Abstract

Background

Endometriosis is now considered to be a systemic disease rather than a disease that primarily affects the pelvis. Dienogest (DNG) has unique advantages in the treatment of endometriosis, but it also has side effects. Alternatively, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has been used for over 2000 years in the treatment and prevention of disease and growing numbers of Chinese scholars are experimenting with the combined use of Dienogest and TCM for endometriosis treatment.

Objectives

This review evaluated the efficacy and safety of TCM in combination with Dienogest in the treatment of endometriosis through meta-analysis.

Methods

MEDLINE, Embase, the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Journal Integration Platform, and Wanfang were used in literature searches, with a deadline of May 31, 2022. Literature quality was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration “risk of bias” (ROB2) tool, and the “meta” package of R software v.4.1 was used for meta-analysis. Dichotomous variables and continuous variables were assessed using the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI); standard mean differences (MD) and 95% CI, respectively.

Results

Twelve human randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and one retrospective study, all 13 written in the Chinese language, were included in the meta-analysis (720 experiments and 719 controls). The result indicated that TCM plus Dienogest was superior to Dienogest/TCM alone in increasing the cure rates (RR = 1.3780; 95% CI, 1.1058, 1.7172; P = 0.0043), remarkable effect rate (RR = 1.3389; 95% CI, 1.1829, 1.5154; P < 0.0001), invalid rate (RR = 0.2299; 95% CI, 0.1591, 0.3322; P < 0.0001), and rate of adverse effects (RR = 0.6177; 95% CI, 0.4288, 0.8899; P = 0.0097). The same conclusion was drawn from the subgroup analysis.

Conclusion

Results suggest that TCM combined with Dienogest is superior to Dienogest or TCM alone and can be used as a complementary treatment for endometriosis. TCMs have potential to improve clinical efficacy and reduce the side effects of Dienogest. This study was financially supported by Annual Science and Technology Steering Plan Project of Zhuzhou. PROSPERO has registered our meta-analysis as CRD42022339518 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/record_email.php).

Keywords: endometriosis, dienogest, traditional Chinese medicine, meta-analysis, review

Introduction

Historically, endometriosis was thought to involve the growth of endometrial tissue outside of the uterus, typically on the lining of the pelvic cavity (peritoneum) or on the ovaries (1). However, this description is outdated and no longer reflects the true extent and manifestation of the disease. It is now considered to be a systemic disease rather than a disease that primarily affects the pelvis. For example, it can affect metabolism of the liver and adipose tissue, causing systemic inflammation and altering gene expression in the brain, leading to pain sensitivity and mood disorders (2). Endometriosis can be divided into different types, including ovarian endometriosis, peritoneal endometriosis, and deep endometriosis (3). Endometriomas are the most common form of the disease, occurring in 25%–35% of patients with endometriosis (4). It commonly occurs in association with retrograde menstruation, which usually results in endometrial tissue growing outside the uterine body (5). Treatment for endometriosis includes surgery, medical therapy, and assisted reproductive technology (ART) (6). While surgical resection of endometriotic lesions is considered the standard therapeutic approach in symptomatic endometriosis, recurrence of the disease and symptoms following surgery is common and often requires repeated surgery (7). The pharmacological treatment of endometriosis to achieve maintenance includes GnRH agonists, steroid contraceptives, progestins (orally and intrauterine), and aromatase inhibitors (8). As research progresses, the current view is that medication should be the primary treatment option for patients with pelvic pain who have no immediate desire to conceive; for specific infertility patients, assisted reproductive technology can be performed without surgery (6). In spite of the numerous health implications of endometriosis and extensive research efforts, current medical treatments such as GnRH analogs, oral contraceptives, and progestins are often ineffective or cause significant side effects (9). In the absence of long-term treatment with safe medication, recurrence can necessitate hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy (10).

Dienogest (DNG), a 19-nortestosterone derivative, has good bioavailability and a strong progestational effect because of its high selectivity by progesterone receptors (11). A growing body of research has demonstrated the unique advantages of DNG in the treatment of endometriosis: Patients treated with DNG after conservative surgery for endometriosis had a significantly lower risk of postoperative disease recurrence than those with expecting treatment (12); long-term use of DNG for rectosigmoid endometriosis can relieve symptoms (13); a significant increase in improvement in endometriosis lesions, pain symptoms, and quality of life were found in women taking DNG compared to women on continuous combined oral contraceptives (14); it is also an effective drug for controlling the pain symptoms associated with deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE), even without reducing the volume of DIE nodules (15); it can be used for a long time and is well tolerated (16). DNG has therefore been recommended as an alternative method of controlling symptoms associated with endometriosis (17) and as maintenance therapy for patients with endometriosis to reduce the rate of disease recurrence after conservative surgery (18). However, the most common side effects of using DNG include irregular vaginal bleeding, weight gain, and headaches (19).

Chinese medicine is a collective term for traditional Chinese medicines derived from plants, animals, minerals, and their finished products, as well as modern medicines produced with modern technology under the guidance of Chinese medical theory (20). These include traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) or TCM formulas, and have been used to treat and prevent diseases for over 2000 years (21). In China, TCM has gained growing popularity and includes not just single herbs, but Chinese medicinal compounds, Chinese patent medicines (CPMs), and acupuncture (22). The most popular application of TCM is Chinese herbal medicine (CHM), which consists of sliced herbs and Chinese patented drugs (23). It is usually prepared as a formula by unique methods using a combination of herbs (24). CPMs are widely used as a substitute and adjuvant to western medicines (25). They are one of the most important parts of TCM used in clinical practice as derivatives of Chinese herbal medicine (26). Modern pharmacological research has led to the use of greater numbers of Chinese medicine extracts in modern pharmaceutical preparations, including oral CPM (OCPM) and Chinese medicine injection (27). In traditional CPM (TCPM), Chinese medicines are used as raw materials; the product is then created based on the prescription and preparation technology to prevent and treat disease (28). TCM is an alternative treatment for endometriosis in China owing to its significant therapeutic effect and low toxicity (29, 30). Greater numbers of Chinese scholars are now experimenting with the combined use of DNG and TCM for the treatment of endometriosis.

Therefore, this review set out to evaluate the efficacy and safety of TCM in combination with DNG in the treatment of endometriosis through a meta-analysis to provide evidence for its use in clinical practice.

Materials and methods

Data sources and search strategy

MEDLINE, Embase, the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Journal Integration Platform (VIP), and Wanfang were utilized to perform the literature search. Publication was limited to English and Chinese. The time deadline was May 31, 2022. The retrieval strategy was based on subject words and free words and the search terms: (Endometriosis OR Endometrioses OR Endometrioma OR Endometriomas) AND (Chinese Traditional Medicine OR Chinese herbal drugs OR Chinese Plant Extracts or Zhong Yi Xue) AND (Dienogest OR STS-557) were used as keywords.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used: the intervention group was treated with a combination of TCM and DNG, and the control group was treated with TCM or DNG alone, in studies with similar hypotheses and study methods; studies with years of conduct or publication; studies with clearly defined sample sizes; studies with clear criteria for patient selection and case diagnosis, and clear measures of intervention and control; count information available as OR/RR or calculated from the number of cases in the sample and the number of incidences, and measure information available as mean, standard deviation, and sample size. Exclusion criteria included: duplicate reporting; flawed study design and poor quality; incomplete data and unclear outcome effects; incorrect statistical methods that could not be corrected; OR/RR, number of sample cases and number of incidence cases not available for count data or when the mean, standard deviation, and sample size were not available for measure data. Case reports, pedigree studies, case series, editorials, reviews, expert opinions, animal studies, and meta-analyses were also excluded in the present meta-analysis. Research abstracts were independently reviewed by two researchers, and eligible literature was intensively read for further study.

Data extraction

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, two investigators (YW and YL) independently selected the literature. Extractions included general information such as first author, publication year, and number of participants in the treatment group and control group, age, course of disease, and outcomes of patients. There were two types of outcome indicators, one for dichotomous variables and one for continuous variables. The former included the rates of treatment effect, the rate of adverse effects; the latter included estradiol (E2), progesterone (P), luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), cancer antigen 125(CA-125), cancer antigen 199(CA-199), matrix metalloproteinase 2(MMP-2), matrix metalloproteinase 9(MMP-9), Galectins-3(Gal-3), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), cyst size, visual Analogue Scale/Score (VAS), ovulation recovery time, menses recovery time, and recurrence rate. However, the main outcome indicators assessed were the rates of treatment effect and the rate of adverse effects. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion and, if necessary, by engaging a third senior author (HJ).

Quality assessment

For the assessment of literature quality, using the Cochrane Collaboration “risk of bias” (ROB2) tool, we assessed ROB. Two researchers independently (YW and YL) evaluated the quality of the literature. Five bias domains were included: randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, selection of the reported result, and overall bias.

Statistical analysis

R software v.4.1 was used for data analysis, and the “meta” package (31) for meta-analysis. To evaluate dichotomous variables, we used the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). For continuous variables, we used the standard mean differences (MD) and 95% CI. Using I2 statistics, we checked the degree of statistical heterogeneity among the included studies in accordance with the guide judgment I2 < 50% indicating low heterogeneity whereas I2 > 50% reflected obvious heterogeneity. If the I2 statistic was >50%, then a random-effects model was used. Otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used. Analyses of subgroups were performed using the Q-test for heterogeneity. The leave-one-out method was used to determine sensitivity.

Results

Literature inclusion

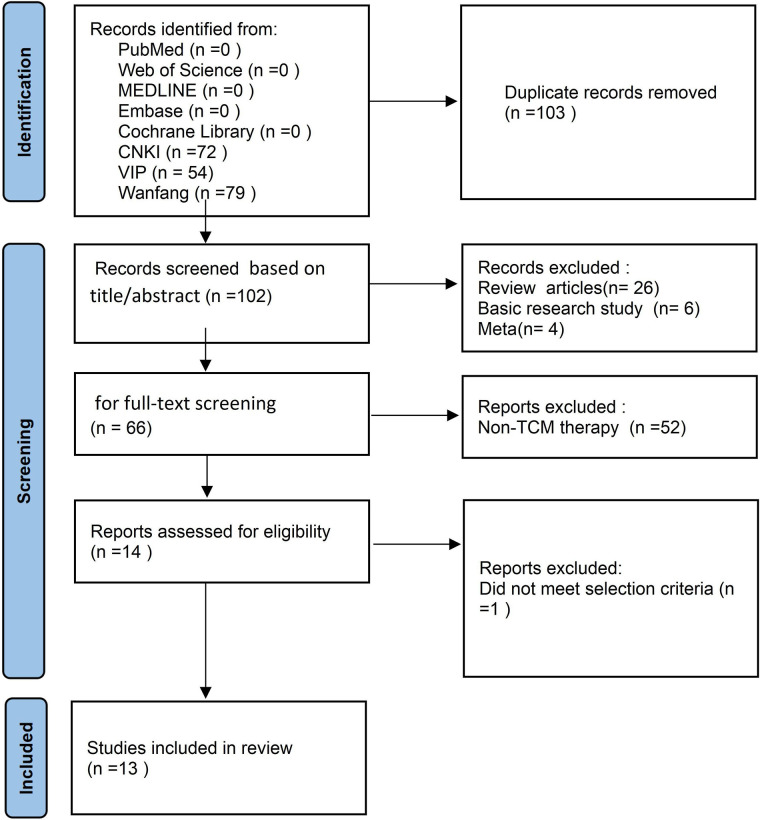

The flow diagram for PRISMA search and selection of literature is shown in Figure 1. A total of 205 articles were identified in the initial search. Of these, 102 articles remained after removing duplicates. We excluded 36 irrelevant articles based on title and abstract screening. Following a review of the full text of the publications, 52 publications were excluded because they were not treated with TCM, another one publication was excluded because it was a comparative study between DNG and TCM.

Figure 1.

The workflow of this study.

As a result, 12 RCTs and one retrospective study, all in the Chinese language, were included in the meta-analysis (720 experiments and 719 controls). Of these studies, four involved Gui Zhi Fu Ling capsules/wan combined with DNG, three involved Gui'e lengwu decoction combined with DNG, three involved CHM combined with DNG (one of the CHMs has a composition similar to that of Gui'e lengwu decoction), and each of San Jie Zhen Tong capsules, Kuntai capsule, Jingtong yushu granule combined with DNG treatment, respectively. Table 1 displays the characteristics of the included studies. Table 2 shows the levels of outcome indicators in the two groups before treatment. In general, there were no statistically significant baseline differences between the intervention and control groups (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Research Type | Sample size (EG/CG) | Agea | Course of Diseasea | Experiment | Control | Duration (months) | Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EG | CG | EG | CG | |||||||

| ZJ (2021) (32) | RCT | 43/43 | 34.28 ± 4.76 | 34.15 ± 4.72 | 4.31 ± 0.57 | 4.4 ± 0.59 | DNG + JTYS | DNG | 6 | EP,VAS |

| WQF (2021) (33) | RCT | 30/30 | 38.55 ± 3.43 | 38.62 ± 3.35 | 8.43 ± 2.58 | 8.23 ± 2.12 | DNG + GZFL | GZFL | 3 | EP,E2,P,LH,FSH,CA125,CA199,MPP2,Gal-3,VEGF |

| DLL (2021) (34) | RCT | 47/47 | 38.62 ± 3.37 | 38.57 ± 3.42 | 8.57 ± 2.36 | 8.65 ± 2.43 | DNG + SJZT | SJZT | 6 | EP,E2,P,LH,FSH,CA125,MPP2,Gal-3,VEGF,MPP9 |

| ZYH (2015)b (35) | RCT | 63/63 | 23.1 ± 4.9 | 22.0 ± 4.1 | DNG + TCM | DNG | 6 | EP,ORT,MRT,RR | ||

| MD (2017) (36) | RCT | 40/40 | 33.97 ± 6.43 | 33.51 ± 6.82 | 22.58 ± 19.84 | 22.12 ± 19.45 | DNG + GELW | DNG | 3 | EP,CA125,CS |

| WM (2019) (37) | RCT | 85/85 | 35.3 ± 2.6 | 36.8 ± 2.5 | 5.3 ± 1.7 | 6.2 ± 1.5 | DNG + GELW | DNG | 6 | EP,CA125,CS,VAS |

| TYY (2021) (38) | RCT | 50/50 | 28.5 ± 5.2 | 28.4 ± 5.4 | DNG + GZFL | DNG | 3 | EP,E2,P,LH,FSH,MPP2,Gal-3,MPP9 | ||

| BXH (2020) (39) | RCT | 53/53 | 31.7 ± 2.6 | 31.2 ± 2.8 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.8 | DNG + GELW | DNG | 6 | EP,CA125,CS,VAS |

| LN (2020) (40) | RCT | 88/87 | 29.04 ± 6.31 | 28.93 ± 6.37 | 11.94 ± 3.13 | 12.05 ± 2.98 | DNG + GZFL | DNG | 3 | EP,E2,P,LH,FSH,CA125,CA199,MPP2,Gal-3,VEGF,MPP9,CS,VAS |

| JX (2021) (41) | RCT | 88/89 | 28.87 ± 4.67 | 29.01 ± 4.16 | 5.87 ± 1.02 | 5.02 ± 1.44 | DNG + TCM | DNG | 6 | EP,ORT,MRT,RR |

| ZWX (2021) (42) | RCT | 38/37 | 31.87 ± 5.49 | 31.95 ± 5.30 | 3.14 ± 0.52 | 3.21 ± 0.48 | DNG + TCM | DNG | 3 | EP,CA125,CA199,CS,VAS |

| ZYY (2021) (43) | RCT | 30/30 | 36.5 ± 1.1 | 36.1 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | DNG + GZFL | DNG | 3 | E2,P,LH,FSH,CS,VAS |

| LDP (2022) (44) | RET | 65/65 | 29.62 ± 5.38 | 29.53 ± 6.47 | 1.25 ± 0.25 | 1.25 ± 0.75 | DNG + KT | DNG | 1 | E2,LH,FSH,CA125 |

RCT, randomized controlled trial; RET, retrospective study; DNG, Dienogest; EG, experiment group; CG, control group; EP, effective percentage; E2, estradiol; P, progesterone; LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulatinghormone; CA125, cancer antigen 125; CA199, cancer antigen 199; MPP2, matrix metalloproteinase 2; MPP9, matrix metalloproteinase 9; Cal-3, Galectins-3; VEGF, Vascular endothelial growth factor; CS, Cystic size; VAS, visual Analogue Scale/Score; ORT, oviating recovery time; MRT, menses recovery time; RR, recurernce rate; JTYS, Jingtongyushu granule; GZFL, Guizhifuling capsule/wan; SJZT, Sanjiezhentong capsule; TCM, Chinese traditional medicine; GELW, Guielengwu decoction; KT, Kuntai capsule.

There was no statistical difference between the two groups.

Surgical treatment.

Table 2.

Comparison of indicators before treatment.

| Index | Author (year) | Experiment | Control | Sample size (EG/CG) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | S | X | S | Model | I 2 | P | |||

| E2 (pmol/L) | WQF (2021) | 169.88 | 17.56 | 170.02 | 16.98 | 30/30 | Fixed | 0.0% | 0.7103 |

| DLL (2021) | 170.69 | 17.71 | 170.81 | 17.68 | 47/47 | ||||

| TYY (2021) | 172.12 | 16.78 | 172.57 | 16.34 | 50/50 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 170.79 | 17.79 | 171.76 | 17.85 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZYY (2021) | 170.78 | 17.74 | 171.74 | 17.83 | 30/30 | ||||

| LDP (2022) | 344.25 | 70.46 | 344.42 | 70.33 | 65/65 | ||||

| P (nmol/L) | WQF (2021) | 0.84 | 0.19 | 0.85 | 0.2 | 30/30 | Fixed | 0.0% | 0.5479 |

| DLL (2021) | 0.85 | 0.24 | 0.86 | 0.18 | 47/47 | ||||

| TYY (2021) | 0.94 | 0.23 | 0.93 | 0.24 | 50/50 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 0.87 | 0.22 | 0.84 | 0.25 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZYY (2021) | 0.85 | 0.19 | 0.82 | 0.21 | 30/30 | ||||

| LH (IU/L) | WQF (2021) | 6.42 | 1.69 | 6.39 | 1.72 | 30/30 | Fixed | 0.0% | 0.9209 |

| DLL (2021) | 6.41 | 1.72 | 6.42 | 1.69 | 47/47 | ||||

| TYY (2021) | 7.56 | 1.89 | 7.47 | 1.91 | 50/50 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 6.29 | 1.79 | 6.39 | 1.95 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZYY (2021) | 6.27 | 1.78 | 6.37 | 1.93 | 30/30 | ||||

| LDP (2022) | 8.25 | 2.74 | 8.33 | 2.62 | 65/65 | ||||

| FSH (IU/L) | WQF (2021) | 6.74 | 2.22 | 6.73 | 2.19 | 30/30 | Fixed | 0.0% | 0.8343 |

| DLL (2021) | 6.73 | 2.19 | 6.71 | 2.17 | 47/47 | ||||

| TYY (2021) | 6.75 | 2.01 | 6.81 | 1.98 | 50/50 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 6.51 | 2.29 | 6.74 | 2.23 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZYY (2021) | 6.49 | 2.27 | 6.72 | 2.21 | 30/30 | ||||

| LDP (2022) | 12.15 | 2.82 | 12.33 | 2.77 | 65/65 | ||||

| CA125 (IU/ml) | WQF (2021) | 72.39 | 13.68 | 73.67 | 13.55 | 30/30 | Fixed | 0.0% | 0.4584 |

| DLL (2021) | 72.41 | 13.75 | 73.53 | 13.24 | 47/47 | ||||

| MD (2017) | 71.56 | 22.95 | 72.24 | 19.32 | 40/40 | ||||

| WM (2019) | 72.36 | 13.84 | 75.49 | 10.54 | 85/85 | ||||

| BXH (2020) | 73.68 | 13.44 | 74.14 | 13.25 | 53/53 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 60.29 | 7.54 | 59.85 | 6.78 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZWX (2021) | 73.42 | 11.65 | 74.85 | 12.03 | 38/37 | ||||

| LDP (2022) | 46.65 | 15.25 | 46.32 | 15.44 | 65/65 | ||||

| CA199 (IU/ml) | WQF (2021) | 61.81 | 7.45 | 61.76 | 7.52 | 30/30 | Fixed | 0.0% | 0.8220 |

| LN (2020) | 61.79 | 7.41 | 62.15 | 7.39 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZWX (2021) | 75.08 | 12.16 | 74.86 | 11.98 | 38/37 | ||||

| MPP2 (µg/L) | WQF (2021) | 225.74 | 42.53 | 226.12 | 43.75 | 30/30 | Fixed | 0.0% | 0.9232 |

| DLL (2021) | 226.85 | 42.67 | 227.12 | 46.43 | 47/47 | ||||

| TYY (2021) | 228.13 | 47.12 | 227.99 | 47.45 | 50/50 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 228.54 | 48.35 | 227.13 | 48.76 | 88/87 | ||||

| Gal-3 (ng/L) | WQF (2021) | 7.91 | 3.65 | 7.92 | 3.57 | 30/30 | Fixed | 0.0% | 0.9691 |

| DLL (2021) | 7.85 | 3.57 | 7.82 | 3.63 | 47/47 | ||||

| TYY (2021) | 7.93 | 2.42 | 8.01 | 2.24 | 50/50 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 7.95 | 3.72 | 7.81 | 3.64 | 88/87 | ||||

| VEGF (pg/ml) | WQF (2021) | 166.58 | 112.43 | 165.64 | 110.87 | 30/30 | Fixed | 0.0% | 0.9744 |

| DLL (2021) | 166.75 | 113.24 | 166.57 | 111.98 | 47/47 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 166.63 | 114.95 | 167.84 | 114.28 | 88/87 | ||||

| MPP9 (ng/L) | DLL (2021) | 941.53 | 343.64 | 942.47 | 321.85 | 47/47 | Fixed | 0.0% | 0.9890 |

| TYY (2021) | 936.12 | 340.23 | 937.01 | 339.57 | 50/50 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 939.53 | 339.21 | 937.45 | 341.73 | 88/87 | ||||

| Diameter (cm) | MD (2017) | 3.62 | 0.84 | 3.59 | 0.98 | 40/40 | Fixed | 0.0% | 0.0851 |

| WM (2019) | 3.98 | 0.74 | 3.71 | 0.83 | 85/85 | ||||

| BXH (2020) | 3.94 | 0.82 | 3.88 | 0.84 | 53/53 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 3.13 | 0.47 | 3.07 | 0.48 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZWX (2021) | 3.41 | 0.56 | 3.43 | 0.52 | 38/37 | ||||

| ZYY (2021) | 3.12 | 0.45 | 3.05 | 0.46 | 30/30 | ||||

| VAS | ZJ (2021) | 5.46 | 0.54 | 5.51 | 0.56 | 43/43 | Fixed | 0.0% | 0.6645 |

| WM (2019) | 8.36 | 1.51 | 8.12 | 1.43 | 85/85 | ||||

| BXH (2020) | 8.14 | 1.46 | 8.17 | 1.37 | 53/53 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 6.03 | 1.16 | 5.95 | 1.08 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZWX (2021) | 7.06 | 1.45 | 6.95 | 1.52 | 38/37 | ||||

| ZYY (2021) | 6.01 | 1.14 | 5.93 | 1.06 | 30/30 | ||||

VAS, visual analogue scale.

Quality assessment

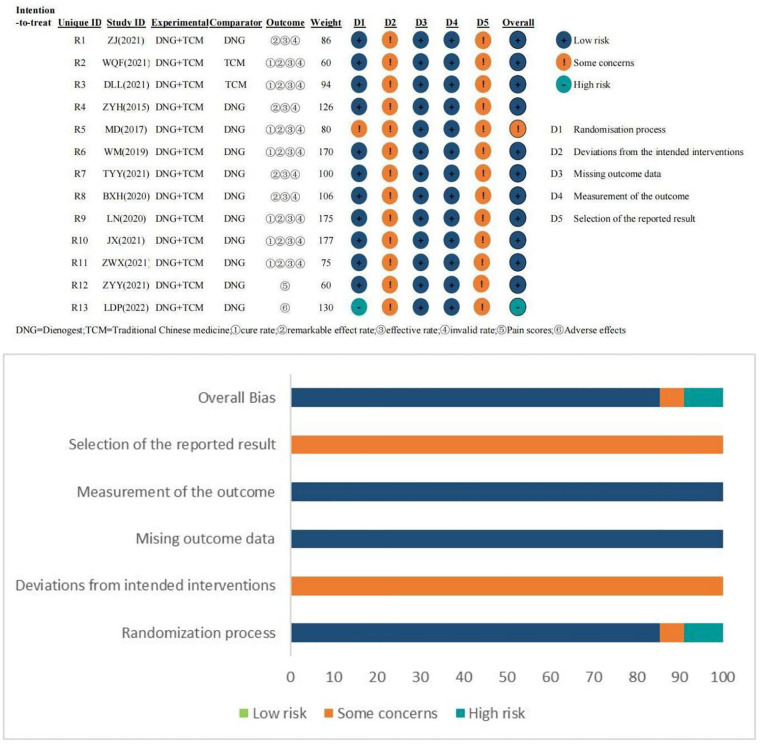

Figure 2 shows the results of the analysis of methodology quality of the included studies. No information regarding bias caused by deviations from the intended intervention on whether a departure occurred from the intended intervention was reported. Although the blinding of all studies to prognostic assessment was unclear, patients with endometriosis had objective indicators on rates of treatment effect or the rate of adverse effects, and it was difficult to influence prognostic assessment. In the final data analysis, all outcome data were included for randomized patients. All studies lacked clarity regarding the outcomes of blinding.

Figure 2.

Quality assessment chart of all literature included in this study.

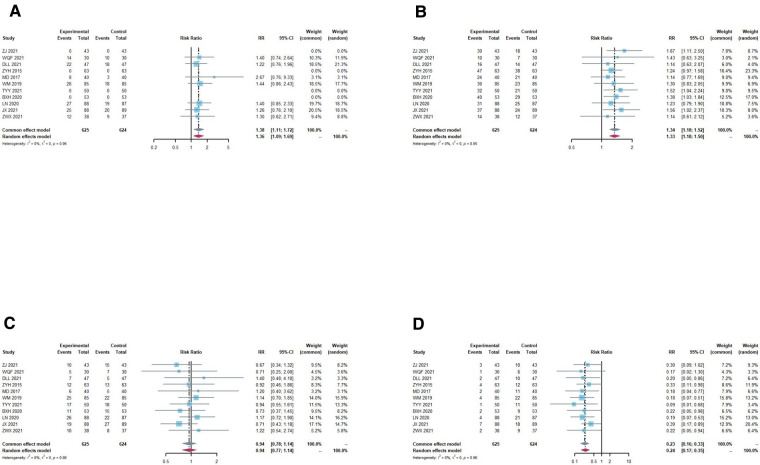

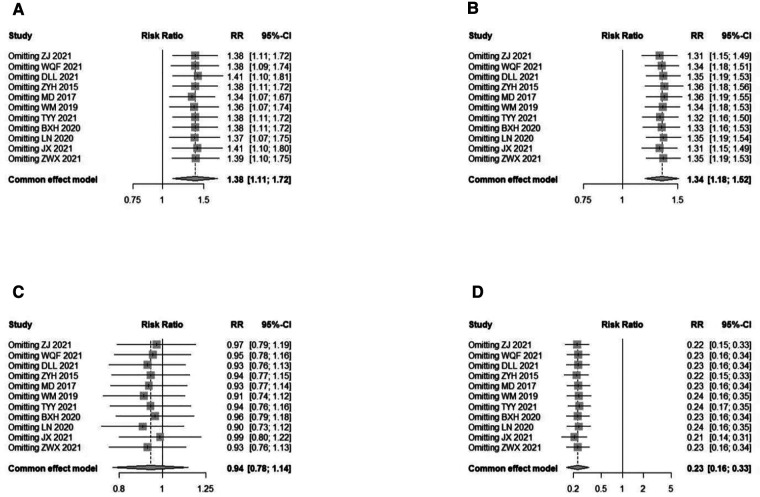

Rate of treatment effect

Treatment results were classified as cure, remarkable effect, effective, and invalid. The criteria for “cure” was a decrease in the Chinese Medicine Syndromes score >90.00% and disappearance of pelvic mass; “remarkable” was a decrease in the Chinese Medicine Syndromes score of 66.67%–90.00%, a significant reduction in clinical symptoms and signs, and a reduction in pelvic mass diameter by 1/2; “effective” was a decrease in the Chinese Medicine Syndromes score of 33.33%∼66.66%, and a reduction in pelvic mass diameter by 1/3 but <1/2; “ineffective” was a decrease in the Chinese Medicine Syndromes score of <33.33%, and a reduction in pelvic mass diameter by <1/3 or aggravation. In terms of cure rate, a fixed effects model was used as no significant heterogeneity was found (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.9611). The result (RR = 1.3780; 95% CI, 1.1058, 1.7172; P = 0.0043) indicated that TCM plus DNG was superior to DNG/TCM alone in increasing the cure rates (Figure 3A). At the same time, the intervention group outperformed the control group in terms of remarkable effect rate (Figure 3B) and invalid rate (Figure 3C), but with no significant difference between the two groups in terms of effective rate (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Overall meta-analysis forest plot of treatment effect rates. (A) cure rate, a fixed effects model was used as no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.9611) was found. The result (RR = 1.3863; 95% CI, 1.1008; 1.7458, P = 0.0043) indicated that TCM plus DNG was superior to DNG/TCM alone in increasing the cure rate. (B) remarkable effect rates, a fixed effects model was used as no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.9530) was found. The result (RR = 1.3389; 95% CI, 1.1829,1.5154; P < 0.0001) indicated that TCM plus DNG was superior to DNG/TCM alone in increasing remarkable effect rate. (C) effective rate, a fixed effects model was used as no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.8638) was found. The result (RR = 0.9411; 95% CI, 0.7752, 1.1425; P = 0.5395) indicated that there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of effective rate. (D) invalid rate, a fixed effects model was used as no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.9629) was found. The result (RR = 0.2299; 95% CI, 0.1591, 0.3322; P < 0.0001) indicated that TCM plus DNG was superior to DNG/TCM alone in decreasing invalid rate.

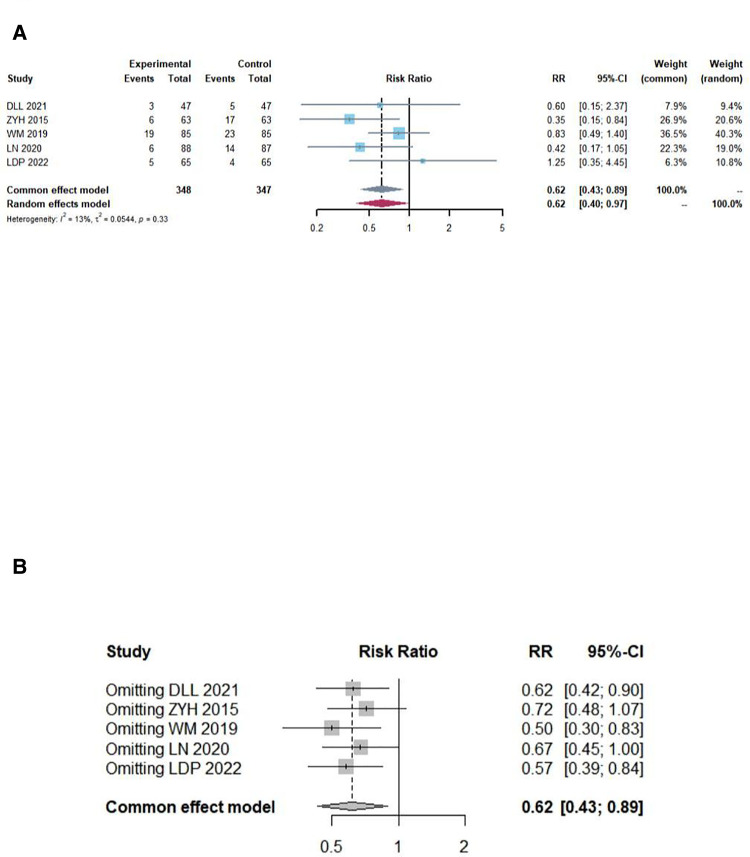

Rate of adverse effects

In total, five studies provided all cases of adverse effects in the experimental and control groups. In the pooled data, there were no statistically significant differences (P = 0.3316, I2 = 12.9%); thus, the fixed model was assumed. The combination of DNG with TCM for endometriosis significantly reduced the rate of adverse effects compared to DNG or TCM alone (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Overall meta-analysis forest and sensitivity analysis plot of adverse effects rates. (A) Overall meta-analysis forest plot, there were no significant statistically significant differences (I2 = 12.4%, P = 0.3316); thus, the fixed model was assumed. The combination of DNG with TCM for endometriosis can significantly reduce the rate of adverse reactions compared to DNG or TCM alone (RR = 0.6177; 95% CI, 0.4288, 0.8899; P = 0.0097). (B) sensitivity analysis plot of the adverse effects rates, according to the leave-one-out method sensitivity analysis, the individual study results had no impact on the meta-analysis results.

Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis

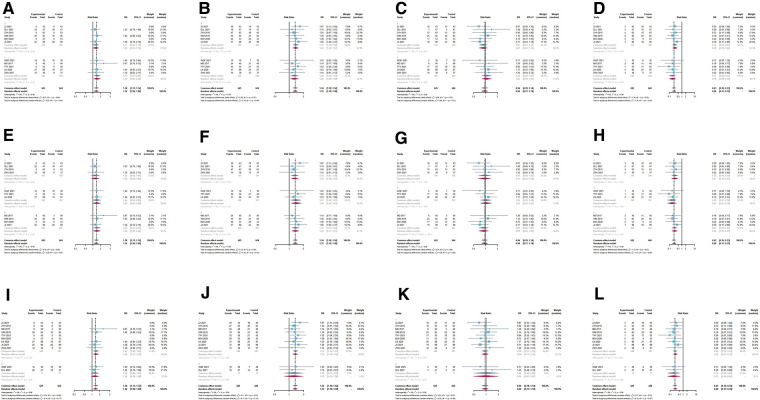

Subgroup analysis was conducted on the cure rate, remarkable effect rate, invalid rate and adverse effects rate according to treatment duration, different TCM combined with DNG, and different control groups respectively. The combination was more effective than either drug alone (P < 0.05) (Figure 5). No difference was found in the subgroup analysis of the combination over different durations of treatment (Figures 5A–D). Similar results were found in the subgroup analysis of different TCM combinations with DNG (Figures 5E–H). Also, subgroup analyses with different controls had not significantly different (Figures 5I–L). According to the leave-one-out method sensitivity analysis, individual study results had no effect on the meta-analysis results of the rates of treatment effect (Figure 6) or the rate of adverse effects (Figure 4B). In most outcome evaluation indicators, individual study results had no effect on the meta-analysis results (Supplementary files).

Figure 5.

Subgroup analysis forest plot based on the treatment course, different TCM + DNG and different controls of treatment effect rates. (A–D) Subgroup analysis forest plot based on the treatment course of treatment effect rates. (E–H) Subgroup analysis forest plot based on different TCM + DNG of treatment effect rates. (I–K) Subgroup analysis forest plot based on different control of treatment effect rates. (A,E,I) cure rate; (B,F,J) remarkable effects rate; (C,G,K) effective rate; (D,H,L) invalid rates. Significant differences were not observed between the subgroups.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis plot of treatment effect rates. According to the leave-one-out method sensitivity analysis, the individual study results had no impact on the meta-analysis results in all four rates. (A) cure rate; (B) remarkable effect rate; (C) effective rate; (D) invalid rate.

Publication bias

The possibility of publication bias was examined using different approaches. Figure 7 shows five funnel plots that appear visually symmetrical. In terms of cure rate, an analysis of publication bias was conducted using the trim and fill method because there were fewer than 10 included studies. The test results showed P = 0.0058, indicating statistical significance; therefore there was publication bias in the cure rate data.

Figure 7.

Funnel plot of treatment effect rates and adverse effects rates. (A) cure rate; (B) remarkable effect rate; (C) effective rate; (D) invalid rate; and (E) adverse effects rate. According to the funnel plot, there is no evidence for publication bias.

Other outcomes

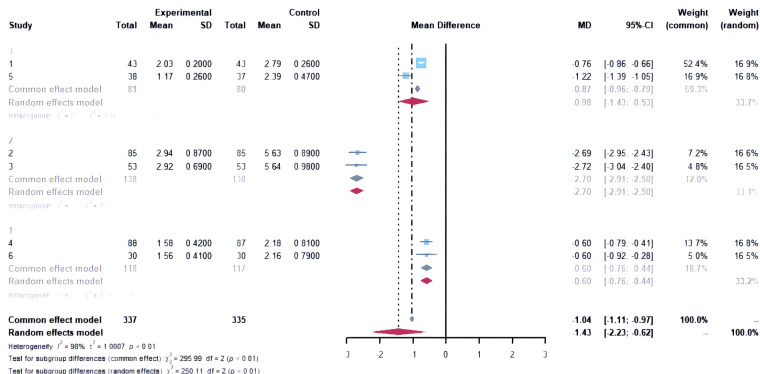

In this study, we also compared other outcome indicators after treatment and showed that the combination was significantly better than the drugs alone, in terms of E2, P, CA-125, CA-199, MMP-2, MMP-9, Gal-3, VEGF, cyst size, and VAS. In terms of the post-treatment VAS, subgroup analysis suggested heterogeneity stemming from Jingtong yushu granules and the Bushen Huayu decoction (Figure 8). However, we found no difference between the two groups after treatment in LH, FSH, ovulation recovery time, and menses recovery time (Table 3). The recurrence rate could not be analyzed as there was too little literature available to create a data set.

Figure 8.

Subgroup analysis forest plot based on post-treatment visual analogue scale/score. Study 1 and 5: Jingtong yushu granule and Bushen Huayu decoction. Study 2 and 3 Gui’e lengwu decoction; study 4 and 6: Gui Zhi Fu Ling capsules/wan.

Table 3.

Comparison of indicators after treatment.

| Index | Author (year) | Experiment | Control | Sample size (EG/CG) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | S | X | S | Model | I 2 | P | |||

| E2 (pmol/L) | WQF (2021) | 103.41 | 11.22 | 125.46 | 14.24 | 30/30 | Random | 77% | <0.0001 |

| DLL (2021) | 103.23 | 11.04 | 125.52 | 14.33 | 47/47 | ||||

| TYY (2021) | 102.12 | 10.12 | 128.12 | 14.21 | 50/50 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 103.54 | 10.98 | 125.48 | 14.27 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZYY (2021) | 103.52 | 10.94 | 125.46 | 14.25 | 30/30 | ||||

| LDP (2022) | 125.44 | 30.42 | 172.44 | 30.83 | 65/65 | ||||

| P (nmol/L) | WQF (2021) | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.61 | 0.18 | 30/30 | Fixed | 0.0% | <0.0001 |

| DLL (2021) | 0.39 | 0.15 | 0.6 | 0.21 | 47/47 | ||||

| TYY (2021) | 0.39 | 0.11 | 0.64 | 0.18 | 50/50 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.61 | 0.19 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZYY (2021) | 0.38 | 0.14 | 0.59 | 0.17 | 30/30 | ||||

| LH (IU/L) | WQF (2021) | 5.76 | 1.71 | 5.42 | 1.63 | 30/30 | Random | 95% | 0.2740 |

| DLL (2021) | 5.75 | 1.68 | 5.37 | 1.57 | 47/47 | ||||

| TYY (2021) | 4.57 | 1.01 | 5.53 | 1.35 | 50/50 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 5.76 | 1.64 | 5.82 | 1.71 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZYY (2021) | 5.74 | 1.62 | 5.81 | 1.69 | 30/30 | ||||

| LDP (2022) | 3.25 | 1.21 | 6.15 | 1.44 | 65/65 | ||||

| FSH (IU/L) | WQF (2021) | 5.52 | 1.73 | 5.69 | 1.62 | 30/30 | Random | 90% | 0.0778 |

| DLL (2021) | 5.51 | 1.68 | 5.72 | 1.59 | 47/47 | ||||

| TYY (2021) | 4.45 | 1.02 | 5.55 | 1.13 | 50/50 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 5.52 | 1.75 | 5.56 | 1.85 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZYY (2021) | 5.51 | 1.73 | 5.54 | 1.83 | 30/30 | ||||

| LDP (2022) | 5.11 | 1.25 | 7.44 | 1.83 | 65/65 | ||||

| CA125 (IU/ml) | WQF (2021) | 42.22 | 11.43 | 62.43 | 11.69 | 30/30 | Random | 91% | <0.0001 |

| DLL (2021) | 42.16 | 11.58 | 62.56 | 11.78 | 47/47 | ||||

| MD (2017) | 51.31 | 23.46 | 62.23 | 19.58 | 40/40 | ||||

| WM (2019) | 42.02 | 11.65 | 63.25 | 12.08 | 85/85 | ||||

| BXH (2020) | 42.01 | 9.32 | 63.36 | 11.43 | 53/53 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 25.42 | 3.98 | 35.67 | 5.22 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZWX (2021) | 41.06 | 10.32 | 53.97 | 11.08 | 38/37 | ||||

| LDP (2022) | 18.33 | 10.62 | 25.74 | 10.36 | 65/65 | ||||

| CA199 (IU/ml) | WQF (2021) | 26.22 | 4.63 | 35.54 | 5.67 | 30/30 | Fixed | 31% | <0.0001 |

| LN (2020) | 26.13 | 4.62 | 35.83 | 5.69 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZWX (2021) | 40.36 | 9.88 | 54.13 | 10.75 | 38/37 | ||||

| MPP2 (µg/L) | WQF (2021) | 129.65 | 12.76 | 171.58 | 19.87 | 30/30 | Fixed | 0.0% | <0.0001 |

| DLL (2021) | 129.81 | 13.05 | 171.69 | 20.06 | 47/47 | ||||

| TYY (2021) | 128.44 | 13.02 | 171.12 | 18.99 | 50/50 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 129.98 | 12.97 | 172.24 | 19.74 | 88/87 | ||||

| Gal-3 (ng/L) | WQF (2021) | 5.68 | 2.31 | 6.89 | 2.24 | 30/30 | Fixed | 0.0% | <0.0001 |

| DLL (2021) | 5.7 | 2.25 | 6.94 | 2.16 | 47/47 | ||||

| TYY (2021) | 5.32 | 2.02 | 6.86 | 2.04 | 50/50 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 5.69 | 2.31 | 6.93 | 3.14 | 88/87 | ||||

| VEGF (pg/ml) | WQF (2021) | 85.65 | 50.67 | 121.58 | 82.84 | 30/30 | Fixed | 0.0% | <0.0001 |

| DLL (2021) | 85.77 | 50.73 | 122.36 | 83.42 | 47/47 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 85.78 | 53.46 | 121.85 | 89.37 | 88/87 | ||||

| MPP9 (ng/L) | DLL (2021) | 565.47 | 220.75 | 690.26 | 293.42 | 47/47 | Fixed | 0.0% | <0.0001 |

| TYY (2021) | 566.54 | 236.23 | 680.12 | 282.12 | 50/50 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 568.38 | 237.53 | 687.34 | 298.47 | 88/87 | ||||

| Diameter (cm) | MD (2017) | 2.46 | 1.04 | 2.97 | 1.22 | 40/40 | Random | 98% | 0.0003 |

| WM (2019) | 1.02 | 0.56 | 2.87 | 0.61 | 85/85 | ||||

| BXH (2020) | 1.01 | 0.47 | 2.73 | 0.62 | 53/53 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 0.69 | 0.25 | 1.25 | 0.31 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZWX (2021) | 0.72 | 0.19 | 1.24 | 0.28 | 38/37 | ||||

| ZYY (2021) | 0.67 | 0.23 | 1.23 | 0.29 | 30/30 | ||||

| VAS | ZJ (2021) | 2.03 | 0.2 | 2.79 | 0.26 | 43/43 | Random | 98% | <0.0005 |

| WM (2019) | 2.94 | 0.87 | 5.63 | 0.89 | 85/85 | ||||

| BXH (2020) | 2.92 | 0.69 | 5.64 | 0.98 | 53/53 | ||||

| LN (2020) | 1.58 | 0.42 | 2.18 | 0.81 | 88/87 | ||||

| ZWX (2021) | 1.17 | 0.26 | 2.39 | 0.47 | 38/37 | ||||

| ZYY (2021) | 1.56 | 0.41 | 2.16 | 0.79 | 30/30 | ||||

| ORT (days) | ZYH (2015) | 13.27 | 2.49 | 18.58 | 2.91 | 63/63 | Random | 97% | 0.0976 |

| JX (2021) | 13.38 | 3.60 | 14.69 | 3.15 | 88/89 | ||||

| MRT (days) | ZYH (2015) | 26.37 | 4.12 | 33.61 | 3.29 | 63/63 | Random | 97% | 0.0585 |

| JX (2021) | 26.48 | 4.23 | 28.72 | 3.40 | 88/89 | ||||

| ADR (%) | DLL (2021) | 3 | 5 | 47/47 | Fixed | 13% | 0.0097 | ||

| ZYH (2015) | 6 | 17 | 63/63 | ||||||

| WM (2019) | 19 | 23 | 85/85 | ||||||

| LN (2020) | 6 | 14 | 88/87 | ||||||

| LDP (2022) | 5 | 4 | 65/65 | ||||||

VAS, visual analogue scale; ORT, oviating recovery time; MRT, menses recovery time; ADR, adverse reaction.

Grade evaluation of evidence quality

According to GRADE guidelines (45), the quality of the evidence for two outcomes of the rates of treatment effect and the rate of adverse effects, was assessed. The outcome indicators could be classified into four levels: high quality, medium quality, low quality, and very low quality. Evidence quality was measured using the following criteria: risk of bias, consistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. The summary of findings and the quality of evidence for study outcomes are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

GRADE rating of the quality of outcome.

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk with DNG or TCM alone | Risk with DNG in combination with TCM | ||||

| Cure rate | 234 per 1,000 | 323 per 1,000 (259 to 402) | RR 1.38 (1.11 to 1.72) | 831 (7 RCTs) | ⊕◯◯◯ Very lowa,b,c |

| Remarkable effect rate | 372 per 1,000 | 498 per 1,000 (439 to 565) | RR 1.34 (1.18 to 1.52) | 1,249 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ Moderatea |

| Effective rate | 252 per 1,000 | 237 per 1,000 (196 to 287) | RR 0.94 (0.78 to 1.14) | 1,249 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ Moderatea |

| Invalid rate | 223 per 1,000 | 51 per 1,000 (36 to 74) | RR 0.23 (0.16 to 0.33) | 1,249 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ Moderatea |

| Rate of Adverse effects | 182 per 1,000 | 113 per 1,000 (78 to 162) | RR 0.62 (0.43 to 0.89) | 695 (5 RCTs) | ⊕◯◯◯ Very lowa,b,d |

CI, confidence interval; RR, risk ratio.

The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

None of the included studies reported blind intervention for patients.

Total number of events is less than 300.

There is publication bias.

Number of studies too small to assess the publication bias.

Discussion

In this study, the major focus of our meta-analysis was on the effectiveness and safety of TCM in combination with DNG in the treatment of endometriosis. The results showed that the combination was significantly better than the drugs alone, in cure rate, remarkable effect rate, invalid rate and adverse effects. The same conclusions were drawn from the results of the subgroup analyses depending on the course of treatment, the different TCM combined with DNG, and the different control groups. In addition, the combination showed significant advantages in other outcome indicators after treatment: E2, P, CA-125, CA-199, MMP-2, MMP-9, Gal-3, VEGF, cyst size, and VAS were significantly lower in patients on the combination than in those on the drugs alone.

Herbal medicine has been used for centuries as a treatment for endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea, pelvic inflammation, and cysts (46). Due to the complex pathogenesis of endometriosis and the limited therapeutic effects, TCM has been used to treat patients' primary lesions and control their symptoms (47). TCM aims for a healthy circulation and the removal of blood stasis. This could be an important strategy for preventing endometriosis angiogenesis (48). At the same time, herbal remedies for endometriosis are designed to relieve blood stagnation and nourish the kidney (49). A number of TCM formulas have been used to treat endometriosis-associated pelvic inflammation, and they have resulted in satisfying results (50). For example, Hua Yu Xiao Zheng decoction (49), Wenjing decoction (51), Guizhi Fuling Capsule (also called Guizhi Fuling Wan) (52), Saffron (53), and Chinese medicine using Curcuma phaeocaulis Valeton (48). Among them, Guizhi Fuling Capsule was the most frequently used of all TCM for the treatment of endometriosis (54), which is also consistent with our inclusion study (4/13), its mechanisms of action mainly included improvement of hemodynamics, acesodyne and anti-inflammation (55). Some studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of Guizhi Fuling Capsule alone in the treatment of endometriosis (56). Overall and subgroup analyses of our study suggests that combination therapy is more effective in cure, remarkable effect, invalid and adverse effects rate. Thus suggests that combination TCM with DNG is an option for the treatment of endometriosis. However, contrary to the findings of our study, some study suggested that the combination of Guizhi Fuling Capsule with western medicines may have a negative impact on the treatment of endometriosis (56). Therefore, more research is needed to prove exactly how effective TCM in combination with existing western medicine is in treating endometriosis.

Oestrogen plays a key role in endometriosis (57). Endometriosis is characterized by an excess of estrogen, which can contribute to endometriotic lesions expanding faster (58). E2, which is the most active form of estrogen, works mainly through estrogen receptors (59). It can promote growth of endometriosis lesions in a hormone-dependent manner, both through systemic and local production (60). In our study, combination therapy significantly reduced E2 levels in patients compared to drugs alone. Studies have shown that the expression of VEGF, MMP2 and MMP9 in ectopic endometrium is significantly higher than that in eutopic endometrium, which also suggests that over-expression of angiogenic factors and metalloproteinases may be characteristic of those endometrium with the potential to transform into endometrial lesions (61). It has also been shown that VEGF, MMP-2 and MMP-9 are significantly elevated in the serum of patients with endometriosis (62). In contrast, CA-125 and CA-199 are significantly increased in the serum of patients with endometriosis and together with some other serological indicators can be used as a reference for the early diagnosis and staging of endometriosis (63, 64). Some study found that Gal-3 was over-expressed in all forms of endometriosis (65), it played an important role in the development of endometriosis and might be a target for endometriosis treatment (66). In our study, these indicators were significantly lower in the combination group than in the single drug group after treatment, which also suggests that the former is significantly better than the latter. In addition, LH, FSH, ovulation recovery time, and menses recovery time were not significantly different between the two groups after treatment, suggesting that the combination treatment did not impair ovarian function. This further supports that combination therapy maybe a good option.

Although peritoneal superficial lesions and ovarian endometriomas represent the majority of endometriotic implants within the pelvis, deep infiltrating endometriosis and extrapelvic endometriosis are the most challenging conditions to treat. Sometimes medical therapy is sufficient to reduce symptoms and signs (67, 68), however, in a large number of patients a complete eradication, with a nerve-sparing and vascular sparing approach (69, 70) is needed to restore normal pelvic anatomy and function. Many studies have suggested that DNG is effective in the treatment of deeply infiltrated endometriosis. It can prevent recurrence of post-operative DIE, control post-operative related pelvic pain (14, 15), reduce endometriotic lesions (71), reduce difficulties with intercourse and enhance sexual function (13), treat symptoms caused by rectosigmoid endometriosis (72), and improve quality of life (73). However, there are no studies regarding the use of TCM treatment for DIE. All the trials included in this study also did not classify endometriosis in detail, so it is not possible to know how effective herbal medicine combined with DNG is in treating DIE. Therefore, future clinical studies of DNG combined with TCM for DIE should be conducted.

This study had several limitations. First of all, the sample size was small, and the populations selected in this study were all Chinese. Therefore, our findings need to be validated in larger samples, other countries, and other ethnic groups. Second, not all RCTs reported their methods, which made assessing their methodological quality and judging their bias probability difficult; and there was publication bias in the cure rate data in our analysis, the quality of the evidence ranges from moderate to low. The reliability of the analysis results is therefore not high. Third, the lack of uniformity in herbal prescriptions may lead to potential bias. Fourth, all the literature included in the study was in Chinese owing to the geographical limitations of the use of Chinese medicine. Fifth, as the literature data does not provide more detailed data, it could not do further analysis according with endometriosis stage (refer to ASRM, ENZIAN) and localization (Superficial endometriosis, endometrioma, DIE).

In summary, the results of this meta-analysis suggest that TCM combined with DNG is superior to DNG or TCM alone and can be used as a complementary treatment after endometriosis treatment. TCM has potential for improving the clinical efficacy and reducing the side effects of DNG. A large, well-designed prospective study with a long-term approach is needed because of the limited number of included studies and the lack of precise methodology.

Protocol assessment

Protocols can be accessed on PROSPERO (york.ac.uk).

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Annual Science and Technology Steering Plan Project of Zhuzhou (2019-57).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

HC and CL wrote the manuscript. YW and YL participated in the search strategy development. HJ assisted in acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. HC and YW prepared figures and tables, and contributed to study concept and design. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Hogg C, Horne AW, Greaves E. Endometriosis-associated macrophages: origin, phenotype, and function. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2020) 11:7. 10.3389/fendo.2020.00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor HS, Kotlyar AM, Flores VA. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet. (2021) 397(10276):839–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00389-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu H, Li B, Li T, Zhang S, Lin X. Combination of noninvasive methods in diagnosis of infertile women with minimal or mild endometriosis, a retrospective study in China. Medicine (Baltimore). (2019) 98(31):e16695. 10.1097/MD.0000000000016695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mo X, Zeng Y. The relationship between ovarian endometriosis and clinical pregnancy and abortion rate based on logistic regression model. Saudi J Biol Sci. (2020) 27(1):561–6. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallas-Potts A, Dawson JC, Herrington CS. Ovarian cancer cell lines derived from non-serous carcinomas migrate and invade more aggressively than those derived from high-grade serous carcinomas. Sci Rep. (2019) 9(1):5515. 10.1038/s41598-019-41941-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapron C, Marcellin L, Borghese B, Santulli P. Rethinking mechanisms, diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2019) 15(11):666–82. 10.1038/s41574-019-0245-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samartzis EP, Fink D, Stucki M, Imesch P. Doxycycline reduces MMP-2 activity and inhibits invasion of 12Z epithelial endometriotic cells as well as MMP-2 and -9 activity in primary endometriotic stromal cells in vitro. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. (2019) 17(1):38. 10.1186/s12958-019-0481-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moravek MB, Ward EA, Lebovic DI. Thiazolidinediones as therapy for endometriosis: a case series. Gynecol Obstet Invest. (2009) 68(3):167–70. 10.1159/000230713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor HS, Alderman Iii M, D’Hooghe TM, Fazleabas AT, Duleba AJ. Effect of simvastatin on baboon endometriosis. Biol Reprod. (2017) 97(1):32–8. 10.1093/biolre/iox058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho YH, Um MJ, Kim SJ, Kim SA, Jung H. Raloxifene administration in women treated with long term gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist for severe endometriosis: effects on bone mineral density. J Menopausal Med. (2016) 22(3):174–9. 10.6118/jmm.2016.22.3.174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsubara S, Kawaguchi R, Akinishi M, Nagayasu M, Iwai K, Niiro E, et al. Subtype I (intrinsic) adenomyosis is an independent risk factor for dienogest-related serious unpredictable bleeding in patients with symptomatic adenomyosis. Sci Rep. (2019) 9(1):17654. 10.1038/s41598-019-54096-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zakhari A, Edwards D, Ryu M, Matelski JJ, Bougie O, Murji A. Dienogest and the risk of endometriosis recurrence following surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. (2020) 27(7):1503–10. 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barra F, Scala C, Leone Roberti Maggiore U, Ferrero S. Long-term administration of dienogest for the treatment of pain and intestinal symptoms in patients with rectosigmoid endometriosis. J Clin Med. (2020) 9(1):154. 10.3390/jcm9010154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piacenti I, Viscardi MF, Masciullo L, Sangiuliano C, Scaramuzzino S, Piccioni MG, et al. Dienogest versus continuous oral levonorgestrel/EE in patients with endometriosis: what’s the best choice? Gynecol Endocrinol. (2021) 37(5):471–5. 10.1080/09513590.2021.1892632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leonardo-Pinto JP, Benetti-Pinto CL, Cursino K, Yela DA. Dienogest and deep infiltrating endometriosis: the remission of symptoms is not related to endometriosis nodule remission. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2017) 211:108–11. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Römer T. Long-term treatment of endometriosis with dienogest: retrospective analysis of efficacy and safety in clinical practice. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2018) 298(4):747–53. Erratum in: Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2019) 299(1):293. 10.1007/s00404-018-4864-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andres Mde P, Lopes LA, Baracat EC, Podgaec S. Dienogest in the treatment of endometriosis: systematic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2015) 292(3):523–9. 10.1007/s00404-015-3681-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Gong H, Gou J, Liu X, Li Z. Dienogest as a maintenance treatment for endometriosis following surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). (2021) 8:652505. 10.3389/fmed.2021.652505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho B, Roh JW, Park J, Jeong K, Kim TH, Kim YS, et al. Safety and effectiveness of dienogest (visanne®) for treatment of endometriosis: a large prospective cohort study. Reprod Sci. (2020) 27(3):905–15. 10.1007/s43032-019-00094-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ren X-l, Zhao X. Analysis on English translation of “zhongyi” “zhongyao” and “zhongyiyao”-for the translation of the new connotation of basic core terms of Chinese medicine. J Basic Chin Med. (2017) 23(09):1311–4 + 1325. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie C, Wang Z, Wang C, Xu J, Wen Z, Wang H, et al. Utilization of gene expression signature for quality control of traditional Chinese medicine formula Si-Wu-Tang. AAPS J. (2013) 15(3):884–92. 10.1208/s12248-013-9491-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun L, Ding F, You G, Liu H, Wang M, Ren X, et al. Development and validation of an UPLC-MS/MS method for pharmacokinetic comparison of five alkaloids from JinQi jiangtang tablets and its monarch drug coptidis rhizoma. Pharmaceutics. (2017) 10(1):4. 10.3390/pharmaceutics10010004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiang Y, Guo Z, Zhu P, Chen J, Huang Y. Traditional Chinese medicine as a cancer treatment: modern perspectives of ancient but advanced science. Cancer Med. (2019) 8(5):1958–75. 10.1002/cam4.2108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jia MQ, Xiong YJ, Xue Y, Wang Y, Yan C. Using UPLC-MS/MS for characterization of active components in extracts of yupingfeng and application to a comparative pharmacokinetic study in rat plasma after oral administration. Molecules. (2017) 22(5):810. 10.3390/molecules22050810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao JN, Zhang Y, Lan X, Chen Y, Li J, Zhang P, et al. Efficacy and safety of Xinnaoning capsule in treating chronic stable angina (qi stagnation and blood stasis syndrome): study protocol for a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). (2019) 98(31):e16539. 10.1097/MD.0000000000016539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun S, Mo X, Li Y, Gong Z, Wang J, Yu X, et al. Effectiveness comparisons of Chinese patent medicine on treating premature ejaculation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). (2019) 98(44):e17729. 10.1097/MD.0000000000017729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin SS, Liu CX, Zhang JH, Wang XL, Mao JY. Efficacy and safety of oral Chinese patent medicine combined with conventional therapy for heart failure: an overview of systematic reviews. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2020) 2020:8620186. 10.1155/2020/8620186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He H, Wang X, Xiao Y, Zheng J, Wang J, Zhang B. Comparative efficacy and safety of traditional Chinese patent medicine in the treatment of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). (2020) 99(51):e23747. 10.1097/MD.0000000000023747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu SZ, Xu HY. Progress in the prevention and treatment of endometriosis recurrence by traditional Chinese and western medicine. J Guangzhou Univ TCM. (2017) 34(5):790–2. 10.13359/j.cnki.gzxbtcm.2017.05.036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ni ZX, Cheng W, Sun S, Yu CQ. Feasibility analysis of traditional Chinese medicine as the first line of conservative treatment for endometriosis. Mater Child Health Care China. (2020) 35(01):178–81. 10.19829/j.zgfybj.issn.1001-4411.2020.01.059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balduzzi S, Rücker G, Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid Based Ment Health. (2019) 22(4):153–60. 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang J. Comparison of curative effect between denogest alone and combined with Jingtongyushu granule in the treatment of endometriosis. J Med TTheory Pract. (2021) 34(3):470–2. 10.19381/j.issn.1001-7585.2021.03.052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang QF, Zhen J, Wang JP. Clinical efficacy of denogest in patients with endometriosis. Pract Clin J Integr Tradit Chin Western Med. (2021) 21(6):33–4. 10.13638/j.issn.1671-4040.2021.06.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duan LL, Li ZB, Zhang C, Yang H, Wang L, Wu XF, et al. The therapeutic effect of dienogest on endometriosis. Chin J Woman Child Health Resea. (2021) 32(6):909–13. 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5293.2021.06.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang YH, Liu XJ, Sun XB, Chen JP, Jiao GQ. Clinical observation laparoscopy combined with dienogest and TCM in the treament of endometriosis. China Pharm. (2015) 26(35):4960–1. 10.6039/j.issn.1001-0408.2015.35.21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mu D. Efficacy of the Guielengwu decoction combined with dienogest in treating endometriosis and its effect on serum CA125 level. J Sichuan Tradit Chin Med. (2017) 35(9):130–1. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang M, Chen L. Efficacy of the Guielengwu decoction combined with dienogest in treating endometriosis and its effect on serum CA125 level. Mordern Jf Integr Tradit Chin Western Med. (2019) 28(20):2244–6. 10.3969/j.issn.1008-8849.2019.20.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tong YY, Zhong HZ. Clinical study on Guizhi Fuling Capsules combined with denogest in treatment of endometriosis. Modern Practl Med. (2021) 33(9):1196–8. 10.3969/j.issn.1671-0800.2021.09.033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bi XH, Li SQ. Therapeutic effect of combined traditional Chinese and Western Medicine on endometriosiss. Shenzhen J Integr Tradit Chin Western Med. (2020) 30(14):35–6. 10.16458/j.cnki.1007-0893.2020.14.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu N, Zhang D, Yuan WN. Clinical study on Guizhi Fuling Capsules combined with denogest in treatment of endometriosis. Drugs Clin. (2020) 35(6):1117–21. 10.7501/j.issn.1674-5515.2020.06.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ji X, Wang F, Jiang XY, Xing JH. The efficacy of dienogest combined with traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of endometriosis and its influence on pregnancy and recurrence. Chin J Postgrad Med. (2021) 44(10):930–4. 10.3760/cma.j.cn115455-20201109-01544 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang WX, Zhao YQ. Clinical efficacy of Bushen Huayu Decoction Combined with dienogest in the treatment of endometriosis. China Health Food. (2021) 7:40–1. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang YY. Clinical study of high-dose dinogestrin combined with Guizhi Fuling pill in the treatment of endometriosis. Diet Health. (2021) 17:19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li DP. Clinical efficacy of Kuntai Capsule Combined with dienogest in the treatment of endometriosis. Health Care Guide. (2022) 10:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE Guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. (2011) 64(4):383–94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim BS, Chung TW, Choi HJ, Bae SJ, Cho HR, Lee SO, et al. Caesalpinia sappan induces apoptotic cell death in ectopic endometrial 12Z cells through suppressing pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 expression. Exp Ther Med. (2021) 21(4):357. 10.3892/etm.2021.9788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flower A, Liu JP, Lewith G, Little P, Li Q. Chinese Herbal medicine for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2012) (5):CD006568. 10.1002/14651858.CD006568.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng W, Wu J, Gu J, Weng H, Wang J, Wang T, et al. Modular characteristics and mechanism of action of herbs for endometriosis treatment in Chinese medicine: a data mining and network pharmacology-based identification. Front Pharmacol. (2020) 11:147. 10.3389/fphar.2020.00147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen ZZ, Gong X. Effect of Hua Yu Xiao Zheng decoction on the expression levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietin-2 in rats with endometriosis. Exp Ther Med. (2017) 14(6):5743–50. 10.3892/etm.2017.5280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou WJ, Yang HL, Shao J, Mei J, Chang KK, Zhu R, et al. Anti-inflammatory cytokines in endometriosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2019) 76(11):2111–32. 10.1007/s00018-019-03056-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu YN, Hu XJ, Liu B, Shang YJ, Xu WT, Zhou HF. Network pharmacology-based prediction of bioactive compounds and potential targets of wenjing decoction for treatment of endometriosis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2021) 2021:4521843. 10.1155/2021/4521843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tao F, Ruan S, Liu W, Wang L, Xiong Y, Shen M. Fuling granule, a traditional Chinese medicine compound, suppresses cell proliferation and TGFβ-induced EMT in ovarian cancer. PLoS One. (2016) 11(12):e0168892. 10.1371/journal.pone.0168892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bian Y, Yuan L, Yang X, Weng L, Zhang Y, Bai H, et al. SMURF1-mediated Ubiquitylation of SHP-1 promotes cell proliferation and invasion of endometrial stromal cells in endometriosis. Ann Transl Med. (2021) 9(5):362. 10.21037/atm-20-2897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsai PJ, Lin YH, Chen JL, Yang SH, Chen YC, Chen HY. Identifying Chinese herbal medicine network for endometriosis: implications from a population-based database in Taiwan. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2017) 2017:7501015. 10.1155/2017/7501015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang X, Shi Y, Xu L, Wang Z, Wang Y, Shi W, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine prescription Guizhi Fuling Pills in the treatment of endometriosis. Int J Med Sci. (2021) 18(11):2401–8. 10.7150/ijms.55789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen CC, Huang CY, Shiu LY, Yu YC, Lai JC, Chang CC, et al. Combinatory effects of current regimens and Guizhi Fuling Wan on the development of endometriosis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. (2022) 61(1):70–4. 10.1016/j.tjog.2021.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sapkota Y, Steinthorsdottir V, Morris AP, Fassbender A, Rahmioglu N, De Vivo I, et al. Meta-analysis identifies five novel loci associated with endometriosis highlighting key genes involved in hormone metabolism. Nat Commun. (2017) 8:15539. 10.1038/ncomms15539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prather GR, MacLean JA, 2nd, Shi M, Boadu DK, Paquet M, Hayashi K. Niclosamide as a potential nonsteroidal therapy for endometriosis that preserves reproductive function in an experimental mouse model. Biol Reprod. (2016) 95(4):76. 10.1095/biolreprod.116.140236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bian C, Bai B, Gao Q, Li S, Zhao Y. 17β-estradiol regulates glucose metabolism and insulin secretion in rat islet β cells through GPER and Akt/mTOR/GLUT2 pathway. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2019) 10:531. 10.3389/fendo.2019.00531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huhtinen K, Desai R, Ståhle M, Salminen A, Handelsman DJ, Perheentupa A, et al. Endometrial and endometriotic concentrations of estrone and estradiol are determined by local metabolism rather than circulating levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2012) 97(11):4228–35. 10.1210/jc.2012-1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Di Carlo C, Bonifacio M, Tommaselli GA, Bifulco G, Guerra G, Nappi C. Metalloproteinases, vascular endothelial growth factor, and angiopoietin 1 and 2 in eutopic and ectopic endometrium. Fertil Steril. (2009) 91(6):2315–23. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.03.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lin K, Ma J, Peng Y, Sun M, Xu K, Wu R, et al. Autocrine production of interleukin-34 promotes the development of endometriosis through CSF1R/JAK3/STAT6 signaling. Sci Rep. (2019) 9(1):16781. 10.1038/s41598-019-52741-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen T, Wei JL, Leng T, Gao F, Hou SY. The diagnostic value of the combination of hemoglobin, CA199, CA125, and HE4 in endometriosis. J Clin Lab Anal. (2021) 35(9):e23947. 10.1002/jcla.23947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tang T, Lai H, Huang X, Gu L, Shi H. Application of serum markers in diagnosis and staging of ovarian endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. (2021) 47(4):1441–50. 10.1111/jog.14654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Noël JC, Chapron C, Borghese B, Fayt I, Anaf V. Galectin-3 is overexpressed in various forms of endometriosis. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. (2011) 19(3):253–7. 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181f5a05e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mattos RM, Machado DE, Perini JA, Alessandra-Perini J, Meireles da Costa NO, Wiecikowski AFDRO, et al. Galectin-3 plays an important role in endometriosis development and is a target to endometriosis treatment. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2019) 486:1–10. 10.1016/j.mce.2019.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Laganà AS, Vitale SG, Granese R, Palmara V, Ban Frangež H, Vrtačnik-Bokal E, et al. Clinical dynamics of Dienogest for the treatment of endometriosis: from bench to bedside. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. (2017) 13(6):593–6. 10.1080/17425255.2017.1297421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sansone A, De Rosa N, Giampaolino P, Guida M, Laganà AS, Di Carlo C. Effects of etonogestrel implant on quality of life, sexual function, and pelvic pain in women suffering from endometriosis: results from a multicenter, prospective, observational study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2018) 298(4):731–6. 10.1007/s00404-018-4851-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Laganà AS, Vitale SG, Trovato MA, Palmara VI, Rapisarda AM, Granese R, et al. Full-thickness excision versus shaving by laparoscopy for intestinal deep infiltrating endometriosis: rationale and potential treatment options. Biomed Res Int. (2016) 2016:3617179. 10.1155/2016/3617179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Raffaelli R, Garzon S, Baggio S, Genna M, Pomini P, Laganà AS, et al. Mesenteric vascular and nerve sparing surgery in laparoscopic segmental intestinal resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2018) 231:214–9. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.10.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ceccaroni M, Clarizia R, Liverani S, Donati A, Ceccarello M, Manzone M, et al. Dienogest vs GnRH agonists as postoperative therapy after laparoscopic eradication of deep infiltrating endometriosis with bowel and parametrial surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Endocrinol. (2021) 37(10):930–3. 10.1080/09513590.2021.1929151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paulo Leonardo-Pinto J, Laguna Benetti-Pinto C, Angerame Yela D. When solving dyspareunia is not enough to restore sexual function in women with deep infiltrating endometriosis treated with dienogest. J Sex Marital Ther. (2019) 45(1):44–9. 10.1080/0092623X.2018.1474411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alcalde AM, Martínez-Zamora MÁ, Gracia M, Ros C, Rius M, Castelo-Branco C, et al. Assessment of quality of life, sexual quality of life, and pain symptoms in deep infiltrating endometriosis patients with or without associated adenomyosis and the influence of a flexible extended combined oral contraceptive regimen: results of a prospective, observational study. J Sex Med. (2022) 19(2):311–8. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.