Abstract

We use US state-level data from early in the pandemic —March 15, 2020 to November 15, 2020— to estimate the effects of mask mandates and compliance with mandates on Covid-19 cases and deaths, conditional on mobility. A one-standard-deviation increase in mobility is associated with a 6 to 20 percent increase in the cases growth rate; a mask mandate can offset about one third of this increase with our most conservative estimates. Also, mask mandates are more effective in states with higher compliance. Given realized mobility, our estimates imply that total infections in the US on November 15, 2020 would have been 23.7 to 30.4 percent lower if a national mask mandate had been enacted on May 15, 2020. This reduction in cases translates to a 25 to 35 percent smaller decline in aggregate hours worked over the same period relative to a 2019 baseline.

Keywords: Covid-19 cases and deaths, Mobility, Mask wearing, Mask mandates

1. Introduction

This paper uses state-level variation in Covid-19 cases and deaths counts, mobility, mask mandates, reported mask wearing, and other related factors to study the mitigating effect of face masks on the early spread of Covid-19 in the United States. Early in the pandemic, two main types of public policies were enacted in the pursuit of lower virus transmission: containment policies and mask mandates. Most containment policies, including stay-at-home orders and school and nonessential business closures, were intended to prevent the spread of the virus by limiting mobility and thus reducing interactions between people (for a discussion of the impact of various containment policies on mobility and related outcomes see, for example, Schlossser et al., 2020, Kosfeld et al., 2021). While potentially very effective, these policies came at the cost of reducing transactions that required in-person interactions, thereby curtailing output and human capital formation. On the other hand, public health measures like encouraging hand washing or mandating mask wearing, were intended to reduce the likelihood of infection when people moved around, and were likely much less costly for the economy. Mask mandates remain highly contentious, and a good understanding of the effectiveness of public health measures like mask mandates is important for public policy makers trying to determine to what extent they should limit mobility and social contact when combating future pandemics before vaccines and effective treatments become available.

We condition our analysis of the public health benefits of mask wearing on observed mobility and use a variety of cellphone-based mobility indexes to comprehensively summarize several dimensions of human movement (e.g., visits to businesses, contact with others). Importantly, we quantify the extent to which mask mandates and mask wearing offset the effects of mobility on the numbers of Covid-19 cases and related deaths early in the pandemic, from March 15, 2020 to November 15, 2020. We first show that during those 8 months mobility is associated with a higher rate of growth in Covid-19 case counts—a relationship that is documented in other studies (see, for example, Xiong et al., 2020, Nouvellet et al., 2021). The correlation of mobility and the growth rate of cases (and deaths) is similar regardless of how we measure human movements. A one-standard-deviation increase in mobility leads to a roughly 6 to 20 percent larger growth rate of Covid-19 cases in the immediate future. Higher mobility is also associated with a higher growth rate of Covid-19 deaths. The effects are strongest and most precisely estimated in specifications where mobility is lagged seven or more days relative to the growth in cases and 14 days relative to the increase in the number of deaths—a finding that is consistent with the documented incubation period for the virus in the early stages of the pandemic.

The strong positive link between mobility and the growth in Covid-19 cases appears to be mitigated to a certain extent by mask mandates. This result is relevant because required mask wearing is a relatively inexpensive policy intervention compared to mandated reductions in mobility. Importantly, we find that mask mandates combined with higher levels of compliance in a given state (measured using survey data on mask wearing) are associated with larger reductions in the growth of Covid-19 cases. By offsetting some of the effect of mobility on the case-count growth rate, mask mandates and mask wearing ultimately reduce the death-count growth rate as well.

Based on our results and given realized mobility, we conduct a series of counterfactual exercises which show that if a national mask mandate had been enacted on May 15, 2020, total infections in the US on November 15, 2020 would have been about 23.7 to 30.4 percent lower. The reduced incidence of the virus due to the national mask mandate would have also had potentially relevant economic benefits. In particular, we find that the reduction in cases associated with our counterfactual mask mandate would translate into a 25 to 35 percent smaller decline in hours worked over the same period relative to a 2019 baseline.

There is extensive research examining the public health issues and economic effects of Covid-19. Several papers study the relationship between mobility and Covid-19 cases in the United States—by looking at a variety of factors that likely impact cross-location differences in infection rates, such as income, inequality, weather, debt burdens, the ability to work from home, and population density, to name a few (see, for example, Wilson, 2020, Desmet and Wacziarg, 2022, Davydiuk and Gupta, 2020). Related epidemiological papers that also study factors affecting the spread of the virus include Baqaee et al. (2020), Kissler et al. (2020), and Giuliani et al. (2020).

Relative to existing research, we incorporate additional relevant controls including the persistence in the growth rate of cases/deaths, a feature of some structural epidemiological models, by including the lagged growth rate in our regressions. This practice is not common in the recent studies that use reduced-form regression analysis. Indeed, the lagged case growth rate is quite important in explaining the variation in infection rates across locations and over time, as it helps capture the exponential effects of changes in mobility and mask policies that occurred early on in the pandemic. We further consider specifications that control for other relevant factors that potentially impacted infection rates, including differences in testing across locations, and we also discuss the conditions needed for a causal interpretation of our estimates.

Studies on the effect of mask mandates and actual mask wearing on the growth in Covid-19 cases early in the pandemic are more limited. Lyu and Wehby (2020) use an event-study approach to analyze how state-level mask mandates affected daily county-level Covid-19 infection rates from March 31 through May 22, 2020. The authors find that mask mandates reduced the growth rate of cases, and that the mitigating effect increased with the number of days following the mandate’s implementation. In another related paper, Chernozhukov et al. (2020) show that policies and information regarding transmission risk are important determinants of Covid-19 cases and deaths. The authors conduct counterfactuals examining the potential effect of a national mask mandate early in the pandemic and find that such a mandate would have limited case growth in April and May 2020. Similar analyses of the effects of mask mandates in other countries such as Germany (Mitze et al., 2020) and Canada (Karaivanov et al., 2021) also show significant reductions in case counts after mandates were introduced.1 Compared to these studies, we use a different estimation procedure and different counterfactuals, and we consider the effect of mask mandates and mobility restrictions on the Covid-19 case counts over a much longer time period, which includes a time when mobility was higher than after the initial lockdown period. Moreover, unlike these existing studies, we consider the fact that actual mask wearing is not guaranteed even when mask mandates are in place and importantly that the degree of compliance varies across locations. Therefore, we supplement our mask mandate analysis with data on actual mask wearing and attitudes toward masks collected by Dynata for the New York Times in early July 2020. These data proxy for differences in compliance with the mandates across geographies. While there is some analysis examining the relationship between mask wearing and the Covid-19 case count (see, for example, Cheng et al., 2020, Dyke et al., 2020, IHME Forecasting Team, 2020, Bundgaard et al., 2020), to our knowledge our analysis is unique in combining data on mask mandates with data on mask usage to gauge the impact of compliance on the effectiveness of the mandates. Finally, we estimate the counterfactual employment benefits of fewer Covid-19 cases.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 discusses our data. Section 3 presents the empirical specification. Section 4 reports our empirical results, discusses the conditions needed for a causal interpretation of our results, and presents our counterfactuals. Section 5 concludes.

2. Data

Our data include information on the numbers of Covid-19 infections and deaths, as well as measures of mobility, weather conditions, mask mandates, and mask wearing.

Covid-19 Data. We obtain data on daily case and death counts from DataHub, which cleans and normalizes data from the Johns Hopkins University Center for Systems Science and Engineering.2 Panel A of Fig. 1 shows that there is substantial variation in the daily numbers of new cases (averaged over a seven-day rolling window) across states and over time. After a period of convergence across states to lower levels of daily cases relative to population (case rates) in late May and early June 2020, daily case rates across states diverged again in mid-June, when infection rates in some states surged. A third wave of new cases began in mid-October 2020, as colder weather set in, with many states passing their previous peak levels of infection rates.

Fig. 1.

State-Level Variation in Covid-19 Cases, Mobility, and Mask Mandate Introduction.

Notes: Cases from the Johns Hopkins University Center for Systems Science and Engineering via DataHub (https://datahub.io/core/covid-19). Mobility data from SafeGraph Social Distancing Metrics. Data on mandates from the websites of the different states as of November 1, 2020.

Mobility. All of our measures come from anonymized cellphone ping data aggregated in different ways. The various measures fall into three categories: (1) indexes that track visits to landmarks or places of business, (2) indexes that measure time spent at home, and (3) indexes that quantify contacts between individuals. Information on contacts (or lack there of) potentially serves as a proxy for the degree of social distancing, while the visit data capture the extent to which individuals are moving around regardless of whether they make contact with others. These approaches for measuring mobility capture slightly different aspects of individuals’ movements that could have affected Covid-19 case (and death) counts somewhat differently. Therefore, we consider all three types in our analysis.

In particular, we focus on state-level mobility measures and use data from Safegraph (SG) on visits outside of the home and time spent at home, along with the Cuebiq contact index (CI) and the PlaceIQ device exposure index (DEX). The SG “visit” data capture the year-over-year change in the total number of visits to SG’s network of points of interest. SG “time at home” measures the median percentage of time that cellphones within a census block group (CBG) stay at their “home” locations each day. We construct state-level time-at-home measures by taking a population-weighted average of the relevant CBG data.3 The Cuebiq CI measures whether two or more cellular devices come within 50 ft of each other in a five-minute period.4 Finally, the PlaceIQ DEX captures the number of devices that visit the same venue in the same day.5 For more details on these measures, see Appendix A.

Panel B of Fig. 1 depicts the state-level variation in one of our mobility measures (daily values averaged over a seven-day rolling window), SG time at home.6 The wave of stay-at-home orders in March 2020 resulted in a substantial decline in mobility (and increased time at home), which was followed by a clear increase in mobility in most states starting in mid-April when some of these orders were lifted. Dispersion in mobility across states also increased. Despite the rebound, mobility remained below where it was before the pandemic in most states during our sample period.7

Local Mobility Restrictions. We use daily data from the Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker to measure the degree of locally imposed mobility restrictions. In particular, we use several components of their Oxford Stringency Index and average information on the following metrics: school closings, workplace closings, canceled public events, restrictions on gatherings, public transport closures, stay at home requirements, restrictions on internal movement, and international travel controls. Each component is measured based on an ordinal scale typically ranging from 0 to 3, and the overall index we compute is a simple average of the individual components.

Weather. We use daily average temperature data at the state level from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Data for Alaska and Hawaii are for Anchorage and Honolulu, respectively, as state-level data are not reported.

Mask Mandates. Data on mandates come primarily from state public health websites. There are data on when a state’s mandate was announced, the date it took effect, and the extent and coverage of the mandate. We verify the reported dates against various published sources, including www.masks4all.org, www.ballotpedia.org, and the appendix of Lyu and Wehby (2020). Given our state-level analysis, we consider only statewide mandates and use the date when the governor’s office issued the mandate as the enactment date. Panel C of Fig. 1 shows that the majority of states eventually had a state-wide mask mandate; however, there is substantial variation in when the mandates went into effect—ranging from mid- to late April 2020 in several northeastern states to early November 2020, when Utah became the latest state to enact a statewide mask mandate. As of November 15, 2020, 15 states had only partial (not statewide) mask policies.

Mask Wearing. Data on mask-wearing behavior comes from a survey conducted by Dynata on behalf of the New York Times from July 2 through July 14, 2020. The survey garnered roughly 250,000 responses to the question, “How often do you wear a mask in public when you expect to be within six feet of another person?” The survey includes county- and state-level geographic identifiers for the respondents. For our analysis, we calculated the proportion of people in a state who responded either “always” or “frequently” to this question. While the survey was conducted only once, there is substantial state-level variation in reported mask wearing.8 Furthermore, there is meaningful variation in mask wearing that is distinct from the variation in mask mandates. For example, while both Maine and Delaware instituted state-wide mask mandates on May 1, 2020, Delaware had the fourth-highest rate of mask use in the Times survey, and Maine was in 26th place. In fact, the presence of mandates (measured as of the start of the survey) explains only half of the state-level variation in mask wearing. In turn, preexisting state-level characteristics, such as the proportion of votes in a state for the Republican party in the 2016 presidential election or beliefs about climate change, can explain more than 82 percent of the variation.9 We therefore interpret our mask-wearing measure as a state-level proxy for overall compliance with mask-wearing mandates.10 We recognize that mask wearing is likely correlated with other Covid-19 mitigation behaviors, such as maintaining adequate social distance, though one can argue that these behaviors are impacted by public health information campaigns.

3. Empirical specification

To more formally analyze the relationship between mobility, masks, and Covid-19 cases/deaths, we begin by defining the growth rate of new infections or deaths as follows:

where is the cumulative number of Covid-19 cases (deaths) at time in state . For cases, is the average number of newly infected people for each previously infected person, so this value largely reflects how quickly the virus is transmitting between people. For deaths, also depends on the deadliness of the virus once a person is infected. If , cases (deaths) continue to grow. If , no new cases (deaths) occur.

In our initial analysis, we model log growth rates of cases (deaths) as an exponential function of state fixed effects, time fixed effects, and mobility:

which can be transformed into the following linear estimation equation11 :

| (1) |

In this setup, is a state fixed effect that captures time-invariant differences across states that may affect the growth rate of new cases (deaths), captures common dynamics in the evolution of the pandemic, and is a (lagged) state-specific measure of mobility that is standardized to have mean 0 and standard deviation 1.

We adapt equation (1) slightly and estimate it using (overlapping) weekly growth rates of cases (deaths) to rule out day-of-week effects in testing and/or reporting. We analogously average mobility over a preceding number of days (discussed next) and include a lagged dependent variable to capture the persistent nature of local outbreaks of the virus.12

Our initial estimation equation therefore takes the form:

| (2) |

To decide on the number of days to include in the mobility measure and an appropriate lag, we explore the relationship of cases with mobility averaged over the preceding seven days for different lags (specifically, ) to capture the idea that changes in mobility might feed into measured cases with a delay because there is an incubation period before an individual tests positive for Covid-19.13 Based on the results from Tables B.1 and B.2 in Appendix B, we choose a specification for the growth rate of cases that measures mobility as an average over the most recent 21 days and lag this average by days—the estimated coefficients for the seven-day mobility averages for lags 7 to 21 were of similar magnitude and therefore such an averaging seems reasonable. For the growth rate of deaths, we use a specification where we average our mobility measures over 35 days and lag them days, as the estimates of Eq. (2) show a more delayed effect of mobility on deaths that persists at longer lags. This delayed impact of mobility on the growth rate of deaths relative to the growth rate of cases is expected given what we know about the disease. While some individuals succumb to Covid-19 rather quickly, others are initially helped by available medical interventions and therapeutics but take a turn for the worse weeks after becoming infected.

Our estimates are weighted by state population, and the coefficient measures how much one-standard-deviation higher mobility increases the log growth rate of Covid-19 cases (deaths). We employ all four measures of mobility for this analysis, primarily one at a time to avoid the issue of multicollinearity, although we present some estimates in which we simultaneously include multiple mobility measures for completeness.

To assess the role of mask mandates and mask use in the growth rate of new cases conditional on mobility, we modify equation (2) as follows:

| (3) |

where measures whether a face-mask mandate is in place at a given point in time. For consistency, we use a moving average of our mandate indicator covering the same time period as when mobility is measured. For example, if mobility is averaged over 21 days and a mask mandate is in place for 14 (21) [0] of those days in a given state, then is 2/3 (1) [0].

We add average temperature (climate conditions can affect virus transmission; see, for example, Baker et al., 2021) and local closure policies as measured by the Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker as additional controls, . However, we do not attempt to estimate the causal effect of mobility restrictions on case growth.14 Instead, our objective is to understand whether mask mandates, conditional on mobility, help to offset the effects of mobility on the spread of the virus and to what extent. We discuss the conditions needed for a causal interpretation of our mask mandate estimates in the next section.

For all of our empirical estimates, we calculate standard errors using a Driscoll–Kraay approach that is robust to autocorrelation, heteroskedasticity, and cross-sectional correlation.15 Because our log-growth-rate specification drops state-day observations that have no new cases or case growth, we also tried an alternative specification in which the dependent variable is the seven-day rolling average of new cases in a state relative to its population instead of the log growth rate. These results were similar and are not reported for brevity.16

4. Results

4.1. Mobility, face-mask mandates, and Covid-19 spread

Results from estimating equation (3) are presented in Table 1. Each column shows estimates using the mobility measure specified in the column heading. Overall, we find that increased mobility—more visits, more contacts, or less time at home—is associated with a 6 to 20 percent higher growth rate of cases.17 The magnitude of the estimated effects is generally similar across mobility measures, with slightly smaller effects for the PlaceIQ DEX. Mask mandates are negatively correlated with the growth rate of cases (deaths). This is true regardless of the mobility measure we use, although the estimated mandate effect is a bit larger (in absolute value) in regressions that control for contacts rather than visits. The presence of a mask mandate shrinks the case growth rate by 5 to 7 percent. Higher average temperatures and more stringent local mobility restrictions are also negatively correlated with the growth in cases (deaths). In addition, our estimated mobility and mask effects are robust to controlling for changes in testing capacity over time (see Table B.5 in Appendix B).

Table 1.

Mobility, mask mandates, cases and deaths: baseline results.

| Cases |

Deaths |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits | Home Time | PlaceIQ | Cuebiq | Visits | Home Time | PlaceIQ | Cuebiq | ||

| Mobility | 0.16* | –0.20*** | 0.06* | 0.13*** | 0.20*** | –0.21*** | 0.03 | −0.01 | |

| (0.08) | (0.07) | (0.03) | (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.05) | ||

| Mask Mandate | –0.06* | –0.05* | –0.07** | –0.07** | −0.08 | –0.09 | –0.12** | –0.12** | |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.06) | ||

| Avg. Temperature | –0.01* | –0.01* | –0.01* | −0.01 | –0.05*** | –0.05*** | –0.05*** | –0.04*** | |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | ||

| Local Mob. Restrictions Index | −0.07 | –0.06 | –0.11* | –0.10** | −0.05 | –0.06 | –0.14* | –0.16** | |

| (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.07) | (0.05) | (0.07) | (0.07) | (0.07) | (0.08) | ||

| Lag LHS | 0.85*** | 0.85*** | 0.85*** | 0.85*** | 0.71*** | 0.71*** | 0.71*** | 0.72*** | |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.03) | ||

| Adj. R-squared. | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.61 | |

| Adj. R-squared w FE | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.92 | |

| Obs | 12 110 | 12 110 | 12 110 | 11 637 | 11 046 | 11 046 | 11 046 | 10 759 | |

| State FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Date FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Pop. weights | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

Notes: Estimation equation (3): where denotes Covid-19 cases/deaths in state at date , measured in days. and denote state fixed effects and time fixed effects, respectively. denotes mobility, and is the lag operator. The mobility measures for the case (death) regressions are averaged over 21 (35) days and lagged 7 (14) days. All mobility measures are standardized for easier interpretation of the coefficients. measures whether a face mask mandate is in place during the time period when mobility is measured. The timing of the mask mandate measure as well as that of the temperature and the local mobility restrictions controls in match the corresponding mobility averaging and lag structure. Regressions are weighted by state population and use Driscoll–Kraay standard errors. The sample includes all available observations between March 15, 2020 and November 15, 2020.

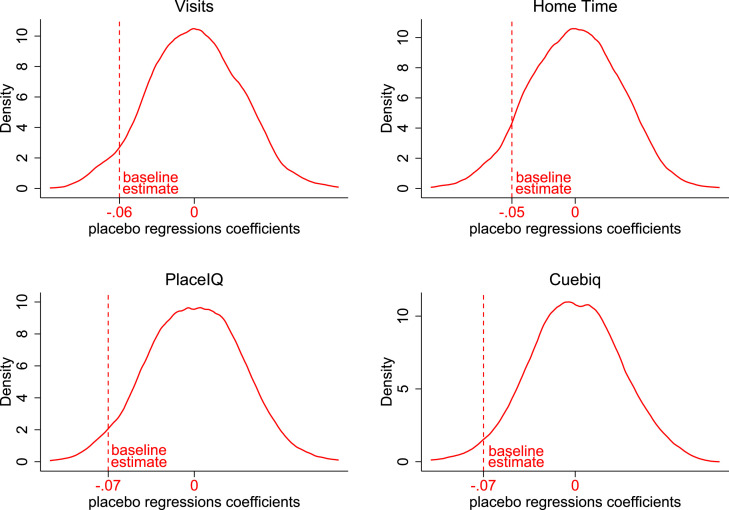

As an initial check that our estimated mask mandate effects are not spurious, we perform placebo tests where we randomly shuffle the mask mandate enactment dates across states. Fig. 2 shows Kernel densities of the estimated mask mandate effects on cases from these placebo regressions. These estimates are consistent with actual mask mandates likely having a real effect and contributing to a slow down in the growth rate of cases. (For deaths, see Figure B.3 in Appendix B.)

Fig. 2.

Mask Mandates and Cases: Baseline Placebo Regression Estimates.

Notes: Kernel densities of the estimated of mask mandate effects, in Eq. (3), from 1000 placebo regressions where we reshuffle mask mandate enactment dates randomly across states sampling from a uniform distribution of the actual date set.

In Table 2, we explore whether our mobility measures contain different information using regressions that include two mobility measures at a time. (Not all possible combinations are shown.) The mobility measures are highly correlated (see Table B.4 in Appendix B), and we prefer to include them separately going forward. In particular, the results in column (7) are consistent with multicollinearity: the estimated effect for SG Visits becomes significantly larger, while the estimated effect for the Cuebiq turns negative when the two measures are included together. That said, the results are very similar to our baseline findings and, if anything, the effect of mask mandates is more precisely estimated in these regressions, particularly for deaths.

Table 2.

Mobility, mask mandates, cases and deaths: combining mobility measures.

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Deaths | ||||||||

| Visits | 0.05*** | 0.13*** | 0.21*** | 0.09*** | 0.21*** | 0.35*** | |||

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | ||||

| Home Time | –0.18*** | –0.20*** | –0.15*** | –0.21*** | |||||

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.03) | (0.02) | ||||||

| PlaceIQ | 0.03*** | 0.03*** | −0.01 | 0.00 | |||||

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | ||||||

| Cuebiq | 0.07*** | –0.12*** | |||||||

| (0.01) | (0.02) | ||||||||

| Mask Mandate | –0.05*** | –0.06*** | –0.04*** | –0.02* | –0.08*** | –0.08*** | –0.06*** | –0.09*** | |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | ||

| Adj. R-squared. | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.58 | |

| Obs | 12 110 | 12 110 | 11 637 | 12 110 | 11 046 | 11 046 | 10 759 | 11 046 | |

| State FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Date FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Pop. weights | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

Notes: See notes to Table 1. Not all controls are reported in this table, but are included in the analysis.

We also explore whether mask mandates are more effective in states that have higher levels of mask compliance (based on the aforementioned New York Times survey data) using the following specification:

| (4) |

where denotes compliance as measured in the survey data. Table 3 reports estimates of Eq. (4). The results show that mask mandates are indeed more effective, particularly at slowing down growth in Covid-related deaths, in states where mask compliance is high. Overall, this analysis shows that while on an a priori, scientific basis, face masks may be equally effective everywhere against the transmission of Covid-19, the success of mask mandates might depend on the extent to which the local population is willing to wear them (properly) as instructed (especially around vulnerable people).

Table 3.

Mobility, mask mandates, cases and deaths: compliance.

| Visits |

Home Time |

PlaceIQ |

Cuebiq |

Visits |

Home Time |

PlaceIQ |

Cuebiq |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Deaths | ||||||||

| Lag Mobility | 0.15 | –0.20*** | 0.06 | 0.14*** | 0.13 | –0.16*** | 0.01 | −0.00 | |

| (0.09) | (0.08) | (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.09) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.06) | ||

| Mask Mandate | –0.05* | –0.05* | –0.07** | –0.06* | −0.06 | –0.06 | –0.08* | –0.08* | |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.04) | ||

| Mask Mandate Compliance |

−0.02 | –0.03 | −0.04 | –0.08** | –0.17*** | –0.17*** | –0.19*** | –0.20*** | |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | ||

| Adj. R-squared. | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.59 | 0.61 | |

| Obs | 12 110 | 12 110 | 12 110 | 11 637 | 11 046 | 11 046 | 11 046 | 10 759 | |

| State FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Date FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Pop. weights | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

Notes: Estimation equation (4): where denotes Covid-19 cases/deaths in state at date , measured in days. and denote state fixed effects and time fixed effects, respectively. denotes mobility, and is the lag operator. The mobility measures for the case (death) regressions are averaged over 21 (35) days and lagged 7 (14) days. All mobility measures are standardized for easier interpretation of the coefficients. measures whether a face mask mandate is in place during the time period when mobility is measured. The timing of the mask mandate as well as that of the temperature and the local mobility restrictions controls in match the corresponding mobility averaging and lag structure. denotes mask wearing compliance as measured in the survey data described in Appendix A. Regressions are weighted by state population and use Driscoll–Kraay standard errors. The sample includes all available observations between March 15, 2020 and November 15, 2020. Not all control variables are reported in the table.

4.2. Towards a causal interpretation of the results

Our regression framework is similar to a difference-in-difference (DiD) approach with variation in the timing of treatment, typically estimated via two way fixed effect (TWFE) models. Unlike the TWFE traditional approach, our design includes a lagged mask (treatment) variable that is averaged over several days to match the timing of our controls for mobility, but it is subject to similar criticisms. The modest goal of our analysis is to assess whether mask wearing (facilitated by mask mandates) offsets the effects of mobility on cases (deaths) and to what extent. However, if our estimates are too far from the true average treatment effects of the mask mandates (ATT), our exercise could be uninformative.

The TWFE design is a popular strategy to study the effects of interventions, but certain identifying assumptions are needed for estimating true causal treatment effects. First, a parallel trends assumption is required: the control group should approximate the (counterfactual) traveling path of the treatment group absent the treatment. With endogenous treatment (for example, states with more infections imposing mask mandates but not others), this assumption might be violated. Also, the treatment should affect the treated group in a meaningful way. In our case, a mask mandate in a given state should increase mask wearing in that state relatively more than in other states—a lack of mask mandate does not guarantee residents will not wear masks when cases rises locally or elsewhere due to concerns about their health or other factors. Variation in the timing of the treatment (the date mask mandates went into affect) also creates certain issues.

More technically speaking, as Goodman-Bacon (2021) shows, the TWFE estimator is a weighted average of all possible comparisons between the units included in the regression, which includes the treated and the never treated, the early treated and the late treated, and the late treated compared to the early treated. Some of these comparisons provide “good variation”, while other combinations are not necessarily useful and may lead to incorrect conclusions (especially if the ATTs are constant across units but heterogeneous over time). This section presents a series of exercises aimed at addressing some of these concerns and the related potential biases in our estimates.

Event study analysis.

First, we assess potential violations of the parallel trends assumption in our analysis. To this end, we regress the log of cases (deaths) growth on a set of weekly dummies from four weeks before a mask mandate goes into effect (event time zero) until 10 weeks after. Any observations for treated states before week 4 (day 28) or after week 10 (day 70) are dropped from the regressions, and never treated states are assigned an event time of zero. Thus, we estimate:

| (5) |

This event study estimation approach is based on the one in Kovacs et al. (2020), which draws heavily on prior work by Borusyak et al. (2022). Like those authors, we drop the first and last treatment lead within our estimation window to address issues of under-identification.

Fig. 3 depicts our estimates and shows no differential effects for cases or deaths prior to the enactment of mask mandates. The estimated impact of mask mandates grows over (event) time, and also become noisier, stabilizing around week 5 for cases and a few weeks later for deaths.

Fig. 3.

The Effect of Mask Mandates on Cases and Deaths over Event Time.

Notes: The figure depicts estimates for the coefficients in the regression , where denotes Covid-19 cases (deaths) in state at date , measured in days. and denote state fixed effects and time fixed effects, respectively, and is a dummy equal to one if at time state is weeks before or after the enactment of its mask mandate. Any observations for treated states before week 4 (day 28) or after week 10 (day 70) are dropped from the regressions, and never treated states are assigned an event time of zero. Driscoll–Kraay standard errors. The sample includes all available observations between March 15, 2020 and November 15, 2020 that meet the previous requirements.

The estimates in Fig. 4 incorporate the additional controls from our baseline regressions (mobility, local mobility restrictions, temperature, and lagged counts). The average of the mask mandate effect estimates for weeks 1 to 4 in these event study regressions are similar in magnitude to our baseline results where we average the mask mandate dummy over a 21-day period lagged 7 days relative to the date at which we measure cases growth. The fact that the estimated effects for weeks further away from treatment (mask mandate enactment) reverse back to zero when adding these additional controls likely reflects the fact that mask mandates are correlated with other factors that change over time. For example, states with mask mandates might have also been slower at removing local mobility restrictions, or they experienced voluntary mobility changes or shifts in the weather along with the mask mandates. The raw correlations between mobility (as measured by cellphone pings) and mask mandates is low (see Table B.4 in the Appendix), while the correlation with the local mobility restrictions index is a bit larger, 0.27.18

Fig. 4.

The Effect of Mask Mandates on Cases over Event Time with Additional Controls.

Notes: The figure depicts estimates for the coefficients in the regression , where denotes Covid-19 cases/deaths in state at date , measured in days. and denote state fixed effects and time fixed effects, respectively, and is a dummy equal to one if at time state is weeks before or after the enactment of its mask mandate. denotes mobility, and is the lag operator. The mobility measures for these regressions are averaged over 21 days and lagged 7 days. All mobility measures are standardized for an easier interpretation of the coefficients. includes controls for temperature and a local mobility restrictions index with the timing of these data matching the mobility averaging and lag structure. Any observations for treated states before week 4 (day 28) or after week 10 (day 70) are dropped from the regressions, and never treated states are assigned an event time of zero. Driscoll–Kraay standard errors. The sample includes all valid observations between March 15 and November 15, 2020 that meet the previous requirements.

Figure B.4 in Appendix B presents results for analogous regressions for deaths. When including the additional controls, the effects of mask mandates over event time are more delayed for deaths than for cases (as in Fig. 4), and they are also less precisely estimated. Importantly, some pre-trends are present in the sense that death growth rates seem relatively higher pre-intervention for (treated) states that enacted mask mandates. We address this concern later with a synthetic control approach.

Stacked data analysis.

We also try an approach similar to Cengiz et al. (2019) to address concerns regarding potential heterogeneous treatment effects. For each of our 36 mask-mandate events (enactment dates), we construct a sample that includes the treated (mask mandate) state and a control state for a fixed event time horizon. The control state is the state with the closest rate of new cases per capita to the treated state (just before the treatment occurs) that does not impose a mask mandate during the relevant event-time window. We stack all the event-specific paired samples to calculate an average effect across the events by re-estimating equation (3). This alternative approach uses a more stringent criteria for admissible controls, making the regressions more robust to problems with staggered treatment dates in the presence of heterogeneous treatment effects. Also, since the data are aligned by event time instead of calendar time, the negative weighting problem pointed out by Goodman-Bacon (2021) is less likely to occur. Finally, we address the issue of potential endogeneity around enactment dates to some extent by matching states with similar infection rates around the time that the mask mandate is imposed.19 (We are aware that pre-treatment similarities across states are neither necessary nor sufficient to guarantee parallel counterfactual trends.)

Fig. 5 summarizes the results of this exercise. We plot the estimated coefficient on mask mandates, , from Eq. (3), along with 95 percent confidence intervals. The first point in each plot is our original estimate. The remaining points are estimates from different stacked samples. To begin, the event window for our stacked estimates includes 28 days before and 70 days after the mask mandate passing (Stacked A), which matches the timing of our previously discussed event study analysis. Stacked B and Stacked C use a slightly longer (84 day) and a shorter (56 day) post-treatment period, respectively, which does not impact the estimates much. Stacked D adds event-time FE to the regressions, while Stacked E removes treatment–control pairs from the stacked sample if the difference between new infection rates relative to population between the two states was above a threshold at the time the mask mandate was enacted.20 Finally, in Stacked F we include more than one control state per mask-mandate event as long as the difference in infection rates relative to population between the treated state and the control states is below the same threshold as in Stacked E. These findings suggest that, if anything, we might be underestimating the effect of mask mandates on case growth rates because the stacked regression coefficients tend to be larger (in absolute value) and more precisely estimated. Figure B.5 in Appendix B shows results for analogous regressions for the growth in deaths, which are more precisely estimated using a stacked-sample approach.

Fig. 5.

Robustness of Mask Mandate Estimates for Cases: Stacked Samples.

Notes: Estimates of Eq. (3) for cases with actual data and with alternative stacked samples constructed by matching each state that imposes a mask mandate with another state that does not impose a mask mandate during the respective event window and that has the closest rate of infections relative to population just before the date the event (mask mandate enactment) occurs in the treated state. Stacked A uses an event period of 28/70 days before/after the mask mandate. Stacked B and C use a longer/shorter (84/56 days) post-treatment period. Stacked D adds event-time FE. Stacked E removes treatment–control pairs from the stacked sample, where the difference between new infection rates relative to population between the treated state and the control state is above a threshold (2). Stacked F includes more than one control state per mask-mandate event as long as the difference in infection rates relative to population between the treated state and the control states is below the threshold in Stacked E.

Synthetic cohort analysis.

Synthetic cohort methods (SCMs) are also used frequently to estimate treatment effects of policy interventions (see Abadie and Gardeazabal, 2003, Abadie et al., 2010). A “synthetic control” is a weighted average of untreated “donor pool” units, constructed to match the pre-treatment characteristics of the treated unit. (The method is based on the observation that a combination of units in the donor pool may approximate the characteristics of the treated unit better than any single unit alone). Under some general conditions, the estimated treatment effect on a treated unit post-treatment is the difference between that unit’s outcome and that of its synthetic control. Bias correction methods have also been developed to take into account discrepancies between the predictor variables for each treated unit and its “donor” units (Abadie and L’Hour, 2021, Ben-Michael et al., 2021), and inference typically occurs through calculating p-values based on placebo tests in which treatment status is randomly permuted across untreated units. While originally developed for treatment estimation with a single treated unit, SCMs have been extended to situations with multiple staggered treated units using a stacked or pooled approach (e.g., Abadie and L’Hour, 2021, Dube and Zipperer, 2015, Wiltshire, 2021a). We follow the staggered approach of Dube and Zipperer (2015) and Wiltshire (2021b), which we implement following Wiltshire (2021a).21 The stacked-in-event-time synthetic control estimator we employ is an event-time-specific weighted average of the treatment effects over all treated units.

As with any other method, the choice of predictors (in this case to construct the synthetic cohort) is key. To keep the analysis consistent with our previous estimates, we include mobility measures to construct the synthetic cohort along with factors that likely predict Covid-19 transmission and deaths, including median age in the state, the percent of the population living in urban areas, and pre-pandemic death rates due to flu and pneumonia (in our previous regressions, we included state fixed effects, which accounted for these factors to some extent). For our “donor pool”, we use the 15 states that had not implemented a statewide mask mandate by November 15, 2020.

Fig. 6 presents bias-corrected gap estimate for log of case growth (along with 100 placebo samples) using our four mobility measures. As with our previous estimates, the effect of mask mandates seems to build over time. Still, these results should be interpreted with some caution because, as Figure B.6 in the appendix more clearly shows, the pre-treatment match of treated states with their corresponding synthetic cohort is far from perfect on average. Overall, though, these results reinforce our baseline finding that mask mandates have an offsetting effect on the growth of Covid-19 cases during the early waves of the pandemic.

Fig. 6.

Robustness of Mask Mandate Estimates for Cases: Synthetic Cohorts.

Notes: Estimates using a stacked synthetic cohort method for 21/70 days before/after the mask mandates were enacted.

4.3. Policy counterfactuals

We next explore how more extensive mask mandates could have further mitigated the effect of mobility on the spread of Covid-19. As noted earlier, mask mandates have been implemented at different times and to different degrees across states throughout the pandemic. As of November 15, 2020, only one state, South Dakota, had no reported face-mask requirement of any kind, while 14 states had mask requirements specific to certain locations or businesses (partial mandates). All other states had mandates generally requiring face masks “everywhere in public where social distancing is not possible”.

To better understand the quantitative significance of our estimates, we conduct two counterfactual exercises. First, we predict the total number of Covid-19 cases the United States would have had on November 15, 2020 if mask mandates had been put in place in every state by May 15, 2020.22Fig. 7 (left panel) depicts the evolution of actual and counterfactual cases under this scenario. Our most conservative baseline estimates are those that use SG time at home as our mobility measure. Based on these estimates, the United States would have had 23.7 percent (about 2.62 million) fewer cases as of November 15—a meaningful difference. The analogous numbers for SG visits, PlaceIQ DEX, and Cuebiq CI are 25.6 percent, 30.4 percent, and 30 percent, respectively.23 A later national mask mandate would have prevented fewer cases and consequently fewer deaths, but it still would have been beneficial. Indeed, we estimate that the case count as of November 15, 2020 would have been 3.7 percent lower (about 411,000 fewer cases) if every state had a mask mandate by August 15, 2020. Note that the large difference between this value and the 23.7 percent reduction from a May 15 enactment shows the exponentially large effect of an earlier mask mandate due to the strong persistence that we estimate in the case growth rate. Overall, these results demonstrate the beneficial nature of mask mandates and, implicitly, mask use, especially given that they are a relatively low-cost public health option for helping to control the spread of the virus.

Fig. 7.

Counterfactuals: Mask Mandates versus Restricting Mobility.

Notes: Counterfactuals in these figures use the SafeGraph Home Time measure of mobility. The top panels present total cases, while the bottom panels depict a 7-day rolling average of new daily cases. Two-standard-deviation error bands depicted for the projections.

An earlier national mask mandate put in place on May 15, 2020 would also have had economic benefits associated directly with the reduction in cases. To put a value on this, we examine the state-level relationship between the 7-day (log) change in a 7-day moving average of aggregate hours worked and the corresponding 7-day (log) change in the number of new cases over the previous 14 days, as a proxy of the number of people who are currently sick or isolating and potentially not able to work, controlling for state and time fixed effects.24 The relationship is significantly negative with a 10 log percentage point larger growth rate of new cases correlating with a 0.45 log percentage point lower growth rate of total hours worked at the state level. Based on these estimates and our counterfactual calculation for cases based on the SG time at home mobility measure, a May 15 national mask mandate would have reduced the fall in hours worked from the May–Nov 2019 period to the May–Nov 2020 period by 25 percent. Using counterfactual cases based on specifications featuring the three other mobility measures, this implies a reduction in the fall in hours worked by between 27 and 35 percent.

For our second counterfactual, we predict the number of Covid-19 cases that the United States would have had if mobility in every state had remained fixed at its May 15, 2020 level rather than continuing to recover and the local closure policy restrictions at that time were not relaxed. In this alternative counterfactual, we find that infections on November 15, 2020 would have been 68 percent lower when we use the SG time-at-home mobility measure, 70.1 percent lower using SG visits, 49.1 percent lower using the PlaceIQ DEX, and 57.0 percent lower using the Cuebiq CI. Fig. 7 (right panel) depicts this scenario for SG time at home.25 These results highlight how much mobility contributed to the spread of Covid-19 early in the pandemic, and the counterfactual estimates imply that a May 15, 2020 national mask mandate could have offset up to 35 percent (2.62 million) of the 7.5 million additional cases through November 15, 2020 from the post-May-15 recovery in mobility.

Restricting mobility to its near-lockdown levels of mid-May certainly would have been effective at reducing the number of Covid-19 cases, and ultimately the number of deaths from the disease. Mask mandates, if they had been implemented earlier and across all states, would have been close to a half as effective as lockdowns at reducing the number of Covid-19 infections (and deaths), but they are much less costly for the economy.26 The beneficial effects on economic activity, as measured by hours worked, that result from the reduction in infections alone from either mask mandates or mobility-limiting policies would also have been large. However, in evaluating the total economic effects of these public health interventions, it is important to keep in mind their direct cost on economic activity. It is arguable that, aside from reducing infections, the direct economic effects of mask mandates are small while mobility restrictions have large negative direct effects on the economy. This speaks to the challenge that policymakers faced in determining how best to combat the Covid-19 public health crisis.

5. Conclusion

We find a strong, positive correlation between (lagged) mobility and the growth rate of Covid-19 cases. Mobility is also related to the growth rate of deaths but with a longer lag, as individuals who contract the virus do not succumb immediately due to medical treatment and other factors. While our work is not the first to document the link between mobility and Covid-19 cases and deaths, the novel feature of our analysis is that it considers the role played by masks in counteracting the effect of mobility on the spread of Covid-19 early in the pandemic in a single cohesive framework. Specifically, we exploit substantial variation across US states in the timing of mask mandates and show that these mandates partially offset the impact of increased mobility on the growth rates of Covid-19 cases and deaths. We further find that the effectiveness of mask mandates is greater in states where there was greater compliance (more mask wearing) with the regulations—more mask use may also reflect the influence of other Covid-19-related public health information campaigns in general. In addition, our counterfactual exercises illuminate the close connection between mobility and virus spread as well as the partially offsetting effects of mask mandates.

The widespread shutdown of economic activity both in the US and in Europe in March and April 2020 highlights the important link between mobility and the public health outcomes associated with Covid-19. In spring 2020, decisions were made to severely limit movement in many locations in an effort to slow the spread of the virus and ease the burden on the health-care system. These restrictions entailed severe economic costs and highlighted the trade off between allowing the movement of individuals that is needed to facilitate economic activity and limiting the public health costs of the virus. Our results show that masks, which entail a much lower economic cost than restricting individuals’ mobility, likely helped mitigate the spread of the virus. We acknowledge that our findings are potentially limited in terms of their causal interpretation, particularly our results for deaths, but the analysis in Section 4.2 suggests that the correlations we document between cases and mask mandates could be causal.

While the economy adapted well to the pandemic and economic activity held up better than expected early on, mask wearing was and could continue to be an important part of combating Covid-19 (especially when around vulnerable individuals and in periods of high transmission). Mask mandates in the US were not popular, but educational campaigns aimed at increasing understanding of the benefits of mask wearing, and thus compliance, are likely effective alternatives to limiting mobility during future flare-ups of Covid-19 or other widespread (airborne) viruses. In addition, while not addressed directly by our analysis, the provision of free or subsidized masks of the appropriate kind as well as guidance on proper mask use might be desirable.

Footnotes

Special thanks to Keith Barnatchez, Rachel Cummings, Noah Flater, Nishan Jones, Justin Rohan, and Zorah Zafari for research assistance, and Giovanni Olivei for comments. The views in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System.

While not focused directly on the role of masks, in a relevant paper, Durante et al. (2021) consider the related role of civic values in limiting mobility and the spread of Covid-19 in Italy.

We cannot calculate year-over-year changes for SG time at home because of data vintage changes. See https://readme.safegraph.com/docs/social-distancing-metrics.

Data on the year-over-year change in the CI are available, and we hand-collected them from the Cuebiq website: https://www.cuebiq.com/visitation-insights-contact-index/. Note that Cuebiq does not report data for Alaska or Hawaii.

We cannot calculate year-over-year changes in the state-level DEX with the data available to us, and therefore we use the level of the index in our analysis.

Other measures of mobility show similar patterns over time and across states.

Exceptions include South Dakota during the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally in August 2020, and Louisiana, Maine, Montana, South Dakota, and Wyoming, which saw mobility (based on the SG time-at-home measure) at pre-pandemic levels in early September 2020.

See Appendix A.2 for more information about the New York Times mask-wearing data.

We measure climate change beliefs based on the proportion of people who responded affirmatively to the following question from the Yale Climate Opinion Survey: “Assuming global warming is happening, do you think it is caused mostly by human activities?” Voting data come from the MIT Election Lab Database. See the appendix for more details on these data.

Previous studies that document the relationship between political beliefs and compliance with lockdown policies and mask mandates include Brzezinski et al. (2020), Milosh et al. (2021), and Welsch (2020).

This specification is similar to the one used in Orea and Álvarez (2022) who study the effectiveness of Spain’s lockdown in battling the spread of Covid-19.

The addition of the lagged dependent variable greatly improves the fit of the regression.

We start at 7 because early variants of the virus seemed to have had a longer incubation period than the later ones (see Wu et al., 2022 for further details). Another reason for not starting with shorter lags is to avoid the possible feedback from cases to mobility that we abstract from in this paper.

See Dave et al. (2021) for a study of the impact of shelter-in-place orders on public health in the US, with a focus on the heterogeneity of their effects, or Amuedo-Dorantes et al. (2021) for an analysis of the impact of such orders in Spain.

Clustering standard errors by state instead does not change our inference.

We also experimented with variants of the log transformation, such as adding 1 to the number of new cases or to the growth rate of cases itself, and obtained similar results to our main findings.

The number of observations is different across mobility measures because Cuebiq does not collect data for Alaska and Hawaii.

The low correlation between mobility and mask mandates is consistent with the findings in Kovacs et al. (2020) using data from Germany.

Cengiz et al. (2019) do not match treated and control states based on pre-treatment characteristics, but instead include all possible control states for each treated event instead. We do not follow suit and use all possible control states in our analysis because in our case we do not necessarily expect the parallel trends assumption to hold vis-à-vis all control states.

We chose a threshold of 2 cases per 100,000 population, which is roughly the 75th percentile of the difference in new infection rates at time of enactment in our initial stacked sample between treatment–control pairs. In 12 (9) of the 36 events, the difference in new infection rates relative to population between treated and control state was above 2 (5), and in 21 cases the difference was below 1.

We also gained relevant insight into using synthetic control estimators for studying the impact of different factors on Covid-19 infection rates from Breidenbach and Mitze (2021) and Mitze et al. (2020).

We detail our approach and calculations in Appendix C. For states that implemented their mandates earlier than May 15, 2020, we use the actual mandate dates.

The counterfactual for PlaceIQ DEX is estimated as of November 11, 2020—the latest date possible given the data available to us at the time of the analysis. The percent fewer cases for November 15, 2020 would be slightly higher.

We use hours worked data from Homebase. See Appendix A.2 for additional details on these data.

If only mobility (and not local closure policies) remained fixed at its May 15, 2020 level in all states, the counterfactual number of infections on November 15, 2020 would have been 65.7 percent lower based on the SG time-at-home mobility measure. The analogous numbers for SG visits, PlaceIQ DEX, and Cuebiq CI are 67.9 percent, 34 percent, and 47.3 percent, respectively. This suggests that “voluntary” mobility rather than mobility restrictions were more tightly linked to case growth.

The estimated effectiveness of mask mandates relative to reductions in mobility varies with the mobility measure and ranges from 34.8 percent as effective for SG time at home to 62 percent as effective for PlaceIQ DEX. The average relative effectiveness across our four estimates is roughly 47 percent.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2022.101195.

Appendix A. Data sources and additional estimates

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abadie Alberto, Diamond Alexis, Hainmueller Jens. Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of California’s Tobacco control program. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 2010;105(490):493–505. URL http://www.jstor.org/stable/29747059. [Google Scholar]

- Abadie Alberto, Gardeazabal Javier. The economic costs of conflict: A case study of the basque country. Amer. Econ. Rev. 2003;93(1):113–132. doi: 10.1257/000282803321455188. URL https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/000282803321455188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abadie Alberto, L’Hour Jérémy. A penalized synthetic control estimator for disaggregated data. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 2021;116(536):1817–1834. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2021.1971535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amuedo-Dorantes Catalina, Borra Cristina, Rivera-Garrido Noelia, Sevilla Almudena. Early adoption of non-pharmaceutical interventions and COVID-19 mortality. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2021;42 doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2021.101003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker Rachel, Yang Wenchang, Vecchi Gabriel A., Metcalf C.Jessica E., Grenfell Bryan T. Assessing the influence of climate on wintertime SARS-Cov2 outbreaks. Nature Commun. 2021;12(826) doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-20991-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baqaee David, Farhi Emmanuel, Mina Michael, Stock James H. Policies for a Second Wave. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 2020 URL https://www.brookings.edu/bpea-articles/policies-for-a-second-wave/ [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Michael Eli, Feller Avi, Rothstein Jesse. The augmented synthetic control method. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 2021;116(536):1789–1803. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2021.1929245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borusyak Kirill, Jaravel Xavier, Spiess Jann. 2022. Revisiting event study designs:Robust and efficient estimation. Available at SSRN: https://Ssrn.Com/Abstract=2826228. [Google Scholar]

- Breidenbach Philipp, Mitze Timo. Large-scale sport events and COVID-19 infection effects: evidence from the German professional football ‘experiment’. Econom. J. 2021;25(1):15–45. doi: 10.1093/ectj/utab021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski Adam, Kecht Valentin, Dijcke David Van, Wright Austin L. University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics; 2020. Belief in Science Influences Physical Distancing in Response to COVID-19 Lockdown Policies: Working Paper 2020–56. URL https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3587990. [Google Scholar]

- Bundgaard Henning, Bundgaard Johan Skov, Raaschou-Pedersen Daniel Emil Tadeusz, von Buchwald Christian, Todsen Tobias, Norsk Jakob Boesgaard, Pries-Heje Mia M., Vissing Christoffer Rasmus, Nielsen Pernille B., Winslw Ulrik C., Fogh Kamille, Hasselbalch Rasmus, Kristensen Jonas H., Ringgaard Anna, Andersen Mikkel Porsborg, Goecke Nicole Bakkegård, Trebbien Ramona, Skovgaard Kerstin, Benfield Thomas, Ullum Henrik, Torp-Pedersen Christian, Iversen Kasper. Effectiveness of Adding a Mask Recommendation to Other Public Health Measures to Prevent SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Danish Mask Wearers. Ann. Internal Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-6817. URL https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33205991/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cengiz Doruk, Dube Arindrajit, Lindner Attila, Zipperer Ben. The Effect of Minimum Wages on Low-Wage Jobs. Q. J. Econ. 2019;134(3):1405–1454. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Vincent CC, Wong Shuk-Ching, Chuang Vivien WM, So Simon YC, Chen Jonathan HK, Sridhar Siddharth, To Kelvin KW, Chan Jasper FW, Hung Ivan FN, Ho Pak-Leung, et al. The Role of Community-Wide Wearing of Face Mask for Control of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Epidemic due to SARS-CoV-2. J. Infection. 2020;81(1):107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.024. URL https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32335167/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernozhukov Victor, Kasahara Hiroyuki, Schrimpf Paul. Causal Impact of Masks, Policies, Behavior on Early Covid-19 Pandemic in the U.S. J. Econometrics. 2020;220(1):23–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.09.003. URL http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304407620303468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave Dhaval, Friedson Andrew I., Matsuzawa Kyutaro, Sabia Joseph J. When Do Shelter-In-Place Orders Fight Covid-19 Best? Policy Heterogeneity Across States And Adoption Time. Econ. Inq. 2021;59(1):29–52. doi: 10.1111/ecin.12944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydiuk, Tetiana, Gupta, Deeksha, 2020. Income Inequality, Debt Burden and COVID-19. Working paper, Available at SSRN:.

- Desmet Klaus, Wacziarg Romain. JUE Insight: Understanding spatial variation in COVID-19 across the United States. J. Urban Econ. 2022;127 doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2021.103332. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094119021000140, JUE Insights: COVID-19 and Cities. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube Arindrajit, Zipperer Ben. IZA; 2015. Pooling Multiple Case Studies Using Synthetic Controls: An Application to Minimum Wage Policies. URL https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2589786. [Google Scholar]

- Durante Ruben, Guiso Luigi, Gulino Giorgio. Asocial capital: Civic culture and social distancing during COVID-19. J. Publ. Econ. 2021;194(104342):1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyke Miriam E. Van, Rogers Tia M., Pevzner Eric, Satterwhite Catherine L., Shah Hina B., Beckman Wyatt J., Ahmed Farah, Hunt D. Charles, Rule John. Trends in County-Level COVID-19. Incidence in Counties With and Without a Mask Mandate—Kansas, June 1–August 23, 2020. Morbidity Mortal. Weekly Rep. 2020;69(47):1777–1781. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6947e2. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6947e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani Diego, Dickson Maria Michela, Espa Giuseppe. Modelling and Predicting the Spatio-Temporal Spread of COVID-19 in Italy. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020;20(700) doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05415-7. 10.1186/s12879-020-05415-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman-Bacon Andrew. Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. J. Econometrics. 2021;225(2):254–277. [Google Scholar]

- IHME Forecasting Team Modeling COVID-19 Scenarios for the United States. Nat. Med. 2020 URL https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-020-1132-9. [Google Scholar]

- Karaivanov Alexander, Lu Shih En, Shigeoka Hitoshi, Chen Cong, Pamplona Stephanie. Face Masks, Public Policies and Slowing the Spread of COVID-19: Evidence from Canada. J. Health Econ. 2021;78 doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2021.102475. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167629621000606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissler Stephen M., Tedijanto Christine, Goldstein Edward, Grad Yonatan H, Lipsitch Marc. Projecting the Transmission Dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the Postpandemic Period. Science. 2020:860–868. doi: 10.1126/science.abb5793. URL https://science.sciencemag.org/content/368/6493/860.full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosfeld Reinhold, Mitze Timo, Rode Johannes, Wälde Klaus. The Covid-19 containment effects of public health measures: A spatial difference-in-differences approach. J. Reg. Sci. 2021;61(4):799–825. doi: 10.1111/jors.12536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs Roxanne, Dunaiski Maurice, Tukianen Janne. 2020. Compulsory face mask policies do not affect community mobility in Germany. Available at SSRN: https://Ssrn.Com/Abstract=3620070. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu Wei, Wehby George. Community Use of Face Masks and COVID-19: Evidence From a Natural Experiment of State Mandates in the US. Health Affairs. 2020;39(8):1419–1425. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00818. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milosh Maria, Painter Marcus, Sonin Konstantin, Van Dijcke David, Wright Austin L. Unmasking Partisanship: Polarization Undermines Public Response to Collective Risk. J. Publ. Econ. 2021;204 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104538. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047272721001742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitze Timo, Kosfeld Reinhold, Rode Johannes, Wälde Klaus. Face masks considerably reduce COVID-19 cases in Germany. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117:32293–32301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2015954117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouvellet P., Bhatia S., Cori A., et al. Reduction in mobility and COVID-19 transmission. Nature Commun. 2021;12(44):1090. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21358-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orea Luis, Álvarez Inmaculada C. How Effective Has the Spanish Lockdown Been to Battle COVID-19? A spatial Analysis of the Coronavirus propagation across provinces. Health Econ. 2022;31(1):154–173. doi: 10.1002/hec.4437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlossser Frank, Maier Benjamin F., Jack Olivia, Hinrichs David, Zachariae Adrian, Brockmann Dirk. COVID-10 lockdown induces disease-mitigating structural changes in mobility networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117(52):32883–32890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2012326117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsch David M. Do Masks Reduce COVID-19 Deaths? A County-Level Analysis using IV. Covid Econ. 2020;57(13):20–45. URL https://cepr.org/content/covid-economics. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson Daniel J. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco; 2020. Weather, Social Distancing, and the Spread of COVID-19: Working Paper 2020–23. URL https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/2020/23/ [Google Scholar]

- Wiltshire, Justin C., 2021a. allsynth: Synthetic Control Bias-Correction Utilities for Stata. Working Paper, URL.

- Wiltshire, Justin C., 2021b. Walmart Supercenters and Monopsony Power: How a Large, Low-Wage Employer Impacts Local Labor Markets. Working Paper, URL.

- Wu Yu, Kang Liangyu, Guo Zirui, Liu Jue, Liu Min, Liang Wannian. Incubation Period of COVID-19 Caused by Unique SARS-CoV-2 Strains: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 2022;5(8):e2228008. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.28008. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.28008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Chenfeng, Hu Songhua, Yang Mofeng, Luo Weiyu, Zhang Lei. Mobile device data reveal the dynamics in a positive relationship between human mobility and Covid-19 infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117(44):27087–27089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010836117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Further Reading

- Couture Victor, Dingel Jonathan I., Green Allison, Handbury Jessie, Williams Kevin R. JUE insight: Measuring movement and social contact with smartphone data: A real-time application to COVID-19. J. Urban Econ. 2022;127 doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2021.103328. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094119021000103, JUE Insights: COVID-19 and Cities. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurmann André, Lalé Etienne, Ta Lien. LeBow College of Business, Drexel University; 2021. The Impact of COVID-19 on Small Business Dynamics and Employment: Real-time Estimates With Homebase Data: School of Economics Working Paper Series 2021–15. URL https://ideas.repec.org/p/ris/drxlwp/2021_015.html. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.