Abstract

Introduction:

In 2007, the first formal postgraduate nurse practitioner (NP) residency program was launched at Community Health Center, Inc., a large Federally Qualified Health Center in Connecticut, and focused on primary care and community health. There are numerous post-graduate nurse practitioner training programs across the nation, and many more are under development. Although the literature describes the impact of postgraduate residency training programs on new NPs’ early practice transition, to date, no studies have examined the long-term impact of postgraduate NP training programs on alumni’s career choices, practice, and satisfaction. This study sought to understand the impact over time of Community Health Center Inc.’s postgraduate NP residency program on the subsequent career paths of alumni who completed the program between 2008 and 2019. Additionally, it explored alumni’s current reflections on the impact of their postgraduate residency training on their transition to the post-residency year and beyond, as well as their professional development and career choices. Moreover, it sought to identify any previously undocumented elements of impact for further exploration in subsequent studies.

Methods:

This was a retrospective cohort study that used an electronic survey and interviews. All 90 of the alumni who had completed Community Health Center Inc.’s residency between 2008 and 2019 were invited to participate.

Results:

The survey’s response rate was 72%. Most (74%) of the participating alumni indicated they were still practicing as primary care providers. Of these, 57% were practicing at FQHCs. Nine subthemes were identified from the interviews, with an overarching theme that the program was foundational to a successful career in community-based primary care and that the impact of the program continues to evolve.

Conclusion:

Community Health Center Inc.’s postgraduate NP residency program had a long-standing impact on alumni’s commitment to continuing in primary care practice, as well as their engagement in leadership activities to ensure quality care.

Keywords: primary care, access to care, underserved communities, nurse practitioner residency, professional satisfaction, federally qualified health center (FQHC), nurse practitioner transition

For almost 2 decades, the need for and potential benefit of formal postgraduate residency training for new nurse practitioners (NPs) have been discussed.1-3 The challenges of transitioning from student to practicing NP are well documented,4-7 as is the fact that a significant number of NPs desire postgraduate residency training.8,9 However, the absence of any formal financial mechanism, such as federal Graduate Medical Education funding, that supports medical and dental residencies, or Teaching Health Center funding that supports physician and dentist residencies in Federally Qualified Health Centers (https://bphc.hrsa.gov/about-health-centers/what-health-center) specifically, is an obvious barrier. In 2010, the Institute of Medicine recommended postgraduate training programs for all nurses, including advanced practice nurses, upon completion of their education and whenever they transition to new practice areas.10 However, despite this recommendation, there has not been an organized call for postgraduate training for NPs by the nursing community.

In 2007, Community Health Center, Inc., a large, multi-site Federally Qualified Health Center in Connecticut (https://chc1.com), launched the first formal postgraduate NP residency program in the U.S. with an original cohort of 4 family nurse practitioners.11 This 12-month program was designed to help new NPs develop confidence and competence in the provision of health care services for individuals with clinical and social complexities who seek services from Federally Qualified Health Centers and other safety-net health settings. Core elements of the program include precepted continuity clinics, specialty rotations, weekly didactic sessions, and quality improvement seminars. Additionally, residents learn hands-on clinical skills (eg, suturing, performing biopsies, inserting intrauterine devices, etc.). Moreover, due to the rise in opioid use disorder, residents also become certified in medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder.12

Over the last 15 years, the Community Health Center Inc.’s postgraduate NP residency program has grown substantially, and as of 2022, it accepts up to 18 NP residents a year, including family nurse practitioners, adult-gerontology nurse practitioners, pediatric nurse practitioners, and psychiatric mental health nurse practitioners.12 Additionally, other Federally Qualified Health Centers, the Veterans Health Administration, and numerous health systems across the U.S. have also developed postgraduate NP residencies. In the absence of a single source of verifiable information about the total number of programs today, we note that as of July 21, 2022, the National Nurse Practitioner Residency and Fellowship Training Consortium had documented 333 post-graduate NP residency and fellowship programs, of which 166 were either primary care or mental health programs, and 110 were located in Federally Qualified Health Centers.13 Moreover, the advent of federal funding opportunities for post-graduate nurse NP residency programs through the Bureau of Health Workforce of Health Resources Services Administration14 in 2019 has resulted in the funding of 36 programs in 24 states,15 spurring further development of these programs, particularly in Federally Qualified Health Centers, and emphasizing the value of partnerships with academic institutions.

Additionally, a small but growing body of literature has developed around NP residency program structure, impact, evaluation, comparative effectiveness, clinical outcomes, and professional satisfaction,16-19 along with qualitative studies of the experience of the transition of new NPs as experienced during a formal postgraduate residency training program.20,21 Although NP residency programs differ in mission, length, and curricula, formal standards and an accreditation commission specific to postgraduate NP residency and fellowship programs have been developed.22 Additionally, the accreditation commission of the National Nurse Practitioner Residency and Fellowship Training Consortium is now recognized by the U.S. Department of Education.23

Although the literature describes the impact of postgraduate residency training programs on new NPs’ early practice transition,16-21 to date, no published studies have examined the sustained impact of postgraduate NP residency training programs on alumni practice and careers. This study sought to understand the impact over time of Community Health Center, Inc.’s postgraduate NP residency program on the subsequent career paths of alumni who completed the program between 2008 and 2019. Additionally, the study explored alumni’s current reflections on the impact of their postgraduate residency training experience on their transition to the post-residency year and beyond, as well as their professional development and career choices. Moreover, the study sought to identify any previously undocumented elements of impact for further exploration in subsequent studies.

Methods

This mixed methods study was approved by the Community Health Center Inc.’s Institutional Review Board (IRB ID: 1168) and consisted of a survey sent to all Community Health Center Inc.’s NP alumni (n = 90; 86 family nurse practitioners and 4 psychiatric mental health nurse practitioners) who graduated between 2008 and 2019, followed by interviews with willing participants.

The confidential survey was created in Qualtrics, a web-based survey tool. Survey items included current demographic information of program alumni with specific focus on their current professional role, clinical setting, and population(s) served, as well as practice and leadership activities since completion of the program. The survey also included 3 questions to assess current satisfaction with their professional role, leadership development and growth opportunities, and future intention to practice. The survey was sent via email from an independent Qualtrics email address on August 27th, 2020, and closed October 22nd, 2020.

The survey’s last item asked if participants would be willing to be contacted for an interview. Those who indicated interest in an interview were emailed to arrange an interview date and time. Interviews were conducted over a secure zoom link by the first author, who has no affiliation with Community Health Center Inc. These semi-structured interviews were informed by interpretive phenomenology, which aims to gain a deeper understanding of a lived experience.24 At the beginning of each interview, the following statement was shared with participants on the zoom screen and was also read aloud: “ I am interested in hearing about your experience following completion of the NP residency program, your professional and career satisfaction, and any impact that you think the NP residency program has had on your career. Can you please tell me about these?.” Participants were then asked to respond to this question, while the interviewer asked clarifying questions and made summative comments for confirmation. Periodically, the interviewer would ask the participant to relook at the research question to see if they had anything to add. Interviews ended when participants indicated they had nothing else to share and after all clarifying questions had been answered and summative comments had been confirmed. The interviews were transcribed verbatim and reviewed for accuracy by the interviewer.

Interviews were analyzed independently by all 3 researchers using a thematic analysis approach,25 consisting of (1) an “open-read” of a transcribed interview in its entirety with the purpose of developing familiarity with the participant’s narrative and appreciating the overall interview’s dialog and flow; (2) analysis of each transcribed interview line for meaning, where relevant quotes were highlighted and described using the author’s own short code; and (3) constant data comparison throughout the entire process, where previous and new interview codes were compared and updated accordingly. After performing steps 1 to 3 with the first 3 interviews, the researchers met to compare findings. Although there was some variation in how the 3 researchers labeled codes, there was no significant variation in their analyses. Using this same process, the researchers analyzed the remaining 7 interviews and performed an independent theme analysis using all the existing codes. They then met to discuss these themes, and although there were minor differences in how the researchers labeled themes, there were no significant differences in the nature of the themes.

Results

Survey

There were 65 participants (72% response rate). None of the 4 psychiatric mental health nurse practitioners responded, thus all the participants were family nurse practitioners. The majority of participants were female, in the 35 to 44 years age range and identified as Caucasian. Additionally, 78% had been at their current position for 4 years or less. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics (n = 65).

| Age range (at time of survey) | Total # | % |

|---|---|---|

| 25-34 years | 27 | 41.5 |

| 35-44 years | 35 | 53.8 |

| 45-54 years | 1 | 1.5 |

| 55+ years | 1 | 1.5 |

| Did not respond | 1 | 1.5 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Asian | 4 | 6.15 |

| Black/African American | 8 | 12.31 |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 7 | 10.77 |

| Native American/Native Alaskan | 1 | 1.54 |

| White/Caucasian | 48 | 73.85 |

| Preferred not to answer | 1 | 1.54% |

| More than one race/ethnicity | 4 | 6.15% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1 | 1.54 |

| Female | 63 | 96.92 |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 1.54 |

Clinical practice post-program

Of the participants, 60 (92%) were working as a NP in clinical practice in some capacity, and just under half reported having more than 1 job role. Two participants who were not working indicated that they were “taking a break” or “raising children.”

Practice setting

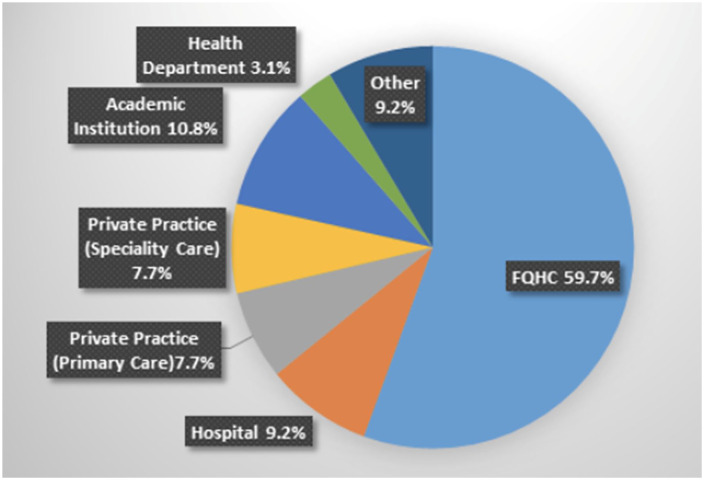

Most (74%) of the participants indicated they were practicing as primary care providers, and the majority (57%) were practicing at a Federally Qualified Health Center (See Figure 1). Other roles included administration and leadership; academia, including research and teaching at 9 different institutions, as well as enrollment in a Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) program; self-employment (not otherwise specified), and starting an international non-profit organization. Additionally, most of the participants were serving one or more underserved populations, including those with opioid use disorder (60%), homeless individuals (59%); women’s reproductive healthcare (47%); those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered, queer, and other sexual identifies (LGBTQ+, 35%); those who have human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease and/or hepatitis C virus (32%); migrant farm workers (8%); and children in school-based health centers (4%). (See Figure 2). Of note, 65% of the participants who were practicing in primary care indicated holding a DEAX waiver to prescribe Buprenorphine.

Figure 1.

Current work setting (n = 65).

Figure 2.

Percent of participants caring for specific underserved populations.

Residency involvement

Regarding involvement in other NP residency and fellowship programs, 42% of the participants indicated that they had or were currently precepting NP residents, and 20% had been involved in the development or launch of a postgraduate NP residency or fellowship program. Beyond residency specific training, 52% of the participants reported precepting NP students.

Post-program education and training

Since completion of the program, 32% of the participants had obtained additional degrees, certifications, or training. The most commonly earned degree was a DNP, which 12 participants indicated completing since completing the program. Other degrees included a Master’s of Public Health (MPH). Participants also reported earning post-master certifications in each of the following areas: adult-gerontology acute-care NP, education, and health innovation, as well as certifications in holistic nursing and lactation. Several participants had also completed a Center for Key Population Fellowship26 an opportunity that became available in 2017.

Perceived impact of the program on current practice/career

The majority of the participants indicated that the program impacted their clinical practice (89%), career development (74%), and leadership development (52%) “to a great degree” or “to a considerable degree” (Figure 3). Additionally, all of the participants indicated that NP residency programs were important in today’s healthcare environment (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Impact of NP residency program on clinical practice and career development (n = 65).

Figure 4.

Importance of NP residency programs in today’s health care environment (n = 65).

Interviews

Of the participating participants, 37 (57%) agreed to be contacted to be interviewed, 10 of whom were randomly selected by program cohort year to allow for a variety of perspectives as the program has evolved over time. Analysis of the interviews resulted in 9 subthemes:

(1) Training in a high-performing Federally Qualified Health Center: Training in a highly organized system that identified and resolved practice issues, responded to community needs, and employed a systematic process for quality improvement, was essential to the participants’ success; (2) Witnessing visionary leadership: Experiencing leaders within the organization, whose words and actions demonstrated respect for NPs and high-quality primary care, had a powerful influence on participants; (3) Supportive, expert clinicians: Having dedicated preceptors who cared about their learning and progress was essential to the residency experience; (4) Emphasis on quality for improvement of patient care and system challenges: The program’s emphasis on delivering high quality patient care and the need to implement system changes to improve patient care was deeply impressed on participants; (5) Confidence in clinical skills: During the program, participants developed confidence in their abilities to manage complex care and complex patients (eg, procedures and patients experiencing chronic pain, multiple comorbidities, challenging situations); (6) Providing better patient care: Participating in the program led to better patient experiences and outcomes; (7) Burnout prevention: By participating in the program, residents learned skills and approaches to prevent professional burnout; (8) Marketability: Simply having completed a postgraduate residency helped participants compete well for positions. Specific skills also improved their marketability: complex care skills, transgender care, chronic pain, quality improvement skills, systems perspective, etc.; and (9) Extreme gratitude: Participants were incredibly grateful for the program and could not imagine their current successes without having participated in it. See Table 2 for example quotations of these subthemes.

Table 2.

Interview Subthemes and Example Quotations (Presented In No Particular Order).

| (1) Training in a high-performing FQHC |

| During the residency at Community Health Center, Inc., I was exposed to a lot of really great leaders, nurse practitioner and physician leaders. They were able to teach me how to time manage, multi-task, see patients, be effective in charting, but then still be able address all the patient issues. I also learned hands-on skills like suturing, skin tag removal, a lot of procedures, as well as joint injections. So I was really glad that I was able to have exposure to these. |

| From doing the residency at Community Health Center, Inc., I know what high quality is and how to get there, and years later, I still feel like I’m taking lessons from that. |

| (2) Witnessing visionary leadership |

| In the last year, a number of nurse practitioners (in my current position) have started to self-organize and advocate for a lead nurse practitioner position, someone to be our voice and to represent us at the leadership level. And that is actually going really well. We’ve had some meetings with administration, and it sounds like that is going to happen. And I think doing the residency at Community Health Center, Inc. and seeing a nurse practitioner in a top leadership role, someone who really believes in what nurse practitioners are doing and what we’re capable of, was powerful. |

| I witnessed really good leader role models in the residency. I still remember (names 3 preceptors). I still remember the providers who, even though you’re seeing the patient, they kind of l trigger you to think more, like, what would you do, what else would you do? Or being involved in grand rounds makes you think beyond what you have in front of you. The Weitzman Symposium was another great exposure to leadership. I remember all of this. So being exposed to all of these great leaders, I learned to advocate and think outside of the box. |

| (3) Supportive, expert clinicians |

| The focus (of the residency) was on learning—clinical preceptors whose job it is to talk with you about cases, which led me to feeling like I’m doing a better job, I’m honoring my patients better. I’m providing better care when I’m talking about patients with preceptors. |

| I needed the type of kindness that they (the preceptors) offered me. They were empathetic and understanding. They went above and beyond to ensure that I could keep moving forward. And I needed that support, especially at a time when I was experiencing very early imposter-like syndrome that we (other residents) were all going through at the time when you’re starting out new. They were encouraging and they saw my potential, and on a daily basis, they helped me grow. And I think if I were to sum it up, I couldn’t have been who I am now without having had support and that very important first year in community health. |

| (4) Emphasis on quality for improvement of patient care and system challenges |

| When I was at Community Health Center, Inc. and the residency, I was exposed to the NCQA (National Committee for Quality Assurance). I learned about NCQA, and the medical patient medical home recognition. So as I learned about and experienced these, I knew that this was what I needed to look for in future positions. I’ll definitely want to work in a setting that is committed to quality improvement. |

| From doing the residency at Community Health Center, Inc., I know that I need the focus on quality. I need the, “What are we doing? Are we doing it all? We’re all together. We’re all focused on this mission.” And when I don’t have that, I am not satisfied with my job. And I think it’s because NP residency had that, and I loved it. |

| (5) Confidence in clinical skills |

| I don’t know that I would have been able to obtain training for procedures if I had not gone to a residency or fellowship, because you’re often left with going to a CME (continuing medical education) seminar on doing a skills training, and then hoping that you (1) have patients who need those procedures so that you can actually build that skill or (2) have a mentor who works at that clinic that also does those procedures who can observe you doing them so that then you can credentialed to do them. And if you don’t have either of those things, then it’s hard to really build the skills to say that you can do them. So because I did the program, I was able to get a lot of experience doing IUDs (intrauterine devices) and Nexplanons and suturing and skin biopsies and those types of things. |

| If I hadn’t learned them (procedural skills) in the residency, I wouldn’t be doing them today. |

| (6) Providing better patient care: Participating in the program led to better patient experiences and outcomes. |

| If you aren’t comfortable doing skills, you have to refer a patient out, and especially if a patient has state insurance, and there’s maybe only one dermatology clinic that accepts the state’s insurance, or maybe no one accepts it, then the patient has to go to another town. And if the town doesn’t have public transportation, or maybe there is a clinic in town, but it’s about 6 months until the patient is going to have an appointment. So I’m not going to be much help to patients if I say, “Yes, you have a problem, but I can’t help you with it.” Because of the residency and the skills I’ve mastered, I can at least do something. |

| Because of the residency, I am now the leading adult provider at _____ (a Federally Qualified Health Center) in all of their quality measures, that’s including physicians. I have been able to sustain in the top 3 since I started. My panel has more than 300 patients with diabetes, and my care has been able to get 85% of them to reach an A1c of less than 9%. |

| (7) Burnout prevention |

| I think the real purpose of the residency is to give you the skills you need to survive with longevity in community health. So I think that that’s kind of big picture — how the residency has shaped my experience, because I’m now nearing my fifth year of practice, and I’m still here. |

| I prioritize the career I have chosen over jumping ship. And especially over the last few months, it was extremely tempting to specialize or apply for jobs in specialty care or things that are a little bit more niche. But I think that the residency program has definitely contributed to my longevity in primary care. |

| (8) Marketability |

| I feel like doing the residency and learning everything that I learned helped to open doors within the FQHC (Federally Qualified Health Center) world. People knew that I was qualified. There wasn’t a concern of, “As a new NP, is she going to crash and burn?” |

| People were more interested in me because I had the residency, and it gave me more confidence to practice and more experience in a safe setting. |

| (9) Extreme gratitude |

| I couldn’t be where I am today without having done an NP residency program. I’m not just saying that because this is an interview. It’s because I needed the additional support to do this job. |

| I think the nurse practitioner residency was invaluable in continuing and solidifying my education. It focused my education on how to be a good primary care nurse practitioner in a federally qualified health center in a moderately urban setting. It was invaluable. And the way that I learned to practice was important. The focus on taking one’s time and asking questions, cultivating a respect for the history-gathering and the diagnostic assessment process and the respect for the longitudinal relationships with patients, as well as a respect for the value of your work community and helping to contribute to a collaborative environment in a clinic. Where I’m working now at ____ (a Federally Qualfied Health Center), I’m the only nurse practitioner working with physicians. And, I am grateful for the residency program for preparing me for this. |

The overarching theme of the interviews was that the program was foundational to the participants’ successful careers in community primary care. Its impact has been longstanding and continues to evolve. In the words of 2 alumni participants:

I think nurse practitioner postgraduate training programs allow us to be part of conversations regarding advocacy and how we can ensure that we’re all providing quality services for our patients. As a graduate of the residency, I continue to have an impact, not just on one-to-one 15 min (patient) appointments, but on a larger conversation, increased diversity in the workforce, leadership in nursing, making sure that we have advocacy in nursing, making sure we’re present so that our patients understand that we provide high quality services and then ensuring that the next generation (of new NPs) doesn’t get “eaten by the wolves.”

During the residency, I saw best practice and was able to compare this to what it’s like everywhere else. Because of the residency, I’m now a change agent. I’m going to continue to be a change agent, and I don’t know exactly what that’s going to mean, but I am.

Discussion

The original intension of Community Health Center Inc.’s postgraduate NP residency program was to provide new NPs with the opportunity to develop increased competence, confidence and mastery in the care of patient populations who are seen in Federally Qualified Health Centers and other safety-net health settings. These early programs focused on family nurse practitioners, as reflected in the population of study here; however, programs have since expanded to include adult, pediatric, and psychiatric mental health NPs as well.

Overall, the residency experience of the participants in this study was between 1 and 13 years prior to the study. Most were still engaged in clinical practice, with the majority practicing in primary care and just over half practicing at Federally Qualified Health Centers. This consideration is of particular interest for questions around impact of postgraduate NP training programs, which suggests that even many years after graduation, programs may continue influence participants’ career choices and clinical practice.

We note that Federally Qualified Health Centers are on the front lines of responding to changes in the healthcare needs of vulnerable populations. The participants all experienced caring for patients with substance use disorder, particularly, opioid use disorder, during their residency year. The U.S. continues to be involved in an opioid epidemic. The NP residency’s curriculum intentionally includes training to support residents’ confidence and competence in treating opioid use disorder. Since 2016, when NPs were able to start prescribing buprenorphine in Connecticut, Community Health Center Inc.’s program has required buprenorphine waiver training as part of the curriculum. This survey reflects responses from cohorts since the inaugural class, when NPs were not able to prescribe buprenorphine, through 2019, with nearly 60% of the participants actively prescribing buprenorphine.

The competence, confidence, and mastery the participants indicated developing during the program was transformative. The clinical and leadership skills developed were transferable to any organization. However, what they learned from Community Health Center Inc.’s commitment to having and using a method for continuous performance improvement, which was deeply impressed upon them, was not always embedded in other organizations. The participants frequently spoke of looking for support in making practice improvements and changes. If they were not successful in getting support for performance improvement, they would sometimes move on and look for another organization where they could effect change.

The participants perceived that they were very well qualified for practice and better prepared than their peers who had not completed a residency program, and some indicated that they were qualified with clinical skills beyond other experienced providers. They expressed being particularly well prepared in procedural skills, as well as the capacity to care for all age groups. They were not willing to relinquish these skills for practices in which NPs did not currently provide these services, and if this was the case, they worked to effect changes to allow them to continue to deliver these services.

Most participants felt that the postgraduate program was very important in today’s healthcare environment. Many were precepting NP residents, and it is striking that 20% had been or were involved in developing or leading formal postgraduate NP residency training programs.

In the 2 years since the survey was actually sent, in part due to the impact of the COVID pandemic, there has been renewed focus on clinician burnout and the need to prevent burnout and promote resiliency and well-being at every level of our health care system. In the current health system, where burnout is high, we need to consider that the participants identified the experience as a preventive measure for burnout.

Of note, this study also uncovered 2 previously unidentified impacts of postgraduate NP residency on these NP resident alumni: (1) the impact of doing the program within a high-performing organization and (2) the impact of experiencing visionary leadership that respected and acknowledged NP contributions.

Limitations

The study was conducted only with individuals who had completed a postgraduate NP residency training program at Community Health Center Inc., thus the findings are not generalizable to all postgraduate NP training program. However, the participants had all been assigned to one of 5 different primary care sites for the duration of their NP residency experience. Although the residency model, standards of care, and organization of care is the same at each site, there were obviously differences among sites, which likely contributed to some variation in the residents’experiences. Having said this, the fact that there was general consistency across participants’survey and interview data indicates that the alumni had similar residency experiences. The psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner residency was created in 2018 and had only 4 alumni at the time the survey was launched. There were no responses from the psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner cohort, thus the results are exclusively based on the family nurse practitioner respondents. Additionally, the Community Health Center, Inc. implemented post-graduate residency programs for adult-gerontology and pediatric nurse practitioners after this study had launched, thus these residents were not included in this study.

The survey was sent in August of 2020, approximately 6 months into the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the tremendous impact of the global pandemic on health-related professions, we recognize that this timing likely had an impact on responses and the response rate. For example, some participants indicated that they were working in COVID-related roles, such as testing or result notification, which were not job options in the U.S. prior to 2020.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the sustained impact of postgraduate NP training on alumni careers. The findings demonstrate the long-standing impact of Community Health Center Inc.’s postgraduate NP residency program on alumni’s commitment to continuing in primary care practice, specifically safety-net health settings, as well as their engagement in leadership activities to ensure quality care. Similar studies are needed with alumni from other postgraduate NP training programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge May Oo, MPH, senior research/evaluation associate at the Weitzman Institute of CHCI., for her assistance with survey administration, as well as data extraction and analysis. They also acknowledge Charise Corsino, MA, program director of CHCI’s NP residency training program, and Hannah Beath, program specialist for CHCI’s NP residency training program, for their contributions to the survey’s development.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Ann Marie Hart  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7826-4327

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7826-4327

References

- 1. Flinter M. Residency programs for primary care nurse practitioners in federally qualified health centers: a service perspective. Online J Issues Nurs. 2005;10(3):6. doi:10.3912/OJIN. Vol10No03Man05. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sargent L, Olmedo M. Meeting the needs of new-graduate nurse practitioners: a model to support transition. J Nurs Adm. 2013;43(11):603-610. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000434506.77052.d2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wiltse Nicely KL, Fairman J. Postgraduate nurse practitioner residency programs: supporting transition to practice. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):707-709. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Faraz A. Novice nurse practitioner workforce transition into primary care: a literature review. West J Nurs Res. 2016;38(11):1531-1545. doi: 10.1177/0193945916649587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moran GM, Nairn S. How does role transition affect the experience of trainee advanced clinical practitioners: qualitative evidence synthesis. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(2):251-262. doi: 10.1111/jan.13446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Faraz A. Facilitators and barriers to the novice nurse practitioner workforce transition in primary care. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2019;31(6):364-370. doi: 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barnes H. Exploring the factors that influence nurse practitioner role transition. J Nurs Pract. 2015;11(2):178-183. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2014.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Faraz A. Factors Influencing the Successful Transition and Turnover Intention of Novice Nurse Practitioners in the Primary Care Workforce. Order No, 3663512 ed. Yale University; 2015. Accessed March 15, 2022. https://www.libproxy.uwyo.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/factors-influencing-successful-transition/docview/1701275205/se-2?accountid=1479 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hart AM, Bowen A. New nurse practitioners’ perceptions of preparedness for and transition into practice. J Nurs Pract. 2016;12(8):545-552. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2016.04.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Institute of Medicine. The Future of Nursing: Focus on Nursing Education. National Academies Press; 2011:11. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Flinter M. From new nurse practitioner to primary care provider: bridging the transition through FQHC-based residency training. Online J Issues Nurs. 2011;17(1):6. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol17No01PPT04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Community Health Center, Inc. Nurse practitioner residency and training consortium. 2022. Accessed March 15, 2022. https://www.npresidency.com/

- 13. National Nurse Practitioner Residency and Fellowship Training Consortium. Primary care and psychiatric mental health NP and NP/PA postgraduate residency and fellowship training programs across the country. July 21, 2022. Accessed July 24, 2022. https://nppostgradtraining.com/postgraduate-training/locations/

- 14. Health Resources Services Administration. Health center program award recipients. June 2022. Accessed September 1, 2022. https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/eligibility-and-registration/health-centers/fqhc

- 15. Health Resources & Services Administration. Advanced nursing education nurse practitioner residency (ANE-NPR) program award table. December 2020. Accessed April 29, 2022. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/funding/advanced-nursing-education-nurse-practitioner-residency-2019-awards

- 16. Bush CT, Lowery B. Postgraduate nurse practitioner education: impact on job satisfaction. J Nurse Pract. 2016;12(4):226-234. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2015.11.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rugen KW, Dolansky MA, Dulay M, King S, Harada N. Evaluation of veterans affairs primary care nurse practitioner residency: achievement of competencies. Nurs Outlook. 2018;66(1):25-34. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parkhill H. Effectiveness of residency training programs for increasing confidence and competence among new graduate nurse practitioners. 2018. Accessed March 15, 2022. https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/son_dnp/29/

- 19. Park J, Faraz Covelli A, Pittman P. Effects of completing a postgraduate residency or fellowship program on primary care nurse practitioners' transition to practice. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2021;34(1):32-41. doi: 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Flinter M. From new nurse practitioner to primary care provider: A multiple case study of new nurse practitioners who completed a formal post-graduate residency training. Doctoral Dissertations. AAI3411460. 2010. Accessed March 15, 2022. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/AAI3411460/

- 21. Flinter M, Hart AM. Thematic elements of the postgraduate NP residency year and transition to the primary care provider role in a federally qualified health center. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2017;7(1):95-106. doi: 10.5430/jnep.v7n1p9528435479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. National Nurse Practitioner Residency and Fellowship Training Consortium. Postgraduate nurse practitioner training program accreditation standards. October 2019. Accessed March 15, 2022. https://www.nppostgradtraining.com/accreditation/standards/

- 23. Provencio-Johnson O. The consortium receives federal recognition as accrediting agency by the U.S. department of education. National nurse practitioner residency and fellowship training consortium. January 31, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2022. https://www.nppostgradtraining.com/2022/01/31/the-consortium-receives-federal-recognition-as-accrediting-agency-by-the-u-s-department-of-education/

- 24. Matua GA, Van Der Wal DM. Differentiating between descriptive and interpretive phenomenological research approaches. Nurse Res. 2015;22(6):22-27. doi: 10.7748/nr.22.6.22.e1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sundler AJ, Lindberg E, Nilsson C, Palmér L. Qualitative thematic analysis based on descriptive phenomenology. Nurs Open. 2019;6(3):733-739. doi: 10.1002/nop2.275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nurse Practitioner Residency Training Program. Center for key populations fellowship. 2022. Accessed November 4, 2022. https://www.npresidency.com/program/center-for-key-populations-fellow/