Abstract

Background

Among people with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD) who are engaged in clinical care, prescription rates of psychotropic medications are high, despite the fact that medication use is off‐label as a treatment for BPD. Nevertheless, people with BPD often receive several psychotropic drugs at a time for sustained periods.

Objectives

To assess the effects of pharmacological treatment for people with BPD.

Search methods

For this update, we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, 14 other databases and four trials registers up to February 2022. We contacted researchers working in the field to ask for additional data from published and unpublished trials, and handsearched relevant journals. We did not restrict the search by year of publication, language or type of publication.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing pharmacological treatment to placebo, other pharmacologic treatments or a combination of pharmacologic treatments in people of all ages with a formal diagnosis of BPD. The primary outcomes were BPD symptom severity, self‐harm, suicide‐related outcomes, and psychosocial functioning. Secondary outcomes were individual BPD symptoms, depression, attrition and adverse events.

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors independently selected trials, extracted data, assessed risk of bias using Cochrane's risk of bias tool and assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach. We performed data analysis using Review Manager 5 and quantified the statistical reliability of the data using Trial Sequential Analysis.

Main results

We included 46 randomised controlled trials (2769 participants) in this review, 45 of which were eligible for quantitative analysis and comprised 2752 participants with BPD in total. This is 18 more trials than the 2010 review on this topic. Participants were predominantly female except for one trial that included men only. The mean age ranged from 16.2 to 39.7 years across the included trials. Twenty‐nine different types of medications compared to placebo or other medications were included in the analyses. Seventeen trials were funded or partially funded by the pharmaceutical industry, 10 were funded by universities or research foundations, eight received no funding, and 11 had unclear funding.

For all reported effect sizes, negative effect estimates indicate beneficial effects by active medication. Compared with placebo, no difference in effects were observed on any of the primary outcomes at the end of treatment for any medication.

Compared with placebo, medication may have little to no effect on BPD symptom severity, although the evidence is of very low certainty (antipsychotics: SMD ‐0.18, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.45 to 0.08; 8 trials, 951 participants; antidepressants: SMD −0.27, 95% CI −0.65 to 1.18; 2 trials, 87 participants; mood stabilisers: SMD −0.07, 95% CI −0.43 to 0.57; 4 trials, 265 participants).

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of medication compared with placebo on self‐harm, indicating little to no effect (antipsychotics: RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.15 to 2.84; 2 trials, 76 participants; antidepressants: MD 0.45 points on the Overt Aggression Scale‐Modified‐Self‐Injury item (0‐5 points), 95% CI −10.55 to 11.45; 1 trial, 20 participants; mood stabilisers: RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.48; 1 trial, 276 participants).

The evidence is also very uncertain about the effect of medication compared with placebo on suicide‐related outcomes, with little to no effect (antipsychotics: SMD 0.05, 95 % CI −0.18 to 0.29; 7 trials, 854 participants; antidepressants: SMD −0.26, 95% CI −1.62 to 1.09; 2 trials, 45 participants; mood stabilisers: SMD −0.36, 95% CI −1.96 to 1.25; 2 trials, 44 participants).

Very low‐certainty evidence shows little to no difference between medication and placebo on psychosocial functioning (antipsychotics: SMD −0.16, 95% CI −0.33 to 0.00; 7 trials, 904 participants; antidepressants: SMD −0.25, 95% CI ‐0.57 to 0.06; 4 trials, 161 participants; mood stabilisers: SMD −0.01, 95% CI ‐0.28 to 0.26; 2 trials, 214 participants).

Low‐certainty evidence suggests that antipsychotics may slightly reduce interpersonal problems (SMD −0.21, 95% CI −0.34 to ‐0.08; 8 trials, 907 participants), and that mood stabilisers may result in a reduction in this outcome (SMD −0.58, 95% CI ‐1.14 to ‐0.02; 4 trials, 300 participants). Antidepressants may have little to no effect on interpersonal problems, but the corresponding evidence is very uncertain (SMD −0.07, 95% CI ‐0.69 to 0.55; 2 trials, 119 participants).

The evidence is very uncertain about dropout rates compared with placebo by antipsychotics (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.38; 13 trials, 1216 participants). Low‐certainty evidence suggests there may be no difference in dropout rates between antidepressants (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.76; 6 trials, 289 participants) and mood stabilisers (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.15; 9 trials, 530 participants), compared to placebo.

Reporting on adverse events was poor and mostly non‐standardised. The available evidence on non‐serious adverse events was of very low certainty for antipsychotics (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.29; 5 trials, 814 participants) and mood stabilisers (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.01; 1 trial, 276 participants). For antidepressants, no data on adverse events were identified.

Authors' conclusions

This review included 18 more trials than the 2010 version, so larger meta‐analyses with more statistical power were feasible. We found mostly very low‐certainty evidence that medication may result in no difference in any primary outcome. The rest of the secondary outcomes were inconclusive. Very limited data were available for serious adverse events. The review supports the continued understanding that no pharmacological therapy seems effective in specifically treating BPD pathology. More research is needed to understand the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of BPD better. Also, more trials including comorbidities such as trauma‐related disorders, major depression, substance use disorders, or eating disorders are needed. Additionally, more focus should be put on male and adolescent samples.

Plain language summary

What are the benefits and risks of medication for people with borderline personality disorder?

Key messages

This review is an update of a previous review on the same topic published in 2010. Although this review includes an additional 18 studies, the conclusions remain the same: there are probably no benefits and risks of medications for borderline personality disorder (BDP), but the evidence is unclear.

Better and larger studies comparing the effects of medication with placebo are needed. Such studies should focus on men, adolescents and those with additional psychiatric diagnoses.

What is BPD?

BPD affects how a person interacts with others and understands one's self. Although its exact causes are unclear, it is thought to result from a combination of genetic and environmental factors (e.g. stressful or traumatic life events when growing up). Approximately 2% of adults and 3% of adolescents are affected.

The symptoms of BPD can be grouped into four categories.

Instability in mood: People with BPD may experience intense feelings that change rapidly and are difficult to control. They may also feel empty and abandoned much of the time.

Cognitive distortions (disturbed patterns of thinking): People with BPD often have upsetting thoughts (e.g. they may think that they are a terrible person). They can have brief episodes of strange experiences (e.g. paranoid ideations or stress‐induced dissociative experiences (i.e. feeling detached from the world around them).

Impulsive behaviour: People with BPD may act impulsively and do things that could harm themselves (e.g. when sad and depressed, they may self‐harm or have suicidal feelings). They might also engage in reckless behaviour (e.g. drug misuse).

Intense but unstable relationships: People with BPD may find it difficult to keep stable relationships (e.g. they may feel very worried about being abandoned and might constantly text or call, or make threats to harm or kill themselves if the person leaves them).

A person only needs to experience five out of nine criteria across these categories to be given a diagnosis of BPD.

How is BPD treated?

No medication has been approved for the treatment of BPD. Nonetheless, a large proportion of people with BPD are given medications for sustained periods of time to alleviate their symptoms. The type of medication given is chosen based on its known effects on other disorders with similar symptoms.

Review question

We wanted to find out whether medications to treat BPD work better or worse than placebo; whether one medication works better than another; or whether one combination of medications work better than another combination of medications.

We wanted to look at how well medications worked on BPD severity, self‐harm, suicide‐related outcomes, and functioning (how well a person performs in everyday life).

We also wanted to find out if medications are associated with any unwanted side effects.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that compared the effects of different medications with placebo, another medication, or a combination of medications, in people diagnosed with BPD.

We compared and summarised the results and rated our confidence in the evidence based on factors such as sample size and methods used. Below, we present the findings from our key comparison: medication versus placebo.

What did we find?

We found 46 studies that involved 2769 people with BPD. The smallest study had 13 participants and the largest 451 participants. There were four studies with more than 100 participants. Except for one study that included men only, all studies included women. The average age of the participants ranged from 16 years to 39 years. Most studies were conducted in outpatient settings (31 studies) in Europe (20 studies) and lasted between four and 52 weeks. Pharmaceutical companies fully or partially funded 16 studies.

The studies looked at the effects of 27 different medications, mostly classified as: 1) antipsychotics (drugs to treat psychosis where a person’s thoughts and mood are so impaired that the person has lost contact with reality); 2) antidepressants (drugs to treat depression); or 3) mood stabilisers (drugs to control and even out mood swings, reducing both high moods (mania) and low moods (depression)).

Compared with placebo, medications seem to make little to no difference to BPD severity, self‐harm, suicide‐related outcomes, and psychosocial functioning. They may make little to no difference as to whether a person continues in a study or drops out. Compared to placebo, antipsychotics and mood stabilisers may make little to no difference to the occurrence of unwanted or harmful effects. No study reported on the side effects of antidepressants.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

Our confidence in the evidence varied between very low and low. The results of future research could differ from the results of this review. Four main factors reduced our confidence in the evidence. First, not all of the studies provided data about everything that we were interested in. Second, the results were very inconsistent across the different studies. Third, there were not enough studies to be certain about the results of our outcomes. Fourth, many studies did not clearly report how they were conducted.

How up‐to‐date is this evidence?

The evidence is up‐to‐date to February 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Antipsychotics compared with placebo for people with borderline personality disorder.

| Antipsychotics compared with placebo for people with borderline personality disorder | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with borderline personality disorder Settings: inpatient and outpatient Intervention: antipsychotics Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Antipsychotics | |||||

|

BPD symptom severity Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (5 to 12 weeks treatment duration) |

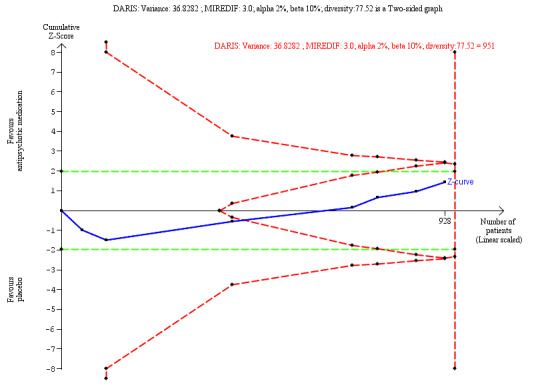

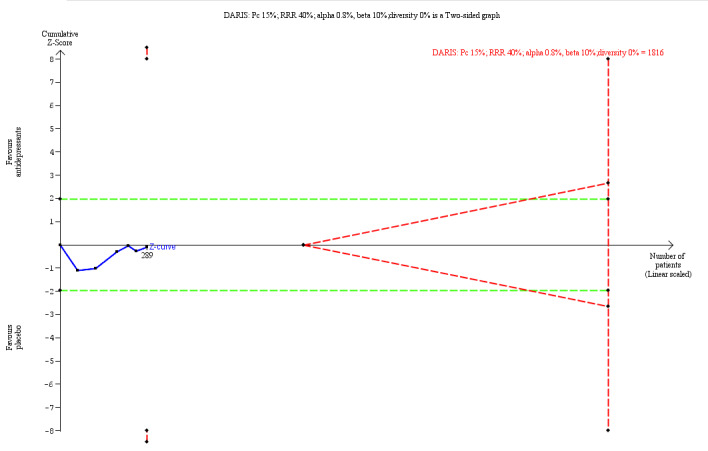

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.18 SD lower (0.45 lower to 0.08 higher, I2 = 70%) than in the placebo group | ‐ | 951 (8 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very Lowa,b | An SMD of 0.18 represents a small effect. **TSA‐adjusted CI is −3.27 to 0.86 on the Zanarini BPD scale. Z value in futility area TSA DARIS = 951 TSA in futility area |

|

Self‐harm Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (8 to 24 weeks treatment duration) |

310 per 1000 | 208 per 1000 (211 less to 127 more self‐harm incidents than in the placebo group) | RR 0.66 (95% CI 0.15 to 2.84, I2 = 67%) | 76 (2 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very Lowc,d | ‐ |

|

Suicide‐related outcomes Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (6 to 12 weeks treatment duration) |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.05 SD higher (0.18 lower to 0.29 higher, I2 = 55%) than in the placebo group | ‐ | 854 (7 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very Lowa,e | A SMD of 0.05 represents a marginal effect. RR 0.73 (95% CI 0.31 to 1.73; 2 trials, 61 participants), low‐certainty evidence |

|

Psychosocial functioning Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (5 to 12 weeks treatment duration) |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.16 SD lower (0.33 lower to 0.00 lower, I2 = 75%) than in the placebo group | ‐ | 904 (7 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very Lowa,f,g | A SMD of 0.16 represents a small effect. |

|

Interpersonal problems Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (5 to 12 weeks treatment duration) |

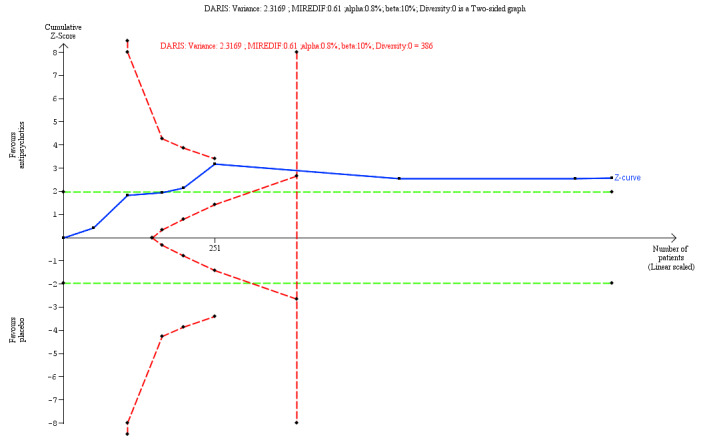

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.21 SD lower (0.34 lower to 0.08 lower, I2 = 0%) than in the placebo group | ‐ | 907 (8 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | A SMD of 0.21 represents a small effect. TSA‐adjusted CI is −0.60 to 0.08 on Zanarini BPD Scale ‐Interpersonal Problem Index TSA DARIS = 386 |

|

Attrition Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (5 weeks to 6 months treatment duration) |

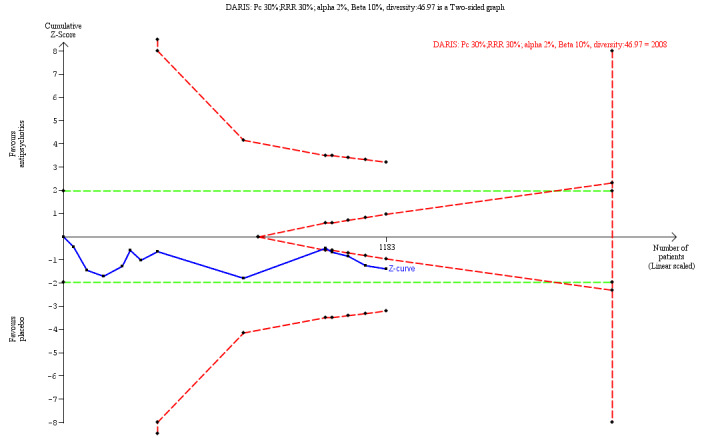

325 per 1000 | 361 per 1000 (36 less to 123 more than in the placebo group dropped out) | RR 1.11 (0.89 to 1.38; I2 = 35%) | 1216 (13 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very Lowa,h | TSA‐adjusted CI is 0.74 to 2.13 TSA DARIS = 2008 |

|

Non‐serious adverse events Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (8 to 12 weeks treatment duration) |

560 per 1000 |

599 per 1000 (56 less to 162 more than in the placebo group dropped out) |

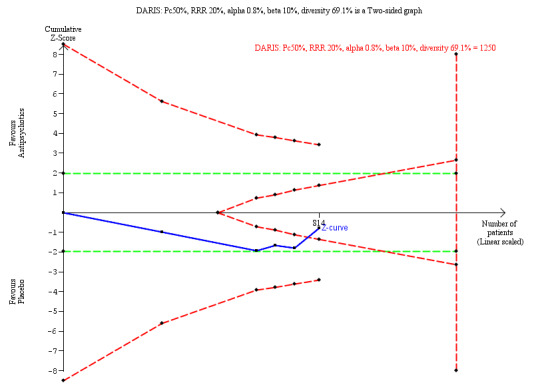

RR 1.07 (0.90 to 1.29; I2 = 57%) | 814 (5 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very Lowa,i | TSA‐adjusted CI is 0.79 to 1.47 TSA DARIS = 1250 TSA in futility area |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across trials) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). **TSA did not include cross‐over trials. CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; BPD: Borderline Personality Disorder; SD: standard deviation; SMD: Standardised mean difference TSA Trial Sequential Analysis, DARIS: Diversity‐adjusted required information size | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aWe downgraded the evidence two levels due to risk of bias of the included studies (indication of selective outcome reporting, indication of incomplete outcome data presented in the included studies) (rated by HEC and OJS (E))

bWe downgraded the evidence one level due to inconsistency (I2= 70%) (rated by HEC and OJS)

c We downgraded the evidence two levels due to imprecision (wide CI around the pooled effect estimate suggest both an appreciable effect and no effect; few participants included in the studies) (rated by HEC and OJS)

dWe downgraded the evidence one level due to inconsistency (I2 = 67%) (rated by HEC and OJS (D))

eWe downgraded the evidence one level due to inconsistency (I2 = 55%) (rated by HEC and OJS)

fWe downgraded the evidence one level due to inconsistency (I2 = 75%) (rated by HEC and OJS)

gWe downgraded the evidence one level due to imprecision (wide CI around the pooled effect estimate suggest both an appreciable effect and no effect) (rated by HEC and OJS)

h We downgraded the evidence one level due to imprecision (wide CI around the pooled effect estimate suggest both an appreciable effect and no effect; the TSA that did not reach the required information size (RIS)) (rated by HEC and OJS)

i We downgraded the evidence one level due to inconsistency (I2= 57%) (rated by HEC and OJS)

Summary of findings 2. Antidepressants compared with placebo for people with borderline personality disorder.

| Antidepressants compared with placebo for people with borderline personality disorder | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with borderline personality disorder Settings: inpatient, outpatient, partial inpatient and partial outpatient Intervention: antidepressants Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Antidepressant | |||||

|

BPD symptom severity Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (5 to 6 weeks treatment duration) |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention group was 0.27 SD lower (0.65 lower to 1.18 higher, I2= 73) than in the placebo group | ‐ | 87 (2 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | ‐ |

|

Self‐harm Assessed with: OAS‐M (Self‐injury; scale range: 0‐40 (0 = no aggression, 40 = maximum grade of aggression) Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (12 weeks treatment duration) |

The mean reduction in self‐harm was 6.55 in the control group | The mean score in the intervention group was0.45 points higher (10.55 lower to 11.45 higher) than in the placebo group | ‐ | 20 (1 trial) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | ‐ |

|

Suicide‐related outcomes Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (6 to 12 weeks treatment duration) |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.26 SD lower (1.62 lower to 1.09 higher, I2 = 80%) than in the placebo group | ‐ | 45 (2 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c,d | ‐RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.71 to 1.4; 1 trial, 49 participants). Very low‐certainty evidence |

|

Psychosocial functioning Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (5 to 12 weeks treatment duration) |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.25 SD lower (0.57 lower to 0.06 higher, I2 = 0%) than in the placebo group | ‐ | 161 (4 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,e | ‐ |

|

Interpersonal problems Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (5 weeks treatment duration) |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.07 SD lower (0.69 lower to 0.55 higher, I2 = 66%) than in the placebo group | ‐ | 119 (2 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,f | ‐ |

|

Attrition Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (5 weeks to 6 months treatment duration) |

170 per 1000 | 182 per 1000 (59 less to 129 more than in the placebo group dropped out ) | RR 1.07 (95% CI 0.65 to 1.76; I2 = 0%) | 289 (6 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc, g | TSA‐adjusted CI is 0.07 to 14.98 TSA DARIS = 1816 |

|

Non‐serious adverse events Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

no data available | no data available | no data available | no data available | no data available | no data available |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across trials) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; BPD: Borderline Personality Disorder;OAS‐M: Modified Overt Agression Scale; SD: standard deviation; TSA Trial Sequential Analysis, DARIS: Diversity‐adjusted required information size | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aWe downgraded the evidence by two levels due to imprecision (wide CI around the pooled effect estimate suggest both an appreciable effect and no effect; few patients included) (rated by HEC and OJS)

bWe downgraded the evidence one level due to inconsistency (a high I2 score of 73%) (rated by HEC and OJS)

cWe downgraded the evidence one level due to risk of bias (indication selective outcome reporting in the included study) (rated by HEC and OJS)

dWe downgraded the evidence one level due to inconsistency (a high I2 score of 80%) (rated by HEC and OJS)

eWe downgraded the evidence one level due to risk of bias (indication of incomplete outcome data) (rated by JSW and OJS) fWe downgraded the evidence one level due to inconsistency (a high I2 score of 66%) (rated by HEC and OJS) g We downgraded the evidence one level due to imprecision (wide CI around the pooled effect estimate suggest both an appreciable effect and no effect; TSA not reaching required information size (RIS)) (rated by HEC and OJS)

Summary of findings 3. Mood stabilisers compared with placebo for people with borderline personality disorder.

| Mood stabilisers compared with placebo for people with borderline personality disorder | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with borderline personality disorder Settings: inpatient, outpatient, inpatient and outpatient Intervention: mood stabilisers Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Mood stabilisers | |||||

|

BPD symptom severity Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (6 to 52 weeks treatment duration) |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.07 SD lower than in the placebo group (0.43 lower to 0.57 higher, I2 = 55%) | ‐ | 265 (4 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | A SMD of 0.07 represents a marginal effect. |

|

Self‐harm Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (52 weeks treatment duration) |

345 per 1000 |

373 per 1000 (72 less to 166 more self‐harm incidents than in the placebo group) |

RR 1.08 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.48) | 276 (1 trial) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd,e | ‐ |

|

Suicide‐related outcomes Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (6 to 10 weeks treatment duration) |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention group was 0.36 SD lower than in the placebo group (1.96 lower to 1.25 higher, I2 = 81%) | ‐ | 44 (2 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd,e,f | ‐ |

|

Psychosocial functioning Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (32 days to 6 weeks treatment duration) |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.01 SD lower than in the placebo group (‐0.28 lower to 0.26 higher, I2 = 0%) | ‐ | 214 (2 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowd,e,g | A SMD of 0.01 represents a marginal effect. RR 0.64 (95% CI 0.37 to 1.11; 1 trial, 16 participants).Very low‐certainty evidence |

|

Interpersonal problems Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (32 days to 24 weeks) |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.58 SD lower than in the placebo group (1.14 lower to 0.02 lower, I2 = 73%) | ‐ | 300 (4 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowg,h | A SMD of 0.58 represents a moderate effect. |

|

Attrition Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (32 days to 24 weeks treatment duration) |

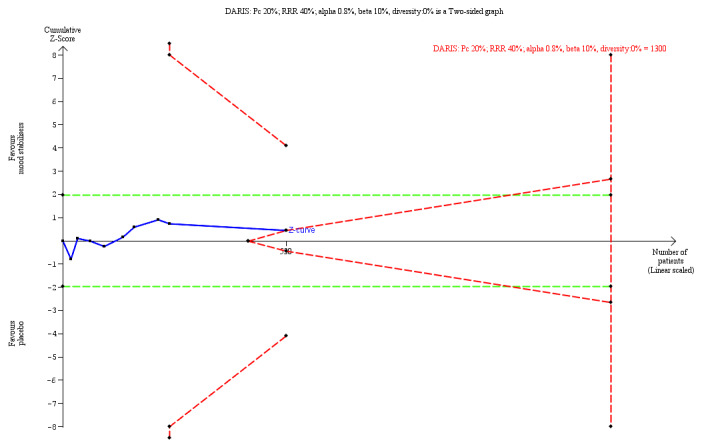

260 per 1000 | 208 per 1000 (6 less to 154 more than in the placebo group dropped out ) | RR 0.89 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.15; I2 = 0%) | 530 (9 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,i | TSA‐adjusted CI is 0.37 to 2.23 TSA DARIS = 1300 |

|

Non‐serious adverse events Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment (6 weeks treatment duration) |

670 per 1000 |

563 per 1000 (201 less to 7 more than in the placebo group dropped out ) |

RR 0.84 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.01; I2 = 0%) | 276 (1 trial) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,e | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across trials) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; BPD: Borderline Personality Disorder; NA: not applicable; OAS‐M: Modified Overt Agression Scale; CGI‐I: Clinical Global Impression scale ‐ Improvement SD: standard deviation; SMD: Standardised mean difference; TSA Trial Sequential Analysis, DARIS: Diversity adjusted required information size | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a We downgraded the evidence one level due to risk of bias in the included studies (indication of incomplete outcome data in the included studies) (rated by HEC and OJS) b We downgraded the evidence one level due to imprecision (wide CI around the pooled effect estimate suggest both an appreciable effect and no effect) (rated by HEC and OJS)

cWe downgraded the evidence one level due to inconsistency (a high I2 score of 55%) (rated by HEC and OJS)

dWe downgraded the evidence one level due to risk of bias (indication of selective outcome reporting in the included study) (rated by HEC and OJS) eWe downgraded the evidence two levels due to imprecision (wide CI around the pooled effect estimate suggest both an appreciable effect and no effects; results based on 1 study or few participants) (rated by HEC and OJS)

fWe downgraded the evidence one level due to inconsistency (a high I2 score of 81%) (rated by HEC and OJS)

gWe downgraded the evidence one level due to inconsistency (a high I2 score of 73%) (rated by HEC and OJS)

hWe downgraded the evidence one level due to risk of bias (indication of incomplete outcome data and vested interests)

iWe downgraded the evidence one level due to imprecision (wide CI around the pooled effect estimate suggest both an appreciable effect and no effects; TSA not reaching required information size (RIS)) (rated by HEC and OJS)

Background

Description of the condition

According to current diagnostic criteria, borderline personality disorder (BPD) is characterised by a pervasive pattern of instability in affect regulation, impulse control, interpersonal relationships, and self‐image (APA 2013; WHO 1993). Clinical hallmarks include emotional dysregulation, impulsive aggression, repeated self‐injury, and chronic suicidal tendencies (Bohus 2021; Fonagy 2009; Lieb 2004). BPD is being widely researched in order to better understand and treat the disorder‐specific symptoms. Its importance stems from the large amount of suffering of the persons concerned (Bohus 2021; Stiglmayr 2005; Zanarini 1998), debilitating functional impairments (Gunderson 2011a; Gunderson 2011b; Niesten 2016; Skodol 2002; Soetmann 2008b), and from the significant impact it has on mental health services (Cailhol 2015; Hörz 2010; Soetmann 2008a; Tyrer 2015; Zanarini 2004a; Zanarini 2012). The problem of deliberate self‐harm is also a particular issue within this group (Ayodeji 2015; Kongerslev 2015; Linehan 1997; Ose 2021; Rossouw 2012). In medical settings, people with BPD often present after self‐harming behaviour or in suicidal crisis and are treated in emergency settings, often involving repeated psychiatric hospitalisations (Bender 2006; Cailhol 2015). It is estimated that about 60% to 78% of people with BPD attempt suicide (Links 2009), though the rate of completed suicides is far less (Bohus 2021). Zanarini and colleagues found suicide rates of 4.5% during 16 years of follow‐up (Zanarini 2015), whereas Stone 1993 reported a suicide rate of 8.5% after 16.5 years. Study estimates of the lifetime risk of suicide among people with BPD range from 3% to 10% (Links 2009). Suicidal behaviour (e.g. behaviour that could cause death such as medication overdosing and purposely crashing in traffic) is reported to occur in up to 84% of people with BPD (Goodman 2012; Soloff 2002). Common risk factors associated with completed suicide are low socioeconomic status, poor psychosocial adjustment, family history of suicide, previous psychiatric hospitalisation, and absence of any outpatient treatment before the attempt (Soloff 2012).

The definition of BPD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) Fifth Edition (DSM‐5; APA 2013), Fourth Edition Text Revision (DMS‐IV‐TR; APA 2000) and Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV; APA 1994) comprises nine criteria that cover the features mentioned above. At least five criteria should be met for a definite categorical BPD diagnosis to be made, and four criteria for probable diagnosis (see Appendix 1). In the alternative diagnostic classification system of the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Classification of Diseases, which is currently in its tenth edition (ICD‐10; WHO 1993), the relating condition is referred to as "Emotionally unstable personality disorder (F60.3)", of which there is an impulsive type (F60.30) and a borderline type (F60.31: see Appendix 2). The latter essentially overlaps with the DSM‐IV definition. There are 10 possible criteria in the ICD‐10 diagnosis for BPD that very closely resembles the DSM‐IV/5 criteria (Ottosson 2002), with the exception of one criterion which is not included in the DSM ("4. Difficulty in maintaining any course of action that offers no immediate reward"; WHO 1993). Out of the 10 ICD‐10 criteria, at least five must be met, one of which must be "a marked tendency to quarrelsome behaviour and to conflicts with others, especially when impulsive acts are thwarted or criticised". Currently, the successive version of the ICD (ICD‐11) is being finalised (WHO 2021). It will abolish any personality disorder categories for the sake of a general description of personality disorder in terms of severity (mild, moderate, severe) and five personality trait domains (negative affectivity, dissociality, anankastia, detachment, and disinhibition). In addition, it will include a "borderline specifier" (6D11.5), which can additionally be diagnosed and which will essentially consist of all nine BPD criteria defined in DSM‐5 (Mulder 2021; WHO 2021; see Appendix 2).

Overall, the prevalence of BPD in the general population is estimated to be about 1.5% (Torgersen 2012), with findings of single epidemiological studies ranging between 0.6% (Coid 2006) and 2.7% (Trull 2010). In clinical populations, BPD occurs frequently (Munk‐Jørgensen 2010), with studies reporting a prevalence ranging from 9.3% to 46.3% and a mean point prevalence across studies of 28.5% (Torgersen 2012). Though BPD is predominantly diagnosed in women (75%; APA 2000, APA 2013, Widiger 1993), it is estimated to be equally prevalent in men by representative community studies (Coid 2006; Grant 2008; Lenzenweger 2007; Ten Have 2016; Tomko 2014; Torgersen 2001; Torgersen 2012). Reasons for this obvious gender bias are discussed as: bias in the diagnostic criteria, bias in the application of the diagnostic criteria by clinicians, bias in diagnostic thresholds across disorders more prevalent in one gender or another, biased population sampling, bias in the assessment instruments, and bias in the diagnostic construct itself (Widiger 1998).

BPD commonly co‐occurs with mood disorders, substance misuse, eating disorders, post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and is also associated with other personality disorders (Coid 2006; Lenzenweger 2007; Stepp 2012; Storebø 2014; Tomko 2014).

Although the short‐ to medium‐term outcome of BPD is poor, symptomatic remission rates of about 85% to 88% have been reported within 10 years (Gunderson 2011b; Zanarini 2007). Another, smaller prospective longitudinal study reported a diagnostic remission rate of 55% after 10 years (Alvarez‐Tomas 2017). However, remission only means that diagnostic criteria are no longer fulfilled; it does not indicate the absence of any symptoms. Indeed, whereas acute symptoms — such as self‐mutilation, help‐seeking suicide threats or attempts and impulsivity — in most cases decrease with time, affective symptoms reflecting areas of chronic dysphoria, such as chronic feelings of emptiness, intense anger or a profound sense abandonment, largely remain (Zanarini 2007). Therefore, the majority of people with BPD still have significant levels of symptoms and experience severe and persistent impairment in social functioning, high unemployment rates, physical ill‐health, and a substantially reduced life expectancy (Bohus 2021; Kongerslev 2015; Ng 2016; Schneider 2019). 'Good recovery', defined as being in remission of BPD for a minimum of two years, good social functioning in terms of having at least one emotionally sustaining relationship, and good vocational functioning (working or attending school consistently on a full‐time basis) was only achieved by 50% of individuals with BPD after 10 years of prospective follow‐up, and 59% after 20 years of follow‐up (Zanarini 2012; Zanarini 2018). Younger age seems to be associated with a higher probability of diagnostic remission in the long term (Alvarez‐Tomas 2019), indicating the importance of early diagnosis and intervention (Chanen 2017).

BPD onsets happen in young people, i.e. between puberty and emerging adulthood (Chanen 2013). Today, the diagnosis is regarded reliable and valid also in adolescents, as a similarity in prevalence, phenomenology, and stability has been observed, as well as a markedly different course and outcome as compared to other disorders (Chanen 2017) or ordinary problems. For a long time, clinicians were reluctant to diagnose BPD (not only, but specifically) in adolescents due to the assumed stigma, and wanting to avoid giving young people a diagnosis believed to be an 'uncurable' disorder. However, due to emerging evidence, there is now consensus among the scientific community that the disorder should be detected and diagnosed as early as possible, given that helpful treatments do exist, and that later interventions tend to reinforce functional impairment, disability and therapeutic nihilism (Chanen 2013; Chanen 2017).

Risk factors for a poorer long‐term outcome are comorbid substance use disorders, PTSD, and anxiety cluster disorders (Zanarini 2005; Zanarini 2007), a family history of psychiatric disorder (especially mood disorders and substance use disorders), as well as individual factors such as older age, longer treatment history, pathological childhood experiences, and adult psychosocial functioning (Bohus 2021; Chanen 2012; Kongerslev 2015; Zanarini 2007).

People with BPD often have difficulties achieving and maintaining vocational and social functioning over time (Hastrup 2019b; Zanarini 2010). Furthermore, treatment‐seeking people with personality disorders, such as BPD, pose a high economic burden on society due to a frequent and often long‐term utilisation of both psychiatric and emergency services as well as loss of occupational function and income (Hastrup 2019a; Van Asselt 2007). Effective treatments could potentially decrease the high costs associated with the condition (Soetmann 2008a).

In summary, BPD is a condition that has been extensively studied and has a major impact on health services (Bode 2017; Jacobi 2021; Meuldijk 2017). The recovery from symptoms or functional impairment (or both) was previously considered likely for only a low percentage of people diagnosed with BPD. However, the long‐term course is better than what was previously assumed, due to more favourable symptomatic recoveries (Zanarini 2012). Nonetheless, people with BPD continue to have considerable interpersonal and functional problems, and sustainable recovery appears difficult to attain (Biskin 2015; Kongerslev 2015; Rossouw 2012).

Description of the intervention

To date, all major treatment guidelines consider psychotherapy as the treatment of choice for BPD and assign medications an adjunctive role (e.g. APA 2001; Bateman 2015; Cristea 2017; DGPPN 2009; Herpertz 2007; NHMRC 2013; NICE 2009; Simonsen 2019; Storebø 2020). However, the large majority of people with BPD are prescribed psychotropic medications during the course of their illness. This may be the case in times of crisis, when people with BPD present to mental health services with raised suicidality or parasuicidality, impulsivity‐associated outbreaks, psychotic‐like exacerbations, severe dissociations or aggravations of comorbid conditions (e.g. mood disorders), and so medications are used to achieve short‐term stabilisation (NHMRC 2013; NICE 2009; Riffer 2019). Such crisis interventions will not be considered in this review, but are subject to another Cochrane Review, which is currently being updated (Borschmann 2012).

In contrast to short‐term crisis medication, up to 84.1% of people with BPD who are engaged in treatment have been reported to use standing (i.e. long‐term) psychotropic medications (Bender 2001; Zanarini 2015), and as many as 92% have been reported to use any psychotropic medication for a non‐specified period of time (Paton 2015). Indeed, it is a common finding that people with BPD are more likely to use psychotropic medications than people with other psychiatric conditions such as major depressive disorder (Bender 2001; Bender 2006), mood or anxiety disorders in general (Ansell 2007), or other personality disorders (Zanarini 2004a).

Studies across different countries show that antidepressants are the class of medication most often prescribed to people with BPD (Bender 2001; Knappich 2014; Makela 2006; Paton 2015; Sansone 2003; Zanarini 2015). Zanarini and colleagues found that 79.7% of people with BPD were taking antidepressant medication, followed by anxiolytics (46.6%), neuroleptics (38.6%), and mood stabilisers (35.9%) (Zanarini 2015). They also found that about 71% of people with BPD were using medications at six‐year follow‐up (Zanarini 2004a; Zanarini 2004b), and that they were still more likely to be using antidepressants, mood stabilisers, antipsychotics or anxiolytics than Axis‐II comparison participants at 16‐year follow‐up (Zanarini 2015). Additionally, polypharmacy is common, with reports of people with BPD taking, on average, 2.02 psychotropic medications at a time (Ansell 2007), and up to 28.6% taking four or more medications (Zanarini 2004a; Zanarini 2004b).

There is no stringent or binding classification of psychotropic medications. In routine clinical care, the most commonly used classification is likely to be that which builds on the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification (WHO Collaborating Center for Drug Statistics.), where medications are grouped primarily by indication, such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, antidementive drugs, etc. This classification has been criticised for various reasons, including: not considering the fact that many psychotropic medications are not only used for one, but several indications, which may confuse consumers and lower adherence; the grouping of too heterogeneous kinds of medications into the same group; and having too close connection to marketing claims of the pharmaceutical industry (names may be mistaken to imply that the drugs definitely are effective as regards the respective outcomes; Brühl 2017). In order to target these shortcomings, the Neuroscience‐based Nomenclature has been developed (Brühl 2017; NbN3 2021), with the aim of moving from a disease‐based classification system to one that is pharmacologically driven, focusing on modes of actions rather than symptoms. This review use traditional categories, such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilisers, antidementive medications, etc., as these might be most familiar to consumers and clinicians in the field as well as healthcare professionals (who might not have a background in psychiatry or psychology). A translation of these terms into the Neuroscience‐based Nomenclature (NBN) (NbN3 2021) can be found in Appendix 3.

In summary, prescription rates of psychotropic medications are high among people with BPD and these medications are often administered for sustained periods of time, even though medication is only advised as an adjunctive to psychotherapy (Bateman 2015; Bohus 2021; NHMRC 2013; NICE 2018). Different classes of medication are used, with antidepressants being the most frequent, but there is no standard medication treatment. Currently, any medication use in BPD is off‐label (if not used to target associated psychopathology, such as depression or anxiety, for which there is evidence for use), but up to 82% of people with BPD without comorbid conditions still receive medications to directly target BPD symptoms (Paton 2015).

How the intervention might work

The most important pharmacological domains and modes of action of each included medication are presented in Appendix 3. Essentially, the psychotropic medications included in this review are thought to work ‐ at least partially ‐ in ways described below:

The serotonergic system has been associated with mood (depressive mood, anxiety), impulsiveness and aggressiveness (Herpertz 2007). Antidepressants effectuate a higher concentration and longer availability of serotonin in the synaptic cleft by preventing its reuptake (e.g. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)), or degradation (e.g. monoamin oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)). As an inverse relationship between serotonin levels in the brain and low mood, as well as increased impulsive behaviour, has been demonstrated, substances increasing serotonin availability might improve mood and lower impulsive behaviour.

The monoamines norepinephrine and dopamine have also been implicated in emotion and reward. Norepinephrine is related to stress as it helps the brain and body to prepare for immediate action ('fight‐flight‐response'). It increases arousal, alertness and attention, but is also related to restlessness and anxiety. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter which not only plays a major role in schizophrenia but is also related to executive functions and arousal, along with reward and motivation. Substances which increase the level of these monoamines might therefore have an impact on perception and behavioural choices.

GABA (gamma‐aminobutyric acid) is an inhibitory neurotransmitter that reduces neural excitability in the central nervous system. Heightened GABA levels have been shown to be associated with relaxing, anti‐anxiety, and anti‐convulsive effects.

Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system which is involved in e.g. motor‐executive functions, as well as learning and memory.

Opioid peptides bind as agonists to opioid receptors and act as endogenous analgesics. They have modulating effects on mood and have a role in the aetiology and maintenance of substance use disorders. Opioid antagonists are used in the treatment of opioid and alcohol use disorders, and opioid substances in the treatment of substance withdrawal.

Psychotropic medications may target one or several of these pharmacology domains and comprise one or more modes of action. However, it is unlikely that direct and immediate effects at the synapses can explain changes in mood, anxiety etc., since such changes only occur after weeks of treatment. Much more likely modes of actions are secondary effects on plastic brain adaptation processes, which are not well understood yet, especially in BPD.

Why it is important to do this review

BPD poses a major burden, both personal (Soetmann 2008b) and financial (Soetmann 2008a) on those directly affected, their relatives, as well as for society at large. Despite the frequent use of pharmacological interventions in clinical practice, and in research over the last three decades, any medication used in the treatment of BPD is off‐label. Given the absence of reliable evidence being supportive of medication use, prescription is often undertaken based upon known effects on symptom clusters in other disorders, out of habit, ignorance, passed‐on clinical rules of thumb or desperation (Aguglia 2019; Paris 2015; Pascual 2021; Riffer 2019; Zanarini 2004a). Clinicians and consumers, however, must be able to make informed decisions on the basis of up‐to‐date evidence (Ingenhoven 2015; Paris 2015; Silk 2015), allowing them to weigh up potential benefits and harms. This Cochrane Review aims to systematically identify, investigate, and present the current state of evidence on the topic of medications in BPD, and make suggestions about the directions for future trials.

This review supersedes a previous Cochrane Review on pharmacological interventions for BPD (Stoffers 2010). In addition to updating the former Cochrane Review, our study also seeks to address some of the methodological limitations of the preceding two reviews (Binks 2006; Stoffers 2010) by using updated methods, and including a more comprehensive search strategy. In order to do this transparently, we developed and published a new protocol prior to conducting this review (Stoffers‐Winterling 2018). The Stoffers 2010 review came to the conclusion that the evidence available at that time indicated beneficial effects for some medications (i.e. second‐generation antipsychotics, mood stabilisers and omega‐3 fatty acids), but that the overall quality of the evidence was not robust enough to draw any reliable conclusions. In the proceeding 11 years, research has continued in the field, and new findings may change conclusions of the previous review. Therefore, an update of this review seems both appropriate and timely (Garner 2016).

Objectives

To assess the effects of pharmacological treatment for people with BPD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

Individuals of all ages, in any setting, with a formal diagnosis of BPD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) Third Edition (DSM‐III; APA 1980), Third Edition Revised (DSM‐III R; APA 1987), Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV; APA 1994), Fourth Edition Text Revision (DSM‐IV‐TR; APA 2000), and Fifth Edition (DSM‐5; APA 2013)), with or without comorbid conditions.

We required at least 70% of trial participants to have a formal diagnosis of BPD. We also included trials involving subsamples of people with BPD if data on these were available separately. We did not include trials that focused on people with mental impairment, organic brain disorder, dementia, or other severe neurologic diseases.

Types of interventions

Any medication or defined combination of medications administered at any dosage, prescribed to treat the disorder or its symptoms, compared to a placebo or active comparator medication(s) was eligible. We included trials that paired medications with an adjunctive intervention (e.g. psychological therapies), providing this was given to participants in both the intervention and control arm, and the pharmacological intervention was unique to the treatment group.

Medication should have been prescribed continuously for a minimum duration of two weeks for the trial to be eligible for our review. In addition, we judged the actual duration required for inclusion in light of the specific mode of action of the medical agent. Medication should have been used to treat the disorder or symptoms thereof.

Types of outcome measures

Outcomes could either be self‐rated or observer‐rated by clinicians. We included only adequately validated measures (plus spontaneous reporting of adverse events).

Primary outcomes

BPD severity, as assessed by, for example, the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (Zan‐BPD; Zanarini 2003), the Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index (BPDSI‐IV; Arntz 2003), or the Clinical Global Impression Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder Patients (CGI‐BPD; Perez 2007).

Self‐harm, in terms of the proportion of participants with self‐harming behaviour, or as assessed by, for example, the Deliberate Self‐harm Inventory (DSHI; Gratz 2001) or the Self‐harm Behavior Questionnaire (SHBQ; Guttierez 2001).

Suicide‐related outcomes, as assessed by, for example, the Suicidal Behaviours Questionnaire (SBQ; Osman 2001) or the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI; Beck 1979) or in terms of the proportion of people with BPD with suicidal acts.

Functioning, as assessed by, for example, the Global Assessment Scale (GAS; Endicott 1976), the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF; APA 1987) or the Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ; Tyrer 2005).

Secondary outcomes

Anger, as assessed by, for example, the 'Hostility' subscale of the Symptom Checklist‐90‐Revised (SCL‐90‐R; Derogatis 1994), or the State‐Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI; Spielberger 1988).

Affective instability, as assessed by, for example, the relevant item or subscale on the Zan‐BPD (Zanarini 2003), CGI‐BPD (Perez 2007) or BPDSI‐IV (Arntz 2003).

Chronic feelings of emptiness, as assessed by, for example, the relevant item or subscale on the Zan‐BPD (Zanarini 2003), CGI‐BPD (Perez 2007) or BPDSI‐IV (Arntz 2003).

Impulsivity, as assessed by, for example, the Barrett Impulsiveness Scale (BIS; Barrett 1995), or the Anger, Irritability and Assault Questionnaire (AIAQ; Coccaro 1991).

Interpersonal problems, as assessed by, for example, the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP; Horowitz 1988), or the relevant item or subscale of the Zan‐BPD (Zanarini 2003), CGI‐BPD (Perez 2007), BPDSI‐IV (Arntz 2003), or SCL‐90‐R (Derogatis 1994).

Abandonment, as assessed by, for example, the relevant item or subscale on the Zan‐BPD (Zanarini 2003), CGI‐BPD (Perez 2007) or BPDSI‐IV (Arntz 2003).

Identity disturbance, as assessed by, for example, the relevant item or subscale on the Zan‐BPD (Zanarini 2003), CGI‐BPD (Perez 2007) or BPDSI‐IV (Arntz 2003).

Dissociation and psychotic‐like symptoms, as assessed by, for example, the Dissociative Experience Scale (DES; Bernstein 1986), or the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Overall 1962).

Depression, as assessed by, for example, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck 1961), or the Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Montgomery 1979).

Attrition, in terms of participants lost after randomisation in each group.

Adverse effects, as measured by use of standardised psychometric rating scales such as the Systematic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Events (SAFTEE; Levine 1986), laboratory values or spontaneous reporting.

Search methods for identification of studies

This current review is part of a series of reviews on interventions for BPD (Stoffers‐Winterling 2018; Storebø 2018; Storebø 2020; Stoffers 2010). Therefore, the search strategy is very comprehensive and covers all psychotherapeutic or pharmacological treatment (or both) of BPD. The search has been run four times in all databases over the years. A full search in all databases was carried out in 2017 and then additional top‐up searches were used to update search hits until the most recent search on 21 February 2022. Trial registries were handsearched several times during the work with this update, most recently on individual dates as close to the submission date of this manuscript as possible.

Electronic searches

We searched the electronic databases and trials registers listed below to identify relevant trials.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2022, Issue 2), in the Cochrane Library, which includes the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Specialised Register (searched 21 February 2022).

MEDLINE Ovid (1948 to 21 February 2022).

Embase Ovid (1974 to 21 February 2022).

CINAHL EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1980 to 21 February 2022).

PsycINFO Ovid (1806 to 21 February 2022).

ERIC EBSCOhost (Education Resources Information Center; 1966 to 21 February 2022).

BIOSIS Previews Web of Science Clarivate Analytics (1969 to 29 June 2022).

Web of Science Clarivate Analytics (Science Citation Index Expanded and Social Sciences Citation Index 2002 to 21 February 2022).

Sociological Abstracts ProQuest (1952 to 21 February 2022).

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database (lilacs.bvsalud.org/en; searched 21 February 2022)).

Library Hub Discover (previously Copac National, Academic and Specialist Library Catalogue; copac.jisc.ac.uk, searched 21 February 2022).

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses A&I (1973 to 21 February 2022).

OpenGrey; searched 28 December 2020 (OpenGrey was shut down before top‐up searches).

DART Europe E‐Theses Portal (www.dart-europe.eu/basic-search.php, searched 27 June 2022).

Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD; ndltd.org, searched 27 June 2022).

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR; anzctr.org.au/TrialSearch.aspx, searched 25 February 2022).

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/, searched 21 February 2022).

EU Clinical Trials Register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/search, searched 25 February 2022).

ISRCTN Registry (www.isrctn.com/, searched 23 June 2022).

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; trialsearch.who.int/, searched 22 June 2022).

The search strategies for each source are available in Appendix 4. We did not limit our searches by language, year of publication, or type of publication. We sought translation of the relevant sections of non‐English language articles.

Searching other resources

On 10 and 11 March 2022, we searched for unpublished data on the websites of the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA; www.fda.gov) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA; www.ema.europa.eu/ema) (see Appendix 4). We also handsearched relevant journals: the Journal of Personality Disorders; the American Journal of Psychiatry; JAMA Psychiatry; British Journal of Psychiatry; ACTA Psychiatrica Scandinavica; Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; Personality Disorders: Theory, Research and Treatment; and the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. Additionally, we contacted researchers working in the field by email, to ask for unpublished data,and traced cross‐references from relevant literature.

Data collection and analysis

We conducted this review according to guidelines set out in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022), and performed the analyses using the latest version of Review Manager Web (RevMan Web), Cochrane's statistical software (RevMan Web 2020).

We were not able to use all of our methods as planned (Stoffers‐Winterling 2018). We report the unused methods in Table 4.

1. Key demographic characteristics of the included studies.

Selection of studies

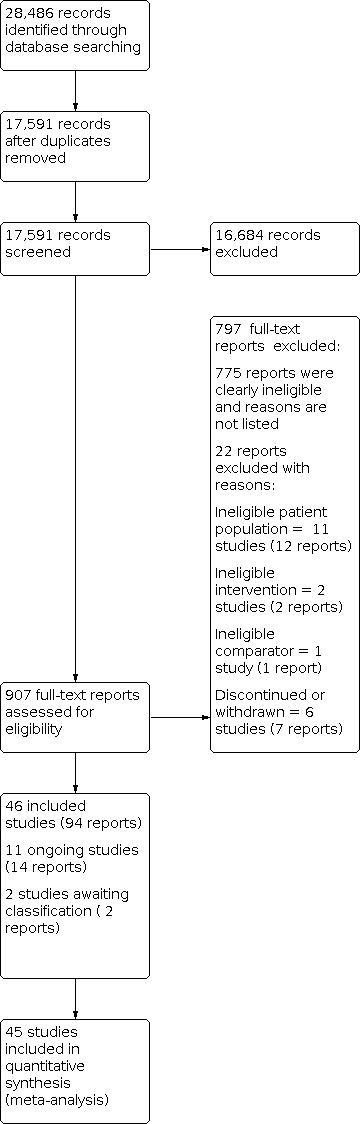

Thirteen reviewers (JMSW, OJS, AT, EF, BAV, MLK, MTK, CPS, JTM, JPR, HEC, SSN, JPS) worked in pairs and independently screened titles and abstracts of all records retrieved by the searches; we resolved uncertainty or disagreement by consensus. For records that could be eligible RCTs, we obtained the full‐text reports and assessed them for eligibility based on the inclusion criteria (Criteria for considering studies for this review). Review authors discussed disagreements and, if they could not reach an agreement, they consulted a third review author (ES or KL). We listed potentially relevant RCTs that did not fulfil the inclusion criteria with reasons for exclusion in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables. We used Covidence software to keep track of appraised trials and decisions. To ensure transparency of study selection, we provided a flow chart in accordance with the PRISMA statement (Moher 1999), to show how many records had been excluded and for what reason (Figure 1).

1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection

Data extraction and management

We developed data extraction forms to facilitate standardisation of data extraction. All review authors extracted data. Review authors worked in pairs and completed the data collection form independently to ensure accuracy. We resolved disagreements by discussion or used an arbiter (ES) if required. JMSW, JRP, and OJS entered the data into RevMan 5 (RevMan Web 2020). In those cases where there were not enough data or data were unclear in the published trial reports, we contacted the trial authors, requesting them to supply the missing information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2017), all review authors assessed the risk of bias in each included study across the following domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias and other potential sources of bias. We included vested interest in this last domain. Andreas Lundh and colleagues have illustrated the many subtle mechanisms through which sponsorship and conflict of interest may influence intervention effects on outcomes. For more information, please see editorials by Bero 2013 and Sterne 2013, and the commentary by Gøtzsche 2015.

For each included trial, data extractors independently evaluated each risk of bias domain as being at low, unclear (uncertain) or high risk of bias, resolving disagreements by discussion. We categorised trials that had a low risk of bias in all domains as being at low risk of bias overall, and we considered trials with one or more unclear or high risk of bias domains as trials at high risk of bias overall. Given the risk of overestimation of beneficial intervention effects and underestimation of harmful intervention effects in RCTs with unclear or inadequate methodological quality (Kjaergard 2001; Lundh 2017; Moher 1998; Savović 2012a; Savović 2012b; Schulz 1995; Wood 2008), we assessed the influence of risk of bias on our results (see Sensitivity analysis).

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

We summarised dichotomous data as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs. The RR is the ratio of the risk of an event in the two groups. We decided to use the RR as it may be easier to interpret than odds ratios (ORs).

Continuous data

For continuous data, we compared the mean score between the two groups to give a mean difference (MD) and presented this with 95% CIs. We used the overall MD, where possible, to compare the outcome measures from trials. We estimated the standardised MD (SMD) where different outcome measures were used to measure the same construct in the trials. We calculated SMDs using end‐scores at post‐treatment results. Where the direction of a scale was opposite to most of the other scales, we multiplied the corresponding mean values by −1 to ensure adjusted values. If the trials did not report means and standard deviations but reported other values like t‐tests and P values, we tried to transform these into standard deviations.

Our first choice was to calculate effect sizes on the basis of intention‐to‐treat (ITT) data. If means and standard deviations from an ITT analysis and missing values that were replaced were available, we used these data. In other cases, we conducted the analysis using only the available data.

We performed all calculations using the latest release of RevMan 5 software (RevMan Web 2020).

To identify the minimum relevant clinical difference (MIREDIF), we transformed the SMD to MD, using the scale with the best validity and reliability for the given outcome. For the analyses of the primary outcome, BPD symptom severity, in the comparison of psychotherapy versus treatment‐as‐usual (TAU), we transformed SMDs into MDs on the following scale, to assess whether results exceeded the MIREDIF: ZAN‐BPD Scale, We identified a MIREDIF of −3.0 points on the ZAN‐BPD, ranging from 0 to 36 points, based on a trial by Zanarini 2007. We used a MIREDIF of 0.61 in the interpersonal problems outcome, which corresponds to ½ SD based on a trial by Schulz 2007. For attrition, we used a relative risk reduction of 40%, and for non‐serious adverse events, we used a relative risk reduction of 20%.

Unit of analysis issues

Repeated observations

We calculated study estimates on the basis of post‐treatment group results. We did not use interim observations.

Cross‐over trials

We included data from four randomised cross‐over trials (Cowdry 1988; Schmahl 2012a; Schmahl 2012b; Ziegenhorn 2009). We were not able to obtain first‐period data from these cross‐over trials (by writing to the study authors) and therefore used end of period data (Curtin 2002; Elbourne 2002) because the data were unavailable. Cross‐over trials are more prone to bias from carryover effects, period effects and unit of analysis errors, but it is still possible to use the end of period data when first‐period data are not available (Curtin 2002; Elbourne 2002). This approach might however introduce a risk of a unit of analyses error, the confidence intervals will probably be too wide, and also the trial will receive too little weight. There is also a possibility of overlooking important heterogeneity. The Cochrane Handbook states, however, that this approach is conservative as the studies are under‐weighted instead of over‐weighted (Higgins 2019). Some argue that the unit of analyses errors introduced by doing this might be regarded as less serious than other types of unit of analysis error. The trial by Cowdry (Cowdry 1988) was the only one pooled with parallel‐group trials. Cowdry and colleagues reported a washout period of one week before cross‐over. When excluding the Cowdry study from the parallel‐group trials, we found no differences in the result of the analyses. The other cross‐over trials (Schmahl 2012a; Schmahl 2012b; Ziegenhorn 2009) were reported separately in the analyses.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

If a trial compared more than two intervention groups, we included all pairwise comparisons as long as they were not subject to the same meta‐analysis. If a trial included two arms at different doses of a certain medication that were tested against placebo, we combined the experimental groups into a single group, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, making a single, pairwise comparison (Higgins 2022). We hereby avoided including the same group of participants twice in the same meta‐analysis.

Adjustment for multiplicity

Multiplicity reflects the concern that performing multiple comparisons increases the risk of falsely rejecting the null hypothesis. Multiplicity, therefore, may affect the results found within a systematic review and, as a result, needs to be adjusted for. We adjusted the P values and CIs of the primary outcomes (BPD severity) and secondary outcomes (interpersonal problems, non‐serious adverse events and attrition) for multiplicity using the method described by Jakobsen 2014. We have made a conservative estimation of the anticipated intervention effect to control the risk of type 1 error (Jakobsen 2014). We have four primary outcomes, and therefore we considered a P value of 0.02 or less as the threshold for evidence of a difference for the primary outcomes. We have 11 secondary outcomes, and therefore we considered a P value of 0.008 or less as the threshold for evidence of a difference for the secondary outcomes (Jakobsen 2014).

Dealing with missing data

We tried to obtain any missing data, including incomplete outcome data, by contacting trial authors. We reported this information in the risk of bias tables.

We evaluated the methods used to handle the missing data in the publications and to what extent it was likely that the missing data influenced the results of outcomes of interest. For preference, we calculated effect sizes on the basis of ITT data. If only available data were reported, we calculated effect sizes on this basis. Where dichotomous data were not presented on the basis of ITT data, we added the number of participants lost in each group to the participants with unfavourable results, acting on the assumption that most people with BPD did not get lost at random. For continuous outcomes, we discussed each trial’s methodology for dealing with missing continuous data (e.g. last‐observation‐carried‐forward or modified ITT approach). We used per protocol analysis, as available from the trial reports (that is, results were based on the number of participants at follow‐up).

If data were not reported in an immediately usable way, we consulted a statistician.

We assessed results derived from statistically processed data in sensitivity analyses (see Sensitivity analysis).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed trials for clinical homogeneity with respect to type of pharmacological interventions, setting and control groups. We took into account the number of trials and trial characteristics, such as duration, dose and participants, to judge if heterogeneity was more probable due to clinical (i.e. explainable factors) or unknown factors. In case of substantial heterogeneity, we divided analyses into subgroups according to trial characteristics, such as trial size, duration, dose or participants, and discussed the most apparent sources of heterogeneity. We evaluated methodological heterogeneity by comparing the design of trials (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

We investigated statistical heterogeneity within a certain comparison by visual inspection of the graphs and the I² statistic (Higgins 2003). We judged I² values between 0% and 40% to indicate little heterogeneity, between 30% and 60% to indicate moderate heterogeneity, between 50% and 90% to indicate substantial heterogeneity, and between 75% and 100% to indicate considerable heterogeneity (Deeks 2021). We also assessed statistical heterogeneity by the Chi² test (P < 0.10) and tau² ‒ an estimate of between‐trial variability.

Assessment of reporting biases

We produced funnel plots for comparisons with sufficient primary studies i.e. 10 or more trials and we performed Egger's statistical test for small‐trial effects (Egger 1997). We did not use a visual inspection of the funnel plot if there were fewer than 10 trials in the meta‐analysis, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Sterne 2017).

Data synthesis

We performed statistical analyses according to recommendations in the latest version of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2021). In carrying out the meta‐analysis, we used the inverse‐variance method for continuous data, in order to give more weight to more precise estimates from trials with less variance (mostly larger trials). For dichotomous data we used the Mantel‐Haenszel analysis method. We used the random‐effects model for meta‐analysis when there were two or more trials, since we expected some degree of clinical heterogeneity to be present in most cases, though not so substantial as to prevent pooling in principle. Where only one trial was included in an analysis, we used the fixed‐effect model, and where different models led to different results, we reported the results of both models (Sensitivity analysis). For trials with a high level of statistical heterogeneity, and where the amount of clinical heterogeneity made it inappropriate to use these trials in meta‐analyses, we provided a narrative description of the trial results. If we considered data pooling to be feasible, we pooled the primary trials effects and calculated their 95% CIs. If a trial provided more than one measure for the same outcome construct (e.g. several questionnaires for the assessment of depression), we selected the one used most often in the whole pool of included trials for effect size calculation, in order to minimise heterogeneity of outcomes in form and content. If a trial reported data of two assessment instruments that were equally frequently used, two review authors discussed the issue and chose the one which was, in its content, most appropriate for assessing people with BPD. We preferred observer‐rated measures as the primary analysis measure.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analyses to investigate the subgroups mentioned below.

Types of medication (comparing pharmacological classes as well as active medications)

Setting (outpatient compared to inpatient)

We attempted to undergo subgroup analyses for all primary outcomes; however, data were not available for all subgroups and so we investigated subgroups for the primary outcomes of BPD symptom severity, psychosocial functioning, suicide‐related outcome, and the secondary outcome anger (as this was the only outcome where it was possible to perform subgroup analyses).

We added the following subgroup analyses post hoc.

Funding (funded or partially funded by pharmaceutical industry compared to no funding received compared to funded by universities or research foundations)

Psychosocial functioning at baseline as measured by GAS, GAF or SFQ15 (comparing groups of participants with low, moderate and high impairment)

Trial size (trial size ≤ 50 compared to trial size ≤ 100 compared to trial size ≥ 100)

Type of screening (referrals compared to advertisements)

Heterogeneity‐adjusted required information size and Trial Sequential Analysis

Sequential methods like Trial Sequential Analysis (TSA) are not in general recommended to be used in Cochrane reviews. They can be used as a secondary analyses, to give an additional interpretation of the data from a specific perspective. We have used the TSA in this review as a secondary analysis testing the imprecision of some of the most important outcomes (Thomas 2021). We only performed a TSA for BPD symptom severity, interpersonal problems, non‐serious adverse events and attrition as these were the outcomes in the SoF tables where we needed to test our GRADE assessment of imprecision.

TSA is a methodology that combines a required information size (RIS) calculation for a meta‐analysis with the threshold for statistical significance (Brok 2008; Brok 2009; Thorlund 2009; Wetterslev 2008). TSA is a tool for quantifying the statistical reliability of the data in cumulative meta‐analysis, adjusting P values for sparse data and for repetitive testing on accumulating data (Brok 2008; Brok 2009; Thorlund 2009; Wetterslev 2008).

Comparable to the a priori sample size estimation in a single randomised trial, a meta‐analysis should include a RIS calculation at least as large as the sample size of an adequately powered single trial to reduce the risk of random error. TSA calculates the RIS in a meta‐analysis and provides an alpha‐spending boundary to adjust the significance level for sparse data and repetitive testing on accumulating data (CTU 2011; Wetterslev 2008), and consequently the risk of random error can be assessed. Multiple analysis of accumulating data when new trials emerge leads to repeated significant testing and hence introduces multiplicity, thus use of a conventional P value is prone to exacerbate the risk of random error (Berkey 1996; Lau 1995). Meta‐analyses not reaching the RIS are analysed with trial sequential alpha‐spending monitoring boundaries analogous to interim monitoring boundaries in a single trial (Wetterslev 2008). This approach will be crucial in future updates of the review.

If a TSA does not reveal significant findings (no crossing of the alpha‐spending boundary and no crossing of the conventional boundary of P = 0.05) before the RIS has been reached, then the conclusion should either be that more trials are needed to reject or accept an intervention effect that was used for calculation of the required sample size or — in case the cumulated Z‐curve enters the futility area — the anticipated effect can be rejected.

We used a minimally relevant clinical difference (MIREDIF) from trials defining this or, where we could not find this, we used an assumption that the minimal relevant clinical intervention effect was approximately ½ SD on the used scale, which can be used as a MIREDIF (Norman 2003).

We calculated the diversity‐adjusted required information size (DARIS; that is, the number of participants required to detect or reject a specific intervention effect in a meta‐analysis), and performed a TSA for the primary outcome, BPD symptom severity, at the end of treatment for the main comparison versus placebo, based on the following a priori assumptions:

the SD of the primary outcome;

an anticipated MIREDIF defined in a trial reporting on this or we used a ½ SD on the used scale;

a maximum type I error of 2.0% (due to four primary outcomes; Jakobsen 2014);

a maximum type II error of 10% (minimum 90% power; Castellini 2018); and

the diversity observed in the meta‐analysis.

We furthermore performed a TSA for the secondary outcome, interpersonal problems (for the main comparison versus placebo), based on the following priori assumptions:

the SD of the secondary outcome;

an anticipated MIREDIF defined in a trial reporting on this or we used a ½ SD on the used scale;

a maximum type I error of 0.8% (due to 11 secondary outcomes; Jakobsen 2014);

a maximum type II error of 10% (minimum 90% power; Castellini 2018); and

the diversity observed in the meta‐analysis.

For the secondary outcomes, 'attrition', and 'non‐serious adverse events', we calculated the a priori diversity‐adjusted required information size (DARIS; i.e. number of participants in the meta‐analysis required to detect or reject a specific intervention effect) and performed a Trial Sequential Analysis for these outcomes based on the following assumptions (Brok 2008; Brok 2009; Thorlund 2009; Wetterslev 2008; Wetterslev 2009):

Proportion of participants in the control group with adverse events;

Relative risk reduction of 40% (20% on 'non‐serious adverse events');

Type I error of 0.8% (due to 11 secondary outcomes; Jakobsen 2014);

Type II error of 10%;

Observed diversity of the meta‐analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

We assessed the impact of heterogeneity on the overall pooled effect estimate. First, we visually inspected the forest plot for 'outliers' that might contribute to heterogeneity and then removed them one‐by‐one to assess their impact on the overall outcome. Overall results were reported in the main analysis with outliers excluded, while we also conducted sensitivity analyses including these outliers.

We conducted sensitivity analyses to determine whether findings were sensitive to the following.

Imprecision, as assessed by GRADE, by conducting TSAs on the primary outcomes and for the secondary outcomes (for the main comparison versus placebo) where we were uncertain about the assessment of imprecision.

Differences when adding data from end‐of‐period data from cross‐over trials to the analyses.

-

Decisions made during the review process in relation to the:

choice of data (differences between data from trial registers and data from peer reviewed sources);

exclusion of outliers; and

type of model used for analysis (repeating the analysis using the fixed‐effect model to test the robustness of the results).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used Gradepro (GRADEpro 2021) to construct summary of findings tables. We reported the four primary outcomes (BPD severity, self‐harm, suicide‐related outcomes, and psychosocial functioning) and three secondary outcomes (interpersonal problems, attrition, and adverse events). We produced three summary of findings tables; one focusing on the comparison between antipsychotics and placebo at end of treatment, one on antidepressants compared with placebo at end of treatment, and one on mood stabilisers compared with placebo at end of treatment.