Abstract

The therapeutic relationship has emerged as one of the most important components of successful treatment outcomes, regardless of the specific form of therapy. Research has now turned its attention to better understanding how the therapeutic relationship contributes to patient improvement. Extant literature contends that a strong therapeutic relationship may help reduce a patient’s sense of existential isolation (i.e., a sense of not feeling understood by others). Research indicates that existential isolation might be especially problematic for men, potentially increasing their risk for suicidality. This study investigated the association between strength of the therapeutic relationship and psychological distress and suicidality among men who received psychotherapy, and whether existential isolation mediated this association. A total of 204 Canadian men who had previously attended psychotherapy participated in a cross-sectional survey, completing measures of the quality of their most recent therapeutic relationship, existential isolation, depression and anxiety symptoms, and suicidality. Regression with mediation analysis was conducted. Two models were tested; one with depression/anxiety symptoms as the dependent variable and the other with suicidality as the dependent variable. Both mediation models emerged as significant, indicating an indirect effect for quality of the therapeutic relationship on symptoms of anxiety/depression and suicidality through existential isolation. The findings suggest that a positive therapeutic relationship can contribute to men feeling less isolated in their experiences in life (i.e., less existentially isolated), thereby helping mitigate psychological distress and suicidality.

Keywords: therapeutic alliance, feeling understood, psychotherapy, psychological distress, suicidality, men

Introduction

Suicide is a leading cause of death of men worldwide (Naghavi, 2019) and is increasingly being recognized as a major public health issue. Spurred by the high rates of male suicide across the globe (Richardson et al., 2021), there has been a significant increase in research and a rapid advancement in our understanding of the risks for and manifestations of men’s mental health challenges, including suicidality (Castle & Coghill, 2021; Oliffeet al., 2020). Relatively less attention has been devoted to studying men’s outcomes in the context of psychotherapy as a potential remedy for psychological distress and male suicidality (Bedi & Richards, 2011; Seidler, Rice, Ogrodniczuk, et al., 2018). Social narratives espousing masculine ideals of strength, autonomy, and emotional stoicism position psychological treatment as the “antithesis of masculinity” to explain men’s lower treatment engagement and higher suicide rates (Eggenberger et al., 2021; Oliffe et al., 2016; Pederson & Vogel, 2007). As Seidler and colleagues (2020) point out, men do seek help, with recent reports demonstrating a consistent rise in the number of men seeking services for mental health concerns (Ogrodniczuk, Rice, Kealy, et al., 2021; Sharp et al., 2022). Research has demonstrated that most men who do seek care endorse a strong preference for psychotherapy (Kealy et al., 2021; Sierra Hernandez et al., 2014).

Within psychotherapy, the establishment of a strong patient–therapist relationship (i.e., therapeutic relationship) is the foundational feature of a beneficial treatment experience (Muran & Barber, 2010). Research has consistently demonstrated that more positive client impressions of the therapeutic relationship during treatment are associated with a decrease in psychological distress both during and after treatment (Flückiger et al., 2018; Wampold, 2015). Strong therapeutic relationships also have the capacity to decrease suicidal ideation among psychotherapy clients (Barzilay et al., 2020; Dunster-Page et al., 2017; Huggett et al., 2022). Although studies focused on psychotherapeutic processes (including the therapeutic relationship) of men in psychotherapy are rare, the available evidence links strong therapeutic relationships to decreased distress and suicidality in men (Lindner, 2006; Seidler, Rice, Oliffe, et al., 2018).

Although the robust association between a strong therapeutic relationship and reduced distress/suicidal ideation is well documented, much less is known about the mechanisms underlying this association. One potential mechanism concerns the sense of being understood by others (or lack thereof), which largely corresponds to the concept of existential isolation–a feeling of profound seclusion in one’s experience of life (Yalom, 1980). In order for an individual to feel comfortable with who they are, they need to know that what occurs in their mind—their perspectives of themselves and the world around them—makes sense. Individuals learn that their thoughts and feelings make sense through interactions with others. When an individual expresses themselves, and another person makes a sincere attempt to understand their perspective and communicate that understanding, the individual internalizes the idea that they are understandable; in other words, they feel understood rather than isolated in their experience of life. Not feeling understood by people (i.e., feeling existentially isolated) has been associated with various aspects of psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, stress (Constantino et al., 2019; Morelli et al., 2014), loneliness (Cox et al., 2020), and suicidality (Helm et al., 2019, 2020). Research suggests that existential isolation might be especially problematic for men (Helm et al., 2018), potentially increasing their risk for distress symptoms and suicidality. This links to masculine socialization and the notion that men’s emotional communication should be stymied and replaced with stoicism. Men are left with fewer outlets to both share and hear others’ internal experiences, limiting the ability for them to feel understood. Within the context of psychotherapy, authors have contended that feeling understood by one’s therapist is a critical aspect of a positive therapeutic experience (Krause et al., 2011), and that a strong therapeutic relationship helps increase one’s sense of feeling understood (i.e., reduces existential isolation; Zilcha-Mano & Barber, 2018). Although available literature suggests that feeling understood might serve as a mediator of the association between the strength of a therapeutic relationship and psychological distress, no study has examined this possibility.

The present study aimed to improve our current understanding of the role of the therapeutic relationship in psychotherapy for male clients by examining whether existential isolation mediated the association between the strength of a therapeutic relationship and psychological distress (including suicidality) in a community sample of men who had previously received psychotherapy. Two models were tested; one focused on depressive/anxious symptoms, the other focused on current suicidality. To account for their potentially confounding effects, age, general impact of COVID-19 on mental health, and time since previous therapy were included as covariates in each model; the model for suicidality also included current depressive/anxious symptoms as an additional covariate. It was hypothesized that more positive assessments of one’s therapeutic relationship would be associated with less existential isolation, which in turn would be associated with lower psychological distress and suicidal ideation.

Method

Procedures and Participants

Data for this study were provided by a sample of 204 Canadian men who participated in a larger cross-sectional survey that took place during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (Ogrodniczuk, Rice, Kealy, et al., 2021). In this study, only participants who indicated they had previous therapy experience, but were not currently in therapy, were included (n = 204). Participants were recruited through the HeadsUpGuys website (https://headsupguys.org), a leading global resource that provides practical tips, tools, information about professional services and personal recovery stories to help men battle depression and prevent suicide (Ogrodniczuk, Beharry, & Oliffe, 2021). Men who expressed interest in participating were directed to an independent survey site hosted by Qualtrics, where they were presented with the informed consent page. A $500 (CAD) prize draw was offered to participants to incentivize participation in the study. Eligibility criteria included being at least 18 years old, having online access, being able to read and understand English, self-identifying as male, and residing in Canada. No exclusion criteria were specified. Those providing informed consent to participate completed the survey online. Participant IP addresses and study ID numbers were associated with the collected data, which was stored on a password-protected, secured Canadian server. Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Behavioural Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia (H20-01401).

Measures

Psychological Distress

The Patient Health Questionnaire–4 (PHQ-4; Kroenke et al., 2009) is a four-item self-report questionnaire developed to measure psychological distress associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety. The items are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale (0 = not at all to 3 = almost every day), with the total score representing severity of symptoms associated with depression and anxiety. In this study, the scale showed good internal consistency (α = .87).

Suicidal Ideation

Suicidal ideation was assessed using a single item (Item 9) derived from the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001). Item 9 has been established as an effective predictor of future suicide attempts in health clinic outpatients (Simon et al., 2013). The item asks respondents “In the last two weeks, how often have you been bothered by: Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way” and was rated on a 4-point scale anchored at 0 (not at all) and 3 (nearly every day). Greater suicidal ideation is indicated by higher scores on the item.

Patient–Therapist Relationship

Client perspectives of the therapeutic relationship were assessed using a single item. Participants were asked to answer the question “How would you rate your relationship with the therapist you saw”; it was implied that this referred to the last therapist they saw. Ratings were reported on a scale from 1 (excellent) to 5 (poor). Single-item measures of self-rated mental health constructs are being used increasingly in health research and population health surveys (Ahmad et al., 2014), and previous alliance-focused research investigating the use of a single-item approach has demonstrated that long versus single-item measures of the therapeutic relationship are strongly correlated (Bickman et al., 2012).

Existential Isolation

The six-item Existential Isolation Scale (EIS) was used to assess existential isolation (Pinel et al., 2017). Items included “I often have the same reactions to things that other people around me do” (reverse coded), and “Other people usually do not understand my experiences.” Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) and an aggregate score was calculated, with high scores representing greater existential isolation. Cronbach’s alpha was .85 in this study.

Time Since Previous Therapy

Time since previous therapy was assessed using a single item. Participants were asked to respond to the question “How long ago was your counseling/psychotherapy.” Response options included “Within the past year,” “1–2 years ago,” and “More than 2 years ago.”

General Impact of COVID-19

General impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on one’s mental health was assessed using a single item. Participants responded to the question “To what extent has COVID-19 affected your mental health?” using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (very positively) to 5 (very negatively). This item was reverse-coded for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS version 25 and the PROCESS macro version 3.5 (Hayes & Rockwood, 2017). Regression with mediation analysis (PROCESS Model 4) was employed to test two models. The first model used the PHQ-4 total score (psychological distress) as the dependent variable, and the second model used the Item 9 score from the PHQ-9 (suicidal ideation) as the dependent variable. In each model, the therapeutic relationship score served as the independent variable, and existential isolation scores were included as the mediator. Time since previous therapy, general impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on one’s mental health, and age were included in the models as covariates to account for their potential confounding effects. In the second model, the PHQ-4 total score was also included as a covariate in the analysis, as it was moderately correlated with the Item 9 suicidal ideation score r(202) = .532, p < .001. Bootstrapped 95% percentile confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using 10,000 re-samples. The statistical significance of an indirect effect of the therapeutic relationship—via existential isolation—on psychological distress (i.e., symptoms of depression/anxiety) and suicidality would, thus, be indicated by the CI not including zero.

Results

The mean age of survey respondents was 40.6 years (SD =13.95; range = 19–79). The majority were Caucasian (77.5%; n = 158), educated beyond high school (88.2%; n = 180), employed full-time (47.1%; n = 96), and had an annual personal income of $50,000 CAD or less (54.4%; n = 111). Most men self-identified as heterosexual (65.7%; n = 134), were in a relationship (55.4%; n = 113), and currently lived with their partner/children/extended family (57.4%; n = 117). With regard to time since previous therapy, 32.8% (n = 67) received therapy within the past year, 20.1% (n = 41) received therapy in the past 1 to 2 years, and 47.1% (n = 96) received therapy more than 2 years ago.

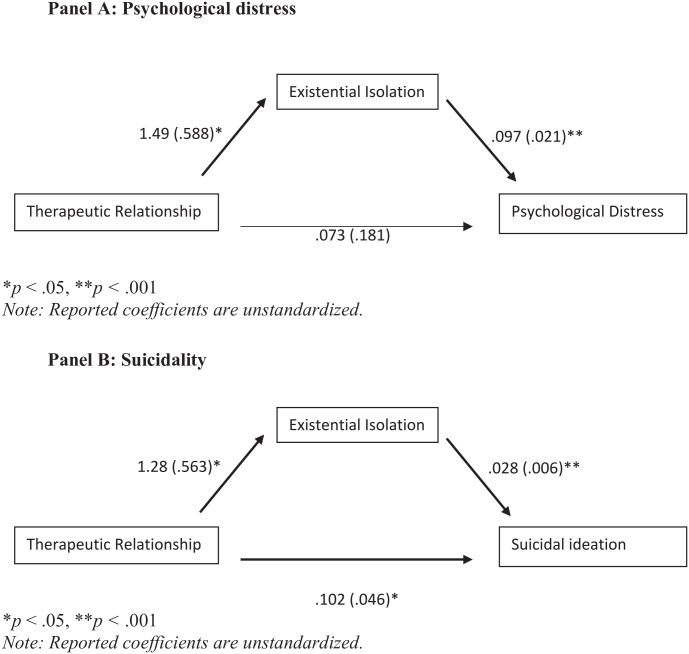

The results of the regression analysis with the PHQ-4 total score serving as the dependent variable (see Table 1; Figure 1, Panel A) indicated that the therapeutic relationship had a significant association with existential isolation (B = 1.49, t = 2.54, p < .05). In turn, existential isolation had a significant association with symptoms of anxiety/depression (B = .097, t = 4.55, p < .001). The findings revealed a significant indirect effect (unstandardized coefficient indicating a mediation effect) of the therapeutic relationship on symptoms of anxiety/depression through existential isolation (B = .145, SE = .07, 95% CI = [.029, .306]). This finding revealed that an increasingly positive therapeutic relationship was associated with less existential isolation. In turn, lower existential isolation was associated with reduced symptoms of anxiety/depression. Similar findings emerged from the mediation analysis involving suicidality as the dependent variable (see Table 2; Figure 1, Panel B). A significant indirect effect (unstandardized coefficient indicating a mediation effect) was observed for the therapeutic relationship on suicidality through existential isolation (B = .036, SE = .017, 95% CI = [.0053, .0705]). A stronger therapeutic relationship was associated with less existential isolation (B = 1.27, t = 2.27, p < .05), which in turn was related to lower suicidality (B = .028, t = 4.85, p < .001).

Table 1.

Results of Process Examining the Relationship Between Therapeutic Relationships, Existential Isolation, and Psychological Distress (Model 1).

| DV: Existential isolation | Coeff. | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship with therapist | 1.49 | .588 | 2.538 | .012 |

| Time since therapy | −.214 | .811 | −.2635 | .792 |

| Effects of COVID-19 on mental health | −.11 | .86 | −.1279 | .898 |

| Age | −.051 | .052 | −.9791 | .329 |

| R2 = .0375, F(4, 199) = 1.941, p = .105 | ||||

| DV: Psychological distress (PHQ-4) | Coeff. | SE | t | p |

| Relationship with therapist | .073 | .181 | .4066 | .685 |

| Existential isolation | .097 | .021 | 4.547 | <.001 |

| Time since therapy | −.142 | .245 | −.5793 | .5631 |

| Effects of COVID-19 on mental health | 1.52 | .26 | 5.83 | <.001 |

| Age | −.02 | .016 | −1.295 | .1968 |

| R2 = .263, F(5, 198) = 14.156, p < .001 | ||||

| Effect | SE | Lower CI | Upper CI | |

| Indirect effect of therapeutic relationship on distress through existential isolation | .145 | .071 | .0294 | .3055 |

Note. Indirect effects estimated using bootstrap 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (10,000 resamples). Reported regression coefficients are unstandardized. DV = dependent variable; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire; Coeff. = coefficient.

Figure 1.

Process Modeling of the Relationship Between the Therapeutic Relationship, Existential Isolation, and Psychological Distress/Suicidality: Panel A: Psychological Distress and Panel B: Suicidality

Note. Reported coefficients are unstandardized.

*p < .05. **p < .001.

Table 2.

Results of Process Examining the Relationship Between Therapeutic Relationships, Existential Isolation, and Suicidal Ideation (Model 2).

| DV: Existential isolation | Coeff. | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship with therapist | 1.28 | .563 | 2.274 | .024 |

| Psychological distress | .97 | .213 | 4.547 | <.001 |

| Time since therapy | −.056 | .775 | −.0719 | .943 |

| Effects of COVID-19 on mental health | −1.57 | .881 | −1.783 | .076 |

| Age | −.026 | .05 | −.527 | .599 |

| R2 = .129, F(5, 198) = 5.842, p < .001 | ||||

| DV: Suicidal ideation (9, PHQ-9) | Coeff. | SE | t | p |

| Relationship with therapist | .102 | .046 | 2.229 | .027 |

| Existential isolation | .028 | .006 | 4.853 | <.001 |

| Psychological distress | .111 | .018 | 6.183 | <.001 |

| Time since therapy | −.132 | .062 | −2.127 | .035 |

| Effects of COVID-19 on mental health | .102 | .071 | 1.429 | .155 |

| Age | .006 | .004 | 1.369 | .173 |

| R2 = .398, F(6, 197) = 21.663, p < .001 | ||||

| Effect | SE | Lower CI | Upper CI | |

| Indirect effect of therapeutic relationship on suicidal ideation through existential isolation | .0355 | .017 | .0053 | .0705 |

Note. Indirect effects estimated using bootstrap 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (10,000 resamples). Reported regression coefficients are unstandardized. DV = dependent variable; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire; Coeff. = coefficient.

Discussion

Consistent with our hypotheses, the findings of the present study demonstrated that stronger therapeutic relationships were significantly associated with reduced existential isolation, which was associated with decreased psychological distress (i.e., symptoms of depression and anxiety) and suicidality. These results held even after controlling for age, time since previous therapy, and the general impact of COVID on one’s mental health. The findings, thus, provide preliminary evidence for existential isolation serving as a mediator in the relationship between the quality of the therapeutic relationship and psychological distress/suicidality for men who had undertaken psychotherapy.

With regard to the finding of a more positive therapeutic relationship being related to reduced existential isolation, it may be that telling one’s story in one’s own terms and having it heard respectfully by someone who is perceived as warm, trust-worthy, non-judgmental and empathic can lead to one feeling validated and understood (Pocock, 1997). Consistent with this is the conclusion by Dore and Alexander (1996) that most therapeutic relationship measures seem to tap key experiences of “having someone there for me,” ‘being accepted’ and “feeling understood” in a purposeful, collaborative relationship. Research on misunderstanding events in psychotherapy points to how this process can be compromised, demonstrating that a key factor leading to clients not feeling understood was therapists not being open to discussing negative client experiences (Rhodes et al., 1994). Furthermore, these muted interactions tended to lead to premature termination of therapy, a common occurrence for men who undertake psychotherapy (Seidler et al., 2021). Indeed, dissatisfaction with one’s therapy has been associated with increased existential isolation (Constantino et al., 2019). Considering research that has suggested that men disproportionately struggle with existential isolation (Helm et al., 2018), the findings of the present study point to the importance of cultivating a strong therapeutic relationship in psychotherapy as an effectual treatment process to help mitigate men’s sense of not feeling understood by others and thus feeling isolated in their life experiences.

This study also revealed that reduced existential isolation was associated with less psychological distress (depression, anxiety) and suicidality, which is consistent with findings from previous research (Constantino et al., 2019; Helm et al., 2020; Morelli et al., 2014). As Zilcha-Mano and Barber (2018) suggest, when an individual feels understood by others around them (i.e., less existentially isolated), they can feel a greater sense of belongingness, pursue interpersonal interactions, and behave with more agency during these interactions, further increasing their chances of feeling understood. Indeed, lower levels of existential isolation have been identified as a correlate of higher self-regard and less reactivity to perceived social slights (Pinel et al., 2017). Previous work has also suggested that men who feel more understood by others may feel more integrated in their social realm, resulting in a greater sense of social connectivity and less loneliness (Laurenceau et al., 1998) which can help mitigate psychological distress (Cacioppo et al., 2010); findings that have been confirmed by Cox and colleagues (2020), as well as Keum and colleagues (2021) in independent male-only samples. The findings of the present study may also connect with those from recent reports (Daruwala et al., 2021; Genuchi, 2019) that have examined the association between masculinity and suicidality through the lens of the interpersonal theory of suicide (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). Specifically, reduced existential isolation may help mitigate men’s sense of stoicism and self-reliance (characteristics that leave men feeling interpersonally isolated), which have been found to be associated with thwarted belongingness, a critical feature of the interpersonal theory of suicide. In the context of psychotherapy, a feeling of understanding and connection that is facilitated by a positive therapeutic relationship may enhance a man’s ability to learn from therapy and apply these lessons to life outside the therapeutic encounter, thereby reducing psychological distress and suicidality.

To capitalize on these opportunities, tailored practices geared toward the development and maintenance of the therapeutic relationship (e.g., Asnaani & Hofmann, 2012) can be implemented to improve male clients’ treatment outcomes. Considering the inevitability of strains occurring in the therapeutic relationship, the work of Muran and colleagues (2021) on delineating strategies for repairing ruptures in the relationship is also highly relevant for clinicians to consider. Therapists’ use of non-verbal communications (e.g., nods and wordless reactions, like “mhmm”), active signs of communication (e.g., mirroring the client’s feelings or suggesting insightful reflections), and explicit collaborative work on the relationship during therapy have been identified as ways therapists can cultivate a positive therapeutic relationship that contributes to clients feeling understood in therapy (Zilcha-Mano & Barber, 2018). In their review of patient–therapist synchrony in one-on-one psychotherapy, Koole and Tschacher (2016) highlighted I-sharing and affective co-regulation as important factors for developing a strong therapeutic relationship. I-sharing refers to the mutual sharing of subjective experiences, which the therapist can foster through communicating empathy, postural mirroring, and self-disclosure (Pinel et al., 2015). This practice not only promotes bonding between a client and their therapist but also decreases feelings of existential isolation (Pinel et al., 2004). Affective co-regulation, a process by which the therapist helps regulate the client’s emotions, can help enhance a client’s sense of feeling understood through the experience of having the therapist being emotionally engaged and responding to their emotional distress (Soma et al., 2020). In addition, a unique therapist training program (Men in Mind) aims to help therapists understand and respond to the complex reality of their male clients’ gendered experiences (Seidler et al., 2022). By providing context on the role of masculine development and its interactions with depression and suicidality in men’s lives, therapists are intentionally drawn to consider their own experiences and how these might intersect with that of their clients. Through the effective use of strategies such as those described above, therapists may be able to cultivate and maintain a strong therapeutic relationship, which can help reduce male clients’ existential isolation, and thereby alleviate their psychological distress and suicidality.

The findings of the present study should be considered in the context of specific limitations. Notably, the study used a single-item rating of the therapeutic relationship. Although research suggests that single-item ratings of mental health-related constructs can provide valid assessments (Ahmad et al., 2014), the field lacks sufficient research to determine whether the quality of the therapeutic relationship can be adequately captured with a single-item rating. Although a single item was also used to assess suicidality in the present study, there is ample research supporting the validity of using Item 9 from the PHQ-9 as a suicidality assessment (Kim et al., 2021). Another consideration is that client ratings of the alliance occurred after treatment had ended. Although this study controlled for time since treatment, bias in retrospective recall remains a possible limitation. The present study used a cross-sectional methodology, limiting the ability to identify causal relationships among the investigated pathways. For example, improvement in anxiety and depression symptoms during therapy may have resulted in a better therapeutic relationship. The study also lacked detail regarding the specificities of participants’ previous therapy experiences, that is, length, model, and modality, which could potentially affect the findings. Nevertheless, despite such possible variability, the findings of the present study may actually speak to the robustness of the identified mediation associations. Finally, findings from the present study may lack generalizability as a result of participant recruitment methods. As participants were recruited exclusively through the HeadsUpGuys website, they may not be fully representative of men with psychotherapy experiences in the broader community.

Conclusion

Although much has been made of prioritizing efforts that help increase men’s help-seeking and treatment uptake (Yousaf et al., 2015), it is equally important to work on ensuring that treatment is engaging and responsive to men’s needs in order for them to sustain treatment and maximize the potential for a beneficial outcome (Seidler et al., 2019). Previous research has not only linked a positive therapeutic relationship with men’s continued engagement in therapy (Kealy et al., 2019; Seidler et al., 2020) but has also demonstrated its role in helping to reduce male clients’ distress and suicidal ideation (Barzilay et al., 2020; Bryan et al., 2012). This study provided a unique expansion to the extant literature by demonstrating that a strong therapeutic relationship can contribute to men feeling understood (i.e., less existentially isolated), which contributes to a reduction in psychological distress and suicidality. These preliminary findings help elucidate one pathway by which the therapeutic relationship can contribute to positive benefits from psychotherapy for male clients and signal existential isolation as a critical factor in this pathway.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Behavioral Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia (H20-01401).

ORCID iDs: Zac E. Seidler  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6854-1554

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6854-1554

John L. Oliffe  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9029-4003

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9029-4003

Simon M. Rice  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4045-8553

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4045-8553

John S. Ogrodniczuk  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3531-9033

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3531-9033

References

- Ahmad F., Jhajj A. K., Stewart D. E., Burghardt M., Bierman A. S. (2014). Single item measures of self-rated mental health: A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 14, 398. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asnaani A., Hofmann S. G. (2012). Collaboration in multicultural therapy: Establishing a strong therapeutic alliance across cultural lines. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(2), 187–197. 10.1002/jclp.21829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilay S., Schuck A., Bloch-Elkouby S., Yaseen Z. S., Hawes M., Rosenfield P., Foster A., Galynker I. (2020). Associations between clinicians’ emotional responses, therapeutic alliance, and patient suicidal ideation. Depression and Anxiety, 37(3), 214–223. 10.1002/da.22973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi R. P., Richards M. (2011). What a man wants: The male perspective on therapeutic alliance formation. Psychotherapy, 48(4), 381–390. 10.1037/a0022424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L., de Andrade A. R. V., Athay M. M., Chen J. I., De Nadai A. S., Jordan-Arthur B. L., Karver M. S. (2012). The relationship between change in therapeutic alliance ratings and improvement in youth symptom severity: Whose ratings matter the most? Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 39(1–2), 78–89. 10.1007/s10488-011-0398-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan C. J., Corso K. A., Corso M. L., Kanzler K. E., Ray-Sannerud B., Morrow C. E. (2012). Therapeutic alliance and change in suicidal ideation during treatment in integrated primary care settings. Archives of Suicide Research, 16(4), 316–323. 10.1080/13811118.2013.722055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J. T., Hawkley L. C., Thisted R. A. (2010). Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging, 25(2), 453–463. 10.1037/a0017216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle D., Coghill D. (2021). Suicidality and mood disorders in men. In Castle D., Coghill D. (Eds.), Comprehensive men’s mental health (pp. 119–158). Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/9781108646765 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino M. J., Sommer R. K., Goodwin B. J., Coyne A. E., Pinel E. C. (2019). Existential isolation as a correlate of clinical distress, beliefs about psychotherapy, and experiences with mental health treatment. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 29(4), 389–399. 10.1037/int0000172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D. W., Ogrodniczuk J. S., Oliffe J. L., Kealy D., Rice S. M., Kahn J. H. (2020). Distress concealment and depression symptoms in a national sample of Canadian men: Feeling understood and loneliness as sequential mediators. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 208(6), 510–513. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daruwala S. E., Houtsma C., Martin R., Green B., Capron D., Anestis M. D. (2021). Masculinity’s association with the interpersonal theory of suicide among military personnel. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 51(5), 1026–1035. 10.1111/sltb.12788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore M. M., Alexander L. B. (1996). Preserving families at risk of child abuse and neglect: The role of the helping alliance. Child Abuse & Neglect, 20(4), 349–361. 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00004-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunster-Page C., Haddock G., Wainwright L., Berry K. (2017). The relationship between therapeutic alliance and patient’s suicidal thoughts, self-harming behaviours and suicide attempts: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 223, 165–174. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggenberger L., Fordschmid C., Ludwig C., Weber S., Grub J., Komlenac N., Walther A. (2021). Men’s psychotherapy use, male role norms, and male-typical depression symptoms: Examining 716 men and women experiencing psychological distress. Behavioral Sciences, 11(6), 83. 10.3390/bs11060083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flückiger C., Del Re A. C., Wampold B. E., Horvath A. O. (2018). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 316–340. 10.1037/pst0000172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genuchi M. C. (2019). Masculinity and suicidal desire in a community sample of homeless men: Bringing together masculinity and the interpersonal theory of suicide. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 27(3), 329–342. 10.1177/1060826519846428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A., Rockwood N. (2017). Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behavior Research and Therapy, 98, 39–57. 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm P. J., Greenberg J., Park Y. C., Pinel E. C. (2019). Feeling alone in your subjectivity: Introducing the state trait existential isolation model (STEIM). Journal of Theoretical Social Psychology, 3(3), 146–157. 10.1002/jts5.41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helm P. J., Medrano M. R., Allen J. J., Greenberg J. (2020). Existential isolation, loneliness, depression, and suicide ideation in young adults. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 39(8), 641–674. 10.1521/jscp.2020.39.8.641 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helm P. J., Rothschild L. G., Greenberg J., Croft A. (2018). Explaining sex differences in existential isolation research. Personality and Individual Differences, 134, 283–288. 10.1016/j.paid.2018.06.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huggett C., Gooding P., Haddock G., Quigley J., Pratt D. (2022). The relationship between the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and suicidal experiences: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 29(4), 1203–1235. 10.1002/cpp.2726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kealy D., Rice S. M., Ferlatte O., Ogrodniczuk J. S., Oliffe J. L. (2019). Better doctor-patient relationships are associated with men choosing more active depression treatment. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 32(1), 13–19. 10.3122/jabfm.2019.01.170430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kealy D., Seidler Z. E., Rice S. M., Oliffe J. L., Ogrodniczuk J. S., Kim D. (2021). Challenging assumptions about what men want: Examining preferences for psychotherapy among men attending outpatient mental health clinics. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 52(1), 28–33. 10.1037/pro0000321 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keum B. T., Oliffe J. L., Rice S. M., Kealy D., Seidler Z. E., Cox D. W., Levant R. F., Ogrodniczuk J. S. (2021). Distress disclosure and psychological distress among men: The role of feeling understood and loneliness. Current Psychology. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s12144-021-02163-y [DOI]

- Kim S., Lee H. K., Lee K. (2021). Which PHQ-9 items can effectively screen for suicide? Machine learning approaches. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3339. 10.3390/ijerph18073339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koole S. L., Tschacher W. (2016). Synchrony in psychotherapy: A review and an integrative framework for the therapeutic alliance. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 862. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause M., Altimir C., Horvath A. (2011). Deconstructing the therapeutic alliance: Reflections on the underlying dimensions of the concept. Clínica y Salud, 22(3), 267–283. 10.5093/cl2011v22n3a7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R. L., Williams J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R. L., Williams J. B. W., Lowe B. (2009). An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics (Washington, D.C.), 50(6), 613–621. 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau J. P., Barrett L. F., Pietromonaco P. R. (1998). Intimacy as an interpersonal process: The importance of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness in interpersonal exchanges. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1238–1251. 10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner R. (2006). Suicidality in men in psychodynamic psychotherapy. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 20(3), 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Morelli S. A., Torre J. B., Eisenberger N. I. (2014). The neural bases of feeling understood and not understood. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(12), 1890–1896. 10.1093/scan/nst191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muran J. C., Barber J. P. (Eds.). (2010). The therapeutic alliance: An evidence-based guide to practice. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muran J. C., Eubanks C. F., Samstag L. W. (2021). One more time with less jargon: An introduction to “rupture repair in practice.” Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77(2), 361–368. 10.1002/jclp.23105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naghavi M. (2019). Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. British Medical Journal, 364, Article 194. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30322-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogrodniczuk J. S., Beharry J., Oliffe J. L. (2021). An evaluation of 5-year web analytics for HeadsUpGuys: A men’s depression E-mental health resource. American Journal of Men’s Health, 15(6), 15579883211063322. 10.1177/15579883211063322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogrodniczuk J. S., Rice S. M., Kealy D., Seidler Z. E., Delara M., Oliffe J. L. (2021). Psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study of online help-seeking Canadian men. Postgraduate Medicine, 133(7), 750–759. 10.1080/00325481.2021.1873027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J. L., Broom A., Rossnagel E., Kelly M. T., Affleck W., Rice S. M. (2020). Help-seeking prior to male suicide: Bereaved men perspectives. Social Science & Medicine, 261, Article 113173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe J. L., Ogrodniczuk J. S., Gordon S. J., Creighton G., Kelly M. T., Black N., Mackenzie C. (2016). Stigma in male depression and suicide: A Canadian sex comparison study. Community Mental Health Journal, 52(3), 302–310. 10.1007/s10597-015-9986-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson E. L., Vogel D. L. (2007). Male gender role conflict and willingness to seek counseling: Testing a mediation model on college-aged men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(4), 373–384. 10.1037/0022-0167.54.4.373 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinel E. C., Bernecker S. L., Rampy N. M. (2015). I-sharing on the couch: On the clinical implications of shared subjective experience. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 25(2), 59–70. 10.1037/a0038895 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinel E. C., Long A. E., Landau M., Pyszczynski T. (2004). I-sharing, the problem of existential isolation, and their implications for interpersonal and intergroup phenomena. In Greenberg J., Koole S. L., Pyszczynski T. (Eds.), Handbook of experimental existential psychology (pp. 352–368). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pinel E. C., Long A. E., Murdoch E. Q., Helm P. (2017). A prisoner of one’s own mind: Identifying and understanding existential isolation. Personality and Individual Differences, 105, 54–63. 10.1016/j.paid.2016.09.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock D. (1997). Feeling understood in family therapy. Journal of Family Therapy, 19, 283–302. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes R. H., Hill C. E., Thompson B. J., Elliott R. (1994). Client retrospective recall of resolved and unresolved misunderstanding events. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 41(4), 473–483. 10.1037/0022-0167.41.4.473 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson C., Robb K. A., O’Connor R. C. (2021). A systematic review of suicidal behaviour in men: A narrative synthesis of risk factors. Social Science & Medicine, 276, 113831. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler Z. E., Rice S. M., Kealy D., Oliffe J. L., Ogrodniczuk J. S. (2020). Once bitten, twice shy: Dissatisfaction with previous therapy and its implication for future help-seeking among men. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 55(4), 255–263. 10.1177/0091217420905182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler Z. E., Rice S. M., Ogrodniczuk J. S., Oliffe J. L., Dhillon H. M. (2018). Engaging men in psychological treatment: A scoping review. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(6), 1882–1900. 10.1177/1557988318792157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler Z. E., Rice S. M., Ogrodniczuk J. S., Oliffe J. L., Shaw J. M., Dhillon H. M. (2019). Men, masculinities, depression: Implications for mental health services from a Delphi expert consensus study. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 50(1), 51–61. 10.1037/pro0000220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler Z. E., Rice S. M., Oliffe J. L., Fogarty A. S., Dhillon H. M. (2018). Men in and out of treatment for depression: Strategies for improved engagement. Australian Psychologist, 53(5), 405–415. 10.1111/ap.12331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler Z. E., Wilson M. J., Kealy D., Oliffe J. L., Ogrodniczuk J. S., Rice S. M. (2021). Men’s dropout from mental health services: Results from a survey of Australian men across the life span. American Journal of Men’s Health, 15(3), 15579883211014776. 10.1177/15579883211014776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler Z. E., Wilson M. J., Toogood N., Oliffe J. L., Kealy D., Ogrodniczuk J. S., Owen J., Lee G., Rice S. M. (2022). Pilot evaluation of the men in mind training program for mental health practitioners. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 23(2), 257–264. 10.1037/men0000383 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp P., Bottorff J. L., Rice S., Oliffe J. L., Schulenkorf N., Impellizzeri F., Caperchione C. M. (2022). “People say men don’t talk, well that’s bullshit”: A focus group study exploring challenges and opportunities for men’s mental health promotion. PLOS ONE, 17(1), Article e0261997. 10.1371/journal.pone.0261997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra Hernandez C. A., Oliffe J. L., Joyce A. S., Söchting I., Ogrodniczuk J. S. (2014). Treatment preferences among men attending outpatient psychiatric services. Journal of Mental Health, 23(2), 83–87. 10.3109/09638237.2013.869573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon G. E., Rutter C. M., Peterson D., Oliver M., Whiteside U., Operskalski B., Ludman E. J. (2013). Does response on the PHQ-9 depression questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death? Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 64(12), 1195–1202. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soma C. S., Baucom B., Xiao B., Butner J. E., Hilpert P., Narayanan S., Atkins D. C., Imel Z. E. (2020). Coregulation of therapist and client emotion during psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 30(5), 591–603. 10.1080/10503307.2019.1661541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden K. A., Witte T. K., Cukrowicz K. C., Braithwaite S. R., Selby E. A., Joiner T. E., Jr. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575–600. 10.1037/a0018697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wampold B. E. (2015). How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry, 14(3), 270–277. 10.1002/wps.20238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalom I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf O., Grunfeld E. A., Hunter M. S. (2015). A systematic review of the factors associated with delays in medical and psychological help-seeking among men. Health Psychology Review, 9(2), 264–276. 10.1080/17437199.2013.840954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilcha-Mano S., Barber J. P. (2018). Facilitating the sense of feeling understood in patients with maladaptive relationships. In Tishby O., Wiseman H. (Eds.), Developing the therapeutic relationship: Integrating case studies, research, and practice (pp. 105–131). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/0000093-006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]