Abstract

The circadian rhythm is a biological oscillation of physiological activities with a period of approximately 24 h, that is driven by a cell-autonomous oscillator called the circadian clock. The current model of the mammalian circadian clock is based on a transcriptional-translational negative feedback loop in which the protein products of clock genes accumulate in a circadian manner and repress their own transcription. However, several studies have revealed that constitutively expressed clock genes can maintain circadian oscillations. To understand the underlying mechanism, we expressed Bmal1 in Bmal1-disrupted cells using a doxycycline-inducible promoter and monitored Bmal1 and Per2 promoter activity using luciferase reporters. Although the levels of BMAL1 and other clock proteins, REV-ERBα and CLOCK, showed no obvious rhythmicity, robust circadian oscillation in Bmal1 and Per2 promoter activities with the correct phase relationship was observed, which proceeded in a doxycycline-concentration-dependent manner. We applied transient response analysis to the Bmal1 promoter activity in the presence of various doxycycline concentrations. Based on the obtained transfer functions, we suggest that, at least in our experimental system, BMAL1 is not directly involved in the oscillatory process, but modulates the oscillation robustness by regulating basal clock gene promoter activity.

Subject terms: Circadian rhythms, Biochemistry, Biophysics

Introduction

Circadian rhythms are biological oscillations of various physiological activities, such as sleep–wake cycles, hormone secretion, and metabolism, with a period of approximately 24 h. Circadian rhythms are driven by an endogenous, cell-autonomous oscillator called the circadian clock1. Currently, the molecular mechanism of the circadian clock is understood to be based on a transcriptional-translational negative feedback loop (TTFL), in which the translational product of clock genes represses their own transcription1,2. In mammals, the circadian clock is thought to consist of an essential core loop and a subsidiary ROR/REV/Bmal1 loop, which are interlocked to generate a stable circadian oscillation3. In the core loop, the BMAL1-CLOCK heterodimer activates the transcription of period (Per1 and Per2) and cryptochrome (Cry1 and Cry2) through E-box motifs located in the promoter region4,5. The translational products of Per and Cry form a heterodimer that translocates into the nucleus, where it represses the transcription of their own mRNAs by inhibiting BMAL1-CLOCK function6,7. Thus, Per and Cry transcription and translation and the accumulation of their transcriptional and translational products oscillate in a circadian manner8,9. In the ROR/REV/Bmal1 loop, Bmal1 transcription is regulated by ROR transcriptional activators (RORα, RORβ, and RORγ)10 and the inhibitors REV-ERBs (REV-ERBα and REV-ERBβ)11–13. RORs and REV-ERBs compete for RORE regulatory elements located in the promoter region of Bmal114, resulting in circadian oscillation in Bmal1 transcription. Conversely, transcription of RORs and REV-ERBs is activated by the BMAL1-CLOCK heterodimer, which also oscillates in a circadian manner12.

In TTFL models, oscillations in the transcriptional and translational products of clock genes are required for the circadian clock that allow cells to “tell time”2. However, several studies revealed that rhythmic clock gene expression is not essential for the circadian clock. For example, Bmal1 expressed from a constitutive promoter can restore circadian oscillations in Per2 promoter (PPer2) activity in Bmal1−/− fibroblast cells15. Cell-permeant CRY1 and CRY2 proteins can rescue the arrhythmic phenotype of Cry1−/−Cry2−/− fibroblasts when applied to culture media16. Furthermore, constitutive Per2 expression in Per1−/−Per2−/− mice restores the circadian rhythm of PPer2 activity at the cellular level, but also rescues sleep/wake cycles in the organism17. Therefore, it is generally believed that post-transcriptional and post-translational events play important roles in TTFL18. However, it is not fully understood why the constitutive clock gene expression restores circadian oscillations.

In this study, we investigated the effect of constitutive Bmal1 expression on circadian oscillations. For simplicity, we focused on Bmal1, which is the only clock gene for which a single inactivation leads to loss of circadian rhythmicity19. We established a novel cellular system to study the effects of constitutively-expressed BMAL1 on Bmal1 promoter (PBmal1) activity using the firefly luciferase gene (Fluc) as a reporter. Endogenous Bmal1 was inactivated in human U2OS cells containing the PBmal1::Fluc reporter and an exogenous gene encoding Myc-tagged BMAL1 (MYC-BMAL1) driven by a non-rhythmic, doxycycline (DOX)-inducible promoter was stably introduced. Using these cells, we investigated the effect of constitutively-expressed MYC-BMAL1 on PBmal1 and PPer2 activity and on the accumulation of proteins involved in the ROR/REV/Bmal1 loop. Finally, we performed transient response analysis to obtain transfer function models that recapitulate the behavior of PBmal1 under variable MYC-BMAL1 induction.

Results

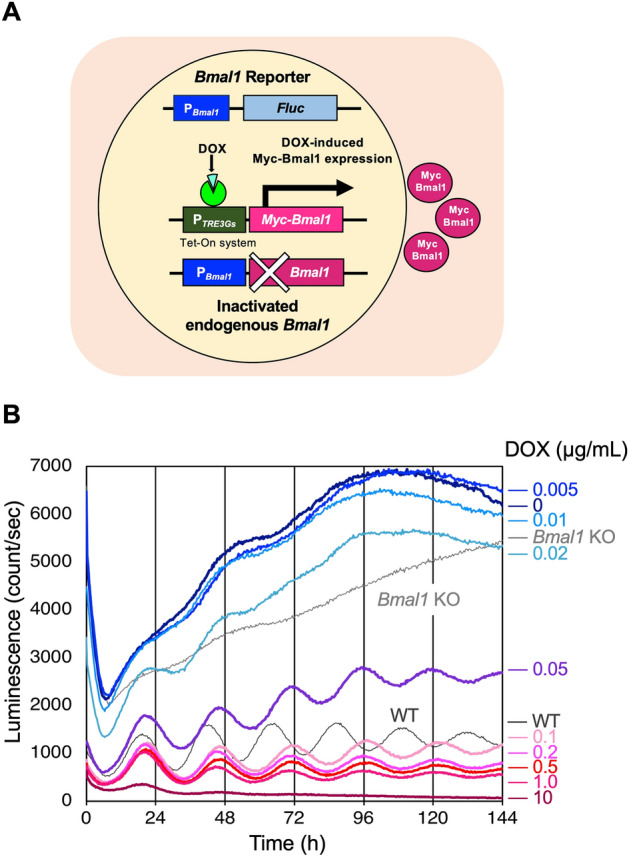

Bmal1 promoter activity at various doxycycline concentrations

We developed novel PBmal1::Fluc reporter cell lines in which endogenous Bmal1 was inactivated by CRISPR-Cas9 and MYC-BMAL1 expression was driven by PTRE3Gs, a DOX-inducible promoter (Fig. 1A). We obtained seven cell lines and measured their luminescence from PBmal1::Fluc. At time 0, 100 nM dexamethasone was added to reset the circadian clock20 and luminescence was measured. The overall intensity of luminescence decreased as the DOX concentration increased, suggesting that BMAL1 protein repressed PBmal1 activity (Fig. S1) either directly or indirectly. Consistently, Yu et al. previously reported that BMAL1 protein represses Bmal1 transcription21. The PBmal1 activity oscillation amplitudes differed among the seven cell lines (Fig. S1). In strains -2 and -51, robust circadian oscillations were restored by 0.1 and 1 µg/mL DOX. Rhythmicity was restored in strains -33 and -59, but not as robustly as in strains -2 and -51. In strains-17, -23, and -27, the PBmal1 rhythmicity was unclear. The robust rhythmicity can be explained, at least in part, by the MYC-BMAL1 accumulation (Fig. S2, see Discussion).

Figure 1.

MYC-BMAL1 expression driven by a DOX-inducible promoter restores rhythmic Bmal1 promoter activity. (A) Schematic diagram of U2OS-PBmal1::Fluc/ΔBmal1/PTRE3Gs::Myc-Bmal1 strains. Endogenous Bmal1 was inactivated by CRISPR-Cas9 and a gene coding MYC-BMAL1 was expressed from the DOX-inducible promoter PTRE3Gs. Bmal1 promoter activity was monitored using the PBmal1::Fluc reporter. We obtained seven strains (-2, -17, -23, -27, -33, -51, and -59). (B) Time course of luminescence measurements from the PBmal1::Fluc reporter in strain-2. Measurements were performed every 20 min and were taken in triplicate. The average values are shown. DOX concentrations are indicated on the right side of the graph.

Strain-2 was selected for further experiments. Luminescence from PBmal1::Fluc was strongly affected by the DOX concentration (Fig. 1B). From 0–0.02 µg/mL DOX, luminescence from PBmal1 fluctuated and oscillation was weak. In the presence of 0.05–0.1 µg/mL DOX, the luminescence gradually increased with clear damped oscillations. From 0.2–1.0 µg/mL DOX, the luminescence showed damped oscillation gradually stabilized at a value specific to each DOX concentration. At 10 µg/mL DOX, the luminescence stabilized after a single overshoot. These results suggest that the amount of MYC-BMAL1 affects the baseline and robustness of PBmal1 activity oscillations. We also observed that the DOX concentration had little effect on the period, which was calculated to be approximately 25 h using chi-square periodogram analysis at any DOX concentration (Table 1 and Fig. S3).

Table 1.

Period of PBmal1::Fluc oscillation calculated for each DOX concentration.

| DOX concentration (µg/mL) | 10 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period (τ) (h) | 25.7 | 25.0 | 25.3 | 25.0 | 24.7 | N.D |

Data from 0 to 144 h shown in Fig. 1B were detrended using 6th-order polynomials and subjected to a chi-square periodogram analysis using Lumicycle analysis software (ActiMetrics; Wilmette, IL, USA).

Simultaneous measurements of Bmal1 and Per2 promoter activity

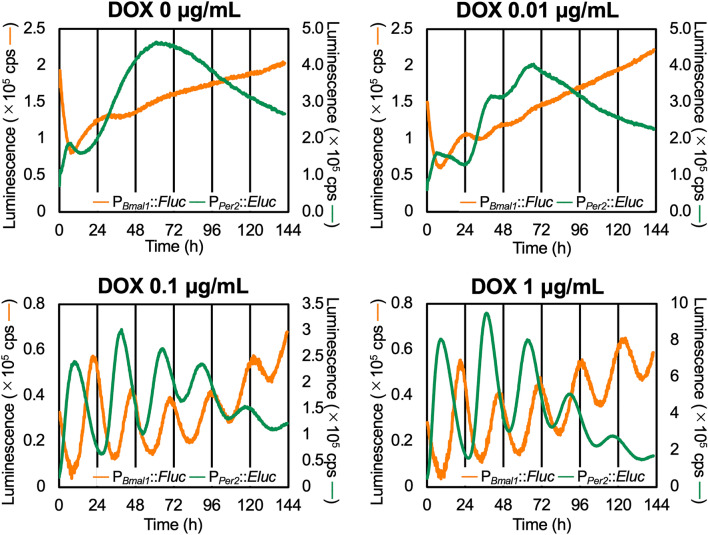

To examine whether constitutive MYC-BMAL1 expression restores circadian oscillation in PPer2 activity, we transiently introduced an Emerald Luc reporter driven by PPer2 (PPer2::Eluc) into strain-2. Dual-wavelength measurements of PBmal1::Fluc and PPer2::Eluc were performed as previously described22 in the presence of various DOX concentrations (Fig. 2). Overall, DOX affected PBmal1 and PPer2 activity in a similar manner. At 0.1 and 1 µg/mL DOX, clear damped PBmal1 and PPer2 oscillations were detected, while at 0 and 0.01 µg/mL DOX, the baseline luminescence from PBmal1 and PPer2 reporters was highly unstable. We could not obtain luminescence data at 10 µg/mL DOX, possibly because simultaneous treatment with the transfection reagent and a high DOX concentration decreased cell viability. The oscillation periods of PPer2 and PBmal1 activities were not significantly affected by the DOX concentration (Table 2 and Fig. S3). Notably, the antiphase relationship between PBmal1 and PPer2 previously observed in wild-type cells12 was recapitulated.

Figure 2.

Constitutively expressed MYC-BMAL1 restores circadian rhythmicity in both PBmal1 and PPer2 activity. U2OS-PBmal1::Fluc/ΔBmal1/PTRE3Gs::Myc-Bmal1 strain-2 cells were transiently transfected with the PPer2::Eluc reporter and were treated with different concentrations of doxycycline (DOX). Dual wavelength luminescence measurements of PBmal1::Fluc and PPer2::Eluc were performed for 6 days. Data presented are the representative curves of 3 independent measurements. The orange lines show luminescence from PBmal1::Fluc and the green lines show luminescence of PPer2::Eluc.

Table 2.

Period of PBmal1::Fluc and PPer2::Eluc oscillation calculated for each DOX concentration.

| DOX concentration (µg/mL) | 1 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period (τ) of PBmal1::Fluc (h) | 24.8 | 24.5 | N.D | N.D |

| Period (τ) of PPer2::Eluc (h) | 26.8 | 26.7 | 26.5 | N.D |

The 0 to 141 h data shown in Fig. 2 were detrended by 6th-order polynomials and subjected to chi-square periodogram analysis using Lumicycle analysis software (ActiMetrics; Wilmette, IL, USA).

Measurement of the levels of translational and transcriptional products of exogenous Bmal1

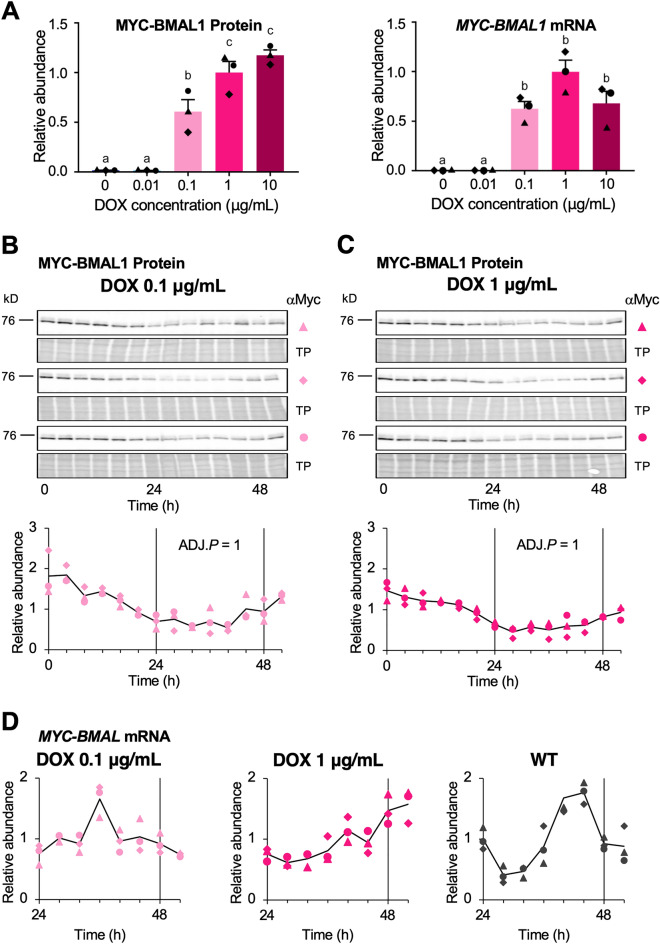

Next, we measured MYC-BMAL1 protein and mRNA levels in the presence of DOX. We collected samples of total protein and total RNA from strain-2 every 4 h after stimulation with 100 nM dexamethasone and subjected them to immunoblot analysis and quantitative RT-PCR. To examine DOX-induced changes in the overall MYC-BMAL1 levels, we analyzed an equal-volume mixture of samples from 0 to 52 h after stimulation. The total amount of MYC-BMAL1 increased remarkably between 0.01 and 0.1 µg/mL of DOX (Fig. 3A, left panel), the same concentration range at which baseline stability and robustness of the oscillation markedly increased (Fig. 1B). The average MYC-BMAL1 mRNA levels from 24 to 52 h showed the same tendency (Fig. 3A, right panel). We then assessed MYC-BMAL1 accumulation in the presence of 0.1 and 1 µg/mL DOX over time (Fig. 3B,C). Unlike the luminescence traces from PBmal1::Fluc, no significant rhythmicity in the circadian range (between 20 and 28 h) was observed for MYC-BMAL1 accumulation (JTK cycle test, adjusted (ADJ.) P = 1)23. We also measured the changes in mRNA levels from 24–52 h after DOX addition using quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 3D). The endogenous Bmal1 transcript from wild-type U2OS cells showed clear daily fluctuations, with its peak and trough coinciding with those of PBmal1 activity (Fig. 1B, WT). However, no such relationship was observed for MYC-BMAL1 mRNA in the presence of 0.1 and 1 µg/mL DOX.

Figure 3.

MYC-BMAL1 protein and mRNA accumulation do not show significant circadian rhythmicity. Total protein and RNA samples were collected from U2OS-PBmal1::Fluc/ΔBmal1/PTRE3Gs::Myc-Bmal1 strain-2 cell cultures every 4 h from 0 to 52 h (for total protein) or 24 to 52 h (for total RNA) after adding 100 nM dexamethasone. (A) Graphs showing relative MYC-BMAL1 protein (left panel) and mRNA accumulation (right panel) after treatment with different concentrations of doxycycline (DOX). For protein accumulation, equal amounts of the samples collected for each DOX concentration were mixed and subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-Myc antibody. For mRNA accumulation, the average of all the time points for each DOX concentration was calculated. Results were normalized using the average values at 1 µg/mL DOX. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. N = 3 samples/group, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Different characters (a, b, c) indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). (B,C) Time course of MYC-BMAL1 protein expression after addition of dexamethasone (time 0) in the presence of 0.1 µg/mL (B) and 1 µg/mL DOX (C). Protein samples were collected and subjected to immunoblot analysis in three independent experiments (upper panels). Markers (filled traingle, filled diamond, and filled circle) indicate MYC-BMAL1 bands in three biological replicates, and TP indicates total protein stains. Graphs (lower panels) show the quantification of MYC-BMAL1 amount by densitometry. The intensity of each band was normalized by total protein, and values were normalized using the average of all time points in each series. Black lines indicate the average values of the three biological replicates. No significant rhythmicity in the circadian range (between 20 to 28 h) was detected in the presence of 0.1 and 1 µg/mL DOX (JTK cycle test, ADJ.P = 1). (D) Time course of MYC-BMAL1 mRNA expression after addition of dexamethasone (time 0). Total RNA was extracted from strain-2 cells in the presence of 0.1 and 1 µg/mL DOX and from wild-type U2OS cells. Samples were analyzed by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR. Relative expression was calculated using Pfaffl’s method36 with GAPDH as an internal control. Markers (filled triangle, filled diamond, and filled circle) indicate three biological replicates. Values were normalized using the average of all time points in each series. Black lines indicate the average values of the three biological replicates.

We also compared the average levels of DOX-induced MYC-BMAL1 protein in pooled strain-2 samples collected from 0–52 h at 4-h intervals with that of endogenous BMAL1 expressed in wild-type U2OS cells (Fig. S4). The amount of endogenous BMAL1 was about 25% of that of MYC-BMAL1 induced by 1 µg/mL DOX, indicating that higher BMAL1 expression is required when it is driven by a non-rhythmic promoter, suggesting the biological importance of rhythmic promoters.

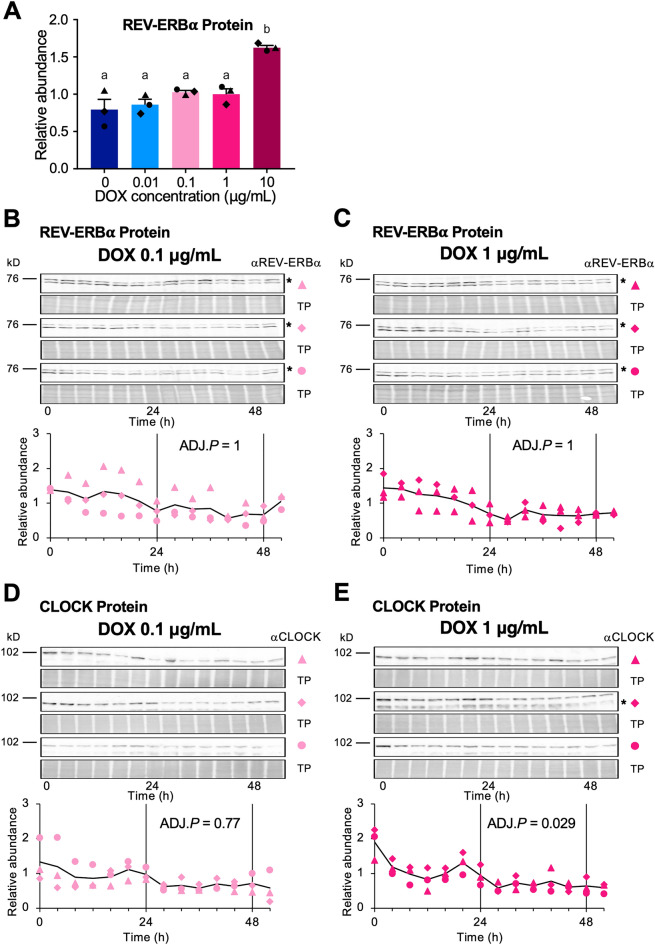

Accumulation of proteins involved in the ROR/REV/Bmal1 loop

In the current model of the mammalian circadian clock, BMAL1, CLOCK, REV-ERBs, and RORs constitute the ROR/REV/Bmal1 loop10–14. To examine how constitutive MYC-BMAL1 expression affects CLOCK and REV-ERBα accumulation, we performed immunoblot analysis using protein samples collected in the presence of different DOX concentrations over time. The overall protein levels of REV-ERBα measured in pooled samples collected 0–52 h after stimulation showed an increasing trend at higher DOX concentrations (Fig. 4A). However, in contrast to MYC-BMAL1 expression (Fig. 3A), no significant change was observed between 0.01 and 0.1 µg/mL DOX. We also examined changes in the REV-ERBα (Fig. 4B,C) and CLOCK (Fig. 4D,E) in the presence of 0.1 and 1 µg/mL DOX over time. No significant rhythmicity in the circadian range was observed, except for CLOCK at 1 µg/mL DOX using the JTK cycle test (ADJ.P = 0.029 for CLOCK at 1 µg/mL, 0.77 for CLOCK at 0.1 µg/mL, and ADJ.P = 1 for REV-ERBα). The CLOCK oscillation amplitude was 0.23 at 1 µg/mL DOX using the JTK cycle test, suggesting that the rhythmicity of CLOCK accumulation, if any, was very weak.

Figure 4.

Accumulation of REV-ERBα and CLOCK does not show obvious circadian rhythmicity. (A) A mixture of equal amounts of protein samples collected from U2OS-PBmal1::Fluc/ΔBmal1/PTRE3Gs::Myc-Bmal1 strain-2 cell cultures from 0 to 52 h after the addition of 100 nM dexamethasone in the presence of each doxycycline (DOX) concentration was subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-REV-ERBα antibodies. The amount of protein was calculated by the density of each band versus total protein and were normalized using the value from the 1 µg/mL DOX group. The results are shown as mean ± SEM (N = 3). Different characters (a, b) indicate significant differences (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, P < 0.05). (B–E) Time course of protein expression in the presence of 0.1 µg/mL (B,D) and 1 µg/mL DOX (C,E). Images showing the protein bands detected for REV-ERBα (B–C), CLOCK (D–E), and total protein (TP) stains (upper panels). Asterisks in (B,C,E) indicate nonspecific bands. Markers (filled traingle, filled diamond, and filled circle) indicate three biological replicates. For REV-ERBα detection, the same blots used for MYC-BMAL1 detection were reprobed. The protein amount was quantified using densitometry (lower panel). The relative expression of REV-ERBα (B–C) and CLOCK (D–E) protein was calculated by the density of each band vs. total protein and were normalized against the intensity of pooled 0 to 52 h samples. Black lines indicate the average values of three biological replicates. No significant rhythmicity was detected for REV-ERBα at 0.1 and 1 µg/mL DOX (JTK cycle test, ADJ.P = 1) or CLOCK at 0.1 µg/mL DOX (JTK cycle test, ADJ.P = 0.77). CLOCK at 1.0 µg/mL DOX exhibited significant rhythmicity (JTK cycle test, ADJ.P = 0.029) with low amplitude (JTK cycle test, AMP = 0.23).

Transient response analysis of PBmal1 activity

To elucidate the mechanism underlying the generation of PBmal1 circadian oscillations under constitutive MYC-BMAL1 expression, we performed transient response analysis. This method identifies a transfer function (i.e., an input–output relationship of a linear system) from the observed data to reveal the underlying system dynamics24,25. In our framework, dexamethasone administration was considered the input to stimulate PBmal1 activity. The transfer functions of the stimulated transient PBmal1 activity were estimated using the system identification toolbox pre-installed in MATLAB (version R2019b; MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). The administration of 100 nM dexamethasone at time 0 was approximated by a unit step input to the system, which can be expressed by the following unit step function:

| 1 |

Denoting and as the Laplace transforms of the input and output signals, respectively, the transfer function G(s) is represented as:

| 2 |

As shown in Fig. 5, PBmal1 activity in the presence of 1 µg/mL DOX was approximated by the following transfer function with two poles and no zeros:

| 3 |

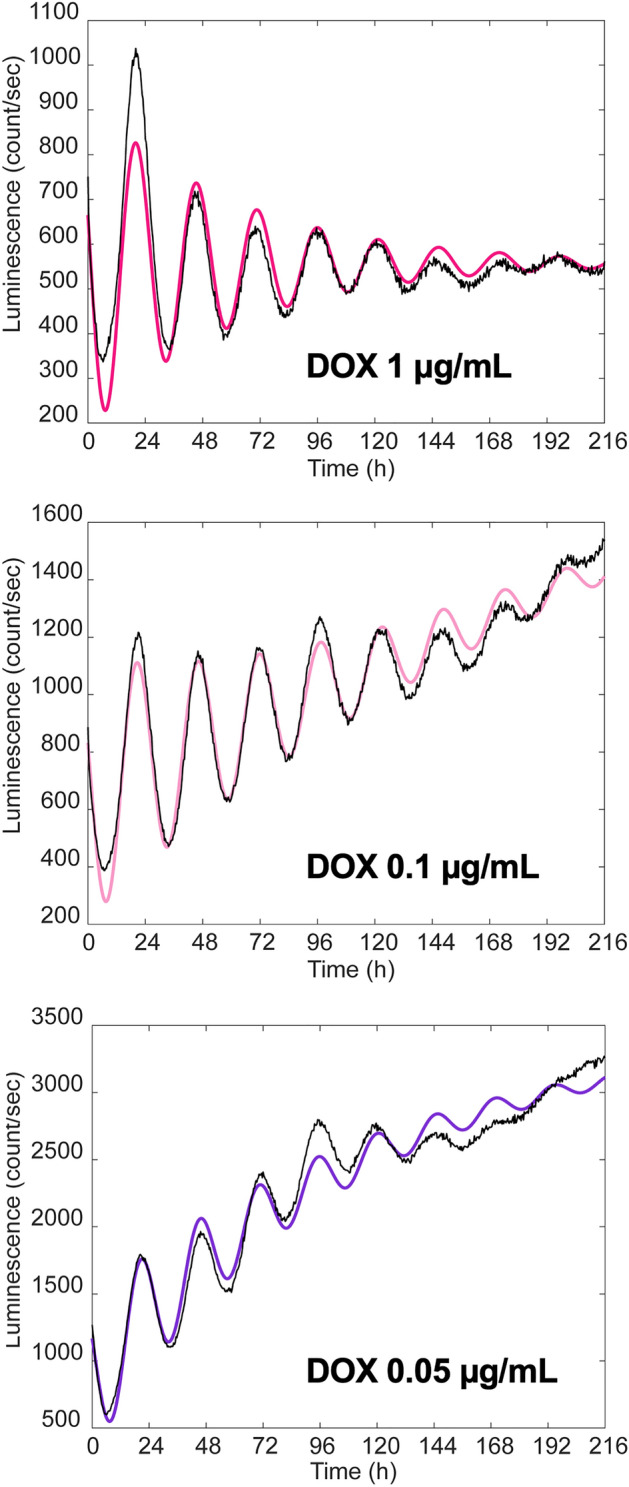

Figure 5.

Transfer functions reproducing the behavior of PBmal1 activity obtained by transient response analysis. Luminescence data of PBmal1 activity in the presence of 0.05, 0.1 and 1 µg/mL doxycycline (DOX) shown in Fig. 1B were subjected to transient response analysis. Experimental values of luminescence intensity are shown in black and simulated data are shown in red for 1 µg/mL DOX (upper panel), pink for 0.1 µg/mL DOX (middle panel), and purple for 0.05 µg/mL DOX (bottom panel).

The coefficients were estimated as , , and . This formula can be rewritten as the following second-order system representing a damped oscillator:

| 4 |

where ωn, ζ, and K are the natural angular frequency, damping coefficient, and gain, respectively. Using ωn and ζ, the period τ of the damped oscillator is determined as:

| 5 |

On the other hand, PBmal1 activity in the presence of 0.05 and 0.1 µg/mL DOX were approximated by the following third-order transfer function with three poles and no zeros (Fig. 5):

| 6 |

The coefficients were estimated as , , , for 0.05 µg/mL DOX; and , , , for 0.1 µg/mL DOX. This third-order transfer function can be decomposed into first-order and second-order systems, as follows:

| 7 |

In a first-order system (i.e., ), the time constant characterizes the response time required for the baseline luminescence signal to rise exponentially to its steady state. The parameter values calculated for each DOX concentration are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parameters of oscillation calculated for each DOX concentration.

| DOX concentration (µg/mL) | 1 | 0.1 | 0.05 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural angular velocity (ωn) (h−1) | 0.2484 | 0.2460 | 0.2532 |

| Damping coefficient (ζ) (h−1) | 0.06469 | 0.03668 | 0.04667 |

| *Period (τ) (h) | 25.4 | 25.6 | 24.8 |

| Time constant (Ts) (h−1) | – | 350.2 | 118.4 |

| Gain (K) | 557.8 | 1249 | 3504 |

*Calculated by substituting the ωn and ζ values into Eq. (5).

This analysis indicated that in the presence of 0.01 µg/mL DOX, a higher-order transfer function was required to describe the behavior of PBmal1 activity, which is difficult to interpret using a combination of basic elements (Fig. S5). It is possible that the baseline PBmal1 activity became uncontrollable when the Myc-BMAL1 concentration was too low.

Discussion

TTFL is the model of choice for explaining circadian oscillations in clock gene transcription1,2. However, this model cannot fully explain why constitutive clock gene expression restores circadian oscillations. In this study, we performed quantitative experiments using a newly established PBmal1::Fluc reporter cell line in which endogenous Bmal1 is inactivated by CRISPR-Cas9 and exogenous Bmal1 is expressed under a DOX-inducible promoter. This in vitro system allowed us to reproduce the restored circadian oscillations under constitutive Bmal1 expression, as previously reported15.

We established seven cell lines, strains-2, -17, -23, -27, -33, -51, and -59 and measured luminescence from the PBmal1::Fluc reporter (Fig. S1) induced by DOX treatment two days before synchronization with dexamethasone. Among these, strains-2, and -51 restored the robust circadian oscillations in the presence of 0.1 and 1 µg/mL DOX. Strains-59 and -33 also restored rhythmicity, but to a lesser extent. Strains-17, 23, and 27 exhibited no obvious oscillations. These differences can be explained, at least partially, by the amount of induced MYC-BMAL1. We compared MYC-BMAL1 levels in the seven strains treated with 1 or 0.01 µg/mL DOX for 2 days (Fig. S2). In the presence of 1 µg/mL DOX (Fig. S2A), MYC-BMAL1 levels were significantly higher in strains-23 and -33 and lower in strain-27 and 33 than in strain-2. Strains -51 and -59 showed no significant differences compared to strain-2. In strain-23, MYC-BMAL1 was three-to four-fold higher than in strain-2, while in strain-33, the level was comparable to that in strain-51. These results indicate that an appropriate induction level of MYC-BMAL1 is required to restore rhythmicity. In strain-51, weak rhythmicity was observed, even in the presence of 0.01 µg/mL DOX, which may reflect the slightly higher MYC-BMAL1 accumulation compared to strain-2 at this concentration (Fig. S2B).

Our results indicate that exogenous BMAL1 expressed by a non-rhythmic DOX-inducible promoter can restore circadian rhythmicity in Bmal1-disrupted cells. PBmal1 and PPer2 activity exhibited robust circadian rhythms in the presence of 0.1 and 1 µg/mL DOX, whereas the accumulation of MYC-BMAL1 and REV-ERBα at 0.1 and 1 µg/mL DOX, and CLOCK at 0.1 µg/mL DOX did not show significant circadian rhythmicity. The rhythmicity of CLOCK accumulation at 1 µg/mL DOX was significant but quite weak, with an amplitude of 0.23, as estimated by JTK cycle tests. We expect that this CLOCK rhythmicity is not the cause of the PBmal1 oscillation for the following reasons: (i) to our knowledge, no reports have been published demonstrating that CLOCK regulates Bmal1 transcription by directly binding to the regulatory region of Bmal1; (ii) the translational products of REV-ERBs and RORs, whose expression is regulated by the CLOCK-BMAL1 heterodimer, regulate Bmal1 transcription by directly binding to the regulatory region of Bmal1. However, as shown in Fig. 4, the REV-ERBα did not show significant oscillations at 0.1 and 1 µg/mL DOX while it exhibited clear circadian oscillation in WT U2OS (Fig. S6). Therefore, robust circadian oscillations at the promoter level are unlikely to be driven by oscillations at the protein level, although this possibility cannot be completely excluded.

CLOCK, BMAL1, and REV-ERBα undergo circadian changes in phosphorylation state26,27. In particular, CLOCK and BMAL1 phosphorylation plays essential roles in circadian oscillations by regulating protein–protein interactions, nuclear localization, and transcriptional activity26,28,29. Phosphorylated proteins are often detected by electrophoretic mobility shifts during SDS-PAGE30. However, we did not detect a remarkable mobility shift of the CLOCK, BMAL1, and REV-ERBα bands over time (Figs. 3 and 4). Therefore, it is improbable that rhythmic PBmal1 and PPer2 activity is driven by circadian phosphorylation of these proteins. However, we cannot completely rule out this possibility because a small fraction of these proteins, such as the nuclear BMAL1-CLOCK heterodimer, may exhibit circadian oscillations28.

Because the components of the core loop were not genetically manipulated in our Bmal1-inducible cell line, it is possible that the oscillation in PBmal1 activity is driven by the intact core loop. However, this does not seem to be the case because the amplitude of the PBmal1 and PPer2 oscillations was simultaneously restored in accordance with the DOX concentration (Fig. 2). These results suggest that induced BMAL1 affects PBmal1 and PPer2 activity equally and that no hierarchical relationship exists between PBmal1 and PPer2. Furthermore, PBmal1 oscillations were almost antiphase with PPer2 activity, as in wild-type cells, even though functional Bmal1 was not driven by an endogenous promoter containing RORE. It is difficult to explain the behavior of PBmal1 and PPer2 observed in our experiment using the current TTFL model.

The oscillation periods of PBmal1 and PPer2 were calculated to be approximately 25 and 27 h, respectively. A similar difference was reported in ex vivo suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) culture31, suggesting that the core loop and ROR/REV/Bmal1 loop oscillate independently. In our experimental system, PBmal1 and PPer2 activity might be governed by independent oscillators.

In the past two decades, numerous mathematical models describing circadian systems have been proposed32. In these models, TTFL behaviors, such as the activation and repression of clock gene transcription by clock gene products, are expressed using a set of differential equations containing experimentally determined parameters. Mirsky et al. mimicked constitutive Bmal1 expression by setting Bmal1 mRNA synthesis to a fixed rate33. This model predicted that the levels of transcriptional and translational products of Per, Cry, Clock, RORc, and Rev-erbα, and the translational product of Bmal1, exhibited clear circadian oscillations even under constant Bmal1 mRNA levels. In contrast, we did not observe clear rhythmicity in BMAL1, CLOCK, or REV-ERBα protein levels under constitutive Bmal1 expression. Relogio et al. demonstrated that the amplitude of REV-ERB and ROR oscillations and their phase relationship are crucial for generating Bmal1 transcriptional oscillations in the correct phase relative to other clock genes34. However, our results showed that although REV-ERBα levels were almost constant, PBmal1 activity oscillated in the correct phase relative to PPer2. Therefore, it is difficult to interpret our results using these mathematical models.

To gain insight into the mechanisms driving the circadian oscillation of PBmal1 and PPer2 promoter activity, we performed transient response analysis24,25. At 1 µg/mL DOX, the experimental data were well approximated by a second-order system that represented a damped oscillation. When the DOX concentration was lowered to 0.1 and 0.05 µg/mL, the luminescence from the PBma1::Fluc was approximated by a third-order system that can be interpreted as a damped oscillation forced through a first-order system. For all three cases, the damping coefficient (ζ) was quite small (i.e., less than 0.07), implying that the damping effect was rather weak. The oscillation periods (τ) were all in a similar range between 24.8 and 25.6 h (Table 3). These results suggest that the amount of BMAL1 does not markedly affect the oscillatory parameters, but has a major impact on the baseline PBmal1 activity. Our analysis presents the possibility that a weakly damped oscillator system, whose molecular mechanism is yet to be clarified but is almost independent of BMAL1, underlies the circadian clock mechanism. Our results also suggest that this oscillator regulates PBma1 and PPer2 activities in parallel.

Based on our results, it is possible that in our experimental system, the roles of Bmal1 in circadian oscillations are different from those assumed in the TTFL models. Further studies are required to determine whether the function of Bmal1 described in this study is specific to our experimental system or whether it is true for the mammalian circadian system.

Materials and methods

Disruption of BMAL1 in U2OS-PBmal1::Fluc cells

Human U2OS cells (HTB-96; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) containing the PBmal1::Fluc reporter (U2OS-PBmal1::Fluc)35 were plated in 35 mm culture dishes (Nunc EasYDish; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at a density of 2 × 105 cells/dish in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (D6429; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. The cells were cultured at 37 °C with 10% CO2 for approximately 24 h.

U2OS-PBmal1::Fluc was transfected with 1.4 µg of human BMAL1 CRISPR/Cas9 KO plasmid (sc-400808; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) consisting of a pool of three plasmids, each encoding the Cas9 nuclease, a target-specific 20 nt guide RNA (sgA, sgB, or sgC), and 1.4 µg of human BMAL1 HDR plasmid (sc-400808-HDR; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) using Xfect transfection reagent (Takara Bio USA, San Jose, CA, USA). Puromycin-resistant clones were selected using 1 µg/mL puromycin. Bmal1 knockout was confirmed by immunoblot analysis using anti-BMAL1 antibody (B-1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) and genomic PCR followed by Sanger sequencing. The following primers were used for genomic PCR and Sanger sequencing: C_fwd, 5' AGATCATCCAATGGCAGAC 3'; C_rev:5' GAGATGACACCCATAGACTTA 3'; B_fwd:5' AAGAAGCTCTTCTGTATGTC 3''; B_rev:5' AATAAGGTCCAAGCTTACCT 3'; A_fwd:5' AAGAGCGATGTCGTTGGAG 3''; A_rev:5' TGCATGGTACAAGTCCTGAAGC 3'. The results of the genomic PCR and Sanger sequencing are summarized in Supplementary Fig. S7. A Bmal1 knockout clone, named U2OS-PBmal1::Fluc/ΔBmal1, was used to establish Myc-tagged BMAL1 (MYC-BMAL1) inducible clones.

Construction of doxycycline-inducible expression plasmid of Myc-BMAL1

The human BMAL1 open reading frame (ORF) was amplified by PCR using KOD-plus-neo (Toyobo Biotechnology, Osaka, Japan) from the Kazusa Flexi ORF clone FXC03462 (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and the following primers: Bmal1ORF_fwd, 5' CCGGAATTCATGGCAGACCAGAGAATGGACATTTCT 3'; Bmal1ORF_rev, 5' CGCGGATCCTCACAGCGGCCATGGCAAGTCACTAAAGTC 3'. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and cloned into the EcoRI-BamHI site of pTetOne (Takara Bio USA, San Jose, CA, USA). The Myc-tag was introduced into the resultant plasmid by inverse PCR using KOD-Plus mutagenesis kit (Toyobo Biotechnology, Osaka, Japan). The following primers were used for inverse PCR: Myc-Bmal1_fwd, 5' ACCATGGAGCAGAAGCTGATCTCAGAGGAGGACCTGATGGCAGACCAGAGAATGGACATTTCT 3'; Myc-Bmal1_rev, 5' GAATTCTTTACGAGGGTAGGAAGTGGT 3'. The resulting plasmid was named pTetOne-MycBmal1.

Establishment of MYC-BMAL1 inducible cell lines

U2OS-PBmal1::Fluc/ΔBmal1 cells were transfected with 5 µg pTetOne-MycBmal1 plasmid and 0.25 µg linear hygromycin marker (Takara Bio USA, San Jose, CA, USA) using Xfect transfection reagent (Takara Bio USA, San Jose, CA, USA). Hygromycin B (300 µg/mL) was added to the cell culture to select positive clones. MYC-BMAL1 protein expression in the isolated clones was evaluated by immunoblot analysis using an anti-Myc-tag mAb (My3, Medical & Biological Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan) in the presence of 1 µg/mL DOX (Takara Bio USA, San Jose, CA, USA). We obtained seven cell lines, which we named U2OS-PBmal1::Fluc/ΔBmal1/ PTRE3Gs::Myc-Bmal1 strains-2, -17, -23, -27, -33, -51, and -59.

Luminescence measurements

U2OS-PBmal1::Fluc/ΔBmal1/ PTRE3Gs::Myc-Bmal1 cells were plated at a density of 8 × 103 cells/well in 96 well white, clear-bottom culture plates and were cultured for 48 h at 37 °C in 10% CO2 to reach confluence. The cells were treated with DOX (0–10 µg/mL) and incubated for another 48 h. The medium was then changed to medium for luminescence measurement35 supplemented with the same DOX concentration. Luminescence was measured every 20 min for approximately 1 week using a plate reader (Enspire; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). An integration time of 1 s was employed for each measurement.

For dual-reporter measurements, U2OS-PBmal1::Fluc/ΔBmal1/PTRE3Gs::Myc-Bmal1 strain-2 cells were plated in 35 mm culture dishes (Nunc EasYDish; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at a density of 2 × 105 cells/dish in the presence of 0, 0.01, 0.1, and 1 µg/mL DOX. The next day, cells were transiently transfected with 2.5 µg pPPer2::Eluc plasmid containing a 423-bp fragment of the mPer2 promoter region36 inserted at the BglII-EcoRI site of the pEluc(PEST)-test (Toyobo Biotechnology, Osaka, Japan) using Xfect transfection reagent (Takara Bio USA, San Jose, CA). Then, the cells were incubated for another 24 h. The medium was changed to luminescence measurement medium supplemented with DOX at the same concentration. Luminescence from PBmal1::Fluc and PPer2::Eluc reporters was measured simultaneously using a Kronos-Dio instrument (ATTO, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 620 nm long pass filter for 6 days according to the method described by Ono et al.22.

Immunoblot analysis of circadian clock proteins

U2OS-PBmal1::Fluc/ΔBmal1/ PTRE3Gs::Myc-Bmal1 strain-2 cells were plated at a density of 2 × 105 cells/dish in 35 mm dishes and cultured at 37 °C with 10% CO2. When cells reached confluence, 0 to 10 µg/mL DOX was added and the cells were cultured for another 48 h. The medium was changed to DMEM supplemented with 2% B-27 (Gibco), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, 100 nM dexamethasone, and DOX at the same concentration. The cells were lysed with 1 × SDS sample buffer 0–52 h after adding dexamethasone. Samples were sonicated using a Bioruptor UCW 310 (Cosmo Bio, Tokyo, Japan) for 25 cycles of 30 s sonication at 310 W, followed by 30 s of rest in ice water. The samples were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove debris and denatured at 95 °C for 5 min. Protein concentration was measured using Pierce 660 nm Protein Assay Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE on 7.5% gels (E-R7.5L, ATTO, Tokyo, Japan) loaded at 20 µg protein/lane. The bands were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes using an iBlot 2 Dry Blotting system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The membranes were stained with Ez Stain Aqua Mem solution (ATTO, Tokyo, Japan) to measure the total protein levels. Images were captured using a LuminoGraph II EM instrument (ATTO, Tokyo, Japan) in bright-field mode. The membranes were destained and blocked overnight with 5% skim milk dissolved in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.2% Tween 20 (TBS-T) at 4 °C. The membranes were incubated with primary antibody diluted in 5% skim milk in TBS-T for 1.5 h at room temperature and washed three times with TBS-T for 10 min. The membranes were incubated with secondary antibody for 1.5 h at room temperature and were washed as described above. For luminescence detection, the membranes were treated with ECL prime reagent (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA). Signals were captured using a LuminoGraph II EM instrument (ATTO, Tokyo, Japan). Quantification of band intensity was performed using ImageJ software (NIH, USA). The background signal was measured in a signal-free area of the membrane and subtracted from the intensity of each band, which was then normalized to the total protein.

The antibodies used and their dilutions were as follows: anti-Myc-tag mAb (My3; MBL, Tokyo, Japan), 1:200; anti-NR1D1 pAb (Rev-Erbα) (PM092; MBL, Tokyo, Japan), 1:200; anti-CLOCK (18,094–1-AP; Proteintech, Chicago, IL, USA), 1:500; anti-ARNTL (BMAL1) (14,268–1-AP; Proteintech, Chicago, IL, USA), 1:3000; HRP-linked anti-mouse IgG (NA931; Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA), 1:1000; and HRP-linked anti-rabbit IgG (NA934; Cytiva), 1:1000.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR)

Samples were collected from 24 to 52 h after the addition of dexamethasone and were prepared as described above. Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy-plus Micro kit (QIAGEN, Venlo, Netherlands). The RNA concentration was measured using a spectrophotometer. Reverse transcription was performed using ReverTra Ace (Toyobo Biotechnology, Osaka, Japan) and 3 µg total RNA. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using QuantStudio 3 (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) in 20 µL reactions containing 10 µL 2 × TaqMan gene expression master mix (Applied Biosystems), 4 µL reverse transcription reaction mixture, and 1 µL 20 × TaqMan gene expression assay (HS01587195_m1 for BMAL1 and HS02786624_g1 for GAPDH, Applied Biosystems). Relative expression was calculated using Pfaffl’s method37, with GAPDH used as an internal control.

Statistical analysis

Significant differences between more than two groups was evaluated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test using GraphPad Prism version 7.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Rhythmicity was determined by the JTK cycle test23. All P-values were from two-tailed tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Isao Tokuda for critical reading of the manuscript; Takao Kondo, Hirokazu Fukuda, Tetsuya Inagaki, Shuji Akiyama, Tomoki P. Terada, Kumiko Ito-Miwa, and Tomoya Ohkawa for helpful discussions and advice; and Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI, Grant Number JP15H04349 (T.N.-O.), JP19H03178 (T.N.-O.), JP21H02526 (D.O.), JP19H05643 (T.Y. and T.N.-O.), and the MEXT Japanese Government Scholarship (P.A.).

Author contributions

P.A., T.N.-O. designed the study; P.A., D.O., R.H., and T.N.-O performed the experiments; R.H., Y.F., and T.Y. contributed new reagents/analytical tools; P.A., D.O., and T.N.-O. analyzed the data, and P.A. and T.N.-O. wrote the paper.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-24188-4.

References

- 1.Takahashi JS. Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017;18:164–179. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunlap JC. Molecular bases for circadian clocks. Cell. 1999;96:271–290. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80566-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Partch CL, Green CB, Takahashi JS. Molecular architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gekakis N, et al. Role of the CLOCK protein in the mammalian circadian mechanism. Science. 1998;280:1564–1569. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hogenesch, J. B., Gu, Y. Z., Jain, S. & Bradfield, C. A. The basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS orphan MOP3 forms transcriptionally active complexes with circadian and hypoxia factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA95, 5474–5479 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Kume K, et al. mCRY1 and mCRY2 are essential components of the negative limb of the circadian clock feedback loop. Cell. 1999;98:193–205. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffin EA, Jr, Staknis D, Weitz CJ. Light-independent role of CRY1 and CRY2 in the mammalian circadian clock. Science. 1999;286:768–771. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature. 2002;418:935–941. doi: 10.1038/nature00965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shearman LP, et al. Interacting molecular loops in the mammalian circadian clock. Science. 2000;288:1013–1019. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5468.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sato TK, et al. A functional genomics strategy reveals Rora as a component of the mammalian circadian clock. Neuron. 2004;43:527–537. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preitner N, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBα controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell. 2002;110:251–260. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00825-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ueda HR, et al. System-level identification of transcriptional circuits underlying mammalian circadian clocks. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:187–192. doi: 10.1038/ng1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho H, et al. Regulation of circadian behaviour and metabolism by REV-ERB-α and REV-ERB-β. Nature. 2012;485:123–127. doi: 10.1038/nature11048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillaumond F, Dardente H, Giguère V, Cermakian N. Differential control of Bmal1 circadian transcription by REV-ERB and ROR nuclear receptors. J. Biol. Rhythms. 2005;20:391–403. doi: 10.1177/0748730405277232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu AC, et al. Redundant function of REV-ERBα and β and non-essential role for Bmal1 cycling in transcriptional regulation of intracellular circadian rhythms. PLOS Genet. 2008;4:e1000023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan Y, Hida A, Anderson DA, Izumo M, Johnson CH. Cycling of cryptochrome proteins is not necessary for circadian-clock function in mammalian fibroblasts. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Alessandro M, et al. A tunable artificial circadian clock in clock-defective mice. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8587. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crosby, P. & Partch, C. L. New insights into non-transcriptional regulation of mammalian core clock proteins. J. Cell Sci.133, jcs241174 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Bunger MK, et al. Mop3 is an essential component of the master circadian pacemaker in mammals. Cell. 2000;103:1009–1017. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balsalobre A, et al. Resetting of circadian time in peripheral tissues by glucocorticoid signaling. Science. 2000;289:2344–2347. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu W, Nomura M, Ikeda M. Interactivating feedback loops within the mammalian clock: BMAL1 is negatively autoregulated and upregulated by CRY1, CRY2, and PER2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;290:933–941. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ono D, Honma S, Honma K. Differential roles of AVP and VIP signaling in the postnatal changes of neural networks for coherent circadian rhythms in the SCN. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:e1600960. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes ME, Hogenesch JB, Kornacker K. JTK_CYCLE: an efficient nonparametric algorithm for detecting rhythmic components in genome-scale data sets. J. Biol. Rhythms. 2010;25:372–380. doi: 10.1177/0748730410379711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuo, B. C. & Golnaraghi, M. F. Automatic Control. Systems (Vol. 9) (Prentice-Hall, 1995).

- 25.Ogata, K. Modern Control. Engineering (Vol. 5) (Prentice-Hall, 2010).

- 26.Lee C, Etchegaray JP, Cagampang FR, Loudon AS, Reppert SM. Posttranslational mechanisms regulate the mammalian circadian clock. Cell. 2001;107:855–867. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00610-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robles MS, Humphrey SJ, Mann M. Phosphorylation is a central mechanism for circadian control of metabolism and physiology. Cell Metab. 2017;25:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshitane H, et al. Roles of CLOCK phosphorylation in suppression of E-box-dependent transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:3675–3686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01864-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamaru T, et al. CK2alpha phosphorylates BMAL1 to regulate the mammalian clock. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:446–448. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee CR, Park YH, Min H, Kim YR, Seok YJ. Determination of protein phosphorylation by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J. Microbiol. 2019;57:93–100. doi: 10.1007/s12275-019-9021-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ono, D. et al. Dissociation of Per1 and Bmal1 circadian rhythms in the suprachiasmatic nucleus in parallel with behavioral outputs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA114, E3699–E3708 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Asgari-Targhi A, Klerman EB. Mathematical modeling of circadian rhythms. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2019;11:e1439. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mirsky, H. P., Liu, A. C., Welsh, D. K., Kay, S. A. & Doyle, F. J. 3rd. A model of the cell-autonomous mammalian circadian clock. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA106, 11107–11112 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Relógio A, et al. Tuning the mammalian circadian clock: robust synergy of two loops. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2011;7:e1002309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oshima T, et al. C-H activation generates period-shortening molecules that target cryptochrome in the mammalian circadian clock. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015;54:7193–7197. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiyohara, Y. B. et al. The BMAL1 C terminus regulates the circadian transcription feedback loop. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA103, 10074–10079 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).