Abstract

Attachment theory suggests that both the quality and consistency of early sensitive care should shape an individual’s attachment working models and relationship outcomes across the lifespan. To date, most research has focused on the quality of early sensitive caregiving, finding that receiving higher quality care predicts more secure working models and better long-term relationship outcomes than receiving lower quality care. However, it remains unclear whether or how the consistency of early sensitive care impacts attachment working models and adult relationship functioning. In this research, we utilized data from the Minnesota Longitudinal Study of Risk and Adaptation to examine to what extent the quality (i.e., mean levels) and consistency (i.e., within-person fluctuations) in behaviorally coded maternal sensitive care assessed 7 times from 3 months to 13 years prospectively predicts secure base script knowledge and relationship effectiveness (i.e., interpersonal competence in close relationships) in adulthood. We found that larger fluctuations and lower mean levels of early maternal sensitivity jointly predict lower relationship effectiveness in adulthood via lower secure base script knowledge. These findings reveal that nonlinear models of early caregiving experiences more completely account for relationship outcomes across the lifespan, beyond what traditional linear models have documented. Implications for attachment theory and longitudinal methods are discussed.

Keywords: Attachment theory, maternal sensitivity, fluctuations, romantic relationships, development

“An infant who has experienced his mother as fairly consistently accessible to him and as responsive to his signals and communications may well expect her to continue to be an accessible and responsive person…”

—Ainsworth et al., 1978, p. 21

According to attachment theory, both the quality and consistency of early sensitive caregiving should shape an individual’s working models and subsequent relationship outcomes later in life (Bowlby, 1969/82). Most prior research has focused on mean levels of early caregiving, documenting that higher quality early caregiving predicts better social and academic competence (Raby et al., 2015a) and attachment security (Farrell et al., 2019) in adulthood. However, an important question remains: Does the degree of consistency in early caregiving also prospectively predict attachment working models and relationship functioning in adulthood?

To answer this question, we leveraged data from the Minnesota Longitudinal Study of Risk and Adaptation (MLSRA; Sroufe et al., 2005)—a sample born below the poverty line and followed through midlife—to prospectively examine the association between consistency (i.e., within-person fluctuations) in early maternal sensitivity and both secure base script knowledge (AAIsbs) and relationship effectiveness (i.e., general interpersonal competence) in adulthood. We hypothesized that larger fluctuations in maternal sensitivity and lower mean levels across childhood should uniquely predict lower levels of secure base script knowledge in early adulthood which should, in turn, result in lower relationship effectiveness at midlife.

Attachment theory

Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969/82, 1973, 1980) explains how early caregiving experiences can shape social and personality development from “cradle to grave” (Bowlby, 1979, p. 129). Across time, early experiences with caregivers generate internal working models (i.e., cognitive schemas, prototypes, and expectations) that then have the potential to impact future close relationships (Ainsworth et al., 1978). Internal working models reflect whether, and the degree to which, individuals believe that their attachment needs will be met within secure base relationships—that is, whether they can turn to their attachment figures for comfort and support when distressed (T. E. A. Waters & Roisman, 2019; Waters & Waters, 2006).

Secure base script knowledge (AAIsbs) reflects the cognitive attachment schemas that individuals have acquired based in part on their prior life experiences with attachment figures. According to Waters and Waters (2006), a secure base script is a temporal-causal chain of events in which an individual is involved in a specific environment, challenges interrupt their involvement, they signal distress to their attachment figure, the signal is recognized by and responded to by the attachment figure supportively, the support is accepted and is effective in reducing the individual’s distress, and the individual then reengages with their environment. Such experiences, if repeated consistently over time, generate adaptive mental representations and expectations (i.e., secure base scripts) of what individuals can expect when facing new challenges or distressing events in the future.

When individuals receive highly responsive and consistent care, they develop secure working models that allow them to explore their world safely, build self-confidence, and trust and rely on their attachment figures (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Bowlby, 1980). However, when individuals experience unresponsive or inconsistent care, they develop insecure working models that inhibit them from feeling confident about independently exploring their worlds and/or prevent them from forming close, trusting relationships with future attachment figures. Extensive research has confirmed that receiving high-quality care early in life is associated with better social and academic competence (e.g., Raby et al., 2015a), better adult relationship functioning (e.g., Roisman et al., 2005; Simpson et al., 2007), and higher levels of attachment security (e.g., Farrell et al., 2019). Indeed, a previous investigation from the MLSRA has found that linear, mean level aggregates of maternal sensitivity in childhood predict secure base script knowledge in early adulthood (T. E. A. Waters et al., 2017).

Despite Bowlby’s (1980) and Ainsworth and colleagues’ (1978) original theorizing about the importance of consistent care, very little research has addressed whether or how consistency in early caregiving, either independently or in combination with caregiving quality, prospectively predicts either secure base script knowledge or romantic relationship functioning later in life. We conceptualize consistency of care as nonlinear dynamics in maternal sensitivity across time (i.e., within-person variation; cf. Girme et al., 2021), which can oscillate and vary around mean levels of quality of care across time.

Some caregivers tend to vary in their level of care and support across time and interactions with their children more so than others. For example, in a study examining mother–child interactions across time, Lindheim and colleagues (2011) found that whereas many mothers are consistent in their provision of care across time and interactions, mothers who have less coherent internal working models varied more in their care behaviors across 10 videotaped interactions with their child. In addition, larger fluctuations in caregiving have been linked with children’s early attachment patterns, such that greater variability in observed maternal sensitivity at multiple time-points during toddlerhood is associated with being classified as insecure in the Strange Situation (Manning, 2019). Moreover, larger fluctuations in maternal sensitivity across different mother–child free play and stressful tasks are associated with poorer attention, less positive engagement, and greater negative affect in toddlers (Chen et al., 2019). Viewed together, these findings suggest that sensitive care operates in nonlinear, variable ways among some mothers, which could affect their child over time.

Evidence connecting fluctuations in caregiving to outcomes in adulthood is much more limited. In one recent study, Girme and colleagues (2020) investigated whether and how fluctuations in early life attachment classifications in the Strange Situations forecasted emotion regulation patterns in adults. They found that infants who received different Strange Situation classifications in two assessments (termed “unstable insecures”) exhibited less effective emotion regulation strategies as adults when trying to resolve romantic relationship conflicts. Although this research begins to address the link between variability in early life experiences and later life outcomes, it does not reveal whether or how the consistency of early caregiving experiences, rather than the byproducts (e.g., security classification) of those experiences, predicts later life outcomes. Accordingly, we do not know whether or how fluctuations in maternal care early in life are linked to later life attachment and relationship outcomes in adulthood.

The current research

No prior research to our knowledge has examined whether or how prospectively assessed within-person fluctuations (i.e., inconsistency) in maternal sensitivity in childhood are associated with either attachment working models or relationship functioning later in life. Leveraging longitudinal data from the MLSRA, we addressed this issue. In particular, we utilized multiple behaviorally coded measures of maternal sensitivity assessed in childhood to assess the impact of nonlinear patterns (e.g., fluctuations) in maternal sensitivity. We hypothesized that both higher mean levels (H1a) and lower fluctuations (H1b) in maternal sensitivity would predict greater secure base script knowledge at ages 19 and 26 years. We also hypothesized that secure base script knowledge in early adulthood would mediate associations between both mean levels and fluctuations in maternal sensitivity and relationship effectiveness. Specifically, higher mean levels (H2a) and lower fluctuations (H2b) in maternal sensitivity should both predict greater secure base script knowledge in early adulthood, which in turn should forecast greater relationship effectiveness (general interpersonal competence) in adulthood at age 32.

Methods

Participants

In 1975–76, 267 mothers in their third trimester of pregnancy with their first child (i.e., the participants) were recruited from Minneapolis, MN (see Sroufe et al., 2005). All mothers were living below the poverty line and receiving free prenatal services at the time of recruitment. Complete data on all of the variables relevant to our hypotheses were gathered on 146 participants. This sample did not differ significantly from those who dropped out of the study on sex, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status (SES). Participant sex was coded as male or female based on their assigned sex on their birth certificate, 51.57% of whom were identified as female and 48.43% of whom were identified as male. Information about gender identity was not collected. Each participant’s race was computed based on the race and ethnicity reported by the participants’ biological mother and father. Most of the sample was identified by their parents as White (58%) with the remaining identified as mixed race (16%), Black (14%), or Latina/o (3%). A minority of the sample (9%) were labeled as unclassifiable because of missing data about their biological father’s race or ethnicity. Information about sexual orientation and disability status was not collected.

Measures and procedure

For the specific scales used for all measures and procedures described below, see the Online Supplemental Material (OSM).

Maternal sensitivity.

Participants (children) and their mothers completed semi-structured and naturalistic video-recorded interactions when participants were 3, 6, 24, 30, 42, and 72 months old and also at age 13. Each task was structured and coded to be developmentally appropriate for the child’s age. In all tasks, mothers were instructed to interact with their child as they normally would when engaging in a similar task at home. At 3 months, mothers were observed feeding their child. At 6 months, mothers were recorded feeding and engaging in free play with their child. Both the 3- and 6-month assessments were coded from 1 (highly insensitive) to 9 (highly sensitive) using Ainsworth et al.’s (1978) sensitivity scale (intraclass correlation [ICC] = .86 at 3 months; ICC = .89 at 6 months).

At 30 months and 72 months, maternal sensitivity was assessed using the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME; Bradley & Caldwell, 1984). The HOME uses both naturalistic observations of mother–child interactions and semi-structured interview questions to assess emotional and verbal responsivity of maternal care in the home environment. The emotional and verbal responsivity scales assess the degree to which the mother appropriately recognizes and responds to their child’s positive and negative behaviors. Maternal behaviors were coded on the emotional and verbal responsivity scale (ICC = .72 at 30 months; ICC = .68 at 72 months).

At 24 and 42 months and 13 years, children were given a complex task intentionally designed to be too difficult (based on their developmental abilities) to complete without assistance. Mothers were instructed to give their child time to complete the task independently and help when the mother thought it was necessary. Mothers were rated for their supportive presence during the task, both while their child was working independently on the task and after/if they intervened. Mothers were assessed for both how emotionally supportive they were of their child if/when they became distressed and how positively they facilitated the completion of the task. This task was intended to parallel, in a developmentally appropriate way, the task administered at 24 and 42 months. The 24- and 42-month and 13-year assessments were coded from 1 (very low) to 7 (very high) for maternal sensitivity (ICC = .85 at 24 months; ICC = .87 at 42 months; ICC = .86 at 13 years).

If participants did not have their mother involved in their life at the time of the assessment, participants completed these interactions with their current primary caregiver. Because these other caregivers were more likely to vary across participants’ lives and given our interest in variability in care from a primary attachment figure, participants who did not complete all assessments with their mother were excluded from the current analyses. However, including these participants in the analyses did not change the direction or significance of the results.

These indexes of maternal support have been widely used in the MLSRA and have been extensively examined for internal consistency of the task instructions, behaviors, and comparability of coding schemes. These measures have been aggregated in prior investigations, and they all load on one factor (see Raby et al., 2015b and T. E. A. Waters et al., 2017). Previous work has also demonstrated that these assessments of maternal sensitivity are associated with expected longitudinal outcomes (e.g., Farrell et al., 2019; Raby et al., 2015a; Raby et al., 2015b; T. E. A. Waters et al., 2017).

Each of the maternal sensitivity measures was then standardized to allow for between-assessment score consistency. Mean levels of maternal sensitivity were computed as the average of each participant’s maternal sensitivity scores across all assessments. Within-person fluctuations were computed as within-person standard deviations of each participant’s maternal sensitivity scores across all assessments.1 All individuals who had completed at least two subsequent assessments of maternal sensitivity were included.

Secure base script knowledge.

At ages 19 and 26, participants completed the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI; George et al., 1984). The AAI is a well-validated, 20-question, semi-structured interview in which participants are asked to recall autobiographical experiences and memories to describe their early caregiving relationships. The AAI is traditionally coded for adult attachment classifications, coherence of the transcript, and coherence of mind. More recent coding techniques of the AAI have emerged, which include assessing the AAI for secure base script knowledge (AAIsbs; T. E. A. Waters & Roisman, 2019; Waters & Waters, 2006).

AAIsbs assesses the degree to which participants have formed stable internal working models (schemas) and expectations about their caregiver’s availability and quality of support (i.e., the provision of a secure base) on a 1 to 9 scale. AAIsbs is coded from responses to the first six questions of the AAI. Coders focus on both the degree to which expectations of caregivers are consistent with secure base scripts and the degree to which participants can easily and coherently recall specific autobiographical memories that follow secure base scripts. Higher scores indicate that participants have a clear secure base script and have developed secure, positive cognitive models of relationships. Lower scores indicate participants do not have a clear, cohesive secure base script and developed insecure and/or negative cognitive models of relationships (T. E. A. Waters et al., 2020). Trained coders’ ratings on AAIsbs were highly reliable (ICC = .83 at 19 years; ICC = .82 at 26 years). Because AAIsbs is relatively stable across time (r = .55), we aggregated the AAIsbs scores from ages 19 and 26. Individuals were included if they completed one or both (averaged) of the AAI assessments.

Relationship effectiveness.

At age 32 years, participants completed an audio-recorded semi-structured interview about their current and prior romantic relationships. Participants answered questions about past conflicts, their own and their partner’s relationship-relevant positive and negative behaviors, relationship likes and dislikes, their own and their partner’s relationship-relevant values and beliefs, and how they and their partners function(ed). Most participants answered questions primarily about their current romantic partner (77.7%), and about half answered questions about at least two different prior relationships (48.2%).

Trained coders read each audio transcript and rated each interview from 1 (low effectiveness) to 5 (high effectiveness). A single score was assigned in keeping with standards of other observational measures (e.g., Ainsworth’s sensitivity scale). Higher scores indicate the participant had a history of high-quality relationships characterized by mutual trust, honesty, care, and commitment; sharing in each other’s values and joys; recognition and sensitivity to each other’s needs; and enjoyment of time spent together. Higher scores also indicate the participant has coped effectively with and recovered from conflicts in a way that typically satisfied both partners’ needs and adequately recovered from relationship dissolution if/when it occurred. Lower scores indicate the participant either had a history of low-quality relationships that lacked the qualities described above or could not form or maintain long-term relationships. Coders’ scores were highly reliable (ICC = .94)

Maternal depressive symptoms.

Maternal depressive symptoms were assessed when participants were 48 months old using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The CES-D includes 20 items that assessed the extent to which mothers reported experiencing depressive symptoms within the last week (e.g., “During the past week, I felt depressed” and “During the past week, I thought my life had been a failure”) on a 0 (less than 1 day per week) to 3 (5–7 days per week) Likert-type scale. The CES-D demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.86). Depressive symptoms were computed as a sum of total depressive symptoms.

Early life stress.

Participants’ mothers completed an interview about life stress using the Life Events Schedule (LES, Cochrane & Robertson, 1973; Egeland et al., 1980) when the participants were 3, 12, 18, 30 42, 48, 54, and 64 months old and when the participants were in grades 1–6. The LES assesses the extent to which various stressful events have impacted or disrupted the mother’s life in the last year. The LES includes 41 items that address topics about financial troubles (e.g., unemployment, changes in income), relationship stress (e.g., break-ups, partner drinking problems), physical danger (e.g., abuse, physical altercations), mortality (e.g., death of a family member, serious illness), and other common stressful life events. Mothers were presented with each type of stressful event and asked to describe each event in detail. Trained coders rate each response on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (no disruption/did not occur) to 3 (severe disruption). Life stress was summed at each assessment to provide an index for life stress/distribution at each age. Life stress from the first 13 years of life was then grouped together to create one overall early life stress index (α = 0.75) that was concurrent with the assessments of maternal sensitivity.

Demographic covariates.

Because certain individual characteristics are known to be associated with early caregiving quality, relationship processes, and attachment working models (Fraley et al., 2013), and to remain consistent with prior MLSRA publications, participants’ sex, race, socioeconomic status, and prenatal maternal education were included as covariates. Race was coded as White or non-White. Socioeconomic status was coded following the Duncan Index of Socioeconomic Status and its conjoining TSEI (prestige) score (Stevens & Featherman, 1981; Stevens & Hyun Cho, 1985). Prenatal maternal education was coded as the total number of years of education attained by the mother before the birth of her child.

Results

See Table 1 for descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations for all study variables. Mean levels of childhood maternal sensitivity were significantly correlated with secure base script knowledge in early adulthood but not with relationship effectiveness in adulthood. Fluctuations in childhood maternal sensitivity were significantly correlated with both secure base script knowledge in early adulthood and relationship effectiveness in adulthood. None of the main model variables were significantly correlated with maternal depressive symptoms. Relationship effectiveness in adulthood was weakly correlated with early life stress. None of the other main model variables (e.g., mean levels and fluctuations in childhood maternal sensitivity, secure base script knowledge) were significantly correlated with early life stress.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal sensitivity mean levels | ||||||

| 2. Maternal sensitivity fluctuations | −.270** | |||||

| 3. Secure base script knowledge | .362** | −.369** | ||||

| 4. Relationship effectiveness | .080 | −.202* | .272** | |||

| 5. Maternal depressive symptoms | −.148 | .063 | −.055 | .146 | ||

| 6. Early life stress | .019 | .152 | −.025 | −.16* | .118 | |

| M | 0.00 | 0.68 | 3.22 | 3.51 | 14.42 | 15.19 |

| SD | 1.00 | 0.24 | 1.44 | 1.30 | 10.78 | 7.58 |

Note:

p < .05;

p < .001; maternal sensitivity was z-transformed, resulting in a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. N = 146.

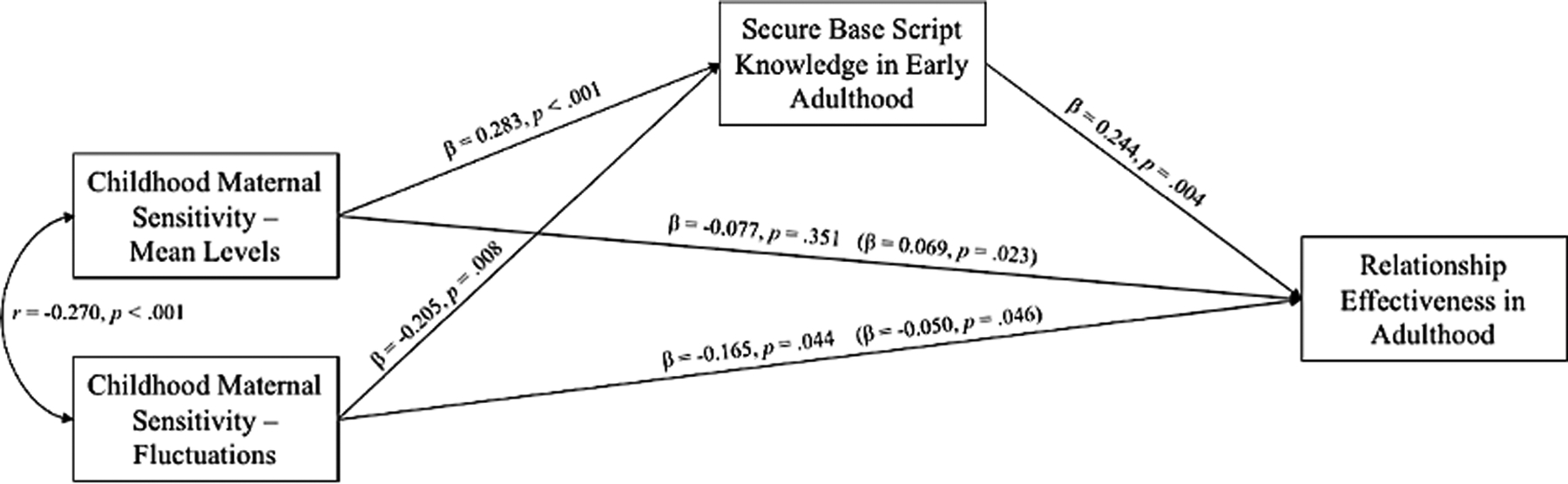

We tested our primary hypotheses using path analysis with maximum likelihood estimation in lavaan (R version 4.1.0; Rosseel, 2012). Covariates (e.g., maternal depressive symptoms, early life stress, and the demographic covariates) were regressed on maternal sensitivity mean levels and fluctuations, secure base script knowledge, and relationship effectiveness (see OSM for example R code). Including covariates did not significantly change any of the effects detected. All reported betas for direct and indirect effects are standardized. Because mean levels and fluctuations in maternal sensitivity were derived from the same measures, we allowed them to correlate (r = −0.270). Our model fit the data well (χ2 (1) = 0.724, p = .395, RMSEA = .02, CFI = 0.98) (see Figure 1).2

Figure 1.

Mean levels and fluctuations in maternal sensitivity on relationship effectiveness in midlife via secure base script knowledge in early adulthood. Note: N = 146; indirect effects are displayed in parentheses; childhood maternal sensitivity was assessed 7 times from behavioral assessments from ages 3 months through 13 years; secure base script knowledge was assessed twice, once at ages 19 and 26, and was aggregated; and relationship effectiveness was assessed at age 32.

Supporting Hypotheses 1a and 1b, higher mean levels and lower fluctuations in maternal sensitivity uniquely predicted higher secure base script knowledge in early adulthood. Higher mean levels in maternal sensitivity did not have a significant direct effect on relationship effectiveness at age 32. However, lower fluctuations in maternal sensitivity did significantly predict greater relationship effectiveness at age 32.

Secure base script knowledge in early adulthood significantly mediated the effect of both mean levels and fluctuations in childhood maternal sensitivity on relationship effectiveness in adulthood. Supporting Hypothesis 2a, higher mean levels of maternal sensitivity significantly predicted higher relationship effectiveness via higher secure base script knowledge. Supporting Hypothesis 2b, lower fluctuations in maternal sensitivity also significantly predicted higher relationship effectiveness via higher secure base script knowledge.

Discussion

Attachment theory is one of the few major theories to make claims about nonlinear effects from its inception. To date, however, most research has focused on linear or mean level effects rather than on both mean levels and variability in caregiving, as Bowlby (1969/82) and Ainsworth et al. (1978) proposed. In this research, we investigated whether and how inconsistencies (e.g., fluctuations) in early maternal sensitivity prospectively predicted attachment working models (indexed by secure base script knowledge) and romantic relationship competence across more than 30 years. We found that smaller fluctuations (i.e., greater consistency) in maternal sensitivity during childhood significantly predicted general competence in romantic relationships at midlife via their secure base script knowledge earlier in adulthood, even when controlling for the mean levels of early maternal sensitivity and key demographics. We also found that the effects for fluctuations in early maternal sensitivity on later relationship functioning were more reliable than those for mean levels of maternal sensitivity.

Notably, we found that the effects of mean levels and fluctuations in maternal sensitivity are robust above and beyond other potential logical confounds, such as maternal depressive symptoms and early life stress. Previous research has suggested that maternal depression (Beck, 1995; Bernard et al., 2018; Campbell et al., 2007; Kujawa et al., 2014; Leerkes et al., 2015) and life stress (Belsky & Fearon, 2002; Booth et al., 2018; Conger & Donnellan, 2007) are associated with how sensitively mothers care for their children, which in turn can affect children’s long-term outcomes. However, we find that both mean levels of and fluctuations in early maternal sensitivity predicted the outcomes we studied independently of these possible confounding variables. This suggests that caregiving experiences—in and of themselves—are likely to be influential in the development of working models and relational behaviors in adulthood.

What is the psychological meaning of experiencing large fluctuations in caregiver sensitivity, particularly for young children? Within parent–child relationships, the origins of caregiving fluctuations might originate from what Bronfenbrenner (1979) termed microsystem or mesosystem sources (e.g., the inherent instability of caregivers and/or their romantic relationships, other forms of instability within the nuclear family or immediate environment) and/or exosystem or macrosystem sources (e.g., changing issues with extended family, neighbors, or other people in the wider social environment). Regardless of the origin, young children should perceive large fluctuations in the quality of care they receive as a valid cue signaling that some important feature of their environment is unstable and unpredictable, indicating that close others—including primary caregivers—cannot be depended on to be consistently available and supportive across time. According to Chisholm (1996), children should have evolved to detect and respond to this unique type of threat, with inconsistent, unpredictable caregiving being viewed as the caregiver’s inability (rather than unwillingness) to invest in them due to changing events, situations, or resources. This logic parallels attachment theory, which claims that unpredictable caregiving is one of the key reasons for the development of anxious attachment in children and adults (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Bowlby, 1973; 1980; Simpson & Belsky, 2016).

Consistency in maternal sensitivity may have substantial practical implications for adult romantic relationship functioning. For example, the median rating on relationship effectiveness for people whose mothers engaged in more consistent sensitive care (e.g., low fluctuations) was a score of 5, the highest possible score on relationship effectiveness. This indicates that these people effectively engage with others, are able to show and receive love and care, and recover effectively from conflict. Conversely, the median rating on relationship effectiveness for people whose mothers engaged in less consistent sensitive care (e.g., high fluctuations) was a score of 3, the midpoint of the scale for relationship effectiveness. This indicates that these people can form and maintain relationships, but their relationships tend to lack deep care and love and they often struggle to recover from conflict. In essence, consistency of maternal sensitivity differentiates between those who are highly capable of establishing and maintaining stable, secure, and fulfilling relationships from those who can form relationships but have more difficulty establishing and maintaining high-quality, fulfilling relationships that thrive over time.

Nonlinear processes, such as within-person variability, are central to attachment theory and are essential to understanding the enduring effects of early experiences more fully. We already know a great deal about how early experiences can and do shape attachment working models across the life course (e.g., Fraley et al., 2013; T. E. A. Waters et al., 2017). The current research adds to this ample literature by providing support for an oft-discussed but untested hypothesis: that consistency, conceptualized here as fluctuations, in early maternal care prospectively forecasts attachment working models and romantic relationship functioning in adulthood. Future research should utilize more nonlinear techniques, including but not limited to fluctuations in maternal attachment-relevant behaviors, to more precisely and rigorously test promising life-course models and hypotheses. Future research should also collect and model longitudinal data gathered from individuals across their entire lives, starting from the beginning of life. The utility of advanced nonlinear techniques such as within-person variability or partner synchrony will not be fully appreciated until enough data and findings are available from which to draw broad, reliable conclusions.

Caveats

Despite the strengths of this study, future studies must continue to advance our understanding of enduring nonlinear effects. The current research relied on a modest-sized sample of participants, all of whom had initially high-risk backgrounds. Although this most likely makes detecting variability in maternal sensitivity easier, the current sample does not permit us to know whether or how variability in early caregiving experiences might differentially impact individuals from more privileged backgrounds. For example, individuals who grow up with multiple consistent caregivers or more financial resources/stability might be buffered from the effects of fairly large fluctuations in maternal caregiving to the extent that other assets offset variability in the care provided by their primary caregivers. Additionally, our measure of maternal sensitivity was derived from different mother–child tasks at different points in development. Although these tasks and the maternal sensitivity codes fit well together both conceptually and statistically, some fluctuations may have resulted from differences between the tasks rather than from differences in parenting quality across time. Future research should use standardized behavioral assessments of maternal sensitivity to determine whether task-type contributes significantly to fluctuations in caregiving behaviors. Due to sample size limitations, we could not examine the interaction between mean levels and fluctuations in maternal sensitivity with sufficient power. The effect of fluctuations in maternal sensitivity might have a moderating effect on mean levels such that high fluctuations paired with low mean levels of maternal sensitivity lead to worse outcomes compared to high fluctuations paired with high mean levels of maternal sensitivity. Future research should address this issue by collecting larger samples in which interactions between mean levels and fluctuations can be tested with sufficient power. Finally, due to the lack of relevant data from our participants, we could not examine or describe our sample based on sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability status. Future research should assess these characteristics to better understand if/how such demographic features influence the effect of fluctuations in maternal sensitivity on later life outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current research contributes to our understanding of both attachment theory and nonlinear methods by confirming that variability in early life maternal sensitivity is as, if not more, predictive of secure base script knowledge and romantic relationship effectiveness than overall quality of care, confirming Bowlby’s and Ainsworth’s original theorizing. Our findings also reveal that nonlinear models of early caregiving experiences uniquely predict relationship outcomes over time, above and beyond what traditional linear models investigating mean level effects have documented. Finally, this research showcases a novel methodological approach that advances research on attachment theory and the long-term impact of key early life experiences.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the a National Institute on Aging grant (Award Number R01 AG039453) awarded to Jeffry A. Simpson.

The data used in the research are available. The data can be obtained by emailing: eller091@umn.edu. The materials used in the research are available. The materials can be obtained in the Online Supplemental Materials or by emailing: eller091@umn.edu.

Footnotes

Open research statement

As part of IARR’s encouragement of open research practices, the authors have provided the following information: This research was pre-registered. The aspects of the research that were pre-registered were hypotheses and data analytic method. The registration was submitted to and approved by the Primary Investigators and staff of the Minnesota Longitudinal Study of Risk and Adaptation.

Supplemental material

Supplement material for this article is available in online.

There are several methods for computing within-person fluctuations in longitudinal samples (e.g., Girme, 2020). We chose within-person standard deviations because (a) they are the most widely and consistently used method for calculating fluctuation scores, (b) they are an easy-to-interpret method for calculating fluctuation scores, (b) they are an easy-to-interpret method for calculating fluctuation scores, and (c) using this method did not produce different findings than other methods (e.g., extracting Bayes time slopes; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) that we modeled.

We also ran models examining only the semi-structured early childhood maternal sensitivity assessments (e.g., when participants were 3, 6, 24, and 42 months) and examining only the early childhood maternal sensitivity assessments (e.g., all assessments except for that at 13 years). The pattern of results did not differ significantly from those when all assessments were included. In addition, we examined AAIsbs at age 19 and 26 individually before aggregating them. Once again, the pattern of results did not differ significantly from those when the 19- and 26-year assessments were aggregated.

References

- Ainsworth MS, Blehar M, Waters E, & Wall S (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT (1995). The effects of postpartum depression on maternal-infant interaction: A meta-analysis. Nursing Research, 44(5), 298–304. 10.1097/00006199-199509000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, & Fearon RM (2002). Infant–mother attachment security, contextual risk, and early development: A moderational analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 14(2), 293–310. 10.1017/S0954579402002067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Nissim G, Vaccaro S, Harris JL, & Lindhiem O (2018). Association between maternal depression and maternal sensitivity from birth to 12 months: A meta-analysis. Attachment & Human Development, 20(6), 578–599. 10.1080/14616734.2018.1430839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth AT, Macdonald JA, & Youssef GJ (2018). Contextual stress and maternal sensitivity: A meta-analytic review of stress associations with the Maternal Behavior Q-Sort in observational studies. Developmental Review, 48(1), 145–177. 10.1016/j.dr.2018.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1969/1982). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1979). The making and breaking of af-fectional bonds. London: Tavistock. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1980). Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss: Sadness and depression. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, & Caldwell BM (1984). The HOME Inventory and family demographics. Developmental Psychology, 20(2), 315–320. 10.1037/0012-1649.20.2.315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Matestic P, Von Stauffenberg C, Mohan R, & Kirchner T (2007). Trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity, and children’s functioning at school entry. Developmental Psychology, 43(5), 1202–1215. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, McElwain NL, Berry D, & Emery HT (2019). Within-person fluctuations in maternal sensitivity and child functioning: Moderation by child temperament. Journal of Family Psychology, 33(7), 857–867. 10.1037/fam0000564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm JS (1996). The evolutionary ecology of attachment organization. Human Nature, 7(1), 1–37. 10.1007/BF02733488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane R, & Robertson A (1973). The life events inventory: A measure of the relative severity of psycho-social stressors. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 17(2), 135–139. 10.1016/0022-3999(73)90014-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, & Donnellan MB (2007). An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 175–199. 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland BR, Breitenbucher M, & Rosenberg D (1980). Prospective study of the significance of life stress in the etiology of child abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 48(2), 195–205. 10.1037/0022-006X.48.2.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AK, Waters TE, Young ES, Englund MM, Carlson EE, Roisman GI, & Simpson JA (2019). Early maternal sensitivity, attachment security in young adulthood, and cardiometabolic risk at midlife. Attachment & Human Development, 21(1), 70–86. 10.1080/14616734.2018.1541517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Roisman GI, & Haltigan JD (2013). The legacy of early experiences in development: formalizing alternative models of how early experiences are carried forward over time. Developmental Psychology, 49(1), 109–126. 10.1037/a0027852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George C, Kaplan N, & Main M (1984). Attachment interview for adults. Unpublished interview. University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Girme YU (2020). Step out of line: Modeling nonlinear effects and dynamics in close-relationships research. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(4), 351–357. 10.1177/0963721420920598 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Girme YU, Jones RE, Fleck C, Simpson JA, & Overall NC (2021). Infants’ attachment insecurity predicts attachment-relevant emotion regulation strategies in adulthood. Emotion, 21(2), 260–272. 10.1037/emo0000721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa A, Dougherty L, Durbin CE, Laptook R, Torpey D, & Klein DN (2014). Emotion recognition in preschool children: Associations with maternal depression and early parenting. Development and Psychopathology, 26(1), 159–170. 10.1017/S0954579413000928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, Supple AJ, O’Brien M, Calkins SD, Haltigan JD, Wong MS, & Fortuna K (2015). Antecedents of maternal sensitivity during distressing tasks: Integrating attachment, social information processing, and psychobiological perspectives. Child Development, 86(1), 94–111. 10.1111/cdev.12288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhiem O, Bernard K, & Dozier M (2011). Maternal sensitivity: Within-person variability and the utility of multiple assessments. Child Maltreatment, 16(1), 41–50. 10.1177/1077559510387662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning LB (2019). The relation between changes in maternal sensitivity and attachment from infancy to 3 years. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(6), 1731–1746. 10.1177/0265407518771217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raby KLKL, Roisman GI, Fraley RC, & Simpson JA (2015a). The enduring predictive significance of early maternal sensitivity: Social and academic competence through age 32 years. Child Development, 86(3), 695–708. 10.1111/cdev.12325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raby KL, Roisman GI, Simpson JA, Collins WA, & Steele RD (2015b). Greater maternal insensitivity in childhood predicts greater electrodermal reactivity during conflict discussions with romantic partners in adulthood. Psychological Science, 26(3), 348–353. 10.1177/0956797614563340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, & Bryk AS (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (Vol. 1). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Collins WA, Sroufe LA, & Egeland B (2005). Predictors of young adults’ representations of and behavior in their current romantic relationship: Prospective tests of the prototype hypothesis. Attachment & Human Development, 7(2), 105–121. 10.1080/14616730500134928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Version 0.5–12 (BETA). Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. 10.18637/jss.v048.i02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, & Belsky J (2016). Attachment theory within a modern evolutionary framework. In Cassidy J, & Shaver PR (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (3rd ed., pp. 91–116). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Collins WA, Tran S, & Haydon KC (2007). Attachment and the experience and expression of emotions in adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(2), 355–367. 10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson EA, & Collins WA (2005). The development of the person: The Minnesota study of risk and adaptation from birth to adulthood. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens G, & Cho JH (1985). Socioeconomic indexes and the new 1980 census occupational classification scheme. Social Science Research, 14(2), 142–168. 10.1016/0049-089x(85)90008-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens G, & Featherman DL (1981). A revised socioeconomic index of occupational status. Social Science Research, 10(4), 364–395. 10.1016/0049-089X(81)90011-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waters TEA, Facompré CR, Dagan O, Martin J, Johnson WF, Young ES, Simpson JA, & Roisman GI (2020). Convergent validity and stability of secure base script knowledge from young adulthood to midlife (pp. 1–21). Attachment & Human Development. 10.1080/14616734.2020.1832548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters TE, & Roisman GI (2019). The secure base script concept: An overview. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25(1), 162–166. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters TE, Ruiz SK, & Roisman GI (2017). Origins of secure base script knowledge and the developmental construction of attachment representations. Child Development, 88(1), 198–209. 10.1111/cdev.12571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters HS, & Waters E (2006). The attachment working models concept: Among other things, we build script-like representations of secure base experiences. Attachment & Human Development, 8(3), 185–197. 10.1080/14616730600856016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.