Abstract

Background

Mental health disorders in the workplace have increasingly been recognised as a problem in most countries given their high economic burden. However, few reviews have examined the relationship between mental health and worker productivity.

Objective

To review the relationship between mental health and lost productivity and undertake a critical review of the published literature.

Methods

A critical review was undertaken to identify relevant studies published in MEDLINE and EconLit from 1 January 2008 to 31 May 2020, and to examine the type of data and methods employed, study findings and limitations, and existing gaps in the literature. Studies were critically appraised, namely whether they recognised and/or addressed endogeneity and unobserved heterogeneity, and a narrative synthesis of the existing evidence was undertaken.

Results

Thirty-eight (38) relevant studies were found. There was clear evidence that poor mental health (mostly measured as depression and/or anxiety) was associated with lost productivity (i.e., absenteeism and presenteeism). However, only the most common mental disorders were typically examined. Studies employed questionnaires/surveys and administrative data and regression analysis. Few studies used longitudinal data, controlled for unobserved heterogeneity or addressed endogeneity; therefore, few studies were considered high quality.

Conclusion

Despite consistent findings, more high-quality, longitudinal and causal inference studies are needed to provide clear policy recommendations. Moreover, future research should seek to understand how working conditions and work arrangements as well as workplace policies impact presenteeism.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40258-022-00761-w.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Despite clear evidence that poor mental health is associated with lost productivity at work, more evidence is required to understand the extent to which mental illness decreases productivity and the mechanisms through which this occurs in order to provide appropriate policy responses. |

| A better understanding of the relationship between mental illness and worker productivity is needed to understand the trade-offs between presenteeism and absenteeism. |

| Workplace policies that limit and help workers manage job stress can help improve workers’ productivity. |

Introduction

Mental health disorders in the workplace, such as depression and anxiety, have increasingly been recognised as a problem in most countries. Using a human capital approach, the global economic burden of mental illness was estimated to be US$$2.5 trillion in 2010 increasing to US$$6.1 trillion in 2030; most of this burden was due to lost productivity, defined as absenteeism and presenteeism [1]. Workplaces that promote good mental health and support individuals with mental illnesses are more likely to reduce absenteeism (i.e., decreased number of days away from work) and presenteeism (i.e., diminished productivity while at work), and thus increase worker productivity [2]. Burton et al. provided a review of the association between mental health and worker productivity [3]. The authors found that depressive disorders were the most common mental health disorder among most workforces and that most studies examined found a positive association between the presence of mental health disorders and absenteeism (particularly short-term disability absences). They also found that workplace policies that provide employees with access to evidence-based care result in reduced absenteeism, disability and lost productivity [3].

However, this review is now outdated. Prevalence rates for common mental disorders have increased [4], while workplaces have also responded with attempts to reduce stigma and the potential economic impact [5], necessitating the need for an updated assessment of the evidence. Furthermore, given that most of the global economic burden of mental illness is due to lost productivity [1], it is important to have a good understanding of the existing literature on this outcome. While the previous review focused on the prevalence of certain mental health conditions and the available interventions and workplace policies, this review focused on the measures of lost productivity and the instruments used, as well as the data and methods employed, which the previous review did not examine in depth. Thus, the objectives of this paper were to update the Burton et al. review [3] on the association between mental health and lost productivity, and undertake a critical review of the literature that has been published since then, specifically how researchers have studied this relationship, the type of data and databases they have employed, the methods they have used, their findings, and the existing gaps in the literature.

Methods

We undertook a critical review, i.e., a review that presents, analyses and synthesises evidence from diverse sources by extensively searching the literature and critically evaluating its quality [6], ultimately identifying the most significant papers in the field.1 We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement [7] to guide our analysis. Our review focused on all studies published since 2008, which examined the relationship between mental health and workplace-related productivity among working-age adults. We used the Population, Intervention, Control, Outcomes, and Study design (known as PICOS) criteria to guide the development of the search strategy.

Eligibility Criteria

The populations of interest comprised working-age adults (18–65 years old). Studies focusing solely on volunteers and/or caregivers (i.e., unpaid workers) were excluded. The intervention(s), or rather more appropriately the exposure(s), had to be a diagnosis of any mental disorder/illness or self-reported mental health problem(s). Any studies that examined substance use and/or physical health in addition to mental health were included if results were reported separately for mental health-related outcomes. The control or comparator group, where applicable, included working age individuals without a mental disorder/illness or mental health problem(s). The outcome(s) included lost workplace productivity measured by absenteeism, presenteeism, sick leave, short- and/or long-term disability, or job loss. Studies that examined productivity of home-related activities (e.g., housework) were excluded. Studies with an observational study design and/or regression analysis were included; randomised control trials, cost-of-illness studies and economic evaluations were excluded (the first two were only included if they examined the relationship between mental health and lost productivity). Only original studies were considered; however, relevant reviews were retained for reference checking to find relevant studies, which may not have been captured by the search strategy.

Search Strategy

We searched literature published in English from 1 January 2008 to 31 May 2020. Structured searches were done in MEDLINE and EconLit to capture the most relevant literature published in the medical and economics fields, respectively. We also undertook relevant searches in Google and on specific websites of interest (e.g., UK Parliament Hansard, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Centre for Mental Health, the Health Foundation, the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the King’s Fund) and a hand search of the references of key papers [8]. Search terms or strings were developed on the basis of four concepts: population or workplace, intervention/exposure (i.e., presence of mental disorder/illness), work-related outcomes, and study design (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Concepts and search terms used to identify relevant studies

| Concept | Search terms |

|---|---|

| Population | Work, workplace, worker, labourer/laborer, employment, employee, occupation |

| Intervention/exposure | Mental health, mental illness, mental wellbeing, mental hygiene, burnout, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, psychotic disorders, psychosis, bipolar disorder, mania, depression, unipolar disorder, mood disorder, dysthymia, anxiety, stress, phobia, panic disorder, neurosis, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, eating disorder, personality disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, suicide, suicide ideation, self-harm, adult ADHD |

| Outcome | Productivity, absenteeism, presenteeism, sick leave, short-term disability, long-term disability |

| Study design | Observational, regression |

ADHD attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Study Selection

After duplicate records were removed, one reviewer (LB) screened all titles and abstracts while additional reviewers (CdO and RJ) were brought in for discussion, if/where necessary. Articles were excluded either because they did not examine the relationship between mental health and lost productivity (e.g., some cost-of-illness studies) or were mainly focused on physical health. Subsequently, all relevant full-text articles were retrieved and screened by one reviewer (LB) to confirm eligibility; additional reviewers (MS, RJ or CdO) were brought in, if/where necessary.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers (LB and MS) undertook the data extraction, and an additional reviewer (RJ or CdO) was assigned to resolve any disagreements. The research team developed a data extraction form, based on the Cochrane good practice data extraction form, which included study information (author(s), year of publication), country (where the study was published or conducted), aims of study, study design (cross-sectional, longitudinal), data source(s) (i.e., database(s), surveys/questionnaires), study population (sample size, age range), mental disorder(s) examined, workplace outcome examined (absenteeism, presenteeism, short-term disability, long-term disability, job loss, other), methods employed (statistical analysis, regression model employed), and results/key findings.

Quality Assessment

We reviewed the methods employed in the studies to assess their quality and robustness, drawing loosely on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, a risk-of-bias assessment tool for observational studies [9]. We paid particular attention to whether studies were able to move beyond simple associations and attempted to address causal inference, where necessary, and whether they took account of endogeneity (i.e., cases where the explained variable and the explanatory variable are determined simultaneously) and/or unobserved heterogeneity (i.e., cases where the presence of unexplained (observed) differences between individuals are associated with the (observed) variables of interest), which are common issues when examining the relationship between mental health and lost productivity. All studies that recognised and/or accounted for these issues were considered high quality. We also examined the type of data/databases employed (i.e., cross-sectional or longitudinal data and representative, population-based samples), findings, and limitations (and the extent to which these impacted the findings), which were also considered when determining the quality of a study.

Data Synthesis

Given the heterogeneity of studies examined, undertaking a meta-analysis was not possible. Therefore, we undertook a narrative synthesis of the relevant literature, where we synthesised the existing evidence by mental disorder/illness and workplace outcome (absenteeism, presenteeism, sick leave, short- and long-term disability, or job loss), if/where appropriate.

Results

Study Selection

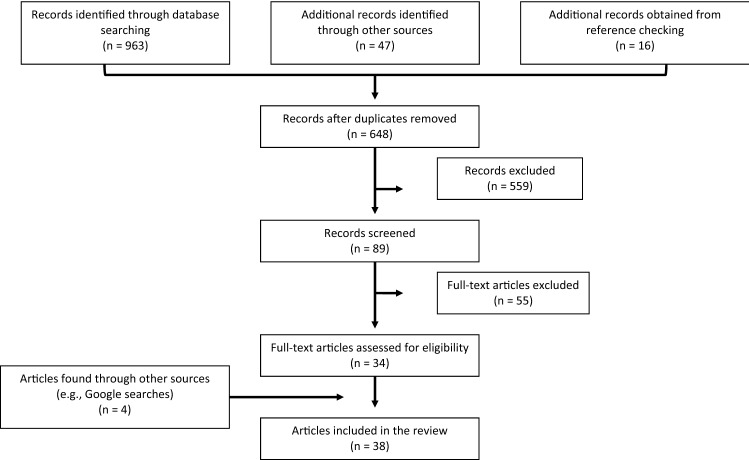

After all citations were merged and duplicates removed, our search produced 648 unique records, of which 89 full texts were assessed; four studies were obtained from other sources (e.g., Google searches). Ultimately, 38 studies were included in the final review [10–47] (see Fig. 1) and relevant data were extracted (see Table 2 and Table A1 in the Appendix for more details).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table 2.

Details of included studies

| Study information + country | Aim(s) of study + Study design | Data source + Study population | Mental disorder(s) + Workplace outcome(s) | Methods | Key finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asami et al. (2015); Japan |

To investigate whether severity of depressive symptoms was associated with productivity impairments among workers, regardless of respondents' awareness of depression as exhibited in them having been diagnosed or undiagnosed Cross-sectional |

National Health and Wellness Survey n = 17,820; 18 years and over |

Depression Absenteeism, presenteeism, overall work productivity loss and activity impairment |

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to measure the frequency and severity of depressive symptoms (and compared to self-reported diagnosis of depression). Absenteeism, presenteeism, productivity loss and activity impairment were assessed using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire. Generalized linear models specifying a negative binomial distribution and log-link function were used to model the workplace outcomes. | Among the undiagnosed, high severity workers had greater overall work impairment than low severity workers. Significant interactions between diagnosis and severity indicated greater impairments among undiagnosed than among diagnosed respondents, except on absenteeism. |

| Beck et al. (2011); USA |

To assess the relationship between depression symptom severity and productivity loss among patients initiating treatment for depression Cross-sectional |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 771; older than 18 years old |

Depression Absenteeism and presenteeism |

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to measure severity of depression symptoms. Questions about work function were obtained from Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire, a self-report measure of the amount of absence from work due to health problems, as well as productivity impairment while at work (presenteeism) experienced during the previous 7 days. Generalized linear models were estimated to investigate the relationship between depression symptoms and productivity loss while adjusting for potential confounders. | Depression symptom severity was strongly associated with productivity loss (i.e., absenteeism [work loss] and presenteeism [productivity impairment]). |

| Evans-Lacko and Knapp (2016); Multiple countries (Brazil, Canada, China, Japan, South Korea, Mexico, South Africa, and USA) |

To estimate workplace productivity (absenteeism, presenteeism) associated with depression across eight diverse countries, to make population-level country estimates of annual absenteeism and presenteeism costs associated with depression and to examine individual, workplace and societal factors associated with lower productivity Cross-sectional |

Global Impact of Depression in the Workplace in Europe Audit Survey n = 8061; 18–64 years old |

Depression Absenteeism and presenteeism |

Previous diagnosis of depression was determined via self-report by asking respondents, "Have you ever personally been diagnosed as having depression by a doctor/medical professional?" Self-reported presenteeism was assessed using the WHO Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). Absenteeism was assessed using the following question, "The last time you experienced depression, how many working days did you take off work because of your depression''? Generalized linear models were used to examine bivariate and multivariable factors associated with: (a) depression-related absenteeism costs and (b) depression-related presenteeism costs. Generalized estimating equations with robust variance estimates to model within-country correlations. | Depression was positively associated with absenteeism and presenteeism across a diverse set of countries, in terms of both culture and GDP. |

| Jain et al. (2013); USA |

To examine the burden of depression on work productivity Cross-sectional |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 1051; 18 years and over |

Depression Absenteeism and presenteeism |

Depression severity was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Workplace productivity levels (absenteeism and presenteeism) were assessed using the Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI). The impact of the level of depression assessed by the PHQ-9 score on work productivity as measured by the HPQ and WPAI was assessed using a trend test based on an analysis of covariance. | Absenteeism and presenteeism were positively associated with severity of depression. |

| Johnston et al. (2019); Australia |

To investigate the relationship between overall levels of depression and individual symptoms, and workplace productivity amongst a large group of working adults Cross-sectional |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 4953; over 18 years old |

Depressive symptoms Absenteeism and presenteeism |

Depression symptomatology was measured using the PHQ-9. Work performance was assessed using a modified version of WHO-HPQ. Sickness absenteeism was assessed by asking ''how many days/shifts have you missed over the past 4 weeks due to sickness absence''. Presenteeism was assessed by asking ''how would you rate your overall performance on the days you worked during the past 28 days?'' on a scale of 0 (worse performance) to 10 (top performance). Linear regression was used to analyse the relationship between overall depression severity, sickness absenteeism and presenteeism. | Depression was positively related to presenteeism and absenteeism. |

| Suzuki et al. (2015); Japan |

To evaluate the influence of presenteeism on depression and sickness absence due to mental disease Longitudinal |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 1831; 21–65 years old |

Depression Absenteeism and presenteeism |

Depression was measured with the Japanese version of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6). Sickness presenteeism was assessed using World Health Organisation Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (WHO-HPQ). Multiple logistic regression was performed to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of absence due to mental disease across a 2-year follow up for the lowest tertile of absolute or relative presenteeism scores at baseline as the independent variables. Furthermore, multiple logistic regression was performed to estimate the OR and 95% CI of depression one year after baseline or increases in K6 scores for the lowest tertile of absolute or relative presenteeism scores at baseline as independent variables. | Workers with higher sickness presenteeism were found to have higher rates of depression and sickness absence due to mental disease. |

| Curkendall et al. (2010); USA |

To measure the extent to which patients receiving antidepressant therapy have reduced productivity (absenteeism and short-term disability) relative to a similar non depressed population, and to identify a subgroup of patients who have severe depression and compare their productivity losses with the population without any psychiatric conditions Cross-sectional |

Administrative claims data n = 22,427; age range not specified |

Depression Absenteeism, short-term disability |

Depression was determined through claims data where individuals were included if they had been dispensed at least one prescription for an antidepressant medication and had an ICD-9-CM diagnosis of depression. The presence of and count of the number of workdays missed because of short-term disability or absence was determined through the Health and Productivity Management databases. Generalized linear models using the gamma distribution and a log link were estimated for absence costs. Two-part regression models were used for disability costs (part 1 estimated the effect of depression on the probability of incurring any short-term disability leave and part 2 estimated the effect of depression on short-term disability costs among those who took disability leave). | Workers with depression were more likely to use short-term disability leave and have higher absenteeism (even after receiving anti-depressant treatment) than those without depression. |

| Hjarsbech et al. (2011); Denmark |

To investigate whether and to what extent non-clinical depressive symptoms and clinical depression are prospectively associated with the risk of long-term sickness absence Cross-sectional |

Study questionnaire/survey linked to register data n = 6985 (females only); no age range specified |

Depression Absenteeism |

Depressive symptoms were measured by the Major Depression Inventory (MDI). Long-term sickness absence was determined from the Danish National Register of Social Transfer Payments. Cox's proportional hazards model was used to calculate hazard ratios to analyse whether and to what extent depressive symptoms at baseline predicted time to onset of first long-term sickness absence during the 1 year follow up. | Reduced psychological health was associated with absenteeism. |

| Koopmans et al. (2008); The Netherlands |

To determine the duration of sickness absence due to depressive symptoms in the working population Cross-sectional |

Firm data n = 9450; age range not specified |

Depression Absenteeism |

Data on sickness absence due to depressive symptoms were obtained from the occupational health department's registration system. Absence periods were encoded by an occupational physician when symptoms were present. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were computed to determine the mean and median absence duration of sickness absence due to depressive symptoms. | Workers with depressive symptoms had longer episodes of absenteeism. |

| Lamichhane et al. (2017); South Korea |

To examine how depressive symptoms are prospectively associated with absence from work due to illness and accidents in Korean manufacturing workers Cross-sectional |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 2349; no age range specified |

Depression, depressive symptoms Absenteeism |

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Korean version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Absence due to accident and illness was determined using the following questions: (1) “Were you absent from work because of any accident occurring at work in the past year?” or (2) “Were you absent from work due to illness in the past year?” Several multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate the odds ratio for depressive symptoms for absence. | Workers with depressive symptoms (CES-D ≥ 16) were found to have higher odds of absenteeism. |

| Harvey et al. (2011); United Kingdom |

To test whether a web-based screening tool for depression could be used successfully in the workplace and whether it was possible to detect an association between rates of depression and objective measures of impaired workgroup performance Cross-sectional |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 1161; age range not specified |

Depression Presenteeism |

Depression was measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-9). Work performance (i.e., presenteeism) was defined based on number of senior consultations required, number of calls transferred, adherence (inverse percentage of the total online hours occurring compared with the total scheduled) and customer time (amount of call, wrap, offline and wait time as a percent of the scheduled hours plus overtime). The association between group level measures of depressive symptoms and performance was initially assessed using univariate linear regression. Multivariable models were then constructed to examine the impact of potential confounding factors. | Depressive symptoms were positively related to presenteeism (i.e., poorer work performance). |

| Ammerman et al. (2016); USA |

To determine the health care and labour productivity costs associated with major depressive disorder in high-risk, low-income mothers Cross-sectional |

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey n = 20,531 (females only); 18–35 years old |

Major depressive disorder Absenteeism |

Depression was ascertained using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis code of 296 or 311. Labour productivity outcomes were obtained from the survey and included employment status and, if working, whether any workdays were missed during the year and the number of workdays missed among subjects missing at least one day. Two-part models were used to model job absenteeism costs (in the 1st stage, logistic regression models were estimated to predict the probability of any job absenteeism; the 2nd stage estimated the number of days missed for all subjects missing at least one day). | Depression significantly increased the likelihood of absenteeism among high-risk, low-income mothers. |

| Buist-Bouwman et al. (2008); Multiple countries (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain) |

To evaluate which limitations mediate in the relation between depression and role functioning, and to address which activity limitations mediate most of the effect and the robustness of the findings, especially across different levels of mental and physical comorbidity Cross-sectional |

European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders data n = 5565; 18 years old and older |

Major depressive episode Absenteeism and presenteeism |

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) was used to assess depression. The European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders-WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (ESEMeD-WHODAS) was used to assess role functioning (i.e., absenteeism and presenteeism) in paid employment. A structural equation model for categorical and ordinal data was used to estimate the extent to which limitations mediated the association between depression and role functioning. Structural equation models for categorical and ordinal data were used to estimate the extent to which limitations mediated the association between major depressive episode and role functioning. | Depression had a strong negative effect on role functioning (i.e., absenteeism and presenteeism) mediated by cognition and feelings of embarrassment. |

| Hees et al. (2013); The Netherlands |

To examine both the temporal and directional relationship between depressive symptoms and various work outcomes (absenteeism, work productivity and work limitations) in patients with long-term sickness absence related to major depressive disorder Longitudinal |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 117; 18–65 years old |

Major depressive disorder Absenteeism and presenteeism |

Severity of depressive symptoms was assessed by the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD). Absenteeism was assessed using self-report diaries, where patients recorded the number of contract hours and hours of sickness absence. Work productivity was assessed using self-report records of work productivity on a scale of 1 (‘not productive at all’) to 10 (‘very productive’). Work limitations were assessed with three subscales of the Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ). Regression analysis was used to model work outcomes over time. To examine the direction of the relationship (i.e., the association between earlier depressive symptoms and later work outcomes, and the association between earlier work outcomes and later depressive symptoms), autoregressive models were used. | Higher level of depressive symptoms was associated with a decrease in work productivity (i.e., presenteeism), and an increase in absenteeism and work limitation. |

| Uribe et al. (2017); Colombia |

To estimate productivity losses due to absenteeism and presenteeism and their determinants in patients with depression Cross-sectional |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 107; 18–65 years old |

Major depressive disorder Absenteeism and presenteeism |

The diagnosis of major depressive disorder or double depression was determined according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., Text Revision) and the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision. The World Health Organisation's Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) was used to assess absenteeism and presenteeism. The relationship between major depressive disorder and absenteeism and presenteeism were examined using regression analysis [two-part model for absenteeism (1st part = probit regression, 2nd part = ordinary least squares regression) and linear regression for presenteeism = linear regression]. | Workers who rated their mental health favourably had a lower probability of absenteeism and fewer hours per month of presenteeism. |

| Woo et al. (2011); South Korea |

To estimate the lost productive time and its resulting cost among workers with major depressive disorder compared with a comparison group, and to estimate the change in productivity after 8 weeks of outpatient psychiatric treatment with antidepressants Longitudinal |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 193; 20–60 years old |

Major depressive disorder Absenteeism and presenteeism |

The Korean version of Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders was used to diagnose major depressive disorder. The Hamilton Rating Scales for Depression (HAM-D) was used to measure the severity of depressive symptoms. The Korean version of the Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) was used to measure productivity (absenteeism and presenteeism). T-tests, chi-square tests, and analysis of variance tests were performed depending on whether the variables were continuous or categorical, comparing subjects' demographic data and the data from the HPQ. The comparison group was compared to the major depressive disorder group at baseline, and the major depressive disorder group before and after treatment. | Workers with major depressive disorder had significantly higher absenteeism and presenteeism than those without medical psychiatric illness. After 8 weeks of treatment, absenteeism and clinical symptoms of depression were significantly reduced and associated with significant improvement in self-rated job performance. |

| Simon et al. (2008); USA |

To evaluate the relationship between mood symptoms and work productivity in people treated for bipolar disorder Longitudinal |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 412; 64 years old and under |

Bipolar disorder Absenteeism, employment |

Bipolar disorder was determined using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (current depression, past depression, current mania, past mania, substance abuse). Workplace outcomes were determined through questions regarding days of disability adapted from the National Health Interview Survey. Regression analysis was performed to examine the probability of paid employment using generalized estimating equations with a log link and the relationship between the number of days missed from work and severity of mood symptoms using generalized estimating equations with a linear link. | Major depression was strongly and consistently associated with decreased probability of employment and absenteeism; symptoms of mania or hypomania were not significantly associated with employment or absenteeism. |

| McMorris et al. (2010); USA |

To evaluate a group of subjects with bipolar I disorder by collecting data on workplace productivity, employment issues and healthcare resource utilisation, and to compare the results with those from a group of subjects with no history of any type of bipolar disorder/serious mental illness Cross-sectional |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 417; 18–64 years old |

Bipolar disorder Absenteeism, workplace productivity, short- and long-term disability |

Bipolar disorder was determined using the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MCQ). Workplace outcomes were determined using the Endicott Work Productivity Scale (EWPS). Linear regression analyses were conducted to compare the results from subjects in the bipolar I disorder group with the results from the normative group on measures of work productivity. | Workers with bipolar disorder were more likely to report lower levels of workplace productivity, more likely to miss work, have worked reduced hours due to medical or mental health issues, and receive disability payments. |

| Banerjee et al. (2017); USA |

To estimate the effect of mental illness on labour market outcomes using a structural equation model with a latent index for mental illness Cross-sectional |

National Comorbidity Survey Replication and the National Latino and Asian American Study n = 7566; 25–64 years old |

Major depressive episode, anxiety (social phobia, panic attack, generalised anxiety disorder) Absenteeism, employment, labour force participation, number of weeks worked |

Clinical diagnoses of psychiatric disorders were determined based on the responses to survey questions. Data are on labour market outcomes were obtained from survey responses. The effect of psychiatric disorders on labour market outcomes was estimated using a Multiple Indicator and Multiple Cause model (i.e., a structural equation model). In addition, the potentially endogenous nature of the mental illness variable was addressed using covariance instruments. | Mental illness adversely affects employment and labour force participation and reduces the number of weeks worked and increases work absenteeism. |

| Knudsen et al. (2013); Norway |

To examine and compare the prospective effect of the common mental disorders (anxiety and depression) on duration and recurrence of sickness absence, and to investigate whether the effect of common mental disorder on sickness absence is detectable over time Longitudinal |

Hordaland Health Study data linked to state registry data n = 13,436; age range not specified |

Depression, anxiety Absenteeism |

Anxiety and depression were assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Information on sickness absence (SA) episodes was retrieved from official Norwegian registries over state paid SA benefits. The effects of anxiety and depression on first sickness absence episode, the duration of the first sickness absence episode, and whether the effect remained over prolonged time after baseline, were assessed using Cox regression. The association between anxiety and depression and the number of sickness absence episodes was examined using multinominal logistic regression. | Comorbid anxiety and depression, and anxiety only were significant risk factors for absenteeism, while depression only was not. Anxiety and depression were stronger predictors for longer duration and with more frequent recurrence of absenteeism. |

| Bokma et al. (2017); The Netherlands |

To expand on the current literature by studying severity of disability, work absenteeism and presenteeism associated with anxiety and/or depressive disorders, chronic somatic diseases, and their comorbidity in a wide range of chronic somatic diseases Cross-sectional |

Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety n = 1462; 18–65 years old |

Depressive disorders, anxiety Absenteeism, presenteeism and disability |

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) was used to assess mental illness. Disability during the previous 30 days was assessed using the WHO-Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO-DAS II). Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for Costs Associated with Psychiatric illness (TiC-P) was used to assess absenteeism and presenteeism. Statistical analyses (including multivariate regression models) were used to compare baseline characteristics of anxiety and/or depressive disorders, to compare presence of chronic somatic diseases in anxiety and/or depressive disorders in patients versus controls, to test the impact of anxiety and/or depressive disorders, chronic somatic diseases, and their interaction on disability total and domain scores, patients to controls, and to test the impact of anxiety and/or depressive disorders, chronic somatic diseases, and physical mental-comorbidity on work absenteeism and presenteeism. Sensitivity analyses were done to check for possible bias. | Anxiety and depressive disorders were associated with worse absenteeism and presenteeism outcomes and disability (compared to chronic somatic diseases). |

| Bouwmans et al. (2014); The Netherlands |

To assess the explanatory power of disease severity and health-related quality of life on absenteeism and presenteeism in a working population suffering from depression and/or anxiety disorders Cross-sectional |

Randomised control trial data n = 425; age range not specified |

Depression, anxiety Absenteeism and presenteeism |

Depression and/or anxiety disorder was determined using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Productivity losses (absenteeism and presenteeism) were measured using the Short-Form Health and Labour Questionnaire (SF-HLQ). Multinomial logistic regression analyses were performed to explore associations of the type of the disorder and health-related quality of life with different types of productivity losses. Multivariate regression analyses were performed to assess associations with the duration of absenteeism. | Depression and/or anxiety were significantly associated with productivity losses (i.e., absenteeism and presenteeism). |

| Plaisier et al. (2010); The Netherlands |

To examine and compare psychopathological characteristics of depressive and anxiety disorders in their effect on work functioning Cross-sectional |

Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety n = 1976; 18–65 years old |

Depression, anxiety Absenteeism and presenteeism |

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI, lifetime version 2.1) was used to diagnose depressive and anxiety disorders. Severity of anxiety/depressive symptoms (in the last week) was assessed by the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and the Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology (IDS) Questionnaire, respectively. Work functioning (i.e., absenteeism and presenteeism) was assessed with the Trimbos/iMTA Questionnaire for costs associated with Psychiatric Illnesses (TiC-P). Multinomial logistic regression analyses were used to test associations of socio-demographic characteristics, somatic health and diagnoses of anxiety and depression with categories of work absenteeism and decreased work performance. | Workers with chronic depressive disorder, a generalized anxiety disorder, and more severity of both anxiety and depressive disorder had higher odds for the risk of absenteeism and decreased work performance. |

| Erickson et al. (2009); USA |

To examine the impact of anxiety severity on work‐related outcomes in an anxiety specialty clinic population, and to examine psychometric properties (sensitivity, internal reliability, and construct validity) of the four instruments and to assess their relative suitability for use in this population Longitudinal |

Study questionnaire/survey linked to medical records n = 81; 18 years old and older |

Anxiety Absenteeism and presenteeism |

Anxiety severity was determined using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). Self-reported work-productivity was measured using 4 work performance measures: (1) Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ); (2) Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI); (3) Endicott Work Productivity Scale (EWPS); (4) Functional Status Questionnaire Work Performance Scale (WPS). Workers were divided into two groups (high and low anxiety) and compared on demographic, job, and work-related data using t tests and Chi-square tests. Effect sizes for differences between groups were calculated using Cohen’s d. | Workers with greater anxiety had lower work performance (i.e., higher absenteeism and presenteeism). |

| Fernandes et al. (2017); Brazil |

To analyse the prevalence of various anxiety disorders among mental and behavioural disorders as a cause for the leave of absence of workers Cross-sectional |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 412; over 18 years old |

Anxiety disorders (mixed anxiety-depressed disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorders, acute reaction to stress, PTSD, adjustment disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder) Absenteeism |

The Unified Benefits System from the National Social Security Institute of the city of Teresina, Piauí, Brazil was used to obtain data on sick pay and disability retirement due to anxiety disorders. Statistical analyses were used to analyse the prevalence of anxiety disorders as a cause of workers’ absence. A chi-square goodness of fit test was used to examine the difference between the frequencies of a same variable’s categories and a chi-square independence test was used to verify the association between time of absence and the variables related to social security and socio-demographic characteristics. | Anxiety disorders were positively associated with absenteeism. |

| Park et al. (2014); South Korea |

To measure the lost productivity for working patients with panic disorder Longitudinal |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 108; 20–50 years old |

Panic disorder Absenteeism and presenteeism |

The Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS) was administered to assess the severity of symptoms of panic disorder and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) was administered to assess depressive symptoms. The Korean version of the WHO Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) was administered to measure lost workplace productive time, absenteeism and presenteeism. Chi-squared and t-tests were undertaken to compare demographic data, the HPQ, and the HAM-D between the panic disorder group and the matched control group and similar chi-squared and paired t-test analyses were performed to compare the panic disorder group at baseline and after treatment. | Workers with panic disorder had higher absenteeism and presenteeism. |

| Ling et al. (2017); USA |

To quantify the economic burden of binge‐eating disorder in terms of work productivity loss, healthcare resource utilisation, and health care costs Cross-sectional |

National Health and Wellness Survey and Validate Attitudes and Lifestyle Issues in Depression ADHD and Troubles with Eating Survey n = 1720; 18 years old and older |

Binge eating disorder Absenteeism, presenteeism and activity impairment |

The presence of binge eating disorder was determined using self‐reported data regarding the specific features and symptoms of binge eating disorder in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM‐5) criteria. Information on work productivity was collected using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire (WPAI). Generalized linear models with a log link and a negative binomial distribution were used to estimate work productivity loss and health care resource utilisation. | Workers with binge eating disorders reported greater levels of presenteeism and activity impairment than those without but no differences for absenteeism. |

| Able et al. (2014); Multiple countries (Germany, UK, Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands) |

To quantitatively address the burden of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in Europe (Germany, the UK, Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands), to describe adult experience leading to diagnosis and treatment of ADHD, and to compare those findings with results from the USA Cross-sectional |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 880; 18–64 years old |

ADHD Absenteeism, presenteeism, overall work productivity loss and activity impairment |

The diagnosis of and treatment for ADHD was ascertained using the following information: (1) the specialties of health care providers consulted regarding ADHD symptoms prior to diagnosis; (2) the specialties of health care providers initially diagnosing ADHD; (3) the time to diagnosis following the first visit to a health care provider for consultation regarding ADHD symptoms; (4) conditions for which respondents received diagnoses prior to their initial ADHD diagnosis (alcoholism, autism, Asperger syndrome, other substance use/abuse, bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety-related disorder, schizophrenia, any learning disability, conduct disorder, and any other mental health conditions); (5) respondent evaluations of opinions on health care providers and services; (6) current use of ADHD medications; and (7) types of nonpharmacological treatments ever received for ADHD. The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire was used to measure absenteeism, presenteeism, overall work productivity loss, and activity impairment. Multivariate linear regression analyses were used to compare the impact of ADHD on work productivity and activity impairments. | Workers with ADHD were more likely to have absenteeism, presenteeism and work impairment. |

| de Graaf et al. (2008); Multiple countries (Belgium, Colombia, France, Germany, Italy, Lebanon, Mexico, the Netherlands, Spain, and USA) |

To estimate the prevalence and workplace consequences of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Cross-sectional |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 7075; 18–44 years old |

ADHD Absenteeism and presenteeism |

ADHD was determined using the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey. Days out of role were measured using the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO-DAS). Linear regression analysis was used to estimate associations of ADHD with lost role performance. | ADHD was associated with more annual days of excess lost role performance (i.e., absenteeism and presenteeism). |

| Kessler et al. (2009); USA |

To determine the prevalence and workplace costs of ADHD to evaluate the possible return on investment of a workplace screening–treatment program for workers with ADHD Cross-sectional |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 8563; age range not specified |

ADHD Absenteeism and presenteeism, workplace accidents-injuries |

ADHD was assessed with the WHO Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS). Sickness absence, work performance and workplace accidents-injuries were assessed using the WHO Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). A logistic link function was used to predict any sickness absence and any workplace accident-injury and a generalized linear model that allowed for non-linear link functions and for non-normal distributions of prediction errors was used to predict the number of sickness absence days and work performance. | ADHD was associated with a reduction in presenteeism (work performance), higher odds of absenteeism (sickness absence), and higher odds of workplace accidents-injuries. |

| Bubonya et al. (2017); Australia |

To analyse the relationship between mental health and workplace productivity (absenteeism and presenteeism) Longitudinal |

Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey n = 16,513 (presenteeism analysis), n = 12,560 (absenteeism analysis); 15–64 years old |

Poor mental health Absenteeism and presenteeism |

Mental health was derived from the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5). Absenteeism was determined using a self-reported measure of the number of paid sick leave days taken in the previous 12 months. Presenteeism was derived from Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). Absenteeism was modeled using a correlated random effects negative binomial model. Presenteeism was modeled using a conditional fixed-effects logit model. | Absenteeism and presenteeism were higher among workers who reported being in poor mental health. |

| Wooden et al. (2016); Australia |

To revisit the relationship between mental health and sickness absence and to quantify the bias due to unobserved characteristics that are time invariant Longitudinal |

Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey n = 13,622; 15–64 years old |

Poor mental health Absenteeism |

Mental health was measured with the five-item Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5). Absenteeism was determined using a self-reported count of the number of days absent from work while on paid sick leave during the previous 12 months. Correlated random effects negative binomial regression models were used to model the number of annual paid sickness absence days. | Poor mental health is a risk factor affecting work attendance (i.e., absenteeism), but the magnitude of this effect, at least in a country where the rate of sickness absence is relatively low, was modest. As a result of omitted variables bias, previous research may have overstated the magnitude of the association between poor mental health and work-related sickness absence. |

| Mauramo et al. (2018); Finland |

To examine whether common mental disorders at different severity levels are associated with sickness absence in a Finnish cohort of midlife and aging female and male municipal employees Cross-sectional |

Helsinki Health Study data linked to employer register data n = 6554; age range not specified |

Common mental disorders Absenteeism |

The General Health Questionnaire 12-item version (GHQ-12) was used to measure common mental disorders. Sickness absence spells were obtained from the employer's personnel registry. Quasi-Poisson regression models producing rate ratios with 95% confidence intervals were fitted to examine associations between common mental disorders and the number of sickness absence spells in the follow-up of 5 years. | Increasing severity of common mental disorders increased the risk of short, intermediate, and long absenteeism spells. |

| Chong et al. (2012); Singapore |

To examine the association between mental disorders and work disability in the adult resident population Cross-sectional |

Singapore Mental Health Study n = 6429; 18 years and over |

Multiple mental disorders (major depression disorder, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, alcohol use disorder, alcohol dependency) Absenteeism and presenteeism |

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) was used to assess mental disorders. Employment-related information was collected using the modified employment module of the CIDI. Negative binomial regression was used to model the main effect of DSM-IV lifetime mental disorders, physical disorder, and comorbid mental–physical disorder on the rate of work-lost days (absenteeism) and work-cut days (presenteeism). | Among workers without any mental and physical disorders, absenteeism and presenteeism was significantly lower compared to those with any physical disorder only and comorbid mental-physical disorders. |

| de Graaf et al. (2012); The Netherlands |

To estimate work loss days due to absenteeism and presenteeism associated with commonly occurring mental and physical disorders Cross-sectional |

Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study n = 4715; 18–64 years old |

Multiple mental disorders (major depression disorder, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, anxiety [panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, specific phobia, generalised anxiety disorder], substance use disorders, ADHD) Absenteeism and presenteeism |

Mental disorders were assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Number of absent days and days of reduced quantitative and qualitative functioning while at work were measured by three questions based on the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO-DAS) (''How many days out of the past 30 were you totally unable to work or carry out your normal activities? How many days out of the past 30 were you able to work and carry out your normal activities, but had to cut down on what you did or not get as much done as usual? How many days out of the past 30 did you cut back on the quality of your work or how carefully you worked?'') Generalized linear models with gamma distribution and log link function were used to examine the relationship between work-related outcomes and mental disorders. | Workers with mental disorders had more work loss days due to absenteeism and presenteeism than those without mental disorders. |

| Hilton et al. (2010); Australia |

To estimate employee work productivity by mental health symptoms while considering different treatment-seeking behaviours Cross-sectional |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 60,556; over 18 years old |

Multiple mental disorders (depression, anxiety, and other emotional problems) Absenteeism and presenteeism |

The Kessler 6 (K6) was used to gauge severity or mental health symptoms, and specific WHO Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) questions relating to three types of mental disorders (depression, anxiety, and other emotional problems) was used to gauge treatment seeking behaviours. The WHO Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) was used to measure workplace productivity. A univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to understand the relationship between productivity and K6 severity categories and treatment-seeking behaviours. | Workers with higher psychological distress had lower productivity (i.e., higher absenteeism and presenteeism) than those with moderate and low distress. |

| Tsuchiya et al. (2012); Japan |

To estimate the impact of mental disorders on work performance (absenteeism and presenteeism), as well as to ascertain the prevalence and demographic correlates in a community sample of workers Cross-sectional |

World Mental Health Japan 2002–2005 Survey n = 530; 20–60 years old |

Multiple mental disorders (major depressive disorder, dysthymia, bipolar disorder I and II, specific phobia, social phobia, agoraphobia without panic disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, PTSD) Absenteeism and presenteeism |

Mental disorders were assessed using version 3.0 of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Work performance was assessed using the WHO Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). Regression analysis (i.e., linear regression model) was used to estimate the associations of mental disorders with work performance over 30 days and 12 months. | Mood disorders, including major depressive disorder, and alcohol use/dependence were associated with decreased work performance (presenteeism) but had no significant relationship with absenteeism. |

| Toyoshima et al. (2020); Japan |

To investigate the correlation between cognitive complaints, depressive symptoms and presenteeism of adult workers Cross-sectional |

Study questionnaire/survey n = 477; 20 years old and older |

Other disorders, including mental disorders (depressive symptoms, cognitive function) Presenteeism |

Subjective cognitive function was evaluated using the Cognitive Complaints in Bipolar Disorder Rating Assessment and depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Work limitations were determined using the Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ-8). The relationship between depressive symptoms, cognitive complaints and work limitations was examined using multiple regression analysis. | Cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms were significant predictors of presenteeism. |

Overview of Studies

All studies focused on individuals typically between the ages of 18 and 64/65 years. Some studies (n = 5) examined individuals 20 or 25 years and older [11, 12, 16, 28, 38] to account for younger individuals who might still be in school and thus not working, while other studies had different lower and upper age limits (e.g., age 15 [25, 47] and age 60 [11, 38] years, respectively). Most studies were from the USA (n = 10; 26%) and the Netherlands (n = 6; 16%); this result is line with the findings from a review of economic evaluations of workplace mental health interventions [48]. The remaining studies were from Australia (n = 4), Japan (n = 4), South Korea (n = 3), multiple countries (n = 4), Brazil (n = 1), Colombia (n = 1), Denmark (n = 1), Finland (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), Singapore (n = 1), and the United Kingdom (n = 1). Many studies did not specify the setting or industry or state the size of the firm where the study was undertaken (also found elsewhere [48]); consequently, this information was not included in the data extraction form.

Measures and Instruments/Tools Used

Mental Health

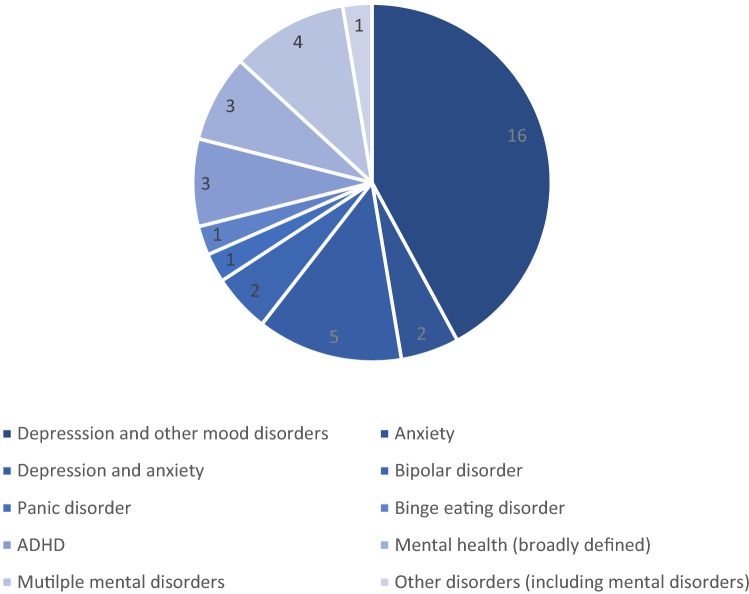

Most studies (n = 16) examined depression/depressive symptoms, major depressive disorder or other mood disorders (see Fig. 2). Two studies examined anxiety and five studied both anxiety and depression. A smaller number of studies examined other disorders—three studies examined attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), two studies focused on bipolar disorder, one examined panic disorder, one studied binge-eating disorder, and one looked at other disorders including mental disorders (depressive symptoms and cognitive function). Three studies looked at mental health broadly speaking (two studies examined poor mental health and another studied common mental disorders). Finally, four studies examined multiple mental disorders (e.g., depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, emotional disorders, substance use disorders, ADHD). Some studies used a binary indicator for the presence/absence of a mental disorder/poor mental health, while other analyses used different aggregate measures of mental illness or psychological distress, based on the number of recorded symptoms.

Fig. 2.

Studies by mental disorder. ADHD attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

A variety of instruments/tools were used to measure mental health, depending on the disorder. Depression was measured using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6 scale) [49], Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) depression scale [50], Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [51], Short General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) [52], Major Depression Inventory (MDI) [53], Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) [54], and Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5) [55]. In studies that examined both anxiety and depression (n = 2), the authors used either the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [56] or the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) [57]. In one study [42], severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms was assessed using the Beck Anxiety Inventory [58] and the Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology questionnaire [59], respectively. In another study [33], mood disorder was measured using the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) [60]. In one study [41], ADHD was assessed using the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey [61]; in another [35], it was assessed using the WHO Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale [62]. Panic disorders were measured using the Panic Disorder Severity Scale [63] in one study [16].

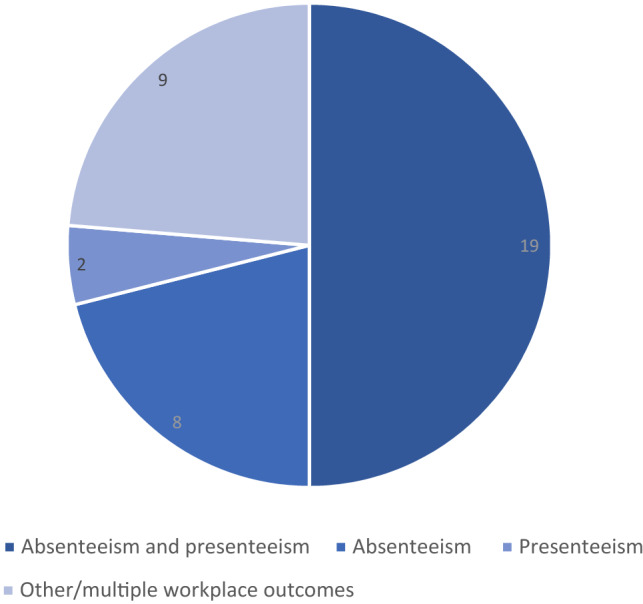

Lost Productivity

Nineteen studies examined both absenteeism and presenteeism, eight studies examined absenteeism only, two studies examined presenteeism only, and nine examined other or several workplace outcomes, such as employment, absenteeism, presenteeism, workplace accidents/injuries, short- and/or long-term disability, activity impairment and/or job loss (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Studies by workplace outcome

Five studies used the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire [64] (Beck et al. [27], Jain et al. [36], Able et al. [30], Asami et al. [31], Ling et al. [44]); three used the WHO’s Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HWP) [65] (Hjarsbech et al. [18], Woo et al. [38], Park et al. [16]) to determine absenteeism and presenteeism. A recent systematic review also found that that the WPAI was most frequently applied in economic evaluations and validation studies to measure lost productivity [66]. Two studies [12, 20] used the Work Limitations Questionnaire [67]. Other studies used a variety of different instruments to measure lost productivity, such as the Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for Costs Associated with Psychiatric illness (TiC-P) [68] (Bokma et al. [26]), the Short-Form Health and Labour Questionnaire [69] (Bouwmans et al. [45]), the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO-DAS) [70] (de Graaf et al. [23]) and the Endicott Work Productivity Scale [71] (McMorris et al. [33]). One study [43] made use of four work performance measures to examine lost productivity: WPAI [64], Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) [66], Endicott Work Productivity Scale (EWPS) [71] and Functional Status Questionnaire Work Performance Scale (WPS) [72].

Data Sources and Methods

Data

Most studies (n = 20) employed data collected through surveys/questionnaires, though some used publicly available datasets, such as the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey [29], the National Comorbidity Survey Replication [28] and the National Latino and Asian American Study [28], the US National Health and Wellness Survey [44], the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey [25, 47], and the Singapore Mental Health Study [24]. One study used administrative claims data [32]. Three studies made use of linked data, such as Hjarsbech et al. [18], which linked questionnaires to the Danish National Register of Social Transfer Payments; Erickson et al. [43], which utilised questionnaires linked to medical records, and Mauramo et al. [34], which used survey data from the Helsinki Health Study linked to employer's register data on sickness absence. Only one study employed trial data [45]. Most studies (n = 29; 76%) employed cross-sectional data; few used longitudinal data (n = 9; 24%).

Methods

Several studies (n = 8) used regression analysis to examine the relationship between mental health and lost productivity, namely linear regression [11, 17] and logistic regression models [25, 29, 42, 45]. Two studies employed two-part models, where the first part examined the probability/odds of workers experiencing absenteeism, while the second part modeled the number of hours of absenteeism [10] or the number of work days missed [29]. One paper employed Poisson regressions to model the rate of work-lost days (absenteeism) and work-cut days (presenteeism) [34]. Another study computed Kaplan–Meier survival curves to estimate the mean and median duration of sickness absence due to depressive symptoms [40], and one estimated a Cox's proportional hazards model to analyse whether and to what extent depressive symptoms at baseline predicted time to onset of first long-term sickness absence during the 1-year follow-up period [18]. Only one study employed instrumental variables to address the potential endogeneity of the mental illness variable employed [28] and four employed longitudinal data models [13, 20, 25, 47].

Evidence Synthesis

Almost all studies (n = 36) found a positive (and, many times, a strong) association between the presence of mental illness/disorders or poor mental health and productivity loss measured by absenteeism and/or presenteeism. Nevertheless, there were a few exceptions—one study found that mood disorders were associated with decreased presenteeism (i.e., work performance) but found no significant relationship between mood disorders and absenteeism [11]. Another study found that individuals with binge-eating disorders reported greater levels of presenteeism and lost productivity than those without but found no effect for absenteeism [44].

Many studies (n = 6) on depression examined both absenteeism and presenteeism where the presence of the former was positively associated with the latter (as was the case for studies, which examined only absenteeism and only presenteeism), and the latter was higher among those with higher severity of depression. These findings held in studies examining major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder (though one study found that symptoms of mania or hypomania were not significantly associated with absenteeism) [14]. Studies examining depression and anxiety (and anxiety alone, including panic disorder) generally examined both absenteeism and presenteeism and found that these disorders were significantly associated with lost productivity. One study found that workers with binge-eating disorder reported greater levels of presenteeism than those without but no differences in absenteeism. All studies on ADHD (n = 3) examined both absenteeism and presenteeism and found ADHD was associated with more days of missed work and poor work performance. Studies looking at mental health (broadly defined) typically examined absenteeism only, finding a positive relationship between both, though the magnitude of the effect was found to be modest in one study [47]. Studies examining multiple disorders (n = 4) also examined both absenteeism and presenteeism. Overall, having a mental disorder was positively associated with lost productivity; however, one study found no significant relationship between mood disorders and alcohol use/dependence and absenteeism [11].

Many studies (n = 6) found that higher severity of the disorder or co-occurring mental health conditions was associated with greater productivity loss. For example, Knudsen et al. found that while comorbid anxiety and depression and anxiety alone were significant risk factors for absenteeism, depression alone was not [37].

Some studies examined outcomes separately for men and women (n = 5) or examined specific groups (n = 1). For example, Ammerman et al. examined high-risk, low-income mothers with major depression and found that depression significantly increased the likelihood of absenteeism (i.e., missing workdays) among this group [29]. However, beyond gender, studies did not report on differences by ethnicity/race and/or age.

Overall, we found that the literature on this topic continues to examine the most common mental disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety) using similar data sources and analysis techniques as the Burton et al. review [3] (see Table 3). However, more recent literature shows that the positive relationship between the presence of mental disorders and lost productivity may not hold in all instances.

Table 3.

Comparison between the Burton et al. [3] and the de Oliveira et al. [current paper] reviews

| Burton et al. (2008) [3] (n = 16) |

de Oliveira et al. (2022) [current paper] (n = 38) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Aim of review |

To summarize the literature regarding the association between mental health conditions and worker productivity To review studies of workplace strategies and interventions that attempt to improve productivity for employees suffering with mental health problems |

To update the Burton et al. (2008) review on the association between mental health and lost productivity To examine how researchers have studied the relationship between mental health and lost productivity, the type of data and databases employed, the methods used, findings, and existing gaps in the literature |

| Time frame of analysis | Not specified (includes studies from 1994 to 2007) | 1 January 2008–31 May 2020 |

| Data employed |

National surveys Questionnaires/surveys Medical claims Firm data |

National surveys Questionnaires/surveys Medical claims Firm data Randomised control trial data (including data linkages) |

| Mental disorders examined |

Depression (including major depressive disorder, dysthymia) Bipolar disorder Anxiety ADHD Mental disorders/multiple mental disorders |

Depression (including major depressive disorder) Bipolar disorder Anxiety/anxiety disorders (e.g., panic disorder) ADHD Binge-eating disorder Mental disorders/multiple mental disorder (including poor mental health) |

| Workplace outcomes examined |

Absenteeism Presenteeism Productivity Work loss Short-term disability Functional disability/status Workers compensation |

Absenteeism Presenteeism Productivity Employment/labour force participation Short-term disability Long-term disability Activity impairment Number of weeks worked Workplace accidents-injuries |

| Methods |

Regression analysis Other statistical analyses (e.g., t tests) |

Regression analysis Other statistical analyses (e.g., t tests) |

| Main findings | Most studies found associations between mental health conditions and absenteeism (particularly short-term disability absences). In addition, results show that depression significantly impacts on-the-job productivity, i.e., presenteeism (when presenteeism is measured by a validated questionnaire) | Almost all studies found a positive (and, many times, a strong) association between mental health conditions and absenteeism and/or presenteeism. Nevertheless, there were a few exceptions—one study found that mood disorders were associated with decreased presenteeism (i.e., work performance) but found no significant relationship between mood disorders and absenteeism. Another study found that individuals with binge-eating disorders reported greater levels of presenteeism and lost productivity than those without but found no effect for absenteeism |

ADHD attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Discussion

The goal of this review was to provide a comprehensive overview and critical assessment of the most recent literature examining the relationship between mental health and workplace productivity, with a particular focus on data and methods employed. It provides clear evidence that poor mental health is associated with lost productivity, defined as increased absenteeism (i.e., more missed days from work) and increased presenteeism (i.e., decreased productivity at work). However, overall, only three studies were of high quality [25, 28, 47]. Studies with greater rigour and more robust methods, which accounted for unobserved heterogeneity for example, found a similar positive relationship but a smaller effect size [25, 47].

Other reviews have also found large significant associations between measures of mental health and lost productivity, such as absenteeism [3, 73–75]. For example, Burton et al. [3] found that depressive disorders were the most common mental health disorder among most workers, with many studies showing a positive association between the presence of mental health conditions and absenteeism, particularly short-term disability absences [3]. However, we found that studies employing superior methodological study design have shown the strength of the observed association may be smaller than previously thought.

Overall, our findings are in line with those from other reviews [73–75] and the Burton et al. study [3]. We too found that the most common disorder examined was depression, followed by depression and anxiety, the most studied workplace outcomes were both absenteeism and presenteeism, and that there was an association between mental disorders and both absenteeism and presenteeism. We found that studies employed a variety of data sources, from data collected from surveys/questionnaires to existing surveys and administrative data. Regression analysis was commonly used to examine the relationship between mental health and lost productivity, though there were some studies where the most appropriate regression model was not used given the outcome examined (e.g., linear regression models were used regardless of the type of outcome examined).

Some studies employed small sample sizes [20, 43], which are not representative of the broader population and can thus impact the generalizability of findings, and other studies that did use nationally representative population samples employed cross-sectional designs [11, 42, 46], which can limit causal inference. Therefore, the vast majority did not examine the causal effect of mental health on lost productivity, but rather only the association between the two. A notable exception was Banerjee et al. [28], who examined the potential endogeneity of the mental illness variable used. Moreover, few studies employed longitudinal data, which can help account for unobserved heterogeneity (that may be correlated with both mental health and lost productivity) and minimise the potential for reverse causality and omitted variable bias; Wooden et al. [47] and Bubonya et al. [25] were notable exceptions. Wooden et al. found that the association between poor mental health and the number of annual paid sickness absence days was much smaller once they accounted for unobserved heterogeneity and focused on within-person differences [47]. For example, the incidence rate ratios for the number of sickness absence days for employed women and men experiencing severe depressive symptoms were 1.31 and 1.38, respectively, in the negative binomial regression models but dropped to 1.10 and 1.13, respectively, once the authors controlled for unobserved heterogeneity through the inclusion of correlated random effects. Thus, it may be that previous research has overstated the magnitude of the association between poor mental health and lost productivity. More studies with rigorous causal inference are required to help strengthen the ability to make informed policy recommendations.

Few studies explored the factors that might explain absenteeism and/or presenteeism due to mental health. Again, the study by Bubonya et al. was a notable exception [25], providing several important insights on the relationship between mental health and lost productivity. According to the authors, initiatives that limit and help workers manage job stress seem to be the most promising avenue for improving workers’ productivity. Furthermore, the authors found that presenteeism rates among workers with poor mental health were relatively insensitive to work environments, in line with other research from the UK [76]; consequently, they suggested that developing institutional arrangements that specifically target the productivity of those experiencing mental ill health may prove challenging. These findings are particularly important in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic due to changes in work arrangements and workplaces (e.g., working from home while trying to balance work with home and care responsibilities, hybrid working arrangements, and ensuring workplaces have COVID-19-secure measures in place). This work will be of particular interest to employers and decision makers looking to improve worker productivity.

Most literature examined either depression or anxiety or both, the most common mental disorders. Few studies examined mental disorders such as ADHD, bipolar disorder and eating disorders, and no studies examined schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, personality disorder or suicidal/self-harm behaviour. More work is needed on these mental disorders, which, although less prevalent and thus less studied, are potentially more work disabling (despite already low employment rates for individuals with these conditions) [77, 78]. Other research suggests there are important gender differences [25, 28]. For example, Bubonya et al. found that increased job control can help reduce absenteeism for women with good mental health, though not for women in poor mental health [25]. Banerjee et al. found that the impact of poor mental health on the likelihood of being employed and in the labour force is higher for men [28]. Future research should ensure that gender differences, as well as other differences (e.g., age, industry, job conditions), are examined to ensure tailored polices are developed and implemented.

There is also a need to better understand the extent to which mental illness decreases productivity at work and the mechanisms through which this occurs, as this could help inform the role of employment policy and practices to minimise presenteeism [25]. Some research suggests that conducive working conditions, such as part-time employment and having autonomy over work tasks, can help mitigate the negative impact of mental health on presenteeism [76]. Alongside this, it is important to learn more about the dynamics of the relationship between mental illness and worker productivity to understand the trade-offs between presenteeism and absenteeism [25]. For example, it would be helpful to understand whether policies that incentivise workers with mental ill health to take time off improve overall productivity by reducing presenteeism. None of the studies in this review explored this trade-off. Finally, more rigorous research on this topic would help achieve a better understanding of the overall economic impact of mental disorders.

This review is not without limitations. It only included studies obtained from a few select databases and did not include grey literature, and only one reviewer screened the titles and abstracts (though the purpose was not to undertake a systematic review); however, it examined papers and reports from select websites of interest. Furthermore, this review only focused on the relationship between mental health and lost productivity. Although lost productivity is an important labour market outcome, there are other outcomes that mental health can impact such as labour force participation, wages/earnings, and part-time versus full time employment. Finally, this review only included studies published in English and therefore may have missed other relevant studies. Nonetheless, this review has several strengths. It provides an updated review on this topic, thus addressing a critical gap in the literature, and examined the type of data and databases employed, the methods used, and the existing gaps in the literature, thus providing a more comprehensive overview of the research done to date.

Conclusion

This review found clear evidence that poor mental health, typically measured as depression and/or anxiety, was associated with lost productivity, i.e., increased absenteeism and presenteeism. Most studies used survey and administrative data and regression analysis. Few studies employed longitudinal data, and most studies that used cross-sectional data did not account for endogeneity. Despite consistent findings across studies, more high-quality studies are needed on this topic, namely those that account for endogeneity and unobserved heterogeneity. Furthermore, more work is needed to understand the extent to which mental illness decreases productivity at work and the mechanisms through which this occurs, as well as a better understanding of the dynamics of the relationship between mental illness and worker productivity to understand the trade-offs between presenteeism and absenteeism. For example, future research should seek to understand how working conditions and work arrangements as well as workplace policies (e.g., vacation time and leaves of absence) impact presenteeism.