Abstract

Cytokines such as gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) inhibit the intracellular replication of Chlamydia pneumoniae or Chlamydia trachomatis. In this study, we found that another cytokine, lymphotoxin (TNF-β), restricts the growth of C. pneumoniae in HEp-2 cells. When lymphotoxin (10 U/ml) was added during incubation from 8 to 16 h postinoculation, inclusion body formation was severely reduced. In addition, we observed activation of nitric oxide production and the nuclear transition of NF-κB in HEp-2 cells in response to lymphotoxin. These results suggest that inhibition of chlamydial growth by lymphotoxin is mediated, at least in part, by nuclear transition of NF-κB, resulting in induction of nitric oxide synthase to produce nitric oxide, a potent bacteristatic agent. This is the first report on antichlamydial activity of lymphotoxin through induction of nitric oxide.

Chlamydia pneumoniae is an obligate intracellular bacterium that can cause upper and lower respiratory tract infections in humans (15). In addition, infection with this microorganism has been associated with chronic inflammatory diseases such as asthma (17) and atherosclerosis (26). Recent reports on isolation of C. pneumoniae from specimens of coronary artery atheroma (33) and carotid artery atheroma (20) further implicate the bacterium as a causative agent of atherosclerosis.

Various cytokines have been demonstrated to restrict the growth of intracellular pathogens and are significant activators of host cell immune responses to infections. Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) has been implicated in chlamydial control in humans and experimental animals (3, 4, 6, 7, 18, 22). The biochemical basis of the antichlamydial action of IFN-γ may include the induction of intracellular enzymes such as inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in rodent (22, 27) and indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which in turn activates host cell tryptophan catabolism in humans (3, 6, 7, 28, 38). In addition to IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) is a mediator of inflammation and plays a role in host defense against C. trachomatis infection (9, 35, 41). In various cell types, both IFN-γ and TNF-α activate iNOS, which catalyzes the conversion of l-arginine to citrulline and nitric oxide (NO), an important antimicrobial and tumoricidal agent as well as a cell signaling molecule (2, 24, 29, 39). Nevertheless, the reports regarding the relative roles of iNOS and other mechanisms of cytokine-mediated inhibition of intracellular chlamydial growth have, in general, been categorized according to whether they have involved rodent systems (iNOS) or human systems (IDO).

Lymphotoxin (LT), a cytokine secreted by activated macrophages and lymphocytes (13), has approximately 30% homology in its amino acid sequence to TNF-α (31). LT and TNF-α are encoded by closely linked genes that are included in the human major histocompatibility complex (37), share a common cell surface receptor, p55 (1, 30), and have similar biological activities (14). Thus, LT has also been called TNF-β (34). In addition, both TNF-α and LT activate a nuclear transcription factor, NF-κB, in human macrophage-like U-937 cells (8). In the present study, we tested whether LT is also implicated in the growth of C. pneumoniae. Our findings show that LT has antichlamydial activity that may be mediated by nuclear transition of NF-κB, resulting in the induction of iNOS. This is the first report that LT has antichlamydial activity and iNOS plays a role in the antichlamydial system in humans.

Determination of chlamydial growth.

HEp-2 (ATCC CCL 23) cells were allowed to adhere to 96-well tissue culture plates and grown in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (GIBCO) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum and gentamicin (50 μg/ml) for 72 h prior to use.

C. pneumoniae TW183 (Washington Research Foundation, Seattle) was passaged, titrated, and stored at −80°C until use. The stock chlamydial suspension was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline, and a 0.2-ml aliquot (1.5 × 103 inclusion-forming units [IFU]) was added to monolayers. Infection was established by centrifugation (700 × g) at 22°C for 1 h, followed by incubation at 36°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 1 h. Then the inoculum was aspirated and replaced with a medium consisting of Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium, 10% fetal calf serum, cycloheximide (1.5 μg/ml), and gentamicin (50 μg/ml) (CP medium). LT was purified from culture supernatant of CHO cells transfected with human LT genomic DNA as described previously (11).

The infected HEp-2 cells grown in CP medium were incubated with LT at for an 8-h period before or after inoculation. At the end of each period, the cells were washed once with and placed in fresh prewarmed CP medium and then incubated for up to 48 h.

The infected monolayers were fixed for 15 min in 95% ethanol and stained with a C. pneumoniae-specific monoclonal antibody (RR402; 400-fold dilution; Washington Research Foundation) and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulins (20-fold dilution; DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark). Cells were examined under a fluorescence microscope at a magnification of ×100 for IFU, determined on the basis of the average numbers of inclusion bodies per field determined from three fields per well from triplicate samples. Percent inhibition of chlamydial growth was calculated [(IFU of control) − (IFU of treated sample)/(IFU of control)] × 100.

Values are expressed as means ± standard errors of the mean of triplicate assays. Student’s unpaired t tests were used to assess the statistical significance of differences. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Effect of LT on chlamydial growth.

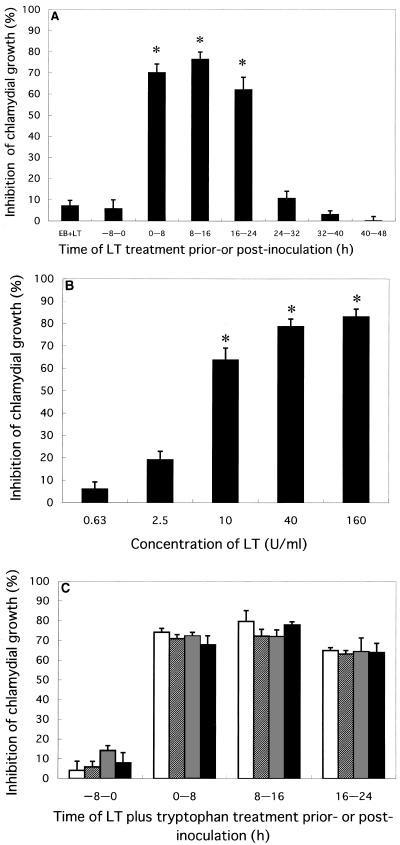

Studies were carried out to determine whether LT affects the infectivity and/or replication of C. pneumoniae in HEp-2 cells. Incubation with LT (10 U/ml) for 8 h from 0 to 8 h, 8 to 16 h, or 16 to 24 h postinoculation reduced the growth of C. pneumoniae at 48 h postinoculation by 70, 77, or 62%, respectively, whereas little inhibition was observed by incubation with LT for 8 h from 24 to 32 h, 32 to 40 h, or 40 to 48 h postinoculation (Fig. 1A). Chlamydial growth was not affected when the HEp-2 cells were treated with LT for 8 h or chlamydial microorganisms were treated with LT for 1 h just prior to inoculation. A titration curve of LT on chlamydial growth revealed that LT at concentrations above 10 U per ml inhibited growth (Fig. 1B). Since l-tryptophan is reported to rescue C. pneumoniae from the bacteristatic effect of IFN-γ (38), we tested whether exogenous tryptophan reduced LT-mediated inhibition of chlamydial growth. When C. pneumoniae-infected cells were incubated with LT in the absence or presence of various concentrations of l-tryptophan, chlamydial growth was similarly reduced (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

(A) Inhibition of chlamydial growth by LT in HEp-2 cells. C. pneumoniae elementary bodies were treated with LT (10 U/ml) for 1 h prior to infection (EB+LT), or confluent HEp-2 monolayers were infected with C. pneumoniae, and LT (10 U/ml) was added at indicated time periods for 8 h before or after infection. Incubations were carried out at 36°C for 48 h postinoculation in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. (B) Dose-dependent inhibition of chlamydial growth by LT in HEp-2 cells. LT was added for 8 h from 8 to 16 h postinoculation. (C) Effect of tryptophan on antichlamydial activity of LT. LT (10 U/ml) alone or with tryptophan (0 [open bars], 1 [hatched bars], 10 [stippled bars], or 100 [filled bars] μg per ml) was added to HEp-2 cells pre- or postinoculation. Incubations were carried out for 36 h postinoculation. Chlamydial growth was determined with a C. pneumoniae-specific monoclonal antibody under a fluorescence microscope (magnification, ×100). Inhibition of chlamydial growth is expressed as percent inhibition ± standard error. Differences in comparison with the untreated control in panels A and B were significant (∗, P < 0.001).

Growth of C. pneumoniae in BHK cells producing LT.

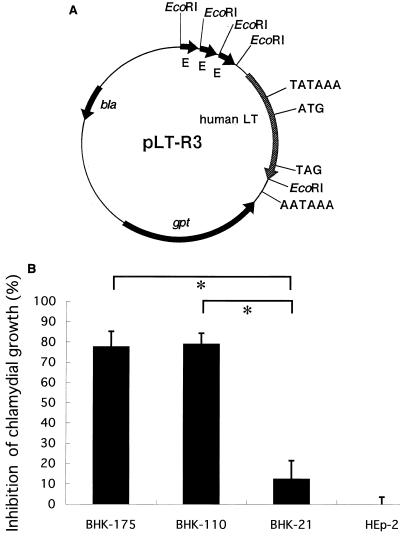

To assess the effect of endogenously produced LT on chlamydial infectivity, we constructed a plasmid, pLT-R3, containing the human LT gene to obtain stable transfectants carrying the human LT gene (Fig. 2A). DNA transfection and selection of stable transformants were carried out according to the method of Yamashita et al. (43). After a 2-week incubation of BHK-21(C-13) (ATCC CCL 10) cells transfected with micromolar amounts of pLT-R3 DNA, two stable transformants, BHK-110 and BHK-175, were obtained.

FIG. 2.

(A) Structure of plasmid pLT-R3, carrying the human LT gene (human LT), the Escherichia coli guanine phosphoribosyltransferase gene (gpt), and the β-lactamase gene (bla) on a pUC replicon. The human LT gene has the native promoter sequence (TATAAA). Three tandemly repeated enhancer sequences are derived from the long terminal repeat sequence of Rous sarcoma virus (E). The start codon (ATG), the stop codon (TAG), and the polyadenylation signal (AATAAA) for LT are also indicated. Plasmid pLT was constructed from pSV2gpt, pUC12, and an EcoRI fragment containing human LT gene by several sequential steps (43). Then the EcoRI fragment from pSVcat (12) containing the long terminal repeat of Rous sarcoma virus was inserted into the EcoRI site of pLT located upstream from the LT promoter in the sense direction to produce plasmid pLT-R3. (B) Inhibition of chlamydial growth in LT-producing cells. Confluent cell monolayers were infected with C. pneumoniae and incubated for 36 h. Growth of C. pneumoniae was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 1 and is expressed as percent inhibition ± standard error. Differences in experimental groups were significant (∗, P < 0.01).

The inhibition of IFU in the transfectants was about 80% at 36 h postinoculation (Fig. 2B), close to that in HEp-2 cells incubated with 10 U of LT per ml (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that extracellular LT produced by the transfectants inhibits chlamydial growth, although it remains possible that intracellular LT directly inhibits growth. In a separate experiment, we determined LT by an L-M cell (ATCC CCL 1.2) lytic assay (43). The transfectants BHK-175 and BHK-110 produced LT in 24-h culture supernatants at levels of 64 to 128 and 32 to 64 U per ml, respectively, whereas nontransfected BHK-21 and HEp-2 cells did not produce detectable levels of LT. Thus, the inhibition of chlamydial growth in LT-producing cells appeared to be lower than that expected from the levels of LT produced, possibly due to the difference in responsiveness to LT between BHK cells and HEp-2 cells. Based on these results, we concluded that chlamydia-susceptible cells could be transformed to low-susceptibility cells by introducing the LT gene.

Role of NO in antichlamydial activity of LT.

Since antichlamydial cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ induce iNOS, we tested whether LT also induces iNOS in infected cells. HEp-2 cells were treated with LT in the presence of N-guanidino-monomethyl-l-arginine acetate (MLA; WAKO, Osaka, Japan), a specific inhibitor of NO synthase (24). Cycloheximide was omitted from the medium when MLA was added. Cells were grown in 96-well tissue culture plates, infected with 1.5 × 103 IFU of C. pneumoniae per well, and incubated at 36°C for 48 h. NO production was assessed by determining nitrite concentrations in culture supernatant by using Griess reagent as described previously (16).

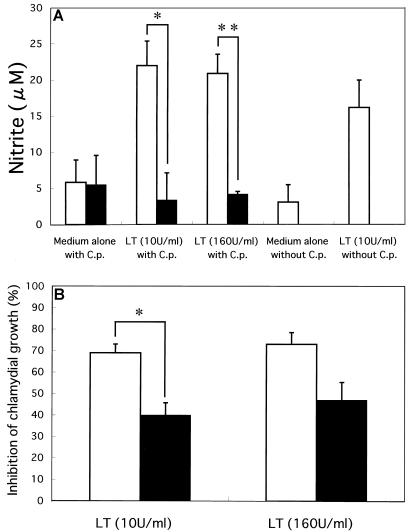

Nitrite levels in the supernatants of HEp-2 cells uninfected or infected with C. pneumoniae increased three- to fivefold when LT was added (Fig. 3A). When the NO synthase inhibitor MLA was added with LT, the nitrite levels were reduced to less than 20%. In accordance with these observations, the chlamydial growth inhibited by LT was rescued significantly by adding MLA (Fig. 3B). Based on these results, we concluded that LT exhibits antichlamydial activity, at least in part, by inducing NO synthesis. These results provided initial evidence that iNOS plays a role in the antichlamydial system in humans.

FIG. 3.

(A) NO production by LT-treated HEp-2 cells without or with C. pneumoniae infection and its inhibition by MLA. HEp-2 cells noninfected or infected with C. pneumoniae were incubated with LT (10 or 160 U/ml) without (open bars) or with (filled bars) 1 mM MLA. After 48 h of incubation, the concentration of nitrite in the supernatant was determined with a spectrophotometric assay using Griess reagent. Nitrite concentrations are expressed as means ± standard errors of triplicate wells. Differences in experimental groups were significant (∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01). (B) Inhibition of chlamydial growth by LT in the absence or presence of MLA. HEp-2 cells received LT (10 or 160 U/ml) without (open bars) or with (filled bars) 1 mM MLA just after inoculation of C. pneumoniae. Inhibition of chlamydial growth was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 1 and is expressed as percent inhibition ± standard error. Differences in experimental groups were significant (∗, P < 0.01).

Nuclear transition of NF-κB in HEp-2 cells treated with LT.

Since induction of iNOS is dependent on NF-κB that is activated for transport to the nucleus (23), we determined the effect of LT on nuclear transition of NF-κB by an indirect method with a rabbit anti-human NF-κB antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.) and fluorescein-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin. When examined under a fluorescence microscope, HEp-2 cells treated for 15 min with LT at concentrations from 7.25 to 116 U per ml showed significant nuclear transition of NF-κB, whereas cells treated with LT at concentrations below 3.63 U per ml did not show the nuclear transition even after prolonged incubation (data not shown). These results suggested that LT treatment activates NF-κB, which in turn may activate iNOS.

In this study, we showed that LT treatment of C. pneumoniae-infected HEp-2 cells markedly reduced the formation of inclusion bodies. The highest inhibition was observed when LT was present for 8 h from 8 to 16 h postinoculation (Fig. 1A), which may correspond to the time period of chlamydial replication (5).

Previous studies have demonstrated that IFN-γ or TNF-α reduces chlamydial infectivity in vitro (3, 4, 35, 38). However, there has been no report on the effect of LT (TNF-β) on chlamydial infectivity. Many mammalian cells show sensitivity to LT or express the receptors for LT (or TNF) (14, 31). BHK-21 cells also express the receptor for LT (44), and HEp-2 cells were found to be responsive to LT in this study. LT as well as TNF-α and IFN-γ are strong activators of NF-κB (8), a transcriptional enhancer as well as a critical component in the signal transduction pathways leading to induction of iNOS (42). We have shown for the first time that LT efficiently induces iNOS in vitro in HEp-2 cells either without or with C. pneumoniae infection (Fig. 3A). Since the antichlamydial activity of LT was partially suppressed by adding MLA, an NO synthase inhibitor (Fig. 3B), NO seemed to play a role in the antichlamydial activity. Furthermore, LT induced nuclear transition of NF-κB in HEp-2 cells, suggesting that the NF-κB-mediated induction of iNOS (42) is involved in antichlamydial activity.

When HEp-2 cells were treated with LT for 8 h just prior to C. pneumoniae inoculation, infectivity was not affected (Fig. 1A), suggesting that the LT-primed NO production, even if lasting after removal of LT, was not sufficient to suppress the infection. The marked antichlamydial effect of LT added at the first 8-h period may be due to the inhibition of induced phagocytosis of elementary bodies, their transformation to reticulate bodies, and/or initiation of replication of reticulate bodies. However, there are several equally plausible explanations for the antichlamydial effects of NO, including inhibition of chlamydial DNA replication and inhibition of host cell respiration (5, 10, 24, 25, 29, 40).

Tryptophan is an essential amino acid for chlamydiae, and it has been suggested that its intracellular pool decreases as a consequence of enzymatic degradation by IFN-γ-induced IDO, resulting in restriction of chlamydial growth to a persistent state (3, 4). The antichlamydial activity of IFN-γ alone or with TNF-α can be suppressed by the addition of tryptophan (3, 6, 36, 38). In contrast, elevation of tryptophan concentrations in the medium did not affect the anti-C. pneumoniae activity of LT, as shown in this study. Therefore, we concluded that the induction of IDO may not be a major cause of the antichlamydial activity of LT observed in this study.

It should be noted that the addition of MLA did not result in complete blocking of the antichlamydial activity of LT (Fig. 3B), suggesting that iNOS induction may not be the sole mechanism for the inhibition of chlamydial growth by LT. Recent studies on iNOS knockout mice indicated that iNOS is dispensable for the removal of C. trachomatis from the genital epithelium (18). TNF-α has been shown to induce low amounts of mRNA for IFN-β, an antiviral agent, in HEp-2 cells (21). We assessed the anti-C. pneumoniae activity of other cytokines, including IFN-α, IFN-β, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and found that these cytokines failed to suppress intracellular growth of chlamydiae (data not shown). LT and TNF-α share a common surface receptor subunit, p55, but TNF-α requires additionally subunit p75 for its binding (19). It is possible that these cytokines exert antichlamydial effects via different mechanisms.

Further investigations on the function of LT and the intracellular fate of C. pneumoniae may shed light on the mechanism of persistent infection and lead to the development of new therapeutic approaches toward the treatment of atherosclerosis mediated by C. pneumoniae infection.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports of Japan (G09877059) and by a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS-FRTF97L00101).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aggarwal B B, Eessalu T E, Hass P E. Characterization of receptors for human tumour necrosis factor and their regulation by γ-interferon. Nature. 1985;318:665–667. doi: 10.1038/318665a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amber I J, Hibbs J B, Jr, Taintor R R, Vavrin Z. Cytokines induce an L-arginine-dependent effector system in nonmacrophage cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1988;44:58–65. doi: 10.1002/jlb.44.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beatty W L, Belanger T A, Desai A A, Morrison R P, Byrne G I. Tryptophan depletion as a mechanism of gamma interferon-mediated chlamydial persistence. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3705–3711. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3705-3711.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beatty W L, Byrne G I, Morrison R P. Morphologic and antigenic characterization of interferon γ-mediated persistent Chlamydia trachomatis infection in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3998–4002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.3998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beatty W L, Morrison R P, Byrne G I. Persistent chlamydiae: from cell culture to a paradigm for chlamydial pathogenesis. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:686–699. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.4.686-699.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrne G I, Lehmann L K, Landry G J. Induction of tryptophan catabolism is the mechanism for gamma-interferon-mediated inhibition of intracellular Chlamydia psittaci replication in T24 cells. Infect Immun. 1986;53:347–351. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.2.347-351.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlin J M, Weller J B. Potentiation of interferon-mediated inhibition of Chlamydia infection by interleukin-1 in human macrophage cultures. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1870–1875. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1870-1875.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaturvedi M M, Higuchi M, Aggarwal B B. Effect of tumor necrosis factors, interferons, interleukins, and growth factors on the activation of NF-κB: evidence for lack of correlation with cell proliferation. Lymphokine Cytokine Res. 1994;13:309–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darville T, Laffoon K K, Kishen L R, Rank R G. Tumor necrosis factor alpha activity in genital tract secretions of guinea pigs infected with chlamydiae. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4675–4681. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4675-4681.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drapier J-C, Hibbs J B., Jr Differentiation of murine macrophages to express nonspecific cytotoxicity for tumor cells results in l-arginine-dependent inhibition of mitochondrial iron-sulfur enzymes in the macrophage effector cells. J Immunol. 1988;140:2829–2838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukushima K, Watanabe H, Takeo K, Nomura M, Asahi T, Yamashita K. N-linked sugar chain structure of recombinant human lymphotoxin produced by CHO cells: the functional role of carbohydrate as to its lectin-like character and clearance velocity. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;304:144–153. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorman C M, Merlino G T, Willingham M C, Pastan I, Howard B H. The Rous sarcoma virus long terminal repeat is a strong promoter when introduced into a variety of eukaryotic cells by DNA-mediated transfection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:6777–6781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.22.6777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granger G A, Williams T W. Lymphocyte cytotoxicity in vitro: activation and release of a cytotoxic factor. Nature. 1968;218:1253–1254. doi: 10.1038/2181253a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray P W, Aggarwal B B, Benton C V, Bringman T S, Henzel W J, Jarrett J A, Leung D W, Moffat B, Ng P, Svedersky L P, Palladino M A, Nedwin G E. Cloning and expression of cDNA for human lymphotoxin, a lymphokine with tumour necrosis activity. Nature. 1984;312:721–724. doi: 10.1038/312721a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grayston J T. Infections caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae, strain TWAR. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:757–763. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.5.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green S J, Aniagolu J, Raney J J. Oxidative metabolism of murine macrophages. In: Coligan J E, editor. Current protocols in immunology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1994. pp. 14.5.1–14.5.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hahn D L, Dodge R W, Golubjatnikov R. Association of Chlamydia pneumoniae (strain TWAR) infection with wheezing, asthmatic bronchitis, and adult-onset asthma. JAMA. 1991;266:225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Igietseme J U, Perry L L, Ananaba G A, Uriri I M, Ojior O O, Kumar S N, Caldwell H D. Chlamydial infection in inducible nitric oxide synthase knockout mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1282–1286. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1282-1286.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwamoto S, Shibuya I, Takeda K, Takeda M. Lymphotoxin lacks effects on 75-kDa receptors in cytotoxicity on U-937 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199:70–77. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson L A, Campbell L A, Kuo C-C, Rodriguez D I, Lee A, Grayston J T. Isolation of Chlamydia pneumoniae from a carotid endarterectomy specimen. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:292–295. doi: 10.1086/517270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobsen H, Mestan J, Mittnacht S, Dieffenbach C W. Beta interferon subtype 1 induction by tumor necrosis factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3037–3042. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.7.3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johansson M, Schön K, Ward M, Lycke N. Genital tract infection with Chlamydia trachomatis fails to induce protective immunity in gamma interferon receptor-deficient mice despite a strong local immunoglobulin A response. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1032–1044. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.1032-1044.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleinert H, Euchenhofer C, Ihrig-Biedert I, Förstermann U. In murine 3T3 fibroblasts, different second messenger pathways resulting in the induction of NO synthase II (iNOS) converge in the activation of transcription factor NF-κB. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6039–6044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knowles R G, Moncada S. Nitric oxide synthases in mammals. Biochem J. 1994;298:249–258. doi: 10.1042/bj2980249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lepoivre M, Chenais B, Yapo A, Lemaire G, Thelander L, Tenu J-P. Alterations of ribonucleotide reductase activity following induction of the nitrite-generating pathway in adenocarcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:14143–14149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linnanmäki E, Leinonen M, Mattila K, Nieminen M S, Valtonen V, Saikku P. Chlamydia pneumoniae-specific circulating immune complexes in patients with chronic coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1993;87:1130–1134. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.4.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayer J, Woods M L, Vavrin Z, Hibbs J B., Jr Gamma interferon-induced nitric oxide production reduces Chlamydia trachomatis infectivity in McCoy cells. Infect Immun. 1993;61:491–497. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.491-497.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray H W, Szuro-Sudol A, Wellner D, Oca M J, Granger A M, Libby D M, Rothermel C D, Rubin B Y. Role of tryptophan degradation in respiratory burst-independent antimicrobial activity of gamma interferon-stimulated human macrophages. Infect Immun. 1989;57:845–849. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.3.845-849.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nathan C. Nitric oxide as a secretory product of mammalian cells. FASEB J. 1992;6:3051–3064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patton J S, Shepard H M, Wilking H, Lewis G, Aggarwal B B, Eessalu T E, Gavin L A, Grunfeld C. Interferons and tumor necrosis factors have similar catabolic effects on 3T3 L1 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8313–8317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pennica D, Nedwin G E, Hayflick J S, Seeburg P H, Derynck R, Palladino M A, Kohr W J, Aggarwal B B, Goeddel D V. Human tumour necrosis factor: precursor structure, expression and homology to lymphotoxin. Nature. 1984;312:724–729. doi: 10.1038/312724a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Puolakkainen M, Kuo C-C, Shor A, Wang S-P, Grayston J T, Campbell L A. Serological response to Chlamydia pneumoniae in adults with coronary arterial fatty streaks and fibrolipid plaques. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2212–2214. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2212-2214.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramirez J A, Ahkee S, Summersgill J T, Ganzel B L, Ogden L L, Quinn T C, Gaydos C A, Bobo L L, Hammerschlag M R, Roblin P M, LeBar W, Grayston J T, Kuo C-C, Campbell L A, Patton D L, Dean D, Schachter J. Isolation of Chlamydia pneumoniae from the coronary artery of a patient with coronary atherosclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:979–982. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-12-199612150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shalaby M R, Aggarwal B B, Rinderknecht E, Svedersky L P, Finkle B S, Palladino M A., Jr Activated of human polymorphonuclear neutrophil functions by interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factors. J Immunol. 1985;135:2069–2073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shemer-Avni Y, Wallach D, Sarov I. Inhibition of Chlamydia trachomatis growth by recombinant tumor necrosis factor. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2503–2506. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.9.2503-2506.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shemer-Avni Y, Wallach D, Sarov I. Reversion of the antichlamydial effect of tumor necrosis factor by tryptophan and antibodies to beta interferon. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3484–3490. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3484-3490.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spies T, Morton C C, Nedospasov S A, Fiers W, Pious D, Strominger J L. Genes for the tumor necrosis factors α and β are linked to the human major histocompatibility complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8699–8702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.22.8699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Summersgill J T, Sahney N N, Gaydos C A, Quinn T C, Ramirez J A. Inhibition of Chlamydia pneumoniae growth in HEp-2 cells pretreated with gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2801–2803. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2801-2803.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei X-Q, Charles I G, Smith A, Ure J, Feng G-J, Huang F-P, Xu D, Mullar W, Moncada S, Liew F Y. Altered immune responses in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase. Nature. 1995;375:408–411. doi: 10.1038/375408a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wharton M, Granger D L, Durack D T. Mitochondrial iron loss from leukemia cells injured by macrophages. J Immunol. 1988;141:1311–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams D M, Magee D M, Bonewald L F, Smith J G, Bleicker C A, Byrne G I, Schachter J. A role in vivo for tumor necrosis factor alpha in host defense against Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1572–1576. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1572-1576.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie Q-W, Kashiwabara Y, Nathan C. Role of transcription factor NF-κB/Rel in induction of nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4705–4708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamashita K, Ikenaka Y, Kakutani T, Kawaharada H, Watanabe K. Comparison of human lymphotoxin gene expression in CHO cells directed by genomic DNA or cDNA sequences. Agric Biol Chem. 1990;54:2801–2809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamashita, K., et al. Unpublished data.