Abstract

Background/objective

Cryopreservation of grafts is not common practice in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients. However, our center had to use cryopreserved cells for allogeneic HSCT during the COVID-19 pandemic to avoid delays in transplantation due to uncertainty regarding patient and donor exposures.

Study design

We retrospectively evaluated post-transplant engraftment and survival outcomes of adult patients who received cryopreserved versus fresh allografts during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

Fifty-five patients with hematologic malignancies received either cryopreserved (n = 34) or fresh (n = 21) allogeneic HSCT using peripheral blood stem cells between January 2020 and December 2020. At a median follow-up time of 15 months, cryopreserved allograft recipients had significantly lower overall survival (OS) (p = 0.02). They also experienced significantly delayed neutrophil (p = 0.01) and platelet engraftments (p < 0.0001), as well as higher red blood cell transfusion-dependence after day + 60 (67.6% vs. 28.6%; p = 0.01). Significantly more cryopreserved allograft recipients received donor lymphocyte infusion than fresh allograft recipients (35.3% vs. 4.8%, p = 0.01). Neither relapse-free survival nor non-relapse mortality differed significantly between the two groups.

Conclusion

Cryopreservation of allografts in combination with post-transplant cyclophosphamide may negatively affect engraftment and OS outcomes in HSCT recipients.

Keywords: Cryopreservation, Engraftment, Allogeneic, Transplantation, COVID-19

Introduction

Cryopreservation of hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) in autologous and cord blood transplantation is a common practice. On the other hand, fresh allograft infusion is standard in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) [1].

In the pre-COVID-19 era, cryopreserved allo-HSCT was typically reserved for donor accommodation, and unanticipated changes in patient status. Transplanting cryopreserved HPCs provides several advantages. It offers the ability to evaluate HPC quality while ensuring an adequate amount is collected prior to the initiation of conditioning regimen, and it provides a solution to logistical challenges such as flexibility of international transportation and other unforeseen obstacles [2]. These benefits are offset by decreased viability of cryopreserved cells, the toxic effect of longer term cell exposure to dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), added cost, and more graft manipulation [3, 4].

Although there is plenty of evidence on the safety and efficacy of cryopreserved autograft [5], data on the outcomes of cryopreserved allo-HSCT has been mixed and limited [2–14]. Some studies showed increased risk of graft failure and higher mortality rate, while others showed no impact on survival or engraftment.

Due to travel restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, transplant centers were faced with the uncertainty of graft and/or donor transport. To ensure allo-HSCT graft availability at the scheduled infusion time, the National Marrow Donor Program® (NMDP) required all unrelated donor (URD) products to be cryopreserved prior to initiation of conditioning regimen starting on March 30, 2020. This requirement was relaxed to allow fresh allografts to be infused for collections scheduled on or after August 10, 2020 [15]. Although cryopreservation was not required for related donor products, concern over COVID-19 infections forced many transplant centers to cryopreserve these products as well.

We retrospectively examined the effect of cryopreservation on the outcomes of allo-HSCT in 2020 at our institution. The outcomes in 55 adult patients with hematologic malignancies who underwent either cryopreserved or fresh allo-HSCT using peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) as the graft source between January 2020 and December 2020 were analyzed.

Materials and methods

Study population

A single center, retrospective cohort study was conducted. All adult patients undergoing allo-HSCT for hematologic malignancies between January 1, 2020 and December 31, 2020 at our transplant center were included in this analysis. All patients received PBSC grafts and were censored at last documented follow-up visit, with a minimum follow-up period of 12 months in surviving patients. Donors were tested for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR prior to graft collection, and recipients were tested for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR before starting the conditioning regimen. This study was approved by the AdventHealth Institutional Review Board. All patients provided written informed consent.

HPC product collection, cryopreservation procedure, analysis, and infusion

All allogeneic HPC products were collected via peripheral blood apheresis from granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) mobilized donors. Collections took place at our institution or at other NMDP centers. At our institution, all collections were conducted on Spectra Optia apheresis instruments (Terumo BCT, Lakewood CO). The HPC products were then processed (plasma depleted, if required) and either infused fresh or cryopreserved and thawed prior to infusion in a 37 °C water bath using gentle agitation to a slushy consistency. All cryopreserved products were mixed with a freezing media containing Plasmalyte, 5% human serum albumin (HSA) (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) or concurrent plasma and DMSO to achieve a final concentration of 10% DMSO and frozen in a controlled rate freezer (Planar, Kryo 560, Middlesex, UK) to approximately -90 °C, then transferred to a liquid nitrogen storage freezer (less than -165 °C). All HPC products were frozen within 24 h of collection if collected on-site, within 48 h if collected domestically, and within 72 h if collected internationally. All cryopreserved products were thawed either in the cell therapy facility or at bedside and were infused within 60 min of thawing. All HPC products were tested for CD34+ and CD3+, then were calculated and reported as cells × 106/L and cells × 106/kg of recipient body weight. CD34+concentration (per µL), frequency (among CD45+events) and viability [frequency of 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD)] were assessed using the Stem Cell Enumeration (SCE) kit (Becton–Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) as a single-platform.

Endpoints Definition

Engraftment kinetics, overall survival (OS), and relapse-free survival (RFS) were evaluated. OS was defined as the time from transplantation until death. RFS was defined as the time from transplantation until disease relapse. Other specific secondary outcomes included neutrophil engraftment, platelet engraftment, graft failure, poor graft function, cumulative incidence of acute GVHD (aGVHD) and chronic GVHD (cGVHD), and non-relapse mortality (NRM). Neutrophil engraftment was defined as the first of three consecutive days with an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) > 0.5 × 109/L, and platelet engraftment was defined as the first of three consecutive days with platelet count > 20 × 109/L without transfusions in the prior 7 days. Primary graft failure was defined as never having achieved an ANC ≥ 0.5 × 109/L in the absence of disease relapse. Secondary graft failure was defined as loss of a previously functioning graft associated with loss of full donor chimerism. Poor graft function was defined as two or three cytopenias for > 2 weeks, after day + 28 in the presence of donor chimerism > 5% [16]. Acute and chronic GVHD were diagnosed and graded according to standard criteria [17, 18]. Complete remission (CR) was defined by standard morphological criteria. Liquid transit time was defined as the time from completion of stem cell collection to start of stem cell cryopreservation. Time to infusion was defined as the time from completion of stem cell collection to completion of stem cell infusion.

Statistical analysis

We used the Kaplan–Meier analysis to compare the OS, RFS, and NRM of the patients transplanted with cryopreserved or fresh stem cells. We plotted accumulated incidence for the time to neutrophil engraftment and platelet engraftment. Univariate linear regression was used to evaluate the correlation between liquid transit time and engraftment. We used log-rank test for OS, RFS, NRM, and time to engraftment. Censor date was set at March 20, 2022. The Cox proportional hazards model was used for the multivariant analysis for the OS, RFS, and NRM. The multivariant analysis of OS, RFS, and NRM included type of transplantation (cryopreserved vs. fresh), age, disease status at the time of transplant (CR vs. non-CR), moderate to severe cGVHD, and CMV reactivation by day 100. We used the Mann–Whitney U test to compare the continuous variables. Chi square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare the categorical variables between patients who had cryopreserved or fresh transplantation. All analyses were done in R version 4.0.

Results

Patient and graft baseline characteristics

A total of 55 patients who underwent allo-HSCT in the year of 2020 were analyzed in the study. Thirty-four patients (61.8%) received cryopreserved HPC products while 21 (38.2%) patients received fresh HPC products. All patients received post-transplant cyclophosphamide on day + 3 and day + 4, as well as tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil for GVHD prophylaxis. The median duration of follow-up was 15 months (range: 3–24) for the entire cohort, 14 months (range: 3–22) for the cryopreserved cohort, and 15 months (range: 8–24) for the fresh cohort. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patient population

| Characteristic | Cryopreserved n = 34 |

Fresh n = 21 |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 55 (21–74) | 53 (19–70) | 0.70 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.16 | ||

| Male | 22 (64.7) | 9 (42.9) | |

| Female | 12 (35.3) | 12 (57.1) | |

| Race, n (%) | 1.00 | ||

| White | 25 (73.5) | 15 (71.4) | |

| African American | 4 (11.8) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 4 (11.8) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Graft source, n (%) | 0.33 | ||

| MRD | 4 (11.8) | 1 (4.8) | |

| MUD | 18 (52.9) | 8 (38.1) | |

| MMRD | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Haploidentical | 12 (35.3) | 11 (52.3) | |

| ABO compatibility, n (%) | 0.16 | ||

| Matched | 12 (35.3) | 13 (61.9) | |

| Minor mismatch | 11 (32.4) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Major mismatch | 11 (32.4) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Bidirectional | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Disease risk index, n (%) | 0.09 | ||

| Low | 8 (23.5) | 3 (14.3) | |

| Intermediate | 9 (26.5) | 12 (57.1) | |

| High | 17 (50.0) | 6 (28.6) | |

| Disease, n (%) | 0.49 | ||

| AML | 21 (61.8) | 10 (47.6) | |

| MDS | 5 (14.7) | 3 (14.3) | |

| ALL | 2 (5.9) | 5 (23.8) | |

| Other | 6 (17.6) | 3 (14.3) | |

| Disease status, n (%) | 0.75 | ||

| CR | 25 (73.5) | 17 (81.0) | |

| Non-CR | 9 (26.5) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Minimal residual disease prior to HSCT | 0.44 | ||

| No | 19/25 (76.0) | 15/17 (88.2) | |

| Yes | 6/25 (24.0) | 2/17 (11.8) | |

| AML cytogenetics | 0.03 | ||

| Favorable | 8/21 (38.1) | 1/10 (10.0) | |

| Intermediate | 4/21 (19.0) | 5/10 (50.0) | |

| Adverse | 9/21 (42.9) | 2/10 (20.0) | |

| Unknown | 0/21 (0.0) | 2/10 (20.0) | |

| ECOG, n (%) | 0.52 | ||

| < 2 | 32 (94.1) | 21 (100.0) | |

| ≥ 2 | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Conditioning intensity, n (%) | 1.00 | ||

| Myeloablative | 27 (79.4) | 17 (81.0) | |

| RIC | 7 (20.6) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Conditioning regimen | 0.13 | ||

| Flu/Bu4 | 20 (58.8) | 6 (28.6) | |

| Flu/Bu3 | 4 (11.8) | 3 (14.3) | |

| Flu/Bu2 | 2 (5.9) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Flu/TBI | 3 (8.8) | 8 (38.1) | |

| Flu/Cy/TBI | 4 (11.8) | 3 (14.3) | |

| Other | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Liquid transit time, hours, median (range) |

22.3 (1.75–84.03) |

NA | NA |

| Time to infusion, hours, median (range) |

261.86 (53.33–2447.77) |

24.35 (2.57–215.13) |

< 0.0001 |

AML acute myelogenous leukemia, ALL acute lymphoblastic leukemia, CR complete remission, ECOG eastern cooperative oncology group, MDS myelodysplastic syndrome, MMRD mismatched related donor, MRD matched related donor, MUD matched-unrelated donor, RIC reduced intensity conditioning, Flu/Bu4 fludarabine and 4 days of busulfan, Flu/Bu3 fludarabine and 3 days of busulfan, Flu/Bu2 fludarabine and 2 days of busulfan, Flu/TBI fludarabine and total body irradiation, Flu/Cy/TBI fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and total body irradiation

There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, gender, race, graft source, ECOG score, distribution of hematologic diagnosis, disease risk index, ABO compatibility, disease status or MRD status prior to transplantation. Conditioning intensity and regimen were comparable between the two groups. Among the AML patients, there was a statistically significant difference in the AML cytogenetics risk, with a higher proportion of patients with favorable and adverse risk in the cryopreserved allograft group, while more patients in the fresh allograft group had intermediate risk (p < 0.03). Table 2 shows graft characteristics, the median CD34+, CD3+, total nucleated cell (TNC) and percent viability of cells infused.

Table 2.

Graft characteristics of fresh and cryopreserved peripheral blood stem cell products

| Characteristic | Cryopreserved n = 34 |

Fresh n = 21 |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Pre-freeze CD34+ cell dose, × 106/kg, median (range) |

5.05 (2.71–10.19) | NA | NA |

|

Infused CD34+ cell dose, × 106/kg, median (range) |

5.05 (2.11–8.56) | 6.36 (5.00–12.27) | 0.01 |

|

Infused CD3+ cell dose, × 108/kg, median (range) |

1.34 (0.50–3.73) | 1.24 (0.51–3.49) | 0.53 |

|

Infused TNC dose, × 108/kg, median (range) |

5.48 (2.28–12.66) | 5.00 (2.88–12.05) | 0.03 |

|

Infused TNC Viability, %, median (range) |

83 (69–94) | 100 (100–100) | < 0.001 |

NA not applicable, TNC total nucleated cell

Hematopoietic recovery

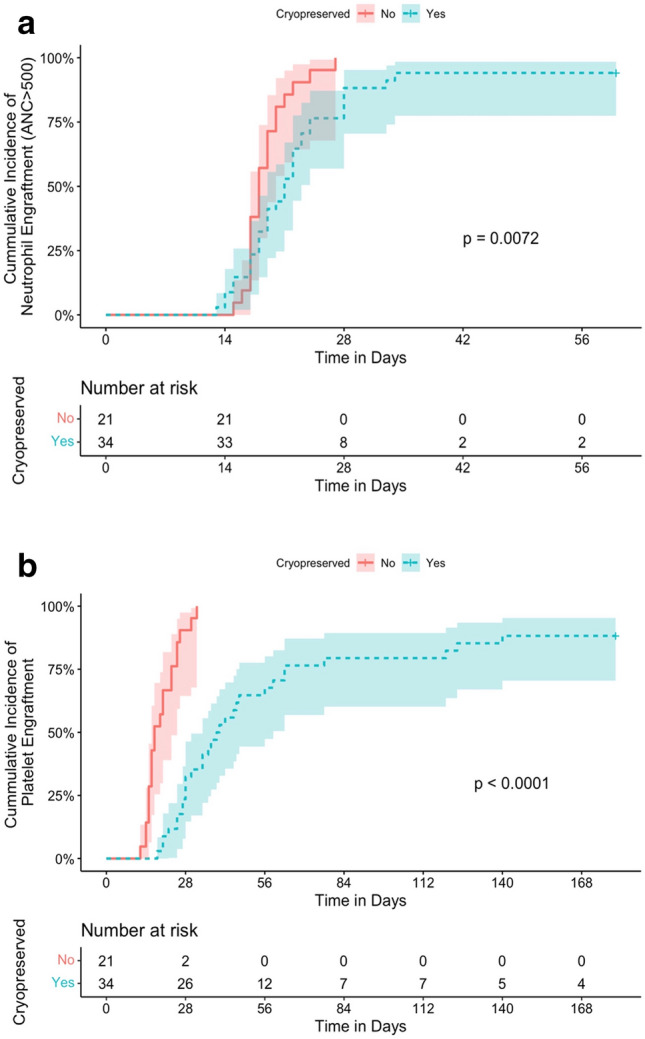

We observed two graft failures in the recipients of cryopreserved grafts. One patient suffered primary graft failure while the other experienced secondary graft failure. The two patient’s baseline characteristics and outcomes are shown in Table 3. In patients who achieved engraftment, a statistically significant longer time to neutrophil and platelet engraftments were observed in the cryopreserved as compared to the fresh group (p = 0.01 and p < 0.0001, respectively) (Fig. 1a and Fig. 1b). In the cryopreserved group, no correlation was observed between delayed engraftment and longer liquid transit time (p = 0.42, and p = 0.14, respectively) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Summary of cases with graft failure in cryopreserved group

| Gender/Age, year | Disease | AML cytogenetics | Remission status at transplant | Conditioning regimen | Donor type | CD34+ cell dose pre-frozen, × 106/kg | CD34+ cell dose infused, × 106/kg | Total nucleated cell dose infused, × 108/kg | Graft failure | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/54 | AML | Favorable | CR | Flu/Bu3 | Haplo | 5.43 | 4.34 | 8.54 | Primary | Alive s/p 2nd transplant |

| Female/62 | AML | Favorable | CR | Flu/Bu4 | MUD | 10.19 | 8.56 | 3.69 | Secondary | Alive s/p 2nd transplant |

AML acute myelogenous leukemia, CR complete remission, Flu/Bu4 fludarabine and 4 days of busulfan, Flu/Bu3 fludarabine and 3 days of busulfan, Haplo haploidentical, MUD matched-unrelated donor, s/p status post

Fig. 1.

a Cumulative incidence of neutrophil engraftment; b Cumulative incidence of platelet engraftment

Table 4.

Univariate linear regression analysis of liquid transit time with neutrophil and platelet engraftment in cryopreserved patients

| Neutrophil engraftment | Platelet engraftment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r2 | Regression coefficient (95% CI) |

p-Value | r2 | Regression coefficient (95% CI) |

p-Value | |

| Liquid transit time | 0.02 |

−27.254 (−95.68–41.20) |

0.42 | 0.07 |

−1.24 (-2.91–0.42) |

0.14 |

CI confidence interval

Poor graft function occurred in 44.1% of cryopreserved allografts, while only 28.6% of fresh allografts had poor graft function (p = 0.27). We observed a significant difference in the cumulative incidence of red blood cell (RBC) transfusions after day + 60 between the two groups (67.6% in the cryopreserved group vs. 28.6% in the fresh group, p = 0.01). The difference in the cumulative incidence of donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) between the two groups was also significant (p = 0.03). Of the 12 patients who required DLI in the cryopreserved group, six (50%) were due to poor chimerism or poor graft function, while the rest (50%) were due to relapse. Only one patient (4.8%) in the fresh group received DLI for relapse treatment. No difference was found in terms of cumulative incidence of second allo-HSCT (p = 1.00). Four patients (11.8%) in the cryopreserved allograft group underwent a second allo-HSCT, two (50%) as a result of relapse and two (50%) due to graft failure. In the fresh allograft group, two patients (9.6%) underwent second allo-HSCT due to relapse.

GVHD

There were no significant differences in the cumulative incidence of aGVHD or cGVHD between the two groups. The cumulative incidence of aGVHD grade II-IV was 58.8% in the cryopreserved group and 42.9% in the fresh group (p = 0.28). Grade III-IV aGVHD was observed in four (11.7%) and two (9.5%) patients (p = 1.00), respectively. The cumulative incidence of cGVHD was 64.7 and 76.2% (p = 0.55), and the cumulative incidence of moderate to severe cGVHD was 49.4% and 9.5% (p = 0.10) in the two groups, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

Transplant outcomes

| Cryopreserved n = 34 |

Fresh n = 21 |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median time to neutrophil engraftment, days (range) | 21 (13–34)* | 18 (15–27) | 0.05 |

| Median time to platelet engraftment, days, (range) | 39.5 (18–140)** | 20 (14–382) | < 0.0001 |

| Graft function, n (%) | |||

| Graft failure | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.52 |

| Poor graft function | 15 (44.1) | 6 (28.6) | 0.27 |

| Donor lymphocyte infusion, n (%) | 0.03 | ||

| Yes, for relapse | 7 (20.6) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Yes, for poor chimerism | 5 (14.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No | 22 (64.7) | 20 (95.2) | |

| RBC transfusion after day + 60, n (%) | 0.01 | ||

| Yes | 23 (67.6) | 6 (28.6) | |

| No | 11 (32.4) | 15 (71.4) | |

| aGVHD grade II-IV, n (%) | 0.28 | ||

| No | 20 (58.8) | 9 (42.9) | |

| Yes | 14 (41.2) | 12 (57.1) | |

| aGVHD grade III-IV, n (%) | 4 (11.7) | 2 (9.5) | 1.00 |

| cGVHD, total, n (%) | 0.55 | ||

| No | 22 (64.7) | 16 (76.2) | |

| Yes | 12 (35.3) | 5 (23.8) | |

| cGVHD, moderate to severe, n (%) | 10 (49.4) | 2 (9.5) | 0.10 |

| CMV reactivation by day + 100, n (%) | 0.46 | ||

| No | 27 (79.4) | 19 (90.5) | |

| Yes | 7 (20.6) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Second stem cell transplant, n (%) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 4 (11.8) | 2 (9.6) | |

| No | 30 (88.2) | 19 (90.5) | |

| Relapse, n (%) | 0.25 | ||

| Yes | 15 (44.1) | 6 (28.6) | |

| No | 19 (55.9) | 15 (71.4) | |

| Death, n (%) | 0.06 | ||

| Yes | 15 (44.1) | 4 (19.0) | |

| No | 19 (55.9) | 17 (81.0) | |

RBC red blood cells, aGVHD acute graft-versus-host disease, cGVHD chronic graft-versus-host disease, CMV cytomegalovirus

*Two patients in the cryopreserved group were excluded from time to neutrophil engraftment: one patient who experienced primary graft failure and one patient who experienced early relapse (within one month of transplant).

**Four patients in the cryopreserved group did not achieve platelet engraftment and were excluded from time to platelet engraftment: one patient who experienced primary graft failure, one patient who experienced secondary graft failure, and two patients who experienced relapse.

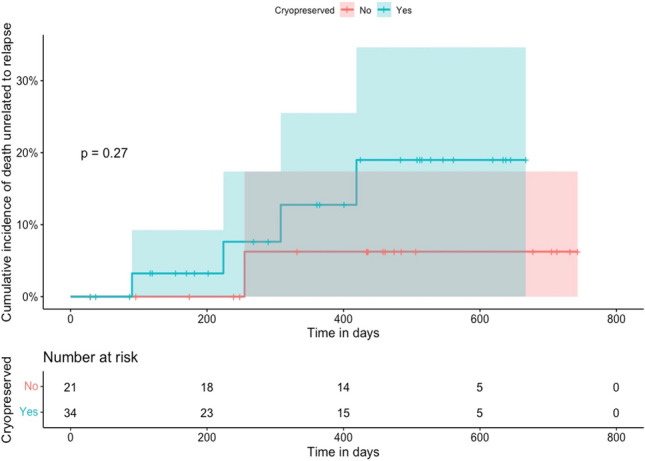

NRM

The cumulative incidence of NRM at 1-year was 12.8% in the cryopreserved allograft group and 6.3% in the fresh allograft group, which did not reach statistical significance [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.94 with 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.29–34.18, p = 0.35] (Fig. 2). In the cryopreserved allograft group, three patients died from infection and one died from cardiac arrest, while both patients in the fresh allograft group died from infection. The incidence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation by day + 100 was not significantly different between the two groups (p = 0.46).

Fig. 2.

Non-relapse mortality (NRM)

Overall and relapse-free survivals

With a median follow-up of 15 months for the entire cohort, there was a statistically significant difference in OS favoring the fresh allograft recipients (p = 0.02) (Fig. 3a). The effect of cryopreservation remained significant after multivariate adjustment for age, disease status at time of transplant, moderate to severe cGVHD and CMV infection by day 100 (HR 2.27 with 95% CI 1.23–16.51, p = 0.02). By day + 100, 94.1 and 100% of patients were alive, while at 1-year post-transplant, 67.6% and 90.4% of patients were alive in the cryopreserved and fresh allograft groups, respectively.

Fig. 3.

a Overall survival; b Relapse-free survival

No significant difference in RFS was noted (p = 0.11, Fig. 3b; after multivariate adjustment, HR 1.61 with 95% CI 0.84–6.07, p = 0.11). During the study period, relapse occurred in 15 patients (44.1%) who received cryopreserved cells with a median time to relapse of 5-months (range: 1–12), while six patients (28.6%) in the fresh group relapsed with a median time to relapse of 7-months (range: 1–11). By the censor date, 11 patients had died from relapse in the cryopreserved allograft group, while two patients receiving fresh allografts died due to relapse. Although the cumulative incidence of relapse was higher in the cryopreserved allograft group, this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.25, Table 5).

Discussion

Cryopreservation of PBSC is not a common practice in allogenic transplantation apart from umbilical cord blood transplantation [11], and concerns regarding cryopreserved products adversely affecting cell viability and effector cell function has been the main reason for performing fresh allograft infusions in these patients [14].

We retrospectively assessed the impact of cryopreservation on patient outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic in the year 2020. Our findings suggested that cryopreservation was associated with a negative impact on allogeneic PBSC transplant. We observed a longer time to neutrophil engraftment and a significantly longer time to platelet engraftment. While some studies have suggested no difference in either neutrophil or platelet engraftment between cryopreserved and fresh allografts [2–10], our findings are supported by others who have shown outcomes consistent with our observations. A large retrospective study conducted by Hsu et al. analyzed outcomes from 1051 frozen PBSC allografts derived from related donors and another 678 allografts derived from matched-unrelated donors [5]. This study showed delayed platelet engraftment in cryopreserved-related donor PBSC grafts and delayed engraftment of both neutrophils and platelets in cryopreserved unrelated donor PBSC grafts. Dagdas et al. also showed longer neutrophil engraftment kinetics using frozen products [11].

Two graft failures were observed in the cryopreserved group while none were observed in the fresh group. Importantly, poor graft function occurred in 44.1% of cryopreserved allografts as compared to 28.6% of fresh allografts. Twice as many cryopreserved recipients required prolonged RBC transfusions after day + 60 (67.6 vs. 28.6%, respectively). Additionally, more cryopreserved recipients required DLI than recipients of fresh stem cells. Consistent with our data, Lioznov et al. observed more graft failures in cryopreserved allograft recipients compared to fresh allograft recipients (27 vs 1.4%, respectively) [13].

With a median follow-up of 15 months, a significant decrease in OS was noted in the cryopreserved group compared with the fresh group, while NRM and RFS did not reach statistical significance. Hsu et al. found minimal impact of cryopreservation in related PBSC allografts in terms of NRM, relapse, OS and RFS, but noted increased relapse as well as decreased RFS and OS in cryopreserved unrelated PBSC allografts [5]. The authors suspected a potentially longer transit time of unrelated donor grafts prior to cryopreservation, the decline in post-thaw colony forming units, and other patient-related reasons for cryopreservation may have played a role in the worse outcomes noted in their study [5]. In our study, although the cryopreserved cells had a slightly lower number of CD34+ cell infused, as expected due to the freeze-thawing process, this cannot explain our findings. Prior data have shown that the minimum acceptable dose of CD34+ cells for successful transplantation is above 2.0 × 106 cells/kg [19]. Even though all of our post-thawed products met this criteria, the transplant outcomes differed significantly between the cryopreserved and fresh groups, suggesting in cryopreserved allografts, other factors besides CD34+ cell dose may play a role. The cryo-protective agent used in the cryopreservation process could result in adverse reactions and potentially have a negative impact on survival outcomes [20]. It is important to note that all patients in our study received post-transplant cyclophosphamide as part of GVHD prophylaxis. As mentioned above, Linzov et al., demonstrated that graft failures in the cryopreserved cohort appeared to occur more commonly in patients who received allografts with low aldehyde dehydrogenase bright CD34+ cells [13]. Given the effect of aldehyde dehydrogenase on the metabolism of cyclophosphamide, it is plausible that a combination of cryopreservation and post-transplant cyclophosphamide may adversely affect engraftment. Further investigation is needed to test this hypothesis.

Published data for the incidence of aGVHD in cryopreserved allo-HSCT are conflicting. Parody et al. reported a higher incidence and earlier onset of aGVHD in patients receiving cryopreserved PBSC while the difference in the incidence of cGVHD was not significant [12]. Medd et al. reported comparable incidence of aGVHD but a non-significant increase in extensive cGVHD in the cryopreserved PBSC group [14]. Alotaibi et al. reported no difference in grade II-IV aGVHD between cryopreserved versus fresh allografts, but did note a higher incidence of moderate/severe cGVHD in the cryopreserved group [2]. Our study demonstrated no statistically significant differences in grade II-IV aGVHD or cGVHD.

While our study population was relatively homogenous and the rational for cryopreservation was predominantly due to the impact of COVID-19, as opposed to heterogenous reasons requiring cryopreservation, there are several limitations to our work. Our study is limited by its retrospective nature, small sample size, and relatively short duration of follow-up. Additionally, the use of post-transplant cyclophosphamide prevents us from generalizing our conclusions to other GVHD prophylaxis regimens.

In summary, our study showed decreased OS, delayed engraftment, and a higher need for DLI and RBC transfusions in patients undergoing cryopreserved PBSC allo-HSCT with post-transplant cyclophosphamide. We suggest cryopreserved allogeneic transplantation to be performed with caution. Further prospective studies are required to further investigate the impact of cryopreservation in allogeneic PBSC transplantation.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

MG: data collection, methodology, investigation, writing, review. JL: data collection, methodology, investigation, writing, review. PC: data collection, methodology, investigation, writing, review. SA: writing, review. RDP: writing, review. SM: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing, review and editing.

Data availability statement

The data us accurate and available upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wiercinska E, Schlipfenbacher V, Bug G, Bader P, Verbeek M, Seifried E, et al. Allogeneic transplant procurement in the times of COVID-19: quality report from the central European cryopreservation site. J Transl Med. 2021;19:145. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-02810-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alotaibi AS, Prem S, Chen S, Lipton JH, Kim DD, Viswabandya A, et al. Fresh vs. frozen allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell grafts: A successful timely option. Am J Hematol. 2021;96:179–87. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim DH, Jamal N, Saragosa R, Loach D, Wright J, Gupta V, et al. Similar outcomes of cryopreserved allogeneic peripheral stem cell transplants (PBSCT) compared to fresh allografts. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:1233–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devine SM. Transplantation of allogeneic cryopreserved hematopoietic cell grafts during the COVID-19 pandemic: a National Marrow Donor Program perspective. Am J Hematol. 2021;96:169–171. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu JW, Farhadfar N, Murthy H, Logan BR, Bo-Subait S, Frey N, et al. The effect of donor graft cryopreservation on allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation outcomes: a center for international blood and marrow transplant research analysis. Implications during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transplant Cell Ther. 2021;27:507–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2021.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamadani M, Zhang MJ, Tang XY, Fei M, Brunstein C, Chhabra S, et al. Graft cryopreservation does not impact overall survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26:1312–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valentini CG, Chiusolo P, Bianchi M, Metafuni E, Orlando N, Giammarco S, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A single center reappraisal. Cytotherapy. 2021;23:635–640. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2020.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacob RP, Flynn J, Devlin SM, Maloy M, Giralt SA, Maslak P, et al. Universal engraftment after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation using cryopreserved CD34-selected grafts. Transplant Cell Ther. 2021;27:697–e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2021.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandez-Sojo J, Azqueta C, Valdivia E, Martorell L, Medina-Boronat L, Martínez-Llonch N, et al. Cryopreservation of unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cells: The right answer for transplantations during the COVID-19 pandemic? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021;56:2489–96. doi: 10.1038/s41409-021-01367-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eapen M, Zhang MJ, Tang XY, Lee SJ, Fei MW, Wang HL, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation with cryopreserved grafts for severe aplastic anemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26:e161–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dagdas S, Ucar MA, Ceran F, Gunes AK, Falay M, Ozet G. Comparison of allogenic stem cell transplantations performed with frozen or fresh stem cell products with regard to GVHD and mortality. Transfus Apher Sci. 2020;59:102742. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2020.102742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parody R, Caballero D, Márquez-Malaver FJ, Vázquez L, Saldaña R, Madrigal MD, et al. To freeze or not to freeze peripheral blood stem cells prior to allogeneic transplantation from matched related donors. Eur J Haematol. 2013;91:448–55. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lioznov M, Dellbrügger C, Sputtek A, Fehse B, Kröger N, Zander AR. Transportation and cryopreservation may impair haematopoietic stem cell function and engraftment of allogeneic PBSCs, but not BM. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42:121–8. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medd P, Nagra S, Hollyman D, Craddock C, Malladi R. Cryopreservation of allogeneic PBSC from related and unrelated donors is associated with delayed platelet engraftment but has no impact on survival. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:243–8. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP). Response to COVID-19: Up-to- date information for all Network partners on coronavirus impacts. Available at: https://network.bethematchclinical.org/news/nmdp/be-the-match-response-to-covid-19/. Accessed Oct 1, 2020

- 16.Valcárcel D, Sureda A. Graft failure. In: Carreras E, Dufour C, Mohty M, Kröger N, editors. The EBMT handbook hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and cellular therapies. 7. Cham: Springer; 2019. pp. 307–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, Thomas ED. 1994 consensus conference on acute GVHD grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15(6):825–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alessandrino EP, Bernasconi P, Caldera D, Colombo A, Bonfichi M, Malcovati L, et al. Adverse events occurring during bone marrow or peripheral blood progenitor cell infusion: analysis of 126 cases. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23:533–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singhal S, Powles R, Treleaven J, Kulkarni S, Sirohi B, Horton C, et al. A low CD34+ cell dose results in higher mortality and poorer survival after blood or marrow stem cell transplantation from HLA-identical siblings: should 2×106 CD34+ cells/kg be considered the minimum threshold? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26:489–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shu Z, Heimfeld S, Gao D. Hematopoietic SCT with cryopreserved grafts: Adverse reactions after transplantation and cryoprotectant removal before infusion. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:469–76. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data us accurate and available upon request.