Abstract

Borrelia burgdorferi can persistently infect mammals despite their production of antibodies directed against bacterial proteins, including the Erp lipoproteins. We sequenced erp loci of bacteria reisolated from laboratory mice after 1 year of infection and found them to be identical to those of the inoculant bacteria. We conclude that recombination of erp genes is not essential for chronic mammalian infection.

The spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, is spread through the bites of infected Ixodes ticks (12, 46). After being transferred from the tick vector, bacteria disseminate throughout the mammalian host and can be reisolated from many tissues and, occasionally, the bloodstream (8, 11, 16, 26). B. burgdorferi infection may cause a variety of symptoms in humans, including skin lesions, arthritis, and damage to the neurologic and cardiac systems (34). Infected mammals produce antibodies that are bacteriocidal in vitro (25, 30), and passive transfer of sera from infected humans and laboratory animals can protect naïve animals against B. burgdorferi challenge (8, 20, 44). Furthermore, infected animals that have been cured by antibiotic treatment are resistant to reinfection (7, 38). However, antibodies directed against B. burgdorferi often cannot effectively clear infection, and the bacteria may persistently infect humans and other mammals, causing periodic recurrences of symptoms (8, 13, 34, 40). Spirochetes have often been reisolated from immunocompetent animals 1 year or more after infection (4, 9, 33, 45). The means by which B. burgdorferi is able to successfully evade clearance by the host immune system and cause recurrent disease symptoms are unknown.

A possible method is suggested by studies of the Borrelia species that cause relapsing fever, such as B. hermsii, which persist in mammalian hosts by undergoing genetic recombination. Although infected animals produce antibodies directed against surface-exposed Vmp proteins, B. hermsii avoids clearance by continually rearranging the DNA sequence at the vmp expression locus, thus producing novel Vmp proteins that are unrecognized by the host immune system (5, 55). Several antigen-encoding B. burgdorferi loci have been identified that exhibit evidence of intergenic recombination (17, 21, 24, 29, 41, 42, 48, 51, 58, 59, 61), and it has been suggested that such rearrangements could occur within mammalian hosts to permit chronic infection. This appears to be the case with the antigen-encoding vlsE locus, where it has been observed that B. burgdorferi reisolated from infected animals frequently contains vlsE genes with sequences different from the original inoculant bacteria (61–63).

Within the first 4 weeks of infection, humans and other mammals produce antibodies directed against members of the B. burgdorferi Erp protein family (1, 3, 18, 27, 36, 50, 53, 56, 60), indicating that these proteins are produced by the bacteria during mammalian infections. Characterization of Erp proteins indicated that these proteins are all likely to be membrane-bound lipoproteins (3, 27, 60), and initial studies suggested that they are surface exposed in the bacteria (27). Linkage analyses indicated that there have been genetic rearrangements among B. burgdorferi erp loci (51), although it is not yet known at which point(s) of the infectious cycle these DNA rearrangements take place. A single bacterium may contain as many as 15 erp genes, arranged in mono- or bicistronic loci on up to at least nine different plasmids (2, 14, 15, 50–52, 54). All Lyme disease spirochetes studied in detail contain multiple plasmid-borne erp genes (2, 3, 14, 15, 54), which have also been given various other names such as ospE, ospF, p21, pG, elpA, elpB, bbk2.10, and bbk2.11 (2, 3, 27, 56, 60). This multiplicity has led to suggestions that the genes may rearrange during mammalian infection in a manner similar to the B. hermsii vmp and B. burgdorferi vls loci (31, 51). The majority of erp-containing plasmids are 30- to 32-kb circular plasmids that are homologous throughout most of their lengths (2, 14, 15, 39, 51, 52, 54, 64), and several features of these plasmids suggest that they are bacteriophage genomes (14, 15). Bacteriophage particles have occasionally been observed in cultures of B. burgdorferi (22, 35) and may play roles in gene transfer and rearrangement, as is the case with some other spirochetes (23). To study the possibility that recombination of erp genes is required for successful mammalian infection, we have compared the sequences of erp loci of a clonal B. burgdorferi culture with those of bacteria reisolated from immunocompetent mice chronically infected with the cloned bacteria.

Two erp loci, ospEF and p21, have previously been identified in isolate N40 (27, 56), and infected mammals produce antibodies directed against the OspE, OspF, and p21 proteins (18, 27, 36, 53, 56). In an earlier study, C3H/HeNCrlBr mice were infected by intradermal inoculation of 104 culture-grown, clonal B. burgdorferi N40 organisms (8, 19) and bacteria were reisolated from mouse tissues 1 year postinfection (8). These reisolated bacteria have also been used in two studies of other B. burgdorferi loci to assess genetic variation and stability during chronic infection (37, 49). Although the complete erp locus repertoire of isolate N40 is not known at present, analysis of the ospEF and p21 loci in these reisolates can be used to efficiently address the question of erp gene recombination during chronic mammalian infection.

Isolate N40 was originally cultured from the midgut contents of an infected tick collected in Westchester County, N.Y. (10), and has been cloned by limiting dilution (9). It is important to note that other researchers (3, 28) have used different clones of the original N40 isolate that may not be genetically related to the clone used in the present study (9). For example, an erp locus called bbk2.10, which was identified in one of these other N40 clones (3), does not appear to be present in the N40 clone we used (47).

After 1 year of infection, mouse tissues, including blood from cardiac puncture, urinary bladders, and ear pinnae, were incubated into modified Barbour-Stoener-Kelly (BSK-II) medium (6, 8). The bacteria that grew out from the tissues were frozen at −70°C. The bacteria used in the present study were reisolated from the blood of mouse 77636 (abbreviated herein as 36B), the ear and bladder of mouse 77639 (39E and 39bl, respectively), the ear and blood of mouse 77643 (43E and 43B, respectively), and the blood of mouse 77644 (44B) (mouse identification numbers are included here to permit cross-references with other studies of these bacteria [37, 49]). Aliquots (1 ml) of N40 and each reisolate were inoculated into 30 ml of BSK-II medium and grown at 35°C to late logarithmic phase (approximately 108 bacteria per ml). Bacterial plasmids were purified using with minikits (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.) as specified by the manufacturer, and DNA was resuspended in 30 μl of TE (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA).

Using purified DNA from N40 and each of the six reisolated bacteria as templates, PCR was performed with two oligonucleotide primer pairs that amplify the N40 ospEF and p21 loci (Fig. 1; Table 1). The PCR conditions were 25 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 1 min, and 65°C for 2 min in a 100-μl volume with a GeneAmp PCR system 9600 (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). Aliquots of the products of each completed reaction were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, and DNA was visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Identically sized PCR amplicons were obtained from N40 and all six reisolates with both the ospEF and p21 oligonucleotide primer pairs. No products were obtained from control PCR performed in parallel in mixtures that contained primers, nucleotides, reaction buffer, and Taq polymerase but lacked DNA. These results indicate that the oligonucleotide binding sites and the spacing between them are conserved in bacteria of all six reisolated cultures.

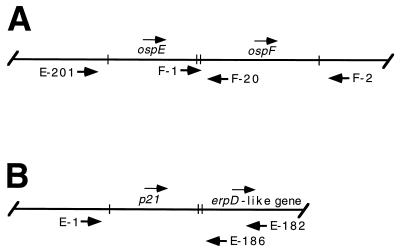

FIG. 1.

Diagrams of the N40 ospEF (A) and p21 (B) loci and locations of binding sites for oligonucleotides used in this study. The directions of transcription for ospE, ospF, p21, and a gene similar to the B31 erpD gene are indicated by arrows above the gene name. Oligonucleotide binding sites are indicated below each line, with arrows corresponding to the directions of primer extension.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this work

| Function | Our designation | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| PCR amplification and DNA sequencing | E-1 | ATGTAACAGCTGAATG |

| E-182 | GATCACCACTTTGTTCTGCTGATTTTG | |

| E-186 | AATTCTTGCAAGAAATTATCAGCG | |

| E-201 | TGTTATATAGCAAAGACTTTG | |

| F-1 | AGAAGTTGGAAGTATAGGAGAAAG | |

| F-2 | AACAATAGTTTTTGGCATTTTCAC | |

| F-20 | AATTCTTGCAAGAAACTATCAGCG | |

| Probe production | ||

| N40 ospF | F-1 | AGAAGTTGGAAGTATAGGAGAAAG |

| F-2 | AACAATAGTTTTTGGCATTTTCAC | |

| N40 erpD-like gene | E-155 | GATTTAAAACAAAATCCAGAAGGG |

| E-182 | GATCACCACTTTGTTCTGCTGATTTTG | |

| B31 erpK promoter | E-506 | AACTTTTTTTTACATCTTCACCAC |

| E-513 | CTGTTTGTTAATATGTAATAGCTG |

PCR amplicons were purified by dilution in 2 ml of distilled water and concentration to a final volume of approximately 50 μl in Centricon-100 microconcentrators (Amicon, Beverly, Mass.). Each uncloned amplicon was sequenced with N40 ospEF and p21 locus-specific oligonucleotide primers (Table 1; Fig. 1) and a model 377 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). All the amplicons yielded sequences that were identical to those of the original N40 inoculant (GenBank accession no. L13924, L13925, and L32797 for the N40 ospE, ospF, and p21 genes, respectively), indicating that the sequences of these genes remained constant during the chronic infections.

Southern blotting was used to further analyze the DNA carrying the ospEF, p21, and other erp loci in N40 and the reisolated bacteria. Two previously described probes were used that hybridize with DNA containing either ospF or the unnamed erp gene located immediately 3′ of p21 (52). This second gene of the N40 p21 locus has been only partially sequenced (47, 56) but is identical to the erpD gene of B. burgdorferi B31 (54) throughout its known sequence. A third probe was derived from the promoter region of the erpK locus of B. burgdorferi B31 (15), a region of DNA that is very similar in every known Lyme disease spirochete erp locus (2, 14, 15, 27, 31, 50, 52, 54, 56, 57). Probes were produced from cloned templates by PCR with the oligonucleotide primer pairs listed in Table 1; the reaction conditions consisted of 20 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. The reaction products were diluted 100-fold in water, subjected to a second round of PCR amplification, and purified in Centricon-100 microconcentrators as described above. Aliquots of the final PCRs were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining to ensure that amplification yielded only the appropriate, single product. Probes were labeled with [α-32P]dATP (ICN, Irvine, Calif.) by random priming (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.).

Purified plasmid DNAs from N40 and the reisolated bacteria were digested with restriction endonucleases and separated on 0.8% agarose gels by pulsed-field electrophoresis with program 0 of a Minipulse power inverter (International Biotechnologies, New Haven, Conn.). The DNAs were transferred (43) to Biotrans nylon membranes (ICN), which were then incubated overnight with each probe in 6× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate [pH 7.0])–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–5 g of nonfat dried milk per liter (32). Probes derived from the ospF and erpD-like genes were incubated with membranes at 55°C, while the erp promoter probe was incubated at 45°C. The membranes were washed in either 0.2× SSC–0.1% SDS at 55°C (for the ospF and erpD-like gene probes) or 2× SSC–0.1% SDS at room temperature (for the erp promoter probe). Hybridized probes were visualized by autoradiography. The membranes were stripped of hybridized probes by extensive washing with boiling water before reuse, and probe removal was confirmed by overnight exposure to X-ray film.

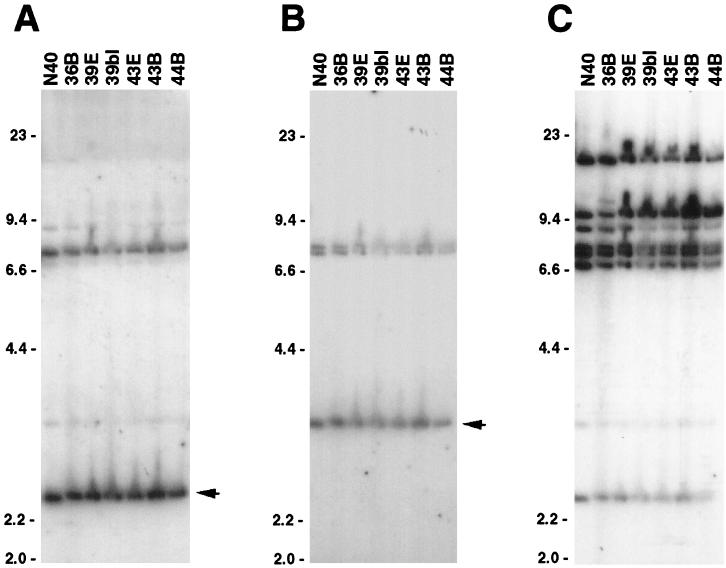

The ospF-derived probe hybridized with an approximately 2.5-kb EcoRI fragment of N40 and each reisolate (Fig. 2A), as would be expected from the previously determined restriction map of the N40 ospEF-carrying plasmid, cp18 (52). This probe, which spans the entire ospF gene, also yielded weaker hybridization signals from additional DNA fragments, presumably due to cross-hybridization with other erp genes, many of which are known to have very similar amino-terminal coding sequences (2, 3, 14, 15, 27, 31, 50, 52, 54, 56, 57). The erpD-like gene probe hybridized with an approximately 3-kb EcoRI fragment of N40 and each reisolate (Fig. 2B), consistent with the EcoRI cleavage pattern of the 32-kb plasmid that carries the p21 locus (47, 52). This probe also weakly hybridized with two additional EcoRI fragments in all seven isolates, indicating the presence of additional loci that are similar to the gene adjacent to p21. Similar results with both probes were obtained in experiments with DNA digested by other restriction endonucleases (data not shown). These data suggest that the plasmids carrying the ospEF, p21, and other, related loci are stable during chronic mammalian infection.

FIG. 2.

Southern blots of EcoRI-digested plasmid DNAs from N40 and six reisolated bacteria. Membranes were hybridized with probes derived from the N40 ospF gene (A), the N40 erpD-like gene located immediately 3′ of p21 (B), and the promoter region of the B31 erpK locus (C). Arrows to the right of A and B indicate EcoRI bands with sizes predicted from the restriction maps of the N40 ospEF and p21 loci, respectively (47, 52). DNA size markers (in kilobases) are indicated to the left of each panel.

We next used the probe derived from the B31 erpK promoter to further assess the stability of other erp locus-containing plasmids. This probe hybridized with eight discrete EcoRI fragments of N40 plasmids (Fig. 2C), indicating that these bacteria contain multiple erp loci, as do all other isolates of B. burgdorferi that have been studied in detail. With one exception, Southern blotting of DNA from the reisolated bacteria produced the same banding pattern as the inoculant N40. Similar results were also obtained from Southern blotting of plasmids digested with other restriction endonucleases (data not shown). One variation was noted, in reisolate 36B, which showed hybridization of this probe with an additional EcoRI fragment of approximately 11 kb (Fig. 2C). This reisolate was previously found to also lack the ospD gene and its plasmid, while N40 and the other reisolates contain that gene (37). Although it appears that a cp32 plasmid of reisolate 36B has acquired a mutation since the bacteria were inoculated into the mouse, it should be noted that none of the remaining reisolates exhibited evidence of cp32 alteration: the restriction endonuclease recognition sequences all remained constant in their spacing. While the additional erp loci of N40 and the reisolates were not characterized at the sequence level, these Southern blotting data again suggest that recombination of erp loci is not essential for mammalian infection.

Previous analysis of B. burgdorferi erp loci uncovered evidence of past recombination events involving both segments of erp genes and large fragments of their plasmids (51). The results presented here cannot exclude the possibility that undetected erp variants arose during the chronic infections: it may be that the infected mice contained variants that failed to grow out in culture medium or that the cultures contained bacteria with variant erp loci that were not PCR amplified or sequenced. However, the present study indicates that after 1 year of infecting immunocompetent mice, B. burgdorferi contained ospEF and p21 loci identical to those of the inoculant organisms, and argues for stability of all the erp genes during mammalian infection. We conclude from these results that recombination of erp loci is not required for chronic mammalian infection and occurs either at very low frequencies during mammalian infection or at some other point(s) in the B. burgdorferi infectious cycle.

Three of the reisolates were cultured from the blood of infected animals, where they would have been exposed to the host immune system, an observation that suggests that B. burgdorferi does not produce Erp proteins throughout the entire course of mammalian infection. A limited duration of Erp protein synthesis is consistent with observations by other researchers that immunoglobulin G and M antibodies directed against Erp proteins appeared within the first 2 to 4 weeks of mouse infection but that their levels declined during later stages of infection (3, 18). It is possible, however, that B. burgdorferi synthesizes Erp proteins throughout the course of mammalian infection but that the bacteria are in some manner “masked” to prevent recognition by the immune system. Bacteria may also reside in tissues that are not readily accessible to antibodies or other immune system components, although the presence of bacteria in the blood of three chronically infected mice argues against this hypothesis. Clearly, further studies are required to conclusively answer the question of Erp protein synthesis during mammalian infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by startup money provided by the University of Kentucky College of Medicine (to B.S.).

We thank S. Barthold and G. Terwilliger for providing bacterial strains, C. Luke for providing the BSK-II formulation, J. Miller and K. Babb for their constructive comments on the manuscript, and G. Cothran and L. Blackstones for their assistance in DNA sequencing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akins D R, Bourell K W, Caimano M J, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. A new animal model for studying Lyme disease spirochetes in a mammalian host-adapted state. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:2240–2250. doi: 10.1172/JCI2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akins D R, Caimano M J, Yang X, Cerna F, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. Molecular and evolutionary analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi 297 circular plasmid-encoded lipoproteins with OspE- and OspF-like leader peptides. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1526–1532. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1526-1532.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akins D R, Porcella S F, Popova T G, Shevchenko D, Baker S I, Li M, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. Evidence for in vivo but not in vitro expression of a Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein F (OspF) homologue. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:507–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appel M J G, Allan S, Jacobson R H, Lauderdale T L, Chang Y F, Shin S J, Thomford J W, Todhunter R J, Summers B A. Experimental Lyme disease in dogs produces arthritis and persistent infection. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:651–64. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.3.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbour A G. Antigenic variation of a relapsing fever Borrelia species. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1990;44:155–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.44.100190.001103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbour A G. Isolation and cultivation of Lyme disease spirochetes. Yale J Biol Med. 1984;57:521–525. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barthold S W. Antigenic stability of Borrelia burgdorferi during chronic infections of immunocompetent mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4955–4961. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.4955-4961.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barthold S W, Bockenstedt L K. Passive immunizing activity of sera from mice infected with Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4696–4702. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4696-4702.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barthold S W, de Souza M S, Janotka J L, Smith A L, Persing D H. Chronic Lyme borreliosis in the laboratory mouse. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:959–972. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barthold S W, Moody K D, Terwilliger G A, Duray P H, Jacoby R O, Steere A C. Experimental Lyme arthritis in rats infected with Borrelia burgdorferi. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:842–846. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.4.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benach J L, Bosler E M, Hanrahan J P, Coleman J L, Habicht G S, Bast T F, Cameron D J, Ziegler J L, Barbour A G, Burgdorfer W, Edelman R, Kaslow R A. Spirochetes isolated from the blood of two patients with Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:740–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198303313081302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgdorfer W, Barbour A G, Hayes S F, Benach J L, Grunwaldt E, Davis J P. Lyme disease—a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science. 1982;216:1317–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.7043737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Callister S M, Schell R F, Case K L, Lovrich S D, Day S P. Characterization of the borreliacidal antibody response to Borrelia burgdorferi in humans: a serodiagnostic test. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:158–164. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casjens, S., N. Palmer, R. van Vugt, W. M. Huang, B. Stevenson, P. Rosa, R. Lathigra, G. Sutton, J. Peterson, R. J. Dodson, D. Haft, E. Hickey, M. Gwinn, O. White, and C. Fraser. The twelve linear and nine circular extrachromosomal DNAs of an infectious isolate of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Casjens S, van Vugt R, Tilly K, Rosa P A, Stevenson B. Homology throughout the multiple 32-kilobase circular plasmids present in Lyme disease spirochetes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:217–227. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.217-227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cassatt D R, Patel N K, Ulbrandt N D, Hanson M S. DbpA, but not OspA, is expressed by Borrelia burgdorferi during spirochetemia and is a target for protective antibodies. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5379–5387. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5379-5387.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coleman J L, Rogers R C, Benach J L. Selection of an escape variant of Borrelia burgdorferi by use of bacteriocidal monoclonal antibodies to OspB. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3098–3104. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.8.3098-3104.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das S, Barthold S W, Stocker Giles S, Montgomery R R, Telford S R, Fikrig E. Temporal pattern of Borrelia burgdorferi p21 expression in ticks and the mammalian host. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:987–995. doi: 10.1172/JCI119264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Souza M S, Smith A L, Beck D S, Terwilliger G A, Fikrig E, Barthold S W. Long-term study of cell-mediated responses to Borrelia burgdorferi in the laboratory mouse. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1814–1822. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1814-1822.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fikrig E, Bockenstedt L K, Barthold S W, Chen M, Tao H, Ali-Salaam P, Telford S R, Flavell R A. Sera from patients with chronic Lyme disease protect mice from Lyme borreliosis. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:568–574. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.3.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fikrig E, Tao H, Kantor F S, Barthold S W, Flavell R A. Evasion of protective immunity by Borrelia burgdorferi by truncation of outer surface protein B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4092–4096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayes S F, Burgdorfer W, Barbour A G. Bacteriophage in the Ixodes dammini spirochete, etiological agent of Lyme disease. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:1436–1439. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.3.1436-1439.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humphrey S B, Stanton T B, Jensen N S, Zuerner R L. Purification and characterization of VSH-1, a generalized transducing bacteriophage of Serpulina hyodysenteriae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:323–329. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.323-329.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jauris-Heipke S, Liegl G, Preac-Mursic V, Robler D, Schwab E, Soutschek E, Will G, Wilske B. Molecular analysis of genes encoding outer surface protein C (OspC) of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato: relationship to ospA genotype and evidence of lateral gene exchange of ospC. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1860–1866. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1860-1866.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kochi S K, Johnson R C. Role of immunoglobulin G in killing of Borrelia burgdorferi by the classical complement pathway. Infect Immun. 1988;56:314–321. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.2.314-321.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kornblatt A N, Steere A C, Brownstein D G. Experimental Lyme disease in rabbits: spirochetes found in erythema migrans and blood. Infect Immun. 1984;46:220–223. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.1.220-223.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lam T T, Nguyen T-P K, Montgomery R R, Kantor F S, Fikrig E, Flavell R A. Outer surface proteins E and F of Borrelia burgdorferi, the agent of Lyme disease. Infect Immun. 1994;62:290–298. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.290-298.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leong J M, de Vargas L M, Isberg R R. Binding of cultured mammalian cells to immobilized bacteria. Infect Immun. 1992;60:683–686. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.683-686.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livey I, Gibbs C P, Schuster R, Dorner F. Evidence for lateral transfer and recombination in OspC variation in Lyme disease Borrelia. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:257–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18020257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lovrich S D, Callister S M, Schmitz J L, Alder J D, Schell R F. Borreliacidal activity of sera from hamsters infected with the Lyme disease spirochete. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2522–2528. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2522-2528.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marconi R T, Sung S Y, Norton Hughes C A, Carlyon J A. Molecular and evolutionary analyses of a variable series of genes in Borrelia burgdorferi that are related to ospE and ospF, constitute a gene family, and share a common upstream homology box. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5615–5626. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5615-5626.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Margolis N, Hogan D, Tilly K, Rosa P A. Plasmid location of Borrelia purine biosynthesis gene homologs. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6427–6432. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6427-6432.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moody K D, Barthold S W, Terwilliger G A, Beck D S, Hansen G M, Jacoby R O. Experimental chronic Lyme borreliosis in Lewis rats. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;42:165–174. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.42.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nadelman R B, Wormser G P. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 1998;352:557–565. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neubert U, Schaller M, Januschke E, Stolz W, Schmieger H. Bacteriophages induced by ciprofloxacin in a Borrelia burgdorferi skin isolate. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1993;279:307–315. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen T-P K, Lam T T, Barthold S W, Telford S R, Flavell R A, Fikrig E. Partial destruction of Borrelia burgdorferi within ticks that engorged on OspE- or OspF-immunized mice. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2079–2084. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.2079-2084.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Persing D H, Mathiesen D, Podzorski D, Barthold S W. Genetic stability of Borrelia burgdorferi recovered from chronically infected immunocompetent mice. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3521–3527. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3521-3527.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piesman J, Dolan M C, Happ C M, Luft B J, Rooney S E, Mather T N, Golde W T. Duration of immunity to reinfection with tick-transmitted Borrelia burgdorferi in naturally infected mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4043–4047. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4043-4047.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porcella S F, Popova T G, Akins D R, Li M, Radolf J D, Norgard M V. Borrelia burgdorferi supercoiled plasmids encode multi-copy tandem open reading frames and a lipoprotein gene family. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3293–3307. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3293-3307.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts E D, Bohm R P, Lowrie R C, Habicht G, Katona L, Piesman J, Phillip M T. Pathogenesis of Lyme neuroborreliosis in the rhesus monkey: the early disseminated and chronic phases of disease in the peripheral nervous system. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:722–732. doi: 10.1086/515357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosa P A, Schwan T, Hogan D. Recombination between genes encoding major outer surface proteins A and B of Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3031–3040. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sadziene A, Rosa P A, Thompson P A, Hogan D M, Barbour A G. Antibody-resistant mutants of Borrelia burgdorferi: in vitro selection and characterization. J Exp Med. 1992;176:799–809. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.3.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmitz J L, Schell R F, Hejka A G, England D M. Passive immunization prevents induction of Lyme arthritis in LSH hamsters. Infect Immun. 1990;58:144–148. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.1.144-148.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwan T G, Karstens R H, Schrumpf M E, Simpson W J. Changes in antigenic reactivity of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete, during persistent infection in mice. Can J Microbiol. 1991;37:450–454. doi: 10.1139/m91-074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steere A C, Grodzicki R L, Kornblatt A N, Craft J E, Barbour A G, Burgdorfer W, Schmid G P, Johnson E, Malawista S E. The spirochetal etiology of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:733–740. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198303313081301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stevenson, B. Unpublished results.

- 48.Stevenson B, Barthold S W. Expression and sequence of outer surface protein C among North American isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;124:367–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stevenson B, Bockenstedt L K, Barthold S W. Expression and gene sequence of outer surface protein C of Borrelia burgdorferi reisolated from chronically infected mice. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3568–3571. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3568-3571.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stevenson B, Bono J L, Schwan T G, Rosa P. Borrelia burgdorferi Erp proteins are immunogenic in mammals infected by tick bite, and their synthesis is inducible in cultured bacteria. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2648–2654. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2648-2654.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stevenson B, Casjens S, Rosa P. Evidence of past recombination events among the genes encoding the Erp antigens of Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiology. 1998;144:1869–1879. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-7-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stevenson B, Casjens S, van Vugt R, Porcella S F, Tilly K, Bono J L, Rosa P. Characterization of cp18, a naturally truncated member of the cp32 family of Borrelia burgdorferi plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4285–4291. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4285-4291.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stevenson B, Schwan T G, Rosa P A. Temperature-related differential expression of antigens in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4535–4539. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4535-4539.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stevenson B, Tilly K, Rosa P A. A family of genes located on four separate 32-kilobase circular plasmids in Borrelia burgdorferi B31. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3508–3516. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3508-3516.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stoenner H G, Dodd T, Larsen C. Antigenic variation in B. hermsii. J Exp Med. 1982;156:1297–1311. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.5.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suk K, Das S, Sun W, Jwang B, Barthold S W, Flavell R A, Fikrig E. Borrelia burgdorferi genes selectively expressed in the infected host. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4269–4273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sung S Y, Lavoie C P, Carlyon J A, Marconi R T. Genetic divergence and evolutionary instability in ospE-related members of the upstream homology box gene family in Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex isolates. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4656–4668. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4656-4668.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Theisen M, Borre M, Mathiesen M J, Mikkelsen B, Lebech A-M, Hansen K. Evolution of the Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein OspC. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3036–3044. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3036-3044.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Theisen M, Frederiksen B, Lebech A-M, Vuust J, Hansen K. Polymorphism in ospC gene of Borrelia burgdorferi and immunoreactivity of OspC protein: implications for taxonomy and for use of OspC protein as a diagnostic antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2570–2576. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2570-2576.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wallich R, Brenner C, Kramer M D, Simon M M. Molecular cloning and immunological characterization of a novel linear-plasmid-encoded gene, pG, of Borrelia burgdorferi expressed only in vivo. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3327–3335. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3327-3335.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang J-R, Hardham J M, Barbour A G, Norris S J. Antigenic variation in Lyme disease borreliae by promiscuous recombination of VMP-like sequence cassettes. Cell. 1997;89:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang J-R, Norris S J. Genetic variation of the Borrelia burgdorferi gene vlsE involves cassette-specific, segmental gene conversion. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3698–3704. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3698-3704.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang J-R, Norris S J. Kinetics and in vivo induction of genetic variation of vlsE in Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3689–3697. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3689-3697.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zückert W R, Meyer J. Circular and linear plasmids of Lyme disease spirochetes have extensive homology: characterization of a repeated DNA element. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2287–2298. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2287-2298.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]