Abstract

The monoclonal antibody (MAb) 2H1 defines an epitope in Cryptococcus neoformans capsular glucuronoxylomannan (GXM) that can elicit protective antibodies. In murine models of cryptococcosis, MAb 2H1 administration prolongs survival and reduces fungal burden but seldom clears the infection. The mechanism by which C. neoformans persists and escape antibody-mediated clearance is not understood. One possibility is that variants that do not bind MAb 2H1 emerge in the course of infection. Using an agglutination-sedimentation protocol, we recovered a variant of strain 24067 that did not agglutinate, could not be serotyped, and had marked reduction in GXM O-acetyl groups. Binding of MAb 2H1 to 24067 variant cells produced a different immunofluorescence pattern and lower fluorescence intensity relative to the parent 24067 cells. Addition of MAb 2H1 to 24067 variant cells had no effect on cell charge. Phagocytic assays demonstrated that MAb 2H1 was not an effective opsonin for the 24067 variant. The 24067 variant was less virulent than the 24067 parent strain in mice, and MAb 2H1 administration did not prolong survival in animals infected with the variant strain. To investigate whether variants which do not bind MAb 2H1 are selected in experimental infection, three C. neoformans strains were serially passaged in mice given either MAb 2H1 or no antibody. Analysis of passaged isolates by agglutination assay, flow cytometry, and indirect immunofluorescence revealed changes in MAb 2H1 epitope expression but no clear trend with regards to gain or loss of MAb 2H1 epitope. C. neoformans variants with reduced MAb 2H1 epitope content can be isolated in vitro, but persistence of infection in mice given MAb 2H1 does not appear to be a result of selection of escape variants that lack the MAb 2H1 epitope.

Cryptococcus neoformans is a pathogenic fungus that can cause life-threatening infections (reviewed in references 33 and 35). The organism has a polysaccharide capsule that functions to inhibit phagocytosis and suppresses both humoral and cellular-mediated immune responses (reviewed in references 2, 10, and 33). The main antigenic component of the capsule is glucuronoxylomannan (GXM), a polymer consisting of an α-(1,3)-mannan backbone with various degrees of substitution with xylosyl, glucuronopyranosyluronic acid, and acetyl residues (10). Structural differences in the capsular polysaccharide result in antigenic differences that define four serotypes, A through D (10). Several research groups have generated monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) to the capsular polysaccharide (5, 21, 22, 47, 50, 52). Administration of some MAbs can prolong the survival of mice lethally infected with C. neoformans (reviewed in references 3 and 46). Furthermore, a vaccine that elicits antibodies to GXM is protective in mice (18). Hence, there is interest in developing MAbs for adjunctive therapy and for designing vaccines that elicit protective antibody responses (20).

Antibody efficacy against C. neoformans is dependent on isotype and epitope specificity (40, 44, 48, 56). The mechanism by which antibody mediates protection is not fully understood but is believed to involve enhancement of cellular immunity by providing opsonins, reducing polysaccharide levels, and promoting more intense inflammatory responses (reviewed in references 23 and 53). However, in many experiments MAb administration prior to C. neoformans infections prolongs survival and reduces the fungal burden but seldom promotes complete eradication of infection (reviewed in reference 3). This finding suggests that some fraction of the C. neoformans inoculum is able to escape antibody-mediated clearance, but there is no information on how this may occur. One potential mechanism for persistence is through the selection of antigenic variants that differ in epitope expression. The selection of antigenic variants lacking epitope to neutralizing determinants is known to be a mechanism by which pathogens escape antibody-mediated immunity (35).

In this study, we used an agglutination-sedimentation protocol to select a variant with markedly reduced MAb 2H1 binding as a consequence of reduced O-acetyl group content in GXM. The existence of this variant prompted us to examine whether MAb 2H1 epitope loss is a mechanism by which C. neoformans strains escape humoral clearance mechanisms.

(Part of the data in this report was presented at the 35th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 13 to 16 September 1997, San Francisco, Calif., and is from a thesis submitted by W. Cleare in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of doctor of philosophy in the Sue Golding Graduate Division of Medical Science, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Yeshiva University, Bronx, N.Y.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

Strains 24067 (serotype D; also known as 52D) and 62066 (serotype A) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.). Strain C3D was obtained from Kwon-Chung (Bethesda, Md.). Strain 24067 was selected for study because it has been extensively used in antibody protection studies. Strain 62066 was selected for study because it is representative of the most common clinical serotype and its polysaccharide structure is well characterized (11). Strain C3D was selected because it is a spontaneous mutant of strain H99 with reduced capsule (30). Strains were maintained as a frozen stock culture (50% sterile glycerol) at −80°C and, upon use, inoculated into Sabouraud dextrose (SAB) broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and grown in a rotary incubator (125 to 150 rpm, 30°C; Lab-Line Instruments, Inc., Melrose Park, Ill.).

MAbs.

MAb 2H1 (immunoglobulin G1 kappa light chain [IgG1κ]) and MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 (IgM) have been described elsewhere (5). Antibody concentration was determined relative to isotype-matched standards of known concentration by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (5). For macrophage assays, MAb 2H1 was purified by protein G chromatography (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

Mice.

Male A/JCr mice (6 weeks old) were obtained from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, Md.) and used in all animal experiments.

In vitro selection procedure.

An agglutination-sedimentation selection protocol was developed to recover variants with altered MAb 2H1 epitope expression based on their inability to agglutinate (Fig. 1). Strain 24067 was grown in SAB broth for 48 h. Cells were washed twice in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and counted with a hemacytometer. Approximately 6 × 107 yeast cells were added to a sterile microcentrifuge tube containing MAb 2H1 (1 mg/ml) in a total volume of 1 ml. Cells were also incubated in PBS as a control. The cell suspensions were placed on a rotary platform (Eberbach Corp., Ann Arbor, Mich.) for 15 min and then left undisturbed at room temperature to allow antibody-agglutinated cells to settle. After 1 h, the cell count of the supernatant fluid was determined with a hemacytometer. To complete this first round of selection, 10 ml of the supernatant was then added to 10 ml of fresh SAB broth to expand cells that did not agglutinate. After growth for 24 h, the cell suspension was washed twice in sterile PBS, cells were counted, and a second selection was begun by incubating 6 × 107 cells as described above with either MAb 2H1 or PBS.

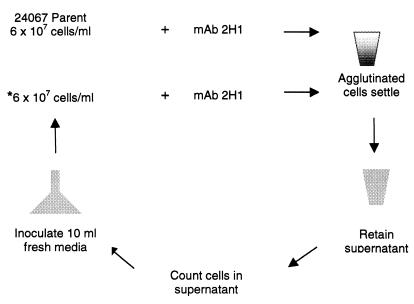

FIG. 1.

Selection scheme used to isolate C. neoformans variant cells. Parent 24067 cells were incubated with MAb 2H1 at room temperature for 1 h, and agglutinated cells were allowed to settle. The supernatant was then carefully removed, cells in the supernatant were counted, and a 10-ml aliquot was added to 10 ml of fresh medium. After 24 h of growth of the new culture, another round of selection (*) was begun. The figure depicts cells incubated with MAb 2H1 only. Another set of cells was incubated in PBS as a control for supernatant cell counts in the absence of MAb 2H1 (Fig. 3).

Chemical de-O-acetylation.

Parent 24067 cells were grown in SAB broth for 24 h and de-O-acetylated as described elsewhere (32). Briefly, cells were washed five times in 40 ml of distilled H2O and placed in a 50-ml beaker, and the pH was adjusted to 11.0 with concentrated NaOH (Fisher Scientific, Fairlawn, N.J.). After 24 h, the cells were washed five times with and suspended in PBS.

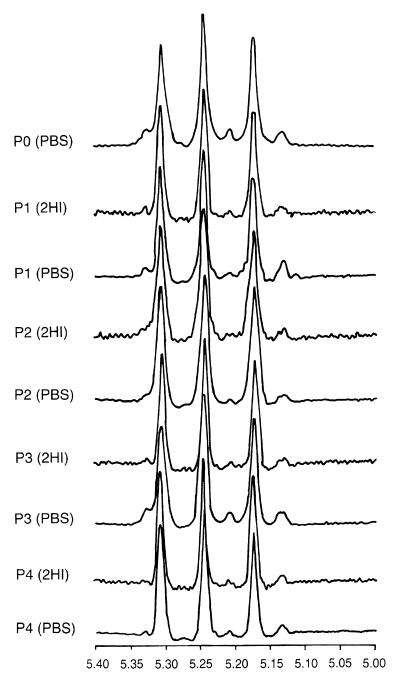

NMR spectroscopy.

GXM was purified from the supernatant of parent and variant 24067 strains grown in SAB broth for 10 d by hexadecyldimethylammonium bromide (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, Wis.) precipitation as described elsewhere (6). GXM and de-O-acetylated GXM (∼10 mg) were exchanged in 99.9% D2O and lyophilized (8). Each sample was dissolved in 0.80 ml of 99.96% D2O and then filtered through a Millipore MILLEX-GS 0.22-μm-pore-size filter; the filtrate was transferred into a 5-mm nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) tube (Wilmad 528-PP). All 1H NMR experiments were performed at 80°C on a Varian Unity 500 spectrometer equipped with a 5-mm 1H/19F probe. 1H chemical shifts were measured relative to internal sodium 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonate taken as 0.00 ppm. The data were processed off-line, using the FELIX 2.30 software package (Biosym/Molecular Simulations, San Diego, Calif.) on a Silicon Graphics Indy workstation. Each spectrum was resolution enhanced by applying a sine bell window function over all real data points. The spectrum between 5.00 and 5.40 ppm, where only the mannosyl residues resonate, was analyzed separately. This is the structure reporter group (SRG) region used to identify the specific saccharide sequences present in a particular GXM (11).

Characterization of variant.

Melanin synthesis was determined by examining colonies grown on minimal medium plates supplemented with l-dopa as described elsewhere (54). Growth rates of the parent and variant 24067 at 37°C and capsule size were measured as described elsewhere (24). Factor serum (Iatron Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan) was used to test the serotype of the variant strain as instructed by the manufacturer. The lowest concentration of MAb 2H1 required to agglutinate C. neoformans cells (agglutination endpoint) was determined as described previously (14), as were electrophoretic karyotypes of the C. neoformans 24067 parent and variant (26). The zeta potential of 24067 parent and variant cells, a measurement of cell charge (in millivolts), was obtained in the presence or absence of MAb 2H1 by using a Pen Kem (Bedford Hills, N.Y.) model 501 Lazer Zee meter as described previously (43). Scanning electron microscopy of 24067 parent and variant cells in the presence and absence of MAb 2H1 was done as described elsewhere (13).

Indirect IF.

Strain 24067 parent and variant cells from 3- to 5-day cultures were washed three times in PBS and prepared for indirect immunofluorescence (IF) studies as described previously (12). Samples were viewed with a confocal microscope (MRC 600; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) as described previously (44). Passaged isolates were plated on SAB agar. A single colony was grown in SAB broth for 24 h, washed twice in sterile PBS, and mounted onto poly-l-lysine-coated slides (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). MAb 2H1 was added at concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 0.01 μg/ml to determine the fluorescent antibody titer. MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 were added (10 μg/ml) to determine fluorescence binding pattern. After a minimum 3-h incubation, slides were washed with PBS and incubated with 10 μg of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG1 (MAb 2H1) or IgM (MAbs 12A1 and 13F1) (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, Ala.), and the assay was completed as described elsewhere (14).

Flow cytometry.

Cells were analyzed for MAb 2H1 binding by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using a FACScan as described elsewhere (12). Cells without MAb gave the same results as cells incubated with the irrelevant IgG1 MAb 3665, which has specificity for the hapten p-azophenylarsonate and was used as a negative control. Clumped cells were eliminated from analysis by forward scatter gating.

Revertant analysis.

Three methods were used in an attempt to isolate revertants of the 24067 variant. The first was a modification of a cell capture assay that uses MAb 2H1 to capture and immobilize cells (4). Briefly, a 96-well polystyrene plate was coated with 50 μl of unlabeled goat anti-mouse IgG1 (1 μg/ml; Southern Biotechnology Associates) blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS, and then incubated for 2 h with MAb 2H1 (5 μg/ml) at 37°C. A 105 suspension of variant cells/well was added for 2 to 4 h and, after removal of nonadherent cells, and washed five times with sterile PBS. SAB broth (100 μl) was added to the ELISA wells; after 24 h at 30°C, the cells were transferred to fresh SAB broth, incubated overnight at 30°C, and tested in the agglutination assay as described above. If the cells failed to agglutinate, the capture assay was repeated. The second method reversed the agglutination-sedimentation protocol used to isolate the 24067 variant, except that this time we selected for cells that agglutinated. The third method involved recovery of colonies from mice chronically infected with the 24067 variant (see below).

Macrophage studies.

The opsonic efficacy of MAb 2H1 for 24067 parent and variant was studied in assays using the J774.16 macrophage cell line as described elsewhere (42). The phagocytic index is the number of internalized yeast cells per number of macrophages per field; the attachment index is the number of attached yeast cells per number of macrophages per field. For each MAb, at least three fields, each containing at least 200 cells, were counted. The antifungal efficacy of J774.16 cells was also determined for 24067 parent and variant strains as described elsewhere (42).

Virulence and antibody protection studies.

Mice were given either 1 mg of MAb 2H1, 1 mg of MAb 3665 (irrelevant isotype-matched control), or PBS via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection 4 h prior to infection. Mice were infected with 1 × 105 or 5 × 106 cells of either 24067 parent or variant cells by lateral tail vein and observed daily to record deaths. The inoculum was determined by counting yeast cells in a hemacytometer and confirmed by plating efficiency on SAB agar. Lethal dose studies were performed with the 24067 variant as described above except that the mice were not given MAb 2H1 or PBS prior to infection. Four groups of five mice were given 5 × 104, 5 × 105, 5 × 106, or 5 × 107 cells via lateral tail vein, and the number of deaths was recorded daily.

Strain passage studies.

Two protocols were used to passage C. neoformans in mice given MAb 2H1: single-colony passage and homogenate passage (Fig. 2). In the first method, C. neoformans cells from strains 62066, C3D, and 24067 were streaked on SAB agar to obtain single colonies. One colony (P0 [not passaged]) was selected and grown in SAB broth. The cells were washed twice in sterile PBS and used to infect mice at an inoculum of 107/mouse i.p. as described elsewhere (41). One hour prior to infection, mice were injected i.p. with either sterile PBS or 1 mg of MAb 2H1 in ascites fluid. After 5 to 10 days, the mice were killed by cervical extension, the lungs were removed and homogenized in 5 ml of sterile PBS, and dilutions of the homogenate were spread on SAB agar to recover single colonies. Single colonies were recovered from agar and identified as passage 1 (P1), passage 2 (P2), etc. One colony was then suspended in SAB broth for 24 h and prepared in the manner described for subsequent passage in mice given PBS or MAb 2H1 ascites fluid. In the second method, mice were infected with 105 organisms intravenously (i.v.), housed in the animal facility for 5 days, and then killed by cervical extension. Lungs were removed, homogenized in PBS, and filtered through a 70-μm-mesh-size nylon cell strainer (Falcon 2350; Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, N.J.), and 1 ml of the homogenate was used to infect additional mice by the i.p. route.

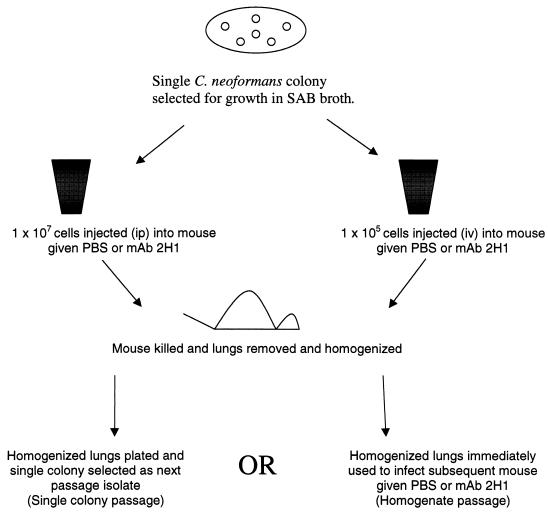

FIG. 2.

Two selection schemes were used to obtain C. neoformans epitope variants in vivo. In the first scheme (left), a single colony of C. neoformans was grown in SAB broth (P0), the suspension of cells was adjusted, and 107 organisms were injected into mice pretreated with PBS or MAb 2H1 by the i.p. route. After approximately 10 days, the mice were killed, and their lungs were removed and plated. A single colony was then selected as the next-passage isolate. In the second scheme (right), a single colony of C. neoformans was grown in SAB broth (P0); the suspension of cells was adjusted to 105 organisms and used to infect mice (by the i.v. route) pretreated with PBS or MAb 2H1. After 5 days, lungs were removed, homogenized, and used immediately to infect additional mice (by the i.p. route) pretreated with PBS or MAb 2H1.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was done with Primer of Statistics—The Program (McGraw Hill, New York, N.Y.), SigmaStat statistical analysis system version 1.01 (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, Calif.), and the SPSS program for Windows 8.0, 1997 (SPSS, Chicago, Ill.).

RESULTS

Isolation of 24067 variant strain.

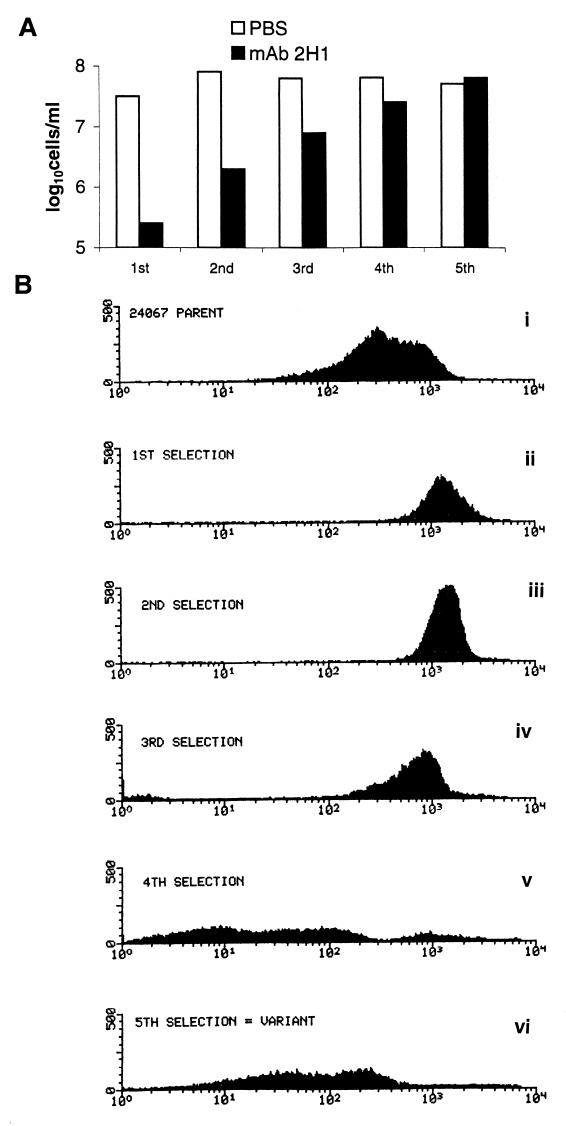

The method used for isolating antigenic variants in vitro used an agglutination-sedimentation protocol that enriched for cells that did not agglutinate in the presence of MAb 2H1 (Fig. 1). Similar selection schemes based on agglutination have been used to recover mutants to surface antigens in other systems (17, 51). The number of nonagglutinating cells in the MAb 2H1 supernatant increased after each selection (Fig. 3A), suggesting that cells which did not agglutinate were selected and expanded. After the fifth selection, the 24067 variant was recovered. Analysis of cell suspensions in the steps prior to variant selection revealed changes in the fluorescence intensity after each stage of the selection (Fig. 3B). The largest difference in FACS profile occurred between the third and fourth selection steps (Fig. 3B). The MAb 2H1 agglutination endpoints for the parent and variant were 7.8 and >500 μg/ml, respectively. Five independent selection experiments with the 24067 parent were done (using different starting cultures derived from single 24067 parent colonies), but only once did we observed the emergence of a nonagglutinating population of cells. In another attempt to increase the probability of selecting nonagglutinating cells, we irradiated 24067 parent cells with UV, but no variants were selected. Furthermore, we attempted to recover nonagglutinating variants from cultures of strain 62066 but were not successful despite five independent selection experiments using the protocol shown in Fig. 1. Hence, this protocol can select for variant cells but does so infrequently.

FIG. 3.

Selection of the 24067 variant. (A) Hemacytometer cell counts from supernatant of cell suspensions incubated for 1 h in PBS or MAb 2H1. PBS supernatant cell counts remained constant throughout the selection process, whereas MAb 2H1 supernatant cell counts increased after each selection consistent with enrichment for nonagglutinating cells. (B) FACS profiles of cell suspensions before (i) and after (ii to vi) each round of selection. The cells had been incubated with MAb 2H1 and an FITC-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG1 antibody. The x axis represents relative fluorescence intensity; the y axis represents the number of cells. For each measurement, 10,000 cells were evaluated.

Comparative analysis of 24067 parent and variant strains.

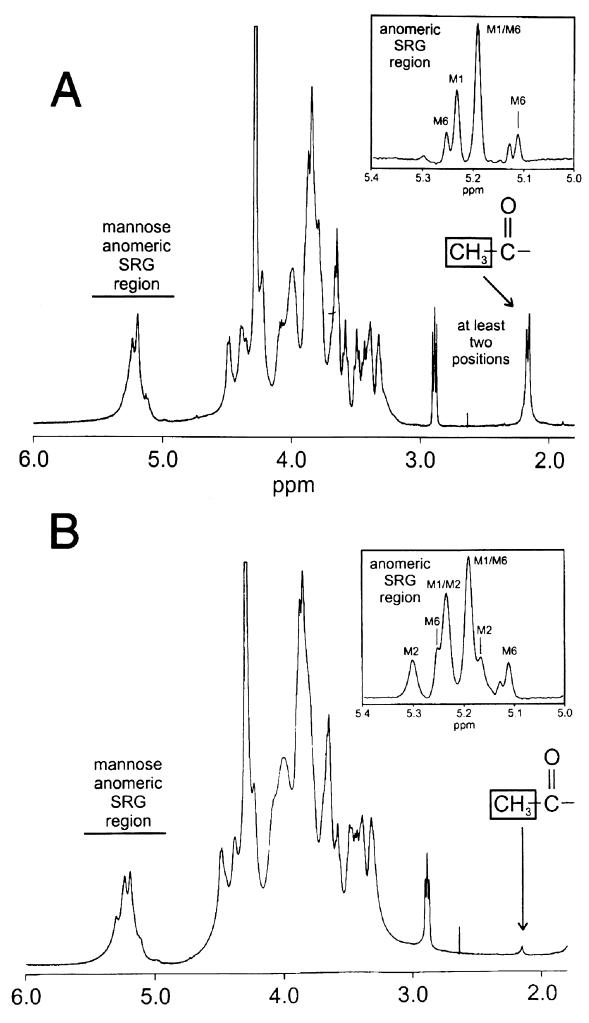

The GXM of the 24067 parent was analyzed by proton NMR in its native and de-O-acetylated states (Fig. 4). This GXM belongs to the Chem1 chemotype, based on the occurrence of the structure reporter group M1 (11). The O-acetyl ratio of one O-acetyl group for every three mannose residues was determined by integrating the appropriate areas in the NMR spectrum of the native form of GXM. This value is lower than the 1.7 O-acetyl groups for every three mannose residues reported previously for typical serotype D isolates (9). A similar analysis of the 24067 variant isolate showed two major changes in structure relative to the NMR data for the 24067 parent. The most dramatic difference was the almost complete absence of O-acetyl groups in the variant, only one O-acetyl group present for every 11 mannose residues. The second alteration in the structure was the appearance of a second SRG, M2, which is characteristic of serotype A isolates. The chemotype of the 24067 variant switched to Chem2 since it was comprised of the SRGs M1 (major component) and M2 (11). Comparisons of the SAGs present in each isolate are shown in the insets of Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

One-dimensional 1H NMR spectra of GXM from 24067 parent (A) and variant (B) cells. The insets are the resolution-enhanced proton spectra for the SRG regions of the de-O-acetylated derivatives of the GXM. The SRGs are indicated as M1, M2, and M6. The SRG region is comprised of the chemical shifts for the mannosyl residues of the GXM structure. For a full description of the SRGs and chemotyping, see reference 11.

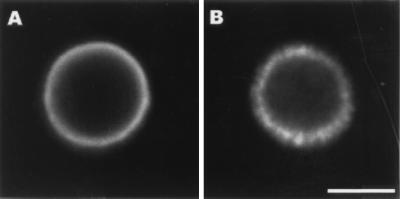

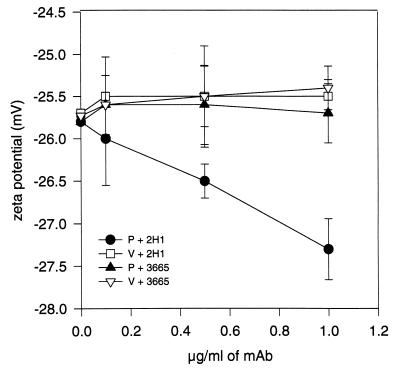

De-O-acetylation of 24067 parent cells resulted in cells which did not agglutinate with MAb 2H1, indicating that loss of O-acetyl groups was sufficient to produce the variant phenotype (data not shown). The 24067 variant could not be serotyped with factor serum. Several phenotypes associated with virulence, including the ability to make melanin, growth at 37°C, and capsule size, were examined but no significant differences were noted between 24067 parent and variant (Table 1). The electrophoretic karyotypes of the 24067 parent and variant were indistinguishable (data not shown). IF studies of 24067 parent and variant with MAb 2H1 revealed differences in capsule fluorescence patterns. The 24067 parent displayed an annular pattern after MAb 2H1 binding, whereas the 24067 variant displayed a punctate pattern (Fig. 5). Studies using MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 revealed additional differences in agglutination and IF pattern (Table 2). FACScan of cells incubated with MAb 2H1 revealed mean fluorescence intensities of 673 and 13 for the 24067 parent and variant, respectively. Measurement of zeta potential revealed no difference between parent and variant cells in the absence of MAb 2H1, but addition of MAb 2H1 increased the negative charge for parent cells but not for variant cells (Fig. 6). Variant GXM did not inhibit MAb 2H1 binding to parent GXM by inhibition ELISA (data not shown). Scanning electron microscopy studies demonstrated that MAb 2H1 had no effect on variant capsular structure but altered the capsular structure of parent 24067, as reported previously (39) (data not shown). Hence, variant 24067 was characterized by having a structurally different GXM with significantly reduced reactivity for MAb 2H1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of 24067 parent and variant isolates

| Isolate | Colony morphology | Melanin production | Doubling time (h)a | Capsule size (μm)b | Cell diam (μm)c | O-Acetyl contentd | Zeta potentiale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent | Smooth | Yes | 3.4 | 2.39 ± 0.73 | 9.46 ± 1.7 | 1:3 | −25.8 ± 0.20 |

| Variant | Smooth | Yes | 3.4 | 2.03 ± 0.42 | 10.0 ± 1.4 | 1:11 | −25.7 ± 0.21 |

Calculated by plotting CFU/milliliter versus time for parent and variant cells over 38 h and using the curve fitting program of the SigmaPlot (Jandel Scientific) graphing software.

Measured from cell wall to outer border; mean ± standard deviation of 28 measurements; P for capsule size comparison = 0.028 (Student t test).

Measured from one edge of capsule to opposite edge; mean ± standard deviation of 28 measurements; P for cell diameter = 0.2. (Student t test).

Determined by NMR; reported as ratio of the number of O-acetyl groups to the number of mannose residues.

P for comparison of parent and variant zeta potential = 0.234 (Student t test).

FIG. 5.

Indirect IF of 24067 parent (A) and variant (B) after incubation with mAb 2H1 (10 μg/ml) followed by FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 (1 μg/ml). Samples were viewed with an MRC 600 laser scanning confocal microscope (Bio-Rad). Single optical sections were collected at a magnification of ×4 with NikonX N.A. phase 4 optics. The scale bar represents 5 mm. A representative cell is shown.

TABLE 2.

Reactivities of 24067 parent and variant cells with three MAbs

| MAb | Parent

|

Variant

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IF pattern | Agglutination endpoint (μg/ml) | IF pattern | Agglutination | |

| 2H1 (IgG1) | Annular | 3.9 | Punctate | >500 |

| 12A1 (IgM) | Annular | 3.9 | Punctate | 31.25 |

| 13F1 (IgM) | Punctate | 31.2 | Punctate | >500 |

FIG. 6.

Zeta potentials of 24067 parent and variant cells incubated in the presence of either GXM-binding MAb 2H1 or irrelevant isotype-matched MAb 3665. Points are the average of three measurements; error bars denote standard deviations. There was no significant difference in cell charge for 24067 parent cells (P) incubated with MAb 3665 and variant cells (V) incubated with MAb 3665 or MAb 2H1.

Interactions of 24067 parent and variant with J774.

In the absence of MAb 2H1, neither the 24067 parent nor variant cells were phagocytosed by J774.16 (Fig. 7A). MAb 2H1 was significantly (P < 0.001) more opsonic for the 24067 parent strain but had little effect on ingestion of the 24067 variant (P < 0.216) (Fig. 7A). When attachment was measured (Fig. 7B), MAb 2H1 significantly enhanced the attachment of the variant relative to conditions without antibody (P ≤ 0.012). Addition of MAb 2H1 to suspensions of J774 and variant 24067 cells had no significant effect on fungal CFU (P ≤ 0.892). In contrast, addition of MAb 2H1 to suspensions of J774 and 24067 parent cells resulted in a significant reduction in CFU (P ≤ 0.001) as reported previously (Fig. 7C) (42).

FIG. 7.

(A) Effect of MAb 2H1 on ingestion by J774.16 macrophages of 24067 parent and variant cells; (B) effect of MAb 2H1 on attachment of parent and variant cells to J774.16 cells; (C) effect of MAb 2H1 on C. neoformans CFU after coincubation with J774.16 cells. Each bar is the average of five measurements; error bars denote standard deviations. P values are calculated relative to ingestion and attachment indices or to CFU obtained with J774.16 cells in the absence of MAb. For the experiment in panel C, the inocula for parent and variant differ because there were fewer viable cells in the parent inoculum (37% viability) than in the variant inoculum (100% viability). Each experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

Virulence and passive antibody protection studies.

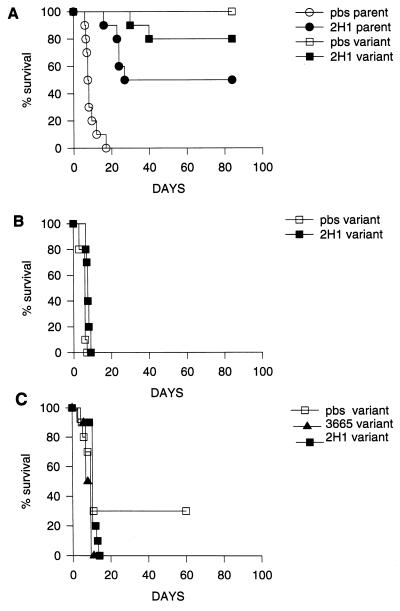

Mouse studies were done to compare the virulence of the 24067 parent and variant strains and to establish whether MAb 2H1 administration prolonged survival of mice infected with the 24067 variant. In the first protection study using an inoculum of 105, all control (PBS-treated) mice infected with the 24067 parent died by day 18 of infection, whereas all mice infected with the 24067 variant strain were alive at day 84 of infection (Fig. 8A). At day 127 of infection, the lungs from six (three PBS-treated and three MAb 2H1-treated) mice infected with the 24067 variant were homogenized and plated for CFU; each was found to be chronically infected (data not shown). Administration of MAb 2H1 prolonged survival of mice infected with the 24067 parent, but the protective efficacy of MAb 2H1 for the 24067 variant could not be evaluated because only 2 of 20 mice died by day 40 (Fig. 8A). This finding suggested that the 24067 variant was less virulent, and we therefore performed a lethal dose study. Mice infected with 24067 variant cell inocula of 5 × 108, 5 × 107, and 5 × 106 lived 3, 4, and 28 days, respectively. No deaths were observed in mice infected with 5 × 105 cells after several months of infection. As a result, we used 5 × 106 cells as the infecting dose for MAb 2H1 protection experiments with the 24067 variant strain. Two antibody protection experiments were done with the 24067 variant given the higher inoculum. In the first (Fig. 8B), all PBS-treated animals died by day 7 of infection and all MAb 2H1-treated animals died by day 9 of infection. In the second experiment, MAb 2H1 administration did not prolong survival of infected mice relative to two control groups given either PBS or the irrelevant IgG1 MAb 3665 (Fig. 8C).

FIG. 8.

(A) Survival of mice infected with 105 cells of 24067 parent or variant treated with MAb 2H1 or PBS. (B) Survival curve of A/Jcr mice infected with 5 × 106 cells of variant 24067. (C) Same as panel B except that the irrelevant isotype-matched control MAb 3665 (1 mg) or MAb 2H1 was given in ascites fluid 4 h prior to infection. The x axis represents days after infection; the y axis represents percent survival.

Stability of 24067 variant strain in vitro and in vivo.

Agglutination assays of 24067 parent and variant isolates were done over a 6-month period to determine whether their phenotypes were stable. Serial subcultures of the parent and variant were assayed eight times during this period; in all experiments, 500 to 1,000 mg of MAb 2H1 per ml failed to agglutinate the variant 24067 cells, whereas 3.9 to 7.8 mg/ml consistently agglutinated the parent 24067 cells. To determine if cells of the 24067 variant could revert to the parental phenotype, we reversed our original isolation procedure by beginning the selection process with variant cells, discarding supernatant, and testing the remaining cells for agglutination with MAb 2H1. No revertants were isolated. Next, we attempted to recover revertants by capturing them with MAb 2H1 immobilized on polystyrene plates, but no revertants were recovered after three attempts. Last, we searched for revertants among isolates recovered from chronically infected mice (127 days) but these also did not agglutinate with MAb 2H1. Hence, no revertants were isolated despite multiple attempts using three selection strategies.

Single-colony passage.

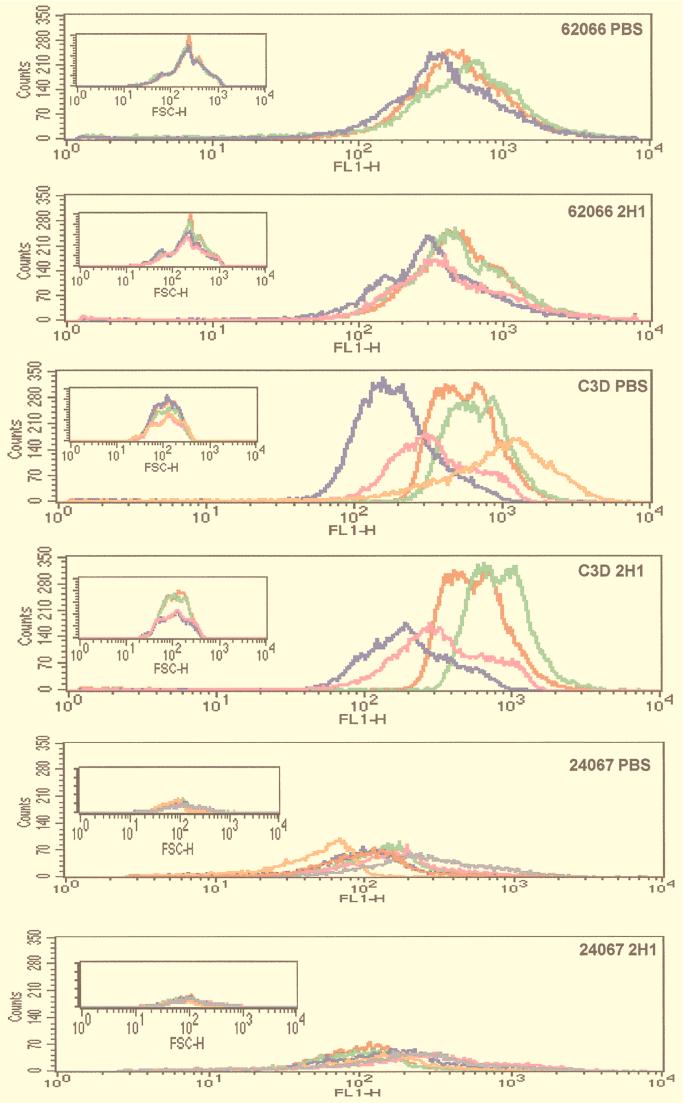

Strains 62066, 24067, and C3D were passaged in mice given MAb 2H1 or PBS (controls) to investigate MAb 2H1 selected for variants with altered epitope content. Passaged isolates obtained from strains 62066, C3D, and 24067 were analyzed in the agglutination assay (Table 3). There were no significant differences in the agglutination endpoints for isolates of strain 62066 before and after passage in mice given PBS or MAb 2H1. For strains 24067 and C3D, the agglutination endpoints for isolates passaged in mice given PBS or MAb were all the same or within onefold dilution of the endpoint for the original isolate. There was some variation in the IF endpoint, but there was no consistent trend toward higher or lower MAb 2H1 binding for isolates passaged in mice given MAb 2H1 or PBS. Flow cytometry results revealed some differences in fluorescence intensity among sequential 62066, 24067, and C3D isolates (Fig. 9; Table 4). For strain 62066, there was a trend toward reduced fluorescence intensity as the number of passages increased regardless of whether mice were given PBS or MAb 2H1. For strains 24067 and C3D, passaged isolates demonstrated significant variation in the average fluorescence intensity but no clear trend with regard to MAb 2H1 epitope prevalence. The heterogeneity of passaged isolates is evident in Fig. 9, which demonstrates that while the fluorescence intensity varies from sample to sample, the forward scatter, which measures relative cell size, is fairly constant. Analysis of the ungated forward scatter of passaged isolates did not reveal any significant differences in cell size or alteration in the homogeneity or heterogeneity of the population as a whole (data not shown). Hence, fluorescence intensity varied among the passaged isolates, and this variation was not due to differences in cell size. Analysis of GXM from colonies of strain 62066 passaged in mice given MAb 2H1 or PBS revealed no significant differences in GXM structure by NMR (Fig. 10). The electrophoretic karyotypes of the initial and passaged 62066 isolates were the same (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Serological characteristics of initial and passaged C. neoformans strains

| Isolate | IF patterna

|

Endpoint (μg/ml)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAb 12A1

|

MAb 13F1

|

IF

|

Agglutination

|

|||||

| PBS | 2H1 | PBS | 2H1 | PBS | 2H1 | PBS | 2H1 | |

| 62066 | ||||||||

| P0 | A | A | A | A | 0.1 | 0.1 | 6.25 | 6.25 |

| P1 | A | A | A | A | 0.1 | <0.01 | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| P2 | A | A | A | A | 0.1 | 0.1 | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| P3 | NDb | A | ND | A | ND | 0.1 | ND | 0.1 |

| 24067 | ||||||||

| P0 | A | A | P | P | <0.01 | <0.01 | 1 | 1 |

| P1 | A | A | P | P | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.5 | 1.9 |

| P2 | A | A | P | P | <0.01 | <0.01 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| P3 | A | A | P | P | <0.01 | <0.01 | 1.9 | 1 |

| P4 | A | A | P | P | <0.01 | <0.01 | 1.9 | 1 |

| P5 | A | A | P | P | <0.01 | <0.01 | 1 | 1 |

| C3D | ||||||||

| P0 | A | A | A | A | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| P1 | A | A | A | A | 0.1 | <0.01 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| P2 | A | ND | A | ND | <0.01 | ND | 0.5 | ND |

| 62066c | ||||||||

| P0 | A | A | A | A | 0.1 | 0.1 | 6.25 | 6.25 |

| P1 | A | A | A | A | 1 | 1 | 3.9 | 7.8 |

| C3Dc | ||||||||

| P0 | A | A | A | A | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| P1 | A | A | A | A | 1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.9 |

A, annular; P, punctate. Results are for isolated passaged in mice given PBS or 2H1, as indicated.

ND, not done.

Passaged in mice by the organ homogenate method.

FIG. 9.

Flow cytometry histogram plots of 24067 isolates passaged by the single-colony method. For the large panels, the x axis represents fluorescence intensity and the y axis represents number of cells. Color code for passaged samples: green, P1; blue, P2; pink, P3; orange, P4; gray, P5. The initial isolate, P0, is shown in red. Insets show histograms of forward scatter (a measurement of cell size) for the same passaged isolates.

TABLE 4.

Fluorescence intensities of strains passaged in mice given PBS or MAb 2H1

| Isolate | Fluorescence intensitya

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 62066

|

24067

|

C3D

|

||||

| PBS | 2H1 | PBS | 2H1 | PBS | 2H1 | |

| P0 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 5.4 | 5.4 |

| P1 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 0.04 | 0.75 | 7.3 | 8.7 |

| P2 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 0.11 | 0.73 | 1.5 | 1.9 |

| P3 | NDb | 1.4 | 0.68 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 1.9 |

| P4 | ND | ND | 0.79 | 3.5 | 6.8 | 2.8 |

| P0c | 2.7 | 2.7 | ND | ND | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| P1c | 1.1 | 1.8 | ND | ND | 1.6 | 2.2 |

Ratio of measured fluorescence divided by forward scatter to normalize for cell size differences. Results are for isolated passaged in mice given PBS and MAb 2H1, as indicated.

ND, not done.

Passaged in mice by the organ homogenate method.

FIG. 10.

One-dimensional 1H NMR spectra of GXM from GXM from passaged 62066 strains in mice given either MAb 2H1 or PBS. The minor variations in spectral shape are not considered significant.

Homogenate passage.

This protocol differs in the fact that a fungal population is passaged instead of a single colony. Analyses of individual colonies recovered from the passage of strains 62066 and C3D by the homogenate method are presented in Tables 3 and 4. For strain 62066, the agglutination endpoint increased onefold for both PBS and 2H1 isolates after passage, but this change is within the error of the assay. For strain C3D, there was a fourfold increase in agglutination endpoint for cells passaged in mice given 2H1. For both 62066 and C3D, there was a trend toward less MAb 2H1 binding in isolates from both PBS- and MAb 2H1-treated mice, as revealed by higher IF endpoints and lower fluorescence intensities.

MAb 12A1/13F1 binding pattern.

The IF pattern of the parent strain was preserved for all passaged isolates (Table 3).

Reproducibility and consistency of measurements.

Agglutination endpoints were measured for strains 62066, C3D, and 24067 at least two times on different days. The endpoints were always within one dilution. FACS studies were done multiple times for each strain on different days, and the results were always consistent.

DISCUSSION

A variant of strain 24067 that did not agglutinate in the presence of MAb 2H1 was recovered after five rounds of selection in an agglutination-sedimentation assay. FACScan profiles of 24067 variant cells revealed decreased fluorescence intensity after each round consistent with enrichment for a population of cells with reduced MAb 2H1 epitope expression. As the selection progressed, there was considerable heterogeneity in the MAb 2H1 binding to individual cells. The inability of MAb 2H1 to agglutinate the variant 24067 cells as well as the results of FACS, ELISA, and cell charge studies implies reduction or alteration of the MAb 2H1 epitope. Selection of the variant strain as a consequence of inadvertent contamination of the 24067 culture with another C. neoformans isolate is extremely unlikely since all previously studied strains of C. neoformans are agglutinated by MAb 2H1 (14). Chromosome analysis of parent and variant strains revealed identical electrophoretic karyotype patterns. Hence, the variant was derived from 24067 and differs from the 24067 parent in having a qualitatively different GXM (see below). We attempted to recover additional nonagglutinating variants from strains 24067 and 62066 but were not successful. This could imply that nonagglutinating variants are rare or that this selection protocol is not very efficient.

The variant was stable after in vitro and mouse passage, as indicated by retention of the nonagglutinating phenotype. We attempted to obtain revertants of the variant to the agglutinating phenotype but were not successful. The in vitro methods used to recover revertants involved selection for agglutinating cells and antibody capture. Based on the theoretical sensitivity of these methods, we estimate that revertants occur at frequencies of less than 10−5 to 10−6. Our inability to recover revertants may reflect a low reversion rate, a genetic deletion, and/or inadequate sensitivity of the methods used here.

The variant GXM NMR analysis showed that two major changes occurred in the structure of the variant GXM compared to that of the parent isolate. The most significant alteration in structure was the almost total absence of O-acetyl groups. The second change was the appearance of a second SRG, M2, that is usually associated with serotype A polysaccharide. The parent GXM is Chem1, whereas the variant is Chem2 (11). Prior studies have shown that GXM O-acetyl groups are important for MAb 2H1 binding (5, 45). Chemical de-O-acetylation of 24067 parent yielded cells which also failed to agglutinate in the presence of MAb 2H1. Loss of O-acetyl groups in the GXM provides a structural explanation for the phenotype of the 24067 variant. The variant could not be serotyped with factor serum, a finding that can also be explained by the reduced O-acetyl content. O-Acetyl groups are critically important for GXM antigenic structure given that de-O-acetylated GXMs do not react with serotype-specific sera (1). The reason for the appearance of serotype A polysaccharide features is unknown but is consistent with prior reports of polysaccharide changes among isolates assigned to a serotype (7). There was no difference in cell charge between variant and parent cells. Since the polysaccharide capsule is responsible for the highly negative charge of C. neoformans (34, 43), this result suggests that O-acetylation does not make a major contribution to cell charge. However, this interpretation must be made cautiously because there was a small difference in capsule size, which may have an effect on cell charge (43). The absence of change in zeta potential of variant cells after addition of MAb 2H1 is consistent with markedly reduced antibody binding to the capsule.

Indirect IF provided visual evidence for epitope differences in the capsule of the parent and variant strains. The variant gave a punctate IF pattern with MAb 2H1, as well as other MAbs studied, whereas the parent gave an annular IF pattern. The physical basis for the punctate pattern is not known (discussed in reference 12). One possibility is that the epitope density is reduced upon selection. Another possibility is that the variant has altered capsular polysaccharide conformation which may be due to the loss of O-acetyl groups. Studies with Salmonella paratyphi A have shown that de-O-acetylation can destroy conformational antigenic determinants required for recognition by MAb and that acetylation affects the three-dimensional structure of the lipopolysaccharide epitope (49). Loss of O-acetyl groups may increase the conformational flexibility of GXM and allow the formation of complexes between primary and secondary antibody which result in a punctate IF pattern.

The 24067 variant was less virulent than the parent strain but was still capable of establishing chronic infections in mice. Comparison of various strain characteristics associated with virulence revealed no significant differences between variant and parent strains, but we recognize that the variant cells may not be isogenic as a result of selection. The loss of O-acetyl groups in the 24067 variant could be sufficient to explain its reduced virulence. For Legionella pneumophila (57), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (38), Trichosporon beigelii (37), and Escherichia coli (25), polysaccharide O-acetylation has been associated with virulence. De-O-acetylation of C. neoformans cells in vitro increases complement component C3 deposition in the capsule (55), which could translate into more efficient phagocytosis in vivo and thereby reduce the virulence of the isolate. De-O-acetylated polysaccharide is also less effective in inhibiting chemotaxis in vitro than native polysaccharide (28).

Phagocytic studies revealed that the opsonic efficacy of MAb 2H1 for the variant strain was greatly reduced and are consistent with previous studies which indicate that a punctate MAb IF binding pattern was associated with reduced opsonic efficacy (12). The “zipper” model of phagocytosis proposes that for particles to be effectively phagocytosed, there must be sequential, circumferential interaction of ligand and phagocyte membrane receptors (31). Our observations in the phagocytosis studies with the variant strain can be interpreted, and are consistent, with this model. When the epitope for MAb 2H1 is evenly distributed on the surface of the parent (annular IF pattern), ingestion occurs possibly because the antibody is able to attach to Fc receptors and trigger the sequence of molecular events which result in attachment and uptake. When the epitope for 2H1 is unevenly distributed on the surface of the 24067 variant (punctate IF pattern), ingestion may not occur despite attachment. Hence, MAb 2H1 promoted attachment of variant cells to J774.16 macrophages, but this did not enhance macrophage antifungal efficacy presumably because ingestion did not occur. The protective efficacy of MAb 2H1 for the 24067 parent has been established in multiple animal studies (for a review see reference 23) and was confirmed here. However, for the 24067 variant, MAb 2H1 administration prolonged survival by only 2 days in one experiment and had no effect on survival in a second experiment. The reduced MAb 2H1 binding to the 24067 variant leads to reduction in both opsonic and protective efficacy.

The finding that encapsulated C. neoformans variants with altered MAb 2H1 epitope expression exist has several implications. First, the 24067 variant demonstrates that C. neoformans can assemble a capsule with markedly reduced O-acetylation. Second, emergence of such variants in human infection could affect the sensitivity of diagnostic assays. False-negative latex agglutination assays have been reported for several patients whose biological fluid was positive for C. neoformans by culture (16). Third, such variants, if they arise during infection, may affect the efficacy of conjugate vaccines or MAb therapies. Hence, we proceeded to investigate whether variant cells which did not bind MAb 2H1 were generated in infection.

There is evidence that C. neoformans variants with altered polysaccharide structure can emerge during human infection (7). Since MAb 2H1 is opsonic and promotes clearance of infection, we surmised that the MAb 2H1 epitope would be under strong selection pressure in vivo. To evaluate this hypothesis, we passaged three C. neoformans strains in mice in the presence and absence of antibody and evaluated epitope prevalence in the initial and passaged isolates by agglutination endpoint, indirect IF endpoint, and FACS intensity profile. Two passage schemes, single colony and whole-organ lysate, were used to infect mice. In a series of experiments involving at least 40 passage experiments for three C. neoformans strains, we were unable to show a consistent change in the capsule epitope recognized by the MAb 2H1. Furthermore, all isolates recovered from mice treated with and without MAb 2H1 reacted with MAb 2H1, albeit there were some differences between passaged isolates and the parent strain. None of the passaged isolates resembled the 24067 variant in their serological characteristics. The observation that the 24067 variant with reduced O-acetyl content was hypovirulent suggests that if such variants are selected by antibody in vivo, they may not persist in tissue. Hence, selection for variants that lack the MAb 2H1 epitope does not appear to be the cause for persistent infection in mice given passive antibody. One potential explanation for persistence of infection despite antibody administration is that C. neoformans can survive intracellularly after phagocytosis (19, 36). Since stability of the MAb 2H1 epitope does not imply stability for other antigenic determinants, we also evaluated reactivities of passaged isolates with MAbs 12A1 and 13F1 but found no significant changes in the type of IF pattern. The stability of the MAb 2H1 epitope in mice given MAb 2H1 is reassuring for plans to use a similar MAb for therapy of human cryptococcosis.

Despite the presence of the MAb 2H1 epitope in all passaged isolates, for several we measured changes in FACS intensity which imply changes in MAb 2H1 binding. Analysis of forward scatter data shows that differences in FACS were not due to selection of populations with different cell sizes. Presumably, the differences in MAb 2H1 binding among passaged isolates reflects changes in MAb 2H1 epitope prevalence or accessibility. We did measure intriguing differences in MAb 2H1 prevalence that are not explained by differences in capsule size and, for strain 62066, by GXM structure as revealed by NMR analysis. These observations suggest that some fraction of C. neoformans cells undergo changes in epitope expression during infection. This finding is consistent with prior reports that passage of C. neoformans in mice alters the sterol composition (15) and is associated with frequent chromosome rearrangements (27), and that serial isolates from patients with chronic infection differ in virulence for mice (26). Furthermore, our results fit within the emerging view that some strains of C. neoformans such as 24067 can undergo rapid phenotypic variation as microevolution (24) and phenotypic switching (29).

REFERENCES

- 1.Belay T, Cherniak R. Determination of antigen binding specificities of Cryptococcus neoformans factor sera by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1810–1819. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1810-1819.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchanan K L, Murphy J W. What makes Cryptococcus neoformans a pathogen? Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:71–83. doi: 10.3201/eid0401.980109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casadevall A. Antibody immunity and invasive fungal infections. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4211–4218. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4211-4218.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casadevall A, Cleare W, Feldmesser M, Glatman-Freedman A, Goldman D L, Kozel T R, Lendvai N, Mukherjee J, Pirofski L, Rivera J, Rosas A L, Scharff M D, Valadon P, Westin K, Zhong Z. Characterization of a murine monoclonal antibody to Cryptococcus neoformans polysaccharide that is a candidate for human therapeutic studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1437–1446. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.6.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casadevall A, Mukherjee J, Devi S J N, Schneerson R, Robbins J B, Scharff M D. Antibodies elicited by a Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan-tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine have the same specificity as those elicited in infection. J Infect Dis. 1992;65:1086–1093. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.6.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherniak R, Morris L C, Anderson B C, Meyer S A. Facilitated isolation, purification, and analysis of glucuronoxylomannan of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1991;59:59–64. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.59-64.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherniak R, Morris L C, Belay T, Spitzer E D, Casadevall A. Variation in the structure of glucuronoxylomannan in isolates from patients with recurrent cryptococcal meningitis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1899–1905. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1899-1905.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherniak R, Morris L C, Meyer S A. Glucuronoxylomannan of Cryptococcus neoformans serotype C: structural analysis by gas-liquid chromatography and 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Carbohydr Res. 1992;225:331–337. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90505-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherniak R, Morris L C, Turner S H. Glururonoxylomannan of Cryptococcus neoformans serotype D: structural analysis by gas-liquid chromatography and 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Carbohydr Res. 1992;223:263–269. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(92)80023-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherniak R, Sundstrom J B. Polysaccharide antigens of the capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1507–1512. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1507-1512.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherniak R, Valafar H, Morris L C, Valafar F. Cryptococcus neoformans chemotyping by quantitative analysis of 1H NMR spectra of glucuronoxylomannans using a computer-stimulated artificial neural network. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:146–159. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.2.146-159.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleare W, Casadevall A. The different binding patterns of two IgM monoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A and D strains correlates with serotype classification and differences in functional assays. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:125–129. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.2.125-129.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cleare, W., and A. Casadevall. Scanning electron microscopy of encapsulated and non-encapsulated Cryptococcus neoformans and the effect of glucose on capsular polysaccharide release. Med. Mycol., in press. [PubMed]

- 14.Cleare W, Mukherjee S, Spitzer E D, Casadevall A. Prevalence in Cryptococcus neoformans strains of a polysaccharide epitope which can elicit protective antibodies. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1994;1:737–740. doi: 10.1128/cdli.1.6.737-740.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Currie B, Sanati H, Ibrahim A S, Edwards J E, Casadevall A, Ghannoum M A. Sterol compositions and susceptibilities to amphotericin B of environmental Cryptococcus neoformans isolates are changed by murine passage. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1934–1937. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.9.1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Currie B P, Freundlich L F, Soto M A, Casadevall A. False-negative cerebrospinal fluid cryptococcal latex agglutination tests for patients with culture-positive cryptococcal meningitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2519–2522. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.9.2519-2522.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtiss R, III, Pearce C, Pollack J, Murchison H M. Isolation and characterization of mutants of Streptococcus mutans using selective removal of wild-type cells by agglutination with an agglutinin from Persea americana. Acta Microbiol Pol. 1987;36:3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devi S J N. Preclinical efficacy of a glucuronoxylomannan-tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine of Cryptococcus neoformans in a murine model. Vaccine. 1996;14:841–842. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00256-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diamond R D, Bennett J E. Growth of Cryptococcus neoformans within human macrophages in vitro. Infect Immun. 1973;7:231–236. doi: 10.1128/iai.7.2.231-236.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dixon D M, Casadevall A, Klein B, Travassos L R, Deepe G. Development of vaccines and their use in the prevention of fungal infections. Med Mycol. 1998;36(Suppl.):57–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dromer F, Salamero J, Contrepois A, Carbon C, Yeni P. Production, characterization, and antibody specificity of a mouse monoclonal antibody reactive with Cryptococcus neoformans capsular polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1987;55:742–748. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.3.742-748.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eckert T F, Kozel T R. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies specific for Cryptococcus neoformans capsular polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1895–1899. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.8.1895-1899.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feldmesser M, Casadevall A. Mechanism of action of antibody to capsular polysaccharide in Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Front Biosci. 1998;3:136–151. doi: 10.2741/a270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franzot S P, Mukherjee J, Cherniak R, Chen L, Hamdan J S, Casadevall A. Microevolution of a standard strain of Cryptococcus neoformans resulting in differences in virulence and other phenotypes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:89–97. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.89-97.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frasa H, Procee J, Torensma R, Verbruggen A, Algra A, Rozenberg-Arska M, Kraaijeveld K, Verhoef J. Escherichia coli in bacteremia: O-acetylated K1 strains appear to be more virulent than non-O-acetylated K1 strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3174–3178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.12.3174-3178.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fries B C, Casadevall A. Serial isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans from patients with AIDS differ in virulence for mice. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1761–1788. doi: 10.1086/314521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fries B C, Chen F, Currie B P, Casadevall A. Karyotype instability in Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1531–1534. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1531-1534.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujihara H, Kagaya K, Fukazawa Y. Anti-chemotactic activity of capsular polysaccharide of Cryptococcus neoformans in vitro. Microbiol Immunol. 1997;41:657–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1997.tb01908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldman D L, Fries B C, Franzot S P, Montella L, Casadevall A. Phenotypic switching in the human pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans is associated with changes in virulence and pulmonary inflammatory response in rodents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14967–14972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Granger D L, Perfect J R, Durack D T. Virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Regulation of capsule synthesis by carbon dioxide. J Clin Investig. 1985;76:508–516. doi: 10.1172/JCI112000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffin F M, Griffin J A, Leider J E, Silverstein S C. Studies on the mechanism of phagocytosis. I. Requirements for circumferential attachment of particle-bound ligands to specific receptors on the macrophage plasma membrane. J Exp Med. 1975;142:1263–1282. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.5.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kozel T R. Dissociation of a hydrophobic surface from phagocytosis of encapsulated and nonencapsulated Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1983;39:1214–1219. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.3.1214-1219.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kozel T R. Virulence factors of Cryptococcus neoformans. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:295–299. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88957-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kozel T R, Reiss E, Cherniak R. Concomitant but not casual association between surface charge and inhibition of phagocytosis by cryptococcal polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1980;29:295–300. doi: 10.1128/iai.29.2.295-300.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lambkin R, McLain L. Neutralization escape mutants of type A influenza virus are readily selected by antisera from mice immunized with whole virus: a possible mechanism for antigenic drift. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:3493–3502. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-12-3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levitz S M, Farrell T P. Growth inhibition of Cryptococcus neoformans by cultured human monocytes: role of the capsule, opsonins, the culture surface, and cytokines. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1201–1209. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1201-1209.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyman C A, Devi S J, Nathanson J, Frasch C E, Pizzo P A, Walsh T J. Detection and quantitation of the glucuronoxylomannan-like polysaccharide antigen from clinical and nonclinical isolates of Trichosporon beigelii and implications for pathogenicity. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:126–130. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.126-130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mai G, Seow W K, Pier G B, McCormack J G, Thong Y H. Suppression of lymphocyte and neutrophil functions by Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide (alginate): reversal by physicochemical, alginase, and specific monoclonal antibody treatments. Infect Immun. 1993;61:559–564. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.559-564.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mukherjee J, Cleare W, Casadevall A. Monoclonal antibody mediated capsular reactions (quellung) in Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol Methods. 1995;184:139–143. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00097-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mukherjee J, Nussbaum G, Scharff M D, Casadevall A. Protective and non-protective monoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans originating from one B-cell. J Exp Med. 1995;181:405–409. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mukherjee J, Scharff M D, Casadevall A. Protective murine monoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4534–4541. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4534-4541.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mukherjee S, Lee S C, Casadevall A. Antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan enhance antifungal activity of murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 1995;63:573–579. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.573-579.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nosanchuk J D, Casadevall A. Cellular charge of Cryptococcus neoformans: contributions from the capsular polysaccharide, melanin, and monoclonal antibody binding. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1836–1841. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1836-1841.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nussbaum G, Cleare W, Casadevall A, Scharff M D, Valadon P. Epitope location in the Cryptococcus neoformans capsule is a determinant of antibody efficacy. J Exp Med. 1997;185:685–697. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Otteson E W, Welch W H, Kozel T R. Protein-polysaccharide interactions. A monoclonal antibody specific for the capsular polysaccharide of Cryptococcus neoformans. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1858–1864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pirofski L, Casadevall A. Antibody immunity to Cryptococcus neoformans: paradigm for antibody immunity to the fungi? Zentbl Bakteriol. 1996;284:475–495. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(96)80001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pirofski L, Lui R, DeShaw M, Kressel A B, Zhong Z. Analysis of human monoclonal antibodies elicited by vaccination with a Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan capsular polysaccharide vaccine. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3005–3014. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3005-3014.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanford J E, Lupan D M, Schlagetter A M, Kozel T R. Passive immunization against Cryptococcus neoformans with an isotype-switch family of monoclonal antibodies reactive with cryptococcal polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1919–1923. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1919-1923.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Slauch J M, Mahan M J, Michetti P, Neutra M R, Mekalanos J J. Acetylation (O-factor 5) affects the structural and immunological properties of Salmonella typhimurium lipopolysaccharide O antigen. Infect Immun. 1995;63:437–441. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.437-441.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spiropulu C, Eppard R A, Otteson E, Kozel T R. Antigenic variation within serotypes of Cryptococcus neoformans detected by monoclonal antibodies specific for the capsular polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3240–3242. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.10.3240-3242.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takegawa K, Tanaka N, Tabuchi M, Iwahara S. Isolation and characterization of a glycosylation mutant from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1996;60:1156–1159. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Todaro-Luck F, Reiss E, Cherniak R, Kaufman L. Characterization of Cryptococcus neoformans capsular glucuronoxylomannan polysaccharide with monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3882–3887. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.12.3882-3887.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vecchiarelli A, Casadevall A. Antibody-mediated effects against Cryptococcus neoformans: evidence for interdependency and collaboration between humoral and cellular immunity. Res Immunol. 1998;149:321–333. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(98)80756-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Y, Casadevall A. Susceptibility of melanized and nonmelanized Cryptococcus neoformans to nitrogen- and oxygen-derived oxidants. Infect Immun. 1994;64:3004–3007. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.3004-3007.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Young B J, Kozel T R. Effects of strain variation, serotype, and structural modification on kinetics for activation and binding of C3 to Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2966–2972. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2966-2972.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yuan R, Casadevall A, Spira G, Scharff M D. Isotype switching from IgG3 to IgG1 converts a non-protective murine antibody to C. neoformans into a protective antibody. J Immunol. 1995;154:1810–1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zahringer U, Knirel Y A, Lindner B, Helbig J H, Sonesson A, Marre R, Rietschel E T. The lipopolysaccharide of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 (strain Philadelphia 1): chemical structure and biochemical significance. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1995;292:113–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]