Abstract

Objective

To assess whether (household) food insecurity, access to a regular medical doctor, and sense of community belonging mediate the relationship between mood and/or anxiety disorders and self-rated general health.

Methods

We used six annual cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey, including Canadian adults aged 18–59 years, between 2011 and 2016. Mediation models, adjusted for key determinants of health, were based on a series of weighted logistic regression models. The Sobel products of coefficients approach was used to estimate the indirect effect, and bootstrapping to estimate uncertainty.

Results

The annual (weighted) prevalence of mood and/or anxiety disorders increased from 11.3% (2011) to 13.2% (2016). Across the 6 years, 23.9–27.7% of individuals with mood and/or anxiety disorders reported fair/poor self-rated health as compared with 4.9–6.5% of those without mood and/or anxiety disorders (p<0.001). Similarly, the 7.2–8.9% of the population reporting fair/poor self-rated health were disproportionately represented among individuals reporting food insecurity (21.1–26.2%, p<0.001) and a weak sense of community belonging (10.0–12.2%, p<0.001). A significantly lower prevalence of poor self-rated health was observed among respondents reporting having access to a regular medical doctor in 2012, 2015, and 2016. In 2016, sense of community belonging and food insecurity significantly mediated the effect of mood and/or anxiety disorders on self-rated general health. Access to a regular medical doctor did not mediate this relationship.

Conclusion

Efficient policies that address food insecurity and sense of community belonging are needed to decrease the mental health burden and improve health satisfaction of Canadians.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.17269/s41997-022-00658-0.

Keywords: Sense of community belonging, Community connectedness, Household food insecurity, Healthcare access, Mental health, Mood disorder, Anxiety, Self-rated general health

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer si l’insécurité alimentaire (du ménage), l’accès à un médecin traitant et le sentiment d’appartenance à la communauté modèrent le lien entre les troubles anxieux et/ou de l’humeur et la santé générale autoévaluée.

Méthode

Nous avons utilisé six cycles annuels (2011 à 2016) de l’Enquête sur la santé dans les collectivités canadiennes incluant des Canadiens adultes de 18 à 59 ans. Nos modèles de modération, ajustés selon les principaux déterminants de la santé, reposaient sur une série de modèles de régression logistique pondérés. Nous avons utilisé l’approche des produits des coefficients de Sobel pour estimer les effets indirects, et l’autoamorçage pour estimer l’incertitude.

Résultats

La prévalence annuelle (pondérée) des troubles anxieux et/ou de l’humeur a augmenté, passant de 11,3 % en 2011 à 13,2 % en 2016. Sur la période de six ans, 23,9 à 27,7 % des personnes ayant des troubles anxieux et/ou de l’humeur ont déclaré avoir une santé moyenne/mauvaise, contre 4,9 à 6,5 % des personnes n’ayant pas de troubles anxieux et/ou de l’humeur (p < 0,001). De même, les 7,2 à 8,9 % de la population ayant déclaré avoir une santé moyenne/mauvaise étaient disproportionnellement représentés chez les personnes disant être en situation d’insécurité alimentaire (21,1-26,2 %, p < 0,001) et avoir un faible sentiment d’appartenance à la communauté (10,0-12,2 %, p < 0,001). Une prévalence significativement plus faible de mauvaise santé autoévaluée a été observée chez les répondants ayant dit avoir accès à un médecin traitant en 2012, 2015 et 2016. En 2016, le sentiment d’appartenance à la communauté et l’insécurité alimentaire modéraient de façon significative l’effet des troubles anxieux et/ou de l’humeur sur la santé générale autoévaluée. L’accès à un médecin traitant ne modérait pas ce lien.

Conclusion

Des politiques efficaces pour aborder l’insécurité alimentaire et le sentiment d’appartenance à la communauté sont nécessaires pour réduire le fardeau des troubles mentaux et améliorer la satisfaction des Canadiens face à leur santé.

Mots-clés: Sentiment d’appartenance à la communauté, cohésion communautaire, insécurité alimentaire des ménages, accès aux soins de santé, santé mentale, troubles de l’humeur, anxiété, santé générale autoévaluée

Introduction

Mental health disorders are one of the largest contributors of disease burden worldwide; when combined with substance use disorders, they are responsible for 7.4% of global disability-adjusted life years and are the leading cause of years lived with disability (Baxter et al., 2013). This global trend is mirrored in Canada, with the lifetime prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders estimated to be 12.6% (Pearson et al., 2013).

Mood and anxiety disorders have been strongly linked to poor self-rated health, a metric that predicts morbidity and mortality after adjusting for clinical health status across settings and populations (Cano et al., 2003; Goldman et al., 2004). Extrapolating from these findings, self-rated health may function as an indicator of long-term mental and physical health outcomes among individuals with mood and anxiety disorders. Based on the relationship between mental health and some social, environmental, and structural determinants of health (Orpana et al., 2016), this study sought to examine whether potentially modifiable determinants of health (with established effective interventions) mediate the relationship between mood and/or anxiety disorders and self-rated health.

We used the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) to address our objective and chose to focus on mediators such as [household] food insecurity, access to a regular medical doctor, and sense of community belonging (Breitborde et al., 2010; Clark et al., 2018; Cohen-Cline et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016; Loopstra et al., 2015; Mental Health Commission of Canada (Author), 2015; Milev et al., 2016). Food insecurity is a complex and multidimensional problem, and it extends beyond poor diet and nutrition. Different studies have established that food insecurity can have negative mental and physical health effects, and it may impose additional demands and constraints to the household income (e.g., struggle to put food on the table, to pay for housing, to feed children, and to afford their other basic needs), further aggravating the general health of these individuals (Davison & Kaplan, 2015; Hammig, 2019; Muldoon et al., 2013; Palis et al., 2020; PROOF, 2022; Tarasuk et al., 2016). Sense of community belonging has been characterized by a feeling of being connected to one’s community; and therefore, feelings of loneliness and social isolation can have a negative impact on mental health (Carpiano & Hystad, 2011; Choenarom et al., 2005; Hagerty & Williams, 1999; Steger & Kashdan, 2009). Studies have also shown that restricted healthcare access may increase the risk of harm, and chronic physical and mental conditions (Canadian Medical Association, 2018). Improving access to medical doctors, which is usually the primary point of contact between individuals and the healthcare system, has the potential to improve their overall health. Hence, assessing the role of different pathways that could explain the association of mood and/or anxiety disorders and self-rated health in Canada is important in addressing the general health of Canadians.

Materials and methods

Data source

Data were obtained from Statistics Canada’s CCHS annual survey from 2011 to 2016. The CCHS is an ongoing, national cross-sectional survey that collects information on the health status, healthcare utilization, and determinants of health of Canadian residents (Statistics Canada, 2020). This survey applies a multistage stratified cluster design to provide a representative sample of 97% of individuals who are 12 years or older living in private dwellings within Canada’s provinces and territories (Statistics Canada, 2020). CCHS includes core and optional contents; core content was asked to all respondents, while optional content was included in the survey on a biannual basis and provided at the discretion of each province or territory. In 2015, significant changes were made to the survey design to improve the sampling methodology and modernize its content (Statistics Canada, 2016). More details are available in the Supplementary materials file.

Study sample and design

The present study is confined to respondents who had a valid response to the mood disorder, anxiety disorder, sexual orientation, access to a regular medical doctor, sense of community belonging, and food insecurity questions. Invalid responses included respondents who were not asked, who refused to answer, or who responded, “I don’t know”. In the CCHS cycles 2011 to 2014, the sexual orientation question was only asked to respondents aged 18 to 59 years, whereas in the 2015 and 2016 cycles, it was asked to all respondents. Thus, for comparability purposes, the study sample was restricted to respondents aged 18 to 59 years. All variables included in this study were core content, with the exception of the Household Food Security Module, which was an optional content between 2013 and 2016. British Columbia, Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Yukon opted out of the Household Food Security Module in 2013 and 2014. In contrast, Ontario, Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Yukon opted out in 2015 and 2016.

Outcome

The outcome self-rated health was categorized by the answer to the question: “In general, how would you say your health is now? Is it… excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” Due to the limitations of available statistical software, we could only conduct mediation analyses using binary outcomes. Thus, two comparisons were made for each analysis; one between those reporting excellent/very good versus good and a second comparing fair/poor versus good.

Exposure

We examined one binary exposure variable: self-reported mood and/or anxiety disorder diagnosis (yes/no). This measure’s derivation occurred by combining answers to the mood disorder (yes/no) and anxiety disorder (yes/no) questions. These variables were based on the questions: “Now I’d like to ask about certain long-term health conditions which you may have. We are interested in “long-term conditions” which are expected to last or have already lasted 6 months or more and that have been diagnosed by a health professional. Do you have a mood disorder such as depression, bipolar disorder, mania, or dysthymia?” and “Do you have an anxiety disorder such as a phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or a panic disorder?” Respondents who answered “Yes” to either question were categorized as having a mood and/or anxiety disorder; those with neither disorder acted as the referent category.

Mediators

In this study, we focused on three mediating determinants of health, i.e., sense of community belonging, food insecurity, and access to a regular medical doctor. A sense of community belonging was evaluated by the question: “How would you describe your sense of belonging to your local community? Would you say it is… very strong, somewhat strong, somewhat weak, or very weak?” This 4-point scale is closely related to the communitarian approach to social capital, which has been shown to be associated with general well-being including self-rated health and mental health (Bassett & Moore, 2013; Carpiano & Hystad, 2011). Responses to this question were recoded into two categories: (i) strong, combining the “very strong” and “somewhat strong” responses, and (ii) weak, combining the “somewhat weak” and “very weak” responses. The CCHS assessed food insecurity in the last 12 months using the Household Food Security Survey Module developed by Health Canada, an 18-item scale for households with children, and a 10-item scale for households without children (Health Canada, 2007). This variable was recoded into two categories: (i) not food insecure (i.e., these households [adults and children] had access, at all times throughout the previous year, to enough food for an active, healthy life for all household members); and (ii) food insecure, which combined the “moderately food insecure” (i.e., at times during the previous year these households [adults or children] had indications of compromise in quality and/or quantity of food consumed) and “severely food insecure” (i.e., at times during the previous year these households [adults or children] had indications of reduced food intake and disrupted eating patterns) responses. Access to a regular medical doctor (yes/no) was addressed by the question: “Do you have a regular medical doctor?” In this question, a regular medical doctor was described as “a health professional that a person sees or talks to when they need care or advice about their health, which includes family physicians, specialists, or nurse practitioners”.

Covariates

Several determinants of health available in CCHS were adjusted for in the mediation analyses. These included sex (male, female), highest level of education (less than post-secondary, post-secondary or higher), age at survey completion (continuous and categorical: 18–29, 30–39, 40–49, and 50–59 years old), marital status (single/never married, married/common-law, and widowed/separated/divorced), household income (in Canadian dollars, $0–$39,999, $40,000–$59,999, $60,000–$99,999, and $100,000 or more), country of birth (Canada, immigrant), urban-rural status (urban/rural), and sexual orientation (heterosexual, lesbian, gay, or bisexual). This study also considered the region of residence: Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, Atlantic (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador), Prairies (Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba), and the Northern Territories (Northwest Territories, Yukon, and Nunavut).

Statistical analysis

All bivariable relationships were examined using a chi-square test for categorical variables; significance was evaluated at 0.05. A set of 500 bootstrap weights, provided by Statistics Canada, were used to estimate uncertainty accounting for household and person-level non-response and calculate the sampling weight of each respondent (Statistics Canada, 2020). Sampling weights were also considered so that the information collected through CCHS represents the health status and determinants at the national, provincial, and regional levels. Invalid responses were not imputed. Analyses were performed in SAS using survey procedures.

A series of weighted logistic regression models were constructed to evaluate the strength of the direct effect between mood and/or anxiety disorders, each mediator, and self-rated health. The indirect effect of mood and/or anxiety disorders on self-rated health was quantified using the Sobel product of coefficients approach (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). The coefficient of the indirect effect was divided by the coefficient of the total effect (sum of the coefficients of the indirect and direct effects) to calculate the percentage of the total association explained by the indirect effect (Kenny et al., 1998). Bonferroni adjustment was applied to account for multiple comparisons in the mediation analyses, resulting in a significance level of 0.025 (Hochberg, 1988). If the estimated indirect effect did not include 0 in the 97.5% confidence interval (CI), the indirect effect was statistically significant, and mediation was present. For each mediator, the models were fitted twice, first to compare the categories fair/poor versus good self-rated health, and second to compare excellent/very good versus good self-rated health.

Ethics

Ethics approval was acquired from the Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board (H18-00949).

Results

Study population

The weighted sample in our study represented 9,333,787 respondents in 2011, 9,369,507 in 2012, 7,819,517 in 2013, 7,784,060 in 2014, 5,627,687 in 2015, and 5,484,352 in 2016. Table 1 presents the distribution of the mediators, exposure, covariates, and outcome based on the weighted sample. Sex was equally distributed between males and females, and the population proportion in each age group was balanced throughout the years. Reflective of provincial population sizes and survey design, the study population predominantly lived in Ontario (35.2–48.1%) during 2011–2014 and Quebec (38.0–38.1%) during 2015–2016. Most respondents were heterosexual (96.4–97.6%), born in Canada (75.1–78.7%), married or in a common-law relationship (60.7–63.4%), lived in urban areas (81.8–83.1%), had at least post-secondary education (67.6–82.8%), and an annual household income greater than $60,000 (63.5–70.9%). Regarding a sense of community belonging, between 2011 and 2016, 35.7–39.1% of respondents reported a weak sense of community belonging. Food insecurity was less common, although still approximately one in 12 respondents (8.3–9.2%) reported that they lived in a food insecure household. Even though physician visits are publicly funded in Canada, 18.2–26.1% of our study sample reported not having a regular doctor. Overall, the study population had excellent/very good (63.1–67.1%) or good (25.6–28.4%) self-rated health, while 7.2–8.9% reported fair/poor health. The overall prevalence of mood and/or anxiety disorders increased from 11.3% in 2011 to 13.2% in 2016.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the eligible respondents from the Canadian Community Health Survey, 2011–2016

| Variables | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Weighted sample | 9,333,786 | 9,369,507 | 7,819,516 | 7,784,060 | 5,627,687 | 5,484,352 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 50.2 | 49.8 | 50.0 | 49.9 | 50.3 | 50.1 |

| Female | 49.8 | 50.2 | 50.0 | 50.1 | 49.7 | 49.9 |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–29 years | 27.8 | 28.1 | 27.8 | 28.0 | 27.0 | 25.4 |

| 30–39 years | 22.7 | 22.5 | 22.9 | 23.2 | 24.9 | 25.9 |

| 40–49 years | 24.4 | 24.4 | 24.1 | 22.7 | 22.8 | 23.0 |

| 50–59 years | 25.1 | 24.9 | 25.2 | 26.1 | 25.3 | 25.7 |

| Country of birth | ||||||

| Canada | 76.7 | 76.0 | 75.8 | 75.1 | 78.7 | 78.0 |

| Immigrant | 23.3 | 24.0 | 24.2 | 24.9 | 21.3 | 22.0 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||||

| Heterosexual | 97.6 | 97.5 | 97.2 | 97.0 | 96.7 | 96.4 |

| Gay, lesbian, or bisexual | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 3.6 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single/never married | 30.0 | 30.2 | 29.9 | 31.1 | 30.4 | 29.1 |

| Married/common law | 61.6 | 61.7 | 61.6 | 60.7 | 62.3 | 63.4 |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 8.4 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 8.3 | 7.3 | 7.5 |

| Highest level of education | ||||||

| Less than post-secondary | 17.2 | 17.6 | 18.6 | 17.2 | 29.8 | 32.4 |

| Post-secondary or higher | 82.8 | 82.4 | 81.4 | 82.8 | 70.2 | 67.6 |

| Household income | ||||||

| 0 to $39,999 | 20.0 | 19.8 | 18.9 | 18.5 | 16.6 | 16.5 |

| $40,000 to $59,999 | 16.5 | 16.3 | 15.6 | 16.1 | 14.1 | 12.6 |

| $60,000 to $99,999 | 29.2 | 28.9 | 27.3 | 27.0 | 28.6 | 25.3 |

| $100,000 or more | 34.3 | 34.9 | 38.1 | 38.4 | 40.7 | 45.6 |

| Region of residence | ||||||

| Ontario | 38.8 | 35.2 | 48.1 | 47.1 | N/A | N/A |

| Quebec | 22.8 | 21.0 | 27.2 | 27.6 | 38.1 | 38.0 |

| British Columbia | 13.4 | 21.0 | N/A | N/A | 21.4 | 21.5 |

| Atlantic | 6.9 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 8.5 | 8.1 |

| Prairies | 17.8 | 16.5 | 18.4 | 19.0 | 31.7 | 32.0 |

| Northern Territories | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Urban rural status | ||||||

| Urban | 83.1 | 82.8 | 82.8 | 82.2 | 81.8 | 82.0 |

| Rural | 16.9 | 17.2 | 17.2 | 17.8 | 18.2 | 18.0 |

| Self-rated health | ||||||

| Excellent/very good | 64.4 | 64.2 | 63.4 | 63.1 | 67.1 | 66.0 |

| Good | 27.0 | 27.6 | 28.4 | 28.0 | 25.6 | 26.3 |

| Fair/poor | 8.6 | 8.1 | 8.2 | 8.9 | 7.2 | 7.8 |

| Mood and/or anxiety disorder (binary) | ||||||

| No | 88.7 | 88.6 | 88.6 | 87.9 | 87.8 | 86.8 |

| Yes | 11.3 | 11.4 | 11.4 | 12.1 | 12.2 | 13.2 |

| Mood and/or anxiety disorder (categorical) | ||||||

| No mood or anxiety disorder | 88.7 | 88.6 | 88.6 | 87.9 | 87.8 | 86.8 |

| Only mood disorder | 4.3 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.2 |

| Only anxiety disorder | 3.9 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 4.7 |

| Mood and anxiety disorders | 3.1 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 4.4 |

| Sense of community belonging | ||||||

| Strong | 60.9 | 62.1 | 61.0 | 62.1 | 62.7 | 64.3 |

| Weak | 39.1 | 37.9 | 39.0 | 37.9 | 37.3 | 35.7 |

| Food insecurity | ||||||

| Not food insecure | 91.4 | 90.8 | 91.5 | 91.7 | 91.0 | 91.1 |

| Food insecure | 8.6 | 9.2 | 8.5 | 8.3 | 9.0 | 8.9 |

| Access to a regular medical doctor | ||||||

| Yes | 80.9 | 81.3 | 80.8 | 81.8 | 73.9 | 75.9 |

| No | 19.1 | 18.7 | 19.2 | 18.2 | 26.1 | 24.1 |

*Weighted total (N): Population counts presented represent the weighted sample size calculated using sample weights provided by Statistics Canada. N/A, not applicable since data on food security was not collected in the region during a particular year

Association between study variables and self-rated health

Table 2 presents the bivariable association between self-rated health, the mediators, and mood and/or anxiety disorders from 2011 to 2016. Although only 7.2–8.9% of the population reported fair/poor self-rated health, these respondents were disproportionately represented among individuals with mood and/or anxiety disorders (23.9–27.7% across all years, p<0.001 for all), food insecurity (21.1–26.2%, p<0.001), and a weak sense of community belonging (10.0–12.2%, p<0.001). While access to a regular medical doctor was not significantly associated with the outcome in 2011, 2013, and 2014, it was significantly associated with self-rated health in 2012 (p=0.014), 2015 (p<0.001), and 2016 (p<0.001). A higher prevalence of fair/poor self-rated health was observed among individuals with access to a regular medical doctor during the study years (2012 [yes vs no]: 8.6% vs 6.4%; 2015: 7.8% vs 5.5%; 2016: 8.5% vs 5.5%). Supplementary materials file eTable 1 presents the bivariable analyses for all other covariates.

Table 2.

Distribution of mediators and exposure grouped by level of self-rated health of respondents to the Canadian Community Health Survey, 2011–2016

| Variable | Mood and/or anxiety disorder | Sense of community belonging | Food Insecurity | Access to a regular medical doctor | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p-value | Strong | Weak | p-value | Not food insecure | Food insecure | p-value | Yes | No | p-value | |

| 2011 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.222 | ||||||||

| Excellent/very good | 67.6 | 39.8 | 68.3 | 58.4 | 66.4 | 43.2 | 64.3 | 64.9 | ||||

| Good | 26.0 | 34.6 | 24.9 | 30.2 | 26.6 | 31.2 | 26.8 | 27.6 | ||||

| Poor/fair | 6.4 | 25.6 | 6.8 | 11.3 | 7.0 | 25.6 | 8.9 | 7.5 | ||||

| 2012 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.014 | ||||||||

| Excellent/very good | 67.6 | 37.5 | 67.0 | 59.5 | 66.7 | 39.5 | 64.0 | 65.1 | ||||

| Good | 26.4 | 37.7 | 26.6 | 29.3 | 26.9 | 35.0 | 27.5 | 28.5 | ||||

| Poor/fair | 6.0 | 24.7 | 6.3 | 11.1 | 6.4 | 25.5 | 8.6 | 6.4 | ||||

| 2013 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.347 | ||||||||

| Excellent/very good | 66.6 | 38.4 | 66.9 | 57.9 | 65.5 | 40.9 | 63.1 | 64.4 | ||||

| Good | 27.7 | 33.9 | 26.6 | 31.2 | 28.0 | 33.0 | 28.4 | 28.2 | ||||

| Poor/fair | 5.7 | 27.7 | 6.5 | 11.0 | 6.6 | 26.2 | 8.4 | 7.4 | ||||

| 2014 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.440 | ||||||||

| Excellent/very good | 66.8 | 36.0 | 67.0 | 56.7 | 65.2 | 39.7 | 63.2 | 62.5 | ||||

| Good | 26.7 | 38.1 | 26.1 | 31.2 | 27.3 | 35.7 | 27.8 | 29.3 | ||||

| Poor/fair | 6.5 | 25.9 | 6.8 | 12.2 | 7.4 | 24.6 | 9.0 | 8.2 | ||||

| 2015 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Excellent/very good | 71.0 | 39.7 | 70.6 | 61.4 | 69.4 | 44.9 | 66.2 | 69.9 | ||||

| Good | 24.1 | 36.4 | 23.9 | 28.7 | 24.8 | 34.1 | 26.0 | 24.5 | ||||

| Poor/fair | 4.9 | 23.9 | 5.6 | 10.0 | 5.8 | 21.1 | 7.8 | 5.5 | ||||

| 2016 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Excellent/very good | 70.5 | 36.6 | 69.3 | 60.0 | 68.5 | 40.0 | 65.1 | 68.8 | ||||

| Good | 24.5 | 37.7 | 24.8 | 28.9 | 25.3 | 36.3 | 26.4 | 25.7 | ||||

| Poor/fair | 5.0 | 25.7 | 5.9 | 11.1 | 6.2 | 23.7 | 8.5 | 5.5 | ||||

Note: Chi-squared tests were applied to test for statistically significant differences for each year. There were no multiple comparisons in this table; and thus, no Bonferroni correction was applied to these p-values. Rows sum to 100%

Mediation analysis

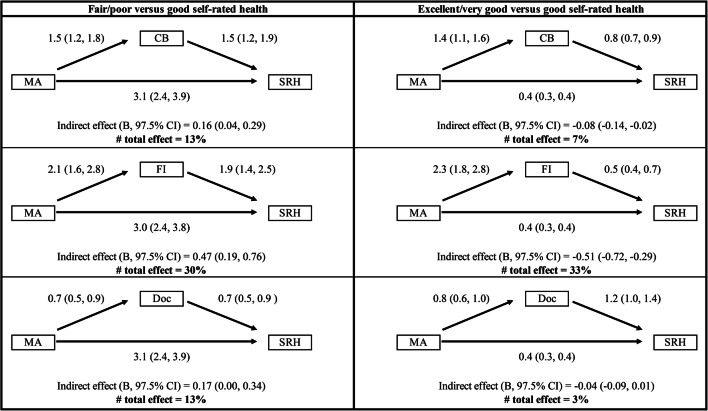

Here, we present the mediation results for the 2016 CCHS cycle (Fig. 1), since these were the most recent data available in our study and were consistent with the results from 2011 to 2015. The complete mediation analysis for 2011–2016 is presented in Supplementary materials file eTables 2–4.

Fig. 1.

Mediation results of food insecurity, sense of community belonging, and access to a regular medical doctor between mood and/or anxiety disorder diagnosis and self-rated health. Note: Sex, age, sexual orientation, the highest level of education, household income, marital status, country of birth, and region of Canada were controlled for as covariates; aOR = adjusted odds ratio; 97.5% CI = 97.5% confidence interval; B, the regression coefficient for the indirect effect; MA, mood and/or anxiety disorder (Yes vs No [reference]); CB, sense of community belonging (weak vs strong [reference]); FI, food insecurity (food insecure vs not food insecure [reference]); Doc, access to a regular medical doctor (no vs yes [reference]); SRH, self-rated health

Sense of community belonging

Respondents with mood and/or anxiety disorders were more likely to experience a weak sense of community belonging (adjusted odds ratio, 97.5% CI: 1.5, 1.2–1.8); those with a weak sense of community belonging were more likely to report fair/poor self-rated health (1.5, 1.2–1.9). Respondents who reported fair/poor self-rated health were more likely to have a mood and/or anxiety disorder (3.1, 2.4–3.9). The indirect effect of a sense of community belonging accounted for 13% of the total pathway between mood and/or anxiety disorder and good versus fair/poor self-rated health, suggesting a sense of community belonging mediated a small proportion of this pathway. These findings were moderately attenuated when comparing respondents with excellent/very good to good self-rated health; among these groups, respondents’ sense of community belonging explained only 7% of the total effect.

Food insecurity

Respondents with mood and/or anxiety disorders were more likely to experience food insecurity (2.1, 1.6–2.8) and respondents with food insecurity were more likely to experience fair/poor compared to good self-rated health (1.9, 1.4–2.5). Those with mood and/or anxiety disorder were more likely to report fair/poor self-rated health (3.0, 2.4–3.8). The indirect effect of food insecurity was significant and explained 30% of the total effect of mood and/or anxiety disorders on fair/poor versus good self-rated health in our adjusted models. When the analysis was repeated to compare individuals with excellent/very good versus good self-rated health, the conclusions were mostly similar.

Access to a regular medical doctor

Respondents with a mood and/or anxiety disorder diagnosis were less likely to report not having access to a regular medical doctor (0.7, 0.5–0.9), and respondents without access to a regular medical doctor were less likely to report fair/poor self-rated health (0.7, 0.5–0.9). When the analysis was repeated to compare individuals with excellent/very good versus good self-rated health, the conclusions were mostly similar. There was no significant indirect effect observed in the analysis at either level of self-rated health, indicating access to a regular medical doctor did not mediate this relationship.

Discussion

This large serial cross-sectional study examined to what extent the pathway from mood and/or anxiety disorders to self-rated health was mediated by food insecurity, sense of community belonging, and access to a regular medical doctor. Within our study population of Canadian adults aged 18–59 years, we reported an almost fivefold higher prevalence of poor/fair self-rated health among individuals with mood and/or anxiety disorders compared to those without these mental health disorders. Our analyses also provided evidence that food insecurity, and to a lesser extent a weak sense of community belonging, partially mediated this relationship after adjustment for key determinants of health (mediation effect 30% and 13%, respectively). We did not find consistency in the mediation results for access to a regular medical doctor.

The strong negative impact of food insecurity on mental health and self-rated health observed in our analysis has previously been reported in other settings, including Australia, New Zealand, and the United States (Jones, 2017). Studies examining the potential proportion of mental health disorders attributable to food insecurity are scarce. However, one study using pooled CCHS data from 2005 to 2012 estimated that, after controlling for confounding risk factors, a substantive decline in household food insecurity could reduce the prevalence of anxiety disorders and depressive thoughts by 8% and 25% respectively (Jessiman-Perreault & McIntyre, 2017). Individuals living in food insecure households tend to have a poor diet, suboptimal intake of essential nutrients, and stress since they are forced to make difficult trade-off decisions (e.g., eating or paying for housing, going hungry or providing food to their children), which may result in mental dysfunction and physical health problems, which can impact their general health (Loftus et al., 2021; Maynard et al., 2018; Nagata et al., 2019; PROOF, 2022; Vozoris & Tarasuk, 2003). These findings, in combination with our analysis, merit the consideration of population health interventions shown to decrease household food insecurity, such as those that provide social assistance and reduce income volatility, which may also help alleviate the burden of mental health disorders (Li et al., 2016; Rizvi et al., 2021). For example, a pilot study for basic income in Ontario reported that recipients experienced reduced anxiousness and depression in addition to improved housing security, ability to pay for medication, social relationships, and food insecurity (Ferdosi et al., 2020). These findings highlight the far-reaching effects of poverty alleviation strategies and present an additional justification of enhanced mental health outcomes when decision-makers consider new policies and interventions.

The mediation of sense of community belonging is consistent with prior research. Path analyses have demonstrated a direct path from a low sense of belonging to depression symptoms in clinical and community samples within the USA (Hagerty & Williams, 1999). Thus, enhancing social support and improving access to initiatives that promote community connectiveness and decrease negative health behaviour may be potential targets for population-level interventions to improve outcomes among those with mental health disorders (Carpiano & Hystad, 2011). For example, integrating green or natural spaces into long-term development plans has been shown to improve sense of community belonging and mental health (Cohen-Cline et al., 2015; Rugel et al., 2019). Increasing community investments and pro-social community spaces and places, in both urban and rural communities, has been pivotal in decreasing social isolation and improving mental and physical health (Francis et al., 2012; Litman & desLibris, 2020).

Our analysis did not find a mediation effect of access to a regular medical doctor. The non-significant effect observed in this study could be explained by other factors, such as structural and attitudinal barriers to treatment initiation and continuation, being more significant when individuals with mood and/or anxiety disorders assess their general health (Knaak et al., 2017; Mojtabai et al., 2011). Alternatively, access to a regular medical doctor, as defined in our study, may not reflect access to appropriate mental healthcare. Prior studies examining access to psychotherapy in British Columbia and Ontario demonstrated that fewer than one in five individuals met their need for psychotherapy or counselling through the public system (Kurdyak et al., 2020; Puyat et al., 2016). Recent data from England’s National Health Service indicate that increasing access to psychotherapy has resulted in marked improvements in outcomes among individuals with mental health disorders (Clark et al., 2018). Last, in Canada, healthcare is administered locally, and therefore, asking about people’s access to a regular medical doctor may not be a reliable/comparable measure across different provinces and territories. Thus, the fact that this mediator did not reach significance does not mean that the relationship that we explored does not exist, but it can be a result of the way this variable was measured in CCHS.

The main strength of our study is the use of a large population-based sample of Canadian adults aged 18–59 years that provides greater representativeness than clinical or convenience samples. There are certain limitations to consider. First, an ideal mediation analysis would utilize longitudinal data. Given the cross-sectional nature of the CCHS, causality of the mediating variables could not be inferred. Second, since this is a self-reported survey, some individuals may have undiagnosed mood and/or anxiety disorders or they may not report their disorder due to social desirability bias. In 2011, a paper examining primary care diagnosis of mood and anxiety disorders in Ontario, British Columbia, and Nova Scotia reported that dependent on the disorder, between 41.5 and 81.3% of patients may go undiagnosed, a factor that would introduce bias in this study (Vermani et al., 2011). However, a recent paper examining under-reporting in self-reported compared to administrative datasets in Canada suggests that these biases may have progressively declined over time (O’Donnell et al., 2016). For these reasons, we speculate that the prevalence of mood and/or anxiety disorders may have been underestimated in this study, but that this underestimation is likely driven by undiagnosed cases in comparison to under-reporting. We do not expect the previous issue to have a significant effect on the mediation analyses presented in this study. Third, sense of community belonging was assessed by a single-item question, which does not address the multidimension construct of this variable (McMillan & Chavis, 1986). Finally, the sampling methodology change could have affected the mediation results for access to a regular medical doctor. In the last 2 years of the study, the percentage of participants reporting a lack of access dramatically increased, and the association of this mediator with mood and/or anxiety disorders and self-rated health was inconsistent throughout the study period. Thus, whether this was an actual or artifactual increase, and whether the change in methodology influenced our mediation results, we need to examine future CCHS cycles.

Conclusion

This study highlights the mediating role of community belonging and food insecurity in the pathway between mood and/or anxiety disorders and self-rated health. Further research should be conducted to identify programs and policies that are effective in improving these determinants of health, and to address the consequences and drivers of mood and/or anxiety disorders across regions in Canada.

Contributions to knowledge

What does this study add to existing knowledge?

It is important to note that although the prevalence of individuals reporting being food insecure in Canada has remained stable at 9%, the prevalence of those reporting having a weak sense of belonging to a community is high, but it is becoming less common over time (from 39% in 2011 to 35% in 2016).

Our analysis suggests that socio-economic stressors, i.e., food insecurity and a weak sense of community belonging, experienced by our population partially explain how those with mood and/or anxiety disorders rate their general health satisfaction.

What are the key implications for public health interventions, practice or policy?

Our results underpin the need to implement efficient policy interventions targeting food insecurity and sense of community belonging to decrease the burden of mental health in Canada, and help Canadians achieve greater general health satisfaction.

Policies shown to decrease household food insecurity, including programs that provide social assistance and reduce income volatility, have the potential to help alleviate the effects of poverty and decrease the burden of mental health disorders.

Public health interventions that enhance social support and improve access to initiatives that promote community connectedness will be important in decreasing social isolation and the burden of mental health disorders.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 184 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank the respondents who participated in the Canadian Community Household survey and Statistics Canada for their assistance with data access.

Author contributions

Initial study concept and design: DN, VDL; analysis and interpretation of data: DN, HT, VDL; statistical analysis: DN, HT, VDL; drafting of the manuscript: DN, AP, VDL; consultation regarding study design and interpretation of findings: DN, AP, HT, KS, DM, VDL; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: DN, AP, HT, KS, DM, VDL; final approval of the manuscript to be published: DN, AP, HT, KS, DM, VDL; study supervision: VDL, KS, DM.

Funding

This work was supported by the following sources of funding: VDL is funded by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PJT-148595 and PJT-156147), and the Canadian Foundation for AIDS Research (CANFAR Innovation Grant – 30-101). DM is supported by a Scholar Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Availability of data and material

Statistics Canada restricts access to detailed microdata from the Canadian Community Health Survey and other data sources to researchers with a study proposal approved through the Statistics Canada microdata application process, and who meet the requirements to become a deemed employee of Statistics Canada. Researchers from post-secondary institutions within Canada or outside Canada may apply for access to the detailed microdata. For information on the application process, visit: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/microdata/data-centres.

Code availability

The underlying analytical codes are available from the authors on request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate and for publication

Survey participation is voluntary. Data are collected under the authority of the Statistics Act, Revised Statutes of Canada, 1985, Chapter S-19. The information is kept strictly confidential. The Statistics Act contains very strict confidentiality provisions that protect collected information from unauthorized access.

Ethics

Ethics approval was acquired from the Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board, ethics certificate number H18-00949.

Disclaimer

This study was granted approval by two academic peers and a Statistics Canada Subject Matter Expert as per the evaluation process facilitated by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. A Microdata Research Contract between the researchers and Statistics Canada was signed and security clearance was confirmed, thus granting access to the Research Data Centre to conduct these analyses. No findings or beliefs presented in this manuscript are a reflection of Statistics Canada.

Reporting guidelines

This paper is compliant with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for cross-sectional studies.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bassett E, Moore S. Mental health and social capital: Social capital as a promising initiative to improving the mental health of communities (Chapter 28) 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-regression. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43(5):897–910. doi: 10.1017/S003329171200147X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitborde NJ, Srihari VH, Pollard JM, Addington DN, Woods SW. Mediators and moderators in early intervention research. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2010;4(2):143–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2010.00177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Medical Association. (2018). Ensuring equitable access to health care: Strategies for governments, health system planners, and the medical profession. Retrieved 20 January 2020 from https://policybase.cma.ca/en/permalink/policy11062

- Cano A, Scaturo DJ, Sprafkin RP, Lantinga LJ, Fiese BH, Brand F. Family support, self-rated health, and psychological distress. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;5(3):111–117. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v05n0302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano, R. M., & Hystad, P. W. (2011, Mar). “Sense of community belonging” in health surveys: What social capital is it measuring? Health Place, 17(2), 606–617. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Choenarom C, Williams RA, Hagerty BM. The role of sense of belonging and social support on stress and depression in individuals with depression. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2005;19(1):18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Canvin L, Green J, Layard R, Pilling S, Janecka M. Transparency about the outcomes of mental health services (IAPT approach): An analysis of public data. Lancet. 2018;391(10121):679–686. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32133-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Cline H, Turkheimer E, Duncan GE. Access to green space, physical activity and mental health: A twin study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(6):523–529. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison KM, Kaplan BJ. Food insecurity in adults with mood disorders: Prevalence estimates and associations with nutritional and psychological health. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2015;14:21. doi: 10.1186/s12991-015-0059-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdosi, M., McDowell, T., Lewchuk, W., & Ross, S. (2020). Southern Ontario’s basic income experience. Retrieved 7 February 2020 from https://hamiltonpoverty.ca/preview/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Southern-Ontarios-Basic-Income-Experience_R5-1.pdf.

- Francis, J., Giles-Corti, B., Wood, L., & Knuiman, M. (2012). Creating sense of community: The role of public space. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 32(4), 401–409. 10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.07.002

- Goldman N, Glei DA, Chang MC. The role of clinical risk factors in understanding self-rated health. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(1):49–57. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerty, B. M., & Williams, A. (1999). The effects of sense of belonging, social support, conflict, and loneliness on depression. Nursing Research, 48(4). https://journals.lww.com/nursingresearchonline/Fulltext/1999/07000/The_Effects_of_Sense_of_Belonging,_Social_Support,.4.aspx [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hammig O. Health risks associated with social isolation in general and in young, middle and old age. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. (2007). Canadian Community Health Survey, Cycle 2.2, Nutrition (2004): Income-related household food security in Canada. Government of Canada. Retrieved 7 February 2020 from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-nutrition-surveillance/health-nutrition-surveys/canadian-community-health-survey-cchs/canadian-community-health-survey-cycle-2-2-nutrition-2004-income-related-household-food-security-canada-health-canada-2007.html

- Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75(4):800–802. doi: 10.2307/2336325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jessiman-Perreault G, McIntyre L. The household food insecurity gradient and potential reductions in adverse population mental health outcomes in Canadian adults. SSM - population health. 2017;3:464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A. D. (2017, 2017/08/01/). Food insecurity and mental health status: A global analysis of 149 countries. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(2), 264–273. 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kenny, D., Kashy, D., & Bolger, N. (1998). Data analysis in social psychology (4 ed., Vol. 1). McGraw-Hill.

- Knaak, S., Mantler, E., & Szeto, A. (2017). Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: Barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthcare Management Forum, 30(2), 111–116. 10.1177/0840470416679413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kurdyak, P., Zaheer, J., Carvalho, A., de Oliveira, C., Lebenbaum, M., Wilton, A. S., Fefergrad, M., Stergiopoulos, V., & Mulsant, B. H. (2020). Physician-based availability of psychotherapy in Ontario: A population-based retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open, E105–E115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li N, Dachner N, Tarasuk V. The impact of changes in social policies on household food insecurity in British Columbia, 2005–2012. Preventive Medicine. 2016;93:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litman, T., & desLibris, D. (2020). Urban sanity: understanding urban mental health impacts and how to create saner, happier cities. Victoria Transport Policy Institute. https://www-deslibris-ca.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/ID/10103800

- Loftus, E. I., Lachaud, J., Hwang, S. W., & Mejia-Lancheros, C. (2021). Food insecurity and mental health outcomes among homeless adults: A scoping review. Public Health Nutrition, 24(7), 1766–1777. 10.1017/S1368980020001998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Loopstra R, Dachner N, Tarasuk V. An exploration of the unprecedented decline in the prevalence of household food insecurity in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2007–2012. Canadian Public Policy. 2015;41(3):191–206. doi: 10.3138/cpp.2014-080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, M., Andrade, L., Packull-McCormick, S., Perlman, C. M., Leos-Toro, C., & Kirkpatrick, S. I. (2018). Food insecurity and mental health among females in high-income countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(7), 1424. 10.3390/ijerph15071424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McMillan DW, Chavis DM. Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology. 1986;14(1):6–23. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(198601)14:1<6::AID-JCOP2290140103>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Commission of Canada (Author) Informing the future: Mental health indicators for Canada. Health Canada. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Milev RV, Giacobbe P, Kennedy SH, Blumberger DM, Daskalakis ZJ, Downar J, Modirrousta M, Patry S, Vila-Rodriguez F, Lam RW, MacQueen GM, Parikh SV, Ravindran AV. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: Section 4. Neurostimulation Treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):561–575. doi: 10.1177/0706743716660033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Sampson NA, Jin R, Druss B, Wang PS, Wells KB, Pincus HA, Kessler RC. Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2011;41(8):1751–1761. doi: 10.1017/s0033291710002291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon KA, Duff PK, Fielden S, Anema A. Food insufficiency is associated with psychiatric morbidity in a nationally representative study of mental illness among food insecure Canadians. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(5):795–803. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0597-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata JM, Palar K, Gooding HC, Garber AK, Bibbins-Domingo K, Weiser SD. Food insecurity and chronic disease in US young adults: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(12):2756–2762. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05317-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, S., Vanderloo, S., McRae, L., Onysko, J., Patten, S. B., & Pelletier, L. (2016, Aug). Comparison of the estimated prevalence of mood and/or anxiety disorders in Canada between self-report and administrative data. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 25(4), 360–369. 10.1017/s2045796015000463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Orpana, H., Vachon, J., Dykxhoorn, J., McRae, L., & Jayaraman, G. (2016, Jan). Monitoring positive mental health and its determinants in Canada: The development of the Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada, 36(1), 1–10. 10.24095/hpcdp.36.1.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Palis H, Marchand K, Oviedo-Joekes E. The relationship between sense of community belonging and self-rated mental health among Canadians with mental or substance use disorders. J Ment Health. 2020;29(2):168–175. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2018.1437602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson C, Janz T, Ali J. Statistics Canada. 2013. Mental and substance use disorders in Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. [DOI] [PubMed]

- PROOF . Household Food Insecurity in Canada. University of Toronto; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Puyat JH, Kazanjian A, Goldner EM, Wong H. How often do individuals with major depression receive minimally adequate treatment? A population-based, data linkage study. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2016;61(7):394–404. doi: 10.1177/0706743716640288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi, A., Wasfi, R., Enns, A., & Kristjansson, E. (2021). The impact of novel and traditional food bank approaches on food insecurity: A longitudinal study in Ottawa, Canada. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 771–771. 10.1186/s12889-021-10841-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rugel, E. J., Carpiano, R. M., Henderson, S. B., & Brauer, M. (2019). Exposure to natural space, sense of community belonging, and adverse mental health outcomes across an urban region. Environmental Research, 171, 365–377. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada . Summary of changes - Surveys and statistical programs - Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). Statistics Canada. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2020). Canadian Community Health Survey - Annual Component (CCHS). Retrieved 7 February 2020 from https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getInstanceList&Id=1263799

- Steger, M. F., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Depression and everyday social activity, belonging, and well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(2), 289–300. 10.1037/a0015416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tarasuk, V., Mitchell, A., & Dachner, N. (2016). Household food insecurity in Canada, 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2018 from http://proof.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Household-Food-Insecurity-in-Canada-2014.pdf

- Vermani, M., Marcus, M., & Katzman, M. A. (2011). Rates of detection of mood and anxiety disorders in primary care: A descriptive, cross-sectional study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord, 13(2). 10.4088/PCC.10m01013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vozoris NT, Tarasuk VS. Household food insufficiency is associated with poorer health. J Nutr. 2003;133(1):120–126. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 184 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Statistics Canada restricts access to detailed microdata from the Canadian Community Health Survey and other data sources to researchers with a study proposal approved through the Statistics Canada microdata application process, and who meet the requirements to become a deemed employee of Statistics Canada. Researchers from post-secondary institutions within Canada or outside Canada may apply for access to the detailed microdata. For information on the application process, visit: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/microdata/data-centres.

The underlying analytical codes are available from the authors on request.