Take Home Message

The Prostate Health Index test had high diagnostic accuracy for the detection of clinically significant prostate cancer. Its incorporation in the diagnostic process could reduce the necessary biopsies. There is a lack of evidence on the effect of this test on clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Prostatic neoplasms, Molecular markers, Clinically significant cancer, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Abstract

Context

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most common type of cancer in men. Individualized risk stratification is crucial to adjust decision-making. A variety of molecular biomarkers have been developed in order to identify patients at risk of clinically significant PCa (csPCa) defined by the most common PCa risk stratification systems.

Objective

The present study aims to examine the effectiveness (diagnostic accuracy) of blood or urine-based PCa biomarkers to identify patients at high risk of csPCa.

Evidence acquisition

A systematic review of the literature was conducted. Medline and EMBASE were searched from inception to March 2021. Randomized or nonrandomized clinical trials, and cohort and case-control studies were eligible for inclusion. Risk of bias was assessed using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool. Pooled estimates of sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve were obtained.

Evidence synthesis

Sixty-five studies (N = 34 287) were included. Not all studies included prostate-specific antigen-selected patients. The pooled data showed that the Prostate Health Index (PHI), with any cutoff point between 15 and 30, had sensitivity of 0.95–1.00 and specificity of 0.14–0.33 for csPCa detection. The pooled estimates for SelectMDx test sensitivity and specificity were 0.84 and 0.49, respectively.

Conclusions

The PHI test has a high diagnostic accuracy rate for csPCa detection, and its incorporation in the diagnostic process could reduce unnecessary biopsies. However, there is a lack of evidence on patient-important outcomes and thus more research is needed.

Patient summary

It has been possible to verify that the application of biomarkers could help detect prostate cancer (PCa) patients with a higher risk of poorer evolution. The Prostate Health Index shows an ability to identify 95–100 for every 100 patients suffering from clinically significant PCa who take the test, preventing unnecessary biopsies in 14–33% of men without PCa or insignificant PCa.

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is a major health problem, with approximately 1.4 million cases diagnosed worldwide each year [1]. It is the second most common cancer in males after lung cancer worldwide [2], and its prevalence increases with each additional year of age [3]. The mean age of PCa onset is 65 yr and the majority of PCa patients are diagnosed from then onwards, with the age group of 70–75 yr having the highest incidence rate [4].

PCa often progresses slowly and has a prolonged preclinical phase. Therefore, many men with PCa die from causes other than PCa and without evidence of pathological manifestation [3].

Traditionally, diagnosis and staging of PCa have been based on prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, digital rectal examination (DRE), and transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy.

Serum PSA measurement is the reference standard for the early detection of PCa. However, PSA level does not exclusively increase in malignant pathology, as high levels can also be observed in benign prostatic pathologies such as benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatitis, other urinary tract infections, and even acute urine retention. Moreover, PSA cannot discriminate between indolent PCa (iPCa) and aggressive tumors.

Most men with positive screening results (elevated PSA levels or abnormal DRE) who undergo prostate biopsy will not have PCa. Approximately two-thirds of men with an elevated PSA level can expect a false positive test result [5]. Moreover, biopsy procedures are related to complications such as pain, bleeding, and sepsis, and the related consequences on the utilization of health resources. However, the most serious harm of PCa screening may be overdiagnosis, which may result in subsequent overtreatment [6]. Consequently, strategies to differentiate iPCa from aggressive tumors are necessary [1]. Current European Urological Association guidelines recommend the use of risk stratification tools, such as risk calculators and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and biomarker tests for the prediction of a positive prostate biopsy as reflex tests after an elevated PSA level [7].

Recently, there has been an expansion in the availability of new molecular blood and urine test biomarkers that can be used to support prostate biopsy decisions, providing more individualized risks for PCa, distinguishing between clinically significant PCa (csPCa) and iPCa, or predicting the prognosis of patients already diagnosed [8]. However, no consensus has been reached on the use of these tests in routine clinical practice.

The objective of the present study is to examine the diagnostic accuracy of the biomarker tests in the identification of patients with csPCa.

2. Evidence acquisition

A systematic review (SR) of the literature was carried out following the Cochrane Collaboration methodology [9] with reporting in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [10]. The prespecified protocol for this review was registered in PROSPERO (registration number CRD42021240638).

2.1. Data sources and searches

The following electronic databases were searched (from 2010 to March 1, 2021): Medline (Ovid platform) and EMBASE (Elsevier interface). The search strategy included both controlled vocabulary and text-word terms related to PCa and molecular biomarker. Searches were limited to the English and Spanish languages. The complete search strategy is available in Supplementary Table 1. We also examined the reference lists of included articles and, through search in Google Scholar, articles that referenced the included studies.

2.2. Selection criteria and study selection

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they fulfilled the following criteria:

-

1.

Design: randomized or nonrandomized clinical trials (RCTs or non-RCTs) were eligible for inclusion. In the absence of such designs, cohort and case-control studies that performed an evaluation of the diagnostic validity of the tests were considered.

-

2.

Population: adult men (≥18 yr) with clinical factors that suggested csPCa comprised the study population. Studies with a heterogeneous group of patients (eg, patients with suspected PCa, either iPCa or csPCa) were included only if the results for patients meeting the inclusion criteria were reported separately.

-

3.

Index tests: any blood or urine test based on biomarkers aimed at distinguishing csPCa from iPCa was performed.

-

4.

Reference standard: it included alternative tests, biopsy, magnetic resonance, or usual care.

-

5.

Target conditions: csPCa (Gleason score ≥7, International Society of Urological Pathology ≥2, and intermediate- or high-risk localized PCa using the D'Amico Classification System for PCa or according to the European Association of Urology).

-

6.

Outcomes: studies that reported any of the following outcome measures were included: cancer-specific survival, metastasis, change in treatment decisions, and adverse effects. In diagnostic performance studies, measures of sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve (AUC) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were also included, if available.

-

7.

Language: only studies published in English or Spanish were included.

-

8.

Publication type: only full original publications were considered.

-

9.

Date of publication: due to the fact that biomarker-based tests have emerged in the last decade, only studies published from 2010 were considered.

Two reviewers (D.I.-V. and A.A.C.) screened retrieved references independently and in duplicate, starting with titles and abstracts. The full texts of all articles deemed potentially relevant were then screened to confirm eligibility. Disagreements between the reviewers were checked by a third reviewer (T.P.-S.).

2.3. Data extraction process and risk of bias assessment

Data extraction and risk of bias (RoB) assessment were also conducted independently and in duplicate. Discrepancies were discussed and, when no consensus was reached, a third reviewer was consulted. Data extracted include general information, study design, sample characteristics, test details (biomarker and cutoff point), reference standard, and results.

RoB was assessed using either the Cochrane Risk of Bias tools for RCT (RoB 2.0) [11], or the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) revised tool [12].

2.4. Assessment of publication bias

Potential publication bias was explored by constructing the Deeks asymmetry graphs and computing the Egger test [13], with the significance level set at 0.05, using metafunnel and metabias commands, respectively, in STATA version 16.

2.5. Data synthesis

We built 2 × 2 tables summarizing true positive (TP), false positive, true negative, and false negative (FN) values to calculate sensitivity and specificity for detecting csPCa. Review Manager (RevMan, version 5.4.1., 2020; The Nordic Cochrane Center, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used to show the sensitivity and specificity measurements at the study level. Pooled estimates with 95% CIs were performed by bivariant random-effect meta-analyses using the midas command in STATA version 16 [14]. A continuity correction was used in trials that reported zero cells in a 2 × 2 table (eg, when TP or FN is zero). Heterogeneity was assessed by visually analyzing forest plots and through the Higgins I2 statistic [15]. Several sources of heterogeneity were anticipated, including the type of diagnostic test, cutoff point, definition of csPCa, and ethnic origin. When reported in studies, the effect using a subgroup analysis was explored.

2.6. Certainty of evidence assessment

An assessment of the certainty of evidence per outcome was performed for tests included in the meta-analysis, based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. We developed evidence profiles and rated the overall certainty of evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low [16].

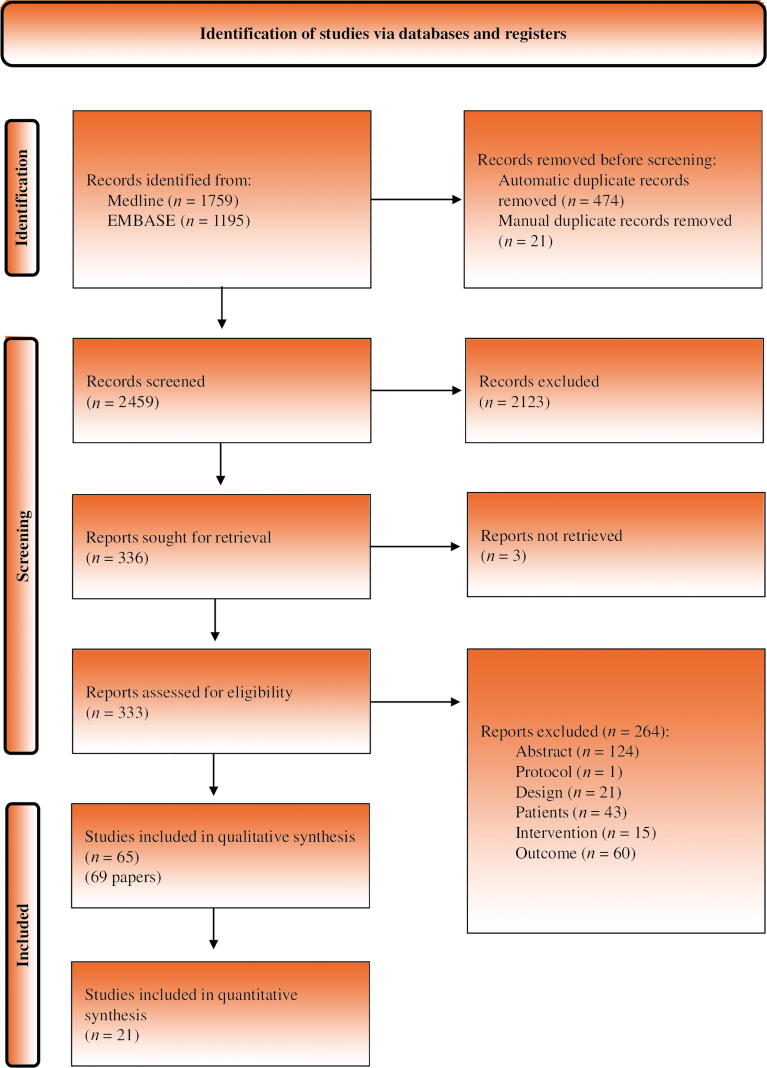

3. Evidence synthesis

The results of the literature search and study selection process are shown in Figure 1. Our search identified 2954 references, of which 336 studies were selected for full text assessment. Three of these could not be retrieved [17], [18], [19]. Sixty-five studies [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], reported in 69 articles [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], finally fulfilled the pre-established selection criteria. The list of studies excluded at the full-text level and the reasons for exclusion are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart detailing the screening process. PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses.

3.1. Characteristics of included studies

The main characteristics of the selected studies are summarized in Table 1, Table 2.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of included studies

| Study | Fundeda | Design | Biomarker | Test | Biopsy | Outcome |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | SE SP |

PPV NPV |

AUC | |||||

| Abrate (2015) [74] France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and UK |

Y | Nested case-control | PHI | Beckman Coulter | ≥12-cylinder TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Babajide (2021) [22] USA |

N | Case-control | PHI | Beckman Coulter | NR | Y | Y | Y |

| Barisiene (2020) [63] Lithuania |

Y | Prospective | PHI PHID |

Beckman Coulter | NR | Y | Y | Y |

| Bertok (2020) [32] Austria |

N | Retrospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | TRUS guided or systematic | N | N | Y |

| Boegemann (2016) [75] Germany and France |

N | Ambispective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | 8-cylinder TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Busetto (2020) [57] Italy |

N | Prospective | HOXC6 and DLX1 | SelectMDx | 10–12-cylinder TRUS guided | Y | Y | Y |

| Cao (2018) [23] USA |

N | Retrospective | PCA3 | Progensa PCA3 | 12 cylinder | Y | N | Y |

| Catalona (2011) [24] USA |

Y | Case-control | PHI | Beckman Coulter | ≥12 cylinder | Y | Y | Y |

| Chiu (2016) [43] China |

Y | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | ≥10 cylinder TRUS guided | N | Y | N |

| Chiu (2016) [54] China |

Y | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | ≥10 cylinder TRUS guided | N | Y | Y |

| Chiu (2019) [77] France, Germany, Singapore, China, and Taiwan |

Y | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | TRUS guided | Y | Y | N |

| Choi (2020) [61] South Korea |

NR | Retrospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | Transrectal or transperineal | Y | Y | N |

| De La Calle (2015) [25] USA |

N | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | TRUS guided | Y | Y | Y |

| Druskin (2018) [26] USA |

N | Retrospective | PHID | Beckman Coulter | TRUS guided | Y | Y | Y |

| Falagario (2021) [27] USA |

NR | Retrospective | Total PSA, free PSA, intact PSA, and HK2 | 4Kscore test | mpMRI fusion and 12-cylinder systematic | N | N | Y |

| Fan (2019) [73] Taiwan |

N | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | 12-cylinder bilateral TRUS guided | Y | Y | N |

| Filella (2014) [91] Spain |

N | Ambispective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | NR | N | N | Y |

| Foj (2020) [46] Spain |

N | Retrospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | 10-cylinder bilateral TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Foley (2016) [87] Ireland |

N | Retrospective analysis | PHI | Beckman Coulter | 12-cylinder TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Furuya (2017) [60] Japan |

NR | Retrospective | PHI + MRI | Beckman Coulter | ≥16-cylinder transperineal ultrasound guided | Y | Y | Y |

| Guazzoni (2011) [58] Italy |

Y | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | 10–12-cylinder TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Haese (2019) [78] The Netherlands, France, and Germany |

N | Retrospective | HOXC6 and DLX1 + mpMRI | SelectMDx | 10–12-cylinder TRUS guided | Y | Y | Y |

| Hansen (2013) [28] USA |

Y | Retrospective | PCA3 | Progensa PCA3 | ≥10-cylinder TRUS-TRUS guided | N | Y | Y |

| Hsieh (2020) [72] Taiwan |

N | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | 12-cylinder TRUS guided | Y | Y | Y |

| Kim (2020) [64] UK |

Y | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | Transrectal or transperineal | Y | Y | N |

| Kotova (2020) [66] Russia |

N | Prospective | PCA3 | NR | NR | Y | Y | Y |

| Lazzeri (2013) [92] Italy, Germany, France, Spain, and UK |

Y | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | ≥12-cylinder TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Lazzeri (2016) [80] Italy, France, Spain, Germany, and UK |

Y | Nested case-control | PHI | Beckman Coulter | ≥12-cylinder TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Leyten (2015) [53] The Netherlands |

Y | Retrospective | PCA3 | Progensa PCA3 | ≥10-cylinder TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Loeb (2015) [29] USA |

Y | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | ≥10 cylinder | Y | Y | N |

| Loeb (2017) [30] USA |

Y | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | ≥6 cylinder | Y | Y | Y |

| McKiernan (2016) [31] USA |

Y | Prospective | ERG and PCA3 | ExoDx Prostate IntelliScore urine exosome assay | NR | Y | Y | Y |

| Mearini (2014) [59] Italy |

NR | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| PHID | ||||||||

| Morote (2016) [47] Spain |

NR | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | ≥12-cylinder TRUS guided | Y | Y | Y |

| Mortezavi (2021) [70] Sweden |

N | Prospective | Clinical variables, total PSA, free PSA, HK2, MSMB, and HOXB13 | Stockholm3 test | TRUS guided and mpMRI fusion and/or 12-cylinder systematic | N | N | Y |

| Na (2014) [76] China |

Y | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | 10-cylinder TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Na (2017) [65] China |

N | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | 10–14-cylinder TRUS guided | Y | Y | N |

| Nordström (2015) [93] Sweden |

N | Case-control | PHI Total PSA, free PSA, intact PSA, and HK2 |

Beckman Coulter 4Kscore test |

10–12-cylinder TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Nordström (2021) [69] Sweden |

N | Retrospective analysis | Clinical variables, total PSA, free PSA, HK2, MSMB, HOXB13, and PHID | Stockholm3 test | 10–12 cylinder | N | N | Y |

| Nygård (2016) [95] Norway |

N | Prospective | PCA3 | Progensa PCA3 | Extended 10 cylinder | Y | Y | Y |

| O'Malley (2017) [33] USA |

N | Prospective | PCA3 TMPRSS2 and ERG |

Progensa PCA3 TMPRSS2:ERG |

TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Park (2018) [62] South Korea |

N | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Punnen (2018) [34] USA |

Y | Prospective | Total PSA, free PSA, intact PSA, and HK2 | 4Kscore test | ≥10-cylinder TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Roumiguié (2020) [49] France |

N | Retrospective | HOXC6 and DLX1 | SelectMDx | TRUS guided and mpMRI fusion | Y | Y | Y |

| Ruffion (2013) [50] France |

NR | Prospective | PCA3 | Progensa PCA3 | TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Ruffion (2014) [51] France |

NR | Prospective | PCA3 | Progensa PCA3 | TRUS guided | Y | Y | N |

| Sanchís-Bonet (2018) [48] Spain |

N | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | NR | N | N | Y |

| Sanda (2017) [35] USA |

Y | Retrospective | PCA3 | Progensa PCA3 | 12-cylinder TRUS guided | Y | Y | N |

| Schulze (2020) [20] Germany |

N | Prospective | PHI PHID |

Beckman Coulter | 10–14 cylinder | Y | Y | N |

| Seisen (2015) [52] France |

Y | Prospective | PHI PCA3 |

Beckman Coulter Progensa PCA3 |

≥12-cylinder TRUS guided | Y | Y | Y |

| Shore (2019) [36] USA |

N | Retrospective | HOXC6 and DLX1 | SelectMDx | 10–12-cylinder TRUS guided or mpMRI fusion | Y | N | N |

| Steuber (2022) [21] Germany |

Y | Prospective | Thrombospondin-1, cathepsin D, total PSA, free PSA, and patient age | Proclarix test | 10–12-cylinder TRUS guided and mpMRI fusion | Y | Y | N |

| Tan (2017) [67] Singapore |

N | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | ≥12-cylinder TRUS guided | Y | Y | Y |

| Tomlins (2016) [37] USA |

Y | Prospective | PCA3, T2:ERG, and serum PSA level TMPRSS2 and ERG |

MyProstateScore TMPRSS2:ERG |

TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Tosoian (2017) [94] USA |

N | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | NR | N | N | Y |

| Tosoian (2017) [38] USA |

N | Prospective | PHI PHID |

Beckman Coulter | NR | Y | Y | Y |

| Tosoian (2021) [40] USA |

N | Prospective | PCA3 PCA3, TMPRSS2, and serum PSA level | MyProstateScore | TRUS guided | Y | Y | N |

| Van Neste (2016) [55] The Netherlands |

Prospective | PCA3 | Prototype kit | 10-cylinder TRUS guided | N | N | Y | |

| Wang (2017) [82] China |

N | Prospective | PCA3 | Progensa PCA3 | 10–12-cylinder TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Wei (2014) [41] USA |

Y | Prospective | PCA3 | Progensa PCA3 | TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Woo (2020) [81] USA and Spain |

N | Prospective | PCA3 PCA3 and T2:ERG |

NR | NR | N | N | Y |

| Wu (2019) [89] China |

N | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | NR | N | N | Y |

| Wysock (2020) [42] USA |

NR | Prospective | Total PSA, free PSA, intact PSA, and HK2 HOXC6 and DLX1 |

4Kscore test SelectMDx |

TRUS guided and mpMRI fusion and/or 12-cylinder systematic | Y | Y | Y |

| Yu (2016) [83] China |

Y | Prospective | PHI | Beckman Coulter | 10-cylinder TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

| Zappala (2017) [44] USA |

NR | Prospective | Total PSA, free PSA, intact PSA, and HK2 | 4Kscore test | ≥10-cylinder TRUS guided | N | N | Y |

AUC = area under the curve; DLX1 = distal-less homeobox 1; HK2 = human kallikrein 2; HOXC6 = homeobox C6; HOXC13 = homeobox C13; mpMRI = multiparametric MRI; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; MSMB = microseminoprotein beta; N = no; NPV = negative predictive value; NR = not reported; PCA3 = prostate cancer antigen 3; PHI = Prostate Health Index; PHID = PHI density; PPV = positive predictive value; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; SE = sensitivity; SP = specificity; TRUS = transrectal ultrasound; Y = yes.

Funded by industry.

Table 2.

Selection criteria and clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of the participants in the included studies

| Study | N | N PCa | Clinically significant PCa |

Age |

Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Ethnicity (%) | PSA (ng/ml) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Definition | Mean/median | SD/IQR | Range | |||||||

| Abrate (2015) [74] | 142 | 65 | 44 | Gleason ≥7 | 65.40 | 7.52a | NR | 1. >45 yr 2. With or without suspect DRE 3. Obese (BMI ≥30) |

1. Bacterial prostatitis (3 mo prior) or undergoing previous transurethral endoscopic surgery 2. Chronic renal failure, marked alterations in blood proteins (normal plasma range 6–8 g/dl), hemophiliacs, or those who previously received multiple transfusions |

NR | 6.80 (4.40–10.10)b |

| Babajide (2021) [22] | 293 | 158 | 52 | ISUP grade ≥2 | NR | NR | 40–79 | NR | 1. Background of PCa 2. Treated with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors 3. Suspicious DRE 4. PSA >10.00 ng/ml 5. Previous prostate biopsy |

African Americans (100) | NR |

| Barisiene (2020) [63] | 210 | 112 | 40 81 |

ISUP grade ≥2 Epstein classification |

63 | 7.09 | NR | 1. >50 yr 2. Elevated PSA (2.50–10.00 ng/ml) 3. Negative DRE |

1. Background of PCa 2. History of endoscopic or open prostate surgery 3. Previous prostate biopsy (3 mo) 4. Treated with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (previous 3 mo) 5. Acute prostatitis or UTI |

NR | 4.32 ± 1.85c |

| Bertok (2020) [32] | 140 | 70 | 42 | Gleason ≥7 | 62.15 | NR | NR | 1. Elevated PSA 2. TRUS-guided prostate biopsy |

NR | NR | 2.00–10.00d |

| Boegemann (2016) [75] | 769 | 347 | 111 | Gleason ≥7 | 59 | NR | 39–65 | 1. Elevated PSA (1.60–8.00 ng/ml) 2. With or without suspect DRE |

1. Acute or chronic prostatitis 2. UTI 3. Treated with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (previous 6 mo) 4. Background of PCa |

NR | 4.60 (4.40–4.71)b |

| Busetto (2020) [57] | 52 | 17 | 7 | ISUP grade ≥2 | 64 | 8.70 | 44–79 | 1. Timed to biopsy by elevated PSA (>3 ng/ml) or suspicious DRE | 1. Background of PCa or another neoplasm under active treatment 2. Medical treatment known to affect serum PSA levels and the prostate gland 3. Invasive treatment for BPH 4. Previous prostate biopsy |

NR | 6.80 ± 3.90 (1.00–19.90)e |

| Cao (2018) [23] | 271 | 77 | 52 | Gleason ≥7 | 63 | NR | 59–68 | NR | 1. Biopsy results not available | African Americans (14.4) | NR |

| Catalona (2011) [24] | 892 | 430 | 139 | Gleason ≥7 | 62.80 | 7.00 | 50–84 | 1. No history of PCa 2. Negative DRE 3. Elevated PSA (1.50–11.00 ng/ml) 4. Prostate biopsy of ≥6 casts within 6 mo after blood collection |

1. PSA outside 2.00–10.00 ng/ml 2. Medical treatment known to affect serum PSA levels 3. Previous interventions such as transurethral resection of the prostate 4. Acute prostatitis 5. UTI 6. Blood collection or biopsy at inappropriate time interval 7. Previous androgen replacement therapy |

Caucasians (81) African Americans (5) Other ethnicities (4) Unknown (10) |

5.40 ± 1.90 (2.00–10.00)e |

| Chiu (2016) [43] | 312 | 53 | 24 | Gleason ≥7 | 68.10 | 6.20 | 51–82 | 1. Elevated PSA (10.00–20.00 ng/ml) and negative DRE 2. TRUS-guided prostate biopsy and prospective blood sample collection |

NR | Asians | 13.27 ± 2.71 (9.95–20.01)e |

| Chiu (2016) [54] | 569 | 62 | 16 | Gleason ≥7 | 66 | NR | 61–71 | 1. Elevated PSA (4.00–10.00 ng/ml) and negative DRE 2. With or without lower urinary tract symptoms 3. Before the prostate biopsy |

1. Background of PCa 2. Any suspicious rectal finding 3. Withdrawal therapy or 5-alpha reductase inhibitors |

Asians | 6.73 (5.64–8.03)b |

| Chiu (2019) [77] | 503 1149 |

262 151 |

115 66 |

Gleason ≥7 Gleason ≥7 |

63 65 |

NR NR |

58–68 61–71 |

1. TRUS-guided prostate biopsy from 10 to 12 cylinders 2. Elevated PSA (2.00–20.00 ng/ml) |

NR | Caucasians Asians |

2.00–10.00d 2.00–10.00d |

| Choi (2020) [61] | 114 | 37 | 28 | Gleason ≥7 | 62.81a | 7.87 a | NR | 1. Biopsied with previous PSA and PHI 2. Elevated PSA (2.50–10.00 ng/ml) |

NR | NR | NR |

| De La Calle (2015) [25] | 561 | 233 | 114 | Gleason ≥7 | 62.10 | 8.30 | 38–87 | 1. Biopsy and blood draw completed | 1. Background of PCa 2. Positive previous prostate biopsy |

Caucasians (85.2) African Americans (10.2) Hispanic (4.5) Other ethnicities (2.7) |

6.50 ± 12.20 (0.30–232.80)e |

| 395 | 205 | 122 | Gleason ≥7 | 62.80 | 8.60 | 33–85 | Caucasians (87.8) Afro-Americans (8.4) Hispanic (3.8) Other ethnicities (5.8) |

5.90 ± 10.90 (0.30–208.80)e | |||

| Druskin (2018) [26] | 241 | NR | 91 | ISUP grade1 detected on >2 cylinders or >50% of any core ISUP grade ≥2 |

65 | NR | 59.3–70.8 | 1. Elevated PSA (<10.00 ng/ml) and negative DRE | 1. Suspicious DRE | African Americans (11.6) | 7.00 (4.90–10.20)b |

| 71 | ISUP grade ≥2 | ||||||||||

| 38 | ISUP grade ≥3 | ||||||||||

| Falagario (2021) [27] | 256 | 153 | 94 | ISUP grade ≥2 | 66 | NR | 60–70.9 | NR | NR | NR | 5.90 (4.20–8.50)b |

| Fan (2019) [73] | 307 | 95 | 52 | Gleason ≥7 | 66 | NR | 57.67–74.33 | 1. Timed to biopsy by PSA 4.00–10.00 ng/ml with or without a suspicious DRE or PSA <4 ng/ml and a suspicious DRE | 1. Acute prostatitis or UTI 2.Treated with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (previous 3 mo) 3. Previous prostate biopsy 4. Previous transurethral resection of the prostate |

Asians | 4.00–10.00d |

| Filella (2014) [91] | 354 | 175 | 80 | Gleason ≥7 | 68 | NR | 38–88 | 1. Elevated PSA or suspicious DRE | 1. Medical treatment known to affect serum PSA levels 2. Acute prostatitis or UTI 3. Invasive treatment for BPH |

NR (Spanish) | 6.17 (1.92–36.90)b |

| Foj (2020) [46] | 276 | 151 | 80 | D’Amico classification: intermediate and high risk | 66.65 | 7.29 | NR | 1. Timed to biopsy by elevated PSA or suspicious DRE | 1. Medical treatment known to affect serum PSA levels 2. Chronic kidney failure 3. Acute prostatitis or UTI 4. Invasive treatment for BPH |

NR (Spanish) | 6.14 (0.50–36.90)b |

| Foley (2016) [87] | 250 | 112 | 77 | Gleason ≥7 | 63.87 | NR | NR | 1. Availability of a biobank serum sample prior to biopsy | 1. <40 yr 2. Background of PCa |

NR | 6.40 (0.50–1400.00)b |

| Furuya (2017) [60] | 50 | 33 | 21 | Gleason ≥7 | 68.50 | NR | 53–82 | 1. Elevated PSA (2.00–10.0 ng/ml) 2. MRI before biopsy |

1. Bacterial prostatitis (previous 3 mo) 2. Previous endoscopic prostate surgery 3. Treated with 5-alpha inhibitors, antiandrogens, or luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogs |

NR | 6.92 ± 1.69 (3.74–9.96)e |

| Guazzoni (2011) [58] | 268 | 107 | 52 | Gleason ≥7 | 63.30 | 8.20 | NR | 1. Elevated PSA (2.00–10.00 ng/ml) 2. Negative DRE 3. Informed consent |

1. Acute or chronic bacterial prostatitis (previous 3 mo) 2. Invasive treatment for BPH 3. Medical treatment known to affect serum PSA levels |

NR | 5.70 (2.00–9.90)b |

| Haese (2019) [78] | 1039 916 |

521 467 |

282 258 |

ISUP grade ≥2 | 64 65 |

NR NR |

59–69 60–70 |

NR | 1. Background of PCa 2. Medical treatment known to affect serum PSA levels (previous 6 mo) 3. Invasive treatment for BPH (previous 6 months) |

NR | 6.20 (4.60–9.40)b 6.40 (4.50–9.20)b |

| Hansen (2013) [28] | 692 | 318 | 137 | Gleason ≥7 | 64 | NR | 58–69 | 1. Suspicious DRE 2. 10-cylinder prostate biopsy 3. Elevated PSA (2.50–10.00 ng/ml) 4. Informed consent |

1. UTI 2. Medical treatment known to affect serum PSA levels 3. Background of PCa 4. Invasive treatment for BPH 5. Lack of information on prostate volume |

NR | 5.20 (4.30–7.20)b |

| Hsieh (2020) [72] | 102 | 39 | 24 | Grade group ≥2 | 65.50 | NR | 60–70 | 1. >40 yr 2. Scheduled to biopsy for suspected PCa due to elevated PSA (PSA >4.00 ng/ml) and/or suspicious DRE |

1. Background of PCa 2. Bacterial prostatitis (previous 3 mo) 3. Treated with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors 4. Inability or unwillingness to sign the informed consent |

Asians | 7.78 (6.12–11.80)b |

| Kim (2020) [64] | 545 | 349 | 258 174 |

ISUP grade ≥2 ISUP grade ≥3 |

NR | NR | NR | Elevated PSA | 1. Previous prostate biopsy 2. Pelvic metal interfering with mpMRI quality 3. No biopsy was performed after mpMRI |

NR | 8.00 (6.00–13.00)b |

| Kotova (2020) [66] | 128 | 61 | 33 | Gleason ≥7 | 66 | NR | 44–88 | 1. Elevated PSA (≥2.00 ng/ml) 2. 40–90 yr |

1. Previous treatment with antiandrogens 2. Bladder catheterization/cystostomy |

NR | 8 (2.06–76.80)b |

| Lazzeri (2013) [92] | 646 | 264 | 139 | Gleason ≥7 | 64.20 | 7.50 | NR | 1. >45 yr 2. Suspicious DRE 3. Elevated PSA (2.00–10.00 ng/ml) |

1. Bacterial prostatitis (previous 3 mo) 2. Previous endoscopic surgery 3. Previous prostate biopsy 4. Treated with dutasteride or finasteride 5. Chronic renal failure, marked abnormalities in blood proteins (normal plasma range 6–8 g/dl), hemophiliacs, or those who previously received multiple transfusions |

Caucasians (96) | 5.80 (4.30–7.70)b |

| Lazzeri (2016) [80] | 262 | 136 | 106 | Gleason ≥7 | 67.30 | 8.10 | NR | 1. >45 yr 2. PSA 4.00–10.00 ng/ml 3. With or without suspect DRE 4. With or without previous negative biopsy |

1. Bacterial prostatitis 2. Previous prostate endoscopic surgery 3. Treated with dutasteride or finasteride 4. Chronic renal failure 5. Marked alterations in blood proteins (normal plasma range: 6–8 g/d), hemophiliacs, or with multiple previous transfusions |

NR | 15.30 (11.90–22.50)b |

| Leyten (2015) [53] | 358 | 157 | 93 | Gleason ≥7 | 65 | NR | 44–86 | NR | 1. Background of PCa 2. Medical treatment known to affect serum PSA levels (previous 6 mo) 3. Prostate biopsies (previous 3 mo) 4. Invasive treatment for BPH (previous 6 mo) |

NR | NR |

| Loeb (2015) [29] | 658 | 324 | 160 109 |

Epstein classification Gleason ≥7 |

63 | NR | 50–84 | 1. >50 yr 2. PSA 2.00–10.00 ng/ml 3. Negative DRE |

NR | Caucasians (81.2) African Americans (5.3) Other ethnicities (13.5) |

NR |

| Loeb (2017) [30] | 728 | 334 | 118 | Gleason ≥7 | 62.80 | 6.90 | NR | 1. Elevated PSA (2.00–10.00 ng/ml) and negative DRE 2. Prostate biopsy with ≥6 casts <6 mo after blood collection |

1. Prostate surgery 2. UTI 3. Medical treatment known to affect serum PSA levels (eg, 5-alpha reductase inhibitors) |

Caucasians (83) African Americans (5) Other ethnicities (12) |

5.40 ± 1.90 (2.00–1000)e |

| McKiernan (2016) [31] | 255 | 120 | 78 | Gleason ≥7 | 62 | NR | 50–79 | 1. >50 yr 2. Timed to biopsy (initial or repeated) by elevated PSA (2.00–20.00 ng/ml) or suspicious DRE |

1. Invasive treatment for BPH (previous 6 mo) 2. Medical treatment known to affect serum PSA levels (previous 3–6 mo) |

Caucasians (70) African Americans (19) Hispanic (6) Asians (2) Other ethnicities (2) |

4.95 (2.00–10.00)b |

| 519 | 250 | 148 | 63 | NR | 50–90 | 1. History of invasive treatment for benign prostate disease in the previous 6 mo 2. Medical treatment known to affect serum PSA levels (previous 3–6 mo) |

Caucasians (74) African Americans (17) Hispanic (6) Asians (3) Other ethnicities (1) |

5.12 (2.00–10.00)b | |||

| Mearini (2014) [59] | 275 | 86 | 26 | Gleason ≥7 | 65.40 | 6.80 | NR | 1. Elevated PSA (2.00–10.00 ng/ml) | 1. Acute or chronic prostatitis 2. Surgery or previous prostate biopsy 3. Medical treatment known to affect serum PSA levels |

NR | 4.50 (2.00–10.00)b |

| Morote (2016) [47] | 183 | 68 | 45 | Gleason ≥7 (any Gleason 4 pattern on biopsy) or cT3 |

67 | NR | 48–75 | 1. <75 yr 2. Elevated PSA (3.00–10.00 ng/ml) 3. Scheduled to biopsy (initial) |

NR | NR (Spanish) | 5.10 (3.00–10.00)b |

| Mortezavi (2021) [70] | 532 | 291 | 194 | Gleason ≥7 | 64 | 7 | NR | 1. 45–75 yr 2. No previous diagnosis of PCa 3. Elevated PSA or suspicious DRE |

1. Serious diseases such as metastatic cancers, severe cardiovascular disease, or dementia 2. Contraindications to MRI |

NR | 6.10 (4.10–8.80)b |

| Na (2014) [76] | 636 | 274 | 158 | Gleason 4 + 3 and ≥7 | 68 | NR | 25–100 | 1. PSA >4.00 ng/ml 2. % ratio of fPSA <0.16 3. Density of PSA >0.15 4. Presence of prostate nodules detected by DRE or TRUS |

NR | Asians | NR |

| Na (2017) [65] | 1538 | 618 | 488 | Gleason ≥7 | 66.95 | 8.89 | NR | 1. PSA >10.00 ng/ml 2. PSA >4.00 ng/ after 2–3 mo 3. %fPSA <0.16 when patients had a total level of total PSA >4.00 ng/ml 4. Suspicious lesions detected on DRE or TRUS with any PSA level |

NR | Asians | 11.42 (7.00–24.04)b |

| Nordström (2015) [93] | 531 | 271 | 134 | Gleason ≥7 | NR | NR | NR | 1. Elevated PSA (3.00–15.00 ng/ml) | NR | NR | NR |

| Nordström (2021) [69] | 1544 | 509 | 213 | ISUP grade ≥2 | 64.20 | 4.80 | 50–69 | 1. Elevated PSA (>3.00 ng/ml) | NR | NR | 4.2 ± 2.3 |

| Nygård (2016) [95] | 124 | 70 | 49 | Intermediate and high risk according to the European Association of Urology | 65.10a | 12.37a | NR | 1. Elevated PSA (3.00–25.00 ng/ml) 2. ≤75 yr 3. No previous biopsies ≤5 yr 4. Susceptible to radical treatment |

NR | NR | 7.20 (8.30–9.90)b |

| O'Malley (2017) [33] | 718 | 518 | 194 | Gleason ≥7 | 63 | NR | 57–68 | 1. Elevated PSA and/or in progression, <15% free PSA 2. Family history of PCa 3. Previous atypical small acinar proliferation or high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia of the prostate or suspicious for DRE |

1. Participación en un ensayo para enfermedad de la próstata 2. Biopsia de próstata (previous 6 mo) y exposición previa a la prueba de PCA3 |

African Americans (10) Non–African Americans (90) |

5.10 (3.80–7.00)b |

| Park (2018) [62] | 246 | 125 | 29 | Gleason ≥7 | 69.60 | 8.70 | NR | 1. Elevated PSA (≥3.50 ng/ml) and negative DRE | 1. Background of PCa or other urogenital cancers 2. Previous endoscopic surgery of the prostate, acute or chronic prostatitis (previous 3 mo), or untreated UTI 3. Previous prostate biopsy 4. Treated with dutasteride or finasteride 5. Chronic kidney failure, hemophiliacs, or those who previously received multiple transfusions |

NR | 7.80 (3.50–387.20)b |

| Punnen (2018) [34] | 366 | 215 | 131 | ISUP grade ≥2 | NR | NR | NR | 1. Prostate biopsy with ≥10 nuclei | 1. Background of PCa 2. DRE within 96 h of phlebotomy 3. Invasive treatment of the prostate 4. Treated with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (previous 3 mo) |

African Americans (56) Caucasians (40) Other ethnicities (4) |

NR |

| Roumiguié (2020) [49] | 117 | 64 | 24 | ISUP grade ≥2 | 65 | 63–67 | NR | 1. Elevated PSA or suspicious DRE | NR | NR | 7.00 (6.50–8.00)b |

| Ruffion (2013) [50] | 594 | 276 | 128 | Gleason ≥7 | 63 | NR | 58–67 | 1. >55 yr 2. Informed consent |

1. PSA ≥20.00 ng/ml 2. Previous prostate biopsy 3. Medical treatment known to affect serum PSA levels 4. Previous prostate surgery for BPH 5. <55 yr |

French | 5.90 (4.70–7.90)b |

| Ruffion (2014) [51] | 595 | 274 | 125 | Gleason ≥7 | 63 | 58-67 | NR | 1. Elevated PSA or suspicious DRE or family history of PCa | 1. PSA >20.00 ng/ml 2. ≥T2b 3. Previous surgery 4. Treated with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors |

NR | 5.90 (4.70–7.90)b |

| Sanchís-Bonet (2018) [48] | 197 | 85 | 44 | Gleason ≥7 | 68 | NR | 62–71 | 1. Elevated PSA (2.00–20.00 ng/ml) or suspicious DRE 2. >45 yr |

1. Treated with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (previous 6 mo) 2. UTI or urinary tract manipulation (previous 3 mo) |

NR (Spanish) | 5.80 (4.40–7.80)b |

| Sanda (2017) [35] | 516 | 254 | 156 | Gleason ≥7 | 62 | NR | 33–85 | 1. Scheduled to biopsy for the first time 2. Informed consent 3. Posturinary samples after rectal examination (DRE) prior to biopsy |

1. Background of PCa 2. Previous prostate biopsy 3. Previous prostatectomy 4. Other cancer diagnosis 5. Inability to provide a post-DRE urine sample |

Caucasians (81) African Americans (10) Asians (4) Other ethnicities (5) |

4.80 (0.30–460.40)b |

| 561 | 264 | 148 | 62 | 27–86 | Caucasians (79) African Americans (14) Asians (2) Other ethnicities (5) |

5.30 (0.20–274.90)b | |||||

| Schulze (2020) [20] | 122 | 76 | 50 | Gleason ≥7 | 65.41 | NR | 41–81 | 1. Timed to biopsy due to elevated PSA or in progression or suspicious DRE | NR | NR | 9.55 (1.91–82.90)b |

| Seisen (2015) [52] | 138 | 62 | 39 | Epstein classification | NR | NR | NR | 1. Elevated PSA (4.00–20.00 ng/ml) or suspicious DRE | 1. Treated with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (previous 3 mo) 2. Invasive treatment for BPH and acute bacterial prostatitis (previous 3 mo) 3. Chronic kidney failure, marked abnormalities in blood proteins, hemophiliacs, or those who previously received multiple transfusions |

NR | 7.80 (0.70–19.80)b |

| Shore (2019) [36] | 80 | 27 | 21 | ISUP grade ≥2 | 67 | 62–72 | NR | 1. Scheduled to biopsy | NR | Caucasians (90) African Americans (9) Other ethnicities (1) |

NR |

| Steuber (2022) [21] | 362 | NR | 103 | ISUP grade ≥2 | 64 a | 7.79 a | NR | 1. Elevated PSA (2.00–10.00 ng/ml) 2. Suspicious DRE (≥35 cm3) |

1. Treated with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors 2. Prostatitis, cistitis u otra alteración en la próstata 3. Previous prostate biopsy |

NR | 6.12 (4.61–7.65)b |

| Tan (2017) [67] | 157 | 30 | 19 | Gleason ≥7 | 65.40 | 6.46 | NR | 1. 50–75 yr 2. Suspicious DRE 3. Elevated PSA (4.00–10.00 ng/ml) |

1. Bacterial prostatitis 2. UTI not treated 3. Previous endoscopic prostate surgery 4. Background of PCa or other urogenital cancers 5. Previous prostate biopsy 6. Treated with dutasteride or finasteride |

Asians (99) Other ethnicities (1) |

6.71 ± 2.69c |

| Tomlins (2016) [37] | 711 | NR | NR | Gleason ≥7 | NR | NR | NR | 1. Scheduled for biopsy and urine evaluation T2: ERG and PCA3 | 1. Pretreatment for PCa 2. Surgical treatment of the prostate within 6 mo prior to urine collection 3. Prostate biopsy (previous 6 wk) |

NR | NR |

| 1225 | 518 | 224 | 64 | 58–70 | 1. Scheduled for biopsy | Caucasians (73) Non-Caucasians (27) |

4.70 (3.30–6.50)b | ||||

| Tosoian (2017) [94] | 135 | 75 | 46 | ISUP grade ≥2 | 64.30 | NR | 58.90–70.10 | 1. Elevated PSA, PSA kinetics, and/or abnormal rectal examination | NR | African Americans (36) | NR |

| Tosoian (2017) [38] | 118 | 47 | 35 | Gleason ≥7 | 64.20 | NR | 58.90–71.20 | 1. Elevated PSA and PSA kinetics | 1. Suspicious DRE | African Americans (10.2) | 7.40 (4.90–10.50)b |

| Tosoian (2021) [40] | 548 | 262 | 146 | ISUP grade ≥2 | 62 | NR | 56–67 | NR | NR | African Americans (14) | 4.90 (3.70–6.80)b |

| 516 | 253 | 156 | 61 | 56–67 | African Americans (10) | 4.80 (3.60–6.30)b | |||||

| 977 | 435 | 192 | 64 | 57–69 | African Americans (7.5) | 4.50 (3.10–6.00)b | |||||

| Van Neste (2016) [55] | 386 | 181 | 90 | Gleason ≥7 | 64.90 | 60–70 | NR | 1. Timed to biopsy (initial or repeated) by elevated PSA (3.00 ng/ml), suspicious DRE, or family history of PCa | 1. Background of PCa 2. Medical treatment known to affect serum PSA levels 3. Prostate biopsy (previous 3 mo) 4. Invasive treatment for BPH (previous 6 mo) |

NR | 7.30 (5.20–10.90)b |

| 519 | 212 | 109 | 64.70 | 60–70 | 7.40 (5.50–11.10)b | ||||||

| Wang (2017) [82] | 430 | 165 | NR | Gleason ≥7 | 66.29a | 6.53a | NR | 1. Elevated PSA (≥4.00 ng/ml) or suspicious DRE | 1. Another cancer diagnosis 2. Recent instrumentation or catheterization of the urethra 3. Treated with finasteride or hormonal treatment |

Asians | Con biopsia positiva y PSA 4.00–10.00 ng/ml: 7.90 (6.30–9.00)b Con biopsia negativa y PSA 4.00–10.00 ng/ml: 7.12 (5.60–8.50)b Con biopsia positiva y PSA >10.00 ng/ml: 28.80 (16.10–59.60)b Con biopsia negativa y PSA >10.00 ng/ml: 13.50 (11.00–19.70)b |

| Wei (2014) [41] | 562 | 264 | 148 | Gleason ≥7 | 62 | 8 | NR | 1. Timed to biopsy (initial) 2. Elevated PSA or in progression, <15% free PSA3 3. Family history of PCa 4. Previous atypical small acinar proliferation or suspicious or high-grade DRE prostate intraepithelial neoplasia |

1. Background of PCa 2. Participation in a trial for prostate disease 3. Previous prostate surgery 4. Previous prostate biopsy (previous 6 mo) 5. Previous PCA3 |

Caucasians (79) African Americans (14) Other ethnicities (7) |

7.00 ± 15.00 c |

| 297 | 67 | 26 | 64 | 8 | Caucasians (82) African Americans (11) Other ethnicities (7) |

10.00 ± 10.00c | |||||

| Woo (2020) [81] | 52 | 20 | 13 | Gleason ≥7 | 67.80 | NR | 51–83 | 1. Scheduled to biopsy by elevated PSA or suspicious DRE | NR | Caucasians | 8.60 (1.50–39.20)b |

| 165 | 107 | 83 | 66.50 | 47–82 | Caucasians (92.5) | 7.90 (0.10–46.80)b | |||||

| Wu (2019) [89] | 635 | 272 | 207 | Gleason ≥7 | 69 | NR | 61–76 | NR | 1. Lack of essential clinical data: age, PSA, %fPSA (free PSA divided by PSA), p2PSA or PV | Asians | 13.30 (7.60–31.50)b |

| 1045 | 449 | 347 | 68 | 62–74 | NR | 11.70 (7.00–25.70)b | |||||

| Wysock (2020) [42] | 50 | 26 | 22 | ISUP grade ≥2 | 63 | 52–74 | NR | 1. Elevated PSA | 1. Previous biopsy | Caucasians (74) African Americans (14) Hispanic (4) Other ethnicities (8) |

5.25 (3.80–8.13)b |

| Yu (2016) [83] | 261 | 67 | 30 | Gleason 4 + 3 and ≥8 | 67 | NR | 25–91 | 1. Elevated PSA (>4 ng/ml) 2. % ratio of fPSA <0.16 3. PSAD >0.15 4. Presence of prostate nodules detected by DRE or TRUS |

NR | NR | 10.67 (0.41–2006.25)b |

| Zappala (2017) [44] | 1012 | 470 | 231 | Gleason ≥7 | 66 | NR | 61–72 | 1. 10-cylinder TRUS-guided prostate biopsy | 1. Background of PCa 2. DRE within 96 h prior to phlebotomy 3. Treated with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (previous 6 mo) 4. Invasive urological procedures that can affect serum PSA levels (previous 6 mo) |

Caucasians (87) African Americans (8.5) Hispanic (4) Other ethnicities (0.5) |

NR |

BMI = body mass index; BPH = benign prostatic hyperplasia; DRE = digital rectal examination; fPSA = free prostate-specific antigen; IQR = interquartile range; ISUP = International Society of Urological Pathology; mpMRI = multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; NR = not reported; p2PSA = (-2) pro–prostate-specific antigen; PCa = prostate cancer; PCA3 = prostate cancer antigen 3; PHI = Prostate Health Index; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; PSAD = PSA density; PV = prostate volume; T2: ERG = gene fusion between transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) and the transcription factor ERG; SD = standard deviation; TRUS = transrectal ultrasound; UTI = urinary tract infection.

Own calculation.

Median (interquartile range).

Mean ± SD.

Range.

Mean ± SD (range).

Only diagnostic performance studies with an observational design were included: 43 prospective, 13 retrospective, two ambispective, two with a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data, three case-control studies, and two nested case-control studies. Ten studies contained two [25], [31], [35], [37], [41], [55], [78], [81], [89] or three [40] different populations and data were treated as separate studies.

The diagnostic tests analyzed were Prostate Health Index (PHI), a mathematical combination of free and total PSA and the [-2]pro-PSA isoform (Beckman Coulter, Inc.), in 37 studies [20], [22], [24], [25], [29], [30], [32], [38], [43], [46], [47], [48], [52], [54], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [64], [65], [67], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [80], [83], [87], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94]; Progensa prostate cancer antigen 3 (PCA3; Gen-Probe Incorporated) in 12 studies [23], [28], [41], [50], [51], [52], [53], [55], [66], [81], [82], [95]; PHI density in five studies [20], [26], [38], [59], [90]; SelectMDx in five studies [36], [42], [49], [57], [78]; 4Kscore test (OPKO Health, Inc.) in four studies [27], [34], [42], [44]; MyProstateScore (MLabs) in three studies [37], [40], [81]; TMPRSS2:ERG in two studies [37], [40]; Stockholm3 in two studies [69], [70]; ExoDx Prostate IntelliScore in one study [31]; and Proclarix test in one study [21]. All of these compared the performance of the tests with prostate biopsy (Table 1).

Included studies involved 34 287 men, 14 792 (43.14%) diagnosed with PCa and 7905 (23.06%) with csPCa. Not all studies included PSA-selected patients [23], [25], [78], [84], [87], [27], [34], [35], [36], [37], [40], [53], [74]. The selection criteria and main characteristics of participants are summarized in Table 2.

3.2. RoB in included studies

The RoB assessment is summarized in Figures 2A and 2B. Out of the 65 studies identified, only one was classified as having a low RoB in all domains. In the remaining studies, the most common methodological concerns involved the domains for the patient selection (19 studies at a high RoB), the index test domain (47 studies and the training cohorts in the studies by Sanda et al. [35], Tosoian et al. [40], and Woo et al. [81] at a high RoB), and the flow and timing (22 studies at a high RoB). The detailed judgments for each domain are available in Supplementary Table 3.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns (QUADAS-2 tool): (A) across studies and (B) within studies. QUADAS-2 = Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2.

3.3. Quality of evidence

The overall quality of the evidence for PHI and SelectMDx was considered low (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5 provide the evidence profiles, respectively).

3.4. Synthesis of results

Diagnostic accuracy results of selected studies are listed in Supplementary Table 6.

Out of the 65 included studies, only 21 remained for a quantitative analysis for PHI and SelectMDx [36], [42], [49], [57], [78]. The results of all meta-analyses and subgroups analyses are available in Supplementary Table 7.

3.4.1. Urine tests

3.4.1.1. Progensa PCA3

Cutoff points ranged from 5 to 35. For the cutoff point 15, the test yielded sensitivity ranging between 93% and 99%, and specificity of 37%. The cutoff point 20 showed sensitivity between 89% and 99%, and specificity of 51%. Finally, at the cutoff point 35, the sensitivity ranged between 62% and 71%, while the specificity increased to 59–66%. The AUC ranged from 0.59 to 0.83.

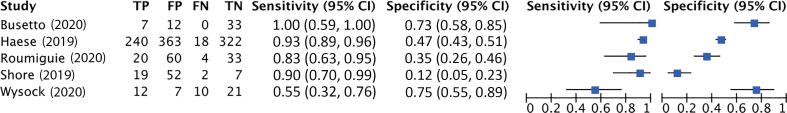

3.4.1.2. SelectMDx test

Pooled sensitivity and specificity were 84% (95% CI: 71– 92%; I2 = 79.7%; k = 5; n = 1957) and 49% (95% CI: 26– 72%; I2 = 93.9%; k = 5; n = 1957), respectively (see Fig. 3A). Pooled AUC was 0.79 (95% CI: 0.75–0.82; k = 5; n = 1957). Figure 3B shows the hierarchic summary ROC plot with 95% CI area and summary point.

Fig. 3.

Accuracy of SelectMDx test for csPCa detection. (A) Forest plot of sensitivity and specificity. (B) Summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve. AUC = area under the curve; CI = confidence interval; csPCa = clinically significant prostate cancer; FN = false negative; FP = false positive; SENS = sensitivity; SPEC = specificity; TN = true negative; TP = true positive.

3.4.1.3. TMPRSS2:ERG

Reported AUC ranged from 0.64 to 0.75. No data related to the sensitivity and specificity of TMPRSS2:ERG was reported.

3.4.1.4. MyProstateScore

With a cutoff point of ≤10, sensitivity ranged between 96.6% and 97.4%, and specificity between 28.6% and 34.6%. For cutoff points >10, the sensitivity ranged from 95.5% to 96.7%, while the specificity remains between 29% and 33.3% [40]. Reported AUC ranged between 0.60 and 0.80 [37], [81].

3.4.1.5. ExoDx Prostate IntelliScore

The sensitivity and specificity ranged from 91.89% to 97.44% and from 35.7% to 37.25%, respectively. The AUC ranged from 0.73 to 0.78 [31].

3.4.2. Blood tests

3.4.2.1. Prostate Health Index

Only 16 out of 37 selected studies on PHI were included in meta-analyses. Cutoff points ranged from 15 to 55. Subgroup analyses could be conducted by cutoff point and ethnic origin.

3.4.2.1.1. Cutoff point 15–20

Pooled sensitivity and specificity were 99% (95% CI: 97– 100%; I2 = 76.26%; k = 4; n = 2994) and 14% (95% CI: 9–19%; I2 = 87.03%; k = 4; n = 2994), respectively (Fig. 4A). Pooled AUC was 0.53 (95% CI: 0.49–0.57; k = 4; n = 2994; Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Accuracy of PHI test for csPCa detection. (A) Forest plot of sensitivity and specificity: cutoff point 15–20. (B) Summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve: cutoff point 15–20. (C) Forest plot of sensitivity and specificity: cutoff point 20–25. (D) SROC curve: cutoff point 20–25. (E) Forest plot of sensitivity and specificity: cutoff point 25–30. (F) SROC curve: cutoff point 25–30. AUC = area under the curve; CI = confidence interval; csPCa = clinically significant prostate cancer; FN = false negative; FP = false positive; PHI = Prostate Health Index; SENS = sensitivity; SPEC = specificity; TN = true negative; TP = true positive.

PHI showed higher sensitivity and specificity in patients of Asian origin (sensitivity = 100%; 95% CI: 99–100%; specificity = 13%; 95% CI: 4–22%; k = 1; n = 1556) than in patients of European origin (sensitivity = 98%; 95% CI: 96–100%; specificity = 13%; 95% CI: 8–19%; k = 3; n = 1428).

3.4.2.1.2. Cutoff point 20–25

Pooled sensitivity and specificity were 96% (95% CI: 94–98%; I2 = 73.26%; k = 7; n = 6698) and 24% (95% CI: 18–30%; I2 = 95.57%; k = 7; n = 6698), respectively (Fig. 4C). The AUC obtained was 0.71 (95% CI: 0.67–0.75; k = 7; n = 6698; Fig. 4D).

Again, higher accuracy was obtained in Asian patients (sensitivity = 99%; 95% CI: 97–100%; specificity = 30%; 95% CI: 20–39%; k = 3; n = 2744) than in European patients (sensitivity = 95%; 95% CI: 93–97%; specificity = 21%; 95% CI: 16–26%; k = 4; n = 3954).

3.4.2.1.3. Cutoff point 25–30

Pooled sensitivity and specificity were 95% (95% CI: 89–98%; I2 = 85.72%; k = 9; n = 6321) and 33% (95% CI: 23–45%; I2 = 98.27%; k = 9; n = 6321), respectively (Fig. 4E). The derived AUC showed an accuracy of 0.76 (95% CI: 0.72–0.79; k = 9; n = 6321; Fig. 4F).

Sensitivity was higher in Asian patients (98%; 95% CI: 94–100%; k = 5; n = 3680) than in African-American (94%; 95% CI: 83–100%; k = 1; n = 293) and European (93%; 95% CI: 87–100%; k = 4; n = 2348) patients. Specificity was higher in Asian patients (41%; 95% CI: 25–58%; k = 5; n = 3680), followed by European (30%; 95% CI: 15–44%; k = 4; n = 2348) and African-American patients (15%; 95% CI: 5–34%; k = 1; n = 293) patients.

3.4.2.1.4. Cutoff point 30–35

Pooled sensitivity and specificity were 87% (95% CI: 81–91%; I2 = 88.94%; k = 9; n = 5964) and 49% (95% CI: 41–58%; I2 = 95.53; k = 9; n = 5,964), respectively. Pooled AUC was 0.76 (95% CI: 0.72–0.80; k = 9; n = 5964).

Sensitivity was higher in Asian patients (91%; 95% CI: 84–97%; k = 4; n = 2794) and African Americans (91%; 95% CI: 78–100%; k = 1; n = 293) than in European patients (85%; 95% CI: 79–91%; k = 5; n = 2877). Specificity was higher in Asian patients (58%; 95% CI: 46–70%; k = 4; n = 2794), followed by European (49%; 95% CI: 41–57%; k = 5; n = 2877) and African-American (26%; 95% CI: 11–41%; k = 1; n = 293) patients.

3.4.2.1.5. Cutoff point 35–40

Pooled sensitivity and specificity were 79% (95% CI: 66–88%; I2 = 83.13%; k = 5; n = 1164) and 56% (95% CI: 48–64%; I2 = 81.78; k = 5; n = 1164), respectively. The AUC obtained was 0.69 (95% CI: 0.64–0.72; k = 0; n = 5964). Despite the high level of heterogeneity between studies, no differences were observed between Asian and European patients (p = 0.14).

3.4.2.1.6. Cutoff point 55

The sensitivity was 42% (95% CI: 32–53%; I2 = 73.61%; k = 3; n = 2028), while the specificity was 87% (95% CI: 72–95%; I2 = 98.28%; k = 3; n = 2028). Pooled AUC showed an accuracy of 0.60 (95% CI: 0.56–0.64; k = 3; n = 2028).

No subgroup analysis could be performed by ethnic origin.

3.4.2.2. PHI density

Among the studies included for this test [20], [26], [38], [59], [90], the range for sensitivity was 90–97% and that for specificity was 32–39%.

3.4.2.3. 4Kscore test

Four studies provided data on this test [27], [34], [42], [44].

Assuming a risk of suffering csPCa of ≥7.5%, the sensitivity was 95.5% and the specificity was 32.1%, whereas when a risk of 12% was assumed, the sensitivity decreased to 90.1% and the specificity increased to 53.5%. The AUC ranged from 0.72 to 0.87.

3.4.2.4. Stockholm3 test

Studies identified do not report sensitivity and specificity data [69], [70]. The AUC ranged from 0.77 to 0.86.

3.4.2.5. Proclarix

The only included study obtained sensitivity and specificity of 91% and 22%, respectively [21].

3.5. Publication bias

No publication bias was identified, except in the PHI analysis with a cutoff point between 30 and 35 (p = 0.02). The results of the Egger tests and Deeks asymmetry graphs are available in Supplementary Table 7 and Supplementary Figure 1, respectively.

3.6. Discussion

The assessment of molecular biomarkers for the detection of csPCa is based on the data derived from 65 studies (N = 34 287), which evaluate their diagnostic accuracy in a population undergoing initial biopsy for suspected csPCa due to high PSA levels, family history, abnormal DRE, or altered multiparametric MRI. Quality of evidence for the tests included in the meta-analysis (PHI and SelectMDx) has been rated as low.

Included studies present high variability in terms of the assessed tests. Most (37) assessed the performance of the PHI [20], [22], [24], [25], [29], [30], [32], [38], [43], [46], [47], [48], [52], [54], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [64], [65], [67], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [80], [83], [87], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], although only 16 of them could be included in the meta-analysis. Other blood tests assessed were PHI density [20], [26], [38], [59], [90], 4Kscore test [27], [34], [42], [44], Stockholm3 test [69], [70], and Proclarix test [21]. The diagnostic test based on the analysis of urine samples assessed by the highest number of studies was Progensa PCA3 [23], [28], [41], [50], [51], [52], [53], [55], [66], [81], [82], [95]. Other urine tests assessed were SelectMDx [36], [42], [49], [57], [78], MyProstateScore [33], [35], [37], [40], [81], TMPRSS2:ERG [37], [40], and ExoDx Prostate IntelliScore [31].

Approximately 77% of biopsies performed in men included in this SR did not yield a positive csPCa result. Furthermore, a 20% received a diagnosis of iPCa, placing them at risk of overdiagnosis, biopsy-related complications, and wasted health care resources, evidencing the need for better risk stratification.

Results of the assessed tests are measured on a continuous scale so that their behavior depends on where the cutoff point is set. However, information on established cutoff points was not provided in 25 of the included studies [22], [27], [32], [33], [34], [37], [38], [41], [46], [48], [55], [58], [59], [62], [69], [75], [76], [80], [81], [82], [87], [89], [91], [93], [94], and variability in terms of selected cutoffs is present among studies assessing the same test. Since the optimal 4Kscore, PCA3, and PHI cutoff points for the diagnosis of csPCa are not established, a comparison of diagnostic accuracy at different cutoff points was performed.

The results indicate that four analyzed tests (two urine tests and two blood tests) show an ability to identify ≥95% patients with csPCa: Progensa PCA3, with cutoff point 15; My-Prostate Score, using a cutoff point of >10; PHI, with any cutoff point between 15 and 30; and 4Kscore test, assuming a risk of csPCa of ≥7.5%. Using these tests and cutoff points, the ability to prevent unnecessary biopsies ranged between 14% and 37% [22], [24], [25], [28], [29], [30], [40], [42], [47], [51], [64], [65], [67], [72], [73], [77] which shows that theses could be useful as a noninvasive method of supporting the decision on whether or not the first prostate biopsy is necessary and, consequently, reducing the total number of unnecessary biopsies. However, it should be taken into account that only the results related to PHI are pooled effect estimates. The biomarker-based tests considered in this SR (particularly, PHI) would be included with triaging purposes in the diagnostic pathway for patients with a high clinical suspicion of csPCa but negative MRI results, in order to prevent unnecessary biopsies.

Of the nine SRs on biomarker-based tests for the management of PCa published to date to the best of our knowledge [62], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], only two focused on evaluating the use of these tests in discerning iPCa from csPCa and, consequently, in improving the decision-making process for first biopsies and treatment planning. Nevertheless, neither of them analyzes the available scientific evidence for all available tests, but rather for specific tests. Russo et al. [96] obtained for PHI and 4Kscore tests, sensitivity for the detection of csPCa of 93% and 87%, respectively, and specificity of 34% and 61%, respectively. Zappala et al. [101] evaluated the predictive precision of 4Kscore to discriminate between patients with and without csPCa, obtaining a pooled estimate for AUC of 0.80. Our results are consistent with these previous results.

One aspect to consider is the difference in test accuracy depending on the ethnic origin of patients. The evidence has shown possible improved performance of these tests in Asian populations, followed by Caucasian and African-American men. Confirmation of this finding would support the need for research on the best cutoff points based on patient ethnicity.

Available evidence exclusively consists of studies that evaluate the diagnostic validity of tests. However, using new tests with evidence of diagnostic utility does not directly imply improving decisions related to the diagnosis and treatment of PCa. Therefore, further research is needed to determine what effect the implementation of these tests would have on clinical decision making and patient-important health outcomes (eg, complications, recurrence-free survival, cancer survival, morbidity, and quality of life).

The main limitation of the present review is the methodological differences among studies, mainly the diversity or the lack of information about cutoff values. Moreover, a subgroup analysis to explore this issue could not always be performed. Another potential limitation is the possibility that some studies have not been included because those are not written in English or Spanish or because those are not indexed in the consulted databases. However, to the best of our knowledge, our SR is the most extensive review carried out to date on the effectiveness of the incorporation of tests, based on biomarkers in samples of blood or urine, for the identification of patients at high risk of csPCa. Methodologically, the SR benefits from rigorous methods following the fundamental principles of transparency and replicability; a comprehensive search, a peer selection, data extraction, and RoB assessment; and an assessment of the certainty of evidence on the basis of a structured and explicit approach.

4. Conclusions

Our findings indicate that PHI has high diagnostic accuracy for csPCa detection, and its incorporation in the diagnostic pathway could reduce unnecessary biopsies. However, there is a lack of evidence on the effects on patient consequences, supporting the need for well-conducted test-treatment RCTs in which investigators allocate patients to receive a PHI test or a control diagnostic approach (no test), and measure patient-important outcomes. Based on the pooled sensitivity estimate for SelectDMx, it is possible that the use of this test for the identification of patients with csPCa is not the best option. Finally, according to the limited available evidence, it is not possible to reach a clear conclusion on the other tests evaluated.

Author contributions: Tasmania del Pino-Sedeño had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Tasmania del Pino-Sedeño.

Acquisition of data: Tasmania del Pino-Sedeño, Diego Infante-Ventura, Aythami de Armas Castellano.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Tasmania del Pino-Sedeño.

Drafting of the manuscript: Tasmania del Pino-Sedeño, Diego Infante-Ventura, Aythami de Armas Castellano, María M. Trujillo-Martín.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Tasmania del Pino-Sedeño, Pedro de Pablos-Rodríguez, Antonio Rueda-Domínguez, Pedro Serrano-Aguilar, María M. Trujillo-Martín.

Statistical analysis: Tasmania del Pino-Sedeño.

Obtaining funding: Trujillo-Martín, Pedro Serrano-Aguilar.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Tasmania del Pino-Sedeño, Diego Infante-Ventura, Aythami de Armas Castellano.

Supervision: Tasmania del Pino-Sedeño, María M. Trujillo-Martín.

Other: None.

Financial disclosures: Tasmania del Pino-Sedeño certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: The study was financed by the Ministry for Health of Spain in the framework of activities developed by the Spanish Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment and Services for the National Health System (RedETS).

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to acknowledge Carlos Rodríguez for his help in the documentation tasks and Leticia Rodríguez for her support in the study search process. We are also grateful to Patrick Dennis for English language editing support with the final manuscript.

Associate Editor: Guillaume Ploussard

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euros.2022.10.017.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Supplementary figure.

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre L.A., Siegel R.L., Ward E.M., Jemal A. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends—an update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:16–27. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell K.J.L., Del Mar C., Wright G., Dickinson J., Glasziou P. Prevalence of incidental prostate cancer: a systematic review of autopsy studies. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:1749–1757. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferlay J., Ervik M., Lam F., et al. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon, France: 2020. Global cancer observatory: cancer today; p. 419. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Cancer Institute . National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 2019. SEER cancer stat facts.https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenton J., Weyrich M., Durbin S., Liu Y., Bang H., Melnikow J. Prostate-specific antigen-based screening for prostate cancer: evidence report and a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319:1914–1931. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Briers E, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. 2021.

- 8.Loeb S., Dani H. Whom to biopsy: prediagnostic risk stratification with biomarkers, nomograms, and risk calculators. Urol Clin North Am. 2017;44:517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

- 10.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sterne J.A.C., Savović J., Page M.J., et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J. 2019;366 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whiting P.F., Rutjes A.W.S., Westwood M.E., et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deeks J.J., Macaskill P., Irwig L. The performance of tests of publication bias and other sample size effects in systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy was assessed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:882–893. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dwamena B. MIDAS: Stata module for meta-analytical integration of diagnostic test accuracy studies. Statistical Software Components. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins J.P.T., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schünemann H.J., Mustafa R.A., Brozek J., et al. GRADE guidelines: 22. The GRADE approach for tests and strategies—from test accuracy to patient-important outcomes and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;111:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parekh D., Punnen S., Sjoberg D., et al. A multi-institutional prospective trial in the USA confirms that the 4Kscore accurately identifies men with high-grade prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68:464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bollito E., De Luca S., Cicilano M., et al. Prostate cancer gene 3 urine assay cutoff in diagnosis of prostate cancer: a validation study on an Italian patient population undergoing first and repeat biopsy. Anal Quant Cytol Histol. 2012;34:96–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hennenlotter J., Neumann T., Alperowitz S., et al. Age-adapted prostate cancer gene 3 score interpretation—suggestions for clinical use. Clin Lab. 2020;66 doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2019.190714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulze A., Christoph F., Sachs M., et al. Use of the Prostate Health Index and density in 3 outpatient centers to avoid unnecessary prostate biopsies. Urol Int. 2020;104:181–186. doi: 10.1159/000506262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steuber T., Heidegger I., Kafka M., et al. PROPOSe: a real-life prospective study of Proclarix, a novel blood-based test to support challenging biopsy decision-making in prostate cancer. Eur Urol Oncol. 2022;5:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2020.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Babajide R., Carbunaru S., Nettey O.S., et al. Performance of Prostate Health Index in biopsy naïve black men. J Urol. 2021;205:718–724. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao L., Lee C.H., Ning J., Handy B.C., Wagar E.A., Meng Q.H. Combination of prostate cancer antigen 3 and prostate-specific antigen improves diagnostic accuracy in men at risk of prostate cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:1106–1112. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0185-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Catalona W.J., Partin A.W., Sanda M.G., et al. A multi-center study of [−2]pro-prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in combination with PSA and free PSA for prostate cancer detection in the 2.0 to 10.0 ng/ml PSA range. J Urol. 2011;185:1650–1655. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De La Calle C., Patil D., Wei J.T., et al. Multicenter evaluation of the prostate health index to detect aggressive prostate cancer in biopsy naïve men. J Urol. 2015;194:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.01.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Druskin S.C., Tosoian J.J., Young A., et al. Combining Prostate Health Index density, magnetic resonance imaging and prior negative biopsy status to improve the detection of clinically significant prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2018;121:619–626. doi: 10.1111/bju.14098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Falagario U.G., Lantz A., Jambor I., et al. Using biomarkers in patients with positive multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging: 4Kscore predicts the presence of cancer outside the index lesion. Int J Urol. 2021;28:47–52. doi: 10.1111/iju.14385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen J., Auprich M., Ahyai S.A., et al. Initial prostate biopsy: development and internal validation of a biopsy-specific nomogram based on the prostate cancer antigen 3 assay. Eur Urol. 2013;63:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loeb S., Sanda M.G., Broyles D.L., et al. The prostate health index selectively identifies clinically significant prostate cancer. J Urol. 2015;193:1163–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.10.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loeb S., Shin S.S., Broyles D.L., et al. Prostate Health Index improves multivariable risk prediction of aggressive prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2017;120:61–68. doi: 10.1111/bju.13676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKiernan J., Donovan M.J., O’Neill V., et al. A novel urine exosome gene expression assay to predict high-grade prostate cancer at initial biopsy. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:882–889. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertok T., Jane E., Bertokova A., et al. Validating fPSA glycoprofile as a prostate cancer biomarker to avoid unnecessary biopsies and re-biopsies. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:2988. doi: 10.3390/cancers12102988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Malley P.G., Nguyen D.P., Al Hussein Al Awamlh B., et al. Racial variation in the utility of urinary biomarkers PCA3 and T2ERG in a large multicenter study. J Urol. 2017;198:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Punnen S., Freedland S.J., Polascik T.J., et al. A multi-institutional prospective trial confirms noninvasive blood test maintains predictive value in African American men. J Urol. 2018;199:1459–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.11.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanda M.G., Feng Z., Howard D.H., et al. Association between combined TMPRSS2:ERG and PCA3 RNA urinary testing and detection of aggressive prostate cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1085–1093. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shore N., Hafron J., Langford T., et al. Urinary molecular biomarker test impacts prostate biopsy decision making in clinical practice. Urol Pract. 2019;6:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.urpr.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomlins S.A., Day J.R., Lonigro R.J., et al. Urine TMPRSS2:ERG plus PCA3 for individualized prostate cancer risk assessment. Eur Urol. 2016;70:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tosoian J.J., Druskin S.C., Andreas D., et al. Prostate Health Index density improves detection of clinically significant prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2017;120:793–798. doi: 10.1111/bju.13762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tosoian J.J., Patel H.D., Mamawala M., et al. Longitudinal assessment of urinary PCA3 for predicting prostate cancer grade reclassification in favorable-risk men during active surveillance. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2017;20:339–342. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2017.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tosoian J.J., Trock B.J., Morgan T.M., et al. Use of the MyProstateScore test to rule out clinically significant cancer: validation of a straightforward clinical testing approach. J Urol. 2021;205:732–739. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei J.T., Feng Z., Partin A.W., et al. Can urinary PCA3 supplement PSA in the early detection of prostate cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:4066–4072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.8505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wysock J.S., Becher E., Persily J., Loeb S., Lepor H. Concordance and performance of 4Kscore and SelectMDx for informing decision to perform prostate biopsy and detection of prostate cancer. Urology. 2020;141:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chiu P.K.F., Teoh J.Y.C., Lee W.M., et al. Extended use of prostate health index and percentage of [-2]pro-prostate-specific antigen in Chinese men with prostate specific antigen 10–20 ng/mL and normal digital rectal examination. Investig Clin Urol. 2016;57:336–342. doi: 10.4111/icu.2016.57.5.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zappala S.M., Dong Y., Linder V., et al. The 4Kscore blood test accurately identifies men with aggressive prostate cancer prior to prostate biopsy with or without DRE information. Int J Clin Pract. 2017;71:e12943. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Filella X., Foj L., Alcover J., Augé J.M., Molina R., Jiménez W. The influence of prostate volume in prostate health index performance in patients with total PSA lower than 10μg/L. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;436:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Foj L., Filella X. Development and internal validation of a novel PHI-nomogram to identify aggressive prostate cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;501:174–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2019.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morote J., Celma A., Planas J., et al. Eficacia del índice de salud prostática para identificar cánceres de próstata agresivos. Una validación institucional. Actas Urol Esp. 2016;40:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanchís-Bonet A., Barrionuevo-González M., Bajo-Chueca A.M., et al. Validation of the prostate health index in a predictive model of prostate cancer. Actas Urol Esp. 2018;42:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roumiguié M., Ploussard G., Nogueira L., et al. Independent evaluation of the respective predictive values for high-grade prostate cancer of clinical information and RNA biomarkers after upfront MRI and image-guided biopsies. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:285. doi: 10.3390/cancers12020285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruffion A., Devonec M., Champetier D., et al. PCA3 and PCA3-based nomograms improve diagnostic accuracy in patients undergoing first prostate biopsy. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:17767–17780. doi: 10.3390/ijms140917767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruffion A., Perrin P., Devonec M., et al. Additional value of PCA3 density to predict initial prostate biopsy outcome. World J Urol. 2014;32:917–923. doi: 10.1007/s00345-014-1251-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seisen T., Rouprêt M., Brault D., et al. Accuracy of the prostate health index versus the urinary prostate cancer antigen 3 score to predict overall and significant prostate cancer at initial biopsy. Prostate. 2015;75:103–111. doi: 10.1002/pros.22898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leyten G.H.J.M., Hessels D., Smit F.P., et al. Identification of a candidate gene panel for the early diagnosis of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3061–3070. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chiu P.K.F., Roobol M.J., Teoh J.Y., et al. Prostate Health Index (PHI) and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) predictive models for prostate cancer in the Chinese population and the role of digital rectal examination-estimated prostate volume. Int Urol Nephrol. 2016;48:1631–1637. doi: 10.1007/s11255-016-1350-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Neste L., Hendriks R.J., Dijkstra S., et al. Detection of high-grade prostate cancer using a urinary molecular biomarker–based risk score. Eur Urol. 2016;70:740–748. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Foley R.W., Maweni R.M., Gorman L., et al. European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) risk calculators significantly outperform the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) 2.0 in the prediction of prostate cancer: a multi-institutional study. BJU Int. 2016;118:706–713. doi: 10.1111/bju.13437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Busetto G.M., Del Giudice F., Maggi M., et al. Prospective assessment of two-gene urinary test with multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate for men undergoing primary prostate biopsy. World J Urol. 2020;39:1869–1877. doi: 10.1007/s00345-020-03359-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]