM Over a century of cancer research: inconvenient truths and promising leads. PLoS Biol 18, e3000670 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Speroni L et al. Hormonal regulation of epithelial organization in a 3D breast tissue culture model. Tissue Eng. C Methods 20, 42–51 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Paulose T, Speroni L, Sonnenschein C & Soto AM Estrogens in the wrong place at the wrong time: fetal BPA exposure and mammary cancer. Reprod. Toxicol 54, 58–65 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sonnenschein C & Soto AM Carcinogenesis explained within the context of a theory of organisms. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol 122, 70–76 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Montévil M, Speroni L, Sonnenschein C & Soto AM Modeling mammary organogenesis from biological first principles: cells and their physical constraints. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol 122, 58–69 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bich L, Mossio M & Soto AM Glycemia regulation: from feedback loops to organizational closure. Front. Physiol 11, 69 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Chemicals strategy for sustainability towards a toxic-free environment https://ec.europa.eu/environment/pdf/chemicals/2020/10/Strategy.pdf (2020).

- 103.Howdeshell KL, Hotchkiss AK, Thayer KA, Vandenbergh JG & vom Saal FS Exposure to bisphenol A advances puberty. Nature 401, 763–764 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Honma S et al. Low dose effects of in utero exposure to bisphenol A and diethylstilbestrol on female mouse reproduction. Reprod. Toxicol 16, 117–122 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cunha GR et al. New approaches for estimating risk from exposure to diethylstilbestrol. Environ. Health Perspect 107, 625–630 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rubin BS, Murray MK, Damassa DA, King JC & Soto AM Perinatal exposure to low doses of bisphenol-A affects body weight, patterns of estrous cyclicity and plasma LH levels. Environ. Health Perspect 109, 675–680 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hatch EE et al. Age at natural menopause in women exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero. Am. J. Epidemiol 164, 682–688 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Markey CM, Wadia PR, Rubin BS, Sonnenschein C & Soto AM Long-term effects of fetal exposure to low doses of the xenoestrogen bisphenol-A in the female mouse genital tract. Biol. Reprod 72, 1344–1351 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yamamoto M et al. Effects of maternal exposure to diethylstilbestrol on the development of the reproductive system and thyroid function in male and female rat offspring. J. Toxicol. Sci 28, 385–394 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Register B et al. The effect of neonatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol, coumestrol, and beta-sitosterol on pituitary responsiveness and sexually dimorphic nucleus volume in the castrated adult rat. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med 208, 72–77 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Vandenberg LN et al. The mammary gland response to estradiol: monotonic at the cellular level, non-monotonic at the tissue-level of organization? J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol 101, 263–274 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wadia PR et al. Perinatal bisphenol-A exposure increases estrogen sensitivity of the mammary gland in diverse mouse strains. Environ. Health Perspect 115, 592–598 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Newbold RR, Jefferson WN, Padilla-Banks E & Haseman J Developmental exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) alters uterine response to estrogens in prepubescent mice: low versus high dose effects. Reprod. Toxicol 18, 399–406 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Angle BM et al. Metabolic disruption in male mice due to fetal exposure to low but not high doses of bisphenol A (BPA): evidence for effects on body weight, food intake, adipocytes, leptin, adiponectin, insulin and glucose regulation. Reprod. Toxicol 42, 256–268 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Shimpi PC et al. Hepatic lipid accumulation and Nrf2 expression following perinatal and peripubertal exposure to bisphenol A in a mouse model of nonalcoholic liver disease. Env. Health Perspect 125, 087005 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cabaton NJ et al. Effects of low doses of bisphenol A on the metabolome of perinatally exposed CD-1 mice. Environ. Health Perspect 121, 586–593 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Alonso-Magdalena P, Quesada I & Nadal Á Prenatal exposure to BPA and offspring outcomes: the diabesogenic behavior of BPA. Dose Response 13, 1559325815590395 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Palanza P, Nagel SC, Parmigiani S & vom Saal FS Perinatal exposure to endocrine disruptors: sex, timing and behavioral endpoints. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci 7, 69–75 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Palanza P, Parmigiani S, Liu H & vom Saal FS Prenatal exposure to low doses of the estrogenic chemicals diethylstilbestrol and o,p′-DDT alters aggressive behavior of male and female house mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 64, 665–672 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hunt PA et al. Bisphenol A exposure causes meiotic aneuploidy in the female mouse. Curr. Biol 13, 546–553 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Munoz de Toro MM et al. Perinatal exposure to bisphenol A alters peripubertal mammary gland development in mice. Endocrinology 146, 4138–4147 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Markey CM, Luque EH, Munoz de Toro MM, Sonnenschein C & Soto AM In utero exposure to bisphenol A alters the development and tissue organization of the mouse mammary gland. Biol. Reprod 65, 1215–1223 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bern HA, Mills KT, Hatch DL, Ostrander PL & Iguchi T Altered mammary responsiveness to estradiol and progesterone in mice exposed neonatally to diethylstilbestrol. Cancer Lett 63, 117–124 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hovey RC et al. Effects of neonatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol, tamoxifen, and toremifene on the BALB/c mouse mammary gland. Biol. Reprod 72, 423–435 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Acevedo N, Rubin BS, Schaeberle CM & Soto AM Perinatal BPA exposure and reproductive axis function in CD-1 mice. Reprod. Toxicol 79, 39–46 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Newbold RR et al. Increased tumors but uncompromised fertility in the female descendants of mice exposed developmentally to diethlystilbestrol. Carcinogenesis 19, 1655–1663 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Murray TJ, Maffini MV, Ucci AA, Sonnenschein C & Soto AM Induction of mammary gland ductal hyperplasias and carcinoma in situ following fetal bisphenol A exposure. Reprod. Toxicol 23, 383–390 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Acevedo N, Davis B, Schaeberle CM, Sonnenschein C & Soto AM Perinatally administered bisphenol A as a potential mammary gland carcinogen in rats. Env. Health Perspect 121, 1040–1046 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Rothschild TC, Boylan ES, Calhoon RE & Vonderhaar BK Transplacental effects of diethylstilbestrol on mammary development and tumorigenesis in female ACI rats. Cancer Res 47, 4508–4516 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Newbold RR, Jefferson WN & Padilla-Banks E Long-term adverse effects of neonatal exposure to bisphenol A on the murine female reproductive tract. Reprod. Toxicol 24, 253–258 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wolstenholme JT, Goldsby JA & Rissman EF Transgenerational effects of prenatal bisphenol A on social recognition. Horm. Behav 64, 833–839 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ziv-Gal A, Wang W, Zhou C & Flaws JA The effects of in utero bisphenol A exposure on reproductive capacity in several generations of mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 284, 354–362 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]