Abstract

Firearms are now the leading cause of death among youth in the United States, with rates of homicide and suicide rising even more steeply during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. These injuries and deaths have wide-ranging consequences for the physical and emotional health of youth and families. While pediatric critical care clinicians must treat the injured survivors, they can also play a role in prevention by understanding the risks and consequences of firearm injuries; taking a trauma-informed approach to the care of injured youth; counseling patients and families on firearm access; and advocating for youth safety policy and programming.

Keywords: Firearm injury, Public health, Injury prevention, Youth

Key points

-

•

Firearms are now the leading cause of death for youth in the United States. The most common cause of youth firearm death is homicide. Boys account for 90% of deaths, and youth of color are affected disproportionately.

-

•

The presence of firearms in the home increases youth risk of homicide, suicide, and unintentional injury, particularly when firearms are stored loaded or unlocked.

-

•

Families are open to counseling on firearm storage from clinicians, and counseling can reduce risk of injury, particularly when combined with the distribution of secure storage devices.

-

•

Trauma informed approaches, including dedicated support for recovering youth, can improve outcomes after firearm injury.

Introduction

Firearms are the leading cause of death among children and adolescents (youth) in the United States, ending more lives than cancer, congenital anomalies, or chronic respiratory disease.1 The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has ushered in escalating risks for youth and families. Rising community gun violence has impacted youth disproportionately2 and youth suicides have risen,3 particularly among Black youth.4 Moreover, 2.9% of US adults became firearm owners for the first time during the pandemic, exposing more than 5 million youth to the risks of firearms in the home.5, 6, 7 The escalation in firearm-related death for youth is particularly disturbing because of how preventable these deaths are.

Pediatric critical care clinicians are highly skilled at providing life-saving care to injured youth. While organized systems of trauma care and sophisticated critical care units are essential elements of treating the disease of firearm injury, they are not sufficient. Clinicians have an ethical obligation to address firearm violence as they would any other health problem.8 Therefore, we must move upstream to prevent firearm-related harm before it brings children to our intensive care units, and we must think beyond the unit to focus on healing the scars of youth, families, and communities.9

The reasons for the escalation of firearm injury and death among youth are complex and crosssocietal sectors from social policy to education to health care and beyond. The complexity of the issue is challenging but also opens up a wealth of potential points of intervention that can be designed, implemented, and evaluated. In this paper, we seek to equip pediatric critical care clinicians with necessary information about the epidemiology of firearm-related harm and related costs, risk and protective factors, the impact of firearm violence on youth, and public health approaches to prevent firearm-related harm to inform actions that pediatric critical care clinicians can take.

Epidemiology of Firearm Injury Among Youth

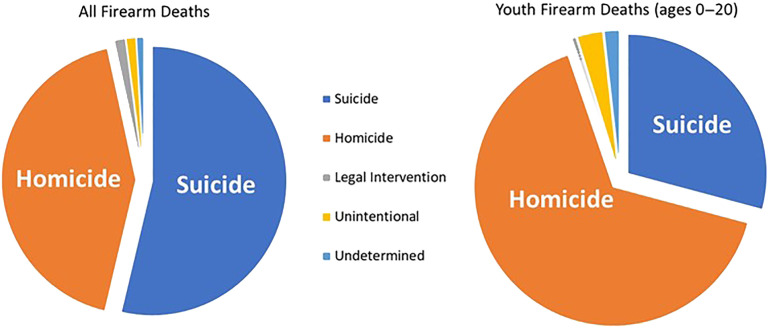

Youth accounted for almost 12% of firearm deaths in 2020, with a death rate of 6.32 per 100,000 for youth below age 21.10 While suicide is the leading intent of firearm death in the general population, in youth, homicides account for the majority of deaths (Fig. 1 ). The proportion of youth homicides that are firearm-related increased significantly from 1980 to 2016.11

Fig. 1.

Firearm deaths according to the intention of injury 2020 firearm deaths. Firearm deaths for all ages n = 45,222. Youth firearm deaths (ages 0–20) n = 5414.

Data from WISQARS. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.htm.

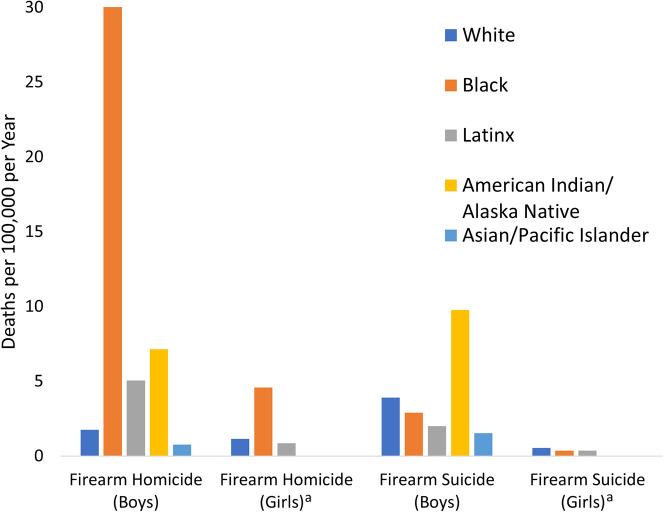

The public health epidemic of firearm-related death is dominated by boys, with 4710 boys dying as compared with 704 girls in 2020. Firearm-related deaths are not evenly distributed across race/ethnicity (Fig. 2 ). Including all intents of injury, Black boys have the highest death rate per 100,000 (35.05) followed by American Indian/Alaska Native (18.58), Latino (7.54), White (6.13), and Asian/Pacific Islander boys (2.49).10 The pattern changes for firearm suicide, with American Indian/Native Alaskan boys dominating followed by White and Black boys. Among girls, Black girls bear a disproportionate burden of firearm homicide. This disparity extends to firearm-related deaths due to legal intervention (shootings carried out by law enforcement officers in the course of their duties). Between 2003 and 2018, Black and Hispanic adolescents between 12 and 17 years of age had higher risks of firearm-related deaths due to legal intervention than their non-Hispanic White peers (RR 6.01 and 2.78, respectively).12

Fig. 2.

Firearm Homicide and Suicide by Race and Ethnicity for Boys and Girls. aRates for American Indian/Alaska Native and Asian/Pacific Islander girls unstable and not reported.

There is no comprehensive data source for nonfatal firearm injuries. Limited data on emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations suggest that more than 4 times as many youth survive firearm injuries than die.13 This case fatality ratio is lower for youth than for adults, largely because youth incur more unintentional injuries, which rarely lead to death. More than 4 in 5 nonfatal firearm injuries are in adolescents, and more than 4 in 5 injured youth are boys. Assaults account for 71% of nonfatal firearm injuries in youth, but unintentional injuries are more common in rural areas.14 , 15 Racial disparities mirror those present in homicides,15, 16, 17 and a disproportionate share of injuries occur in low income neighborhoods,17 and in the South.18

Risk and Protective Factors

A public health approach to youth firearm injury prevention focuses on boosting protective factors and reducing risk factors at the individual, family, community, environmental, and societal levels. This understanding can aid the development, implementation, and scale-up of tailored interventions. A recent scoping review from the Firearm safety Among Children and Teens (FACTS) Consortium highlights that much of youth firearm violence literature has focused on individual-level risk factors (ie, beliefs, attitudes, behaviors).19 Substance use, truancy, low academic achievement, delinquency, and firearm carriage are all notable risk factors for interpersonal firearm violence victimization. Specific to firearm suicide, study results are inconsistent as to whether mental health diagnosis, treatment, and prior attempts affect youth’s risk for firearm suicide.19 Peer-related factors also influence the risk of firearm injury for adolescents, who are more likely to carry a firearm if their peers do, or if they expect to encounter other youth who are carrying.19 , 20

At the household level, a well-established body of literature highlights the risks associated with the presence of firearms in the home for youth firearm unintentional injury, homicide, and suicide.19, 21, 22 These risks are amplified when firearms are stored unlocked or loaded. Approximately 30 million children live in US households with firearms, with 4.6 million youth living in households with loaded and unlocked firearms.23 Updated estimates suggest that adolescents’ risk of dying by suicide is at least three times higher living in a home with a firearm versus without.5 , 24 Moreover, an examination of National Violent Death Reporting System data across five US states found that for 77% of youth who died by firearm suicide, the firearms used mostly came from parents, but also grandparents, brothers, and parents’ intimate partners.6 Though older children are at higher risk for injury, households with only older children are more likely to store at least one firearm loaded and unlocked compared with households with younger children.25

Youth from communities with high levels of socioeconomic disadvantage are at the highest risk for firearm injuries.17 Black youth disproportionately live in historically racialized spaces with increased exposure to living conditions shaping violence and contributing to high rates of firearm homicide.26 Multiple neighborhood-level factors fuel violence inequities, including limited economic opportunities, alcohol outlets, narcotic sales, and high concentrations of firearms.17 , 19 , 27 Recent findings indicate that higher county poverty concentration is associated with youth firearm-related deaths across all intents.28 Youth living in rural counties are at higher risk for firearm-related suicides and unintentional deaths, but lower risk for homicide; differences may be attributable to lethal means access, social isolation, or limited access to mental health services.28 The causal pathways by which poverty and structural racism lead to injury are complex, and interventions to disrupt this trajectory are sorely needed.29

Surprisingly little is known about protective factors for youth firearm outcomes.19 Parental monitoring and involvement,30 future orientation,31 higher levels of school attachment, exposure to school-based drug and violence prevention programs, and stricter state-level firearm policies are associated with decreased propensity to carry firearms in cross-sectional studies.20

Costs of Youth Firearm Injury

As the incidence of firearm injury rises in youth, so do the economic costs to individuals, families, and the health care system. The Government Accountability Office estimates the total annual costs of acute care for firearm injuries in the US for all intents and age groups is approximately $1 billion annually, with Medicaid accounting for approximately half of these costs.32

Direct health care costs include acute care in the ED for most injuries, but care and accompanying costs vary widely by anatomic injury. Even simple fractures may require physical therapy, prescription drugs, or durable medical equipment such as crutches, scooters, or wheelchairs. Injuries to the organs of the chest and abdomen can require complex surgical management and prolonged inpatient hospitalizations, as well as subsequent rehabilitation. Injuries to the head or spinal cord can require prolonged recovery or result in permanent disability. The mental health impacts of firearm injury can lead to the need for mental and behavioral health care which may extend beyond the individual to victims of secondary trauma stemming from the firearm injury itself: family, friends, and community.32

For 2016 to 2017, the average cost of an ED visit for firearm injury was $1478 and the average cost of an inpatient hospitalization was $34,791. Taken together, total acute care costs for youth were $1,153,186,636. Readmissions are common after firearm injury, and affect 4.5% of youth,33 with an average cost of $8311.34

There are limited data on long-term costs for youth who survive firearm injury. Costs are difficult to track, as individuals frequently change insurance carriers. It is difficult to link services to the initial injury, particularly when it comes to behavioral health.32 Song and colleagues found that in the year after a nonfatal firearm injury, medical spending increased more than 400% among survivors, and also increased 4.2% among family members of survivors, speaking to the wider burden of these injuries and care.35 Pulcini and colleagues used data from Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program to track health care spending for youth ages 0 to 17 who survived firearm injuries, identifying an increase of $9,084 in health care costs per patient in the year following injury. The greatest increases were seen in self-inflicted injuries.36

Costs of youth firearm injury extend beyond direct medical care. Including legal costs, the price tag rises to $270,399 for each death and $52,585 for each nonfatal injury,37 but little information exists on the impact of lost work for caregivers, or the economic consequences of missed school and disrupted health. The broader costs of firearm violence include not only the need to maintain emergency care systems to treat injured individuals and legal costs, but also lost value of housing and business in neighborhoods impacted by violence. For example, research from The Urban Institute estimated that for every 10 fewer incidents of gun fire, one new business could open, one fewer businesses would close, 20 more jobs could be created, and more than a million dollars of sales could accrue.38

Contextual Impact of Firearm Injury and Exposure to Violence on Youth

Exposure to firearm violence has long-term effects for those who are injured, but also for their peers, families, and communities. Indeed, social network analysis reveals that almost everyone (99.85%) will know a firearm violence victim over the course of a lifetime.39 For youth of color living in communities marginalized by structural racism, these impacts are greatly magnified, making firearm violence both a cause and a consequence of racial disparities in health and well-being. Both direct and indirect exposures can have profound effects on health and well-being over the short- and long-term. Here we examine firearm-related harm on youth within the broader context of firearm violence in homes, communities, and schools.

There is ample evidence of adverse mental health impacts on youth who have been shot, including depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and substance use.40 One in four youth who survive a firearm injury are diagnosed with a new mental health disorder within a year.41 It is essential that care provided to youth from the moment of the shooting to long-term follow-up embrace a holistic, trauma-informed approach, and to provide the support necessary for holistic recovery.

Youth report high levels of exposure to community violence and to firearm violence in particular. Exposures can extend from hearing about events in neighborhoods and directly witnessing an event in addition to being victimized. In one study, 95% of 10 to 16 year olds in Philadelphia reported hearing about, 87% witnessing, and 54% being directly victimized by violence in their communities.42

“They was like, actually like shooting past me. One was standing down the street and the other one was standing up the street and they was actually like firing back and forth. Like it was fires shot back and forth. I was shocked. I had the trash in my hand ‘cause I was putting it out, and I was just shocked. I couldn’t move or nothing ‘cause I couldn’t believe that it was happening.”

Closer proximity to a firearm violence incident and closer relationships to firearm violence victims increase the risk for posttraumatic stress.43

High exposure to firearm violence is associated with high rates of future injury and firearm injury,44 and victimization during adolescence is positively associated with the likelihood of owning a handgun in the future.45 Third graders attending schools located within higher concentration areas of gunshots score lower in standardized state tests.46 Exposure to violence in youth in 9th grade reduces future educational expectations and increases the likelihood of subsequently carrying a firearm.47 Youth are aware of crime in their neighborhoods, and as crime rate increases perceptions of safety decrease.48 , 49 As a consequence youth develop a level of constant vigilance and make moment by moment decisions about how to safely navigate their neighborhoods.50 In some ways, this vigilance is protective, but it can also lead to health-harming biological stress and chronic health problems.51 , 52 Parents in low-resource neighborhoods where violence is common report keeping their children indoors and restricting movement through the environment.53 This can be harmful to healthy growth and development, contribute to lack of exercise and obesity, result in missed school and work, and limit age-appropriate social connections.

Youth reside in family systems, thus firearm violence that affects a parent, sibling, or other close relatives affect youth. Consider, for example, when a youth gains access to an unsecured firearm and unintentionally wounds or kills a sibling or when intimate partner violence involves a firearm. Interpersonal firearm violence is disproportionately borne by young Black men, who are also subject to mass incarceration. Therefore, Black youth living in poverty are indirectly harmed as they often living in homes where fathers have been killed or incarcerated.54 Black men are by far the most likely to be killed by police. In addition to this loss of life, fear of police violence drives adverse mental health, decreased care-seeking and institutional distrust in affected communities.55, 56, 57, 58

The burden of firearm-related harm in society drives the allocation of resources that can negatively affect youth. For example, the potential for violence in schools drives decisions to install metal detectors and hire school safety officers drawing resources away from books and extracurricular programs. Just as firearm violence is not evenly distributed, the schools affected are more often in under-resourced, minoritized neighborhoods.

School Shootings and Other Public Mass Shootings

There have been 2,069 school shootings in the US since 1970, killing 684 and injuring another 1937.59 These deaths account for < 1% of youth firearm fatalities, but are nonetheless far too common, and carry enormous weight in the public consciousness. School shootings are preventable. Most shooters showed warning signs; improving community response systems has the potential to save lives.60 Most attackers used weapons obtained in their own homes, indicating that secure storage can act to reduce these shootings as well.60 Licensing laws, magazine limits, and waiting periods may also play a role in decreasing potential shooters’ access to lethal weapons.

Beyond the loss of life, school shootings contribute to posttraumatic stress in survivors and peers,40 generate fear in students, teachers, and parents, and decrease communities’ sense of safety. These shootings have also inspired schools around the country to enact lockdown and active shooter drills. Unfortunately, these drills have been shown to increase stress, with no evidence that they improve safety.61 Likewise, increasing calls to arm staff in schools are likely to increase, rather than decrease, risk of harm.62

Primary Prevention of Youth Firearm Injury

Prevention is a key priority for promoting the overall health of youth. While pediatric critical care clinicians and other healthcare providers specialize in secondary prevention—minimizing harm and reducing adverse consequences once an injury has occurred—the lethality of firearms makes primary prevention paramount. For example, firearms have a 90% case fatality rate for suicide,63 and opportunities for secondary prevention and second chances are scarce.

Interventions to Promote Secure Firearm Storage

Reducing opportunities for youth to access firearms in their homes and the homes of others is a key aspect of prevention for youth suicide, unintentional injury, and assault. Engaging caregivers to increase secure storage in households with youth can prevent injuries and save lives.64 A recent modeling study found that up to 32% of youth firearm deaths could be avoided if 20% of households with at least one firearm unlocked moved to locking all firearms.65 Uptake of storage recommendations has the potential to yield significant reductions in both unintentional injury and suicide.

Health care settings are highly relevant intervention points. Clinician counseling on firearm safety in pediatric settings is generally acceptable to parents,66 , 67 though questions remain about optimal approaches to motivating behavior change (and associated mechanisms) given the complex and socially situated reasons for both firearm ownership and storage.65 , 68, 69, 70 A nonjudgmental, patient-centered approach with explicit framing around the shared goal of youth safety may enhance the acceptability and subsequent effectiveness of these conversations.71, 72, 73 Moreover, counseling can also be tailored to specific injury risk factors, like developmental stages or mental health diagnoses.71

Despite recommendations from multiple leading organizations (eg, American Academy of Pediatrics) that clinicians discuss firearm safety in health care settings,74 uptake of this guidance is low.67 , 75, 76, 77 For example, in one survey of pediatric residents, most respondents indicated never providing firearm-related counseling or only doing so in 1% to 5% of well-child visits, despite agreeing that physicians have a responsibility to counsel on firearm-related risks.77 In a survey of 54 pediatric-focused advance practice nurses, 70.3% reported asking parents about firearms in the home; advanced practice nurses with higher level of education, pediatric certification, and firearm ownership were most likely to conduct screening and teaching.78 Identified barriers to counseling include guidance on appropriate language, correct use of locking devices, technical aspects of firearms, and time during visits, highlighting the need for implementation strategies to increase routine delivery.75 , 76 Training resources are available through the AAP,79 Zero Suicide Institute,80 and the BulletPoints Project.81

Evaluations of the effectiveness of clinician counseling to reduce youth household firearm access have been limited by sample size, reliance on self-reported storage practices, and lack of measurement of injury outcomes.82 However, several studies indicate a positive effect of clinician counseling when accompanied by free locking device provision.68 , 83 , 84 The SAFETY study, a clustered ED-based, multisite trial, evaluated whether a brief counseling intervention reduced at-risk youths’ access to lethal means.85 Hospitals were provided with free handgun safes, cable locks, and medication lockboxes to offer families. Intervention adoption led to a twofold improvement in firearm storage after caregivers returned home from the ED; however, results for improved firearm safety did not persist.85 One takeaway from this study was the importance of locking device features.86 With a variety of commercially available options, further research should leverage principles of user-centered design to elicit firearm owners’ preferences for locking devices to facilitate usage.86, 87, 88, 89

Interventions must also be developed and implemented outside of health care settings to expand their reach to firearm owners and individuals with less access to clinical care.88 Community-based interventions to improve firearm safety include locking device giveaways, community education programs, and firearm buyback programs.90 Study results generally suggest improved self-reported storage following device distribution regardless of setting, with mixed results on secure storage education programs.90 Since the 1990s, voluntary buyback programs to reduce the prevalence of firearms in communities have been deployed more broadly across US cities.91 Though buybacks increase the number of firearms relinquished, support is mixed, with further evaluation needed for pediatric injury outcomes.90 , 91

Environmental interventions to prevent youth firearm injury

Researchers have increasingly focused on structural changes in the built environment (eg, blight reduction through the improvement of dilapidated buildings and abandoned properties) in places whereby violence occurs.92 Residential segregation of racially and ethnically minoritized youth in settings of concentrated disadvantage necessitates multilevel interventions that target social and political determinants of firearm injury.17 , 69 , 93 Place-based interventions addressing poverty may confer protection and demonstrate promising impact.26 , 92 , 94 For example, a recent randomized trial demonstrated that both (1) greening and (2) mowing and trash cleanup interventions significantly reduced shootings, with no evidence of violence displacement to nearby areas.95 Well-maintained vacant lots and the presence of parks are associated with a reduction in the odds of adolescent homicide, suggesting potential targets for future urban revitalization strategies.96

The role of firearm policy in preventing youth firearm injury

Youth-focused, evidence-based firearm policy is another component of firearm-related injury prevention at the population level. Child Access Prevention (CAP) laws aim to motivate secure firearm storage by imposing liability on adults who permit children to have unsupervised access to firearms. CAP law provisions vary between states, with different levels of criminal liability conferred for specific situations, such as negligent firearm storage or reckless provision of a firearm to a minor.97 CAP laws are associated with reductions in unintentional firearm injury deaths and firearm suicides, though the magnitude of effects requires further examination.98 , 99 Moreover, more evidence is needed about the features of CAP laws and their implementation that enhance effectiveness.97

Comprehensive background checks are a potential tool to reduce youth firearm carriage and illegal possession. Federal law mandates background checks to determine eligibility for firearm transfers from federally authorized dealers. However, the federal requirements do not extend to private firearm transfers or sales (eg, sales between individuals in person, online, or at gun shows), generating variability in firearm accessibility and availability across states.98 , 100 Thirteen states have laws that mandate background checks at the point of all sales and transfers.97 One recent study found that adolescents in states that require universal background checks at the point of sale are less likely to carry firearms, suggesting that both state and federal laws may work together to reduce adolescent firearm carriage.100 In addition, a 5-year analysis found that states with stricter gun laws, particularly universal background checks for firearm purchases, had lower rates of firearm-related deaths in children.101

Secondary and Tertiary Prevention

Secondary prevention focuses on the prevention of mental health and behavioral sequelae after youth are exposed to firearm injury, and tertiary prevention addresses risks of recurrent firearm injury. While the occurrence of firearm injury is associated with future firearm injury and high rates of posttraumatic stress symptoms, a scoping review found little empirical research on potential secondary prevention interventions to target long-term effects.40 However, hospital-based violence intervention programs have shown promise for improving outcomes and reducing reinjury for youth survivors. These programs use trained lay people who serve as credible messengers, often with shared backgrounds and experience to the patients they treat. Staff provide psychosocial support and case management services to patients and families to help them recover and to help them navigate the health care and social services sector to meet their needs. These programs can meet mental health needs102 and reduce recurrent violent injury, arrests, unemployment, and aggression while improving self-efficacy.103 , 104

Summary: what can pediatric critical care clinicians do?

Pediatric critical care clinicians first and foremost are responsible to provide life-saving and life-affirming care to injured youth and family. Trauma-informed care should be fully integrated within the plan of care. Research has shown that providers across disciplines have positive attitudes, but would benefit from education to enhance their knowledge and competence in delivering trauma-informed care in trauma settings.105 , 106 Training can be considered at the unit or institutional level using existing resources, such as those available on at the National Child Traumatic Stress Network.107 Life-affirming care extends to planning for appropriate physical and psychological follow-up care postdischarge.

The disproportionate burden of firearm violence affects Black youth. Evidence indicates subtle negative descriptors of racialized comments are documented in electronic health records.108 Clinicians would be well-served to self-examine the potential of stigma and judgments about the circumstances surrounding shooting events and their own implicit bias given its known association with quality of care.109

Primary prevention of youth firearm injury is within the purview of all clinicians and communities. Pediatric critical care clinicians should move upstream to prevent the firearm injury from occurring in the first place. For example, discussion and counseling focused on universal risk reduction regarding firearms, as well as specific safety planning in the context of risk can occur anywhere in the health care system. It does not need to be the purview of general pediatricians or psychiatrists alone.81

In this politicized environment of pro-firearm and anti-firearm diatribes, pediatric critical care clinicians bring an important perspective to the conversation because they deal daily with the human anguish of youth who sustain a gunshot wound. It is important to always ask “what can I do?”. Table 1 frames the mnemonic SPEAK UP to provide a sample of concrete strategies and Clinics Care Points that critical care clinicians can take to reduce firearm-related harm.

Table 1.

Speak up: actions that critical care providers can take to reduce firearm-related harm

| S | Separate facts from opinions | Understand the incidence and consequences of youth firearm injury |

| P | Partner with others such as your health system, professional societies & community organizations | Collaborate with community organizations to facilitate community-based prevention and recovery for injured youth |

| E | Educate yourself, your peers, your community, and your leaders | Ex: risks of firearms in the home and the benefits of secure storage |

| A | Advocate using current evidence to achieve the goal to create safe communities | Support evidence-based policy such as CAP laws, and programming, such as storage device distribution |

| K | Know how you will evaluate all interventions and programmatic initiatives | Focus on injury-related outcomes |

| U | Unite on common ground and be inclusive of divergent views | Center youth safety and well-being |

| P | Provide trauma informed care and services to help reintegrate youth into the community | Understand the impact of prior and current trauma on youth and families’ reactions and interactions with the health care team |

Acknowledgments

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr E.J. Kaufman is supported by AHRQ K12-HS026372. Dr K. Hoskins received funding from the National Institute of Mental Health Training Fellowship (T32 MH109433; Mandell/Beidas MPIs).

References

- 1.Goldstick J.E., Cunningham R.M., Carter P.M. Current causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(20):1955–1956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2201761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afif I.N., Gobaud A.N., Morrison C.N., et al. The changing epidemiology of interpersonal firearm violence during the COVID-19 pandemic in Philadelphia, PA. Prev Med. 2022;158:107020. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charpignon M.L., Ontiveros J., Sundaresan S., et al. Evaluation of suicides among US adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(7):724–726. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.California Department of Public Health Suicide in California – data trends in 2020, COVID impact, and prevention strategies. https://www.psnyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Suicide-in-California-Data-Trends-in-2020-COVID-Impact-and-Prevention-Strategies-Slide-Deck.pdf Available at: Accessed June 24, 2022.

- 5.Swanson S.A., Eyllon M., Sheu Y.H., et al. Firearm access and adolescent suicide risk: toward a clearer understanding of effect size. Inj Prev. 2020;2019:043605. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barber C., Azrael D., Miller M., et al. Who owned the gun in firearm suicides of men, women, and youth in five US states? Prev Med. 2022:107066. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller M., Zhang W., Azrael D. Firearm purchasing during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the 2021 national firearms survey. Ann Intern Med. 2021 doi: 10.7326/M21-3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shultz B.N., Tolchin B., Kraschel K.L. The “rules of the road”: ethics, firearms, and the physician’s “lane. J Law Med Ethics. 2020;48(4_suppl):142–145. doi: 10.1177/1073110520979415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hills-Evans K., Mitton J., Sacks C.A. Stop posturing and start problem solving: a call for research to prevent gun violence. AMA J Ethics. 2018;20(1) doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2018.20.1.pfor1-1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-ranging online data for epidemiological research. http://wonder.cdc.gov/ Available at: Accessed May 11, 2016.

- 11.Manley N.R., Huang D.D., Lewis R.H., et al. Caught in the crossfire: 37 Years of firearm violence afflicting America’s youth. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;90(4):623–630. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badolato G.M., Boyle M.D., McCarter R., et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in firearm-related pediatric deaths related to legal intervention. Pediatrics. 2020;146(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-015917. e2020015917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fowler K.A., Dahlberg L.L., Haileyesus T., et al. Firearm injuries in the United States. Prev Med. 2015;79:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufman E.J., Wiebe D.J., Xiong R.A., et al. Epidemiologic trends in fatal and nonfatal firearm injuries in the US, 2009-2017. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(2):237–244. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fowler K.A., Dahlberg L.L., Haileyesus T., et al. Childhood firearm injuries in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20163486. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leventhal J.M., Gaither J.R., Sege R. Hospitalizations due to firearm injuries in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;133(2):219–225. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carter P.M., Cook L.J., Macy M.L., et al. Individual and neighborhood characteristics of children seeking emergency department care for firearm injuries within the PECARN network. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(7):803–813. doi: 10.1111/acem.13200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel S.J., Goyal M., Badolato G., et al. Emergency department visits for pediatric firearm-related injury: by intent of injury. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2_MeetingAbstract):407. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt C.J., Rupp L., Pizarro J.M., et al. Risk and protective factors related to youth firearm violence: a scoping review and directions for future research. J Behav Med. 2019;42(4):706–723. doi: 10.1007/s10865-019-00076-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliphant S.N., Mouch C.A., Rowhani-Rahbar A., et al. A scoping review of patterns, motives, and risk and protective factors for adolescent firearm carriage. J Behav Med. 2019;42(4):763–810. doi: 10.1007/s10865-019-00048-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahlberg L.L., Ikeda R.M., Kresnow M.J. Guns in the home and risk of a violent death in the home: findings from a national study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(10):929–936. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller M., Hemenway D., Azrael D. State-level homicide victimization rates in the US in relation to survey measures of household firearm ownership, 2001–2003. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(3):656–664. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller M., Azrael D. Firearm storage in US households with children: findings from the 2021 national firearm survey. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2148823. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brent D.A., Perper J.A., Moritz G., et al. Psychiatric risk factors for adolescent suicide: a case-control study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(3):521–529. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azrael D., Cohen J., Salhi C., et al. Firearm storage in gun-owning households with children: results of a 2015 national survey. J Urban Health. 2018;95(3):295–304. doi: 10.1007/s11524-018-0261-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bottiani J.H., Camacho D.A., Lindstrom Johnson S., et al. Annual Research Review: youth firearm violence disparities in the United States and implications for prevention. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2021;62(5):563–579. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hohl B.C., Wiley S., Wiebe D.J., et al. Association of drug and alcohol use with adolescent firearm homicide at individual, family, and neighborhood levels. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):317. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barrett J.T., Lee L.K., Monuteaux M.C., et al. Association of county-level poverty and inequities with firearm-related mortality in US youth. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(2):e214822. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellyson A.M., Rivara F.P., Rowhani-Rahbar A. Poverty and firearm-related deaths among US youth. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(2):e214819. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khetarpal S.K., Szoko N., Culyba A.J., et al. Associations between parental monitoring and multiple types of youth violence victimization: a brief report. J Interpers Violence. 2021;4 doi: 10.1177/08862605211035882. 8862605211035882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khetarpal S.K., Szoko N., Ragavan M.I., et al. Future orientation as a cross-cutting protective factor Against multiple forms of violence. J Pediatr. 2021;235:288–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Office U.S.G.A. Firearm injuries: health care service needs and costs. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-515 Available at: Accessed July 17, 2021.

- 33.Wheeler K.K., Shi J., Xiang H., et al. Pediatric trauma patient unplanned 30 Day readmissions. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53(4):765–770. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spitzer S.A., Vail D., Tennakoon L., et al. Readmission risk and costs of firearm injuries in the United States, 2010-2015. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0209896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song Z., Zubizarreta J.R., Giuriato M., et al. Changes in health care spending, use, and clinical outcomes after nonfatal firearm injuries among survivors and family members. Ann Intern Med. 2022 doi: 10.7326/M21-2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pulcini C.D., Goyal M.K., Hall M., et al. Mental health utilization and expenditures for children pre–post firearm injury. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(1):133–135. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The economic cost of gun violence. Everytown research & policy. https://everytownresearch.org/report/the-economic-cost-of-gun-violence/ Available at: Accessed December 17, 2021.

- 38.Is gun violence stunting business growth? Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/features/gun-violence-stunting-business-growth Available at: Accessed June 28, 2022.

- 39.Kalesan B., Weinberg J., Galea S. Gun violence in Americans’ social network during their lifetime. Prev Med. 2016;93:53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ranney M., Karb R., Ehrlich P., et al. What are the long-term consequences of youth exposure to firearm injury, and how do we prevent them? A scoping review. J Behav Med. 2019;42(4):724–740. doi: 10.1007/s10865-019-00035-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oddo E.R., Maldonado L., Hink A.B., et al. Increase in mental health diagnoses among youth with nonfatal firearm injuries. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21(7):1203–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McDonald C.C., Deatrick J.A., Kassam-Adams N., et al. Community violence exposure and positive youth development in urban youth. J Community Health. 2011;36(6):925–932. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9391-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Montgomerie J.Z., Lawrence A.E., LaMotte A.D., et al. The link between posttraumatic stress disorder and firearm violence: a review. Aggression Violent Behav. 2015;21:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tracy M., Braga A.A., Papachristos A.V. The transmission of gun and other weapon-involved violence within social networks. Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38(1):70–86. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxv009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gresham M., Demuth S. Who owns a handgun? An analysis of the correlates of handgun ownership in young adulthood. Crime Delinq. 2020;66(4):541–571. doi: 10.1177/0011128719847457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bergen-Cico D., Lane S.D., Keefe R.H., et al. Community gun violence as a social determinant of elementary school achievement. Soc Work Public Health. 2018;33(7–8):439–448. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2018.1543627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee D.B., Hsieh H.F., Stoddard S.A., et al. Longitudinal pathway from violence exposure to firearm carriage among adolescents: the role of future expectation. J Adolesc. 2020;81:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCray T.M., Mora S. Analyzing the activity spaces of low-income teenagers: how do they perceive the spaces where activities are carried out? J Urban Aff. 2011;33(5):511–528. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wiebe D.J., Guo W., Allison P.D., et al. Fears of violence during morning travel to school. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(1):54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teitelman A., McDonald C.C., Wiebe D.J., et al. Youth’s strategies for staying safe and coping. J Community Psychol. 2010;38(7):874–885. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Theall K.P., Shirtcliff E.A., Dismukes A.R., et al. Association between neighborhood violence and biological stress in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(1):53–60. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kapur G., Stenson A.F., Chiodo L.M., et al. Childhood violence exposure predicts high blood pressure in black American young adults. J Pediatr. 2022;S0022-3476(22):00491–00507. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jacoby S.F., Tach L., Guerra T., et al. The health status and well-being of low-resource, housing-unstable, single-parent families living in violent neighbourhoods in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25(2):578–589. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Race, poverty, and U.S. Children’s exposure to neighborhood incarceration - alexander F. Roehrkasse. 2021. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/23780231211067871 Available at: Accessed June 21, 2022.

- 55.Sewell A.A. The illness associations of police violence: differential relationships by ethnoracial composition. Sociological Forum. 2017;32(S1):975–997. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kerrison E.M., Sewell A.A. Negative illness feedbacks: high-frisk policing reduces civilian reliance on ED services. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(S2):787–796. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lett E., Asabor E.N., Corbin T., et al. Racial inequity in fatal US police shootings, 2015–2020. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;2020:215097. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-215097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bor J., Venkataramani A.S., Williams D.R., et al. Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: a population-based, quasi-experimental study. Lancet. 2018;392(10144):302–310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31130-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Data map. K-12 school shooting database. https://www.chds.us/ssdb/data-map/ Available at: Accessed June 25, 2022.

- 60.Alathari L, Drysdale D, Driscoll S, et al. PROTECTING AMERICA’S SCHOOLS A U.S. SECRET SERVICE ANALYSIS OF TARGETED SCHOOL VIOLENCE. Available at: https://www.secretservice.gov/sites/default/files/2020-04/Protecting_Americas_Schools.pdf.

- 61.Schonfeld D.J., Melzer-Lange M., Hashikawa A.N., et al. Participation of children and adolescents in live crisis drills and exercises. Pediatrics. 2020;146(3) doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-015503. e2020015503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arming teachers introduces new risks into schools. Everytown research & policy. https://everytownresearch.org/report/arming-teachers-introduces-new-risks-into-schools/ Available at: Accessed June 25, 2022.

- 63.Conner A., Azrael D., Miller M. Suicide case-fatality rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014: a nationwide population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(2):885–895. doi: 10.7326/M19-1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mann J.J., Michel C.A., Auerbach R.P. Improving suicide prevention through evidence-based strategies: a systematic review. AJP. 2021;178(7):611–624. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Monuteaux M.C., Azrael D., Miller M. Association of increased safe household firearm storage with firearm suicide and unintentional death among US youths. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(7):657–662. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Knoepke C., Allen A., Ranney M., et al. Loaded questions: internet commenters’ opinions on physician-patient firearm safety conversations. WestJEM. 2017;18(5):903–912. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.6.34849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Garbutt J.M., Bobenhouse N., Dodd S., et al. What are parents willing to discuss with their pediatrician about firearm safety? A parental survey. J Pediatr. 2016;179:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rowhani-Rahbar A., Simonetti J.A., Rivara F.P. Effectiveness of interventions to promote safe firearm storage. Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38(1):111–124. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxv006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Metzl J.M. What guns mean: the symbolic lives of firearms. Palgrave Commun. 2019;5(1):35. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Betz M.E., Anestis M.D. Firearms, pesticides, and suicide: a look back for a way forward. Prev Med. 2020;138:106144. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Haasz M., Boggs J.M., Beidas R.S., et al. Firearms, physicians, families, and kids: finding words that work. J Pediatr. 2022;247:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hoskins K., Johnson C., Davis M., et al. A mixed methods evaluation of parents’ perspectives on the acceptability of the S.A.F.E. Firearm program. J Appl Res Child Informing Policy Child Risk. 2022;12(2) https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol12/iss2/2 Available at: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fuzzell L.N., Dodd S., Hu S., et al. An informed approach to the development of primary care pediatric firearm safety messages. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-03101-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Council on injury, violence, and poison prevention executive committee Firearm-related injuries affecting the pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e1416–e1423. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Roszko P.J.D., Ameli J., Carter P.M., et al. Clinician attitudes, screening practices, and interventions to reduce firearm-related injury. Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38(1):87–110. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxv005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ketabchi B., Gittelman M.A., Southworth H., et al. Attitudes and perceived barriers to firearm safety anticipatory guidance by pediatricians: a statewide perspective. Inj Epidemiol. 2021;8(S1):21. doi: 10.1186/s40621-021-00319-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hoops K., Crifasi C. Pediatric resident firearm-related anticipatory guidance: why are we still not talking about guns? Prev Med. 2019;124:29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cho A.N., Dowdell E.B. Unintentional gun violence in the home: a survey of pediatric advanced practice nurses’ preventive measures. J Pediatr Health Care. 2020;34(1):23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2019.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Safer: storing firearms prevents harm - AAP. https://shop.aap.org/safer-storing-firearms-prevents-harm/ Available at: Accessed June 23, 2022.

- 80.Zero suicide. https://zerosuicidetraining.edc.org/ Available at: Accessed June 23, 2022.

- 81.The BulletPoints Project. https://www.bulletpointsproject.org/ Available at: Accessed June 23, 2022.

- 82.Conner A., Azrael D., Miller M. In: Pediatric firearm injuries and fatalities : the clinician’s guide to policies and approaches to firearm harm prevention. Lee L.K., Fleegler E.W., editors. Springer International Publishing; Switzerland: 2021. Access to firearms and youth suicide in the US: implications for clinical interventions; pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Barkin S.L., Finch S.A., Ip E.H., et al. Is office-based counseling about media use, timeouts, and firearm storage effective? Results from a cluster-randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):e15–e25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Carbone P.S., Clemens C.J., Ball T.M. Article. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(11):1049. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.11.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Miller M., Salhi C., Barber C., et al. Changes in firearm and medication storage practices in homes of youths at risk for suicide: results of the SAFETY study, a clustered, emergency department–based, multisite, stepped-wedge trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(2):194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barber C., Azrael D., Berrigan J., et al. Selection and use of firearm and medication locking devices in a lethal means counseling intervention. Crisis. 2022 doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Beidas R.S., Rivara F., Rowhani-Rahbar A. Safe firearm storage: a call for research informed by firearm stakeholders. Pediatrics. 2020;146(5):e20200716. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Simonetti J., Simeona C., Gallagher C., et al. Preferences for firearm locking devices and device features among participants in a firearm safety event. WestJEM. 2019;20(4):552–556. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2019.5.42727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lyon A.R., Bruns E.J. User-centered redesign of evidence-based psychosocial interventions to enhance implementation—hospitable soil or better seeds? JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(1):3–4. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.For the FACTS Consortium, Ngo Q.M., Sigel E., et al. State of the science: a scoping review of primary prevention of firearm injuries among children and adolescents. J Behav Med. 2019;42(4):811–829. doi: 10.1007/s10865-019-00043-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hazeltine M.D., Green J., Cleary M.A., et al. A review of gun buybacks. Curr Trauma Rep. 2019;5(4):174–177. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kondo M.C., Andreyeva E., South E.C., et al. Neighborhood interventions to reduce violence. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39(1):253–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Branas C.C., Reeping P.M., Rudolph K.E. Beyond gun laws—innovative interventions to reduce gun violence in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(3):243–244. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dong B., Branas C.C., Richmond T.S., et al. Youth’s daily activities and situational triggers of gunshot assault in urban environments. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(6):779–785. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Moyer R., MacDonald J.M., Ridgeway G., et al. Effect of remediating blighted vacant land on shootings: a citywide cluster randomized trial. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(1):140–144. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Culyba A.J., Jacoby S.F., Richmond T.S., et al. Modifiable neighborhood features associated with adolescent homicide. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(5):473–480. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Capozzi Lindsay. Preventing unintentional firearm injury & death among youth: examining the evidence. https://policylab.chop.edu/evidence-action-briefs/preventing-unintentional-firearm-injury-death-among-youth-examining-evidence Available at: Accessed June 23, 2022.

- 98.For the FACTS Consortium, Zeoli A.M., Goldstick J., et al. The association of firearm laws with firearm outcomes among children and adolescents: a scoping review. J Behav Med. 2019;42(4):741–762. doi: 10.1007/s10865-019-00063-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Miller M., Zhang W., Rowhani-Rahbar A., et al. Child access prevention laws and firearm storage: results from a national survey. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(3):333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Timsina L.R., Qiao N., Mongalo A.C., et al. National instant criminal background check and youth gun carrying. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1):e20191071. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Goyal M.K., Badolato G.M., Patel S.J., et al. State gun laws and pediatric firearm-related mortality. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2):e20183283. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Juillard C., Smith R., Anaya N., et al. Saving lives and saving money: hospital-based violence intervention is cost-effective. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(2):252–258. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cooper C., Eslinger D.M., Stolley P.D. Hospital-based violence intervention programs work. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 2006;61(3):534–540. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000236576.81860.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cheng T.L., Haynie D., Brenner R., et al. Effectiveness of a mentor-implemented, violence prevention intervention for assault-injured youths presenting to the emergency department: results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122(5):938–946. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kassam-Adams N., Rzucidlo S., Campbell M., et al. Nurses’ views and current practice of trauma-informed pediatric nursing care. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(3):478–484. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bruce M.M., Kassam-Adams N., Rogers M., et al. Trauma Providersʼ knowledge, views, and practice of trauma-informed care. J Trauma Nurs. 2018;25(2):131–138. doi: 10.1097/JTN.0000000000000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.The National Child Traumatic Stress Network The national child traumatic stress network. https://www.nctsn.org/ Accessed June 28, 2022.

- 108.Sun M., Oliwa T., Peek M.E., et al. Negative patient descriptors: documenting racial bias in the electronic health record. Health Aff. 2022;41(2):203–211. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.FitzGerald C., Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]