Abstract

Background:

Most safety and efficacy trials of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines excluded cancer patients, yet these patients are more likely than healthy subjects to contract SARS-CoV2 and more likely to become seriously ill following infection. Our objective was to record short-term adverse reactions to the COVID-19 vaccine in cancer patients, to compare the magnitude and duration of these reactions to those of cancer-free subjects, and to determine if adverse reactions are related to active cancer therapy.

Patients and Methods:

A prospective, single-institution observational study was performed in an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center. All study participants received two doses of the Pfizer BNT162b2 vaccine separated by approximately three weeks. A report of adverse reactions to dose 1 of the vaccine was completed upon return to the clinic for dose 2. Participants completed an identical survey either online or by telephone two weeks after the second vaccine dose.

Results:

The cohort of 1,753 patients included 66.7% with a history of cancer and 16.6% who were receiving active cancer treatment. Local pain at the injection site was the most frequently reported symptom for all respondents and did not distinguish cancer patients from non-cancer patients after either dose 1 (39.3% vs 43.9%, p=0.07) or dose 2 (42.5% vs 40.3%, p=0.45). Among cancer patients, those receiving active treatment were less likely to report pain at the injection site after dose 1 (30.0% vs 41.4%, p=0.002) The onset and duration of adverse events was otherwise unrelated to active cancer treatment.

Conclusions:

When cancer patients were compared to cancer-free subjects, few differences in reported adverse events were noted. Active cancer treatment had little impact on side-effect profiles.

Background:

Over 338 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine were administered in the United States from December 2020 to July 2021. This far-reaching public health initiative generated 5,325 reports of vaccine-related deaths.1,2 Although deaths have been exceedingly rare, mild-to-moderate complications, even in healthy adults, have been common. Side effects that include body aches, chills, and headaches are especially frequent after the second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, affecting one-half to two-thirds of those vaccinated. For cancer patients, it is especially important to clarify the risk of vaccination, since these patients are more likely than healthy subjects to contract SARS CoV-2 and more likely to become seriously ill if infected.3,4 Those with hematologic malignancies and lung cancer are particularly vulnerable. As a group, cancer patients infected with COVID-19 are reported to suffer a mortality rate three times that of persons without cancer.5

Despite their vulnerability to infection, cancer patients were not included in most pilot investigations of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and were rarely analyzed as a group in follow-up studies.6,7 Several lines of evidence, however, indicate that they may present unique challenges when a strategy for broad vaccination coverage is initiated. Some of those challenges, including the imposition of stricter isolation, are logistical. Other challenges remain theoretical. Both the Moderna mRNA-1273 and the Pfizer BNT162b2 vaccines are delivered as lipid nanoparticles containing mRNA that encodes the coronavirus spike protein.8 Lysosomal particles tend to accumulate in solid tumors, a phenomenon exploited in the delivery of some anti-cancer drugs. It is not known if vaccines of this kind may also be diverted to malignant cells, thus altering tumor biology and perhaps interfering with the immune response to the vaccine in unforeseen ways.

A further concern has been vaccine hesitancy by persons who are priority candidates for vaccination. Within this group, cancer patients figure prominently. A European study reported that 11.2% of cancer patients offered vaccination refused it, usually out of fear of adverse events.9 Circulation of false or misleading reports may have fueled much of the alarm, underscoring the need for accurate reporting of scientific progress. With these considerations in mind, we undertook a study of adverse reactions to vaccination reported by the attendees of an outpatient clinic serving a large population of cancer patients. The aims of the study were: 1) to record short-term adverse reactions to the COVID-19 vaccine in cancer patients and compare these reactions to those of cancer-free subjects and 2) to determine if adverse reactions are associated with active cancer therapy.

Methods:

This IRB-approved study was conducted in an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center serving both cancer patients and non-cancer patients. Participants were enrolled from February 16, 2021 to May 15, 2021. All respondents received two doses of the Pfizer BNT162b2 vaccine given about three weeks apart. A detailed survey eliciting a report of adverse reactions to dose 1 of the vaccine, including their time of onset and duration, was completed by patients upon return to the clinic for dose 2. An identical survey was completed either by telephone or online about two weeks after the second vaccine dose. Vaccine recipients were asked to report if they had experienced any of the following symptoms: tiredness, muscle pain, fever, chills, headache, local pain or swelling at the injection site, joint pain, nausea, or an allergic reaction (i.e. hives, facial swelling, shortness of breath, or wheezing). They were also given an opportunity to report symptoms not specified in the Survey. Additional participant data obtained from the institution’s data warehouse included age, race, ethnicity, history of cancer (if any) and recent or ongoing cancer treatment, including surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy and hormonal therapy. Patients with a cancer diagnosis who received cancer treatment (other than immunotherapy) at any point during a time interval beginning thirty days before the first vaccine dose and ending with the second dose were considered to be under active treatment. For patients receiving immunotherapy, the time period for active treatment was extended to ninety days prior to the first vaccine dose. Early symptom onset was defined as an adverse event within 24 hours of vaccination.

The baseline characteristics of the study population were tabulated separately for non-cancer patients, unselected cancer patients, and active treatment cancer patients. The incidence of all reported adverse reactions was tallied for dose 1 and dose 2 of the vaccine. Fisher’s exact tests and chi-square tests were used to determine if the incidence of each type of adverse reaction was related to demographic characteristics, history of malignancy, active cancer treatment, or type of therapy. Mean duration and mean time to onset of symptoms were recorded for noncancer recipients, cancer patients, and active treatment patients with 95% confidence intervals and compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. McNemar’s test was used to compare symptom rates for participants who responded to both post-vaccination surveys. All hypothesis tests were two-sided with a 5 percent type I error. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

Results:

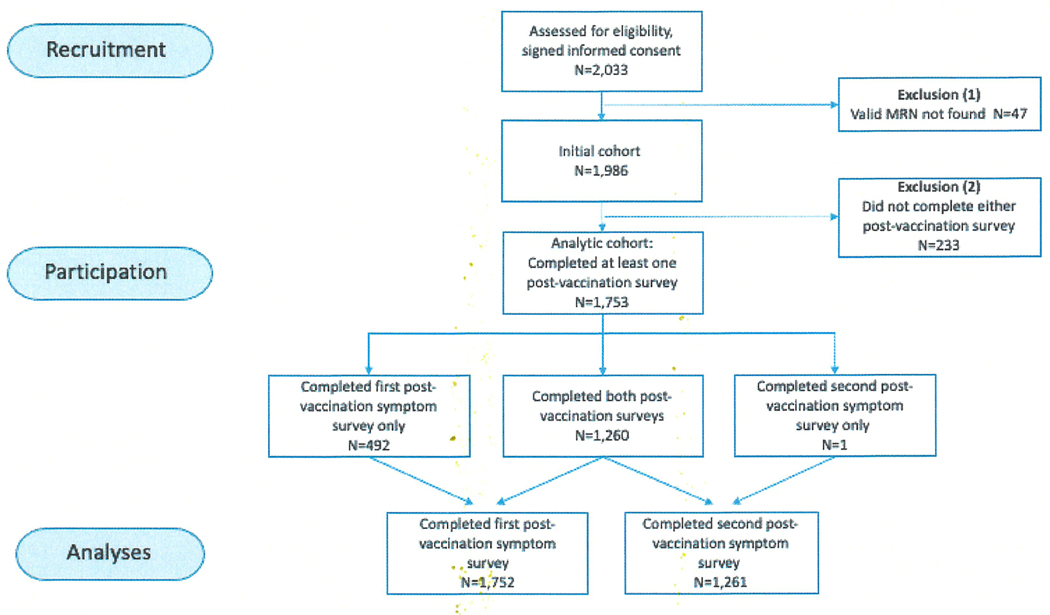

There were 2,033 patients enrolled in the study. The first survey was completed by 1,752 patients following vaccine dose 1; both the first and second survey were completed by 1,260 patients (Figure 1). Patient dropouts before the first survey (233/1,986) were more likely to be male (48.5% vs 38.8%; p=0.005) and less likely to have a cancer diagnosis (60.5% vs 67.5%; p=0.034). Of the respondents that completed at least one post-vaccination survey, 67.5% (1,183/1,753) had a history of cancer, and 17.8% (211/1,183) of them were receiving active cancer treatment. Of those with a history of cancer, 92.5% (1,094/1,183) had a solid malignancy and 7.5% (89/1,183) had a hematologic malignancy. The form of active treatment was surgery for 20.4% (43/211) of patients, radiation therapy for 13.7% (29/211), chemotherapy for 39.8% (84/211), and other systemic therapy (immunotherapy, targeted therapy, or hormone therapy) for 26.1% (55/211) (Table 1). Patients with a cancer diagnosis were older (median age 68 vs 66, p<0.001), and were more likely to be black (20.1% vs 10.6%, p<0.001) and male (42.2% vs 31.9%, p<0.001) than those in the non-cancer cohort. A history of COVID-19 infection prior to vaccination was reported by 3.4% of all respondents.

Figure 1.

Strobe flow diagram

Table 1.

Patient characteristics for respondents who completed at least one post-vaccination symptom survey

| All | No Ca | Ca Dx | On Active Tx | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | |

|

| ||||||||

| N Patients | 1753 | 570 | 1183 | |||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 1072 | (61) | 388 | (68) | 684 | (58) | 116 | (55) |

| Male | 681 | (39) | 182 | (32) | 499 | (42) | 95 | (45) |

| Age, years | ||||||||

| median (IQR) | 67 | (59–74) | 66 | (54–72) | 68 | (61–74) | 66 | (57–73) |

| Race | ||||||||

| African American/Black | 293 | (17) | 56 | (10) | 237 | (20) | 33 | (16) |

| Asian/Indian/Pacific Islander | 61 | (3) | 32 | (6) | 29 | (2) | 6 | (3) |

| Caucasian/White | 1213 | (69) | 369 | (65) | 844 | (71) | 137 | (65) |

| Other Race | 138 | (8) | 70 | (12) | 68 | (6) | 34 | (16) |

| Unknown | 48 | (3) | 43 | (8) | 5 | (0) | 1 | (0) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 47 | (3) | 21 | (4) | 26 | (2) | 2 | (1) |

| Non-Hispanic | 1625 | (93) | 491 | (86) | 1134 | (96) | 201 | (95) |

| Unknown/missing | 81 | (5) | 58 | (10) | 23 | (2) | 8 | (4) |

| Cancer Type | ||||||||

| Hematologic malignancy | 89 | (8) | 19 | (9) | ||||

| Solid malignancy | 1094 | (92) | 192 | (91) | ||||

| Type of Treatment* | ||||||||

| Surgery | 51 | (24) | ||||||

| Radiation | 38 | (18) | ||||||

| Chemotherapy | 84 | (40) | ||||||

| Immunotherapy | 35 | (17) | ||||||

| Hormone Therapy | 125 | (59) | ||||||

| Targeted Therapy | 51 | (24) | ||||||

Patients could receive more than one type of treatment

Post-vaccination symptoms were common and reported with similar frequencies by cancer patients and non-cancer patients (73.3% vs 72.5%, p=0.71). No significant differences between cancer patients and cancer-free subjects in the frequency of adverse events were found when responses to the first and second vaccine dose were tabulated separately (dose 1: 61.3% vs 60.2%, p=0.67; dose 2: 64.29% vs 62.8%, p=0.63). Among respondents to both surveys, at least one adverse event was reported more often for dose 2 than dose 1 (63.7% vs 60.2%, p=0.024). For the cancer patients, adverse events reported more frequently after dose 2 included fatigue, joint pain, fever, chills, headache and nausea. Allergic reactions were rare after both dose 1 (6/1,746) and dose 2 (9/1,252). Post-vaccination symptoms for all patients were more likely to be reported by women than men (77.8% vs 65.5%, p<0.001) and were more common in younger patients (18–59 yrs=84.4%, 60–79 yrs=72.2%, ≥80yrs=50.0%, p<0.001).

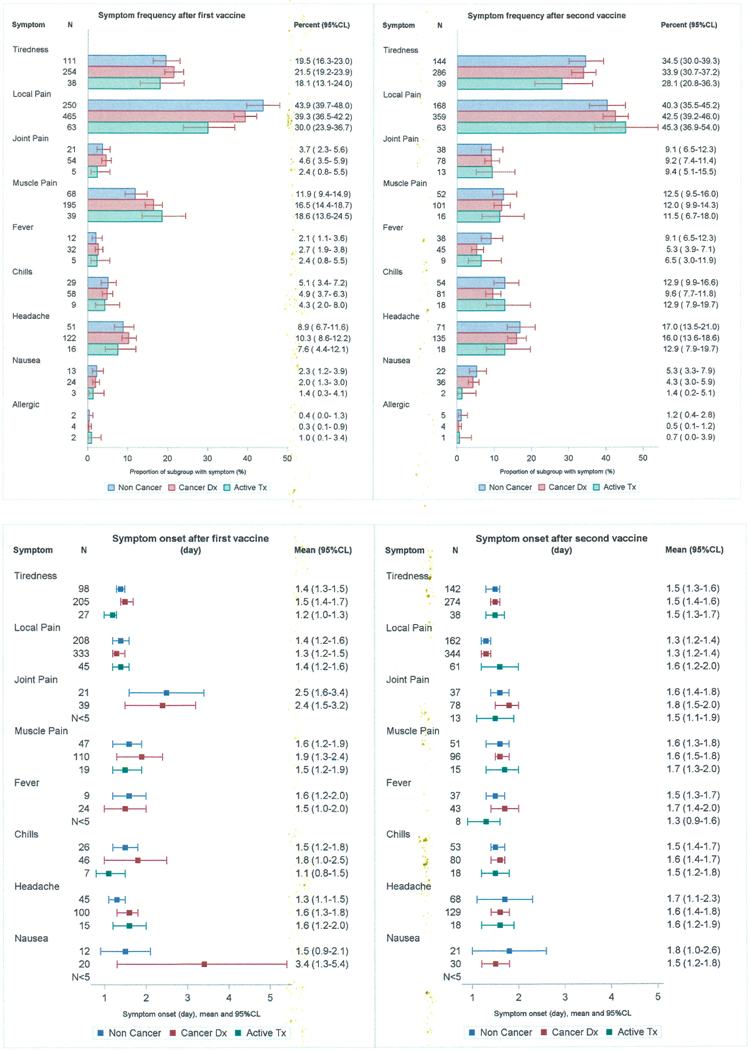

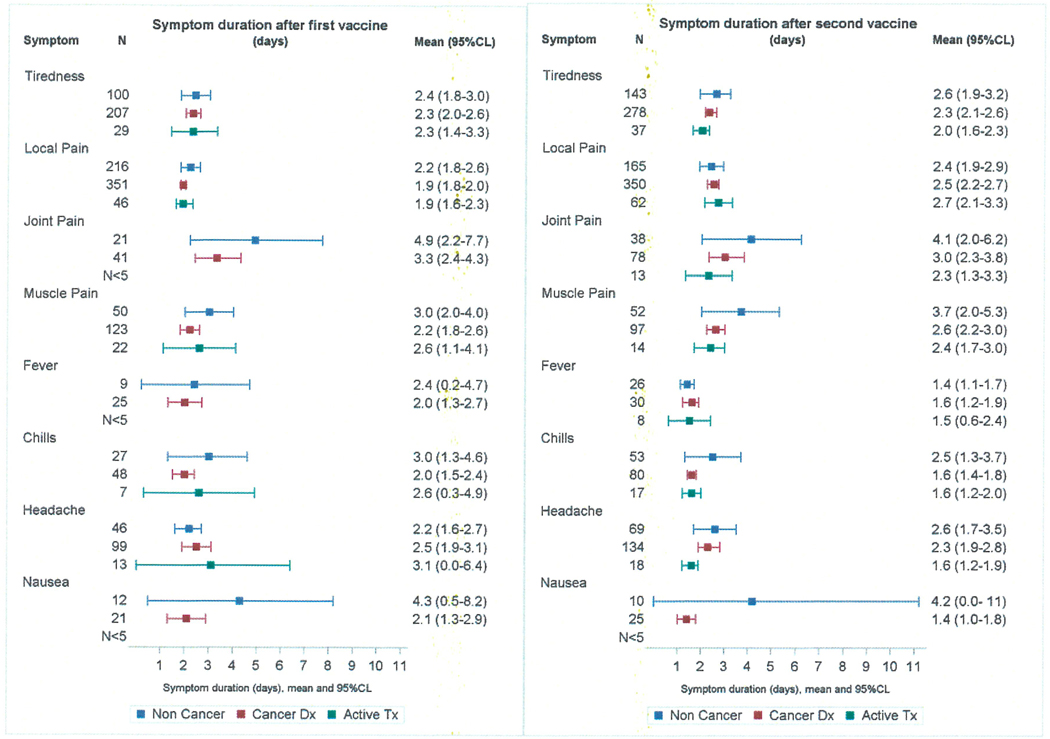

Local pain at the injection site was the most frequently reported symptom for all respondents and did not distinguish cancer patients from non-cancer patients after either dose 1 (39.3% vs 43.9%, p=0.07) or dose 2 (42.5% vs 40.3%, p=0.45). Muscle pain after the first vaccination was more frequent in cancer patients (16.5% vs 11.9%, p=0.012) but was of shorter duration (mean 2.2vs 3.0 days, p=0.04). Joint pain, headache, chills, nausea, and fever were unrelated to cancer status (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Frequency, onset and duration of adverse events following the first and second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine for non-cancer, cancer and active treatment patients

Data regarding onset and duration of symptoms were obtained for 84.2% of the cancer patients. Most patients reported their first symptom on the day of vaccination or the day after. The frequency of early symptom onset was the same for cancer patients not on active treatment and those on active treatment (83.2% vs 81.4%, p=0.63). Reports of any symptom lasting longer than 5 days were uncommon for both groups (10.2% vs 9.8%, p=0.90). Among cancer patients, those receiving active treatment were less likely to report pain at the injection site after dose 1 (30.0% vs 41.4%, p= 0.002). The side effect profile for actively treated cancer patients did not differ by treatment type either for dose 1 or dose 2.

Discussion:

This is the largest published study to date examining the short-term adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccination in cancer patients and the potential impact of active cancer treatment. As in previous reports, the most frequently reported side-effect of vaccination was pain at the site of injection. Systemic side-effects were generally more frequent after the second dose of vaccine, a pattern particularly noted for fatigue, joint pain, and chills. Of these systemic symptoms, the most commonly reported by cancer patients after the second vaccine dose were fatigue (33.9%), muscle pain (12.0%), and headache (16.0%). The comparable results in a recent study of vaccinated cancer patients on immunotherapy were fatigue 34%, muscle pain 34%, and headache 16%10--remarkably similar figures given the subjective nature of patient self-reports. Other systemic side effects in our study occurred with a frequency of less than 10%. When cancer patients were compared to cancer-free subjects, few differences were noted. Active cancer treatment similarly had little effect on side-effect profiles. The results can be summarized by observing that any group differences in symptoms reported in this study were not of a frequency or magnitude which would impose special precautions on clinics dispensing COVID-19 vaccine to cancer patients.

The current study addresses only the short-term side effects of COVID-19 vaccine in patients with cancer. Reassuringly, early reports suggest that the two-dose protocol of mRNA vaccine induces immunity in most cancer patients, including those on active immunotherapy.10-12 Future studies of vaccination involving cancer patients will need to address possible rare and long-term side effects in this population, assess the durability of the vaccine-mediated immune response, and determine the impact, if any, of the vaccine on cancer treatments. Furthermore, our study of unselected cancer patients seeking vaccination in an outpatient clinic did not produce a study population representative of cancer patients at large. Hematologic malignancies were underrepresented and relatively few patients were receiving active treatment. No conclusions could be drawn regarding cancer subgroups of particular interest, including those receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. The contribution of cell-mediated immunity to the anti-SARS-CoV-2 response is another subject of which little is known. This limitation assumes greater importance because immunity following vaccination is currently judged exclusively by serologic testing for antibody production.11 It is also important to note that our study population received only the mRNA Pfizer BNT162b2 vaccine. The alarm raised by the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted the development of numerous vaccine candidates requiring a variety of delivery strategies--including more than 180 vaccines still under clinical investigation.13 A future vaccine that utilizes an inactivated virus, for example, will require a fresh evaluation of its safety and efficacy in cancer patients.

Much of the harm wrought in patients with cancer by COVID-19 has not been the direct result of infection but has been inflicted indirectly by delayed diagnoses and suspended or aborted treatments.14 This harm is compounded for cancer patients who have refused vaccination. Our data, in combination with data from other sources, demonstrate that the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine is well tolerated by patients with a history of cancer, including those receiving active treatment. Adverse events occurring shortly after vaccination closely resemble those seen in cancer-free subjects. As noted, our vaccination program, which targeted a sizable population of patients in fragile health, encountered no obstacles of either an administrative or clinical nature to the timely delivery of the vaccine.

What explains vaccine hesitancy among cancer patients described in earlier studies? As already noted, media reports are an undoubted influence, especially when misleading or misinformed. The rate of vaccine refusal after an Italian regulatory agency suspended use of AstraZeneca52 AZD1222 for safety monitoring more than doubled, from 8.6% to 19.7%.9 An additional concern-perhaps even more alarming for the lasting damage it may cause--is self-defeating distrust of public health recommendations. The most effective remedy for this distrust is education. Widespread dissemination of results such as those reported in this study will ensure that a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine--justly celebrated as a scientific and medical triumph--is provided to the patients, including those with cancer, who stand to benefit from it most.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This publication was supported by grant number P30 CA006927 from the National Cancer Institute, NIH. Its contents are solely the responsibility pf the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of numerous people who enabled us to complete this study in the midst of the tremendous effort to vaccinate as many of our patients as possible as quickly as possible during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Staff throughout the Cancer Center volunteered countless hours caring for our patients and contributing to this study. We-would like to thank the Staff and Volunteers of the Fox Chase Covid Vaccine Clinic, Office of Clinical Research, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, the Volunteer Services Office and the Cancer Prevention & Control Program Staff. We would specifically like to thank the following people for their contributions to this project including Eileen Rall, AuD, Krisha Howell, MD, Sameera Kumar, MD, Chase Hansen, MD, MB, Jonathan Paly, DO, Marc Smaldone, MD, MS, Jennifer Higa, MD, Elizabeth Bourne, MD, Kristen Manley, MD, Alan Haber, MD, Usman Ali, MD, Kaitlyn Gregory, Max Lefton, Jason Castellanos, MD, MS, Elizabeth Allen, Hailan Liu, Stephan Donnelly, Marcel Knotek, Lisa Bealin, Nicole Ventriglia, Yana Chertok, Sarah Schober, Maria Market, Tanu Singh, PhD, Aidan Rhodes Pearigen, Kayla Elizabeth Alderfer, Joshua Stewart, Emma Price, Emily Ren, Stan Taylor, Helen Gordon, Judith Maxwell, Judy Owens, Linda Wishner, Marcia Black, Tania Danker, Elizabeth Brown, Karen Davis., Holly Kilpatrick, Karen Davis, April King, Denise Gibbs, Jennifer Reese, PhD, Lauren Zimmaro, PhD, Kristen Sorice, Folashade Adekunle, Andrew Belfiglio, Erin Tagai, PhD, Wanzi Yang, Yuku Chen, Colleen McKeown, Jessie Panick, Taylor Kazaoka, Minzi Li, Julia Zhong

REFERENCES

- 1.United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Public Health Service (PHS), Centers for Disease Control (CDC) / Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) 1990 – 07/09/2021, CDC WONDER On-line Database. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/vaers.html on July 20, 2021.

- 2.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Safety of COVID-19 vaccines. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/safety/safety-of-vaccines.html. Updated July 26,2021. Accessed Jul 20, 2021.

- 3.Desai A, Sachdeva S, Parekh T, Desai R. COVID-19 and Cancer: Lessons From a Pooled Meta-Analysis. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:557–559. doi: 10.1200/G0.20.00097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gosain R, Abdou Y, Singh A, Rana N, Puzanov I, Ernstoff MS. COVID-19 and cancer: a comprehensive review. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020;22(5):53. Published 2020 May 8. doi: 10.1007/s11912-020-00934-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hwang JK, Zhang T, Wang AZ, Li Z. COVID-19 vaccines for patients with cancer: benefits likely outweigh risks. J Hematol Oncol. 2021; 14(1 ):38. Published 2021 Feb 27. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01046-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monin L, Laing AG, Muñoz-Ruiz M, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of one versus two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b2 for patients with cancer: interim analysis of a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(6):765–778. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00213-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fanciullino R, Ciccolini J, Milano G. COVID-19 vaccine race: watch your step for cancer patients. BrJ Cancer. 2021;124(5):860–861. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01219-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Noia V, Renna D, Barberi V, et al. The first report on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine refusal by patients with solid cancer in Italy: Early data from a single-institute survey. European Journal of Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2021. Aug; 153:260–264. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waissengrin B, Agbarya A, Safadi E, Padova H, Wolf I. Short-term safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors [published correction appears in Lancet Oncol. 2021 Apr 30;:]. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5):581–583. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00155-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribas A, Sengupta R, Locke T, et al. Priority COVID-19 Vaccination for Patients with Cancer while Vaccine Supply Is Limited. Cancer Discov. 2021; 11(2):233–236. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curigliano G, Eggermont AMM. Adherence to COVID-19 Vaccines in Cancer Patients: Promote It and Make It Happen! European Journal of Cancer. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Krammer F. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in development. Nature 2020; 586:516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Lancet Oncology. COVID-19 and cancer: 1 year on. Lancet Oncol. 2021; 22(4):411. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00148-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]