Abstract

Oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) which contain immunostimulatory CG motifs (CpG ODN) can promote T helper 1 (Th1) responses, an adjuvant activity that is desirable for vaccination against leishmaniasis. To test this, susceptible BALB/c mice were vaccinated with soluble leishmanial antigen (SLA) with or without CpG ODN as adjuvant and then challenged with Leishmania major metacyclic promastigotes. CpG ODN alone gave partial protection when injected up to 5 weeks prior to infection, and longer if the ODN was bound to alum. To demonstrate an antigen-specific adjuvant effect, a minimum of 6 weeks between vaccination and infection was required. Subcutaneous administration of SLA alone, SLA plus alum, or SLA plus non-CpG ODN resulted in exacerbated disease compared to unvaccinated mice. Mice receiving SLA plus CpG ODN showed a highly significant (P < 5 × 10−5) reduction in swelling compared to SLA-vaccinated mice and enhanced survival compared to unvaccinated mice. The modulation of the response to SLA by CpG ODN was maintained even when mice were infected 6 months after vaccination. CpG ODN was not an effective adjuvant for antibody production in response to SLA unless given together with alum, when it promoted production of immunoglobulin G2a, a Th1-associated isotype. Our results suggest that with an appropriate antigen, CpG ODN would provide a stable, cost-effective adjuvant for use in vaccination against leishmaniasis.

Since the discovery of bacterial DNA as a sequence-specific immunostimulatory agent (31, 52), interest has been generated in the use of oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) as vaccine adjuvants. Specific DNA sequences involving an unmethylated CG dinucleotide (CpG motif) have been shown to directly activate B-cell proliferation and immunoglobulin (Ig) synthesis (22) and to promote macrophage/dendritic cell cytokine and major histocompatibility complex class II expression (5, 44, 46). DNA can induce the synthesis of cytokines such as interleukin-12 (IL-12), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and IL-6 from macrophages (5, 29, 45, 46) and in mixed spleen cell culture results in efficient induction of alpha/beta and gamma interferons (IFN-α/β and -γ) (5, 14, 52). The early IFN-γ produced in these cultures and in vivo in response to administered immunostimulatory DNA derives from natural killer cells stimulated by macrophage production of IL-12 and TNF-α (5, 14). IL-12 and IFN-γ are involved in development of T helper 1 (Th1)-polarized immune responses, and in earlier studies DNA has proved a promising adjuvant for promotion of Th1 responses (7, 11, 28, 37, 47, 50). The search for effective and safe Th1-promoting adjuvants is an active field, as most established vaccines use alum adjuvant, which results in a bias to Th2 responses characterized by IgG1 and IgE production and lack of specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (11). This is not desirable for the clearance of many parasitic and viral diseases which require cell-mediated rather than just humoral responses.

Stabilized CpG ODN (ODN containing immunostimulatory CG motifs) has been used as an adjuvant with a range of antigens (7, 11, 28, 37, 47, 50). It was found that CpG adjuvants induced higher levels of IgG2a (a Th1-promoted isotype) than complete Freund’s adjuvant (7, 47, 50) and were as effective as complete Freund’s adjuvant in tumor antigen immunization (50). Specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte production has also been shown when CpG ODN with alum or liposomes (11, 28) was used for adjuvant. The efficacy of DNA adjuvants has not yet been assessed in an infectious disease model.

Mouse models of infection with the protozoan parasite Leishmania major have helped define the Th1/Th2 model, as Th1-polarized responses are curative and Th2 responses exacerbate or are ineffective in controlling the disease (reviewed in references 23, 27, and 36). L. major replicates intracellularly in macrophages, and effective control requires macrophage activation and nitric oxide (NO)-mediated killing in response to the Th1-produced cytokine IFN-γ. BALB/c mice are susceptible to infection with L. major, and if allowed to run its course, subcutaneous injection of parasites leads to uncontrolled lesion growth and eventual death. Resistant mice such as CBA/Ca mice resolve lesions and heal within a few weeks. The specific defect in BALB/c mice has not been identified, but this difference in response of the mouse strains is due to a balance between effects of the Th1-promoting cytokine IL-12 and Th2 cytokine IL-4. BALB/c mice show an early peak of IL-4 production in draining lymph nodes by 1 day after infection, an effect not seen in resistant mice (24). This early IL-4 seems to determine the course of the infection, resulting in subsequent development of leishmania-specific CD4+ T cells along the Th2 pathway. Interestingly, the early IL-4 is uniquely produced by CD4+ cells expressing T-cell receptor chains Vβ4 and Vα8, which recognize the leishmanial LACK antigen (24), and prior tolerization of BALB/c mice to LACK make them resistant to L. major infection (18). Anti-IL-4 treatment or administration of IL-12 with infection can give BALB/c mice the ability to control the disease. The apparently straightforward role of IL-4 in promoting disease has been complicated by recent conflicting reports on disease progression in IL-4 knockout mice (21, 34). Other work has suggested that BALB/c CD4+ cells rapidly lose responsiveness to IL-12 during antigen-induced differentiation and thus have an inherent bias to the Th2 lineage (12).

Treatments and vaccinations which control the disease in susceptible mice invariably promote Th1 responses over Th2 responses. In human disease, there is also a trend of Th1 responses being involved in subclinical or curing disease and Th2 responses being involved in progressive disseminated disease (reviewed in reference 19). Vaccination strategies should clearly aim to produce Th1-promoting cytokines such as IL-12 at the time of cellular response to antigen. There is no generally used vaccine against leishmaniasis, although a number of human trials using killed leishmanial promastigotes with Mycobacterium bovis BCG are under way, and initial results show some protection (3). Vaccine approaches which have yielded various degrees of protection in mouse models of infection include DNA vaccination (13, 43, 49, 51), subcutaneous (s.c.) injection of low numbers of virulent L. major (4), use of Salmonella (30) or BCG (8) vectors expressing leishmanial antigen, antigen-containing liposomes (38), and ISCOMs (immunostimulatory complexes) (35), and use of IL-12 (2, 33) or Corynebacterium parvum (15, 40) as adjuvant. Conversion of the strong BALB/c Th2 response to a protective response is a stringent challenge for a vaccine, and most of these protocols gave only partial protection to BALB/c mice. Some of the most promising published results with methods potentially transferrable to human use are with DNA vaccination (13) and IL-12 adjuvant (2, 33). Early vaccinations with irradiated promastigotes showed protection (perhaps due to tolerization rather than vaccination [1]) with intraperitoneal and intravenous injections but exacerbation if administered s.c. (17, 26). Of these routes, intraperitoneal and intravenous are clearly not practical for human vaccination, but it now seems that with appropriate use of adjuvants, s.c. vaccination becomes possible (2). In this study, we have investigated the use of s.c.-injected immunostimulatory DNA as an adjuvant with crude leishmanial antigen in protection against L. major infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and materials.

Female BALB/c mice were obtained from Tuck Ltd. (Battlesbridge, England) or Charles River Ltd. (Margate, England), and female CBA/Ca were obtained from Harlan Olac Ltd. (Bicester, England). Phosphorothioate-linked ODN were obtained from either Genosys Biotechnologies (Pampisford, England) or Oligos Etc. (Wilsonville, Oreg.). CpG ODN used were AAC (ACC GAT AAC GTT GCC GGT GAC G) (46) and AO-1 (GCT CAT GAC GTT CCT GAT GCT G). The non-CpG ODN used was AAG (ACC GAT AAG CTT GCC GGT GAC G). DNA from Micrococcus lysodeikticus was from Sigma (Poole, England) and purified by phenol-chloroform extraction. IL-12 was from either Peprotech EC Ltd. (London, England) or R&D Systems (Abingdon, England).

Preparation of SLA.

Soluble leishmanial antigen (SLA) was prepared from log-phase L. major LV39 (MRHO/SU/59/P) by sonication and ultracentrifugation as described previously (40) except that α2-macroglobulin was omitted from the preparation.

Vaccinations.

Vaccines were prepared in phosphate-buffered saline and contained combinations of the following: 20 μg of SLA, 50 μg of oligonucleotide or bacterial DNA, 0.5 μg of IL-12, and 250 μg of aluminum hydroxide adjuvant (alum). Aluminum hydroxide gel was prepared by the method of Chace (6). SLA and DNA were bound directly to the alum by incubation for 30 min at room temperature. Micrococcal DNA was sheared by sonication and boiled to prevent clumping of the alum. The level of binding assessed by A260 and protein assays of supernatant was complete for protein and 95 to 99% for DNA. Seven- to eight-week-old mice were vaccinated twice at a 2-week interval s.c. in either the left footpad or the rump.

Infection of animals.

L. major LV39 log-phase promastigotes cryopreserved from the first passage after transformation from lesion-derived amastigotes were seeded at 106 cells/ml in high-glucose Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal calf serum and cultured for 11 to 14 days. Promastigotes harvested at this stage were >80% morphologically metacyclic, consistent with our experience with strain LV39, which transforms to >80% peanut agglutinin binding negative at 11 to 14 days of culture (9). Parasites (2 × 106) were injected into the right hind footpad 5 to 6.5 weeks after the second vaccination. Footpad swelling was measured, and mice were killed according to Home Office requirements when lesions showed the first signs of ulceration and before the onset of major visceral disease. Results for different groups were compared by unpaired, two-tailed Student t tests.

IgG isotype ELISAs.

Serum Ig isotypes were assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using 0.5 μg of bound SLA per well, isotype-specific secondary antibodies (biotinylated rabbit anti-mouse IgG2a or IgG1; Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, Calif.), and streptavidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase (Amersham, Little Chalfont, England). The most frequently used approach for comparing Ig levels is an endpoint dilution, the titer being determined by the last dilution at which activity is detectable. However, accuracy is compromised by serial dilutions and the inherent error in the low absorbance values toward the endpoint. Use of a standard serum has been suggested as a preferred alternative (42). Here, results from individual mouse samples were compared with a pooled standard serum prepared from infected mice vaccinated with alum-SLA-AAC. Using a standard curve of dilutions of this pooled serum in each experiment, we assessed the relative level of Ig in a dilution of individual samples. The results obtained are therefore expressed as Ig isotype level relative to the pooled standard. To enable the best comparison, appropriate dilutions of each sample giving values on the steepest part of the standard curve were used. This technique for comparing Ig levels depends on the assumption that the shape of the dilution curve is similar for each sample, and from titrations of various samples this seemed a reasonable assumption. The standard had high detectable levels of IgG2a and IgG1, both with a titer of 105, so that graphs give an indication of levels of the two isotypes relative to one another, assuming that detection is equally efficient with the two isotype-specific antibodies.

Nitrite assay.

A nitrite assay was used as an indication of NO production by RAW264, a murine macrophage line, as described previously (48).

RESULTS

Immunostimulatory ODN modulate L. major infection.

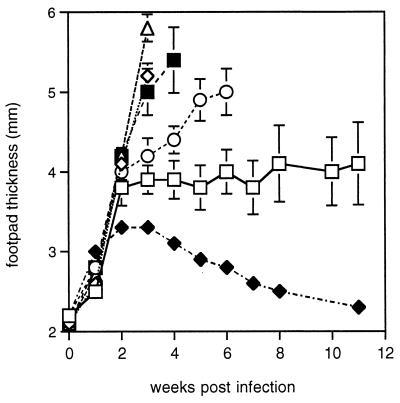

To check the efficacy of phosphorothioate-stabilized CpG ODN as an adjuvant with L. major SLA as antigen, footpad swelling in mice vaccinated with SLA plus CpG ODN was compared with that in unvaccinated controls (Fig. 1). A significant difference was observed at 3 (P < 0.01) and 4 (P < 0.005) weeks postinfection. Improved survival was also observed, with all of five vaccinated mice surviving until week 11 and three of five remaining healthy at week 17, whereas five of six unvaccinated mice had to be killed between weeks 4 and 6. However, injection of CpG ODN alone also gave some protection (P < 0.05) from footpad swelling at 3 and 4 weeks compared with control unvaccinated mice, although footpads continued to swell and three of five mice had to be killed in week 6. Since there was no antigen in this preparation this is likely to be due to lingering traces of the ODN directly activating antigen presentation and macrophages for parasite killing. Previous work has shown CpG ODN themselves protect from and are therapeutic in L. major infection (53). In the experiment here, mice were left for 5 weeks between the last vaccination and challenge infection, indicating that the protective effect of ODN can be long-lived.

FIG. 1.

Lesion sizes in vaccinated mice challenged with L. major. BALB/c mice were injected with indicated vaccine preparations in the left footpad, followed 2 weeks later by injection s.c. in the rump; 5 weeks later, these mice and resistant CBA/Ca mice were infected in the right footpad with 2 × 106 L. major promastigotes, and footpad swelling was monitored weekly. The mean and standard error of measurements from groups of five or six (control group only) mice are shown up to the time when the first mouse from that group had to be killed. Treatments: □, SLA plus CpG ODN (AAC); ◊, SLA plus non-CpG ODN; ○, CpG ODN; ▵, SLA; ■, control unvaccinated mice; ⧫, resistant CBA/Ca mice.

SLA alone had an exacerbatory effect on disease progression. A comparison of SLA-vaccinated and SLA-CpG ODN-vaccinated mice (Fig. 1) shows the dramatic modifying role of the ODN on the immune response to antigen (P < 0.00005 at week 3). The DNA sequence specificity for this immunomodulation is shown by the lack of protection by vaccination with SLA plus non-CpG ODN, an inactive ODN with the active sequence AACGTT changed to AAGCTT.

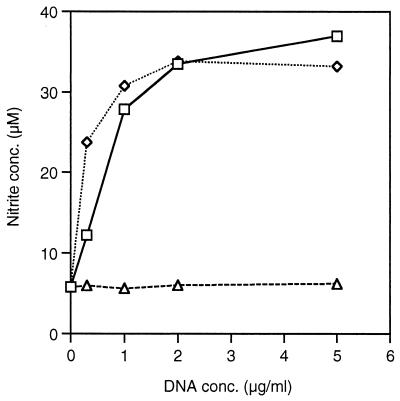

Other potential adjuvants investigated in combination with SLA were IL-12 and micrococcal DNA. Both of these treatments exacerbated the disease in the same way as SLA alone (result not shown). The failure of bacterial DNA to behave as an adjuvant may be due to more rapid breakdown in vivo. The bacterial DNA is clearly immunologically active, as in an in vitro assay of NO production by a macrophage cell line, micrococcal DNA was only slightly less potent than CpG ODN (Fig. 2). In a second assay, the differences at low DNA concentration were not so marked (result not shown). SLA–IL-12 is published as a protective vaccination (2) and had been included as a positive control. Reasons considered for its failure to work here include rapid degradation or that 0.5 μg of IL-12 per vaccination was an insufficient dose.

FIG. 2.

Measurement of nitrite as an indication of NO produced by RAW264 cells in response to DNA. Cells were incubated with IFN-γ (40 U/ml) for 1 h before various concentrations of DNA were added for 24 h. DNAs used: □, DNA from M. lysodeikticus; ◊, CpG ODN (AAC); ▵, non-CpG ODN (AAG). Results are the average of nitrite concentration in triplicate wells.

Confirmation of the adjuvant effect of oligonucleotides in vaccination against L. major.

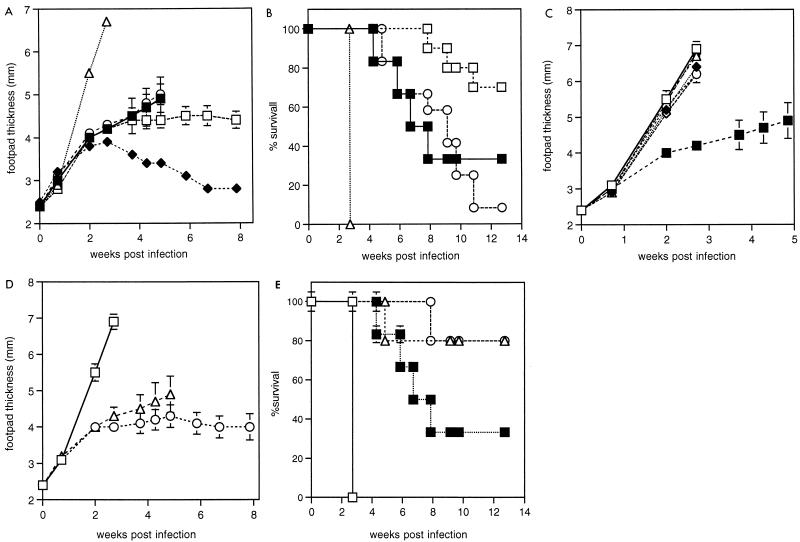

To avoid the problem of macrophage activation by traces of CpG ODN remaining at the time of infection, further experiments were performed, leaving greater intervals between vaccination and challenge infection. An interval of 6 weeks between vaccination and infection eliminated any protective effect of CpG ODN alone (Fig. 3A and B). A dramatic effect of oligonucleotide was observed in modifying the response to SLA vaccination (Fig. 3A). In this experiment, SLA alone had a highly significant exacerbatory effect on footpad swelling compared to unvaccinated animals (P < 10−6 at week 3) or animals vaccinated with SLA plus CpG ODN (P < 10−7 at week 3). At the time when the first unvaccinated animals had to be killed at week 5 of infection, there was no significant difference between the unvaccinated mice and those which received SLA plus CpG ODN (Fig. 3A). The response of unvaccinated control mice was variable, with two of six mice failing to swell above 4-mm footpad depth after 9 weeks of infection. However, analysis of the times at which mice had to be killed indicates a protective effect for SLA plus CpG ODN over unvaccinated mice (Fig. 3B). In a repeat experiment with groups of 10 mice, a similar result was obtained: survival of mice was improved by SLA-CpG ODN treatment, but again the variability in control mice meant that no statistical difference in footpad thickness was observed before the first mice had to be killed.

FIG. 3.

Lesion sizes and survival of vaccinated mice challenged with L. major. BALB/c mice were injected in the left footpad with the indicated vaccine preparations, followed 2 weeks later by injection s.c. in the rump; 6.3 weeks later, these mice and resistant CBA/Ca were infected in the right footpad with 2 × 106 L. major promastigotes. All groups contained five mice except for control (six mice) SLA-CpG ODN (10 mice), and CpG ODN-alone (12 mice) groups. Results from groups of mice treated with either of the CpG ODNs AAC and AO-1 were indistinguishable and were combined to give SLA-CpG ODN and CpG ODN groups in order to simplify the graphs and improve statistical power. For footpad measurements, results show the mean and standard error up to the time when the first mouse had to be killed. Mice were killed according to Home Office guidelines when lesions began to ulcerate. (A) Footpad sizes of infected mice in the weeks following infection. Treatments: □, SLA plus CpG ODN; ○, CpG ODN; ▵, SLA; ■, control unvaccinated mice; ⧫, resistant CBA/Ca mice. (B) Survival of infected animals. Treatments were as for panel A. (C) Footpad sizes of mice receiving vaccinations which exacerbated infection. Treatments: ▵, SLA; ◊, SLA plus non-CpG ODN; ⧫, SLA plus micrococcal DNA; □, SLA plus alum; ●, SLA plus alum and micrococcal DNA; ○, SLA plus IL-12; ■, control unvaccinated mice. (D) Footpad sizes of mice treated with SLA plus alum (□) or SLA plus alum and CpG ODN (AAC) (▵) or alum and CpG ODN (AAC) (○). (E) Survival of mice treated as for panel D and of control unvaccinated mice (■).

A lack of adjuvant effect of non-CpG ODN and micrococcal DNA was confirmed in this experiment (Fig. 3C). As anticipated from the known Th2 promotion by alum (11), SLA-alum was exacerbatory (Fig. 3C). An attempt was made to stabilize the micrococcal DNA and allow a response by binding it to alum. Any stabilization afforded by alum binding was not sufficient to give a protective response or could not overcome the promotion of Th2 responses by alum (Fig. 3C). Despite including the protease inhibitor α2-macroglobulin in the SLA for the SLA–IL-12 sample as detailed in the original published method (2, 40), again no effect of IL-12 on the response to SLA was observed.

Previous work had suggested that a combination of alum and CpG ODN gives both CTL production and high antibody titers (11). We tried this and found a great effect compared to SLA alone or SLA plus alum in both footpad swelling and survival (Fig. 3D and E). Survival was also greater than for unvaccinated mice (Fig. 3E). However, the success of this treatment is not necessarily due to effective vaccination, as mice injected with alum plus CpG ODN alone showed similar footpad and survival characteristics (Fig. 3D and E). The alum may have stabilized the CpG ODN in vivo. Footpad measurements for the alum-SLA-CpG ODN group were skewed by one mouse which progressed rapidly and had to be killed in week 5.

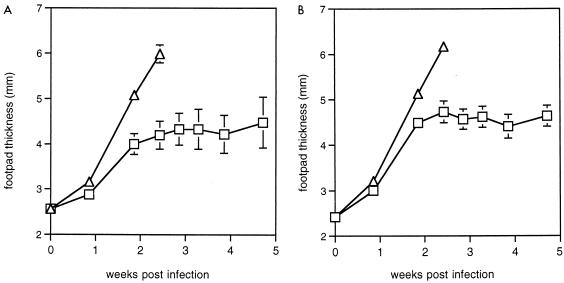

The effects of SLA and SLA-CpG ODN vaccinations are long-lived.

To assess the longevity of the immunological memory response induced by SLA or SLA plus CpG ODN, mice which had been vaccinated 6 months previously were infected with L. major and footpad swelling was monitored over 5 weeks. For 6-month vaccinated mice, we observed a modification by CpG ODN of the effect of SLA (Fig. 4A) similar to that observed in animals vaccinated 6 weeks previously (Fig. 4B), indicating that the memory T-cell response elicited by SLA and SLA plus CpG ODN is long-lived.

FIG. 4.

Lesion sizes in mice challenged with L. major at 6 weeks and 6 months after vaccination. Treatments: ▵, SLA; □, SLA plus CpG ODN (AAC). Results shown are the mean and standard error of footpad measurements. (A) Groups of three BALB/c mice were vaccinated as for Fig. 3. Six months later, they were infected in the right footpad with 2 × 106 L. major promastigotes, and footpad size was monitored in the weeks following infection. (B) Groups of 9 (SLA plus CpG ODN) or 10 (SLA) BALB/c mice were vaccinated twice s.c. in the rump at a 2-week interval; 6.5 weeks later, they were infected in the right footpad at the same time as the mice used for panel A.

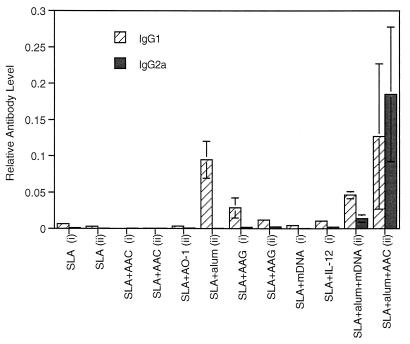

Postvaccination antibody subclass responses to SLA.

To compare IgG isotypes in protective and nonprotective vaccinations, sera collected 4 weeks after the second vaccination were assessed for IgG1 and IgG2a. Figure 5 shows the results for vaccinated mice from the experiments presented in Fig. 1 and 2. Despite having clearly had a profound effect on the response to infection, SLA-AAC (CpG ODN) gave little detectable IgG1 or IgG2a (Fig. 5) or indeed total IgG (result not shown). As expected (11), reasonable levels of IgG1 production and no IgG2a were obtained with alum as adjuvant. SLA-AAG (non-CpG ODN) produced more antibody than SLA-AAC (CpG ODN) and may have had a slight adjuvant effect above the effect of SLA alone. Immunostimulatory effects such as B-cell proliferation and splenomegaly have been observed in response to non-CpG ODN before (11, 32) and seem to be a non-sequence-specific response to the phosphorothioate ODN. The nonprotective treatments SLA-micrococcal DNA and SLA–IL-12 gave no significant boost in antibodies above SLA alone. SLA-alum-micrococcal DNA showed a significant effect of the DNA compared to SLA-alum treatment (P < 0.05 for IgG2a). The ratio between IgG1 and IgG2a is decreased, suggesting a shift toward a Th1 response (Fig. 5), but this was clearly insufficient to affect on the outcome of infection (Fig. 3C). The only treatment to give high levels (although highly variable between mice) of both IgG1 and IgG2a was SLA-alum-AAC. In summary, there was a surprising lack of adjuvant effect of CpG ODN alone on antibody production in response to SLA. The ability of ODN to affect the humoral immune response was, however, shown in combination with alum, where it caused a major shift toward IgG2a production.

FIG. 5.

Relative anti-SLA IgG1 and IgG2a levels in vaccinated mice from two experiments (i and ii). Mice were bled 4 weeks after the second vaccination. Antibody levels are expressed relative to a standard pool (see Materials and Methods). Mean and standard error of Ig levels measured in duplicate on at least five animals per group are shown. DNAs used are CpG ODNs (AAC and AO-1), non-CpG ODN (AAG), and micrococcal DNA (mDNA).

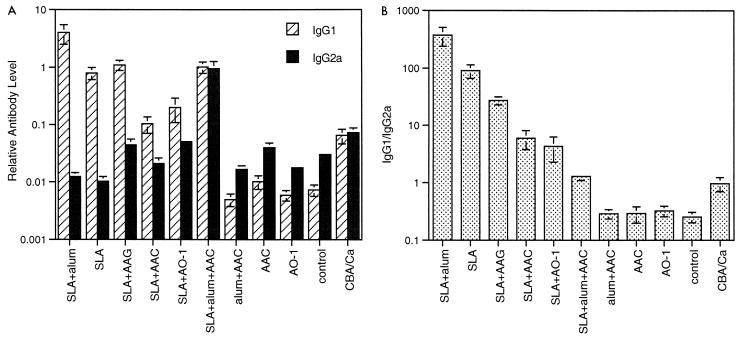

Immunological correlates of disease protection versus exacerbation.

Levels of antibody were assessed in infected animals from the experiment presented in Fig. 3 as a measure of Th1 versus Th2 bias during the course of the disease. Figure 6A shows up to 1,000-fold differences in IgG1 levels and 100-fold differences in IgG2a levels between treatment groups. The absolute level of IgG2a, a Th1 marker, was not related to disease progression. In particular, SLA-AAG (non-CpG ODN), which was disease exacerbatory, had a relatively high IgG2a level, similar to that in the resistant CBA/Ca mice. However, the ratio of IgG1 to 2a showed some correlation with disease progression. As shown in Fig. 6B, high ratios (30 to 500) were associated with exacerbation, and moderate ratios (1 to 7) were associated with some protection. The resistant CBA/Ca mice also fell within this range. Interestingly, all BALB/c mice which had not been exposed to SLA had lower overall antibody levels but a higher proportion of IgG2a. These included mice which showed no difference to control (AAC and AO-1 treatments) but also the alum-AAC (CpG ODN) treatment group, which showed enhanced survival. Thus, the ratio for mice unexposed to SLA was not a good indicator of disease state. The assumed stability of ODN in the alum-AAC treatment does not appear to have altered the humoral response to infection but may still have been acting directly on macrophages to enhance killing or bias Th cell development. A repeat experiment with groups of 10 mice treated with SLA, CpG ODN, and SLA plus CpG ODN and control mice gave very similar results and IgG ratios to those presented here.

FIG. 6.

Relative anti-SLA IgG1 and IgG2a levels in infected mice from the experiment in Fig. 3. Mice were bled 2.5 weeks after infection. Results shown are mean and standard error of Ig levels measured in duplicate on at least five animals per group. DNAs used were CpG ODNs (AAC and AO-1) and non-CpG ODN (AAG). (A) Antibody levels expressed relative to a standard pool (see Materials and Methods). (B) Ratio of anti-SLA IgG1 to IgG2a.

DISCUSSION

Previous work has demonstrated that immunostimulatory DNA promotes Th1 responses (7, 11, 37, 53), an adjuvant activity that would be desirable for vaccination against leishmaniasis. Results presented here demonstrate that coinjection of immunostimulatory phosphorothiorate-modified ODN as adjuvant with a crude soluble leishmanial antigen preparation modulates leishmania-specific immunity toward a protective immune response. During the course of these experiments, we made several important observations which contribute to our understanding of the requirements for successful immune interventions against leishmaniasis and to the use of BALB/c mice as a model system.

First, we were able to demonstrate that immunostimulatory ODN alone could modulate leishmanial infection even when injected up to 5 weeks prior to challenge infection, and longer if the ODN was bound to alum. This effect is consistent with previous studies showing CpG ODN to be a very effective treatment for cutaneous leishmaniasis when administered at the time of infection or up to 20 days after infection (53). In these studies, an established Th2 response in infected mice could be converted by CpG ODN administration to a Th1-driven response associated with persistent IL-12 receptor β2-chain expression. ODN will probably also contribute directly to parasite killing, as studies demonstrate that DNA activation of macrophages leads to TNF-α and NO production (45, 46, 48). Whatever the mechanism, our data support the therapeutic potential of CpG ODN in the treatment of intramacrophage pathogens.

To dissociate the nonspecific effect of ODN from leishmania-specific adjuvant activity, we had to wait at least 6 weeks between the last vaccination and challenge infection. Under these conditions, we observed a protective effect of vaccination with SLA and ODN on the length of time before animals developed ulcerating lesions and had to be killed. The response of unvaccinated BALB/c mice to infection in these experiments was variable, and possible reasons for this are considered below. This meant that in some experiments it was not possible to confirm a protective effect of vaccination on footpad size before the first mice in the control group had to be killed. However, in no case did vaccination make lesions resolve like those of the resistant CBA/Ca mice. Rather, in protected animals, the footpads remained slightly swollen in a stable manner for periods of months.

ODN had an unequivocally impressive effect in modulating the response to vaccination with SLA. Administration of SLA alone or with alum, bacterial DNA, IL-12, or non-CpG ODN made the mice uniformly susceptible, with rapid swelling and a necessity to kill all mice in week 3 of infection. Early studies of vaccination using irradiated promastigotes found that s.c. injection exacerbated disease compared to controls (26). However, a more recent study using SLA injected s.c. and intradermally found no exacerbation (2). Exacerbation by SLA in the absence of any Th1-promoting adjuvant is not surprising in BALB/c mice, since they have an inherent tendency to develop Th2 responses. The difference between our results and those of Afonso et al. (2) may relate to conditions of animal housing and exposure to environmental antigens as discussed below or to differences in preparation of SLA and vaccination schedule. It will be important to establish whether exacerbation can be avoided with more purified protein fractions, as it is a difficult task for a vaccine adjuvant to overcome such a powerful negative effect of antigen alone. Nevertheless, the modulation of this response to SLA by active ODN in all mice tested shows the power of these DNA molecules as immunomodulators.

In the experiments performed here, the unvaccinated BALB/c mice seemed to be teetering on the balance point between resistance and susceptibility. Twenty to 30% of unvaccinated control footpads failed to swell above 4 mm, and these mice remained healthy until the end of the experiment at 13 weeks. In others, the infection progressed rapidly and mice with footpads measuring 6 mm had to be killed in week 5. Since BALB/c resistance can be established with low doses of parasites (4), one interpretation is that our parasites were insufficiently infective. However, this seems unlikely since in many mice the disease progressed rapidly. It is possible that a variable proportion of nonmetacyclic parasites in our inoculum contributed to the local inflammatory response initiated at the site of infection, since it is well established that noninfective logarithmic-phase parasites elicit a strong macrophage activation response, whereas metacyclic parasites enter macrophages silently (10). However this is a factor that is likely to vary between and not within experiments. Another explanation for variability in the BALB/c mouse response to infection may lie in the basis to their susceptibility. As discussed earlier, the BALB/c response to the leishmanial LACK antigen seems critical in the early production of IL-4 and subsequent susceptibility (24). The possibility exists that the dominance of the LACK antigen in BALB/c mice is a consequence of preexpansion of LACK-reactive T cells in response to a cross-reactive environmental or gut flora antigen. If this is the case, there could be variable priming with the putative environmental antigen and thus a variable susceptibility of BALB/c mice to infection.

Vaccination with SLA plus ODN clearly had a profound effect on immune response to SLA but did not result in antibody production. Production of antibodies is not of concern for leishmanial vaccine development, as antibody plays little or no role in defense against leishmania (16). Other studies have also documented protective antileishmanial vaccination without antibody production (39, 43). The finding of so little induction of antibody by oligonucleotide adjuvant was surprising, as in most previous studies using oligonucleotide with antigens such as hepatitis B surface antigen, fowl gamma globulin, or a tumor antigen, antibody production with a bias toward the Th1 cytokine-induced subtype, IgG2a, was readily detectable (11, 47, 50). This finding suggests that the lack of antibody production here may be in some way due to the crude leishmanial extract used as antigen. Whether SLA contains molecules which specifically inhibit the humoral response under the cytokine conditions promoted by CpG ODN has not been investigated. Although in other work SLA with C. parvum adjuvant did induce a humoral response, sera from vaccinated mice surprisingly precipitated only two leishmanial proteins (40). Fractionation of SLA by ion-exchange chromatography identified only one protective fraction out of nine, and immunization with this fraction did not induce antibody production (39). Only vaccinations which included alum induced large amounts of antibody. Alum with SLA, as expected, gave a large amount of IgG1 and no IgG2a. Inclusion of active ODN in this preparation had a profound effect on antibody production, leading to high levels of both IgG1 and IgG2a. Thus, it seems that alum and not ODN promoted the general ability to make antibody in response to SLA, but in the presence of alum, Th1 cytokines induced by ODN promoted class switching to IgG2a. A combination of alum and CpG ODN as adjuvant may be useful when both humoral and cell-mediated immunity are desired.

After infection, absolute levels of antibody bore no relationship to the progress of disease, but in mice vaccinated with SLA and various adjuvants, high ratios of IgG1 to 2a, suggestive of Th2 processes, correlated with exacerbated disease. The ratio was not predictive for mice which had not received SLA, as susceptible BALB/c control mice had a lower IgG1/IgG2a ratio than the resistant CBA/Ca. This contrasts with a report by Bretscher et al. (4), who determined by immunoblot analysis that BALB/c mice had readily detectable IgG1 and almost no IgG2a 1 month after infection with 106 L. major parasites. This may be yet another manifestation of the incomplete susceptibility of the BALB/c control mice observed in these experiments.

Our experiments failed to show an adjuvant effect of IL-12. In initial experiments using IL-12 as adjuvant (2), 1 μg of IL-12 was used in vaccinations, but the authors noted similar effects of vaccinations with SLA plus 1 μg and SLA plus 0.1 μg of IL-12 on lymph node cell IFN-γ induction and IL-4 suppression. Therefore, we considered that 0.5 μg would be an adequate dose, but this may not have been the case. Although IL-12 has been a successful adjuvant promoting cell-mediated immunity to a number of antigens (41), the cost of producing a recombinant cytokine will probably remain too high for general inclusion in adjuvants, particularly for diseases in developing countries. In addition, storage of vaccines containing temperature-sensitive components may be challenging in isolated tropical areas. Published results for recombinant IL-12 as adjuvant should encourage the search for vaccination strategies which enhance the body’s own production of IL-12 and other Th1-promoting cytokines. Our results contribute to the promising emerging role for ODN adjuvants and DNA vaccination, both of which depend on macrophage/antigen-presenting cell recognition of foreign DNA sequences, induce a range of Th1-promoting cytokines (20, 25, 29) and are conveniently stable under field conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

K. Stacey was supported by fellowship 967351 from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aebischer T, Morris L, Handman E. Intravenous injection of irradiated Leishmania major into susceptible BALB/c mice: immunization or protective tolerance. Int Immunol. 1994;6:1535–1543. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.10.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afonso L C, Scharton T M, Vieira L Q, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Scott P. The adjuvant effect of interleukin-12 in a vaccine against Leishmania major. Science. 1994;263:235–237. doi: 10.1126/science.7904381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armijos R X, Weigel M M, Aviles H, Maldonado R, Racines J. Field trial of a vaccine against New World cutaneous leishmaniasis in an at-risk child population: safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy during the first 12 months of follow-up. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1352–1357. doi: 10.1086/515265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bretscher P A, Wei G, Menon J N, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H. Establishment of stable, cell-mediated immunity that makes “susceptible” mice resistant to Leishmania major. Science. 1992;257:539–542. doi: 10.1126/science.1636090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chace J H, Hooker N A, Mildenstein K L, Krieg A M, Cowdery J S. Bacterial DNA-induced NK cell IFN-γ production is dependent on macrophage secretion of IL-12. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;84:185–193. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chace M W. Production of antiserum. Methods Immunol Immunochem. 1967;1:197–209. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu R S, Targoni O S, Krieg A M, Lehmann P V, Harding C V. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides act as adjuvants that switch on T helper 1 (Th1) immunity. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1623–1631. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connell N D, Medina-Acosta E, McMaster W R, Bloom B R, Russell D G. Effective immunization against cutaneous leishmaniasis with recombinant bacille Calmette-Guerin expressing the Leishmania surface proteinase gp63. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11473–11477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper A M, Rosen H, Blackwell J M. Monoclonal antibodies that recognise distinct epitopes of the macrophage type three complement receptor differ in their ability to inhibit binding of Leishmania promastigotes harvested at different phases of their growth cycle. Immunology. 1988;65:511–514. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Da Silva R P, Hall B F, Joiner K A, Sacks D L. CR1, the C3b receptor, mediates binding of infective Leishmania major metacyclic promastigotes to human macrophages. J Immunol. 1989;143:617–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis H L, Weeranta R, Waldshmidt T J, Tygrett L, Schorr J, Krieg A M. CpG DNA is a potent enhancer of specific immunity in mice immunized with recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen. J Immunol. 1998;160:870–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Güler M L, Gorham J D, Hsieh C-S, Mackey A J, Steen R G, Dietrich W F, Murphy K M. Genetic susceptibility to Leishmania: IL-12 responsiveness in TH1 cell development. Science. 1996;271:984–986. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurunathan S, Sacks D L, Brown D R, Reiner S L, Charest H, Glaichenhaus N, Seder R A. Vaccination with DNA encoding the immunodominant LACK parasite antigen confers protective immunity to mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1137–1147. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halpern M D, Kurlander R J, Pisetsky D S. Bacterial DNA induces murine interferon-γ production by stimulation of interleukin-12 and tumour necrosis factor-α. Cell Immunol. 1996;167:72–78. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Handman E, Symons F M, Baldwin T M, Curtis J M, Scheerlinck J P. Protective vaccination with promastigote surface antigen 2 from Leishmania major is mediated by a TH1 type of immune response. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4261–4267. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4261-4267.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howard J G, Liew F Y, Hale C, Nicklin S. Prophylactic immunization against experimental leishmaniasis. II. Further characterization of the protective immunity against fatal Leishmania tropica infection induced by irradiated promastigotes. J Immunol. 1984;132:450–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard J G, Nicklin S, Hale C, Liew F Y. Prophylactic immunization against experimental leishmaniasis. I. Protection induced in mice genetically vulnerable to fatal Leishmania tropica infection. J Immunol. 1982;129:2206–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Julia V, Rassoulzadegan M, Glaichenhaus N. Resistance to Leishmania major induced by tolerance to a single antigen. Science. 1996;274:421–423. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5286.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kemp M, Theander T, Kharazmi A. The contrasting roles of CD4+ T cells in intracellular infections in humans: leishmaniasis as an example. Immunol Today. 1996;17:13–16. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80562-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klinman D M, Yamshchikov G, Ishigatsubo Y. Contribution of CpG motifs to the immunogenicity of DNA vaccines. J Immunol. 1997;158:3635–3639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kopf M, Brombacher F, Köhler G, Kienzle G, Widmann K-H, Lefrang K, Humborg C, Ledermann B, Solbach W. IL-4-deficient Balb/c mice resist infection with Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1127–1136. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krieg A M, Yi A-K, Matson S, Waldschmidt T J, Bishop G A, Teasdale R, Koretzky G A, Klinman D M. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA trigger direct B-cell activation. Nature. 1995;374:546–549. doi: 10.1038/374546a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Launois P, Conceiçao-Silva F, Himmerlich H, Parra-Lopez C, Tacchini-Cottier F, Louis J A. Setting in motion the immune mechanisms underlying genetically determined resistance and susceptibility to infection with Leishmania major. Parasite Immunol. 1998;20:223–230. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1998.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Launois P, Maillard I, Pingel S, Swihart K G, Xénarios I, Acha-Orbea H, Diggelmann H, Locksley R M, Robson MacDonald H, Louis J A. IL-4 rapidly produced by Vβ4 Vα8 CD4+ T cells instructs Th2 development and susceptibility to Leishmania major in BALB/c mice. Immunity. 1997;6:541–549. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80342-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leclerc C, Dériaud E, Rojas M, Whalen R G. The preferential induction of a Th1 immune response by DNA-based immunization is mediated by the immunostimulatory effect of plasmid DNA. Cell Immunol. 1997;179:97–106. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1997.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liew F Y, Hale C, Howard J G. Prophylactic immunization against experimental leishmaniasis. IV. Subcutaneous immunization prevents induction of protective immunity against fatal Leishmania major infection. J Immunol. 1985;135:2095–2101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liew F Y, O’Donnell C A. Immunology of leishmaniasis. Adv Parasitol. 1993;32:161–259. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipford G B, Bauer M, Blank C, Reiter R, Wagner H, Heeg K. CpG-containing synthetic oligonucleotides promote B and cytotoxic T cell responses to protein antigen: a new class of vaccine adjuvants. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2340–2344. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipford G B, Sparwasser T, Bauer M, Zimmerman S, Koch E-S, Heeg K, Wagner H. Immunostimulatory DNA: sequence-dependent production of potentially harmful or useful cytokines. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:3420–3426. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McSorley S J, Xu D, Liew F Y. Vaccine efficacy of Salmonella strains expressing glycoprotein 63 with different promoters. Infect Immun. 1997;65:171–178. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.171-178.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Messina J P, Gilkeson G S, Pisetsky D A. Stimulation of in vitro murine lymphocyte proliferation by bacterial DNA. J Immunol. 1991;147:1759–1764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monteith D K, Henry S P, Howard R B, Flournoy S, Levin A A, Bennett C F, Crooke S T. Immune stimulation: a class effect of phosphorothioate oligodeoxynucleotides in rodents. Anticancer Drug Des. 1997;12:421–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mougneau E, Altare F, Wakil A E, Zheng S, Coppola T, Wang Z E, Waldmann R, Locksley R M, Glaichenhaus N. Expression cloning of a protective Leishmania antigen. Science. 1995;268:563–566. doi: 10.1126/science.7725103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noben-Trauth N, Kropf P, Müller I. Susceptibility to Leishmania major infection in interleukin-4-deficient mice. Science. 1996;271:987–990. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papadopoulou G, Karagouni E, Dotsika E. ISCOMs vaccine against experimental leishmaniasis. Vaccine. 1998;16:885–892. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reiner S L, Locksley R M. The regulation of immunity to Leishmania major. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:151–177. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roman M, Martin-Orozco E, Goodman J S, Nguyen M-D, Sato Y, Ronaghy A, Kornbluth R S, Richman D D, Carson D A, Raz E. Immunostimulatory DNA sequences function as T helper-1 promoting adjuvants. Nat Med. 1997;3:849–854. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell D G, Alexander J. Effective immunization against cutaneous leishmaniasis with defined membrane antigens reconstituted into liposomes. J Immunol. 1988;140:1274–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scott P, Pearce E, Natovitz P, Sher A. Vaccination against cutaneous leishmaniasis in a murine model. II. Immunologic properties of protective and nonprotective subfractions of a soluble promastigote extract. J Immunol. 1987;139:3118–3125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott P, Pearce E, Natovitz P, Sher A. Vaccination against cutaneous leishmaniasis in a murine model. I. Induction of protective immunity with a soluble extract of promastigotes. J Immunol. 1987;139:221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scott P, Trinchieri G. IL-12 as an adjuvant for cell-mediated immunity. Semin Immunol. 1997;9:285–291. doi: 10.1006/smim.1997.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seppala I J T, Makela O. Quantification of antibodies. In: Herzenberg L A, Weir D M, Herzenberg L A, Blackwell C, editors. Weir’s handbook of experimental immunology. 5th ed. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Science Inc.; 1996. pp. 44.1–44.5. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sjölander A, Baldwin T M, Curtis J M, Handman E. Induction of a Th1 immune response and simultaneous lack of activation of a Th2 response are required for generation of immunity to leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1998;160:3949–3957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sparwasser T, Koch E S, Vabulas R M, Heeg K, Lipford G B, Ellwart J W, Wagner H. Bacterial DNA and immunostimulatory CpG oligonucleotides trigger maturation and activation of murine dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2045–2054. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199806)28:06<2045::AID-IMMU2045>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sparwasser T, Miethke T, Lipford G, Erdmann A, Häcker H, Heeg K, Wagner H. Macrophages sense pathogens via DNA motifs: induction of tumor necrosis factor. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1671–1679. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stacey K J, Sweet M, Hume D A. Macrophages ingest and are activated by bacterial DNA. J Immunol. 1996;157:2116–2122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun S, Kishimoto H, Sprent J. DNA as an adjuvant: capacity of insect DNA and synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides to augment T cell responses to specific antigen. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1145–1150. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sweet M J, Stacey K J, Kakuda D K, Markovich D, Hume D A. IFN-γ primes macrophage responses to bacterial DNA. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1998;18:263–271. doi: 10.1089/jir.1998.18.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walker P S, Scharton-Kersten T, Rowton E D, Hengge U, Bouloc A, Udey M C, Vogel J C. Genetic immunization with glycoprotein 63 cDNA results in a helper T cell type 1 immune response and protection in a murine model of leishmaniasis. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:1899–1907. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.13-1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weiner G J, Liu H-M, Wooldridge J E, Dahle C E, Krieg A M. Immunostimulatory oligodeoxynucleotides containing the CpG motif are effective as immune adjuvants in tumor antigen immunization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10833–10837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu D, Liew F Y. Protection against leishmaniasis by injection of DNA encoding a major surface glycoprotein, gp63, of L. major. Immunology. 1995;84:173–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamamoto S, Kuramoto E, Shimada S, Tokunaga T. In vitro augmentation of natural killer cell activity and production of interferon-α/β and -γ with deoxyribonucleic acid fraction from Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1988;79:866–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1988.tb00049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zimmermann S, Egeter O, Hausmann S, Lipford G B, Röcken M, Wagner H, Heeg K. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides trigger protective and curative Th1 responses in lethal murine leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1998;160:3627–3630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]