CASE REPORT

A 55-year-old man presented with severe, diffuse, and sharp abdominal pain for 1-week duration associated with numerous episodes of watery, nonbloody diarrhea. He also reported intermittent subjective fever and chills. Medical history included HIV for 30 years with poor compliance with an antiretroviral regimen, recent pneumocystis pneumonia, and previous cryptococcal meningitis. Physical examination revealed an ill-appearing, cachectic man with mild abdominal tenderness. Laboratory work revealed a white blood cell count of 18.5 K/μL (ref: 4.0–10.8 K/μL) with 84% neutrophils (ref: 40%–75%), sodium 132 mmol/L (ref: 135–146 mmol/L), and potassium 2.7 mmol/L (ref: 3.5–5.1 mmol/L). His viral load was 109,385 copies/mL (ref: neg copies/mL) and he had an absolute CD4 count of 56 lymphocytes/μL (ref: 330–1,520 lymphocytes/μL). Liver chemistries were unremarkable. Stool studies for regional pathogens, ova and parasites, and clostridium difficile were negative.

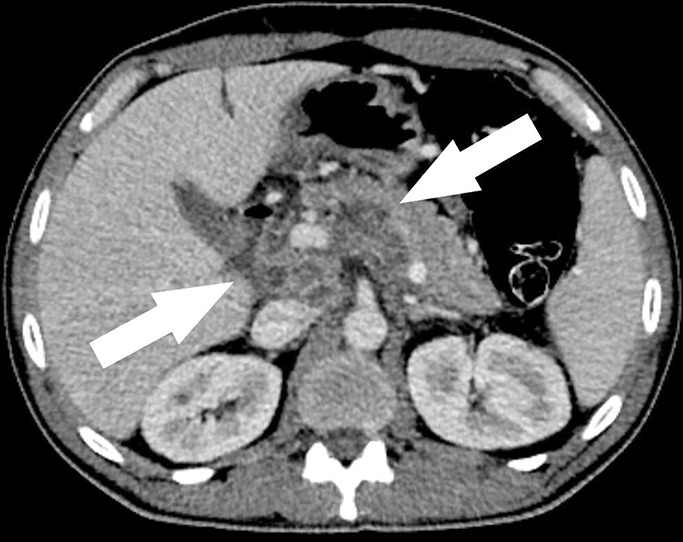

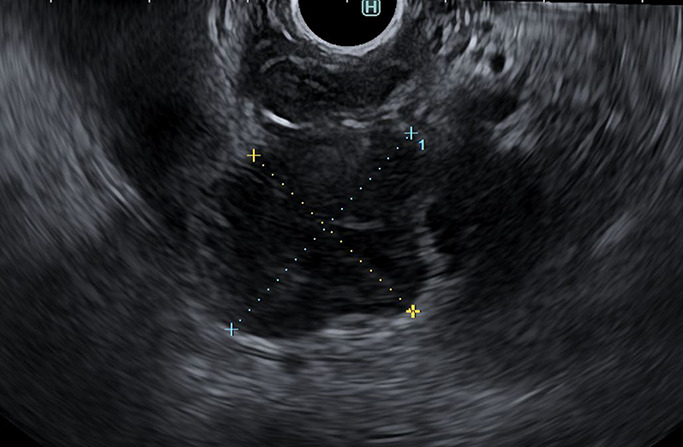

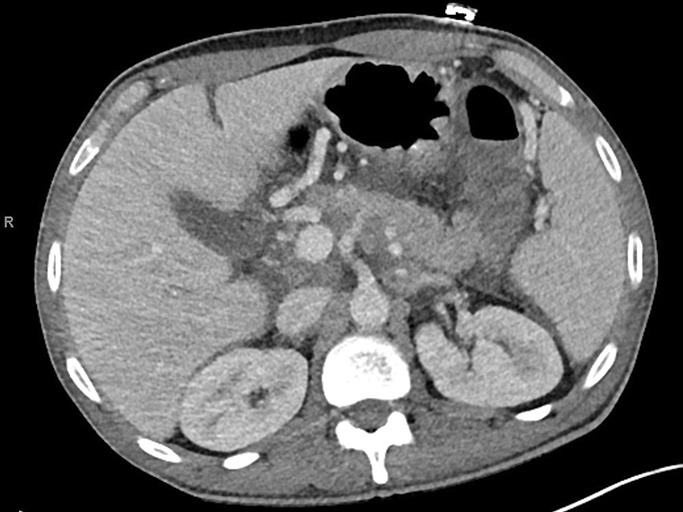

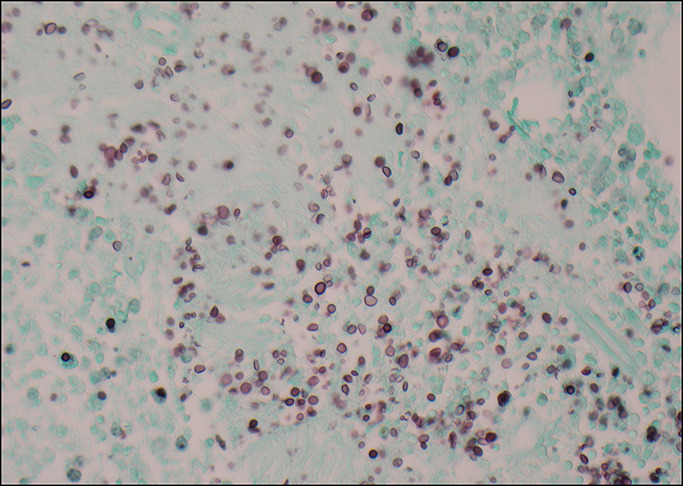

Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography revealed ill-defined cystic/necrotic upper abdominal lymphadenopathy with mass effect and possible invasion of the adjacent liver (Figure 1). The pancreas and caudate lobe of the liver were inseparable from the mass, which raised concern for primary pancreatic tumor or lymphoma. He underwent endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy of the peripancreatic mass with pathology consistent with a cryptococcoma (Figures 2–4). He was started on amphotericin B and transitioned to high-dose fluconazole because of adverse effects. Repeat imaging revealed significant reduction of the mesenteric lymphadenopathy. He was discharged in a stable condition and remained on fluconazole indefinitely.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography image showing ill-defined cystic/necrotic upper abdominal lymphadenopathy with mass effect and possible invasion of the adjacent liver.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic ultrasound imaging showing a peripancreatic mass.

Figure 4.

Significant reduction of the mesenteric lymphadenopathy after antifungal therapy initiation.

Figure 3.

Grocott methenamine silver stain showing fungal yeast with narrow base budding.

The etiologies for abdominal pain in immunocompromised individuals are broad and include infectious, malignant, and inflammatory processes. Infections such as tuberculosis and nontuberculosis mycobacterial infections can also cause lymphadenopathy.1,2 Cryptococcal infection remains the second most common cause of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related mortality after tuberculosis.3 The most common sites of cryptococcal infection are lungs, the brain, eyes, or the central nervous system. Abdominal dissemination is a rare feature of cryptococcal infection.4 Although most cases of cryptococcus occur in immunocompromised patients, it can also happen in immunocompetent patients.5 Therefore, clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for opportunistic infections in patients presenting with abdominal pain, especially in the setting of an immunocompromised state. Lesions can appear to be malignant and mimic lymphomas or other primary neoplasms. Biopsy using endoscopic ultrasound can be useful in diagnosis of cryptococcoma. Early identification and treatment of cryptococcal infections as well as education on antiretroviral therapy compliance can increase survival rates and lead to lower healthcare-related costs.

DISCLOSURES

Author contributions: M. Dzwonkowski wrote the manuscript and is the article guarantor. N. Shah and U. Iqbal revised the manuscript. B. Confer revised the manuscript and provided images.

Financial disclosure: None to report.

Informed consent was obtained for this case report.

Contributor Information

Nihit Shah, Email: nmshah@geisinger.edu.

Umair Iqbal, Email: uiqbal@geisinger.edu.

Bradley Confer, Email: bconfer1@geisinger.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Glushko T, He L, McNamee W, Babu AS, Simpson SA. HIV lymphadenopathy: Differential diagnosis and important imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216(2):526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weprin L, Zollinger R, Clausen K, Thomas FB. Kaposi's sarcoma: Endoscopic observations of gastric and colon involvement. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1982;4(4):357–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajasingham R, Smith RM, Park BJ, et al. Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: An updated analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(8):873–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sundar R, Rao L, Vasudevan G, Gowda PBC, Radhakrishna RN. Gastric cryptococcal infection as an initial presentation of AIDS: A rare case report. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2011;4(1):79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quincho-Lopez A, Kojima N, Nesemann JM, Verona-Rubio R, Carayhua-Perez D. Cryptococcal infection of the colon in a patient without concurrent human immunodeficiency infection: A case report and literature review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;40(12):2623–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]