Abstract

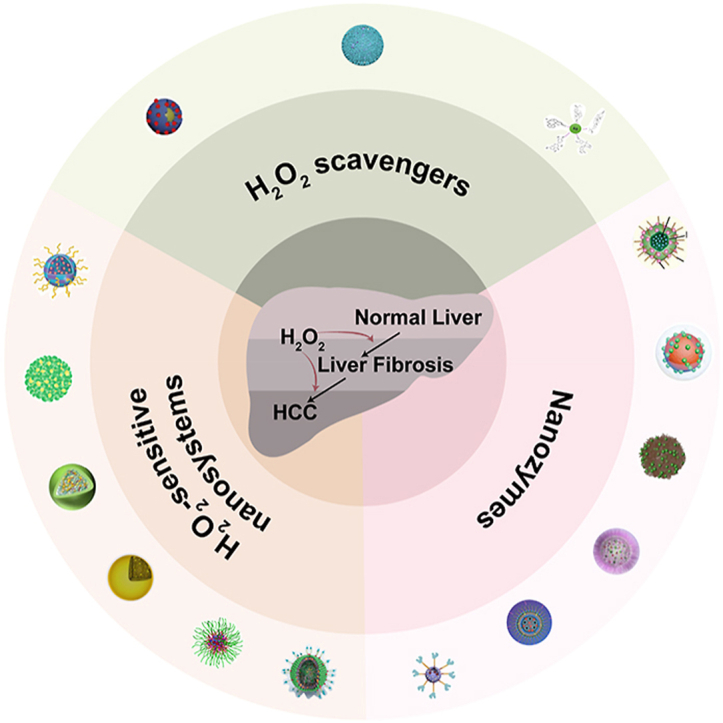

Liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have been worldwide threats nowadays. Liver fibrosis is reversible in early stages but will develop precancerosis of HCC in cirrhotic stage. In pathological liver, excessive H2O2 is generated and accumulated, which impacts the functionality of hepatocytes, Kupffer cells (KCs) and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), leading to genesis of fibrosis and HCC. H2O2 accumulation is associated with overproduction of superoxide anion (O2•−) and abolished antioxidant enzyme systems. Plenty of therapeutics focused on H2O2 have shown satisfactory effects against liver fibrosis or HCC in different ways. This review summarized the reasons of liver H2O2 accumulation, and the role of H2O2 in genesis of liver fibrosis and HCC. Additionally, nanotherapeutics targeting H2O2 were summarized for further consideration of antifibrotic or antitumor therapy.

Keywords: Liver fibrosis, Hepatocarcinogenesis, Nanotherapeutics, H2O2 accumulation, Oxidative stress

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Liver fibrosis and HCC are closely related because ROS induced liver damage and inflammation, especially over-cumulated H2O2.

-

•

Excess H2O2 diffusion in pathological liver was due to increased metabolic rate and diminished cellular antioxidant systems.

-

•

Freely diffused H2O2 damaged liver-specific cells, thereby leading to fibrogenesis and hepatocarcinogenesis.

-

•

Nanotherapeutics targeting H2O2 are summarized for treatment of liver fibrosis and HCC, and also challenges are proposed.

1. Introduction

Liver fibrosis has a high incidence and is usually happened with high fat diet, alcohol abuse, hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection [1]. Most hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) are developed in the context of chronic inflammation induced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis [2]. Generally, liver fibrosis is gradual and reversible, but it will develop into irreversible cirrhosis [3], HCC and liver failure [4] without effective treatments. Liver fibrosis is associated with improved hepatic precancerous risk, and is regarded as a key factor to drive HCC immune escape [5]. Liver fibrosis presents hepatocytes injury, hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) activation, macrophage polarization and extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation [6,7]. Chronic damage and inflammation in liver stimulate the precancerosis of HCC by disrupting cellular copying machinery or altering paracrine signaling [8]. ECM molecules, including collagen, fibronectin and laminin, can interact with HCC and stimulate tumor migration [9,10]. Besides, liver fibrosis is reported to elevate level of immune checkpoint molecules and promote hepatocarcinogenesis through reprogramming HCC cells and regulating immunosuppression [5] (see Table 1, Table 2).

Table 1.

Different nanotherapeutic systems for liver diseases treatment.

| Treatments | Nanoparticles | Applications | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanozymes | Prussian blue | Incorporated with MSCs as a ROS scavenger to help MSCs survive in high oxidative stress environment. | [141] |

| CeO2 | Hepatoprotective activity by reducing ROS level and attenuating inflammatory response. | [143] | |

| MnO2 | Mn4+ receives electrons transferred from bacteria and catalyze H2O2 decomposition to prevent the accumulation of lactic acid. | [154] | |

| Mn3O4 | Eliminating nearly 75% O2•− and H2O2. | [156] | |

| MoS2 | Attenuating electron transfer in cytochrome c/H2O2 to ameliorate antioxidant defense system. | [175] | |

| H2O2scavengers | DATS | Generating H2S to increase intracellular GSH and suppress oxidative stress in mitochondria. | [188] |

| NAC | Precursor of GSH to prevent Fe3O4 NPs-induced cell injury. | [192] | |

| GSH | GSH with thiol-reduced form can efficiently react with ROS to form GSSH. | [198] | |

| H2O2-sensitive nanosystems | PBEM-co-DPA | ROS and pH dual-sensitive block polymer for polydatin responsively release. | [15] |

| Diselenide bonds | ROS-responsive degradation to release TNF-α siRNA. | [193] | |

| POC | H2O2 oxidate peroxalate esters in POC | [194] | |

| RABA | Conjugating atRA and boronic acid for H2O2 and other ROS species scavenging. | [195] |

Table 2.

Nanotherapeutics for HCC treatment.

| Classifications | Nanosystems | Applications | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanozymes | Porous PB loaded with sorafenib | PB catalyzed H2O2 into O2 to release tumor hypoxia and exhibited good photothermal effect. | [138] |

| Hollow PB nanocage loaded with MCT4 siRNAs and LAP | LAP induced H2O2 production and combined with PB to inhibit tumor through Fenton reaction. | [142] | |

| CeO2 NPs | CeO2 NPs selectively targeted hepatic tumor and induced excess ROS degradation, | [147] | |

| PEGylated Mn2O3 NPs | Achieved effective imaging of liver metastatic by T1-contrast enhancement in tumor and T2-shortening in background. | [159] | |

| Verteporfin loaded MnO2 nanocomposites | Mn2+ assisted reduction of energy gap between Verteporfin and triplet O2, and generated O2 for PDT. | [160] | |

| Fe-HMON-Tf loaded with DOX | DOX self-generated H2O2 and enhanced Fe2+/Fe3+ Fenton reaction. | [164] | |

| Fe-TCPP MOFs with hypoxic prodrug TPZ | TCPP PDT exhausted O2 generated by Fe3+ and triggered activation of TPZ. | [173] | |

| H2O2scavengers | Rutin-loaded PLGA NPs | Rutin increased levels of antioxidant enzymes and downregulated proinflammatory cytokines in DEN-induced HCC. | [183] |

| fluorinated chitosan assembled with TCPP-conjugated CAT | CAT catalyzed O2 generation helped to improve SDT therapeutic efficacy of TCPP. | [186] | |

| Sorafenib-CAT-PLGA microspheres | CAT can improve tumor hypoxic micro-environment and enhance the function of sorafenib. | [187] | |

| H2O2-sensitive nanosystems | ROS-responsive Gal-SLP for sorafenib and shUSP22 | Sorafenib worked as an ROS inducer and triggered shUSP22 release to inhibit HCC glycolysis. | [196] |

| Solid lipid microparticle for GSH oral administration | GSH-loaded NPs showed ROS scavenging activity in the presence of H2O2. | [198] | |

| PEG-b-PBEMA integrated PA micelle | PA upregulate H2O2 and amplified oxidation damage against tumor cells. | [197] |

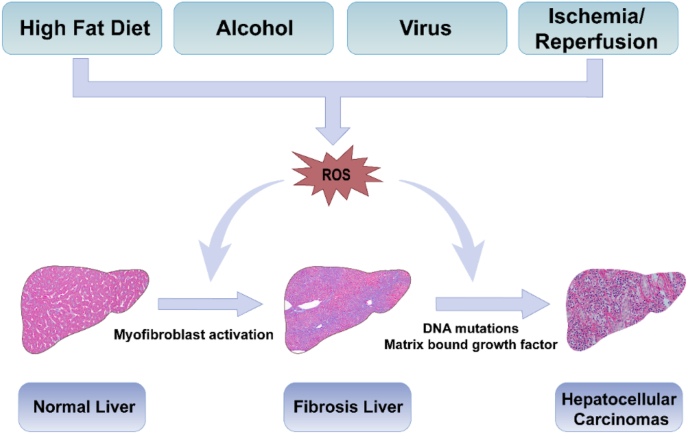

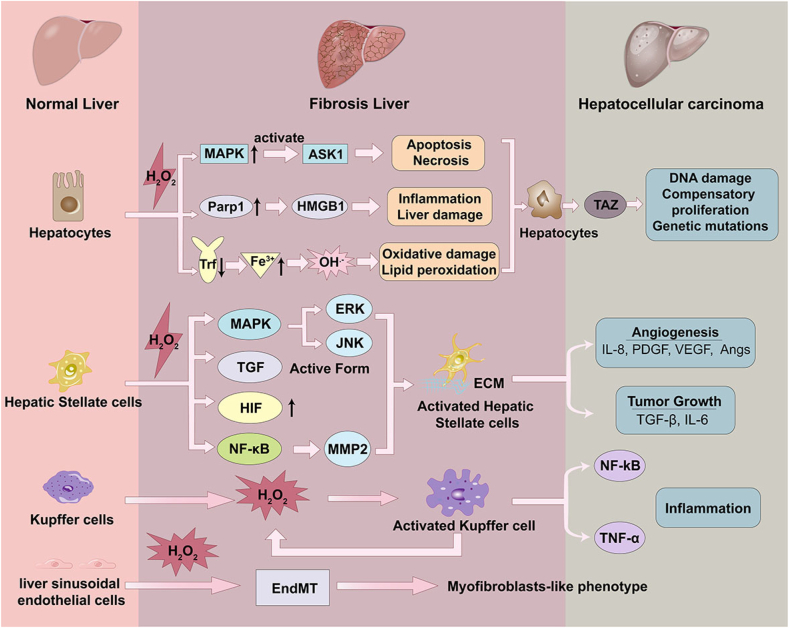

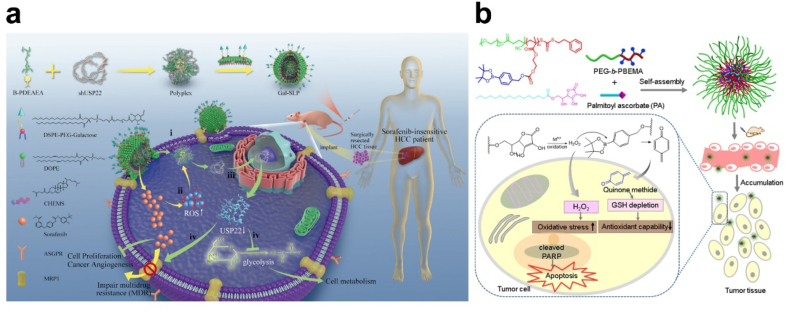

Among various factors that cause liver fibrogenesis and HCC, reactive oxygen species (ROS) have attached much attentions in last decades, including superoxide anion (O2•−), hydroxyl radical (OH•), hydroxyl ion (OH−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), singlet oxygen (1O2), and ozone (O3) [[11], [12], [13]]. Enhanced levels or accelerated generation of ROS has been demonstrated in the plasma of patients with liver disease as well as animal models [14]. The elevated levels of ROS served as an intracellular signaling mediator which significantly promotes HSC activation and ECM synthesis during liver injuries (Fig. 1) [15]. Besides, ROS activated oncogenic pathways like protein kinase B (Akt), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), (hypoxia-inducible factor) HIF, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), microtubule-associated protein kinase (MAPK) and promoted cellular DNA mutations, which were significant pathways that lead to hepatocarcinogenesis [16].

Fig. 1.

Scheme of pathological changes of normal liver to the fibrosis owing to ROS stimuli. As illustrated above, high fat diet, alcohol, virus, drugs, ischemia-reperfusion injury and other harmful substances make the hepatic tissues vulnerable to ROS related oxidative stress, which will trigger liver injury and lead to liver fibrosis, and further induce precancerosis of HCC.

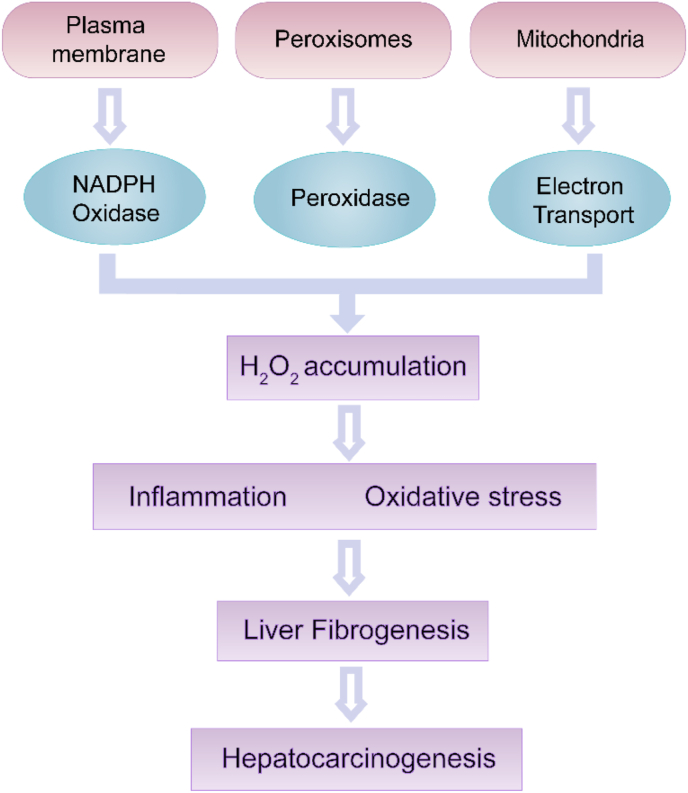

Most kinds of ROS are extremely unstable with their high reactivity, which limits ROS damage at a single cell scale [17]. The half -life period and effective distance of different ROS in cells are: O2•- (1–4 μs, 30 nm); 1O2 (3 μs, 100 nm); HO• (1 μs, 1 nm); H2O2 (1 ms, 1 μm) [18]. H2O2 is a kind of stable ROS and can freely diffuse into the interstitial areas surrounding cell. As a result, diffused H2O2 causes damage to intracellular macromolecules due to its lacking ionic charge. H2O2 is the most abundant ROS species due to its high chemical stability [19]. In the liver, O2•− and H2O2 are continuously generated in various physiological processes [20,21]. It is notable that during respiring process, many spontaneous and enzymatically catalyzed reactions can overproduce O2•− as an intermediate, including mitochondrial respiration, cytosol/plasma membranes-associated NADPH oxidases (NOX), xanthine oxidase, and cytochrome [22,23]. The intermediate O2•− is unstable and is rapidly converted into H2O2 by superoxide dismutase (SOD), resulting in permeation of H2O2 in the liver (Fig. 2). Therefore, excessive H2O2 should be responsible for the oxidative stress in liver tissues.

Fig. 2.

Role of H2O2 in liver fibrosis. Endogenous H2O2 sources include NADPH oxidases, peroxidase and the mitochondria electron transport. The excessive H2O2 accumulation leads to oxidative stress and oxidative damage of biomolecules, eventually induces the fibrosis and HCC.

Nanotherapeutics have many advantages, such as more precise diagnosis, improved targeting efficiency, fewer side effects, and enhanced therapeutic monitoring [24]. Liver characteristics can be utilized to develop nanotherapeutics due to specific enrichment of nanoparticles (NPs) [25]. And nanotherapeutics targeting H2O2 have been proved to be effective in both anti-fibrosis therapy and HCC treatment [26,27]. It's necessary to discuss the pathogenicity mechanism of H2O2 in liver fibrosis/HCC, and develop appropriate treatments for medical staff. In this review, we summarized recent findings relevant to the association among H2O2 accumulation, liver fibrosis and consequent hepatocarcinogenesis. Meanwhile, we depicted typical nanotherapeutics that attenuated liver fibrosis and HCC through downregulating oxidative stress or H2O2 conversion. Targeting oxidative stress with these compounds will be a promising strategy in liver fibrosis and HCC treatment.

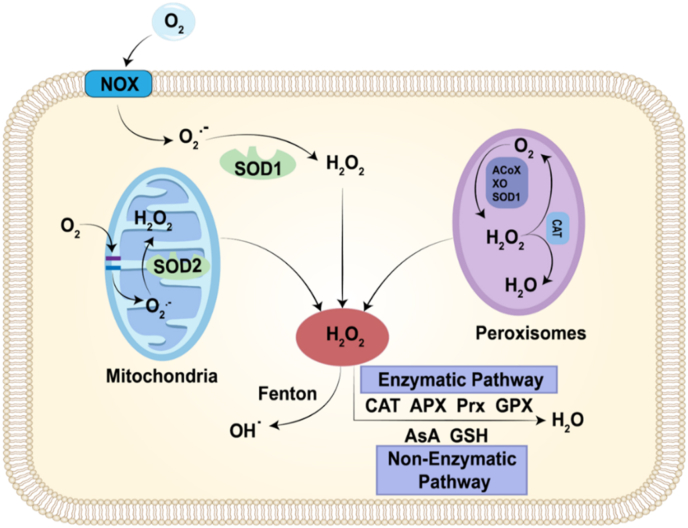

2. Accumulation of H2O2 in liver

Accumulation of H2O2 in liver has been frequently reported in last decades [19,28], which is mainly related to two aspects: increased H2O2 generation and decreased H2O2 elimination. In most conditions, H2O2 is generated from O2•− in mitochondrial electron transport chain, and is cleared by pathways involving antioxidant enzyme systems, such as catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), glutathione peroxidase (GPX) and peroxiredoxins (PRDXs) [22,23]. In acute or chronic liver diseases, metabolism of H2O2 is out-of-balance with liver metabolic remodeling or CAT poisoning (Fig. 3) [29,30].

Fig. 3.

Different routes of H2O2 production and scavenging. The major sources of H2O2 are the NOXs and the mitochondrial respiratory chain, as well as a considerable number of oxidases in peroxisome. H2O2 is cleared by pathways involving antioxidant enzyme systems, such as CAT, APX, PRX and GPX. In non-enzymatic pathway, H2O2 is scavenged by ascorbate (AsA), glutathione (GSH). The generated H2O2 can further convert to OH• via Fenton reaction.

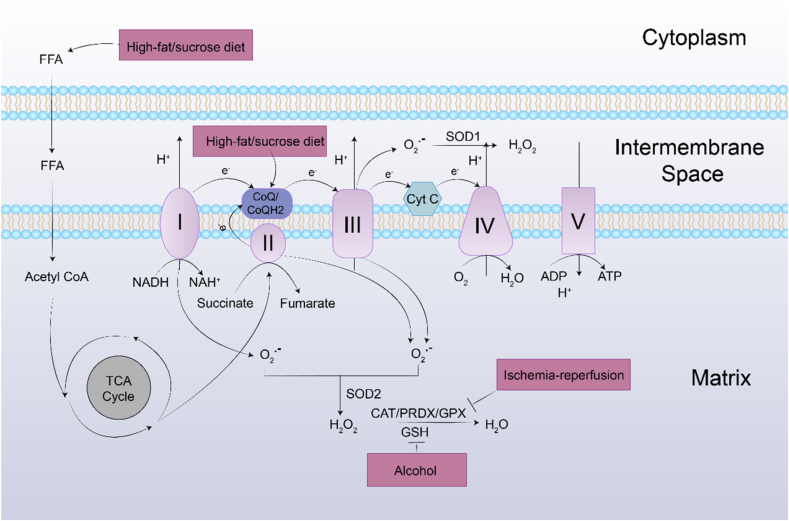

2.1. Increased H2O2 generation

As the major metabolic organ, liver controls macronutrient metabolism [31], lipid homeostasis [32], and ethanol/drug elimination [33], which require amounts of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to keep normal function. Mitochondria, as the powerhouse of cells with respiratory chain, is the primary intracellular sites of oxygen consumption as well as the major source of ROS [34,35]. In mitochondria aerobic respiration, electrons flow along the respiratory chain and eventually culminate at complex IV, in which the molecular oxygen is reduced into water. As described in Fig. 4, superoxide is predominantly generated at complex I and complex III of the cytochrome chain during the process [36]. At first, most electrons were safely reacted with protons and oxygen molecules to form water at complex IV of the respiratory chain. The other electrons didn't react directly with oxygen at complex I and complex III, and were leaked from the respiratory chain to form O2•−, which directly leaded to the formation of H2O2 [37].

Fig. 4.

Mitochondria-derived ROS generation and their elimination by the antioxidant system. O2•− is generated predominantly at complex I, III of the respiratory chain. O2•− is converted to H2O2 by two dismutases including SOD2 in mitochondrial matrix and SOD1 in mitochondrial intermembrane space. Under normal physiological conditions, the generated H2O2 is then eliminated by CAT, and PRDXs, GPXs. During the process of liver fibrosis, the harmful stimuli alter the balance between generation and scavenging of H2O2 due to high H2O2 production and low antioxidant capacity of mitochondria. Additionally, excessive free fatty acid can interfere with ETC through promoting the TCA cycle.

Liver fibrosis is usually accompanied with high-fat/sucrose diet [38,39], alcohol abuse [40], or ischemia-reperfusion injury (I/R injury) [41], resulting in overproduced H2O2 in liver. High-fat/sucrose diet decreases the reduced form of coenzyme Q (ubiquinol, CoQH2), which is easy to be oxidized into ubiquinone (CoQ) or ubisemiquinone. While electrons are reversely transported from CoQH2 to complex I for nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) formation when CoQ pool is significantly reduced [42]. And a high NADH/NAD + ratio is responsible for the O2•− production with direct formation of H2O2 [42]. Leverve et al. demonstrated that high-fat (HF) diet led to liver mitochondrial alterations. Quinone pools (CoQ9 and CoQ10) of mitochondria was lower and ratio of reduced CoQ9-to-oxidative CoQ9 was higher in HF diet treated rats, which corresponded to lower respiration rate and higher H2O2 production [38]. For high-sucrose diet, levels of reduced CoQ9 and CoQ10 were also significantly lower in mitochondria of sucrose-fed rats [39]. Additionally, high-fat/sucrose diet induces the accumulation of fat in liver and increases circulating free fatty acid. H2O2 is produced by peroxisomes as a byproduct of fatty acid oxidation by acyl-CoA oxidase, which directly transfers electrons to O2 to form O2•− [23].

Alcohol is one of the most abused hepatotoxic species, and alcoholic liver disease (ALD) has been a global heathy problem [43]. In 1992, chronic treatment of ethanol has been reported to significantly increase H2O2 generation by elevating peroxisomal β-oxidation of acyl-CoA compounds [44]. Apart from the toxic intermediate acetaldehyde, H2O2 was considered as a cornerstone for ethanol-mediated liver damage through inducing autophagy and programmed cell death [43]. ROS accumulation, especially H2O2 has been demonstrated to cause major injury during liver ischemia-reperfusion [45]. I/R injury involved interruption and restoration of blood supply, which resulted in acute hypoxia state of tissues [41]. For adaptive responses to acute hypoxia, a superoxide burst was produced with hypoxia activated mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in I/R injury [46]. Hernansanz-Agustín et al. indicated that oxygen depletion could trigger complex I deactivation transition (active/’deactive’ transition), and electrons were reversely transported from CoQH2 to NAD+, which implied high ROS production [47]. Tumor cells were regarded to obtain high metabolic activity and tumor mitochondria handled overproduction of different ROS [48]. To evade oxidative toxicity of oxygen free radicals, SOD was highly expressed in tumor cells to enhance conversion of free radicals into low toxic H2O2, which activated oncogenic and angiogenic pathway and helped cell invasion [22].

2.2. Decreased H2O2 elimination

Mammalian expression of CAT is most abundant in liver, kidney and erythrocytes [49]. CAT is the central enzyme that regulates oxidative stress by catalyzing H2O2 into H2O and oxygen [50]. Decreasing level of CAT suggests the presence of intracellular oxidative stress in liver tissue [51]. CAT expression can be diminished in different conditions. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) is the well-known activator of CAT gene transcription [52], and inhibition of PPARγ can stimulate the downregulation of CAT [53]. Reduced liver CAT activity or decreasing CAT level were reported in murine NASH (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis) models [54]. Dong et al. found that CAT decreased in liver fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride (CCl4). Overexpression of CAT led to a decrease in the secretion of collagen 1 and angiopoietin 1 and inhibited activation of HSC-T6 cells [27]. Walid G. et al. administrated human recombinant TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor α) into rats and observed significant decrease in the CAT [55]. Additionally, due to the active heme center of CAT for H2O2 decomposition, chemicals that can tightly bind with heme iron (NO, CN, H2S) will inhibit the activity of CAT, thus inducing the increasing H2O2 concentration [29,56].

PRDX and GPX are main members of the mitochondrial antioxidant defense system [57]. PRDX3 is an efficient H2O2-eliminating enzyme in mitochondria, which oxidize peroxidatic cysteine (CysP) into –SOH, then formed an intermolecular disulfide bond with a resolving cysteine (CysR) on the second subunit [58]. GPX mediates selenocysteine and H2O2 reaction to form selenol, which is subsequently resolved by two GSH [58]. These antioxidant enzymes are observed to be downregulated in many diseases. Han et al. reported that liver I/R impaired function of NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2), which leading to the decreased level of NADPH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate), decreased activity of GPX, and an increased H2O2 production [59]. Accumulation of bile acids has been proved to cause decreased PRDX3 expression through downregulation of nuclear respiratory factor 2 (Nrf2), and led to the impairment of mitochondrial antioxidant system [60].

GSH is a tripeptide, y-glutamylcysteinyl glycine, which is found in all mammalian tissues and is especially high concentrated in the liver [61]. GSH/GPX system controlled the redox balance in untransformed cells [62]. GSH depletion in liver is highly associated with different hepatopathies. Hepatic cirrhosis with decreased circulating GSH is apparently due to the decreased function of liver, which includes GSH transfer to plasma [63]. Shrestha, N. et al. found that GSH content was significantly depleted in the CCl4 induced liver fibrosis, but it was significantly restored by the treatment of glutamine as a major precursor of GSH synthesis [64]. And alcohol abuse produced amounts of toxic metabolite acetaldehyde in liver, which was reported to bind to GSH and inhibit its H2O2 scavenger function, resulting in aggravating oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation [65]. However, GSH in liver tumors was slightly lower compared with normal tissue and declared no significance [66]. Many researchers even have reported higher GSH level in different human cancers [67]. Tumor cells upregulated GSH synthesis and regeneration to antagonize high-level ROS that were toxic [67]. Furthermore, GSH was regarded as the main contributor to tumor growth, and blocking early synthesis of GSH blunted tumor proliferation [68].

3. Role of H2O2 in liver fibrosis and HCC

H2O2 impacts the functionality of several liver-specific cells, such as hepatocytes, Kupffer cells (KCs) and HSCs, leading to the generation and development of liver fibrosis [19]. Damaged hepatocytes will release fibrogenic mediators to stimulate HSCs activation, and induce the recruitment of leukocytes by inflammatory cells [69]. Activated HSCs also mediate a range of immunoregulatory effects by producing NOX enzymes, ROS, pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [70]. As the liver resident macrophages, KCs are activated under oxidative stress, and activated KCs secreted different cytokines and released ROS, which were important in liver inflammation [71,72]. Additionally, the liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LESCs) are also highly sensitive to oxidative stress delivered via the portal vein (Fig. 5) [71]. In turn, the released ROS from damaged hepatocytes or activated inflammatory cells was able to induce cellular activation, migration or chemotaxis, which have been reported to contribute to liver fibrogenesis [11]. HCC was known as “inflammatory cancer”, which was derived from liver inflammation with ongoing released chemokines and ROS [73]. What's more, in chronic liver diseases, prolonged ROS accumulation oxidized DNA bases and cellular membrane lipid, which participates in hepatocarcinogenesis [74].

Fig. 5.

Illustration of the effect of accumulated H2O2 on hepatocyte, HSCs, KCs, and LSECs during fibrogenesis. During the continuous H2O2 stimuli, the functionality of several liver-specific cells, such as hepatocytes, KCs and HSCs was impacted leading to the generation and development of liver fibrosis. The excess H2O2 induces apoptosis and necrosis of hepatocytes, promotes HSCs activation, exacerbates the inflammatory responses involved the activation of resident KCs, and induces the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) process of LSECs, which contributing to liver fibrosis and eventually inducing HCC.

3.1. Damage of hepatocytes

Hepatocytes involve cellular metabolism, iron homeostasis and detoxification process [75]. H2O2 can increase MAPK activity through oxidizing cysteine residues in protein tyrosine phosphatases, releasing and activating its binding partner MAPKKK5 (or apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1, ASK1). Thereby it stimulated the cellular matrix genes expression and inflammatory molecules release, and promoted cellular apoptosis and necrosis [76,77]. Besides, in response to the oxidative stress caused by excessive H2O2, hepatocytes highly express poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (Parp1) and mediate translocation of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) from nuclear to cytoplasm, which triggers inflammatory response and liver damage [78]. In addition, H2O2 at non-toxic levels was reported to be responsible for ethanol induced hepatic damage rather than acetaldehyde through autophagy [43]. Mueller et al. concluded that ethanol induced upregulation of NOX4 and CYP2E1 (cytochrome P450 2E1) to overproduce H2O2 during ethanol metabolism, thus activated hepatocyte autophagy without the involvement of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin).

What's more, liver is the conductor of systemic iron balance. Under normal conditions, ferric iron binds to the transferrin (Trf) and forms a nontoxic complex for iron delivery. But in liver fibrosis or liver cirrhosis, reduced Trf levels and iron overloaded have been reported, and higher amounts of non-bound iron are transported into liver for clearance [79]. Presence of accumulated H2O2 and non-bound iron in liver leads to the production of dangerous OH• through Fenton reaction [80]. OH• is highly reactive for biomacromolecules, such as DNA, protein and lipid, leading to oxidative damage or lipid peroxidation [81]. Then, the decrease in reduced GSH level and GPX4 activity trigger the destruction of the cell membrane integrity. Peroxidized lipid couldn't be removed through the GSH/GPX system and finally induced ferroptosis of hepatocytes [82,83]. In addition, ROS increased the expression and synthesis of cytokines, including interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-8, and TNF-α, which caused apoptosis and necrosis of hepatocytes and relating to liver fibrosis [84].

As the by-product of hepatocytes, H2O2 could diffuse into nuclear and damage DNA in hepatocytes [74]. Once damaged, hepatocytes were initiated to the compensatory proliferation, and accumulated genetic mutations for carcinogenesis [85]. The formation of oxidative DNA marker, 8-Oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHDG), was linked to epigenetic instability in HCC [86]. Wang et al. found that hepatocytes expressed 8-OHDG was increased during NASH diet due to NOX2-mediated DNA oxidative damage. NOX2 was encoded by cybb gene, and was regulated by TAZ (transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif), a transcriptional regulator that promote NASH to HCC [87]. What's more, Seo et al. found that alcohol damaged hepatocytes could excrete 8-OHDG enriched extracellular vesicles (EVs) and transfer them into HCC cells. 8-OHDG-enriched EVs subsequently activated oncogenic pathways, such as JNK, STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3), BCL-2 (B cell lymphoma-2), and TAZ, thereby inducing hepatocarcinogenesis [88].

3.2. Inducing HSCs activation

H2O2 is regarded to induce liver fibrosis via activating HSCs directly or indirectly. H2O2 accumulation promotes HSCs activation and trans-differentiation into myofibroblast through regulating pro-angiogenic and pro-fibrogenic responses [89]. Mounting evidences pointed to a link between excessive H2O2 accumulation and HSC activation. For example, deficiency of enzymes that involved ROS generation catalyzing in mice decreased HSC activation and fibrogenesis [[90], [91], [92]]. Novo et al. showed that all effective stimuli for profibrogenic human HSC and myofibroblast-like cells (MFs) require intracellular generation of ROS as a common critical step for trigger chemotaxis through redox-sensitive activation of extracellular regulated JNK1/2 and ERK1/2 [11]. Inhibition of phosphorylated JNK and mitochondria interaction, or reduced mitochondrial ROS production could reduce HSC activation and liver injury [93].

H2O2 also displays an important role in fibrosis in conjunction with the TGF-β1 (transforming growth factor-beta 1) signaling system [94]. TGF-β1 has been reported to present as a latent complex and deposited in the hepatic sinusoid at high concentration [95]. H2O2 can convert latent TGF-β1 to the active form and promote activation of HSCs, and consequently triggered fibrogenesis [96]. Furthermore, H2O2 is capable of modifying different cellular pathways through DNA binding sites dysfunction of redox-sensitive transcription factors or by cysteine residues oxidation on these molecules, such as hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α) and nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-ĸB) [97]. H2O2 generated from mitochondria can mediate stabilization and decrease degradation of HIF-1α, which has been implicated in the development of hepatic fibrosis and immune response [98]. Furthermore, due to the hypoxia feature of fibrotic tissues, H2O2 was also an important factor released by hypoxic hepatocyte to regulate HSCs expression of matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) through cell-cell interaction. MMP-2 produced by HSCs is involved in ECM remodeling and degrades collagen IV around HSCs, therefore promoting the activation, proliferation, and migration of HSCs [99].

Activated HSCs was a major kind component in HCC and secreted ECM, growth factors and cytokines for HCC progression [100]. HSCs were converted into cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), which implicated the chemotherapy resistance, angiogenesis, and stemness maintenance of HCC [101]. Besides, activated HSCs also mediated immunosuppression in liver and promoted HCC progression [102]. Liu et al. elucidated the interaction between HSCs and HCC through intrahepatic microbiota disturbances. They found higher S.maltophilia enrichment in cirrhosis patients, and demonstrated that S.maltophilia infection provoked senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) activation of HSCs via TLR4/NF-κb pathway [103]. Activation of SASP in HSCs has been correlated with HCC development via excretion of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, matrix-remodeling factors, and growth factors [104].

3.3. Inflammatory regulation

H2O2 is not only a cellular key reactive oxygen species but also an important inflammatory cofactor [105]. Increased level of H2O2 can promote inflammatory responses through activation of several pro-inflammatory signal pathways, typically MAPK, NF-κB and Janus kinase (JAK)-STAT signal pathways, which lead to indirect enhancement of liver fibrosis [106,107]. ROS is related to the increased production of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). DMAPs are a kind of signaling molecules, which involved in inflammatory reactions, homeostasis restoration, and induced cofactors that promote liver fibrosis, ALD or NASH [89,108]. Upon liver damage, oxidant stress highly induces osteopontin, which is a matrix-bound protein emerged as a key DAMP in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis by increasing HMGB1 and collagen type I expression in HSCs [109].

Innate immune responses involved the activation of resident KCs as well as the recruitment of leukocytes to the liver [110]. H2O2 is reported to activate KCs, and activated KCs are well-known sources of hepatic ROS. This process leads to a vicious cycle of ultimately fibrosis [111,112]. Besides, recent studies have demonstrated that a fraction of LSECs may contribute to liver fibrosis directly via endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process, and ROS plays a key role in EMT [113]. Aberrant activation of EMT has been demonstrated to promote hypoxia, glycolysis, and subsequent fibrogenesis in different organs, including liver and kidney [114,115]. ROS production in endothelial cells has been shown to promote tissue fibrosis likely via EMT process, which pivoting LESCs into a myofibroblasts-like phenotype [116]. Luo et al. showed that H2O2 could disrupt mitochondrial function through evaluation the protein level of NOX2, and lead to defenestration in LSECs. Silence of NOX2 gene could rescue mitochondrial function and subsequently maintain LSECs fenestrae [117].

Liver inflammation was shown to be critical in chronic hepatitis associated hepatocarcinogenesis, and KCs were reported to be the HCC-specific tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [118]. Activation of KCs led to the release of different inflammatory cytokines and modulated HCC progression. In early phases of chronic inflammation, KCs were polarized into M1 phenotype and release TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β and iNOS (inducible nitric oxide synthase) [119]. During HCC progression, KCs were dynamically switched from M1 phenotype to TAMs (M2 phenotype) with IL-6 stimulation [120]. Kong et al. found that the development of HCC was promoted by macrophages secreted IL-6, which in turn enlisted leukocytes. IL-6-deficient mice showed lower infiltrated inflammatory cells in liver, and HCC tumor was much smaller in IL-6-knock out mice [118].

3.4. Tumor progression

ROS induced hepatic injury, including peroxidation of protein, DNA and lipid, inflammatory reaction, tended to initiate tumorigenesis. Tumor cells obtained high level production of superoxide with major sources of NOXs [121], mitochondria [122], and peroxisome [123], which was rapidly converted to H2O2 via SOD. H2O2 accumulation in liver can induce chromosomal mutations and finally malignant transformation of proliferating hepatocytes [124]. Research has found that H2O2 could stimulate angiogenesis and mediate migration and invasion capacity in HCC cells via AKT activation [125,126]. Over 90% of HCC cased arise in chronic liver disease, which was the strongest risk factor for HCC [127]. Activated HSC was the key cell involved in chronic liver damage, which undergone phenotypic changes, synthesized extracellular matrix components and stimulated the migration of endothelial cells [128]. Previous findings showed that HCC almost always occurred with different degrees of fibrosis or hepatic inflammation [124].

Furthermore, H2O2 could regulate immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) and assist tumor immune escape. Excess ROS in TME was reported to reduce T cell activity through inhibiting mTOR pathway, which was important for T cell activation and proliferation [129]. It has been reported that H2O2 activated HSCs could mediate re-differentiation of CD14+HLA-DR-/low monocyte into myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in liver [130]. MDSCs were universal negative regulators of adaptive immunity and showed immunosuppressive activity to promote HCC proliferation [131]. Zhao et al. reported that HSCs increased levels of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and MDSCs in HCC microenvironment, and assisted the immune evasion of hepatoma cells [132].

4. Nanotherapeutics strategies

Many different pharmacotherapeutic strategies aimed at reversal or prevention of fibrosis/cirrhosis progression and induction of HCC ablation have been considered, but the effect of these therapies is not satisfactory [77]. Due to the complex pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis and HCC, specific effective drugs in clinical practice were still lacking [133]. Given the importance of H2O2 in liver fibrosis and HCC, oxidative stress targeted therapy has great potential in liver fibrosis and HCC. Besides, due to the superiority that nanoparticles circulated in blood was mainly sequestered in liver, nanotherapeutics aimed at liver oxidative stress were effective in the treatment of liver diseases. Hence, the application of multifunctional nanotherapeutics involving H2O2 scavenging and efficient delivery of different cargos have been an evolved area of interest [134].

4.1. Nanozymes

Nanozyme is a kind of nanomaterials with enzyme-like capability, and has been included in the Encyclopedia of China and the textbook of enzyme engineering [135]. Nanozyme with catalytic activities, such as peroxidase (POD), CAT, SOD, and GPX has been demonstrated to ameliorate liver oxidative stress and fibrosis [136,137] and produce synergistic effects for HCC treatment [138].

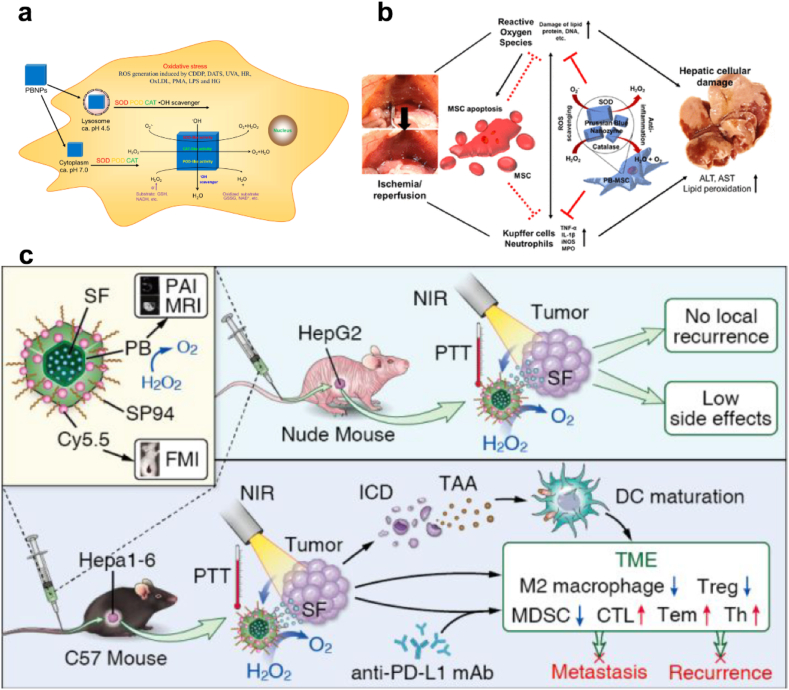

4.1.1. Prussian blue (PB)

PB has been commonly used as a biocompatible contrast agent for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an antidote for thallium in 2010 [139]. Zhang et al., reported that PB NPs obtained multienzyme-like activity, including POD, CAT and SOD (Fig. 6a) [136]. Particularly, PB could efficiently scavenge O2•− and H2O2 without generation of the toxic byproduct OH•, showing that PB is of good biocompatibility for in vivo applications. Due to the proven biocompatibility and multifunctional nanozyme activity of PB, Sahu et al. incorporated PB nanozyme into mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to augment the function of MSCs for liver I/R injury alleviation. MSCs cell therapy is promising in protecting organs from I/R injury by mitochondrial transfer, macrovesicles and the paracrine effect [140]. But the harsh environment of I/R injury site limited the survival and engraftment of MSCs and impeded the therapeutic effect. Corporation of PB as a ROS scavenger didn't affect the stemness and differentiation potential of MSCs, and augmented the paracrine effect and anti-inflammatory properties of the MSCs (Fig. 6b) [141].

Fig. 6.

(a) Illustration of the POD-like activity of PB NPs. Adapted with permission [136]. Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. (b) PB impregnated mesenchymal stem cells for hepatic I/R injury alleviation. Adapted with permission [141]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. (c) Scheme illustrating the SP94-PB-SF-Cy5.5 NPs treatment regimen for HCC [138]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society.

The CAT-like activity of PB is also used to relieve tumor hypoxia by decomposing excess H2O2 in TME to produce O2. Zhou et al., designed HCC-targeted PB NPs loaded with sorafenib representing a valuable treatment option for HCC (Fig. 6c). The CAT-like ability and photothermal effect of PB-induced O2 production, which greatly reprogram the hypoxic and immunosuppressive TME, alleviating tumor hypoxia and reducing M2 macrophages [138]. Wang et al. utilized β-lapachone (LAP) to initiate high-level H2O2 production and transferred MCT4 siRNA to mediate lactate blockade, therefore increasing tumor pH and triggering PB-mediated Fenton reaction for tumor treatment [142].

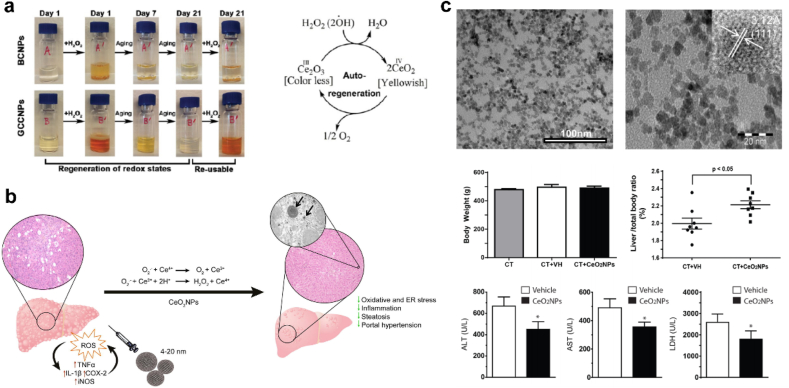

4.1.2. Cerium oxide (CeO2)

CeO2 has been proven to be an effective H2O2 scavenger and displayed hepatoprotective activity against liver fibrosis [143]. The catalytic properties of CeO2 mainly depend on the formation of oxygen vacancies and electron transition between the oxidation state (Ce4+) and reduction state (Ce3+) [144]. Mitra et al. reported an aqueous-soluble nanoceria (GCCNP) with dominated Ce3+ that can scavenge the ROS, such as H2O2 and OH•, and inhibit neovascularization formation (Fig. 7a) [145]. Besides, Oró et al. demonstrated that liver was the major target of CeO2 (4 nm) NPs in CCl4 fibrotic rats (Fig. 7b). After intravenous injection for 8 weeks, CeO2 NPs were mainly located in the liver, which were intended to be used as a drug delivery vehicle [143]. CeO2 NPs with antioxidant enzyme-mimetic activities, such as SOD activity, CAT activity, POD activity, have also been a new therapeutic tool in HCC [146]. Fernandez-Varo et al. consider CeO2 NPs could be an NP-based therapy platform in HCC. The authors found that CeO2 NPs can be adsorbed in human hepatocyte cancer cells and induce ROS degradation and tumor recession [147].

Fig. 7.

(a) Free radical scavenging activity and autoregenerative properties of GCCNPs. Adapted with permission [145]. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. (b) Scheme illustrating the CeO2NPs administration protecting against chronic liver injury by reducing liver steatosis and portal hypertension and markedly attenuating the intensity of the inflammatory response. Adapted with permission [143]. Copyright 2016, Elsevier. (c) CeO2NPs treatment increased liver regeneration and cell proliferation. Adapted with permission [148]. Copyright 2019, Springer Nature.

Evidences have shown a significant therapeutic potential of CeO2 NPs in driving liver regeneration [148], reducing lipid peroxidation [149] and liver steatosis [143] in different experimental conditions. In 2019, Cordoba-Jover et al. firstly found the effects of CeO2 on liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy (PHx) and acetaminophen (APAP)-induced liver injury in rats (Fig. 7c) [148]. Malondialdehyde (MDA) is the major lipid oxidation product in biological samples. Reduced level of MDA in plasma was detected in CCl4 BALB/c mice treated with CeO2, indicating that lipid peroxidation was reduced after CeO2 treatment [149]. However, very high doses of CeO2 (40 μg/mL) may induce oxidative stress and decrease intracellular GSH in normal cells, therefore inducing cell apoptosis [150]. The application of CeO2 is a double-edged sword, and clinical safety and efficacy studies should be more precisely considered in future works [151].

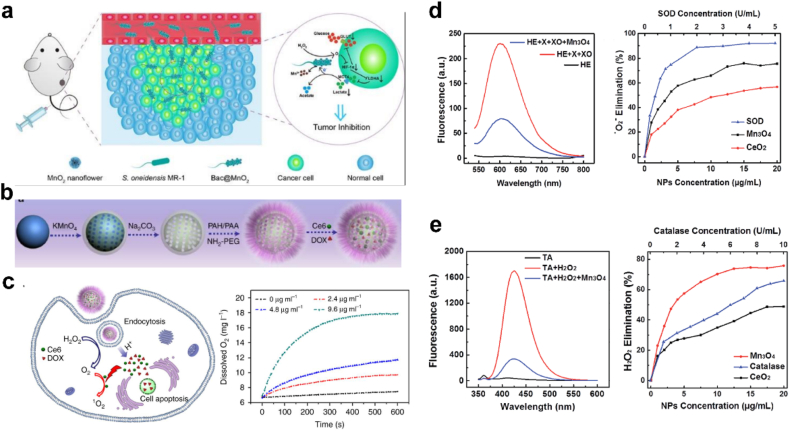

4.1.3. Manganese (Mn)-based nanomaterials

Mn is a necessary nontoxic element involved in physiological metabolism [152]. The multiple oxidation states of Mn (II, III, IV and VII) confers manganese oxide with superior redox capacity and anti-oxidant potential to scavenge ROS [153]. Higher-valent Mn-based nanomaterials, such as MnO2, Mn3O4, have been applied as biodegradable nanozymes to catalyze H2O2 decomposition into O2 (Fig. 8) [[154], [155], [156]]. Chen et al. modified MnO2 nanoflowers on the surface of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 and constructed a biohybrid Bac@MnO2 [154]. The biohybrid could transfer electrons from lactate acid to Mn4+ for respiration in the absence of O2, and meanwhile catalyze H2O2 decomposition. This process synergistically prevented the accumulation of lactic acid. Yao et al. reported Mn3O4 NPs possessed multiple enzyme mimicking activities of SOD and CAT, which could eliminate as much as 75% of O2•− and H2O2 [156].

Fig. 8.

(a) Schematic illustration of tumor targeting of Bac@MnO2 and its tumor inhibition mechanism. Adapted with permission [154]. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH. (b) Step-by-step synthesis of drug loaded hollow MnO2 nanoparticles and (c) pH-responsive drug delivery and oxygen generation in H2O2 solution. Adapted with permission [155]. Copyright 2017, Springer Nature. (d) Mn3O4 scavenging of O2•− compared with CeO2 NPs, SOD and (e) reaction with H2O2 compared with CeO2 NPs, CAT. Adapted with permission [156]. Copyright 2018, The Royal Society of Chemistry.

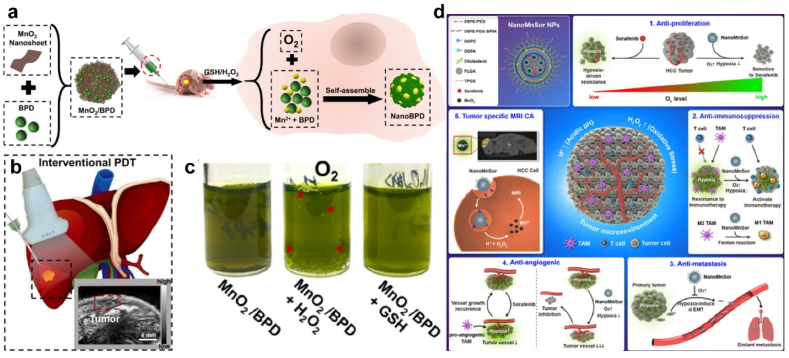

H2O2 with untimely clearance can be converted to OH•, which are extremely reactive and more toxic than other ROS [157]. On the other side, Mn ions (such as Mn3+, Mn4+) can be reduced into lower-valent Mn2+ by intracellular GSH (Mn3+/4+ + GSH → Mn2+ + GSSG) [158]. Mn2+ exhibits the potential for contrast amplification as the relativity could be highly increased after binding with proteins [159]. Wang, Y., et al. developed an innovative MnO2/BPD nanosystem to improve the survival rate of patients with unresectable HCC (Fig. 9a–c). MnO2 was reduced to Mn2+ by high intracellular GSH, and self-assembled with verteporfin (BPD) to produce MnO2/BPD. This process also generated O2 to enhance the effects of photodynamic therapy (PDT) and deplete GSH, which prolonging the life of the ROS and amplified ROS damage [160].

Fig. 9.

(a-c) Illustration of MnO2/BPD synthesis, reduction and self-assembly in vivo. O2 was produced and supported PDT efficiency. Adapted with permission [160]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. (d) Schematic representation of the mechanism by which NanoMnSor can serve as a theranostic anticancer agent. Adapted with permission [161]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society.

Given the crucial role of the hypoxic TME in tumor progression and drug resistance, MnO2 NPs have been developed as nanoscale oxygen delivery systems. Chang et al. report a NanoMnSor nanoparticle drug carrier which could codelivery of MnO2 and sorafenib by synergistically inhibiting the progression of primary HCC (Fig. 9d). The catalytic effect of MnO2 on oxygen generation by H2O2 alleviated tumor hypoxia, and thereby overcoming hypoxia-induced resistance to sorafenib [161]. Mn2+ could mediate Fenton-like reaction with H2O2 and generated toxic OH• (Mn2+ + H2O2 → Mn3+ + OH• + OH-) for anti-tumor therapy, which might enlarge free radical damage toward normal liver tissues [162]. But fortunately, in normal cells or fibrotic liver cells, the level of GSH content is lower compared with tumor cells, and this side effect is negligible with low cytotoxicity on normal cells [162,163]. Even so, it's suggested to restrict the dosage of Mn-based nanomaterials and monitor the hepatic function indexes during the treatment.

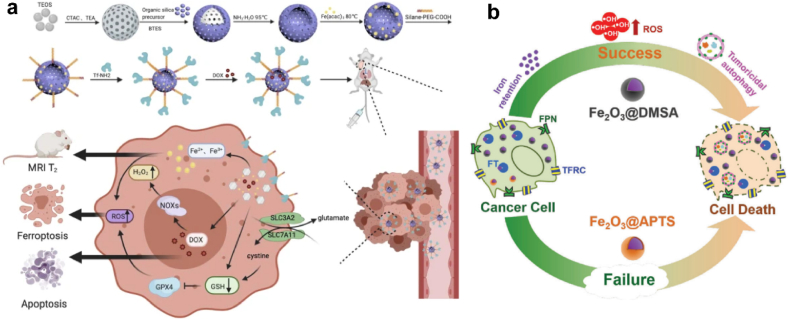

4.1.4. Fe-based nanozymes

Fe-based nanozyme is another commonly used category, and has been widely applied in anti-tumor therapy. Fe-mediated Fenton reaction converted endogenous H2O2 into highly toxic hydroxyl radicals, which were efficient in inhibiting HCC progression [164]. As HCC cells overexpress transferrin receptors, Zhou et al. constructed a tumor-targeting theragnostic nanoplatform by incorporating transferrin with a mesoporous iron framework (Fe-HMON-Tf) to enhance specific HCC targeting. Doxorubicin (DOX) was further loaded in the framework to generate H2O2 in HCC cells, which was converted to OH• via Fe2+/Fe3+ from the Fenton reaction (Fig. 10a) [164]. Xie et al. found that iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) possessed an intrinsic and directed cytostatic efficiency for HCC (Fig. 10b). They found that Fe2O3@DMSA applied as autophagy intervention agents to directly suppress hepatoma with iron-retention-induced sustained ROS production [165].

Fig. 10.

(a) Synthesis and biomedical application of DOX@Fe-HMON-Tf NPs. Adapted with permission [164]. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature. (b) The carboxy‐functional iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe2O3@DMSA) significantly impact on the iron transport system and promotes the retention of intracellular iron, resulting in excessive ROS‐induced tumoricidal autophagy. Adapted with permission [165]. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature.

To further improve the chemodynamic therapy (CDT) efficacy, self-enhancement of H2O2 was applied to amplify tumor death. Li et al. design a Vitamin c (Vc) loaded biodegradable mesoporous magnetic nanocubes (MMNCs) with phasechange materials (PCM). Vc served as an original source of H2O2, and cooperated with MMNCs to mediate Fenton reagent-like activity in an acidic environment [166]. Fan et al. designed a H2O2-generation engineered bacterium and covalently loaded magnetic Fe3O4 NPs to enhance tumor in-situ CDT [167]. Escherichia coli MG1655 was overexpressed with respiratory chain enzyme II (NDH-2), which transferred electrons in respiratory chain to oxygen molecules and generated H2O2 continuously to provide reagent of Fenton reaction.

However, Fe-based nanozymes were not suggested for treatment of liver fibrosis. Firstly, many liver diseases, such as ALD and hereditary hemochromatosis, have been reported to induce iron accumulation in liver and cause iron metabolism disorders [80,168]. Externally administrated iron was mainly stored in liver and aggravated iron overload disorders, leading to cellular ferroptosis, hepatic function damage and biliary excretion limitation [169]. Secondly, Fe-based materials have a risk in catalyzing H2O2 to generate OH• through Fe2+-mediated Fenton reaction, which would result in DNA damage, lipid and protein oxidation and carcinogenesis [29]. Liu et al. explored chronic iron overload induced liver injury through dietary feeding ferrocene [170]. They found that iron overload mainly caused cell damage in liver with iron initiated oxidative stress. Wu et al. reported that iron overload promoted heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) expression and induced liver injury accompanied with fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) upregulation [171]. FGF21 could in turn protect hepatocytes from iron-induced ferroptosis by promoting HO-1 ubiquitination and degradation.

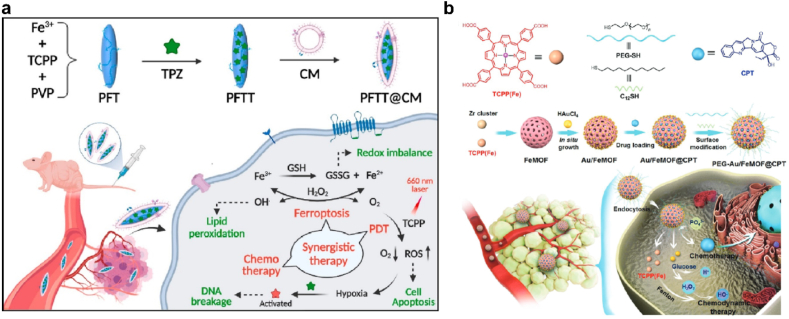

4.1.5. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)

MOFs were porous supramolecular crystal with numerous catalytically active site, and multifunctional modifications further extended their applications [172]. MOFs mimicked catalytic activity of CAT, PRDX and SOD, therefore converting H2O2 into OH• or O2. Pan et al. designed a nanoscale MOF of Fe-meso-tetra(4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin (TCPP) to load hypoxic sensitive tirapazamine (TPZ) (PFTT), which was further coated with tumor cell membrane to evade immune clearance and enhance homologous targeting [173]. PFTT was decomposed in lysosomes and released Fe3+ to catalyze H2O2 into oxygen, which was exhausted by PDT and triggered activation of TPZ for cancer treatment (Fig. 11a). Recently, researchers found that endogenous H2O2 in tumor was not sufficient for highly efficient PDT or CDT. Ding et al. anchored Au NPs on the surface of a Fe-TCPP MOF through in situ growth. Au NPs acted as glucose oxidase to catalyze glucose and elevated cellular H2O2 level for enhanced CDT [174]. As shown in Fig. 11b, porous FeMOFs were loaded with chemotherapeutic camptothecin (CPT) and acted burst release under phosphate ions stimulation. Simultaneously, FeMOF and Au NPs combined a cascade catalytic system, which significantly improved antitumor efficiency.

Fig. 11.

(a) Schematic illustration of the cancer-cell membrane-coated self-assembled nanocomposites for multimodal synergistic breast cancer therapy. Adapted with permission [173]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (b) Schematic illustrating the chemical structures, synthetic route and application of the hybrid nanomedicine PEG-Au/FeMOF@CPT. Adapted with permission [174]. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH.

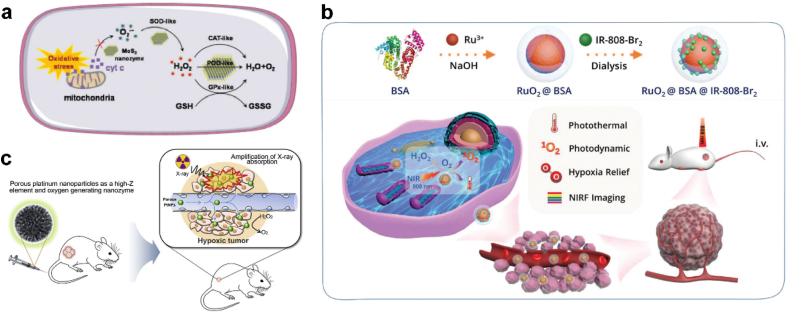

4.1.6. Other nanozymes

Apart from the nanozymes mentioned above, there are some nanomaterials newly discovered to obtain catalytic capability. Zhou et al. demonstrated that molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) nanozymes exhibit activities of four major cellular cascade antioxidant enzymes (including SOD, CAT, POD, and GPX), and play a role as a self-cascade platform for cellular ROS scavenging and hepatic fibrosis therapy (Fig. 12a) [175]. Other CAT-like nanozymes containing rare metal oxide-based nanomaterials, such as iridium (Ir), Ruthenium (Ru) and Platinum (Pt)-based nanozymes, have shown high CAT-like activity, which could immediately convert H2O2 to O2 and alleviate oxidative stress for biomedical applications (Fig. 12b) [[176], [177], [178]].

Fig. 12.

(a) Schematic illustration of the cellular cascade process of MoS2 for ROS scavenging. Adapted with permission [175]. Copyright 2021, The Royal Society of Chemistry. (b) Schematic illustrating the synthetic route and application of multifunctional RuO2@BSA@IR-808-Br2. Adapted with permission [176]. Copyright 2020, The Royal Society of Chemistry. (c) Schematic illustration of enhanced radiotherapy using porous Pt NPs. Adapted with permission [178]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier.

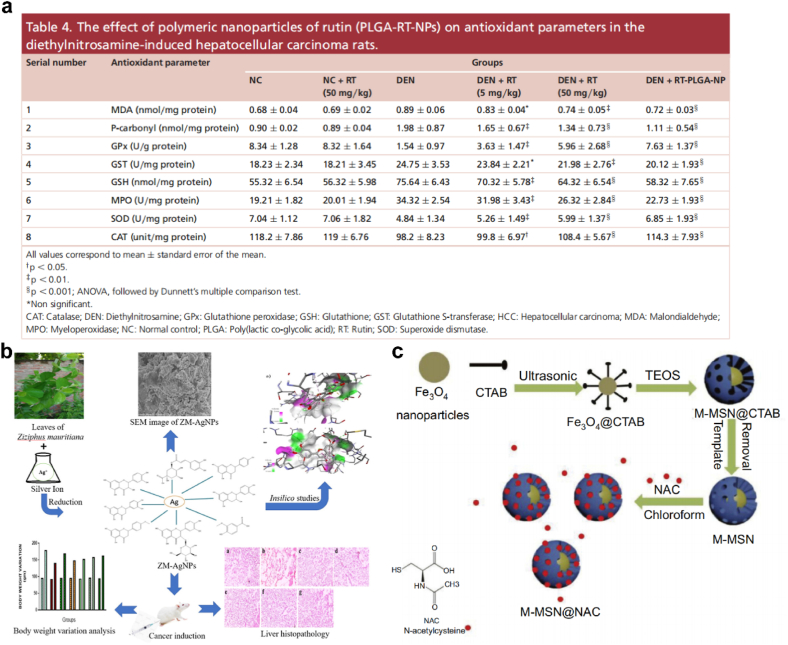

4.2. H2O2 scavengers

The utilization of free radical scavenging mechanisms for the treatment of liver fibrosis is also an effective antioxidative therapy targeting oxidative-stress microenvironment. H2O2 scavengers, containing endogenous antioxidant species (e.g., Vitamins C, carotenoids, flavonoids, AsA, GSH, etc.) and exogenous antioxidant enzymes (e.g., CAT, GPX, etc.), have been served to prevent or repair damage caused by free radicals [179]. Diethylnitrosamine (DEN)-induced HCC model was achieved with increased ROS production and disturbed cellular endogenous redox balance. Natural products, such as R‐phycoerythrin‐rich protein [180], Silibinin [181] and Rutin [182], have been reported to be strong antioxidants and free-radical scavengers in HCC treatment. To improve the biopharmaceutical and preclinical performance against HCC, Pandey et al. designed a novel Rutin (RT)-loaded PLGA NPs (RT-PLGA-NP) for HCC treatment. RT-PLGA-NP increased levels of SOD, CAT, GSH and GPx compared with DEN control group, which could be used for improving the biopharmaceutical and preclinical performance against HCC (Fig. 13a) [183]. Sameem et al. also targeted the biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles. The synthesized nanoformulation loaded with biomolecules present in Ziziphus mauritiana extract effectively inhibited the growth of hepatic cancer via reducing oxidative stress (Fig. 13b) [184].

Fig. 13.

(a) The effect of polymeric nanoparticles of rutin (PLGA-RT-NPs) on antioxidant parameters in the diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocellular carcinoma rats. Adapted with permission [183]. Copyright 2018, Future Medicine. (b) Scheme illustrating the biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles loaded with biomolecules presented in Ziziphus mauritiana extract with anticancer activity evaluation against hepatic cancer. Adapted with permission [184]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (c) Schematic diagram of synthesis of M-MSN@NAC. Adapted with permission [192]. Copyright 2019, Dovepress.

In tumor hypoxia, tumor macrophage was polarized from M1 phenotype to M2 phenotype, which protected tumor cells from immune system attack [185]. CAT, as a major antioxidant enzyme, could remove overexpressed H2O2 in tumor tissue and promote tumor oxygenation. To enhance the combined therapeutic efficacy, Liu et al. synthesized fluorinated chitosan as a highly effective non-toxic transmucosal delivery carrier and assembled with TCPP-conjugated CAT to form nanoparticles [186]. CAT catalyzed O2 generation helped to improve therapeutic efficacy of sonodynamic therapy (SDT). Chao et al. utilize liposome drug delivery system to load CAT, lyso-targeted NIR photosensitizer (MBDP) and Dox simultaneously for synergistic chem-PDT and immunosuppressive TME reversion [185]. Furthermore, CAT could improve tumor hypoxic microenvironment and enhance the function of sorafenib (SOR) in inhibiting tumor angiogenesis. Li et al. constructed PLGA microspheres (SOR-CAT-PLGA MSs) encapsulating SOR and CAT. The SOR-CAT-PLGA MSs could significantly improve the therapeutic effect on rabbit liver tumors [187].

Zhang et al. found that the primary organosulfur compound in garlic, Diallyl trisulfide (DATS), could produce hydrogen sulfide (H2S) in vivo and suppress oxidative stress-induced HSCs activation. Study showed that DATS decreased the intracellular lipid peroxide levels and increased the levels of GSH in H2O2-treated HSCs with generation of H2S [188]. Another example is N-acetylcysteine (NAC). As a precursor of GSH, NAC has been examined with potent hepatoprotective activity [189]. NAC is an organosulfur compound derived from Allium plants, which has strong clearance capability of free radicals. Notably, NAC is the only FDA-approved antioxidant for treatment of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity [190]. NAC has been reported to protect liver against CCl4 and TAA induced chronic liver injury through decreasing oxidative stress by regenerating antioxidant enzymes and GSH levels [191]. Co-delivery of NAC with iron oxide NPs has been demonstrated to mitigate the oxidative toxicity in hypoxia/reoxygenation cardiomyocytes (Fig. 13c) [192].

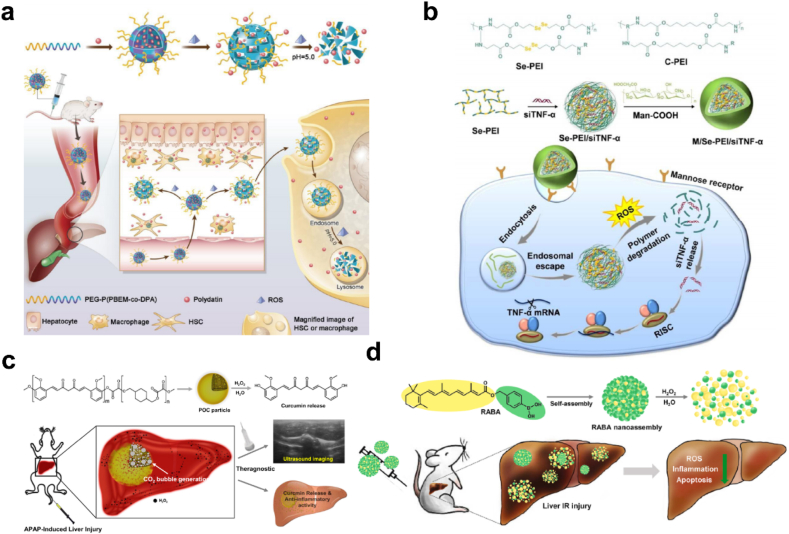

4.3. H2O2-sensitive nanosystems

Overproduction of H2O2 causes oxidative stress and becomes the hallmark of profibrotic/pro-tumor microenvironment. In response to the oxidative stress, Lin et al. developed a ROS and pH dual-sensitive block polymer PEG-P(PBEM-co-DPA) based polydatin-loaded micelle (PD-MC) for liver fibrosis amelioration (Fig. 14a). PBEM-co-DPA can responsively release polydatin upon ROS stimulation, which has been demonstrated hepatoprotective and antifibrotic capacities. PD-MC significantly improves utilization of polydatin and holds great potential in clinical application of polydatin against liver fibrosis [15]. Zhang et al. utilized a ROS-degradable tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) siRNA delivery system for treatment of acute liver failure (ALF) (Fig. 14b). TNF-α siRNA was compensated by the Man-COOH of Se-PEI polymer via electrostatic interaction. The ROS-responsive polyetheleneimine with diselenide bonds could degrade into small segments and potentiate gene knockdown efficiency in inflammatory microphages, which provided a new modality for the anti-inflammatory therapy of ALF [193].

Fig. 14.

(a) Schematic illustration of PD-MC as a ROS and pH dual-responsive nanodrug to regulate multiple cell types for the treatment of liver fibrosis. Adapted with permission [15]. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH. (b) Formation and intracellular kinetics of M/Se-PEI/siTNF-α polyplexes and ROS-triggered siRNA release. Adapted with permission [193]. Copyright 2018, The Royal Society of Chemistry. (c) Schematic illustration of POC as an ultrasound imaging and therapeutic agent for acute liver failure. Adapted with permission [194]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier. (d) Schematic illustration of H2O2-activatable hybrid prodrug nanoassemblies as a pure nanodrug for hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. Adapted with permission [195]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

H2O2-activatable nanodrugs are efficient due to synergistic targeted drug release and H2O2 scavenging capacity. Curcumin is a major active phenolic component of turmeric with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity, but its therapeutic potential is limited by poor solubility and stability. Lee et al. reported a H2O2-reactive poly(oxalate-co-curcumin) (POC) prodrug to scavenge H2O2 and released curcumin in a H2O2-triggered manner (Fig. 14c) [194]. Additionally, peroxalate esters in POC can be oxidated by H2O2 and generate CO2 bubble, which can serve as a platform for ultrasound imaging of H2O2 accumulation site in liver diseases. In 2022, Lee's group further designed a self-assembling all-trans retinoic acid-based (atRA) hybrid prodrug (RABA) for hepatic I/R injury (Fig. 14d) [195]. RABA nanoassemblies can react with the massive H2O2 generated during I/R injury and responsively release atRA, which exhibits significantly synergistic therapeutic efficacy.

For anti-tumor therapy, intertumoral ROS levels were improved to amplify the oxidative stress and accelerate drug release from ROS-responsive delivery systems. Sorafenib was the first-line treatment for unresectable HCC with approximately 40% available rate. To improve therapeutic efficiency, Xu et al. chose an ROS-responsive galactose-decorated lipopolyplex (Gal-SLP) to codelivery sorafenib and shUSP22. Sorafenib worked as an ROS inducer and triggered shUSP22 release to silence USP22, which inhibited HCC glycolysis and enhanced efficiency of sorafenib (Fig. 15a) [196]. Yin et al. applied palmitoyl ascorbate (PA) to generate H2O2 in tumor site, and a H2O2-sensitive amphiphilic block copolymer PEG-b-PBEMA was utilized to construct micelles. With H2O2 generation, the micelle was broken up and release quinone methide (QM) for GSH depletion, therefore amplifying oxidation damage against tumor cells (Fig. 15b) [197,198].

Fig. 15.

(a) Schematic illustration of a self‐activated cascade‐responsive co‐delivery system (Gal‐SLP) for synergetic cancer therapy. Adapted with permission [196]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH. (b) Schematic illustration of integrated micellar nanoparticles with tumor-specific H2O2 generation to elevate the oxidative stress in tumor tissue and simultaneous GSH depletion to suppress the antioxidant capability of cancer cells for amplified oxidation therapy. Adapted with permission [197]. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society.

4.4. Challenges of nanotherapeutics application

Despite the application of nanotherapeutics are highly promising, there are also negative-effect reports of the increased exposure of nanomaterials, especially nondegradable inorganic NPs, including oxidative stress leading to liver dysfunction, non-biodegradability and biopersistance of NPs, and their interactions with critical biomolecules [199]. 30–99% of exogenously administered nanoparticles were collected and accumulated in liver [200]. However, hepatic processing and biliary excretion of nanoparticles were usually slow and might take months [201]. Long-term usage of inorganic NPs increased the chronic liver toxicity with their prolonged retention time resulted from relatively slow clearance pathways in liver [199]. Yun et al. found that extensive systemic distribution of Ag originating from the Ag NPs resulted in increases of serum ALP and calcium. Daily oral dosing of Ag NPs exerted increased lymphocyte infiltration in liver, which caused rising possibility of liver toxicity [202].

Additionally, nanomaterials with ROS-generating capabilities could initiate cytotoxicity through direct NP-DNA interaction or cellular oxidative stress. NPs degradation induced ROS and ROS mediated detrimental effects, such as DNA damage, mRNA degradation, gene perturbation, etc., were toxic to cell activity [203]. After exerting expected therapeutic functions, the increased ROS level might also impair ambient normal tissues. Besides, ROS-generating functions of insufficient degraded nanomaterials might still exist sustained oxidative damage [204]. More recent advances in the field of nanomaterials development have not been extensively tested in preclinical models of liver fibrosis until today. Specifically targeting crucial cell types of the liver and to deliver potent anti-inflammatory or anti-fibrotic drugs with low systemic toxicity remained to be defined in the future [205]. Therefore, the application of these nanotherapeutics for liver fibrosis and HCC is still challenging, and biodegradable or biocompatible nanosystems were preferably recommended.

5. Conclusions and future perspectives

Liver fibrosis was the major causes of morbidity and mortality of patients with chronic liver disease, and eventually developed into HCC without effective therapy. At this stage, the research on the mechanism of liver fibrosis has been relatively adequate. The role of oxidative stress in liver fibrosis pathobiology is complex. ROS, especially H2O2, has typically been considered as a main incentive in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. To our knowledge, NOXs, peroxisome and mitochondria electron transport chain are the major source of H2O2 in hepatic metabolic disorders. H2O2 induces liver fibrosis via activating HSC, injuring hepatic parenchymal cells and regulating immunocytes. What's more, H2O2 could diffuse into nuclear and cause DNA oxidative damage and lipid peroxidation, thereby inducing hepatocarcinogenesis. Thus, alleviation of H2O2 accumulation to avoid oxidative damage should be a potential approach for liver fibrosis and HCC therapy.

Specific pharmacological approaches that selectively target oxidative pathways for liver fibrosis treatment are still lacking, and numerous challenges remain to be overcame [23]. Due to the unique characteristics of liver, various kinds of nanomaterials were designed to specifically accumulated in liver. Nanotherapeutics integrated multiple antioxidant functions and drug-controlled release to obtain synergistic efficacy. But only few nanodrugs have entered clinical trials with approved pharmaceutical ingredients and liposomal or polymer carrier, and these commercial vehicles have the advantage of controllable costs [25,206]. The nanotherapeutics discussed above, especially non-biodegradable inorganic materials-based nanodrugs, were facing challenges of in vivo metabolism, long-term accumulation induced toxicity and costly synthesis process [25]. Even through, the development of nanotherapeutics against liver fibrosis provided more treatment options, and intensive investigation in this direction will be critical to making key discoveries that will ultimately find novel therapeutic approaches.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mengyun Peng and Gang Cao conceptualized the study and approved it for publication; Yifan Wang, Hongyan Dong and Xiaoqing Zhang selected articles and collected data; Xin Han, Xianan Sang and Yini Bao provided professional assistance during the manuscript writing; Meiyu Shao and Mengyun Peng wrote this manuscript. Lu Wang revised the manuscript carefully.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Live animals or human subjects is not involved in the review. Therefore, there is no ethical statements that are provided by authors.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52003246,81922073 and 81973481); the Traditional Chinese Medicine Key Scientific Research Fund Project of Zhejiang Province (Nos. 2018ZY004, 2022ZQ032 and 2021ZZ009); and the Youth Natural Science Program of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (2021JKZKTS007A).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

Contributor Information

Mengyun Peng, Email: pmy@zcmu.edu.cn.

Gang Cao, Email: caogang33@163.com.

References

- 1.Pimpin L., Cortez-Pinto H., Negro F., Corbould E., Lazarus J.V., Webber L., Sheron N., Committee E.H.S. Burden of liver disease in Europe: epidemiology and analysis of risk factors to identify prevention policies. J. Hepatol. 2018;69(3):718–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakurai T., Kudo M., Umemura A., He G., Elsharkawy A.M., Seki E., Karin M. p38α inhibits liver fibrogenesis and consequent hepatocarcinogenesis by curtailing accumulation of reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res. 2013;73(1):215–224. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ismail M.H., Pinzani M. Reversal of liver fibrosis. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2009;15(1):72–79. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.45072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang S., Liu H., Yin M., Pei X., Hausser A., Ishikawa E., Yamasaki S., Jin Z.G. Deletion of protein kinase D3 promotes liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2020;72(5):1717–1734. doi: 10.1002/hep.31176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ke M.Y., Xu T., Fang Y., Ye Y.P., Li Z.J., Ren F.G., Lu S.Y., Zhang X.F., Wu R.Q., Lv Y., Dong J. Liver fibrosis promotes immune escape in hepatocellular carcinoma via GOLM1-mediated PD-L1 upregulation. Cancer Lett. 2021;513:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marti-Rodrigo A., Alegre F., Moragrega A.B., Garcia-Garcia F., Marti-Rodrigo P., Fernandez-Iglesias A., Gracia-Sancho J., Apostolova N., Esplugues J.V., Blas-Garcia A. Rilpivirine attenuates liver fibrosis through selective STAT1-mediated apoptosis in hepatic stellate cells. Gut. 2020;69(5):920–932. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tacke F., Zimmermann H.W. Macrophage heterogeneity in liver injury and fibrosis. J. Hepatol. 2014;60(5):1090–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang D.Y., Friedman S.L. Fibrosis-dependent mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology. 2012;56(2):769–775. doi: 10.1002/hep.25670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baglieri J., Brenner D.A., Kisseleva T. The role of fibrosis and liver-associated fibroblasts in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(7):1723. doi: 10.3390/ijms20071723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carloni V., Luong T.V., Rombouts K. Hepatic stellate cells and extracellular matrix in hepatocellular carcinoma: more complicated than ever. Liver Int. 2014;34(6):834–843. doi: 10.1111/liv.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novo E., Busletta C., Bonzo L.V., Povero D., Paternostro C., Mareschi K., Ferrero I., David E., Bertolani C., Caligiuri A., Cannito S., Tamagno E., Compagnone A., Colombatto S., Marra F., Fagioli F., Pinzani M., Parola M. Intracellular reactive oxygen species are required for directional migration of resident and bone marrow-derived hepatic pro-fibrogenic cells. J. Hepatol. 2011;54(5):964–974. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth K.J., Copple B.L. Role of hypoxia-inducible factors in the development of liver fibrosis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015;1(6):589–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morry J., Ngamcherdtrakul W., Yantasee W. Oxidative stress in cancer and fibrosis: opportunity for therapeutic intervention with antioxidant compounds, enzymes, and nanoparticles. Redox Biol. 2017;11:240–253. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ljubuncic P., Tanne Z., Bomzon A. Evidence of a systemic phenomenon for oxidative stress in cholestatic liver disease. Gut. 2000;47(5):710–716. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.5.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin L., Gong H., Li R., Huang J., Cai M., Lan T., Huang W., Guo Y., Zhou Z., An Y., Chen Z., Liang L., Wang Y., Shuai X., Zhu K. Nanodrug with ROS and pH dual-sensitivity ameliorates liver fibrosis via multicellular regulation. Adv. Sci. 2020;7(7) doi: 10.1002/advs.201903138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee D., Xu I.M.-J., Chiu D.K.-C., Leibold J., Tse A.P.-W., Bao M.H.-R., Yuen V.W.-H., Chan C.Y.-K., Lai R.K.-H., Chin D.W.-C., Chan D.F.-F., Cheung T.-T., Chok S.-H., Wong C.-M., Lowe S.W., Ng I.O.-L., Wong C.C.-L. Induction of oxidative stress through inhibition of thioredoxin reductase 1 is an effective therapeutic approach for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2019;69(4):1768–1786. doi: 10.1002/hep.30467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mailloux R.J. An update on methods and approaches for interrogating mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. Redox Biol. 2021;45 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das K., Roychoudhury A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and response of antioxidants as ROS-scavengers during environmental stress in plants. Front. Environ. Sci. 2014;2 Article 53. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luangmonkong T., Suriguga S., Mutsaers H.A.M., Groothuis G.M.M., Olinga P., Boersema M. Targeting oxidative stress for the treatment of liver fibrosis. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018;175:71–102. doi: 10.1007/112_2018_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parola M., Robino G. Oxidative stress-related molecules and liver fibrosis. J. Hepatol. 2001;35(2):297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cichoż-Lach H., Michalak A. Oxidative stress as a crucial factor in liver diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8082–8091. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y., Branicky R., Noë A., Hekimi S. Superoxide dismutases: dual roles in controlling ROS damage and regulating ROS signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2018;217(6):1915–1928. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201708007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Z., Tian R., She Z., Cai J., Li H. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020;152:116–141. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu L.P., Wang D., Li Z. Grand challenges in nanomedicine. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2020;106 doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.110302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu M., Huang Q., Zhu Y., Chen L., Li Y., Gong Z., Ai K. Harnessing reactive oxygen/nitrogen species and inflammation: nanodrugs for liver injury. Materials Today Bio. 2022;13 doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenwel P., Domínguez-Rosales J.-A., Mavi G., Rivas-Estilla A.M., Rojkind M. Hydrogen peroxide: a link between acetaldehyde-elicited α1(i) collagen gene up-regulation and oxidative stress in mouse hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2000;31(1):109–116. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong Y., Qu Y., Xu M., Wang X., Lu L. Catalase ameliorates hepatic fibrosis by inhibition of hepatic stellate cells activation. Front. Biosci. 2014;19:535–541. doi: 10.2741/4224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinzani M. Pathophysiology of liver fibrosis. Dig. Dis. 2015;33(4):492–497. doi: 10.1159/000374096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahaseth T., Kuzminov A. Potentiation of hydrogen peroxide toxicity: from catalase inhibition to stable DNA-iron complexes. Rev. Mutat Res. 2017;773:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delgado M.E., Cárdenas B.I., Farran N., Fernandez M. Metabolic reprogramming of liver fibrosis. Cells. 2021;10(12):3604. doi: 10.3390/cells10123604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trefts E., Gannon M., Wasserman D.H. The liver. Curr. Biol. 2017;27(21):R1147–r1151. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alves-Bezerra M., Cohen D.E. Triglyceride metabolism in the liver. Compr. Physiol. 2017;8(1):1–8. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c170012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.You M., Arteel G.E. Effect of ethanol on lipid metabolism. J. Hepatol. 2019;70(2):237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng M., Wang X.-Q., Zhang Y., Li C.-X., Zhang M., Cheng H., Zhang X.-Z. Mitochondria-targeting thermosensitive initiator with enhanced anticancer efficiency. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2019;2:4656–4666. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.9b00739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ott M., Gogvadze V., Orrenius S., Zhivotovsky B. Mitochondria, oxidative stress and cell death. Apoptosis. 2007;12(5):913–922. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0756-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crosas-Molist E., Fabregat I. Role of NADPH oxidases in the redox biology of liver fibrosis. Redox Biol. 2015;6:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mansouri A., Gattolliat C.H., Asselah T. Mitochondrial dysfunction and signaling in chronic liver diseases. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(3):629–647. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vial G., Dubouchaud H., Couturier K., Cottet-Rousselle C., Taleux N., Athias A., Galinier A., Casteilla L., Leverve X.M. Effects of a high-fat diet on energy metabolism and ROS production in rat liver. J. Hepatol. 2011;54(2):348–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruiz-Ramírez A., Chávez-Salgado M., Peñeda-Flores J.A., Zapata E., Masso F., El-Hafidi M. High-sucrose diet increases ROS generation, FFA accumulation, UCP2 level, and proton leak in liver mitochondria. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;301(6):E1198–E1207. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00631.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ganne-Carrié N., Nahon P. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the setting of alcohol-related liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2019;70(2):284–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Z., Sun R., Wang G., Chen Z., Li Y., Zhao Y., Liu D., Zhao H., Zhang F., Yao J., Tian X. SIRT3-mediated deacetylation of PRDX3 alleviates mitochondrial oxidative damage and apoptosis induced by intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Redox Biol. 2020;28 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee S., Tak E., Lee J., Rashid M.A., Murphy M.P., Ha J., Kim S.S. Mitochondrial H2O2 generated from electron transport chain complex I stimulates muscle differentiation. Cell Res. 2011;21(5):817–834. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen C., Wang S., Yu L., Mueller J., Fortunato F., Rausch V., Mueller S. H2O2-mediated autophagy during ethanol metabolism. Redox Biol. 2021;46 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Misra U.K., Bradford B.U., Handier J.A., Thurman R.G. Chronic ethanol treatment induces H2O2 production selectively in pericentral regions of the liver lobule. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 1992;16(5):839–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang C., Cho W., Park M., Kim J., Park S., Shin D., Song C., Lee D. H2O2-triggered bubble generating antioxidant polymeric nanoparticles as ischemia/reperfusion targeted nanotheranostics. Biomaterials. 2016;85:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hernansanz-Agustin P., Choya-Foces C., Carregal-Romero S., Ramos E., Oliva T., Villa-Pina T., Moreno L., Izquierdo-Alvarez A., Cabrera-Garcia J.D., Cortes A., Lechuga-Vieco A.V., Jadiya P., Navarro E., Parada E., Palomino-Antolin A., Tello D., Acin-Perez R., Rodriguez-Aguilera J.C., Navas P., Cogolludo A., Lopez-Montero I., Martinez-Del-Pozo A., Egea J., Lopez M.G., Elrod J.W., Ruiz-Cabello J., Bogdanova A., Enriquez J.A., Martinez-Ruiz A. Na(+) controls hypoxic signalling by the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Nature. 2020;586:287–291. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2551-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hernansanz-Agustín P., Ramos E., Navarro E., Parada E., Sánchez-López N., Peláez-Aguado L., Cabrera-García J.D., Tello D., Buendia I., Marina A., Egea J., López M.G., Bogdanova A., Martínez-Ruiz A. Mitochondrial complex I deactivation is related to superoxide production in acute hypoxia. Redox Biol. 2017;12:1040–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lennicke C., Rahn J., Lichtenfels R., Wessjohann L.A., Seliger B. Hydrogen peroxide – production, fate and role in redox signaling of tumor cells. Cell Commun. Signal. 2015;13(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s12964-015-0118-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nishikawa M., Hashida M., Takakura Y. Catalase delivery for inhibiting ROS-mediated tissue injury and tumor metastasis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009;61(4):319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sousa V.C., Carmo R.F., Vasconcelos L.R., Aroucha D.C., Pereira L.M., Moura P., Cavalcanti M.S. Association of catalase and glutathione peroxidase 1 polymorphisms with chronic hepatitis C outcome. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2016;80(3):145–153. doi: 10.1111/ahg.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen J.X., Wang H.Y., Li C., Han K., Zhang X.Z., Zhuo R.X. Construction of surfactant-like tetra-tail amphiphilic peptide with RGD ligand for encapsulation of porphyrin for photodynamic therapy. Biomaterials. 2011;32(6):1678–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glorieux C., Zamocky M., Sandoval J.M., Verrax J., Calderon P.B. Regulation of catalase expression in healthy and cancerous cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;87:84–97. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Han X., Wu Y., Yang Q., Cao G. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in the pathogenesis and therapies of liver fibrosis. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021;222 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koliaki C., Szendroedi J., Kaul K., Jelenik T., Nowotny P., Jankowiak F., Herder C., Carstensen M., Krausch M., Knoefel W.T., Schlensak M., Roden M. Adaptation of hepatic mitochondrial function in humans with non-alcoholic fatty liver is lost in steatohepatitis. Cell Metabol. 2015;21(5):739–746. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yasmineh W.G., Parkin J.L., Caspers J.I., Theologides A. Tumor necrosis factor/cachectin decreases catalase activity of rat liver. Cancer Res. 1991;51(15):3990–3995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fita I., Rossmann M.G. The active center of catalase. J. Mol. Biol. 1985;185(1):21–37. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Imai H., Nakagawa Y. Biological significance of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (PHGPx, GPx4) in mammalian cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;34(2):145–169. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mailloux R.J., McBride S.L., Harper M.-E. Unearthing the secrets of mitochondrial ROS and glutathione in bioenergetics. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2013;38(12):592–602. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Han S.J., Choi H.S., Kim J.I., Park J.-W., Park K.M. IDH2 deficiency increases the liver susceptibility to ischemia-reperfusion injury via increased mitochondrial oxidative injury. Redox Biol. 2018;14:142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu W.-B., Menon R., Xu Y.-Y., Zhao J.-R., Wang Y.-L., Liu Y., Zhang H.-J. Downregulation of peroxiredoxin-3 by hydrophobic bile acid induces mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular senescence in human trophoblasts. Sci. Rep. 2016;6(1) doi: 10.1038/srep38946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lu S.C. Regulation of hepatic glutathione synthesis, Semin. Liver Dis. 1998;18(4):331–343. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Laurent A., Nicco C., Chéreau C., Goulvestre C., Alexandre J.r.m., Alves A., Lévy E., Goldwasser F., Panis Y., Soubrane O., Weill B., Batteux F.d.r. Controlling tumor growth by modulating endogenous production of reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res. 2005;65(3):948–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jones D.P., Carlson J.L., Mody V.C., Cai J., Lynn M.J., Sternberg P. Redox state of glutathione in human plasma. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;28(4):625–635. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00275-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]